Abstract

Boehmer’s Die Entwicklung der Glyptik während der Akkad-Zeit (1965), although nearly 60 years old, is still the major work on the cylinder seals of the Akkadian Period (2334–2150 BCE). It examines different themes and motifs depicted on the cylinder seals during this period. One of the figures which Boehmer discusses is the ‘kriegerischer Gott’, or martial god. Boehmer records this ‘kriegerischer Gott’ as being depicted on only eight cylinder seals. Despite this limited number of examples, the figure exhibits a unique iconography, which suggests a unique, specific personage. Furthermore, he is depicted on the seal of the scribe Adda (BM 89115), one of the most well-known seals from Mesopotamia, in which he is depicted alongside Utu/Šamaš, Inana/Ištar, Enki/Ea and Isiumud/Usmu. Because the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ is depicted together with these great deities of the Akkadian pantheon, each with their own unique iconography, it suggests that he may likewise be a figure of some importance. Boehmer devotes only one page to his discussion on the ‘kriegerischer Gott’. A more detailed investigation into Boehmer’s ‘kriegerischer Gott’ is, therefore, required. This contribution will, therefore, re-examine this figure by analysing his iconography, the unique attributes which he has, the scenes in which he is depicted, and the figures with which he is associated. The possible identity of the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ will also be addressed.

1. Introduction

During the middle of the third millennium BCE, the Akkadian Dynasty came to power in Mesopotamia, replacing the earlier Sumerian Early Dynastic city-state socio-political system with a more centralized form of government.1 This dynasty was founded by Sargon the Great, and has been called the world’s first empire,2 as peoples of different languages, religions and cultures were united under the Akkadian rulers. Under Sargon’s rule, the Akkadian Empire stretched from the Mediterranean Sea to the Persian Gulf. Although the Akkadian Period lasted for only around 200 years (circa 2334–2150 BCE), it was one of incredible importance in Mesopotamian history. There were five major rulers, Sargon, Rimuš, Maništušu, Naram-Sîn, and Šar-kali-šarri, who were followed by a period of decline.

Hansen (2003, p. 189) describes the Akkadian Period as an “era of profound artistic creativity, reaching one of the peaks of artistic achievement in the history of Mesopotamian art—and even in the history of world art.” Still, the capital city of the Akkadian Empire, Agade, has never been located, and few major works have survived, other than those which were taken to Susa as spoils by Šutruk-Nahhunte around the middle of the 12th century BCE.3 In comparison, there are many extant cylinder seals. As such, as Collon (1982, p. 21) notes, these cylinder seals “are particularly important in the study of the art of the Akkadian period in that they are almost the only source of information that we have.” The glyptic art of the Akkadian Period seals displays new and more varied iconographies than in previous or later periods—there are a greater number of themes, motifs, and individually distinguishable figures, and many of these appear for the first and only time during this period.

In 1965 Rainer Michael Boehmer published Die Entwicklung der Glyptik während der Akkad-Zeit, in which he discussed all known Akkadian Period cylinder seals. Although this book is now nearly 60 years old, it is still the major work on the subject. Boehmer discusses 1694 cylinder seals, and photographs and drawings of 726 of these are included in the plates. The analysis is divided into 29 different themes and motifs which are present on Akkadian Period cylinder seals. These include subjects like the contest scene and presentation scene, as well as various deities. Indeed, the proliferation of depictions of deities on cylinder seals is a key characteristic of Akkadian Period glyptic art, and is a striking difference to the preceding Early Dynastic Period where few deities were depicted and the most commonly depicted scenes were the contest scene and the banquet scene (Rakic 2003, p. 72).4 In general, deities are marked by horned headdresses,5 but individual gods and goddesses can be identified by certain identifying attributes, such as specific, often unique, features or their inclusion in particular scenes. It is possible to identify some of these deities as specific, named individuals, but others can only be identified as a type of deity.

One of these deities is the ‘kriegerischer Gott’, or martial or warlike god. Boehmer records only eight cylinder seals which depict this god. Two of these seals are dated to the Akkadian I Period (the reign of Sargon), one to Akkadian II (the reigns of Rimuš and Maništušu), and five are from the Akkadian III Period (from the reign of Naram-Sîn until the end of the Akkadian Period). With only eight cylinder seals, the corpus is very limited, and Boehmer only devotes one page to his discussion of this god.6 However, the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ exhibits a distinct iconography with specific identifying attributes, which makes an identification with a specific, named god, rather than just a type of deity, likely. Yet there has been minimal discussion on the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ since Boehmer’s publication nearly 60 years ago.7 The ‘kriegerischer Gott’ of the Akkadian Period, therefore, deserves a re-examination. The eight exemplars as identified by Boehmer will first be presented, and thereafter, the iconography of the ‘kriegerischer Gott’—his particular identifying attributes and the scenes in which he is depicted—will be discussed. The possible identity of the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ will then be considered.

2. The Corpus

No. 1.

No. 1: drawing by author, after Pritchard (1969:62 no. 196)

Boehmer 1965 Catalogue Number: 963, Taf.XXXIII.390

Date: Akkadian I

Type: cylinder seal (grey marble)

Dimensions: height: 3.4 cm

Provenance: Unknown

Collection: New York, private collection (ANEP 196)

Webpage: None

Description: There are five figures on the seal. The ‘kriegerischer Gott’ is placed centrally, with two gods on the left, and two women on the right. The ‘kriegerischer Gott’ is depicted en face.9 He has long hair which hangs loose on one side of his face. He wears a horned headdress marking his divinity and a ‘Schlitzrock’ or slit skirt. This slit skirt has a part bundled up at his waist, exposing one leg and allowing for ease of movement. He holds a weapon in each hand: in his left hand he holds a bow, and in his right he holds either an arrow or a staff. On his back is a quiver from which hangs a tassel. The two gods to the left of face towards the ‘kriegerischer Gott and clasp their hands together. The second of these gods holds a weapon which Pritchard (1969, p. 272) describes as having the “head of a feline or a snake”. The two women who approach the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ each play a musical instrument: the one closer to the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ plays a harp, while the second plays a percussion instrument.

No. 2

No. 2: drawing by author, after Buchanan (1966, Pl.26.328)

Boehmer 1965 Catalogue Number: 869, Taf.XXVII.324

Primary Source: Buchanan (1966, p. 63, Pl. 26.328) (Ashmolean Museum cylinder seal catalogue)

Date: Akkadian I

Type: Cylinder seal (black serpentine with green flecks)

Dimensions: height: 3.8 cm; diameter: 2.4 cm

Provenance: Kiš (K 962)

Collection: Ashmolean Museum, AN1931.105

Webpage: https://collections.ashmolean.org/object/486968, accessed on 19 August 2023

Description: Five gods approach a large bird, while a sixth god stands behind it. All the gods wear the horned headdress marking their divinity, and their hair is bound up in a bun. They are also all depicted in profile. The first god in the procession is identified by Boehmer (1965, p. 70) as the ‘kriegerischer Gott’. With his right hand he shoots his bow at the large bird, and in his left hand he holds a mace. He wears a slit skirt, although without a bundle at the waist, and he raises his leg and rests it on a mountain.10 The second god in the procession has rays emerging from his shoulders, marking him as the sun god Utu/Šamaš,11 while the third has rays emerging from his lower body. The fourth god is holding a battle axe and the fifth has water issuing forth from his shoulders, identifying him as Ea/Enki. The sixth god holds what has been identified as a tasselled standard (van Dijk-Coombes 2023, p. 125).

