Abstract

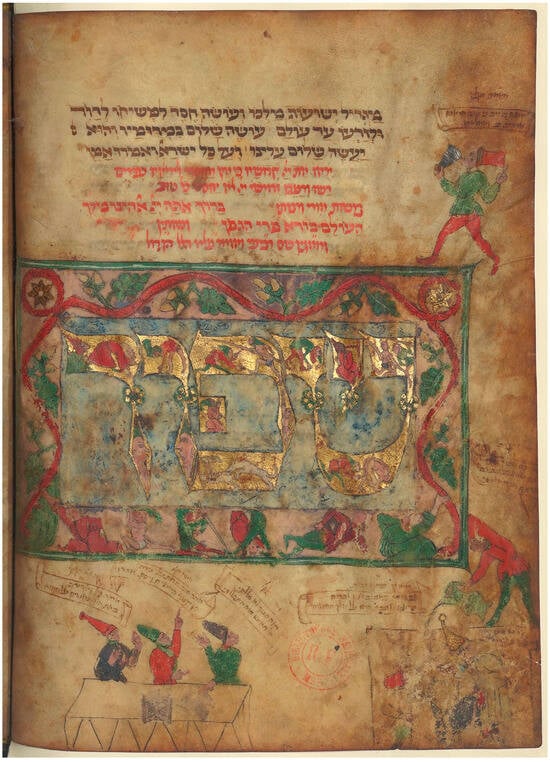

This essay explores a remarkable manuscript, the so-called Hileq and Bileq Haggadah (Paris, BnF Ms. Hébreu 1333), illuminated in southern Germany in the fifteenth century. Our focus, in particular, is on the image that accompanies the Shefokh ḥamatkha prayer, an invocation of God’s vengeance upon nonbelievers. Here, we posit the role of the Shefokh ḥamatkha folio within the context of the Hileq and Bileq Haggadah, suggesting that its prominent position and extravagant visual program involve the reader–viewer in a performative scenario that inflects the meaning of the other images in the book as well as the enactment of the Seder ritual itself. The messianic import of the folio is underscored by its enactive language, both visual and oral, and predicated on the emotional communities that coalesced around the Passover ritual in the later Middle Ages.

1. Introduction

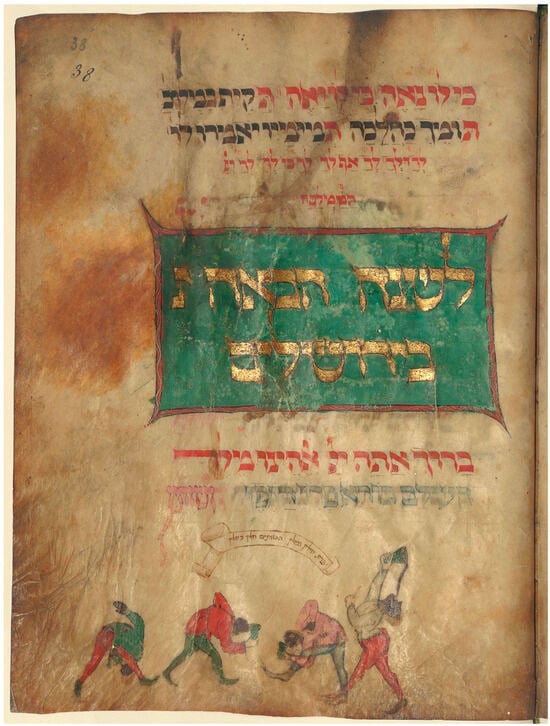

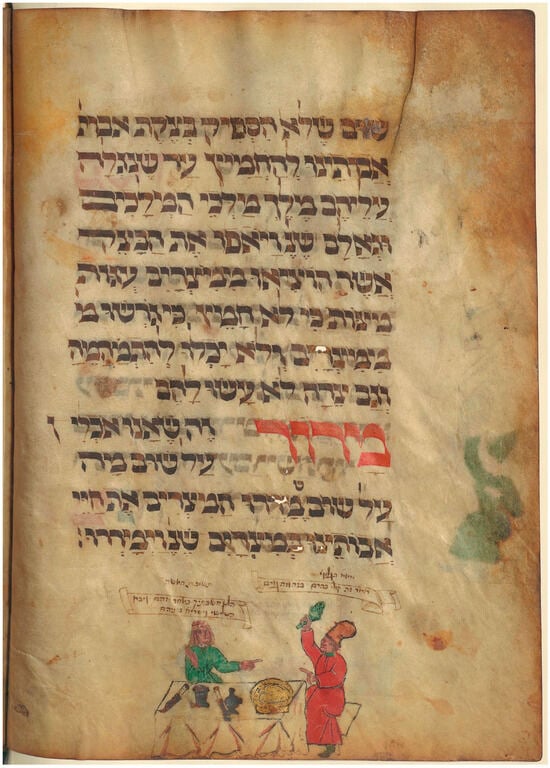

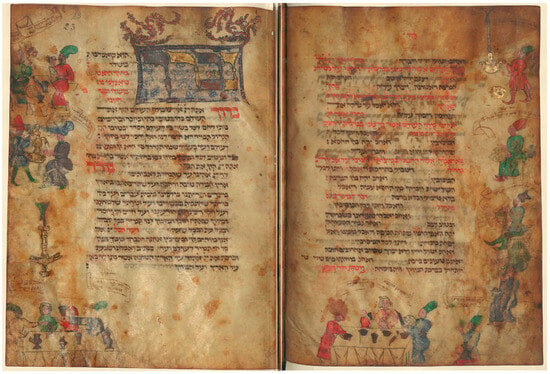

The Hileq and Bileq Haggadah (Paris, BnF Ms. Hébreu 1333), illuminated in southern Germany sometime in the fifteenth century, is known to specialists primarily for two images: one of the eponymous Hileq and Bileq, a pair of drinking acrobats tumbling across the manuscript’s last page (Figure 1), and another of a husband and wife arguing over the maror and naming each other as the cause of the herb’s bitterness (Figure 2).1 Both images are accompanied by humorous captions, attributed to the artist and scribe Abraham ben R. Moses Landau, who identifies himself in the colophon and describes himself as someone “who wrote the poems in humble words, half asleep.” But the most striking image in the manuscript, by far the most detailed, complicated, and dramatic—clearly emphasized by the artist above all other images—is the one that accompanies the powerful and beseeching Shefokh ḥamatkha prayer, an invocation of God’s vengeance upon nonbelievers (Figure 3). In this essay, we explore the role of the Shefokh ḥamatkha folio within the context of the manuscript, suggesting that its prominent position and extravagant visual program involve the reader–viewer in a performative scenario that inflects the meaning of the other images in the book as well as the enactment of the Seder ritual itself.

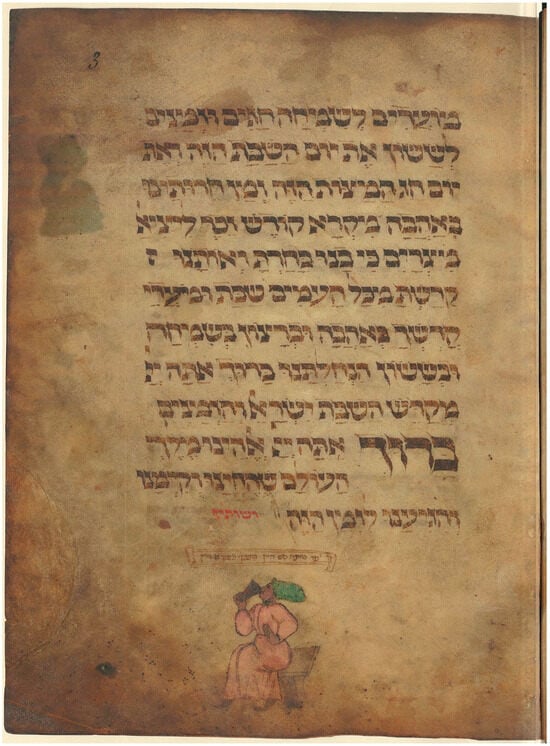

Figure 1.

Hileq and Bileq, a pair of drinking acrobats, Hileq and Bileq Haggadah; artist and scribe Abraham ben R. Moses Landau, 15th c., Franconia, 235 × 174 mm. Paris, BnF, Ms. Hébreu 1333, fol. 38r.

Figure 2.

Husband and wife arguing over the maror and naming each other as the cause of the herb’s bitterness, Hileq and Bileq Haggadah; artist and scribe Abraham ben R. Moses Landau, 15th c., Franconia, 235 × 174 mm. Paris, BnF, Ms. Hébreu 1333, fol. 19v.

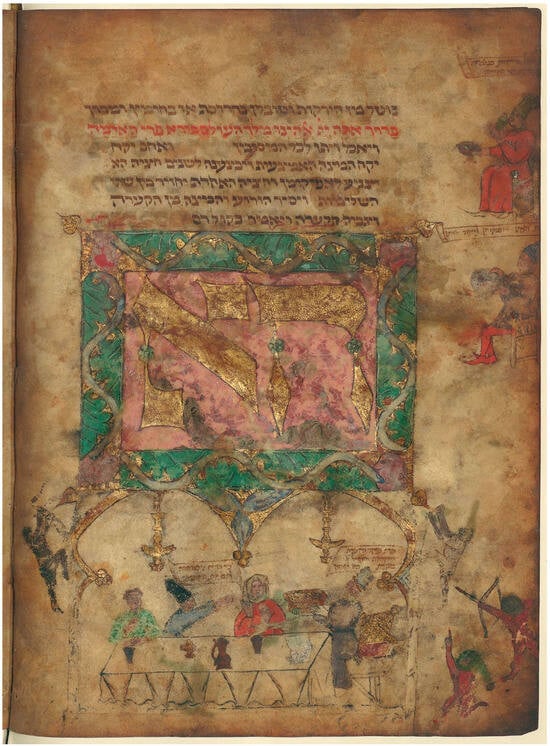

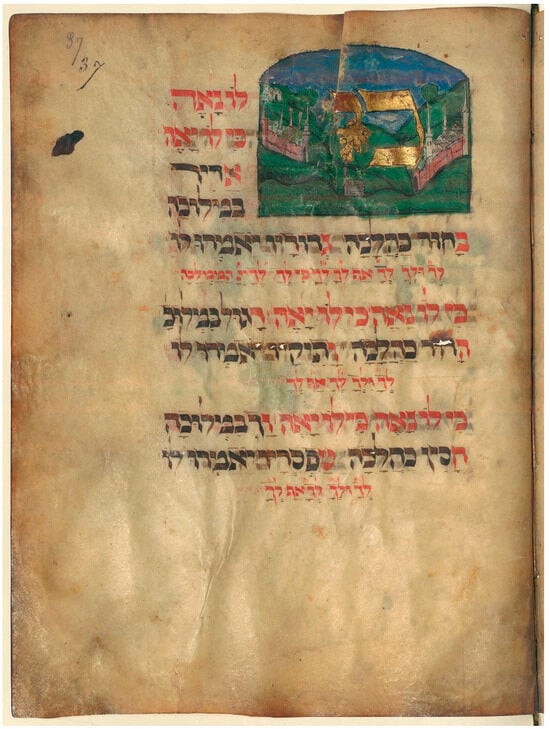

Figure 3.

