Antecedents and Perceived Benefits of Religious Conversion—An Exploratory Study within a Protestant Congregation

Abstract

1. Introduction

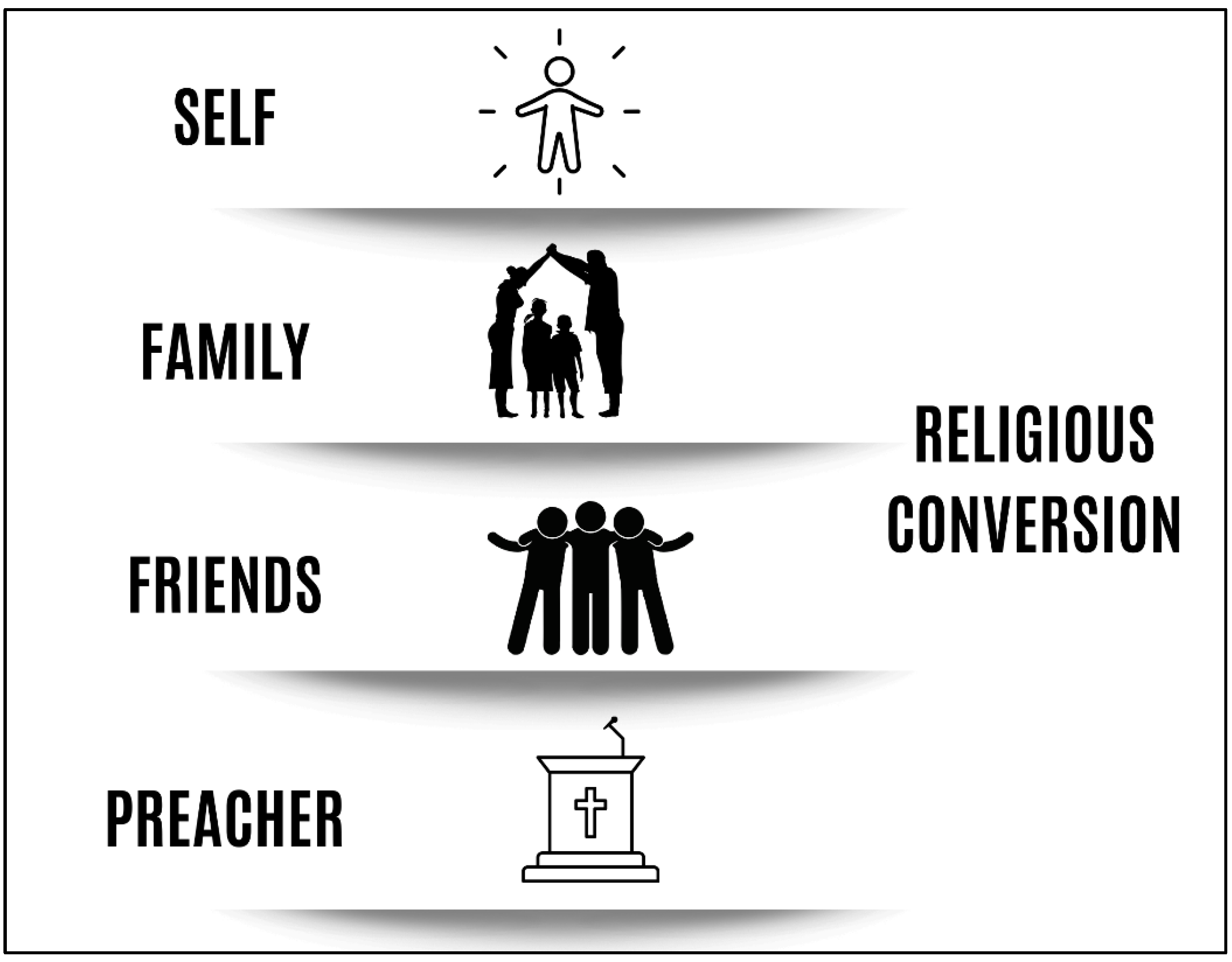

2. Antecedents of Religious Conversion

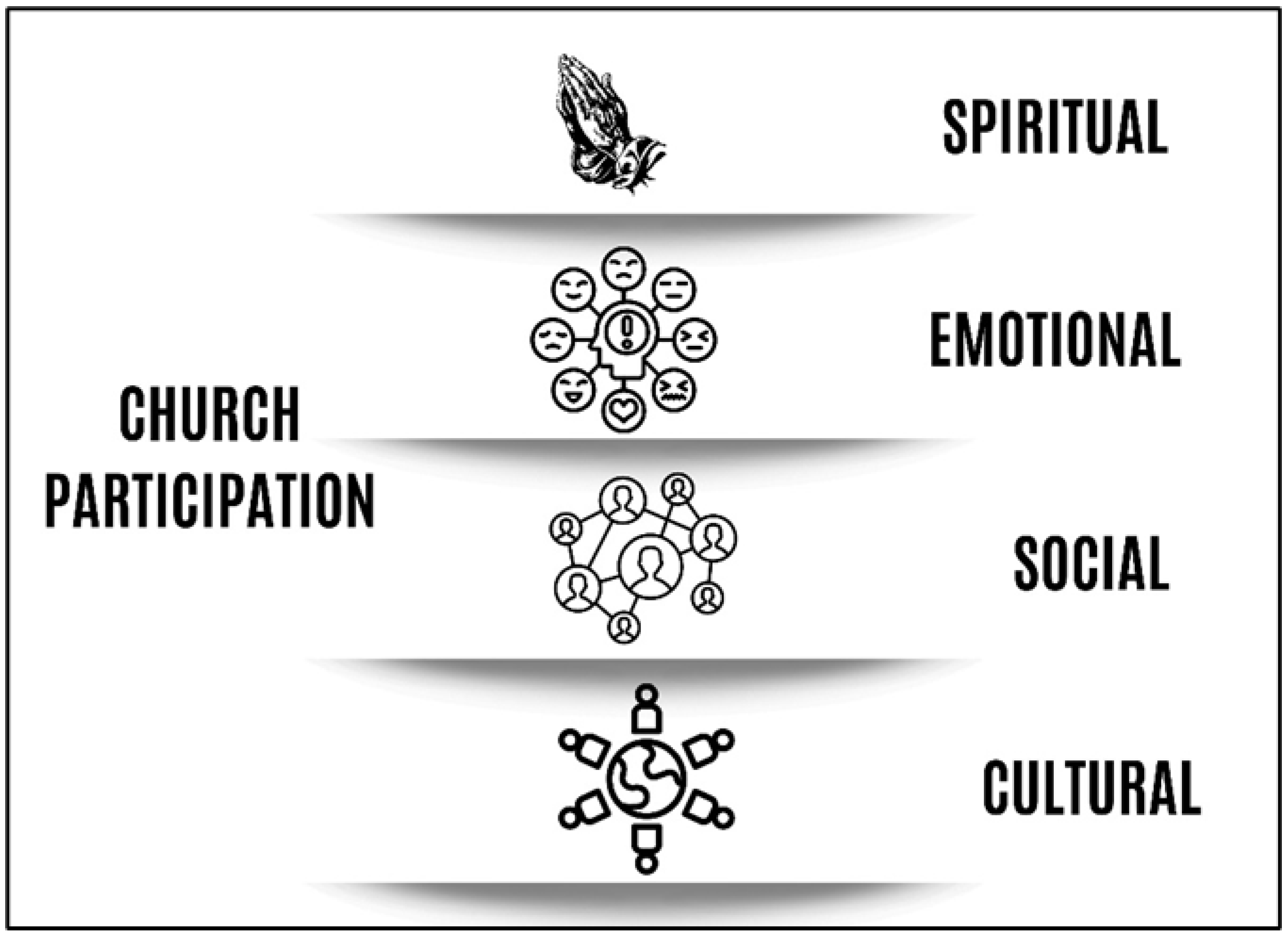

3. Perceived Benefits of Religious Conversion and Church Participation

