1. Introduction

The significance of Gan Xiao’er’s religious films is located in postsocialist Chinese cinema in general and Chinese independent cinema in particular. Gan made three feature films with Christianity as the subject matter from 2003 to 2012, as part of his ‘Seventh Seal’ projects aiming to produce seven features about Christianity in China (

Qi 2013, p. 63), namely,

The Only Sons 山清水秀 (

Gan 2003),

Raised from Dust 舉自塵土 (

Gan 2007), and

Waiting for God (

Gan 2012). Christianity is an underexplored subject and an under-represented social reality in postsocialist Chinese cinema, including both mainstream and independent cinemas. As a renowned independent filmmaker, Cui Zi’en 崔子恩 is a pioneer in representing Catholicism entangled with queer experience in China, for example, in his

Mi Sa 彌撒 (

Mass) and

Jiu Yue 舊約 (

The Old Testament) in 2001. Gan is regarded as another forerunner in Chinese independent cinema for introducing Christianity as the main theme (

Ai 2007). Other examples in independent cinema include Yang Jin 楊瑾’s

Er Dong 二冬 (2008) and Wang Liren 王笠人’s

Tattoo 刺青 (2009) (

Reynaud 2003;

M. Li 2012, pp. 14, 56). A few feature-length documentaries about Christianity in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) are found, such as Hu Jie 胡杰’s

Songs from Maidichong 麥地沖的歌聲 (2014) and Lin Xin 林鑫’s

Preacher (2014). Gan has not made another religious feature film after

Waiting for God, which seems to be related to the tightened measures for regulating both religions and filmmaking during Xi Jinping’s presidency (since 2013), with the implementation of the revised Regulations on Religious Affairs (2018) and the Film Industry Promotion Law (2017). The latter policy bespeaks the decline of independent cinema in mainland China, with greater restrictions on filmmaking, screening, and participation in overseas film festivals without government approval (

Colville 2023;

The Pew Research Center 2023). In retrospect, the narrowing chance of making films about Christianity like Gan’s confirms that his features are scarce cases of this sort in the history of postsocialist Chinese cinema. Moreover, these are quality films in terms of visual craft and the critical depth of narrative.

What is Gan’s specific contribution to postsocialist Chinese cinema with his religious features? What approaches has Gan adopted to interpret Christianity in China? Clearly, Gan’s contribution lies in his depiction of the under-represented religious group through cinematic images, but his significance goes beyond that. This paper argues that Gan Xiao’er’s feature films provide a rare religious critique in postsocialist Chinese cinema in two senses: first, they provide a social and cultural critique of dehumanising practices and materialistic values, using Christianity as an alternative model or perspective. Second, Gan’s feature films are critical of the religious institution (the Church) from within, emphasising its restrictive, rigid nature. Instead, the pursuit of a liberating spiritual journey is embodied by taciturn and introspective female characters. This paper also argues that Gan’s three features chronically constitute an ‘inward journey’ inquiring about the interplay between the world and religiosity. In the first film, The Only Sons (TOS hereafter), the protagonist has a brief encounter with Christianity approaching his death after he has experienced a series of plights and obtains a final redemptive relief. The second film, Raised from Dust (RFD hereafter), not only represents the communal life of Christians in a local church in a documentary style but also shows how the heroine works through everyday hardship from a Christian perspective. The third film, Waiting for God (WFG hereafter), focuses on the introspection of the heroine, who is a local church leader, problematising the religious institution and its ‘official’ discourse from the insider’s angle. Another trajectory of Gan’s creativity in these films is noted as the gendered feature in that the first film is a male-centred narrative, while the second and third films are female-centred narratives questioning the male-led environment. The main female characters are ‘reserved mothers’ who play more essential roles in later films, but they are not simply submissive to men. Rather, in dialogue with the ‘Holy Family’ trope, their reserve signifies spiritual strength and resistance to the patriarchal structure.

Gan’s early biography can help us understand why and how he made these religious films. He was born in Henan Province in 1970 and obtained a master’s degree from Beijing Film Academy in 1998 (

Zhong and Zhou 2007). He was inspired by his Christian parents and converted to Protestantism in 1997. He recalled that, in his father’s final days, his mother often prayed for her husband suffering from cancer, and the couple sang hymns together. Gan was moved by their peaceful and tender attitude towards hardship (

Yaoyao Zhang 2008). The images of the dying father and the resilient mother appear in Gan’s first two films. In 2000, Gan established ‘The Seventh Seal Film Workshop’, aiming to make seven feature films about Christianity in China, especially to illustrate the inner life or spirituality of Chinese people from the Christian perspective (

M. Li 2012, p. 99). For Gan, spirituality refers to God–human and interpersonal relationships full of ambiguity and tension (

Shi 2009). Although Gan admired Ingmar Bergman, the Swedish filmmaker, his ‘Seventh Seal’ project does not refer to Bergman’s film

The Seventh Seal (1957) but to the Bible’s Book of Revelation about God’s judgement. In this regard, filmmaking for Gan is a process of spiritual judgement with hope (

Qi 2013, p. 63). However, he tends to suspend moral judgement on his film characters struggling with ethical challenges, as he remarked, ‘Judgement is God’s business!’ (

G. He 2007).

Gan’s religious features were mainly shown in film festivals and private screenings in universities and churches (

Bing 2009;

Yaoyao Zhang 2008). For example,

TOS and

RFD were shown at the Pusan International Film Festival and the Rotterdam International Film Festival. These films gained international recognition:

TOS won the Dragons and Tigers Award (Jury Special Mention) at the Vancouver International Film Festival in 2003, and

RFD won the ‘Most Humane Care Award’ at the 2008 Chinese New Film Forum.

WFG was shown in the Chinese Young Generation Film Forum, the Chinese Independent Film Festival in 2012, and the ‘New Echo’ exhibition (Season 1) in 2013 (

South China Normal University 2024). Gan’s third feature may have reached less foreign audiences than the two earlier films. As elaborated in later paragraphs,

WFG has further narrowed Gan’s already niche audience due to his dedication to an ‘independent’ attitude towards filmmaking.

Identifying Gan’s works as ‘independent films’ requires briefly introducing the category. Emerging in the early 1990s, ‘independent cinema’ denoted filmmaking outside the state-studio system and later modes of distribution and exhibition outside the mainstream commercial circuit as the film industry went through marketisation and privatisation. It also implies greater creative autonomy by avoiding bureaucratic procedures (

Pickowicz and Zhang 2006, p. ix;

Pickowicz 2012, p. 328). For Gan, ‘independence’ simply refers to the mode of low-budget production different from the commercial operation in mainstream film studios, while the absence of the state’s authorisation, marked by the ‘dragon seal’, is not an essential criterion (

Gan 2022, p. 212). In addition to self-financing and personal sponsorship, non-commercial funding for independent filmmakers often comes from foreign film festivals. For example,

RFD was supported by the Hubert Bals Fund of the International Film Festival Rotterdam and the Post-Production Fund of the Busan International Film Festival (

Gan 2022, pp. 212–13;

Yaxuan Zhang 2007, p. 62). Technological advances facilitated budget filmmaking, and Gan belongs to the wave of independent directors emerging at the turn of the new millennium when new digital technologies lowered the cost of film production. Handy digital cameras also enhanced filmmakers’ mobility to make films in distant rural areas more easily (

Veg 2010, pp. 5–6).

