Abstract

The parable of the Prodigal Son in Luke 15 elicits profound responses and emotions in various times, places, and cultures. Why has it stood the test of time as one of Jesus’ most famous parables? One possible answer is that the story carries enduring appeal because of the underlying structure of the parable, a recurring pattern in literature called the monomyth. Peeling back the layers of the parable, one may uncover the foundational archetypes of the parable that make it timeless. Hidden significance of the parable may be illuminated by comparing its narrative to the hero quest of Joseph Campbell and the monomyth archetypes of Northrop Frye and Leland Ryken, both of which emphasize a cyclical movement that unifies all of literature. Also important are the specific archetypes within the general monomyth archetype, such as father and mother, bread and water. The parable also contains the four elements (mythoi) of the circular monomyth: romance, tragedy, anti-romance, and comedy. Using archetypal and myth criticism, this article demonstrates that the parable has enduring attraction because its underlying archetypes appeal to a deep layer of the human psyche and to what is elemental to the human experience.

Keywords:

Luke 15; Prodigal Son; parables; archetypes; monomyth; myth criticism; archetypal criticism; hero quest 1. Introduction: Archetypal Symbolism and Myth Criticism

The parable of the Prodigal Son told by Jesus1 and recorded in Luke 15:11–242 is considered by many to be Jesus’ most famous parable. The casual reader is often touched by the forgiveness and compassion the father bestows upon his returning son at the end of the story. However, many interpretations have failed to consider the powerful contributions underlying archetypes make to the impact of the story.3 Could it be that the story has maintained popularity throughout the centuries because of its use of a recurring archetypal pattern that unifies much of literature and unconsciously appeals to the reader? Without considering the entire cyclical movement of the Prodigal, and not just his return, one cannot feel the full psychological impact of the story. Mary Ann Tolbert comments that the Prodigal Son parable “must speak convincingly to some deep layer of the human psyche in order for it to have maintained its prominence in Christian tradition” (Tolbert 1979, p. 96). The purpose of this paper is to peel back the layers and attempt to uncover that deep layer through identifying underlying archetypes of the parable that give it its enduring appeal.4 When the Prodigal embarks on his quest for independence and happiness, he is actually unaware that his journey has a deeper meaning. Although the Prodigal is at first answering a pseudo-call of his own desire for happiness and independence, he will later discover the true call of the journey, which is to undergo an enlightening experience that will lead to his transformation and return. But first, he must be prepared and humbled through trials in order to understand the deeper call of his quest.

Before we begin the journey of the Prodigal, a few preliminary terms and concepts concerning archetypal symbolism and myth criticism must be discussed. Archetypal criticism is mainly a 20th century literary theory that has its roots in the works of Carl G. Jung (1875–1961) and J. G. Frazier’s The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion (12 vols., 1911–1915). Canadian literary critic Northrop Frye (1912–1991), however, should be credited with putting archetypal criticism “on the map” and was one of the first to use it as a literary criticism in his famous work, Anatomy of Criticism: Four Essays (1957).5 One of the first works to use archetypal criticism within biblical studies is Leland Ryken’s The Literature of the Bible (1974). Ryken, heavily influenced by Frye, authors his book under the assumption that “archetypal criticism is one of the most fruitful approaches to biblical literature” and “no introduction to biblical literature is complete without insisting on the archetypal content of the Bible” (Ryken 1974, p. 22). However, Ryken uses several other literary approaches in the book and does not specifically apply archetypal criticism to one single biblical example, leaving the door open for more work to be done. Archetypal criticism is often closely aligned with or even synonymous with myth criticism. Opinions differ as to whether myth criticism is the parent or child of archetypal criticism, but the key point is that the two cannot be separated from one another.

The goal of myth or archetypal criticism is to ask (or discover) why certain works of literature achieve enduring appeal or popularity and elicit common or characteristic responses from readers (Guerin et al. 2005, p. 182). In the words of Randolph Tate, “Archetypal critics are interested in explaining why some literary works perennially appeal to readers while others seem to be relegated to the literary dust bin” (Tate 2006, p. 24). An archetype is a symbol, character type, or plot motif that has recurred throughout literature and that carries the same (or similar) meanings for a significant portion of humankind (Ryken 1974, p. 22). Put more simply, archetypes “communicate meaning without explanation” (Tate 2006, p. 25). For Ryken, the overall archetypal pattern of literature is the monomyth. The monomyth and hero quest archetype was made famous by Joseph Campbell and his work, The Hero With a Thousand Faces. His title clearly states the thesis of his work, that there are thousands of hero stories, but they all follow the same basic structure: “Whether the hero be ridiculous or sublime, Greek or barbarian, gentile or Jew, his journey varies little in essential plan …. There will be found astonishingly little variation in the morphology of the adventure, the character roles involved, the victories gained” (Campbell 1968, p. 38).6

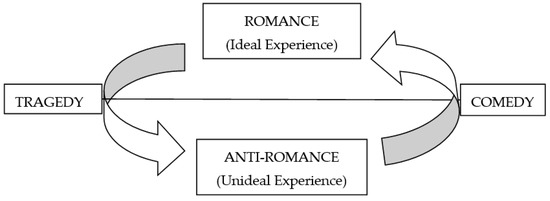

The Prodigal’s journey is considered a hero quest in this work, not because the prodigal is in fact a hero in the traditional sense, but because he follows the archetypal pattern of the person in a hero quest.7 Frye and Ryken also use the monomyth structure to interpret recurring patterns in literature. To them, there are four kinds of literary plots that together “form the circular monomyth that unifies all of literature” (Ryken 1974, p. 23). This “cyclical movement”, as Frye calls it, consists of “four pregeneric elements” called mythoi,8 which are romance, tragedy, anti-romance, and comedy (Figure 1).9 Thus, we end up with the following monomyth or cyclical movement:

Figure 1.

