4.1. The Shared Duty of Homo Climaticus and Homo Religiosus to Care for the Environment

Usually, when discussing environmental problems and possible solutions, Homo Religiosus is not mentioned. However, within the framework of this article, the authors wish to highlight the interaction between Homo Climaticus and Homo Religiosus. Religious texts emphasize that God is the patron of the environment, considering that God is the creator of the Earth.

At the beginning of the Bible, the first chapter of Genesis starts with the words: “In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth. The earth was barren with no form of life; it was under a roaring ocean covered with darkness. But the Spirit of God was moving over the water” (Genesis, 1:1–2). The chapter further describes the creation of the Earth, the separation of light and darkness, the formation of dry land by separating the waters, the greening of the Earth, and the creation of animals. It is stated: “And God said, Let us make man in our image, after our likeness: and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth. So God created man in his own image, in the image of God created he him; male and female created he them. And God blessed them, and God said unto them, Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it: and have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that moveth upon the earth” (Genesis, 1:26–28). From these verses, it can be inferred that God created man to live in God’s created world and protect everything created by God. This is also indicated by the conclusion of the chapter: “God looked at what he had done. All of it was very good!” (Genesis, 1:31). This chapter includes God’s approval of his created world and the duty assigned by God to his created man to care for everything created by God and deemed good.

1Sanita Osipova has pointed out that legal historians who base their research on the development of canonical law and its influence on secular law in the history of European law start with ancient Jewish law. S. Osipova refers to the conclusions of the Italian historian Paolo Prodi, who suggests that the prehistory of European legal history could be analyzed through the laws of Egyptians, Sumerians, Babylonians, and ancient Jews, whose norms were included in the Bible as the basis of the understanding of law (

Osipova 2017).

Considering ancient Jewish law, it is essential to include not only Judaism but also the origins of Christianity and Islam from Judaism. Therefore, these three religions are collectively referred to as the Abrahamic religions. Abraham is considered the patriarch of these three religions, as mentioned in the sacred texts of all these religions. Although Abraham’s story, described in the Bible, does not initially convey the belief that Abraham could be the central figure in the creation of Judaism, Islam, and Christianity, all these religions consider Abraham a model of faith and courage. Abraham’s story begins with him calling his wife his sister out of fear of being killed for her beauty and selling her to the Pharaoh for prostitution. Then, Abraham mistreated his slave, but when she bore him a son, he sent them both into the desert to die, while he took his other son to the mountains to sacrifice him to God, only to be stopped by divine intervention (

Hughes 2012).

In discussing the actions of Abraham, particularly in relation to Sarai and Hagar, it is important to recognize that there are multiple interpretations across different religious traditions and scholarly perspectives. While the narrative in Genesis presents a complex interplay of faith, obedience, and human frailty, Jewish Midrash and Islamic Tafsir literature often provide alternative readings that emphasize different aspects of the story (

Ginzberg 1998). For instance, in Islamic tradition, Hagar is revered as a key figure in the establishment of the Kaaba, and her story is framed within the context of divine providence and dignity (

Ibn Kathir 2000). Moreover, modern feminist scholars, such as Phyllis Trible, have critiqued the patriarchal elements of the narrative, highlighting the marginalized position of Hagar (

Trible 1984). These varied interpretations underscore the richness of the Abrahamic narrative and remind us that the ethical implications of Abraham’s actions are subject to ongoing theological and scholarly debate. Therefore, while this manuscript references certain critiques of Abraham’s behavior as discussed by Hughes, it is essential to acknowledge that these actions are viewed differently across religious and scholarly contexts, with some interpretations offering alternative perspectives.

Given that the essence of Homo Religiosus is derived from the religious norms discussed in this article, determining how a religious person should act, it becomes acutely necessary to examine the influence of these religious rights on modern law. Homo Climaticus is without borders until they are defined. In the modern world, borders arise from various normative acts that specify certain duties to be followed. Thus, Homo Climaticus is created precisely by applying the rights and duties contained in religious texts.

