We will now present the main results according to the selected dimensions of analysis, which are as follows:

3.1. Contextualization: The Importance of Religion within Different Aspects of Life

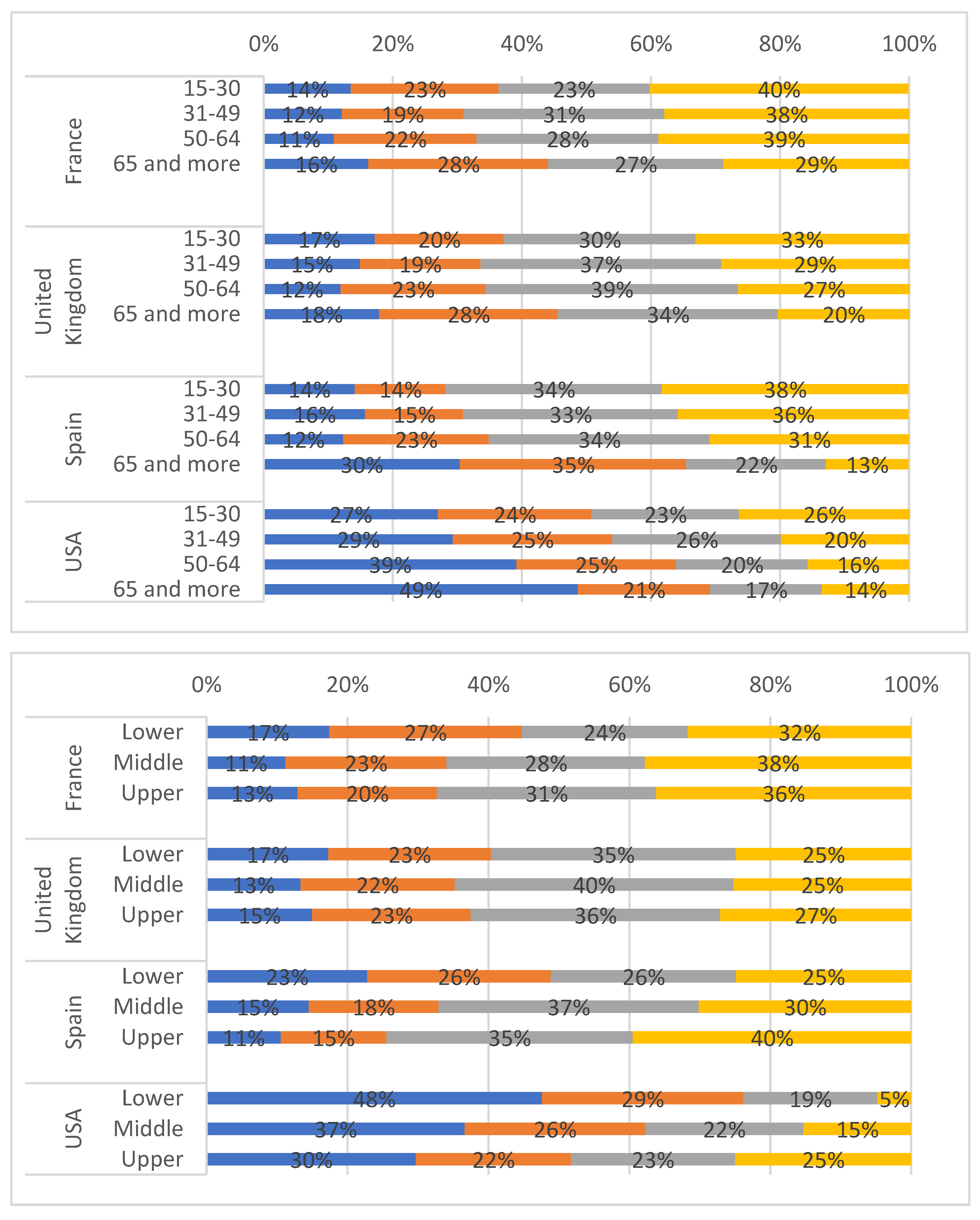

Figure 1 presents the consideration of the residents of the countries under study with respect to six aspects of life, with the possibility of answering ‘very important, ‘rather’, ‘not very’, or ‘not at all important’. Family is ‘very important’ for nine out of ten respondents, being the aspect that reaches the highest degree of importance: Nine out of ten define it as ‘very important’.

Considering only the ‘very important’ response, work and friends are the next aspects in order of importance, answers chosen by slightly more than half of the respondents (54% and 53%, respectively). However, when this response and the next one (‘rather’) are considered together, leisure time comes in second place (42 ‘very’ +47 ‘rather’), followed by friends and work. In both of these, approximately 80% of respondents consider them important, although—as noted—work and friends show higher choices of the most important response.

Focusing attention on the last two aspects of importance, located on the right-hand side of

Figure 1, the situation changes considerably. Starting with politics, 49% of respondents consider it as ‘important’ in their life when the ‘very’ and ‘rather important’ responses are added together; although the ‘very important’ response is the lowest of all those considered.

Furthermore, 57% (29% + 28%) of respondents do NOT consider religion important in their lives, and only one in five consider it to be very important. This is, in short, the least valued aspect of the six aspects considered.

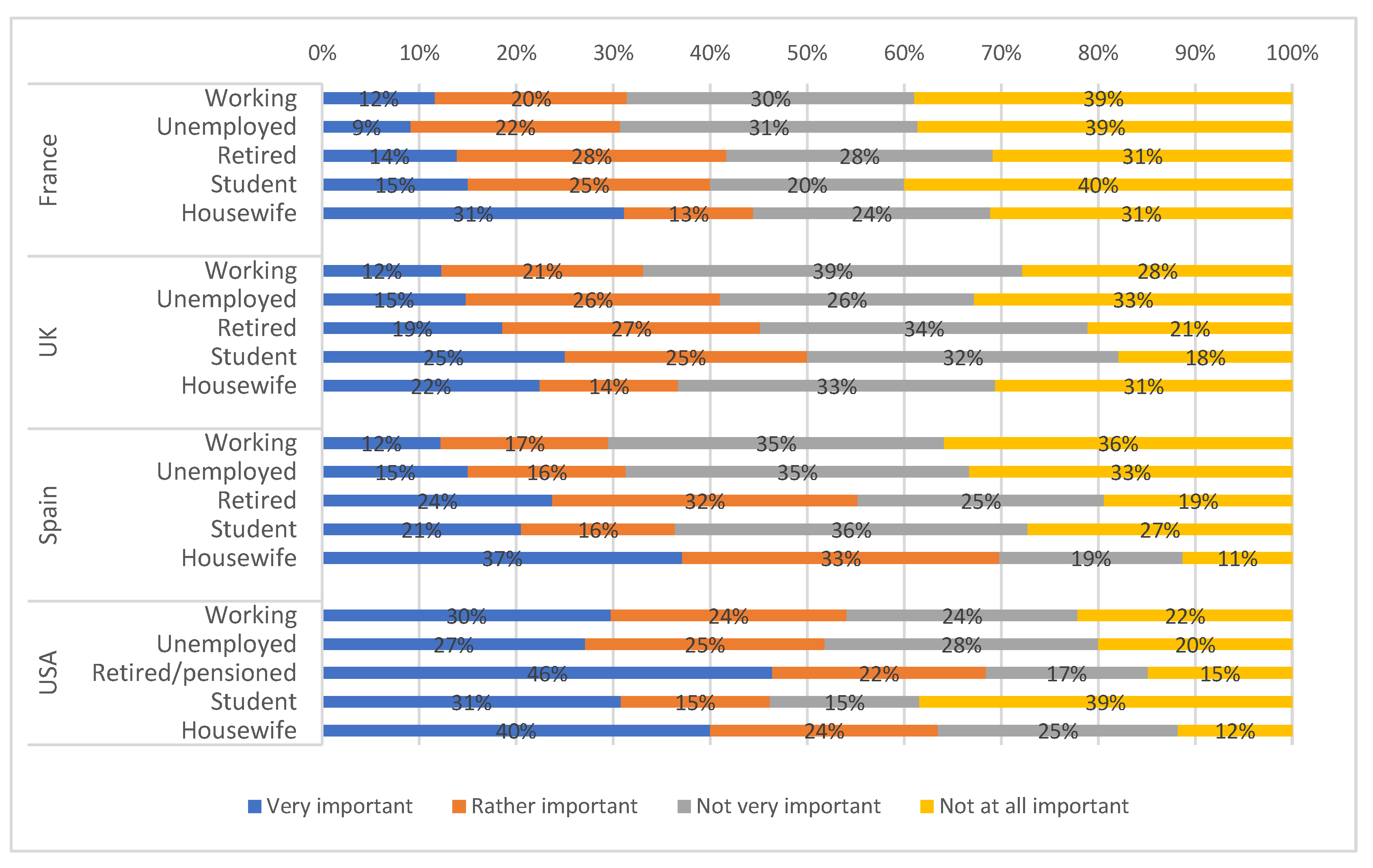

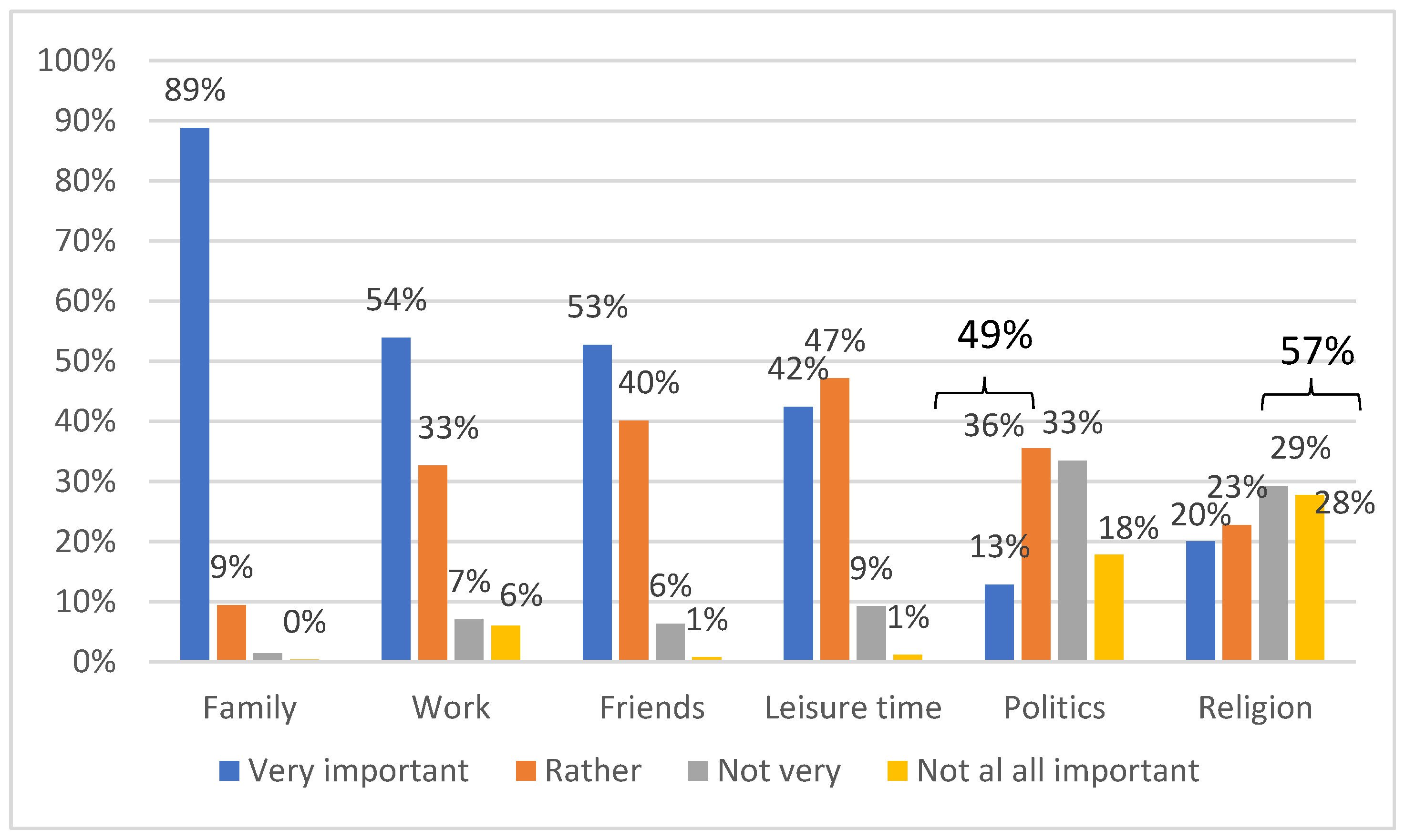

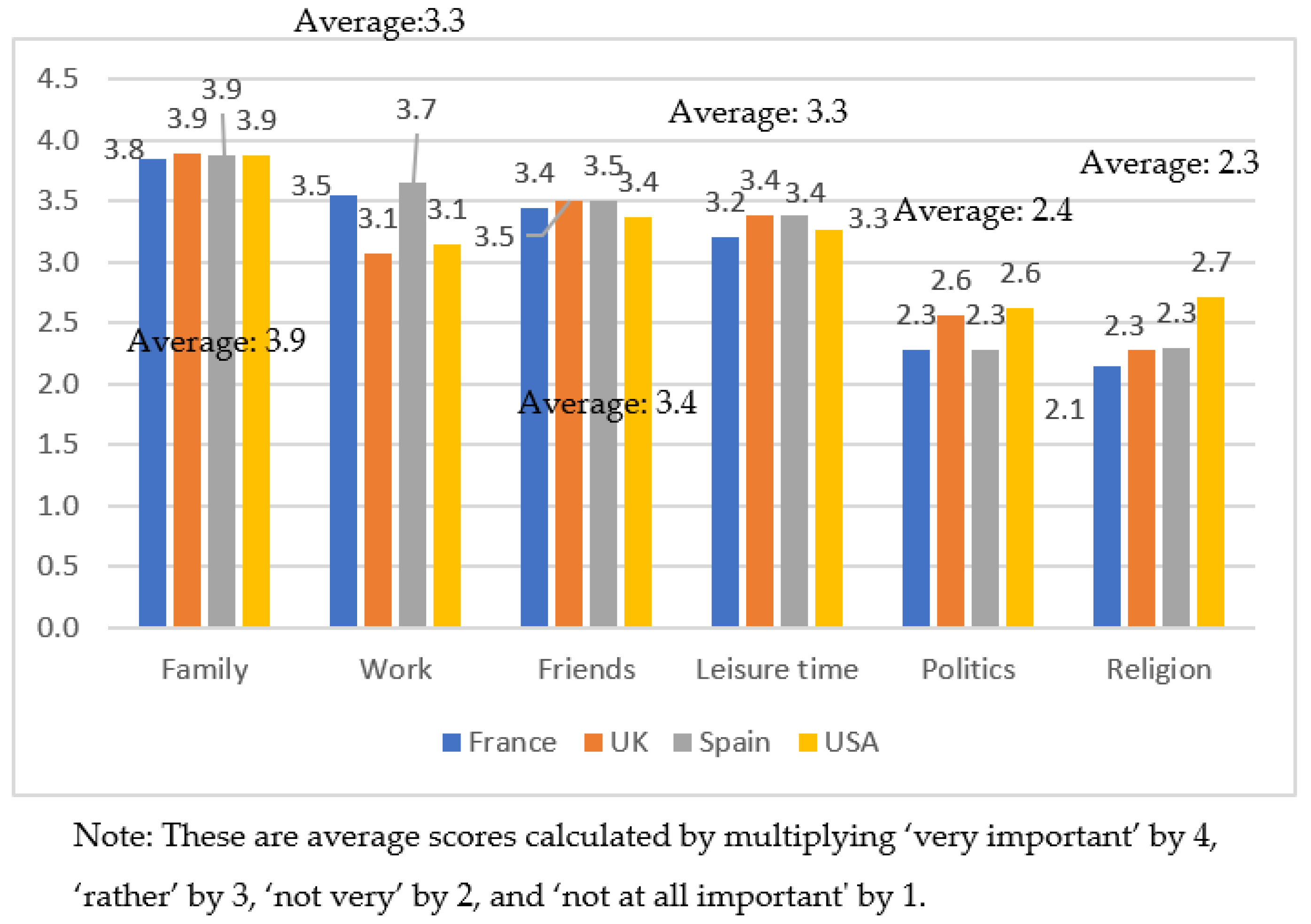

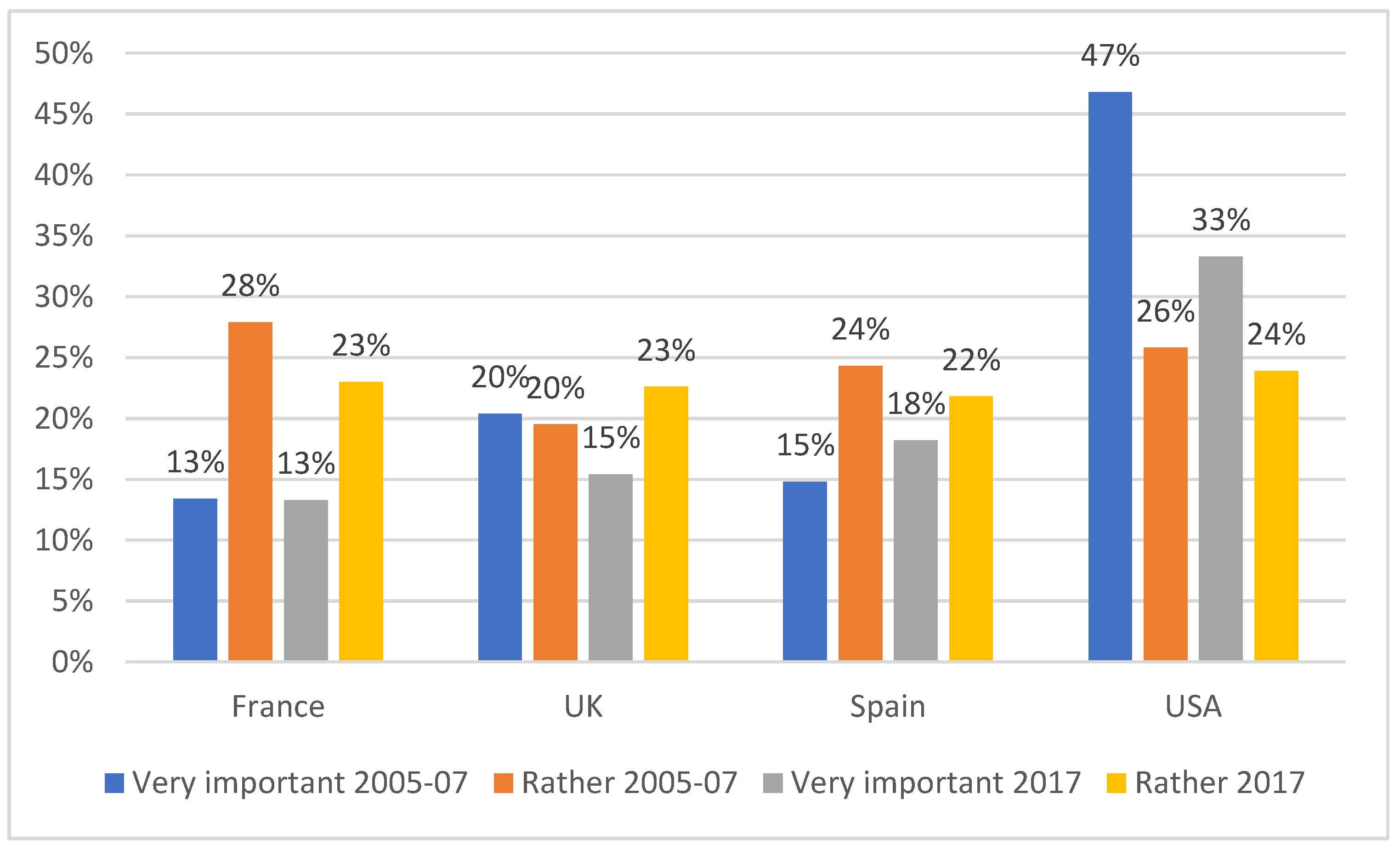

The country-by-country analysis shown in

Figure 25 reveals little variation in family, friends, and leisure (standard deviations of 0.02, 0.06, and 0.09, respectively), increasing notably in politics (0.18), religion (0.25), and work (0.29). The latter shows the greatest differences between countries, an aspect to which we will not devote attention as it is far from the object of study of this paper. Religion is the second aspect that varies the most between countries, with a low value given by the French and great importance in North Americans standing out. Focusing on religion,

Figure 3 shows the evolution over the last 10 years, since the 2005/07 measurement:

- -

France presented the lowest levels of ‘very important’ (13%) in 2005, a situation that hardly changes a decade later. Now, the high number of people considering it ‘rather important’ in 2005 is reduced by 5 percentage points in 2017.

