2. Alphonse Favier and Decheng Workshop

In 1862, a 25-year-old Lazarist missionary named Alphonse Favier 樊国梁, CM (1837–1905), arrived in Beijing. Favier had studied architecture and music in France before being recruited by Bishop Joseph-Martial Mouly, C.M. (1807–1868), Vicar Apostolic of Beijing at that time. Favier served as the primary coordinator of Christian construction and artistic activities during his stay in Beijing from his arrival until his death in 1905 (

Clark 2019). The Chinese nickname chosen by Alphonse Favier, 国梁 or 國梁, literally means “Pillar of the Country.” This name aligns well with his role as an architect and one of the most significant supporters of his community in Beijing. Favier’s ecclesiastical journey saw him ascend the ranks of the clergy. Around 1863, he took on the position of procurator for the Lazarist province in Beijing. This entailed Favier to become primarily responsible for securing financial resources for the apostolic vicariate. His trajectory continued with significant appointments, including titular Bishop of Pentacomia and Coadjutor Vicar Apostolic of Beijing in 1897, becoming the Apostolic Vicar of Beijing from 1899 until his death in 1905. Certainly, during this time, Beijing operated as an apostolic vicariate rather than a diocese, with Favier serving as its leader. He is enduringly remembered as the ‘Bishop’ of Beijing in his birthplace (

Sweeten 2020, p. 51, note 72).

In 1886, Maurice Jametel (1856–1889) published one of the earliest, yet least known, books on Beijing cloisonné (

Jametel 1886). This book narrates the story of the artistic collaboration between Favier and the “Tchen-to” (Decheng 德成) workshop. Jametel, a distinguished translator and diplomat, served in his twenties in Beijing, Guangzhou, and Hong Kong from 1878 to 1880. Unfortunately, his health declined during this period, leading to his return to Europe (

Schefer 1890, p. 71). In Paris, he served as a lecturer of Chinese at the École des langues orientales vivantes in 1886 and later became a full professor until his early death in 1889. Before 1881, while residing in Beijing, he visited the Decheng cloisonné workshop, having ordered a couple of 20 cm diameter bombonieres. Impressed by the high quality of the result, he became intrigued and sought to learn more about the workshop. Jametel was enthusiastic about the cloisonné produced by Decheng:

“The blue backgrounds certainly did not have the incomparable brilliance of their elders of the Ming period; but the liveliness of their tints gave them a value almost equal to the blue backgrounds of the pieces of Kangxi and Qianlong. The other colors were also noticed by real qualities. As for the partitions, they sketched exactly the contours of the design and in addition formed, on the backgrounds, arabesques which very fortunately raised their monotony. The enamel was applied in a thick layer of uniform density, and its surface polished like a mirror.”

As mentioned, the Decheng workshop was established in 1860, likely at the end of the Second Opium War, and had to close around 1935. Its founder and owner, Jia Derun, hailed from the present-day province of Shandong. Coming from a peasant family, Jia Derun completed his education and established his own workshop, reviving cloisonné during the Xianfeng period. Initially, the workshop crafted mandarin insignias or buttons and gold-plated objects. Later, it repaired cloisonné items and eventually started producing its own cloisonné (

Zhou 2022, pp. 56–57). Precisely in Shandong, the native province of Jia Derun, lies the Boshan district, the primary source of metals for cloisonné production. Some of its residents collaborated with missionaries to develop glass and enamel techniques, benefiting from European knowledge (

Wu 1994, p. 342). Jametel narrates a segment of Jia Derun’s personal journey and highlights the fact that Favier played a pivotal role in his success:

“My host, for a Chinese, was a true revolutionary; instead of working as his father had worked, who himself worked as his own father had worked, he willingly made excursions off the beaten track of routine, under the skillful direction of Father Favier; and thanks to the Saint Lazarist, the brand of Tchen-to (Decheng) has become the best, I would even say the only good one in Beijing, because the other enamelling workshops that I visited, in the capital of the Son of Heaven, only make common objects, while my host’s workshop only produces art objects and even real masterpieces. Besides, Tchen (Jia) does not appear ungrateful to his benefactor: You see, he told me, without the spiritual father Fou (Fan)—the Chinese name of Father Favier—I would never have been able to do things to the taste of Europeans, who are in fact my only customers. It was on his advice that I made these sleeve buttons that your compatriots love so much, these little plates where you collect, I have been told, the ashes from your rolls of tobacco, -cigars-, these round boxes for your sweets, flat plates, bottles and vases with big bellies, in short everything that our ancestors made very little or even not at all.”

This information, which has not been considered until now, is crucial for the history of the development of the Decheng workshop and, more broadly, for understanding this transformative period in the history of Chinese cloisonné. Jametel provides insights into Decheng’s success as a worthy heir to the luxury cloisonné of the Qing tradition, but also as the first workshop capable of adapting to the tastes of the Europeans, who were Jia Derun’s “only customers.” These achievements resulted from creative interactions and the exchange of knowledge between Favier and Jia Derun. Jia Derun even referred to Favier as his “spiritual father”, possibly indicating that he had converted to Christianity, as I will discuss later.

Decheng was also the first cloisonné workshop in Beijing whose participation in a World Exhibition is documented, specifically at the 1878 Paris World Exposition (

Zheng 2020, p. 27;

Zhou 2022, p. 62). In my opinion, Favier was likely the one who persuaded Jia Derun to participate. In the section dedicated to goldsmithery at that exhibition, it was stated that only “some families” from Boshan, Shandong, “who possess the secret of colors, several of which are now lost”, produced cloisonné, and that “some manufacturers even learned from one of our missionaries currently in Beijing the process of gilding with a battery” (

Chine. Douanes maritimes 1878, p. 14;

Les merveilles 1878, p. 254). Undoubtedly, one of those families was Jia Derun and his sons, as the Decheng workshop exhibited two cloisonné vases two meters in height at that exposition (

Reports 1880, p. 31). On the other hand, the French missionary “currently in Beijing”, as referenced in the text, was in fact Favier. This is confirmed by the following information published in 1889: “some manufacturers even learned from a Lazarist missionary currently residing in Beijing, Monsignor Abbe Favier, to use a battery for gilding and greatly improve the designs of their cloisonnés” (

Fauvel 1889, p. 52).

These mentions are crucial for understanding that the collaboration between Favier and the Decheng workshop resulted in mutual benefits, in this case, an exchange of technical knowledge, where Favier taught Jia Derun the process of gilding through galvanic gold plating or electroplating. According to recent research, the earliest use of electroplating in Beijing was around 1890 by the Tianli workshop (

Zhou 2022, p. 47). However, as we can see, electroplating began to be used in Beijing before 1878, thanks to Favier’s initiative. In fact, Jametel comments on this topic, stating that Jia Derun “has replaced the old gilding methods” with electroplating,

“but the workers, [who are] enamellers, do not like to handle the batteries. They pretend that these ‘diabolical machines’ give off poisonous vapours, but it is not true. Notwithstanding, Tchen (Jia) finds too many advantages in electroplating to look at it so closely; and all the pieces that come out of his workshop are silvered or gilded by the diabolical batteries. In general, cloisonnés are gilded on blue backgrounds, and silvered on black backgrounds.”

In addition to the innovation using galvanic gold plating, Favier assisted Jia Derun in improving the precision of cloisonné designs. This precision involved the ability to produce copper wires of around 0.2 mm thick. The pigments could also be grounded much finer, enhancing the color. These innovations were possible through the introduction of Western techniques and machinery (

Zhou 2022, p. 190). Until now, it was unknown that Favier had assisted Decheng workshop in implementing such improvements. Additionally, in the conversation between Jametel and Jia Derun, technological differences between Europe and China regarding enameling came to light. Jia Derun asked Jametel:

“-Well, did my humble factory interest you?

-Enormously.

-However, you must have much more beautiful ones in the West, where there are so many machines of extraordinary antiquity…

Politeness prevented me from telling Tchen the truth and from teaching him that in the West cloisonné enamels are considered as productions of an art still in its infancy, the triumph of which is painted enamel, the only one capable of giving a body with conceptions of genius.”

This testimony is truly remarkable and sincere, especially considering that the French related to the mission civilisatrice (civilizing mission) are often accused of chauvinism. The dominant technique in Europe since the 16th century was painted enamel. This situation had not changed in the 19th century, and it was through the study of Chinese cloisonné that cloisonné was revived in Europe. Jametel also expresses his views on the quality and price of Decheng’s products and the possibilities they have in the European market:

“I said above that Tchen had at present numerous imitators; but the latter harm him very little: they produce dozens of bottles and boxes of all shapes, with dull enamels, almost always disfigured by a very malignant smallpox, with thick and heavy partitions. It is these objects, without artistic value, which invade our department stores where a piece bearing the Tchen-to mark engraved on its bottom has never entered, and for good reason. Tchen’s artistic productions are expensive, even in Beijing, while these junk objects are almost for nothing. A pretty pair of cufflinks, which Tchen only makes to order, costs 20 francs, while you can get them in cloisonné factories for 10 and even 5 francs per pair. These admirable round candy boxes, which were the cause of my visit to Tchen, cost in his house 75 francs, while, if you have little taste for beautiful things, and if you are convinced that the smallpox of cloisonné is not contagious, you can get larger ones for 20 francs from its competitors.”