4. Results and Discussion

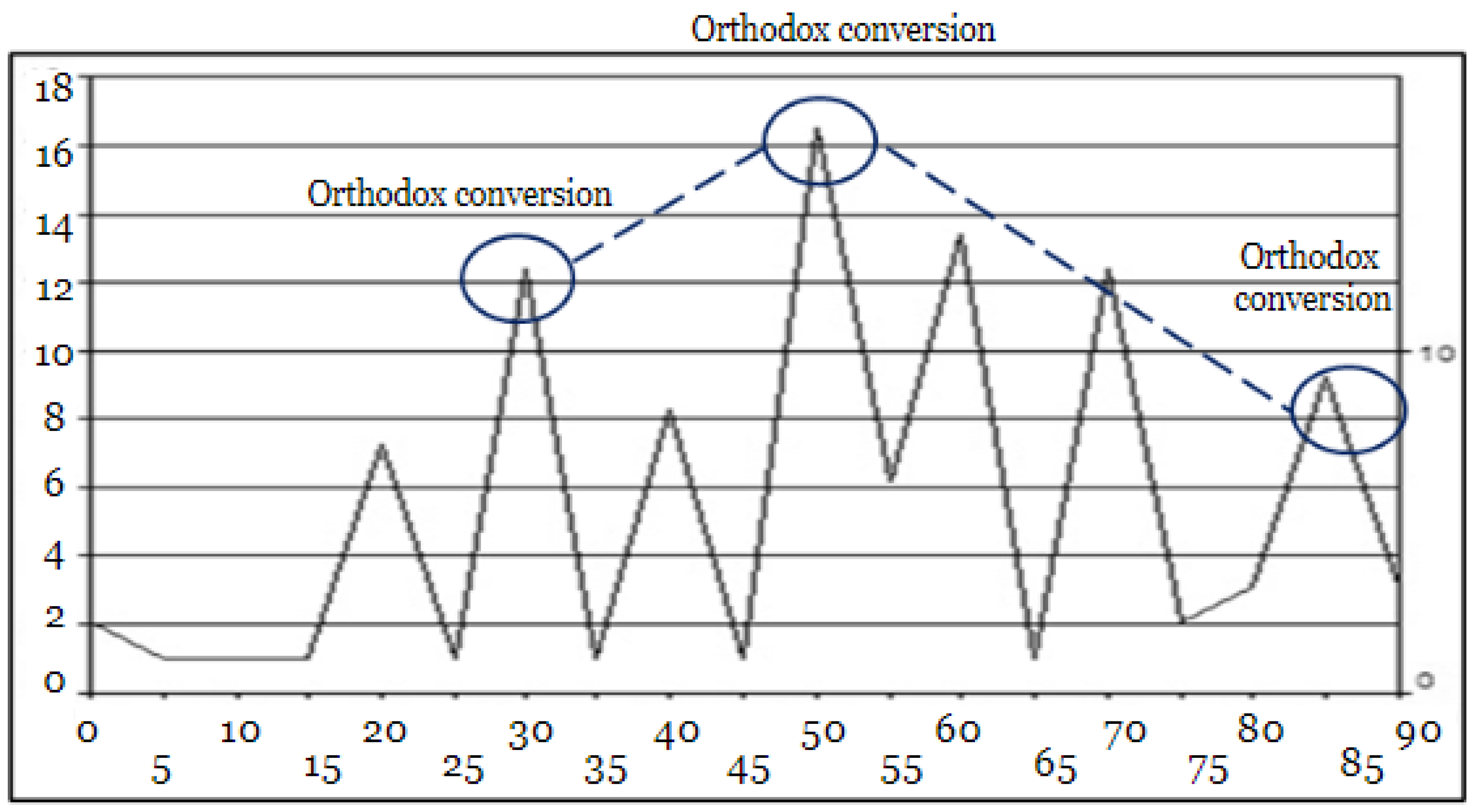

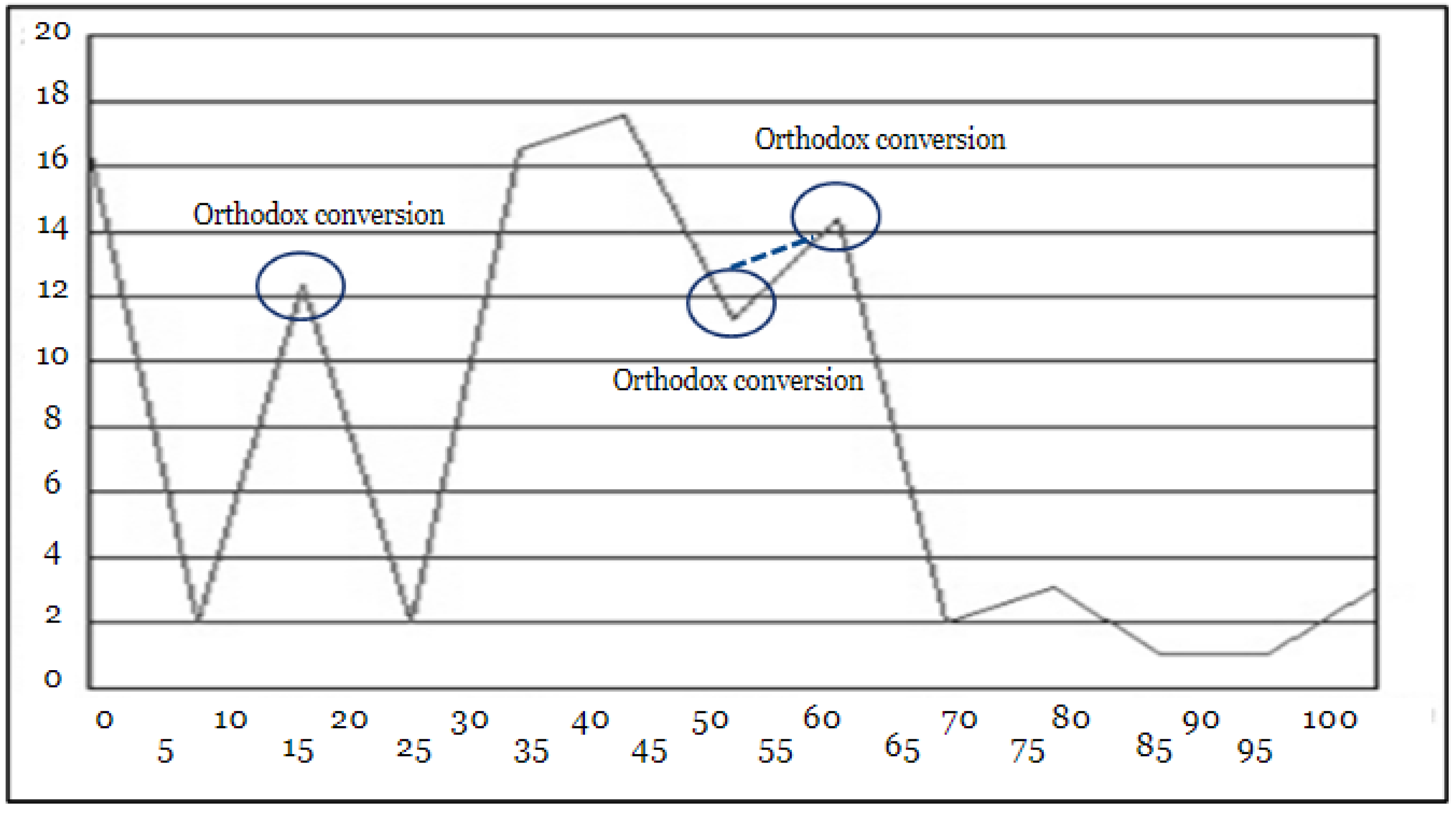

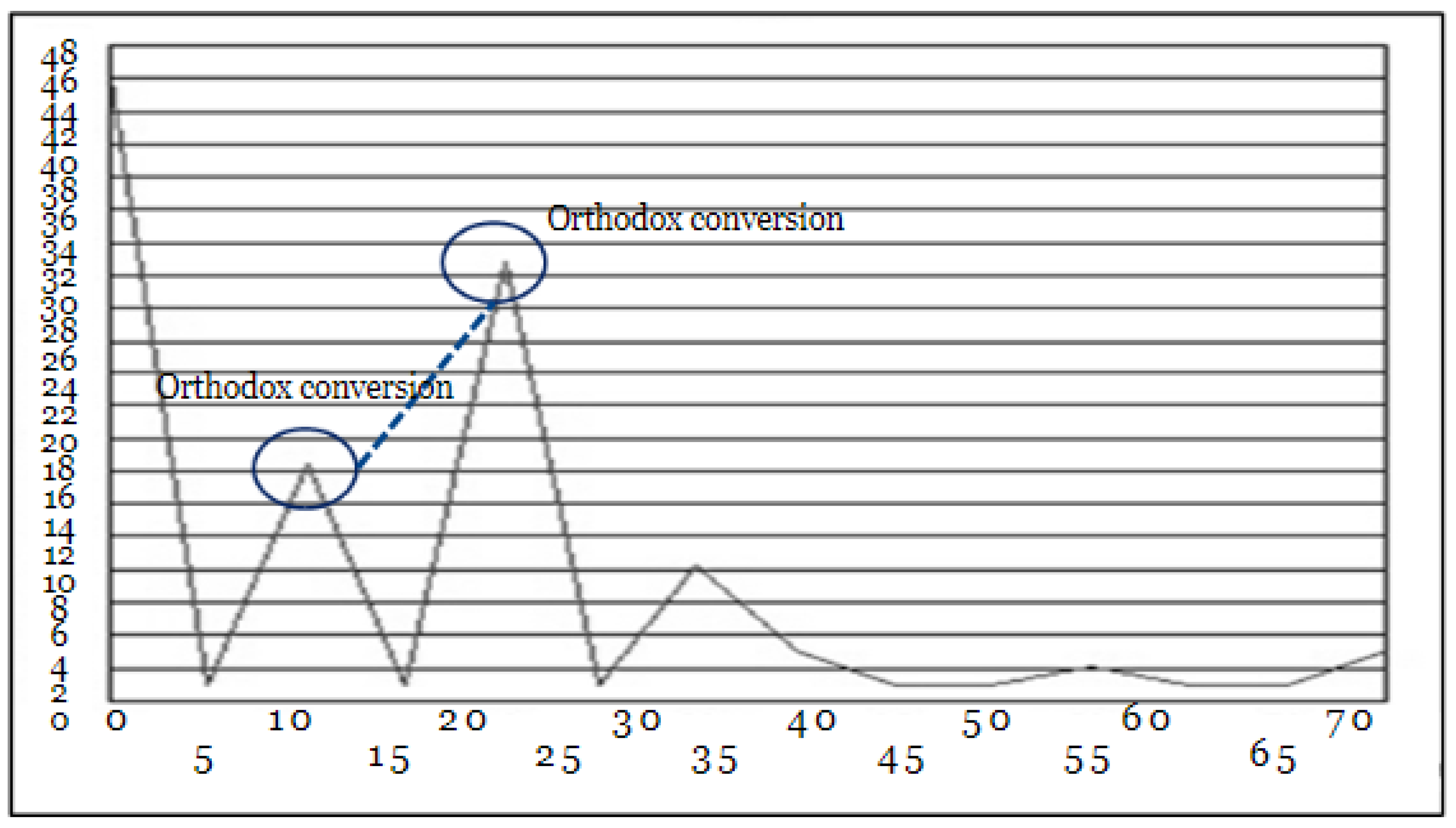

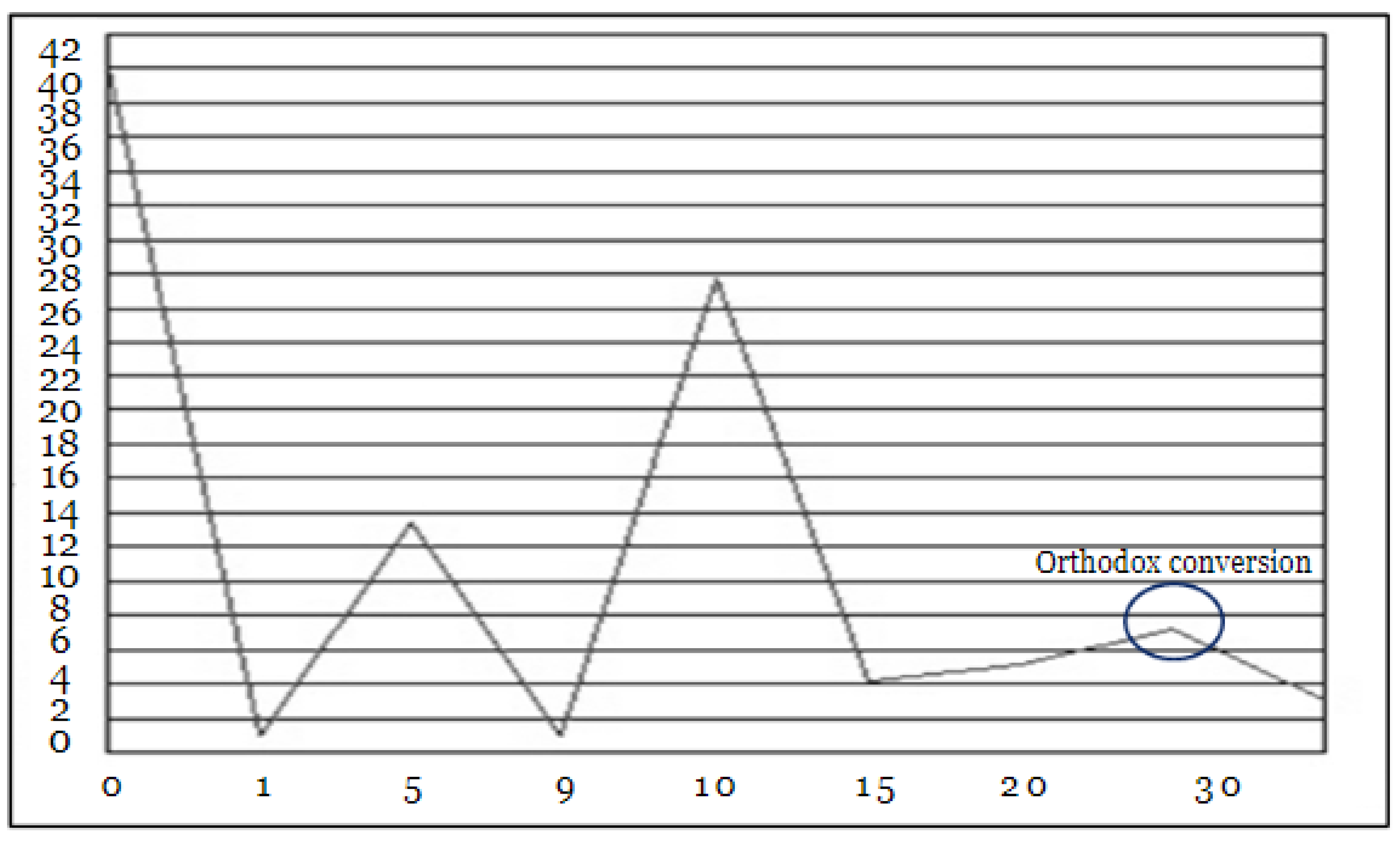

4.1. Antecedents of Religious Conversion to the Seventh-Day Adventist Church in Romania

