Abstract

Previous studies have assumed that the purpose of Yingyanji was to produce texts that are proselytistic or evangelical. Through the analysis of Guangshiyin Yingyanji, we find that lay people have created Yingyanji for a long time. Its main purpose was not to spread religion, but to record regional memories and family beliefs, which were mainly circulated among friends and relatives. Moreover, the miracle stories contained in Guangshiyin Yingyanji often have different versions within the three systems of Zhiguai, Yingyan, and Gantong. Through an analysis of these different versions, we can better grasp the purpose of rewriting texts under different systems, and the struggle for ideas which they embody.

1. Introduction

Previous research on Buddhist miracle stories or “Buddhist auxiliary texts” (釋氏輔教之書)1 (Lu 1981, p. 54) from the pre-Tang Dynasty can generally be sorted into two approaches: the influence of Buddhism on Six Dynasties literature, and proselytizing Buddhist literature. The first approach emphasizes the influence of Buddhist sutra stories on Zhiguai (志怪) and Six Dynasties literature. This research examines the impact of Buddhist themes and concepts on Zhiguai2 while exploring the relationship between “preaching to people and leading them to conversion” (唱導3) and “Buddhist auxiliary texts.”4 However, this approach tends to treat “Buddhist auxiliary texts” as indirect research subjects and does not analyze their nature and content in-depth.

The second approach originated with Lu Xun and considers “Buddhist auxiliary texts” as an independent research subject.5 The definition and scope of “Buddhist auxiliary texts” were further refined in later research conducted by J. Li (1985, pp. 62–68), emphasizing that the authors of these texts aimed to spread Buddhist teachings and doctrines. Q. Zhang (2018, pp. 39–49) believed that the emergence of these works was related to the Buddhist suppression and anti-Buddhist debates of that time, while Q. Zhang (2018, pp. 39–49) and Cao (1992, pp. 26–36) emphasized their relationship to the disputes between body shape and spirit, as well as the disputes between native and foreign cultures, while acknowledging the political intentions shared with other Zhiguai works. However, these related inferences were mainly based on circumstantial evidence such as the authors’ intentions or historical context, with less discussion on the direct evidence from the works, or differences in the nature of the texts.6 To further clarify the nature of “Buddhist auxiliary texts”, it is necessary to start the discussion with the earliest extant texts of this type: the three editions of Guangshiyin Yingyanji (觀世音應驗記).

Guangshiyin Yingyanji is a collective term for three different editions: 1. The first edition, known as the Guangshiyin Yingyanji (光世音應驗記), was written by Fu Liang 傅亮 (374–426) and is referred to as the Fu edition. 2. The second edition, called the Xu Guangshiyin Yingyanji 續光世音應驗記, was written by Zhang Yan 張演 in the mid-fifth century, and is referred to as the Zhang edition. 3. The third edition, named the Xi Guanshiyin Yingyanji 繫觀世音應驗記, was compiled by Lu Gao 陸杲 (459–532) in 501, and is known as the Lu edition.

Although these three editions were written by different authors, the later two editions mentioned the early edition and claimed to inherit its subject and compile it. Unfortunately, these three editions were lost in China after the Tang Dynasty, but they were rediscovered at the Shōren-in Temple (青蓮院) in Kyoto during the mid-20th century.

Since the rediscovery of the three different editions of “Guangshiyin Yingyanji” in Kyoto, scholars from various countries have conducted research on it. In terms of textual organization, the two annotated editions by Makita Tairyō (1970) and Dong Zhiqiao (2002) are considered the best. The former excels in its historical comparison, while the latter corrects many errors in the original text and provides additional linguistic supplements. In addition, scholars such as Komina (1982, pp. 415–500), X. Zhang (2013, pp. 54–68, 405–17), and C. Sun (1998, pp. 201–28) have conducted research on the circulation and nature of the Guangshiyin Yingyanji,7 or have introduced the belief in Guanyin prevalent during the Six Dynasties period (Makita Tairyo, 1970, pp. 109–56; C. Sun 1998, pp. 201–28; Gu 2015; Xu 2012). However, these studies have mainly focused on organizing the texts, and there is still much work to do regarding the generation of individual stories and their cross-textual transmission. Through an analysis of cross-textual transmission, we can address the following two questions: What is the nature of Guangshiyin Yingyanji and the Buddhist auxiliary texts? Also, are there genres of Buddhist auxiliary texts, and what might be their distinctions?

2. Writing Miracle Stories—Starting with the Three Editions of Guangshiyin Yingyanji

2.1. From “Sharing between Like-Minded Individuals”(傳諸同好) to “Extraordinary Worldly Transmission”(神奇世傳): Why There Are Three Editions of Guangshiyin Yingyanji

In previous studies, the three editions of Guangshiyin Yingyanji were generally treated as a homogeneous entity. Furthermore, researchers tended to analyze these texts from the standpoint of missionary activities and their function as sermon sources. However, these claims only provide indirect or relatively recent evidence, and often lack any direct evidence regarding the actual purpose of the writing found in its prefaces. While Sun Changwu and Komina Ichirō have recognized the importance of these prefaces and pointed out differences between the early Fu and Zhang editions, as well as the later Lu Gao edition, specific distinctions and reasons for these distinctions remain unexplained. To address these questions, it is necessary to analyze the three prefaces first. They are listed as follows:

Fu Liang: Xie Qingxu once wrote a volume of Guangshiyin Yingyanji in one roll, consisting of over ten stories, and gave it to my father. I kept it when I resided in Huiji, I lost it while fleeing from the war. Recently, upon returning to this place, I sought it but could not find it anymore. Seven stories I remember clearly, but I cannot recall the rest. Therefore, I have written down what I remember to please like-minded believers.

傅亮:謝慶緒往撰《光世音應驗》一卷十餘事,送與先君。余昔居會土,遇兵亂失之。頃還此境,尋求其文,遂不復存。其中七條具識,餘不能復記其事。故以所憶者更為 此記,以悅同信之士云.(Dong Zhiqiao, 2002, p. 1)

Zhang Yan: Since my youth, I have received teachings and followed the great Dharma, always revering to the supernatural and expressing my admiration. I have long cherished the idea of compiling these records but have not yet accomplished it. When I saw the collection by Fu, it deeply resonated with me. Thus, I decided to write down what I have heard and add it to the end of his text to share it among like-minded individuals 同好.

張演:演少因門訓,獲奉大法,每欽服靈異,用兼緬慨。竊懷記拾,久而未就。曾見 傅氏所錄,有契乃心。即撰所聞,繼其篇末,傳諸同好云.(Dong Zhiqiao, 2002, p. 28)

Lu Gao: In the past, an esteemed scholar Xie Qingxu recorded over ten miraculous stories about Guangshiyin and presented them to the Magistrate of Ancheng, Fu Yuan, who was also known as Fu Shuyu. The Fu family resided in Kuaiji, but they lost it during the chaos caused by Sun En. Fu Yuan’s son, Fu Liang, who was also known as Fu Jiyou, still remembered seven of those stories and wrote them down. My ancestral uncle, Zhang Yan, who served as an Imperial Secretary, also known as Zhang Jingxuan, separately recorded ten stories to continue Fu’s compilation. These seventeen stories have been passed down to the present. Fortunately, I had the opportunity to receive the Buddha’s teachings and embraced them since my youth. When I read scriptures describing Guangshiyin, I felt a deep sense of reverence. Additionally, I have seen various contemporary writings and stories that are continuously transmitted by the wise, and their accounts of miraculous events are countless. This has made me realize that the sacred spirits are extremely close, and I am filled with gratitude. I believe that every person’s heart has the power to be genuinely moved, and according to the principles of sacred teachings, there must be an inherent force that can be activated. If we can be moved and seek such activation, how can it not have an impact? It is a source of encouragement for virtuous men and virtuous women. Now, in the first year of the Zhongxing reign period of the Southern Qi dynasty(AD 501), I respectfully compiled this volume consisting of sixty-nine stories to connect the works of Fu and Zhang. By arranging them together, readers can see them simultaneously. If there are future wise individuals who continue to hear and learn, they can add to what I have left behind. May this extraordinary worldly transmission widely spread the faith. The details and summaries contained herein are based on what I have heard and know. If you want a detailed examination of it, then we must wait for the insights of other knowledgeable individuals.

