Abstract

The literature on clientelism, the informal exchange of benefits for political support, has proliferated over the last three decades. However, the existing literature largely ignores the role of religion in shaping clientelism in contemporary politics. In particular, few attempts have been made to explore the relationship between religious ideology and clientelism at the party level: How does political parties’ religious ideology impact their clientelist linkages with citizens? This study uses cross-national data of parties in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) from the V-Party database (1970–2019) to answer this question. Our findings reveal that religious parties are more clientelist than secular parties in the MENA. Particularly, parties’ ties with social organizations mediate the relationship between religious ideology and clientelism. This study extends the literature on the impact of religion on informal political institutions by focusing on the ideology and linkage strategy of political parties in the MENA.

1. Introduction

The literature on clientelism has burgeoned over the last three decades. In swiftly evolving societies, particularly in low- and middle-income countries, political decay has occurred to varying degrees (Huntington 1968), with clientelism emerging as one of the most notable expressions. This phenomenon is closely related to the weakness of political institutions and a political culture characterized by strong traditional hierarchies. The concept of clientelism has roots in the pre-modern informal patron–client relationship as a mechanism for exchanging benefits (Scott 1972). In contemporary politics, clientelism is defined as a form of linkage strategy through which political parties distribute targeted benefits in exchange for electoral support (Kitschelt and Wilkinson 2007; Hicken 2011; Stokes et al. 2013). The existing literature explains the variations in clientelism mainly from two theoretical perspectives: the state and party levels. State-level factors primarily emphasize the impacts of economic development, democratic experience, and election competitiveness on clientelism (Bustikova and Corduneanu-Huci 2011; Robinson and Verdier 2013; Keefer 2007; Kitschelt and Wilkinson 2007; Schady 2000). Some scholars have examined the influence of various features of party organizations on clientelist linkages at the party level. Parties’ share of power in national decision-making institutions is correlated with their ability to use clientelist linkages, with centralized parties being more likely to employ clientelist strategies (Yıldırım and Kitschelt 2020; Kitschelt and Wang 2014).

In addition to the factors mentioned above, political culture refers to the shared values, beliefs, and norms about politics within a society, which also plays a crucial role in shaping the nature of political institutions and practices (Huntington 1968), including the prevalence of clientelism. In particular, an increasing number of scholars have focused on the influence of religion on clientelism, given that religion forms deep-rooted values that underlie more ephemeral political norms (Laitin 1978; Williams 1996). Some studies have highlighted religion as a cultural attribute that affects the prevalence of clientelism in societies (Paldam 2001; Ko and Moon 2014). Religion plays a legitimizing role in employing clientelist strategies in Christian Mediterranean countries and Latin American countries, thereby facilitating such exchanges within society. Religious sources are invoked to declare moral judgments while administering civil affairs of government (Graziano 1973; Markoviti and Molokotos-Liederman 2017; Marangudakis 2019; Blancarte 2023). In addition, clientelism is particularly prevalent in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), and Islamism, as one of the major political cultures in the region, has had a profound effect on clientelism (Langohr 2001; Clark 2004; Lust 2009). However, the most recent work by Corstange and York (2021) compared Muslim and non-Muslim countries and showed that clientelism is not linked to cultural characteristics, but rather to its pervasiveness in Muslim society. Other studies have examined the impact of clientelism through the lens of the relationship between religion and state (Sommer et al. 2013; Tusalem 2015; Patrikios and Xezonakis 2019). Among them, Patrikios and Xezonakis (2019) explored the relationship between government intervention in religious competition and clientelism and concluded that uncompetitive religious markets were more likely to favor clientelism.

Despite the growing literature on the impacts of religion on clientelism, the majority of research regarding the role of religion in explaining variations in clientelism focuses on the state level, largely neglecting the party-level dimension of religion and its effects on clientelism. Specifically, comparative studies across countries that examine the influence of Islamic ideology on clientelism are notably lacking. Religion as a political resource is both a culture and an ideology (Williams 1996). In the modern political system, political parties are important actors in the exchange of clientelism. Therefore, a more detailed study on the impact of parties’ religious ideology on clientelism is warranted. Religious ideology takes a crucial place in party competition across regions, from Evangelicalism and Protestantism in the United States and Latin America to Christianism in Mediterranean countries and Western Europe (Woodberry and Smith 1998; Arzheimer and Carter 2009; Reich and Dos Santos 2013; Delehanty et al. 2019). Islamism, as a religious ideology, is a constant and prominent feature of party politics in the MENA (Sarfati 2013; Mohseni and Wilcox 2016). Due to the region’s long colonial history and top–down modernization movement, the Islamist–secular divide has become an important dimension of party ideology in the MENA (Hashemi 2009). Furthermore, clientelism is prevalent in the functioning of society in MENA countries with weak democratic institutions and a lack of electoral accountability (De Elvira et al. 2018). Therefore, the MENA region has become one of the most representative regions for studying the impacts of religious ideology, particularly Islamism, on clientelism. However, scholars of MENA studies have not paid sufficient attention to the association between the party’s Islamist ideology and clientelism across countries. The following question remains unanswered: How does parties’ religious ideology impact their clientelist linkages with citizens in the MENA? We approach the question from a functionalist perspective, emphasizing the social role of religion, wherein religious ideology serves as an important social tool in clientelistic exchanges (Berger 1974; Durkheim 1995; Schilbrack 2013). Here, religious ideology can be defined as a set of beliefs and values rooted in religious traditions that shape a party’s policy positions and organizational behaviors (Williams 1996). We employ the concept of “religious parties” as encompassing parties that hold an ideology or a worldview based on religion and mobilize support based on citizens’ religious identity (Brocker and Künkler 2013).

