Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage in Vâlcea County, South-West Oltenia Region: Motivations, Belief and Tourists’ Perceptions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methodology

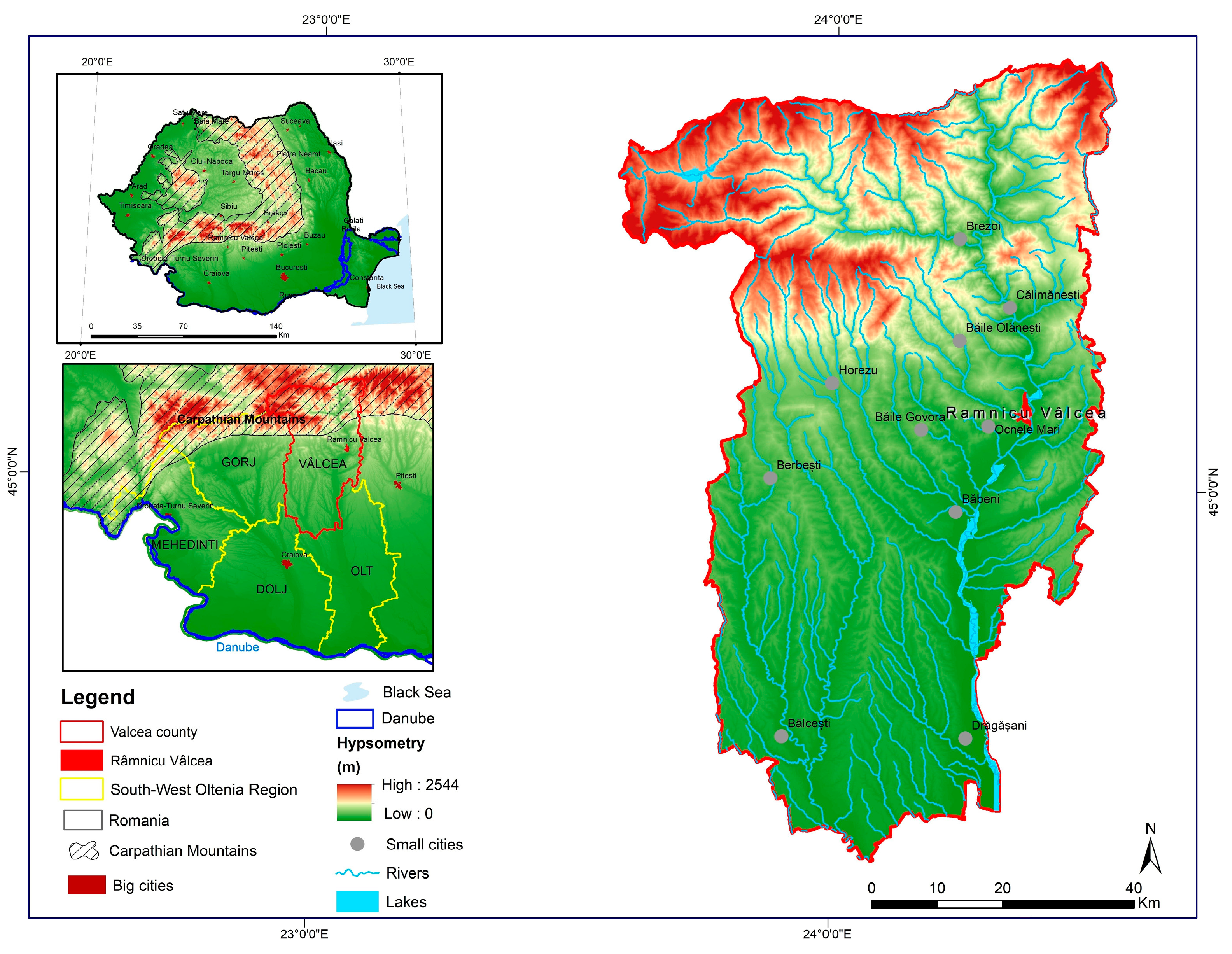

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Data Sources

3.3. Research Hypotheses

3.4. Research Questions

4. Results

4.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics of the Stakeholders (Domestic Tourists—Romanians)

- 12% of respondents were students.

- 56% of respondents were employed.

- 31% of respondents were retirees.

- 1% of respondents were unemployed.

4.2. Questionnaire Results

- R (Correlation Coefficient): It indicated a very weak correlation (0.012) between the age category and the duration of visits. The relationship between these two variables was not significant.

- R Square (Coefficient of Determination): At 0.000, it suggested that the age category did not significantly explain the variation in the duration of visits to religious sites.

- Adjusted R Square: With a value of −0.010, it indicated a poor model performance, considering the number of independent variables.

- Std. Error of the Estimate: It measured the data dispersion around the regression line—0.595, in this case.

- Change Statistics: R square change and F change did not indicate a significant improvement in the model with the introduction of the age category.

- Significance (Sig. F Change): The p-value associated with F change was 0.907, suggesting that adding the age category did not bring a significant improvement to the model.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- I.

- Sample group data.

- 1.

- Your gender?MaleFemale

- 2.

- Which age category do you fit into?18–25 years26–35 years36–45 years46–55 yearsOver 55 years

- 3.

- Your residence?RuralUrban

- 4.

- Level of education?High schoolUniversity

- 5.

- Your occupation?StudentEmployeeUnemployedRetireeOthers (please specify) …

- II.

- Evaluation of the aspects related in religious tourism and pilgrimage in Vâlcea County.

- 6.

- What type of trip did you choose?IndividuallyIn an organized group

- 7.

- What means of transport did you use?Own carBusTrainOther (please specify) …

- 8.

- What is the frequency of your visits for purposes of religious tourism and pilgrimage to Vâlcea?Once a yearTwo or more timesNever

- 9.