No. 3

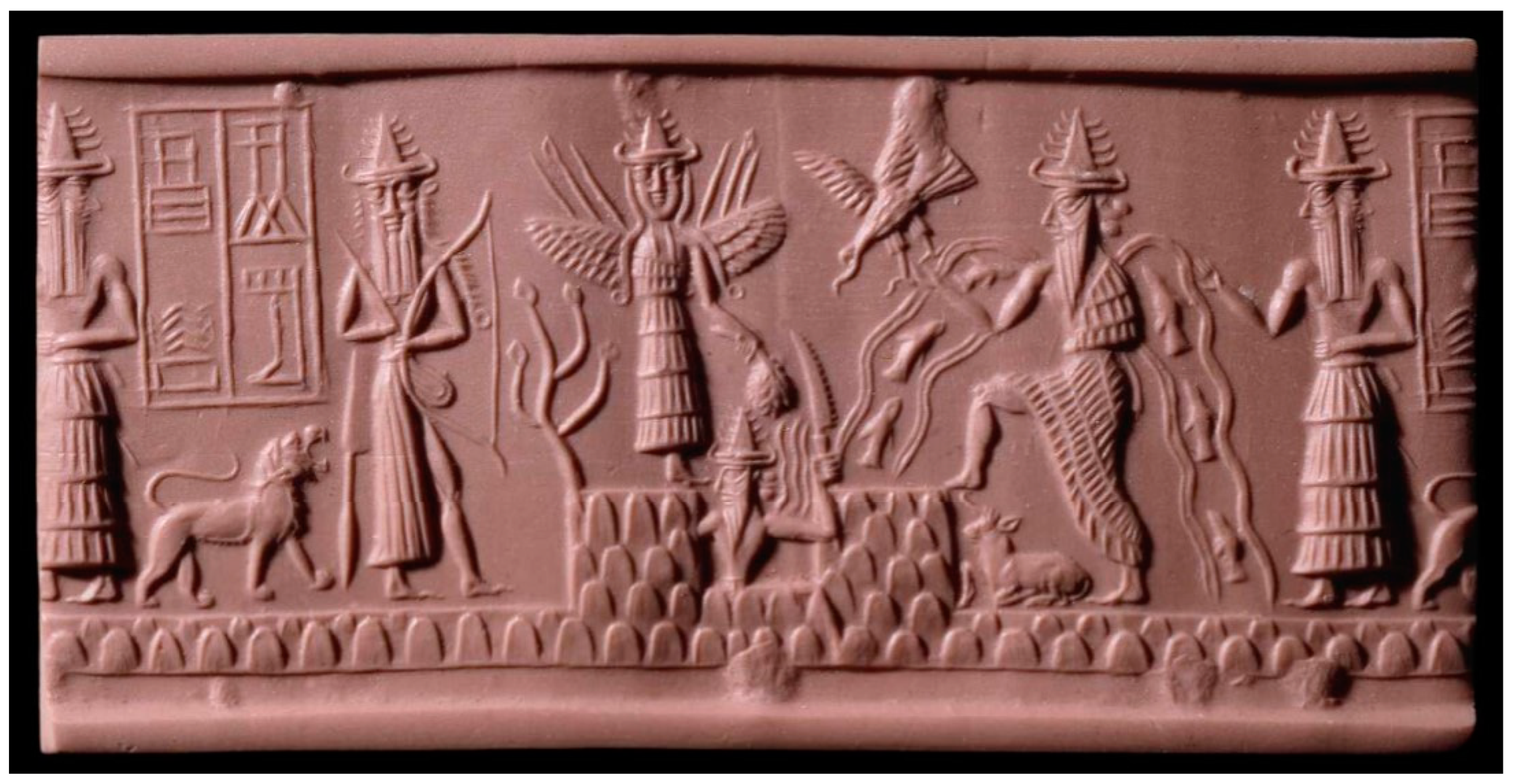

No. 3: Seal of Adda, © The Trustees of the British Museum

Boehmer 1965 Catalogue Number: 945, Taf.XXXII.377

Primary Source: Collon (1982, p. 92, Pl. XXVIII.190) (British Museum cylinder seal catalogue)

Date: Akkadian II

Type: Cylinder seal (greenstone)

Dimensions: height: 3.9 cm; diameter: 2.55 cm

Provenance: unknown

Collection: British Museum, BM 89115

Webpage: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/W_1891-0509-2553, accessed on 19 August 2023

Description: There are five deities in the scene. In the centre, the sun god Utu/Šamaš is emerging from between two mountains represented with the conventional scallop pattern. There is a plant on the left side mountain. Utu/Šamaš has rays emerging from his shoulders and he is holding his serrated blade. To the left of Utu/Šamaš is Inana/Ištar, identifiable by the weapons emerging from her shoulders, which indicate her function as the goddess of war. She is holding a cluster of dates, which indicates her role as goddess of sexuality and fertility. She is en face and has loose hair which hangs down on either side of her face. She is also depicted with wings.12 To the right of Utu/Šamaš is Enki/Ea, identifiable by the streams of water and fish which issue forth from his shoulders. He raises one leg to rest on the mountain on the right of Utu/Šamaš. There is a bull beneath his leg. A bird is in the field between Inana/Ištar and Enki/Ea. To the right, behind Enki/Ea is his vizier Isimud/Usmu, with his two faces looking in opposite directions. On the left of the scene is the ‘kriegerischer Gott’. He is depicted almost exactly as on No. 1: en face, with loose hair hanging on one side of his face, wearing a slit skirt with a bundle, holding a bow and arrow or staff, and wearing a quiver with a tassel on his back. Behind the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ and below the inscription is a lion.

No. 4

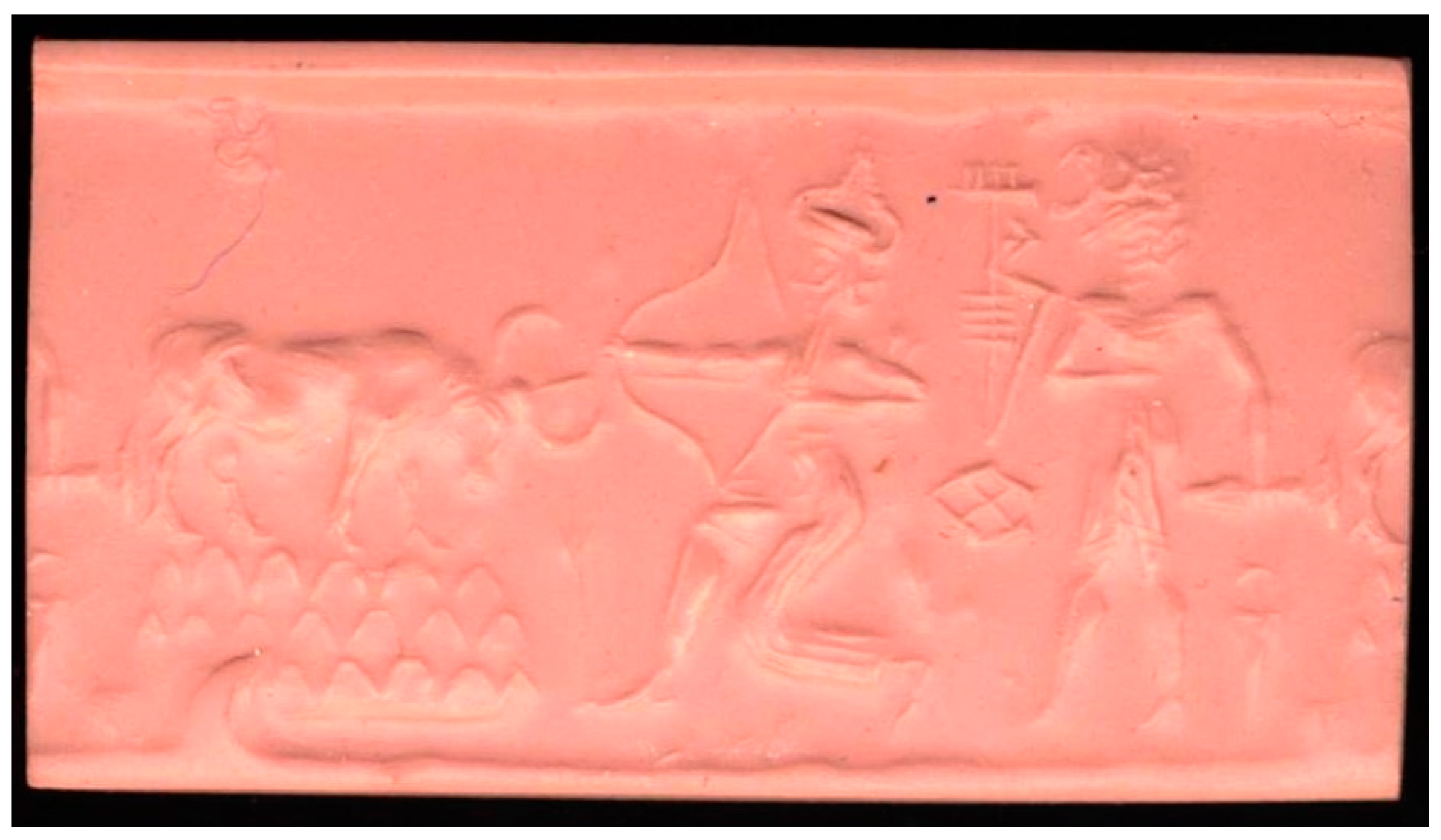

No. 4: Courtesy of the Penn Museum, object no. B 8077

Boehmer 1965 Catalogue Number: 900, Taf.XXIX.347

Primary Source: Legrain (1923, p. 146, no. 152) (Penn Museum mini-catalogue); Legrain (1925, p. 187, no. 152) (Penn Museum cylinder seal catalogue)

Date: Akkadian III

Type: Cylinder seal impression (clay)

Dimensions: height: 4 cm; diameter: 2.2 cm

Provenance: Nippur

Collection: Penn Museum, B8077

Webpage: https://www.penn.museum/collections/object/104296, accessed on 19 August 2023

Description: There are two groupings. In the first, a god holds a half crescent standard in his right hand and an axe in his left. He wears a long garment and places one foot on a mountain. This god can be identified as the moon god Nanna/Sîn (Braun-Holzinger 1993, p. 127). A second, badly damaged figure faces this god. The second grouping consists of the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ and Inana/Ištar overpowering a third god. Both the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ and Inana/Ištar are en face, while their enemy is in profile, with his body facing towards the ‘kriegerischer Gott’, but looking back at Inana/Ištar. This enemy holds a weapon in one hand, but neither the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ nor Inana/Ištar hold a weapon; instead, they hold onto the third god. Still, Inana/Ištar is in her guise as the ‘kriegerische Ištar’,13 with weapons emerging from her shoulders. The ‘kriegerischer Gott’ is wearing a slit skirt with a bundle at his waist. It is possible that he has loose hair on the right, but this could also be an imperfection in the impression.