Shefokh ḥamatkha prayer, an invocation of God’s vengeance upon nonbelievers, Hileq and Bileq Haggadah; artist and scribe Abraham ben R. Moses Landau, 15th c., Franconia, 235 × 174 mm. Paris, BnF, Ms. Hébreu 1333, fol. 24v.

The Seder is a ceremonial feast at the start of Passover, the holiday that lasts eight days outside Israel and celebrates freedom from Egyptian bondage. The ritual itself springs from the biblical commandment to Jacob, found in the book of Exodus (13:8), to “tell your child on that day” that “it is because of what the Lord did for me when I came out of Egypt.” This telling is codified in the haggadah (plural haggadot), the book that includes the basic moments of the narrative as it is found in Exodus, accompanied by blessings, prayers, songs, and commentaries. The etymology of the word “haggadah”, in fact, is rooted in the Hebrew verb “l’hagid,” to narrate or to expound. One of the most frequently illustrated Hebrew books in the Middle Ages, a haggadah, central to the Seder, is meant as a starting point for an extended conversation about slavery and freedom: it provides a script, yes, but allows for, and, indeed, encourages, digressions and additions.

The “Pour out your wrath” prayer was one such addition, a relative latecomer to the ritual. The prayer’s earliest appearance occurs in the Mahzor Vitry, extant now in at least eleven manuscripts.2 Regularly included in medieval haggadot from roughly the eleventh or early twelfth century onwards, it became particularly popular in Europe at the time of continuous anti-Jewish persecutions.3 The prayer forms part of the after-dinner segment of the Passover service, the Hallel portion, and is recited after the fourth cup of wine has been poured (Tabory 2008, pp. 101, 110).4 Shefokh ḥamatkha precedes the Hallel song proper, constituted by the Psalms of praise, and forms a fitting contrast to it. Making use of several biblical passages drawn from Jeremiah, Psalms, and Lamentations, it reads, in its entirety, as follows:

Pour out Your wrath [or fury or rage] upon the nations that do not know You, / and upon the kingdoms that do not invoke [or have not called] Your name, / for they have devoured Jacob and desolated his home. / Pour out [Your wrath] upon them; may Your blazing anger overtake them. / Oh, pursue them in wrath and destroy them from under the heavens of the Lord.5

Its temporal place within the home liturgy of the Seder is significant; as Lawrence Rosenwald has underscored, the text, recited at a liminal moment in the service, is itself liminal—“a curse both controlled and uncontrolled” (Rosenwald 2020, p. 55).6 The prayer comes at a performative, theatrical moment of the service: although the haggadah’s text does not dictate this action, it seems to have been commonplace for the front door of the house to be opened before the Shefokh ḥamatkha was said and closed after it was completed. The act was meant to welcome passersby to join in the celebration. At the same time, it functioned as a quasi-public dissent against gentile oppressors, who could ostensibly hear—but likely not understand—the invocations being said against them. Finally, the gesture forged a connection between the Seder and eschatological events: one day, it would greet the prophet Elijah, the harbinger of the Messiah himself.7

This connection is underscored in the Hileq and Bileq manuscript, where the messianic undertones are couched in enactive language, both visual and oral: a ramping up of the Shefokh ḥamatkha prayer that itself constitutes a highly charged performative act, predicated on the emotional communities that coalesced around the Passover ritual. Described by Barbara Rosenwein as “groups in which people adhere to the same norms of emotional expression and value—or devalue—the same or related emotions,” these communities provide a particularly useful framework for the study of the Hileq and Bileq image (Rosenwein 2006, p. 2) (see also Rosenwein 2002, 2010, 2016). Dynamic and ever-changing, emotional communities overlap with social communities at the same time that they are framed by systems of feeling (familial, religious, occupational) as well as different expectations and norms that may alter a person’s emotional expressions (Rosenwein 2010, p. 11).8 These communities are anchored by familiar, secure spaces—a home or a synagogue—the loci that help to articulate shared rituals, and where the consumption of the customary ceremonial foods and beverages carries the emotional valence of belonging.9 The Passover Seder exemplifies the kind of ritualistic space that requires a specific emotional performance; the haggadah images, then, might be seen as reliable sites of performative communities, a notion that has not been explored by scholars who have contented with the origins, functions, and visual programs of the Shefokh ḥamatkha (see, e.g., Buda 2012a; Epstein 2001; Gutmann 1974; Gutmann 1967–1968; Landsberger 1948; Shacham-Rosby 2016; Shalev-Eyni 2018).

2. Contextualizing the Shefokh Ḥamatkha

Images accompanying Shefokh ḥamatkha are common in medieval Ashkenazic haggadot. At times, they are strictly confined to word panels and marginal images, as in the Ashkenazi Haggadah (BL Ms. Add. 14762, fol. 31r), attributed to Joel ben Simeon (active late 1440s-ca. 1490) (Figure 4).10 Images in these word panels often evoke rather than directly refer to the Seder. In the Ashkenazi Haggadah, for instance, the panel for the prayer itself, awash in lush vegetal imagery, encloses the word שְׁפֹוךְ, or “pour out,” painted in a rich blue color and inhabited by small figurative images picked out in white. To the left of the panel, a man emerges from a sprouting cornucopia. He holds aloft and contemplates an oversized gilded cup, a reference both to the fourth wine cup drunk at the Seder and to the illuminated word itself.

Figure 4.

Shefokh ḥamatkha, Ashkenazi Haggadah; scribe Meir Jaffe; artist Joel ben Simeon, ca. 1460, Southern Germany, Ulm?, 375 mm × 275 mm. London, BL, Ms. Add. 14762, fol. 31.

In other instances, the entirety of the page provides the visual framework for the prayer, frequently stressing its messianic import. For example, the First New York Haggadah (New York, Jewish Theological Seminary, Ms. 4481, fol. 14v), roughly contemporaneous to the Hileq and Bileq manuscript, augments a decorated word panel with an image in the bas-de-page.11 Here, the Hebrew letters, which are formed by the portions of bare parchment, feature ornamental designs in a light wash of brown ink against a red grid pattern (Figure 5). At the bottom of the folio, a now barely visible scene takes place. Depicted in the darkened doorway of his home, a Seder participant greets a man seated upon an ass and blowing a shofar, or a ram’s horn. This figure suggests both the prophet Elijah, heralding the coming of the Messiah (drawn from Malachi 3:23: “Behold, I will send you Elijah the prophet before the coming of the great and terrible day of the Lord”), and the Messiah himself, set to appear riding on a donkey (Zechariah 9:9). The label beside Elijah (“משיח” or Mashiah) confirms this reading. The caption above the figure in the doorway’s head is a combination of Yiddish and Hebrew: “the youngling [or young man] opens the door” (ינגלין פתח הדלת).

Figure 5.

Shefokh ḥamatkha prayer, First New York Haggadah; artist and scribe Joel ben Simeon, 1445, Germany, 34 cm × 25.5 cm. New York, Jewish Theological Seminary, Ms. 4481, fol. 14v. Courtesy of the Jewish Theological Seminary.

Eschatological language is similarly on full display in the Hileq and Bileq Shefokh ḥamatkha folio, where the elaborate word panel, which takes up nearly half of the page, is accompanied by two vignettes at the bottom. On the right, one can just make out the badly damaged framed scene: a man in an elaborate headdress, a donkey, and another man before them. Atop the frame—a picture within a picture—stands yet another man pouring out a jug of liquid. A marred speech scroll above him references the prayer: “When reciting ‘Shefokh’ with me […] I heard from your mouth […] and I filled my cup.”12 Another banderole above the left corner of the scene helps explicate the damaged image: “Says he who opens the door: ‘How far do you carry the joke? You nearly poured water on the king Messiah.’”

To the left, another better-preserved scene features three men sitting at a table and gesturing upward, to the word panel. Speech scrolls accompany them as well. The man on the right says, “I had not thought to see thy face. I prayed for this man.” His neighbor replies, “Quickly turn the door on its hinges, lest the Messiah be angered and turn back.” The man on the left concurs: “I will see and turn aside, the coming of the king Messiah on his donkey.” But within the word panel itself, the pious sentiment of this dialogue is swept aside by the riot of wild imagery: a leafy oak vine whose curving contour pales in comparison with the contortions of performers who twist themselves within and without the golden letters. An acrobat bends down to lick the genitals of his naked companion at the bottom of the letter shin; a hound attacks a stag within the letter fei; two faces crowd into stems of the letters vav and kaph, their mouths wide open as if in silent screams. On top of the panel, stepping backward into the right margin, a man throws back his head to drink from a silver cup and says, “I will drink my wine, because it looks nice. I will open my mouth wide, and I will fill it.”

