1. Introduction

What happened to the human soul in contemporary theories of preaching? The field of homiletics shows a wide variety of themes, approaches, perspectives, and theologies. Somewhere between the critical theory, postcolonial, and post-human approaches on the one hand, and meaning making, cultural Christianity, and lived religion on the other hand, the issue of humanity re-emerges. This essay inquires whether and how this anthropological issue is served by a reappropriation of the notion of the human soul.

For centuries, sermons have referred to the human soul. As an example, I use a dataset with sermons from two nineteenth-century world-famous British preachers, John Henry Newman, who converted from Anglicanism to Roman Catholicism and was made cardinal in 1879, and Charles Haddon Spurgeon, a Baptist pastor who became known as the ‘prince of preachers’ during his 37-year preaching career.

1 A collocation display

2 shows how they talk about the soul in very different ways. With respect to the term ‘soul’, the collocation ‘

the soul’ is the most frequent co-occurrence in Newman’s and Spurgeon’s sermons. Then there are collocations with a personal pronoun: ‘our souls’, ‘his soul’ and ‘your soul’. For both preachers, the soul is often used in combination with a personal pronoun. Thirdly, the soul appears in combination with an adverb. In those cases, soul is the used to refer to a human being: a regenerate, immortal, sinful, trembling, troubled, believing, seeking, or faithful soul. These three aspects point to similarities in the way the soul occurs in their sermons.