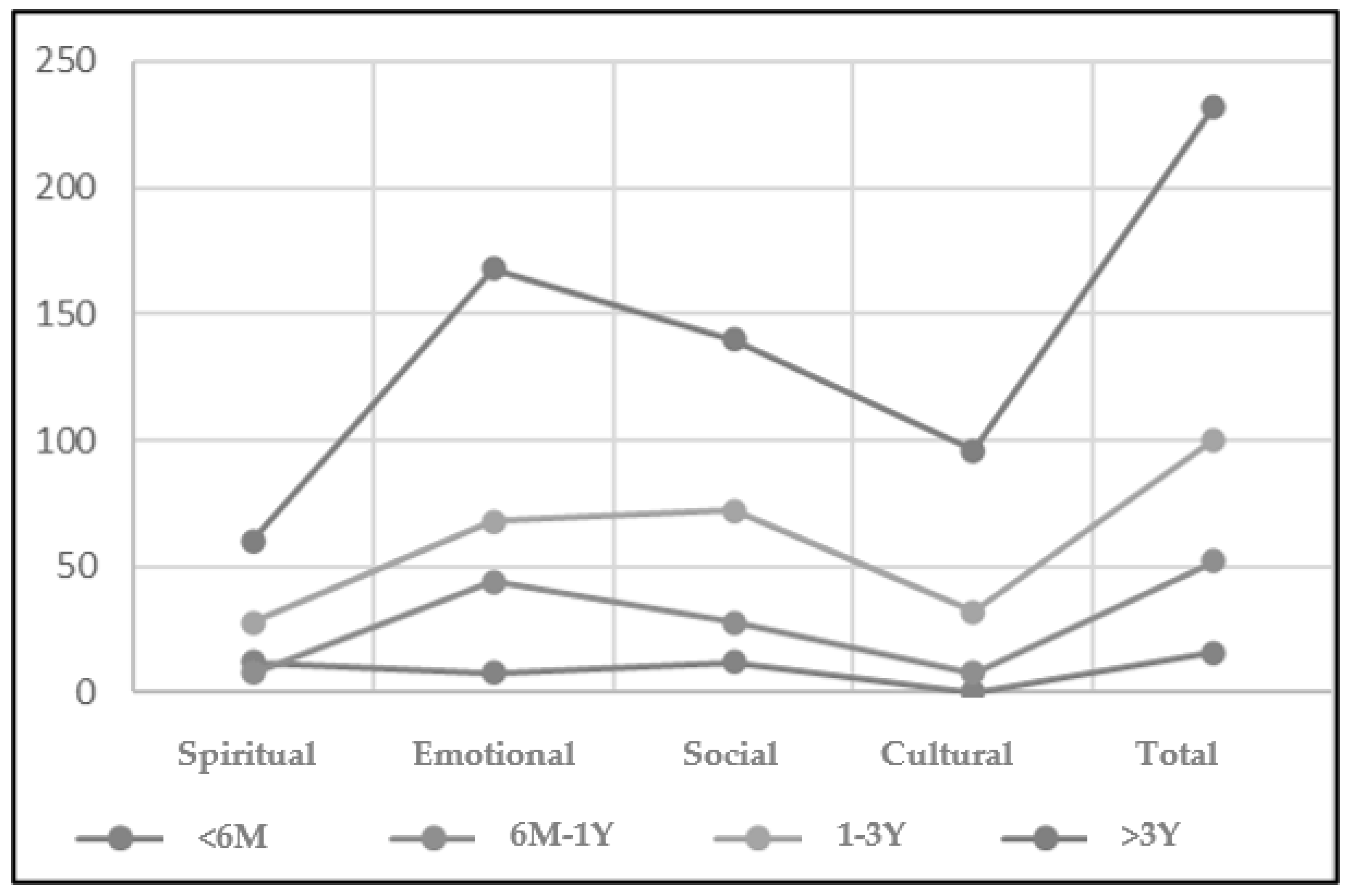

4.2. Perceived Benefits of Religious Conversion and Church Participation in the Seventh-Day Adventist Church in Romania

5. Research Methodology

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ammerman, Nancy T. 2020. Rethinking religion: Toward a practice approach. American Journal of Sociology 126: 6–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Rodney Dale. 2009. An Analysis of Attitudes, Values, and Beliefs of Congregants and Leaders of Small Churches toward Church Planting. Ph.D. thesis, The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, Louisville, KY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Bainbridge, William Sims. 1990. Explaining the church member rate. Social Forces 68: 1287–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, Peter, and Thomas Luckmann. 2023. The social construction of reality. In Social Theory Re-Wired. New York and London: Routledge, pp. 92–101. [Google Scholar]