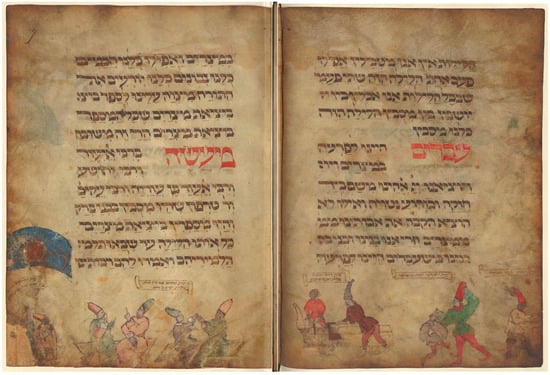

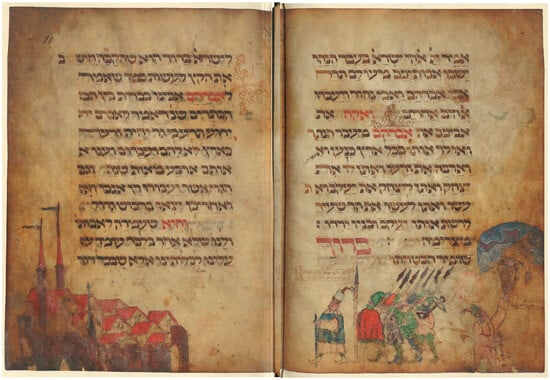

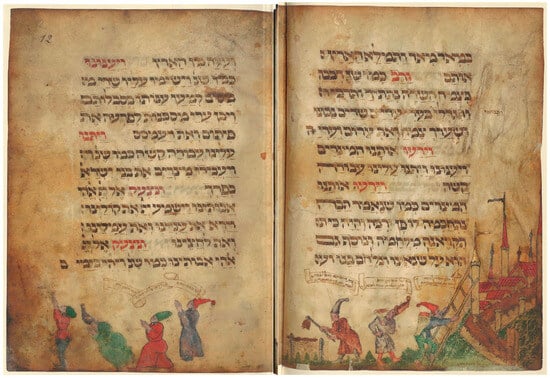

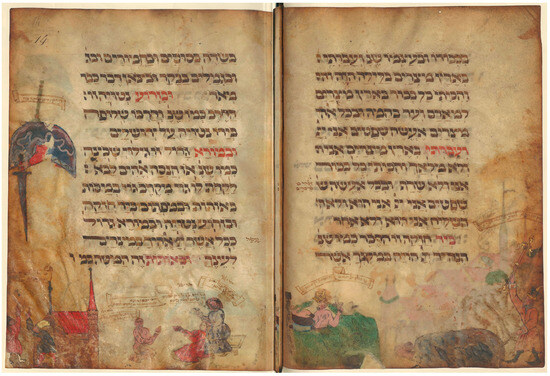

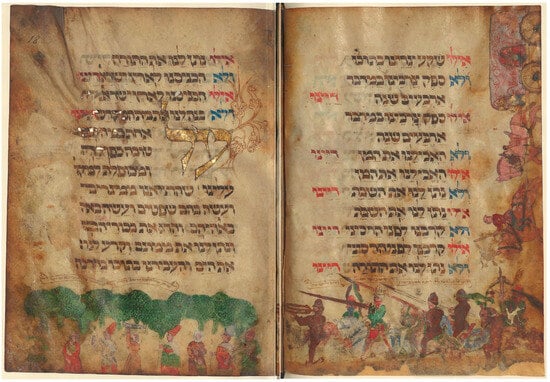

The page, explosively bright and compositionally crowded, comes as something of a crescendo in the manuscript filled with dynamic and expressive figures—ornately dressed and sporting elaborate headdresses—who veritably leap from page to page, climbing its margins, pointing their long digits at one another and at the text, and providing a running, and rhyming, commentary on it.13 Many of them, it soon becomes clear—like the figures who raise the matzah and maror, or who gather at the Seder table, or who busy themselves with pouring countless cups of wine—are clearly meant to serve as surrogates of the Passover ritual enacted in the spaces where the haggadah was being read. Throughout, captions and speech scrolls guide the beholder’s attention and comment on the narration. The book begins in the immediate present of the readers–viewers with the relatively sedate first folios, which figure pious Jews searching for leaven, raising cups of wine, and reciting prayers. But, soon, the readers come to folio 5v, where the action picks up with the animated conversation at the Seder table, a reference to “let all who are hungry come and eat” (Figure 6 and Figure 7). The frame of the word panel shelters the celebrants from invading figures in the margins that include simian creatures pursued by archers. We are then thrown deep into the past: on folio 6v, animated figures demonstrate the fate of the Jews as slaves in Egypt. The facing page, in turn, yanks us forward in time, to the times of Roman oppression, with the five rabbis of B’nei Brak—Eliezer, Joshua, Tarfon, Eleazar ben Azariah, and Akiba—gathering to narrate the Exodus story with the help of dramatic gestures (Figure 8). Several folios later, plunged once again into a truly ancient past, we see a fancifully dressed Jacob marching a group of equally dapper men out of Canaan and into Egypt, here fashioned as a cozy medieval city across the book’s gutter (Figure 9). At this juncture, the story becomes linear. On 11v, the hard-working Israelites labor for the sake of that very same city, hewing stones and climbing ladders, while facing them is another group of the selfsame Israelites—standing, kneeling, running—who cry out “to God of our fathers” (Figure 10). Another page-spread draws from midrashic sources and their medieval commentaries: on folio 12v, Pharaoh attempts to cure himself from leprosy by bathing in the blood of Israelite children, while, across the gutter, Egyptians, standing on the walls of the city, are throwing Jewish infant boys into the river below, the fish ready to devour them (Figure 11).14

Figure 6.

Raising the first Seder cup, Hileq and Bileq Haggadah; artist and scribe Abraham ben R. Moses Landau, 15th c., Franconia, 235 × 174 mm. Paris, BnF, Ms. Hébreu 1333, fol. 3r.

Figure 7.

Seder Table, Hileq and Bileq Haggadah; artist and scribe Abraham ben R. Moses Landau, 15th c., Franconia, 235 × 174 mm. Paris, BnF, Ms. Hébreu 1333, fol. 5v.

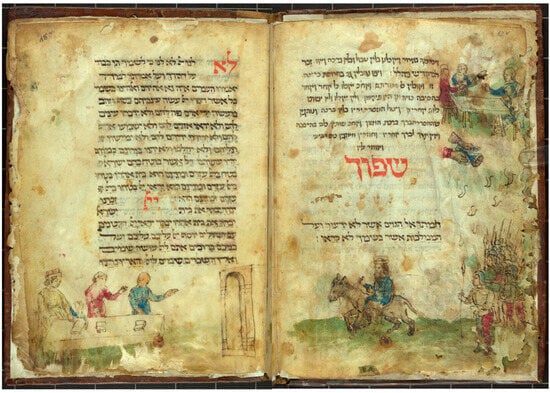

Figure 8.

Jews in Egypt; the Five Rabbis, Hileq and Bileq Haggadah; artist and scribe Abraham ben R. Moses Landau, 15th c., Franconia, 235 × 174 mm. Paris, BnF, Ms. Hébreu 1333, fols. 6v and 7r.

Figure 9.

Jacob leads men into Egypt, Hileq and Bileq Haggadah; artist and scribe Abraham ben R. Moses Landau, 15th c., Franconia, 235 × 174 mm. Paris, BnF, Ms. Hébreu 1333, fols. 9v and 10r.

Figure 10.

Israelites in Egypt, Hileq and Bileq Haggadah; artist and scribe Abraham ben R. Moses Landau, 15th c., Franconia, 235 × 174 mm. Paris, BnF, Ms. Hébreu 1333, fols. 11v and 12r.

Figure 11.

Pharaoh Bathes in Blood; Jewish Children Drowned, Hileq and Bileq Haggadah; artist and scribe Abraham ben R. Moses Landau, 15th c., Franconia, 235 × 174 mm. Paris, BnF, Ms. Hébreu 1333, fols. 12v and 13r.

The sequence of plagues begins on folio 13v, where, at the right of the page, Aaron strikes the waters to turn them into blood, while, on the left, the Pharaoh, nude but for the crown, is beset by frogs in his own bed. Across the gutter, mouse-sized lice crawl over the Egyptians (Figure 12). In rapid succession, plagues follow: wild animals attacking children and adults alike (14v), murrain (15r), and boils that occasion another chance to show nearly-nude Egyptians (15v). On the subsequent page, hail beats down contorted figures, and one unlucky man appears to be under attack by a swarm of small dragons—what passed for locusts in the artist’s imagination. On 16v, the “It would have sufficed” (Dayenu, דינו) sequence begins, the images too abraded on the right to be fully comprehensible save for the exchange between Pharaoh and Moses. The baking of the matzah is also in full swing. On 17v-18r, Pharaoh’s army, descending the right margin and landing at the bottom, pursues the fleeing Jews (Figure 13). On 18v, frenetic action slows down and we are brought to the first century BCE, with Rabban Gamliel shown expounding on the three obligatory Passover things. These things are pictured on two subsequent folios: the lamb (or pesach) roasted on a spit, the round matzah raised in a man’s hand, and the bitter herb that, as we have seen, occasions a droll exchange between the husband and wife who accuse each other of true bitterness (see Figure 2). The majority of images that follow focus on the Seder table: a family gathered together to fulfill their duty to “praise, extol, glorify, exalt, magnify, bless, celebrate, and acclaim” God (fol. 20v); a pictorial guide to the many blessings said at that table (22v); and the breaking of the bread, the washing of the hands, the raising of the cups (23r) (Figure 14).

Figure 12.

Plagues: Blood, Frogs and Lice, Hileq and Bileq Haggadah; artist and scribe Abraham ben R. Moses Landau, 15th c., Franconia, 235 × 174 mm. Paris, BnF, Ms. Hébreu 1333, fols. 13v and 14r.

Figure 13.

The Exodus from Egypt, Hileq and Bileq Haggadah; artist and scribe Abraham ben R. Moses Landau, 15th c., Franconia, 235 × 174 mm. Paris, BnF, Ms. Hébreu 1333, fols. 17v and 18r.

Figure 14.

Seder Rituals, Hileq and Bileq Haggadah; artist and scribe Abraham ben R. Moses Landau, 15th c., Franconia, 235 × 174 mm. Paris, BnF, Ms. Hébreu 1333, fols. 22v and 23r.

These images build to the visual explosion of color and form on the Shefokh page, clearly conceived as the most visually striking one in the entire manuscript (see Figure 3). The letters in the word panel gleam with gold; the blue pigment against which they were painted has all but disappeared, its traces suggesting just how vibrant it must have been in the fifteenth century. Significantly, this page boasts the only inhabited word panel in the entire manuscript. Every available space within the letters is given to small creatures that climb, fight, point, run, and twist in a dizzying way. Some may carry a tenuous connection to the prayer itself: a kneeling man within the fei might be beseeching God to unleash his wrath; the sword-, club-, and stick-bearing figures provide appropriately bellicose allusions; the hound pouncing on the stag is a well-known metaphor for anti-Jewish persecution (see, e.g., Epstein 1997, esp. ch. 2, pp. 16–38; Offenberg 2020; Amirov 2018, esp. pp. 115–32). Others may gesture to the larger context of the Passover: the man reclining at the bottom of the word panel is leaning on his left side, as per explicit haggadah instructions; the oak that frames the panel recalls Isaiah 61:3, אֵילֵי הַצֶּדֶק, translated variously as terebinths or oaks of righteousness.15 Others, however—disorderly, anarchic, or downright obscene—may gesture at the behavior of “the nations” on which the wrath is meant to be unleashed, thus providing an arresting contrast to the immediacy of the unframed scenes that unfold below, which embody the most fervent hopes of medieval Jewry, gripped by decades of persecutions and murder: the advent of the Messiah.16