- How long was the visit?One dayA weekendMore than two days

- 10.

- Who accompanied you in visiting places of worship?Family membersFriendshipOther (please specify) …

- 11.

- Which places of worship (churches and monasteries) have you visited in Vâlcea County?…………….

- 12.

- Have you used guided tours for visiting places of worship?YesNo

- 13.

- What sources of information/documentation did you used for religious tourism and pilgrimage in Vâlcea County?MediaTravel agenciesThe tourism fairFamily/relatives/friendsThe churchLeaflets/newspapers/brochures

- 14.

- What is the main reason behind your visits to religious settlements in Vâlcea County?For prayerFor the history of church artOut of curiosity and a desire to exploreVisiting places of worshipFor the sacred atmosphereThe desire to be close to faith

- 15.

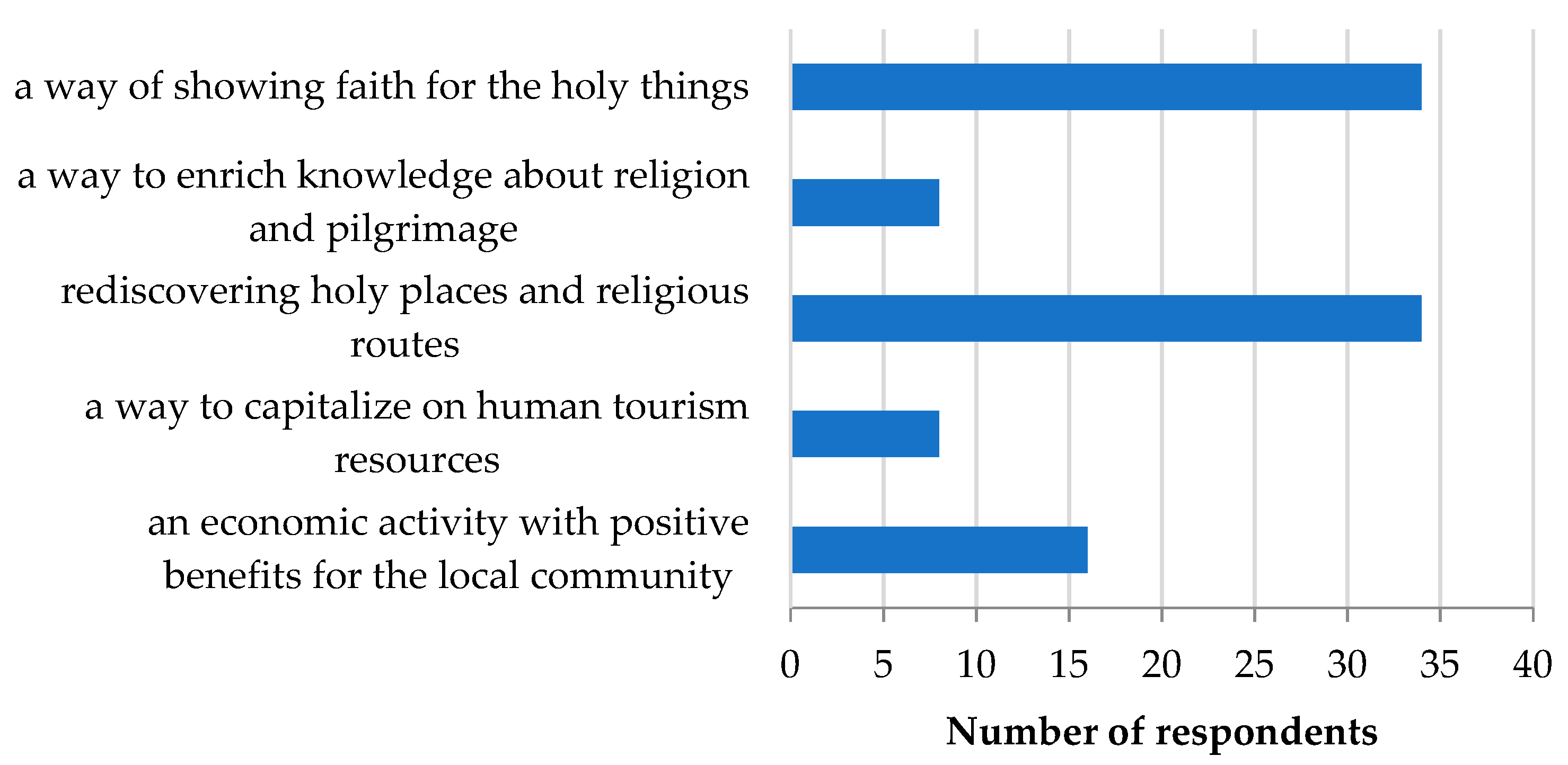

- The notion of “religious tourism and pilgrimage” in your view represents?A way to capitalize on human tourism resourcesRediscovering holy places and religious routesAn economic activity with positive benefits on the local communityA way of manifesting faith for holy thingsA way to enrich knowledge about religion and pilgrimage

- 16.

- On a scale from 1 to 5, how important are the religious settlements in Vâlcea for visitors?

| 1 | . |

References

- Abad-Galzacorta, Marina, Basagaitz Guereño-Omil, Amaia Makua, Ricard Santomà, and José Luis Iriberri. 2016. Pilgrimage as tourism experience: The case of the Ignatian Way. International Journal of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage 4: 48–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbate, Costanza Scaffidi, and Santo Di Nuovo. 2013. Motivation and personality traits for choosing religious tourism. A research on the case of Medjugorje. Current Issues in Tourism 16: 501–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksöz, Emre O., and Gönül Çay. 2022. Investigation of perceived service quality, destination image and revisit intention in museums by demographic variables. GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites 43: 1138–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baias, Ștefan, Gozner Maria, Herman Grigore Vasile, and Măduța Florin Miron. 2015. Typology of wooden churches in the drainage basins of Mureș and Arieș, Alba County. Annals of the University of Oradea, Geography Series 25: 221–33. Available online: https://geografie-uoradea.ro/Reviste/Anale/Art/2015-2/9.AUOG_696_Baias.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2023).

