The Anointed Steward: A Critical Review of Western Christian and Secular Steward Leadership Literature

Abstract

:1. The Role of the Steward

2. Research Statement and Motivation

2.1. Critical Literature Review Process

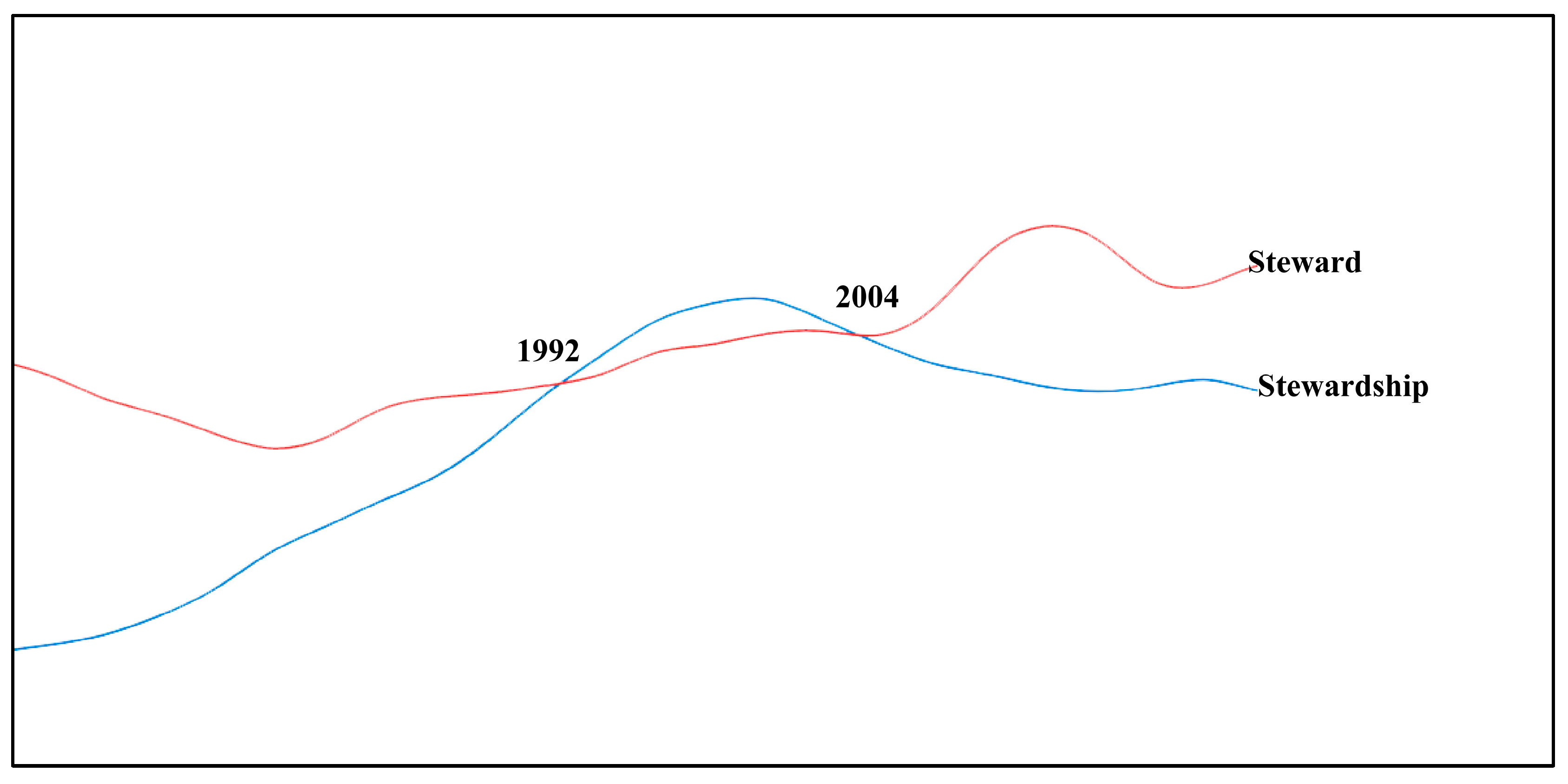

2.2. Examination of Steward Leadership as a Passing Fad

2.3. Introducing a Conceptual Filtering Tool

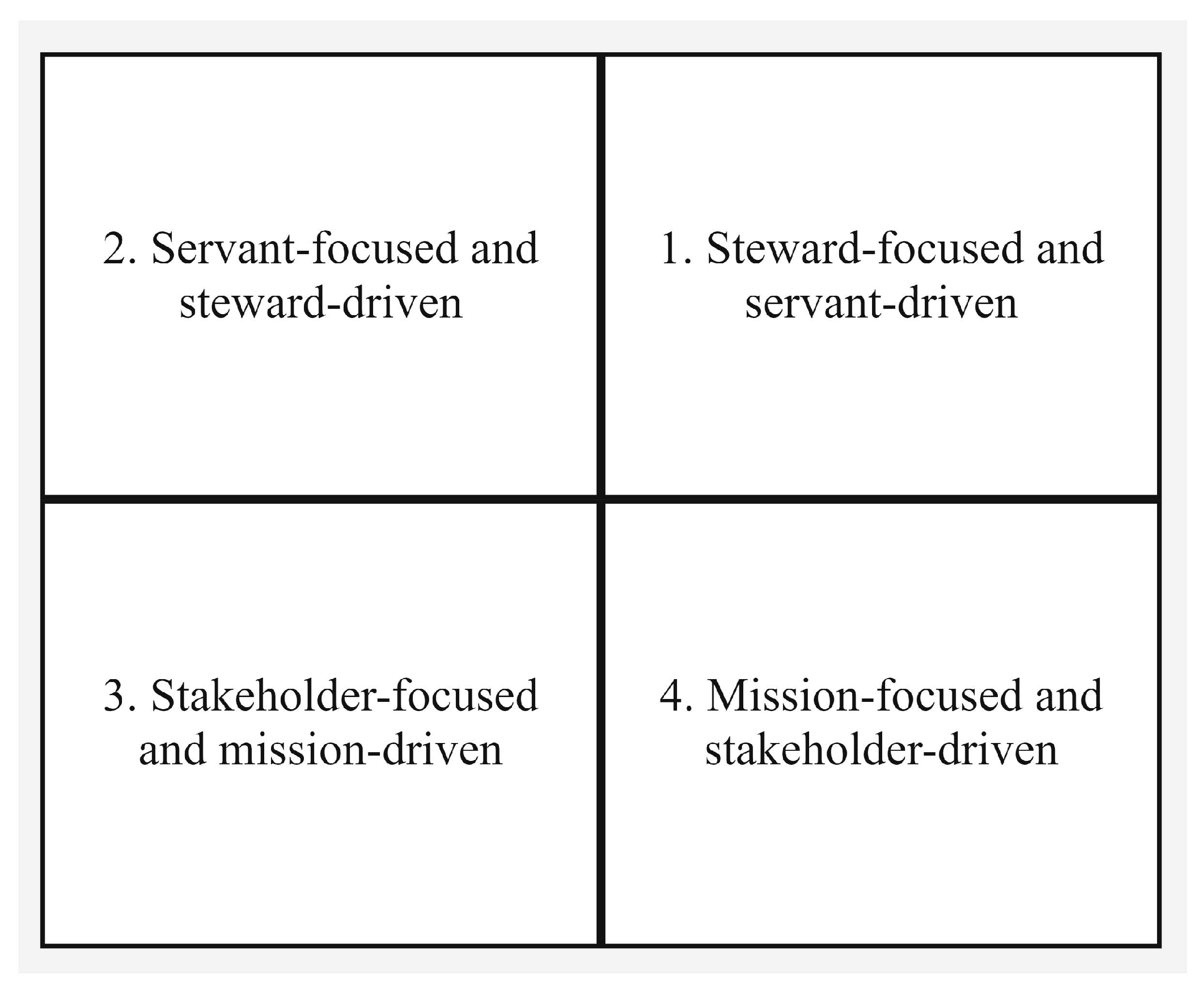

3. Being Focused and Driven as a Steward Leadership Modality

3.1. Data-Driven Research Specific to Steward Leadership

3.2. The Entanglement of Steward and Servant Leadership

Greenleaf established servant leadership in the original essay inspired by Hesse’s (2003) famous mystical novel The Journey to the East, in which the servant Leo leaves an expedition in a hostile jungle, resulting in extreme chaos and an experience that provides lessons in humility and transcendence (Spears 2005).Caring for persons, the more able and less able serving each other, is the rock upon which a good society is built. If a better society is to be built, one that is more just and more loving, and provides greater creative opportunity for its people, then the most open course is to raise both the capacity to serve and the very performance, as servant, of existing institutions by new regenerative forces operating within them.(p. 9)

3.3. The Focus and Drive of a Secular Steward Leader

4. Governance Being Focused and Driven as Stewardship Theory

Stewardship Theory as the Solution to Defection

5. Conclusions and Call for Future Research

Call for Future Research

- How does steward leadership grow in both Western Christian and secular domains?