陸杲:昔晉高士謝字慶緒記光世音應驗事十有餘條,以與安成太守傅瑗字叔玉。傅家在會稽,經孫恩亂,失之。其子宋尚書令亮字季友猶憶其七條,更追撰為記。杲祖舅太子中舍人張演字景玄又別記十條,以續傅所撰。合十七條,今傳於世。杲幸邀釋迦遺法,幼便信受。見經中說光世音,尤生恭敬。又睹近世書牒及智識永傳,其言威神諸事,蓋不可數。益悟聖靈極近,但自感激。信人人心有能感之誠,聖理謂有必起之力。以能感而求必起,且何緣不如影響也。善男善女人,可不勗哉!今以齊中興元年,敬撰此卷六十九條,以繫傅、張之作。故連之相從,使覽者并見。若來哲續聞,亦即綴我後。神奇世傳,庶廣飧信。此中詳略,皆即所聞知。如其究定,請俟飧識。(Dong Zhiqiao, 2002, pp. 57–58)

“Like-minded believers” (同信) certainly refers to believers who share the same faith, but “like-minded individuals” (同好) cannot simply be regarded as a friend in the general sense. Here, it specifically refers to a circle of friends with similar interests and intellectual attainment. For example, in Yang Liu Fu (楊柳賦), Kong Zang (孔臧) states: “Thus, friends with shared interests gather, sitting together in groups. Discussing the Dao and drinking wine, flowing rivers, and floating cups.” (Fu Yashu, 2011, p. 449) In Zhi Gong Lun (至公論), Cao Yi (曹義) also mentions: “Those who are calm and noble, and share the same interests, are the best of friends.” (Cao Yi comp., Yan Kejun ed., 1958, p. 1163) In certain personal works or accounts, they would only circulate within these social circles. For instance, when Cao Zhi (曹植) mentioned his writings in a letter, he said, “Although I have not been able to hide them on famous mountains, I will transmit them among those with those who have shared interests.” (Chen Shou, 1982, p. 559) Huiyan (慧嚴) once “complained about the verbosity of the Mahaparinirvana Sutra, so he edited and condensed it into several volumes and copied two or three to share with those with shared interests.”8 Therefore, the sources of and intended audience for the Fu and Zhang editions were limited to scholars or regional communities involved in the same faith. The prefaces do not excessively emphasize their own beliefs but rather highlight the origin of the stories and the desire for recognition from specific Buddhist communities. They were not written for missionary purposes, but rather designed as booklets for one’s own personal social and religious exchanges, intended for internal circulation.9

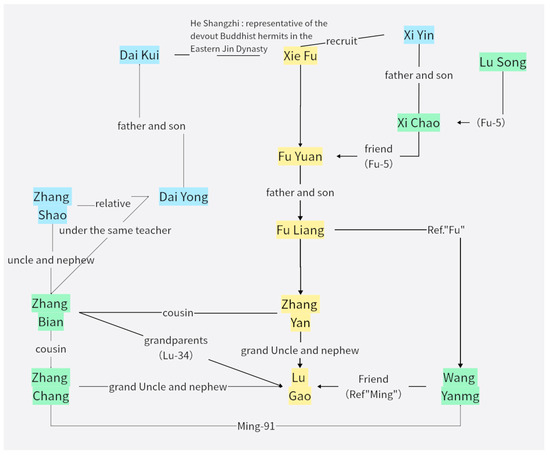

This kind of internal communication can be fully exemplified through the interactions and kinship relations among the three editors(Figure 1). The seven stories in the Fu edition10 had originally been given to Fu Liang’s father, Fu Yuan (傅瑗), by Xie Fu (謝敷). One of the stories was imparted from his father’s friend, Xi Chao (郗超), whose father had recruited Xie Fu. Thus, the Fu family, the Xi family, and the Xie family can be said to have all belonged to the same social circle. Figure 1. Internal communication of three editions of Guangshiyin Yingyanji Yellow: writer or inheritor; Green: story teller; Blue: related parties.

Figure 1. Internal communication of three editions of Guangshiyin Yingyanji Yellow: writer or inheritor; Green: story teller; Blue: related parties.

Although the Zhang edition was inspired by Fu Liang’s writings, it is unclear whether there was any interaction between their families. However, it is evident that the authors of the Zhang and Lu editions shared the same circle of friends and kinship networks. In the preface, Lu Gao explicitly states that Zhang Yan is his maternal uncle, and also records the affairs of Zhang Yan cousins, who are related to Lu Gao’s maternal grandfather, Zhang Chang (張暢). Lu Gao’s writing also references Wang Yan’s (王琰) Mingxiangji (冥祥記), which, in turn, draws from a biography written by Lu Gao’s other maternal uncle, Zhang Bian (張辯).11 This indicates that there is another layer of friendship and kinship between the Zhang, Lu, Dai, and Wang families. Their stories circulated within these circles, becoming shared cultural and intellectual resources among religious communities.

However, there was a change in the case of Lu Gao. In the preface, he emphasizes his family’s religious beliefs which he embraced from a young age, as well as his enthusiasm for promoting miracle stories. This is reflected in the selection of sources and the way that the compilation was made. Lu Gao goes beyond the original sources and extensively references knowledge from sources outside his family, such as “recent writings and the wise”. Thus, in this case, Yingyanji was no longer just a compilation of family memories but instead became a consciously composed collection of missionary stories. The purpose of the writing shifted from an exchange of stories to the act of compiling texts, and its original social and religious roles became reversed. Emphasis was now on affirming personal beliefs. This contrast becomes more apparent when compared to the preface of Wang Yan’s contemporary work, Mingxiangji, in which Wang provides a more detailed description of his personal journey of faith, emphasizing that the stories serve as tools for proving his beliefs and stating, “If the efficacy of the scriptures is revealed, the intent of the evidence is the same; the events are not different, so we follow the same path.” However, the missionary aspect was not prominent in both works until the preface of Mingbaoji (冥報記), during the early Tang Dynasty, when the notion of “persuading people” first emerged.

Fu Liang mentions that he inherited the stories written by Xie Fu. Thus, Yingyanji had already emerged by the mid-Eastern Jin Dynasty. From Fu Liang’s preface, one can see that Xie Fu followed the same approach of “pleasing believers of the same”. Hence, Yingyanji appeared over one hundred years before Lu Gao and Wang Yan, but there is no evidence of similar practices among monks.12 During the same period as Lu and Wang, there was a growing number of secularly authored collections of verified stories, such as Xuanming Yan (宣明驗) and Buxu Mingxiangji (補續冥祥記), as well as the initial biographies of Buddhist monks. Therefore, the nature of verified stories may have been influenced by factors such as the compilation of books in the Qi and Liang dynasties, and the development of Buddhist monastic communities, leading to the emergence of characteristics that facilitated their dissemination among believers.

2.2. Regional Memories: Sources for and Composition of the Guangshiyin Yingyanji

This difference in intention becomes more evident in the context of its sources and the writing process, where there is both continuity and discontinuity between them. Komina Ichirō has analyzed the sources of each story in the Yingyanji in detail, pointing out that Fu Liang’s and Zhang Yan’s sources mainly stem from personal accounts, acquaintances, or the narratives of monks. Lu Gao also inherited these methods to some extent (Komina 1982, pp. 418–500). However, Komina Ichirō does not answer an important question: Why do many of its sources originate with monks who intend to propagate Buddhism, while the Yingyanji itself does not originate from them?

To answer this question, we must first set aside any assumption of “missionary” activities and examine how the Yingyanji was composed. Both Fu Liang and Zhang Yan mention that, in addition to the accounts recorded by predecessors, such as Xie Fu and Fu Liang, they also included stories based on their memories and what they had heard, at times explicitly noting the sources of their information. Lu Gao also frequently mentions different editions of the same story, many of which come from his own family or extended relatives. These records and personal experiences often indicate a story’s principal source and background. In Fu Liang’s text, there are three stories related to the region of Kuaiji (會稽), and Xie Fu himself is from that region, along with Fu Liang and his father residing there; In Zhang Yan’s text, there are six stories connected with the region of Jingzhou (荊州), where his father had served as a military advisor and a magistrate in his early years.13 Lu Gao mostly recorded stories from various places in Yangzhou (楊州), which can be attributed to his father’s position as an official in Yangzhou. Lu Gao also had extensive experience with his own long-term positions there. Therefore, regardless of whether these stories came from monastic or secular sources, their primary attribute is a form of regional knowledge.

Hence, the Yingyanji not only served its purpose of recording strange phenomena as a Zhiguai, but also served as a repository of family and regional knowledge. This is well illustrated in one of the stories found in Zhang Yan’s text [Zhang-7]14:

Sengrong once joined Shi Tanyi in Jiangling to advise a married couple to uphold the precepts. Later, her husband, implicated by the thieves, escaped. The authorities could only capture his wife and send her to prison. On the way to the prison, she encountered Rong and pleaded for his help. Shi Tanyi responded, “You should engrossing focus on reciting the name of Guanyin Bodhisattva, and there is no other method.” The woman immediately began reciting without interruption. During her imprisonment, one night she dreamed of a monk standing between her shoulders and kicking her with his foot, instructing her to leave. Startled, she woke up and found herself freed from the three wooden restraints. Seeing that the gate was still closed and guarded by several gatekeepers, she thought it was impossible to leave, so she put the restraints back on herself. After a while she fell asleep again and dreamt of someone saying, “Why do not you go? The gate is open.” Upon waking up, she passed the guard and walked to the gate, miraculously finding it open. She headed southeast for several miles and was about to reach a village. It was dark and obscure when suddenly she encountered someone, initially feeling alarmed and frightened. At the same time, her husband had been hiding in the grass and wandering during the day, and they asked each other about their well-being. They were indeed the husband and wife. They sought refuge with Shi Tanyi, who hid them in a separate place within the temple. Not long after that, a traveling merchant from their hometown arrived, and Shi Tanyi arranged for them to accompany him and escape successfully.

僧融又嘗與釋曇翼於江陵勸一人夫妻戒,後其人爲劫所引,因遂越走。執婦繫獄。融遇途見之,仍求哀救,對曰:“惟當一心念光世音耳,更無餘術。”婦人便稱念不輟。幽閉經時,後夜夢見沙門立其頸間,以足蹴之令去。婦人驚覺,身貫三木忽自離解。見門猶閉,閽司數重守之。謂無出理,還自穿著。有頃得眠,復夢向人曰:“何以不去?門自開也。”既起,乃越人向門,門開得出。東南行數里,將至民居。時天夜晦冥,忽逢一人,初甚駭懼。時其夫亦依竄草野,晝伏夜行,各相問訊,乃其夫妻也。遂共投翼,翼即藏之寺內別處。無何,其鄉人有遠商者,翼令隨去,竟得免也。(Dong Zhiqiao, 2002, p. 48)

This story was later recorded in both the Fayuan Zhulin and the Taiping Guangji with reference to the Mingxiangji. The overall framework of the story is the same; however, there is some discrepancy in the details, and additional information is provided (see Table 1). The incident took place during the early Yuanjia period, and the layperson mentioned in the story is named Zhang Xing.