- Button, Tanya M. M., Michael C. Stallings, Soo Hyun Rhee, Robin P. Corley, and John K. Hewitt. 2011. The etiology of stability and change in religious values and religious attendance. Behavior Genetics 41: 201–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlson, Thomas D., Dwight Kirkpatrick, Lorna Hecker, and Mark Killmer. 2002. Religion, spirituality, and marriage and family therapy: A study of family therapists’ beliefs about the appropriateness of addressing religious and spiritual issues in therapy. American Journal of Family Therapy 30: 157–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrell, Lori J. 2013. Preaching That Matters: Reflective Practices for Transforming Sermons. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Cheadle, Jacob E., and Philip Schwadel. 2012. The ‘friendship dynamics of religion,’ or the ‘religious dynamics of friendship’? A social network analysis of adolescents who attend small schools. Social Science Research 41: 1198–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, Peter B. 2004. New Religions in Global Perspective: Religious Change in the Modern World. New York and London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Clements, William M., and Howard Clinebell. 2013. Counseling for Spiritually Empowered Wholeness: A Hope-Centered Approach. New York and London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Copen, Casey E., and Merril Silverstein. 2008. The transmission of religious beliefs across generations: Do grandparents matter? Journal of Comparative Family Studies 39: 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davie, Grace. 2006. Religion in Europe in the 21st century: The factors to take into account. European Journal of Sociology/Archives Européennes de Sociologie 47: 271–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davie, Grace. 2012. Thinking sociologically about religion: Implications for faith communities. Review of Religious Research 54: 273–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dégremont, Cédric. 2010. The Temporal Mind. Observations on the Logic of Belief Change in Interactive Systems. Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam. [Google Scholar]

- Dudley, Roger L., and Margaret G. Dudley. 1986. Transmission of religious values from parents to adolescents. Review of Religious Research, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, Leslie J. 2013. Implicit religion, explicit religion and purpose in life: An empirical enquiry among 13-to 15-year-old adolescents. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 16: 909–21. [Google Scholar]

- Furseth, Inger, and Pål Repstad. 2017. An Introduction to the Sociology of Religion: Classical and Contemporary Perspectives. New York and London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, Sally K., and Chelsea Newton. 2009. Defining spiritual growth: Congregations, community, and connectedness. Sociology of Religion 70: 232–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallup, George, and Timothy K. Jones. 2000. The Next American Spirituality: Finding God in the Twenty-First Century. Colorado Springs: David C Cook. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, Amarjit, Harvinder S. Mand, Nahum Biger, and Neil Mathur. 2018. Influence of religious beliefs and spirituality on decision to insure. International Journal of Emerging Markets 13: 780–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorsuch, Richard L. 2019. Toward motivational theories of intrinsic religious commitment. In The Psychology of Religion. New York and London: Routledge, pp. 11–24. [Google Scholar]

- Héliot, YingFei, Ilka H. Gleibs, Adrian Coyle, Denise M. Rousseau, and Céline Rojon. 2020. Religious identity in the workplace: A systematic review, research agenda, and practical implications. Human Resource Management 59: 153–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertog, Katrien. 2010. The Complex Reality of Religious Peacebuilding: Conceptual Contributions and Critical Analysis. Lanham: Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Hjarvard, Stig. 2008. The mediatization of religion: A theory of the media as agents of religious change. Northern Lights: Film & Media Studies Yearbook 6: 9–26. [Google Scholar]

- Hjarvard, Stig. 2011. The mediatisation of religion: Theorising religion, media and social change. Culture and Religion 12: 119–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoge, Dean R., and David T. Polk. 1980. A test of theories of Protestant church participation and commitment. Review of Religious Research 21: 315–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoge, Dean R., and Jackson W. Carroll. 1978. Determinants of commitment and participation in suburban Protestant churches. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 17: 107–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoge, Dean R., Joseph J. Shields, and Douglas L. Griffin. 1995. Changes in satisfaction and institutional attitudes of Catholic priests, 1970–1993. Sociology of Religion 56: 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoover, Stewart M. 2006. Religion in the Media Age. New York and London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Rose L., Michael Tsiros, and Richard A. Lancioni. 1995. Measuring service quality: A systems approach. Journal of Services Marketing 9: 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, Peter J., and A. L. Greene. 2004. “Seeing conversion whole”: Testing a model of religious conversion. Pastoral Psychology 52: 233–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krok, Dariusz. 2015. The role of meaning in life within the relations of religious coping and psychological well-being. Journal of Religion and Health 54: 2292–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusmawati, Ati, and Cholichul Hadi. 2020. The Dynamics of Inner Peace of Delinkuen Students through a Religious Approach. Psikis: Jurnal Psikologi Islami 6: 139–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langston, Joseph, Heather Powers Albanesi, and Matthew Facciani. 2019. Toward Faith: A Qualitative Study of How Atheists Convert to Christianity. Journal of Religion & Society 21: 1. [Google Scholar]

- Lartey, Emmanuel Y. 2013. Postcolonializing God: New Perspectives on Pastoral and Practical Theology. Norwich: Hymns Ancient and Modern Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Levitt, Peggy. 2007. Redefining the boundaries of belonging: The transnationalization of religious life. In Everyday Religion: Observing Modern Religious Lives. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 103–20. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, Chaeyoon, and Robert D. Putnam. 2010. Religion, social networks, and life satisfaction. American Sociological Review 75: 914–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundby, Knut. 2011. Patterns of belonging in online/offline interfaces of religion. Information, Communication & Society 14: 1219–35. [Google Scholar]

- Lund, Gerald N. 2002. Personal Revelation and the Process of Conversion. Religious Educator: Perspectives on the Restored Gospel 3: 4. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, Thomas. 2017. Social construction and social critique: Haslanger, race, and the study of religion. Critical Research on Religion 5: 284–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, Annette, and Kenneth I. Pargament. 2004. Sacred changes: Spiritual conversion and transformation. Journal of Clinical Psychology 60: 481–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, Meredith B. 2008. Religion: The Social Context. Long Grove: Waveland Press. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, Jessica, and Tom Farsides. 2009. Measuring meaning in life. Journal of Happiness Studies 10: 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, Paul K. 2019. Understanding Religious Experience: From Conviction to Life’s Meaning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mugambi, Jesse Ndwiga Kanyua. 1996. Religion and Social Construction of Reality. Nairobi: Nairobi University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mulyanegara, Riza Casidy. 2011. The relationship between market orientation, brand orientation and perceived benefits in the non-profit sector: A customer-perceived paradigm. Journal of Strategic Marketing 19: 429–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, David G. 2000. The funds, friends, and faith of happy people. American Psychologist 55: 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norris, Rebecca Sachs. 2003. Converting to what? Embodied culture and the adoption of new beliefs. In The Anthropology of Religious Conversion. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, pp. 171–81. [Google Scholar]