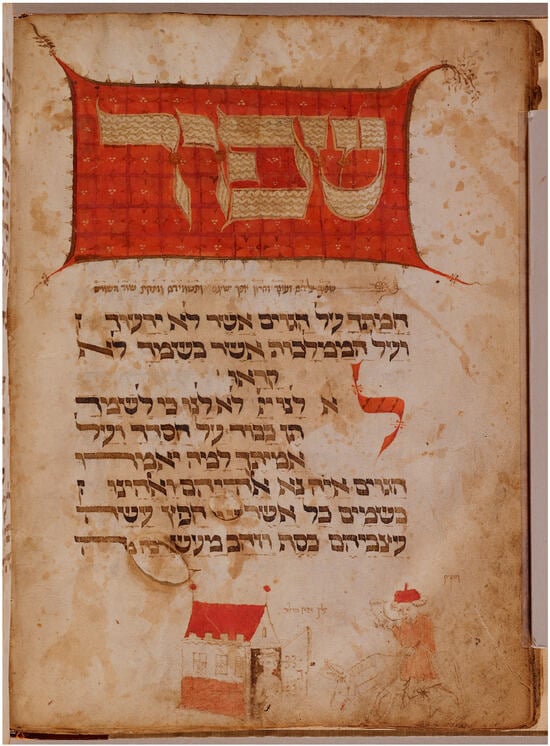

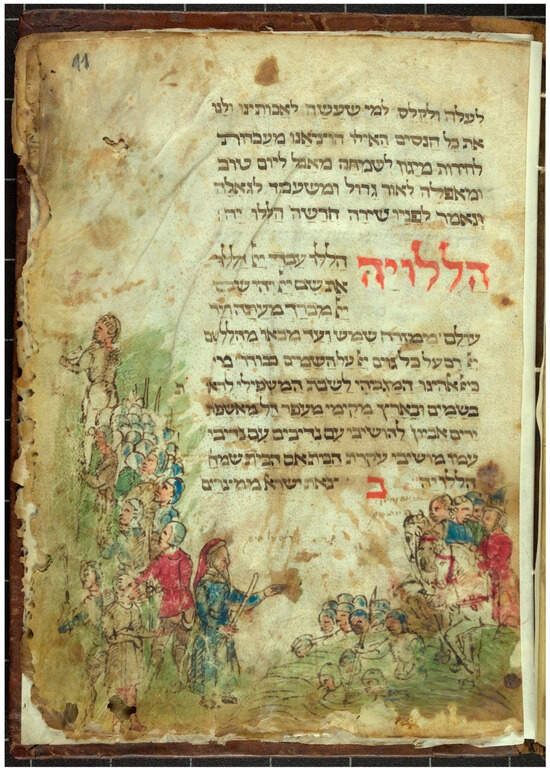

As if spent by the sheer force of the wrath, no images appear for many folios after the Shefokh page, with just a few uninhabited word panels breaking up the text.17 Finally, on folio 37r, the reader encounters the word panel “For [him it is fitting]”, a piyyut in praise of divine kingship (Figure 15). It features a peaceful landscape with a medieval town on its hills: clearly Jerusalem since, on 38r, the same verdant green spreads behind the phrase “Next Year in Jerusalem.” Underneath, the acrobats reprise their boozy performance, the caption helpfully explaining that this is “the image of Hileq and Bileq each drinking his share” (see Figure 1).18 Clutching their cups, three of the four acrobats bend at the waist, seemingly taking a bow. Therein, the visual program of the manuscript comes to an end.

Figure 15.

Jerusalem, Hileq and Bileq Haggadah; artist and scribe Abraham ben R. Moses Landau, 15th c., Franconia, 235 × 174 mm. Paris, BnF, Ms. Hébreu 1333, fol. 37r.

3. Performance/Performativity

The dramatic bow of the acrobats provides a fitting conclusion for the manuscript that structures itself as a theatrical space of sorts, particularly apt for the liturgical ritual structured explicitly as a performance, wherein present-day participants enact past events. In that sense, every haggadah serves as a material prop for the enactment of the Seder—with wine and food stains often bearing eloquent witness to such use—and every haggadah constitutes a performative space, its narrative guided by the Mishnaic directive to fashion oneself in the likeness of the freed slave (Pesaḥim 10:5): “In each and every generation a person must view himself as though he personally left Egypt, as it is stated: ‘And you shall tell your son on that day, saying: It is because of this which the Lord did for me when I came forth out of Egypt’”19. The quote from Exodus 13:8 unambiguously encourages what scholars have called “engaged memory”; it inserts the Seder participants into the historical enactment of the past, while also gesturing to future generations’ continual reperformances of the same.20

As a rule, images in medieval haggadot encouraged a series of multisensory experiences explicitly formulated to adhere to this directive to conflate the past, the present, and the future (Epstein 2011, esp. the introduction; Cohen 2016). Medieval Shefokh folios seem tailor-made to encourage this conflation, inasmuch as they frequently bring together images of the Exodus infused into images of the present-day Seder and the future appearance of the Messiah. One striking late fourteenth-century haggadah, now in Darmstadt (Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek, Cod. Or. 28), explicitly and implicitly fuses temporalities (Figure 16).21 On folio 12v, which features the word Shefokh in red, the Messiah rides his donkey towards the archway painted just across the gutter, on folio 13r. Behind him, an army follows, and, above this army, two disembodied hands are emptying a blue chalice. Small flame-like images escaping from this chalice leave little doubt that what we see is a visualization of divine wrath raining down upon the army. Above, Seder participants gather around a table set with several cups of wine, breaking the afikomen, the part of the matzah to be hidden, found, and then eaten as the last segment of the meal. On the facing page, the Seder table reappears to the left of the arch; those seated at the table point either towards their books or towards an open archway towards which the Messiah, followed by an army, rides.22 His enemies, an army of Christian knights, plainly evoke Pharaoh’s army painted on the previous page, on folio 11r, where in pursuit of the Israelites they are drowned in the Sea of Reeds (Figure 17). In this way, the Egyptian enemies of the past are reified as the enemies of the present upon whom God is asked to pour out his wrath and conflated with the enemies of the future who pursue the Messiah.23 The re-performance of these commingled identities is enacted through the bodies of the once and future Passover participants—both those pictured on the pages of the haggadah and those gathered around the actual Seder tables—who simultaneously re-tell the events of the Exodus “as though [they] personally left Egypt,” beseech God to visit his blazing anger “upon the nations that do not know” him, and greet the herald of the world to come. The visually directed reading of these images—beginning in the rightmost margin, moving down and along the bas-de-page across the manuscript’s gutter and through the image of an archway—serves to dramatically separate and unite different temporalities. This arrangement pulls the reader’s gaze toward the doorway, transforming it into the nexus between past, present, and future events. The experience of the current Seder is ultimately combined with the Seder that is longed for––the one that will bring forth the Messianic era. The past and future redemptions are brought together in a powerful performance.

Figure 16.

The Messiah Rides a Donkey towards Seder Participants, Haggadah, late 14th c., Germany. Darmstadt, Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek, Cod. Or. 28, fols. 12v and 13r.

Figure 17.

Pharaoh’s Army Pursues the Israelites, Haggadah, late 14th c., Germany. Darmstadt, Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek, Cod. Or. 28, fol. 11r.

The notion of performance—in its very medieval sense—comes to the fore in the Hileq and Bileq manuscript, structured with cues for dramatic enactment, anchored within specific temporal and spatial limits (here, the celebrants’ home on the eve of the fifteenth day of Nisan), and predicated on annual repetition and reiteration as a stimulus for activating memory and affective response.24 Marginal scenes conceived as vignettes are accompanied by a lively dialogue, inscribed on speech scrolls, which employs every rhetorical trick in the book to make it memorable: the lines rhyme; participants joke, mock each other, trade insults; an implied narrator addresses the viewer; and at times the characters themselves seem to speak to us, the audience. On folio 2r, for instance, a man lifts his cup and—in absence of the pictured audience—engages the readers–viewers: “with your permissions, my teachers and gentlemen, I will bless at my sabbath eves.” Characters insistently narrate their own actions, providing a running commentary-cum-stage-directions, focused mainly on drinking. On folio 2v, the pictured celebrant declares, “I will draw my wine, which looks so fine, I will open my mouth wide and I will fill it” (a reference to Psalm 81:11); on folio 5r, another says, “I will swallow and lack nothing of the full cup (of happiness)”; on folio 6r, yet another promises to “pour my cup and fill it when I reach m[ah nishtanah].” That the reader–viewer embodied the actions of these characters is unquestionable: the manuscript, veritably awash in representations of potables, is itself generously splattered with wine. But the insistent use of “I” and “me” throughout the manuscript is especially striking: on folio 22v, a man holding a matzah is explicitly characterized as an “image of me blessing energetically the blessing of ‘who brings forth bread from the earth’,” while a man lifting maror announces to the audience: “I will raise my voice and bless the eating of bitter herbs” (see Figure 14).

And yet, the speaker leaves no doubt that the ritual is communal. On that same folio, a man who lifts both the matzah and the maror looks at another man pictured on the page to draw the reader–viewer’s attention to his presence: “he [and] also I will prepare the korekh, as it should be done.” And on 23r, this communal aspect is confirmed by the explanatory caption above the image of a Seder table: “Image of [the man] eating the afikomen after his meal. All the congregation of Israel will do the same.” Here, it is not the protagonist of the image who speaks but the implied narrator, or what in late medieval plays would be call an “expositor”.

The presence of the expositor—a figure who remained on stage throughout the play, guiding and commenting on the action and thus serving as a mediator between the performance and the audience—is here denoted rather than directly visualized.25 On folio 3r, this implied narrator invites the reader–viewer to ponder a man “who drinks the cup of wine. Glance at it and it has gone” (see Figure 6). On folio 4r, another man throws his head back to drink, and the expositor announces, as if from the wings, “he who drinks his cup all at once is called tippler, but what is in it, we were not told.” The presence of this intermediary character is felt particularly strongly because some captions are accompanied by the explanatory “says the picture” or “image of”—an anxious scribal tic that seeks to clarify the meaning of vignettes, sometimes staging the direct speech inscribed on scrolls as a surrogate for the authorial voice.26

Performative imperative is also inscribed in the dialogues, sometimes antagonistic, sometimes humorous, sometimes both. On folio 14r, Egyptians suffering from the third plague argue about whose lice are bigger (see Figure 12). A naked man points to the enormous parasites and petulantly declares, “See, mine are twice as large, each one is as two [of yours].” His interlocutors, two dressed women, feel up to participating in this contest. One, seemingly reveling in her misfortune, says, “See, my share of the lice has increased, [they are] very soft and fat. They were changed to various colors: red, black, green, and white.” The woman on the right querulously says, “I found one that is bigger than that”—and then, hilariously, quotes the Song of Songs 3:4: “I hold it and will not let it go.” On folio 19v, the famous exchange between a husband and a wife over the maror takes the joke seen in other medieval haggadot and extends it. At the table, a man and a woman point at each other, while the expositor provides a running commentary: “Says the picture: [when saying] ‘this bitter herb’ let me raise my voice. [Indeed], both this [lettuce] and this [my wife] are the cause [of this bitterness]’.” The wife rebuts him: “I thought you were one of these [causes of bitterness].” Then, the narrator intervenes once again: “Then a third [man] comes and makes a stench between them.” This is a riff on a Tannaitic work, r. Ishmael’s set of thirteen hermeneutic principles for elucidating laws drawn from the Torah, and specifically the last principle: “two verses that contradict each other are solved when a third verse comes and resolves the contradiction.”27 Here, the argument is resolved by, literally, a stench, while the Torah verse is replaced by a man, who is not, however, pictured: the rest of this farce, it would seem, has to be imagined. The use of a Tannaitic rhetorical form to create a humorous quip immediately connects the manuscript and its author to the parodic literature of the time, which frequently used recognizable rhetorical forms from the Torah and rabbinic literature to develop what Roni Cohen has described as “an intentionally distorted version” of an original passage (Cohen 2021c, p. 476). Here, the humor works on two levels: a nod to rabbinic literature appreciated by some overlays a crude scatological joke accessible to all.