Therefore, this paper aims to examine whether religious ideology explains the variations in clientelism at the party level in the Middle East from 1970 to 2019. We investigate the unanswered research question with data from the Varieties of Party Identity and Organization (V-party) dataset, which is the most comprehensive database covering cross-national data of political parties in the MENA. We find that political parties with stronger religious ideologies are more likely to employ clientelist linkages in the Middle East. Additionally, the association between parties’ religious ideology and clientelistic practices is mediated by their ties to social organizations. The remainder of this article is structured as follows: Section 2 presents the theoretical background and develops testable hypotheses about the impacts of parties’ religious ideology on clientelism. Section 3 introduces the data, variables, and models used in this study. Section 4 provides a statistical analysis and key findings. In the final section, we conclude with the findings, limitations, and future research directions.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

During party competitions, parties typically rely on a variety of linkage strategies to attract voters. Most models of party competition in advanced democracies assume that parties attract voters through programmatic linkages, in which they can offer broad policy packages and ideologies (Kitschelt 2000; Calvo and Murillo 2013). In programmatic politics, the policy and ideological positions provided by political parties are directed to all citizens, regardless of a citizen’s voting decision in the election. In contrast to programmatic linkages, citizens can cast their votes based on the targeted benefits they receive in exchange for electoral support. Clientelist linkages involve an exchange between politicians and citizens, characterized by contingency, hierarchy, and iteration (Hicken 2011). The particularistic benefits delivered by clientelist parties can be in the form of cash transfers, consumer goods, and public jobs (Albertus 2013; Stokes et al. 2013).

Some scholars argue that parties that attempt to diversify their linkage strategies and simultaneously pursue different types of linkage will face more trade-offs. The main reason for this is that programmatic politics is based on universalistic principles, while clientelism emphasizes particularism and informal distribution, causing significant conflicts in the purpose and nature between the two (Kitschelt 2000). However, increasing research indicates that parties’ ideological appeal and clientelist linkages are not mutually exclusive (Weghorst and Lindberg 2013). Political parties and politicians are rational actors that simultaneously utilize both ideological appeal and clientelist material benefits to maximize their votes in election competitions. Ideology serves as a shortcut for political parties to communicate with voters and is an important “information product” provided by political parties to voters. Voters need to rely on the ideology of political parties to understand their positions and save time in voting based on their own interests (Downs 1959). Moreover, ideology acts as a facilitator of clientelistic transactions, as ideological affinity enables parties to effectively target core voters (Schady 2000; Nichter 2010). Empirical evidence from the existing literature demonstrates that right-wing ideologies significantly influence the use of clientelism (Tzelgov and Wang 2016).

In addition to the left–right ideological spectrum, it is noteworthy that religious ideologies likewise exert influence on clientelism. In contrast to the dominance of left–right ideologies in developed democracies, the religious–secular divide has become a prominent dimension of the ideological spectrum for political parties in low- and middle-income countries, especially in the MENA countries with a long colonial history and top–down modernization processes (Hashemi 2009). The character of left–right political dynamics in the Middle East departs from the conventional framework observed in developed democracies, exhibiting a degree of inversion in traditional left–right ideological positioning. In the MENA, right-wing parties by Western political norms may advocate left-wing ideology in terms of economic intervention by the state, social welfare expenditure, and other issues (Aydoğan and Slapin 2013). Thus, the role of left–right wing ideologies in party behaviors in the region has some limits of explanatory power. In addition to this, nationalism has a significant influence on the ideological cleavage of Middle Eastern political parties. Nationalist ideology germinated after the invasion of Western colonizers and the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. In the MENA, nationalism has evolved in party politics into reactionary nationalism, characterized by a desire to return to a perceived previous state of national strength, and progressive nationalism, which seeks to reconcile national identity with progressive values such as emancipation and social justice (Razi 1990; Kramer 1993; Dawisha 2003).

However, despite the complex political and cultural context of the MENA, the religious–secular cleavage dominates the ideological spectrum, with even some global comparative studies supporting the unique importance of the religion–secular dimension in party competition in MENA countries (Benoit and Laver 2006). The dominance of the Islamist–secular divide in party competition in the region can be traced back to the 1970s. In the ideological spectrum dominated by the religious–secular divide in the MENA, the ideologies of most parties located at the ends of the spectrum can be labeled as “conservative/Islamist” and “secular” (Wegner and Cavatorta 2018). It is important to note that the ideological divide between the religious and the secular is not simply mapped as a linear adjustment of right-conservative and left-secular appropriation. Middle Eastern political parties sometimes espouse left-wing conservatism, melding religious principles with socialist or Marxist ideals to champion socio-economic equality and wealth redistribution under a religious framework (Walzer 2015; Fischer 2018). The Islamist parties in the MENA countries are not passively bound by religious doctrines and historical institutional legacies, but actively construct religious discourse and narratives (Hinnebusch 2017). Islamic parties strategically leverage religious ideology, frequently employing Islam as a powerful tool and symbol, in order to mobilize constituencies and establish legitimacy for their governance. Morocco’s Islamist party, the Party for Justice and Development, became the largest parliamentary party and was in power from 2012 to 2016 (Casani 2020); in Tunisia, the Islamist party, the Ennahda, became the most prominent party in parliament in the October 2011 election (Cavatorta and Merone 2013); and the Justice and Development Party in Turkey, by leveraging its strong Islamist ideological narrative, has maintained its position in power for more than two decades (Dagi 2008; Yilmaz et al. 2020).

A party’s religious ideology bolsters its use of clientelism. Firstly, the religious ideology of political parties amplifies the benefits of clientelist linkage, serving as an incentive for parties to use such strategies. Specifically, the religious ideology of a party strengthens its ability to sway voters within a specific group by offering particularistic benefits (Dixit and Londregan 1996). Religious ideology, to a certain extent, determines the types of voters that political parties target, making it more effective to deliver material benefits to specific voter groups. According to the “core voter” theory, voter party loyalty is closely related to how parties distribute resources, and parties must favor their core voters to maintain long-term electoral coalitions (Cox and McCubbins 1986). Compared to socially and economically advantaged citizens, religious ideology, especially Islamic conservatism, has a stronger appeal to voters in economically disadvantaged positions (Grewal et al. 2019). Parties with strong religious ideologies have a greater advantage in establishing clientelist linkages with lower-income voters than secular parties. They can more effectively convert material benefits into political support. Therefore, religious ideology strengthens the incentive for parties to employ clientelism tactics.

