The

Qisha Canon 磧砂藏 is a significant Buddhist Canon that underwent carving during the Song Dynasty, supplemented in the Yuan Dynasty, and further revised in the Ming Dynasty. It includes 591 cases, 1517 titles, and 6363 volumes in total.

1 It has had a profound influence on Chinese Buddhism, with its format and content greatly impacting the

Hongwu Southern Canon 洪武南藏 and the

Yongle Southern Canon 永樂南藏, both carved during the Ming Dynasty.

The name “Qisha Canon” originated from its printing location at the Yansheng Cloister 延聖院 in Pingjiang Prefecture 平江府 (modern Suzhou 蘇州). In the 1920s and 1930s, the Canon was discovered in Shanxi 陝西 in China and subsequently reproduced through facsimile printing. Regrettably, the Shaanxi version’s first part, the Da banruo jing 大般若經, was largely replaced by the printed editions carved at Miaoyan Monastery 妙嚴寺 in Huzhou during the Yuan Dynasty. As a result, the precise origins of the Qisha Canon’s production process have yet to be definitively uncovered, remaining a compelling mystery for scholars.

1. Introduction

Five scholars have focused on the first segment of the Qisha Canon. Below are their findings in chronological order:

Kawase (

1938) made the initial discovery of the original

Da banruo jing 大般若經 from the

Qisha Canon, which is housed in Saidaiji 西大寺 in Japan. Through his research, Kawase proposed that the composition of the Canon took place between the years 1216 and 1242.

Yamamoto (

1973, pp. 100–1) further categorized these

Da banruo jing into three distinct sections. The first section comprises the initial twelve volumes, overseen by the monk Liaoqin了懃, with assistance from both monastic and lay individuals from the surrounding Pingjiang Prefecture. Notably, this section exhibits a rare “calligraphic style” (寫刻體) of the script. The second and third sections were primarily undertaken by a prominent new patron named Zhao Anguo 趙安國, employing the standard script (楷體) as the script style.

Kajiura (

1992, pp. 13–15) conducted further research and supplemented the findings by noting that each sheet of the twelve volumes undertaken by Liaoqin was originally composed of two separate sheets of paper. One sheet contained twenty-seven lines, while the other sheet contained three lines. These two sheets were later pieced together to form a single sheet. This is in contrast to the later parts of the Canon, which were printed on a single sheet of paper. Additionally, it is worth noting that eight of these volumes are accompanied by the

Neidian suihan yinshu 內典隨函音疏, a compilation by Xingtao 行瑫 (895–956), which serves as an early Buddhist glossary that survives today only in fragments.

Nakamura (

1994, pp. 4–5) pointed out that there was no mention of a direct connection between the twelve volumes and the Qisha Yansheng Cloister 磧砂延聖院. Therefore, he believed that the initiative was taken personally by Liaoqin and later inherited by Zhao Anguo. Furthermore, historical documents do not provide much information about Liaoqin beyond the colophons. Consequently, little is known about Liaoqin’s life, the purpose behind the scripture carving, and the relationship with the

Qisha Canon.

The aforementioned scholars primarily relied on investigation reports from Saidaiji’s collection. However, it is noteworthy that the Imperial Household Agency 宮內廳 in Japan also houses 579 volumes of the

Da banruo jing of the

Qisha Canon.

2 In 2016, the complete digital images of this collection were made publicly available on the website (

http://db.sido.keio.ac.jp/kanseki/T_bib_body.php?no=023001 (accessed on 1 August 2023)), providing researchers with firsthand resources for their studies. Nevertheless, there are notable differences between the two collections. For example, the Imperial Household Agency version has incomplete volumes, with the first and last volumes missing. Additionally, there are missing contents, including approximately 600 characters of colophons in Volumes 5 and 6, and the name of engraver Fang Xin 方信 is missing in Volume 6. Therefore, combining both sources from different collections allows for a more comprehensive understanding of the

Qisha Canon.

The twelve volumes supervised by Liaoqin (referred to as Liaoqin’s Section below) hold a significant position as the earliest engraved section of the

Qisha Canon.

3 However, there are some important questions worthy of closer examination: firstly, what distinguishes these twelve volumes from other engraved canons? Secondly, why is the long-lost

Neidian suihan yinshu attached to this section? Thirdly, who is the person in charge, Liaoqin, and what is his identity? Lastly, under what circumstances were the texts carved?

In brief, uncovering historical records and conducting in-depth research can shed light on the specific context, motivations, and factors that contributed to the production of the Canon.

2. The Original Source of the Twelve Volumes

2.1. Variations from Other Engraved Canons

The process of engraving canons exhibits a certain continuity, with later canons often tracing their origins back to earlier editions. According to

Fang (

1991) and

Masaaki (

2000), printed canons can be categorized into three textual systems: (1) the central tradition based on the

Kaibao Canon 開寶藏, which includes the

Goryeo Canon 高麗藏 and the

Jin Canon 金藏; (2) the northern tradition based on the

Khitan Canon 契丹藏; and (3) the southern tradition based on the

Chongning Canon 崇寧藏, which includes the

Sixi Canon 思溪藏 and the

Qisha Canon. However, Liaoqin’s Section, both in terms of external typography and colophon, as well as internal textual content, exhibits notable differences from other engraved canons.

Firstly, it is noteworthy to examine the typography and colophon of Liaoqin’s Section. A meticulous observation reveals the presence of curved strokes, both horizontally and vertically, which distinguishes it from the prevalent straight and square typography typically encountered in other engraved canons.

Table 1 provides a clear visual representation of this notable distinction.

The second distinction between Liaoqin’s Section and other engraved canons is evident in the content of the scriptures. While the

Qisha Canon is traditionally associated with the southern system, following the lineage of the

Sixi Canon, Liaoqin’s Section displays significant deviations.

Table 2 visually demonstrates the remarkable similarity in vocabulary and textual content between Liaoqin’s Section and the canons of central tradition, specifically the

Goryeo Canon and the

Jin Canon.

Furthermore, Liaoqin’s Section exhibits vocabulary differences that align with the canons of the southern system but deviate from those of the central system. Notably, certain phrases in Liaoqin’s Section, such as “如我詞曰” (as my words say) in Volume 2, differ from the equivalent phrases “如我辭曰” found in the Goryeo Canon and the Jin Canon. Similarly, “摧眾魔怨” (destroying the resentment of countless demons) in Volume 3 contrasts with “摧眾魔冤” in the Goryeo Canon and the Jin Canon. Furthermore, “白佛言” (spoke to Buddha) in Volume 9 differs from “白言” used in the Goryeo Canon and the Jin Canon. These examples highlight the complex usage of vocabulary in Liaoqin’s Section, which does not conform solely to a specific canon.