All of these performative elements—jests, conversations, narrative expositions—are present in the Shefokh ḥamatkha folio. We are privy to a lively, slightly quarrelsome dialogue among the participants of the Seder sitting at the table with their books and other protagonists of this marginal scene. One of the men, we recall, narrates his own actions: “I will see and turn aside the coming of the king Messiah on his donkey.” The one who opens the door for the Messiah makes a joke about a joke, directly addressing the figure who pours out a stream of liquid from his jug—an obvious play on “pour out your wrath”—and so blurring the pictorial universe of the page with his own lived reality. His comment on the water that nearly dowsed the king Messiah seemingly references the actual action rather than an image of the action. The authorial voice, too, is present both in multiple instances of “says the picture” and also “says the one who opens the door.” Finally, the appearance of several acrobatic figures suggests a spectacle of sorts, and this sense of movement and exaggerated gestures—evident throughout the manuscript and culminating in the contortions of Hileq, Bileq, and their brethren—undergirds the performativity of the manuscript (see Enders 2001, p. 3.).

Hyperbolic, emphatic body language of the haggadah protagonists not only figures the narrative as a spectacle but also offers cues for enactive reading. Comic theater gained popularity in the fifteenth century, and, although, at least formally, rabbinic tradition shunned theater (see Avodah Zarah 18b and Shabat 150a on “the theater and circuses of idolatry”), biblical texts are awash in costuming and cross-dressing (Genesis 27, Samuel 2:14), as well as musical performances and dances (Exodus 15 for Miriam’s dance, Samuel 2:6 for David’s) (Levy 1999).28 Before the destruction of the Temple, Simhat Beit Hasho’eva (the Water Drawing Festival), held during the festival of Sukkot, invited not only dancing and music-making but also acrobatics and juggling with torches, knives, full wine glasses, and eggs wrought by the rabbis themselves (Sukkah 53a).29 There is a mention of jesters (badhanim) performing at weddings, both in ancient and medieval Jewish literature, and, as early as the twelfth century, a folk performance of Purimspiel took root.

Purim—which, like Passover, focused on themes of wrath, retaliation, and redemption—celebrates the triumph of the Jewish inhabitants of the Ahasuerus Persian kingdom, and particularly that of Queen Esther and her cousin Mordecai, over the wicked Amalekite Haman, the quintessential nemesis of the Jews who plotted their extermination. As Jeffrey Rubenstein and others have noted, pageants, masks and costumes, noisemaking, effigy burning, and other forms of revelry have been integral to Purim’s celebration for centuries (see Rubenstein 1992; Fisch 1994; Wechsler 1998; Segel 2007; Haas 2011). The main activity of the holiday, however, is drinking, and especially drinking to excess, to the point where one cannot not differentiate Haman from Mordecai, foe from friend.30 In fact, the tremendous emphasis on drinking in the Hileq and Bileq Haggadah suggests that Purim, which comes about a month before Passover, serves as the latter’s worthy forerunner. Little wonder that Passover and Purim—both of which reconfigured ancient enemies, be it the Pharaoh or Haman, as Christian oppressors of the present day—were explicitly linked in medieval parody literature. For instance, the twelfth-century “Hymn for the Night of Purim,” penned by one Menachem ben Aaron, satirized Meir ben Isaac’s “Hymn for the First Night of Passover,” proclaiming “This night” (a reference to the famous ma nishtana series of Passover questions, or “why is this night different from all other nights”) as “a night of drunkards” (Davidson [1906] 1966, p. 4). In a clever fourteenth-century lampoon of Talmudic writings and their medieval commentaries, Masekhet Purim (Purim Tractate), which persisted in popularity well beyond the Middle Ages, rabbinic logic is gently spoofed to dictate the proper behaviors during Purim in terms of proper behaviors during Passover: for example, instead of searching the house for leaven (and sweeping it out), as one would do to prepare for Passover, the revelers were to search for water (and, presumably, pour it out), lest they be tempted to imbibe anything other than wine during the holiday.31 And while Passover, unlike Purim, did not commonly involve mask-wearing and spectacle, there is some evidence that at least one moment of pageantry during the Seder occurred precisely during the recitation of Shefokh ḥamatkha, when the door to the street would be opened and one of the disguised Seder participants would pose as the Messiah’s harbinger, the prophet Elijah. This practice is attested to in several sixteenth-century texts, but scholars have argued that it began much earlier, perhaps at the same time as the Shefokh prayer was first inserted into medieval haggadot.32 Who, then, rides on the donkey across scores of late medieval books? Is it Elijah as the Messiah’s surrogate? Is it one of the community members, the surrogate of Elijah? Once again, temporalities clash, and liminality reigns.

4. Shefokh Ḥamatkha and Emotional Communities

The insistent use of performative devices in the Hileq and Bileq Haggadah rests on the iterative, phenomenological nature of the Seder, during which the participants’ identities are constructed, to borrow from Judith Butler, through “a series of acts which are renewed, revised, and consolidated through time” (Butler 1988, p. 523). Medieval readers–viewers were no strangers to these acts; in studying another kind of later medieval religious manuscript—Guillaume de Degulleville’s Pèlerinage de Jesucrist (Paris, Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève 1130)—Pamela Sheingorn has flagged a series of miniatures that prompt the manuscript’s users to “institute identities through the participation of their bodies in reading practices that can constitute identity as a performative accomplishment” (Sheingorn 2008, p. 60).33 Like Pèlerinage, the Hileq and Bileq Haggadah is neither a theater manuscript (prepared with a professional performance in mind) nor a play text; rather, its images cite performing bodies and encourage the re-performance by readers–viewers through a series of visual and textual cues, thereby activating specific identities of the book’s users: as religious Jews, as members of the elite class, as performers of familial roles.

It is important to note that the Hileq and Bileq Haggadah is not unique in its use of speech scrolls even though it might be the earliest; other fifteenth-century haggadot, including the Yahuda Haggadah and the Second Nuremberg Haggadah (both 1450–75) as well as the First Cincinnati Haggadah (ca. 1480–90), also make use of this performative device to some, although lesser, extent.34 Why was this use so compelling to late medieval Jewish readers–viewers? It might be because this specific form of performativity activates and helps form what Rosenwein has characterized as “emotional communities” or “groups in which people adhere to the same norms of emotional expression and value—or devalue—the same or related emotions” (Rosenwein 2006, p. 2). These dynamic and ever-changing communities are framed by “systems of feeling” (familial, religious, occupational) as well as different expectations and norms that are, per force, enactive. The Passover Seder as a ritualistic space foregrounds a specific affective performance wherein these systems—historically conditioned and constructed—underlay one’s identity within a series of social networks (Rosenwein 2010, p. 11). Emotional communities that coalesced around the Passover ritual are palpable throughout the Hileq and Bileq Haggadah and they predicate, in particular, the ramping up of the Shefokh ḥamatkha’s language, itself a highly charged performative act. Here, the reification of desire to enact the coming of the Messianic age comes to the fore, performed year after year and certainly intensified in concert with the intensification of anti-Jewish persecutions in late medieval German lands. Calculations predicting the beginning of the Messianic age proliferated within Jewish communities throughout the Middle Ages, but they reached their crescendo between the thirteenth and fifteenth centuries, when these communities—particularly those in Ashkenaz—reeled from accusations of blood libel, sorcery, host desecration, and ritual murder, which led to pogroms, murders, and expulsions.35 At this time, too, images in Hebrew books—many of which subsequently bore witness to the forced emigration of their owners—began to deal with eschatological themes more overtly.36

The Hileq and Bileq Haggadah brings such eschatological themes to the fore by building a theatrical momentum throughout its pages—here with the direct address to the viewer, there with the staging of witty dialogue—momentum that culminates in the “Pour out Your Wrath” folio with the set of enactments that involve the reader–viewer’s body directly, serving up a smorgasbord of mnemonic devices and material directives: to utter the prayer-cum-curse, to pour the fourth cup of wine, to open the door to welcome Messiah, and to stage the conversation transcribed on the speech scrolls and so performed by the Seder participants. Highly charged, the folio appears as a site for visual experimentation and fluid interpretation. Images and dialogue in banderoles operate not only as a gloss on the prayer but also as spaces for establishing networks of feelings where performative play appears crucial to the commandment to relive the Exodus narrative. Here, attendees might spy Messiah, if not in their doorway, then in their manuscript, and engage in what performance theorists term “restored behavior,” a transformative act that necessitates the presence of an audience: not just watching but also participating.37 The continual return to the haggadah and the Shefokh ḥamatkha year after year, and therefore the continued re-encountering of these images (amply evidenced by profuse wine stains), reinforces performers’ emotional communities through the ongoing reperformance and reinterpretation of the Seder and so the renewal of the hope for redemption in the world to come.

It has become commonplace to recognize the pages of medieval haggadot as a site of potent temporal collapse; to quote Marc Michael Epstein, these books stand witness to “the active linking of the present exile with both past glory and future redemption,” what he calls “the wellspring of solace” (Epstein 2011, p. 114). In other words, the role of the haggadot as “wellsprings of hope” is typical, but the mechanics of externalizing this hope are peculiar to the Hileq and Bileq codex, which operates by forming and performing emotional communities guided, to borrow from Rosenwein, by “modes of emotional expression that [people] expect, encourage, tolerate, and deplore” (Rosenwein 2002, p. 842). We know nothing about the identity of the Hileq and Bileq Haggadah’s commissioners, or the specific circumstances of its creation. What we do know is that the manuscript, and particularly its “Pour out your wrath” folio, constructs an affective space with some urgency: it is a visceral space within which the celebrants of Passover could not only inhabit the bodies of the Jews past and present but also navigate their hopes for justice in the coming Messianic era. These hopes are articulated through emotional expression undergirded by empathy—inasmuch as performance, to recall Paul Zumthor, is itself “the moment of reception” (Zumthor 1990, p. 55)—and empathy offers tools for enacting resilience, resistance, and, ultimately, subversion, allowing reader–viewers to forge, solidify, and celebrate their identities, unfractured by the diaspora.38 In the Hileq and Bileq Haggadah, performance integrates the text, the images, and the actions taking place during the Seder in real time by suspending reality and allowing the reader–viewers to continually access, actualize, and enact a set of as if moments: as if they were recently freed from slavery, as if they were retaliating against their present place in Christendom, and as if they were welcoming the Messiah—all in a single night and across the pages of a single manuscript. This ritual journey comes to a dramatic close with a flourish—with the bowing acrobats who, like the beholders, have finally concluded their performance, and who, like the beholders, have certainly drunk their share.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, writing—original draft preparation; writing—review and editing, E.G. and R.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Reed O’Mara received funding from the Case Western Reserve University’s Graduate Council of Arts and Sciences Graduate Student Scholarship and Creative Endeavors Grant in 2023 to study manuscripts at the Jewish Theological Seminary (JTS).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