No. 5

No. 5: © The Trustees of the British Museum

Boehmer 1965 Catalogue Number: 914, Taf.XXIX.352

Primary Source: Woolley (1934, p. 548, Pl. 214.357) (Ur Excavation Report); Collon (1982, p. 71, Pl.XIX.136) (British Museum cylinder seal catalogue)

Date: Akkadian III

Type: Cylinder seal (greenstone with copper caps)

Dimensions: height: 2.10 cm (without caps), 3.10 cm (with caps); diameter: 1.2 cm

Provenance: Ur, Royal Cemetery (U.9694; PG/695)

Collection: British Museum, BM 136776

Webpage: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/W_1928-1010-261, accessed on 19 August 2023

Description: This scene is similar to the second grouping on No. 4. The ‘kriegerischer Gott’ and the kriegerische Inana/Ištar overpower a god who is seated on a mountain while another goddess looks on. Inana/Ištar has weapons emerging from her shoulders and grasps the god’s shoulder in one hand while holding a dagger in the other. The ‘kriegerischer Gott’ holds the enemy’s beard in one hand and shoots his bow at the enemy with the other; an arrow is protruding from the enemy’s stomach. He wears a slit skirt with a bundle at his waist, and on his back, he has a quiver with a tassel. His hair is bound in a bun.

No. 6

No. 6: Seal of Lugal-šala-tuku, © The Trustees of the British Museum

Boehmer 1965 Catalogue Number: 925, Taf.XXX.359

Primary Source: Collon (1982, p. 76, Pl.XXI.146) (British Museum cylinder seal catalogue)

Date: Akkadian III

Type: Cylinder seal (greenstone)

Dimensions: height: 2.65 cm; diameter: 1.6 cm

Provenance: Unknown

Collection: British Museum, BM 89074

Webpage: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/W_1869-0122-16, accessed on 19 August 2023

Description: The ‘kriegerischer Gott’ shoots his bow at a bull, which stands on a mountain top and has an arrow protruding from between its horns. The ‘kriegerischer Gott’ is in a half kneel. He wears a slit skirt and has a quiver on his back with a tassel, which is faintly visible. Behind the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ is a lion-demon with the body of a human and the head of a lion. The lion-demon wears a short skirt and holds a dagger in one hand. In the field, there are arrows between the bull and the ‘kriegerischer Gott, and there is a dagger behind the lion-demon.

No. 7

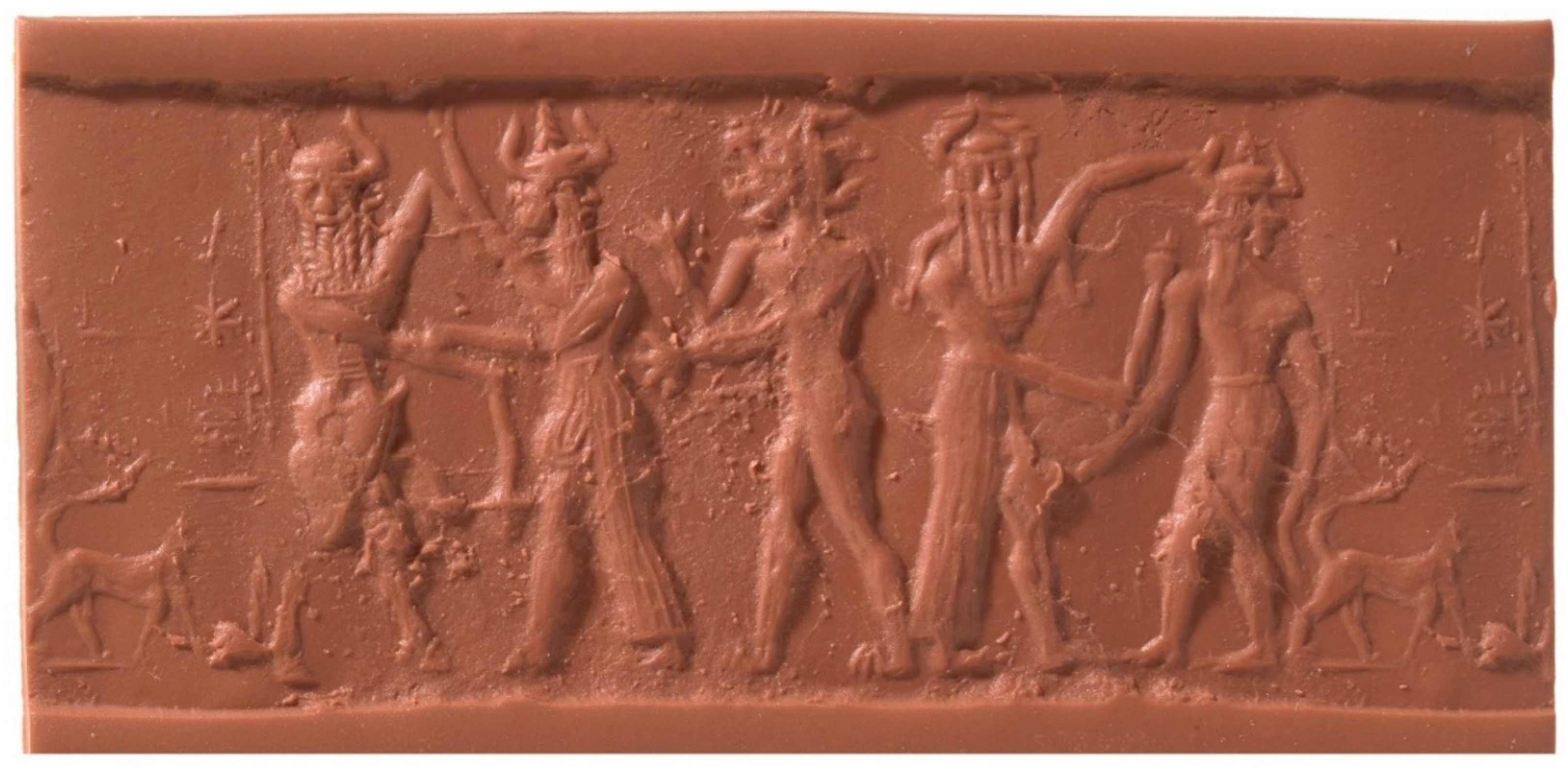

No. 7: Seal of Lušara, Vorderasiatisches Museum—Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Vorderasiatisches Museum/Olaf M. Teβmer

Boehmer 1965 Catalogue Number: 899, Taf.XXIX.346

Primary Source: Moortgat (1966, p. 103, Taf.31.277) (Vorderasiatisches Museum cylinder seal catalogue)

Date: Akkadian III

Type: Cylinder seal (serpentine)

Dimensions: height: 3.3 cm; diameter: 2.1 cm

Provenance: Unknown

Collection: Vorderasiatisches Museum, VA 3877

Webpage: http://repository.edition-topoi.org/collection/VMRS/object/24878, accessed on 19 August 2023

Description: There are two groupings. In the first grouping, a god in a slit skirt with a bundle at the waist fights against a bull-man. In the second, the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ attacks another god with a mace. The ‘kriegerischer Gott’ is en face and he has long loose hair hanging down on either side of his face. He wears a slit skirt, but there is a chip at the waist, so it is unclear whether this skirt has the bundle. Directly behind the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ is a lion-demon who appears to be attacking the god in the first grouping. The lion-demon has the body of a human, and the head, feet and paws of a lion. While the lion-demon is not wearing a skirt, it is wearing a horned headdress, marking him as divine.14 Between the two groupings and below the inscription is a lion.