- Can there be a greater adoption of secular stewardship data and theories that can positively influence and yet allow the maintenance of Western Christian traditions?

- Can academic reciprocity of steward leadership research exist?

- How does steward leadership make organizations more anti-fragile to catastrophic forces like 9/11 or COVID-19?

- How does steward leadership reconcile with progressive subjects, such as gender and intersectionality?

- How does steward leadership reconcile with stewardship from other religious traditions?

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Afifuddin, Hasan Basri, and Abdul Khalid Siti-Nabiha. 2010. Towards good accountability: The role of accounting in Islamic religious organizations. World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology 42: 1366–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albanese, Robert, M. Tina Dacin, and Ira C. Harris. 1997. Agents as stewards. The Academy of Management Review 22: 609–11. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/259406 (accessed on 25 February 2023). [CrossRef]

- April, Kurt, Julia Kukard, and Kai Peters. 2013. Steward Leadership: A Maturational Perspective. Cape Town: UCT Press. [Google Scholar]

- April, Kurt, Kai Peters, and Christian Allison. 2010. Stewardship as leadership: An empirical investigation. Effective Executive 13: 52–69. Available online: http://bit.ly/3T0OfcM (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Ariza-Montes, Antonio, Gabriele Giorgi, Horacio Molina-Sánchez, and Javier Fiz Pérez. 2020. Editorial: The Future of Work in Non-profit and Religious Organizations: Current and Future Perspectives and Concerns. Frontiers in Psychology 11: 623036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astuti, Sih Darmi, Ali Shodikin, and Ud-Din Maaz. 2020. Islamic leadership, Islamic work culture, and employee performance: The mediating role of work motivation and job satisfaction. Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business 7: 1059–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, Bruce J., Fred O. Walumbwa, and Todd J. Weber. 2009. Leadership: Current theories, research, and future directions. Annual Review of Psychology 60: 422–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelrod, Robert, and William D. Hamilton. 1981. The evolution of cooperation. Science 211: 1390–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, Ken. 2003. Servant Leader. Nashville: Thomas Nelson. [Google Scholar]

- Block, Peter. 1996. Stewardship: Choosing Service over Self Interest. Oakland: Berrett-Koehler Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Boell, Sebastian K., and Dubravka Cecez-Kecmanovic. 2014. A hermeneutic approach for conducting literature reviews and literature searches. Communications of the Association for Information Systems 34: 257–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinckerhoff, Peter C. 2004. Non-Profit Stewardship: A Better Way to Lead Your Mission-Based Organization. St. Paul: Fieldstone Alliance. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, James MacGregor. 1978. Leadership. New York: Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell, Cam, Linda A. Hayes, Patricia Bernal, and Ranjan Karri. 2008. Ethical stewardship—Implications for leadership and trust. Journal of Business Ethics 78: 153–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, Chun Wei. 2005. Information failures and organizational disasters. MIT Sloan Management Review 46: 8–10. Available online: http://bit.ly/3ZzTkLz (accessed on 21 February 2022).

- Clinton, James Robert. 1988. Leadership Development Theory: Comparative Studies among High Level Christian Leaders. Pasadena: Fuller Theological Seminary, vol. 8914721, Available online: http://bit.ly/3J12KbR (accessed on 19 February 2023).

- Clinton, James Robert. 1989. Leadership Emergence Theory: A Self-Study Manual for Analyzing the Development of a Christian leader. Altadena: Barnabas Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Cosenza, Elizabeth. 2007. The holy grail of corporate governance reform: Independence or democracy? Brigham Young University Law Review 2007: 1–54. Available online: http://search.proquest.com/docview/194360886?accountid=26357 (accessed on 21 July 2021).

- Covey, Stephen R. 1997. The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People: Restoring the Character Ethic. Omaha: G.K. Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, John W., and J. David Creswell. 2018. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Crippen, Carolyn. 2010. Greenleaf’s servant-leadership and Quakerism: A nexus. The International Journal of Servant-Leadership 6: 199–211. Available online: http://bit.ly/3mCkSBw (accessed on 21 January 2023). [CrossRef]

- Davis, James H., F. David Schoorman, and Lex Donaldson. 1997a. Davis, Schoorman, and Donaldson Reply: The distinctiveness of agency theory and stewardship theory. The Academy of Management Review 22: 611–13. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/259407 (accessed on 30 August 2020).