Here, Jametel emphasizes a well-known fact today: Decheng’s products were expensive; it was a luxury firm. Additionally, in Europe, knowledge about Chinese art had not developed much and the public preferred cheap decorative items or trinkets to adorn their homes. According to the quoted text, these products had manufacturing defects, such as what he jokingly calls “smallpox”, meaning the black spots seen on the surface of cloisonné as a result of air bubbles formed due to poor firing and being filled with dirt. Decheng’s products, though expensive, were regarded as the best in the market; those from any other workshop are deemed vulgar, dented, full of black spots, and have “equally less artistic” partitions (

Jametel 1886, p. 5). Jametel vaguely refers to the workshop mark of Decheng, “the Tchen-to mark engraved on its (the object’s) bottom”. Decheng had two types of marks with the characters 德成, but many objects produced by this workshop are unmarked to avoid damaging the enamels, and personalized commissions were usually left unmarked (

Zhou 2022, p. 63). Perhaps for this reason, none of the religious objects related to the collaboration between Favier and Decheng are marked. It was also pointed out that Decheng’s objects were easily recognizable because their bases never presented blue counter enamel, which was used by poor-quality producers to conceal the low-quality copper alloy with a high lead content that would turn gray. Instead, Decheng used a good-quality copper, which was then gilded with electroplating (

Jametel 1886, p. 20).

Jametel concludes that Favier, a “Lazarist of good taste, has brought about a complete revolution in Beijing enameling in terms of form” (

Jametel 1886, p. 19). He clarifies this appreciation by stating that while wandering through the shops of Liulichang (琉璃廠)—the book district in Beijing where the Decheng workshop was located—he found a Chinese booklet on ancient cloisonné. This booklet had 37 plates featuring different shapes of objects, of which Decheng and its imitators used only 5 as models. This indicates that Favier and Decheng utilized a few old shapes and created new typologies in China adapted to the European audience, who were their “only customers”. The new objects produced by Decheng were primarily decorative souvenirs in Western shapes, male accessories, and Christian religious objects.

In 1897, Favier published his renowned monograph on Beijing for the first time. In this work, he refers to various Christian cloisonné pieces and attests that cloisonné “has made significant progress over thirty years […] today we can achieve color degradation within the same partition (

cloison)” (

Favier 1897, p. 433). This comment allows us to place the beginning of Favier and Decheng’s collaboration around 1867 if Favier’s own words are accurate. Jametel indicates that the Decheng workshop was on the streets near “Léou-li-tchan (Liulichang), the book district” (

Jametel 1886, p. 5). This information aligns with Decheng’s labels, which state that the workshop was located in the middle of Yangmeizhu Xiejie 楊梅竹 Street (

Quette 2011, p. 28, Figure 2.21;

Zhou 2022, p. 65, Figure 3-1-13). The workshop was close to the legation quarter and a 30 min walk from Nantang, the former Southern Jesuit Residence. In the church of this building complex, Favier had undertaken his first major restoration in 1863–1864 (

Favier 1865, pp. 494–95). Furthermore, Nantang was the cathedral of Beijing until the construction of the Second North Church in 1865–1867 (

Clark 2019, p. 58;

Sweeten 2020, p. 118). Furthermore, on 30 April 1900, Louis Gaillard, SJ (1850–1900), wrote that he was staying at the French Legation in Beijing, and from there,

“A Lazarist leads me into a neighbouring house of Christians, manufacturers of very beautiful cloisonné, especially for Europeans. The setup is very basic, but the production is quite considerable. This is the second house in Beijing. The first in importance (non-Christians) has sent 300,000 francs worth of objects to your Exhibition.”

It is quite possible that if a Lazarist—a companion of Favier—brought Gaillard from the French Legation to “a neighboring house of Christians” that produced cloisonné, which would be the workshop with which the Lazarists collaborated, i.e., Decheng. The non-Christian (

païen) workshop mentioned as the main producer in Beijing could be Tianli. It is certain that Jia Derun, the founder of the Decheng workshop, died in 1900, since his epitaph is well known, and this information is confirmed by his descendants. According to the researcher who collected this information, Jia Derun’s death might be related to the Boxer Rebellion since he primarily supplied Westerners (

Zhou 2022, pp. 60–61). I completely agree with this observation, but I would go further. Jia Derun had converted to Christianity, as attested by Gaillard when referring to the Decheng workshop as a “house of Christians”. I also noted earlier that Jia Derun referred to Favier as a “spiritual father” in his interview with Jametel.

In my opinion, the destinies of Alphonse Favier and Jia Derun were intertwined for most of their professional lives. Both were of similar age and crossed paths early in their careers, as Jia established the Decheng workshop around 1860, and Favier arrived in Beijing in 1862. Coming from small towns in France and China respectively, they were both entrepreneurs, began collaborating around 1867, thrived together and became representatives of age-old traditions that culminated with their works. Favier was the heart of the Catholic mission in China, a leader in the French Protectorate, or the ‘civilizing mission,’ and a representative of 19th-century European historicism. Jia was the last heir of the Ming and Qing cloisonné artistic traditions, maintaining the quality level of cloisonné and “never lowering his noble head for a moment” (

Zhou 2022, p. 54). Favier was the ‘hero’ of the Catholic resistance in Beijing during the Boxer Rebellion in 1900. Jia Derun died in those circumstances, perhaps murdered by the Boxers due to his professional connection with Favier and his Christian faith.

3. Masterpieces Unveiled: The Collaborative Legacy of Favier and Decheng Workshop

According to Jametel, the pinnacle of Decheng’s cloisonné craftsmanship, observed during his visit to the Decheng workshop between 1878 and 1880, was a chalice—also referred to as a ciborium—“crafted for Favier and overseen by him”. This exquisite piece utilized eleven colors and featured a distinctive inscription in gothic characters (

Jametel 1886, p. 20). This Gothic Revival chalice model shares many similarities with specimens currently housed in Saint Peter’s Basilica Museum in the Vatican (acquired in 1880) and the Catharijneconvent Museum in Utrecht (inv. ABM m2026a), among others. The Utrecht chalice was sent by Favier himself in 1899 to Henricus van de Wetering, Archbishop of Utrecht and Primate of the Netherlands. However, this chalice could have been crafted around 1880, as its original design predates the production of the chalice preserved in Saint Peter’s Basilica Museum, as I will explain. The chalice of Notre Dame de Paris (NDP0081) and its paten are identical to the chalice and paten of Utrecht. These chalices, along with other specimens held in Missions Étrangères de Paris and Sacre Coeur de Paris, meet the quality standard described by Jametel, adhere to the same Gothic Revival form, and were enameled with eleven colors—turquoise blue, dark blue, black, white, light green, dark green, yellow, beige, pale pink, red, and violet.

The earliest securely dated piece of Chinese Christian cloisonné is the chalice that missionaries from the Apostolic Vicariate of Beijing—including Favier—gifted to Luois-Gabriel Delaplace, CM (1820–1884) for the 25th anniversary of his episcopal consecration in 1877. This artifact is currently housed in the Musée départemental d’art religieux in Sées, France (

Parada López de Corselas and Vela-Rodrigo 2021) (

Figure 1).

Delaplace’s chalice features intricate floral decoration. Indeed, Decheng’s specialty lies in flowers, showcasing a more naturalistic, animated, and virtuoso style compared to those from the mid-Qing period (

Zheng 2020, pp. 27–28). For instance, the blue bellflowers on Delaplace’s chalice are identical to those on the underside of a plate bearing the Decheng mark

1. The paten of the chalice gifted to Delaplace is inscribed with 耶穌吾牧且吾真食憐視我等 (“Jesus is my shepherd and my true food, he has shown me mercy”, which is based on Psalm 23:1), the same inscription adorning the paten of Favier’s chalice preserved in Utrecht (

Figure 2).

This inscription is also featured on the paten of the chalice from Notre Dame de Paris, which is identical to the Utrecht paten. All these pieces were crafted in the Decheng workshop between 1877 and around 1880.

The chalice in the Museum of Saint Peter’s Basilica was acquired in 1880 and donated by Mariano Rampolla del Tindaro (1843–1913) to the former Treasury of St. Peter’s (

Orlando 1958, pp. 55–56). This chalice shares the same shape and nearly identical decoration as Favier’s chalice preserved in Utrecht, although it simplifies some of its elements (

Figure 3).