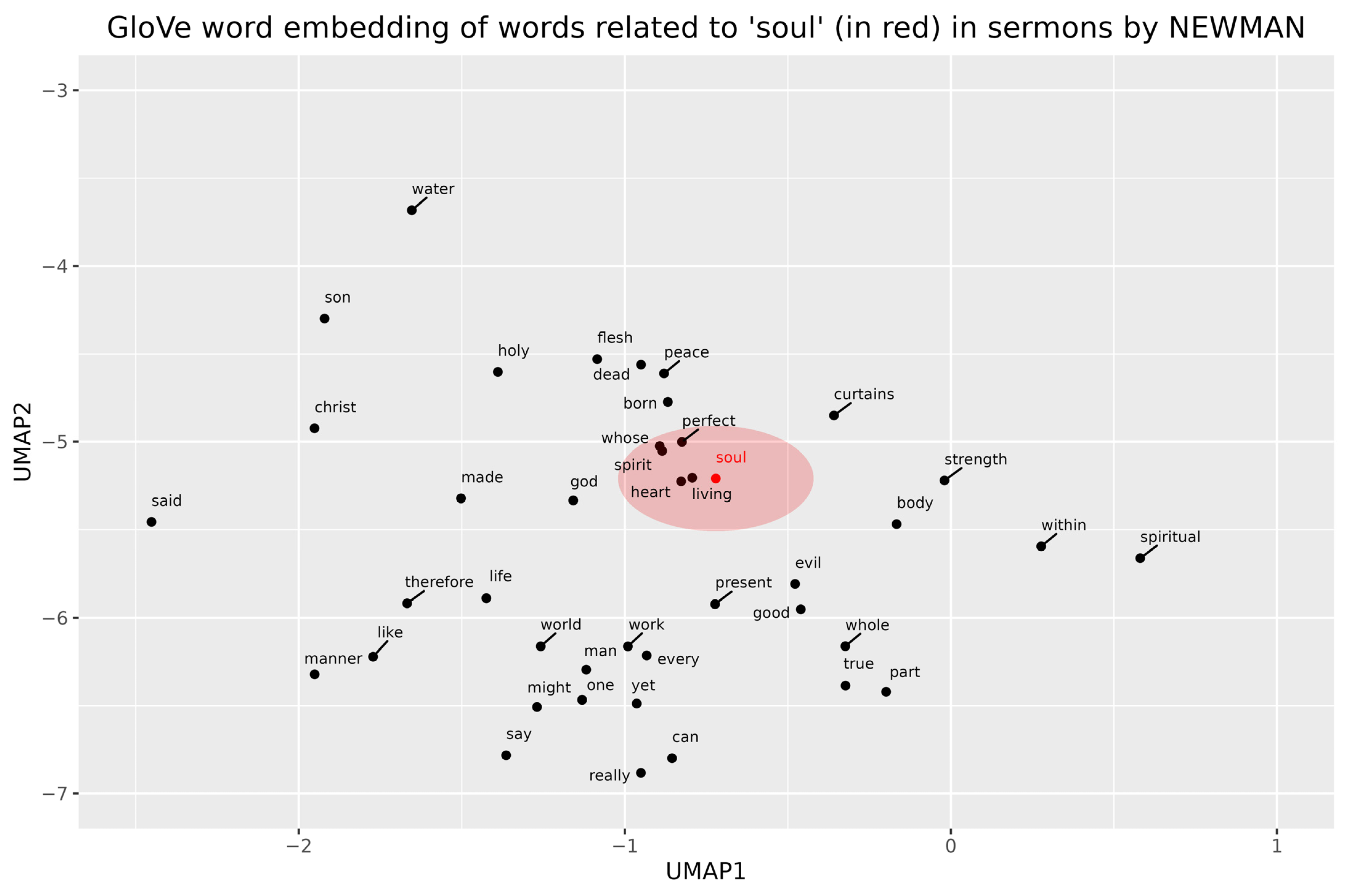

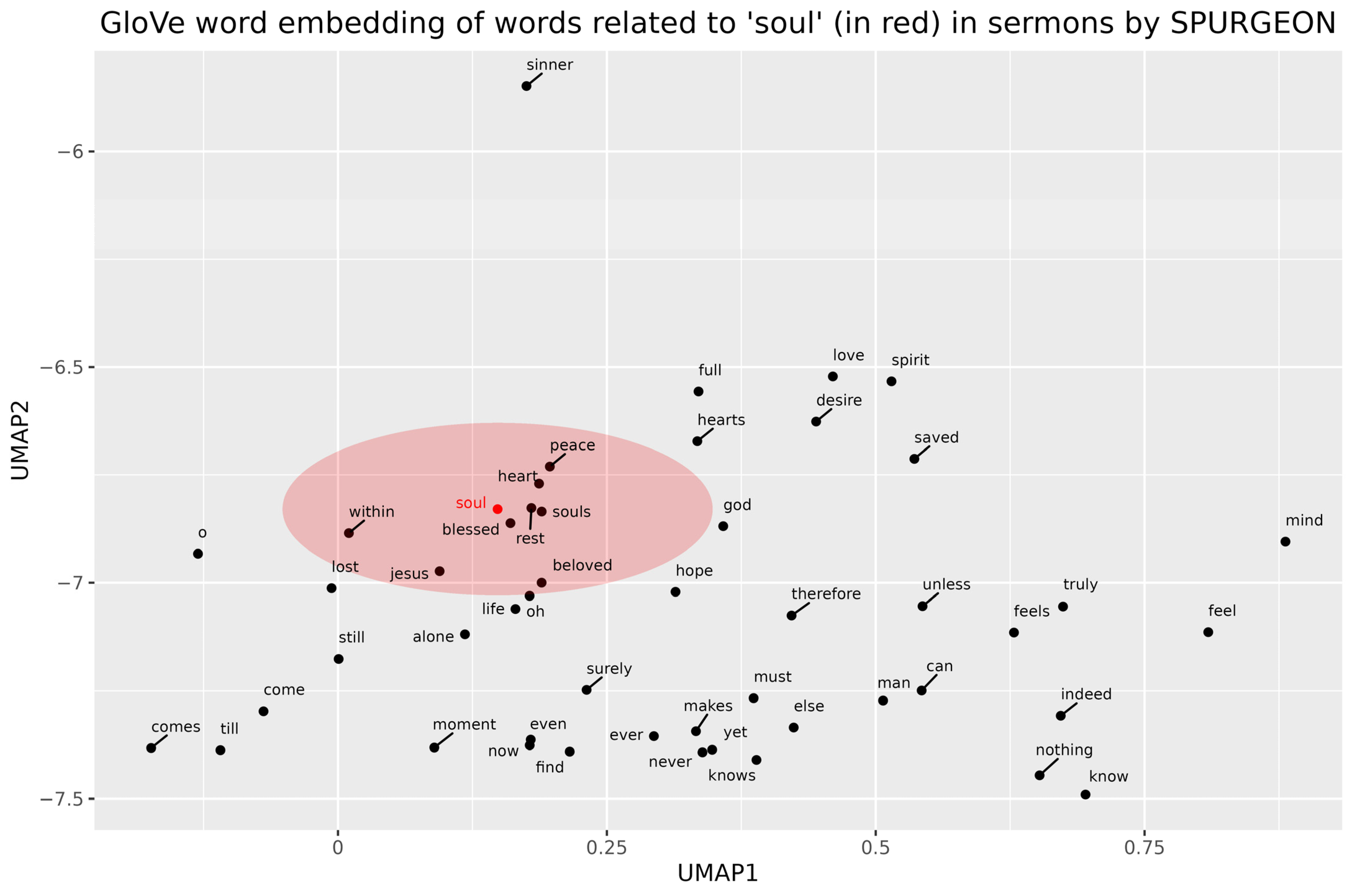

However, a semantic network of terms also points to the differences. Semantic networks can be produced by a method called ‘word embeddings’, a computational method that measures the distances between terms by calculating vectors (

van Atteveldt et al. 2022, chp. 10.3.3). For each preacher, the distances between the term ‘soul’ and its semantic neighbours were plotted (The plots are produced using R (