These conditions of independent production led to specific subject matters and aesthetic styles preferred by independent directors of that period. They tended to depict everyday life stories of ordinary people, the grassroots, and marginalised communities struggling amidst economic development and social changes often under-represented in mainstream cinema and the mass media (

Veg 2010, pp. 5–6;

Z. Zhang 2007, p. 3). Depictions of these people’s experiences in independent films appear distinctive aesthetically from those in commercial films and state propaganda. Jason McGrath labels the aesthetic style presented by many independent films as ‘postsocialist critical realism’ that could critically reveal the social costs of accelerated economic development during the Reform period (

McGrath 2008, pp. 132, 136). Some directors of this kind favoured on-location shooting in public areas, hand-held mobility, and raw editing style for a sensation of documentary-like, authentic representation of the lower class’s living conditions. Other independent filmmakers, such as Gan, prefer carefully crafted cinematography with long takes, wide angles, and slow-paced editing (

McGrath 2008, pp. 139, 148, 160). Chinese Christians, particularly rural Protestants, belong to those marginalised groups under-represented in contemporary Chinese cinema, indicating Gan’s independent nature. Moreover, Gan is not only independent of the mainstream film industry but also the Church. His critical attitude towards the religious institution is unwelcome to some church leaders and believers, who have refused to help upon his requests for further production and screenings (

Qi 2013, p. 64;

Chen and Yu 2012). Similar instances have been captured by the existing scholarship of Gan.

Most of the literature about Gan’s films are interviews and film reviews in Chinese, while few academic publications (in English) are found. Jinghan Xu’s book chapter (

Xu 2021) provides an overview of representations of Christianity and themes related to Christian values in contemporary Chinese films, briefly perusing Gan’s features. Chi-keung Yam’s book chapter (

Yam 2013) compares Gan’s

Raised from Dust with Feng Xiaogang’s

Assembly (2007) and

Aftershock (2010) for different representations of Chinese people’s attitudes to death in independent films and mainstream cinema. While Gan shows an independent Christian filmmaker’s notion of death as acceptable relief from living plights, Feng reveals a common and sentimental rejection of death (

Yam 2013, pp. 99–100). Angela Zito’s book chapter (

Zito 2015) focuses on

RFD and Gan’s documentary

Church Cinema (

Gan 2008), which records the audience reception when Gan showed

RFD to rural churchgoers in the Henan Province, including those who participated in

RFD. Zito highlights the self-reflexive and participatory features of these two films, indicating the tension between Gan’s individual artistic pursuit of religiosity and his Christian fellows’ expectation of an evangelical film promoting Christianity (

Zito 2015, pp. 252–54). They show conflicting aesthetic preferences in that Gan has presented an implicit, slow-paced, and ambiguous narrative far from the enthusiastic drama that could affectively convert more people to Christianity (

Zito 2015, pp. 238, 245). Gan is also distinct from his Christian fellows, including (and especially) congregants in his home village who participated in

RFD, regarding the expected outcomes and aesthetics. Such conflicting expectations appear to stem from Gan’s experience as an urbanised, well-educated filmmaker with an elitist taste in art, in contrast to that of common rural churchgoers (

Yam 2013, p. 99;

Zito 2015, p. 238). Generally, although Gan intended to show his films to rural audiences, with the tour screenings of

RFD in several Henan villages, he has received critical acclaim mainly from urban areas (

Bing 2009).

In a retrospective piece, Gan recalls this frustrating experience sarcastically, using terms associated with socialist politics; for example, he calls the post-screening discussion with rural congregants a ‘struggle session’ (

pidouhui) against him and that they expected

RFD to be a ‘main-melody film’ that functions like a political campaign (

Gan 2022, pp. 202–3). This instance is crucial in Gan’s positioning as an ‘independent filmmaker’ in that he seeks to distance himself from institutional and populist politics inside and outside the Church. Yam remarks that

RFD’s depiction of the communal side of Christianity may be a remedy for the individualistic view of Christian faith in the West that is problematic (

Yam 2013, p. 101). However, Gan has ironically turned to a further solitary quest of faith through filmmaking. His third feature,

Waiting for God, can be seen as a response to the Christian community’s lack of endorsement for his works. Still, he was encouraged by a fellow believer who, after watching

RFD twice, felt she ‘suddenly understood’ what this film was about. She comforted him by saying that ‘Even if your film has only one audience, God still remembers your labours’ (

Gan 2022, pp. 210–11). For Gan, independent cinema not only connotes making films for individual expression but also means autonomy in selecting one’s audience, even though only a few kindred spirits exist. Hence, he regards

WFG as a ‘lonelier and more niche’ film that depicts the personal spiritual journey of a Christian straying from institutional doctrines (ibid., pp. 211–12).

This article fills the lack of a systemic exploration of all three features of Gan, especially the third film, WFG, while RFD seems to have drawn the most attention. It investigates Gan’s religious–cultural critique through a close analysis of the film texts as case studies, including their visual style, and through a contextual dialogue with the social transformation of China during the Reform period. As will be elaborated in later sections, Gan’s films are characterised by ambiguities that problematise the borders between innocence and sin, as well as the ‘holy’ and the ‘unholy’. Cultural theories and the literature are employed because this article is not a theological discussion but a case of cultural and film studies probing the intersection of Christianity and independent cinema in China.

In particular, Julia Kristeva provides insights for understanding the spiritual quest for the hope of redemption in Gan’s films and analysing how these female characters suggest an internal critique of the Church, focusing on the holy/unholy distinction.

Kristeva (

1982) uses the concept of ‘abjection’ to describe the process of repulsing or excluding what can threaten the boundary between the self and the other, namely, the ‘abject’. The abject blurs or challenges the limits or borders that sustain identity and order. Examples include filthy or horrible matters, such as body fluids and an animal’s corpse, but they are not limited to these unclean objects. The mother’s body is also ‘abjected’, to be separated by the emerging individual subject, a speaking subject, who finds an identity in the symbolic order: ‘It is thus not lack of cleanliness or health that causes abjection but what disturbs identity, system, order. What does not respect borders, positions, rules. The in-between, the ambiguous, the composite’ (

Kristeva 1982, p. 4). In this way, abjection refers to recurring instances or an ongoing process of excluding or repelling what can trouble the border of the self or social identity. Hence, it also has significant sociological and political implications regarding social identity dependent on dealing with the social others (

Kristeva 1982, pp. 8–9; see also

Zakin and Leeb 2023). As

WFG shows, Christians also sustain their communal identity by repelling religious others.

Furthermore, Kristeva calls the maternal space where the speaking subject is not yet formed and when the mother–infant tie is not yet severed the semiotic

chora (borrowed from Plato, meaning receptacle). While the subject in the symbolic order is one of law and language, the semiotic

chora is a space of drive and rhythm: ‘a non-expressive totality formed by the drives and their stases in a motility that is as full of movement as it is regulated’, and which is ‘analogous only to vocal or kinetic rhythm’ (

Kristeva 1986, pp. 93–94; see also

Zakin and Leeb 2023). The

chora is the maternal space repressed by the (patriotic) symbolic order, so it helps us to understand, in Gan’s films, some characters’ marginal positions regarding religious and other social institutions (

Miller 2016, p. 162).

Kristeva’s conception of passionate love is also helpful in analysing Gan’s films. In

Tales of Love, Kristeva conceptualises God’s love as ‘definitely a disinterested gift’ through Christ’s Passion (

Kristeva 1987, p. 139). Such a gift ‘allows a Meaning, always already there, anterior and coming from above, to manifest itself to the members of the community that share it’ (p. 143). While sacrifice in other contexts refers to a social contract between humans and God established by the obliteration of the sacrificial substance metaphorically, God’s love primarily comes from God as a gift for humans to analogically identify with God and become ‘adopted’ (pp. 142–43). Kristeva’s interpretation helps us understand how Gan’s

TOS provides a critique of a dehumanising society that reduces human values only to an exploitable exchange value. Another useful concept from

Kristeva (

2005) is maternal passion, which is the prototype of other human love relations. In this sense, motherhood is a ‘learning process in how to relate to the other’, and the maternal passion ‘allows the affect to turn into tenderness, caretaking and benevolence’. The passionate mother has to let go of her child so that the latter can become an autonomous subject, so maternal passion also involves a process of depassioning, leading to liberation and creativity (

Kristeva 2005). In the analysis of

WFG in

Section 4, it is proposed that such maternal passion can critically respond to patriarchal restrictions in religious institutions.