- Battour, Mohamed M., Moustafa M. Battor, and Ismail Mohd. 2012. The mediating role of tourist satisfaction: A study of Muslim tourists in Malaysia. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 29: 279–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beard, Jacob G., and Mounir G. Ragheb. 1983. Measuring leisure motivation. Journal of Leisure Research 15: 219–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogan, Elena, Andreea-Loreta Cercleux, and Dana Maria (Oprea) Constantin. 2019. The role of religious and pilgrimage tourism in developing and promoting the urban tourism in Bucharest. Quality-Access to Success 20: 94–101. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Elena-Bogan/publication/332543588_THE_ROLE_OF_RELIGIOUS_AND_PILGRIMAGE_TOURISM_IN_DEVELOPING_AND_PROMOTING_THE_URBAN_TOURISM_IN_BUCHAREST/links/5cbb3d2c4585156cd7a7124a/THE-ROLE-OF-RELIGIOUS-AND-PILGRIMAGE-TOURISM-IN-DEVELOPING-AND-PROMOTING-THE-URBAN-TOURISM-IN-BUCHAREST.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2023).

- Bogan, Elena, Roangheș-Mureanu Ana-Maria, Constantin (Oprea) Dana-Maria, Grigore Elena, Gabor Sebastian, and Dîrloman Gabriela. 2017. The Religious Tourism—An Opportunity of Promoting and Developing the Tourism in the Vâlcea Subcarpathians. Academic Journal of Economic Studies 3: 106–11. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Elena-Bogan/publication/324993785_The_Religious_Tourism-An_Opportunity_of_Promoting_and_Developing_the_Tourism_in_the_Valcea_Subcarpathians/links/5af09bd6aca272bf4251f1f3/The-Religious-Tourism-An-Opportunity-of-Promoting-and-Developing-the-Tourism-in-the-Valcea-Subcarpathians.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2023).

- Bratianu, Constantin, and Ruxandra Bejinaru. 2019. The Theory of Knowledge Fields: A Thermodynamics Approach. Systems 7: 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratianu, Constantin, and Ruxandra Bejinaru. 2020. Knowledge dynamics: A thermodynamics approach. Kybernetes 49: 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caciora, Tudor, Herman Grigore Vasile, Ilieș Alexandru, Baias Ștefan, Ilieș Dorina Camelia, Josan Ioana, and Hodor Nicolaie. 2021. The Use of Virtual Reality to Promote Sustainable Tourism: A Case Study of Wooden Churches Historical Monuments from Romania. Remote Sensing 13: 1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CETUR, and SA Xacobeo. 2007. ObservatorioEstadístico do Camiño de Santiago 2007, 2008, 2009 e 2010. Santiago de Compostela: Universidade de Santiago de Compostela, Xunta de Galicia y Centro de Estudios Turísticos. [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabarty, Premangshu, and Sanjoy Kumar Sadhukhan. 2020. Destination image for pilgrimage and tourism: A study in Mount Kailash region of Tibet. Folia Geographical 62: 71–86. Available online: https://www.unipo.sk/public/media/37070/567-DESTINATION%20IMAGE%20FOR%20PILGRIMAGE%20AND%20TOURISM%20-%20A%20STUDY%20IN%20MOUNT%20KAILASH%20REGION%20OF%20TIBET.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2023).

- COE-CR. 2023. Explore all Routes by Theme. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/cultural-routes/by-theme (accessed on 23 November 2023).

- Cohen, Erik, and Scott A. Cohen. 2015. A mobilities approach to tourism from emerging world regions. Current Issues in Tourism 18: 11–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, Simon, and John Eade, eds. 2004. Reframing Pilgrimage. Cultures in Motion. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Collins-Kreiner, Noga. 2018. Pilgrimage-Tourism: Common Themes in Different Religions. International Journal of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage 6: 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crăciun, Andreea M., Dezsi Ștefan, Pop Florin, and Cecilia Pintea. 2022. Rural Tourism—Viable Alternatives for Preserving Local Specificity and Sustainable Socio-Economic Development: Case Study—“Valley of the Kings” (Gurghiului Valley, Mureș County, Romania). Sustainability 14: 16295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crețan, Remus, O’brien Thomas, Văran Ţenche, and Timofte Fabian. 2023. Legacies of Displacement from the Iron Gates Hydroelectric Project. Journal of Settlements and Spatial Planning 14: 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cretu, Carmen-Mihaela, Turtureanu Anca-Gabriela, Sirbu Carmen-Gabriela, Chitu Florentina, Marinescu Emanuel Ştefan, Talaghir Laurențiu-Gabriel, and Robu Daniela Monica. 2021. Tourists’ Perceptions Regarding Traveling for Recreational or Leisure Purposes in Times of Health Crisis. Sustainability 13: 8405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, John L., and Stacey L. McKay. 1997. Motives of visitors attending festival events. Annals of Tourism Research 24: 425–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deac, Luminița Anca, Herman Grigore Vasile, Gozner Maria, Bulz Gheorghe Codruț, and Boc Emilia. 2023. Relationship between Population and Ethno-Cultural Heritage—Case Study: Crișana, Romania. Sustainability 15: 9055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drule, Alexandra M., Alexandru Chiş, Mihai F. Băcilă, and Raluca Ciornea. 2012. A new perspective of non-religious motivations of visitors to sacred sites: Evidence from Romania. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 62: 431–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitraşcu, Monica, Dragotă Carmen Sofia, Grigorescu Ines, Dumitraşcu Costin, and Vlăduţ Alina. 2017. Key pluvial parameters in assessing rainfall erosivity in the south-west development region, Romania. Journal of Earth System Science 126: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyas, Dee. 2020. Pilgrimage: Not All Rucksack and Hiking Boots. Church Times. Available online: https://www.churchtimes.co.uk/articles/2020/23-october/features/features/pilgrimage-not-all-rucksack-and-hiking-boots (accessed on 21 January 2024).