Regarding Homo Climaticus’ rights and duties, these are understood and applied as environmental rights, encompassing various normative act bases with a common goal—protecting the environment, ensuring a favorable and sustainable quality of life for future generations. Environmental rights include reducing the use of non-renewable resources, lowering emissions, using renewable energy, and preserving habitat diversity. However, examining the religious texts of the mentioned religions reveals that they also include rights and duties defining Homo Religiosus’ lifestyle concerning the environment created by God and deemed good. Thus, Homo Religiosus’ duty is to love and protect God’s creation, not to destroy it. This article will cite verses from the books of Moses that apply to both Judaism and Christianity, as they are included in both the Torah and the Bible, specifically the Old Testament.

The Bible contains God’s assigned duty to his created man to care for all his creation: “And the LORD God took the man, and put him into the garden of Eden to dress it and to keep it” (Genesis, 2:15). This verse and the following chapter clearly state that God is the creator of everything and that he has appointed man as the protector of all that is natural. In the same chapter, God told man: “But the Lord told him, “You may eat fruit from any tree in the garden,”” (Genesis, 2:16), indicating that God created the surrounding environment to serve man as a basis for survival. However, to protect it, God commanded man to cultivate and guard it. This verse applies to Homo Climaticus thinking. Homo Climaticus also understands that they cannot survive without utilizing what is available in the surrounding environment. This includes not only food and drink but also various other requirements, such as warmth in cold weather (fuel). Thus, environmental resources are used for various human needs. However, Homo Climaticus aims to prevent harm to the environment, striving to preserve it so that future generations can live in a favorable environment. The authors conclude that this verse places Homo Religiosus and Homo Climaticus in comparable situations, as both archetypes share the duty to care for the surrounding environment, ensuring its preservation.

The ownership of the land by God is also stated in Leviticus, where God spoke to Moses on Mount Sinai, saying “The land may be permanently bought or sold. It all belongs to me—it isn’t your land, and you only live there for a little while” (Leviticus, 25:23). In the same chapter, God also spoke to Moses, commanding him and all the children of Israel to work the land for six years, gather its produce, and sow the fields, but rest on the seventh year, during which they should neither sow the land nor prune the vineyards (Leviticus, 25:2–4). These verses again emphasize that God created the land and everything on it, and it belongs to him alone. However, his followers, Homo Religiosus, are allowed to cultivate it, provided they obey God’s commands and care for this “gift.” Caring for God’s given land undoubtedly includes protecting nature. Causing harm to the environment and climate is considered harming God’s creation and is thus seen as disrespectful to the creator. In relation to the duty to rest on the seventh year, specific instructions on how to fulfill this God-given duty of caring for the land he created are observed. The practice of fallowing, as in Moses’ time, is comparable to the current practice of fallowing. The practice of fallowing, as discussed in this manuscript, specifically refers to the sabbatical year (Shmita) observed by the ancient Israelites, as instructed in Leviticus 25:1–7. During this period, the Israelites were commanded to leave the land completely untouched—meaning they did not prepare, sow, prune, or weed the land—allowing the land to rest and regenerate without human intervention. A fallow is an arable field where no agricultural production takes place during the season. The purpose of fallowing is to prepare the field for the next crop by controlling weeds or replenishing soil nutrients (

Agroresursu un Ekonomikas Institūts 2021). The establishment of fallows is also linked to Homo Climaticus thinking, ensuring the rest and improvement of arable land to grow plants that serve as food for humanity in the following years while possibly reducing the consumption of animal-derived products or industrially produced food. In addition, by maintaining fallows, farmers do not need to leave unprofitable fields to establish agricultural land elsewhere, thereby preventing environmental destruction, such as deforestation. Thus, it is concluded that God has assigned a specific duty to Homo Religiosus, which he related to the creation of the land—that is, God created the world in six days and rested on the seventh, which, in the mentioned chapter, is applied to years: work the land for six years but rest on the seventh.