2. (In)human Conditions in The Only Sons

In The Only Sons, Shui, a farmer living in the Guangdong Province, is a breadwinner struggling with a series of distressing conditions. His wife, Qiuyue, is expecting a baby. His younger sister may not be promoted to high school because the tuition fee is unaffordable. His younger brother Chung is a convicted criminal sentenced to death, and the final option to save him is to bribe the judge. Desperate to raise funds, Shui tries every means to sustain his family, but those only pull him deeper into a downward spiral. He sells his blood but gets an HIV infection. His sister drops out of school to work in town, becoming disconnected from her family. He ‘rents out’ Qiuyue as a surrogate mother for another family. He even sells his newborn son to a ‘wealthy family’ that actually is a group of human traffickers. Finally, it seems that Shui has lost everything: Chung has been executed, Qiuyue has killed herself, and Shui is dying of AIDS. His baby boy, though saved by the police, can hardly survive because all neighbours avoid this household. Only an itinerant preacher, who has had several brief encounters with Shui, visits and prays for him and adopts his son so that Shui can rest in peace.

In this film, Gan suggests how Christian faith can bring hope to the impoverished at the end of their rope. The protagonist Shui’s plight is situated in the postsocialist condition, where people like him are commodified and dehumanised. The term ‘postsocialist’ refers to a time of rapid transformation when ordinary people have to endure what comes to them without truly understanding the causes and mechanisms (

Z. Zhang 2007, pp. 5–6). On a global scale, McGrath uses ‘postsocialist modernity’ to call the post Cold War period when global capitalism reigns as the only mode of modernity and where marketisation and consumerism become the main drives of society and culture (

McGrath 2008, pp. 9, 14). In former socialist states that remain authoritarian, such as the PRC, the postsocialist condition often results in income inequality, corruption, and other social ills. Shocking economic growth driven by marketisation has been witnessed, often at the expense of the lower class’s well-being and rights (

McGrath 2008, pp. 12, 209;

Z. Zhang 2007, p. 6). Xudong Zhang defines Chinese postsocialism as ‘an extremely uneven and heterogeneous socioeconomic, political, and daily reality’ that was emergent in the 1990s. This condition results from the paradoxical overlap and mutual determination of the socialist nation-state and global capitalism (

X. Zhang 2008, pp. 13, 16, 17). The postsocialist condition of China is marked by the rise of the consumer mass, as well as contradictions and heterogeneity of practices and values, suggesting the potential of resistance that calls for social justice, especially when the state takes an active role in national marketisation and global capitalism (ibid., pp. 10, 11, 13, 174). Some indicate a moral crisis or ‘spiritual void’ after the Cultural Revolution destroyed traditional morality and folk religions, and then socialist ideology receded in the Reform era when the market logic took hold, leading to moral corruption (

H. He 2015, pp. 107, 120;

McGrath 2008, pp. 20–21). This ‘spiritual void’ phenomenon can, at least, partially explain the surge of Christianity during the Reform era (

Leung 1999, pp. 223–24).

In

TOS, Shui (played by Gan) is sucked into the vortex of misfortunes and sin, meaning that he is not simply an innocent victim since what he does to save his brother may be found morally dubious by many viewers. Bribing the judge and selling his son, Shui is forced to exploit his family and himself by the circumstances, highlighting a net of social ills in the postsocialist condition. In particular, human life is capitalised and commodified as the market logic dominates. Almost all means Shui has traded off for money are parts of human life. He contracts AIDS by selling blood, insinuating the 1990s AIDS epidemic in Gan’s home province, Henan. This epidemic has been a taboo the government obscures, hence rarely represented in Chinese mainstream cinema (

M. Li 2012, p. 100).

TOS’s depiction of blood selling and AIDS is emblematic of the issues of the dehumanisation and commodification of life in postsocialist China.

Shui could represent those people sacrificed for the economic growth resulting from state-driven marketisation. Their hardship is the cost behind what Deng Xiaoping (China’s leader who initiated the Reform) said ‘to be rich is glorious’ and ‘let some people get rich first’, prioritising money-making over social justice and humanity (

Chi 2012;

Ramzy 2012;

Rauhala 2008). On the other hand, we can also regard people like Shui as ‘bare lives’ who ‘may be killed but not sacrificed’, according to

Giorgio Agamben (

1998, p. 83), if not ‘mere flesh’, connoting how human is devaluated and capitalised. Jean Camarofi develops the concept of ‘bare life’ and focuses on the condition of AIDS patients who are excluded from ‘meaningful social existence’, extending Agamben’s idea to the ‘biocaptial’, meaning the epistemological and institutional forces that control and subsume the matter and life and death under the market logic (

Comarofi 2007, pp. 207, 213). The unfortunate events happening to Shui exemplify how these people are objectified for profits and deprived of their social values. At the film’s ending, when Shui shows obvious symptoms of AIDS, all neighbours avoid him, leaving him alone with his rescued baby on his deathbed. (Qiuyue has killed herself.) Emblematic of many discriminated AIDS patients, he is ‘a scarcely human being condemned […] to callous exclusion, to death without meaning or sacrificial value; a being left untreated in an era of pharmacological salvation’ (

Comarofi 2007, p. 207).

Gan depicts Shui’s dehumanisation with an analogy to a pig. Shui’s pig disappears after he has decided to sell his to-be-born baby. The director jumps to the destination of the pig with a close-up of Shui and the pig facing each other in a symmetric composition, where the pig’s head has been cut off and put on the butcher’s chopping table, with several pieces of pork hanging above (

Figure 1). This image visualises an analogy between the man and the pig. The disassembled pig harbingers Shui’s life and family will be dismantled. The pig was sold by Shui’s sister, who took the money with her friend and ran away to town. The butcher is also a blood dealer who operates a secret blood station where Shui sells blood and contracts HIV infection. The dismantled pig symbolises how human life is devaluated as flesh for sale for impoverished people in China who can hardly share any fruits of the economic boom. Shui’s family is symbolically disassembled like an inventory of the human body: Shui sells his blood; his wife rents out her womb; his sister becomes a prostitute; and his newborn son is sold. Still, Shui cannot save his condemned brother, Chung, whose execution is communicated appallingly. The officer who comes to announce Chung’s death also collects the ‘bullet fee’ from Shui. A state-owned hospital representative who accompanies the officer offers to purchase Chung’s organs: CNY 2000 (RMB) for his corneas or heart and CNY 3000 for his kidneys or spinal cord. Both visitors representing the state speak apathetically about life and bureaucratically about money. They are like the butcher, while Shui and his family are like the pig on the chopping block.