R Core Team 2021) and the packages Quanteda, Text2Vec, and GGPlot2):

Close to ‘soul’ in Newman’s vocabulary are terms such as ‘body’, ‘heart’, ‘living’, and ‘god’ (

Figure 1). For Spurgeon, the picture is a bit different. Close to ‘soul’ in his sermons are terms like ‘beloved’, ‘within’, ‘heart’, ‘peace’, and ‘Jesus’ (

Figure 2). These representations can suggest hypotheses on the language of preaching and the theology expressed in sermons.

Yet, the nineteenth century is history. It also appears that the language of the soul in sermons is largely history. In this essay, I open up a conversation about the place of the soul in preaching in homiletics. I start with a brief story of the disappearance of the soul, not only for preaching as an isolated religious practice but in close relation to the practice of pastoral care and counselling. Next, I propose a homiletical framework that aims to retrieve the language of the soul. Then I reflect on pastoral preaching as a mode of preaching with an eye for the soul. Finally, I outline a brief homiletical agenda with a few conditions for retrieving the soul in the practices of preaching.

2. The Soul in Preaching: Questioned, Deleted, and Superseded

The idea of the soul has been a longstanding subject of investigation in theological anthropology. Nonetheless, it has been widely criticised in modern theology and philosophy. The duality between soul and body—and in some versions, a triad of soul, spirit, and body—was traced back to its Greek origins. The position that distinguished between the soul and the body achieved a conceptual life by referring to that position as ‘substance dualism’ and one of the criticisms of substance dualism has been its neglect of the body. For philosophers of religion, systematic theologians, and biblical scholars alike, the turn towards the body has encouraged scholars either to reject the concept of the soul or at least to neglect it. An example of the former can be found in Nancy Murphy’s work (

Murphy 2006); an example of the latter is Kevin Vanhoozer’s essay ‘Human being, individual and social’ in the

Cambridge Companion to Christian Doctrine (

Vanhoozer 1997).

Against the widespread rejection or neglect of the soul in contemporary theological discourse, counter-voices are increasingly being heard. For instance, in his response to Tom Wright’s rejection of the soul, Brandon L. Rickabaugh argues that substance dualist positions are often unsatisfactorily dealt with because they do indeed stress that “the soul cannot flourish or naturally function without a body” (

Rickabaugh 2018, p. 212). He does re-open the discussion. Similarly, in a recent thesis, Martine Oldhoff engaged with biblical scholarship and systematic theological conceptions in relation to the soul. She argued against a Platonic uncreated soul; they do not have eternal life in themselves. Drawing from mystical theology, she refers to the function of the soul as it “anchors the unique subjectivity of human beings” without denying the unity of body and soul, and she sketches the contours of the soul as a mode of human relatedness to God: “created by God, dependent on God and ontologically distinct from God” (

Oldhoff 2021, pp. 281–82). She locates the relevance for the soul in theological discourse in the Pauline language of transformation which requires an ‘I’ and in the resurrection of Christ that affirms this ‘I’ that is both created by God and maintained by God at the other side of death. Rickabaugh and Oldhoff are two contemporary thinkers who simultaneously deal with the objections that have been raised against different versions of dualism but maintain a

duality in humans. They argue that the soul is incomplete without embodied existence. Further, the interdependency of soul and body is accompanied by another type of interdependency: the soul’s dependence upon its Creator. The soul gets its life from God (Hebrew:

Nefesh), and it can only flourish in relation to God. In other words, the soul is my ‘I-in-its-relation-to-God’, regardless of whether this relationship is affirmed from my side or not.

This far too brief reference to the much more detailed and nuanced story of the soul in theological anthropology poses a question for homiletics. If the soul points to the ‘I’, the inner core of humans, what happened to the theological ‘I’ in theories of preaching? To some extent, the so-called ‘turn to the listener’ in homiletics has put theological anthropology back into the homiletician’s attention. The sermon should engage the listeners and should relate to the everyday life of listeners. Both the questioned soul and the retrieved soul in theological discourse puts the question of the homiletical ‘I’ again on the table. Not the ‘I’ of the preacher this time, but the ‘I’ of the listener. Who is the listener and what happens with or to the ‘I’ of the listener in preaching?

But, first, what are the alternatives once the soul is rendered obsolete in scholarly discourse? Three perspectives need to be considered: narrativity, science, and post-humanism. Each of these perspectives has found its way into homiletics.