No. 8

No. 8: Vorderasiatisches Museum—Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Vorderasiatisches Museum/Olaf M. Teβmer

Boehmer 1965 Catalogue Number: 964, Taf.XXXIII.391

Primary Source: Moortgat (1966, p. 102, Taf.29.218) (Vorderasiatisches Museum cylinder seal catalogue)

Date: Akkadian III

Type: Cylinder seal (shell)

Dimensions: height: 2.3 cm; diameter: 1.3 cm

Provenance: Unknown

Collection: Vorderasiatisches Museum, VA 227

Webpage: http://repository.edition-topoi.org/collection/VMRS/object/24478, accessed on 19 August 2023

Description: The seal is simply cut. There is a presentation scene in which two figures stand before an enthroned god. The flounced robe of the second standing figure may mark them as a deity. The ‘kriegerischer Gott’ stands behind this god. He is en face and wears a slit skirt with a bundle at the waist. He has a quiver with a tassel on his back. His hands are clasped together. By comparison to Nos. 1 and 3, the lines on either side of his head may either be loose hair, or weapons. The lack of other lines indicating a bow argue for it being loose hair.

3. Discussion

There are five deities on No. 3: the ‘kriegerischer Gott’, Inana/Ištar, Utu/Šamaš, Enki/Ea, and Isimud/Usmu. Because the latter four are all clearly identifiable and important deities in the Akkadian pantheon, it suggests that the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ who is depicted alongside them is likewise an important deity and is also clearly identifiable by his iconographic attributes, many of which are unique to him. His being an important deity may be supported by him being the focus of praise by the women in No. 1. A re-examination of the identifying attributes of the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ and the scenes in which he is depicted is needed in order to address the possible identity of this god.

3.1. Identifying Attributes

Iconography is not always consistent: an individual figure can be depicted in multiple ways, and multiple figures can be represented very similarly. This means that the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ could be depicted differently on different seals, but also that he may be unidentified as such on other seals. In order to analyse the ‘kriegerischer Gott’, his main attributes need to be discussed.

In three of the eight exemplars, Nos. 1, 3 and 8, the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ is represented almost identically: he is (a) depicted en face, (b) has his hands clasped before him holding weapons—a bow and either an arrow or a staff—and (c) with a quiver with a tassel on his back. Furthermore, (d) he has long hair which hangs loose either on one or both sides of his face,15 and (e) he wears a specific type of long slit skirt in which the excess is bundled at his waist, exposing one leg and allowing for ease of movement. This can be classified as the ‘stereotypical’ depiction of the ‘kriegerischer Gott’, and it occurs when the god is not actively engaged in some type of combat or contest. Each of these five attributes will be dealt with in turn.

3.1.1. En Face

The ‘kriegerischer Gott’ is depicted en face in Nos. 1, 3, 4, 7 and 8. That the god is depicted in profile in Nos. 2, 5 and 6 may be due to him being actively engaged in battle or hunting, and therefore, facing his foe.16 En face depictions are rare, partially due to the complexities of carving in this manner as opposed to in profile.17 En face or frontal depictions such as this where a deity ‘faces’ the viewer express a more intimate representation because they create the potential for direct communication between the deity and the viewer. Because such depictions are rare, they are “not merely an iconographic convention but a form of conveying meaning” (Asher-Greve and Westenholz 2013, p. 166). En face depictions are usually restricted to goddesses and ‘Zwischenwesen’, the latter being liminal beings which may function as guardians, gatekeepers and messengers (Sonik 2013, p. 286). In terms of goddesses, it is usually Inana/Ištar and goddesses who were the highest rank in their local pantheon who are depicted en face (Asher-Greve 2006, p. 35),18 and as such, the en face depiction may express their “high status and importance” (Asher-Greve and Westenholz 2013, p. 166). In comparison, it is unusual for gods to be depicted en face,19 and the repeated en face representation of the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ is, therefore, notable. Indeed, as Asher-Greve and Westenholz (2013, p. 166) note, en face depictions are “applied selectively”, and portraying the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ in this manner must have been a conscience decision.20 As such, it may express his presence in the scene, and mark him as important in some way. This, together with his depiction on No. 3 with major deities of the Akkadian pantheon,21 and his being centrally placed and the object of praise by the women on No. 1 suggests that the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ was an important deity during this period.

3.1.2. Weapons

While the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ holds his weapons before him on Nos. 1, 3 and 8, he is actively using his bow in Nos. 2, 5 and 6. On No. 7 he is instead using a mace to hit his enemy.22 Boehmer (1965, p. 70) also states that the god is holding a mace in No. 4, but he and Inana/Ištar are together overpowering the third god. Therefore, while the god holds his weapons only in Nos. 1, 3 and 8, this is because he is using them in the other exemplars.

3.1.3. Quiver

The god has a quiver with tassel on his back on Nos. 1, 3, 5, 6 and 8. On No. 2 the lack of quiver may be due to considerations of space. On Nos. 4 and 7 the lack of quiver may be due to the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ not holding or using a bow. This tassel on the quiver is also found in Akkadian Period scenes of human combat23 and was probably used for cleaning arrows (Collon 1982, p. 34; 2005, p. 162). It is, however, rare in scenes of deities,24 particularly when those deities are not involved in combat. That the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ is wearing a quiver with a tassel, particularly in Nos. 1, 3 and 8 where he is not in combat, is therefore an important and distinctive characteristic of this particular god.

3.1.4. Long Loose Hair

The god has long, loose hair in Nos. 1, 3, 6, and 7, and possibly in No. 4. Male gods usually had their hair bound up in buns, as the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ does on Nos. 2, 5 and 6. Long, loose hair is unusual, but not unique to the ‘kriegerischer Gott’.25 Still, that he is consistently depicted with long loose hair marks this as a distinctive feature of the ‘kriegerischer Gott’.

3.1.5. Slit Skirt

The ‘kriegerischer Gott’ wears a slit skirt with a part bundled up at his waist exposing one leg on Nos. 1, 3, 4, 5 and 8. The god on No. 2 wears a slit skirt, but it has no bundle. Due to the kneeling posture of the god on No. 6, it is unclear whether the slit skirt that he is wearing has a bundle. Similarly, No. 7 is chipped at the god’s upper leg, so it is uncertain whether this slit skirt had a bundle. Slit skirts are fairly common in Akkadian Period iconography, but these may or may not have the bundle at the waist.26 Collon (1982, p. 92) describes this type of slit skirt with the bundles as “either has a cod-piece or … hitched up in front.” It is more likely the latter, allowing for ease of movement. Usually, a god wearing a slit skirt raises his leg and rests it on something; it is rare that a figure wears a slit skirt while not raising his leg. That the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ consistently wears the slit skirt with a bundle, and that his leg is exposed while not lifting it, is therefore notable.

3.1.6. Discussion on the Attributes

The five attributes are unusual in Akkadian Period iconography, which indicates a deliberate choice to depict this god with these attributes. They are also rather consistently applied to the eight exemplars, and missing attributes can often be explained by taking the iconographic context into consideration.27 For this reason, the relative lack of these attributes of the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ on Nos. 2 and 6 needs to be addressed.

In No. 6, the god is in profile, his hair is bound in a bun, and it is unclear whether his slit skirt has a bundle. This god has more in common with a figure depicted in two ‘Götterkampf’ scenes—scenes of gods in combat with each other—who shoots his bow and arrow at enemies.28 In one of these,29 this god also has a quiver with tassel on his back, but he has none of the other attributes of the ‘stereotypical’ ‘kriegerischer Gott’, and he is furthermore nude. The figure on the second seal is similarly depicted, but additionally does not wear the horned headdress marking his divinity.30 He is, similar to the god on No. 6, in a half kneel. These three figures—the ‘kriegerischer Gott on No. 6 and the two figures on the ‘Götterkampf’ scenes—appear to represent the same figure. The question is whether all three should be considered as the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ under discussion, or if all three, including No. 6, should be excluded from the corpus. Because the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ on Nos. 4, 5, and 7 are all involved in ‘Götterkämpfe’, and in No. 5 he shoots his bow, No. 6 and the two seals could also legitimately depict the ‘kriegerischer Gott’. However, as a group, their iconography is very different to the ‘stereotypical’ depiction of the ‘kriegerischer Gott’, and all three should, therefore, be excluded from the corpus of the ‘kriegerischer Gott’.31

The god on No. 2 is in profile, he does not have a quiver, his hair is bound in a bun, and he is not wearing a slit skirt with a bundle. The only attribute of the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ which this god has is the bow which he is shooting at a large bird. This battle with a large bird is depicted on other Akkadian Period seals.32 Van Buren (1933, p. 26) and Frankfort (1939, p. 135) have both identified this scene as the slaying of Anzu,33 and therefore, identify the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ as Marduk or Ninurta, respectively. Both of these identifications are anachronistic,34 and identifying the ‘kriegerischer Gott based on the texts used for these identifications should be done with caution. Whatever the case, No. 2 is the only example of this type of scene of a battle with a large bird in which the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ appears. Additionally, this god exhibits only one of the attributes which can be used to identify the ‘kriegerischer Gott (i.e., the bow). While this god is clearly a martial deity involved in a battle, he is not necessarily the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ which is depicted on Nos. 1, 3, 4, 5, 7 and 8. No. 2 together with No. 6 should, therefore, be excluded from the corpus of the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ due to the gods’ lack of attributes of the ‘stereotypical’ depiction of the ‘kriegerischer Gott”. While it is possible that they do depict the same god, there are too few identifying attributes to confidently do so.