Shui and his family are more bare lives than sacrifices in that they are exploited of every single drop of blood and piece of flesh. The moribund protagonist is but a residue of others’ capitalisation. Comarofi indicates that the state plays a vital role in turning a human into ‘bare life’, which shows ‘how modern government stages itself by dealing directly in the power over life’, that is, ‘to strip human existence of civic rights and social value’ (

Comarofi 2007, p. 208). Shui receives no protection of his rights from the state, such as social welfare and public health support, when he suffers from destitution and AIDS. Representatives of the state in

TOS only come to Shui to extract more from this impoverished family. In addition to the two ‘death messengers’ of Chung mentioned above, there are two officials from the Family Planning Commission who charge Shui and Qiuyue for a permit to give birth to a baby. The state, represented by affectless bureaucrats, not only has sovereignty over its subjects’ life and death but also makes profits out of them systemically. Camarofi moves from ‘bare life’ to ‘biocapital’ as ‘the knowledge, patents, and systems of exchange and command that make the difference between life and death’ (

Comarofi 2007, p. 213). ‘Bare life’ is insufficient for understanding the sovereign power in the age of globalisation since the force of international capital also determines the meaning of human life, undermining the state’s monopolistic power (

Comarofi 2007, pp. 207–8, 210). However,

TOS suggests that the state’s role is still significant in the time of globalisation.

In postsocialist China, the state has taken a vital role in the capitalisation of life; as Shui’s story shows, all instances of life and death become profitable. In addition, the underground economy of blood selling and human trafficking also constitutes the biocapital system. There are reports that the Chinese government has harvested organs from executed prisoners, although the government claimed that the practice would stop in 2015 and only source organs from voluntary donors (

Carney 2011, p. 82;

Hurley 2018). It is also reported that a state-sponsored organisation provided a price list of organs, such as kidney, liver, and cornea, for organ transplantation in the local and overseas markets (

Carney 2011, pp. 87–88). Another report shows that the Henan Provincial Department of Health leader started a biotech company in the 1990s to collect and sell blood. Prioritising profits above public health, the blood collectors reused needles among blood donors, leading to an HIV epidemic in Henan, Gan’s home province (

Carney 2011, p. 192). These reports provide a literally bloody reference in reality to the plot of

TOS, which depicts how the postsocialist Chinese state has been an active part of the biocapital network.

A similar illustration of dehumanisation is also found in Gan’s second feature,

Raised from Dust. The heroine’s husband, Xiao-Lin, is a former miner dying of pneumoconiosis caused by his work. He loses the ability to work and becomes bedridden, but he does not get any compensation from his employer or support from the state. Medical treatment is unaffordable for his family, so his bed is put in the corridor during the winter. In the postsocialist condition, Xiao-Lin’s value is only recognised when he is healthy enough to contribute to the economic development that requires the vast utilisation of energy and raw materials. However, he is expendable once his value as labour is exhausted, reduced to the residue in the biocapital system and left to die. There are other Chinese independent films that depict the dehumanisation of postsocialist subjects, such as Li Yang’s

Blind Shaft (2003) and Peng Tao’s

Little Moth (2007). In

Blind Shaft, two miners conspire to murder other workers and extort compensation from the employers. In

Little Moth, a sick girl is sold to human traffickers who force her to beg in the street (

M. Li 2012, p. 111).

What sets Gan apart from other independent filmmakers is the intervention of Christian faith in the protagonists’ destitution. He interprets the postsocialist condition through a religious perspective, particularly by responding to people’s suffering within a Christian framework and suggesting the possibility of redemption. Shui is not only burdened by financial but also moral debts, in that he feels guilty about trading off his wife and son to save Chung and about not nurturing Chung well after their parents’ deaths. His human dignity also needs to be redeemed from dehumanised commodification. This experience constitutes his spiritual needs, drawing him to the itinerant preacher’s message about God’s mercy. In the village’s public area, the preacher talks about Abraham’s offering of his only son Isaac (Genesis 22) and how God sacrificed his only son Jesus for human redemption, echoing the film’s title, which also signifies how Shui sacrifices his baby to save Chung. While the ‘bare life’ is not sacrificed as anything meaningful, here, sacrifice as a sign of love in the Christian faith formulates a response to the dehumanising condition. When Shui is about to die as a meaningless object, the redemptive twist arrives when the preacher visits, prays for Shui, and adopts his son.

Julia Kristeva, in

Tales of Love, defines sacrifice as the ‘obliteration of a concrete substance so that an abstract meaning might come to the sacrificers’, the metaphorical offering that creates meaning for the offer and the recipient Other or the God (

Kristeva 1987, pp. 142–43). The concept of ‘God’s love’ is demonstrated through Jesus’ death, which serves not only as a sacrifice but also as an analogy, allowing humans to be symbolically identified with God as His beloved children (

Kristeva 1987, pp. 143–44). This ‘beloved child’ identity gives meaning and hope to people like Shui. In the preacher’s final prayer, Shui realises that he is loved and can be forgiven, and Chung, who claimed to believe in the Heavenly Father, can be liberated through faith in God’s love because Jesus has been sacrificed for all their sins. Hence, they are no longer meaningless ‘bare lives’ or the residue of biocapital. Kristeva explains that God’s love (

agape) is a matter of faith (

pistis). God is the source of such love as a passionate gift, as revealed by Jesus’s suffering death that reconnects God and humanity: ‘The gift love through sacrifice is the reversal of sin’ (

Kristeva 1987, pp. 140–41). Shui can receive God’s love as a gift without exchanging anything, not even a sacrifice, since God has prepared his only son as the sacrifice: ‘The Christly passion […] is thus only evidence of love and not a sacrifice stemming out of the law of social contract’ (

Kristeva 1987, p. 142). This logic challenges the materialistic exchange logic in the postsocialist condition that reduces human beings to biocaptial. Only through believing in God’s love can Shui be rehumanised as the beloved son.

Those who believe in God’s love share an experience analogous to Christ’s death and resurrection, constituting a nominal identification with God as adopted children (

Kristeva 1987, pp. 143–44). This analogous adoption to sonship brings comfort to Shui, who has lost his parents and betrayed his son, both of whom need such adoption of love. The preacher embodies God’s adoptive love through action: when he prays for Shui, he acts like a caring father, comforting his ill child and adopting Shui’s son (otherwise, the baby will be an orphan). Shui and his son are no longer ‘mere flesh’ to be traded off but beloved children of God, redeeming his spiritual needs of human dignity and social values.

3. (Mis)representations of Christianity in Raised from Dust

In Raised from Dust, Xiao-Li is a churchgoer in a Henan village. Her husband, Xiao-Lin, is an ex-miner now bedridden due to silicosis, but they cannot pay the medical fees on time. Her daughter, Shengyue, faces school suspension because of tuition arrears. Xiao-Li barely gains a living as a tricycle deliverer. Despite these difficulties, Xiao-Li stays reserved and attends the church band practice as usual. Although a group of Xiao-Lin’s friends claim they would support her family, these are just empty words, while the only financial support comes from Xiao-Li’s church fellows for her husband’s medical bills. However, Xiao-Li decides to spend that money on Shengyue’s tuition fees and terminates Xiao-Lin’s treatment, letting him die in their sweetest memory.

Clearly, there are two objectives Gan wanted to achieve by making

RFD: to represent everyday rural Christian life in his hometown and to demonstrate how a Christian family faces hardship in a different way from that in

The Only Sons. Eventually, Gan made

RFD into a docu-drama that embodies an inherent aesthetic tension, as has been mentioned in the Introduction: many local Christians did not appreciate Gan’s representations of their community, while Gan insists on his individual spiritual quest through artistic means (

Gan 2022, pp. 210–11). This section will show how

RFD, adopting the aesthetics of ‘postsocialist critical realism’ (

McGrath 2008), is more than an ethnographic representation of rural Christianity in that it has presented a socio-cultural critique from a Christian perspective. Moreover,

RFD’s characterisation suggests that such critique stems more from Gan’s personal interpretation of the Christian faith than the religious norms.