- Eade, John. 2020. ‘What is going on here?’Gazing, Knowledge and the Body at a Pilgrimage Shrine. Journeys 21: 19–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhosiny, Said Mohamed, Thowayeb H. Hassan, Ioana Josan, Amany E. Salem, Mostafa A. Abdelmoaty, Grigore Vasile Herman, Jan Andrzej Wendt, Bekzot Janzakov, Hassan Marzok Elsayed Mahmoud, and Magdy Sayed Abuelnasr. 2023. Oradea’s Cultural Event Management: The Impact of the ‘Night of the Museums’ on Tourist Perception and Destination Brand Identity. Sustainability 15: 15330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen, Steven. 2012. Slovin’s Formula Sampling Techniques. Available online: https://sciencing.com/how-6188297-do-determine-audit-sample-size-.html (accessed on 23 November 2023).

- Fatima, Ummara, Naeem Sundas, and Rasool Farhat. 2016. The relationship between religious tourism and individual’s perceptions (a case study of hazrat data Ghanj Bakhsh’s shrine). International Journal of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage 4: 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, Carlos, Pimenta Elsa, Gonçalves Francisco, and Rachão Susana. 2012. A new research approach for religious tourism: The case study of the Portuguese route to Santiago. International Journal of Tourism Policy 4: 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, Nancy. 2002. Santiagopilger Unterwegs und Danach. Volkach/Main: Manfred Zentgraf. [Google Scholar]

- García-Buades, M. Esther, García-Sastre Mariá Antonia, and Alemany-Hormaeche Margarita. 2022. Effects of overtourism, local government, and tourist behavior on residents’ perceptions in Alcúdia (Majorca, Spain). Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism 39: 100499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzola, Patrizia, Daniela Grechi, Enrica Pavione, and Paola Ossola. 2019. “Albergo diffuso” model for the analysis of customer satisfaction. European Scientific Journal 25: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzola, Patrizia, Enrica Pavione, Daniele Grechi, and Paola Ossola. 2018. Cycle tourism as a driver for the sustainable development of little-known or remote territories: The experience of the Apennine regions of Northern Italy. Sustainability 10: 1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giușcă, Mădălina-Cristina. 2020. Religious tourism and pilgrimage at Prislop Monastery, Romania: Motivations, faith and perceptions. Human Geographies—Journal of Studies and Research in Human Geography 14: 149–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giușcă, Mădălina-Cristina, Gheorghilaș Aurel, and Dumitrache Liliana. 2018. Assessment of the religious-tourism potential in Romania. Human Geographies—Journal of Studies and Research in Human Geography 12: 225–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-García, Rόmulo Jacoba, Mártínez-Rico Gabriel, Bañuls-Lapuerta Francesc, and Calabuig Ferran. 2022. Residents’ Perception of the Impact of Sports Tourism on Sustainable Social Development. Sustainability 14: 1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grechi, Daniela, Ossola Paola, and Pavione Enrica. 2015. Expo 2015 and development of slow tourism: Are the tourism product clubs in the territory of Varese successful. In Toulon-Verona Conference” Excellence in Services. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Daniele-Grechi-3/publication/311510244_EXPO_2015_and_development_of_slow_tourism_Are_the_tourism_products_clubs_in_the_territory_of_Varese_successful/links/5c474284a6fdccd6b5c04502/EXPO-2015-and-development-of-slow-tourism-Are-the-tourism-products-clubs-in-the-territory-of-Varese-successful.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2023).

- Haab, Barbara. 1998. Weg und Wandlung. Zur Spiritualität heutiger Jakobspilger und -pilgerinnen. Ph.D. dissertation, Zürich University, Freiburg, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, Tahani, Carvache-Franco Mauricio, Carvache-Franco Wilmer, and Carvache-Franco Orly. 2022. Segmentation of Religious Tourism by Motivations: A Study of the Pilgrimage to the City of Mecca. Sustainability 14: 7861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, Grigore Vasile, Banto Norbert, Caciora Tudor, Ungureanu Mihaela, Furdui Sorin, Garai Lavinia Daiana, and Grama Vasile. 2021. The Perception of Bihor Mountain Tourist Destination from Romania. Geographia Polonica. 94: 573–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, Grigore Vasile, Grama Vasile, Sonko Seedou Mukthar, Boc Emilia, Băican Diana, Garai Lavinia Daiana, Blaga Lucian, Josan Ioana, Caciora Tudor, Gruia Karina Andreea, and et al. 2020. Online information premise in the development of Bihor tourist destination, Romania. Folia Geographica 62: 21–34. Available online: https://www.unipo.sk/public/media/35123/553-ONLINE%20INFORMATION%20PREMISE%20IN%20THE%20DEVELOPMENT%20ONLINE%20INFORMATION%20PREMISE%20IN%20THE%20DEVELOPMENT.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2023).