- Davis, James H., F. David Schoorman, and Lex Donaldson. 1997b. Toward a stewardship theory of management. The Academy of Management Review 22: 20–47. Available online: http://bit.ly/41VPQok (accessed on 9 October 2020). [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, Lex. 2005. Following the scientific method: How I became a committed functionalist and positivist. Organization Studies 26: 1071–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, Lex, and James H. Davis. 1991. Stewardship theory or agency theory: CEO governance and shareholder returns. Australian Journal of Management 16: 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, Kathleen M. 1989. Agency theory: An assessment and review. Academy of Management Review 14: 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exploding Topics. 2023. Exploding Topics—Discover the Hottest New Trends. Exploding Topics. Available online: https://explodingtopics.com/ (accessed on 25 February 2023).

- Fama, Eugene F., and Michael C. Jensen. 2019. Separation of ownership and control. Corporate Governance: Values, Ethics and Leadership 26: 163–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, Daniel. 1998. The biblical tradition of anointing priests. Journal of Biblical Literature 117: 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R. Edward. 2001. A stakeholder approach to strategic management. Analysis 1: 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadamer, Hans-Georg. 2018. Hermeneutics between History and Philosophy: The Selected Writings of Hans-Georg Gadamer. Translated by Arun Iyer, and Pol Vandevelde. London: Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, Jane Whitney. 2001. Management fads: Emergence, evolution, and implications for managers. Academy of Management Executive 15: 122–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, Jane Whitney, Dana V. Tesone, and Charles W. Blackwell. 2003. Management Fads: Here Yesterday, Gone Today? S.A.M. Advanced Management Journal 68: 12–17. Available online: http://bit.ly/3yr40Aq (accessed on 29 January 2023).

- Google Trends. 2023. Google Trends. Available online: https://trends.google.com/trends/?geo=US (accessed on 29 January 2023).

- Grant, Maria J., and Andrew Booth. 2009. A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information and Libraries Journal 26: 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenleaf, Robert K. 2007. The servant as leader. In Corporate Ethics and Corporate Governance. Edited by Walter Christoph Zimmerli, Markus Holzinger and Klaus Richter. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundei, Jens. 2008. Are managers agents or stewards of their principals? Logic, critique, and reconciliation of two conflicting theories of corporate governance. Journal Fur Betriebswirtschaft 58: 141–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesse, Hermann. 2003. The Journey to the East: A Novel. Edited by Hilda Rosner. New York: St Martins Press. [Google Scholar]

- Huczynski, Andrzej. 2012. Management Gurus, Revised Edition. Abingdon: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, Mark. 2016. Leading changes: Why transformation explanations fail. Leadership 12: 449–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, Michael C., and William H. Meckling. 2019. Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. In Corporate Governance: Values, Ethics and Leadership. Edited by Robert Ian Tricker. Abingdon: Taylor & Francis Group, pp. 77–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesson, Jill K., and Fiona M. Lacey. 2006. How to do (or not to do) a critical literature review. Pharmacy Education 6: 139–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Melvin C. 2019. Life and Times of John Pierce Hawley: A Mormon Ulysses of the American West. Sandy: Greg Kofford Books. [Google Scholar]

- Katsande, Farai. 2021. Developing Transforming Steward Leadership Scientifically Validated Measurement Instrument (Publication No. 28869829). Ph.D. dissertation, Regent University, Virginia Beach, VA, USA. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global. Available online: http://bit.ly/3kSoOO9 (accessed on 25 February 2023).

- Katsande, Farai, Debra Dean, William Dave Winner, and Bruce E. Winston. 2022. Developing the transforming steward leadership questionnaire scientifically validated measurement instrument. International Leadership Journal 14: 85–114. Available online: http://bit.ly/41VT7nC (accessed on 25 February 2023).

- Kuckartz, Udo, and Stefan Rädiker. 2019. Analyzing qualitative data with MAXQDA. In Analyzing Qualitative Data with MAXQDA. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulik, Brian W. 2004. Agency theory, reasoning and culture at Enron: In search of a solution. Journal of Business Ethics 59: 347–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, Yvonna S., and Egon G. Guba. 1986. But is it rigorous? Trustworthiness and authenticity in naturalistic evaluation. New Directions for Program Evaluation 1986: 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, Brian. 1978. The selective usefulness of game theory. Social Studies of Science 8: 85–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, Gerald R. 2009. God’s Rivals: Why Has God Allowed Different Religions? Insights from the Bible and the Early Church. Westmont: InterVarsity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Means, Gardiner, and Adolf Berle. 2017. The Modern Corporation and Private Property. Abingdon: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2023. Statue of the High Steward Gebu in a Cross-Legged Pose. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Available online: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/591298 (accessed on 21 January 2023).