Frye’s mythoi monomyth.10

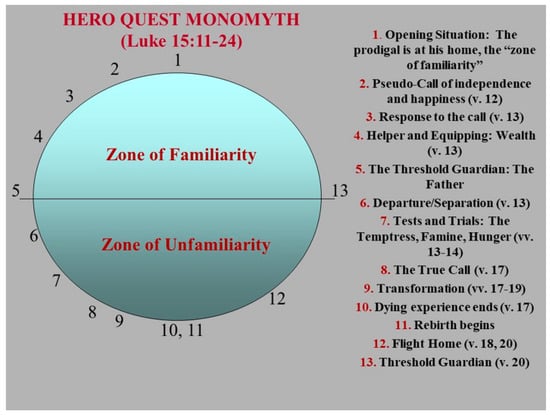

The wonder of the Prodigal Son parable is that it contains all four elements of the monomyth, completing the full cycle and thus adding to the powerful monomythic and archetypal appeal of the story.11 The parable’s foremost literary archetype is that of comedy, but the story also contains elements of romance, tragedy, and anti-romance. The monomyths of Campbell and Frye/Ryken form the foundation and overarching structure of this paper, or the “forest” of the paper. Within these main monomyth archetypes are individual archetypal images that represent the “trees” within the forest. Ryken lists archetypes of ideal experience, which normally take place in the top half of the monomyth (what Campbell calls the “zone of familiarity” (Figure 2)), and unideal experience, which normally take place in the lower half of the monomyth (what Campbell calls the “zone of unfamiliarity” (Figure 2)) (Ryken 1974, pp. 23–24). The goal of this paper is to examine the archetypes within the main monomyth archetypes of Campbell (Figure 2) and Frye/Ryken (Figure 1) and, by doing this, to posit that the parable of the Prodigal Son carries a powerful enduring appeal because of its underlying archetypal symbolism and overall cyclical movement pattern. Let the journey begin.

Figure 2.

Campbell’s hero quest monomyth.

2. Zone of Familiarity: The Period of Romance

The opening situation (#1)12 of the Prodigal’s journey takes place at his home, the “zone of familiarity”. The story begins in the top half of the mythoi monomyth in the area of romance or ideal experience.13 In v. 12, the Prodigal, who is the younger of two sons, says to his father, “Give me the share of the property that will belong to me.”14 This verse is the response (#3) of the Prodigal to the pseudo-call (#2) of his quest for independence. As Middle Eastern New Testament studies expert Kenneth E. Bailey explains, the son was not entitled to this inheritance until the death of the father (Bailey 1998, p. 35). The statement of the Prodigal implies that he is not content with his current living arrangement; in essence, the son is saying, “Father, I am eager for you to die” (Bailey 1998, p. 35). The Prodigal is being lured away by the thought that freedom from his father and securing his wealth now will result in independence and corresponding happiness. This mindset is congruent with the period of romance in a story, which is an “idealized picture of human experience. It satisfies our desire for wish fulfillment” (Ryken 1974, p. 23). The father shockingly consents to his son’s request (v. 12), fulfilling the role of what Frye calls the eiron character in a comedy who is the “man who deprecates himself … appearing to be less than one is” (Frye 1957, p. 40). And so, the quest begins for what the Prodigal believes to be happiness and independence found through wealth and freedom. However, the Prodigal is not aware that his quest is actually a response to a deeper call to undergo a necessary transformation that will help him see his need for dependence upon his family and social community. As Campbell says, “The psyche has many secrets in reserve” (Campbell 1968, p. 64). Describing this kind of call, he comments:

It cannot be described, quite, as an answer to any specific call. Rather, it is a deliberate, terrific refusal to respond to anything but the deepest, highest, richest answer to the as yet unknown demand of some waiting void within: a kind of total strike, or rejection of the offered terms of life, as a result of which some power of transformation carries the problem to a plane of new magnitudes, where it is suddenly and finally resolved.(Campbell 1968, pp. 64–65)

The Prodigal’s only helper and means of equipping his journey (#4) is the wealth he has impatiently demanded. Commentators agree that the Greek verb συναγαγὼν in v. 13 carries the idea of “converting everything” into cash (Fitzmyer 1985, p. 1087; Nolland 1993, p. 783).15 The only thing that can keep the Prodigal from his journey is his father, the threshold guardian (#5). The father poses a threat because he owns the right to refuse the Prodigal all he wants. As Bailey comments, “the father grants the inheritance and the right to sell” (Bailey 1998, p. 35). Here is the first example where the father acts the opposite of how a true archetypal father would, a foreshadow of things to come.16 The archetype of a father gives the story a startling element throughout because of the often anti-archetypal behavior of the father.17 Literary symbolist J. E. Cirlot says in his Dictionary of Symbols that the father “represents the world of moral commandments and prohibitions restraining the forces of the instincts and subversion” (Cirlot 1962, p. 102). The father is expected to refuse the right of passage to the son or at least put up a fight, but he does not.18 With the right of passage granted by his father, the son departs on a journey, εἰς χώραν μακράν, “to a distant country” (v. 13; #6) in a search to fill the “waiting void within”. We are not given the name of the χώραν μακράν, which is significant since the Prodigal is journeying into the “zone of unfamiliarity”, an unknown land.19