- Herman, Grigore Vasile, Jan A. Wendt, Răzvan Dumbravă, and Maria Gozner. 2019. The role and importance of promotion centers in creating the image of tourist destination: Romania. Geographia Polonica 92: 443–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, Grigore Vasile, Tătar Corina Florina, Stașac Marcu Simion, and Cosman Victor Lucian. 2024. Exploring the Relationship between Tourist Perception and Motivation at a Museum Attraction. Sustainability 16: 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, Lee Tsung, Jan Fee-Hauh, and Lin Yi Hsien. 2020. How authentic experience affects traditional religious tourism development: Evidence from the Dajia Mazu Pilgrimage, Taiwan. Journal of Travel Research 60: 1140–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, Yi-Tung, and Yuan-Ming Hsu. 2017. A Case Study of a Pilgrim’s Spiritual Experiences: Taking One’s Pilgrimage to the Thekchog Namdrol Shedrub Dargeyling Temple in South India as an Example. Body Culture Journal 25: 141–64. Available online: https://www.airitilibrary.com/Common/Click_DOI?DOI=10.6782/BCJ.201712(25).0006 (accessed on 23 November 2023).

- Ilies, Dorina Camelia, Grigore Vasile Herman, Bahodirhon Safarov, Alexandru Ilies, Lucian Blaga, Tudor Caciora, Ana Cornelia Peres, Vasile Grama, Sigit Widodo Bambang, Telesphore Brou, and et al. 2023. Indoor Air Quality Perception in Built Cultural Heritage in Times of Climate Change. Sustainability 15: 8284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilieș, Dorina Camelia, Oneț Aurelia, Marcu Florin Mihai, Gaceu Ovidiu Răzvan, Timar Adrian, Baias Ștefan, Ilieș Alexandru, Grigore Vasile Herman, Costea Monica, Țepelea Marius, and et al. 2018. Investigation on air quality in the historic wooden church in Oradea City, Romania. Environmental Engineering and Management Journal (EEMJ) 17: 2731–39. Available online: http://www.eemj.icpm.tuiasi.ro/pdfs/vol17/full/no11/23_294_Ilies_17.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2023).

- Ilieș, Alexandru, Jan A. Wendt, Dorina Camelia Ilieș, Grigore Vasile Herman, Marin Ilieș, and Anca Luminița Deac. 2016. The patrimony of wooden churches, built between 1531 and 2015, in the Land of Maramureș, Romania. Journal of Maps 12: 597–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Im, Yunwoo, and ChungAh Kim. 2022. A study on hotel employees’ perceptions of the fourth industrial technology. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 51: 559–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institutul Național de Statistică, TEMPO. 2023. Available online: http://statistici.insse.ro:8077/tempo-online/ (accessed on 23 November 2023).

- Kamath, Vasanth, Ribeiro Manuel Alector, Woosnam Kyle Maurice, Mallya Jyothi, and Kamath Giridhar. 2023. Determinants of visitors’ loyalty to religious sacred event places: A multigroup measurement invariance model. Journal of Travel Research 62: 176–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmi, Enrica. 2020. Heritage and new communication technologies: Development perspectives on the basis of the Via Francigena experience. In “Preceedings” of the Heritage, Tourism and Hospitality International Conference HTHIC2020 “Living Heritage and Sustainable Tourism”. Edited by L. Cantoni, S. De Ascaniis and K. Elgin-Nijuis. Lugano: Università della Svizzera Italiana, pp. 43–63. [Google Scholar]

- Light, Duncat, Lupu Cristina, Creţan Remus, and Chapman Anya. 2024. Unconventional entrepreneurs: The non-economic motives of souvenir sellers. Tourism Review. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay Smith, Gabrielle, Lauren Banting, Rochelle Eime, Grant O’Sullivan, and Jannique G. Z. van Uffelen. 2017. Theassociation between social support and physical activity in older adults: A systematic review. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 14: 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liro, Justyna. 2021. Visitors’ motivations and behaviours at pilgrimage centres: Push and pull perspectives. Journal of Heritage Tourism 16: 79–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liro, Justyna, Izabela Sołjan, and Elżbieta Bilska-Wodecka. 2018a. Spatial changes of pilgrimage centers in pilgrimage studies–review and contribution to future research. International Journal of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage 6: 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liro, Justyna, Izabela Sołjan, and Elżbieta Bilska-Wodecka. 2018b. Visitors’ diversified motivations and behavior–the case of the pilgrimage center in Krakow (Poland). Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change 16: 416–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lois González, Rubén Camilo. 2013. The Camino de Santiago and its contemporary renewal: Pilgrims, tourists and territorial identities. Culture and Religion: An Interdisciplinary Journal 14: 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lois González, Rubén Camilo, John Eadeb, and Adolfo Carballo-Penelac. 2021. The socio-economic impact of cultural itineraries: The Way of Saint James and other pilgramage routes. Revista Galega de Economía 30: 7938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lois-González, Rubén C., and Xosé M. Santos. 2015. Tourists and Pilgrims on their Way to Santiago. Motives, Caminos and Final Destinations. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change 13: 149–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, Cárdenas Rogelio. 2010. Tourisme Spirituel. Le Mystique Comme Patrimoine Touristique. Karthala. pp. 221–39. Available online: http://repositorio.cualtos.udg.mx:8080/jspui/handle/123456789/383 (accessed on 23 November 2023).