In the course of Western thinking, the soul has gradually turned into a self. This story has been told very often, but one of its most persuasive versions is Charles Taylor’s. The opening sentences of his

Sources of the Self illustrates the demise of the soul immediately when Taylor introduces his project of the making of ‘modern identity’ as the quest to find out “what it is to be a human agent, a person, or a self” (

Taylor 1992, p. 3). The route in Western thinking from St. Augustine to the French Renaissance writer Montaigne was a journey from the self-understanding of humans in relation to the Creator God towards a modern subject that understands itself in relation to its own inner world. The human self is a ‘narrative self’. Paul Ricoeur talks about the ‘narrative unity’ of a life which, according to Ricoeur, “must be seen as an unstable mixture of fabulation and actual experience” (

Ricoeur 1995b, p. 162). This is especially so in the face of death and Ricoeur refers to the role of literature:

Do not the narratives provided by literature serve to soften the sting of anguish in the face of the unknown, of nothingness, by giving it an imagination the shape of this or that death, exemplary in one way or another? Thus fiction has a role to play in the apprenticeship of dying. The meditation on the Passion of Christ has accompanied in this way more than one believer to the last threshold.

The narrative identity is fundamentally open; we do not know how to tell the end of the story. Ricoeur serves a homiletical implication on top of his suggestion of the importance of literature—that can be conceived of as a reservoir of stories—for the narrative self. He uses the meditation on Christ’s suffering as a story that helps the believer to imagine the end of one’s narrative identity. Extrapolating Ricoeur’s suggestion here leads to a fundamental homiletical insight: preaching retells the narrative of Christ (or: the story of the gospel) to shape the believer’s narrative identity. Ricoeur’s idea of ‘narrative identity’ has superseded the ancient idea of the soul as a central concept in theological anthropology. The focus on narrative preaching in contemporary homiletics fits this pattern.

Next, science has come up with another alternative for the soul. Research in neuroscience has challenged soul-talk to a large extent. Nancy Murphy proposed that so-called nonreductive physicalism may be a better theory to understand the human person from a Christian point of view. She is one of the authors who have extensively dealt with the results of modern neuroscience for theological reasoning. Neuroscientific insights have stressed the central role of the brain for all human mental and emotional capabilities. Within this paradigm, the soul has become obsolete to account for human individuality and activity since most of human behaviour, thinking, and feeling can be explained with reference to brain states. Among others, Murphy explains that Christians do not need the soul. In her book

Bodies and Souls, or Spirited Bodies she challenged what she calls the ‘partitive account’ of human nature, as if humans consist of different ‘parts’, such as a body and a soul. Rather, she understands humanity in terms of “their relationships—relationships to the community of the believers and especially to God” (

Murphy 2006, p. 22). Rather than a loss, she considers this a positive correction to what has haunted Christianity for centuries and has had negative consequences for Christian spirituality: it cultivated otherworldliness and excessive inwardness. Instead, a Christian’s life is an embodied life. Murphy’s position—perhaps better fitting within her Anabaptist tradition rather than a Calvinist or Catholic theology she admits—very much resonates with a renewed interest in embodied existence and materiality. Contemporary homiletics shares this theological interest in two ways. First, theories of preaching have increasingly paid attention to the

ethical. Not only in relation to human behaviour, but also in paying attention to bodily differences between humans, such as race, gender, and disability. Second, in the light of evil in the world, preaching addresses the human condition as a bodily condition. Prophetic traditions in preaching have shaped sermons to critique systems and political structures in the real world. Preaching should address embodied existence and the material world rather than, to cite Murphy again, “otherworldliness and excessive inwardness” (

Murphy 2006, p. 37).

Ultimately, the final scholarly paradigm to consider follows the path of prophesy but in a different way. Narrativity and science have reconstructed human nature as storied or embodied existence, respectively. However, the final paradigm to consider takes on a different prophetic robe: it proclaims an end to theological anthropology. Two major topics dominate the current intellectual climate, both politically and philosophically: ecology and digitalisation. Both topics seriously envision a future without humanity as we know it. They move us beyond an anthropocentric understanding of the world and the future. First, the climate crisis raises the issue of whether the age of humans is coming to an end. The Anthropocene has led to major crises both in our relationship to the planet and in our relationship to non-human beings. Second, the perspective of post-humanism widens when we take into account the technological developments that gave birth to artificial intelligence (

Jung 2022). We are not done yet with processing the impact of the current versions of generative systems such as GPT-4 and its popular interface in ChatGPT; the developments still continue to produce even stronger systems. Hence, after the Second World War, the Cold War, and the invention of nuclear weapons, for the first time in history the real possibility for humans has opened up to self-destruct the entire human race.