Initial research for this article was made possible by the invitation extended to E.G. by the École des hautes études en sciences sociales to spend substantial time in Paris as a professeure invitée in 2022; special thanks are due to Laurent Héricher, conservator and head of the Oriental Manuscripts Division at the Bibliothèque nationale, who facilitated her access to the Hileq and Bileq Haggadah. We are grateful to Heather Galloway and Laura Rybicki for sharing their resources and expertise on silver tarnishing; to Roni Cohen for discussing Purim parodies with us; to Julie A. Harris for her insightful comments on an early draft of this paper; to Andrew Katz for arranging access to the First New York Haggadah; and, especially, to JTS Senior Conservator Akiko Yamazaki-Kleps for taking the time to examine the First New York Haggadah in the conservation lab with R.O.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Images of this manuscript were catalogued, and its inscriptions transcribed and translated, (Narkiss and Sed-Rajna 1981, nos. 57–58). Ten years later, it was included in (Garel 1991, no. 108). The Haggadah was also included in the pictorial survey compiled by Adam Cohen (Cohen 2018, no. 52), with the maror scene featured on p. 53; the same scene is discussed in (Shalev-Eyni 2018, pp. 207–34, 214–16). The manuscript is invoked in (Kogman-Appel 2011, pp. 76, 78 and 80) as the culmination of the artistic repertoire originally developed by the artist Joel ben Simeon (sometimes called Feibush), whose work featured elements traditionally found in Sephardic, Ashkenazic, and Italian haggadot. For more on the impact of Joel ben Simeon, see (Kogman-Appel 2021). The only sustained description of the Shefokh hamatkha folio, the focus of the present article, is found in (Isserles 2005–2008, pp. 150–54; see also Sed-Rajna and Fellous 1994, cat. entry 99, p. 255). |

| 2 | The earliest known surviving example is in the Jewish Theological Seminary of America in New York City (Ms. 8092) and is digitized here: https://tinyurl.com/45s9z494 (accessed 20 March 2024). This copy dates to 1204. Another example includes the British Library’s Ms. Add. 27200 and Ms. Add. 272001 (volumes one and two of a Mahzor, respectively) from ca. 1242. The British Library’s copies are also digitized but are unavailable at the time of this publication. The earliest surviving fragments of the Haggadah text itself were found in the Cairo Genizah and date to the ninth or tenth century (Stern 2011, p. 18). |

| 3 | For the legal and social status of Jews in the Middle Ages, see, e.g., (Grayzel 1989; Baron [1937] 1952–1983, esp. volumes 3–8), covering the High Middle Ages (500–1200), and volumes 9–16, covering the late Middle Ages and the era of European expansion (1200–1650). Elisheva Baumgarten has written extensively on Jewish–Christian interaction in medieval Ashkenaz; see, in particular, (Baumgarten 2016, esp. chp. 5; Baumgarten 2018). For more on the status of Jews living in medieval Europe as communicated in Christian imagery, see (Strickland 2003, esp. chp. 3; Rowe 2011; Patton 2012), esp. the introduction for wider contexts; and (Lipton 1999). For thoughts on the Jewish perspective, see, e.g., (Epstein 1997, 2011; Shalev-Eyni 2010; Offenberg 2015, 2020). |

| 4 | See also (Hammer 2011, pp. 101–13), on a brief history of Hallel and its constituent parts. In an interesting connection to the Shefokh verses’ call for the destruction of all nations, Psalm 117, which is recited during the Hallel portion, calls on all non-Israelites to praise God (see pp. 107, 111). |

| 5 | Specifically, and in order, references are to Jeremiah 10:25 (Pour out Thy wrath upon the nations that know Thee not, and upon the families that call not on Thy name; for they have devoured Jacob, yea, they have devoured him and consumed him, and have laid waste his habitation); Psalms 79:6–7 (Pour out Thy wrath upon the nations that know Thee not, and upon the kingdoms that call not upon Thy name); Psalms 69:25 (Pour out Thine indignation upon them, and let the fierceness of Thine anger overtake them); and Lamentations 3:66 (Thou wilt pursue them in anger, and destroy them from under the heavens of the Lord). Translation of the prayer is drawn from Lawrence Rosenwald and Everett Fox (Sefaria, https://tinyurl.com/ye26anm4, 26 March 2024) and Eve Feinstein (the Open Siddur Project: https://tinyurl.com/3wpauf74, accessed 26 March 2024) in dialogue with (Tabory 2008). |

| 6 | Rosenwald (2020) is also accessible at Sefaria, https://www.sefaria.org/sheets/227607?lang=bi (accessed 1 January 2023). For the birkat haMinim prayer, which similarly calls down a curse upon “others” (literally “a benediction upon heretics”), as used in Christian Europe, see (Langer 2011). |

| 7 | On the fraught role of Elijah, see (Matt 2022). |

| 8 | Rosenwein writes that emotional communities “are largely the same as social communities—families, neighborhoods, syndicates, academic institutions, monasteries, factories, platoons, princely courts. But the researcher looking at them seeks above all to uncover systems of feeling […]” (Rosenwein 2010, p. 11). |

| 9 | For more on the connection between food, the home, and memory, see (Hage 2010). |

| 10 | This haggadah also features the commentary of Eleazar of Worms. The digital facsimile is currently unavailable. For more on the biography and career of Joel ben Simeon, see (Kogman-Appel 2016; Hindman and Mintz 2020). |

| 11 | The First New York Haggadah is the earliest known haggadah to be attributed to Joel ben Simeon, whose name appears in the colophon on folio 23v. Scholarship on the manuscript is scant, and typically the manuscript is only brought up as a comparison to the Washington Haggadah (Washington, D.C., Library of Congress, Hebr. Ms. 181) or as a data point in Joel ben Simeon’s oeuvre. The digital facsimile of the JTS manuscript can be found here: https://tinyurl.com/8txuh9ah (accessed 26 March 2024). |

| 12 | Here and further inscription translations are drawn from (Narkiss and Sed-Rajna 1981). The banderole is difficult to make out; “you talked” might preface “and I filled my cup”. |

| 13 | Epstein also situates the Shefokh ḥamatkha as the climax of the Seder, arguing that Elijah’s appearance “signals the moment of the interpenetration of the miraculous into the quotidian” (Epstein 2001, p. 317). |

| 14 | On Pharaoh’s blood bath and its connections to blood therapy as well as bathhouses, see (Shoham-Steiner 2009; Buda 2012b, pp. 129–37). For the blood bath as related to accusations of blood libel, see (Malkiel 1993). The iconography appears in the Hamburg Miscellany (Hamburg, Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek, Cod. Heb. 37, fol. 27v), Second Nuremberg Haggadah (Jerusalem, Schocken Library, Ms. 24087, fol. 14r), Yahuda Haggadah (Jerusalem, Israel Museum, acc. No. B55.01.0109, fol. 13r), and Ryzhin Siddur (Jerusalem, Israel Museum, Ms. 180/53, fol. 163v), as well as in several printed haggadot, including the Prague Haggadah, dated to 1526. |

| 15 | Isserles suggests that the figures within the word gesture to the larger Christian world; she sees, for instance, an allusion to a flagellant in one of the twisting figures and cites Hosea 4:13 and David Kimchi in suggesting that the oak here stands as a symbol of idolatry (Isserles 2005–2008, p. 154). |

| 16 | On the role of unframed miniatures in “pulling the viewer into the world of the depicted figures,” see (Kogman-Appel 2020, pp. 170–71); the point is similarly developed in (Kogman-Appel 2015). |

| 17 | Those appear on folio 30v (“The Breath of Every Living Thing”) and on folio 35v (“The Strength of Your Miraculous Powers”). |

| 18 | The four figures on fol. 38v have darkened faces, possibly executed in silver leaf. Silver leaf can be found throughout the manuscript, visible especially on fols. 4r, 7r, 17r, and 23r on vessels and sleeves. Conservator Heather Galloway has posited, however, that, while areas with a visible red bole layer and crackling readily indicate the use of silver leaf, other darkened areas may be the result of a lead white pigment blackening over time. For these reasons, it is possible that there are two kinds of darkening on fol. 38v. Heather Galloway, personal email correspondence, 19 October–14 November 2023. A Hebrew manuscript with comparable images is the Bodmer Haggadah (Cologny-Genève, Fondation Martin Bodmer, Ms. 81, esp. fols. 5v and 9r). Firsthand scientific analysis of the manuscript will be required to definitively identify the sources of darkening. For more on silver’s propensity to tarnish and deteriorate when used in manuscripts, see (Araújo et al. 2018; Ricciardi and Beers 2020, p. 37; Rochmes 2022, esp. pp. 281–82; Turner 2022, esp. pp. 61–62). |

| 19 | The William Davidson digital edition of the Koren Noé Talmud and the Mishnah Pesaḥim specifically can be found in both English and Hebrew on Sefaria, https://tinyurl.com/2s4xve2c, accessed 1 March 2022. |

| 20 | For more on the haggadah and its relationship to engaged memory, see (Epstein 2011, pp. 1–3). Julie A. Harris has written extensively on Sephardic haggadot and their audiences; see, e.g., (Harris 2002, 2013, 2015). |

| 21 | This manuscript is significantly abraded, particularly around the edges of the folios. Research on Cod. Or. 28 is limited; no secondary sources are mentioned in the manuscript’s entry on the Bezalel Narkiss Index of Jewish Art (https://tinyurl.com/ybcdwcnd, accessed 20 April 2022). A digital facsimile of the manuscript can be found at http://tinyurl.com/e5fj6b6w (accessed 26 March 2024). |

| 22 | The folio has been mislabeled as 13v at the top left corner. |

| 23 | See, for example, the Birds’ Head Haggadah (Jerusalem, Israel Museum, Ms. 180/57), wherein Pharaoh’s men are rendered as Crusader knights, while the Pharaoh himself is figured as a crowned king. Similarly, in the Golden Haggadah (London, British Library, Ms. Add. 27210) Pharaoh is represented as a Christian king, outfitted in an ermine cloak and golden crown. For more on this concept, see (Epstein 2011, esp. part one that focuses on the Birds’ Head Haggadah; and Harris 2005). |

| 24 | See the definitions and case study in (Weigert 2012). For important works on medieval performance and performativity, see the essays in (Gertsman 2008). Especially useful for the purposes of this paper is Sheingorn’s essay therein as well as (Sheingorn and Clark 2002). The question of the functionality of repetition in the language is explored in (Besch 1989). On the study of the medieval art of memory see (Carruthers 2008). Also useful is the compilation of medieval sources on the topic that Carruthers edited with Jan Ziolkowski in 2002 (Carruthers and Ziolkowski 2002). |

| 25 | For the expositor as alluded to in late medieval Christian imagery, see (Gertsman 2010, chp. 3; De Boor and Newald 1974, p. 168; see also Baxandall 1988, pp. 71–73), for a comparison between the Italian festaiuolo who appeared in Italian plays and choric figures in paintings. For a study of expositor figures, see (Butterworth 2007). |

| 26 | We might, perhaps, imagine him as something of a Seder leader (or “Seder expert”), the master of ceremonies, who, according to some sources, held a role distinct from that of the master of the house and may have helped guide the family through Passover rituals and prayers, perhaps at home, perhaps during synagogue services on the Great Shabbat—albeit, one would imagine, with less humor than articulated on the pages of the Hileq and Bileq Haggadah. For Ashkenazic customs, see (Kogman-Appel 2022, pp. 101–2; for Sephardic customs, see Schmelzer 2007, pp. 55–57). |

| 27 | Baraita of the Thirteen Middot, which opens the halakhic midrash on Leviticus, Sifra; (see Shoshana 1991). |

