To Touch or Not to Touch? An Ethical Reflection and Case Study on Physical Touching in the Pastoral Accompaniment of Vulnerable Persons, Especially Minors and Persons with Intellectual Disabilities

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Ethical Question

Anna is 17 years old and has a moderate intellectual disability. She resides in a Christian community for minors with intellectual disabilities. One evening, chaplain Peter comes to visit the community and stays to have dinner with them, as he regularly does. When he is about to leave, Anna comes to him almost in tears and tells him that her boyfriend has broken off the relationship. She is devastated. Peter listens to her story. Emotions run high, and Anna starts crying heavily. Peter tries to comfort her and hold back the tears but to no avail. Then he holds her tightly in a comforting embrace. Anna calms down. Just before leaving, Peter says he is glad he was there for her and comforted her.

1.2. Some Clarifications

2. Method for Ethical Evaluation

2.1. Sources of Morality

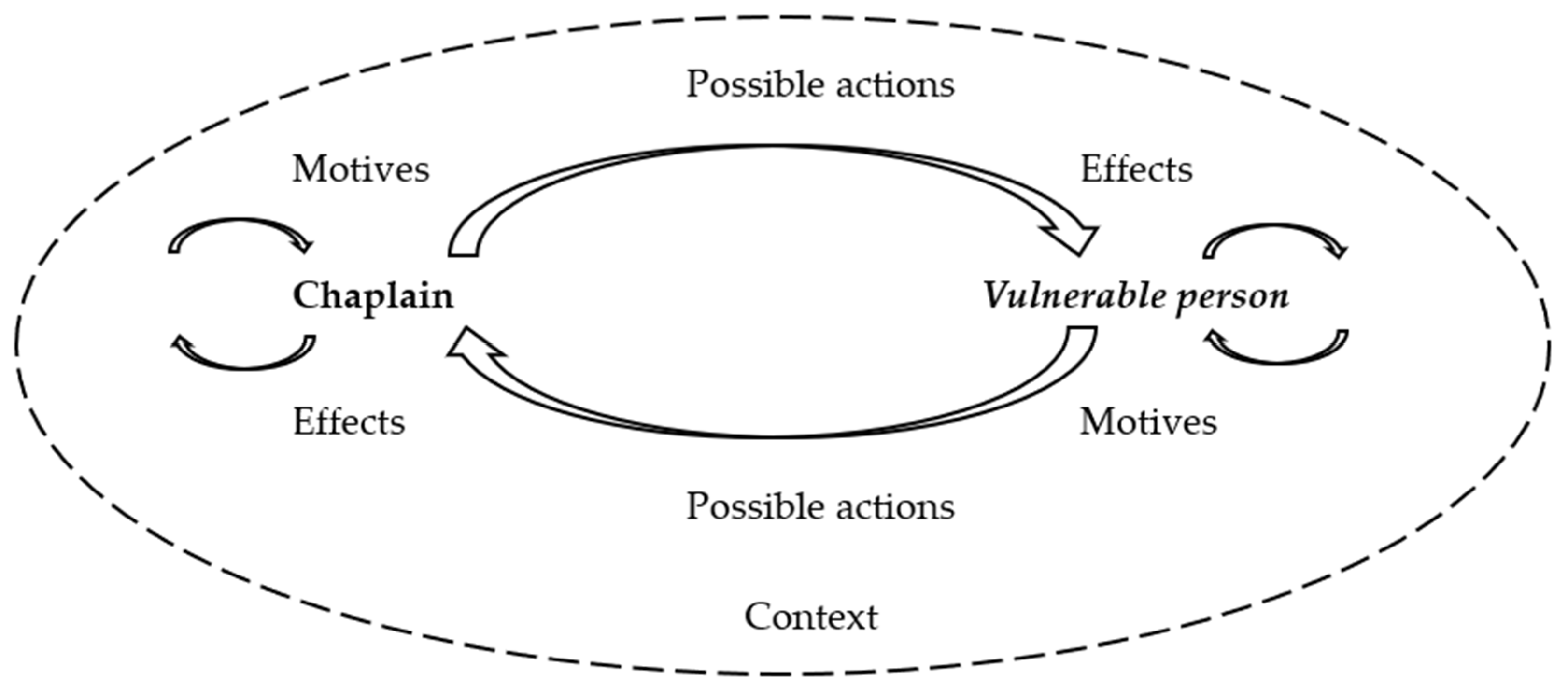

2.2. Elements of Ethical Evaluation

2.3. Dynamic Process

3. Context of the Pastoral Relationship

3.1. Asymmetry in the Pastoral Relationship

3.2. Dealing with the Power Relationship

3.3. Fostering the Sense of Responsibility

4. Motives of the Chaplain

4.1. Complexity of the Motives

4.2. Clarifying the Motives

4.3. Strengthening Integrity

5. The Physical Touch

5.1. Ambiguity of Touch

5.2. Seeking the Appropriateness of Touch

5.3. Considering Age and Development

5.4. Nurturing Professional Ethics

6. Effects on the Vulnerable Person

6.1. The Multiplicity of Effects

A few days later, chaplain Peter heard that Anna was upset when he left the community. She was confused about what his embrace could mean for her. Moreover, Peter told her that he was glad he was there for her and had comforted her. She did not know how to understand his words.

6.2. Giving Priority to the Vulnerable Person

6.3. Not Causing Harm

6.4. Obtaining Informed Consent

7. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- AAIDD (American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities). 2021. Defining Criteria for Intellectual Disability. Available online: https://www.aaidd.org/intellectual-disability/definition (accessed on 6 November 2023).

- Aquinas, Thomas. n.d. Summa Theologica. Available online: https://www.ccel.org/ccel/a/aquinas/summa/cache/summa.pdf (accessed on 6 November 2023).