The Anthropocene has called our attention to the imminent destruction of the planet and digital technology travels the road of self-destruction by the invention of hyper-intelligent systems. In what sense do these ecological and technological states of affairs challenge the theory of preaching? Homiletics increased its scholarly urgency in the face of the ecological crisis and the need to pay attention to creation and the non-human world. Further, the digital age has moved homiletics into researching the impact of digitalisation upon the practices of preaching. This includes reflection on the agents and the role of technology in contemporary practices of preaching as well as the way preaching transforms when it enters digital media.

In the story of the soul in preaching, another aspect is worth looking at. Narrativity, scientific, and technology each contributed, though in very different ways, to the disappearance of the soul in theological discourse. But what about the homiletical textbooks?

In his handbook of preaching, Alexandre Vinet (1797–1847) adopts a classic rhetorical approach to preaching. Quoting Cicero (“quid aliud est eloquentia nisi motus animae continuus”), Vinet argues that through speaking well, the soul will be moved:

It is part of the orator then, to give the soul the movement which it requires, a movement tending to a certain end. But in what consists this movement? It consists in the hearer’s proceeding from indecision, from indifference, from torpor of will, to a full determination, which has place in the proportion to which the soul unites itself more closely to the truth which is presented to it.

Vinet’s argument consists of a close harmony between rhetoric and pre-modern psychology. The prime interest of the preacher is to move the soul of the listener into the direction of truth, although truth is far more than cognitive and propositional according to Vinet’s nuanced and detailed application of the rules of rhetoric to preaching.

However, more than a century later, homiletics presented a ‘turn to the listener’. In the light of history, this is a slight exaggeration and perhaps more a reaction against early twentieth-century theories of preaching. The rhetorical tradition already demonstrated a deep interest in the hearer. However, the turn to the listener comprised at least two ideas that made it very different from the nineteenth-century reflections on the soul and the rhetoric of the sermon. First, the empirical turn has put the everyday existence of the listener in the centre of homiletical attention. The everyday life appears in sermons, in narratives, in real-life examples, and in concrete reflections of the many worlds the hearers inhabit: the worlds of culture, politics, ethics, and, of course, religion. Second, the movement in the sermon became an experiential event. The American preaching movement, which was later called ‘the new homiletic’, was especially known for this emphasis. Narrative, inductive movement, and imagination were key notions in the work of David Buttrick, Fred Craddock, and Eugene Lowry—to name a few of its ‘founding fathers’.

The turn to the listener, however, was followed by other turns. Among those, the postcolonial turn should be mentioned. In her seminal work on a postcolonial homiletics, HyeRan Kim-Cragg talks about the ‘ripple effect’. Once a stone hits the water, it creates concentric circles. The sermon does not just move individuals, not even an individual preacher. Imagination in the sermon is not a technique to involve individual listeners, to reflect their lifeworlds, or invite them into an individual transformative event. “The work of homiletical imagination is intertwined with the imagination of the community. It largely depends on the wisdom dwelling in the community rather than a special gift or ability of the preacher”, she writes (

Kim-Cragg 2021, p. 32).

At this point and after many turns, approaches, and emphases, homiletics has discovered the thoroughly social and cultural location of humans, but it has also deepened its knowledge into the areas of science, technology, and digitalisation. In this turmoil of developments in homiletical theory, the idea of the soul gradually disappeared. Can we do without it and what gets lost in homiletics if preaching loses the soul?

3 3. Preaching as Soulful Communication between Souls

There may not be a problem with a homiletics without human souls. Let us be honest, ChatGPT can indeed produce sermons, maybe even more coherent and structured pieces of discourse than many preachers are able to construct, although it has been remarked that computer-generated sermons lack ‘soul’, a phrase popping up in many news articles that quote Hershael York in reflecting upon the use of ChatGPT to produce a sermon (

Morris 2023). Further, St. Francis preaching to the animals fits the biblical record that ‘soul’ in the Hebrew Scriptures (

nefesh) is attributed both to humans and animals; it does not denote some immortal seat of moral intellect but points to God’s life-giving breath that animals and humans equally share. That Francis preached to the animals demonstrates that he did not think that the gospel was spoiled when proclaimed to non-human souls. Finally, some versions of Pietism have fostered an unhealthy fixation on the future destiny of the individual soul at the expense of embodied existence in the here-and-now. It has left quite a few souls rather troubled. So, what can we say about preaching and the human soul?

In what follows, I propose a few aspects of a constructive account for retrieving the language of the soul in our theories of preaching. The proposal consists of three steps: describing a homiletical-theological framework, reflecting upon the function of preaching, and exploring the conditions for preaching.

First, I sketch a homiletical framework that takes into account recent arguments in favour of (some version of) dualism. In preaching, we deal with the body and the soul as two mutually dependent aspects of being human. We may assume that the most basic homiletical framework consists of two aspects, the actors in preaching—the preacher and the hearers—and the act of preaching—the actual communicative event. The language of the soul applies to both aspects.

