An Old Uighur balividhi Fragment Unearthed from the Northern Grottoes of Dūnhuáng

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Edition of the Text

2.1. Transliteration and Transcription

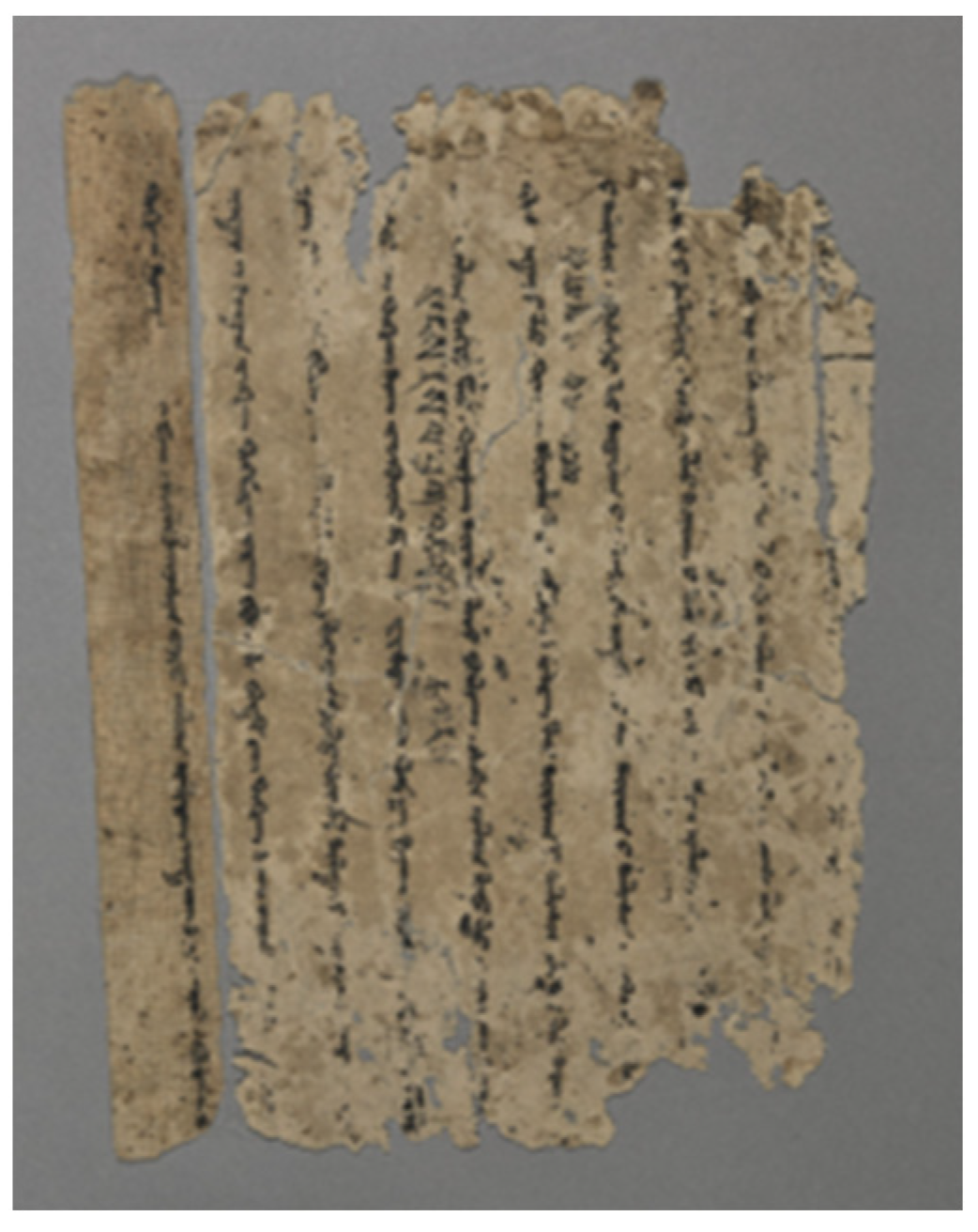

- B121:38 Recto (Figure 1)

- 01 01 t’k’-q’///r-mn. wylkwl’nčsyz včyr wlwq ylyk ’d’rtsyz/čyr kwyk///

- 01 01 taka-ka [yükünü]r-m(ä)n. ülgülänčsiz včir ulug ilig adartsïz včir kök/////