One of the reasons many people can relate so well to the story of the Prodigal is that a prodigal is a type of archetypal character (Ryken 1974, p. 311). As Hillyer Straton comments, “wandering sons are as universal as time” (Straton 1959, p. 75). As with the χώραν μακράν, neither the Prodigal nor the other people in the story are named, and the lack of particulars adds to the archetypal significance of each character. The word sometimes translated “prodigal” in v. 13 is ἀσώτως, which is literally the opposite of saving or keeping, meaning the Prodigal was a spendthrift.20 Stories and ideas about prodigals can be found throughout history.21 Similar stories to the one in Luke are found in Babylonian and Canaanite literature, in the Lotus Sutra, and in Greek papyri (Fitzmyer 1985, p. 1084). Epicurus associates prodigality with sensual pleasures, the inability to control or satisfy one’s desires, and a lack of peace (Holgate 1999, p. 146). Ancient Cynics were critical of prodigals for mistakenly chasing freedom through money and pleasure (Holgate 1999, p. 145). Through this archetype, the irony and the paradox of what the prodigal is after, namely freedom and happiness, become clear. Although the son is searching for freedom and independence, he will find himself unable to realize the freedom he is after and will lose his freedom through his search for it. Only after this realization will the Prodigal be able to hear the true call of his need for a personal transformation that will lead him back to his family.

Two other significant archetypes associated with prodigality are also found as the Prodigal enters the “zone of unfamiliarity”. In v. 30, the older son describes to his father the “reckless” living of the Prodigal as “devour[ing] your property with prostitutes”. This association of prodigality with joining oneself to prostitutes certainly fits the archetype presented above.22 The prostitutes represent the archetype of the temptress found throughout literature and hero quest stories (Campbell 1968, pp. 120–26). Her purpose is to destroy men by luring them away from completing their quest. Verse 13 states that the Prodigal “squandered his property” with wild living that apparently included prostitutes. The word βίος (“property”) here represents the land the Prodigal had sold and converted into cash, as explained earlier. As Nolland explains, βίος also means “‘life’, ‘manner of life’, ‘means of subsistence.’ The estate is what supports the life of the family” (Nolland 1993, p. 782). In a traditional Middle Eastern farming community, a farmer’s land was conjoined to his life (Bailey 2003, p. 150). Thus, the prostitute is symbolically taking the very life out of the Prodigal. This development marks the beginning of what literary critics describe as the typical “death and rebirth experiences” of the hero, where “their childish nature must die off, and their more mature … nature must be born” (Temple et al. 1998, p. 149). These “dying” experiences of the Prodigal will unexpectedly lead him to the moment of awakening, the true call of his quest.

3. Zone of Unfamiliarity: Tragedy and Anti-Romance

The Prodigal’s departure into a “distant country” and his immoral behavior mark the beginning of the tragedy portion of the story and the descent into the lower half of the monomyth. Frye comments that “the act which sets the tragic process going must be primarily a violation of moral law, whether human or divine” (Frye 1957, p. 210). Although the parable is mainly a comedy, a comedy can contain a potential tragedy within itself (Frye 1957, p. 215).23 The first half of the story accurately follows the archetype of a tragedy in that the character starts out “on top of the wheel of fortune” but exchanges “a fortune of unlimited freedom for the fate involved in the consequences of the act of exchange” (Frye 1957, p. 212).24 A tragedy often contains the paradoxical use of freedom to lose freedom, which is exactly what happens to the Prodigal. Campbell names this part of the story, where the hero descends into the lower half of the monomyth, “the belly of the whale”, when the hero “is swallowed into the unknown, and would appear to have died” (Campbell 1968, p. 90). But the dying must take place in order for the rebirth to begin.

At this part of the quest, the Prodigal encounters several more trials (#7) that carry heavy archetypal significance. Verse 14 reads, “When he had spent everything, a severe famine took place throughout that country, and he began to be in need.” To understand the full impact of what is taking place, it is important to note here that there is no mention of a mother in the story. The omission and absence of this common archetype is significant here in the story and especially later on. Joseph Campbell writes that when a common archetype is omitted, “it is bound to be somehow or other implied—and the omission itself can speak volumes” (Campbell 1968, p. 38). The mother archetype is “associated with the life principle, birth, warmth, nourishment, protection, fertility, growth, abundance” (Guerin et al. 2005, p. 152). But in the story of the Prodigal, a “severe famine” comes on the land, so there is no life, growth, or abundance of which to speak. A famine also attests to a lack of water in the land, important because water, as “the mother of all life”, is symbolic of fertility and growth and carries maternal significance (Guerin et al. 2005, p. 150). Thus, the lack of water symbolizes the lack of the maternal care that the Prodigal needs. The famine further carries archetypal meaning in its connotation of barrenness and desert, both of which Ryken lists as archetypes of unideal experience and which also represent death and hopelessness (Guerin et al. 2005, p. 153). This hopeless state is the condition of the Prodigal as the “dying off” of his nature continues to take place.

As the Prodigal sees his original plan for happiness and independence disappearing, he encounters another test and trial (#7), finding himself in need of the basic necessities in life such as food. The failure of the Prodigal’s quest for independence is made apparent in the phrase “he began to be in need” (v. 14). Instead of finding independence and its resultant happiness, the Prodigal has become a man in great need. The total loss of freedom and independence is symbolized in that the Prodigal “hired himself out to a citizen of that country, and he sent him into his fields to feed swine” (v. 15).25 The condition of the Prodigal is summed up through the archetype of the pig, “a symbol of uncleanness, stupidity, sensuality, and/or greed” (Ferber 1999, p. 154), and an image especially offensive and degrading to Jews (Leviticus 11:7). Here, the Prodigal is associated with the pigs and in fact envies them, for “he would have gladly filled himself with the pods that the pigs were eating” (v. 16). The Prodigal’s sensuality and greed is what placed him into his desperate situation. He has reached the lowest and final point of his “death” experience, the point of anti-romance in the story, defined as “a world of complete bondage and the absence of anything ideal” (Ryken 1974, p. 23). But the story does not end here; it is time for the rebirth and the comedy to begin.