The first aspect of the homiletical framework has to do with the involved actors. In any preaching event, both the preacher and the hearers are embodied souls. Their bodily presence—whether visually perceived or present at a different location, as in some cases of digital preaching—affects the performance of preaching and the event of listening. Feminist and womanist homileticians have called attention to the importance of the body of the preacher in the act of preaching. Studies in the reception of preaching have emphasised the relevance of the bodies of the hearers in the preaching event. The body is more than the material extension of a human being, its physical appearance, or condition. Brain research has emphasised the interconnectedness of our bodily existence and our psychological functioning. To a significant extent, psychological processes can be attributed to complex neurological responses in our bodies. Physicalism, whether in its reductive or nonreductive versions, can sufficiently attest to the major features of the actors involved in the preaching event. Yet, when considering the actors in preaching, a homiletical framework needs to extend towards reflections on spirituality, faith, and existential existence that cannot be reduced to brain states or other aspects of embodiment. This moment could be located in the

relationship to God. For the preacher, this concerns the interaction of the preacher’s life in relation to the content of the sermon: the sermon contains references to the reality of God as intended by the preacher. Preaching is God-talk by a human being living within a relationship with God. On the part of the listener, we speak about the religious involvement of the listener: in the preaching event, the listener understands life in relation to the Divine, experiences God’s grace, or becomes motivated to act according to the Gospel (

Pleizier 2010). In other words, inasmuch as the preaching event is an embodied instance of human communication, the souls of the preacher and the audience are also involved.

The second aspect of the homiletical framework is the act of communication itself. Preaching as the living voice of the Gospel (‘viva vox evangelii’) has its own communicative mode. The sermon communicates life.

Nefesh, the Hebrew term that is often translated as ‘soul’, could also be translated as ‘life’. Its bodily reference is that of the ‘throat’, the organ of breath (

Weissenrieder and Dolle 2019). Its story of origin is the second creation story in Genesis 2: God breathed into the nostrils of the human that was formed from the dust of the earth, and the human became a living creature. Life was communicated from the breath of God. God’s breath seems to be even more intimate than God’s voice. The first creation story (Gen 1:1–2:3) tells about God who speaks into being all creatures, non-human and human. The second creation story (Gen 2:4–25) starts with God breathing life into what has been called into being. A human being becomes a living soul through the life-giving breath of God, an ‘I-in-relation-to-God’. This aspect of the creation story is also relevant for understanding the nature of preaching. It puts the communicative mode of preaching in the perspective of the life-giving work of God’s Spirit. Soulful preaching emerges from the interaction between the words spoken by the preacher, the interpretative activity of the hearers, and the Spirit who moves in the in-between space of the speaking and hearing. This defines the act of communication in preaching. The language of the soul reminds us of the life-giving force that is operative in the preaching event. We need a pneumatological articulation here. The breath of life in creation,

nefesh through which humans became living beings, has its counterpart in the practice of preaching. Preaching is human communication. Simultaneously, the preaching event is much more than that. Through the language of the sermon, which—according to Richard Lischer—is supposed to be a language of peace (

Lischer 2005), God communicates grace, forgiveness, and renewal. In the act of preaching, God’s promise is communicated. The breath of life that comes from God is part of creation—as human speech emerges from the created world. This breath of life, however, is also a renewing force, an act of the Spirit of God and not of human making—not even the preacher’s. The soul of the sermon is Spirit-breathed life.

Sermons can change people’s thoughts; they can inspire hearers to act differently. Ultimately, however, beyond these pragmatic effects, sermons speak to the depth of the soul. This requires a second step in recovering the language of the soul in homiletics: a reassessment of the pastoral function of preaching. How can sermons become instruments in caring for the soul?

4. Caring for Souls in Preaching

Preaching serves many functions. A classic typology is given by Grady Davis with his functional forms of preaching: proclamation, teaching, and exhortation. Davis grounds these functional forms in the New Testament verbs (

Davis 1958). With the verb

parakalein Davis puts forward that the prophetic and the pastoral go together. Trey Clark argues that the prophetic should not be played against the pastoral function of preaching. He proposes a “more integral relationship between the preacher as prophet and pastor” (

Clark 2022). Clark takes his inspiration for such integration in the ministry of Baptist pastor and social justice activist Howard Thurman (1899–1981), who “stressed the personal more than the systemic, the soul more than structures”. Thurman had to speak prophetically to the racialized violence in his times; Clark summarizes Thurman’s way of integrating the prophetic and the pastoral as follows: “For him, a focus on the pastoral provides a humanizing lens for doing the work of the prophet, and a focus on the prophetic provides a holistic lens for doing the work of the pastor”.