2.2. Relationship with Handwritten Buddhist Canons of the Northern Song Dynasty

Liaoqin’s Section shows notable distinctions when compared to existing engraved canons, prompting inquiries into their original source. After a thorough examination, it appears highly plausible that Liaoqin’s Section was derived from handwritten Buddhist canons of the Northern Song Dynasty.

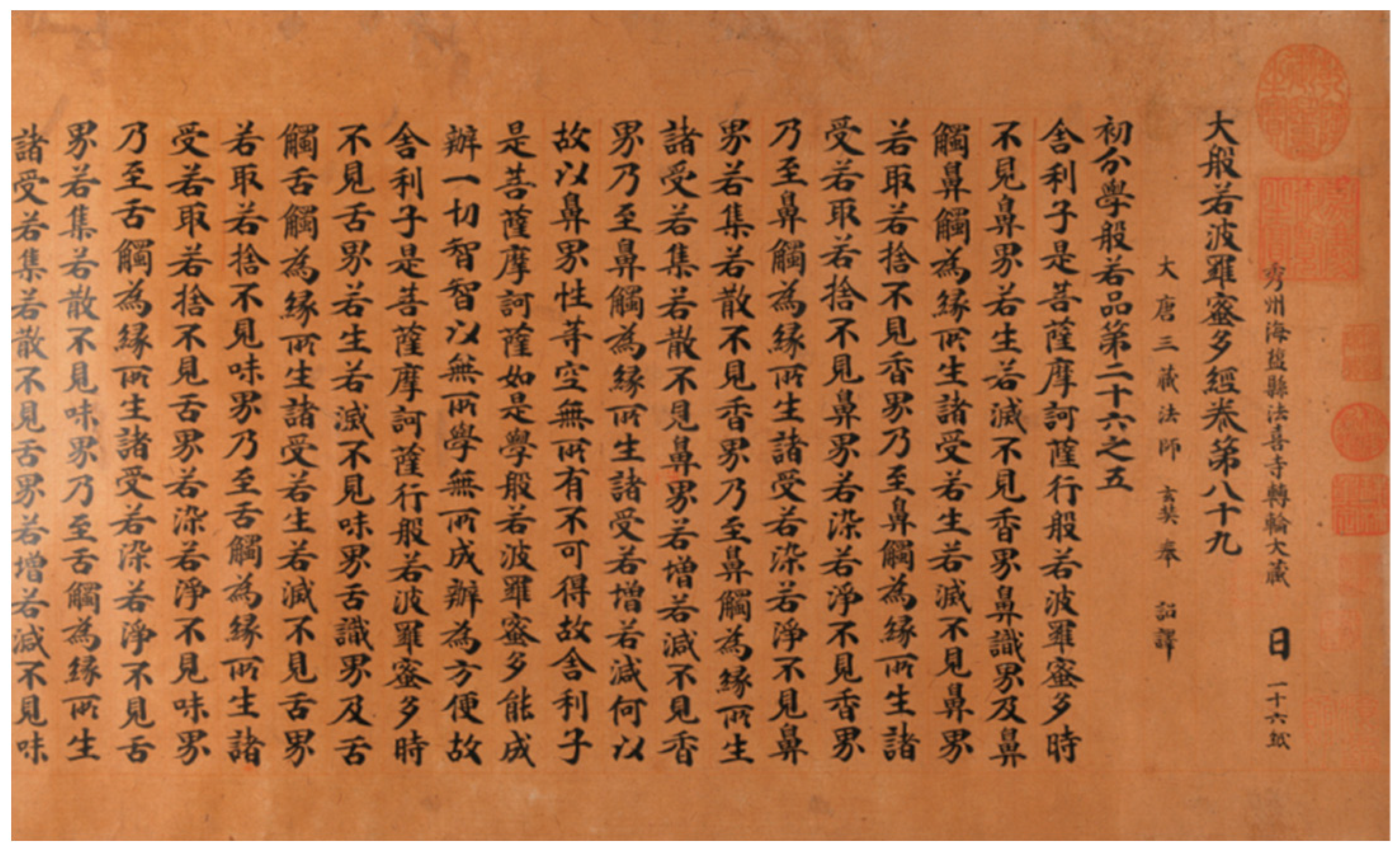

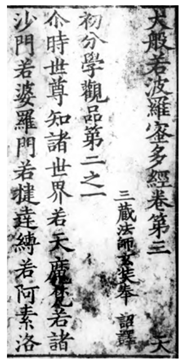

Firstly, the typography is particularly striking. The characters found in Liaoqin’s Section exhibit a distinctive style of script, characterized by large curvatures in each stroke, as opposed to being strictly horizontal and vertical. The typography of Liaoqin’s Section bears a resemblance to the typographical characteristics commonly observed in handwritten Buddhist canons of the Northern Song Dynasty. For instance, the

Faxi Monastery Canon 法喜寺大藏經, as shown in

Figure 1:

Moreover, the typographical style of the handwritten Buddhist canons of the Northern Song Dynasty exhibits a certain degree of consistency, although distinct variations can be observed among different volumes. For instance, the

Jinsu Mountain Canon 金粟山大藏經, a renowned handwritten Canon, showcases both square and plump styles in certain volumes, as well as a slender and loose style in others (

Cai 2010, p. 27). This characteristic is similarly evident in Liaoqin’s Section. Notably, the seventh, eighth, and tenth volumes exhibit a relatively square appearance, contrasting with the remaining volumes.

Secondly, Liaoqin’s Section features the usage of certain vulgar forms that are rarely seen in other engraved canons. However, these forms can also be found in the handwritten Buddhist canons of the Northern Song Dynasty. Several examples are provided in

Table 3.