David sang a song to God, stating: “The earth and everything on it belong to the Lord. The world and its people belong to him” (Psalms, 24:1). This verse again points to God as the patron of the land. It clearly states that both the land and everything on it belong to God. Consequently, Homo Religiosus is merely a user of the land. However, they cannot claim it as their own and use it according to their wishes. Homo Religiosus is fundamentally based on trust in God and his prescribed rights. In other words, Homo Religiosus, living on God’s created land, is not entitled to use it for their benefit but to survive and follow God’s will. While Homo Religiosus is committed to the stewardship of the land, this does not preclude the possibility of exploiting the land for profit, provided that such activities serve God’s will and adhere to religious principles. Profit-driven activities must be carried out with the intention of honoring God and ensuring the sustainability and well-being of his creation. This relates to the earlier-mentioned verse from Genesis, indicating that humans are appointed as stewards of the environment by God. God created the land and everything on it; it belongs solely to God, while humans—Homo Religiosus—cultivate, respect, and protect the land given by God. This aspect of Homo Religiosus thinking is closely related to Homo Climaticus thinking, as Homo Climaticus lives in harmony with the surrounding environment, protecting it and striving to prevent any harm already done. The reference to land as God’s property is also observed in the Book of Jeremiah: “I brought you here to my land, where food is abundant, but you made my land filthy with your sins” (Book of Jeremiah, 2:7). This verse describe a scene of divine retribution where God judges the dead and rewards his faithful servants, while also punishing those who have destroyed the Earth. This highlights the theme of divine justice, where each person’s actions, particularly those that cause harm to the Earth, are met with corresponding consequences. This is a clear indication that environmental exploitation is seen as a grievous offense in the eyes of God, warranting severe punishment.

This passage can also be interpreted as a warning to humanity about the moral and ethical responsibility to care for the Earth. It emphasizes that harming the environment is not only a physical act but also a moral transgression that disrupts the divine order. This interpretation aligns with the broader Christian understanding that humans are stewards of God’s creation, and that any damage done to the Earth is an affront to God’s sovereignty.

From this, it can be inferred that God has assigned the responsibility and duty to Homo Religiosus to not destroy and ruin the land given by God.

The Old Testament or Torah includes not only agricultural duties but also ethical norms towards animals and a prohibition on polluting the surrounding environment. It states that the righteous care for the needs of their animals, but the kindest acts of the wicked are cruel (Proverbs, 12:10). This verse clearly expresses that Homo Religiosus, who cannot be unrighteous, also cares for their animals. Meanwhile, in Numbers, there is a command which states that God’s followers must not defile the land where they live because God lives among them (Numbers 35:33–34). This verse refers to environmental pollution, imposing a divine command to preserve the purity and sanctity of the life-sustaining environment.

References to environmental protection are also found in the New Testament, considered the most current collection of religious texts for Christians. For example, Paul’s letter to the Romans states: “In fact, all creation is eagerly waiting for God to show who his children are. Meanwhile, creation is confused, but not because it wants to be confused. God made it this way in the hope that creation would be set free from decay and would share in the glorious freedom of his children. We know that all creation is still groaning and is in pain, like a woman about to give birth” (Letter to the Romans, 8:19–22). This verse reflects the belief that all creation is valuable and awaits redemption, emphasizing the responsibility to care for creation as part of a larger divine plan.

Another example is found in the Book of Revelation: “When the nations got angry, you became angry too! Now the time has come for the dead to be judged. It is time for you to reward your servants the prophets and all of your people who honor your name, no matter who they are. It is time to destroy everyone who has destroyed the earth. The door to God’s temple in heaven was the opened, and the sacred chest could be seen inside the temple. I saw lighting and heard roars of thunder. The earth trembled and huge hailstones fell to the ground” (Book of Revelation, 11:18–19). These verses warn of the destruction of those who harm the Earth, suggesting divine judgment against environmental exploitation and urging the preservation and care of the Earth.

The Torah’s Devarim of Deuteronomy states: “When you lay siege to a city for a long time, fighting against it to capture it, do not destroy its trees by putting an ax to them, because you can eat their fruit. Do not cut them down. Are the trees people, that you should besiege them? However, you may cut down trees that you know are not fruit trees and use them to build siege works until the city at war with you falls” (Deuteronomy, 20:19–20). This verse introduces the law of Bal Tashchit (Heb. בל תשחית), which today is also included in Jewish laws, establishing a general prohibition against unnecessary destruction and the waste of resources.