Regarding

RFD’s value in illustrating rural Protestantism, I agree with Gan’s claim that there is a dearth of cinematic representations of Chinese Christianity: ‘There are 80 million Christians in China; where are they in Chinese cinema?’ (

Qi 2013, p. 63). It is unclear how he got this figure, though. The Pew Research Center published a report in 2011 estimating there were around 67 million Christians in mainland China, approximately 5% of its population. China’s official figures are much lower, with around 28 million Chinese Christians in the same period (

The State Administration for Religious Affairs 2013). This is probably because the state’s demographics only consider those state-sanctioned churches, neglecting many believers in underground ‘house churches’, and unregistered churchgoers may hide their religious identity to avoid penalties (

The Pew Research Center [2011] 2013;

Hackett 2023).

1 In any case, the Christian population grew in the Reform era since the party-state released a tolerant religion policy in 1979, ‘The Basic Viewpoint and Policy on the Religious Affairs during the Socialist Period of Our Country’ (

Hackett 2023;

Forney 2005;

Yang 2012, p. 75).

2 Although the Christian proportion is small in the total population, its expansion during the Reform era still deserves greater visibility in Chinese cinema. Telling the stories of social minorities also marks the positioning of independent filmmaking.

RFD is situated in a poor village in Henan, Qiliying, which is Gan’s hometown (

M. Li 2012, p. 98). Therefore, this film is also Gan’s autobiographical reflection on his religious quest. For example, he re-enacts his own wedding in the village’s church where he got married. He plays a cameo role with the same given name, Du Xiao’er, who returns home from an urban area (

Yaoyao Zhang 2008). He also recruited actors from the neighbourhood, asking them to play characters based on themselves, with the same occupations and names.

3 Centring on Xiao-Li, the heroine, Gan depicts a rural Christian’s personal and communal everyday life. Gan uses long shots to show the church’s façade and interior so the audience can see the pews and platform in a deep focus frame. The church functions as a public space for the villagers’ important life events, including weddings and burials. Xiao-Li has been practising in the church’s brass band to celebrate Du Xiao’er’s wedding, while she is busy working as a deliverer and looking after her daughter Shengyue and sick husband Xiao-Lin. The part of the brass band is recorded in

RFD with a detailed depiction, serving to record local Christian activities more than to deliver the narrative efficiently. Xiao-Li prioritises the service in the brass band even above her delivery work when there is a time clash, but the newlyweds are not her close friends. This plot shows Xiao-Li’s commitment to her religious life, and it is inspired by Gan’s real experience. At his father’s funeral, the church choir, wearing military-style uniforms, sang for the service calmly and peacefully. At Gan’s wedding, the brass band carried all the instruments to welcome him and the bride, parading through the village. Gan regrets not carrying a digital camera then; otherwise, he could have documented the events. Hence, he recreated the scenes to leave a record of the local Christian activities (

Kuo 2012;

Yaoyao Zhang 2008).

RFD also portrays Christianity by comparing the behaviours of Christians and non-believers. In response to the protagonist’s family difficulties, their Christian and non-Christian friends have distinct reactions. Xiao-Lin’s old friends in the village, Yongliang, Teacher Du, and Shunjun, show little care for the sick man’s family. Yongliang visits Xiao-Li’s home once, claiming they will support her family, but they take no action. Du is also Shengyue’s teacher, who recognises that she is a good student, but the tuition fee is unaffordable. He does not help either and only visits Xiao-Li after Shengyue has been suspended, explaining that it is because of the arrears. Gan leaves an ironic tone for this scene. After Teacher Du’s visit to Xiao-Li, Shunjun drives to her house and takes Du to gamble with other friends. Shunjun derides that Du has just received his salary and he will ‘tithe’ in the game, mocking the Christian custom. They can clearly sponsor their sick friend’s family, but they would rather gamble away the extra money. In contrast, the Christian fellows offer concrete support to Xiao-Li as a caring community. While Xiao-Lin’s old pals have never visited him in the hospital, Xiao-Li’s church friends visit and pray for the patient. They also raised funds to support her family, attributing that to God’s love. They also care about the non-believers. A hospital worker seeks help from them because her nephew catches a high fever, while the doctor cannot help. She has heard that Christians could cure illness with a magical ‘bath’. Therefore, those Christians visit the boy suffering from high fever and pray for his cure, clarifying that healing comes from prayer and not any magical ‘bath’.

This scene echoes studies showing that many rural Christians in China exhibit traits of treating their religion as a traditional folk belief, as they rely on a supernatural power for well-being (

Bays 2003, p. 496). This trait is also observed in

TOS when Shui once adopts a pragmatic attitude towards Christianity, hoping that divine intervention will be ‘effective’ to help him overcome his difficulties. However, Yam argues that

RFD’s representation of rural Christianity generally lacks the typical characteristics of a popular folk belief (

Yam 2013, p. 99). On the other hand, the healing prayer demonstrated by the Christian fellows exemplifies how they practise the teaching ‘Love your neighbour as yourself’ in the Bible (Mark 12:31 [NIV]), even if their neighbours do not love them. After Teacher Du leaves Xiao-Li’s home to gamble, Shengyue not only prays for her family’s troubles but also for God’s acceptance of Du. Such a depiction is less an ethnographic representation of rural Christianity than an ethical response to the materialistic postsocialist condition. However, Gan is unsatisfied with the binary opposition between good Christians and bad non-believers. Instead, he illustrates how Christianity is enmeshed with worldly social, cultural, and political forces, on the one hand, and he delves deeply into the inner world of Christians, on the other hand. Hence, his films blur the lines between good and bad, showing how ‘holy’ religion intertwines with the ‘unholy’ world.

Yam points out that Gan’s films go beyond the level of personal lives to indirectly interrogate the systemic and oppressive forces underlying the characters’ troubles. These forces, termed ‘structural evil’, drive characters to engage in wrongdoing (

Yam 2013, pp. 100, 102). As Xiao-Li struggles to make ends meet by delivering goods, she takes orders to transport bricks for Shunjun, the rudest and most selfish man in the neighbourhood. However, Shunjun uses those bricks to build a construction (with no real purpose) exactly where a new railway will pass through to claim the government’s compensation. That is a fraud, and Xiao-Li is an accomplice. Moreover, she took those bricks from the construction site behind a school that is supposed to own them. That is theft. In a way, the clearly ‘bad guy’ Shunjun at least enables Xiao-Li to earn a living. Gan shows this with a very long shot: Shunjun and his workers are building a brick construction in the field, while Xiao-Li rides her tricycle along the road in the far background, barely recognisable to the audience (

Figure 2). Gan keeps a distance not only visually but also by refraining from making moral judgements about his characters.

Like Xiao-Li in RFD, Shui in TOS is also entrapped by the structural net of sin that is symptomatic of the postsocialist condition. In the cases of Shui and Shunjun, their misbehaviour or exploitation of others may be attributed to the lack of moral values in a materialistic society. But what about Xiao-Li, a gentle Christian woman? Although both films depict the hardships of the underprivileged, the two protagonists show different attitudes to their predicaments based on their religious faith. In TOS, the lack of moral norms and Shui’s malicious acts that seem necessary for survival have generated guilt, signifying his spiritual need. On the other hand, despite financial and health crises in her family, Xiao-Li maintains church life as usual and never gets sentimental, suggesting a peaceful spirit from her faith. She often remains silent and calm, leaving her underlying thoughts and emotions unspoken. When asked about Xiao-Lin’s health, which is actually worsening, she simply responds with ‘Okay’. It is not easy for the audience to understand her inner struggle, if any, through her facial expression or speech. Her self-restraint mirrors Gan’s preference for wide shots and long takes with minimal dialogue, demanding the audience’s patient understanding. The cinematographic and psychological distance creates an empathetic space for the audience as they witness Xiao-Li’s wrongdoings.