Table 1.

The differing versions of the Sengrong story.

Among the three monks mentioned in the story, the records of Tanyi and Sengyi are the most well-documented. Both of them have biographies in the Gaoseng Zhuan. Tanyi was a disciple of Daoan (道安) and was sent to Jiangling to establish the Changsha Monastery and lead the monastic community. He passed away in the nineteenth year of the Taiyuan era (AD 394). Sengyi was a disciple of Huiyuan (慧遠) and traveled north to study in Guanzhong (關中). In the thirteenth year of the Yongxi era (AD 417), he established a monastery in Kuaiji and subsequently lived there in seclusion for thirty years. He passed away in the twenty-seventh year of the Yuanjia era (AD 450). By comparison, very few records on Sengrong exist. Both the Gaoseng Zhuan (高僧傳) and the Mingseng Zhuan (名僧傳) only mention that he was a monk active in the Lushan area of Jiujing. The Gaoseng Zhuan also indicates his ability to subdue demons. According to records, he should have been a monk active during the late Eastern Jin dynasty. In summary, Tanyi was a monk active in Jiangling during the second half of the 4th century; Sengyi was a monk active in Kuaiji during the early Liu-Song dynasty; Sengrong was a monk active in Jiujing during the late Eastern Jin period. Each of them operated in different regions, and Sengyi came later than the other two, indicating no apparent connection between them.

When comparing the Zhang edition with Mingxiangji, the first issue becomes the timeframe of the story. According to Zhang, considering the lower limit mentioned in terms of reign titles and events, this story likely took place toward the end of the Jin dynasty. However, according to Mingxiangji, it occurred during the early years of the Liu-Song dynasty.15 The deceased monk, Tanyi, could not have appeared during the early years of the Liu-Song dynasty; therefore, a contradiction exists between the two editions of the story.

If the content of the Zhang edition is assumed to be entirely true, then the additional timeframe and altered characters found in Mingxiangji would be incorrect. On the other hand, both versions of the Fayuan Zhulin and the Taiping Guangji state that Tanyi conferred the precepts, but the monk who received them had changed from Tanyi to Sengyi. Furthermore, both versions depict the layman, Zhang Xing, as the protagonist and transform Tanyi, the monk from Jiangling, into Sengyi, the monk from Kuaiji. Consequently, a story about a monk named Tanyi in Jiangling during the late Eastern Jin period saving a couple is transformed into a story about a layman in the early Liu-Song dynasty being rescued from distress.

In addition to the possibility of Mingxiangji being modified, one can find potential alterations to another story involving Sengrong in the Zhang edition (Zhang-6):

The monk Shi Sengrong was devoted and compassionate. He advised a family in Jiangling to embrace Buddhism and practice it together. Initially, there were several temples dedicated to gods, which were provided for the support of the monks. Sengrong decided to demolish and remove all the pagan temples associated with the laymen’s family, so he stayed there for seven days for the Buddhist assembly. After Sengrong returns to this temple, the homeowner of that family suddenly sees a ghost holding a red rope, intending to bind him. The mother became greatly worried and immediately invited a Buddhist monk to chant scriptures, causing the ghost to vanish on its own. Sengrong later returned to Mount Lushan and stayed overnight at an inn along the way. It was raining and snowing that night, and he only fell asleep in the middle of the night. Suddenly, he saw numerous ghostly soldiers, among them a particularly large one wearing armor and carrying a weapon. He sat on the big bed that someone was holding up. The great ghost suddenly exclaimed with a stern voice, “How dare you say that ghosts cannot fulfill other people’s wishes!”. They attempted to drag Sengrong to the ground. However, before they could act, Sengrong concentrated and chanted the name of Bodhisattva Guanyin. Before his voice faded, a figure resembling a general, over a zhang (seven feet) tall, emerged from behind the bed where Sengrong was staying. This figure wore yellow-dyed leather trousers and held a golden disc, confronting the ghost. The ghost was immediately frightened and scattered, and the ghost soldiers in armor were suddenly shattered into pieces.

僧人釋僧融,篤志泛愛,勸江陵一家,令合門奉佛。其先有神寺數間,以與之,充給僧用。融便毁撤,大小悉取,因留設福七日。還寺之後,主人忽見一鬼,持赤索,欲縛之。母甚憂懅,乃便請沙門轉經,鬼怪遂自無。融後還廬山,道中獨宿逆旅。時天雨雪,中夜始眠。忽見鬼兵甚眾,其一大者帶甲挾刃,形甚壯偉,有舉胡床者,大鬼對己前據之。乃揚聲厲色曰:君何謂鬼神無靈耶?便使曳融下地。左右未及加手,融意大不憙,稱念光世音,聲未及絕,即見所住床後,有一狀若將帥者,可長丈餘,著黃染皮袴褶,手提金枚以擬鬼,鬼便驚懼散走,甲冑之卒然粉碎。(Dong Zhiqiao, 2002, p. 44)

This story can be divided into two parts: Sengrong’s solicitation in Jiangling and his encounter with ghosts in Mount Lu. Sengrong had already left after preaching in Jiangling, and it was other monks who managed to exorcise the ghosts that disturb the households of believers. This appears to be unrelated to Sengrong’s later encounter with ghosts. (Zhang-6) clearly describes that both Tanyi and Sengrong were involved in the proselyting in Jiangling, and that the woman sought help from Sengrong but ended up taking refuge in the temple where Tanyi resided. (Zhang-7) depicts Sengrong’s involvement in the solicitation in Jiangling, yet it was the other monks who resolved the ghost encounter for the host, while Sengrong encountered ghosts during his solitary training in Mount Lu. Both stories begin with Sengrong’s involvement in proselyting, but only in a certain portion of the stories. Therefore, there is a possibility of later recompilation.

When comparing the records of the three monks in the Buddhist biographies, Monk Yi does not have any miraculous incidents associated with him. The miraculous incidents attributed to Monk Tanyi are all related to relics and Buddha statues, emphasizing his sincere faith rather than his inherent supernatural abilities. Only Sengrong is described as having the ability to subdue ghosts and spirits through his austere practice. Therefore, we can suggest that Sengrong is likely to have been added as a character with supernatural abilities to the story originally centered around Tanyi, who had been the main protagonist in Jiangling. Sengrong’s encounter with ghosts was an additional story placed in the background of Jiangling. Both stories involving Sengrong were combined and included in the Xu Gaoseng Zhuan (續高僧傳), where Sengrong was reimagined as a monk with supernatural abilities during the early Liang dynasty. Although both stories are set in Jiangling, the presence of the other monks has been removed, and the act of seeking refuge alone was altered to seeking refuge together with a merchant, making Sengrong the sole protagonist of the story. The Xu Gaoseng Zhuan explicitly states that he came from the Donglin Temple in Jiujian, which indicates a possible reference to another version of the story circulating in Jiujian.16

Apart from the story itself, the construction of regional knowledge can be observed through its narrators. This characteristic is particularly evident when comparing stories told by northern immigrants. The stories of those who migrated from the north to the south were not recorded by the author, but rather passed down by familiar monks or laymen.17 Therefore, they were based upon certain points during the war, had relatively simple storylines, and did not record the subsequent experiences of any individuals involved, or other versions of the story. The other stories, however, were narrated by the individuals involved or their relatives and friends, because their protagonists had lived in the Southern Dynasties. Some stories even have multiple narrators, resulting in more complex narratives and multiple versions.

This characteristic of multiple narratives can be illustrated through the story of the “Pengcheng widow” (Lu-63).

The Pengcheng widow came from a family devoted to Buddhism, and she was diligent in her practice. She had lost all her relatives, leaving only one son who listened to her teachings. The son was extremely filial, and the bond between the mother and son was filled with love and compassion. In the seventh year of the Yuanjia era (AD 430), her son accompanied Dao Yanzhi on a military campaign against the nomads. The elderly widow bid farewell with tears, repeatedly advising and admonishing her son to observe the precepts and have faith in Guanyin Bodhisattva. The elderly widow was extremely poor, she had nothing to offer the Buddhist assembly, so she often sat in front of the Guanyin statue, lighting a lamp to pray for blessings. Her son was captured by the Wei Kingdom army while carrying out his mission to capture prisoners. Fearing that he might escape, the Wei Kingdom army escorted him to the northernmost border. When the army returned, her son did not come back. However, she kept lighting a lamp in front of the statue, praying for Guanyin Bodhisattva’s help. During the same period, her son also prayed day and night in the north. One night, he suddenly saw a light shining brightly at a distance of a hundred paces. He tried to approach it, but the light disappeared. Then, he saw it again in front of him, as if beckoning him. He thought it was a divine phenomenon, so he followed the light. After every sunset, the light would be illuminated again. Therefore, he stopped in a village to beg for food during the day and continued his journey at night guided by the light. He traversed mountains and valleys as if they were level ground, traveling thousands of miles until he returned to his hometown. Upon his arrival, he saw his mother still kneeling in front of the lamp, her face illuminated by its light. He realized that the light he had seen before was the lamp before the statue. The news spread far and wide, and everyone rejoiced in their miraculous experience. The mother and son redoubled their efforts in their spiritual practice. After his mother’s passing, the son decided to become a monk. Later, he sought a master and disappeared; no one knew where he was.