- -

The UK had ‘very important’ levels of 20% in 2005, dropping five percentage points in a decade. ‘Rather important’, meanwhile, is up three points over this period.

- -

The situation in Spain is slightly different from the rest of the countries, being the first country with a slight increase in ‘very important’ and a slight decrease in ‘rather important’.

- -

Respondents from the United States experience the greatest decrease in the importance of religion, especially when considering the evaluation of religion as “very important’. The 47% who expressed this opinion in 2005/07 fell to 33% in the latest wave, a decline of 14 percentage points. The same trend is found in the ‘rather important’ category, although with a lower incidence (2 percentage points).

In short, there has been a decline in the importance of religion among respondents, primarily in the United States, with a grouped decline (very + rather) of 16%, followed by a 5% decline in France. In the United Kingdom, this situation is fainter, showing 2 percentage points, with the Spanish showing a different situation with a slight increase (1%) in the importance of religion.

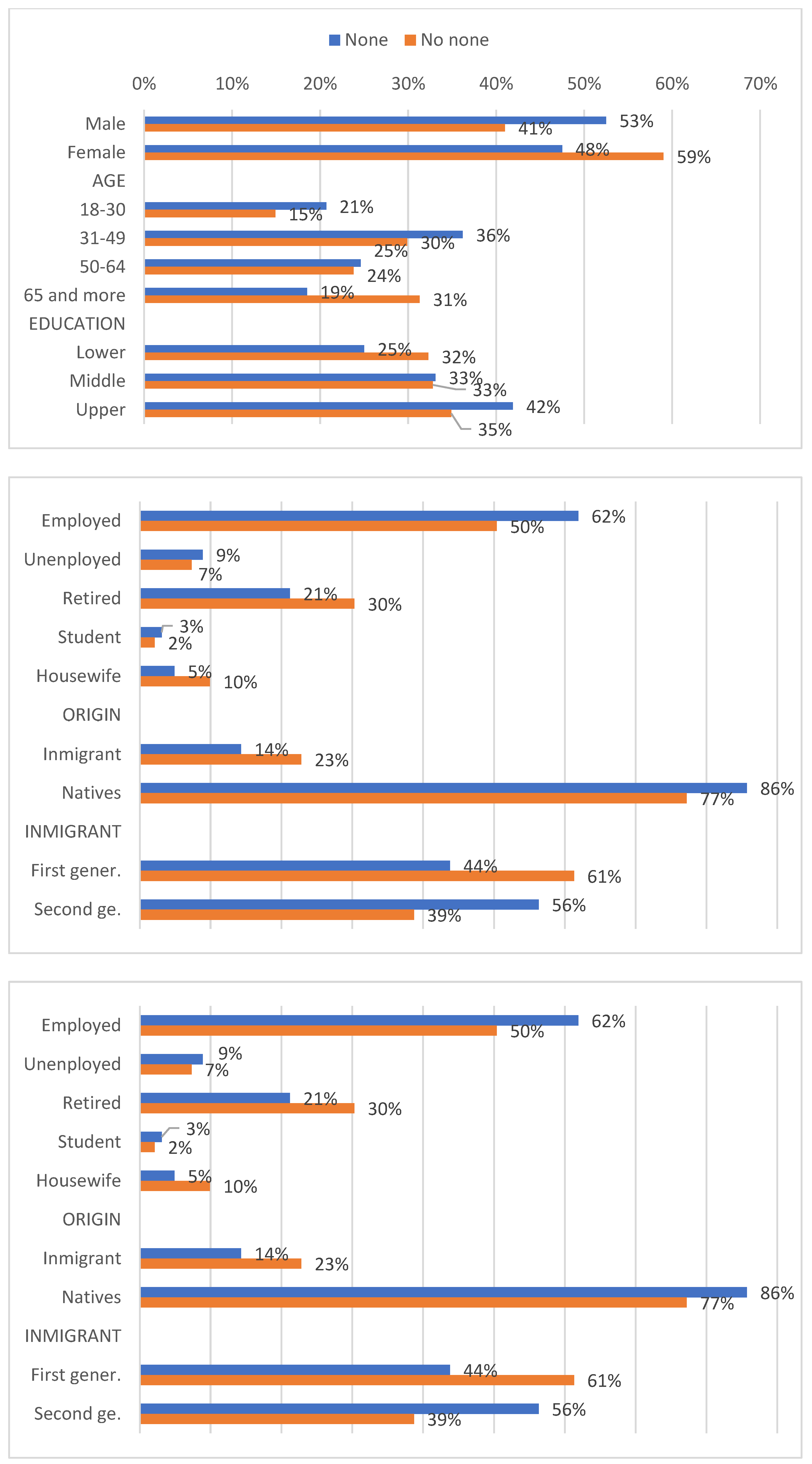

At this point, it will be interesting to determine how the different sociodemographic variables influence the perception of the importance of religion, information that is shown in the figures in

Appendix C. Beginning with gender, women consider it more important than men in all countries, with differences—in the ‘very important’ response—of between 3 and 5%, increasing to 11% in the case of Spain. The differences are similar in the case of ‘rather’, a category in which Spain returns to normality, and it is the United Kingdom where the differences between men and women increase. Spain and the United Kingdom are the countries with the largest differences between men and women (Cramer’s V

6 of 0.17 and 0.16, respectively, both with significance < 0.0001).

In the case of age, the high percentages of the ‘very important’ response in the United States stand out (between 27 and 49%), with an increase with increasing age. This trend (an increasing importance of religiosity as age increases) is not as clear in European society (France, the United Kingdom, and Spain). However, in all countries, older people give more importance to religion, especially in Spain.

Despite this trend, in France and the United Kingdom, the youngest group (under 30 years of age) give more important than the next group (between 31 and 49 years of age and between 50 and 64 years of age). The most important differences in the case of age are found in Spain (Cramer’s V 0.32) and the United States (Cramer’s V 0.18), both with significance < 0.0001.

With regards to educational level, people with lower levels of education give greater importance to religion. Focusing on European countries, France and Spain stand out, where approximately half (44% in France and 49% in Spain) of people with a low level of education consider religion ‘very’ and ‘rather’ important; a situation that in the United Kingdom reaches 40%. This percentage decreases notably among those who have completed higher education, dropping to 33% in France and 26% in Spain, the lowest figures in the series. These figures are notably lower than those presented in North American society, with a greater importance of religion at all levels of studies, although greater in people with a low level of education, where 76% consider it ‘very’ and ‘rather important’. The common trend in the four countries is a reduction in this importance among those with higher levels of education, but with a “moderate” decrease in the case of the European countries, less accentuated in the case of the United Kingdom. The greatest differences are again found in Spain and the United States (Cramer’s V of 0.21 and 0.14, respectively, both with significance < 0.0001).

With regards to the relationship with activity, each of the groups will be differentiated in detail:

- -

Religion is considered of little or no importance in all European countries in approximately 7 out of 10 employed people (71% in Spain, 69% in France, and 67% in the United Kingdom), a rate similar to that of the unemployed. This trend changes in the United Kingdom, where it drops to 59%. Only 46% of American workers (employees) consider religion little or unimportant, similar to the unemployed.

- -

Students are the next group in terms of the number of respondents who do not consider religion important, with percentages that reach 60–64% in France and Spain, respectively, dropping to 50% in the United Kingdom and the United States.

- -

The percentage of retired people who attach little importance to religion is slightly more than half of the population in France and the United Kingdom (58% and 55%, respectively), falling significantly in Spain (45%) and even more in the United States (32%).

- -

Something similar happens to those who carry out unpaid work, with high considerations of ‘not very important’ and ‘not at all important’ in the United Kingdom and France (63% and 56%, respectively), and very low in the United States and Spain (37% and 30%, respectively).

Again, Spain is the country where there is the greatest difference (Cramer’s V of 0.32), followed by France and, at a short distance, the United States (both with Cramer’s V of 0.16, all with significance < 0.0001).

In terms of geographic origin, most of those born in the country where they reside are characterized by a low importance of religion in their life (France with 69% and the UK with 68%), reducing to 62% in the case of Spaniards and up to 43% in those residing in the United States.

In all European countries, the first generation is characterized by attaching great importance to religion in their life, with approximately 60% of those interviewed considering it very and fairly important. In the second generation, religion loses importance and is only important for slightly more than half of the residents in France and the United Kingdom and for one in four Spaniards. The greatest differences between the groups occur in the United Kingdom and France (Cramer’s V of 0.31 and 0.28, with significance < 0.0001), and there is no relationship in the United States.

In short, the groups that attach more importance to religion are women (10 percentage points difference with respect to men), people over 64 years of age, respondents with low education, those with unpaid domestic jobs and retirees, and first-generation immigrants. The comparison of Cramer’s V’s reveals the greater influence of geographic origin in France and the United Kingdom, as well as age and activity relatedness in Spain (and somewhat less in the United States).

In the same way, in this section, we have analyzed the importance of religion within different aspects of life, by way of contextualization, and it has revealed the low importance of religion when compared with family, work, friends, leisure time and politics. It is an importance that, moreover, has decreased since 2005/07.

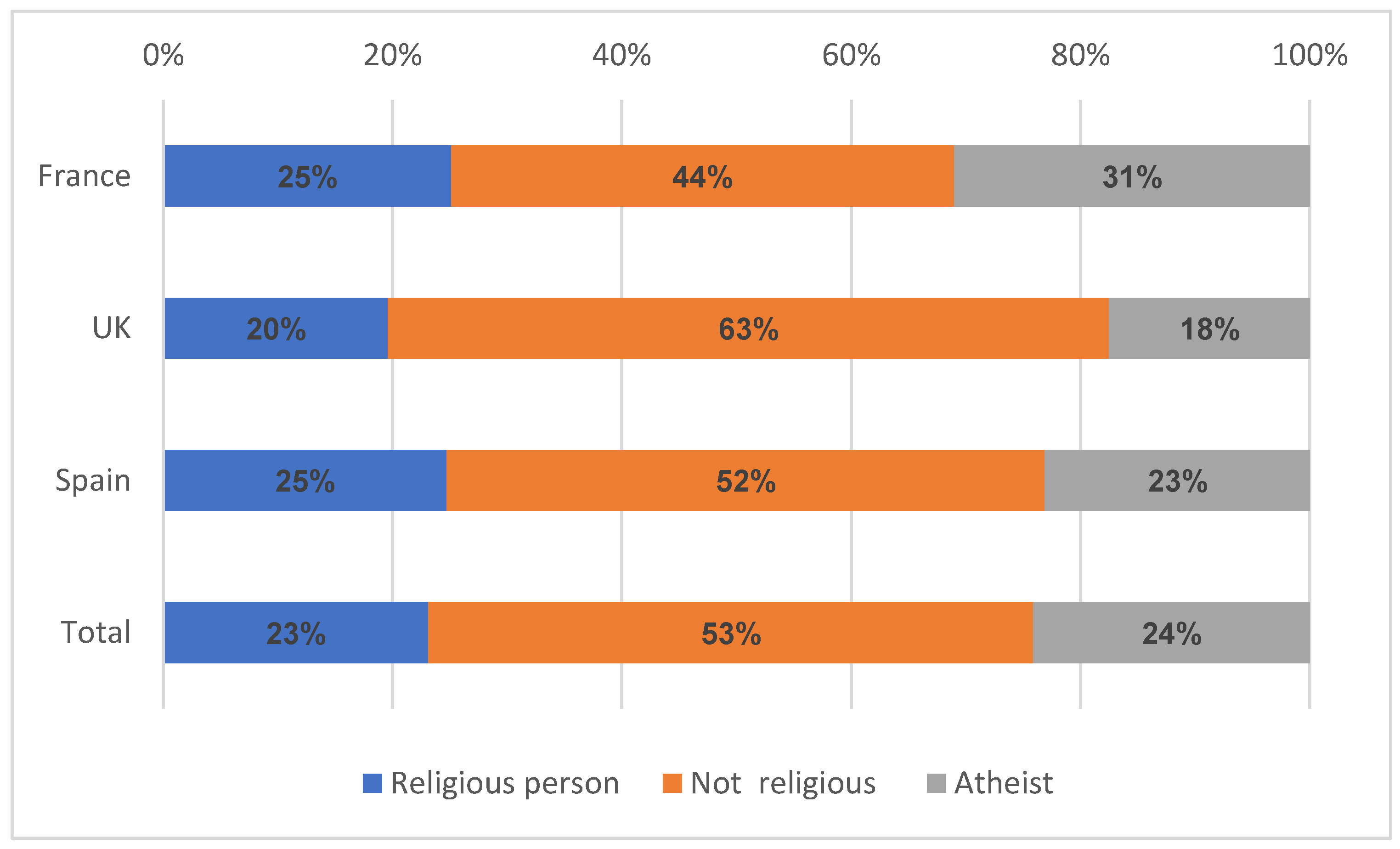

3.2. Level of Religiosity and Membership in Religious Denominations

Having exposed the low importance of religion in the life of the interviewees in the previous paragraph, it is time to determine the “religious denomination”, to what extent the interviewees consider themselves religious, as well as their membership in religions. These two aspects will be addressed in this section.