The chalices from the Vatican and Utrecht include angels with unfurled cartouches, but while in the Utrecht chalice, the cartouches bear inscriptions, in the Vatican chalice, they have been haphazardly filled with scrolls. This demonstrates that the Utrecht chalice is closest to Favier’s original design, and Saint Peter’s chalice simply copied elements from this design for their purely decorative value, even without a full understanding. Saint Peter’s chalice is highly relevant because it provides the year 1880 as a terminus ante quem for the creation of this typology—although several chalices which follow this shape continued to be made until the 1890s. On the other hand, this chalice could be linked to the relationship between Favier and Mariano Rampolla del Tindaro, Secretary of State of the Vatican and secretary for Oriental affairs of the Propaganda Fide under Leo XIII (r. 1878–1903). Rampolla was Favier’s primary contact at the Vatican in numerous negotiations related to the situation of the Catholic Church in China (

Clark 2019, pp. 35–36, 52–53, 119).

Regarding the Utrecht chalice, it was sent by Favier in 1899 to Henricus van de Wetering, Archbishop of Utrecht and Primate of the Netherlands. Favier presented this gift to van de Wetering in his role as the consecrator of Ernest-François Geurts (1862–1940), CM

2. Geurts was consecrated in St. Jans cathedral in Den Bosch (‘s-Hertogenbosch, Bois-le-Duc) on 4 February 1900 by Henricus van de Wetering, assisted by Wilhelmus van de Ven, bishop of Den Bosch, and Casimir Vic, CM, bishop of eastern Jiangxi in China

3. Years later, in 1903, van de Wetering donated the chalice to Saint Anthony church in Utrecht. According to this church’s record, it was “received from His Serene Highness Archbishop Mgr. H. van de Wetering for the treasury of St. Anthony, a chalice, artful Chinese enamel cloisonne, that was offered to him by HSH Mgr. Favier as Bishop consecrator of Mgr. Geurts”

4. Favier presented the Utrecht chalice to van de Wetering in his role as the consecrator of Geurts because Favier himself had advocated for Geurts’ appointment as the Vicar Apostolic of Eastern Chi-Li (Tche-li). In 1899, Alphonse Favier assumed the position of vicar general of Beijing, succeeding Sarthous. Favier put forth a proposal to partition the eastern portion of the territory under his jurisdiction, creating a new vicariate in that area. He recommended the appointment of the Dutch priest Frans Geurts, CM, as the Vicar Apostolic of this newly established vicariate, with the stipulation that future vicars were also Dutch. The objective was to enlist more Dutch missionaries for the mission in China and to secure increased financial support from the Netherlands for the mission. The chalice presented by Favier to Geurts as a gift for Wetering, Archbishop of Utrecht, received commendatory remarks from the Guild of Saint Bernulphus of Utrecht. During its annual meeting of 1900, this guild deemed the piece to be a “highly curious chalice […] made a few years ago by a Chinese artist after a design by mgr. Favier in Beijing. The cell-enamel, with which the chalice is decorated, aroused general admiration. It equals the best enamel-works, ever originated from Limoges” (

Sint Bernulphus-Gilde 1900, p. 12).

In the Treasury of Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris, there is a “so-called Chinese” chalice and its paten. Both pieces are in fact Chinese. They are identical to the chalice and paten designed by Favier and preserved in Utrecht, with only slight variations in some colors and various details in the execution of the faces or hair of the figures. The rim of the paten and the cup of Notre Dame chalice bear the mark of Poussielgue-Rusand, and for this reason, they have been attributed to this French goldsmith

5. However, this is undoubtedly due to the fact that the rim of the paten (not the central enamel roundel) and the cup of the chalice were replaced in Paris, but the entire original work is the result of the collaboration between Favier and Decheng workshop in Beijing.

The chalices from Utrecht and Notre Dame de Paris correspond to Jametel’s description during his visit to the Decheng workshop between 1878 and 1880 of the work designed by Favier that impressed him the most: the chalice or ciborium depicting the Last Supper. Jametel described it as being “rendered with a perfection as great as that of painted enamels. Around the perimeter of this ‘painting’ is inscribed a verse from the holy scriptures, in gothic characters” (

Jametel 1886, p. 20). Indeed, both the chalices from Utrecht and Notre Dame depict Jesus blessing the bread in the Last Supper in a central position on the base, encircled by an inscription in gothic characters: “

Se nascens dedit socium. Lucas. Convescens in edulium. Mattheus. Se moriens in pretium. Johannes. Se regnans dat in praemium. Marcus” (In birth man’s fellow-man was He. Luke. His meat while sitting at the board. Matthew. He died, our ransomer to be. John. He reigns to be our great reward. Mark) (

Figure 4).

The inscription on the chalices combines four verses from Thomas Aquinas’ hymn “Verbum Supernum Prodiens” and the Latin names of the Evangelists. Each section of the inscription corresponds to the closer image depicted on the base, with the Evangelist names corresponding to the Four Living Creatures. The hymn verses align with the Nativity, the Last Supper, the Crucifixion, and Jesus in Heaven portrayed as a Chinese emperor. The angels depicted on the cup bear cartouches forming the inscription “Venite/ bibite/inebriamini/carissimi” (Come, drink, let us inebriate, my dears!), a fragment taken from the Song of Solomon 5:1.

The Saint Peter’s chalice lacks inscriptions and portrays the same scenes as the Utrecht chalice, with the notable difference of presenting a complete depiction of the Last Supper, including not only Christ but also the Apostles. In Saint Peter’s chalice, the representation of Jesus in Heaven as a Chinese emperor is replaced by the Resurrection, depicting Christ emerging from the Sepulchre. The Saint Peter’s paten features the Crucifixion, surrounded by an inscription in gothic characters, “Bone pastor panis vere Iesu nostri miserere” (Good shepherd, true bread, Jesus, have mercy on us), taken from the last two verses of Lauda Sion, composed by St. Thomas Aquinas for the feast of Corpus Christi. This inscription is inverted due to the copying process from the original model.

Together with these examples, it should be considered the chalices kept in Missions Etrangères de Paris and the Sacré Coeur in Paris (

Figure 5).

Both are shaped in the same typology as the chalices in Utrecht and Notre Dame. The Missions Etrangères de Paris chalice features abundant floral and animal decoration on a pink background. The only scene included on the base is the Crucifixion. Likewise, in the decorative band located at the bottom of the base, the row of animals is repeated, which is present in all chalices of this type. The chalice in the Sacré Coeur in Paris is very close to the Missions Étrangères de Paris’ one. The documentation from the Sacré Coeur indicates that this chalice was donated by the Fathers of the Mission, China Province, and that was crafted by an individual named Favier, leading to its attribution to François Favier (born 1800), a member of a well-known family of silversmiths from Lyon (

Benoist 1992, p. 1090;

Berthod 1995, pp. 204, 206, Figure 193). However, once again, it is a work designed by Alphonse Favier in Beijing. This chalice also features cartouches on the cup, but they are inscribed in Mandarin rather than Latin. On the base, instead of depicting Jesus instituting the Eucharist, Jesus revealing his sacred heart is portrayed. The paten depicts the Crucifixion within a landscape adorned with circles and stars in the sky, a recurring motif in the cloisonné pieces conceived by Favier. Béatrice Quette dated the Missions Etrangères chalice to the period between 1750 and 1850 (

Quette 1997, p. 157). However, in my opinion, all the mentioned chalices can be dated around 1880, or at least this typology would have been created before that year and continued to be used until the end of the century. All these pieces are interconnected by their shape, drawing style, and color choices. They use the same neo-Gothic shape, eleven colors—including graded hues—and the characteristic stars-and-circles pattern which was only used in that period by Favier and Decheng.

As we have seen, in the 1880s, Favier developed, in collaboration with the Decheng workshop, pieces featuring Christian figures and scenes. He generally used models from Historicism—as he did in many of his churches—which he combined with decorative motifs, symbols, or inscriptions in dialogue with the Chinese tradition. In my opinion, in this context the plaque from the Vatican Museums representing the

Delivery of the Keys to Saint Peter (inv. 70530) can be placed (

Figure 6).

This plaque took Raphael’s famous tapestry cartoon as a model and was a gift for the 50th-anniversary priest ordination of Pope Leo XIII in 1888. The mountains in the landscape have been modified to give them a Chinese appearance. The border of this plaque features the characteristic flower and insect decoration and shaded colors of the Decheng workshop, and the roundels with the Four Living Creatures are identical to those on the Utrecht chalice. These same roundels are present in two Gothic Revival wall crosses belonging to Honolulu Museum of Arts (inv. 7623.1) and a private collection (

Parada López de Corselas 2022, p. 110, Figure 11), which can also be dated to around 1880 and linked to the collaboration between Favier and the Decheng workshop (

Figure 7).