Another version tells of the widow. After she lost her son, she constantly lit a lamp in front of the Guanyin statue and recited the Guanyin Sutra day and night, hoping to have a vision of Guanyin. However, she is also afraid that her son may have already perished. She also performed seasonal ancestral rituals. The nomads treated her son as a slave and assigned him to herd the animals. Every time during the ancestral ritual, her son would dream of returning to partake in the offerings. After the widow’s sincere devotion for over a year. One day, while her son was in the mountains, he suddenly saw a pillar-like light, approximately ten steps away, that quickly moved beyond his reach. He pursued it persistently and finally returned home after ten days. Upon his return home, he witnessed the light leading directly to the Guanyin statue, while his mother was prostrated in front of it.

There are two versions of this story. I copied it from the Xuanyanji by Gao Chao. I showed them to the provincial official He Yi of Nanyuzhou. He Yi, known as a diligent and honest scholar, said, “I have heard this story since my childhood. The widow was my maternal grandmother. I have often heard my family reiterate her tale, saying that she tore a lot for her lost son. Her tears fell on the lamp, causing it to burst. Her cheeks were scalded and burned by the lamp oil.

彭城嫗者,家世事佛,嫗唯精進。親屬並亡,唯有一子,素能教訓。兒甚有孝敬,母子慈愛,大至無倫。元嘉七年,兒隨到彥之伐虜。嫗銜弟追送,唯屬弁歸依觀世音。家本極貧,無以設福,母但常在觀世音像前然燈乞願。兒於軍中出取獲,為虜所得。慮其叛亡,遂遠送北堺。及到軍復還,而嫗子不反,唯歸心燈像,猶欲一望感淚。兒在北亦恆長在念,日夜積心。後夜,忽見一燈,顯其百步。試往觀之,至徑失去。因即更見在前,已復如向,疑是神異,為自走逐。日沒,還復見燈,遂晝停村乞食,夜乘燈去。經歷山險,怔若行平。輾轉數千里,遂還鄕。初至,正見母在像前,伏燈火下。因悟前所見燈即是像前燈也。遠近聞之,無不助為憙。其母子遭荷神力,倍精進。兒終卒供養,乃出家學道。後遂尋師遠遁,不知所終。

一說嫗既失子,恆燃燈觀世音像前,晝夜誦觀世音經,希感聖神,望一相見,又恐或已亡沒,兼四時祠之。虜以嫗子為奴,放牧草澤。母祠之日,輒夢還饗。母積誠一年,晝夜至到。後兒在山中,忽見一光如柱形,長一丈,去已十步,而疾走不及。逐之不 已,得十日至家。至家,見光直歸像前,母正稽顙在地。

有二本如此云。杲抄《宣驗記》,得此事,以示南豫州別駕何意。意,篤學厚士也。語杲:此嫗,其外氏。固從已小時數聞家中叙其事,云嫗失兒,恆沾淚,淚下燈爆, 雨頰遂爛,其苦至如此。(Dong Zhiqiao, 2002, pp. 194–95)

In addition to He Yi’s version, there are three versions of this story. The general idea of the story revolves around a mother and son from Pengcheng. The son was captured by the enemy during the Northern Expedition in the seventh year of the Yuanjia era (AD 430), but later returned. Throughout his journey south, he was guided by a lamp, and upon reaching home, he discovered that his mother had been praying with a lamp in front of the statue all along.

Interestingly, Xuanyanji (宣驗記) also records another strikingly similar story, which is cited in Bianzheng Lun (辯正論), Shishi Liutie (釋氏六帖), and Taiping Guangji. The three citations are essentially the same. This is the version cited from Bianzheng Lun:

“The story of Che’s mother lighting the lamp to pray, and her son unexpectedly coming back”: The story of Che’s mother is about her son suffering during the “Qingni Incident” caused by the King Luling of Song, which was captured by Fofo caitiffs and imprisoned in the enemy barracks. His mother has always been a Buddhist, so she immediately started to light seven lamps in front of the Buddha statue. She wept earnestly day and night, praying for her son’s liberation. This went on for years. Suddenly, her son managed to escape and return, traveling alone on foot for seven days. He lost direction due to the cloudy weather, and he saw seven segments of firelight in the distance and ran toward them. It appeared to be a village, so he intended to seek refuge, but he was unable to reach it continuously. In addition, after seven nights, he unknowingly arrived home. He saw his mother still praying in front of the Buddha and lit seven lamps. At that moment, they both realized the power of the Buddha. From then on, they devoted themselves to practicing acts of charity and endurance.

車母燃燈不期兒至。車母者,遭宋廬陵王青泥之難為佛佛虜所得,在賊營中。其母先來奉佛,即燃七燈於佛前。晝夜精心哭觀世音,願子得脫。如是經年,其子忽得叛還。七日七夜行獨自南走,值天陰不知西東。遙見有七段火光,望火而走。似村欲投,終不可至。如是七夕,不覺到家。見其母猶在佛前伏地,又見七燈,因乃發悟。母子共 談知是佛力,自後懇到專行檀忍。18

Here, the timeframe of the story changes to the Qingni Incident in the 14th year of the Yihe era (AD 418), referring to Liu Yizhen’s (劉義真) retreat from Guanzhong (關中). Although there are differences between the two accounts in terms of the names of the individuals involved, the objects of offering, and the details about lighting the lamps,19 the theme and structure of the story are indeed similar, in which a mother offers lamps to the Buddha and prays for her son’s return. There are two possibilities here: one is that Guangshiyin Yingyanji recorded two highly similar stories; the other is that they draw on one another. Regardless of the outcome, it can be inferred that this particular story was widely popular when Guangshiyin Yingyanji was written, leading to the emergence of several versions. Whether it was rewritten, or just a selection of a particular version, Lu abandoned the story of a son being saved through the mother’s offering to the Buddha, and instead chose (or composed) a version that emphasized the family’s devotion to the Guanyin, resulting in his salvation.

If we focus solely on determining which version is true, or if there is a relationship between copying and rewriting, we may overlook the unique qualities of Yingyanji. Only by combining local knowledge with the establishment of familial and regional characteristics can one discover the intertextuality among different stories, as well as the complex interactive relationships between them.20 When Liu Yizhen compiled Xuanyanji, only twenty years had passed since the Qingni Incident. In contrast, Lu Gao, who recorded the Lu edition, was separated from Dao Yanzhi’s Northern Expedition by seventy years, and from the Qingni Incident by nearly a hundred. It would have been difficult for him to determine the exact timing of these events. Additionally, the story would have been spread over different regions and through different battles. In addition to the possibility that the existing version of Xuanyanji differs from what Lu Gao saw, it is also possible that Lu Gao supplemented the story based on other versions he had heard, or other augmented versions he had copied. Lu Gao said that “the story was widely known, and everyone enthusiastically supported it”. We can imagine that a story of successful escape and return home must have been rare and deeply impactful. Therefore, the focus is not on determining which version is true, as Xuanyanji provides only the earliest existing version. The significance lies in how the story of the “Pengcheng widow” carries the collective memory of repeated failure as well as the loss of family and loved ones during the Northern Expeditions in the Jin-Song transition period. In this way, this original narrative has had quite a lasting impact.21

Its multiple narratives make it difficult to ascertain the truth of the story, but the story itself carries specific collective memories, allowing us to glimpse into how the story was constructed, as seen in (Lu-32):

Zhu Lingshi, a native of Pei, was a meritorious minister of Emperor Gaozu of the Liu-Song dynasty. In the early period of the Jin Dynasty’s Yixi era, he served as the magistrate of Wuxing Wukang. At that time, there were many wicked people in the county, and Lingshi executed and killed a large number of them, exceeding the proper limit, which could have led to his death sentence. The court ordered Zhang Chongzhi to investigate the matter, and Lingshi was arrested and imprisoned, awaiting execution. The family filed a lawsuit at the time, but a final verdict has not yet been reached. Corrected: At that time, there was a monk named Shi Huinan who was an old acquaintance of Lingshi. Someone informed Shi Huinan about the news, and he went to visit Lingshi in prison. He taught Lingshi to recite the name of Guanyin and also left a statue of Guanyin for worship. Lingshi was already a believer in Buddhism, and now that he was facing adversity, he became even more devoted to his worship, continually reciting the name of Guanyin. After seven days, his shackles were miraculously unlocked. The prison guards were amazed, so they reported it to Zhang Chongzhi. Zhang suspected that Lingshi became thin during the period. They try to put the shackles back on, but they did not fit. They still believed it was just a coincidence, so they tightened the shackles again. However, after a few days, the shackles loosened again. This situation happened three times, so Zhang Chongzhi reported this miraculous incident. While detailed discussions on the matter had already refuted the accusations against Lingshi, Zhang Chongzhi’s report also arrived, so they immediately released Lingshi and resumed his post. Both Lingshi and his brothers achieved great success.