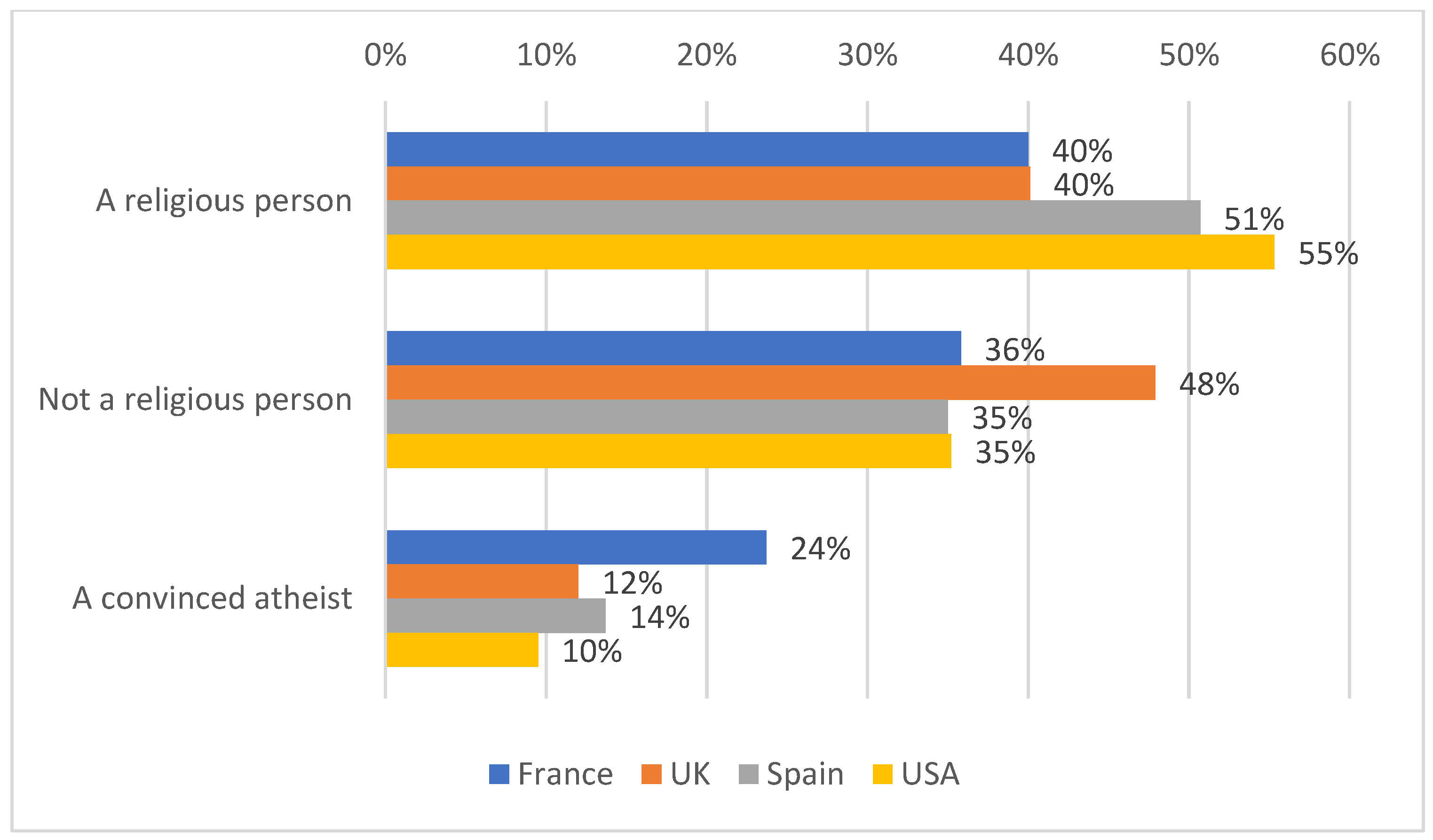

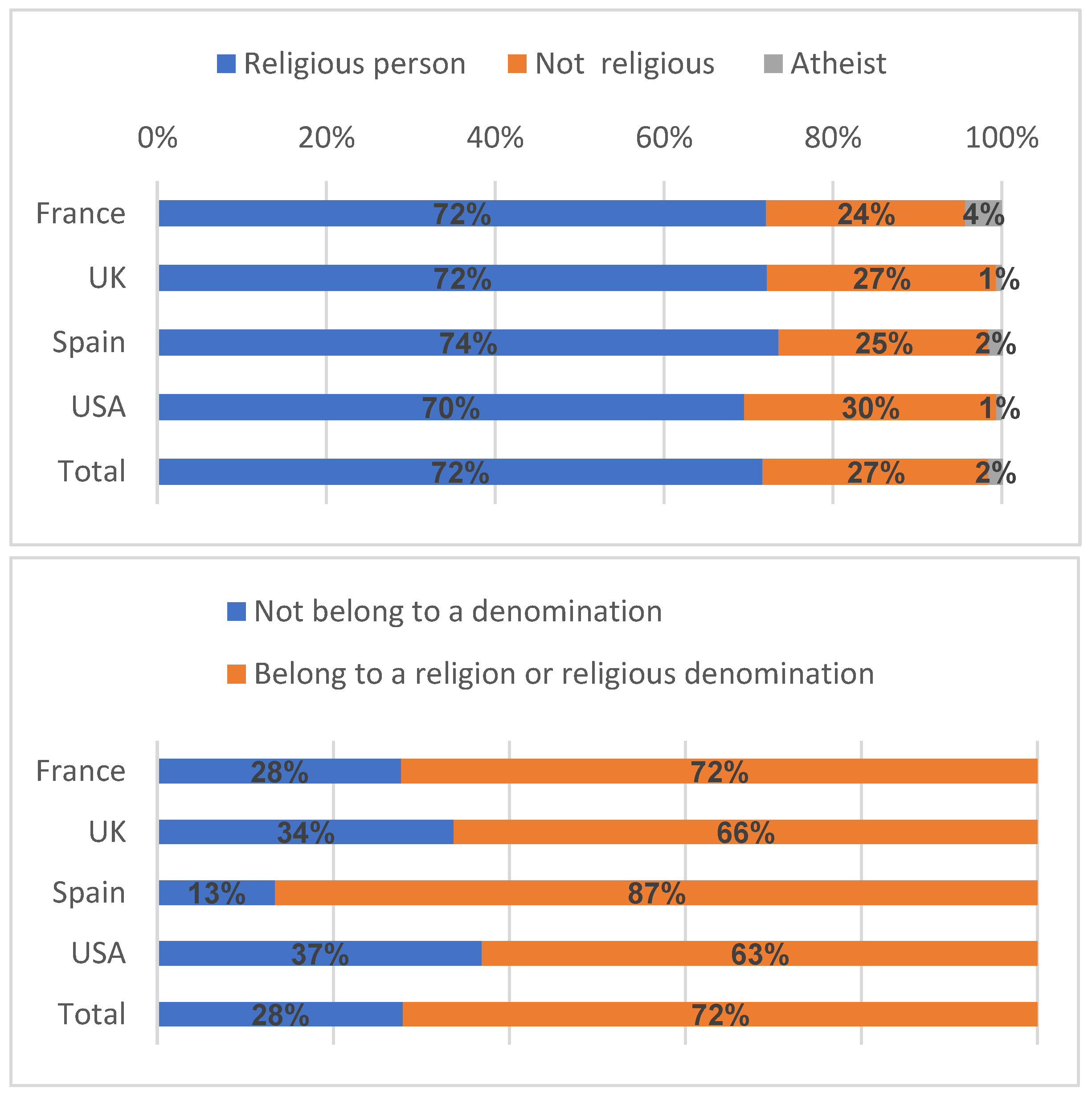

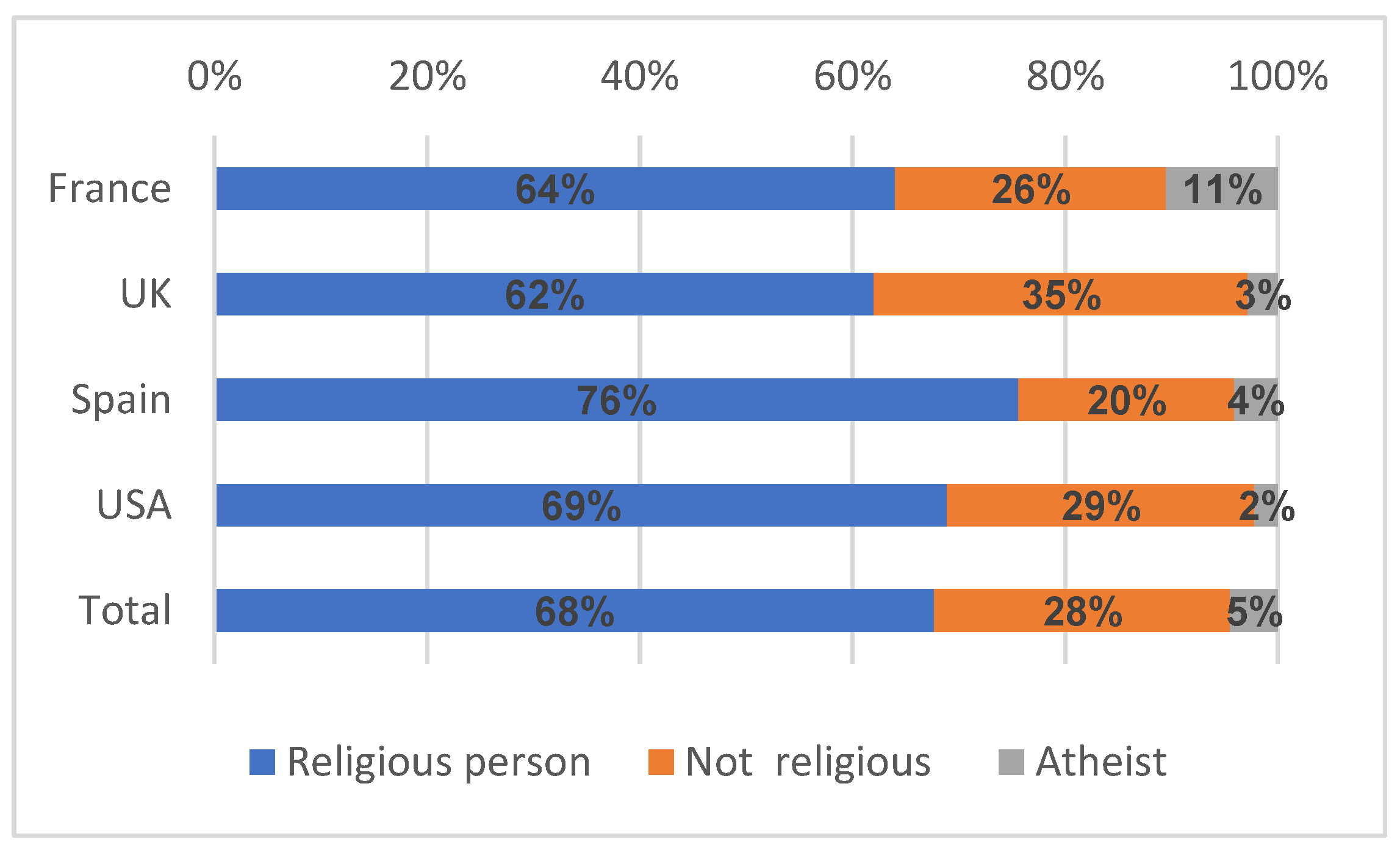

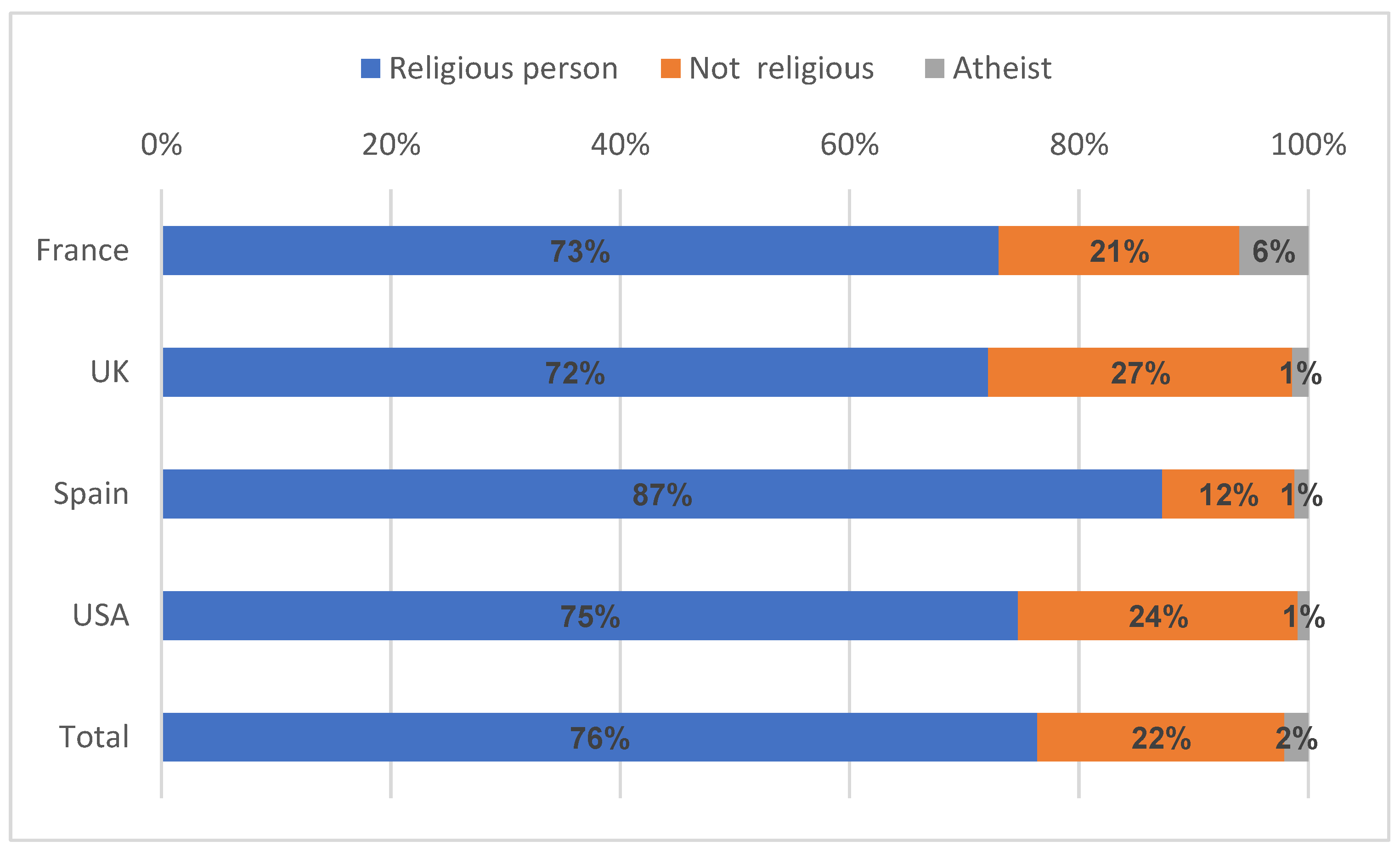

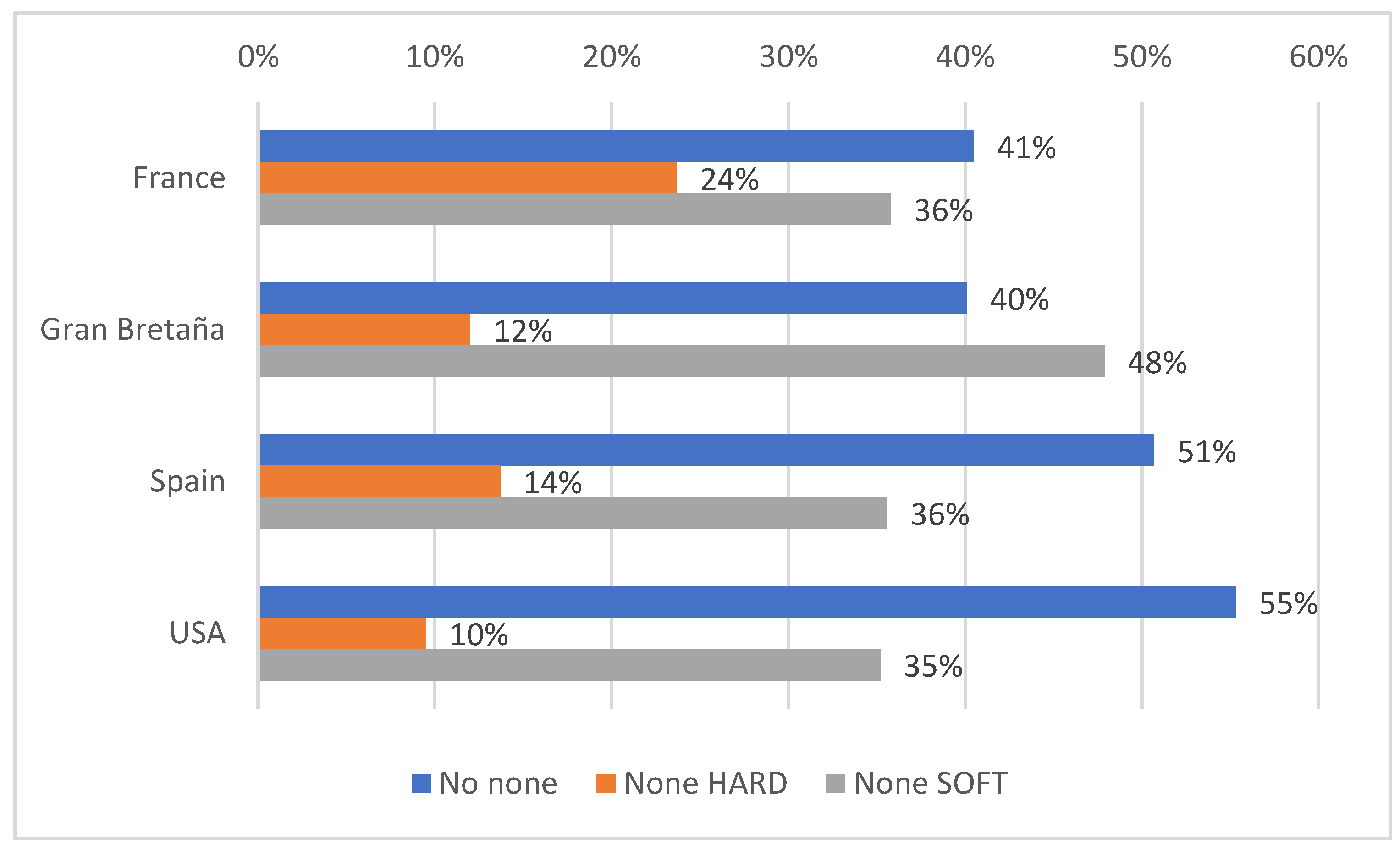

Starting with “religious denomination”, 47% of the residents in the countries under study consider themselves as religious, 39% as non-religious, and 15% has convinced atheists.

Figure 4 shows the responses to this question for the different countries considered, where we can observe the lower number of religious people in France and the United Kingdom, as well as the high religiosity of North Americans and Spaniards. The United Kingdom also stands out for the high number of people who declare themselves non-religious, at 48%, while the differentiating element in France is that a quarter of its population consider themselves convinced atheists, in line with what has been detected by some experts (among others,

Cuchet 2018).

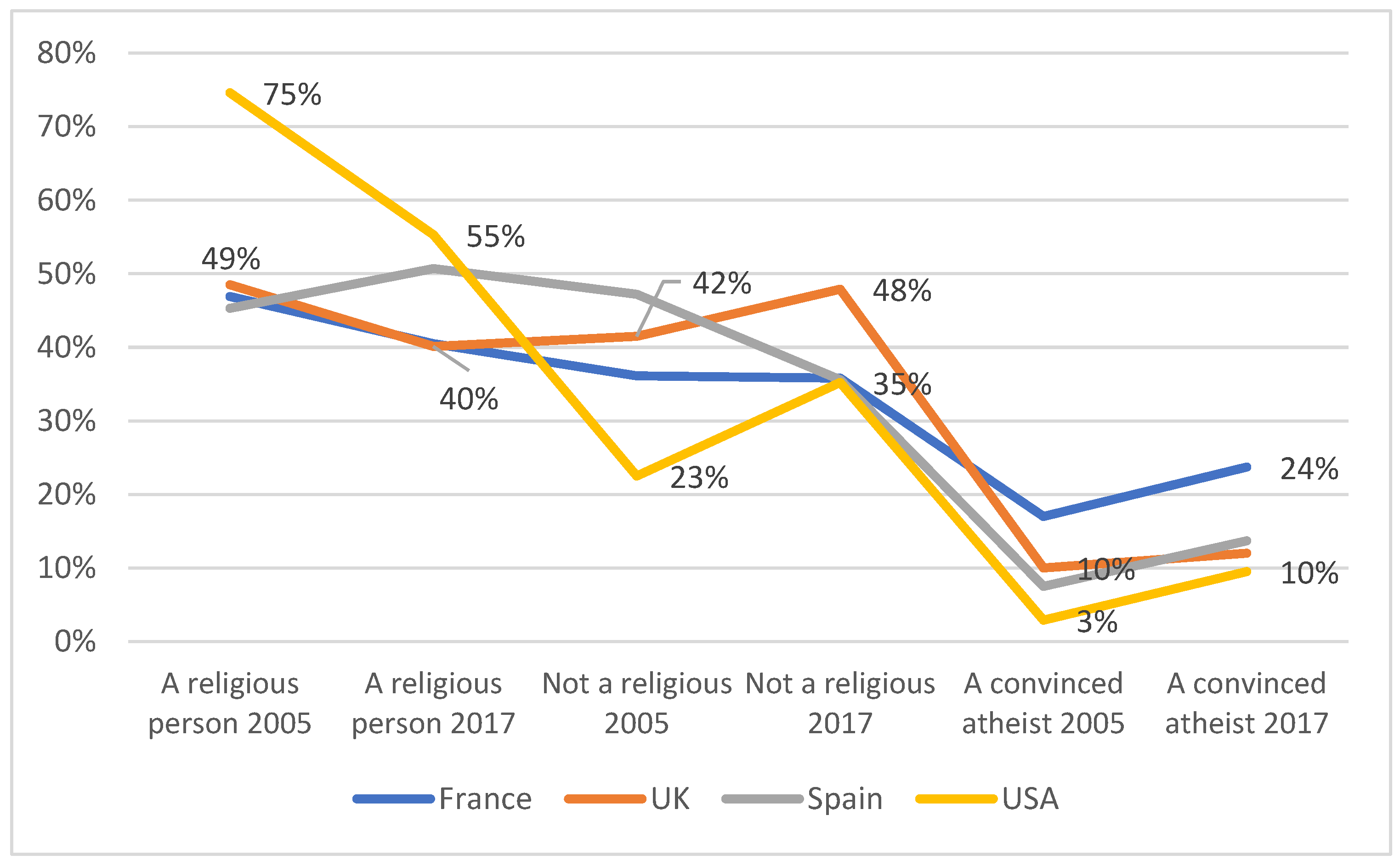

The evolutionary analysis since 2005/07 shows a large decline in religious people in the United States, with a decrease of 19 percentage points, a marked increase (13%) in people declared as non-religious, and even more for atheism, which triples in the period analyzed (

Figure 5). This is a recent phenomenon that has generated research to find out who they are, where they come from, and to what extent it is a stable phenomenon or whether it will grow over time. Some researchers—Burge, for example—have defined them as nones, a phenomenon that according to the Cooperative Congressional Election Study of Harvard University affects 31.3% of Americans; that is, almost a third of Americans have no religious affiliation (

Burge 2021).

The decline in self-declared religious people is notably lower in France and the United Kingdom (6 and 8 percentage points, respectively). As for the non-religious, we can observe stability in France and a slight increase in the United Kingdom (6 percentage points), as well as a significant increase (7%) in atheists in France and a small increase in the United Kingdom (2%). In other words, the decline in religiosity in France leads to a greater number of atheists, while in England, there is a greater preference for the “non-religious” response.

It is important to note that the high level of atheism of the French people did not occur in the period of 2005/07 and 2017, but already in 2005/07, 17% of respondents considered themselves convinced atheists. In fact, the increase between 2005/07 and 2017 is 7 percentage points, the same as in the United States.

Spain presents a very different behavior with a slight increase (5%) in religious people and, curiously, a decrease (12 points) in the number of respondents who declare themselves non-religious. The consultation of other editions of value surveys reveals stability in the number of religious people between 1980 and 1990, and a significant decline in the last decade of the twentieth century and the first decade of 2021 (

Urrutia León 2010). In fact,

Figure 4 shows a level of atheism slightly higher than the United Kingdom and 4 percentage points higher than the United States, which configures Spain as the country with the second highest number of atheists in the world.