- Ogne, Steven L., and Tim Roehl. 2008. Transformissional Coaching: Empowering Spiritual Leaders in a Changing Ministry World. Nashville: B&H Publishing Group. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, Daniel V. A. 1989. Church friendships: Boon or barrier to church growth? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 28: 432–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pargament, Kenneth I. 2001. The Psychology of Religion and Coping: Theory, Research, Practice. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament, Kenneth I. 2002. The bitter and the sweet: An evaluation of the costs and benefits of religiousness. Psychological Inquiry 13: 168–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, Edmund D. 2002. The physician’s conscience, conscience clauses, and religious belief: A Catholic perspective. Fordham Urban Law Journal 30: 221. [Google Scholar]

- Perez, Sergio, and Frédérique Vallières. 2019. How do religious people become atheists? Applying a grounded theory approach to propose a model of deconversion. Secularism and Nonreligion 8: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petts, Richard J. 2009. Trajectories of religious participation from adolescence to young adulthood. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 48: 552–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ploch, Donald R., and Donald W. Hastings. 1998. Effects of parental church attendance, current family status, and religious salience on church attendance. Review of Religious Research 39: 309–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop, Marian Rodion, and Ciprian-Marcel Pop. 2023. Exploring the influence of religious service characteristic on parishioners’ overall satisfaction in protestant church. European Journal of Science and Theology 19: 111–26. [Google Scholar]

- Py, Fábio, and Marcos A. Pedlowski. 2020. Pentecostalization of the Zumbi dos Palmares Sett lement, Campos dos Goytacazes. Perspectiva Teológica 52: 829–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Race, Alan. 2013. Making Sense of Religious Pluralism. London: Spck. [Google Scholar]

- Rambo, Lewis R. 1999. Theories of conversion: Understanding and interpreting religious change. Social Compass 46: 259–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambo, Lewis R., and Charles E. Farhadian. 1999. Converting: Stages of religious change. In Religious Conversion: Contemporary Practices and Controversies. London: A&C Black, pp. 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Roberto, John. 2007. Best practices in family faith formation. Lifelong Faith 1: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Roberto, John. 2012. The importance of family faith for lifelong faith formation. Lifelong Faith 1: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Rossiter, Graham. 2010. Religious education and the changing landscape of spirituality: Through the lens of change in cultural meanings. Journal of Religious Education 58: 25–36. [Google Scholar]

- Sam, David L., and John W. Berry. 2010. Acculturation: When individuals and groups of different cultural backgrounds meet. Perspectives on Psychological Science 5: 472–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, J. Oswald. 2017. Spiritual Leadership: Principles of Excellence for Every Believer. Chicago: Moody Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Sargeant, Kimon Howland. 2000. Seeker Churches: Promoting Traditional Religion in a Nontraditional Way. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, Paula M. 1999. Factors underlying church member satisfaction and retention. Journal of Customer Service in Marketing & Management 5: 31–43. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, Sonya. 2012. ‘The church is… my family’: Exploring the interrelationship between familial and religious practices and spaces. Environment and Planning A 44: 816–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherkat, Darren E. 2003. Religious socialization: Sources of influence and influences of agency. In Handbook of the Sociology of Religion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 151–63. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel, Daniel J. 2010. Mindsight: The New Science of Personal Transformation. Richmond: Bantam. [Google Scholar]

- Simmel, Georg. 1955. A contribution to the sociology of religion. American Journal of Sociology 60: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slagle, Amy. 2011. The Eastern Church in the Spiritual Marketplace: American Conversions to Orthodox Christianity. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smilde, David. 2005. A qualitative comparative analysis of conversion to Venezuelan evangelicalism: How networks matter. American Journal of Sociology 111: 757–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, Rodney, and William Sims Bainbridge. 1980. Networks of faith: Interpersonal bonds and recruitment to cults and sects. American Journal of Sociology 85: 1376–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stromberg, Peter G. 2008. Language and Self-Transformation: A Study of the Christian Conversion Narrative. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stroope, Samuel. 2011. How culture shapes community: Bible belief, theological unity, and a sense of belonging in religious congregations. The Sociological Quarterly 52: 568–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, Carlos Daniel. 2011. Why can’t we be friends: The role of religious congregation-based social contact for close interracial adolescent friendships. Review of Religious Research 52: 439–53. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton, Arland. 1985. Reciprocal influences of family and religion in a changing world. Journal of Marriage and the Family 47: 381–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, Nathan R., Emily J. Blevins, and Jacqueline Yi. 2020. A social network analysis of friendship and spiritual support in a religious congregation. American Journal of Community Psychology 65: 107–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Troeltsch, Ernst. 1992. The Social Teaching of the Christian Churches. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ullman, Chana. 2013. The Transformed Self: The Psychology of Religious Conversion. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer Science & Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- van Benthem, Johan, and Sonja Smets. 2015. Dynamic logics of belief change. In Handbook of Logics for Knowledge and Belief. Marshalls Creek: College Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Brug, Wouter, Sara B. Hobolt, and Claes H. De Vreese. 2009. Religion and party choice in Europe. West European Politics 32: 1266–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Niekerk, Marsulize, and Gert Breed. 2018. The role of parents in the development of faith from birth to seven years of age. HTS: Theological Studies 74: 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Wardekker, Willem L., and Siebren Miedema. 2001. Identity, cultural change, and religious education. British Journal of Religious Education 23: 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Latiena F., and Lakeshia Cousin. 2021. “A Charge to Keep I Have”: Black Pastors’ Perceptions of Their Influence on Health Behaviors and Outcomes in Their Churches and Communities. Journal of Religion and Health 60: 1069–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiramuda, Putra. 2018. The Meaning of Experiences of Religious Conversion Process. KnE Social Sciences 2018: 474–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrenn, Bruce, Norman Shawchuck, Philip Kotler, and Gustave Rath. 1995. What does it mean for pastors to adopt a market orientation? Journal of Ministry Marketing & Management 1: 5–23. [Google Scholar]