In his 1897 book on Beijing, Favier references the primary altar of Saint Joseph Church, also known as Dongtang or East Church, which he reconstructed between 1879 and 1884 under Delaplace’s directive. The altar, crafted in 1884 from Naples marble, was adorned with “colonnettes and various motifs in cloisonné enamel” and financed through contributions from “M. de Semallé, Chargé d’affaires of France” (

Favier 1897, p. 303). Favier’s account finds support in the writings of Count galvani (1849–1936) himself, who authored a book chronicling his experiences in China and offering supplementary insights: “being Chargé d’affaires [in Beijing], I had wanted to contribute to the decoration of the church (Dongtang) and I had had To-Tchang (Decheng), the best artist in cloisonné, execute the door of the tabernacle of the main altar” (

Semallé 1933, p. 176). This account reaffirms the esteemed reputation and superior quality of Favier-Decheng cloisonné. In 1884, the prominent cloisonné workshops in Beijing included Tianli, Tianruitang, Decheng, and Dexingcheng. It is worth noting that both Semallé and Jametelregarded Decheng as the finest among them. Dongtang was set on fire by the Boxers in 1900, and the cloisonné tabernacle was melted down.

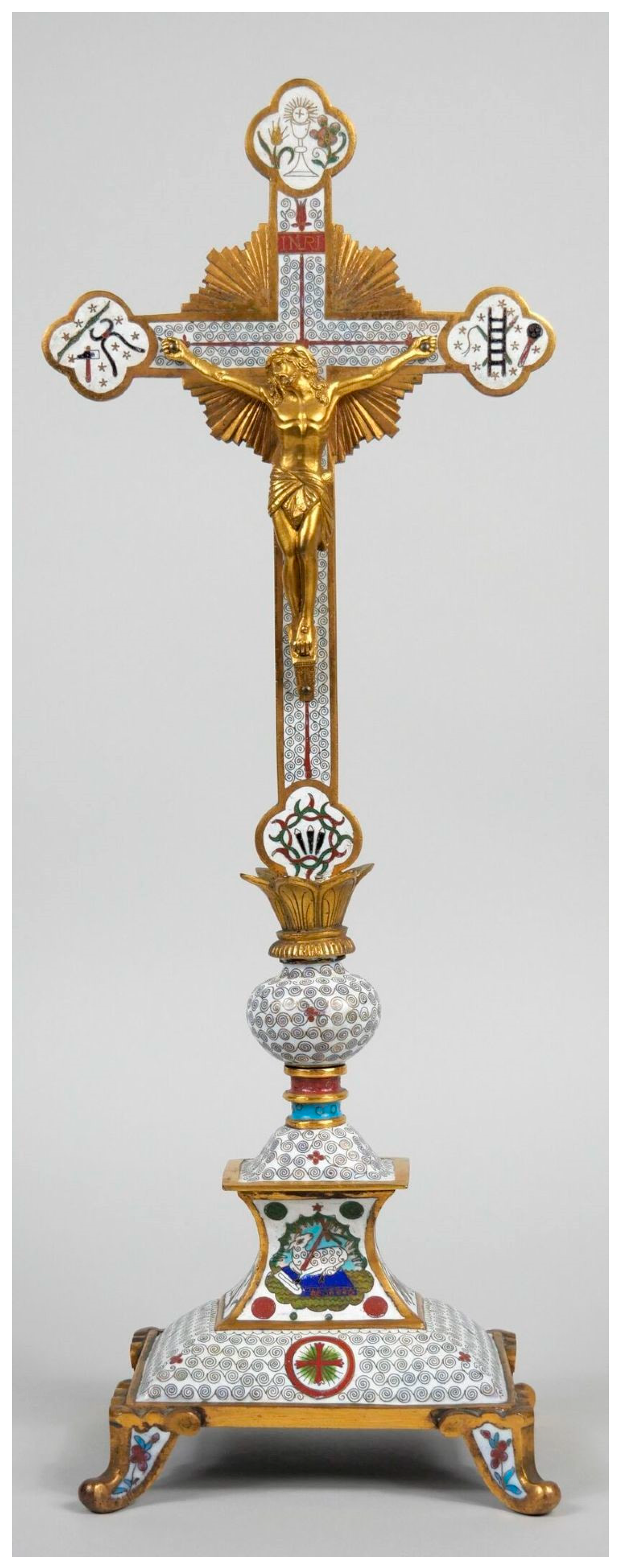

The fusion of the techniques of shaded ’cloisonne enamel and en ronde bosse (encrusted) enamel was the ultimate challenge for Favier. In 1897, Favier reported the creation of “the most perfect” cloisonné and en ronde bosse work, which was crafted under his supervision.

“The enamellers have improved their art, and the new products are more careful than the old ones, today we can degrade the colours in the same partition. The most perfect thing of this kind has been executed is a cross recently sent by the Beijing Mission to His Holiness Leo XIII, for his episcopal jubilee. It measures 1 m 50 [cm] high, and all the arabesques, volutes, decorations are enamelled in the round (en ronde bosse); it is a most difficult task and one which has been admirably succeeded; five workmen working even at night, took six months to execute it.”

Thankfully, Favier supplemented this clarification with an engraving of the cross gifted to Pope Leo XIII on his then-recent episcopal jubilee, commemorating the 50th anniversary of his episcopal ordination in 1893. This cross corresponds to the impressive altar cross currently housed at the Vatican Museums (inv. 119968), which was exhibited in 2019 as part of the “Beauty Unites Us” exhibition at the Forbidden City (

Beauty Unites Us 2019, cat. Nr. 3). The Vatican Museums initially dated it to the early 20th century; however, it can be verified now that the cross was crafted around 1892 at the Decheng workshop in Beijing under Favier’s supervision (

Figure 8).

4. The Beitang Cloisonné Workshop in Beijing

Favier never explained in detail where the cloisonné workshops he collaborated with were located. We know he worked with Decheng from around 1867. As we have just seen, in the spring of 1900, Gaillard was taken by a Lazarist to the Decheng workshop, a “house of Christians” near the legation district. This confirms that initially Favier and his Lazarist companions subcontracted cloisonné work to Decheng before establishing a proper Church workshop. In the new Beitang complex (Third Northern Church, inaugurated in 1888), a cloisonné workshop began to take shape, initially serving as a sales showroom that subcontracted products to Decheng. In his plan of the Beitang complex, Favier included the “

magasin chinois” (Chinese store; letter N), the “

magasin de l’imprimerie” (printing house’s store; letter M), another “

magasin” (store; letter K), the “

imprimerie, reliure, machines” (printing, binding, machinery; letter S) and some “

ateliers des frères” (workshops of the brothers; letter Q) (

Favier 1897, pp. 318–19) (

Figure 9). It is unclear whether cloisonné was produced in the “workshops of the brothers” or if products were still subcontracted from Decheng in collaboration with its owner, Jia Derun. Anyway, the resulting cloisonné objects were stored and sold in the “Chinese store”, the “store” and the “printing house’s store” Inside the Beitang complex. Gradually, especially after the Boxers attacked Beitang in the summer of 1900, the death of Jia Derun, and the temporary closure of Decheng workshop under those circumstances, the Beitang workshop gained autonomy as a distinct Church-owned workshop in Beijing. This cloisonné workshop at the new Beitang likely emulated the glass workshop that the Jesuit missionary Kiliam Strumpf had established in the old Beitang (First North Church) in 1690′s (

Curtis 2001).

It is possible that the recovery of the Christian community in Beijing after the disasters caused by the Boxers was considered an opportunity to revitalize, or in this case, create this ‘official’ workshop of the vicariate of Beijing. There were three compelling reasons: first, the establishment of Church workshops provided employment for orphans and other needy individuals, who, in this way, learned a trade, escaped poverty, and converted to Christianity. Secondly, the workshops would allow the production of new furnishings at a low cost to re-equip churches that had been looted, damaged, or destroyed. Finally, the workshops sold to the public, which constituted a very important source of income for mission activities, funds that could, in turn, be used for reconstruction efforts after the Boxer Rebellion.

With the establishment of the Republic of China in 1912, it seemed that a new golden age of Christianity was beginning in China, as the authorities assured that all local and foreign Christians would be respected. On 17 April 1913, Adolphe Delvaux, MEP (1877–1960), a missionary from Missions Étrangères de Paris who was invited by Jarlin—Favier’s successor as Vicar Apostolic of Beijing—to stay in Beitang for a few days, recounts:

“After breakfast, a domestique led us to see his cloisonnés. He showed us a multitude of copper objects, where enamel of different colors had been cast […] There is a bit of everything: chalices, ciboria, cruets, tea sets, flower bases, candle holders, napkin rings, letter openers, trays, and boxes; we bought some trinkets.”