To find out how different sociodemographic variables influence the variable under study, we used a logistic regression that uses dichotomized religious denomination as the dependent term, that is, grouping non-religious and atheists into a single value, so that the variable compares “people who declare themselves to be religious” with the rest. The use of this technique will make it possible to determine the incidence of sociodemographic variables on the self-definition of oneself as a religious person. The independent variables considered are sex, age (15–30, 31–49, 50–64, and 65 and more years), level of studies (lower, middle, and upper), relationship with activity (working, unemployed, retired, student, and housewife), whether or not the respondent is part of the working population, and whether or not he/she is an immigrant

7. These terms have been coded considering the last category as a reference, and their coefficients are interpreted as the effect on the dependent variable of a one-unit change in the independent variable, keeping all other variables constant.

In order to select only the variables with an influence on religious self-identification, and thus achieve a parsimonious model, a forward stepwise regression process was used to test the entry of variables based on the log-likelihood test. The advantage of regression, as opposed to the bivariate analyses used in the past, is that it analyzes the influence of each variable on the dependent term while controlling for the influence of the other variables.

The resulting model, shown in

Table 4, reveals the small number of significant terms, as well as the low explanatory power of the model, which shows the low influence of the sociodemographic variables on self-identification as a religious person (dependent term), with Pseudo R values of approximately 0.11 in France, increasing to 1.5 in the United Kingdom and reaching almost 2 in Spain. The United States is the country with the worst fit to the model.

Table 4 shows the significant coefficients together with their significance levels of 0.10 (*), 0.05 (**), and 0.01 (***). The coefficients of the relationship with activity are not presented because of their low contribution to self-identification as a religious person.

The analysis of the coefficients of the French respondents begins by considering that practically all the comparisons with the reference category are significant, with the exception of the working population and respondents with medium education. Native–immigrant origin is the variable with the highest coefficients, indicating that the probability (odds) of being considered religious with value 1 (born outside France) is 2.86

8 times higher than those born in France. As for age, it is the variable with the second highest coefficients; note the large negative values of the youngest respondents, coefficients that decrease as the age of the respondent increases, indicating that the older the person is, the greater the self-identification as a religious person.

With respect to the level of education, the logic of considering oneself a religious person is 1.825 times greater among respondents with low education than among those with university education, with the coefficient of medium education having less influence, indicating a lower self-definition as a religious person as the level of education increases. Being a woman increases the probability of self-defining oneself as a religious person by 1.46 times.

The situation in the United Kingdom is similar, except for the disappearance of the influence of educational level, and also differs in the magnitude of the coefficients—much higher than in France—as well as in the incorporation of a new variable, the fact of being part—or not—of the working population. Consideration as a religious person is 1.45 times higher among those who do not form part of the active population than among those who are active.

In Spain, the trend is similar, with the highest coefficients in the case of age, somewhat lower than in France in terms of the influence of educational level, and between the two in the case of place of birth. Sex is the second most influential variable, after being born or not in the country of residence, with women denominating themselves as religious twice as often (2.003) as men. The specificity in the United States is the null influence of educational level and origin, with age and sex behaving as in previous cases.

In short, nativeimmigrant origin is the most influential variable in self-definition as a religious person, except in the United States. The United Kingdom and Spain present the highest coefficients, which implies a greater influence. A high relationship with age can be observed—of greater magnitude in Spain—which implies greater religiosity as age increases. We do not consider this to be strictly an effect of age, but rather of the different socialization processes encountered by those born in the 1960s, 1970s, or 1980s. In fact, so-called millennials are characterized by less religious sentiment.

The level of education is the third most influential variable, presenting an inverse relationship insofar as people with less education are those who have higher levels of religiosity, present only in those interviewed in France and Spain. As for the specific characteristics of each country, in addition to the change in the coefficients, it is worth noting the greater religiosity of the inactive population in the United Kingdom and the disappearance (in this country) of the level of education to explain self-identification as a religious person. Furthermore, in the United States, only sex and age have a significant influence, with a minor level of influence of origin (native/immigrant) and level of education.

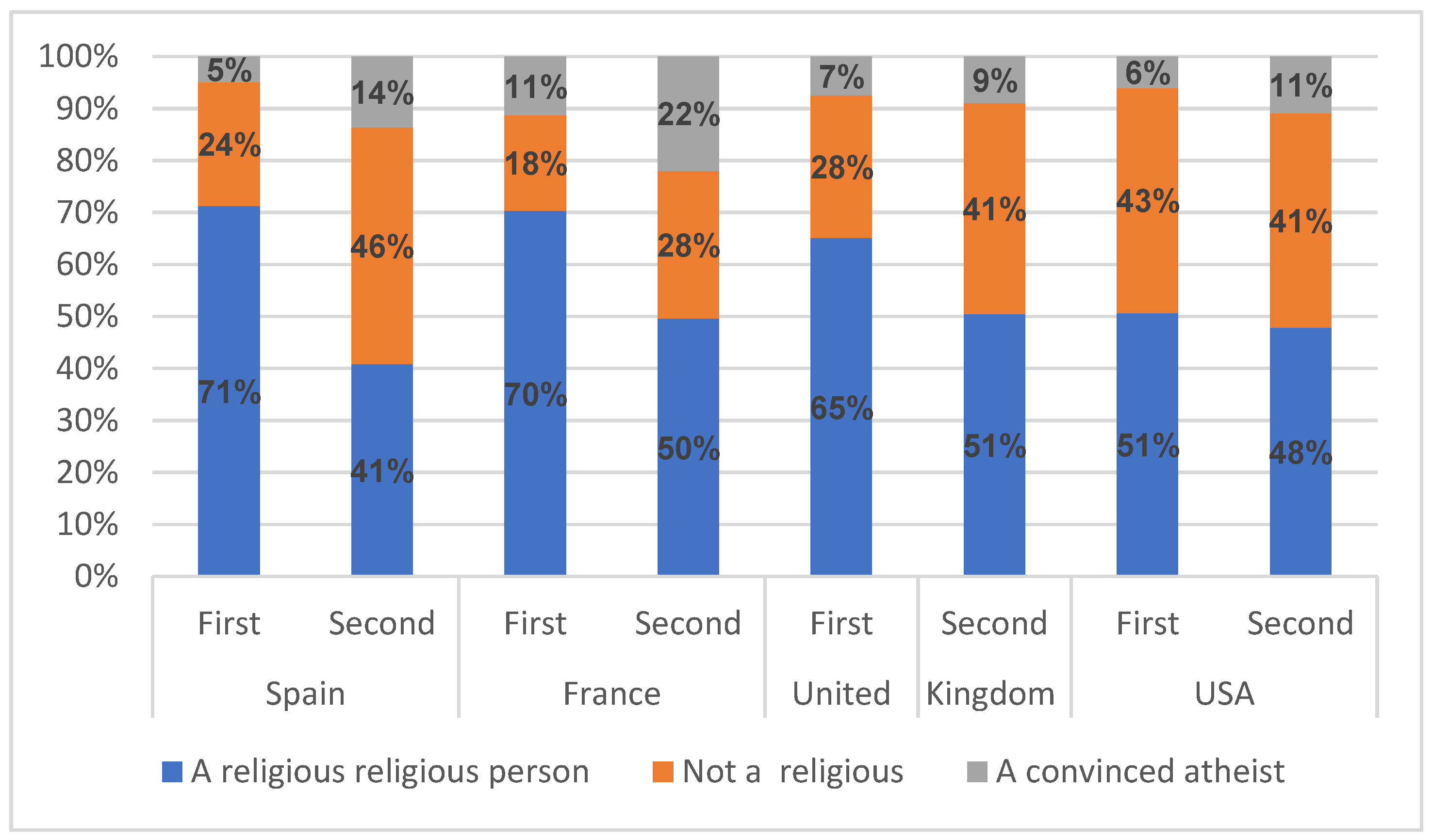

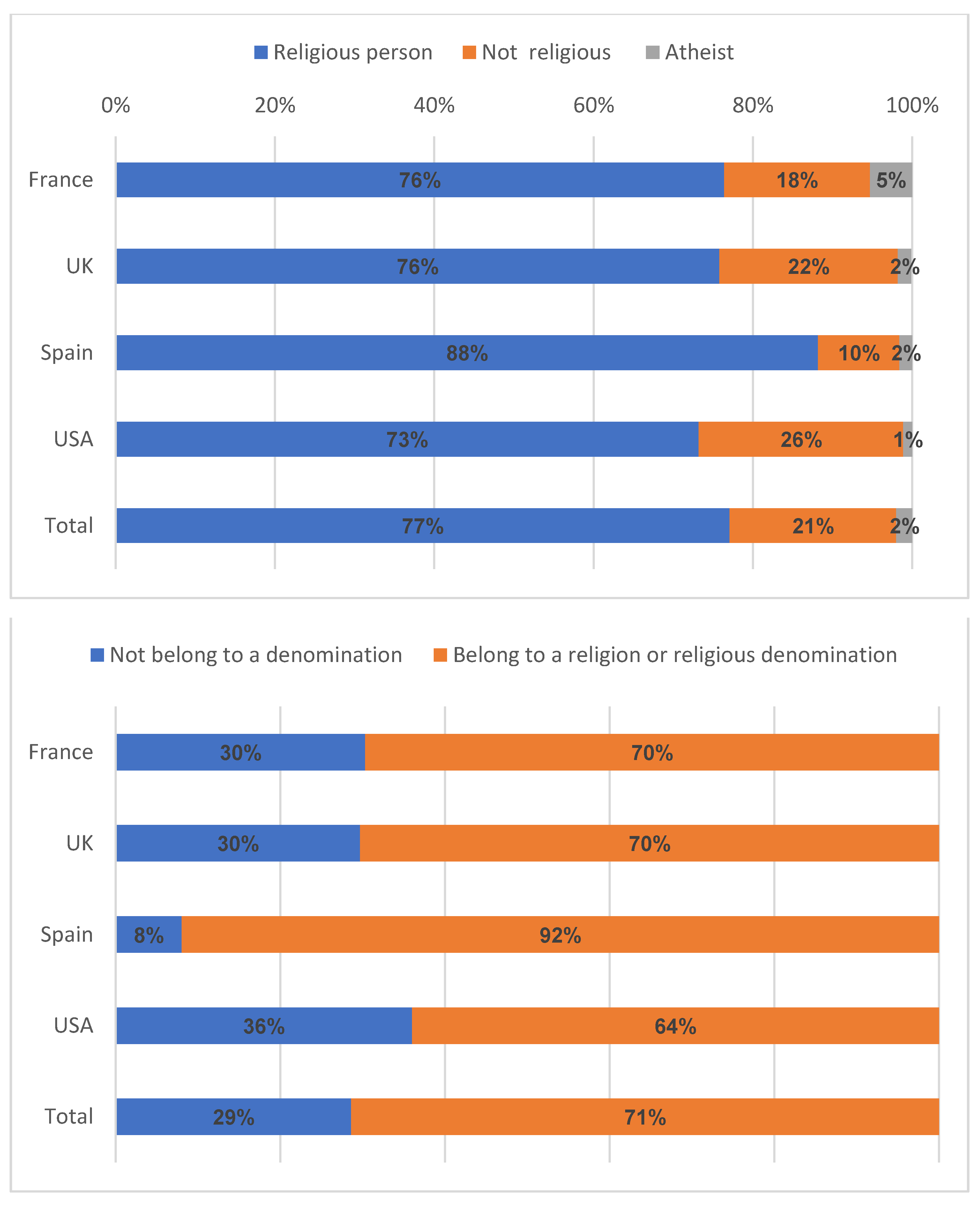

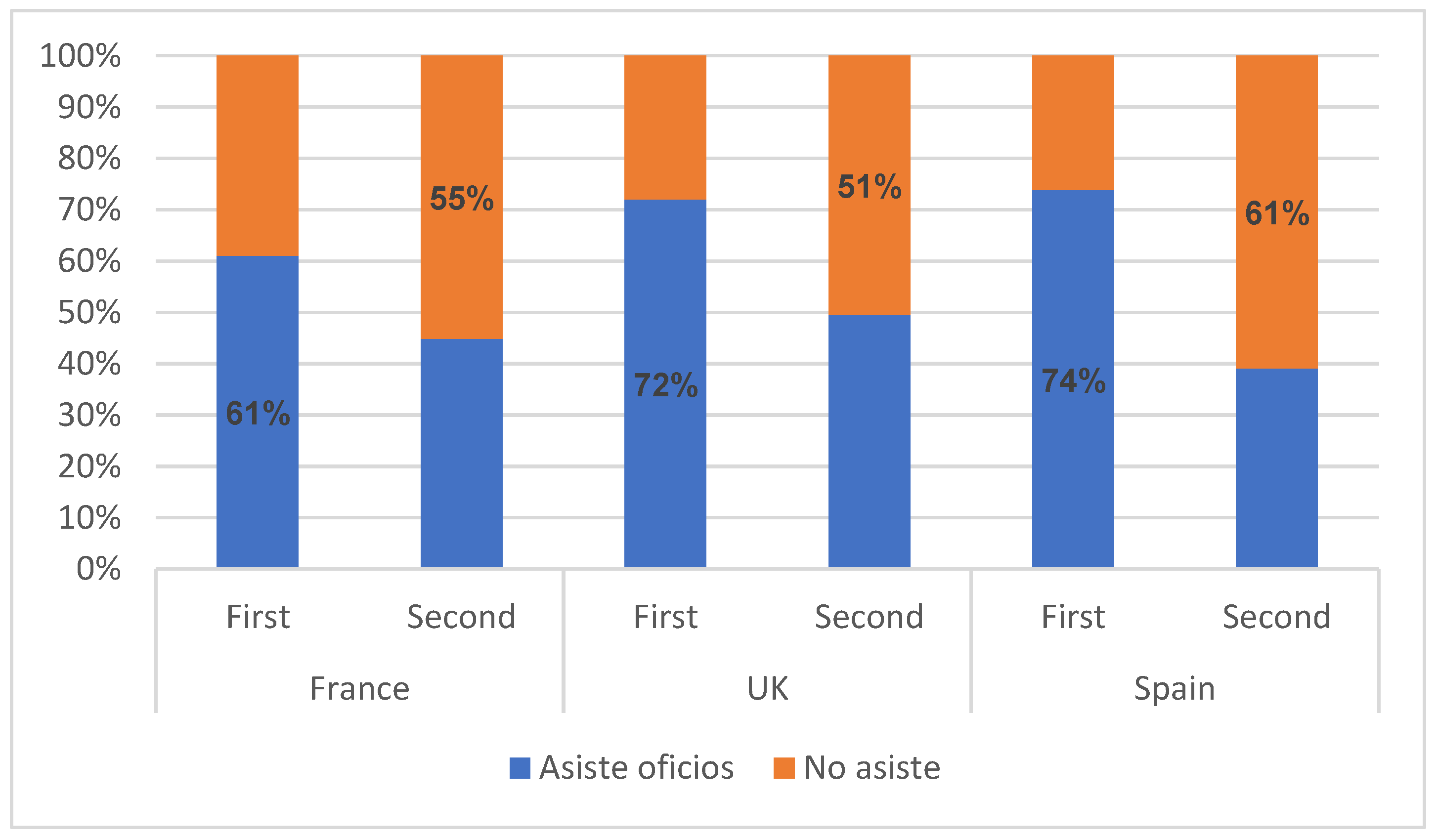

The high influence of being a native or an immigrant makes it necessary to determine if there are differences among the immigrant group, or if those of first or second generations call themselves equally religious persons; that is, if socialization in a different—and more secularized—society than the one in which the family originated shows differences in the definition of being religious or not. The data in

Figure 6 confirm this hypothesis in European countries, with Cramer’s V association coefficients (between religious denomination and immigrant generation) of 0.237 in Spain (significance of 0.02), 0.212 in France (significance of 0.03), 0.148 in the United Kingdom (significance of 0.064), and no significant relationship in the case of the United States (although it is included in the figure to contextualize the differences in the four countries).

Analysis of

Figure 6 shows that approximately 7 out of 10 people in the first generation consider themselves to be religious people, with 65% in the UK, a percentage that drops significantly in the second generation. There are 30 percentage points of difference in the case of Spain, 20 in France, and 14 in the United Kingdom. Thus, there is a notable change in second generations, at a time when religious wars star in the news in Western countries.