- 02 02 ynṭyn qydyqynk’ t’km’kyk bwl/yš p’dm’t’k’qa ywyk///mn/////

- 02 02 ïnṭïn kïdïg-ïnga tägmäk-ig bul[m]ïš padma-taka-ka yük[ünür]-m(ä)n/////

- 03 03 č’//////bwrh’n alqw s’qynčl’ryq twlw twyk’l qyld’čy.///dy//’/////

- 03 03 č’ [ amogašidi ilig] burhan alku sakïnč-larïg tolu tükäl kïlṭačï. [čïnžu arïg süzük]dï[n]

- 04 04//šw/t’k’q’ ywykwnwrmn: vyšw’t’k’q’ ywykwnwp m/////y

- 04 04 [vi]šu-[a]-taka-ka yükünür-m(ä)n: višu-a-taka-ka yükünüp m/////y

- 04+ sangs ras la phyag ’tsalo || rgya kar (?skad) ||

- 05 05 s/////wlwq t’ngryl’r tyryn qwvr’ql’ry byrl’ s’kyz wlwq lwwl’r./yryn qwvr/////

- 05 05 s[äkiz] ulug tängri-lär terin kuvrag-larï birlä säkiz ulug luu-lar. [t]erin kuvr[ag-larï birlä yertinčüdäki säkiz]

- 06 06 kwys’//d’čyl’r. tyryn qwvr’ql’r byrl’. y’kl’r qwvr’qy q’lysyz/’k/’zl’r//////////////

- 06 06 küẓä[t]däči-lär. terin kuvraglar birlä. yäk-lär kuvrag-ï kalïsïz [r]ak[š]a[z]l[ar] [gandrvelar kuvrag]-

- 06+ sang. ? ??ga so

- 07 07 y q’lysyz. pyš’čyl’r qwvr’qy q’lysyz. wdm//y l’r qwvr’qy q’lysyz. ’p’/sm///

- 07 07 ï kalïsïz. pišači-lar kuvrag-ï kalïsïz. udmaḑa-lar kuvrag-ï kalïsïz. [a]pasm[ara]

- 08 08 qwvr’qy q’lysyz. t’k’l’r qwvr’qy q’lysyz m/////t’ wlwq/////

- 08 08 kuvragï kalïsïz. taka-lar kuvrag-ï kalïsïz t[a]kini ]-ta ulug/////

- 09 09 q’ly////mwnt’////p my///lk’rw ‘///ly//////l/r////l’r/////

- 09 09 kalïsïz munta kälip mi[ ]l-gärü a[ ]lï.[ ] l[ ]r. [ ]lar/////

- 10 10 /////

- B121:38 Verso (Figure 2)

- 11 01///////q wl wynki t’k’l’ryq bwltwrm’q qylyp////

- 11 01 [ ]k ol öngi takalar-ïg bulturmak kïlïp [ tolu tükäl kïlïp]

- 12 02/////sydyl’ryq m’nk’ byrwy y’rlyq’zwnl’r. t’nq’ryqlyql’r myny kwys’d///

- 12 02 [ alku] sidi-lar-ïg manga berü yarlïkazun-lar. tangarïg-lïg-lar mini küẓäd[ip ]

- 13 03 yyš twš bwlzwnl’r. wydswz wylwm byrl’ yk k’ml’ryk trs ’l’r…

- 13 03 iiš tuš bolzun-lar. üdsüz ölüm birlä ig käm-lär-ig t(ä)rs ’-l’r…

- 14 04 lr. y’vyz twyl byrl’ y’vyz b’lkwyl’ryk. y’vyz qylylmyšl’ryq ywq’dtwrz/////

- 14 04 l(A)r. yavïz tül birlä yavïz bälgü-lär-ig. yavïz kïlïlmïš-lar-ïg yokadturz[un-lar]

- 15 05 ’s’n qylyp twyš t’mlryq bwytwrm’k qylyp y t’ryql’ryq wyklydyp ‘syp

- 15 05 äsän kïlïp tüš tam-lar-ïg bütürmäk kïlïp ï tarïg-lar-ïg üklidip asïp

- 16 06 ’lqw ynč ’s’n bwlm’qyq bwyṭwrm’klyk kwynkwlt’ky ’lqw kwyswšl’ry////bwyṭ///

- 16 06 alku enč äsän bolmak-ïg büṭürmäk-lig köngül-täki alku küsüš-läri [kanzunlar] büṭ[zünlär ]