Second, religious ideology mitigates the commitment problem in the exchange process, thereby reducing the transaction costs of the clientelist linkage strategy, consequently fostering the use of clientelism. In the process of parties exchanging specific benefits for votes, parties must ensure that voters make voting decisions that favor them after receiving the benefits (Stokes 2005). To overcome this commitment issue, parties need to use various monitoring methods to evaluate whether voters fulfill their commitments and use the collected information to further reward and punish constituencies. However, the cost of monitoring is undoubtedly high (Brusco et al. 2004). Within Muslim-majority countries in the MENA, Islamism has a certain ideological hegemony in citizens’ daily lives. Here, ideological hegemony can be understood as “the ability of one group to define reality for the majority” (Cammett and Luong 2014). From the functionalist viewpoint, Islamist ideology is an essential legitimizing tool for political parties in the MENA, which provides voters with a “credible slogan” that enables political parties to justify their solutions to current social and political problems (Tessler 2011). Its functionality primarily lies in enabling political parties to portray their socio-political agendas as correct or morally grounded by invoking Islamism, such as in response to colonialism or incompetent governments. Therefore, religious ideology enhances voters’ trust in political parties, making them more likely to keep their promises after receiving material benefits. This greatly reduces the need for parties to monitor voters and the transaction costs of clientelism.

Based on the above reasoning, the first hypothesis of this paper is proposed:

Hypothesis 1.

The party’s religious ideology has a significant positive effect on its clientelistic practices.

Clientelist linkages between political parties and voters are not always established directly. These often rely on specific intermediaries to target and transfer benefits to voters. These intermediaries, often referred to as “brokers”, play a pivotal role in facilitating the coordination between political parties and voters, helping the parties to embed into society. Intermediaries in the clientelistic network include party workers, government employees, businesses, and local elites, etc. Political parties can provide various benefits, such as cash, goods, and social services, to voters through different intermediaries in exchange for their electoral support (Hicken and Nathan 2020).

Social organizations also function as important intermediaries in the establishment of clientelistic networks. The distinguishing features of social organizations compared to other intermediaries are the presence of relatively unified ideological consensuses and organized network structures. Social organizations can coordinate members’ interest preferences and establish a collective consensus. Their preferences for specific interests make them more willing to engage with political parties that have a certain ideological orientation. In addition, social organizations have higher levels of organizational network structures, which allow them to reach a broader range of voters. Social organizations undertake the responsibility of delivering benefits to target constituencies and better monitoring citizens’ voting behaviors (Holland and Palmer-Rubin 2015; Cornell and Grimes 2022).

Religious parties establish close ties with prominent social organizations through their religious ideological affinity, helping them to better employ clientelist linkages to gain political support. Specifically, parties use religious ideology to attract social organizations with similar ideological characteristics. These faith-based social organizations have a stronger ideological and interest consensus compared to other intermediaries, making them more easily attracted by the religious ideology promised by political parties. In the process of clientelist exchange, faith-based organizations take on the responsibility of channeling targeted interests to core voters and attracting votes for politicians. In the Middle East, religious organizations and Islamic business associations with strong organizational capabilities provide religious parties with a nationwide network, helping them to distribute extensive material benefits to voters and engage in clientelistic exchanges (Cammett and Issar 2010; Brooke 2019; Freedman 2020). For example, Turkey’s Justice Development Party (AKP) is one of the most successful Islamist parties in the region, for which religious organizations and business associations have been important tools in establishing a wide clientelist network within the country (Arslantaş and Arslantaş 2023). The Deniz Feneri Solidarity Association is a representative Islamic charitable organization in Turkey with strong ties to the AKP as a social welfare provider and a broad popular appeal due to its Islamist faith base. The organization provided AKP funds and charitable donations to voters in the form of cash subsidies, household goods and medical services to better exchange votes for AKP in the election (Morvaridi 2013). In, addition, by leveraging its ideological proximity, the AKP has formed an alliance with the Islamic business association Müstakil Sanayici ve İşadamları Derneği (MÜSİAD), which has benefited Islamic businesses through the favorable allocation of contracts and economic resources in exchange for the political support of the MÜSİAD and its employees (Ocakli 2015; Gürakar 2016).

On the basis of the above theoretical propositions and empirical research, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2.

The association between a party’s religious ideology and clientelistic practices is mediated by their linkages to social organizations.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data and Sample

This paper primarily relies on data from the Variety of Party Identity and Organization (V-party) database. This novel database provides expert-coded data on party organizations and identities for most parties in most countries from 1970 to 2019, which is gradually being widely used by scholars of party politics (Lührmann 2021; Düpont et al. 2022; Reuter 2022). Following the methodology developed by V-Dem, a panel of 711 experts assessed the policy orientations and the organizational capacity of political parties across elections in a given country in January for both 2020 and 2021. Specifically, the experts coded data for all parties that received more than 5 percent of the vote in a given election. The collated data, as provided by these experts, were then synthesized within the database utilizing the Bayesian Item Response Theory measurement model that is integral to V-Dem’s approach. The database consists of data on 3467 political parties in 3151 elections in 178 countries. There are 11,898 party-election year units in 178 countries. Typically, at least four coders assessed each observation.

At present, there are limited data on political parties in the MENA. The V-party database used in this study is one of the most comprehensive databases covering political party characteristics in the MENA. We extracted data from the database of regional codes corresponding to the MENA region, obtaining unbalanced panel data covering 14 countries in the Middle East from 1970 to 2019. Hence, our study focuses on the MENA countries, comprising seven Arab republics (Egypt, Lebanon, Tunisia, Algeria, Iraq, Syria, and Yemen), four Arab monarchies (Bahrain, Jordan, Kuwait, and Morocco), and three non-Arab republics (Iran, Israel, and Turkey). Oman, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, and Saudi Arabia, where political party activities are prohibited, are excluded from the samples of this study. The dataset includes 153 political parties from the aforementioned countries. The unit of analysis is “party-election-year”.