- Mazilu, Mirela, Niță Amalia, Drăguleasa Ionuț-Adrian, and Mititelu-Ionuș Oana. 2023. Fostering Urban Destination Prosperity through Post COVID-19 Sustainable Tourism in Craiova, Romania. Sustainability 15: 13106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesaritou, Evgenia, Coleman Simon, and Eade John. 2020. Introduction: Knowledge, ignorance, and pilgrimage. Journeys 21: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira Gregori, Pedro Ernesto, Román Concepciόn, and Martín Juan Carlos. 2022. Residents’ perception of a mature and mass tourism destination: The determinant factors in Gran Canaria. Tourism Economics 28: 515–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscarelli, Rossella, Lopez Lucrezia, and Lois González Rubén Camilo. 2020. Who Is Interested in Developing the Way of Saint James? The Pilgrimage from Faith to Tourism. Religions 11: 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najib, Mukhamad, Sumardi Retno Santi, Nurlaela Siti, and Fahma Fahma. 2020. Determinant factors of Muslim Tourist motivation and attitude in Indonesia and Malaysia. Geo Journal of Tourism and Geosites 31: 936–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neacșu, Nicolae, Băltărețu Andreaa, Neacșu Monica, and Drăghilă Marcela. 2009. Resurse și destinații turistice—Interne și internaționale. Bucharest: Editura Universitară. [Google Scholar]

- Niță, Amalia. 2021. Rethinking Lynch’s “The Image of the City” Model in the Context of Urban Fabric Dynamics. Case Study: Craiova, Romania. Journal of Settlements & Spatial Planning, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyaupane, Gyan P., Dallen J. Timothy, and Surya Poudel. 2015. Understanding tourists in religious destinations: A social distance perspective. Tourism Management 48: 343–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, Daniel H., and Dallen J. Timothy. 2006. Tourism and Religious Journeys. In Tourism, Religion and Spiritual Journeys. Edited by Daniel Olsen and Dallen Timothy. London: Routledge, pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oviedo, Lluis, Scarlett de Courcier, and Miguel Farias. 2014. Rise of Pilgrims on the Camino to Santiago: Sign of Change or Religious Revival? Review of Religious Research 56: 433–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmowski, Tadeusz, and Lucyna Przybylska. 2022. The Functions of the Fishermen’s Sea Pilgrimage to St Peter and St Paul’s Church Fair in the Town of Puck. Religions 13: 1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, Philip L. 2005. Tourist Behaviour: Themes and Conceptual Schemes. Bristol: Channel View Publications, vol. 27. [Google Scholar]

- Perdue, Richard R. 1985. Segmenting state travel information inquirers by timing of the destination decision and previous experience. Journal of Travel Research 23: 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, Liliana, Nita Amalia, and Iordache Costela. 2020. Place identity, urban tourism and heritage interpretation: A case study of Craiova, Romania. Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies 22: 494–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, Liliana, Vîlcea Cristiana, and Niță Amalia. 2022. Reclaiming the Face of the City. Can Third-Places Change Place Attachment? Craiova as Case Study. In Preserving and Constructing Place Attachment in Europe. Cham: Springer International Publishing, vol. 131, pp. 257–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prima, Stefanus. 2022. Study of Perception of the Importance of English Language Skills among Indonesian Hotel Employees. J-SHMIC Journal of English for Academic 9: 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purwoko, Agus, Nurrochmat Dodik Ridho, Ekayani Meti, Rijal Syamsu, and Garura Herlina Leontin. 2022. Examining the Economic Value of Tourism and Visitor Preferences: A Portrait of Sustainability Ecotourism in the Tangkahan Protection Area, Gunung Leuser National Park, North Sumatra, Indonesia. Sustainability 14: 8272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, Razaq, and Nigel D. Morpeth. 2007. İntroduction: Establishing Linkages between Religious Travell and Tourism. In Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage Management. Wallingford: Cabi, pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, Razaq, Griffin Kevin, and Blackwell Robert. 2015. Motivations for Religious Tourism, Pilgrimage, Festivals and Events. In Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage Management: An International Perspective, 2nd ed. Edited by Razaq Raj and Griffin Kevin. Wallingford: CABI, pp. 103–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, Haywantee, and Muzaffer S. Uysal. 2011. The effects of perceived authenticity, information search behaviour, motivation and destination imagery on cultural behavioural intentions of tourists. Current Issues in Tourism 14: 537–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinschede, Gisbert. 1992. Forms of Religious Tourism. Annals of Tourism Research 19: 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robina Ramírez, Rafael, and Manuel Pulido Fernández. 2018. Religious experiences of travellers visiting the Royal Monastery of Santa María de Guadalupe (Spain). Sustainability 10: 1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanelli, Mauro, Patrizia Gazzola, Daniela Grechi, and Francesca Pollice. 2021. Towards a sustainability-oriented religious tourism. Systems Research and Behavioral Science 38: 386–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, William S. 2009. Transformative Pilgrimage. Journal of Spirituality in Mental Health 11: 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuo, Yeh (Sam) Shih, Chris Ryan, and Ge (Maggie) Liu. 2009. Taoism, temples and tourists: The case of Mazu pilgrimage tourism. Tourism Management 30: 581–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, Maria Fátima, and Isabel Martins Borges. 2019. Religious Tourism and Pilgrimages in the Central Portuguese way to Santiago and the Issue of Accessibility. In Handbook of Research on Socio-Economic Impacts of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage. Hershey: IGI Global, pp. 375–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, Matos Fátima, Braga José Luis, Otón Miguel Pazos, and Borges Isabel. 2023. Pilgrimages on the Portuguese Way to Santiago de Compostela: Evolution and Motivations. Religions 14: 1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorea, Daniela, Defta Monica, and Popescu Ionuț Mihai. 2023. Journeys to Significant Places in Orthodoxy as a Source of Sustainable Local Development in Romania. Sustainability 15: 5693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiyono, S. 2017. Metode Penelitian Kuantitatif, Kualitatif dan R&D. Bandung: Penerbit Alfabeta. [Google Scholar]

- Tejada, Jeffry J., and Raymond B. Punzalan Joyce. 2012. On the Misuse of Slovin’s Formula. The Philippine Statistician 61: 129–36. Available online: https://www.psai.ph/docs/publications/tps/tps_2012_61_1_9.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2023).