References to environmental protection are also found in the Qur’an. For example, Surah Al-Baqarah 2:205 states that when people turn away from Allah, they seek to spread corruption in the land and destroy crops and livestock. Allah does not like such evil (

Mufti Muhammad Taqi Usmani 2010). This suggests that people who distance themselves from the Islamic God do not care about preserving the environment and sustainable living, which is displeasing to Allah.

Surah Al-A’raf 7:31 states: “O children of Adam! Take your adornment at every masjid, and eat and drink, but be not excessive. Indeed, He likes not those who commit excess” (

Mufti Muhammad Taqi Usmani 2010). This verse addresses the excessive use of resources. One of the most important goals of Homo Climaticus in addressing environmental problems is to reduce the use of non-renewable resources and practice sustainable agriculture, reducing pollution from waste. This verse clearly expresses Allah’s displeasure with human wastefulness, which results in environmental pollution. Regarding sustainable agriculture and product use, Surah Al-An’am 6:142 states: “And of the fruits and produce (of the earth), He creates gardens, trellised and untrellised; and the date-palm, and crops of different shape and taste (its fruits and its seeds) and olives, and pomegranates, similar (in kind) and different (in taste). Eat of their fruit when they ripen, but pay the due thereof (its Zakat according to Allah’s Orders) on the day of its harvest, and waste not by extravagance. Verily, He likes not Al-Musrifun (those who waste by extravagance)” (

Mufti Muhammad Taqi Usmani 2010).

Allah’s anger towards the destruction of the ecosystem is expressed in Surah Ar-Rum 30:41: “Corruption has appeared on land and sea because of what the hands of people have earned, so He may let them taste part of [the consequence of] what they have done that perhaps they will return [to righteousness]” (

Mufti Muhammad Taqi Usmani 2010). This verse serves as a warning against environmental harm caused by human actions.

4.2. The Value Scale of Homo Religiosus and Its Connection to “Green” Thinking

Previous studies have shown that capital can increase some forms of happiness, particularly when it helps individuals meet their basic needs and achieve personal goals, although this relationship is influenced by various factors and is not universally applicable (

Diener and Biswas-Diener 2002;

Hagerty and Veenhoven 2003;

Clark et al. 2008). Therefore, examining individuals based only on general values leads to the conclusion that capital increases happiness. However, increasing individual capital harms the environment. Various researchers have pointed out that in our era of global ecological crises, the dominant form of valuation is a true reflection of capitalism’s social and environmental degradation, which necessitates profit from the destruction of the planet (

Foster and Clark 2009).

Economic prosperity and growth have been important goals of government policy since the rise of capitalism in early modern history. However, it has been found that rapid growth inevitably leads to the greater use of natural resources and higher pollution emissions, which in turn puts more pressure on the environment. In the modern context, this connection immediately raises questions about potential conflicts between two strong current trends—the market-oriented economic reform process now widely accepted globally and environmental protection (

Munasinghe 1999).

Although there is debate among researchers about whether individual capital increases happiness, studies show that national income indeed contributes to national happiness, which is consistent with the theory of absolute utility. This arises from the fact that citizens of poorer countries have unmet needs that can be satisfied with various goods and services, reducing the marginal utility of income (

Hagerty and Veenhoven 2003).

The authors conclude that people’s happiness is often related to their income level because it allows them to purchase necessary and desired goods and services, simultaneously improving their quality of life, including healthcare. However, capital accumulation is associated with various environmental problems, such as pollution and gas emissions. Therefore, in the pursuit of worldly values and the desire to become happier, people pose threats to the environment.

Conversely, the Old Testament or Torah includes teachings from God and followers, emphasizing the need to refrain from pursuing worldly values. For example, “Give up trying so hard to get rich. Your money flies away before you know it, just like an eagle suddenly taking off” (Proverbs, 23:4–5). Similarly, in Ecclesiastes, it is mentioned that whoever loves money never has enough; whoever loves wealth is never satisfied with their income. This too is meaningless (Ecclesiastes, 5:10).

The New Testament also includes advice against accumulating capital, encouraging the accumulation of spiritual values instead. For instance, in the Gospel of Matthew it is stated: “Don’t store up treasures on earth! Moths and rust can destroy them, and thieves can break in and steal them. Instead, store up your treasures in heaven, where moths and rust cannot destroy them, and thieves cannot break in and steal them. Your heart will always be where your treasure is” (Gospel of Matthew, 6:19–21).