- 17 07 ’nt’ b’s’ d’rnyl’r wyn ’kẓykl’r byrl’ b’lyny t’šqwrw ws’ṭyp t’pyq dyr’vyl//

- 17 07 anta basa darni-lar ün ägẓig-lär birlä bali-nï tašguru ušaṭïp tapïg diravi-l[ar ]

- 18 08/////p v’m’p’d’ky hwng pt tym’k wyz’ ’ryṭyp wwm swv’p’p’ swtd’

- 18 08 [ ]p vamapadaki hong p(a)t temäk üzä arïṭïp oom suvapap-a sutda

- 19 09 ///////qwrwq s’qynyp qwrwqt’ t’pyq dyr’vyl’ryq ws’typ///////

- 19 09 [ ] kurug sakïnïp kurug-ta tapïg diravi-larïg ušatïp…

2.2. English Translation

3. Commentary

4. The Parallel Tibetan Text

- A.

- Verses of praise for the five ḍākas: lines 1–4;

- B.

- Transference of merit. B-1 to the deities and demons: lines 5–9; B-2 and to oneself: align 9–17.

- C.

- A mantra: lines 17–19.

- (1)

- Offering gtor ma (gtor ma dbul ba)

- (2)

- Worship (mchod pa)

- (3)

- Praise (bstod pa)

- (4)

- The transfer of merits (phrin las gzhol ba)

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviation

| Bka’ | Bka’ ’gyur dpe sdur ma, edited by Krung go’i bod kyi shes rig zhib ’jug lte gnas kyi bka’ bstan dpe sdur khang. Vols. 120. Beijing: Krung go’i bod kyi shes rig dpe skrun khang, 2006–2009 |

| Bstan | Bstan ’gyur dpe sdur ma, edited by Krung go’i bod kyi shes rig zhib ’jug lte gnas kyi bka’ bstan dpe sdur khang. Vols. 120. Beijing: Krung go’i bod kyi shes rig dpe skrun khang, 1994–2008. |

| Dpal dus cho ga | Tāranātha 1979–1981 |

| T | Taishō shinshū daizōkyō 大正新脩大藏經 [Taishō Tripiṭaka], edited by Takakusu Junjirō 高順次郎 et al. Tokyo: Taishō issaikyō kankōkai, 1924–1935. |

| NGMD | The Northern Grottoes of Mògāo Caves, Dūnhuáng (Péng, Jīnzhāng 彭金章, Jiànjūn Wáng 王建军, and Dūnhuáng Academy 敦煌研究院 2000, 2004a, 2004b) |

| 1 | Regarding the entire Old Uighur texts included in NGMD, there is the first investigation by Tieshan Zhāng (2004); a comprehensive description is given in (Yakup 2006). |

| 2 | Zhang Tieshan did not conduct the transcription and identification of the text. See (Zhāng 2004, p. 361). |

| 3 | Shōgaito has a detailed discussion of this sound change at an early stage, see (Shōgaito 1978, pp. 80–109). |

| 4 | A remark on the style: The text underlined “_” refers to the content that parallels the Old Uighur text. The text enclosed in brackets “( )” are omitted content in the original Tibetan text. Serial numbers are added by the author. The English version of part A is based on the Sanskrit version of Guhyasamāja Tantra and the translation of Fremantle (1971, p. 122). The other parts are translated by the author based on Tibetan. |

| 5 | In the original text, the editor uses two tiny semicircle marks below the two lines of the end mark to indicate the duplicate phrase. |

| 6 | It is read as prakṛtiprabhāsvarān dharmān in the version of Matshunaga (1978, p. 96), but the reading as prakṛtiprabhās varagrāgra agrees more with Tibetan translation in the gtor ma text. |

| 7 | According to Matsunaga (1978, p.96n.18), there is bhāṣaguhya as variant of kāyavajra, which can parallel the Tibetan translation gsang ba gsungs shig. |

| 8 | The Chinese translation of this praising verse in Song dynasty see T 885 [XVIII] (p. 500 c14-25): 阿閦如來廣大智,金剛法界大希有,三曼拏羅三堅固,歸命祕密妙法音。毘盧遮那佛清淨,最上大樂金剛寂,諸法自性淨光明,歸命宣說金剛法。寶生如來甚深妙,如虛空界離諸垢,自性清淨本非相,歸命善說諸祕密。無量壽佛大自在,離諸疑惑金剛住,了貪自性到彼岸,歸命蓮華部所說。不空成就佛正智,能滿一切眾生願,自性清淨住實際,歸命金剛最上士。 |

| 9 | This mantra is very common in Tantric rituals, as it is also used in lines 18–20 of T Ix (U 5382) in a Cakrasamvara ritual fragment in Old Uighur unearthed from Turpan, see Kara and Zieme (1976, p. 73). |