朱齡石,沛人也,為宋高祖功臣。晉義熙初,作吳興武康令,時縣有兇猾,齡石誅殺過多,當死。朝廷使張崇之檢校其事,被收録,繫在獄中,當死。家人訟訴,是非未辯。時有道人釋惠難與石有舊,乃往告,入獄看之。因教其念觀世音,又留一人像與供養。齡石本事佛,並窮厄意專,遂一心係念。得七日,即鎖械自脫。獄吏驚怪,以故白崇。崇疑是愁苦形瘦,故鎖械得脫。試使還著,永不復入。猶謂偶爾,更釘著之。又經少日,已得如前。凡三過,崇即啓以為異。爾時都下前論詳其事,已破申。會崇至,還復縣,齡石亦終能至到,兄弟有功名。(Dong Zhiqiao, 2002, p. 124)

According to the “Biography of Zhu Lingshi” in the Songshu (宋書), Zhu Lingshi’s indiscriminate killings occurred after the Jin Dynasty invaded Shu in the tenth year of the Yixi reign (AD 414). It states, “Initially, Lingshi pacified the rebellion in the Shu region, and the number of people he executed was limited to the rebel leader’s clan. However, Hou Chande rebelled and many people were implicated and executed”. This shows that the incident had a significant impact at that time. However, this incident does not correspond to the account mentioned here. Nevertheless, years before the invasion of Shu, Zhu Lingshi was appointed as the magistrate of Wukang and was indeed involved in the execution of local ruffians in Wuxing. During his tenure, he lured and killed dozens of bandits, bringing peace to the county. However, there is no record of him being held accountable, and he was soon promoted.22 Therefore, it can be inferred that the stories in Lu should be combined with these two incidents. Additionally, similar narratives can be found in other anecdotal stories about Zhu Lingshi.23

Accordingly, it can likely be concluded that the stories in Yingyanji may not have been recorded accurately, but instead draw upon certain real events and bear certain collective memories. Such ambiguity is not uncommon. When Baochang (寶唱) collected stories about Shanmiaoni’s (善妙尼) self-immolation, which happened several decades prior, there were already three different versions circulating during the 17th Yuanjia (AD 440), Xiaojian (AD 454–456), and Daming (AD 457–464) periods.24 Therefore, the fluid nature of legends should not be underestimated. Correspondingly, these collective memories serve as the prototypes of stories which are constantly rewritten and transmitted, allowing them to continue to be passed down.

In summary, the reason why the Yingyanji was not compiled by monks is precisely that it was a compilation of stories put together by an author who had either heard or experienced them, and then shared them with their regional community. Therefore, Xie Fu, who resided in Mount Kuaiji, passed on the stories to the Fu family, who in turn added on the local stories they had heard in Kuaiji. Zhang Yan, a relative of the Fu family, obtained the version from Fu Liang and added stories that were circulated in Jingzhou. Lu Gao, building upon the work of his predecessors, incorporated many local stories from Yangzhou and had interactions with Wang Yan and He Yi.25 They continually supplemented the stories told by their relatives and friends based on the foundation of previous works, resulting in a collection of stories circulated within a specific group. It is precisely due to the nature of this internal circulation that stories often do not require an accurate time. This is particularly evident in Zhang Yan’s edition, where out of ten stories, only three indicate some time of occurrence.26 Among those seven without dates or time markers, four had dates added in later records and some details were added, too, entering into the realm of biographical records.27

This tendency gradually disappears in Lu Gao’s version, and other works with a heavier emphasis on proselytizing, such as the Mingxiangji. They require explicit time markers and merits to enhance credibility and incorporate various accounts and arguments to strengthen their persuasiveness.28 At the same time, their sources of material continued to expand. Lu Gao collected stories from various regions and various textual sources to demonstrate the universality of Guangshiyin worship. On the other hand, the Mingxiangji aimed to collect all miracle stories since Emperor Ming’s dream of Buddha, focusing on the spread of Buddhism to the East and the development of Han Chinese Buddhism.29 Both would gradually move away from the local, inward-facing approach to compilation, instead shifting their focus from the family to the broader society, and expanded the scope of their object of worship from specific religious figures to the entire Buddhist tradition.

Miracle stories are not independent products of a specific time and place, but are constructed through the layering of first-hand witnesses, narrators, and recorders. These stories also generate different versions in different regions. Even after being recorded, each version still contains differences based on factors such as region and perspective in different types of texts. Therefore, an analysis on the dissemination of miracle stories cannot be limited to the Yingyanji itself; it is necessary to examine the overall process of their dissemination. Based on different writing perspectives and factors, these versions can be classified into different textual systems. The next chapter will focus on the study of the rewriting and generation of supernatural stories within different textual systems, examining the stories within the context of their overall transmission process. By exploring the continuous compilation and rewriting of supernatural stories, as well as the writing characteristics of different textual systems, we can better understand the fluidity of supernatural stories.

3. Zhiguai, Yingyan (應驗), and Gantong (感通): The Compilation of Miracle Stories

Since the nature of Yingyanji differs from later “Buddhist auxiliary texts”, discrepancies within the same story among different dissemination systems become significant. We may classify them based on the Zhiguai system, which has no Buddhist leanings; the Yingyan30 system, which was written by Buddhist laypeople; and the Gantong31 system written by Buddhist monks. Unlike the later-developed chuanqi, Yingyan, and Gantong in Zhiguai, they still retain descriptive traits and are mostly of short length. However, they exhibit different emphases when narrating the stories, leading to their selection and the rewriting of the stories. As a result, the same story may take on various appearances and versions in the records of the three distinct narrative systems. Below, we will compare Yingyan with Zhiguai first.

3.1. Zhiguai and Yingyan: Analysis of Stories with Parallel Non-Religious Literature

Of the six stories with parallel texts in nonreligious literature, five of them have pre-Tang texts. Here, detailed discussions will be conducted on four of them.32

- Fu-7: Monk Zhu Fayi

- Direct source: Fayi told Fu Liang’s father when they traveled together

- Parallel texts: Mingseng Zhuan, Gaoseng Zhuan, Fayuan Zhulin quoted Mingxiangji, Fayuan Zhulin quoted Shuyiji (述異記), Taiping Guangji quoted Shuyiji, Bei Shan Lu (北山録)

This story does not originate from Xie Fu, but from Fu Liang, who inherited it from his father. Therefore, it should be considered the original version of the story. The story’s essence is that the monk Zhu Fuyi became ill and turned to Guanyin for salvation. Later, he dreamed of a monk cleansing his intestines, and upon waking up, he miraculously recovered. The story later appeared in Shuyiji,33 Mingxiangji, and Mingseng Zhuan during the Qi and Liang dynasties. It continued to be disseminated in the religious literature, such as the Gaoseng Zhuan and the Fayuan Zhulin.

Makita Tairyō argues that two similar stories found in the Fayuan Zhulin come from Mingxiangji and the Fu edition. He considers the attribution of the story to Shuyiji a mistake, which was subsequently inherited by the Taiping Guangji [Makita Tairyō, 1970, p. 82]. However, this is a simple deduction that simplifies the transmission of the story. Since the Fu edition was heard by the author’s father and is likely the original record of the story, it serves as a common source for both Shuyiji and Mingxiangji, with the two being over one hundred years apart in their respective narrations. Therefore, it is rather reasonable for Fayuan Zhulin to have adopted the later Shuyiji and this hypothesis can be supported by comparing the two versions of Mingxiangji and Shuyiji.

The two versions recorded in Fayuan Zhulin are as follows. Fayuan Zhulin quoted Mingxiangji:

During the Jin Dynasty, there was a monk named Zhu Fuyi in Shining Mountain. He was very knowledgeable and particularly adept at Lotus Sutra. He had more than a hundred disciples. In the second year of the Xian’an era (AD 372), he suddenly fell ill and felt strong discomfort in his heart. He always kept praying to Guanyin. One night, he dreamed of a person opening his abdomen and washing his intestines. When he woke up, his illness miraculously disappeared. Fu Liang often said that his father and Zhu Fuyi had a close relationship; every time he mentioned the miracles of Guanyin, he would show great respect.

晉始寧山有竺法義。晉興寧中沙門,游刃眾典尤善法華,受業弟子常有百餘。至咸安二年,忽感心氣疾病,常存念觀世音。乃夢見一人破腹洗腸,寤便病愈。傅亮每云:吾先君與義公游處無間,說觀世音神異,莫不大小肅然。34

The narrative of Mingxiangji35 and the Fu edition is generally the same, but the former adds the lively detail of “during the Xingning period.” This account aligns with the record in Shamen Tanzongsiji (沙門曇宗寺記) from Gaoseng Zhuan,36 mentioning that Zhu Fuyi “first resided in Baoshan during the Xingning period.” Fayuan Zhulin cites Shuyiji as follows:

During the Jin dynasty, the Śramana Zhu Fuyi resided in the mountains and was a diligent scholar. He lived in Baoshan in Xingning. Later, he fell ill for a long time, and despite extensive medical treatment, his condition did not improve. He became bedridden and gave up treatment, relying solely on devotion to Guanyin. This continued for several days until one day, while he was sleeping during the day, he dreamt of a divine being who came to attend to his illness. The divine underwent a surgical procedure, removing and cleansing his intestines and stomach, discovering numerous impurities and cleansing them before putting them back inside. The divine being said, “Your illness has been eliminated.” Upon waking up, all his ailments disappeared, and he returned to his normal state of health. According to the scripture (Lotus Sutra), Guanyin may manifest as a monk or a Brahmin, which Zhu Fuyi interpreted as the divine being in his dream. Zhu Fuyi passed away in the seventh year of the Taiyuan era (372). Correct: Of the six incidents involving Zhu Zhangshu to Zhu Faye, all were written by Fu Liang, the Prime Minister of the Liu-Song dynasty. Fu Liang stated that his father had interacted with Zhu Fuyi. Whenever Zhu Fuyi recounted these events, his father would feel more respect.