The pastoral function of preaching may build upon Davis’s analysis of the Greek term parakalein in relation to preaching, but it has been put forward in recent homiletics, foremost by pastoral theologians. Let me give three examples.

In his

Care-full Preaching (

Ramsey 2000), Lee Ramsey starts with the observation that the history of preaching is full of examples in which preachers spoke as pastors. Among others, he mentions Origen’s talking about a “believer’s steadfastness in faith”, Augustine’s pastoral intent of love, and Gregory the Great’s speaking healing words “on the wounds of the sin-sick soul” (

Ramsey 2000, pp. 10–11). Therapeutic preaching is more than the care for the psyche of the listener; it concerns the community. In other words, pastoral preaching and ecclesiology go together. Preaching, Ramsey argues, aims to shape pastoral or caring communities that foster qualities like mutuality, hospitality, and care for the world (

Ramsey 2000, p. 58). The heart of his proposal for pastoral preaching is the dynamic between the community of faith and the individual human being. That is why theological anthropology and ecclesiology are the two dimensions in his homiletical proposal, the former leading to a renewed reflection on the human being in the sermon (

Ramsey 2000, pp. 80–81).

Neil Pembroke acknowledges the critical notion of therapy in relation to preaching. His proposal is “that therapeutic preaching is rightly construed as pointing listeners to the divine

therapei”, and he continues: “God’s therapy is God’s healing love expressed through compassion, acceptance, help, and forgiveness, but also through confrontation and challenge” (

Pembroke 2013, p. 2). In his proposal, he stresses the theocentricity of preaching: it is God who cares for us, who challenges us, and who comforts, helps, and forgives. Pembroke takes a nuanced approach towards the tension between individual and community in relation to pastoral preaching. He acknowledges that therapy is concerned with individuals. Therefore, he does not push the therapeutic too far. Not all preaching should be therapeutic, but there is a need for a therapeutic model, which is one model of preaching among others. Important for Pembroke’s proposal is his insistence on “locating God in Christ in the center of sermons”. Combining the therapeutic and the theocentric creates a model of preaching that puts the divine-human relationship and the healing work of God in the centre of homiletical reflection.

Thirdly, in multiple publications, Christian Möller presented his views on the relationship between pastoral care and preaching (

Möller 1990, pp. 86–90). In a section on features of pastoral preaching he presents four different aspects: 1. the sermon sees humans as individuals and the hearer should be able to feel addressed personally by the Word of God; 2. the sermon builds up the community of faith because the relationship between God and these people started already in baptism; 3. the sermon attunes to the fearful conscience of hearers because humans do not just have a conscience, they

are a conscience before God; 4. the sermon invites to the celebration at the Table of the Lord, at which the congregation shares the cup of comfort. Möller’s views are influenced by his Lutheran context. In a different text, he grounds these basic ideas in some texts by Søren Kierkegaard. Kierkegaard inspires preachers to offer pastoral preaching in his understandings of humans

in the depth of their souls (

Möller 2012, pp. 38–42).

In their own ways, these three approaches to preaching as soul-care have implications for theological method in general and for homiletics in particular.

Methodologically, these approaches continue to highlight the importance of the community for theology. These homiletical reflections on preaching as soul-care demonstrate that the soul cannot be addressed in sermons without taking into account the community of faith. Despite the fact that current approaches to listeners have been focussing upon individual processes of meaning-making during the preaching event, the sermon is uttered in the midst of a group of people, whether it be a congregation that meets weekly for Sunday worship or a spontaneously gathered group of people, for instance for a special occasion (a funeral, a wedding) or in a particular setting (soldiers coming together in a ritual setting organized by a chaplain). The pastoral function of preaching may address souls, but these souls are addressed in the community. Processes of individual meaning-making indeed demonstrate that everyone has heard a different sermon. Yet as a speech that addresses a group of people, the sermon

also contributes to communal meanings. In the listening event, the soul is not alone but is surrounded by souls. Listeners report that while listening to the sermon those who are dear to them, such as fellow believers in the congregation, are in their hearts. They think about other listeners, hoping they will be touched by the sermon (

Pleizier 2018). Such listening experiences demonstrate how the preaching event contributes to the interconnectedness of souls.

Homiletically, the pastoral function of preaching builds upon this communal aspect of the preaching event but specifically addresses the issue of theological anthropology. Do we conceive of the persons that make up the audience in the preaching event as Selves or as Souls? To engage in a conversation on theological anthropology, at least two traditions in homiletics could act as conversation partners. First, Pembroke reflects upon the therapeutic paradigm in relation to preaching. The voice of therapy and counselling addresses Selves that need healing and care. His proposal also shows that the discourse of therapy becomes integrated with theology. His theocentric approach, or

divine therapeia, exemplifies this. In other words, when the Self—as concept in therapeutic literature—enters the sermon, it becomes the Self in relation to God. This invites a second voice into the conversation: the Puritan, Methodist, or Pietist traditions of preaching.