References

Primary Sources

Bsod nams rtse mo. 2007. Dpal kye’i rdo rje’i mngon par rtogs pa yan lag bzhi pa. In Sa skya bka’ ’bum dpe bsdur ma las bsod nams rtse mo’i gsung ’bum pod gsum pa. Beijing: Krung go’i bod rig pa dpe skrun khang, pp. 219–81.La ba pa. 1996. Bde mchog gi dkyil ’khor gyi cho ga rin po che rab tu gsal ba’i sgron ma. In Bstan. Beijing: Krung go’i bod kyi shes rig dpe skrun khang, vol. 11, pp. 652–703.De bzhin gshegs pa thams cad kyi sku gsung thugs kyi gsang chen gsang ba ’dus pa zhes bya ba brtag pa’i rgyal po chen po. 2001. In Bka’. Beijing: Krung go’i bod kyi shes rig dpe skrun khang, vol. 81, pp. 289–426.Dpal kye rdo rje’i gtor ma’i cho ga. 1995. In Bstan. Beijing: Krung go’i bod kyi shes rig dpe skrun khang, vol. 5, pp. 1321–327.Fremantle, Francesca. 1971. A Critical Study of the Guhyasamāja Tantra. University of London Ph.D. dissertation: London, UK.Matsunaga, Yukei. 1978. Guhyasamāja Tantra. Osaka: Toho Shuppan.Mgon po bya rog gdong gi gtor mdos. 1999. In Bstan. Beijing: Krung go’i bod kyi shes rig dpe skrun khang, vol. 47, pp. 619–39.T. 262 [IX]: 1–62. Ven. Jiūmóluóshí 鳩摩羅什 (Kumārajiva) (translator), Miàofǎ liánhuā jīng 妙法蓮華經 [Saddharmapuṇḍarīkasūtra]. Available online: https://cbetaonline.dila.edu.tw/zh/T0262_001 (accessed on 22 May 2024).T 885. Ven. Shīhù 施護 (Dānapāla)(translator), Fóshuō yīqièrúlái jīngāngsānyè zuìshàngmìmì dajiàowángjīng 佛說一切如來金剛三業最上祕密大教王經 (Guhyasamājatantra). Available online: https://cbetaonline.dila.edu.tw/zh/T18n0885 (accessed on 22 May 2024).Tāranātha. 1979–1981. Dpal dus kyi ’khor lo’i dbang gong ma’i cho ga. In Gdams nag mdzod, vol. 15. Edited by ’Jam mgon Kong sprul Blo gros mtha’ yas. Paro: Lama Ngodrub and Sherab drimer, pp. 105–31.Secondary Sources

- Kara, Georg, and Peter Zieme. 1976. Fragmente tantrischer Werke in uigurischer Übersetzung. (Berliner Turfantexte VII). Berlin: Akademie Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, John. 1998. Islam in the Kālacakratantra. Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies 21: 311–17. [Google Scholar]

- Otγon 敖特根. 2009. Mògāokū béiqū chūtǔ huíhúménggǔwén rùpúsàxínglùn yìnběn cányè 莫高窟北区出土回鹘蒙古文《入菩萨行论》印本残叶 [Fragments of the Printed Mongolian Old Uighur Manuscript of Bodhicaryāvatāra from the Northern Grottoes of Mògāo Caves]. Lánzhōu xúekān兰州学刊, 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Péng, Jīnzhāng 彭金章, ed. 2003. Dūnhuáng shíkū quánjí 10 mìjiào huàjuàn 敦煌石窟全集10 密教畫卷 [Complete Collection of Dūnhuáng Grottoes Vol.10 Esoteric Buddhist Scrolls.]. Beijing 北京: Shangwu yinshuguan 商務印書館. [Google Scholar]