晉沙門竺法義,山居好學,住在始寧保山。後得病積時。攻治備至而了不損。日就綿篤,遂不復自治,唯歸誠觀世音。如此數日,晝眠夢見一道人來候其病。因為治之,刳出腸胃,湔洗腑藏。見有結聚不淨物甚多,洗濯畢還內之,語義曰:「汝病已除。」眠覺眾患豁然,尋得復常。案其經云,或現沙門梵志之像,意者義公所夢其是乎。義以太元七年亡。自竺長舒至義六事,並宋尚書令傅亮所撰。亮自云:其先君與義游處。義每說其事,輒懍然增肅焉。37

From the concluding sections of both texts, it can be seen that Shuyiji and Mingxiangji share a common source. Therefore, it is not possible to affirm Mingxiangji while negating Shuyiji. It cannot be ruled out that one version was copied by Fayuan Zhulin from Shuyiji. For example, the mention of the year of death in Shuyiji is not found in other texts.38 Correspondingly, Shamen Tanzongsiji does not mix the accounts of Zhu Fuyi’s studies and the construction of the Jianxin Pavilion Temple into this system. Moreover, from its table of contents, it can be inferred that these two versions have different emphases. Based on this, we can outline the context of the story’s evolution:

1. Fu edition --> Mingxiangji + Shamen Tanzongsiji --> Mingseng Zhuan, Gaoseng Zhuan (+ unknown text), Fayuan Zhulin

2. Fu edition --> Shuyiji --> Fayuan Zhulin, Taiping Guangji

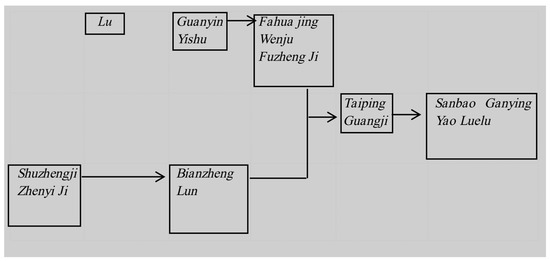

- Lu-15: Gao Xun

- Parallel texts: Guanyin Yishu (觀音義疏) quoting Yingyanji, Bianzheng Lun quoting Xuanyanji and Xu Soushenji (續搜神記), Fahua jing Wenju Fuzheng Ji (法華經文句輔正記), Taiping Guangji quoting Xuanyanji, Sanbao Ganying Yao Luelu (三寶感應要略錄) quoting Xuanyanji

At the end of the text, Lu Gao quotes Shuzhengji and Zhenyiji, but it is only for reference and not a direct copy. The main body of the story still comes from Yingyanji. Both Xuanyanji and Lu Gao deliberately omit the variant of selling one’s wife, indicating their conscious removal of this detail. Interestingly, in later works such as Guanyin Yishu and Fahua jing Wenju Fuzheng Ji, there is no avoidance of such detail.

Furthermore, in the version of Xuanyanji quoted in Bianzheng Lun, the object of the protagonist’s prayers is the “Buddha deity”, and the divine power of the Buddha deity is emphasized repeatedly, but Guanyin did not appear. However, in the later versions of Xuanyanji quoted in Taiping Guangji and Sanbao Ganying Yao Luelu, both the Buddha deity and Guanyin interchangeably appear in the story, forming the concepts of “reciting Guanyin together” and “devoting oneself wholeheartedly to Guanyin”, but also seeking mercy and assistance from Buddha. These reflect the influence of Yingyanji on later versions.

- Lu-34: Zhang Huoji Shijun

- Direct source: Zhang Chang, the maternal grandfather of Lu Gao

- Parallel texts: Guanyin Yishu quoting Yingyanji, Taiping Guangji quoting Yang Jie’s Tansou (談藪)

Since this story originates from the personal record of Lu Gao’s maternal grandfather, Zhang Chang, the events in the story are particularly detailed, including his official career experience. The story can be divided into two parts: Qiao Wang intends to kill Zhang Chang due to his admonishments, but whenever he has ill intentions, he dreams of Guanyin at night and refrains from inflicting harm. Zhang Chang is later imprisoned for his involvement in Qiao Wang’s affairs, so he recites scriptures a thousand times, causing his shackles to break, and is eventually released.

Compared with Lu Gao’s account, Tansou removes many details such as the religious background and Zhang Chang’s admonishment of Qiao Wang, retaining only the records of Guanyin’s manifestation twice. Furthermore, the phrase “whenever he has ill intentions and dreams of Guanyin at night” is changed to “when he intends to harm and dreams of Guanyin at night”, simplifying the narrative of consistent manifestations to a dream of a divine being.

- Lu-35: Zhang Da

- Direct source: Zhang Shi Bie Zhuan (張氏別傳)

- Parallel texts: Bianzheng Lun quoting Zhang Shi Bie Zhuan, Taiping Guangji quoting Zhang Shi Zhuan (張氏傳), Shishi Liutie

This story consists of only about thirty words, describing Zhang Da’s imprisonment and subsequent salvation through reciting scriptures, followed by his becoming a monk. However, Bianzheng Lun and Taiping Guangji only mention that Zhang Da observed a lifelong vegetarian diet and abstained from worldly desires, but do not mention him becoming a monk. Furthermore, both sources describe him devoting himself wholeheartedly to meditation,40 rather than reciting scriptures.

Looking at the differences observed in the versions above, several characteristics can be summarized. First, any overlap between Yingyanji and its nonreligious counterpart gradually decreases. There are three instances in Fu Liang’s work, one in Zhang’s, and two in Lu Gao’s. Considering the proportional factor, the later Yingyanji and nonreligious literature have less overlap, reflecting a differentiation between Zhiguai and Yingyan narratives. Second, there is mutual rewriting among the Zhiguai and Yingyan narrative systems. The Yingyan system, influenced by popular religious evangelism, removes descriptions that go against societal ethics, such as “selling wives and children”, while such descriptions are preserved in the Zhiguai and monk-oriented Gantong stories.41

Last, the Zhiguai narratives are solely concerned with extraordinary phenomena and are not interested in the details of Buddhist beliefs. Therefore, they tend to reduce vivid and intricate stories of spiritual experience into dreams of the divine beings. In response, the Yingyan narratives also make modifications to conform them with their own religious beliefs. For example, Chan meditation is changed to scripture recitation, and Buddhist deities are replaced with Guanyin Bodhisattva. Additionally, Guanghiyin Yingyanji places more emphasis on the power of Guanyin Bodhisattva compared with other Yingyan narratives which are closer to supernatural tales. Apart from changing the object of supplication, stories that cannot demonstrate the power of the spiritual are also removed. Lu Gao selectively removed certain stories several times because “this matter does not reach the level”. Traces of these stories can still be found in three other texts:

In the Bianzheng Lun, the Xuanyanji is cited, stating that Yu Wen braved the raging waves without fear. When Yu Wen carried salt in Nanhai and encountered strong winds, he silently recited Guanyin’s name, and the wind subsided and the waves calmed down. Finally, he got safe.(This account is also mentioned in Shishi Liutie.)

《辯正論》引《宣驗記》:俞文汎海不畏洪波。俞文載鹽於南海值風。默念觀音,風停浪靜。於是獲安。(《義楚六帖》亦載)42

In the Fayuan Zhulin, the Mingxiangji is cited, recounting the story of Gu Mai, a resident of Wu County. He was a devout practitioner of Buddhism and served as a military official. In the nineteenth year of the Yuanjia era (AD 443), he returned to Guangling from the capital. When the boat set sail from Shi Tou Cheng, it encountered a headwind, which was an unusual occurrence of strong winds. Despite the ongoing strong winds, the boatmen were eager to move forward. As they reached the middle of the river, the wind and waves grew even stronger, making the situation extremely helpless. He recited the Guanyin Sutra repeatedly, the wind subsided, and the waves diminished. Moreover, a mysterious fragrance permeated the area. Gu Mai was filled with joy and continued to recite the sutra, and thus he reached safety.

《法苑珠林》引《冥祥記》:宋顧邁,吳郡人也,奉法甚謹。為衛府行參軍。元嘉十九年。亦自都還廣陵。發石頭城便逆湖朔,風至橫決。風勢未弭,而舟人務進。既至中江波浪方壯。邁單船孤征憂危無計。誦觀世音經得十許遍。風勢漸歇浪亦稍小。既而中流屢聞奇香芬馥不歇。邁心獨嘉。故歸誦不輟。遂以安濟。43

In another account from the Fayuan Zhulin, the Mingxiangji is cited, narrating the story of Bian Yuezhi 卞悅之, a layman from Jiyin. He resided in Chaogou and was in his fifties without any children. To seek an heir, his wife took a concubine, but she still could not conceive. Desperate for an offspring, Bian Yuezhi recited the Guanyin Sutra a thousand times. Miraculously, after completing the recitation, his concubine became pregnant and gave birth to a son. This incident was recorded in the eighteenth year of the Yuanjia era (AD 442), and the child was already five years old.(This account is also mentioned in Taiping Guangji, but it states it was recorded in the fourteenth year (AD 438) of the Yuanjia era.)