3.2. Notable Scenes and Companions

3.2.1. The ‘kriegerische Ištar’

The ‘kriegerischer Gott’ is depicted fighting together with Inana/Ištar on Nos. 4 and 5.35 Legrain (1923, p. 146) describes the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ on No. 4 as a “divine attendant”, but especially when compared to No. 5, he and Inana/Ištar appear as equals. Inana/Ištar, while the goddess of war, is actually very rarely shown actively engaged in combat during the Akkadian Period.36 The grouping of the ‘kriegerische Ištar’ and the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ actively engaged in battle together against an enemy, therefore, appears to be crucially important.37 These two deities appear to be somehow related. While it is possible that these depictions may represent some narrative or oral tradition, it is more likely that two important martial deities are depicted together in their martial roles. This martial nature of the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ may also be indicated by the lion which appears to accompany the god in No. 3.38 The lion was often associated with warlike deities, with the power and ferocity of the lion being symbolic of the might of these deities.39

3.2.2. The Lion-Demon

The ‘kriegerischer Gott’ is depicted together with a lion-demon on No. 7.40 They are also depicted together on No. 6, but, as mentioned above, No. 6 likely does not belong to the corpus. In later periods, the lion-demon was called the ugallu or ūma rabû, the ‘big weather-beast’, and was a ‘Day Demon’, a type of demon which personified divine intervention in human affairs (Wiggermann 1992, p. 169; 2007, p. 111). However, these later lion-demons had different iconography to those of the Akkadian Period in that they had bird’s talons as feet and donkey’s ears. It is, therefore, possible that they represent different demons (Wiggermann 1992, p. 171). During the Akkadian Period, the lion-demon was represented together with the storm god,41 or as an enemy of a god with rays, usually identified as the sun god (Seidl 1989, p. 171; Wiggermann 1992, p. 171).42 Because of the association with the god with rays, Boehmer (1965, p. 58) suggests that the god who the lion-demon attacks in No. 7 should also be understood as this god, although depicted without the rays. Whether or not this is the case, the lion-demon appears to be associated with this god—the god he attacks—and not with the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ directly behind him. Therefore, although the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ and the lion-demon are both depicted on Nos. 6 and 7, the presence of the lion-demon cannot aid in the identification of this god: No. 6 should be excluded from the corpus of the ‘kriegerischer Gott’, and the lion-demon is not associated directly with the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ on No. 7.

3.2.3. The Enthroned God

On No. 8 the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ stands behind the enthroned god. The enthroned god is the focus of the presentation which suggests that he is the most important figure in the scene, and the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ is, therefore, of a subordinate position. There are no attributes to identify the seated god, which in turn could assist in an analysis of the ‘kriegerischer Gott’. Be this as it may, it is possible that the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ is a separate grouping from the presentation scene, and is, therefore, not associated with the enthroned god. This would be unusual for an Akkadian Period cylinder seal, but not unique.43

3.3. Possible Identity of the ‘kriegerischer Gott’

The ‘kriegerischer Gott’, therefore, exhibits many characteristics which are rare and which in combination are unique to him. This makes it likely that he can be identified as a specific, named god.

Frankfort (1934, 1939) has identified the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ as Ninurta,44 and when others have followed this identification, they have done so largely uncritically.45 There are, however, problems with Frankfort’s arguments. He identifies No. 3 and No. 5 as Ninurta and a goddess freeing Marduk from a mountain prison,46 and therefore, incorrectly identifies Utu/Šamaš in No. 3 and the enemy god in No. 5 as Marduk. The rest of Frankfort’s argument is based on this flawed identification. Furthermore, the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ and Inana/Ištar are clearly attacking the god in No. 5—an arrow which the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ has shot sticks out of the god’s stomach—and the scene can, therefore, not be a ‘rescue’. Frankfort (1934, p. 25) also incorrectly identifies the ‘kriegerischer Gott’s quiver with tassel as a lion’s skin, which he connects to Ninurta’s victory over Labbu. This identification is based on comparison to another Akkadian cylinder seal which does depict a figure wearing a lion’s skin, but this is clearly identifiable as such, with obvious lion’s paws.47 Additionally, the Slaying of Labbu is known from only one manuscript which dates to the Neo-Assyrian Period, nearly two millennia later, and there Labbu is described as a serpent.48 Furthermore, Frankfort (1939, p. 135) identifies the scene on No. 2—which should be excluded from the corpus of the ‘kriegerischer Gott’—as Ninurta’s battle against Anzu as described in the Anzu Myth, but this narrative is first recorded in the Old Babylonian Period, five centuries later.49 Frankfort’s arguments based on textual sources are, therefore, anachronistic, and there are also problems with his iconographic analyses. While Ninurta did have martial aspects, the identification of the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ as Ninurta based on Frankfort’s arguments is, therefore, untenable.50 Braun-Holzinger (1998–2001, p. 522) also states that the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ cannot be identified as Ninurta. Her reasoning is that the iconography of the ‘kriegerischer Gott’—specifically his en face depiction and long, loose hair—does not align with that of major Mesopotamian deities, who are usually depicted in profile and with their hair bound in buns. Inana/Ištar’s en face depictions argue against this, although it is largely accurate for gods. However, the en face depiction and long loose hair are features which can be understood as two of the attributes which mark the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ as a specific god.51 That he can be identified as a specific god speaks to his importance within the pantheon, although it is possible that he is an important god, but not a major god.52 Still, as an important martial god, Ninurta must remain a candidate for the ‘kriegerischer Gott’, although he is not the only candidate.

Aruz and Wallenfels (2003, p. 214) state that the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ “has not been identified with certainty but [he] may represent a hunting god like Nuska”,53 rather than a martial god. However, the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ is only depicted hunting (as opposed to fighting) on No. 6, and, as discussed above, this exemplar may be excluded from the corpus. Still, the possibility of the god being Nuska should be addressed. Nuska was a god of fire and light, and served as the vizier of Enlil (see Streck (1998–2001b)). If the enthroned god on No. 8 is Enlil, and if the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ is part of the presentation scene and, therefore, subordinate to the enthroned god, then he could be Nuska. However, Enlil has no known iconography, and it is, therefore, impossible to identify the enthroned god as Enlil. Furthermore, as a god of fire and light, it is more likely that Nuska would be depicted with attributes indicating this function, such as rays emerging form his shoulders. It is, therefore, unlikely that the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ is Nuska.

It is also possible that the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ represents Ilaba.54 Ilaba is first mentioned during the reign of Sargon, and virtually disappears in Mesopotamia after the Akkadian Period (Nowicki 2016, p. 68). He was the god of the capital city of Agade, and the protective deity of the Akkadian dynasty (Krebernik 2016–2018, p. 392). The latter is made clear in royal inscriptions which describe him as the personal god of both Sargon and Naram-Sîn,55 as well as their clan god.56 He was, therefore, an important deity, but it is also possible that his cult was limited to the Akkadian royal family (Nowicki 2016, p. 72). It is, therefore, possible that he could have been an important god to the Akkadian Empire, but not a major god of the pantheon. This would align with Braun-Holzinger’s assertion that the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ is not a major deity, while his unique iconography57 still indicates that he is an important god. Ilaba may have been considered the husband of Ištar-Annunitum, the martial manifestation of Inana/Ištar and the goddess of both Agade and the Akkadian Empire (Nowicki 2016, p. 68), just as Ilaba is the god of both Agade and the Akkadian Empire. These two deities are also mentioned together in Akkadian royal inscriptions, again in military contexts.,58 One of Šar-kali-šarri’s year names even mentions the building of the temples of Ilaba and Ištar-Annunitum together in Babylon, which again connects these two deities with each other.59 The depiction of the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ and Inana/Ištar in combat together against a foe on Nos. 4 and 5 would, therefore, fit this couple well—two martial deities who are repeatedly connected with each other in text and image. Ilaba seems to be the best fit for the ‘kriegerischer Gott’: a god of war who is explicitly associated with Inana/Ištar in martial contexts, who is amongst the most important deities of the Akkadian pantheon, but about whom relatively little is known, and who later disappears.