What the audience may find most ethically dubious is Xiao-Li’s decision to use the donation from her church fellows for Xiao-Lin’s treatment to pay for Shengyue’s tuition arrears. This action means the termination of Xiao-Lin’s treatment, resulting in his discharge from the hospital. He dies while Xiao-Li is riding him home on a tricycle. Gan inserts a segment of Xiao-Li’s memory, finally allowing the audience a glimpse into her mind through a sudden change in visual style. In Xiao-Li’s recollection, it was the healthy Xiao-Lin who gave her a joyous ride. The director employs a warmer and softer tone, with slow-motion sequences and a close-up shot of Xiao-Li, which is rarely seen, to enhance the contrast between past and present. This part is also muted, drawing the audience into the scene. The departure from the realist style throughout the film conveys the ‘inner reality’ of the heroine. The sweetest memory is juxtaposed with the grimmest moment, mirroring the inseparable nature of ‘good and evil’ and ‘grace and sin’. Gan notes that Xiao-Li has de facto killed her husband, but ‘it is God’s matter to judge’ (

M. Li 2012, p. 108). The film ends with a repetitive dinner scene: Xiao-Li and Shengyue set everything on the table, the mother remains silent, and the daughter says grace, which is their usual routine. This time, they exchange glances, Shengyue smiles blissfully, and Xiao-Li finally expresses a moment of ease. Grace is found in the most ordinary moment. Recalling the scene where Shengyue prays for Teacher Du and her family, she asks God to ‘remove Papa’s suffering’. In a way, God answers through Xiao-Lin’s death. Yam notes that death in

RFD is accepted as a solution to the hardship of the protagonist’s family, as they are Christians who believe death is only temporary (

Yam 2013, pp. 99–100). On the other hand, many of Gan’s Christian fellows, in reality, do not appreciate such an ambiguous ending; as Zito remarks, they are anxious about ‘the semiotically complicated and yet stylistically unguided viewing of the husband’s painful, wheezing death’ (

Zito 2015, p. 254). These readings indicate the inherent tension in Gan’s films regarding the representations of Chinese Christianity, as the director is not satisfied with merely representing religious activities in a documentary style nor does he wish to engage in religious promotion.

RFD’s moral ambiguity indicates that Gan’s intended representation of people’s spirituality in postsocialist China blurs the line between the ‘holy’ and the ‘unholy’. Both Christians and non-Christians cannot escape the structural net of sin, so the audience is invited to empathise with the characters instead of judging them.

4. (Un)holy Mother in Waiting for God

In Waiting for God, Xiaoyang is the leader of a local Protestant ‘meeting point’ in a village under the supervision of Pastor Wang in a government-sanctioned church. Xiaoyang’s marriage is not accepted by the church members because her husband is a non-believer, and her pregnancy is deemed scandalous. Her proposal to recruit her non-Christian friend as the village choir’s instructor is also rejected by Wang. Xiaoyang is perplexed by the religious demand to separate the ‘spiritual’ and the ‘non-spiritual’, struggling to maintain her marriage and keep her baby. Finally, she finds inspiration and comfort through encounters with people outside the church institution.

Yam proposes that a religious critique of the individualistic salvation prevalent in Western churches can be found in the representation of the Christian community in

RFD, and such individualism could be corrected by the Chinese communal culture (

Yam 2013, p. 101). However, ironically, Gan’s third film,

Waiting for God, presents an individualist critique of the local churches, following the criticism received by

RFD from many Christian viewers. Furthermore, some church leaders refused financial or venue support, believing Gan’s scripts were not ‘holy’ or ‘spiritual’ enough.

4 A professional actress also resigned from

WFG for similar reasons. Gan decided to make

WFG ‘a very lonely film’ in response to the ‘censorship’ imposed by his own religion (

Qi 2013, p. 64). The film’s title is borrowed from that of a book by Simone Weil (1909–1943), a French female philosopher. In her correspondence with a Catholic priest, she wrote, ‘You give me pain by writing that the day of my baptism would be a great joy for you’ and explained why she refused to join the Church while believing in God (

Weil 1951, pp. 92–95). In Gan’s interpretation, the priest’s insistence on getting Weil baptised was threatening (

Qi 2013, p. 64). In this sense,

WFG is a genuine religious independent film seeking liberation from within, challenging the ‘holy/unholy’ binary.

WFG’s heroine, Xiaoyang, is a church worker with a Christian name ‘Maria’. She is afflicted by the restrictive separation of the ‘holy’ or ‘spiritual’ from the ‘unholy’ or ‘worldly’ in the Church. There is a tension between this exclusive differentiation and the calling to love others, primarily her non-Christian husband, Guo Ling. Their marriage is not recognised by her church, particularly because Guo is a carpenter making statues for other religions or ‘idols’ from the Christian perspective. Xiaoyang loves her husband but also finds she cannot love him, so she tries to avoid him. Furthermore, she is accused of adultery by a church sister, Miriam, who finds out she is pregnant. Hence, Xiaoyang also considers having an abortion. Her bond of love is deemed scandalous by a religion elevating love. Another conflict comes from Xiaoyang’s recruitment of the church choir’s instructor. Although her music-major friend, Xu Feng, volunteers for the post, Xu is rejected as ‘non-spiritual’ by Xiaoyang’s supervisor, Pastor Wang, who prefers a Christian one. Unlike Gan’s previous films, Christianity in WFG appears as a source of frustration and restriction instead of hope and liberation.

Kristeva’s concept of ‘abjection’ helps us understand the Church’s exclusion of the ‘unholy’ or ‘non-spiritual’. Abjection refers to how a subject or community constitutes and stabilises its identity by excluding anything that may threaten its borders (

Kristeva 1982, pp. 2–4). Kristeva notes that abjection is essential to sustaining religious identity, especially for monotheistic religions such as Christianity: ‘Abjection accompanies all religious structurings’ and ‘takes on the form of the exclusion of a substance (nutritive or linked to sexuality), the execution of which coincides with the sacred since it sets it up’ (

Kristeva 1982, p. 17). For Pastor Wang and Miriam in

WFG, Christians’ sexuality, marriage, and church services have to remain ‘holy’ by excluding the ‘unholy’, differentiating Christians and non-believers so that they can sustain their religious identity. Hence, they find Xiaoyang’s behaviours problematic. The excessive accusation of ‘adultery’ by Miriam is a case of such abjection. However, if the Church is established in this world and wants to grow as Wang desires, how can it set a concrete border between themselves and the non-believers? Gan questions if such separation is possible by depicting the interaction of Xiaoyang and various non-believers who also recognise that Christians and they are different. Xiaoyang places an order in a welding workshop to make a marching baton with a cross for the church’s band. The shopkeeper complains that he feels wronged by the Christian notion that he is cursed to Hell after death just because he does not believe in God. Later, a taxi driver asks Xiaoyang what Christians will do in Heaven, and she answers that they will be in joyful communion with God. The driver sniffs that life in Heaven is too boring. Xiaoyang does not argue with them, although these non-Christians may have misconceptions about the Christian faith. Gan tries to show the non-believers’ general perception of Christianity as an instance of reflection. If these people are the Church’s other, their interactions with Xiaoyang suggest that Christianity becomes ‘the other of the other’. The abjective attitude that over-emphasises the ‘holy’ Christian and ‘unholy’ non-believer only creates further alienation.