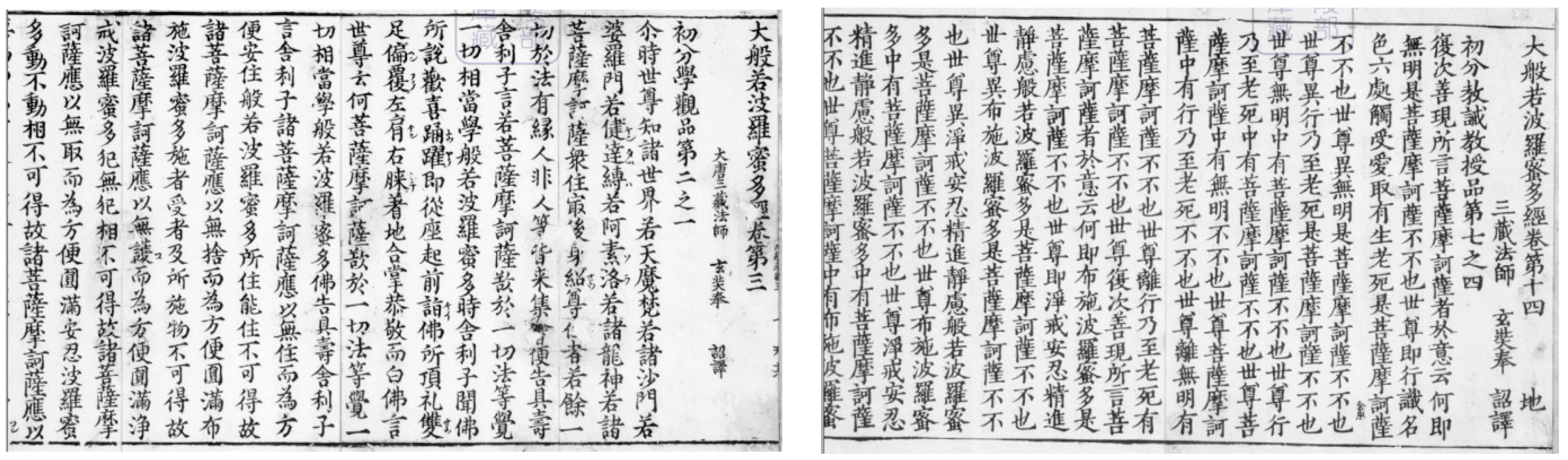

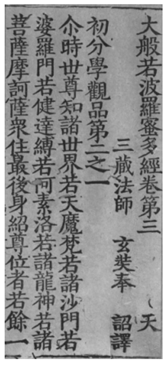

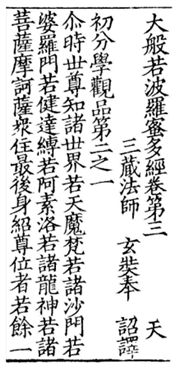

Thirdly, the format of Liaoqin’s Section exhibits similarities to handwritten canons but distinguishes itself from the engraved canons prevalent in Southern China during the Song Dynasty. Typically, these engraved canons feature a binding style with larger line spacing between the folds compared to other lines. However, as depicted in

Figure 2, the line spacing in Liaoqin’s Section is generally uniform throughout, unlike Zhao Anguo’s Section, which exhibits larger line spacing every six lines. The format of Liaoqin’s Section, resembling scroll-bound scriptures, bears resemblances to handwritten Buddhist canons of the Northern Song Dynasty, such as the

Jinsu Mountain Canon,

Haihui Monastery Canon 海惠院大藏經,

Faxi Monastery Canon 法喜寺大藏經, and

Chongming Monastery Canon 崇明寺大藏經.

The investigation report of the

Da banruo jing in Nara Prefecture includes images of Volume 1 and Volume 6 of Liaoqin’s Section from Saidaiji, where distinct folds can be observed every six lines (

Nara Prefectural Board of Education 1992, plates 6, 7). However, these folds are not visible in the image files published by the Imperial Household Agency. It is noteworthy that in the handwritten Buddhist Canon of the Northern Song Dynasty,

Jinsu Mountain Canon, the original Volume 264 of the

Neidian suihan yinshu was initially scroll-bound but later changed to a folded format, resulting in visible folds on the paper. Based on this observation, it is highly plausible that Liaoqin’s Section was also initially scroll-bound, and some of them subsequently converted to a folded format.

Moreover, it is notable that Liaoqin’s Section features distinct separations between each section, indicated by blank spaces, with the subsequent section starting on a new line. This formatting style aligns closely with the practices commonly observed in handwritten Buddhist canons of the Northern Song Dynasty. Additionally, Liaoqin’s Section adheres to a consistent structure of 30 lines per sheet, with 17 characters per line, mirroring the characteristic format of handwritten Buddhist canons.

9Fourthly, an important aspect to consider is the content of the scriptures.

Cai (

2010, pp. 123–32) has identified several notable characteristics in the

Jinsu Mountain Canon. Upon comparison, it becomes apparent that these characteristics are also present in Liaoqin’s Section. These shared characteristics include inconsistent usage of characters, occasional errors in characters, and the presence of elements from both the Central system and Southern system canons.

In terms of inconsistent character usage, variations of the same character can be observed within the same volume of Liaoqin’s Section. For example, both “猶豫” and “猶預” are used, as well as “結跏趺坐” and “結加趺坐”. Furthermore, Volume 2 of Liaoqin’s Section contains instances of erroneous character usage, such as “威德” mistakenly written as “威得”. Other examples include the repetitive occurrence of “童男童女” written as “童子童女”, “及佛身相” written as “及諸身相”, and “氣力調和” written as “氣力詞和”, among others. Moreover, Liaoqin’s Section exhibits vocabulary and textual content similarities with canons from both the Central system (such as the Goryeo Canon and the Jin Canon) and the Southern system (such as the Fuzhou Canon and the Sixi Canon), as previously discussed.

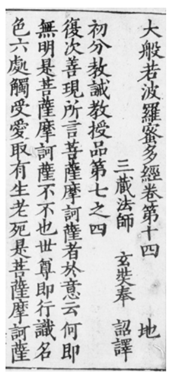

The final aspect to consider is the presence of certain special markings. For instance, in Liaoqin’s Section, when annotating the translators in each volume, the phrase “大唐三藏法師玄奘奉詔譯” (translated by the Tripitaka Master Xuanzang from the Great Tang Dynasty by imperial decree) is used. This specific use of “大唐” (Great Tang) is not found in corresponding positions in existing engraved canons but can be found in handwritten Buddhist canons of the Northern Song Dynasty.

10Another noteworthy example is the format of the colophon at the end of Volume 1 of the

Da banruo jing, which follows the pattern “時 (at the time) + 皇宋 (Imperial Song) + regnal year + sexagenary cycle year + specific date + 首/起首 (start) +寫造 (written)”. This format is exceedingly rare among various engraved canons, but it aligns consistently with the conventions of handwritten Buddhist canons of the Northern Song Dynasty, as illustrated in

Table 4.

The editions of handwritten canons listed in

Table 4 were produced in locations such as Haiyan County, Huating County, Jurong County, and Kunshan County, which were geographically close to Lin’an Prefecture or Pingjiang Prefecture. This proximity provided Liaoqin’s Section with access to these regional editions as their primary source.

Now we can address the question of why the

Neidian suihan yinshu is found in Liaoqin’s Section but not commonly in other parts of the

Qisha Canon or other carved canons. The reason can be traced back to the fact that the first part of the

Qisha Canon was based on handwritten manuscripts from the Northern Song dynasty, which also included the

Neidian suihan yinshu at the end of certain volumes. It is worth noting that only a few scattered volumes of the

Neidian suihan yinshu have survived, and among them, the 264th and 307th volumes are precisely the ones included in the

Jinsu Mountain Canon.

11Furthermore, scholars often refer to the colophon of Volume 1 of Liaoqin’s Section to support the claim that the

Qisha Canon was initially published in the ninth year of Jiading 嘉定 (1216) (e.g.,

Li 1998, p. 73;

Li and He 2003, pp. 262–63). However, it is important to note that the term used in the colophon, “written” (

xiezao 寫造), differs from the terms “engrave” (

kan 刊 or

diao 雕) used in later colophons. The term “written” typically denotes the pre-carving writing process rather than the actual carving of the Canon.