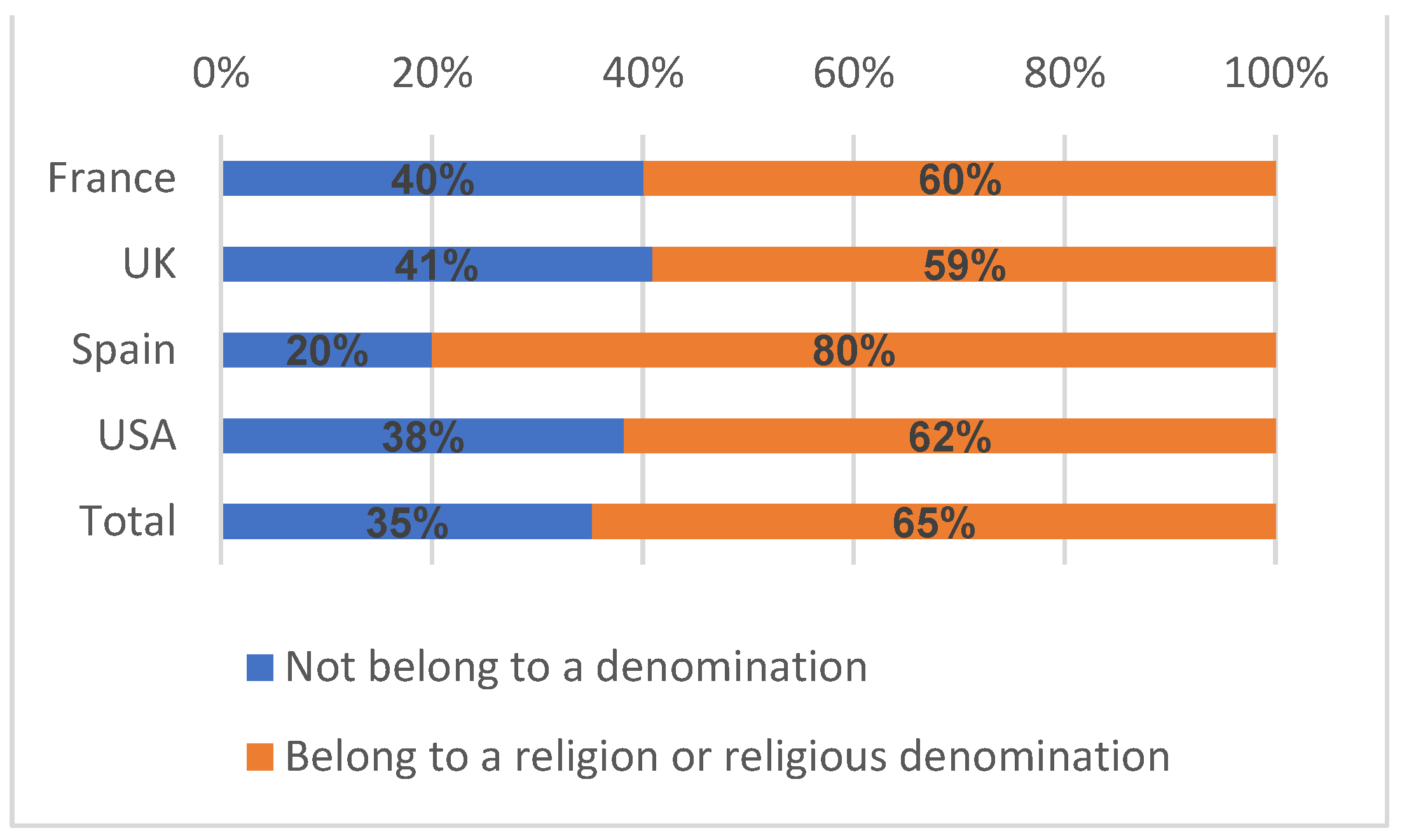

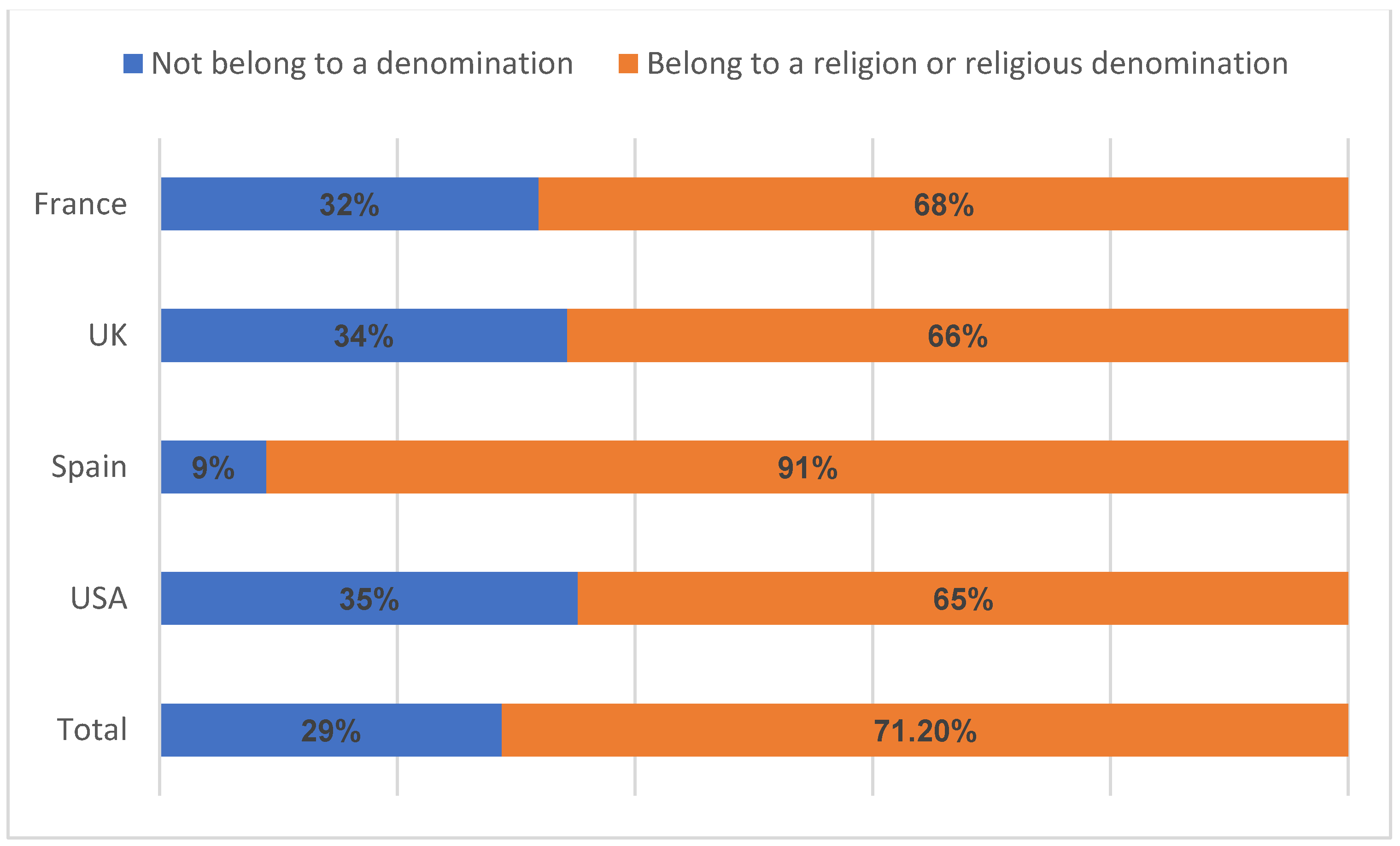

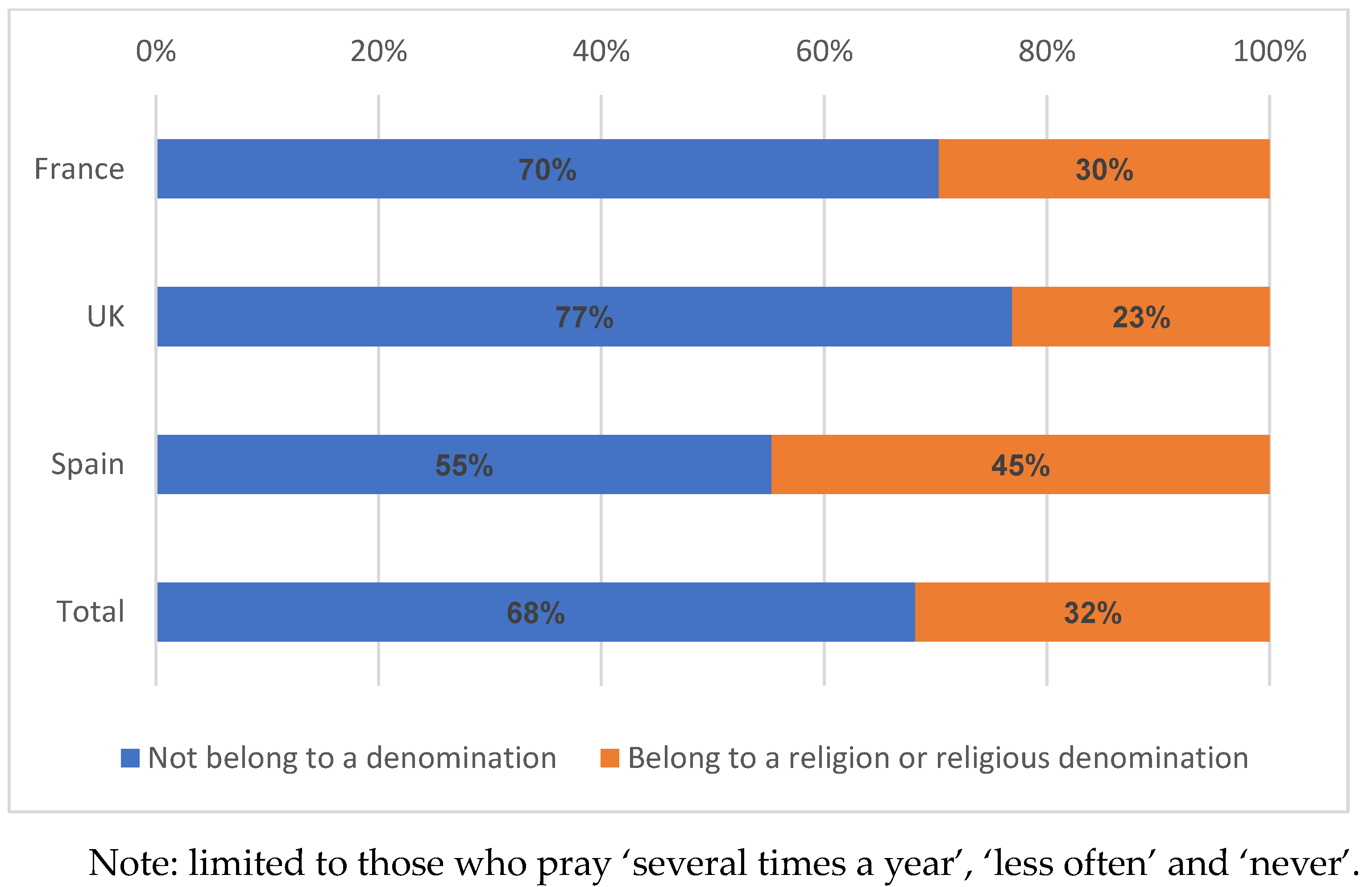

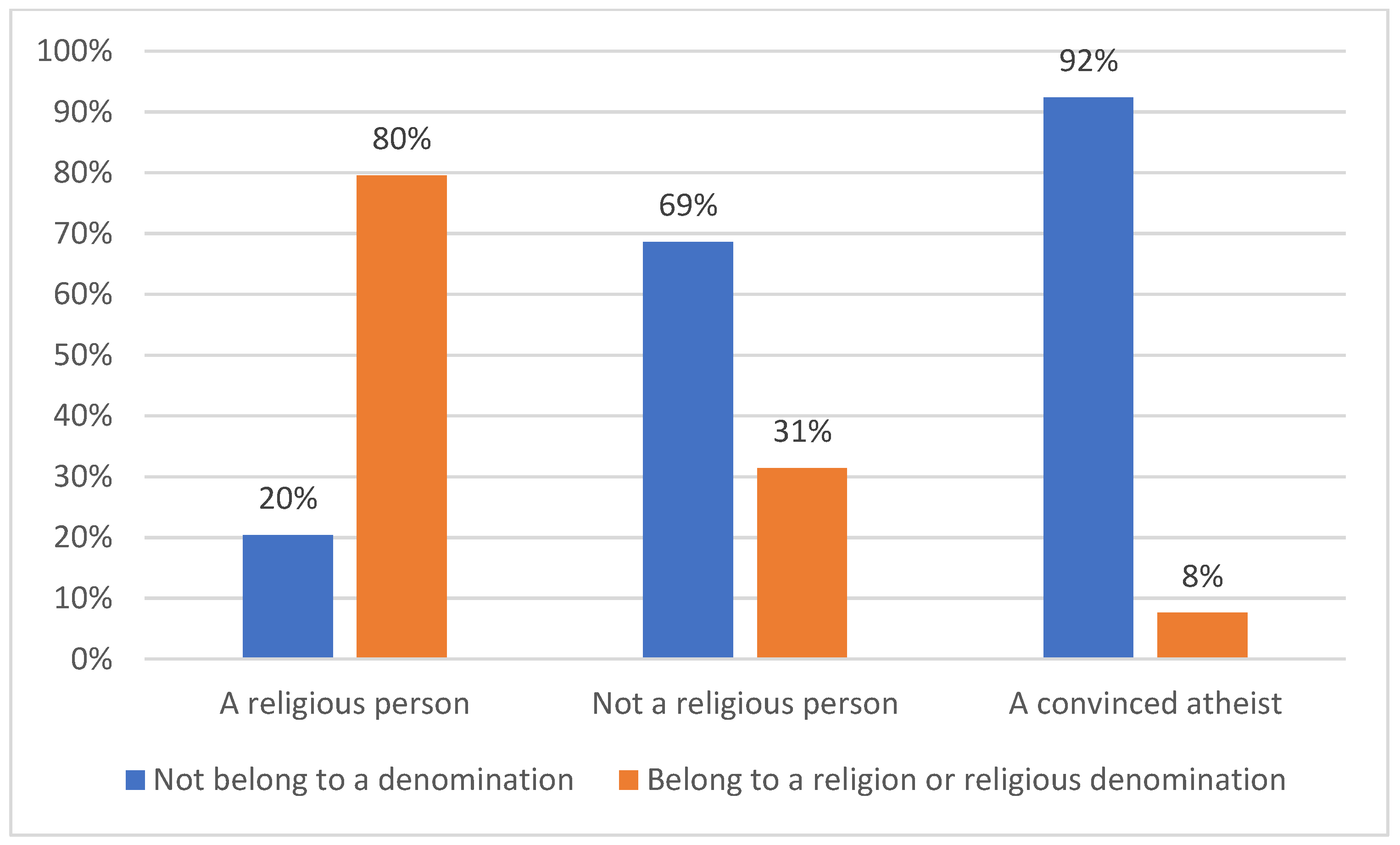

Religious denomination gives way to religious affiliation, a question asked of all respondents, regardless of the answer given in the previous question. However, it should be noted that one of the response options is ‘do not belong to a denomination’, chosen by 50% of the respondents, no doubt as a kind of “escape route” for atheists or for those who declared themselves non-religious. This average figure for half of the sample increases by nine percentage points in the French and seven in the UK when compared to the 2005/07 survey. Spaniards and North Americans show a greater upward trend (

Figure 7).

In any case, it is surprising that “only” 90% of atheists and 69% of those who declare themselves to be non-religious people choose this option. That is, it is striking that 10% of atheists and 31% of those who consider themselves non-religious persons answer the question about their religion.

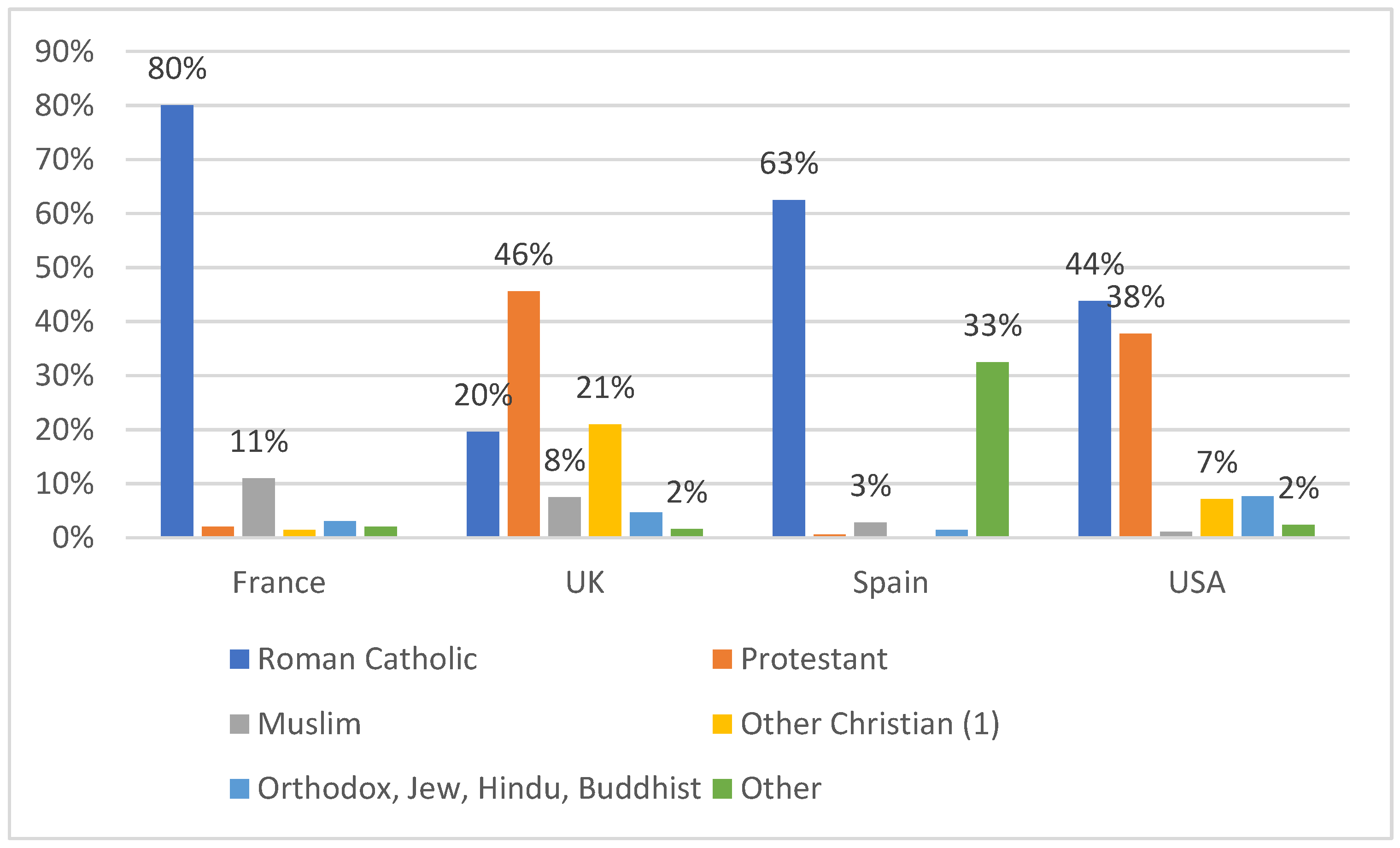

In the responses shown in

Figure 8, Catholicism appears as the dominant religion in three of the four countries, albeit with a very differentiated following. In France, 80% of those interviewed declared themselves Catholics, and the rest of the religions—with the exception of Muslims with 11% of those interviewed—are barely followed by 2% of the population

9 (6). In Spain, the level of Catholicism drops to 62%, with 3% of Muslims and a large number of religions grouped in the “other” category. The rest of the religions, with the exception of Orthodoxy (1.2%), do not reach 1%.

In the United States, the number of Catholics was again 44% of the population, barely above Protestants (38%). However, the distinguishing feature of this country is the large number of minority religions, such as other Christians (7.2%), Jews (3.5%), Buddhists (2.1%), Hindus (1.1%), Muslims (1.1%), Orthodox (1.1%), and others (2.4%). In the United Kingdom, something similar happens, undoubtedly because the predominant religion (Protestantism) is shared by less than half of the population (45.6%). This allows the proliferation of several religions, with other Christians (21%) and Catholics (20%) standing out. Other religions with a prominent presence in this country are Muslims (7.5%), Hindus (3.1%), Jews (1.0%), Buddhists (0.6%), and others (1.6%).

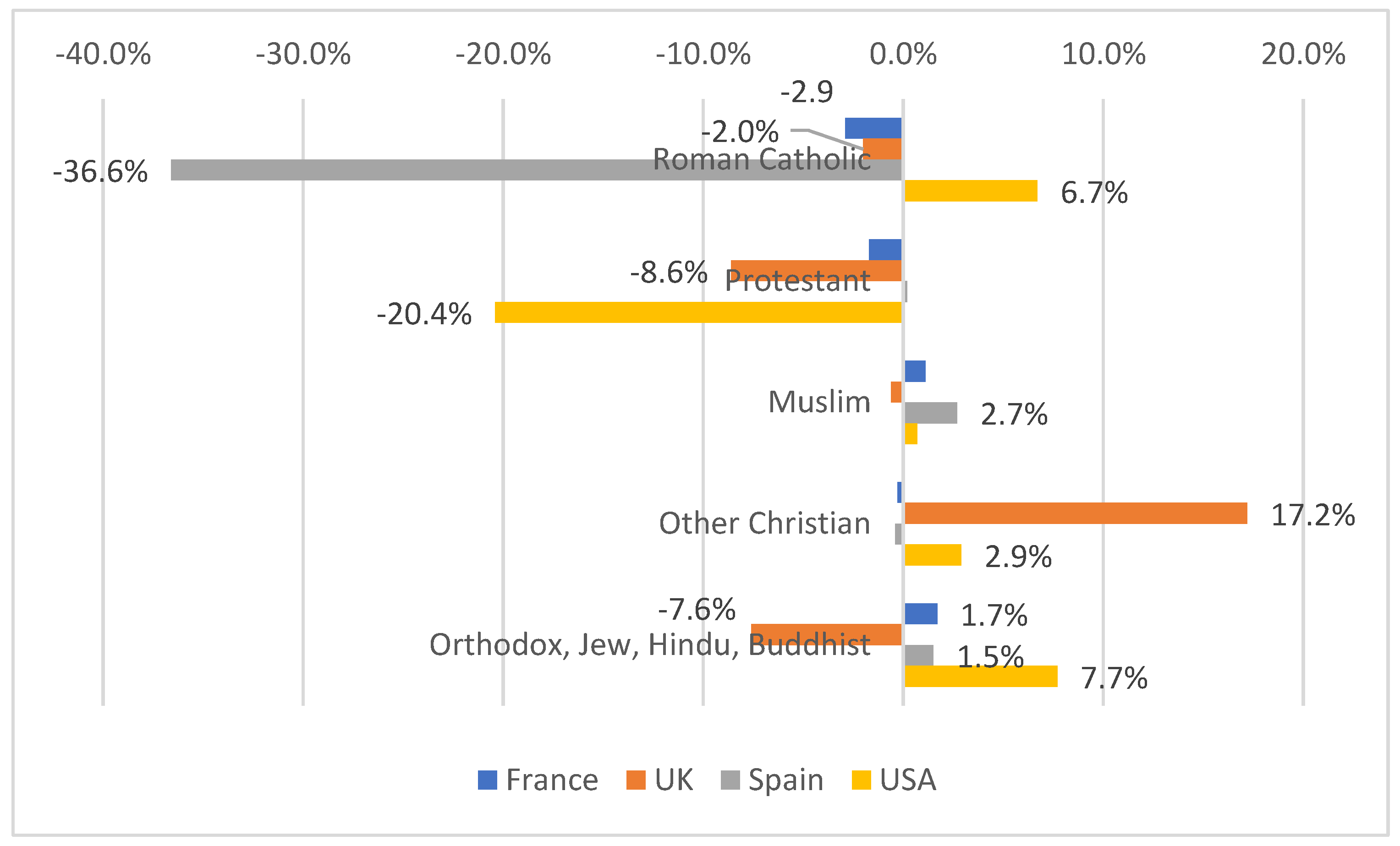

Compared to the wave of 2005/07,

Figure 9 shows decreases in the following of major religions, with Spain being the country with the highest rate of decrease (5.4%, compared to 0.4% in the United States and 0.3% in France and England). Strikingly, as shown in

Figure 9, there is a large decline of Catholics in Spain, with a decline of 37 percentage points, followed by the decline of Protestants in the USA, with a decline of 20.4 percentage points. The decline of Protestants in the United Kingdom is much smaller (8.6%), followed by the diverse grouping of religions with fewer followers such as Hindus, Jews, and Buddhists.