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Dependent Variable

Clientelism is the dependent variable of this study. As an informal institution, clientelism operates with a certain level of opacity. There are multiple ways to measure clientelism in academia. In comparative studies at the national level, scholars often use measures such as the level of corruption and the quality of the bureaucratic system as proxies for clientelism. Expert survey ratings are currently the most used cross-national measure of clientelism at the party level. For example, the Democratic Accountability and Linkages Project also uses expert ratings to measure the level of clientelism of political parties across countries, but this database does not cover most political parties in the Middle East and fails to capture long-term dynamics. The measurement of the dependent variable used in this study is based on the question in the V-party database: “To what extent do the party and its candidates provide targeted and excludable (clientelistic) goods and benefits—such as consumer goods, cash or preferential access to government services—in an effort to keep and gain votes?” The original expert rating for this measurement ranges from 0 = “Not at all” to 4 = “As its main effort” to indicate the degree, and the database converts it into a continuous variable, where higher values indicate stronger partisan clientelism.

3.2.2. Independent Variable

Religious ideology is the core independent variable in this study. Measuring party ideology in the MENA poses certain difficulties. Citizens lack relevant information about the positions of different ideological parties, and the information provided by political elites may contain significant social desirability bias. Therefore, public opinion surveys and elite surveys have a low accuracy. In addition, cross-national political text analysis and roll-call voting analysis also have high costs and lack institutional conditions. The measurement of party ideology in the MENA using expert survey analysis has relative advantages (Aydoğan 2021). In this study, the religious ideology of political parties is measured based on the question in the V-party database: “To what extent does this party invoke God, religion, or sacred/religious texts to justify its positions?” The original expert rating ranges from 0 = “Always, or almost always” to 4 = “Never” to indicate the degree, and the variable is transformed into a continuous variable. To ensure logical consistency, the variable is reverse-adjusted, with higher values indicating a stronger religious ideology of political parties.

3.2.3. Mediating Variable

The mediating variable in this study is the ties between political parties and social organizations. The ties between political parties and social organizations are measured based on the question: “To what extent does this party maintain ties to prominent social organizations?” In the expert rating criteria, it is stated, “When evaluating the strength of ties between the party and social organizations please consider the degree to which social organizations contribute to party operations by providing material and personnel resources, propagating the party’s message to its members and beyond, as well as by directly participating in the party’s electoral campaign and/or mobilization efforts. Social organizations include: Religious organizations, trade unions/syndical organizations or cooperatives, cultural and social associations, political associations and professional and business associations”. The responses range from 0 = “does not maintain ties with prominent social organizations ” to 4 = “controls prominent social organizations ”, and the variable is transformed into a continuous variable.

3.2.4. Control Variables

Drawing on the existing literature, we control for indicators of other party-level factors that might influence the use of clientelist linkages. Previous studies have suggested that the party’s share of power, left–right ideology, and party centralization have impacts on its clientelistic practices. We incorporate the party’s vote share and seat share in the observed election year. We also include control for left–right ideology, given its potential impact on clientelism (Shefter 1994; Tzelgov and Wang 2016). Left–right ideology is measured based on the question: “Please locate the party in terms of its overall ideological stance on economic issues”. The original rating ranges from 0 to 6, representing the change from extreme left to center to extreme right, and is transformed into a continuous variable. This analysis controls for party centralization using the proxy variables of candidate nomination and internal cohesion. Candidate nomination is measured via the question: “Which of the following options best describes the process by which the party decides on candidates for the national legislative elections?”. The continuous variable ranges from low to high, indicating a decrease in the concentration of candidate nominations. The question for measuring internal cohesion is “To what extent do the elites in this party display disagreement over party strategies?”. The original rating ranges from 0 = “Almost complete disagreement” to 4 = “virtually no visible disagreement” and is transformed into a continuous variable. Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics of the variables in this study.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of variables.

3.3. Model Specification

According to the research hypotheses of this article, multiple estimation models are selected for hypothesis testing. Ordinary least squares regression (OLS) is used for modeling. Considering that the sample unit is “party-election year” and the core theoretical concern of this article is variables at the party level, a fixed effects model is used in the empirical analysis to control for political, economic, and cultural differences among countries in the MENA region. The regression model is as follows:

Clientelism = α + β * Religious Ideology + θ * X + γ + ε

In Equation (1), β is the coefficient of religious ideology, which is the unknown parameter of interest in this article. α is the intercept term, X is a set of control variables, θ is the coefficient of the control variables, γ represents country-level fixed effects, and ε is the error term.

Second, the step-up method (Baron and Kenny 1986) is used to further explore the mechanism through which religious ideology influences clientelism. In recent years, causal mediation analysis based on causal inference has been widely applied. However, due to the dependent variable being a continuous variable, this study still uses traditional mediation analysis methods (Imai et al. 2010). To test the mediating role of party–social organization ties, the model used in this paper is specified as follows:

Equation (2) represents the positive effect of the party’s religious ideology on its ties with social organizations. Equation (3) represents the positive effect of ties with social organizations on clientelism. If the variable of ties with social organizations is acting as a mediator, then should be significant, and under the control of , should also be significant. represents the mediating effect of the variable of ties with social organizations on clientelism.

4. Results

4.1. The Impact of Religious Ideology on Clientelism

Table 2 presents the results of the baseline regression analysis in this study. First, Model 1 adopts a pooled regression model, which shows a significant positive effect of the party’s religious ideology on clientelism. However, the pooled regression model could potentially overlook the unobserved heterogeneity at the country level, and this heterogeneity may be correlated with the explanatory variables, leading to inconsistent estimates. Therefore, this paper adopts the fixed effects model and conducts an F-test for both models. The F-test results demonstrate that the fixed effects model, accounting for individual heterogeneity, outperforms the pooled regression model. Model 2 demonstrates that, even after controlling for other relevant variables and incorporating country-fixed effects, the party’s religious ideology continues to exert a positive effect on clientelism, significantly at the 0.1% level. Specifically, holding the other conditions constant, a 1% rise in a party’s religious ideology increases clientelism by 0.275%. Therefore, parties with a stronger religious ideology tend to have higher levels of clientelism, which supports Hypothesis 1. Among the control variables, vote share positively affects clientelism at the significance level of 5%. Right-wing ideology increases a party’s use of clientelist linkages at the significance level of 0.1%. Candidate nomination affects clientelism at the significance level of 0.1%, indicating that parties with a higher level of power centralization in the candidate nomination process have a higher level of clientelism. A party’s seat share and internal cohesion also positively affect clientelism, but they are not statistically significant.