The Qur’an also suggests that this worldly life is nothing but play, amusement, luxury, mutual boasting, and competition for wealth and children. It is like rain that produces vegetation, bringing delight to the farmers; then it dries up and you see it turning yellow; then it becomes debris. In the Hereafter, there is severe punishment or forgiveness from Allah and approval, whereas the life of this world is nothing but a deceiving enjoyment (

Mufti Muhammad Taqi Usmani 2010). This verse highlights the transient and deceptive nature of worldly life and contrasts it with the permanent reality of the afterlife, encouraging believers to prioritize their spiritual commitments over material gains.

The authors note that from the mentioned verses, it follows that Homo Religiosus does not find happiness in material gains or capital. Homo Religiosus strives for spiritual gains. Therefore, this archetype, like Homo Climaticus, does not place material values above the land created by God and everything on it, resulting in less environmental degradation. Comparing Homo Religiosus and Homo Climaticus from this perspective, it is concluded that both archetypes place higher value on the environment rather than material benefits obtained by harming it.

4.3. The Priority Scale of Homo Climaticus and Homo Religiosus

The main difference between Homo Climaticus and Homo Religiosus concerning the environmental aspect is the top point of their priority scale. The previous subsection concluded that both archetypes value the environment above material benefits, but the very top of this scale features different priorities. For Homo Religiosus, the main priority is God, with everything else created by God following afterward. For Homo Climaticus, the priority is humanity, with the goal of protecting the environment to ensure favorable living conditions for humans.

The Gospel of Matthew contains the words of Jesus: “Love the Lord your God with all your heart, soul, and mind. This is the first and most important commandment” (Gospel of Matthew, 22:37–38). This verse clearly expresses that Homo Religiosus’ highest priority is love for God.

This difference in priority scales significantly influences Homo Religiosus’ view of the environment, namely, that the environment is protected as long as it serves God’s glory. The sixth to ninth chapters of Genesis describe the destruction of the world by the flood and its repopulation due to human wickedness. “The Lord saw how bad the people on earth were and that everything they thought and planned was evil. He was very sorry that he had made them, and he said, “I’ll destroy every living creature on earth! I’ll wipe out people, animals, birds, and reptiles. I’m sorry I ever made them”” (Genesis. 6:5–7). Further chapters describe how Noah, who found favor with God, built a massive ark, bringing pairs of every kind of animal and creature—male and female—so they could repopulate after the world’s destruction. Then, God destroyed everything on the Earth with a flood, allowing only those in Noah’s ark to survive (Genesis, 7–9).

Another example is found in Genesis, which describes the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah. It states that the Lord’s (God’s) wrath has been provoked by the wickedness of the inhabitants of these cities, and he sent two of his angels to destroy them (Genesis, 19:13). The destruction is described as follows: “and the Lord sent burning sulfur down like rain on Sodom and Gomorrah. He destroyed those cities and everyone who lived in them, as well as their land and the trees and grass that grew there” (Genesis, 19:24–25).

From these stories, it can be inferred that Homo Religiosus’ main priority is to live according to God’s commandments, honoring God. Additionally, the consequences of not following these commandments and acting wickedly are evident. Homo Climaticus does not only consider the actions of surrounding individuals, while seeking to ensure environmental problem-solving and protection, whereas Homo Religiosus cultivates and protects only the land that is pleasing to God. God, who is fundamental to Homo Religiosus, is willing to destroy the Earthand everything on it if the people living on it do not honor God.