4. Comedy: The Transformation Begins

After many trials and the archetypal pattern of the dying of the “childish nature” (Temple et al. 1998, p. 149), the Prodigal is now prepared to hear the true call (#8) and experience the personal transformation (#9) that will change him forever. Verse 17 says, “But when he came to himself he said, ‘How many of my father’s hired hands have bread enough and to spare, but here I am dying of hunger!’” The key phrase here is εἰς ἑαυτὸν δὲ ἐλθὼν (“he came to himself”), which “signals a measure of self-knowledge—a moment of realism” (Byrne 2000, p. 129). The implication is that the Prodigal now understands the true call of his quest: a transformation of self, a “coming of age”. As Campbell says of this kind of call, “it may mark the dawn of religious illumination … what has been termed ‘the awakening of the self’” (Campbell 1968, p. 51). This awakening also marks the end of the tragedy portion of the story, which often contains a discovery and recognition by the hero of what has been lost and forsaken through his actions and choices (Frye 1957, p. 212). The Prodigal has come to realize that, despite all his pursuits and “prodigal” living, none of it has brought him what he desires. In fact, he has found himself in want and enslaved to his desires. Campbell remarks, “What formerly was meaningful may become strangely emptied of value” (Campbell 1968, p. 55).26 The Prodigal has literally and symbolically come to the point of death: “I am dying here with hunger.”

A comedy is defined as a story with “an upward movement from bondage to freedom” (Ryken 1974, p. 23). The evidence of the Prodigal’s transformation is in the exclamation, “How many of my father’s hired hands have bread enough and to spare” (v. 17), and in v. 19 where he plans to say to his father, “treat me like one of your hired hands”. The Prodigal has been humbled by his experiences and decides that he will be content simply to have enough bread and to be a hired servant of his father. According to Holgate, “the teaching that want can be avoided by escaping the slavery of desire, and by learning to meet only one’s legitimate needs, is found in Cynic, Stoic and Christian texts” (Holgate 1999, p. 151). In v. 17, the Prodigal mentions his desire simply to have enough bread as his father’s hired servants do. The bread has definite archetypal significance, symbolically closing out the dying experience (#10) while beginning the idea of rebirth (#11). In mentioning bread, the Prodigal is expressing that he will now be content with the simplest of things, for bread “is the fundamental foodstuff of humans …. Bread is the ‘staff’ of life … [it is] plain fare, the food of the common people” (Ferber 1999, p. 35). Ryken lists food staples such as bread as an archetype of ideal experience. As the literary symbolist Ferber exclaims, “To be alive is to eat bread” (Ferber 1999, p. 35). The archetype of bread explains that the Prodigal longs to come to life, or we could say he longs to come “full circle” back to the place of ideal experience or romance.

With the Prodigal’s transformation complete, it is time for the flight home (#12). Verse 18 begins, “I will get up and go to my Father.” Nolland notes that the Greek verbs “mark the beginning of the son’s decisive change of direction” (Nolland 1993, p. 784). But before the son can come back home into the zone of familiarity and ideal experience, he must again cross the threshold guardian of the father (#13). At this point, the Prodigal is “still far off” (v. 20) in the zone of unfamiliarity and in the anti-romance land of the unknown.27 Once again, the reaction of the father is unexpected: “But while he was still far off, his father saw him and was filled with compassion; he ran and put his arms around him and kissed him” (v. 20). The surprising behavior of the father is fully understood after one realizes how anti-archetypal the father’s actions are. The father, a symbol that “stands for the force of tradition” (Cirlot 1962, p. 102), acts anything but traditionally here. The father would be expected to sit and wait and see what the rebellious son might have to say for himself (Bailey 1998, p. 38). Instead, he comes running to him, an act contrary to expectations of the culture and which would have in fact been “deeply humiliating” (Bailey 1998, p. 38). The father is the one who brings the son back into the realm of ideal experience. Just as the father did not put up a fight when the Prodigal moves downward across the threshold, likewise he does not resist the Prodigal’s upward movement back across the threshold. Once again, the father fits the eiron character type in a comedy who “is a character, generally an older man, who begins the action of the play by withdrawing from it, and ends the play by returning” (Frye 1957, p. 174). However, the father’s anti-archetypal behavior is also felt in that the eiron character “is often a father with the motive of seeing what his son will do” (Frye 1957, p. 174). Here, the father is proactive instead of the expected reactive to what the son might do.

As discussed above, several archetypes in the Prodigal’s quest represent a lack of and need for maternal care, and this understanding adds substantial revelation to the father’s actions here. Cirlot describes the archetypal father as “closely linked with the symbolism of the masculine principle” (Cirlot 1962, p. 102). But here, the father is found “demonstrating the tender compassion of a mother” (Bailey 1998, p. 38). Bailey comments elsewhere, “The mother is permitted, and even expected, to run down the road and shower the dear boy with kisses”, but certainly not the father (Bailey 2003, p. 146; cf. Tobit 11:9). At times in Scripture, God is described like or as a mother (Isa 66:13; 49:15; Deut 32:18; Ps 131:2). The mother archetype is one of life and birth, but here, it is the father who welcomes back the son and gives him new life. Giving the father both maternal and paternal tendencies enhances the archetypal understanding of the story, but it also fits the context of Luke 15. Jesus is the good shepherd, the good woman, and then the father who shows both paternal and maternal tendencies. Thus, Luke 15 is a well-balanced parable that promotes both the masculine and feminine characteristics of the Divine. This maternal behavior of the Father and the maternal theme in the parable are recognized by some as “an undertow” of the Prodigal Son parable (Scott 1990, pp. 115–16, 122) and are felt more powerfully when understanding archetypal symbols (or lack of such, as with water) in the parable. The need for maternal care is evident through several archetypes in the story, and this need is met at this point in the story as the Prodigal completes his rebirth experience.28