Table 2.

Results of the effect of religious ideology on clientelism.

4.2. The Mediating Effects of Parties’ Ties with Social Organizations

In Model 3 of Table 3, religious ideology positively affects a party’s ties with social organizations at the significance level of 0.1%, indicating that religious ideology can strengthen a party’s ties with social organizations. Similarly, in Model 4, religious ideology shows a positive effect on the party’s ties with social organizations at the significance level of 0.1%. At the significance level of 1%, a party’s ties with social organizations have a significant positive effect on clientelism. The influence of religious ideology on clientelism decreased from 27.5% in Model 2 to 22.6% in Model 4, indicating that a party’s ties with social organizations mediate the association between religious ideology and clientelism.

Table 3.

Results of the mediating effects of parties’ ties with social organizations.

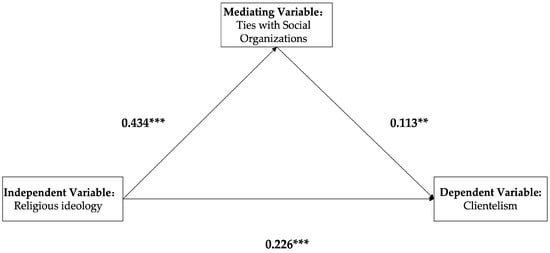

Figure 1 illustrates the impact of the independent variable on the mediator, the effect of the mediator on the dependent variable, and the direct effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable. The direct effect of religious ideology on clientelism is 0.226 at the significance level of 0.1%, suggesting that religious ideology itself positively influences clientelism. The mediating effect of ties with social organizations is 0.049, which transmits 17.8% of the total impacts of a party’s religious ideology on clientelism. Furthermore, the significance of the mediating effect is assessed using the Sobel test. The result indicates that the mediating effect of ties with social organizations is significant (p < 0.001). Therefore, Hypothesis 2, which states that a party’s ties with social organizations mediate the influence of a party’s religious ideology on the use of clientelism, receives statistical support.

Figure 1.

Mediation analysis. ** p < 0.05, and *** p < 0.01.

4.3. Heterogeneity Analysis

4.3.1. Country Heterogeneity: Dominant Religion and Economic Development

First, the dominant religion of a country may have an impact on the results of this study. Unlike most Middle Eastern countries where Islam is the dominant religion, Lebanon and Israel have certain special characteristics among the samples covered in this study. Lebanon has a distinct religious diversity, with 18 officially recognized sects, which mostly belong to Muslims and Christians (Faour 2007). It is the country with the most complex sectarian composition in the MENA, implementing a unique sectarian power-sharing system (Geha 2019). Israel is also a religiously divided country, with more than 70% of the population being Jewish and 18% Muslim. Judaism dominates in Israel, and Jewish religious parties have a strong influence on religious, economic, and diplomatic issues (Cohen and Susser 2000; Porat and Filc 2022). Therefore, this study divides Islamic countries into one group and non-Islamic countries into another group to investigate the influence of religious ideology on clientelism. The sub-sample test results in Table 4 show that the coefficients of religious ideology are both statistically significant in Islamic countries and non-Islamic countries.

Table 4.

Results by dominant religion (Islamic or not).

Secondly, we divide the samples into two groups based on per capita GDP (in 2011 USD) data from the Maddison Project Database, considering the significant variations in economic development in the MENA (Wilson 1995). As shown in Table 5, religious ideology positively impacts clientelism in countries with both low-level and high-level economic development, at the significance levels of 0.1% and 0.01%, respectively. The influence of religious ideology on clientelism is higher in countries with high levels of economic development. A 1% increase in religious ideology leads to an increase in clientelism of 0.163% in lower-income countries, and 0.339% in countries with more developed economies. This may be because, in countries with lower levels of economic development, where the cost of exchanging material benefits for voter support is lower, parties of different ideologies generally employ clientelistic linkage strategies. As a result, religious ideologies have a weaker role in enhancing clientelism.

Table 5.

Results by level of economic development.

4.3.2. Time Heterogeneity: Before and after the 9/11 Terrorist Attack and the Arab Uprisings

Considering the longitudinal space of our study, international and regional circumstances may fluctuate, making religious ideology more or less important to the usage of clientelist linkage. Entering the 21st century, the occurrence of the 9/11 terrorist attack led to an intensified crackdown by the United States on terrorism and extremist Islamic forces. On the one hand, anti-American sentiment in the region and secular parties’s poor governance performance increased the appeal of Islamism to the public (Rabasa et al. 2004; Liu and Li 2014). On the other hand, in the post-9/11 context, religious parties derived from religious movements began to participate in party politics with a more pragmatic attitude, attempting to expand their influence through a combination of ideology and material interest delivery to gain electoral support. This enhanced the positive effects of religious ideology on the use of clientelistic linkage strategies. Therefore, this study uses 2001 as a time dummy variable to identify the impact of the 9/11 terrorist attack. According to Table 6, the estimated coefficient of the 2001 dummy variable is positive at the significance level of 0.01%. The interaction coefficient between the 2001 dummy variable and religious ideology is positive at the significance level of 0.5%, indicating that the influence of religious ideology on clientelism increased after 2001.

Table 6.

Results adding dummy variable for the year 2001.

Similarly, the outbreak of the Arab uprisings in 2011 had far-reaching consequences for countries in the MENA. Although it did not bring about long-term democratic transformation and consolidation, it profoundly impacted party politics in the region (Strom 2017). This study uses a time dummy variable for 2011 to identify the impact of the Arab uprisings. According to Table 7, the coefficient of the time dummy variable is positive but not statistically significant. After adding the interaction term between the time dummy variable and religious ideology, the coefficient of the interaction term is positive at the significance level of 0.5%. In the aftermath of the Arab uprisings, religious parties in the Middle East have become more active in electoral politics under democratic institutions. Consequently, parties’ religious ideology has a greater impact on clientelist tactics.