4. Conclusions

By re-examining the eight cylinder seals upon which Boehmer identified the ‘kriegerischer Gott’, new information has emerged. Because of his inclusion on No. 3 with some of the major deities of the Akkadian pantheon, the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ should likewise be an important god. This can be supported by his being the focus of praise on No. 1. Beohmer’s appellation of ‘kriegerischer Gott’ is apt; he carries weapons and is actively engaged in combat. It is probable that two of the eight exemplars in Boehmer’s catalogue, Nos. 2 and 6, do not represent this same god, and should, therefore, be excluded from the corpus of the ‘kriegerischer Gott’, although these two gods do also have clear martial attributes. The ‘kriegerischer Gott’ is consistently depicted with characteristic attributes which are rare for Akkadian Period deities: he is depicted en face, he clasps his hands before him holding weapons, he wears a quiver with a tassel on his back, he has long, loose hair, and he wears a slit skirt with a bundle at his waist. These features combine to form a unique iconography, which suggests that the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ is a specific, named individual. The traditional identification of this god as Ninurta is possible, but this investigation has uncovered concerns regarding this attribution, and has instead argued for another strong, potential candidate: Ilaba, the god of Agade and the Akkadian kings. The unique iconography of the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ aligns closely with what is known of Ilaba. Both the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ and Ilaba are martial gods, and both are explicitly and repeatedly associated with Inana/Ištar in her martial aspect. They are both important gods in the Akkadian Period and are known in Mesopotamia exclusively from this period. This analysis suggests the need to revisit and reanalyse some of Boehmer’s motifs which have been neglected since his seminal work. The same may be applied to other long-standing studies.

Funding

This research was conducted within the framework of a Mellon-funded postdoctoral research fellowship at the Department of Ancient and Modern Languages and Cultures in the Faculty of Humanities at the University of Pretoria.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | An earlier draft of this paper was presented at the 2023 ISBL in the ‘Ancient Near East’ session. My thanks to those who commented on that paper, particularly Terence Kleven. My thanks also to Alessandro Pezzati for the photograph of the seal impression from the Penn Museum; and to Alrun Gutow and Olaf M. Teβmer for the photographs of the two cylinder seals from the Vorderasiatisches Museum. I would also like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their helpful suggestions. |

| 2 | For example, by Liverani (1993b). There is, however, debate over what exactly constitutes an ‘empire’ and whether or not the Akkadian ‘Empire’ should be defined as an ‘empire’. This has been acknowledged by Liverani himself (Liverani 1993a, pp. 3–4). See Foster (2016, pp. 80–83) for a defence of the use of the term ‘empire’ for the Akkadian Empire. |

| 3 | For more on the Mesopotamian artefacts discovered at Susa, see Harper and Amiet (1992). See Amiet (1976) and Foster (2016, pp. 188–206) for the art of the Akkadian Period, and Eppihimer (2019) for the art of the Akkadian Period as well as its legacy. |

| 4 | For contest scenes during the Early Dynastic and Akkadian Periods, see Rohn (2011, pp. 14–52), and for full treatment on Akkadian Period contest scenes, see Rakic (2003). For banquet scenes during the Early Dynastic and Akkadian periods, see Selz (1983) and Rohn (2011, pp. 53–59). For depictions of deities during the Early Dynastic Period, see Braun-Holzinger (2013). |

| 5 | See Boehmer (1972–1975) for the ‘Hörnerkrone’ or horned headdress as a mark of divinity, and Collon (1982, pp. 30–31) for different types of horned headdress depicted on Akkadian Period cylinder seals. |

| 6 | Boehmer (1965, p. 70). This one page also includes a discussion on a ‘kriegerische Gottheit’, or martial deity, who is known from only one cylinder seal, AO 2879 (Boehmer 1965, Nr. 965; Delaporte 1920, Pl. 4.5 (T.87)). This deity is seated on two enemies which function as a throne, and they hold a weapon which has multiple weapon heads (spear points, mace heads) emanating from a central knob. By comparison to AO 4709 (Boehmer 1965, Taf. XXVI.299), which depicts Inana/Ištar seated on a throne composed of a mountain god and holding a similar weapon, the ‘kriegerische Gottheit’ can also be identified as this goddess. |

| 7 | Rohn (2011, p. 62 n. 487, p. 90 n. 776), briefly mentions the ‘kriegerischer Gott’but there are no substantive discussions on this figure other than Boehmer’s, which itself is only one page. |

| 8 | ‘Primary source’ refers to the most authoritative source, and not necessarily the first source, in which the object was published. When two primary sources are included, these are two different types of source, for example, excavation catalogue and museum catalogue, except on No. 4 where one of the sources does not include an image. |

| 9 | A ‘frontal’ figure’s entire body and head face towards the viewer, while only the head and upper body of an ‘en face’ figure do so (Asher-Greve and Westenholz 2013, p. 166 n. 680). ‘En face’ may also be termed ‘twisted profile’, see for example Sonik (2013, passim) and Bahrani (2001, p. 133). |

| 10 | Although it is not depicted with the usual scalloped pattern. See No. 3 for the scalloped pattern indicating mountains. Buchanan (1966, p. 63) identifies the object upon which the god rests his foot as a mountain with streams running down it, while Van Buren (1933, p. 25) suggests that it is a bough with roots and branches. |

| 11 | Both Sumerian and Akkadian names will be used because both were in use during the Akkadian Period. The Sumerian name will be first, and the Akkadian second. |

| 12 | Wings are often cited as a common attribute of Inana/Ištar, but she is actually rarely depicted with them. For more on this, see van Dijk-Coombes (2021, p. 36, and especially 36 n. 158). |

| 13 | See Colbow (1991) for the ‘kriegerische Ištar’. |

| 14 | Exactly what a ‘god’ in Mesopotamia was is complex and debated. See, for example, Hundley (2013) and the contributions in Porter (2009). |

| 15 | No. 8 is simply cut and the lines on either side of the gods face may represent either his hair, or the weapons, or possibly both. |

| 16 | Although it must be noted that on Nos. 4 and 7 he is en face while fighting. |

| 17 | Note here Asher-Greve (2006, p. 35), who observes that en face depictions are “rare and exceptional” and that it is “astonishing that frontality [including en face representation] appears so rarely in third-millennium Mesopotamian imagery”. |

| 18 | For Inana/Ištar depicted en face, see for example, on Nos. 3, 4 and 5. |

| 19 | For example, Utu/Šamaš, who is the most commonly depicted god on Akkadian Period cylinder seals and is of “high status and importance” is very rarely shown en face. See AO 2280 (Boehmer 1965, Taf.XXXIII.393) for an en face depiction Utu/Šamaš. |

| 20 | It must be noted that not all en face gods whose identities are uncertain should be considered to be the ‘kriegerischer Gott’. For example, two en face figures who each hold two staffs which resemble the weapons held by the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ on Nos. 1, 3 and 8 are depicted on YBC 16396 (Buchanan 1981, pp. 175, 176.455). These two figures superficially resemble the ‘kriegerischer Gott’, but they and similar figures can be discounted as such due to their lack of the other attributes of the ‘kriegerischer Gott’—the quiver with tassel, the long, loose hair and the slit skirt with bundle. |

| 21 | See Note 20. |

| 22 | As noted by Boehmer (1965, p. 70), “Bogen und Köcer hat er … mit einer Keule vertauscht”. |

| 23 | See for example the stele from the reign of Rimuš AO 2678 (Amiet 1976, p. 90 no. 25a), and the seal of Kalki BM 89,137 (Collon 1982, Pl. XX.141). |

| 24 | It is worn by an archer on BM 129602 (Collon 1982, Pl.XVIII.127; Boehmer 1965, Taf.XXV.288), but it is unclear whether this archer is a human or a god. See below for more on this seal. |

| 25 | See, for example, BM 122557 (Collon 1982, Pl.XXI.150) and BM 120,962 (Collon 1982, Pl. XXV.173) for depictions of other gods with long loose hair. |

| 26 | See for example Boehmer (1965, Tafs.XXXIV–XXXVI) for Utu/Šamaš wearing a slit skirt both with and without the bundle. In these depictions, Utu/Šamaš’s leg is raised and is resting on a mountain. |

| 27 | For example, when the god does not hold his weapons in front of him in Nos. 2, 5, 6 and 7, it is because he is actively involved in combat, and in No. 7, he does not wear the quiver with tassel because he is not holding a bow. |

| 28 | No. 6 is also discussed by Boehmer (1965, pp. 60–61, Taf XXX:356–361) as part of the group of seals which depict the ‘Tötung eines Stieres’—the killing of a bull. However, No. 6 is the only such scene in which the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ appears; usually two figures attack the bull, and they use daggers or maces, rather than a bow and arrow. I am, therefore, disinclined to consider No. 6 as part of this group. |