- Telbisz, Tamás, Mari Lászlό, Gessert Alena, Dická Janetta Nestorová, and Gruber Péter. 2022. Attitudes and Perceptions of Local Residents and Tourists—A Comparative Study of the Twin National Parks of Aggtelek (Hungary) and Slovak Karst (Slovakia). Acta Carsologica 51: 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terzidou, Matina, Caroline Scarles, and Mark N. K. Saunders. 2018. The complexities of religious tourism motivations: Sacred places, vows and visions. Annals of Tourism Research 70: 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timothy, Dallen L., and Stephen W. Boyd. 2006. Heritage Tourism in the 21st Century: Valued Traditions and New Perspectives. Journal of Heritage Tourism 1: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, Serena, and Vincent Wing Sun Tung. 2022. Measuring the valence and intensity of residents’ behaviors in host–tourist interactions: Implications for destination image and destination competitiveness. Journal of Travel Research 61: 565–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. 2003. Text of the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. October 17. Available online: https://ich.unesco.org/en/convention (accessed on 23 November 2023).

- UNESCO, and WHC. 1994. Report on the Expert Meeting on Routes as a Part of our Cultural Heritage. December 17. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/archive/routes94.htm (accessed on 23 November 2023).

- van Iwaarden, Marc, and Jeroen Nawijn. 2024. Eudaimonic benefits of tourism: The pilgrimage experience. Tourism Recreation Research 49: 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vareiro, Laurentina, Sousa Bruno Barbosa, and Silva Sόnia Sousa. 2021. The importance of museums in the tourist development and the motivations of their visitors: An analysis of the Costume Museum in Viana do Castelo. Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development 11: 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vătămănescu, Elena-Mădălina, Vlad-Andrei Alexandru, Violeta Mihaela Dincă, and Bogdan Gabriel Nistoreanu. 2018. Vătămănescu, Elena-Mădălina, Vlad-Andrei Alexandru, Violeta Mihaela Dincă, and Bogdan Gabriel Nistoreanu. 2018. A Social Systems Approach to Self-assessed Health and Its Determinants in the Digital Era. Systems Research and Behavioral Science 35: 357–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlăduț, Alina Ștefania, Licurici Mihaela, and Burada Cristina Doina. 2023. Viticulture in Oltenia region (Romania) in the new climatic context. Theoretical and Applied Climatology 154: 179–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlăduț, Alina, Avram Sorin, and Popescu Liliana. 2011. Capitalization of tourism resources in Oltenia (Romania). Annals of the University of Craiova. Series Geography 14: 167–80. Available online: https://analegeo.ro/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/14-Alina-VLADUT-Sorin-AVRAM-Liliana-POPESCU.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2023).

- Wang, Dan, Ching-Cheng Shen, Tzuhui Angie Tseng, and Ching-Yi Lai. 2024. What Is the Most Influential Authenticity of Beliefs, Places, or Actions on the Pilgrimage Tourism Destination Attachment? Sustainability 16: 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Kuo-Yan, Azilah Kasim, and Jing Yu. 2020. Religious Festival Marketing: Distinguishing between devout believers and tourists. Religions 11: 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidenfeld, Adi. 2006. Religious needs in the hospitality industry. Tourism and Hospitality Research 6: 143–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worthington, E. L., Jr., Nathaniel G. Wade, Terry L. Hight, Jennifer S. Ripley, Michael E. McCullough, Jack W. Berry, Michelle M. Schmitt, James T. Berry, Kevin H. Bursley, and Lynn O’Connor. 2003. The Religious Commitment Inventory—10: Development, refinement, and validation of a brief scale for research and counseling. Journal of Counseling Psychology 50: 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Aiping, and Wenwen Jia. 2021. The influence of eliciting awe on pro-environmental behavior of tourist in religious tourism. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 48: 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamani-Farahani, Hamira, and Riyad Eid. 2016. Muslim world: A study of tourism & pilgrimage among OIC Member States. Tourism Management Perspectives 19: 144–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Xin, Xiaoqian Lu, Xiaolan Zhou, and Chaohai Shen. 2022. Reconsidering Tourism Destination Images by Exploring Similarities between Travelogue Texts and Photographs. ISPRS International Journal Geo-Information 11: 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number | Hypotheses |

|---|---|

| H1 | There is a significant correlation between the gender of respondents and the type of travel chosen for religious tourism and pilgrimage in Vâlcea County |

| H2 | The age categories of participants influence the duration of their visits to religious sites in Vâlcea County |

| H3 | The level of education completed is associated with the frequency of visits for religious tourism and pilgrimage in Vâlcea County |

| H4 | There is a positive association between the occupation of respondents and the means of transportation used |

| H5 | There is a significant correlation between the respondents’ place of origin and the presence of accompanying individuals during their visits for religious tourism and pilgrimage in Vâlcea County |

| H6 | There is an association between the level of education of respondents and participation in guided tours within religious tourism and pilgrimage experiences in Vâlcea County |

| H7 | There is a positive correlation between the sources of information used for religious tourism and pilgrimage and the main purpose of visits |

| H8 | There is a relationship between an individual’s perception of religious tourism and the importance attributed to religious establishments in the context of religious tourism and pilgrimage |

| Hypotheses | Variables | The Statistical Method Used |

|---|---|---|

| H1. | Gender Forms of tourism | Correlation Analysis |

| H2. | Age category Duration of the visit | Regression Analysis |

| H3. | Educational level Frequency of visits | Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) |

| H4. | Occupation Means of transportation | Chi-square Test |

| H5. | Place of origin Accompanying individuals | Correlation Analysis |

| H6. | Education level Guided tours | t-Test |

| H7. | Information sources Main purpose of visits | Correlation Analysis |

| H8. | Perception of religious tourism Importance of establishments | Regression Analysis |