| 28 | There exists evidence of at least one Jewish playwright, Ezekiel of Alexandria, the author of Exagogue, a tragedy about Moses written around the second century BCE. Elsewhere, one finds representations of Mariam’s dance and various festive celebrations; for example, Mariam’s dance features prominently at the end of some biblical cycles in fourteenth-century Sephardic haggadot such as the Golden Haggadah (London, British Library, Ms. Add. 27210), and in an Italian copy of Maimonides’s Mishneh Torah (Vatican City, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Ross. 498). Fol. 85v includes dancing couples accompanied by a jester. Jesters also appear in the oeuvre of Joel ben Simeon, often as representations of the Fourth Son (see Kogman-Appel 2011, pp. 59, 93–96). |

| 29 | “They said about Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel that when he would rejoice at the Celebration of the Place of the Drawing of the Water, he would take eight flaming torches and toss one and catch another, juggling them, and, though all were in the air at the same time, they would not touch each other” (53a:7); “Apropos the rejoicing of Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel at the Celebration of the Place of the Drawing of the Water, the Gemara recounts: Levi would walk before Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi juggling with eight knives. Shmuel would juggle before King Shapur with eight glasses of wine without spilling. Abaye would juggle before Rabba with eight eggs. Some say he did so with four eggs” (53a:9). |

| 30 | This missive is derived from the writings of Rava (Abba ben Joseph bar Ḥama, who lived ca. 280–352 CE). See Megillah 7b:7–8 of the William Davidson digital edition of the Koren Noé Talmud (available at Sefaria, https://tinyurl.com/2s4362ud, accessed 28 April 2022). |

| 31 | Masekhet Purim, penned by Kalonymus ben Kalonymus, dates to the fourteenth century; it grew in popularity in subsequent centuries, especially in the 1500s, during the age of print. See (Haas 2011, p. 63). See also Masekhet Shikorim (Tractate of the Drunken Ones). For medieval Purim parodies and their persistence well into the eighteenth century, see the work of Roni Cohen: (Cohen 2021a, 2021b). |

| 32 | (See Gutmann 1974, pp. 29–30; Shalev-Eyni 2010). Antonius Margharita, a Hebraist and a Jewish convert to Christianity, describes it thusly in Der gantz jüdisch Glaub (Margharita 1530): “At the moment they open the door, someone who has disguised himself comes quickly into the room, as if he were [the prophet] Elijah himself who had to proclaim the gospel of their Messiah’s coming” (trans. in Gutmann 1974, p. 2). We should, however, be careful in putting trust into such sources, whose main remit was to perpetuate libelous accusations against Jewish communities. A copy of Antonius’s text that includes woodcuts by Johann Pfefferkorn can be found in the Graphic Arts Collection of Princeton University’s Firestone Library under the call number 2015-0879N. |

| 33 | Sheingorn is intentionally building on the work of gender performance and performativity explored by Judith Butler (see Butler 1993, esp. p. 234). See also (Sheingorn and Clark 2002). |

| 34 | The shelfmarks for the Second Nuremberg Haggadah, Yahuda Haggadah, and First Cincinnati Haggadah are listed in footnote 16. Other haggadot, such as the First New York Haggadah, may feature scrolls or unframed short passages near images, but they are captions or subject headers rather than indications of speech. The Hamburg Miscellany (1420s-38) includes books and scrolls with the answers to the Four Questions posed by the Four Sons on folios 25r and 25v as well as biblical citations in scrolls on the Shefokh page (fol. 35v), but these, again, carry a different function than the speech scrolls in the Hileq and Bileq manuscript. |

| 35 | In Ashkenaz, the group known as the Hasidei Ashkenaz predicted the coming of the Messianic era several times. For them, the year 1240 was marked as the dawning of the new age. In the Sephardic context, Nachmanides famously predicted the coming of the Messiah in 1403. On the equating witchcraft with Jews in late medieval and early modern German visual culture, see (Owens 2014). |

| 36 | (Epstein 2001, beginning on p. 299). As Epstein has rightly underscored, the metaphor of the mirror for the haggadah’s illuminations is especially apt, although one cannot take the images as direct reflections of rituals and customs, but rather as ideal or socially informed representations (p. 299). For Messianic themes in Sephardic manuscripts, see, e.g., (Frojmovic 2002). |

| 37 | (Turner 1974, p. 53; Grimes [1982] 1995) on the elision of theater and ritual; and (Schechner [1977] 2003, p. 130) on the difference between participating and watching audience. |

| 38 | Visual engagements with the experience of exile after the destruction of the Second Temple take a variety of forms in Jewish illuminated manuscripts. For more on destabilizing and/or appropriative iconographies, see, e.g., (Epstein 1997, esp. chp. 2; Kogman-Appel 2005, 2009; Frojmovic 2017, 2018; Offenberg 2018, 2021); and the work of Sarit Shalev-Eyni (e.g. Shalev-Eyni 2016, 2020). For the importance of the Jewish Diaspora in determining a “Jewish Middle Ages” as well as related problems of periodization, see (Skinner 2003). |

References

- Amirov, Franziska. 2018. Jüdisch-Christliche Buchmalerei im Spätmittelalter: Aschkenasische Haggadah-Handschriften aus Süddeutschland und Norditalien. Berlin: Deutscher Verlag für Kunstwissenschaft. [Google Scholar]

- Araújo, Rita, Paula Nabais, Isabel Pombo Cardoso, Conceição Casanova, Ana Lemos, and Maria J. Melo. 2018. Silver Paints in Medieval Manuscripts: A First Molecular Survey into their Degradation. Heritage Science 6: 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, Salo Wittmayer. 1952–1983. A Social and Religious History of the Jews. 18 vols. New York: Columbia University Press. First published 1937 as 3 vols. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgarten, Elisheva. 2016. Practicing Piety in Medieval Ashkenaz: Men, Women, and Everyday Religious Observance. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgarten, Elisheva. 2018. Appropriation and Differentiation: Jewish Identity in Medieval Ashkenaz. AJS Review 42: 39–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxandall, Michael. 1988. Painting and Experience in Fifteenth-Century Italy: A Primer in the Social History of Pictorial Style. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Besch, Elmar. 1989. Wiederholung und Variation: Untersuchung ihre stilistischen Funktionen in der deutschen Gegenwartssprache. New York: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Buda, Zsófia. 2012a. What Shall You Tell Your Children on That Day? Seder Eve in Fifteenth-Century Ashkenaz. In Ritual, Images, and Daily Life. The Medieval Perspective. Edited by Gerhard Jaritz. Münster: LIT Verlag, pp. 173–90. [Google Scholar]

- Buda, Zsófia. 2012b. Sacrifice and Redemption in the Hamburg Miscellany: The Illustrations of a Fifteenth-Century Ashkenazi Manuscript. Ph.D. dissertation, Central European University, Budapest, Hungary, April. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, Judith. 1988. Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory. Theatre Journal 40: 519–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, Judith. 1993. Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of ‘Sex’. New York: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Butterworth, Philip. 2007. The Narrator, the Expositor, and the Prompter in European Medieval Theatre. Turnhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Carruthers, Mary J. 2008. The Book of Memory: A Study of Memory in Medieval Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carruthers, Mary J., and Jan Ziolkowski, eds. 2002. The Medieval Craft of Memory: An Anthology of Texts and Pictures. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Adam S. 2016. La Haggadah multi-sensorielle. In Les cinq sens au Moyen Âge. Edited by Éric Palazzo. Paris: Les Éditions du Cerf, pp. 305–31. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Adam S. 2018. Signs and Wonders: 100 Haggadah Masterpieces. New Milford: The Toby Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Roni. 2021a. Carnival and Canon: Medieval Parodies for Purim. Ph.D. dissertation, Tel-Aviv University, Tel-Aviv, Israel. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Roni. 2021b. From Ridicule to Ritual: Standardization and Canonization Processes in the Transmission of Purim Parodic Literature. Medioevi 7: 225–49. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Roni. 2021c. “Cursed be Haman?”: Haman as a Victim in the 14th Century Parody Massekheth Purim. In Troubling Topics, Sacred Texts: Readings in Hebrew Bible, New Testament, and Qur’an. Edited by Roberta Sterman Sabbath. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 469–92. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, Israel. 1966. Parody in Jewish Literature. New York: AMS Press. First published 1906. [Google Scholar]

- De Boor, Helmut, and Richard Newald. 1974. Geschichte der deutschen Literatur von den Anfängen bis zur Gegenwart. Munich: Beck. [Google Scholar]

- Enders, Jody. 2001. Of Miming and Singing: The Dramatic Rhetoric of Gesture. In Gesture in Medieval Art and Drama. Edited by Clifford Davidson. Kalamazoo: Medieval Institute Publications, pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, Marc Michael. 1997. Dreams of Subversion in Medieval Jewish Art and Literature. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, Marc Michael. 2001. Illustrating History and Illuminating Identity in the Art of the Passover Haggadah. In Judaism in Practice: From the Middle Ages through the Early Modern Period. Edited by Lawrence Fine. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 298–317. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, Marc Michael. 2011. The Medieval Haggadah: Art, Narrative, and Religious Imagination. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fisch, Harold. 1994. Reading and Carnival: On the Semiotics of Purim. In Purim and the Cultural Poetics of Judaism—Theorizing Diaspora. Edited by Daniel Boyarin. Special issue, Poetics Today, 15: 55–74. [Google Scholar]

- Frojmovic, Eva. 2002. Messianic Politics in Re-Christianized Spain: Images of the Sanctuary in Hebrew Bible Manuscripts. In Imagining the Self, Imagining the Other: Visual Representation and Jewish-Christian Dynamics in the Middle Ages and Early Modern Period. Edited by Eva Frojmovic. Leiden: Brill, pp. 91–128. [Google Scholar]

- Frojmovic, Eva. 2017. Neighbouring and Mixta in Thirteenth-Century Ashkenaz. In Postcolonising the Medieval Image. Edited by Eva Frojmovic and Catherine E. Karkov. New York: Routledge, pp. 241–60. [Google Scholar]

- Frojmovic, Eva. 2018. Christian Illuminators, Jewish Patrons, and the Gender of the Jewish Book. Ars Judaica 14: 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garel, Michel. 1991. D’une main forte: Manuscrits Hébreux des Collections Françaises. Catalogue entry 108. Paris: Seuil. [Google Scholar]

- Gertsman, Elina, ed. 2008. Visualizing Medieval Performance: Perspectives, Histories, Contexts. Farnham: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Gertsman, Elina. 2010. The Dance of Death in the Middle Ages: Image, Text, Performance. Studies in the Visual Cultures of the Middle Ages. Turnhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Grayzel, Solomon. 1989. The Church and the Jews in the XIIIth Century. Edited and arranged by Kenneth R. Stow. New York: Jewish Theological Seminary of America, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Grimes, Ronald L. 1995. Beginnings in Ritual Studies. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press. First published 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Gutmann, Joseph. 1967–1968. When the Kingdom Comes, Messianic Themes in Medieval Jewish Art. Art Journal 27: 165–82. [Google Scholar]