- Zaleski, Peter A., and Charles E. Zech. 1995. The effect of religious market competition on church giving. Review of Social Economy 53: 350–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Hansong, Joshua N. Hook, Jennifer E. Farrell, David K. Mosher, Laura E. Captari, Steven P. Coomes, Daryl R. Van Tongeren, and Don E. Davis. 2019. Exploring social belonging and meaning in religious groups. Journal of Psychology and Theology 47: 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Regression Statistics | Regression Statistics | ||||

| Multiple R | 0.4838 | Multiple R | 0.3483 | ||

| t Stat | 11.0283 | t Stat | 7.4135473 | ||

| Mean | 49.0000 | Mean | 25.7500 | ||

| Observations | 400 | Observations | 400 | ||

| p-value | 0.000 | p-value | 0.000 | ||

| Coefficients | p-value | Coefficients | p-value | ||

| Self | 0.4838 | 0.000 | Family | 0.3483 | 0.000 |

| Regression Statistics | Regression Statistics | ||||

| Multiple R | 0.1932 | Multiple R | 0.2330 | ||

| t Stat | 3.9288 | t Stat | 11.0283 | ||

| Mean | 8.3400 | Mean | 4.7789 | ||

| Observations | 400 | Observations | 400 | ||

| p-value | 0.001 | p-value | 0.000 | ||

| Coefficients | p-value | Coefficients | p-value | ||

| Friends | 0.1932 | 0.001 | Preacher | 0.2330 | 0.000 |

| Perceived Benefits | <6 Months | 6 M–1 Year | 1–3 Years | >3 Years |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spiritual | 12 | 8 | 28 | 60 |

| Emotional | 8 | 44 | 68 | 168 |

| Social | 12 | 28 | 72 | 140 |

| Cultural | 0 | 8 | 32 | 96 |

| Total | 16 | 52 | 100 | 232 |

| Regression Statistics | Regression Statistics | ||||||

| Multiple R | 0.3965 | Multiple R | 0.3174 | ||||

| R Square | 0.1572 | R Square | 0.1379 | ||||

| Standard Error | 0.5774 | Standard Error | 0.6169 | ||||

| Observations | 400 | Observations | 400 | ||||

| Significance F | 0.000 | Significance F | 0.0001 | ||||

| Coefficients | t Stat | p-value | Coefficients | t Stat | p-value | ||

| Intercept | 1.2143 | 13.9834 | 0.000 | Intercept | 1.4241 | 11.0393 | 0.0000 |

| Spiritual benefits | 0.5429 | 8.6170 | 0.000 | Emotional benefits | 0.2830 | 3.9589 | 0.0001 |

| Regression Statistics | Regression Statistics | ||||||

| Multiple R | 0.1664 | Multiple R | 0.1869 | ||||

| R Square | 0.0277 | R Square | 0.0040 | ||||

| Standard Error | 0.6202 | Standard Error | 0.6277 | ||||

| Observations | 400 | Observations | 400 | ||||

| Significance F | 0.001 | Significance F | 0.0001 | ||||

| Coefficients | t Stat | p-value | Coefficients | t Stat | p-value | ||

| Intercept | 1.5676 | 14.3569 | 0.0000 | Intercept | 1.8073 | 19.1939 | 0.0000 |

| Social Benefits | 0.2162 | 6.6769 | 0.0010 | Cultural benefits | 0.0849 | 3.7950 | 0.0010 |

| Characteristic | Description | Quantity | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 236 | 59 |

| Male | 164 | 41 | |

| Age | Up to 30 years | 68 | 17 |

| 31 to 40 years | 108 | 27 | |

| 41 to 60 years | 224 | 56 | |

| Education | Associate | 164 | 41 |

| Bachelor | 160 | 40 | |

| Master and above | 76 | 19 | |

| Status | Members | 368 | 92 |

| Non-members | 32 | 8 | |

| Members status background | Adventist | 256 | 64 |

| Orthodox | 128 | 32 | |

| Agnostic | 8 | 2 | |

| Pentecostal | 8 | 2 | |

| Non-members status background | Adventist | 8 | 25 |

| Orthodox | 24 | 75 | |

| Members’ average conversion time | less than 6 months | 68 | 17 |

| 7 to 12 months | 32 | 8 | |

| 1 to 3 years | 44 | 11 | |

| 3 to 10 years | 64 | 16 | |

| more than 10 years | 192 | 48 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pop, M.R.; Pop, C.M. Antecedents and Perceived Benefits of Religious Conversion—An Exploratory Study within a Protestant Congregation. Religions 2024, 15, 156. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15020156

Pop MR, Pop CM. Antecedents and Perceived Benefits of Religious Conversion—An Exploratory Study within a Protestant Congregation. Religions. 2024; 15(2):156. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15020156

Chicago/Turabian StylePop, Marian Rodion, and Ciprian Marcel Pop. 2024. "Antecedents and Perceived Benefits of Religious Conversion—An Exploratory Study within a Protestant Congregation" Religions 15, no. 2: 156. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15020156

APA StylePop, M. R., & Pop, C. M. (2024). Antecedents and Perceived Benefits of Religious Conversion—An Exploratory Study within a Protestant Congregation. Religions, 15(2), 156. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15020156