5. Completion of the Cyclical Movement: Return to the Zone of Familiarity and the Period of Romance

In v. 21, the Prodigal shows his maturation and transformation to his father in a speech. But despite the willingness of the son to become a servant, the father instead calls for “the best robe”, “a ring”, “sandals”, and “the fatted calf” (vv. 22–23). All four archetypal items add to the completion of the quest and finish out the death-and-rebirth archetype. The robe, ring, and sandals are signs of honor, authority, and a free man, respectively (Evans 1990, p. 237). The ring “like every closed circle is a symbol of continuity and wholeness” (Cirlot 1962, p. 273). Ryken lists the feast, meal, supper, or meat all as archetypes of ideal experience.29 Thus, the archetypes tell the reader that the hero has completed his journey and come full circle back to the place of romance and ideal experience where he started.

The father describes in v. 24 his reason for the elaborate measures taken: “For this son of mine was dead and has come to life again; he was lost and has been found.” The father confirms that the death-and-rebirth cycle has been completed and that the son has been fully welcomed back into the family. The Prodigal represents a principal element in the return of an archetypal hero in that he comes back changed and transformed (Temple et al. 1998, p. 149). A typical hero archetype normally contains what Campbell calls “the nuclear unit of the monomyth”, which is the “rites of passage” of separation, initiation, and return (Campbell 1968, p. 30). In an initiation, “the hero undergoes a series of excruciating ordeals in passing from ignorance and immaturity to social and spiritual adulthood, that is, in achieving maturity and becoming a full-fledged member of his or her social group. The initiation most commonly consists of three distinct phases: (1) separation, (2) transformation, and (3) return” (Guerin et al. 2005, p. 190). The Prodigal has completed all three phases or rites of passage. That we are not told much about the Prodigal at the end fits the typical comedy, in which “the character of the successful hero is so often left undeveloped: his real life begins at the end” (Frye 1957, p. 169).

6. Conclusions

Although the Prodigal must endure many tests and trials, he eventually discovers the true call of his quest and undergoes the necessary transformation before he returns home. To simply examine only the return of the Prodigal is not sufficient to fully understand why the story carries such strong psychological responses that transcend time and cultures. Frye says that we often must “stand back” from a piece of literature to see its archetypal organization (Frye 1957, p. 140). My goal in this article has been to show why the parable of the Prodigal Son has such powerful enduring appeal across time and cultures by “standing back” to see the underlying cyclical movement of the story, as well as by peering in to see the particular archetypes in the story. I have offered an analytical explanation of the sometimes unconscious or naïve responses that take place within the reader of the parable. The archetypal significance of the story is at least one of the reasons the parable is and will always be a “universal parable” (Bailey 2003, p. 160).

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable. No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | This paper assumes that the parable of the Prodigal Son originated with Jesus. Many theories exist as to from whom the parable comes. I prefer the conclusion of Carlston, who says that “the parable originated in substantially its present form with Jesus” (Carlston 1975, p. 368). He bases his conclusion on linguistic data and theological analysis. Lukan vocabulary and expressions are lacking in the parable, and a distinctive Lukan emphasis—an ethical definition of repentance—is missing. Furthermore, the teaching of the parable (especially vv. 25–32) seems to reflect a real conflict between Jesus and the Pharisees and the scribes, who were διεγόγγυζον (“complaining”) that Jesus ἁμαρτωλοὺς προσδέχεται (“welcomes sinners”, 15:2; all translations of Greek words or phrases throughout this work are my own). |

| 2 | I have chosen to include only vv. 11–24 for my analysis, despite the fact that the parable runs through v. 32. My reason for this is my emphasis upon the story as an archetypal cyclical hero quest. The hero quest ends nicely at v. 24 in a “happily ever after” kind of fashion, and vv. 25–32 act as an addition to the quest, although they also contain interesting archetypes that could be analyzed. Some scholars argue that the parable originally consisted of only vv. 11–24 (Sanders 1968–1969, pp. 433–38). Although I do not agree with Sanders (see footnote above), his position does support my opinion that vv. 11–24 are able to stand on their own as a complete hero quest. I am in no way minimizing the importance of vv. 25–32 in the parable; they are very important in light of the context (v. 2). It should also be noted that the Prodigal Son parable is really part of a larger parable. Verse 3 says εἶπεν δὲ πρὸς αὐτοὺς τὴν παραβολὴν ταύτην (“so he told to them this parable” [emphasis mine]). The demonstrative pronoun ταύτην is singular and therefore unifies the three stories of Luke 15 into one parable. In this paper, however, when I refer to the parable, I am only speaking of the parable of the Prodigal Son. |

| 3 | The parable’s reputation as one of Jesus’ most famous parables and its apparent ability to elicit profound emotions or responses regardless of time, place, and culture are the main reasons I began inquiring into the parable’s archetypal symbolism. |