- Beauchamp, Paul, and James Childress. 2019. Principles of Biomedical Ethics, 8th ed. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bush, Joseph. 2006. Gentle Shepherding. Pastoral Ethics and Leadership. St. Louis: Chalice Press. [Google Scholar]

- Doehring, Carrie. 1995. Taking Care. Monitoring Power Dynamics and Relational Boundaries in Pastoral Care & Counseling. Nashville: Abingdon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Frans, Erika. 2018. Sensoa Flagg System. Antwerpen: Sensoa and Garant Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, Larry. 2005. Touching/Physical support. In Dictionary of Pastoral and Counseling, 2nd ed. Edited by Rodney Hunter, Newton Malony, Liston Mills and John Patton. Nashville: Abingdon Press, p. 1279. [Google Scholar]

- Gula, Richard. 1989. Reason Informed by Faith. Foundations of Catholic Morality. New York and Mahwah: Paulist Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gula, Richard. 1996. Ethics in Pastoral Ministry. New York and Mahwah: Paulist Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gula, Richard. 2010. Professional Ethics for Pastoral Ministers. New York and Mahwah: Paulist Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hartung, Bruce. 2005. Transference. In Dictionary of Pastoral and Counseling, 2nd ed. Edited by Rodney Hunter, Newton Malony, Liston Mills and John Patton. Nashville: Abingdon Press, pp. 1285–86. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, Rodney, Newton Malony, Liston Mills, and John Patton. 2005. Dictionary of Pastoral and Counseling, 2nd ed. Nashville: Abingdon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Janssens, Louis. 1972. Ontic Evil and Moral Evil. Louvain Studies 4: 116–33. [Google Scholar]

- John Paul, Pope, II. 1997. Catechism of the Catholic Church, 2nd ed. Vatican City: Vatican Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Lebacqz, Karen. 1985. Professional Ethics: Power and Paradox. Nashville: Abingdon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lebacqz, Karen, and Joseph Diskrill. 2000. Ethics and Spiritual Care. A Guide for Pastors. Chaplains, and Spiritual Directors. Nashville: Abingdon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Liégeois, Axel. 2013. Asymmetry and Power in Pastoral Counselling. The Need for Ethical Attitudes. In “After You!” Dialogical Ethics and the Pastoral Counselling Process. Edited by Axel Liégeois, Roger Burggraeve, Marina Riemslagh and Jos Corveleyn. Leuven, Paris and Walpole: Peeters, pp. 201–15. [Google Scholar]