《法苑珠林》引《冥祥記》:宋居士卞悅之。濟陰人也。作朝請居在潮溝。行年五十未有子息。婦為取妾。復積載不孕。將祈求繼嗣。千遍轉觀世音經。其數垂竟妾便有娠。遂生一男。元嘉十八年已五歲(《太平廣記》亦載,但作元嘉十四年)44

Indeed, these stories are rather simple and focused on factual records. Their religious elements are relatively mild and do not emphasize the miraculous nature of the outcomes. Therefore, Lu Gao deemed them to be unfit, as they were not extraordinary, and they were not included.45 Though Yingyanji is often portrayed as being disregarded, it demonstrates Lu Gao’s deliberate selection and modification of stories. This indicates a reciprocal relationship between the Zhiguai and Yingyan genres of mutual rewriting.

3.2. The Systems of Xuanyanji and Mingxiangji

Xuanyanji is often regarded as one of the earliest “Buddhist auxiliary texts”, and this perception is mainly derived from Liu Yiqing’s accounts of his conversion to Buddhism during his later years. However, recent studies have pointed out that Xuanyanji, along with Liu Yiqing’s other works such as Shishuo Xinyu (世說新語) and Youminglu (幽明録), were mostly compiled by his subordinates and assistants (Fan 1995; Ning 2000; S. Liu 2008; Zhao 2020). Furthermore, both Youminglu and Xuanyanji were completed in his later years. Therefore, the extent of Liu Yiqing’s personal religious beliefs and the degree to which Buddhism influenced the nature of Xuanyanji remain mysterious.

According to Sano Seiko’s research, Xuanyanji does not focus on matters related to the underworld like Youminglu does. Instead, it includes more content related to Buddhist concepts, such as cause and effect, and karmic retribution. Yet, its approach differs from Guangshiyin Yingyanji, which focuses solely on the topic of Guanyin responding to people’s prayers, as well as Mingxiangji, which includes stories of the underworld as well as the supernatural (Sano 2020, pp. 228–38).

As discussed earlier, the stories found in Xuanyanji and the MingxiangjI (See: Robert Ford Campany 2012, pp. 7–17; G. Wang 1999, pp. 2–4) can often emphasize different aspects within the context of their transmission. Among the notable differences, two main variations can be identified:

- Lu-3: The Official of Wuxing (吳興) Commandery

- Direct Source: Possibly Wang Shaozhi (王韶之)

- Parallel Texts: Guanyin Yishu citing Guangshiyin Yingyanji, Bianzhenglun citing Xuanyanji, Taiping Guangji citing Xuanyanji, Fayuan Zhulin citing Mingxiangji, and Shishi Liutie citing Youminglu.

The general outline of this story is that, during the middle of the Yuanjia era (AD 424–AD 453), the magistrate of Wuxing, Wang Shaozhi, witnessed a large fire engulfing the homes of the people. However, he noticed that the grass hut where a local official lived remained unscathed by the fire. The official had no previous association with Buddhism but had frequently heard Wang Shaozhi talk about Guanshiyin Bodhisattva. During the fire, the official sincerely chanted the name Guanshiyin Bodhisattva and was thus saved. Since this story is narrated by Wang Shaozhi and emphasizes his role in urging the official to have faith, the origin of this story can likely be traced back to Wang Shaozhi.

Various parallel versions of this story highlight the miraculous preservation of the house (see Table 2).

Table 2.

The differing versions of the Wuxing Official’s story.

In terms of time, location, and details of belief, the references to Taiping Guangji and Shishi Liutie may be erroneous, as both of them overlap too closely with the description in Mingxiangji, while Youminglu does not record any stories of Buddha or Bodhisattva responded to the prayers. In terms of writing style, the version in Guangshiyin Yingyanji is undoubtedly the most realistic and detailed. However, Xuanyanji predates the Lu edition, and both mention the same period, suggesting that they may be different versions of the same story that share the same source.

These textual systems also differ significantly in terms of belief: Xuanyanji describes the worship of sacred objects and tells stories about visiting the underworld, the Lu edition describes the Bodhisattva faith in Buddhism, while the objects of fulfillment in Mingxiangji encompass all Buddhist elements. Overall, the Lu edition serves as a compromise between the other two. Although the Lu edition is the youngest of the three, and its composition references both Xuanyanji and Mingxiangji, it is challenging to determine whether or not it directly draws from the others due to its intricate storytelling. It is worth noting that the Lu edition records the version from the Wuxing region, which aligns with the point on regional memory discussed earlier.

- Lu-24: Guo Xuan

- Direct source: Possibly Guo Xuan’s testament

- Parallel texts: Bianzheng Lun quoting Xuanyanji, Fayuan Zhulin quoting Mingxiangji, Shishi Liutie, Taiping Guangji quoting Bianzheng Lun, Shishi Tongjian(釋氏通鑒) quoting Seng Shi (僧史).

The essence of this story is that, in the 11th year of the Yixi era (AD 415), Guo Xuan and Wen Chumao were imprisoned due to being implicated in the indiscriminate killings committed by the Liangzhou magistrate. In prison, they both made vows that, if they were released, they would engage in meritorious deeds in a temple, and later they were saved. The Lu edition specifically mentions at the end that Guo Xuan left behind a “testament”, which is likely one of the sources for this story.

Among the various versions of the story (see Table 3), the account in Mingxiangji is particularly unique. Not only does it not mention Wen Chumao, as seen in other texts, but it is also the only narrative where the vow is made after witnessing auspicious signs. Additionally, the details about the signs and their fulfillment are entirely different. It can be concluded that Mingxiangji represents an independent textual system with a unique format.

Table 3.

The differing versions of the Guo Xuan’s story.

Although the story is primarily associated with the Xuanyanji system, there are still differences in details among different versions. For example, although Wen Chumao appears as a co-vower in the Lu edition, the breaking of vows portion is omitted. This omission is consistent with the Xuanyanji system and one other.46 While all versions feature the devotion to Guanyin as a form of belief, the auspicious signs obtained vary. On the other hand, the original Yingyan system suggests that the Bodhisattva seen in the dream is not Guanyin, while the Lu edition contains a version that involves a belief in the divine monk Ba Chi Dao Ren.47

Interestingly, this story is either forged or partially fictional. According to the Book of Jin: Annals of Emperor An, Liang Zhi Jing, the governor of Liangzhou, was executed as early as July in the second year of the Yi Xi era (AD 406), ten years before the story took place. Moreover, both individuals who were officials in Liangzhou were imprisoned in Jingzhou instead of being imprisoned locally or at the capital. This suggests that this story was circulating in the context of Jingzhou. This is further supported by their performance of religious ceremonies at Shangmingxi Temple in Jingzhou after their release.

Through recipients of these two stories, it is evident that Xuanyanji and Mingxiangji not only differ in their dissemination systems but also in the details of the stories and their implied meanings. The Yingyanji, which emphasizes specific objects of belief and regional memory, often inherits from the former. This is different from Xuanyanji, which mainly recorded Zhiguai occurrences centered around the Jingzhou region. Mingxiangji not only confirms its devout belief in its preface, but also aims to propagate Buddhism externally. Therefore, its miraculous objects are not limited to specific bodhisattvas or sacred objects, but encompass various Buddhist elements such as pagodas, statues, and scriptures, not to mention that the regions and themes it includes are broader. To a large extent, this breaks the pattern of narrative-style verification and develops into an evangelistic-style record of verification, eventually inherited by the likes of Mingbaoji, etc.

3.3. Categories of Zhiguai, Yingyan, and Gantong Dissemination Systems

Komina Ichirō once classified Six Dynasties literature into two categories: Zhiguai and proselytization (Komina 1982, pp. 415–500). However, this classification did not include forms of dissemination found in Buddhist texts such as biographies of monks, making it incomplete. Furthermore, he did not discuss differences in the dissemination of stories between different types of texts. Therefore, the following section will re-examine the relationship between the classification of texts and the transmission of stories in different systems.

Previous research has focused on the evolutionary relationship between Zhiguai (annals of the bizarre) and chuanqi (miracle) literature. However, few scholars have noted that these supernatural stories also use different systems of writing depending on the authors’ perspective. Due to these different perspectives, we can associate Zhigui writings with non-Buddhist believers, Yingyan writings with lay practitioners who have Buddhist beliefs, and Gantong writings with Buddhist monks (see Table 4).

Table 4.

The different systems of miracle stories.

If the purpose of the Zhiguai system is to preserve extraordinary and unusual events, then the purpose of the Yingyan system is to facilitate the exchange of faith-based stories among fellow Buddhist believers. Based on their objectives and source of information, Yingyan writings can be further divided into two types: the descriptive style of Yingyan that emphasizes regional memories and bears resemblance to Zhiguai-style writings, and the propagative style Yingyan writings which have a broader range of source materials and stronger emphasis on spreading Buddhism. Additionally, there are also Gantong writings, which include biographies of monks, exegesis of scriptures, and Yingyan narratives composed by monks.48

The elements selected and discarded among different systems are illustrated through the stories of Zhu Changshu (Guang-1) and Gao Xun (Xi-15):

- Fu-1: Zhu Changshu

- Parallel Texts: Guanyin Yishu, Fahua Yishu citing Fu edition, Bianzheng Lun citing Jinlu (晉録), Mingxiangji, Fayuan Zhulin citing Mingxiangji, Fahua jing Wenju Fuzheng Ji, Shishi Liutie citing Jinlu, Mingxiangji, Fahua Zhuanji citing Fayuan Zhulin, Taiping Guangji citing Bianzheng Lun.

Transmission Systems:

- Fu edition --> Jinlu, Mingxiangji --> Bianzheng Lun, Shishi Liutie --> Taiping Guangji.