- Miron-Spektor, Ella, and Miriam Erez. 2017. Looking at creativity through a paradox lens: Deeper understanding and new Insights. In Handbook of Organizational Paradox: Approaches to Plurality, Tensions and Contradictions. Edited by Wendy K. Smith and Marianne W. Lewis. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagarajan, Karatholuvu. 2011. The Code of Hammurabi: An economic interpretation. International Journal of Business and Social Science 2: 109–17. Available online: http://bit.ly/3JnApOw (accessed on 12 February 2023).

- Niewold, Jack. 2007. Beyond servant leadership. Journal of Biblical Perspectives in Leadership 1: 118–34. Available online: http://bit.ly/3J5AhSa (accessed on 19 February 2023).

- Omura, Teruyo, and John Forster. 2014. Competition for donations and the sustainability of not-for-profit organizations. Humanomics 30: 255–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizaldy, Muhamad Rizky, and Maulana Syarif Hidayatullah. 2021. Islamic leadership values: A conceptual study. Dialogia 19: 88–104. Available online: https://jurnal.iainponorogo.ac.id/index.php/dialogia/article/view/2589 (accessed on 4 September 2023).

- Rodin, R. Scott. 2010. The Steward Leader: Transforming People, Organizations and Communities. Westmont: InterVarsity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rondi, Emanuela, Carlotta Benedetti, Cristina Bettinelli, and Alfredo De Massis. 2023. Falling from grace: Family-based brands amidst scandals. Journal of Business Research 157: 113637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt-Jessa, Katarzyna, and Mateusz Gajtkowski. 2021. Secular stagnation and google trends can we find out what people think? Review of Economic Analysis 13: 293–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergiovanni, Thomas J. 1996. Moral Leadership: Getting to the Heart of School Improvement. Hoboken: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Shupak, Nili. 1992. A new source for the study of the judiciary and law of ancient Egypt: “The tale of the eloquent peasant”. Journal of Near Eastern Studies 51: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparavigna, Amelia C., and Roberto Marazzato. 2015. Using Google Ngram Viewer for Scientific Referencing and History of science. arXiv arXiv:1512.01364. Available online: https://arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv/papers/1512/1512.01364.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- Spears, Larry C. 1991. Robert K. Greenleaf: Servant-leader. Friends Journal 8: 20–21. Available online: https://www.friendsjournal.org/1991129/ (accessed on 19 February 2023).

- Spears, Larry C. 2005. The understanding and practice of servant-leadership. Regent University School of Leadership Studies 2005: 1–8. Available online: http://bit.ly/3mFhqpv (accessed on 30 August 2020). [CrossRef]

- van Dierendonck, Dirk. 2011. Servant leadership: A review and synthesis. Journal of Management 37: 1228–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VERBI Software. 2022. MAXQDA Analytics Pro 2022 (Release 22.7.0) [Computer Software]. Available online: https://www.maxqda.com/ (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Von Neumann, John. 2020. Theory of Games and Economic Behavior. New York: Sidney Bond. [Google Scholar]

- Watts, Niki. 2008. The Oxford New Greek Dictionary: Greek-English, English-Greek. New York: Berkley Books. [Google Scholar]

- Willis, Paul. 2019. Retroduction, reflexivity and leadership learning: Insights from a critical realist study of empowerment. Management Learning 50: 449–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, Andrew, Gilbert Lenssen, and Patricia Hind. 2006. Leadership Qualities and Management Competencies for Corporate Responsibility. In Ashridge Report 2006. Hertfordshire: Ashridge. Available online: https://bit.ly/3LqoGzm (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Wilson, Kent R. 2010. Steward Leadership: Characteristics of the Steward Leader in Christian Non-Profit Organizations. Ph.D. dissertation, The University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen, UK. Available online: http://bit.ly/3T2oWH9 (accessed on 25 August 2020).