Why does Volume 1 only mention the year of writing and not the year of carving? The reason for this is that when the colophon of Volume 1 was created, the actual carving work had not yet commenced. While the project’s origin is associated with Huzhou, the carving process was planned to take place in either Lin’an Prefecture or Pingjiang Prefecture. In the colophon of Volume 1, Liaoqin, who was responsible for the first three volumes, is mentioned as a donor rather than a carver. Therefore, the year 1216 mentioned in Volume 1 signifies the initial stage of writing, indicating the commencement of fundraising and writing activities. It does not indicate the official start of the carving process. The actual year of the Qisha Canon’s initial publication is likely to be after 1216 (the year of writing) and before 1222 (the year when Volume 2 was published). Based on the carving timeline, a more plausible estimate would be around 1220.

3. Liaoqin: An In-Depth Examination

Liaoqin, the key figure behind the initiation of the Qisha Canon’s publication, remains without a documented biography in existing historical records. Nevertheless, valuable insights into his background, responsibilities, and experiences can be gleaned through an examination of his work and place of origin.

3.1. Liaoqin’s Role in the Production of the Canon

Liaoqin’s name is mentioned seven times in the colophons of the twelve volumes. He is referred to as “supervisor” (gan zhi 幹製 or gan zao 幹造), indicating his role as the person in charge of manufacturing. This suggests that Liaoqin oversaw the entire project. Notably, the colophon in Volume 2 emphasizes Liaoqin’s specific contributions to the work:

幹造比丘了懃捨梨板三十片,刊般若經弟一二三卷,并看藏入式及序,祈求佛天護祐,令大藏經律論板速得圓滿。

The supervisor Liaoqin donated 30 woodblocks to carve the first three volumes of the Da banruo jing. He also made sure that the canon followed the correct archetype (shi 式) and arrangement (xu 序). He wished the project to receive the Buddha’s blessing and protection so that the carving of the sūtra, vinaya, and śāstra contained in the canon could be completed quickly.

Liaoqin’s last known involvement in the Qisha Canon project is indicated in the colophon of Volume 6, dated the first year of the Baoqing 寶慶 era (1225). Subsequently, it is likely that he gradually disengaged from the project, and no further records of his participation are available.

3.2. Liaoqin’s Hometown and Background

Where was Liaoqin from? In Volume 1 of the Qisha Canon, there are 26 colophons and five of them are attributed to Liaoqin, which does not mention his hometown. However, the other colophons in Volume 1 are attributed to donors from Huzhou Prefecture, which is located near Lin’an Prefecture. This indicates that Volume 1 was fundraised in Huzhou.

In contrast, in Volumes 2 to 12, the majority of colophons are attributed to donors from Lin’an Prefecture, and there are no colophons from Huzhou. This suggests that the subsequent volumes were fundraised in Lin’an.

Considering that most of Liaoqin’s donations are found in Volume 1, and none of them mention his hometown, it strongly implies that Liaoqin’s hometown is also in Huzhou. The colophons in Volume 1 provide additional evidence to support this assumption.

Colophon 10: 乾造比丘了懃長財代為先考姚九承事雕四百九十九字。

Supervisor monk Liaoqin, on behalf of the deceased father Yao 姚, who held the ninth rank in his generation and had the official title Chengshi 承事, carved four hundred and ninety-nine characters.

Colophon 11: 幹造比丘了懃長財代為先妣沈氏四娘子雕五百六字。

Supervisor monk Liaoqin, on behalf of the deceased mother, Madam Shen 沈, who held the fourth rank in her family, carved five hundred and six characters.

Colophon 18: 湖州樂舎姚十郎名政,代為先考姚九承事雕五百十字。

Yao Zheng 姚政 from Leshe in Huzhou, who held the tenth rank in his generation, on behalf of the deceased father Yao 姚, who held the tenth rank in his generation and had the official title Chengshi, carved five hundred and ten characters.

Colophon 19: 湖州樂舎姚十郎名政,代為先妣沈氏三娘雕五百六字。

Yao Zheng from Leshe in Huzhou, who held the tenth rank in his generation, on behalf of the deceased mother, Madam Shen 沈, who held the third rank in her generation, carved five hundred and six characters.

Firstly, Liaoqin’s donation is closely associated with another donor, Yao Zheng 姚政 from Huzhou. In Colophon 18, Yao Zheng’s father is identified as “姚九承事”, which is the same as Liaoqin’s father mentioned in Colophon 10. In Colophon 19, Yao Zheng’s mother is referred to as “沈氏三娘” who held the third rank in her generation, while Liaoqin’s mother is mentioned as “沈氏四娘子” who held the fourth rank in her generation in Colophon 11. This suggests that Yao Zheng and Liaoqin may have had the same father but different mothers.

Secondly, from the aforementioned colophons, it is evident that Liaoqin’s father had the surname Yao, while his grandmother, mother, maternal grandfather, and maternal grandmother shared the surname Shen. The surnames Yao and Shen prominently appear among all the colophons in Volume 1, indicating their popularity. According to the Jiatai wuxing zhi 嘉泰吳興志 section on prominent surnames (Zhu xing 著姓), the surnames Yao and Shen are indeed prominent local surnames in Huzhou.

Therefore, it is highly probable that Liaoqin’s hometown is Huzhou, specifically in Leshe in Deqing, which is the same as Yao Zheng’s. This suggests that the entire project of carving canons originated in Liaoqin’s hometown, where he organized donations from his own family and subsequently extended the project to involve others.

3.3. Life Experiences and Contributions of Liaoqin

In the surviving local gazetteers of the Song and Yuan dynasties, two records mention an individual named Liaoqin who was active in and around Lin’an Prefecture.

12The first recorded event pertains to the construction of the Fuxi Bridge 浮溪橋 in Yuqian County 於潛縣, situated in Lin’an Prefecture. This significant historical occurrence was meticulously documented by Li Tingzhong 李廷忠, a teacher in the county. According to Li’s account, the Fuxi Bridge served as an essential transportation route but suffered a collapse in the autumn of the year 1194. In response to this pressing issue, the newly appointed county magistrate, Zhao Yantan 趙彥倓, took the initiative to organize the construction of a stone bridge. The local residents wholeheartedly contributed funds for the project, and their enthusiastic support led to the successful completion of the bridge the following year. Notably, Liaoqin, a respected monk renowned for his exceptional skills in planning and management, played a pivotal role in this endeavor.