Table 7.

Results adding dummy variable for the year 2011.

5. Conclusions

Despite the mounting interest in the systematic study of clientelism over the last three decades, few attempts have been made to empirically examine the role of religion in explaining the prevalence of clientelism, especially at the party level. Hence, a lingering question in the literature remains unanswered: how does political parties’ religious ideology impact their clientelist linkages with citizens? This study aimed to fill the gap by examining the association between a party’s religious ideology and clientelist practice in the Middle East and North Africa from 1970 to 2019. To address this research question, we analyzed data from the Varieties of Party Identity and Organization (V-party) database, one of the most comprehensive databases containing cross-national data on political parties in the MENA region.

First, our main finding suggests that political parties with stronger religious ideologies are more likely to use clientelistic tactics in the MENA region. While prior research has pointed out the prevalence of Islamist parties in the MENA adopting clientelistic strategies, it has mainly focused on qualitative case studies (Hamzeh 2001; Clark 2004; Arslantaş and Arslantaş 2023). Our findings provide cross-national empirical evidence of the relationship between religious ideology and clientelism in the region, drawing from a novel database. Second, we found that religious ideology, per se, leads to clientelism. Additionally, our mediation analysis highlighted the mediating role of social organizations in the relationship between a party’s religious ideology and clientelism. This finding is consistent with the literature on clientelism that has paid attention to the role of brokers and the organizations that they represent (Holland and Palmer-Rubin 2015; Garay et al. 2020). Furthermore, additional analysis revealed that the reinforcing effect of religious ideology on clientelism was intensified following the 9/11 terrorist attack and the Arab uprising. Although more research is needed to uncover the mechanism of this, this finding provides additional insight into the relationship between international/regional situations and party politics in the MENA region.

However, this study also has some limitations. First, we measured the religious ideologies of parties using expert survey analysis. Although this is a widely accepted method for measuring political party ideology, future research can employ more direct measurement methods such as political text analysis and opinion surveys to enhance the validity of the conclusions. In addition, in our research, we adopted a broad concept of religious ideology for both the theoretical and empirical analysis. Given that religious ideologies manifest differently in the MENA region, from utilizing Islamism as a legitimating tool to advocating for the imposition of sharia as a social and political agenda, scholars can further refine the measurement of religious ideology and investigate its impacts on clientelism. Second, in the MENA region, some secularist and nationalist political parties are also extensively employing clientelist tactics to reach out to the general population. More detailed case studies in the future can be used to explore the impact of nationalist and secularist ideologies on clientelism in the region. Third, this study focused on the association between religious ideology and clientelism in the context of the MENA. Future research might further study mechanisms linking religious ideology and clientelism in a broader context. A more detailed classification of different religious ideologies could yield new theoretical and empirical insights.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.H.; methodology, S.H.; writing—original draft preparation, S.H.; writing—review and editing, J.W.; supervision, X.Z.; project administration, J.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Albertus, Michael. 2013. Vote Buying with Multiple Distributive Goods. Comparative Political Studies 46: 1082–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslantaş, Düzgün, and Şenol Arslantaş. 2023. How Does Clientelism Foster Electoral Dominance? Evidence from Turkey. Asian Journal of Comparative Politics 7: 559–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arzheimer, Kai, and Elisabeth Carter. 2009. Christian Religiosity and Voting for West European Radical Right Parties. West European Politics 32: 985–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydoğan, Abdullah. 2021. Party Systems and Ideological Cleavages in the Middle East and North Africa. Party Politics 27: 814–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydoğan, Abdullah, and Jonathan B. Slapin. 2013. Left–right Reversed: Parties and Ideology in Modern Turkey. Party Politics 21: 615–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, Reuben M., and David A. Kenny. 1986. The Moderator-Mediator Variable Distinction in Social Psychological Research—Conceptual, Strategic, and Statistical Considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 51: 1173–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit, Kenneth, and Michael Laver. 2006. Party Policy in Modern Democracies. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, Peter L. 1974. Some Second Thoughts on Substantive versus Functional Definitions of Religion. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 13: 125–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blancarte, Roberto. 2023. Populism, Religion, and Secularity in Latin America and Europe: A Comparative Perspective. Working Paper Series of the CASHSS “Multiple Secularities—Beyond the West, Beyond Modernities” 27; Leipzig: Leipzig University. [Google Scholar]

- Brocker, Manfred, and Mirjam Künkler. 2013. Religious Parties: Revisiting the Inclusion-moderation Hypothesis—Introduction. Party Politics 19: 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooke, Steven. 2019. Winning Hearts and Votes: Social Services and the Islamist Political Advantage. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brusco, Valeria, Marcelo Nazareno, and Susan C. Stokes. 2004. Vote Buying in Argentina. Latin American Research Review 39: 66–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustikova, Lenka, and Cristina Corduneanu-Huci. 2011. Clientelism, State Capacity and Economic Development: A Cross-national Study. Paper presented at the Midwest Political Science Association Annual Meeting, Chicago, IL, USA, March 31–April 3. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo, Ernesto, and Maria Victoria Murillo. 2013. When Parties Meet Voters: Assessing Political Linkages through Partisan Networks and Distributive Expectations in Argentina and Chile. Comparative Political Studies 46: 851–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cammett, Melani, and Pauline Jones Luong. 2014. Is There an Islamist Political Advantage? Annual Review of Political Science 17: 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cammett, Melani, and Sukriti Issar. 2010. Bricks and Mortar Clientelism: Sectarianism and the Logics of Welfare Allocation in Lebanon. World Politics 62: 381–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casani, Alfonso. 2020. Cross-ideological Coalitions under Authoritarian Regimes: Islamist-left Collaboration Among Morocco’s Excluded Opposition. Democratization 27: 1183–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavatorta, Francesco, and Fabio Merone. 2013. Moderation through Exclusion? The Journey of the Tunisian Ennahda from Fundamentalist to Conservative Party. Democratization 20: 857–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, Janine. 2004. Social Movement Theory and Patron-clientelism: Islamic Social Institutions and the Middle Class in Egypt, Jordan, and Yemen. Comparative Political Studies 37: 941–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Asher, and Bernard Susser. 2000. Israel and the Politics of Jewish Identity: The Secular-Religious Impasse. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, pp. 98–167. [Google Scholar]