A member of the Beitang staff showed Delvaux the cloisonné produced by this institution. The words used by Delvaux such as “his cloisonnés”, “multitude” (

foule), “a bit of everything” (

un peu de tout) and “trinkets” (

bibelots) may not sound very flattering, but they confirm that Beitang workshop was producing, storing, and selling large quantities of cloisonné objects, both religious and non-religious, in 1913. However, the book on cloisonné in the

Complete Collection of Traditional Chinese Arts and Crafts states that during the Republic of China, a certain Li Minglin 李明林 established Jinfeng 晋丰, “a cloisonné workshop dedicated to serving Catholics”, which had 40 cloisonné workers and 30 metalworkers. According to the same book, Jinfeng operated for 20 years until Li Minglin’s death at the end of the Second Sino-Japanese War—that is, from 1925 to 1945—but the authors do not specify where they obtained all this information (

Tang and Li 2004, p. 233). This information was copied, without citing the source, in the master’s thesis by Li Lilin, who assumed that the Jinfeng workshop would work for Beitang (

Li 2006, p. 26). On the other hand, Zhou Chunbing read the said master’s thesis and tried to verify that information with official workshop records. Zhou Chunbing did not find the Jinfeng workshop but found the Jin Yufeng workshop 晋裕丰, which was led by Wang Zhongyun 王仲云 and located in the current Liulansu Hutong, very close to Beitang (

Zhou 2022, pp. 184–85). In summary, it is not possible to confirm the existence of the Jinfeng workshop, and the connection between the Jin Yufeng workshop and the production of Catholic objects is unclear. Perhaps all of this is confused with the Beitang workshop. On the other hand, mission workshops were not under Chinese jurisdiction and, therefore, are not registered with other businesses in official records.

To confirm the existence of the Beitang workshop, in addition to the information I am providing the testimony of Brother Ladislaus, CSD (Broeders van Amsterdam), a Dutch missionary who wrote about the 5 years he spent in China before 1932, is also relevant:

“We stayed in the Pe Thang (Beitang), which is the North Church, the residence of Mgr. Jarlin: there is a large printing press attached to it. The monastery of the Sisters of St. Vincent, with its refuge for children, the elderly and the unfortunate, and which is inhabited by 700 people, also belongs to it. Rarely have I seen such a beautiful Institute, as neat and tidy as everything was. [It is] completely Chinese but very beautiful. Here is a wonderful opportunity for the girls to do embroidery. A lot of work is done, and everything is neatly made. The cheapest type of tablecloths with 12 napkins costs $400! All kinds of church goods are also manufactured there. The Fathers have the famous cloisonné furnishings, whose products are also very expensive.”

The Beitang cloisonné workshop was located within the Beitang complex (Third North Church), next to the Lazarist printing press and the monastery and orphanage of the Sisters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul (see

Figure 9). Brother Ladislaus describes the facilities as “completely Chinese but very beautiful” and emphasizes that the products produced there were very expensive.

In the Bulletin catholique de Pékin of 1916, a review was published about the catalogue titled “Religious Goldsmithing. Cloisonnés of All Kinds-Restoration, Gilding, and Silvering of Sacred Vases”, published by the Pé-t’ang (Beitang) printing press. The catalogue contains “lithographed designs of a certain number of cloisonné models: chalices, ciboria, ostensoria, holy water fonts, ewers, cruets, trays, boxes for holy oils, crosses, candlesticks, holy water stoups, ciborium boxes, altar crosses, processional crosses, episcopal croziers, etc.” (Bulletin catholique de Pékin 1916, p. 79). The catalogue review states that “these pieces have existed for a long time, without anyone having thought of cataloguing them”, and refers to the Beitang printing press to order the catalogue and cloisonné objects. This 1916 catalogue aligns with the testimonies from 1913 and 1932 mentioned earlier, confirming that Beitang had both a store and a cloisonné production workshop. In the Bulletin Catholique de Pékin of 1917, an advertisement for the Beitang workshop titled “Religious Goldsmithing of Pei-t’ang” is included. It provides a list of objects—chalices, ciboriums, monstrances, a holy water font, an ewer, cruets with a tray, a container for holy oils, an altar cross—briefly described with their measurements and prices (Bulletin catholique de Pékin 1917, p. 210).

Another catalogue from the cloisonné workshop of Beitang was published in 1925. This catalogue was partially reproduced—based on a copy preserved in the National Library of China, including many of its photos—in a master’s thesis in 2006 that paid special attention to the prices of the objects (

Li 2006, pp. 25–43). However, due to the poor quality of the photographic reproductions, it is nearly impossible to distinguish the objects in that work. Two publications from 2020 and 2022 used some of the photos from the 2006 master’s thesis. As I mentioned, these works are not aware that Beitang had its own workshop. Also, there has been no in-depth study of Beitang workshop’s catalogue, nor has there been an attempt to identify real pieces by comparing them with the catalogue photos. I have not been able to consult the 1925 catalogue at the National Library of China. However, I have found the 1925 and 1928 catalogues in the archive of the Mother House of the Lazarists in Paris or Archives Historiques de la Congrégation de la Mission, Paris (

Figure 10).

On the cover of the 1925 catalogue, number 5 has been written, so between the first one in 1916 and this one in 1925, there must have been three more issues.

The 1925 catalogue of the Beitang workshop indicates on its inner cover, “Printing House of the Lazarists of Pei-t’ang, in Beijing. Printing. Lithography. Bookstore. Character Foundry. Binding. Devotional Objects. Religious Images. Manufacturing of all kinds of objects in cloisonné, gold, silver, copper, bronze, and enameled metal, etc., etc.” (

Figure 11).

It is logical that the workshop related to the printing house also carried out metalwork such as the casting of characters, for which furnaces would be necessary, and these furnaces would also be used for the work of other metallic and cloisonné objects. Indeed, in Favier’s plan of the Beitang complex the workshops are placed close to the kitchens (see

Figure 9, letter R). This was suitable, as the heat from the ovens could be used both for cooking, casting metal objects, and making cloisonné enamel.

The catalogue states that they offer prices lower than those in Beijing’s stores, without compromising quality, and services related to metalwork such as regilding, replating, and the repair of sacred vessels and other worship objects. It also offers the possibility of fulfilling orders “of a size and style that are not designated in this catalogue”, at an additional cost. This catalogue is dated September 1925, it has 40 pages and includes numbered objects from 100 to 324. The catalogue is divided into sections dedicated to “chalices”, “ciboria”, “monstrances”, “crosses, chandeliers, and candlesticks”, “incense burners, holy water fonts, episcopal crosses, pectoral crosses, etc.”, “suspension sanctuary lamps”, “devotional objects”, “office items”, “miscellaneous”, and “cloisonné vessels”. On the other hand, the 1928 catalogue is a “special catalogue” dated January 1928. It has 15 pages, and includes non-religious objects numbered from 501 to 641 in the sections “vessels, terrines, chandeliers, etc.”, “office items”, and “latest novelties”, which are primarily decorative vessels. Both catalogues (1925 and 1928) are written in French and Chinese, providing a brief description of each object, its materials, measurements, and price, as well as photographs of a significant selection of the offered objects. As we can see, Beitang not only sold religious objects but almost any type of souvenir. Two of the photographs from the 1928 catalogue were also published in Favier’s book on Beijing in its 1928 edition (

Favier 1928, plates 55, 56). As a result, anyone who bought the cloisonné from Beitang was not only acquiring a tourist souvenir or a religious object but also a part of the ‘millenary history’ of Beijing.

The workshop probably had the artistic supervision of Favier in its early stages, although its management was overseen by the director of the Lazarists’ Beitang printing press, to whom all orders were directed according to advertisements and catalogues. This person was Auguste-Pierre-Henri Maes, CM (1854–1936), a Lazarist Lay Brother who arrived in Shanghai in 1878 and took his vows in Beijing the same year. He was in charge of the Beitang Lazarist Press from 14 March 1878, until 30 June 1932, and died in Beijing on 11 February 1936 (

Brandt 1936, p. 89).

5. Characteristics and Selection of Examples from the Beitang Workshop

The photographs in the Beitang catalogues leave no doubt about identifying the workshop and the approximate chronology of numerous objects that are now scattered in churches, religious institutions, and museums worldwide, as well as in the art market. On the following pages, I present the formal characteristics of this workshop and a selection of objects that I have found, providing relevant chronological references.

There was a mark from the Beitang workshop that has been misinterpreted until now. This mark was found on the chalice of the Park Abbey of the Premonstratensians in Heverlee, Belgium (Museum Parcum, CRKC.0080.1053) and had been mistakenly associated with Nantang (

Bisscop 2010, nr 6.77;

Parada López de Corselas and Vela-Rodrigo 2021). The chalice is displayed in the current museum of this abbey. The chalice from Heverlee was made in the Beitang workshop and corresponds—with slight differences—to model number 102 from its catalogue. Also, the chalice kept by the Missiehuis Sint Jozef in Panningen, The Netherlands, is model number 102 (

Figure 12).