13The second record is documented in the

Anyangyuan ji 安養院記, written by Shi Zongwan 石宗萬, who served as the county magistrate of Chun’an County 淳安縣 in Yanzhou Prefecture 嚴州, which is adjacent to Lin’an Prefecture. This historical text details the establishment of a nursing home in the western part of the county, with specific mention of Liaoqin’s notable contribution. According to the text, the Monk Liaoqin generously donated five acres of land located in Renshou Township 仁壽鄉.

14Based on the available information, we can affirm that Monk Liaoqin exemplified dedication to public welfare and exhibited exceptional organizational skills. His esteemed status as a monastic figure in the local community likely played a crucial role in garnering widespread support for his publication endeavors.

4. Distribution of Fundraising Locations

Liaoqin’s Section comprises a total of 195 colophons spread across its twelve volumes, with 64 colophons explicitly indicating their respective locations. Among these colophons, all 18 in Volume 1 are situated in Huzhou, while the remaining 46 from Volumes 2 to 12 are located in Lin’an. Within the Lin’an entries, 31 are situated within the imperial city, while 13 are outside the city. Additionally, there are two colophons for which the specific locations cannot be determined.

The distribution of specific volumes in different locations is as follows, with the * symbol denoting places outside the imperial city and the number in brackets indicating the occurrence times:

Volume 1: 湖州忻村 (Xin Village, Huzhou) (2), 湖州精山 (Jingshan, Huzhou), 湖州樂舎 (Leshan, Huzhou) (14)

Volume 3: *下天竺寺前 (In front of Xia Tianzhu Temple), 宰相府巷 (Lane of Prime Minister’s Villa), *九里松行春橋下 (Under the Xingchun Bridge of the Jiulisong), *塩官縣葛奥村 (Geao Village, Yanguan County), *仁和縣金浦村 (Jinpu Village, Renhe County)

Volume 5: *九里松 (Jiulisong), *麹院巷口 (Quyuan Alley Entrance), *下竺寺前 (In front of Xia Tianzhu Temple), 甘斤 (Ganjin) (15),

15 萬松岭 (Wansongling) (2), 太廟前 (In front of the Imperial Ancestral Shrine), 駱駝嶺 (Luotoling), 執政府前大渠頭 (In front of the Governing Office, at the head of the canal), 油車巷 (Youche Alley), 左三廂渡子橋西 (West of the Duzi Bridge of the Left Sanxiang), 丞相府前 (In front of the Prime Minister’s Villa) (9)

16

Volume 6: *九里松 (Jiulisong), 楊和王府 (Villa of Prince Yang of He), *餘杭縣貝村東保 (East Association of Bei Village, Yuhang County), 四條巷 (Sitiao Alley) (2), *玉津園相對 (Across from Yujinyuan), 忉西 (Daoxi), 大學新街 (Daxue Xinjie), 殿前司門首 (In front of the Palace Command Department), 六部後 (Behind the Six Ministries), 宰執閤子内 (Inside the Prime Minister’s Office), 左乙北廂 (North section of the left wing), 鐘公橋北 (North of Zhonggong Bridge), 觀巷 (Guan Alley), 後洋街巷口 (Intersection of Houyang Street and Lane), 朝天門 (Chaotian Gate)

Volume 9: 吳山百法廣潤院 (Baifa Guangrun Cloister on Wushan), 府治後 (Behind the Prefectural Office), *上竺修觀 (Cloister of Shang Zhu), *昇平村獨山前 (Shengping Village, in front of Dushan)

Volume 11: 豐樂橋東堍 (East Pier of Fengle Bridge), 下八界 (Xia Bajie), 執政府前 (In front of the Magistrate’s Office), 鐵線巷 (Tiexian Alley), 柴木巷 (Chaimu Alley), 仁和縣右三廂界居住 (Residence on the Border of the Right Three Sections of Renhe County.)

Volume 12: 臨安府後 (Behind Lin’an Prefecture), 橘元亭 (Juyuanting), 中瓦南大街西岸 (West Bank of Zhongwa South Street)

For a more intuitive display, these locations will be marked on the map of the imperial city, as shown in

Figure 3. The numbers on the map represent the volume in which this location appears, and the superscript in the upper right corner of each number represents the number of repetitions.

In Volume 3, the locations selected for fundraising efforts primarily lie outside the imperial city but gradually extend to encompass areas within the city. Volume 5 presents a noteworthy shift, with fundraising efforts now including prominent locations within the city, such as the foothills of Fenghuang Mountain 鳳凰山, the Taimiao 太廟 (the Imperial Ancestral Shrine), and the Taichang si 太常寺 (the Sacrificial Ceremonies Bureau), which are predominantly inhabited by the imperial nobility. Of particular significance is the Zhaixiang Villa 宰相府 (the Prime Minister’s Villa) located north of the Taimiao, which remarkably appears nine times consecutively, evidently indicating the substantial dedication and efforts of the fundraisers in this specific area. These locations notably lie in close proximity to the administrative center, further highlighting their strategic importance in the fundraising process.

The fundraising locations recorded in Volume 6 showcase the widest distribution, ranging from the Southern Dianqian si 殿前司 (the Palace Command Department) to the Northern Taixue 太學 (the Imperial Academy). However, upon closer examination, it becomes evident that the main focus centers around Yu jie 御街 (Imperial Street), the central thoroughfare, and its surrounding areas. It is worth noting that most of the colophons in Volume 6 are clearly attributed to Liaoqin and are appended at the end of the volume, unlike other colophons scattered throughout the main text. This distinct pattern implies that this section represents a cohesive and unified fundraising effort, likely conducted within a relatively close timeframe, with Liaoqin himself possibly taking an active role in the solicitation process.

In the colophons of Volume 9, only two specified locations are mentioned, both located in the Western part of the imperial city near Qingbo Gate 清波門.

18 As for Volumes 11 and 12, the mentioned locations are primarily situated within the main commercial center of Lin’an Prefecture. Locations such as Fengle Bridge 豐樂橋, Yan Bridge 鹽橋, and Zhongwazi 中瓦子 lay in close proximity to intersecting east-west land routes, indicating their significance as vital economic hubs during that period (

Shiba 2001, pp. 332, 336). These areas likely experienced a considerable amount of trade and commerce, rendering them ideal choices for conducting fundraising efforts.

Furthermore, it is noteworthy that the locations where the colophons are concentrated are often surrounded by numerous Monasteries, such as those near Yan Bridge. Several renowned bookstores of that time are also distributed in these areas, such as Yin Family Bookstore 尹家書籍鋪 before Taimiao and Zhang Family Bookstore 張家文籍鋪 in Zhongwazi (cf.

Mou 2008, p. 96).

The strategic distribution of fundraising locations within the imperial city and its surroundings demonstrates a thoughtful approach that considers both cultural and economic factors.

19 By targeting areas with a high concentration of monasteries, bookstores, and economic activity, the fundraisers maximized their chances of engaging with receptive audiences and securing support for their project.