| 4 | Archetypes are certainly not the only reason the parable has enduring appeal, and in no sense do I claim to offer the interpretation, but hopefully my work will result in both scholars and laypeople alike accepting that archetypal significance is at least one of the reasons. Many other interpretations of the parable have been offered. Tolbert uses psychoanalytic dream interpretation (Tolbert 1979); Daniel Patte applies structural analysis (Patte 1976); and Bailey adopts a literary cultural approach (Bailey 1976). For a wonderful summary and sampling of works on the Prodigal Son parable, see Leland Ryken’s compilation, The New Testament in Literary Criticism, where he offers excerpts from nine different works of interpretation on the parable of the Prodigal Son (Ryken 1984, pp. 285–94). For essays on the parable using historical-critical, literary, psychoanalytic, sociological, and other approaches, see Antoine et al. (1978). |

| 5 | Archetypal criticism is often separated into two disciplines, psychology (Jung) and cultural anthropology (Frazier). The psychological side appeals mostly to Jung and is often called “archetypal psychology”. The first systematic application of Jung to literature is Bodkin’s Archetypal Patterns in Poetry: Psychological Studies of Imagination (Bodkin 1934). Frye interpretes archetypes solely as literary occurences and purposely separates himself from Jung and Jungian critics, as well as from anthropology, psychology, and any “collective unconscious” (see Frye 1957, pp. 111–12; cf. 97). Robert Alter critiques some of the weaknesses of Frye’s sytem (Alter 2002, pp. 14–15). My analysis will find the most affinity with Frye, Ryken, and Joseph Campbell. This paper is not a Jungian approach to the parable of the Prodigal Son but may include some of his approach. As with any biblical criticism, the critic can easily become overzealous in his or her application. When applying archetypal criticism, one should be aware that images do not necessarily function as archetypes every time they appear in a literary work. Also, some archetypes may be mistaken as universal despite being culturally specific. The literary critic should not “try to open all literary doors with this single key” (Guerin et al. 2005, p. 219), and the reader should still pay attention to the historical context in which the archetypes occur (Ruthven 1976, p. 77). By making room for anti-archetypes and by incorporating important historical and contextual aspects of the parable, I have tried to address these and other concerns and to save the individuals and aesthetics of the story from disappearing in a fog of archetypes. |

| 6 | Campbell’s book neatly fits K. K. Ruthven’s definition of myth-criticism: “the aim of myth-criticism is to establish a system of reductive monism for the reintegration of the Many in the One” (Ruthven 1976, p. 75). |

| 7 | One glaring omission in the Prodigal’s quest compared to most hero journeys is the absence of a specific boon, which, when captured, is brought back to benefit the community that the hero left. However, this does not take away from the obvious cyclical pattern the Prodigal travels, which mimics closely that of the hero quest monomyth. In addition, the Prodigal’s boon could be said to be more metaphysical; that is, his main contribution that he will bring back is a transformed and enlightened individual. |

| 8 | To my knowledge, Frye does not use the word monomyth, but this seems to be what he has in mind. He refers to the pattern as a cycle, often citing the “top half”, “downward movement”, “lower half”, and “upward movement” (Frye 1957, p. 162). |

| 9 | Anti-romance is what Ryken labels the lower half of the chart. Frye uses irony and satire as his label for the lower half of the cycle, where ironic myth “is best approached as a parody of romance” (Frye 1957, p. 223). They are both speaking of mainly the same thing. I use the term anti-romance in this article. Frye corresponds each mythoi to a season: summer (romance), autumn (tragedy), winter (anti-romance), and spring (comedy). |

| 10 | Although this figure illustration is my own, a similar illustration is found in Ryken (1974, p. 23). In order to avoid confusion from referring to Campbell’s monomyth, I will refer to Frye’s pattern (Figure 1) as the mythoi monomyth. |

| 11 | It should be noted that neither Frye nor Ryken attempt to treat a work of literature as possessing all four elements. Frye discusses each element in separate sections, giving examples of each. This literary monomyth unifies all of literature, but all four elements are not found in every piece of literature. Frye spends most of his essay discussing his mythoi in relation to drama, for they are “most easily studied in drama, but”, he says, “not confined to drama” (Frye 1957, p. 207; cf. 95). |

| 12 | The hero quest and cyclical movement of the Prodigal is numbered and labeled on the monomyth diagram in Figure 2. As the steps of the journey are explained throughout the article, they will be labeled in parentheses, as is done after the “opening situation” above. A monomyth diagram showing the steps of a hero’s journey does not appear in Campbell’s work, but diagrams have been created in subsequent commentaries on Campbell’s work that highlight some of the essential elements of a hero quest. I am indebted to Dr. Nathan Nelson for supplying me with a generic monomyth diagram outlining the steps of a hero’s journey. Dr. Nelson’s work and area of interest in this subject has proven very helpful to me in writing this article. |

| 13 | One reason to assume this is a period of romance where “all is well” is that this apparently is a wealthy family. From later verses in the parable, we can assume that the family has a herd of fatted calves and goats, house servants, a banquet hall, and the ability to hire musicians and dancers. Some may criticize the idea of a “zone of familiarity” or an area of ideal experience as ethnocentric ideas. However, the focus of the analysis of this article is the transformation the Prodigal must undergo in order to complete his quest, not the idea that one place is better than another. |

| 14 | The request is even more shocking in the Greek. The Prodigal demands the property by using the imperative δός. Unless otherwise noted, all scripture quotations are from the NRSV translation. |

| 15 | Indeed, the NEB translates the word “turned into cash”. |

| 16 | Bailey comments that there are five times in the parable the father does not behave like a traditional oriental patriarch (Bailey 1998, p. 35). However, the father does continue to fulfill the role of the eiron character here. |