- Cornell, Agnes, and Marcia Grimes. 2022. Brokering Bureaucrats: How Bureaucrats and Civil Society Facilitate Clientelism Where Parties are Weak. Comparative Political Studies 56: 788823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corstange, Daniel, and Erin York. 2021. Clientelism, Constituency Services, and Elections in Muslim Societies. In The Oxford Handbook of Politics in Muslim Societies. Edited by Melani Cammett and Pauline Jones. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 313–22. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, Gary W., and Mathew D. McCubbins. 1986. Electoral Politics as a Redistributive Game. The Journal of Politics 48: 370–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagi, Ihsan. 2008. Islamist Parties and Democracy: Turkey’s AKP in Power. Journal of Democracy 19: 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawisha, Adeed. 2003. Requiem for Arab Nationalism. Middle East Quarterly 10: 25–41. [Google Scholar]

- De Elvira, Laura Ruiz, Christoph H. Schwarz, and Irene Weipert-Fenner. 2018. Clientelism and Patronage in the Middle East and North Africa: Networks of Dependency. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Delehanty, Jack, Penny Edgell, and Evan Stewart. 2019. Christian America? Secularized Evangelical Discourse and the Boundaries of National Belonging. Social Forces 97: 1283–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, Avinash, and John Londregan. 1996. The Determinants of Success of Special Interests in Redistributive Politics. The Journal of Politics 58: 1132–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downs, Anthony. 1959. An Economic Theory of Democracy. New York: Harper and Row. [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim, Emile. 1995. The Elementary Forms of Religious Life. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Düpont, Nils, Yaman Berker Kavasoglu, Anna Lührmann, and Ora John Reuter. 2022. A Global Perspective on Party Organizations. Validating the Varieties of Party Identity and Organization Dataset (V-Party). Electoral Studies 75: 102423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faour, Muhammad A. 2007. Religion, Demography, and Politics in Lebanon. Middle Eastern Studies 43: 909–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, Leandros. 2018. Left-Wing Perspectives on Political Islam: A Mapping Attempt. In Muslims and Capitalism: An Uneasy Relationship? Edited by Béatrice Hendrich. Würzburg: Ergon Verlag, pp. 103–19. [Google Scholar]

- Freedman, Michael. 2020. Vote with Your Rabbi: The Electoral Effects of Religious Institutions in Israel. Electoral Studies 68: 102241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garay, Candelaria, Brian Palmer-Rubin, and Mathias Poertner. 2020. Organizational and Partisan. Brokerage of Social Benefits: Social Policy Linkages in Mexico. World Development 136: 105103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geha, Carmen. 2019. Co-optation, Counter-narratives, and Repression: Protesting Lebanon’s Sectarian Power-sharing Regime. The Middle East Journal 73: 9–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graziano, Luigi. 1973. Patron-Client Relationships in Southern Italy. European Journal of Political Research 1: 3–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, Sharan, Amaney A. Jamal, Tarek Masoud, and Elizabeth R. Nugent. 2019. Poverty and Divine Rewards: The Electoral Advantage of Islamist Political Parties. American Journal of Political Science 63: 859–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürakar, Esra Çeviker. 2016. Politics of Favouritism in Public Procurement in Turkey. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Hamzeh, Ahmed. 2001. Clientalism, Lebanon: Roots and Trends. Middle Eastern Studies 37: 167–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, Nader. 2009. Islam, Secularism, and Liberal Democracy: Toward a Democratic Theory for Muslim Society. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 45–48. [Google Scholar]

- Hicken, Allen. 2011. Clientelism. Annual Review of Political Science 14: 289–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicken, Allen, and Noah L. Nathan. 2020. Clientelism’s Red Herrings: Dead Ends and New Directions in The Study of Nonprogrammatic Politics. Annual Review of Political Science 23: 277–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinnebusch, Raymond A. 2017. Political Parties in MENA: Their Functions and Development. British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies 44: 159–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, Alisha C., and Brian Palmer-Rubin. 2015. Beyond the Machine: Clientelist Brokers and Interest Organizations in Latin America. Comparative Political Studies 48: 1186–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huntington, Samuel P. 1968. Political Order in Changing Societies. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Imai, Kosuke, Luke Keele, and Teppei Yamamoto. 2010. Identification, Inference and Sensitivity Analysis for Causal Mediation Effects. Statistical Science 25: 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keefer, Philip. 2007. Clientelism, Credibility, and the Policy Choices of Young Democracies. American Journal of Political Science 51: 804–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitschelt, Herbert. 2000. Linkages between Citizens and Politicians in Democratic Politics. Comparative Political Studies 336: 845–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitschelt, Herbert, and Steven I. Wilkinson. 2007. Citizen-Politician Linkages: An Introduction. In Patrons, Clients and Policies: Patterns of Democratic Accountability and Political Competition. Edited by Herbert Kitschelt and Steven I. Wilkinson. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 2–49. [Google Scholar]

- Kitschelt, Herbert, and Yi-Ting Wang. 2014. Programmatic Parties and Party Systems: Opportunities and Constraints. In Politics Meets Policies: The Emergence of Programmatic Political Parties. Stockholm: International IDEA, pp. 43–74. [Google Scholar]

- Ko, Kilkon, and Seong-Gin Moon. 2014. The Relationship between Religion and Corruption: Are the Proposed Causal Links Empirically Valid? International Review of Public Administration 19: 44–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, Martin. 1993. Arab Nationalism: Mistaken Identity. Daedalus 122: 171–206. [Google Scholar]