Gan’s cinematography visualises how the Christian ‘holy’ and the secular intertwine. He uses long close-up shots to capture the crafting process of what is deemed ‘spiritual’, as Xiaoyang watches how the welder makes the march baton and attaches the cross to it. The holy sign of Christianity, made of metal, comes from the hands of an ‘unholy’ non-believer (

Figure 3). The close-up accentuates the paradox of ‘holiness’. Ironically, Guo, Xiaoyang’s carpenter husband, is criticised by other Christians for making idols for other religions. Gan only uses medium and long shots for Guo’s crafting process, avoiding any detail, and suggesting an indifferent attitude to his religious status. If a cross attached to a band baton made by non-believers can be used in religious activities without its ‘holiness’ diminished, why would a carpenter get attached to and devalued by his job crafting statues?

Pastor Wang exposes his double standards as a local Christian leader whose position is entangled with the secular world. He approves of Buddhism’s strategy to promote itself through popular music without diminishing what is ‘non-spiritual’ out of pragmatic concerns. He also greets a Buddhist nun he has met at the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference as they serve as advisors representing various state-sanctioned religions. Thus, while he does not allow a non-believer to serve in the church’s choir, he works with other non-Christians on the political platform under an atheist authority. Wang also tells Xiaoyang how he admires a church leader in Wenzhou who can earn a higher income than many civil servants, exclaiming, ‘How he glorifies God!’ This scene exemplifies Gan’s religious sense of postsocialist critical realism, interrogating the religion’s hypocrisy. In the Reform period, when market economy combines with socialist politics, religions do not escape the dominance of these worldly influences. Wang as a Church leader takes the logic of money and power for granted for the privileged group in society. He does not apply the separation of the ‘holy’ or ‘spiritual’ and the ‘unholy’ or secular to all aspects of the religion but arbitrarily forces that on others in the weaker position.

Xiaoyang demonstrates an alternative understanding of the Christian faith expressing spirituality in the world, distinct from what Wang and Miriam claim. Here, motherhood in Gan’s films suggests how the Christian faith should be a loving, tolerant, and liberating force if this is the spirituality that people need. Mothers in Gan’s features are quiet. In

TOS, Qiuyue is a submissive wife to Shui, who does not respect her autonomy. She is kept away from making the decision to rent her body as a surrogate mother. Her final resistance to the patriarchal dehumanisation of her dignity is suicide. In

RFD, Xiao-Li is also quiet, but she takes a more active role in the household. She is still surrounded by men in dominant positions, such as Shunjun and Teacher Du, but her subjectivity is shown by her decision to terminate Xiao-Lin’s treatment as the cost of sustaining Shengyue’s education. In

WFG, Xiaoyang is comparatively more empowered, better educated, and has a decent job. However, like Qiuyue, Xiaoyang suffers from a lack of bodily autonomy because the Church disapproves of her marriage and pregnancy. Qiuyue’s case exemplifies that many rural Chinese women have been trapped in their domestic roles and reduced to their reproductive function in a patriarchal society (

X. Li 2005, p. 143). In contrast, Xiaoyang’s story suggests maternity’s critical potential in the quest for a liberating spirituality of love. Kristeva’s conception of motherhood provides an interpretive framework to understand Gan’s feminine critique of Christianity in postsocialist China.

Kristeva argues that the mother-and-child relationship plays is key to the formation of a subject. She borrows the term

chora (receptacle or space) from Plato, denoting ‘an essentially mobile and extremely provisional articulation constituted by movements and their ephemeral stases’, that ‘precedes and underlies figuration and thus specularisation, and is analogous only to vocal or kinetic rhythm’ (

Kristeva 1982, pp. 93–94).

Chora is the maternal space where the baby goes through the ‘semiotic’ stage that is not yet ‘cognitive in the sense of being assumed by a knowing, already constituted subject’, and before one can manage the logic of signification and become the speaking subject in the symbolic order (p. 95).

5 However, the semiotic does not fade when the subject of language is formed; rather, it constitutes a dialectic relation with the symbolic in that they ‘are inseparable within the signifying process that constitutes language’ (p. 92). Before the infant can master language, they experience ‘primary identification’ as a ‘subject of enunciation’ who receives and copies the loving mother’s words ‘as a gift’ (pp. 244, 256). This loving mother is also the ‘passionate mother’ who is ‘at the crossroads of biology and meaning’, and her emotions to her child sublimate into passion, allowing the child to become autonomous via their detachment from the mother (

Kristeva 2005).

This essay proposes that Gan’s films provide a religious space functioning like a maternal space, the semiotic

chora and that the interaction between Christians and non-believers, exemplified by Xiaoyang, can be seen as a process like that of the ‘passionate mother’ essential to the formation of the autonomous and loving subject. For Kristeva, the maternal passion and the relationship with the mother constitute the prototype of other love relations, which is embodied by the Virgin Mary, the mother of Christ (

Kristeva 1985, p. 136;

2005). At first, the pregnant woman loves herself and the man she loves who makes her conceive the baby. After the baby is born, the passionate mother goes through a ‘depassioning’ process, detaching herself from the baby so that the latter can grow up as autonomous. A transitional space is created when the mother lets go of her child (

Kristeva 2005). Gan’s films re-examine the meaning of love in Christianity, asking if this religion can be a place where people learn to love and become autonomous loving subjects.

In

WFG, Pastor Wang cites the Biblical verse ‘Do not be yoked together with unbelievers’ (2 Cor 6:14 [NIV]) regarding the separation of the ‘spiritual’ and the worldly, suggesting a solidified understanding of Christian faith that allows him to judge the non-Christian as sinful. A similar solidified perception of Christianity is also observed in the welder who dislikes the idea that non-believers will go to Hell. However, Xiaoyang’s pregnancy provides an ambiguous space for rethinking the meaning of love. On the one hand, her church fellows abject her marriage and unborn baby as sinful others who are threatening their religious identity. On the other hand, this foetus as an

other creates a passionate bond with Xiaoyang, although that could cause an identity crisis: ‘the pregnant woman is losing her identity, for, in the wake of the lover-father’s intervention, she splits in two, harbouring an unknown third person, a shapeless pre-object’, leading to ‘violent emotions of love and hate’ (

Kristeva 2005). Xiaoyang’s case is complicated by her religious identity in that Wang appears as the symbolic father in the religious family. Hence, Xiaoyang has once considered giving up her ‘unholy’ family.

It is Xiaoyang’s non-Christian friend, Xu, who helps Xiaoyang clear her mind. Their female bond is an irony of the Church’s claim as a community of love, as a genuine reciprocal relation is developed across the religious differences of the two women. In response to Xiaoyang’s perplexity and the thought of abortion, Xu confesses that she had an abortion once because she does not commit to the present relationship with her lover. However, she feels guilty and sad when she practises the Christian song

Away in a Manger for having abandoned her child. While baby Jesus, although ‘No crib for a bed’, still had a manger to lay, her unborn baby has nowhere to rest. Thus, the aborted foetus is not just a piece of flesh but a lost soul and a possible life in her spiritual imagination prompted by the holy song. The manger functions as a receptacle (

chora), holding the mother–child bond in moments of grief, also signifying the empty womb after abortion. In Adriana Cavarero’s interpretation,

chora is the sphere ‘where rhythmic and vocalic drives reign’, highlighting the musicality of the semiotic (

Cavarero 2005, p. 133). Contrary to the rigid separation of the ‘holy’ and ‘unholy’ by Wang’s words, the symbolic father’s petrified language, the holy song creates a feminine space that goes beyond words, allowing for the expression of maternal emotions. Xiaoyang comforts Xu that God will take care of her unborn child—without quoting the Bible—but why does she claim so?