- Gutmann, Joseph. 1974. The Messiah at the Seder: A Fifteenth-Century Motif in Jewish Art. In Studies in Jewish History: Presented to Professor Rapahel Mahler on His Seventy-Fifth Birthday. Edited by Shmuel Yeivin. Merhavia: Sifriyat Poalim, pp. 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Haas, Peter J. 2011. Masekhet Purim. In Jews and Humor. Edited by Leonard J. Greenspoon. West Lafyette: Purdue University Press, pp. 55–65. [Google Scholar]

- Hage, Ghassan. 2010. Migration, Food, Memory, and Home-Building. In Memory: Histories, Theories, Debates. Edited by Susannah Radstone and Bill Schwarz. New York: Fordham University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hammer, Reuven. 2011. Hallel: A Liturgical Composition Celebrating the Exodus. In The Experience of Jewish Liturgy: Studies Dedicated to Menahem Schmelzer. Edited by Debra Reed Blank. Leiden: Brill, pp. 101–13. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, Julia A. 2002. Polemical Images in the Golden Haggadah, BL, Add. MS 27210. Medieval Encounters 8: 105–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, Julia A. 2005. Good Jews, Bad Jews, and No Jews at All––Ritual Imagery and Social Standards in the Catalan Haggadot. In Church, State, Vellum, and Stone: Essays on Medieval Spain in Honor of John Williams, The Medieval and Early Modern Iberian World. Edited by Julie A. Harris and Therese Martin. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 275–96. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, Julia A. 2013. Love in the Land of Goshen: Haggadah, History, and the Making of BL MS Or. 2737. Gesta 52: 161–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, Julia A. 2015. Making Room at the Table: Women, Passover, and the Sister Haggadah (London, British Library, MS Or. 2884). Journal of Medieval History 42: 131–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindman, Sandra, and Sharon Liberman Mintz. 2020. I am the Scribe, Joel ben Simeon. Paris: Les Enluminures. [Google Scholar]

- Isserles, Justine. 2005–2008. De la Sortie d’Égypte à la Rédemption finale: Analyse de cinq folios tirés du manuscrit Hébreu 1333 de la Bibliothèque nationale de France à Paris. Cahiers Archéologiques 52: 145–60. [Google Scholar]

- Kogman-Appel, Katrin. 2005. The Tree of Death and the Tree of Life: The Hanging of Haman in Medieval Jewish Manuscript Painting. In Between the Image and the Word: Essays in Honor of John Plummer. Edited by Colum Hourihane. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, pp. 187–208. [Google Scholar]

- Kogman-Appel, Katrin. 2009. Christianity, Idolatry, and the Question of Jewish Figural Painting in the Middle Ages. Speculum 84: 73–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kogman-Appel, Katrin. 2011. The Illustrations of the Washington Haggadah. In The Washington Haggadah: Copied and Illustrated by Joel ben Simeon. Introduced and translated by David Stern. Washington, DC: The Library of Congress, pp. 52–113. [Google Scholar]

- Kogman-Appel, Katrin. 2015. The Audiences of the Late Medieval Haggadah. In Patronage, Production, and Transmission of Texts in Medieval and Early Modern Jewish Cultures. Edited by Jonathan Decter and Esperanza Alfonso. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 99–143. [Google Scholar]

- Kogman-Appel, Katrin. 2016. Joel ben Simeon Looking at the Margins of Society. In Intricate Interfaith Networks in the Middle Ages: Quotidian Jewish-Christian Contacts. Edited by Ephraim Shoham-Steiner. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 287–314. [Google Scholar]

- Kogman-Appel, Katrin. 2020. “And You Shall Tell Your Son on this Day”: Visual Didactics in Medieval Illustrated Haggadot. In Prodesse et Delectare. Case Studies on Didactic Literature in the European Middle Ages/Fallstudien zur didaktischen Literatur des Europäischen Mittelalters. Edited by Norbert Kössinger and Claudia Wittig. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 138–73. [Google Scholar]

- Kogman-Appel, Katrin. 2021. Ritual Imagery Gone Wrong: A Fifteenth-Century Siddur in a Christian Workshop. In Exegetical Polarities in Medieval Jewish Cultures. Edited by Nabih Bashir, Ehud Krinis, Sara Offenberg and Shalom Sadik. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 467–505. [Google Scholar]

- Kogman-Appel, Katrin. 2022. Visualizations of Ritual in Medieval Book Culture. In Routledge Handbook of Jewish Ritual and Practice. Edited by Oliver Leaman. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Landsberger, Franz. 1948. The Washington Haggadah and Its Illuminator. Hebrew Union College Annual 21: 73–103. [Google Scholar]

- Langer, Ruther. 2011. Cursing the Christians? A History of the Birkat Haminim. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, Shimon. 1999. Theatre and Holy Script. Brighton: Sussex Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lipton, Sara. 1999. Images of Intolerance: The Representation of Jews and Judaism in the Bible moralisée. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Malkiel, David J. 1993. Infanticide in Passover Iconography. Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 56: 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margharita, Antonius. 1530. Der gantz jüdisch Glaub. Augsburg: Heinrich Stayner. [Google Scholar]

- Matt, Daniel C. 2022. Becoming Elijah: Prophet of Transformation. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Narkiss, Bezalel, and Gabrielle Sed-Rajna. 1981. Index of Jewish Art. Munich: K. G. Saur, vol. II/1. [Google Scholar]

- Offenberg, Sara. 2015. Staging the Blindfolded Bride: Between Medieval Drama and Piyyut Illumination in the Levy Mahzor. In Resounding Images: Medieval Intersections of Art, Music, and Sound. Edited by Susan Boynton and Diane J. Reilly. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 281–94. [Google Scholar]

- Offenberg, Sara. 2018. Animal Attraction: Hidden Polemics in Biblical Animal Illuminations of the ‘Michael Mahzor’. Interfaces 5: 129–53. [Google Scholar]

- Offenberg, Sara. 2020. Beauty and the Beast: On a Doe, a Devilish Hunter, and Jewish-Christian Polemics. AJS Review 44: 269–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Offenberg, Sara. 2021. Daniel in the Lions’ Den: Jewish-Christian Polemics in Medieval Text and Image. In Exegetical Polarities in Medieval Jewish Cultures. Edited by Nabih Bashir, Ehud Krinis, Sara Offenberg and Shalom Sadik. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 413–34. [Google Scholar]

- Owens, Yvonne. 2014. The Saturnine History of Jews and Witches. In Capturing Witches. Edited by Alison Findley and Liz Oakley-Brown. Special issue, Preternature 3: 56–84. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, Pamela A. 2012. Art of Estrangement: Redefining Jews in Reconquest Spain. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ricciardi, Paola, and Kristine Rose Beers. 2020. The Illuminators’ Palette. In The Art and Science of Illuminated Manuscripts: A Handbook. Edited by Stella Panayotova. London: Harvey Miller Publishers, pp. 26–39. [Google Scholar]

- Rochmes, Sophia R. 2022. Illuminating Luxury: The Gray-Gold Flemish Grissailles. In Illuminating Metalwork: Metal, Object, and Image in Medieval Manuscripts. Edited by Joseph Salvatore Ackley and Shannon L. Wearing. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 275–99. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenwald, Lawrence. 2020. Shefokh Ḥamatkha. In Hebrew College Passover Companion in Honor of Judith Kates. Edited by Rachel Adelman, Jane L. Kanarek and Gail Twersky Reimer. Brookline: Hebrew College, pp. 54–56. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenwein, Barbara. 2002. Worrying about Emotions in History. The American Historical Review 107: 821–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenwein, Barbara. 2006. Emotional Communities in the Early Middle Ages. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenwein, Barbara. 2010. Problems and Methods in the History of Emotions. Passions in Context: Journal of the History and Philosophy of Emotions 1: 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenwein, Barbara. 2016. Generations of Feeling: A History of Emotions, 600–1700. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, Nina. 2011. The Jew, the Cathedral, and the Medieval City: Synagoga and Ecclesia in the Thirteenth Century. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rubenstein, Jeffrey. 1992. Purim, Liminality, and Communitas. AJS Review 17: 247–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schechner, Richard. 2003. Performance Theory. New York: Routledge. First published 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Schmelzer, Menahem. 2007. The Liturgy of the Prato Haggadah. In The Prato Haggadah. Edited by David Charles Kraemer and Naomi M. Steinberger. New York: Jewish Theological Seminary, pp. 53–67. [Google Scholar]

- Sed-Rajna, Gabrielle, and Sonia Fellous. 1994. Les manuscrits hébreux enluminés des bibliothèques de France. Catalogue entry 99. Leuven: Peeters, pp. 248–55. [Google Scholar]

- Segel, Eliezer. 2007. The Purim-Shpiel and the Passion Play. In In Those Days, at This Time: Holiness and History in the Jewish Calendar. Calgary: University of Calgary Press, pp. 127–32. [Google Scholar]

- Shacham-Rosby, Chana. 2016. Elijah the Prophet: The Guard Dog of Israel. Jewish History 30: 165–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalev-Eyni, Sarit. 2010. Jews Among Christians: Hebrew Book Illuminations from Lake Constance. London: Harvey Miller Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Shalev-Eyni, Sarit. 2016. Entanglement and Disentanglement. Visual Expressions of Late Medieval Ashkenazi Existence. In Transkulturelle Verflechtungsprozesse in der Vormoderne. Edited by Wolfram Drews and Christian Scholl. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 174–196. [Google Scholar]

- Shalev-Eyni, Sarit. 2018. Manipulating the Cup of Blessing: Gendered Reading of Ritual Images in European Hebrew Books. Studies in Iconography 39: 207–34. [Google Scholar]

- Shalev-Eyni, Sarit. 2020. Isaac’s Sacrifice: Operation of Word and Image in Ashkenazi Religious Ceremonies. Entangled Religions: Interdisciplinary Journal for the Study of Religious Contact and Transfer 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheingorn, Pamela, and Robert Clark. 2002. Performative Reading: The Illustrated Manuscripts of Arnoul Gréban’s Mystère de la Passion. European Medieval Drama 6: 136–40. [Google Scholar]

- Sheingorn, Pamela. 2008. Performing the Illustrated Manuscript: Great Reckonings in Little Books. In Visualizing Medieval Performance: Perspectives, Histories, Contexts. Edited by Elina Gertsman. Farnham: Ashgate, pp. 57–82. [Google Scholar]

- Shoham-Steiner, Ephraim. 2009. Pharaoh’s Bloodbath: Medieval European Jewish Thoughts about Leprosy, Disease, and Blood Therapy. In Jewish Blood: Reality and Metaphor in History, Religion, and Culture. Edited by Mitchell B. Hart. London: Routledge, pp. 99–115. [Google Scholar]

- Shoshana, Abraham, ed. 1991. Sifra on Leviticus According to Vatican Manuscript Assemani 66. Jerusalem: Ofeq Institute, vol. 1: Baraita de-R. Ishmael. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner, Patricia. 2003. Confronting the ‘Medieval’ in Medieval History: The Jewish Example. Past and Present, 219–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]