The mark on the Heverlee chalice is on the screw that, from the base, connects the different pieces of the chalice. This piece is included in Beitang workshop chalices only when there is a cover that conceals the interior of the chalice base. The screw secures this cover that beautifies the interior of the chalice’s base. The Beitang workshop mark consists of a beaded hexalobe that contains the inscription 北京/天主堂/制造, Beijing/Tianzhutang/Zhizao (Beijing/the Hall of Heaven/produced; Beijing’s Hall of Heaven Produced). Tianzhutang was the title conferred by the president of the Ming dynasty’s Ministry of Rites to the Catholic churches in 1611. Its literal translation is “Hall of the Lord of Heaven”. According to Sweeten, “the high official was aware that Jesuits had decided on using “Tianzhu” for (Christianity’s) God and his choice of “tang” seems inspired because it had a literary tone and meant an important meeting place, often used in conjunction with buildings within a government compound. Equally significant, neither Buddhists nor Daoists named temple buildings tang, thus eliminating nominal confusion” (

Sweeten 2020, pp. 44–45). The inscription on this mark from the Beitang workshop does not explicitly refer to any specific church, but the phrase “Catholic [Christian] church of Beijing” can be interpreted as the Beijing Catholic Siege or Cathedral, i.e., Beitang. This is the first accurate identification of this mark. Recently, a second mark in French from the Beitang workshop has been published. This mark, “FABRIQUE/ DE CLOISONNÉS/ PÉTANG–PÉKIN”, was found on the base of an ornamental vase adorned with dragons and S-shaped handles (

Zhou 2022, p. 184). I confirm that this vase—with slight variations in the decorative patterns—is the model number 524 in the Beitang catalogue from 1928 (

Figure 13).

Possibly, the mark “北京/天主堂/制造” was intended for some religious items designed for missionaries—who were more familiar with Mandarin than the average tourist—and native priests, while the mark “FABRIQUE/ DE CLOISONNÉS/ PÉTANG–PÉKIN” might have been intended for decorative items for tourists and export. The existence of the two types of Beitang workshop marks, the testimonies provided by missionaries who visited the workshop, as well as the catalogues published by the Beitang Printing House, are evidence confirming the existence of a cloisonné workshop that belonged to Beitang and was within the cathedral complex alongside the printing house. Even if there were a private workshop occasionally subcontracted by Beitang for cloisonné, all the Western sources I have cited exclusively mention the workshop owned by Beitang, with its manager being the director of the Beitang Printing House.

The Beitang workshop was represented in exhibitions and publications relevant to the study of Chinese Christian art. I would like to highlight some examples. In 1923, two photographs featuring various pieces from the Beitang workshop were published with the caption “Orfévrerie religieuse du Pétang 北堂法藍活” in the

Guide du tourisme aux monuments religieux de Pékin (

Planchet 1923). These photographs include the ciborium 129, chalice 112, and the monstrance 137.

Several pieces were sent to the First Vatican Missionary Exhibition in 1925, as a ciborium and a chalice (Vatican Museums, inv. 102181.2 and 102184.2) (

Beauty Unites Us 2019, nr. 5). They are the ciborium 129 and the chalice 112, which occupy the entire Plate III of the Beitang catalogue. The chalice and ciborium of the Vatican Museums were also shown in the “Chinese Christian art from the Vatican Museums” exhibition at the Asian Civilizations Museum in 2023 (

Catholic News 2023). In this exhibition the altar cross number 313 from the Beitang workshop’s catalogue was also included (

Figure 14).

The ciborium 129 and chalice 112 are the same models published in the already mentioned Beijing guide of 1923 and the most expensive models of a ciborium and a chalice in the Beitang catalogue if ordered in silver ($77 each). The catalogue displays prices in “$”. These amounts might signify trade dollars or Hong Kong dollars from the corresponding era. The chalice 112, 25 cm in height, had different prices depending on the finishes. The specimen with 6 cloisonné medallions and 6 medallions with chiseled reliefs, and the cup and paten in silver, cost $60. The same model, but gilded and without cloisonné, cost $50. The same model made entirely in silver with some cloisonné enamels cost USD 77. The ciborium 129, 32 cm in height and with a capacity for 400 hosts, was offered with cloisonné enamels and the cup in gilded silver, for $58. The same model, all in gilded silver, cost $77. These data offered in the Beitang workshop catalogue indicate that cloisonné in these pieces represented around 16% of their value and accounted for a difference of around $10, while silver marked a difference between $17 and $19, representing between 22% and 24% of its value. On the other hand, the chalice 102 with its base in cloisonné and the cup in gilded silver—as the Heverlee one—is 22.5 cm high and it cost only $37.

The special issue of

Collectanea dedicated to Chinese Christian art included a photo featuring various pieces from the cloisonné workshop of Beitang, as indicated by the caption, “atelier du Pet’ang à Pékin–Ornements d’église en cloisonné (émail chinois)” (

Collectanea Commissionis Synodalis 1932, p. 521). The photo showcases two chalices (nrs. 100 and 112 from Beitang catalogue), an altar cross (nr. 147), two candlesticks (nr. 152), and two vases for flowers with the Sacred Heart (nr. 255). Recently, some objects of Chinese Christian cloisonné from Spanish collections have been published without identifying their workshop of origin (

Parada López de Corselas 2022). Several of these pieces were made in the Beitang workshop (

Figure 15).

The cruets from the Oriental Art Museum in Avila are model 171, a pyx from a private collection in Madrid is model 175, and a situla from another private collection is model 178 from the Beitang workshop catalogue of 1925. The lid of the pyx has the same motif of the vexilliferous Agnus Dei as the paten of the chalice in Heverlee.

The Beitang workshop established a very extensive production to supply churches but was also aimed at the general public. This production rationalizes, standardizes, and synthesizes decorative elements that were already present in some of Decheng’s works from the late 19th century. Overall, all design elements are simplified, particularly the patterns of the backgrounds. The main goal is to produce in large quantities and at a low cost, leading to a dramatic decrease in quality. The star-and-circle patterns present in works like the Utrecht chalice tend to be eliminated. The predominant pattern becomes curls around axes arranged as if they were clusters, greatly simplifying the rinceau of the Saint Peter chalice’s paten. Stars are generally used as decorative elements in borders or within circles; if used as a background pattern, they are greatly simplified, drawn in the manner of asterisks without enamel filling. The color range is drastically reduced, and there is little use of gradient colors; the colors are generally opaque and not translucent as before. Figures and scenes are eliminated, opting for symbolic emblematic motifs within the symbolist trend that began in the late 19th century. Gradually, elements of Art Nouveau and Art Deco are introduced. The workshop continues to use lotus flower-shaped patterns from Chinese tradition and the honeysuckle motif (忍冬紋). The most characteristic elements of the Beitang workshop are the curl pattern and the mandala-shaped medallion. Blue or white is used as the background color, with white becoming the predominant color. Some crosses—only those without the figure of the crucified—decorate both sides; sometimes one side of the cross uses blue as the background color, and the other side uses white.

6. The So-Called Namban Cloisonné Crucifixes: A Wrongly Attributed Beitang Production

There is a kind of urban legend circulating in the art market regarding various types of cloisonné-decorated crosses or crucifixes with an Asian appearance, which are commonly labelled as Japanese, and even as Namban (

Figure 16). The origin of this erroneous idea is traced back to the crucifix, 12.7 cm high, kept at the Osaka Municipal Museum. Some scholars proposed in 1982 that it was made in the Momoyama period (1568–1600) or, in any case, before the anti-Christian edict of 1618 was promulgated (

Garner 1962, p. 100;

Coben and Ferster 1982, pp. 21, 175). This cross was not made in Japan or during the indicated period. Another very similar cross, albeit larger (26.5 cm), is preserved in the Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Japanese Art. In the catalogue of this collection, it was stated that “other examples of this model are known. A similar smaller crucifix in the Osaka Municipal Museum is tentatively, and certainly erroneously, dated by some authorities to the Momoyama period (1568–1600). From a technical point of view, this is surely impossible, and it must be concluded that this is of a later date, almost certainly from the third quarter of the nineteenth century” (

Impey and Fairley 1994, nr. 78). Although this observation is more cautious, it is also incorrect because both the Osaka cross and the one from the Khalili Collection were made in China in the early 20th century, specifically in the Beitang workshop. The same can be said about the pectoral cross kept at the Oriental Museum in Valladolid, which is not Japanese, but Chinese (

Parada López de Corselas 2022, Figure 8). All these crosses are very similar to pieces 237 (13 cm), 238 (20 cm), and 239 (26 cm) from the Beitang catalogue published in 1925. It should be noted that the measurements in the Beitang catalogues are purely indicative, as stressed by these catalogues, and the workshop produced more designs than those illustrated in the catalogues. On the other hand, the rectangular-based altar cross at the Uldry Collection, 22.7 cm high, was correctly associated with China but was dated to the 19th century (

Brinker 1989, nr. 375). This cross is the piece number 149 in the 1925 catalogue of Beitang. I have located another similar specimen in the art market

6. All these crosses are like the altar cross in the Vatican Museums (Inv. 102212), donated during the First Vatican Missionary Exhibition of 1925 (

Beauty Unites Us 2019, nr. 4;

Fiussello 2023, p. 141). It is model number 145 from the Beitang workshop.