| 17 | Some may question the validity of including anti-archetypes in an archetypal analysis. Anti-archetypes are responsible for eliciting powerful responses in the same way normal archetypes do. Because “expanding images into conventional archetypes of literature is a process that takes place unconsciously in all our reading” (Frye 1957, p. 100), the reader is jarred when something unconventional takes place. But without the idea of conventional archetypes, there could be no such thing as anti-archetypes. Therefore, they are important to consider in an archetypal analysis. Campbell says that when a basic element of the archetypal pattern is missing, “the omission itself can speak volumes” (Campbell 1968, p. 38). Looking for missing or anti-archetypes is no different than a feminist critic looking for places where a woman is not mentioned in a story but perhaps should be. No one would accuse him or her of not doing feminist criticism when that kind of approach is taken. |

| 18 | Since I am interpreting the parable mainly as a comedy, it is important to note that Frye says that, in a comedy, “the obstacles [to the hero] are usually parental, hence comedy often turns on a clash between a son’s and a father’s will” where the father is usually “the opponent of the hero’s wishes” (Frye 1957, p. 164). Here, again, is more evidence that the father’s behavior is anti-archetypal. |

| 19 | This imagery is felt several times throughout the story. The Prodigal will later hire himself out to a citizen of χώρας ἐκείνης (“that country”, v. 15), where he says, ἐγὼ λιμῷ ὧδε (“I am dying here,” v. 17, emphasis mine). There is a definite separation and dichotomy between the zone of familiarity or ideal experience and the zone of unfamiliarity or unideal experience. See Campbell’s idea of the “belly of the whale” mentioned later, as well as the discussion of v. 20 where the Prodigal must again cross the threshold, this time back into the zone of familiarity. |

| 20 | The word is an alpha privative, with the prefixed alpha being joined to the word σώζω (“to save, keep”). The word is probably best understood in this way in light of the previous use of συναγαγὼν and especially when considering that, in the Greek text, the very next word is δαπανήσαντος, which carries the idea of spending or wasting all that one has and which holds the connotation of wastefulness (Bauer 1979, p. 171, “δαπαναω”). The word has been translated as “loose” (NASB), “wild” (NIV), “riotous” (KJV), “dissolute” (NRSV), “reckless” (NEB, TEV), and “prodigal” (NKJV). |

| 21 | For examples of patterns of prodigality in more modern literature and drama see Helgerson (1976); Leah (1992). |

| 22 | The Living Bible seems to have picked up on this association and translates v. 13 as “wasted all his money on parties and prostitutes”. I am not presenting the Living Bible as an accurate or scholarly translation (it is neither) but only pointing out the apparent response and connection the archetype of prodigality elicits with sexual behavior. |

| 23 | Frye also goes on to say that Christianity “sees tragedy as an episode in the divine comedy, the larger scheme of redemption …. The sense of tragedy as a prelude to comedy seems almost inseparable from anything explicitly Christian” (p. 215). He comments that to reverse the procedure—to have a comedy as a prelude to a tragedy—is “almost impossible” (p. 215). Campbell also sees the intertwining of tragedy and comedy: “The two are the terms of a single mythological theme and experience which includes them both and which they bound: the down-going and the up-coming (kathodos and anodos), which together constitute the totality of the revelation that is life” (Campbell 1968, p. 28). Guerin comments that hero archetypes are often “archetypes of transformation and redemption” (Guerin et al. 2005, p. 190). |

| 24 | This part of the parable would more specifically be a tragedy of innocence, “usually involving young people”, in which the youthful life must be “cut off” and innocence is lost (Frye 1957, p. 220). |

| 25 | Harrill argues that the word ἐκολλήθη (“hired himself out”) represents the Greek custom of a paramone contract or clause, which bound an agent to remain with a patron and to work in general service for a specified length of time and to do whatever services were ordered. Paramone clauses were more binding, and Harrill prefers to translate the verse “he was indentured to one of the citizens of that country”. Harrill comments that “the degradation of the task eventually received [by the Prodigal] demonstrates the youth’s obligation to do anything” (Harrill 1996, p. 715). He concludes: “The parable thus portrays the economic position of the son as extremely low in order to heighten the drama of the acceptance by the father” (717). The situation also heightens the feeling of anti-romance or unideal experience at this point in the story. Ryken lists slavery and bondage as archetypes of unideal experience, and based on Harrill’s understanding of ἐκολλήθη, the Prodigal’s condition seems to be close to slavery. |

| 26 | The interpretation in the above paragraph marking the “awakening of the self” of the Prodigal may at first sound debatable or problematic to those doing a theological analysis of the passage (which I am not) and who interpret it in light of the larger context of the three parables in Luke 15. I am not inferring that the Prodigal repents at this point, only that he recognizes that his plan for independence has failed, and he now hears a true call to something deeper. Bailey believes that interpreting vv. 17–19 as repentance breaks up the theological unity of the chapter (see Bailey 1998, p. 37). The debate centers on the idiom εἰς ἑαυτὸν ἐρχεσθαὶ, which is found in extrabiblical Greek and carries the idea of coming to one’s senses (Nolland 1993, p. 783). Some interpreters, however, see the idiom as representing a Semitic phrase that means “to repent” (Marshall 1978, p. 609). Following the hero quest pattern allows for a balanced interpretation that leaves room for both repentance and awakening but mostly falls in the middle somewhere. The Prodigal is unsure of what he must do, but he knows there is a deeper call within that he must answer. |

| 27 | The English translation does not fully bring out the imagery of separation between the son and the father. The Greek says ἔτι δὲ αὐτοῦ μακρὰν ἀπέχοντος (“while he was still far away and distant”). The two Greek words used together add emphasis to the separation. The searching of the father fits the context of the other two parables of Luke 15, where the focus is on the shepherd and the woman who search out what is lost. See previous footnote discussing vv. 17–19. |

| 28 | The absence of a mother in the story and the maternal behavior of the father have been interpreted both positively and negatively by feminist critics. For a brief discussion of that, as well as understanding God as mother, see Dutko (2023, pp. 230–35). |

| 29 | Ryken also lists musical harmony and singing as archetypes of ideal experience. In v. 25, the elder son “heard music and dancing” apparently taking place at the celebration for the found younger son. These archetypes may also add to the feeling of ideal experience and romance at the end of the quest. |