In contrast to this generalized loss of followers of the major religions (

Douthat 2022), increases in other Christians (Evangelical/Pentecostal/Free church/etc.) are also seen in the UK. In the USA, there are two trends: On the one hand, an increase in Buddhism, Judaism, Hinduism, and Orthodoxy and, in turn, a significant increase in Catholicism. However, the low sample sizes of those declared as Buddhists, Jews, Hindus, and Orthodox (13, 22, 7, and 7 cases, respectively, in 2017, and less in the 2005/07-07 measurement) recommends being cautious in generalizing this situation.

A few paragraphs back, it was noted that belonging to religions was a question answered by all respondents, and that approximately half of the sample had indicated ‘do not belong to a denomination’. However, this is a much lower percentage than that observed in the question that began this section (

Figure 4), where 41–40% of French and English respondents said they were religious people, a figure that reaches half of the population in the case of Spaniards, and 55% in the case of Americans.

This implies that, at least in the case of France and the United Kingdom, the declaration of belonging to a religion may be higher than the reality. In other words, it is a process of “religious disaffection” insofar as the respondent approached it for various reasons, but does not currently follow or, at least, does not consider himself sufficiently religious to follow the precepts of the religion in which he started. This is the phenomena analyzed by Grace Davie in Great Britain: Believing without belonging (1994). In interpreting this fact, it should always be borne in mind that 24% of the French consider themselves atheists, and that half of the residents of the United Kingdom do not consider themselves religious people (

Figure 4).

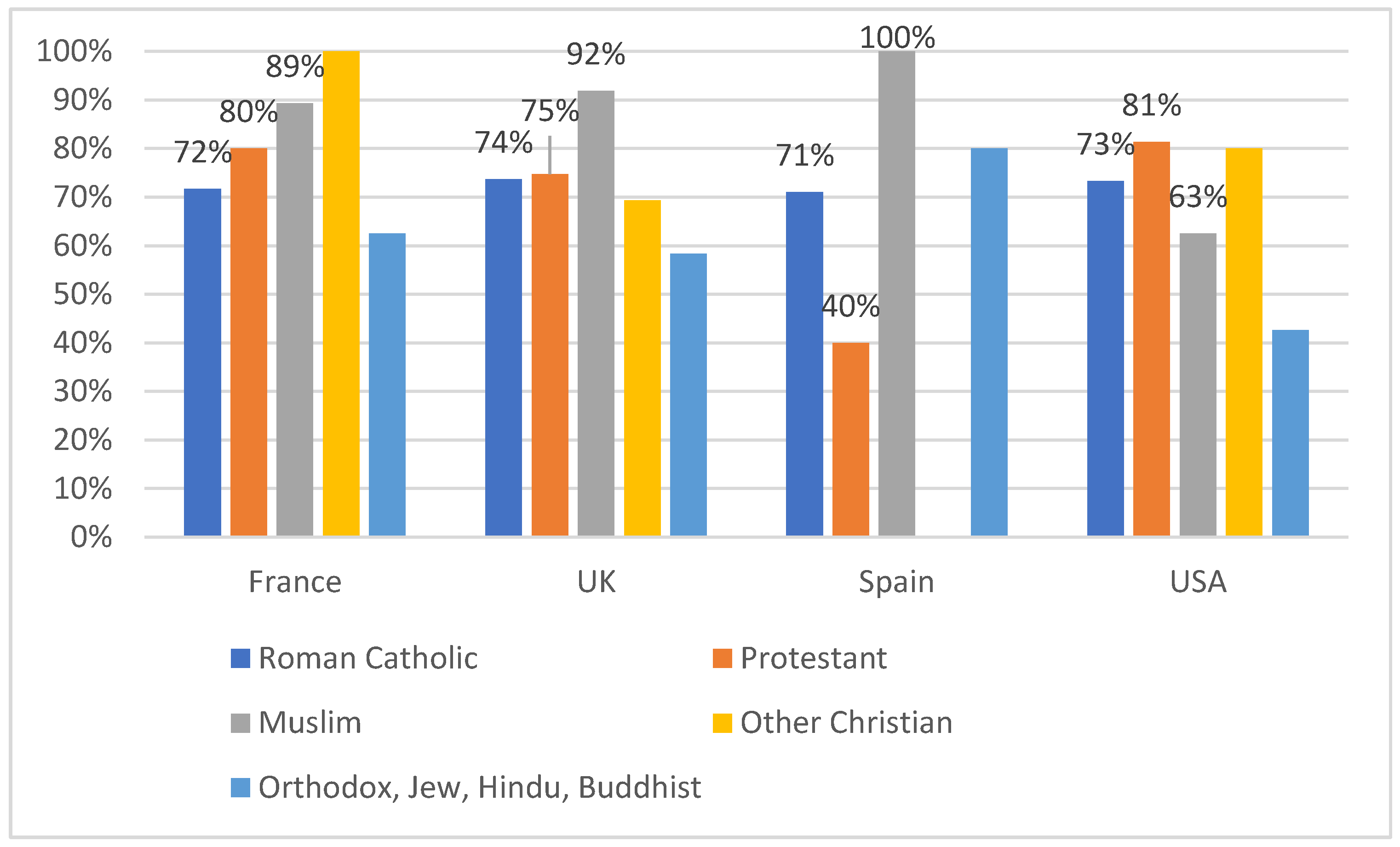

These reasons lead to the construction of a new figure with the (self-considered) religious people who follow each of the faiths (

Figure 10). It should be noted that the percentages do not add up to 100; that is, 72% of the French in Roman Catholic indicate that 28% (100 − 72) of those who have declared themselves to be Catholic do not consider themselves to be religious persons or are convinced atheists. In other words, the space in the figure that is “missing” up to the top is the space occupied by atheists and those who do not consider themselves religious people.

Proceeding with the interpretation, the analysis of religions in each country clearly shows the “high bar” of Roman Catholics in all countries, which indicates that approximately 28% of respondents were initiated by their parents in this creed, but do not currently follow its precepts. The United Kingdom and USA show higher percentages than Mediterranean countries. Protestantism presents a slightly better situation (fewer cases of non-religious) in the case of France and—primarily—in the USA; the situation worsens in the United Kingdom (a percentage similar to Roman Catholicism) and even more in Spain: 60% (100 − 40) of the declared Protestants are not religious people.

Muslims present the highest bars in the figure, which implies a low number of “non-religious” people among their ranks, at approximately 10% on average. This figure disappears in the case of Spain and increases notably among North Americans, where slightly less than half (47%) are non-religious.

In summary, approximately one in four respondents of the most widespread religions do not follow their precepts, a percentage that ranges from 28% in the case of declared Roman Catholics to 22% among Protestants.

As in the case of religious denomination, a sociodemographic profile will be made of the followers of the main religions in each country, i.e., Roman Catholics in the case of France, Spain, and the United States and Protestants in the United Kingdom. Protestants in the United States will also be considered because of their large presence, slightly less than the number of Catholics. It should be noted that only respondents who declare themselves to be religious persons have been considered, excluding self-declared non-religious persons and atheists (

Figure 4 shows the percentages of each). The results are presented in

Table 5, limited to presenting the odds ratios, which are the exponents of the coefficients

11.

The analysis of the information in

Table 5 shows that of the six variables considered, only two show an influence on the two religions, to which is added origin in the United States. With regard to the Catholic religion, it is clear that women and those over 64 years of age consider themselves more religious than men and young people. This is the case in all three countries considered, although the figure for sex is lower in the case of the United States and the influence of age is notably higher than in the two European countries. These values are almost double that of France, and the latter is double that of Spain, which indicates that in the latter country, the influence of age is much lower than in France and the USA. In any case, native/immigrant origin is the most important variable in the case of the United States, with immigrants having a greater affiliation to the Catholic religion.

With regard to Protestantism, the situation in the United Kingdom is very similar to that presented in Spain with the Catholic religion, with a greater belonging of women and those over 64 years of age, the latter with not very high coefficients. In the United States, the influence of sex disappears and two new variables emerge: Native/immigrant origin and educational level. Age is the variable with the highest coefficients; as it increases, Protestantism increases, in line with the educational level. With respect to origin, being born in the United States implies a greater adherence to the Protestant religion, in line with the findings of other experts (

Glascock 2023).

The present section, dedicated to the self-description of the level of religiosity, reveals that 47% of the residents in the countries under study consider themselves religious, 39% as non-religious, and 15% as convinced atheists, figures that change considerably when we take into account the specific characteristics of each country: Greater religiosity in the United States and Spain, expressed by more than half of the population, a high number of non-religious people in the United Kingdom (48%), and 24% of the French population declaring themselves convinced atheists. The temporal evolution of the phenomenon reveals a slight increase in the number of religious people in the case of Spain (6%), which is an exception to the large decline in the United States (the most religious country), and a milder decline in the other two countries considered. The fall in religiosity in France leads to a greater number of atheists, with the “non-religious” response increasing among respondents in the United Kingdom. The most important sociodemographic variables in the self-definition as a religious person is the fact of having been born–or not–in the country where one resides.

Next, we proceeded to analyze religious affiliation, after finding that 50% of those interviewed do not consider themselves to be linked to any religion. Catholicism appears as the main religion in three of the four countries, a figure that rises to 62% among Spaniards and 80% in the case of the French. In the United Kingdom, Protestantism is shared by less than half of the population (45.6%), and in the United States, Catholicism, the predominant religion, is 6% higher than Protestantism. Moreover, 11% of the French are Muslims, a figure that drops to 8% in the United Kingdom and 3% in Spain. An evolutionary analysis over the last ten years reveals a decline in the major religions, primarily Catholicism in Spain. The study of sociodemographic traits that influence whether one is a member of the Catholic or Protestant religion—in each country where it is the religion with the most followers—reveals the influence of the age and sex of the respondent, as well as the native/immigrant origin in the United States.

3.3. The Sphere of Beliefs

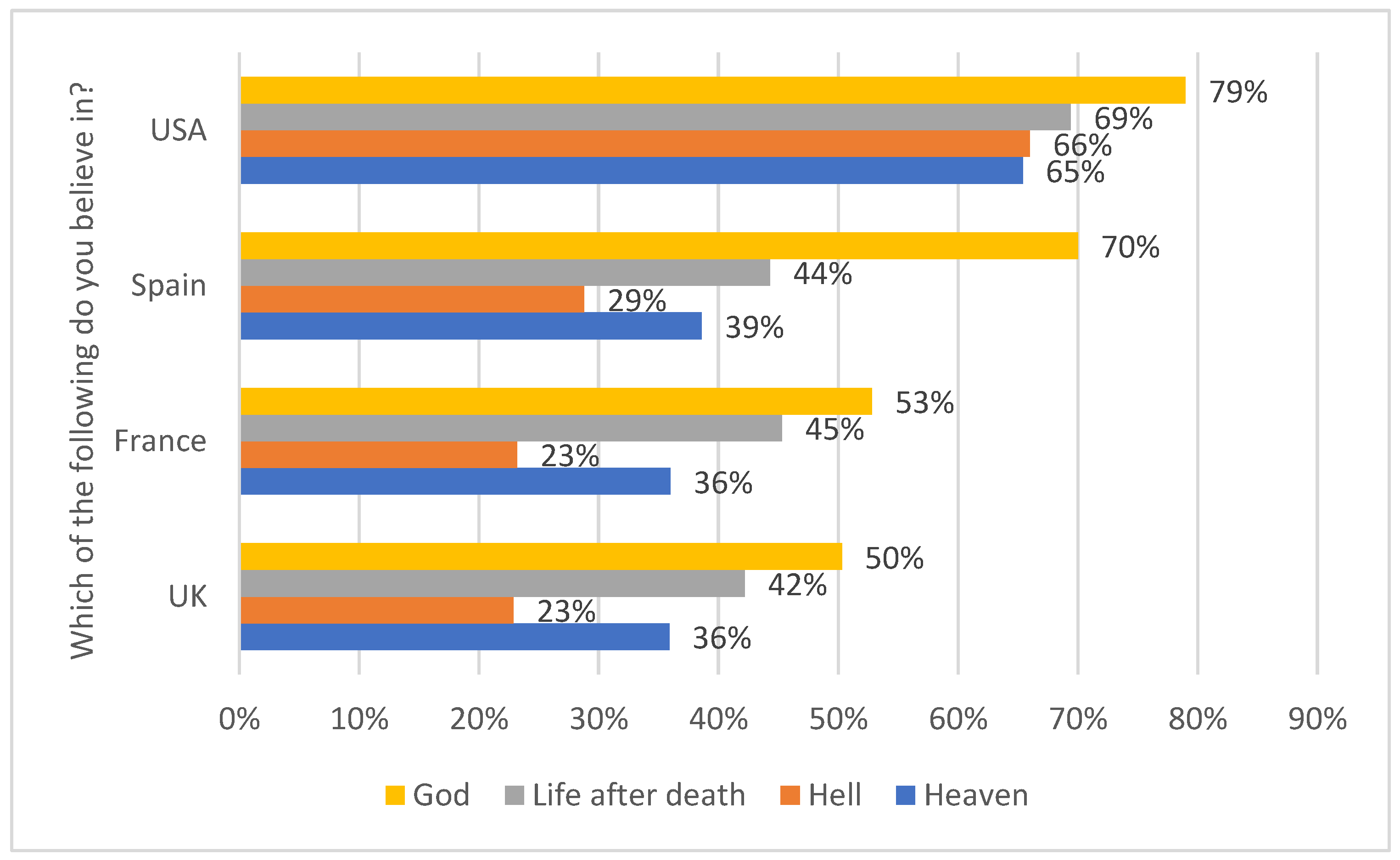

This section is articulated around four dimensions: Belief in God, life after death, hell, and heaven. Of those interviewed, 63% said they believed in God and 3.2% did not know what to answer; 51% believed that there is life after death and 7% did not know; 35% said they believed that hell exists and 5% did not answer; and 44% believed that heaven exists with the same number of non-responses.

The country-by-country analysis shown in

Figure 11 reveals, in the first place, the high levels of belief in these aspects in North American society, where eight out of ten believe in God, ten percentage points less in that there is life after death, and two out of three respondents believe that heaven and hell exist. Spain is the second country in terms of the level of belief, with seven out of ten believing in God, and slightly less than half of those interviewed (44%) believing that there is life after death. Belief in the existence of heaven and hell are lower, at 39% and 29%, respectively. In France and the United Kingdom, belief in God is reduced to half of the population, although the latter has a slightly lower belief in God and in the existence of life after death.

Let us analyze each dimension.

3.3.1. Belief in God

The survey conducted in 2017 specifically asks about the importance of God in the life of the respondents, posing to the respondents a graphical aid with a scale in which the far left shows 0 and a label stating ‘not important at all’, and on the far right appears 10 and a label with ‘very important’ (see

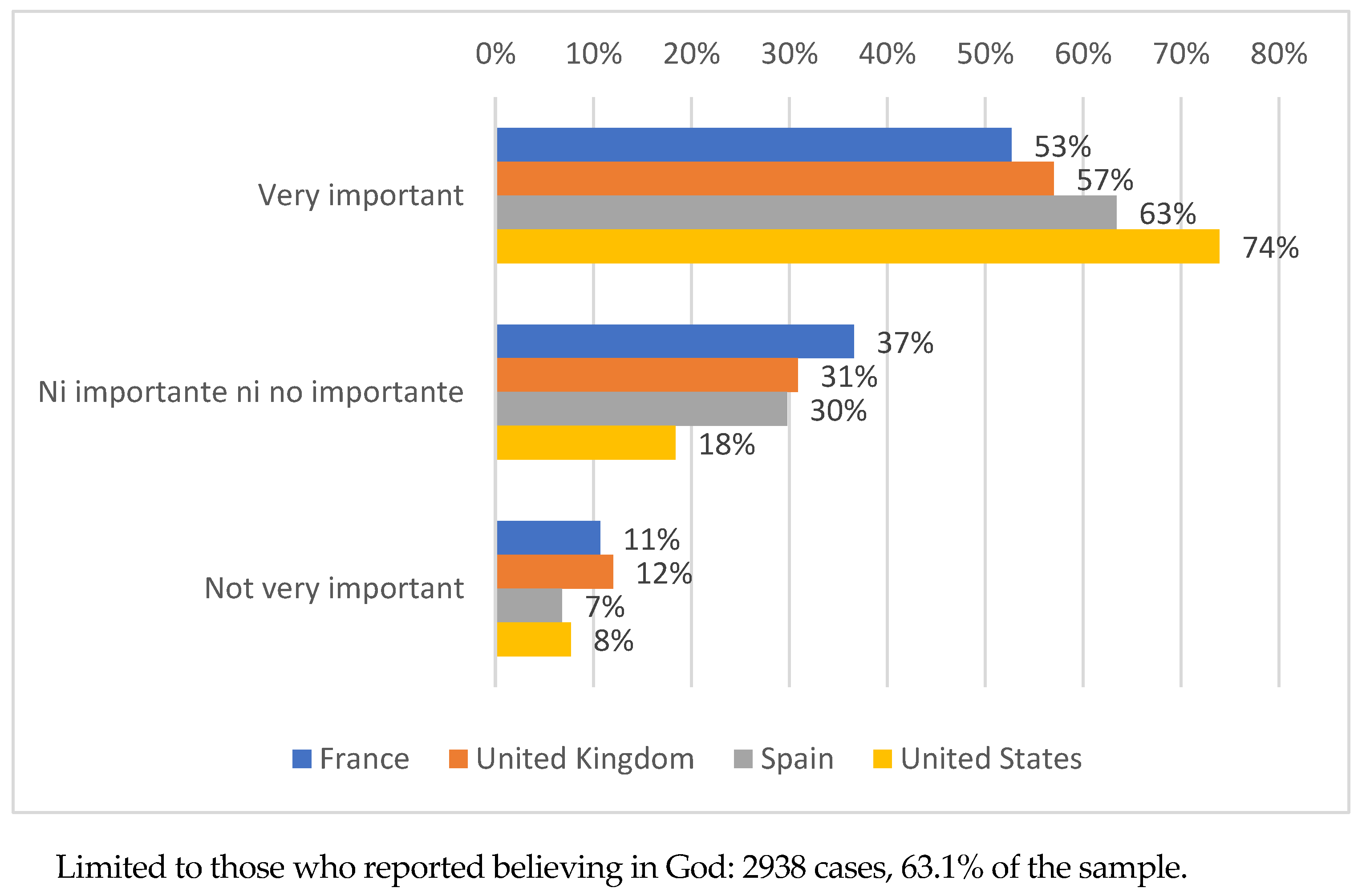

Appendix C). We have chosen to consider the answers to this question only for those who believe in God, since it does not seem appropriate to ask about the importance of God to those who state that they do not believe in him, since their importance in life will be very low or null. Although the analysis can be carried out considering the average scores of each country (France with 6.74, the UK with 6.94, Spain with 7.07, and the USA with 8.03, always considering this scale from 0 to 10), it seems more interesting to carry out a categorization of the evaluations by joining answers 0, 1, 2, and 3 and considering them as ‘not at all important’ and answers 7, 8, 9, and 10, which define God as ‘very important’. In the middle are answers 4, 5, and 6 expressed by those who consider God in their life as ‘neither very important nor unimportant’. Thirty-eight percent of those interviewed stated that God is very important in their lives, slightly higher than those who stated that He is not (40%). The country-by-country analysis will nuance these results (

Figure 12).