Another altar cross from a private Spanish collection is a variant of this model and serves to summarize some of the characteristics of the Beitang workshop (

Figure 17): flat and opaque colors, predominance of white background, unifying pattern of simple curls and/or asterisks with some red flowers, decoration based on emblems or symbolic motifs—such as the

arma Christi or instruments of the Passion—absence of scenes, representation of the Agnus Dei like that of the paten of the chalice from Heverlee or the pyx from Madrid.

The Museum het Princessehof in Leeuwarden exhibited in 1992 a crucifix and some cruets that were attributed to the Edo period (1600–1868) (

Borstlap 1992, p. 31, Figure 36), pieces that were sold in 2006 by a well-known auction house maintaining said attribution

7. However, the crucifix is model 238 from the Beitang catalogue, and the cruets are model 181. When in doubt about whether a Christian cloisonné piece is Chinese or Japanese, art dealers often classify it as Japanese to increase its price.

7. The Tushanwan Workshop in Shanghai

The artistic workshops of Tushanwan have their origins in the school of painters and sculptors founded by Juan de Dios Ferrer (Fan Yanzuo 範延佐, 1817–1856) in Shanghai in 1852. After the Taiping Rebellion and the destruction of the initial Catholic orphanages in Shanghai in 1860, the construction of the Tushanwan Orphanage began in 1864 in Zikawei, adjacent to the residence of the Jesuits, and its chapel was completed in 1867. The artists of Tushanwan created not only Christian art for both churches and private devotions (

Motoh 2020), but also decorative objects, and souvenirs (

Ma 2016). They produced works in both xihua, or Western-style painting, and gouhua, the traditional, academic, classical, or national style of Chinese painting (

Clarke 2013, pp. 152–54). In 1880, a tin workshop was established to repair various copper and iron items for churches and hospitals in the area. In 1901, a foundry workshop was built, followed by an iron foundry in 1907, which later transformed into a hardware factory in 1908 (

Zhou 2022, p. 150). This hardware workshop would be responsible for creating metal works and occasionally decorating them with cloisonné. Tushanwan regularly participated in exhibitions, but there are no records of awards related to its cloisonné until 1915 (

Zhou 2022, p. 37). Like the Beitang workshop, the Tushanwan workshops also published several catalogues. The earliest one known is dated 1928. It is entitled

Orphelinat de T’ou-sè-wè–Zi-ka-wei. Atelier d’Orfèvrerie. Objects de culte and a copy of it if preserved at the Shanghai Library.

In the said 1928 Tushanwan catalogue, it is detailed that the orphanage accommodated 254 children or young males at that time. These children, whether orphans under institutional care or pupils sent by their parents, entered the workshops between the ages of 8 and 10 to acquire vocational skills. Upon completing their training, they had the option to either establish their own businesses or continue working in the Tushanwan workshops. Importantly, there was no obligation for conversion to Christianity. The catalogue provides insights into various workshops and showcases a notable masterpiece—a painting depicting the Chinese imperial family, dispatched to the French legation in Beijing in 1910. Despite being overseen by Jesuits, the Tushanwan workshops occasionally collaborated with the Lazarists and accepted commissions from them. One particularly noteworthy Lazarist commission was the painting of the Virgin of Donglu in 1908, ultimately becoming the official image of Our Lady of China. This artwork was commissioned by Lazarist René-Joseph Flament, CM (1862–1954), inspired by Bishop Jarlin, the Vicar Apostolic of Beijing, and Monsignor Fabrègues, who was director of the district of Baoding. When Flament initiated the commission, he included a photograph of Katherine Carl’s portrait of Empress Cixi to serve as a model for the Virgin’s painting (

Clarke 2013, pp. 89–90).

The metalworking and goldsmithing workshop at Tushanwan produced many different types of liturgical objects (

Gao 2009, pp. 77–79;

Song 2012, pp. 284–89) (

Figure 18). This workshop was fundamental for the renewal of cloisonné in China and was able to compete with Beijing from Shanghai (

Zhou 2022, p. 152). The cloisonné workshop at Tushanwan produced both religious and non-religious or decorative works. Among the latter is a plate decorated with fish and lotus flowers, marked with an oval stamp bearing the workshop’s name in both French and Mandarin (

Zhou 2022, pp. 152–53, Figure 1-10-6, 1-10-7). Additionally, a circular box with printed letters, “ORPHELINAT/ TOU-SÈ-WÈ/ ZI-KA-WE”, is known to belong to the Tushanwan Museum (

Zhou 2022, p. 152, Figure 1-10-5).

In the 1928 Tushanwan catalogue, a large number of objects are depicted in European shapes, generally of ‘Gothic’ (Gothic Revival) or ‘Roman’ (classical) type. The catalog offers various options to order the same shaped object with different finishes, whether in unenameled metal, gilded, or enameled. The Tushanwan workshop generally incorporates more iconographic motifs or patterns from the Chinese tradition than the Beitang workshop and creates a much stronger contrast with European traditional shapes. One element that clearly distinguishes this workshop from Beitang is the cracked-ice pattern or binglei 冰裂, used, for example, in a set of cruets and their tray (

Figure 19). The missionaries went to the suburbs to collect architectural fragments or carved components. These remnants served as models for the Tushanwan Carving Workshop (

Ma 2018). This might explain why the Tushanwan objects have more Chinese patterns.

The Tushanwan workshop also frequently incorporates patterns such as frets, auspicious Chinese characters, symbols of the Immortals combined with symbols of the Four Living Creatures, bamboo branches, and branches of plum blossoms (

Figure 20 and

Figure 21).

Like the Beitang workshop, the Tushanwan workshop uses the IHS and symbolic images of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, but it also incorporates the monogram of Mary (linked M and A) that is used as a decorative pattern in some pieces.

One of the most distinctive pieces of Tushanwan cloisonné is a specific type of pyx or host container, available in small or large sizes (

Figure 22).

It features a white or turquoise blue background with medallions depicting the Sacred Heart, the IHS, or highly schematic plant motifs. Sometimes, two medallions are joined. In the larger model, inscriptions in uppercase black letters with the recipient’s name are often included on the top of the lid. A similar inscription on the edge of the lid includes the institution giving the gift and/or a mention of the workshop, “Tou-Se-Wei Orphanage China” or “Zi-Ka-Wei Orphenage China”. The base of the host container usually bears an inscription in block letters, typically a dedication. These host containers found some popularity among members of the Maryknoll Society. Four examples are preserved at their headquarters in New York, having belonged to Rev. J.A. Walsh, P.J. Ryan, Rev. John Harnett, and Rev. J.J. Hennessy. Another specimen from the art market is owned by the Sisters of Providence. Beneath the base, it includes the inscription: “In your mass, Father/will you please give us/a memento?/Yours in Christ/Robert J. Cairns/Maryknoll/Yeung Kong/Fa Chow China/29 June 1924./Made at Sigawei Orphanage/Shanghai, China”

8. Another specimen from the art market is dated 1924 and is inscribed on the top of the lid “St. Joseph’s Church Berkeley” and on the edge of the lid “Greetings from Maryknoll” (

Figure 23)

9.

Likewise, Tushanwan frequently created objects decorated with cloisonné, leaving areas without enamel to create a contrast between the height of these spaces and the enameled areas, giving the impression of champlevé enamel. Within this category, a distinctive type of episcopal crosier from Tushanwan can be found. In this type of crosier, the dominant colors are canary yellow and melon green. One such crosier from the 1925 missionary exhibition is preserved in the Vatican Museums (Inv. 102220) and bears the inscription “Orphelinat Tou-Sè-Wè” engraved in golden letters protruding from the top of the staff (

Beauty Unites Us 2019, nr 8). Its volute is surrounded by intertwined melon plants with leaves and fruits in cloisonné in relief, simulating champlevé. In the center of the volute, there is a cross with the sacred heart. An almond-shaped piece with the sacred heart amid clouds is placed between metal scrolls that reinforce the connection between the volute and the staff. The staff features gilded relief decoration of bamboo branches, Eucharistic motifs, and books. A pagoda roof decorates the upper third of the staff. It is somewhat naive and bizarre but very original. The Tushanwan orphanage also sent a pair of vessels for the holy oils (Inv. 102180.1 and 102180.2) to the 1925 missionary exhibition at the Vatican. Both vessels are marked with the inscription in block letters “ORPHELINAT/DE TÓU-SÈ-WÈ/ZI-KA-WEI/ CHINE”, and their decoration includes a gourd (hulu) as an auspicious symbol homophonous with fulu (fortune and wealth) (

Beauty Unites Us 2019, nr. 6;

Fiussello 2023, p. 140).