| 29 | BM 129602 (Collon 1982, Pl.XVIII.127; Boehmer 1965, Taf.XXV.288). |

| 30 | BM 122127 (Collon 1982, Pl.XVIII.128; Boehmer 1965, Taf.XXV.289). |

| 31 | See also Rohn (2011, p. 90 n. 776) who notes Boehmer’s identification of the god on No. 6 as the ‘kriegerischer Gott’, but does not use the term “[d]a der (mythologische?) Hintergrund dieser “Jagd” nicht zu erschlieβen ist”. |

| 32 | See Boehmer (1965, Taf.XXVII.323, 325, Taf.XXVIII.334–336) and Buchanan (1966, Pl.26.329). |

| 33 | Although Anzu rather than the large bird is depicted in only one of this type of scene, this being a seal from Tell Asmar, see Ornan (2010, p. 417 Figure 15). The consistent representation of Anzu as a lion-headed eagle from the Early Dynastic Period would otherwise argue against these scenes being equated. See Fuhr-Jaeppelt (1972) for a full treatment of Anzu in the visual record. |

| 34 | Van Buren’s identification is based on Ashurbanipal’s Acrostic Hymn to Marduk and Zarpanitu line 15, which identifies Marduk as the “smiter of the skull of Anzû” (Livingstone 1989, p. 7), but this hymn is nearly two millennia later than the Akkadian Period cylinder seals. See below for Frankfort’s identification. |

| 35 | These two deities are also depicted together on No. 3, but it is unclear if this represents a specific scene or episode, or merely five important deities being depicted together. |

| 36 | I am aware of only two other examples. A cylinder seal from Ur, IM 11091 (Boehmer 1965, Taf.XXXIX.341) has a grouping similar to that on No. 5 in that Inana/Ištar and a god overpower an enemy god who is seated on a mountain. However, the accompanying god in this example has none of the identifying attributes of ‘stereotypical’ ‘kriegerischer Gott’. By comparison to No. 5, it is possible that he may also be identified as this god, but this seal has been excluded from the discussion due to the lack of identifying attributes. Inana/Ištar is also depicted trampling a mountain god on AO 11569 (Boehmer 1965, Taf.XXXII.379). This scene may be related to Inana and Ebiḫ, in which Inana fights and defeats the mountain/god Ebiḫ, see van Dijk-Coombes (2021, pp. 33–34). |

| 37 | This may be further supported by the fact that this grouping constitutes either a third or a quarter of the corpus, depending on whether Nos. 2 and 6 are considered to represent the ‘kriegerischer Gott’. |

| 38 | It is also possible that the lion is a filler motif beneath the inscription. Such fillers are not unknown; for example, a lion is also beneath the inscription on No. 7, while an ibex is beneath the inscription on VA 243 (Boehmer 1965, Taf.XLVI.548) and a bird is beneath the inscription on VA 3605 (Boehmer 1965, Taf.XXIV.274). In these examples the animal has nothing obvious to do with the scene on the seal, and this may also be the case for No. 3. |

| 39 | See Strawn (2005) for a discussion on the lion as a symbol of strength in ancient Western Asia. |

| 40 | For more on the lion-demon, see Green (1986), Seidl (1989, pp. 171–75, as “Löwenmensch”), and Wiggermann (1992, pp. 169–72). |

| 41 | See VA 611 (Boehmer 1965, Taf. XXVIII.333). |

| 42 | The god with rays cannot be identified as the sun god Utu/Šamaš in all instances. See for example Hermitage 6587 (Boehmer 1965, Taf.XXXVIII.461), IM 14577 (Boehmer 1965, Taf.XLI.488), Yale NCBS 154 (Boehmer 1965, Taf.XXIX.339), and Penn Museum B16876 (Boehmer 1965, Taf.XXIX.340) upon which two gods with rays emerging from their shoulders are depicted together on the same seal. Because two gods are depicted together with rays on the same seal, they cannot both be the same god. |

| 43 | See for example No. 4 and AO 11569 (Boehmer 1965:Taf.XXXII.379) for two groupings of deities. |

| 44 | For No. 2 (Frankfort 1939, p. 135), No. 3 (Frankfort 1934, p. 25; 1939, p. 107), No. 5 (Frankfort 1934, p. 27; 1939, p. 107). |

| 45 | See, for example, Pritchard (1969, p. 332). |

| 46 | In No. 5, he incorrectly identifies Inana/Ištar as a fertility goddess. He differentiates this fertility goddess from “the goddess of war” (i.e., Inana/Ištar), but the goddess in No. 5 holds a dagger, and therefore, must be Inana/Ištar. |

| 47 | BM 129479 (Collon 1982, Pl. XXXI.213). |

| 48 | See Lambert (2013, pp. 361–65) for this narrative. |

| 49 | For this narrative, see Wiggermann (1982, pp. 418–20). |

| 50 | Ninurta also exhibits some aspects of a storm god, and in this regard, Jacobsen (1976, p. 255) identifies this god on No. 3 as Ninurta due to “his bow (its arrows typifying lightning) and his lion (whose roar typifies thunder)”. However, having some of the same characteristics as a storm god does not automatically make a god a storm god, and Ninurta is usually not considered to be primarily a storm god. See Streck (1998–2001a, p. 517) and most recently Dietz (2023, p. 58). |

| 51 | With the other identifying attributes, at least for the ‘stereotypical depiction’, being his slit skirt, the weapons which he clasps before him, and the quiver with the tassel. |

| 52 | For an example of this distinction, see Isimud/Usmu, who is also depicted on No. 3. As Enki/Ea’s vizier, he was not a major god of the pantheon because he was in a subordinate position to Enki/Ea, but he was nonetheless an important deity. |

| 53 | Collon (2005, p. 165) also describes him as a “hunting god” but does not identify him as Nuska. |

| 54 | See Nowicki (2016) for a full treatment of Ilaba. |

| 55 | A royal inscription from the reign of Sargon reads, “[t]he god Ilaba (is) his [i.e Sargon’s] (personal) god” (RIME 2.1.1.3, 1–2, Frayne 1993, p. 16), while a royal inscription from Naram-Sîn’s reign states, “so they [i.e., enemies which Naram-Sîn has conquered] perform service for the god Ilaba, his [i.e., Naram-Sîn’s] god” (RIME 2.1.4.26 ii 20–23, Frayne 1993, p. 133). |

| 56 | A royal inscription from Naram-Sîn’s reign reads that “the god Ilaba, mighty one of the gods, is his [i.e., Naram-Sîn’s] clan (god)” (RIME 2.1.4.6 i 3–5, Frayne 1993, p. 104). |

| 57 | Including not only his unique identifying attributes, but also his being depicted together with other important deities on No. 3 and his being the centre of worship on No. 1. |

| 58 | See for example an inscription of Naram-Sîn which reads “those whom he … and [led off] before the mace of the gods Ilaba and Aštar [i.e., Ištar-Annunitum]” (RIME 2.1.4.1, vi 4’-7’, Frayne 1993, p. 89). See also the letter from Iškun-Dagan in which he demands that Puzur-Ištar swear by these two deities (Foster 2005, p. 69). |

| 59 | This year name reads, “[t]he year [Šar-k]ali-šarri laid [the foundation] of the temple of the goddess Annunītum and the temple of the god Ilaba in Babylon, and captured Šarlak, king of Gutium” (Frayne 1993, p. 183 iii.k). |

References

- Amiet, P. 1976. L’art d’Agadé en Musée du Louvre. Paris: Éditions des Musées Nationaux. [Google Scholar]

- Aruz, J., and R. Wallenfels, eds. 2003. Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. [Google Scholar]

- Asher-Greve, J. M. 2006. The Gace of Goddesses: On Divinity, Gender, and Frontality in the Late Early Dynastic, Akkadian, and Neo-Sumerian Periods. NIN 4: 1–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asher-Greve, J. M., and J. Goodnick Westenholz. 2013. Goddesses in Context: On Divine Powers, Roles, Relationships and Gender in Mesopotamian Textual and Visual Sources. OBO 259. Fribourg: Fribourg Academic Press. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [Google Scholar]

- Bahrani, Z. 2001. Women of Babylon: Gender and Representation in Mesopotamia. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Boehmer, R. M. 1965. Die Entwicklung der Glyptik während der Akkad-Zeit. UAVA 4. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Boehmer, R. M. 1972–1975. Hörnerkrone. RlA 4: 431–34. [Google Scholar]

- Braun-Holziner, E.A. 1993. Die Ikonographie des Mondgottes in der Glyptik des III. Jahrtausends v. Chr. ZA 83: 119–133. [Google Scholar]