In addition to the imperial city, a total of 13 fundraising locations are situated outside its boundaries. These locations are generally scattered but predominantly found in or near Qiantang County 錢塘縣 and Renhe County 仁和縣. Notably, three of these locations are in the vicinity of the Upper Tianzhu Monastery 上天竺寺 and Lower Tianzhu Monastery 下天竺寺, while four locations are located near Jiulisong 九里松. The stretch between Jiulisong and Tianzhu Monastery served as the primary distribution area for monasteries, which held significant historical importance and wielded considerable influence during that time. The Upper, Middle, and Lower Tianzhu Monasteries were well-known establishments, while places near Jiulisong, including Jiqing Monastery集慶寺, boasted a scale comparable to that of Tianzhu Monastery (

Mou 2008, p. 97). These regions likely presented a broader base of potential donors, making them conducive for engaging in almsgiving activities.

The farthest locations to the east include Jinpu Village 金浦村 and Shengping Village 昇平村 in Renhe County, as well as Ge’ao Village 葛奥村 in Yanguan County. Renhe County and Yanguan County are neighboring counties, and Jinpu and Ge’ao villages are likely located near their shared border. Moving to the west, the farthest location is Bei Village 貝村 in Yuhang County 餘杭縣. It is located at the northwest boundary of Qiantang County and serves as the junction between Qiantang County and Yuhang County. To the south, the farthest location is Yujin Garden 玉津園, which is situated outside the south gate of the imperial city. This garden was known for hosting royal archery events.

The inclusion of these farthest locations to the east, west, and south indicates that the fundraising efforts of Liaoqin’s Section covered a wide geographical area, encompassing villages and regions both within and outside the imperial city. However, it is noteworthy that the majority of these locations were still concentrated around Lin’an Prefecture, particularly Qiantang and Renhe counties.

5. Relocation of the Carving Project

According to the colophons, Liaoqin’s section of the project spanned from 1216 to 1229. The specific years recorded in each volume’s colophon are as follows: Volume 1 (1216), Volume 2 (1222), Volume 3 (1224), Volume 5 (1225–1226), Volume 6 (1225), Volume 8 (1224), Volume 11 (1229), and Volume 12 (1229). However, starting from the following year, 1230, as recorded in the colophon of Volume 97, the entire project was transferred to Pingjiang Prefecture.

5.1. From Deqing County in Huzhou to the Imperial City of Lin’an Prefecture

Among the 21 specific locations mentioned in the colophons of Volume 1, sixteen are attributed to Leshe 樂舍, three to Jingshan 精山, and two to Xincun 忻村. While the exact location of Jingshan remains unknown, Leshe is situated north of Deqing County, and Xincun is located northeast of Deqing County, approximately fifteen miles away.

20 Based on the available information, it can be inferred that the initial fundraising efforts for the publication of the

Qisha Canon primarily took place in the hometown of Liaoqin, the person in charge, and gradually extended to the surrounding villages. Notably, Deqing County in Huzhou is adjacent to Qiantang County and Renhe County, where the imperial city of Lin’an Prefecture is situated. This geographical proximity might have facilitated the expansion of fundraising activities to encompass areas near the imperial city and its surroundings.

In Volume 2, a notable shift in locations occurs, with the majority of them now situated within Lin’an Prefecture, the administrative center of the Southern Song Dynasty, specifically within the imperial city. It is worth highlighting that the locations mentioned outside the imperial city of Lin’an Prefecture are only specified up to the village level, as mentioned previously. In contrast, the locations within the imperial city are specified with greater precision, such as in front of the Taimiao, Youche Lane 油車巷, and the entrance of the Dianqian si. Interestingly, none of these specific locations are annotated with Lin’an Prefecture or any indication of the imperial city (i.e., 京城, 行在).

On the other hand, in the sections sponsored by Zhao Anguo, specific names of secondary administrative divisions are mentioned, such as Wuxian County 吳縣 in Pingjiang Prefecture (Volume 542), Yongjia County 永嘉縣 in Wenzhou 溫州 (Volume 562), and Kunshan County 昆山縣 in Pingjiang Prefecture (Volume 546). Similarly, in the later part of the Qisha Canon carved during the Song Dynasty, even when locations within the imperial city of Lin’an Prefecture are mentioned, they are explicitly stated with greater precision. For example, the colophon of the Qing guanshiyin jing 請觀世音經 printed in the year 1279 specifies the location as “Fan Tian Monastery inside Jiahui Gate in Lin’an Prefecture (臨安府嘉會門裏梵天寺).

In conclusion, the colophon writers of Liaoqin’s Section assumed that this project was carried out within the imperial city of Lin’an Prefecture, and since most of the donors came from the capital, they deemed it unnecessary to explicitly record the name of the imperial city.

5.2. From the Imperial City of Lin’an Prefecture to Wuxian County in Pingjiang Prefecture

After Volume 12, a significant shift in donation records was observed, with few donations within the imperial city of Lin’an Prefecture, and the entire project focused on neighboring Pingjiang Prefecture. The transition to Pingjiang Prefecture can be attributed to several factors. Pingjiang Prefecture was economically developed, and the publishing industry in the Taihu 太湖 region was flourishing, providing sufficient conditions for the publication of Buddhist scriptures (cf.

Su 1962, pp. 18–19;

Jiang 2019, p. 46). However, Lin’an Prefecture also possessed regional advantages, serving as the administrative center of the Southern Song Dynasty and being densely populated, economically prosperous, and home to a thriving woodblock printing industry. Additionally, the imperial city housed numerous Buddhist monasteries, and its followers displayed high support for Buddhist endeavors (cf.

Bao 2014, p. 364;

Su 1962, p. 16;

Sun 2013, pp. 208–10). Given these favorable circumstances in both regions, the question arises: why was there a need for relocation?

With the available evidence being limited, it remains challenging to provide a definitive answer to the question at hand. However, it is worthwhile to delve into the contextual factors that Liaoqin and his team encountered. By examining the historical backdrop against which they operated, we can gain valuable insights that may shed light on their decision-making processes and the challenges they faced during the production of the canon.

Historical records shed light on some unfavorable factors that affected the development of Buddhism within the imperial city during the Southern Song Dynasty. Despite the thriving state of Buddhism and the presence of numerous temples within the city, instances of government officials and nobles encroaching upon monastery lands were recorded (

Sun 2010, pp. 78–80). Moreover, the densely populated city faced significant challenges due to high land and housing prices, as depicted by the poet Qingshun’s description of “every inch of land being as precious as gold” (城中寸土如寸金,

Xianchun Lin’an zhi, vol. 97, p. 4238). These high costs made it difficult to store the large number of wooden blocks required for the publication of scriptures. Furthermore, natural disasters, particularly frequent flooding, had a detrimental impact on the development of monasteries within Lin’an Prefecture (

Sun 2010, pp. 82–83).