- Péng, Jīnzhāng 彭金章, Jiànjūn Wáng 王建军, and Dūnhuáng Academy 敦煌研究院, eds. 2000. Dūnhuáng mògāokū béiqūshíkū dìyījùan 敦煌莫高窟北区石窟 第一卷 [The Northern Grottoes of Mògāo Caves, Dūnhuáng vol. 1]. Beijing 北京: Wenwu chubanshe 文物出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Péng, Jīnzhāng 彭金章, Jiànjūn Wáng 王建军, and Dūnhuáng Academy 敦煌研究院, eds. 2004a. Dūnhuáng mògāokū béiqūshíkū dìèrjùan 敦煌莫高窟北区石窟 第二卷 [The Northern Grottoes of Mògāo Caves, Dūnhuáng vol. 2]. Beijing 北京: Wenwu chubanshe 文物出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Péng, Jīnzhāng 彭金章, Jiànjūn Wáng 王建军, and Dūnhuáng Academy 敦煌研究院, eds. 2004b. Dūnhuáng mògāokū béiqūshíkū dìsānjùan 敦煌莫高窟北区石窟 第三卷 [The Northern Grottoes of Mògāo Caves, Dūnhuáng vol. 3]. Beijing 北京: Wenwu chubanshe 文物出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Shōgaito, Masahiro 庄垣内正弘. 1978. Kodai uigurugo ni okeru indo raigen shakuyō goi no michiire keiro ni tsuite古代ウイグル語におけるインド来源借用語彙の道入経路について [On the routes of the loan words of Indic origin in the Old Uigur language]. Journal of Asian and African Studies アジア·アフリカ言語文化研究 15: 79–110. [Google Scholar]

- van der Kuijp, Leonard W. J. 2004. The Kālacakra and the Patronage of Tibetan Buddhism. Bloomington: Department of Central Eurasian Studies Indiana University. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkens, Jens. 2021. Handwörterbuch des Altuigurischen: Altuigurisch—Deutsch—Türkisch. Göttingen: Universitätsverlag. [Google Scholar]

- Wú, Xuěméi 吴雪梅, and Wútián Shā 沙武田. 2023. Mògāokū běiqū yuán dài yìkū B121kū sǐzhě shēnfèn kǎo 莫高窟北区元代瘗窟死者身份考 [A Study on the Identity of the Deceased Woman in Yuan Dynasty Cave B121 at the Mògāo Grottoes]. Dūnhuáng yánjiū 敦煌研究 2023: 76–87. [Google Scholar]

- Yakup, Abdurishid. 2006. Uigurica from Northern Grottoes of Dūnhuáng. In A Festschrift in Honour of Professor Masahiro Shōgaito’s Retirement—Studies on Eurasian Languages ユーラシア諸言語の研究: 庄垣内正弘先生退任記念論集. Kyoto: Nakanishi, pp. 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Zhāng, Tiěshān 张铁山. 2004. Dūnhuáng mògāokū běiqūshíkū chūtǔ huíhúwénwénxiàn yùshìyánjiū 敦煌莫高窟北區石窟出土回鶻文文獻譯釋研究(一)[Research on the Translation and Interpretation of Uighur Documents Unearthed from the Northern Caves of Mògāo Grottoes in Dūnhuáng Part 1]. In Dūnhuáng mògāokū béiqūshíkū dìèrjùan 敦煌莫高窟北区石窟 第二卷 [The Northern Grottoes of Mògāokū, Dūnhuáng vol. 2]. Edited by Jīnzhāng Péng 彭金章, Jiànjūn Wáng 王建军 and Dūnhuáng Academy 敦煌研究院. Beijing 北京: Wenwu chubanshe 文物出版社, pp. 361–68. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mirkamal, A.; Li, X. An Old Uighur balividhi Fragment Unearthed from the Northern Grottoes of Dūnhuáng. Religions 2024, 15, 1484. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15121484

Mirkamal A, Li X. An Old Uighur balividhi Fragment Unearthed from the Northern Grottoes of Dūnhuáng. Religions. 2024; 15(12):1484. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15121484

Chicago/Turabian StyleMirkamal, Aydar, and Xiaonan Li. 2024. "An Old Uighur balividhi Fragment Unearthed from the Northern Grottoes of Dūnhuáng" Religions 15, no. 12: 1484. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15121484

APA StyleMirkamal, A., & Li, X. (2024). An Old Uighur balividhi Fragment Unearthed from the Northern Grottoes of Dūnhuáng. Religions, 15(12), 1484. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15121484