Another episcopal crozier from Tushanwan is held by the Missionarissen van Scheut in Anderlecht, Belgium, and belonged to Louis Janssens, C.I.C.M. (1876–1950), who was the bishop of Jehol from 1946 until 1948 (Museum Parcum, CRKC.0056.0827). The volute of this crozier represents a green and yellow dragon, with red eyes, moving with open jaws towards the staff (

Figure 24).

In the center of the volute there is a white cross with green circles, and in the almond-shaped reinforcing piece of the volute, Christ crucified is depicted amid dark clouds. The staff is decorated with vines with bellflower flowers made of raised cloisonné that simulates champlevé. Bishop Janssens also owned a candlestick with the inscription “ZKW” (Zikawei) in dark blue enamel (Museum Parcum, CRKC.0056.0826). This candlestick is adorned with dark green plum branches and yellow flowers on a turquoise blue background. It includes the inverted Jesuit monogram in red with three black nails, as well as a red sacred heart within a yellow sun. A similar crosier from the Tushanwan workshop is kept in the Vatican Museums (inv. 102220) (

Beauty Unites Us 2019, nr. 8).

8. Concluding Remarks

The production of cloisonné in China suffered a crisis during the Opium Wars. The defeat and economic hardships faced by China in the Opium Wars dealt a significant blow to the imperial workshops during the rule of Xianfeng (1831–1861). The emperor could no longer sustain the enormous expenditure of the imperial workshops; therefore, production was significantly reduced, and most workers were dismissed while the production was liberalized and the use of cloisonné for common people authorized. Finally, cloisonné left the imperial workshops, more to meet Western demand than to decorate Chinese homes. Officials recently dismissed by Xianfeng, or those who fled official workshops in search for better opportunities, were able to open their own workshops and begin to improve the technique once again. Entrepreneur Jia Derun was able to establish his own workshop, i.e., Decheng, which reached high levels of quality and primarily worked for Westerners.

The interactions between the Lazarist missionary Alphonse Favier and Jia Derun from 1867 produced mutual benefits that contributed to the modernization of Chinese cloisonné and provided Catholics with emblematic objects symbolizing the success of the mission in Beijing. Jia Derun considered Favier as a “spiritual father” and converted to Christianity. In turn, Favier contributed technical improvements from Europe to the Decheng workshop. Among them, the introduction of galvanic gold plating or electroplating in China before 1878. The precision of cloisonné designs and colors, including shaded hues, also improved. Favier wanted to emulate great French artists such as Viollet le Duc and Poussielgue-Rusand, who had renewed the treasure of Notre Dame de Paris (

Durand 2023). The Lazarist mission aimed for Beitang to be the main Christian center in China.

During the period between 1870 and 1900, high-quality Christian works were produced in Beijing, often commemorative objects for significant anniversaries in the lives of missionaries or gifts for the Pope and other religious authorities and sanctuaries in Europe. Christian liturgical objects were inspired by Historicism, combining Western elements with Chinese artistic tradition. In early works like Delaplace’s chalice (1877), Chinese floral decoration predominates, including some Christian motifs like the cross. By 1880, Christian figures and scenes were introduced in works such as the chalices in Saint Peter’s Basilica Museum in the Vatican, the Catharijneconvent Museum in Utrecht, and Notre Dame in Paris. The predominant background color was blue, the most traditionally used in Chinese cloisonné, although pink also gained importance in the late 19th century.

The Boxer Rebellion posed a crisis in the production of Chinese Christian cloisonné. Some private workshops, like Decheng, were attacked in 1900, and Jia Derun himself died in these circumstances. After this crisis, in the early 20th century, the Church considered opening its own workshops. Mission workshops like Beitang and Tushanwan aimed to become major suppliers for Chinese Christian communities and the rest of the world. Production increased, and quality notably decreased. The Beitang workshop opened around 1900 and simplified the shapes of objects and decorative motifs that the Decheng workshop had used in the late 19th century. Beitang’s works engaged with Chinese artistic traditions and European historicist styles, mainly the Gothic Revival and Classical Style. Gradually, elements inspired by Symbolism and Art Nouveau were introduced. Scenes were eliminated in favor of emblematic motifs like the Sacred Heart and Instruments of the Passion. The predominant background color was white, associated with Christian purity.

The Jesuits opened the hardware department in the workshops of the Tushanwan orphanage in Shanghai in 1908. This department produced a wide variety of metallic objects for both Christian liturgical use and simple decoration. The same object could be ordered with cloisonné enamel or without, as well as in different metals. This workshop produced objects in ‘Gothic’ and ‘Roman’ styles but also employed some shapes and decorations taken from the Chinese artistic tradition more frequently than the Beitang workshop. In this specific aspect, the Tushanwan workshop continued the Jesuit tradition of cultural accommodation more clearly. Despite this, the cloisonné produced by the Lazarists was also perceived as a form of cultural accommodation. Le Soleil newspaper reported in 1895 about how Favier and his colleagues applied cultural accommodation in Beijing:

“The French in the [Beijing] legation remained dressed in the European style and took part in the lively, sporting life that the English had made honourable in the Chinese customs. There are balls, garden parties, comedies and even horse races. We have wine from France and mineral waters. The French of the mission, on the contrary, wear the costume of the country with the queue of postiche hair. Father Favier is even a blue button mandarin. They eat modestly raw foods. The unhealthy water of Peking would test them very much if they had not adopted the local custom of drinking it only boiling, in the form of tea. They speak the very painfully learned language of the people. They used the Chinese art of cloisonné (l’art chinois du cloisonné) for worship objects.”

It is challenging to find a Jesuit text as eloquent as this testimony on the cultural accommodation practiced by the Lazarists in Beijing. Additionally, this report sheds light on the significance attributed to cloisonné liturgical objects in the contemporary missionary context. The Lazarists intended cloisonné as a symbol of adaptation to local customs, in contrast to the French diplomatic corps, which followed and contributed to imposing European trends in China. However, it is crucial to note that this writing was an official narrative addressed to a European audience. The Lazarists likely wanted to demonstrate that they were as accommodated to China as their current competitors and the French Jesuits who preceded them. The reason for this might also be that by the late 19th century, the French Protectorate faced significant criticism, with numerous missionaries contending that it prioritized France’s specific interests over the Church’s “universal mission”. This circumstance prompted the Lazarists to underscore their narrative of cultural accommodation, employing different methods, including Chinese cloisonné.

In the 1920s, Chinese Christian cloisonné reached a peak in its production. This is a period in which workshops enhanced their commercial strategies, mainly through the publication of commercial catalogues. Numerous sources reflect the interest of missionaries in cloisonné. The missionaries themselves became opinion makers through their letters, books, articles, and reviews. The competition between the Beitang and Tushanwan workshops, the establishment of Furen University—which would open its own art department—and the celebration of the first Vatican Missionary Exhibition in 1925 could have been stimuli for Beitang to publish its first cloisonné catalogue which included photographs. Several religious institutions active in China sent cloisonné objects from Beitang to the first Vatican Missionary Exhibition. For instance, the Franciscan Missionaries of Mary (FMM) of Shanghai sent an altar cross (inv. 102212.0.0) (

Beauty Unites Us 2019, cat. nr. 4). This piece corresponds to number 145 in the Beitang catalogue. It is noteworthy that these nuns preferred the cloisonné from Beitang in Beijing over that which they had much closer in Tushanwan, on the outskirts of Shanghai. Perhaps they considered the works from Beijing to be of superior quality? The Tushanwan orphanage sent pieces from its own workshop, such as a pair of vessels for holy oils (Vatican Museums, inv. 102180.1 and 102180.2) and a crosier (inv. 102220). The Tushanwan workshop published its commercial cloisonné catalogue in 1928 and used it as a powerful means to expand its sales and compete with the Beitang workshop. Tushanwan’s pieces probably had more success in Asia and the United States—mainly Maryknoll—while Beitang’s pieces are mainly preserved in religious institutions in France, Belgium, and The Netherlands.

In conclusion, this article provides an overview of the main milestones of Chinese Christian cloisonné between the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This work is conceived as a synthetic paper to provide essential and novel information to the academic community. The presented data are preliminary results of a research that will address historical, artistic, and religious contexts in more detail and provide a greater number of cloisonné specimens, photographs, documentary sources and historiographical reflections.