However, one of the most significant challenges faced during the publication of the Canon was the constant risk of fire. Unfortunately, fires were a recurrent phenomenon in Lin’an Prefecture, particularly during the Southern Song Dynasty. The densely populated areas, widespread use of fire, active religious activities, and bustling night markets all contributed to frequent and severe fires in the city. Historical records indicate that nearly a hundred fire incidents occurred, causing extensive damage to the entire imperial city (

Xu 2016, pp. 263–300;

Tian 2017, pp. 12–34, 67–71). During the 14 years of Liaoqin’s project, the

Song Shi 宋史 (vol. 63, p. 1384) recorded four major fires. The most severe fire burned tens of thousands of households inside and outside the city.

The Monasteries in Lin’an during the Southern Song Dynasty had a large number of believers and frequent incense burning, which made them more susceptible to fires. Monasteries within the imperial city, such as Fan’tian Monastery 梵天寺, Chuanfa Monastery 傳法寺, Renwang Monastery 仁王寺, Linggan Guanyin Monastery 靈感觀音寺, as well as Monasteries outside the imperial city, such as Puji Monastery 普濟寺 and Nengren Chan Monastery 能仁禪寺, all experienced fires during that time (

Sun 2010, pp. 81–82). Since Liaoqin and others were fundraising in the capital city, they must have been aware of the risks involved in continuing the large-scale engraving project there.

The precise reason for the relocation of the

Qisha Canon carving project to Yansheng Monastery in Pingjiang Prefecture remains unclear. However, after this transition, Yansheng Monastery experienced a significant fire in the sixth year of the Baoyou era (1258). Thankfully, due to effective conservation measures, the carved wooden blocks of the canon were spared from the destructive flames.

21 6. Comprehensive Analysis of the Solicitation Process

The colophons of Liaoqin’s Section contain a wealth of information regarding fundraising, offering valuable insights into the extent of participation from different sectors of society during that period.

6.1. Donors: Profiles and Contributions

In the twelve volumes of Liaoqin’s Section, a total of 195 colophons were contributed by 178 individuals, presenting notable characteristics worth examining.

Firstly, it is observed that certain colophons mention the official titles of the donors, indicating the participation of government officials. For example, in Volume 1, there is a reference to Yu Ji 余稷, an eighth-rank official serving as Chengshi 承事, while Volume 12 includes the name of Tian Keda 田可大, a ninth-rank official, addressed as Zhongyilang 忠翊郎. Although the majority of the donors mentioned in the colophons were common people, the official ranks mentioned tended to be relatively low ranking.

Secondly, the analysis of colophons reveals the presence of Buddhists among the donors, including notable individuals such as Buddhist nun Fazhao 法照 and Buddhist disciple Gu Duan 顧端. However, the number of Buddhist donors remains relatively limited, totaling no more than 20 individuals. This observation suggests that Liaoqin’s Section had a constrained influence within the Buddhist community during that period.

22 Intriguingly, two donors mentioned in the colophons are likely Taoist practitioners, specifically Taoist Sun Fuchang from Zhugong 竹宮道士孫復常 and Madam Taoist 女道夫人. This indicates a relatively diverse target audience for the fundraising efforts.

Thirdly, several colophons indicate that the fundraising efforts were not directed towards individual donors but were the result of collective contributions. This is evident from the use of terms such as “collective merits” (zhongyuan 眾緣, muzhong 募眾) and “collective” (zhong 眾). For instance:

Volume 5: 九月十九日,執政府前大渠頭眾刊貳伯叁拾捌字。

On the nineteenth day of the ninth month, a group of individuals in Daqutou 大渠頭, in front of the Zhizheng fu 執政府 (the Governing Office), collectively donated to have two hundred and thirty-eight characters carved.

Volume 11: 紹定二年正月二十日眾緣刊壹伯字;二十一日弍伯字

On the twentieth day of the first month in the second year of Shaoding (1229), a group of individuals collectively donated to have one hundred characters engraved, and on the twenty-first day, a group of individuals donated to have two hundred characters carved.

Among the 190 colophons present in Liaoqin’s Section, only 14 of them provide a specific date, and interestingly, all of these date-specific colophons are associated with collective donations. Furthermore, these merged colophons often include details about the specific location. It appears that while individual donors could be identified by their titles or names, in the case of collective contributions, the only distinguishing factors available were the date and location. This aspect holds significance as it offers valuable insights into reconstructing the historical context surrounding the carvings.

Additionally, the donors’ wishes recorded in the colophons mainly focused on personal matters concerning themselves and their loved ones. These wishes often involved seeking healing for foot-related ailments, ensuring the well-being of their families, and promoting virtuous behavior. It is interesting to note the prevalent belief in astrology and the reverence for personal guardian stars during that time.

23 For instance:

Volume 12: 張宗賢刊伍伯字,祝獻戊戌本命并合宅本命元辰。

Zhang Zongxian 張宗賢 engraved five hundred characters, offering prayers to the personal guardian star of the Wuxu戊戌 year of birth and the house guardian star.

Volume 9: 吳山百法廣潤院比丘了信刊伍百字,功德祝献忠翊郎陳遵、楊氏、陳氏各人行年本命星君。

Monk Liaoxin of Baifa Guangrun Cloister 百法廣潤院 in Wushan吳山engraved five hundred characters, offering prayers for the personal guardian stars of Chen Zun 陳遵, who is the Zhongyi lang, as well as the Yang 楊 and Chen 陳 families, according to their respective birth years.

Indeed, the colophons in Liaoqin’s Section offer valuable insights into the diverse range of donors and their backgrounds, showcasing the active and collective participation from various sectors of society in supporting Liaoqin’s project. These records not only shed light on the individuals involved, including government officials, Buddhists, and even Taoist practitioners but also provide glimpses into the social and cultural context of the Southern Song Dynasty.

6.2. Magnitude of Donations: A Quantitative Analysis

Through an analysis of the colophons in the twelve volumes, it can be determined that a total of 42,755 characters and 38 pear-wood blocks were utilized for the engraving process after the collection of donations. Notably, among these colophons, two explicitly state the prices involved in the undertaking.

Volume 6: 楊和王府門下比丘尼法照同弟子曹道共捨伍貫文刊壹阡字,內壹貫文買梨板四片,功德保安身位,增延福壽。

The Buddhist nun Fazhao 法照, a hanger-on of Prince Yang of He 楊和王, together with her disciple Cao Dao 曹道, contributed five strings (guan 貫, a unit of 1000 coins) for the engraving of 1000 characters and one guan of the five for the purchase of four pear wood blocks to promote merit and ensure their well-being and longevity.

Volume 6: 餘杭縣貝村東保方宗敏捨壹貫文買梨板四片,追薦先考方三乙承事。

Fang Zongmin 方宗敏, who belongs to the eastern group of Beicun 貝村 in Yuhang County, donated one guan to buy four pear wood blocks to pray to the late father Fang Sanyi 方三乙, who served as Chengshi.