Three out of every four Americans (who believe in God) recognize that God is very important in their lives, a fact related to the high percentages of religious people (more than half of the population, as shown in

Figure 4). In the case of Spain, this percentage drops eleven percentage points, seventeen in the case of United Kingdom, and twenty-one among French citizens, who are also the residents who express the highest intermediate scores (37%). It is surprising that approximately 10% of those who believe in God consider him to be of no importance in their lives, a percentage that increases in France and the United Kingdom and decreases in Spain.

The non-existence of these questions on beliefs in the 2005/07 measurement makes it necessary to change the order of presentation with respect to the previous headings, proceeding directly to the analysis of the sociodemographic characteristics of the respondents who believe in God, which is shown in

Table 6.

As for independent terms with a significant influence on belief in God, sex, age, educational level, and the fact of not having been born in the country appear, with the latter showing the highest coefficients, and very high in the case of the United Kingdom. There are three exceptions to this general trend: No influence of educational level in the United Kingdom and being born abroad in the USA, as well as the influence of being part of the working population in the case of Spain. The interpretation of the coefficients reveals a greater belief in God in those who were born abroad (with a high influence in the United Kingdom and none in the USA), in those over 64 years of age (France presents the highest magnitude), in respondents with low levels of education (with high magnitudes in Spain and the USA), and in women, much higher in the case of the USA.

The great influence of the fact of being a native or immigrant makes it advisable to look at whether there are differences between the immigrant group, or whether first- or second-generation immigrants believe in God in the same way.

Figure 13 provides an answer to this concern, always showing a greater belief in God among first-generation immigrants, with differences of 40 percentage points in the case of those interviewed in Spain, almost twenty (18%) in the French, and eleven in the case of residents of the United Kingdom. There is no significant difference in the case of residents of the United States, which would recommend eliminating this country from

Figure 13, although we have opted to leave it in order to contextualize the differences in the four geographic areas under study.

Once the influence of the sociodemographic variables on belief in God has been exposed, it seems relevant to know—because of its importance—the relationship of this belief with the religious denomination and the fact of belonging or not to a religion. The information presented in

Figure 14 shows the great importance of both variables. The percentage of believers in God, which, as shown in

Figure 11, in France and the United Kingdom was approximately 50% (53% in France and 50% in the UK) rises to 72% among those who call themselves religious, an increase much higher than in Spain, which barely increased by 4%. The trend in the USA is disconcerting, where belief in God decreases among those who consider themselves religious and increases among those who call themselves non-religious.

It is more interesting to focus attention on the right-hand side of the

Figure 14, which reveals that approximately 29% of the non-religious believe in God, a percentage that drops to 27% in the case of Spaniards.

In the lower part of

Figure 14, belief in God is analyzed with the response ‘do not belong to a denomination’ in the question regarding the religion to which they belong. The situation in the UK and the USA is surprising, with a high belief in God among those who declare that they do not belong to any religion: In the UK, one-third of those who do not belong to any religion believe in God, far exceeding the average of non-believers who believe in God (28%). The trend is higher in the USA, where belief in God in this group rises to 37%.

Spain presents the opposite situation, where the percentage of believers in God who do not belong to a religion is reduced to half the average (13%), thus generating an equivalence between belonging to a religious denomination and believing in God.

It is important to note that when both concepts are included as independent terms in the regression shown in

Table 6, the explanatory capacity of the model increases notably: R

2 values of 0.60, 0.58, 0.7, and 0.5 in France, the United Kingdom, Spain, and the USA, respectively, with approximately 85% of cases correctly classified (reaching 90% in Spain). Another important finding is that the influence of practically all the sociodemographic variables disappears, with the exception of educational level in Spain and the USA, and sex in the latter, with religious self-identification being the variable that most explains belief in God, followed by belonging or not to a religion and, at a great distance, the fact of being born in another country. Those who call themselves religious people, were born in a different country, and belong to a religion believe in God more than the rest of the interviewees (in order to make the reading more fluid, this table has been placed as a table in

Appendix D).

3.3.2. Belief in Life after Death

Regarding the belief of whether there is life after death, something shared by 51% of the interviewees, in

Figure 11 we can observe the strong belief of the residents of the United States, as opposed to the skepticism of Europeans. Sixty-nine percent of those interviewed in North America believe in this idea, a number that drops to 42% among residents of the United Kingdom. The Spanish and French are close behind, 44% and 45%, respectively.

As was stated in the case of belief in God, given the impossibility of knowing the evolution of this belief in recent years (since this question was not asked in the fifth wave of the survey), we will proceed to present the sociodemographic characteristics of the respondents who believe that there is life after death, the results of which are presented in

Table 7.

The analysis of these traits is in line with those shown in

Table 7 regarding the low explanatory power of the models. However, the variables of influence are notably different, with a loss of influence of educational level in all countries, age in all countries except France, and the fact of belonging or not to the working population, which only shows influence in the case of Spain. In North America, only the sex of the respondent had a significant influence. In the three European countries, the importance of the immigrant/non-immigrant origin of the interviewees can be appreciated, with non-natives being those who show a greater belief in the existence of life after death, an idea also shared by women in the four countries. In France, interestingly, it is the youngest respondents who believe more that there is life after death.

Unlike what happened previously (

Figure 6 and

Figure 13), in this case, there is no relationship between the type of migrant—in terms of generation—and the belief in life after death.

Following the same expository logic used for belief in God, we now proceed with the analysis of the influence of religious denomination and belonging/not belonging to a religion. The first part of

Figure 15 reveals a notable increase in the belief in life after death among religious Spaniards, with Americans at the average. Two out of every three French and English people who consider themselves religious believe that there is life after death, a percentage that affects three out of every four Spaniards. It is the residents of Spain who experience the greatest growth, 31 percentage points higher than the marginal percentage, as opposed to the stability of the Americans, who do not change when religious denomination is considered.

It is also surprising that 35% of English people who do not consider themselves religious believe that there is life after death, an opinion also shared by 29% of non-religious Americans. Another interesting aspect is that 11% of French atheists believe that there is life after death, which is in stark contrast to the statement of atheists. When aggregated, 37% of non-religious people in France believe that there is life after death, a percentage similar to that of the United Kingdom.

The second part of the figure, relating to religious affiliation, shows similar results in the French and Americans, increasing in UK society and decreasing notably in the Spanish. Forty-one percent of the English who declare that they do not belong to a religion believe that there is life after death, a percentage similar to that of the English and Americans. The large drop in Spanish society is surprising, 20 percentage points lower than the marginal percentage shown in

Figure 11.

As happened in the case of belief in God, when these variables are introduced into the regression model as independent terms, the explanatory power of the model increases notably

13, completely altering the significances shown in

Table 8. In all four countries, religious denomination is the most influential variable in belief in life after death, followed by age and sex in all countries except Spain. Being a native or an immigrant and not belonging to any religion are the next most influential aspects. In Spain and England, the influence of being a native or immigrant disappears.

Those who most believe that there is life after death are self-described religious people, those under 30 years of age (belief in this aspect decreases as one grows older), women, those born outside the country where they live, and those who indicate that they do not belong to any religion (not shown).

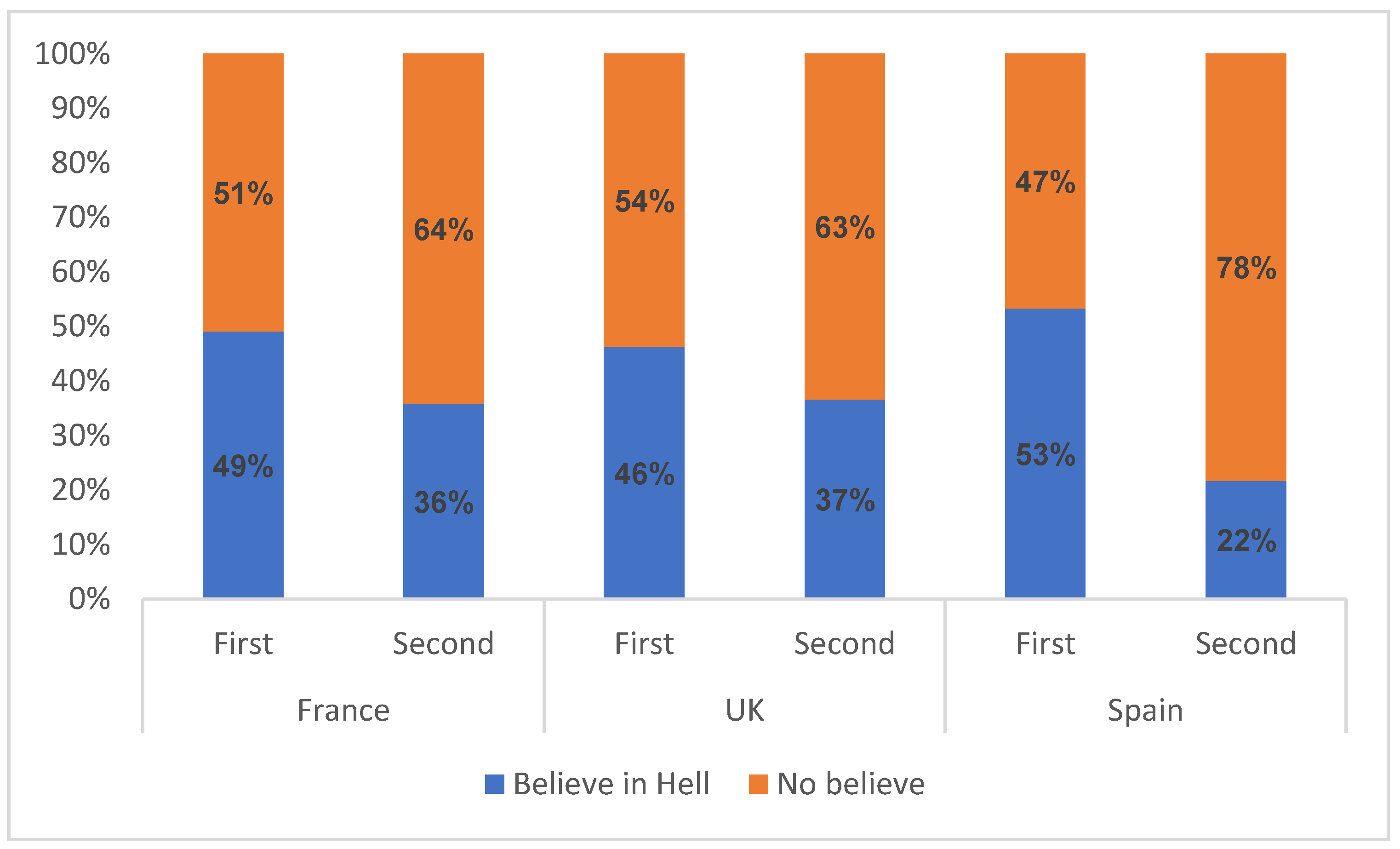

3.3.3. Belief in Hell

Belief in the existence of hell is the third aspect considered within the sphere of beliefs. Moreover, 35% of those interviewed believe in its existence, an opinion shared by 66% of U.S. residents. Follow-up to this belief is scarce in European countries, primarily in France and the United Kingdom, where 23% of those surveyed believe in the existence of hell (

Figure 11). This percentage increases slightly in the case of Spaniards, who reach 29%.

The analysis of sociodemographic traits by means of logistic regression does not present major differences from that found in

Table 6 regarding belief in God. To the great importance of native–immigrant origin in European countries, not in the United States, we add the influence of the sex of the respondent (women believe in hell more than men), age in France, and the fact of not belonging to the working population in Spain. As was the case for life after death (

Table 4), there is a linear relationship between age and belief in hell, where young people are the highest believers, and the same is true for those who are not active.

Again, there is a difference between first- and second-generation immigrants with respect to belief in hell in European countries, but not in the United States, where Spain presents the greatest differences: More than 53% of first-generation immigrants believe in hell, a figure that plummets to half among second-generation immigrants (

Figure 16). The differences between the two groups are smaller in France and the United Kingdom, with 13 and 9 percentage points, respectively.

Religious denomination, as in the rest of the beliefs, implies large changes in terms of belief in hell, which is in the majority among those who consider themselves religious people. Three out of four religious people believe in the existence of hell, a percentage that reaches 88% in the case of Spain (

Figure 17). In other words, the percentages for European countries triple when we look specifically at people who declare themselves to be very religious. On the other hand, 27% of North Americans who do not consider themselves religious people believe in the existence of hell, five points higher than those in France and the United Kingdom.

The percentages of belief in the existence of hell increase notably when one considers those who do not belong to a religion. Thirty percent of French and English residents who believe in hell without belonging to a religion rises to 36% of U.S. residents.

Introducing these variables in the regression model shown in

Table 8 again produces significant increases in the explanatory power of the models (0.34 in France, 0.30 in the UK, 0.39 in Spain, and 0.382 in the USA), and important changes in the independent variables. The native/immigrant origin of the respondent loses importance, and the variable with the greatest explanatory power is religious denomination. In France and England, these are accompanied by age and the fact of not belonging to any religion, while in Spain, educational level is incorporated, and in the United States, it is educational level, age, and sex.

As with the belief in life after death, those who most believe that hell exists are self-described religious people (6.5 times more than the non-religious in France), those under 30 years of age (belief in this aspect decreases as one gets older), those born outside the country where they life, and those who indicate that they do not belong to any religion.

3.3.4. Belief in Heaven

The analysis in

Figure 11 already revealed that the 44% who say they believe that heaven exists increases notably in the United States, where 65% believe in its existence, significantly surpassing European countries, whose percentage of believers ranges from 39% of Spaniards to 36% of the English and French. In any case, belief in the existence of heaven exceeds belief in hell in European countries, with a difference of thirteen points in the case of the French and English and ten points among Spaniards. There is hardly any difference in the case of North Americans, and the percentages of belief in heaven are very similar to belief in hell (65% and 66%, respectively).

The analysis of socio-demographic characteristics, which we will not present here so as not to overwhelm the reader with so much data, shows an influence of the sex of the respondent in the four countries, revealing that women believe in heaven to a greater extent than men. Age influences Spaniards and Americans, with belief in heaven increasing as the age of the interviewees increases. Educational level has an influence in all four countries, with respondents with low education showing the highest level of belief in the existence of heaven, with native–immigrant origin being the most influential variable in European countries, but not in U.S. respondents.

We can observe a significant relationship when we look specifically at first- and second-generation immigrants in France. Moreover, 67% of first-generation immigrants believe in the existence of heaven, a percentage that drops to 49% among children of French immigrants.

Figure 18 shows the great impact of religious denomination on belief in the existence of heaven, which reaches 87% of the Spanish population, remaining at almost three-quarters of the population in the rest of the countries, percentages similar to the belief in the existence of hell presented in

Figure 17. In any case, more than 25% of the non-religious respondents believe in the existence of heaven, a percentage that reaches 30% in the case of residents of the United Kingdom.

As on previous occasions, the results at the bottom of

Figure 18 are more surprising since 35% of U.S. residents who do not belong to a religion believe in the existence of heaven, slightly lower percentages than residents in the United Kingdom (34%) and France (32%). We do not refer to the changes in the regression model when the variables in

Figure 18 are introduced because of the coincidence of the situation shown by the belief in hell.

To summarize, of the four beliefs considered, belief in God is the one with the most followers, at approximately 63% of the population, reaching 79% and 70% in the United States and Spain, respectively. Half of those interviewed believe that there is life after death, a figure that reaches 69% of North Americans, and approximately 44% in European countries. Forty-four percent say they believe in heaven, a figure that rises to 65% in the case of U.S. residents and drops to 36-339% in European countries. The existence of hell is the least reported, by approximately one-third of the population, dropping to 23% for residents of France and the United Kingdom.

Gender, age, educational level, and not being born in the country are the independent terms with significant influence on belief in God. The influential variables in the belief in life after death show some differences, with a loss of influence of educational level in all countries, age in all countries except France, and the fact of belonging or not to the working population, which only shows influence in the case of Spain. In North America, only the sex of the respondent had a significant influence.

As for the explanatory traits in believing in hell, to the great importance of native–immigrant origin in European countries, but not in the United States, we add the influence of the sex of the respondent, age in France, and the fact of belonging to the labor force in Spain. Finally, the analysis of the sociodemographic characteristics of those who believe in heaven shows an influence of the sex of the respondent in the four countries, age in Spain and the United States, educational level in the four countries, and native–immigrant origin in the European countries. In any case, the variables with the greatest influence on the four beliefs are self-identification as a religious person and belonging or not to a religion.

3.4. Scope of Practices

It should be recalled that the organization of this article follows the classification scheme known as “the three B’s”, which allude to (religious) belongings, (religious) belief, and (religious) behavior; that is, belonging to a religious denomination, belief in shared dogmas, and common behaviors. Having dealt with the first two, it is time for the third, which specifically focuses on the habitual frequency with which religious services are attended, that is, excluding “special” situations such as weddings and funerals, as well as the frequency with which prayers are said.

This question is posed to the respondent showing a figure aid with the possible answers, which are ‘Several times a day’, ‘More than once a week’, ‘Once a week’, ‘Once a month’, ‘Only on special holy days’, ‘Other special holy days’, ‘Once a year’, ‘Less often’, and ‘Never, practically never’. Due to the low number of responses to the categories ‘Other special holy days’ and ‘Once a year’, they have been grouped with their contiguous category, thus forming two categories called ‘Only on holy days’—the result of adding ‘Only on special holy days’ and ‘Other special holy days’—and ‘Once a year & Less often’. This situation, coupled with the fact that no one answered ‘Several times a day’, leads to reducing the question from nine categories to six, which makes it more manageable.