4 The critique against the Pietist tradition could be raised that its focus is too restricted to the eternal destination of humans, that it relies too much on a radical eschatology that denies the current earthly existence, and that it communicates a type of soteriology and spirituality that is disembodied. However, on the positive side of the ledger, these traditions remind the preacher that in the reception of the sermon, nothing less than the divine-human relationship is at stake. The Self needs a soul. The proclamation of the gospel expresses a longing for peace, it projects a renewed world in which justice reigns, but it also unites

5 God and human beings.

In sum, the pastoral function of preaching is not just the application of aspects of the field of pastoral care and counselling to the practice of preaching, but it points to preaching that rejuvenates the soul. Hence, the third step in recovering the language of the soul in homiletics concerns the preparation and performance of sermons. What are the homiletical conditions for preaching that breathe life into the soul?

5. A Homiletical Agenda for a Retrieval of the Soul in Preaching

If care for the soul remains an important function of preaching, how should we envision the conditions for retrieval of the notion of the soul in homiletics? The proposal to consider the soul in preaching takes its lead from the idea that preaching is a life-bringing, life-sustaining, and life-affirming event. Here lies a fundamental theological figure that calls for a homiletical reassessment of the soul.

An act of preaching becomes soulful if the sermon is conceived of as one turn in an ongoing conversation. The idea of the ‘turn of a conversation’ is derived from the critical analysis of interhuman communication in the work of the communication scholar John Durham Peters (

Peters 2001). Peters reflects upon the impossibility of human communication: it is an ‘angelic dream’ even to assume that communication is about aligning people’s thoughts, affections, and behaviour. Communication, he argues, is more like taking turns. Every communicative turn is completed in the hope that the next turn will follow up and bring us closer as humans. This is a realistic and hopeful perspective for preaching. The sermon has a life, not only or chiefly as this single sermon, but as a turn in an ongoing communicative practice. The soul in preaching is therefore a very vulnerable soul, as souls always are. The voice in the sermon is a voice of life and a lively voice (

viva vox) in which the Gospel can be heard. For this, I suggest three items for the homiletical agenda. They are phrased as proposals to review the conditions for good preaching.

First, I propose a hermeneutical condition. The life-giving force of the Gospel is hidden in the biblical texts. The biblical texts are sacred texts or Holy Scripture due to a process of canonization: the worldwide Christian community has recognized a certain set of texts to be the divinely inspired carriers of the good news. The task of the preacher is to recognize this God-breathed life in the ancient texts. This requires a complex whole of competencies: linguistic, exegetical, reflective, and spiritual. It is not so much a choice of an exegetical method rather than an attitude to listen to the biblical texts to discover the soul, the breath of life that God has given to the world to be renewed, to rekindle hope, and to inhale the atmosphere of God’s kingdom.

Second, I propose a rhetorical condition. To hear the living voice of the Gospel and to be renewed in faith and love requires reflection on rhetoric. A retrieval of the place of the soul can contribute to this conversation. This calls for a retrieval of aspects from classic texts on preaching and rhetoric, for instance in the work of Alexandre Vinet as quoted above, who speaks about preaching that “moves the soul”. The sermon is not just one genre of speech among many others. Preaching is the living voice (the viva vox) of the Gospel, which projects an alternative rhetoric. There is an ongoing conversation in homiletics on the role of rhetorical theories in the act of preaching and what this alternative rhetoric might look like. What does it mean to preach the good news in such a way that new life can be experienced, that the souls of listeners are touched, restored, and filled with hope of God’s kingdom, faith in the promises of God, and love for God and the world?

Third, I propose a theological condition: preaching that addresses the soul in its relation to the God of life. For sermons to communicate life, theologies are needed that not only recognize the life-giving force of the gospel in the Scriptures (the hermeneutical condition) but also find language and structures of language to communicate the living voice of the Gospel (the rhetorical condition) and to express the soul of the listeners. Preachers must address that which is deep down in the existence of the listeners, that which defines the core of what it is to be human and to care for being human in a world that is suffering, especially when so much suffering is caused by humans. The many lived religions and lived faiths point to our souls, and it is an important task for preachers to hear these souls in order to care for them. For this, a rich theological understanding of the soul is needed. This essay is only a first attempt. But if our souls refer to who we are in relation to the God who breathed life into our very beings, then preaching holds a promise: it embodies the life-giving Word of this God.