Xiaoyang’s approach to communicating her faith can be explained by Kristeva’s elucidation of witticism between mother and infant. The passionate mother can use witticism as the ‘enigmatic signifier’ to teach her infant child how to use language. The child has to guess what the mother signifies. Whether or not the child can grasp what the mother intends to communicate, pleasure is generated when she focuses on the infant’s response. For such pleasure to appear, the mother has to leave room for the infant to explore the enigma of signification and create various possible meanings. That is the depassioning process through which the child learns to be an autonomous thinking subject (

Kristeva 2005). What Christian faith means in the communication between Christians and non-believers is similar to the ‘enigmatic signifier’. In response to the welder who feels bad about being cursed to Hell by Christianity, Xiaoyang does not argue with him, simply reassuring him that ‘God loves you’. The welder is pleased by her ‘witticism’, although he may not know what those words really mean. While Wang’s approach to talking about faith is suffocating and leaves no room for the creation of new meanings, Xiaoyang’s response is attentive to others’ needs. (Clearly, the welder needs a blessing more than a curse.) Her expression of faith is contextualised for the others’ experiences, allowing a space to explore different possibilities of the Christian faith. Reconciliation replaces separation between the ‘holy’ and the ‘unholy’.

Gan gives a Christian name ‘Maria’ to Xiaoyang, making her analogous to the mother of Christ. Contrary to Wang, Xiaoyang can be seen as a mother figure who provides an inclusive and creative

chora where faith could be born for non-believers. In

TOS, Shui’s final hope is found in the Christian faith, which reveals the possibility of a new life. That is how he becomes spiritually free; as Kristeva says, ‘Being free means having the courage to begin anew’ (

Kristeva 2005). In

WFG, Xiaoyang acts like a loving ‘spiritual mother’ who values others more than the doctrine, allowing the non-believers to explore what Christianity means and opening a possible space for any spiritual ‘new life’ to grow. Not only is Xiaoyang compared with the Virgin Mary, but her family is also an analogy to the Holy Family. While the Holy Family presents an ideal model of the Western bourgeois family, it is often problematised in cinema (

Fritz 2015, pp. 184, 187). In

WFG, Gan questions the Church’s abjective approach to the ‘unholy’ by making Xiaoyang’s scandalous family analogous to the Holy Family. Actually, the Virgin Mary’s conception of Jesus could also be scandalous according to Mosaic Laws. If her pregnancy was seen as proof of adultery, then she might be stoned to death (

Koschorke 2003, p. 19). The Holy family consists of two overlapping triangles with two fathers: the Heavenly Father and Joseph, the ‘adoptive father’ of Jesus (pp. 11, 20). The Holy Family is inherently ambiguous, but this ambiguity also facilitates the connection between the ‘holy’ and the ‘unholy’ through Mary’s body, where the sacred enters the profane world (pp. 25–26, 47). Hence, the Holy Family signifies the dissolution of the boundary between what is legitimate and not, leading to joy instead of threat, as the Word became flesh to liberate and not suppress (pp. 54, 59).

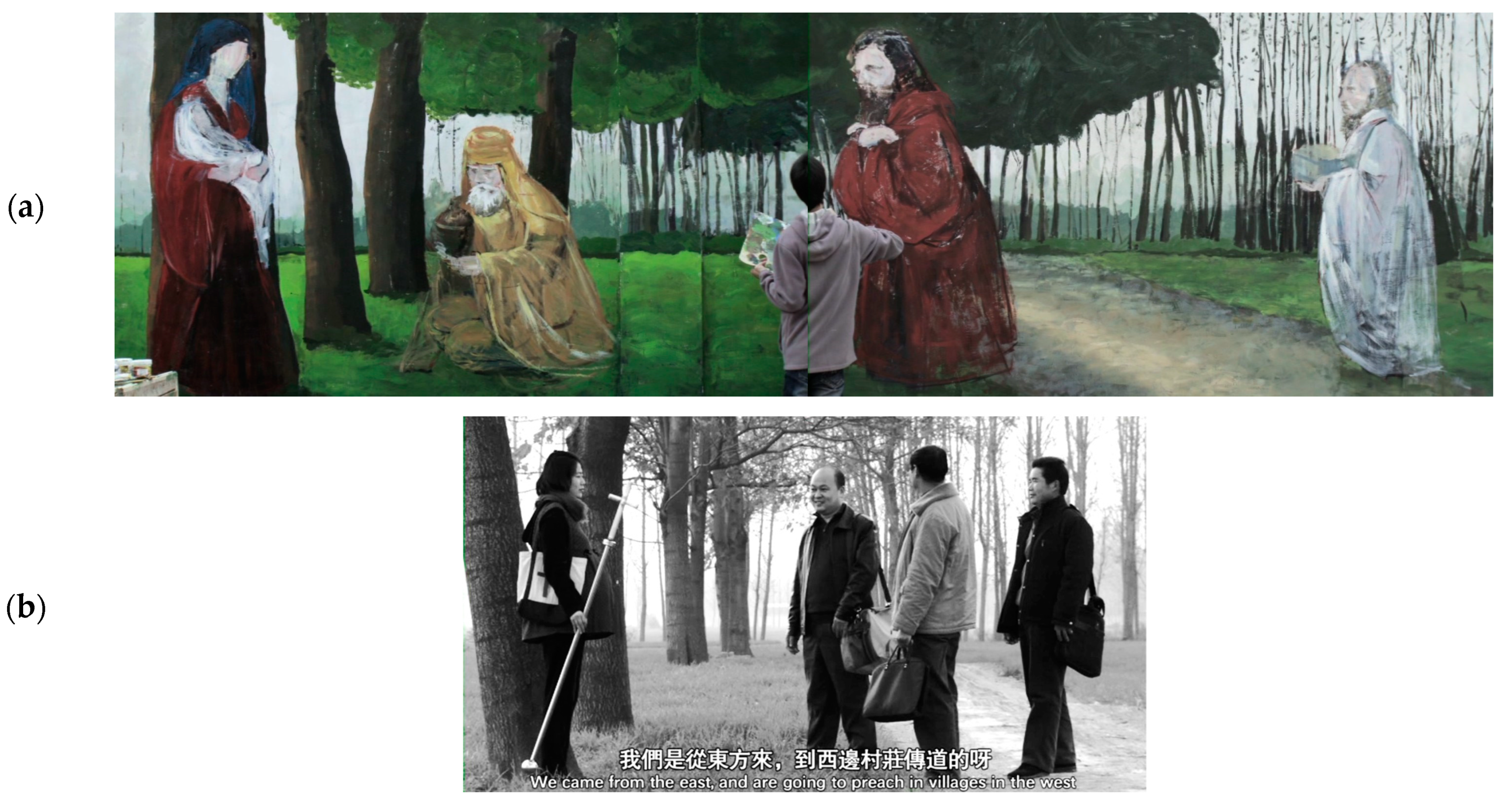

WFG’s chromatics present such joy. Near the film’s end, Xiaoyang encounters three itinerant preachers ‘from the Eastern’. They bless her family and propose that Guo, her carpenter husband, could adopt the Christian name ‘Joseph’ after the husband of the Virgin Mary, should he choose to convert to Christianity. These three preachers correspond to the three Magi who came from the East to witness the birth of Jesus Christ (Matt 2:1–12). Gan highlights this analogy through colour management.

WFG is mostly monochromatic except when Xiaoyang sees a mural in the church depicting Mary’s encounter with the three Magi (

Figure 4a). The composition and content of this only colourful scene in the film are similar to those when Xiaoyang meets the three travelling preachers (

Figure 4b). The mural scene visualises the inner world of the contemplative heroine, infusing vitality and hope into her vexation. It also anticipates the arrival of the three wise men, who reassure Xiaoyang that her family is blessed. We can see these preachers as the stand-in for the director Gan, who suggests a non-institutional interpretation of the Christian faith.