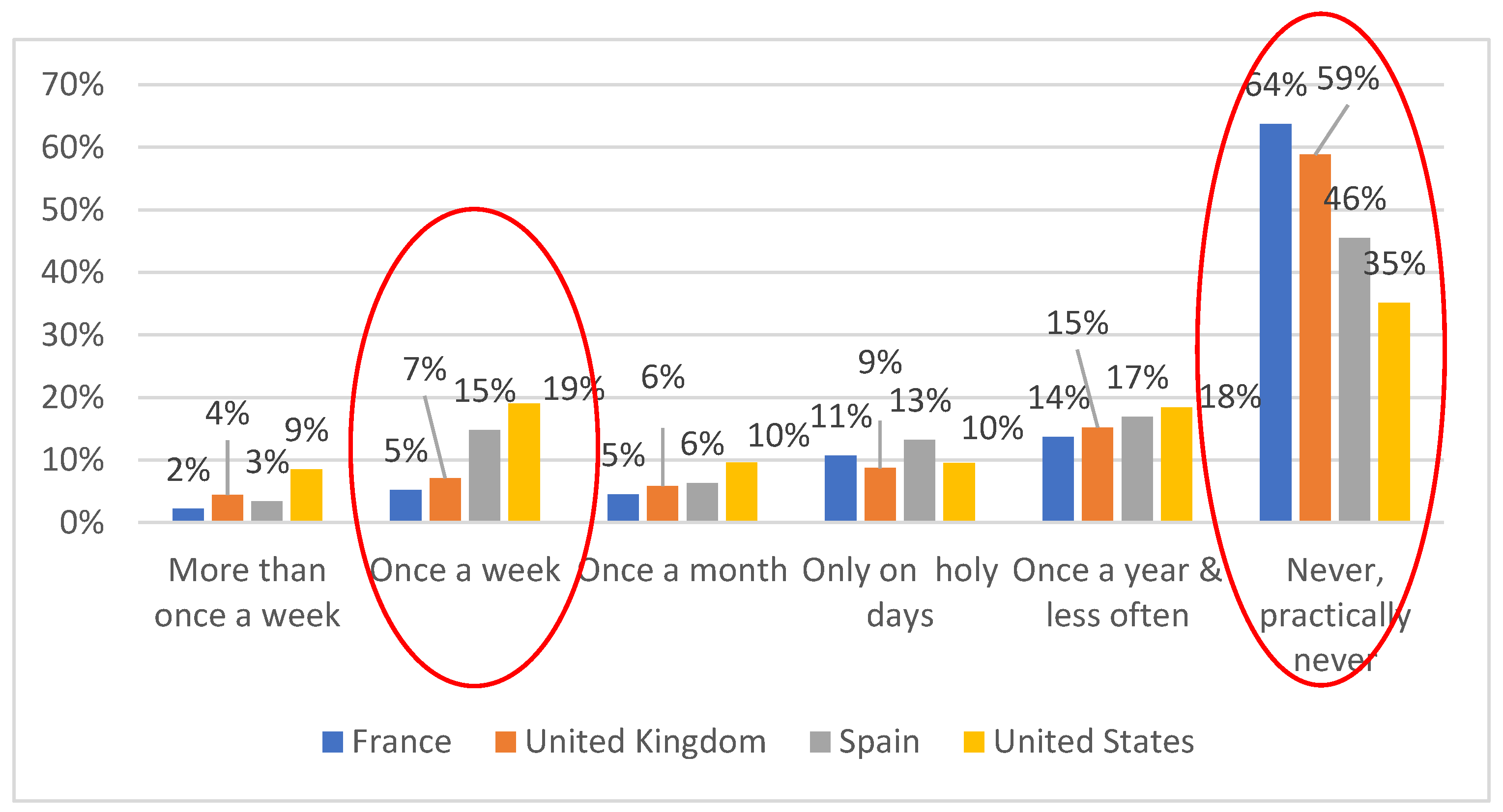

Half of the respondents never attend religious services, and 16% attend once a year or less. The responses shown in

Figure 19 qualify these responses by country, indicating that two-thirds of French respondents never attend religious services, a percentage that is reduced by 29 percentage points for U.S. residents. Almost one in five (exactly 18%) UK residents attend once a year and less frequently, and Spaniards stand out as having the highest rate of church attendance on “holy days” (Christmas, Easter, etc.).

Also noteworthy is the weekly frequency, reported by 15% Spaniards and 19% of North Americans, tripling the frequency of residents of the United Kingdom (7%) and even more so of the French (5%).

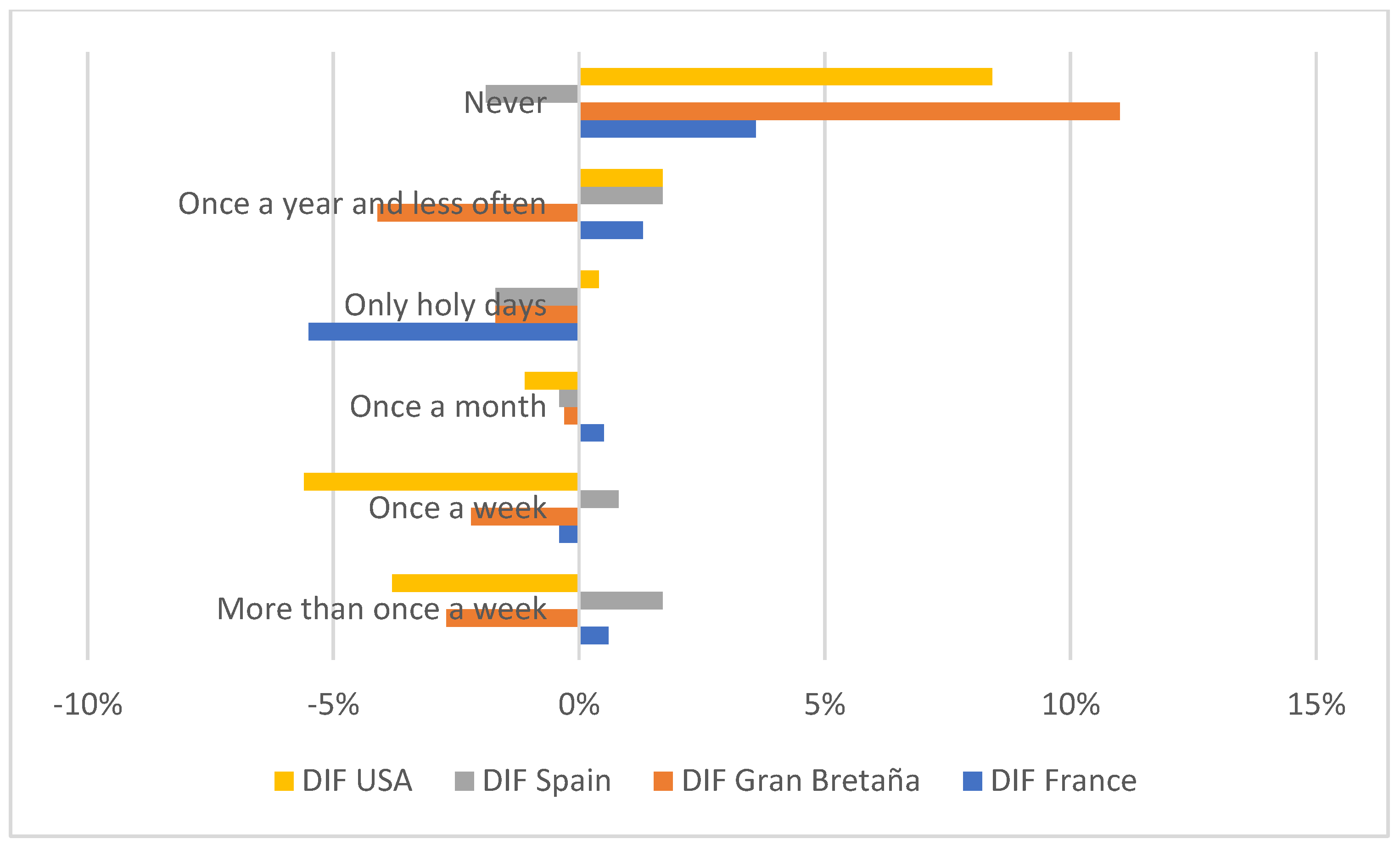

This low attendance at religious events is not new, as those who never attend increased just 5 percentage points between 2005/07 and 2017, amounting to 11% in the UK (and 8% in US residents).

Figure 20 shows the decrease in weekly attendance and more than one day a week in Americans, with six and four percentage points, as well as the decrease on public holidays (holy days), primarily in French respondents (6%).

It could be the case that religious practice was different according to religious denomination, something that is not ascertained by performing the consequent relationship between variables (not shown). For profiling, in line with what is shown in

Table 4,

Table 5,

Table 6,

Table 7 and

Table 8, we used a logistic regression to study the traits associated with low participation in religious services, which provides a very low adjustment, but also a consistency between countries. Non-attendance at religious services is higher among natives, those with high levels of education, and those in the labor force, although Spain also adds age, which indicates that young people have the lowest attendance at religious services.

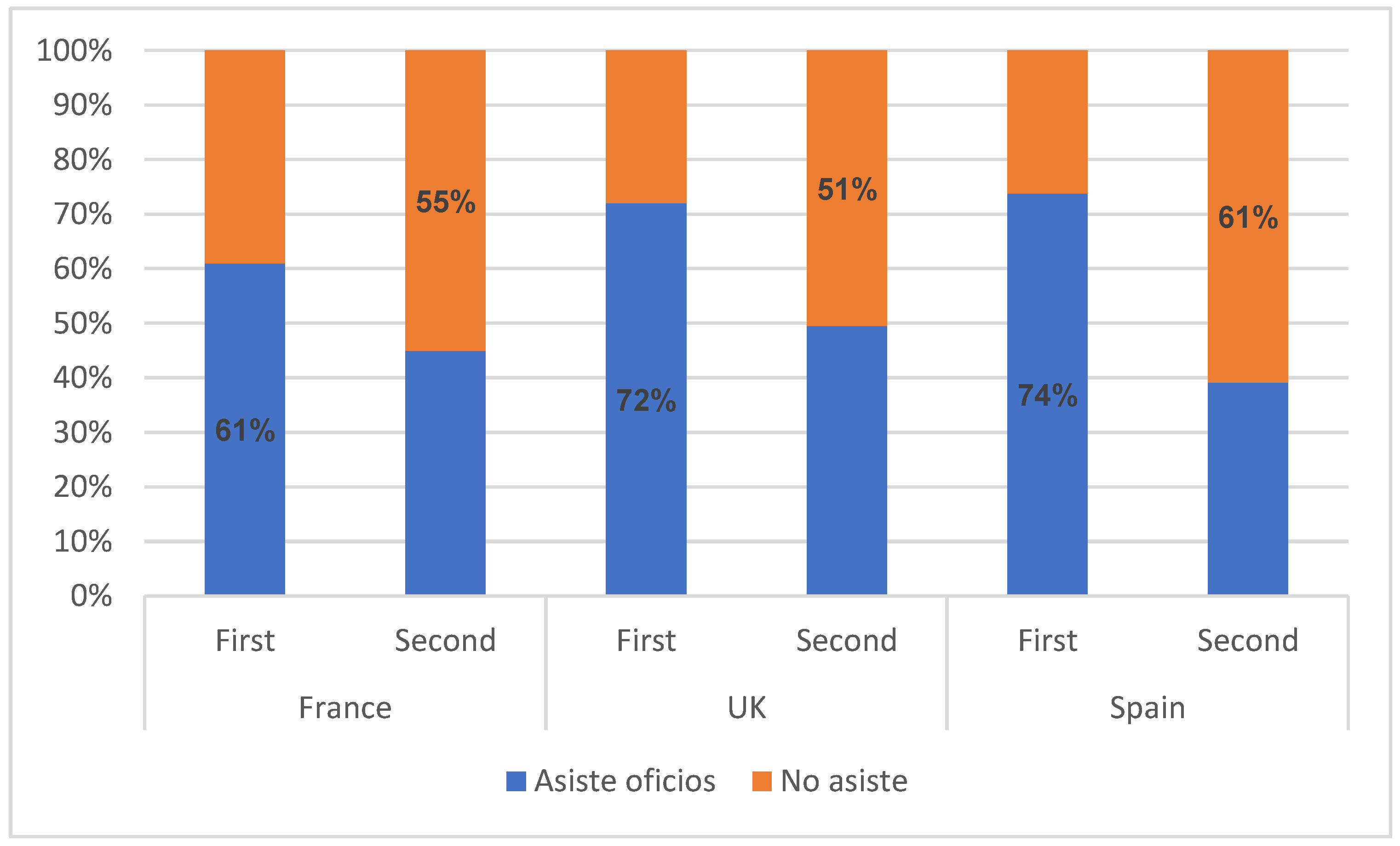

We do not refer to the changes in the regression model when the variables in

Figure 18 are introduced because of the coincidence of the situation shown by the belief in hell. Within the group of those not born in the country of residence, there is a large difference between first- and second-generation immigrants, with the latter attending fewer religious services, as shown in

Figure 21. In Europe, more than half of second-generation immigrants do not attend religious services, reaching 61% in Spain. Respondents from the United States again show no difference in this regard.

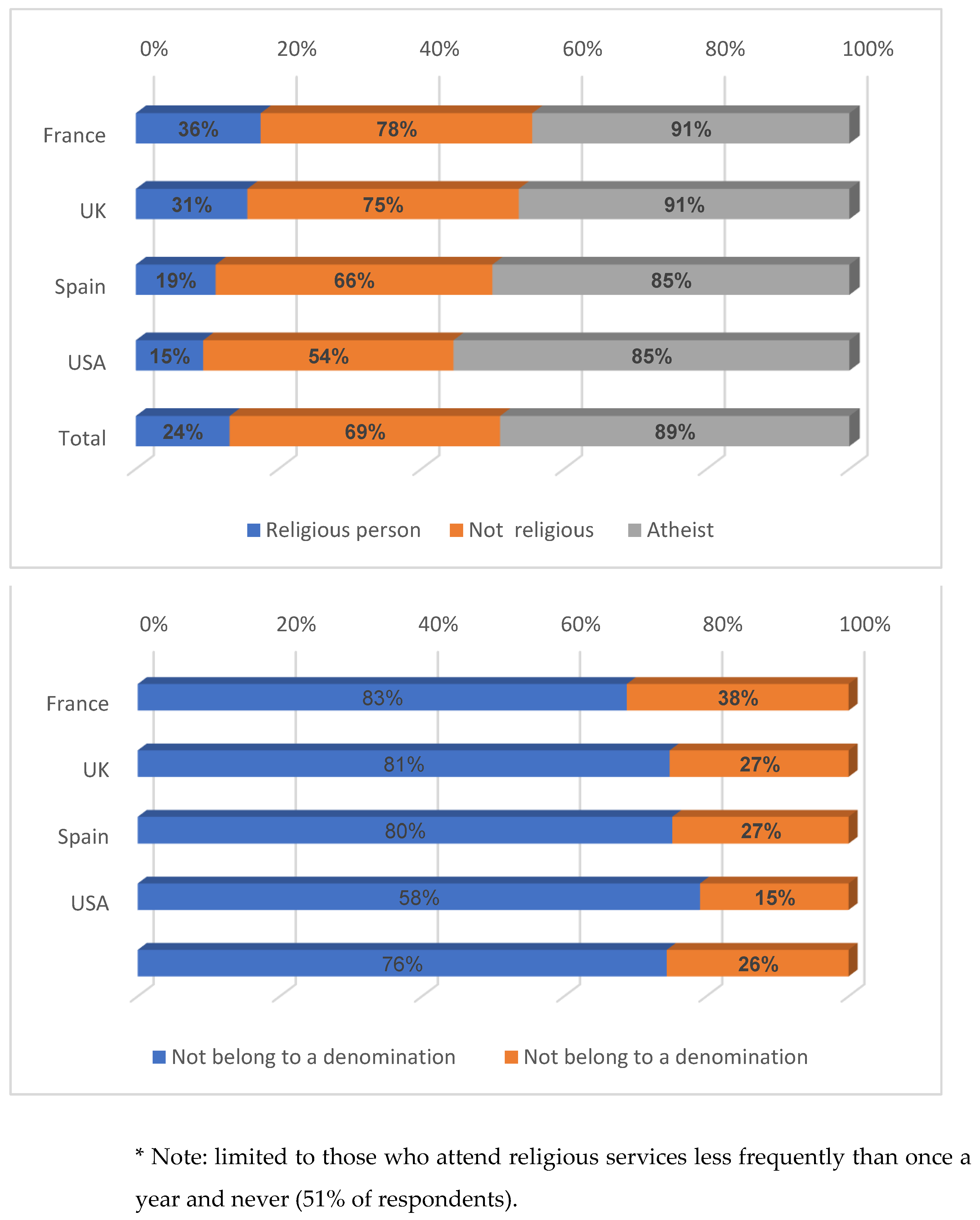

As in the previous section, we analyze the relationship between non-attendance at religious services (never and practically never) with religious denomination and whether or not one belongs to a religion (

Figure 22). Surprisingly, we can observe low attendance at religious services among those who consider themselves religious at 24%, which rises notably to 31% among respondents in the United Kingdom and 36% among residents of France, dropping to 15% in the middle among North American respondents.

As for those who say they belong to a religion, at least one in four Europeans hardly attends religious services at all, a figure that rises to 38% in the case of France. North American respondents, as usual, are the ones who attend the most, and only 15% of those who declare a religious denomination do not attend services. The percentages in the second part of

Figure 20 are surprising, but it should be borne in mind that within the category of “belonging to a religion”, there are people who—as we have already seen—have abandoned their precepts.

Within the group of those not born in the country of residence, there is a great difference between first- and second-generation immigrants, with the latter attending fewer religious services, as shown in

Figure 23. Respondents from the United States again show no difference in this regard.

Within the group of those not born in the country of residence, there is a large difference between first- and second-generation immigrants, with the latter attending fewer religious services, as shown in

Figure 23. Respondents from the United States again show no difference in this regard.

The second element included in the practices is the frequency of prayer, which reveals that 48% never do it, 12% less than ‘several times a year’, and 16% every day, representing the highest results.

Figure 24 presents the differences in the frequency of prayer among European countries since this question was not included in the North American survey and therefore it is not possible to know its distribution. This figure shows the increase in the number of people who never pray in France, which reaches 57% of those interviewed, as well as in the United Kingdom, where the percentage of people who never pray is just over half of the population. In the analysis of the columns on the left, where those who pray every day appear, it is again the French who pray the least, followed by the residents of the United Kingdom. Approximately 20% of Spaniards pray every day.

It is not possible to compare these results with the 2005/07 wave because, at that time, it was presented in a dichotomous form, whether or not they pray (59% and 41%, respectively) and, moreover, it was only asked in Spain and the United States.

The results of those who pray the least are shown in

Figure 24, which reveals that approximately 20–25% of religious people hardly pray at all, that is, they pray several times a year, less often, and never. The percentages in the second part of

Figure 25 are surprising, although it should be kept in mind that within the category of “belonging (to a religion)” there are people who, as we have already seen, have abandoned their precepts.

In summary, more than half of the sample consulted never attend religious services, percentages that, in France and the United Kingdom, reach 64% and 59%, respectively.

Figure 21 shows that this is not a new situation insofar as it has only increased by five percentage points in the ten years considered. Grace Davie defined this phenomenon as “believing without belonging” in 1994, in her case, referring to the United Kingdom, but it seems that could be extensible to the four countries considered in present day. In fact, Grace Davie herself warned in 2015 of the persistence of this logic of religious action in the United Kingdom. The study of the profiles associated with low participation in religious offices is related to living or not in the country of birth and educational level. If attendance at religious services is low, the habit of prayer is even scarcer in the European countries. Some 48% never do so, and barely 16% pray every day, with Spaniards being the ones who pray the most.