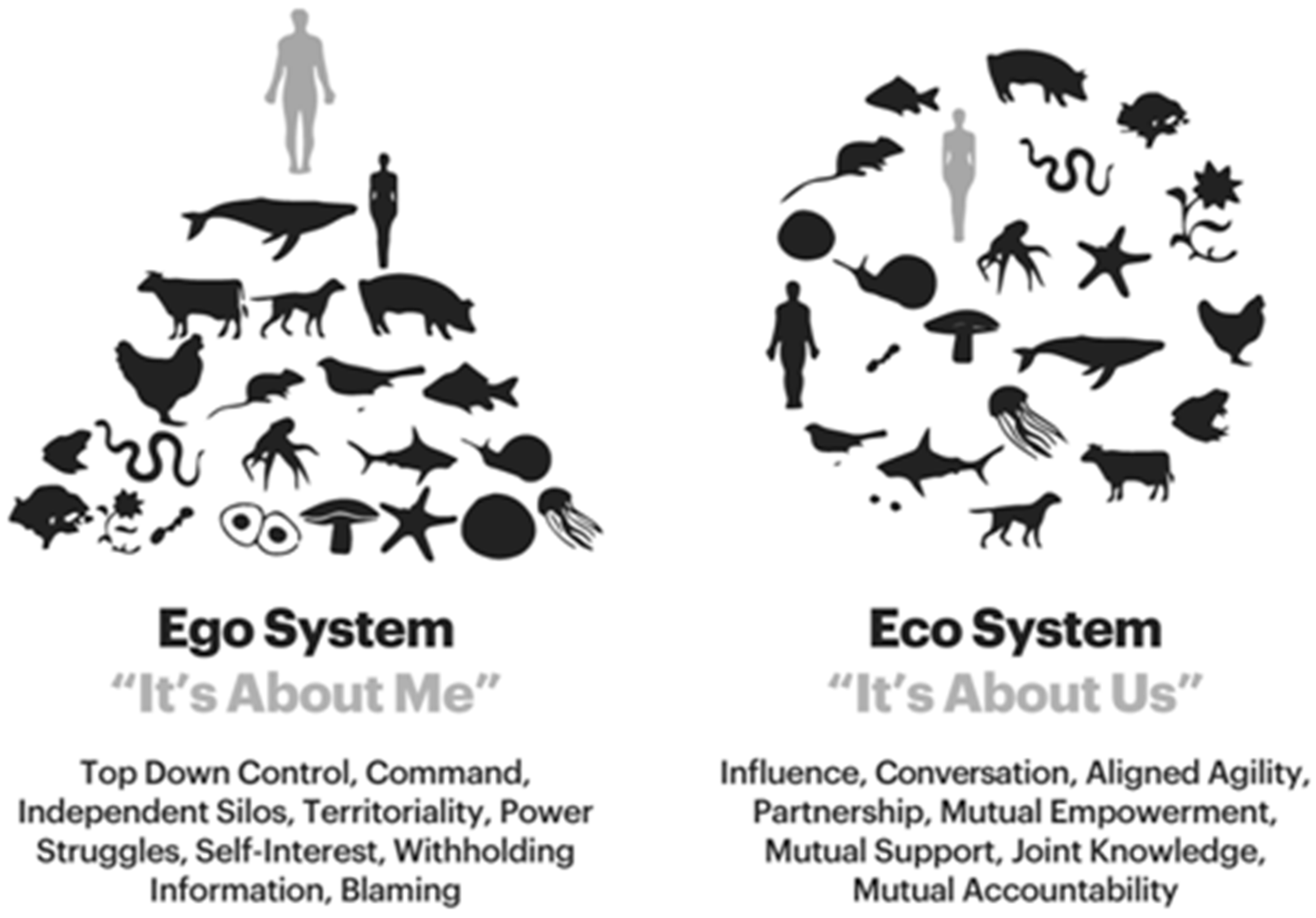

Continuing with the priority scale, the status of the individual as a person should be examined. As previously mentioned, when God created the world, he also created humans in his image—male and female. Then, God blessed them and said: “Have a lot of children! Fill the earth with people and bring it under your control. Rule over the fish in ocean, the birds in the sky, and every animal on the earth” (Genesis, 1:28). Thus, it is concluded that God placed himself as the priority for Homo Religiosus, followed by humans, who have the duty to subdue everything on God’s created earth. Conversely, as depicted in the image in

Appendix A, Homo Climaticus lives in equality and harmony with the surrounding environment. Homo Climaticus’ priority is humanity, making its primary goal to ensure a favorable environment for humanity to live in. Homo Climaticus does not concern itself with whether a person lives according to rules unrelated to environmental preservation.