- Wilson, Kent R. 2016. Steward Leadership in the Non-Profit Organization. Westmont: InterVarsity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ziolkowski, Theodore. 2003. A celebration of Hermann Hesse. World Literature Today 77: 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Code | #Codes | #Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Agency | 10 | 17 |

| Fad/Meme | 31 | 7 |

| Servant Leadership (stewardship as part of) | 29 | 15 |

| Distinctions | 10 | 4 |

| Secular Governance Stewardship | 52 | 14 |

| Religious Governance Stewardship | 25 | 8 |

| Secular Steward Leadership | 30 | 7 |

| Religious Steward Leadership | 44 | 14 |

| What Is Stewardship? | 25 | 13 |

| Sensemaking | 79 | 22 |

| Conflict | 98 | 15 |

| 433 | 136 |

| Year | Author (s) | Title |

|---|---|---|

| 2016 | Wilson | Steward leadership in the non-profit organization |

| 2010 | Rodin | The steward leader: Transforming people, organizations, and communities |

| 2010 | Wilson | Steward leadership: Characteristics of the steward leader in Christian non-profit organizations |

| 2004 | Brinckerhoff | Non-profit stewardship: A better way to lead your mission-based organization |

| 2004 | Brinckerhoff | Non-profit stewardship: A better way to lead your mission-based organization |

| 1989 | Clinton | Leadership emergence theory: A self-study manual for analyzing the development of a Christian leader |

| 1988 | Clinton | Leadership development theory: Comparative studies among high level Christian leaders |

| Year | Author (s) | Title |

|---|---|---|

| 2022 | Katsande et al. | Developing the transforming steward leadership questionnaire scientifically validated measurement instrument |

| 2021 | Katsande | Developing transforming steward leadership scientifically validated measurement instrument |

| 2013 | April et al. | Steward leadership: A maturational perspective |

| 2011 | van Dierendonck | Servant leadership: A review and synthesis |

| 2010 | April et al. | Stewardship as leadership: An empirical investigation |

| 2007 | Niewold | Beyond servant leadership |

| 2005 | Spears | The understanding and practice of servant-leadership |

| 2003 | Blanchard | Servant leader |

| 1997 | Covey | The seven habits of highly effective people: Restoring the character |

| 1996 | Sergiovanni | Moral leadership: Getting to the heart of school improvement |

| 1991 | Spears | Robert K. Greenleaf: Servant-leader |

| 1970 | Greenleaf | The servant as leader in corporate ethics and corporate governance |

| Year | Author (s) | Title |

|---|---|---|

| 2019 | Schillemans et al. | Trust and verification: balancing agency and stewardship theory in the governance of agencies |

| 2017 | Keay | Stewardship theory: Is board accountability necessary? |

| 2012 | Hernandez | Toward an understanding of the psychology of stewardship |

| 2008 | Caldwell et al. | Ethical stewardship—Implications for leadership and trust |

| 2008 | Grundei | Are managers agents or stewards of their principals? Logic, critique, and reconciliation of two conflicting theories of corporate governance |

| 2006 | Caers et al. | Principal-agent relationships on the stewardship-agency axis |

| 2005 | Donaldson | Following the scientific method: How I became a committed functionalist and positivist |

| 2004 | Kulik | Agency theory, reasoning and culture at Enron: In search of a solution |

| 1991 | Donaldson and Davis | Stewardship theory or agency theory: CEO governance and shareholder returns |

| Year | Author (s) | Title |

|---|---|---|

| 2016 | Wilson | Steward leadership in the non-profit organization |

| 2010 | Wilson | Steward leadership: Characteristics of the steward leader in Christian non-profit organizations |

| 2004 | Brinckerhoff | Non-profit stewardship: A better way to lead your mission-based organization |

| 1989 | Clinton | Leadership emergence theory: A self-study manual for analyzing the development of a Christian leader |

| 1988 | Clinton | Leadership development theory: Comparative studies among high level Christian leaders |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tolbert, C.L. The Anointed Steward: A Critical Review of Western Christian and Secular Steward Leadership Literature. Religions 2023, 14, 1187. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14091187

Tolbert CL. The Anointed Steward: A Critical Review of Western Christian and Secular Steward Leadership Literature. Religions. 2023; 14(9):1187. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14091187

Chicago/Turabian StyleTolbert, Carl Lee. 2023. "The Anointed Steward: A Critical Review of Western Christian and Secular Steward Leadership Literature" Religions 14, no. 9: 1187. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14091187

APA StyleTolbert, C. L. (2023). The Anointed Steward: A Critical Review of Western Christian and Secular Steward Leadership Literature. Religions, 14(9), 1187. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14091187