- Braun-Holzinger, E. A. 1998–2001. Ninurta/Ninĝirsu. B. In der Bildkunst. RlA 9: 522–24. [Google Scholar]

- Braun-Holzinger, E. A. 2013. Frühe Götterdarstellungen in Mesopotamien. OBO 261. Fribourg: Academic Press Fribourg. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan, B. 1966. Catalogue of Ancient Near Eastern Seals in the Ashmolean Museum; Volume 1: Cylinder Seals. Oxford: Clarendon. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan, B. 1981. Early Near Eastern Seals in the Yale Babylonian Collection. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Colbow, G. 1991. Die Kriegerische Ištar. Zu den Erscheinungsformen bewaffneter Gottheiten zwischen der Mitte des 3. und der Mitte des 2. Jahrtausends. Münchener Universitäts-Schriften Philopophische Fakultät 12. Münchener Vorderasiatische Studien Herausgaben von Barthel Hrouda Band VIII. München: Profil Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Collon, D. 1982. Catalogue of the Western Asiatic Seals in the British Museum: Cylinder Seals II: Akkadian, Post Akkadian, Ur III periods. London: British Museum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Collon, D. 2005. First Impressions: Cylinder Seals in thh Ancient Near East. London: British Museum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Delaporte, L. 1920. Catalogue des Cylindres Orientaux: Cachets et Pierres Gravées de Style Oriental. Vol. I: Fouilles et Missions. Paris: Libraire Hachette. [Google Scholar]

- Dietz, A. 2023. Der Wettergott im Bild: Diachrone Analyse eines altorientalischen Göttertypus im 3. und 2. Jahrtausend v. Chr. MAAO 8. Gladbeck: PeWe-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Eppihimer, M. 2019. Exemplars of Kingship: Art, Tradition, and Legacy of the Akkadians. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, B. R. 2005. Before the Muses: An Anthology of Akkadian Literature. Bethesda: CDL Press. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, B. R. 2016. The Age of Agade: Inventing Empire in Ancient Mesopotamia. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Frankfort, H. 1934. Gods and Myths on Sargonid Seals. Iraq 1: 2–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankfort, H. 1939. Cylinder Seals: A Documentary Essay on the Art and Religion of the Ancient Near East. London: MacMillan & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Frayne, D. 1993. Sargonic and Gutian Periods (2344–2133 BC). RIME 2. Toronto, Buffalo and London: University of Toronto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fuhr-Jaeppelt, I. 1972. Materialen zur Ikonographie des Löwenadlers Anzu-Imdugud. München: Scharl + Strohmeyer. [Google Scholar]

- Green, A. 1986. The Lion-Demon in the Art of Mesopotamia and Neighbouring Regions. BaM 17: 141–254. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, D. 2003. Art of the Akkadian Dynasty. In Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus. Edited by J. Aruz and R. Wallenfels. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, pp. 189–98. [Google Scholar]

- Harper, P. O., and P. Amiet. 1992. The Mesopotamian Presence. In The Royal City of Susa: Ancient Near Eastern Treasures in the Louvre. Edited by P. O. Harper, J. Aruz and F. Tallon. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, pp. 159–82. [Google Scholar]

- Hundley, M. B. 2013. Here a God, There a God: An Examination of the Divine in Ancient Mesopotamia. AoF 40: 68–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, T. 1976. The Treasures of Darkness: A History of Mesopotamian Religion. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Krebernik, M. 2016–2018. Ilaba. RlA 15: 392–97. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert, W.G. 2013. Babylonian Creation Myths. Mesopotamian Civilizations 16. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. [Google Scholar]

- Legrain, L. 1923. Some Seals of the Babylonian Collections. The University Museum 14: 35–161. [Google Scholar]

- Legrain, L. 1925. The Culture of the Babylonians from their Seals in the Collections of the Museum. Publications of the Babylonian Section XIV. Philadelphia: The University Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Liverani, M. 1993a. ‘Akkad: An Introduction. In Akkad: The First World Empire: Structure, Ideology, Traditions. Edited by M. Liverani. HANES 5. Padova: Sargon, pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Liverani, M., ed. 1993b. Akkad: The First World Empire: Structure, Ideology, Traditions. HANES 5. Padova: Sargon. [Google Scholar]

- Livingstone, A. 1989. Court Poetry and Literary Miscellanea. SAA III. Helsinki: Helsinki University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moortgat, A. 1966. Vorderasiatische Rollsiegel: Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der Steinschneidekunst. Berlin: Gebr. Mann Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Nowicki, S. 2016. Sargon of Akkade and his God: Comments on the Worship of the God of the Father among the Ancient Semites. AOASH 69: 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ornan, T. 2010. Humbaba, the Bull of Heaven and the Contribution of Images to the Reconstruction of the Giglameš Epic. In Gilgamesch: Ikonographie eines Helden/Gilgamesh: Epic and Iconography. Edited by H. U. Steymans. OBO 245. Fribourg: Fribourg Academic Press, Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, pp. 229–60, 411–24. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, B. N. 2009. What Is a God? Anthropomorphic and Non-Anthrophomorphic Aspects of Deity in Ancient Mesopotamia. Transactions of the Casco Bay Assyriological Institute 2. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard, J. B. 1969. The Ancient Near East in Pictures Relating to the Old Testament. Second Edition with Supplement. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rakic, Y. 2003. The Contest Scene in Akkadian Glyptic: A Study of its Imagery and Function within the Akkadian Empire. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Rohn, K. 2011. Beschriftete mesopotamische Siegel der Frühdynastischen und der Akkad-Zeit. OBO 32. Fribourg: Academic Press Fribourg. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [Google Scholar]

- Seidl, U. 1989. Die babylonischen Kudurru-Reliefs: Symbole mesopotamischer Gottheiten. OBO 87. Fribourg: Fribourg Academic Press. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [Google Scholar]

- Selz, G. 1983. Die Bankettszene: Entwicklung eines überzeitlichen Bildmotivs in Mesopotamien. Von der Frühdynastischen bis zur Akkadzeit. FAOS 11. Wiesbaden: F. Steiner. [Google Scholar]

- Sonik, K. 2013. The Monster’s Gaze: Vision as Mediator between Time and Space in the Art of Mesopotamia. In Time and Space in the Ancient Near East. Paper presented at the 56th Rencontre Assyriologique at Barcelona, 26–30 July 2010. Edited by L. Feliu, J. Llop, A. M. Albà and J. Sanmartin. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, pp. 285–300. [Google Scholar]

- Strawn, B. A. 2005. What is Stronger than a Lion? Leonine Image and Metaphor in the Hebrew Bible and the Ancient Near East. OBO 212. Fribourg: Fribourg Academic Press. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [Google Scholar]

- Streck, M. P. 1998–2001a. Ninurta/Ninĝirsu. A. I. In Mesopotamien. RlA 9: 512–22. [Google Scholar]

- Streck, M. P. 1998–2001b. Nuska. RlA 9: 629–33. [Google Scholar]

- Van Buren, E. D. 1933. The Flowing Vase and the God with Streams. Berlin: Hans Schoetz & Co. [Google Scholar]

- van Dijk-Coombes, R. M. 2021. The Many Faces of Enheduanna’s Inana: Literary Images of Inana and the Visual Culture from the Akkadian to the Old Babylonian Period. In From Stone Age to Stellenbosch: Studies on the Ancient Near East in Honour of Izak (Sakkie) Cornelius. Edited by R. M. van Dijk-Coombes, L. C. Swanepoel and G. Kotzé. ÄAT 107. Münster: Zapohn, pp. 25–44. [Google Scholar]

- van Dijk-Coombes, R. M. 2023. The Standards of Mesopotamia in the Third and Fourth Millennia BCE: An Iconographic Study. ORA 52. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. [Google Scholar]

- Wiggermann, F. A. M. 1982. On BIN ŠAR DADMĒ, the “Anzû-Myth”. In ZIKIR ŠUMIM: Assyriological Studies Presented to F.R. Kraus on the Occasion of His Seventieth Birthday. Edited by G. van Driel, T. J. H. Krispijn, M. Stol and K. R. Veenhof. Leiden: Brill, pp. 418–25. [Google Scholar]

- Wiggermann, F. A. M. 1992. Mesopotamian Protective Spirits: The Ritual Texts. CM 1. Groningen: Styx & PP Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Wiggermann, F. A. M. 2007. Some Demons of Time and their Functions in Mesopotamian Iconography. In Die Welt der Götterbilder. Edited by B. Groneberg and H. Spieckermann. BZAW 376. Berlin and New York: De Gruyter, pp. 102–16. [Google Scholar]

- Woolley, L. 1934. The Royal Cemetery. UE II. New York: The Carnegie Corporation. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).