References

- Alter, Robert. 2002. Northrop Frye Between Archetype and Typology. Semeia 89: 9–21. [Google Scholar]

- Antoine, Gerald, Louis Beirnaert, Francois Bovon, Jacques Leenhardt, Paul Ricoeur, Gregoire Rouiller, Philibert Secretan, Christophe Senft, and Yves Tissot. 1978. Exegesis: Problems of Method and Exercises in Reading (Genesis 22 and Luke 15). Translated by Donald G. Miller. Pittsburgh Theological Monograph Series 21; Eugene: Pickwick. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, Kenneth E. 1976. Poet and Peasant: A Literary Cultural Approach to the Parables in Luke. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, Kenneth E. 1998. The Pursuing Father: What we need to know about this often misunderstood Middle Eastern parable. Christianity Today 42: 34–40. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, Kenneth E. 2003. Jacob & the Prodigal: How Jesus Retold Israel’s Story. Downers Grove: InterVarsity. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, Walter. 1979. A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature. Translated by William F. Arndt, and F. Wilbur Gingrich. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bodkin, Maud. 1934. Archetypal Patterns in Poetry: Psychological Studies of Imagination. London: Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, Brendan. 2000. The Hospitality of God: A Reading of Luke’s Gospel. Collegeville: Liturgical. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Joseph. 1968. The Hero With a Thousand Faces, 2nd ed. Princeton: Pantheon Books. [Google Scholar]

- Carlston, Charles. 1975. Reminiscence and Redaction in Luke 15:11–32. Journal of Biblical Literature 94: 368–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirlot, Juan Eduardo. 1962. Dictionary of Symbols. Translated by Jack Sage. New York: Philosophical Library. [Google Scholar]

- Dutko, Joseph Lee. 2023. The Pentecostal Gender Paradox: Eschatology and the Search for Equality. London: Bloomsbury T&T Clark. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, Craig. 1990. Luke. New International Biblical Commentary 3. Peabody: Hendrickson. [Google Scholar]

- Ferber, Michael. 1999. A Dictionary of Literary Symbols. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzmyer, Joseph. 1985. The Gospel According to Luke. 2 vols. Anchor Bible 28–28A. Garden City: Doubleday. [Google Scholar]

- Frye, Northrop. 1957. Anatomy of Criticism: Four Essays. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Guerin, Wilfred L., Earle Labor, Lee Morgan, Jeanne C. Reesman, and John R. Willingham, eds. 2005. A Handbook of Critical Approaches to Literature, 5th ed. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harrill, Albert. 1996. The Indentured Labor of the Prodigal Son (Luke 15:15). Journal of Biblical Literature 115: 714–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helgerson, Richard. 1976. The Elizabethan Prodigals. Berkeley: University of California. [Google Scholar]

- Holgate, David A. 1999. Prodigality, Liberality and Meanness in the Parable of the Prodigal Son: A Greco-Roman Perspective on Luke 15.11–32. Sheffield: Rhodes University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Leah, Hadomi. 1992. The Homecoming Theme in Modern Drama: The Return of the Prodigal: “Guilt to be on Your Side”. Lampeter: Edwin Mellen. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, I. Howard. 1978. The Gospel of Luke: A Commentary on the Greek Text. New International Greek Testament Commentary. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [Google Scholar]

- Nolland, John. 1993. Luke. 3 vols. Word Biblical Commentary 35A–35C. Dallas: Word Books. [Google Scholar]

- Patte, Daniel. 1976. Structural Analysis of the Parable of the Prodigal Son: Toward a Method. In Semiology and Parables: Exploration of the Possibilities Offered by Structuralism for Exegesis. Pittsburgh Theological Monograph Series 9; Edited by Daniel Patte. Eugene: Pickwick, pp. 71–150. [Google Scholar]

- Ruthven, K. K. 1976. Myth. The Critical Idiom 31. London: Methuen & Co., Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Ryken, Leland. 1974. The Literature of the Bible. Grand Rapids: Zondervan. [Google Scholar]

- Ryken, Leland. 1984. The New Testament in Literary Criticism. New York: Frederick Ungar. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, Jack T. 1968–1969. Tradition and Redaction in Lk. xv. 11–32. New Testament Studies 15: 433–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, Bernard Brandon. 1990. Hear Then the Parable. Minneapolis: Fortress. [Google Scholar]

- Straton, Hillyer. 1959. A Guide to the Parables of Jesus. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [Google Scholar]

- Tate, W. Randolph. 2006. Interpreting the Bible: A Handbook of Terms and Methods. Peabody: Hendrickson. [Google Scholar]

- Temple, Charles A., Miriam G. Martinez, Junko Yokota, and Alice Naylor. 1998. Children’s Books in Children’s Hands: An Introduction to Their Literature. Boston: Allyn & Bacon. [Google Scholar]

- Tolbert, Mary Ann. 1979. Perspectives on the Parables: An Approach to Multiple Interpretations. Philadelphia: Fortress. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).