Based on these examples, it can be deduced that the price of one pear-wood block was approximately 0.25 guan, and the cost of engraving one character was approximately 0.004 guan. From these figures, the total amount of money raised through the colophons amounted to 180.52 guan. However, considering the prices during that time, this amount was not substantial, especially given the extensive duration of over ten years to collect it.

In comparison, in the first year of Jiaxi 嘉熙 (1237) in the Huzhou area, the production of a large pot and two large iron incense burners for the Nalin Baoguo Monastery 南林報國寺 was priced at 170 guan and 200 guan, respectively. Additionally, engraving the entire twelve volumes of Liaoqin’s Section would have required over 300 guan, while printing the 600 volume

Da banruo jing in the Nalin Baoguo Monastery cost only 300 guan.

24 This comparison highlights that the cost of printing was significantly lower than that of engraving, which may have contributed to the limited attractiveness of Liaoqin’s engraving project.

It is worth noting that out of the approximately 96,000 characters found in the twelve volumes, only around 43,000 characters were received through donations. This means that more than half of the characters have no associated donors. Furthermore, while Liaoqian himself donated 30 woodblocks for the first three volumes, and Volume 6 mentions that Bhikkhuni Fazhao and Fang Zongmin collectively purchased eight woodblocks, there are no other records of donated woodblocks. Rough estimations suggest that around 130 woodblocks would have been needed for the entire set of twelve volumes, indicating that nearly 70% of the woodblocks were acquired without explicit documentation of donors. This raises the possibility that a significant portion of the donations made towards the project were not documented in the colophons.

25The colophons also provide insights into the level of sponsorship. The most significant contributor was Zhang Yunyi 張雲翼 in Volume 11, a devoted Buddhist disciple who generously supported the carving of 2500 characters at a cost of 10 guan. Conversely, the smallest individual recorded contribution was merely 30 characters, amounting to 0.12 guan, made by Zhu Heng 朱亨 in Volume 5. This suggests that a minimum donation of 30 characters was required for an individual’s name to be recorded in the colophons. Contributions below this amount were probably considered part of the collective donations and recorded under the term “collective merits” (眾緣) mentioned above.

6.3. Overall Characteristics of the Fundraising Efforts

In summary, the fundraising efforts during Liaoqin’s Section of the

Qisha Canon were characterized by the active participation of ordinary individuals, low-ranking officials and monks from small monasteries. Comparisons with other engraving activities of

Qisha Canon in the Song Dynasty revealed similarities in terms of geographical concentration, with Liaoqin’s project primarily centered in Lin’an Prefecture, while other projects were focused on Pingjiang Prefecture and Jiaxing Prefecture.

26Additionally, Liaoqin’s Section reflects characteristics indicative of an early stage in the development of engraving projects. A notable distinction can be observed when comparing it to the time of Zhao Anguo, where the colophons frequently mentioned the engraving workroom for the

Qisha Canon, referred to as 磧砂延聖院經坊. In contrast, Liaoqin’s Section lacks specific indications of a fixed workplace dedicated to the engraving process. Furthermore, a well-organized structure is evident in the

Sixi Canon, which demonstrates specific roles such as engravers (雕經), supervisors (掌經), proofreaders (對經), verifiers (都對證), and fundraisers (勸緣).

27 However, the colophons of Liaoqin’s Section do not mention the existence of an organized workforce or delineate specific roles pertaining to the engraving process.

7. Conclusions

The Chinese Buddhist Canon is a comprehensive compilation of scriptures that has been engraved over an extensive historical period, exhibiting distinct characteristics across different sections. In this research, we direct our attention to the initial twelve volumes of the Qisha Canon, currently conserved in Japan, aiming to provide insights into the inception and progression of a Buddhist canon in the Great Hangzhou region.

The content and format of these twelve volumes of scriptures serve as vital elements for examination, distinguishing them as uniquely significant.

These volumes stand out not only within the Qisha Canon but also when compared to other existing engraved Buddhist canons. Notably, their typography, variants, and layout suggest that these early volumes originated from handwritten Buddhist canons of the Northern Song Dynasty. This inference highlights the convergence of written and engraved editions in the history of books. It is noteworthy that these scriptures were engraved despite the prevalence of well-established engraved canons, presenting a remarkable phenomenon of utilizing written editions as the basis for engraving.

The handwritten canons of the Northern Song Dynasty possess remarkable historical and cultural significance in terms of preserving Buddhist literature. Regrettably, only a limited number of incomplete and discontinuous volumes have survived over time. Therefore, the complete and uninterrupted preservation of the early section of the Qisha Canon, comprising the twelve volumes that originated from written canons, assumes exceptional importance. While it is commonly acknowledged that the production of canons in later periods may increase the probability of errors and printing mistakes, it is crucial to recognize that these later canons remain valuable to scholarly research. They may have effectively retained older textual sources, warranting further exploration in future studies on canon editions.

Moreover, the significance of the twelve volumes extends beyond their early Buddhist texts; they also provide valuable insights into the involvement of ordinary individuals in Buddhist activities. The colophons and local gazetteers shed light on the prominent role played by Monk Liaoqin, an enthusiastic advocate for public welfare, displaying exceptional skills in planning and management. Based on the available information, it can be inferred that the initial fundraising efforts for the publication of the Qisha Canon primarily took place in Liaoqin’s hometown, Deqing, in Huzhou, gradually extending to the neighboring villages. As fundraising activities progressed, the focus shifted towards the imperial city of Lin’an Prefecture from 1222 to 1229. However, for reasons unknown, the project was relocated to Pingjiang Prefecture the following year. This relocation reflects the challenges and uncertainties encountered during the early stages of the extensive Buddhist project.

Additionally, the engraving process of these twelve volumes of scriptures reveals the predominant involvement of local commoners as contributors, with relatively limited participation from Buddhist followers. The specific prices recorded in the colophons offer valuable insights into the financial requirements of undertaking a Buddhist project. For instance, the engraving of the entire twelve volumes of Liaoqin’s Section would have amounted to over 300 guan, which is equivalent to the cost of printing a 600 volume scripture.

In conclusion, this study has provided a comprehensive exploration of the early stages of engraving a substantial Buddhist canon, shedding light on its formative phase as a significant undertaking. Moreover, it has highlighted the unique integration of early carved editions and handwritten manuscripts within the Great Hangzhou region during the Southern Song Dynasty, presenting valuable insights and references for future research on Buddhist texts. The examination of the colophons, fundraising efforts, and the participation of various social groups has offered a nuanced understanding of the complexities surrounding the production of these twelve volumes of scriptures. This study contributes to the broader understanding of the historical development of Buddhist literature and the cultural dynamics of the time. Future investigations may build upon this research, further enriching our knowledge of the intricate interplay between carved and written editions in the evolution of Buddhist canons.