- Laitin, David D. 1978. Religion, Political Culture, and the Weberian Tradition. World Politics 3: 563–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langohr, Vickie. 2001. Of Islamists and Ballot Boxes: Rethinking the Relationship between Islamisms and Electoral Politics. International Journal of Middle East Studies 3: 591–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Zhongmin, and Zhiqiang Li. 2014. The Middle East Unrest and the New Development of Islamic Parties. Journal of Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies 8: 74–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lust, Ellen. 2009. Competitive Clientelism in the Middle East. Journal of Democracy 20: 122–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lührmann, Anna. 2021. Disrupting the Autocratization Sequence: Towards Democratic Resilience. Democratization 28: 1017–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marangudakis, Manussos. 2019. Clientelistic Social Structures and Cultural Orientations. In The Greek Crisis and its Cultural Origins. Edited by Manussos Marangukais. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 81–108. [Google Scholar]

- Markoviti, Margarita, and Lina Molokotos-Liederman. 2017. The Intersections of State, Family and Church in Italy and Greece. In Religion and Welfare in Europe: Gendered and Minority Perspectives. Edited by Lina Molokotos-Liederman, Anders Bäckström and Grace Davie. Bristol: Bristol University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mohseni, Payam, and Clyde Wilcox. 2016. Organizing Politics: Religion and Political Parties in Comparative Perspective. In Routledge Handbook of Religion and Politics, 2nd ed. Edited by Jeffrey Haynes. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 188–211. [Google Scholar]

- Morvaridi, Behrooz. 2013. The Politics of Philanthropy and Welfare Governance: The Case of Turkey. The European Journal of Development Research 2: 305–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichter, Simeon. 2010. Vote Buying or Turnout Buying? Machine Politics and the Secret Ballot. American Political Science Review 102: 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocakli, Feryaz. 2015. Political Entrepreneurs, Clientelism, and Civil Society: Supply-side Politics in Turkey. Democratization 23: 723–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paldam, Martin. 2001. Corruption and Religion Adding to the Economic Model. Kyklos 54: 383413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrikios, Stratos, and Georgios Xezonakis. 2019. Religious Market Structure and Democratic Performance: Clientelism. Electoral Studies 61: 102073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porat, Guy Ben, and Dani Filc. 2022. Remember to Be Jewish: Religious Populism in Israel. Politics and Religion 15: 61–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabasa, Angel, Matthew Waxman, Eric V. Larson, and Cheryl Y. Marcum. 2004. The Muslim World after 9/11. Santa Monica: RAND. [Google Scholar]

- Razi, Hossein G. 1990. Legitimacy, Religion, and Nationalism in the Middle East. American Political Science Review 84: 69–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, Gary, and Pedro Dos Santos. 2013. The Rise (and Frequent Fall) of Evangelical Politicians: Organization, Theology, and Church Politics. Latin American Politics and Society 5: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuter, Ora John. 2022. Why is Party-Based Autocracy More Durable? Examining the Role of Elite Institutions and Mass Organization. Democratization 29: 1014–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, James A., and Thierry Verdier. 2013. The Political Economy of Clientelism. The Scandinavian Journal of Economics 115: 260–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarfati, Yusuf. 2013. Mobilizing Religion in Middle East Politics: A Comparative Study of Israel and Turkey. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 78–136. [Google Scholar]

- Schady, Norbert R. 2000. The Political Economy of Expenditures by the Peruvian Social Fund (FONCODES), 1991–1995. American Political Science Review 94: 289–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilbrack, Kevin. 2013. What Isn’t Religion? The Journal of Religion 93: 291–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, James C. 1972. Patron-Client Politics and Political Change in Southeast Asia. American Political Science Review 66: 189–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shefter, Martin. 1994. Political Parties and the State: The American Historical Experience. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 45–97. [Google Scholar]

- Sommer, Udi, Pazit Ben-Nun Bloom, and Gizem Arikan. 2013. Does Faith Limit Immorality? The Politics of Religion and Corruption. In Religion and Political Change in the Modern World. Edited by Jeffrey Haynes. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 49–75. [Google Scholar]

- Stokes, Susan C. 2005. Perverse Accountability: A Formal Model of Machine Politics with Evidence from Argentina. American Political Science Review 99: 315–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokes, Susan C., Thad Dunning, and Marcelo Nazareno. 2013. Brokers, Voters, and Clientelism: The Puzzle of Distributive Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 78–131. [Google Scholar]

- Strom, Lise. 2017. Parties and Party System Change. In Political Change in the Middle East and North Africa: After the Arab Spring. Edited by Inmaculada Szmolka. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, pp. 63–88. [Google Scholar]

- Tessler, Mark. 2011. The Origins of Political Support for Islamist Movements: A Political Economy Approach. In Public Opinion in the Middle East: Survey Research and the Political Orientations of Ordinary Citizens. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, pp. 25–55. [Google Scholar]

- Tusalem, Rollin F. 2015. State Regulation of Religion and the Quality of Governance. Politics & Policy 43: 94–141. [Google Scholar]

- Tzelgov, Eitan, and Yi-Ting Wang. 2016. Party Ideology and Clientelistic Linkage. Electoral Studies 44: 374–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walzer, Michael. 2015. Islamism and the Left. Dissent 6: 107–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weghorst, Keith R., and Staffan I. Lindberg. 2013. What Drives the Swing Voter in Africa? American Journal of Political Science 57: 717–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegner, Eva, and Francesco Cavatorta. 2018. Revisiting the Islamist–Secular Divide: Parties and Voters in the Arab World. International Political Science Review 40: 558–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Rhys H. 1996. Religion as Political Resource: Culture or Ideology? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 35: 368–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, Rodney. 1995. Economic Development in the Middle East. New York: Routledge, pp. 27–49. [Google Scholar]

- Woodberry, Robert D., and Christian S. Smith. 1998. Fundamentalism et al.: Conservative Protestants in America. Annual Review of Sociology 2: 25–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, Ihsan, Mehmet Efe Caman, and Galib Bashirov. 2020. How an Islamist Party Managed to Legitimate Its Authoritarianization in the Eyes of the Secularist Opposition: The Case of Turkey. Democratization 2: 265–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, Kerem, and Herbert Kitschelt. 2020. Analytical Perspectives on Varieties of Clientelism. Democratization 27: 20–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).