- Liégeois, Axel. 2016. Physical touch in pastoral counselling. A practical theological approach. In Noli Me Tangere in Interdisciplinary Perspective. Textual, Iconographic and Contemporary Interpretations. Edited by Reimund Bieringer, Barbara Baert and Karlijn Demasure. Leuven, Paris and Bristol: Peeters Publishers, pp. 431–47. [Google Scholar]

- Liégeois, Axel. 2021. Ethics of Care. Values, Virtues and Dialogue. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars. [Google Scholar]

- Musschenga, Albert. 2002. Integrity. Personal, Moral, and Professional. In Personal and Moral Identity. Edited by Albert Musschenga, Wouter van Haaften, Ben Spiecker and Marc Slors. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 169–201. [Google Scholar]

- Oxford University Press. 2023. Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. Available online: https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/ (accessed on 6 November 2023).

- Peeters, Evelien. 2020. Codes of Ethics as Support for Quality Spiritual Care Relationships in Healthcare Settings. Fundamental Reflections and Practical Guidelines. Ph.D. dissertation, Catholic University of Leuven, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium. [Google Scholar]

- Pope Francis. 2019. Guidelines for the Protection of Children and Vulnerable Persons. Vatican City: Vicarate of Vatican City. Available online: https://www.vatican.va/resources/resources_protezioneminori-lineeguida_20190326_en.html (accessed on 13 November 2023).

- Sanders, Randolph, ed. 2013. Christian Counseling Ethics. A Handbook for Psychologists, Therapists and Pastors, 2nd ed. Downers Grove: IVP Academic/InterVarsity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Selling, Joseph. 2016. Reframing Catholic Theological Ethics. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shackelford, John, and Randolph Sanders. 2013. Shackhelford and Sanders. In Christian Counseling Ethics. A Handbook for Psychologists, Therapists and Pastors, 2nd ed. Edited by Randolph Sanders. Downers Grove: IVP Academic/InterVarsity Press, pp. 111–38. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Kermit. 2005. Chaplain/Chaplaincy. In Dictionary of Pastoral and Counseling, 2nd ed. Edited by Rodney Hunter, Newton Malony, Liston Mills and John Patton. Nashville: Abingdon Press, p. 136. [Google Scholar]

- UKBHC (United Kingdom Board of Healthcare Chaplaincy). 2014. Code of Conduct for Healthcare Chaplains. Cambridge: UKBHC. Available online: https://www.ukbhc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Encl-4-ukbhc_code_of_conduct_2010_revised_2014_0.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2023).

- Van Heijst, Annelies. 2011. Professional Loving Care. An Ethical View of the Health Care Sector. Leuven: Peeters Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- VGVZ (Vereniging van Geestelijk Verzorgers in Zorginstellingen [Netherlands Association of Spiritual Counsellors in Care Institutions]). 2015. Professional Standard Spiritual Caregiver. Available online: https://vgvz.nl/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/VGVZ_Professional_Standard_2015_Main_Text_EN_v03_WITH_APPENDICES.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liégeois, A. To Touch or Not to Touch? An Ethical Reflection and Case Study on Physical Touching in the Pastoral Accompaniment of Vulnerable Persons, Especially Minors and Persons with Intellectual Disabilities. Religions 2024, 15, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15010005

Liégeois A. To Touch or Not to Touch? An Ethical Reflection and Case Study on Physical Touching in the Pastoral Accompaniment of Vulnerable Persons, Especially Minors and Persons with Intellectual Disabilities. Religions. 2024; 15(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiégeois, Axel. 2024. "To Touch or Not to Touch? An Ethical Reflection and Case Study on Physical Touching in the Pastoral Accompaniment of Vulnerable Persons, Especially Minors and Persons with Intellectual Disabilities" Religions 15, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15010005

APA StyleLiégeois, A. (2024). To Touch or Not to Touch? An Ethical Reflection and Case Study on Physical Touching in the Pastoral Accompaniment of Vulnerable Persons, Especially Minors and Persons with Intellectual Disabilities. Religions, 15(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15010005