- Fu edition --> Mingxiangji --> Treasury of the Dharma, Fahua Zhuanji.

- Fu edition --> Guanyin Yishu, Fahua Yishu, Lotus Sutra Fuzhengji.

The Zhiguai system originated from Jinlu and Mingxiangji. Compared to the Yingyan system, the content in Zhiguai represents a localized version of the Wu region, likely based on the narrative in Jinlu.49 This system was first recorded in Bianzheng Lun and was later included in Shishi Liutie and Taiping Guangji. The characteristic of this system is that the texts are mostly compiled works, often directly copied with little modification (see Table 5).

Table 5.

The differing versions of the Zhu Changshu’s story.

The Yingyan system is based on the Fu edition and is included in Mingxiangji, as well as Fayuan Zhulin and Fahua Zhuanji. This system has the largest overlap with the Fu edition. Both Mingxiangji and Fayuan Zhulin are texts with strong missionary undertones, but due to the way they were compiled, they have not undergone significant modification.

These systems were mostly authored by laypeople or heavily influenced by lay authors and emphasize religious practices such as reciting scriptures. They focus on the manifestation of religious behaviors and demonstrate the repetitive nature of these actions. The Gantong system, on the other hand, within the context of religion, emphasizes the mystery of things themselves and focuses on explaining the immediacy of fulfillment and the sanctity of the object of belief. Therefore, it tends to modify actions to better reflect the names of the objects of belief. At the same time, the Gantong system tends to simplify and dehistoricize narratives, either by omitting time references or changing the historical timeline to match that of the event, making it the most extensively modified textual system (see Table 6).

Table 6.

The timeline of varying versions of Guo Xuan’s story.

- Lu-15: Gao Xun

- Direct sources: Shuzhengji and Zhenyiji

- Parallel texts: Guanyin Yishu citing Fu edition, Bianzheng Lun citing Xuanyanji and Xusou Shenji, Fahua jing Wenju Fuzheng Ji, Taiping Guangji citing Xuanyanji, Sanbao Ganying Yao Luelu citing Xuanyanji.

This particular system has already been analyzed above. The two systems differ not only in names used for the main characters, but also in their recorded year of death. The Xuanyanji system states the fifth year of the Taiyuan Era (AD 370), while the Guangshiyin Yingyanji and subsequent Gantong systems state the seventh year of the Taiyuann Era (AD 372). The transmission context is as follows(Figure 2):

Figure 2.

The transmission of the Gao Xun’s story.

The Zhiguai system presents “Buddhist deities” (佛神), which are more realistic and imbued with local elements, while also emphasizing their divine power. In contrast, the Yingyan system in the Lu edition highlights the compassionate power of Guanyin Bodhisattva in the Western Pure Land, who can save people. The Gantong system, on the other hand, presents a brief narrative, emphasizing beheading and the shattering of a sword, as well as the act of selling oneself and one’s wife to support the monks.

The practice of removing or altering specific timeframes is also commonly seen in Gantong writings, particularly in stories involving miraculous monks such as Shi Daojun (Xuan-6),50 Shi Senghong (Xuan-22),51 and Guo Xuan (Xuan-24). Among various records, only the Shishi Yaolan (釋氏要覽) does not include any temporal references.52 However, this practice is mainly observed in the narration of miraculous monks. In the “Yi Jie” chapter in Zhu Fa Yi, though there are fantastical accounts of miracles, his biographical content, copied mainly from Shamen Tanzongsiji, includes records of studying under the famous monk Shengong, delivering sermons, and having the emperor build a temple and burial site for him. Therefore, this biographical style prioritizes realism and the preservation of time and place, while the accounts of miracles become secondary and supporting narratives.

Differences in miracle stories among different systems are not uncommon. When Sun Shangyong studied the legend of “Fish Mountain and the Brahman Chant” (魚山梵唄), he pointed out that this story was first recorded in Yiyuan (異苑), which included two different versions: one about the Brahman chant and the other about Taoist illusionary footsteps. However, only the version of the Brahman chant survived and developed into various interpretations, such as transferring merits through chanting scripture, or performing the Brahman chant (S. Sun 2008, pp. 144–48).

Due to the long history of dissemination, many accounts of miraculous stories from different systems have been lost. The existing versions are primarily preserved in texts with a Buddhist perspective, giving one the impression of coherence and consistent views. Working to clarify the different dissemination contexts of miracle stories helps one grasp the nature of different texts and their underlying historical background. This, in turn, helps one break away from the traditional narrative of Buddhist history, allowing the stories to be examined within their original temporal and spatial contexts. Stories are disseminated by multiple actors in the process of being transmitted, and the stories themselves are constructed by participants such as eyewitnesses, storytellers, transmitters, recorders, as well as local memories. Hence, it becomes apparent that multiple actors with diverse perspectives are involved in disseminating, rewriting, and piecing together these stories. By analyzing and dissecting these various elements, these stories can be better placed within their original historical contexts and more accurately understood.

4. Conclusions

From this analysis, it may be observed that the original intention of Yingyanji was not to propagate Buddhism, but rather to serve as a collection of religious stories circulated among the scholarly elite. It bears the dual characteristic of familial and regional memory. Different Yingyan writings demonstrate variation in their perspective, have different purposes, and use different sources. They may not necessarily have been written with a clear intention for use in propagation. Thus, the generalization of Shishi Fojiao zhi shu (Books for Assisting Buddhist Teaching) ought to be reconsidered. This concept should be examined under the spectrum of Zhiguai and Gantong, while the influential relationship between stories intended “to preach to people and lead them to conversion” and Yingyan writings ought to be inverted.53

Different texts demonstrate variation in their attitude toward and handling of supernatural stories. To substantiate their claims, both Zhiguai and Yingyan writings often adopt a biographical style of narration while including descriptions of the scenes. Guangshiyin Yingyanji contains many stories related to the author’s personal acquaintances, including many details and sources unrelated to the main story. The Gantong system, however, abandons this realistic narrative technique. The narratives of the monk biographies rely primarily on documentary sources such as scripture or temple records. Supernatural narratives are imposed as separate story blocks, with less focus on time, place, and source.

Due to the limited availability of visual images and documentary materials from the Six Dynasties period, our understanding of Buddhist beliefs during that time has often been limited to a few objects of worship, such as Guanyin and Amitabha. However, through different versions of miracle stories and the stratification of their dissemination, we can see a more diverse religious landscape. Just because certain objects of worship or scriptures are less frequently mentioned or recorded does not mean their value is lesser. The fact that a story or piece of scripture has been altered or deleted only goes to demonstrate its significance during that period. Only by continuously excavating obscured narratives can we better reconstruct religious landscapes in their historical contexts.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares that there are no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

T Taishō shinshū daizōkyō 大正新脩大藏經 (Taishō edition of the Buddhist canon). Ed. Takakusu Junjirō 高楠順次郎 et al. 100 vols. Tokyo: Taishō Issaikyō Kankōkai, 1924–1935. X Manji Shinsan Dainihon Zokuzōkyō新纂卍續藏 (New Compilation of Buddhist canon) Ed. Kawamura Kōshō 河村孝照 et al. 90 vols. Kyoto: Zōkyō shoin, 1975–1989. B Supplement to the Dazangjing大藏經補編 et al. 36 vols. Taipei: Lan Jifu 1985.

Notes

| 1 | The term “Buddhist auxiliary texts” was proposed by Lu Xun (1881–1936) in the early 20th century. Lu Xun is considered the founder of modern research on ancient Chinese novels and one of the most important researchers in ancient Chinese literature. “Buddhist auxiliary texts” was the earlier definition for Buddhist miracle stories. It emphasizes the difference from normal Chinese novels and the purpose of Buddhist proselytizing. This concept was widely accepted by later researchers. More broadly, Lu Xun defined “Buddhist auxiliary texts” as a kind of Zhiguai. Reconsidering the definition of “Buddhist auxiliary texts” in this approach helps us understand the complexity of Zhiguai and the development of medieval novels. |

| 2 | The main research can refer to the work of Liu Huiqing, Leng Yan, and others. In addition, there are some influences on the thought of reincarnation and other genres of Buddhism, which have also been discussed by scholars. (X. Li 2015; H. Liu 2013, 2019; Jin 2016, pp. 118–21; Leng 2019; Huang 2013, pp. 119–20; Peng and Zhou 2019, pp. 145–51). |

| 3 | Changdao refers to a preaching procedure in Buddhist rituals, where the speaker uses plain language and Vipāka, or fateful stories, to explain the principles and teachings found within Buddhist scriptures to the audience. |

| 4 | Research on the relationship between “preach[ing] to people [to] lead them to conversion” and “Buddhist auxiliary texts” primarily relies on evidence from later Tang Dynasty commentaries, variant texts, and sermon texts to make inferences. This may be related to the perspective of considering the Jin and Tang Dynasties as a unified entity in relevant studies. Among them, the discussion by Li Xiaorong is the most comprehensive. He believes that oral chanting, accounts of miraculous experiences by laypeople, and extensive records of knowledge are the three creative sources of these stories, which broadly summarize the various motives for the creation of the “Books of Buddhist Auxiliary Teaching”. However, he still does not explain why accounts of miraculous experiences by laypeople predate those by monks. Related studies can be referred to: (Hu and Zhou 2013, pp. 64–70; G. Zhang 1995, p. 10; E. Zhang 2007, pp. 43–46; X. Li 2015, pp. 48–57). |