| Gender | Pearson Correlation Sig. (two-tailed) N | 1 100 | −0.116 0.251 100 |

| Gender | Type of travel | ||

| Type of travel | Pearson Correlation Sig. (two-tailed) N | −0.116 0.251 100 | 1 100 |

| Model | R | R Square | Adjusted R Square | Std. Error of the Estimate | Change Statistics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R Square Change | F Change | df1 | df2 | R Square Change | F Change | df1 | df2 | Sig. F Change | |

| 1 | 0.012 (a) | 0.000 | −0.010 | 0.595 | 0.000 | 0.014 | 1 | 98 | 0.907 |

| Model | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Regression | 0.005 | 1 | 0.005 | 0.014 | 0.907 (a) |

| Residual | 34.745 | 98 | 0.355 | |||

| Total | 34.750 | 99 | ||||

| Dependent Variable: Duration of the visit | ||||||

| Model | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | T | Sig. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | Beta | B | Std. Error | ||

| 1 | (Constant) | 1.370 | 0.182 | 7.514 | 0.000 | |

| Age category | −0.006 | 0.049 | −0.012 | −0.118 | 0.907 | |

| Dependent Variable: Duration of the visit | ||||||

| Sum of Squares | Df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Between Groups | 0.125 | 1 | 0.125 | 0.457 | 0.500 |

| Within Groups | 26.865 | 98 | 0.274 | ||

| Total | 26.990 | 99 |

| Cases | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valid | Missing | Total | ||||

| N | Percent | N | Percent | N | Percent | |

| Occupation * Means of transportation | 100 | 100.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 100 | 100.0% |

| Means of Transportation | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | |||

| Occupation | 1 | Count | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Expected Count | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 1.0 | ||

| 2 | Count | 3 | 8 | 0 | 1 | 12 | |

| Expected Count | 2.4 | 4.2 | 1.4 | 4.0 | 12.0 | ||

| 3 | Count | 10 | 25 | 4 | 17 | 56 | |

| Expected Count | 11.2 | 19.6 | 6.7 | 18.5 | 56.0 | ||

| 4 | Count | 7 | 2 | 7 | 15 | 31 | |

| Expected Count | 6.2 | 10.9 | 3.7 | 10.2 | 31.0 | ||

| Total | Count | 20 | 35 | 12 | 33 | 100 | |

| Expected Count | 20.0 | 35.0 | 12.0 | 33.0 | 100.0 | ||

| Value | df | Asymp. Sig. (Two-Sided) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson Chi-Square | 29.848 (a) | 9 | 0.000 |

| Likelihood Ratio | 31.316 | 9 | 0.000 |

| Linear-by-Linear Association | 6.307 | 1 | 0.012 |

| No. of Valid Cases | 100 |

| Place of Origin | Accompanying Persons | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Place of origin | Pearson Correlation | 1 | 0.063 |

| Sig. (two-tailed) | 0.534 | ||

| N | 100 | 100 | |

| Accompanying persons | Pearson Correlation | 0.063 | 1 |

| Sig. (two-tailed) | 0.534 | ||

| N | 100 | 100 |

| N | Mean | Std. Deviation | Std. Error Mean | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Educational level | 100 | 1.83 | 0.378 | 0.038 |

| Guided tours | 100 | 0.54 | 0.501 | 0.050 |

| Test Value = 0 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t | df | Sig. (Two-Tailed) | Mean Difference | 95% Confidence Interval of the Difference | ||

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Educational level | 48.474 | 99 | 0.000 | 1.830 | 1.76 | 1.90 |

| Guided tours | 10.780 | 99 | 0.000 | 0.540 | 0.44 | 0.64 |

| Sources of Information | Main Reason for Visits | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sources of information | Pearson Correlation | 1 | 0.107 |

| Sig. (two-tailed) | 0.291 | ||

| N | 100 | 100 | |

| Main reason for visits | Pearson Correlation | 0.107 | 1 |

| Sig. (two-tailed) | 0.291 | ||

| N | 100 | 100 |

| Model | R | R Square | Adjusted R Square | Std. Error of the Estimate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.130 (a) | 0.017 | 0.007 | 0.612 |

| Model | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Regression | 0.631 | 1 | 0.631 | 1.686 | 0.197 (a) |

| Residual | 36.679 | 98 | 0.374 | |||

| Total | 37.310 | 99 | ||||

| Dependent Variable: Importance of religious establishments | ||||||

| Model | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | T | Sig. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | Beta | B | Std. Error | ||

| 1 | (Constant) | 4.443 | 0.157 | 28.352 | 0.000 | |

| Perception of religious tourism | 0.056 | 0.043 | 0.130 | 1.299 | 0.197 | |

| Dependent variable: Importance of religious establishments | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Drăguleasa, I.-A.; Niță, A.; Mazilu, M.; Constantinescu, E. Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage in Vâlcea County, South-West Oltenia Region: Motivations, Belief and Tourists’ Perceptions. Religions 2024, 15, 294. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15030294

Drăguleasa I-A, Niță A, Mazilu M, Constantinescu E. Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage in Vâlcea County, South-West Oltenia Region: Motivations, Belief and Tourists’ Perceptions. Religions. 2024; 15(3):294. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15030294

Chicago/Turabian StyleDrăguleasa, Ionuț-Adrian, Amalia Niță, Mirela Mazilu, and Emilia Constantinescu. 2024. "Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage in Vâlcea County, South-West Oltenia Region: Motivations, Belief and Tourists’ Perceptions" Religions 15, no. 3: 294. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15030294

APA StyleDrăguleasa, I.-A., Niță, A., Mazilu, M., & Constantinescu, E. (2024). Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage in Vâlcea County, South-West Oltenia Region: Motivations, Belief and Tourists’ Perceptions. Religions, 15(3), 294. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15030294