Christianity Cultivated Science with and without Methodological Naturalism

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodological Naturalism

IMN: Science, as a way of knowing nature, excludes supernatural explanations of nature.

PMN: Because scientists, qua scientists, have evaluated supernatural explanations of nature and found them inadequate, scientists no longer consider supernatural explanations as live options for scientific theory.

Not surprisingly, IMN is typically embraced by philosophers sympathetic to religion, by theistic evolutionists and religious liberals intent on safeguarding an epistemic domain for religious faith…, as well as by atheists who try to disarm the perceived conflict between religion and science…. In a way reminiscent of Stephen Jay Gould’s principle of non-overlapping magisteria (NOMA)…, IMN seems to embody the modern modus vivendi between science and religion.

EMN: Only publicly accessible methods using natural human faculties can justify theories of nature.

To recap, the pragmatic defense is correct that supernatural explanations are testable, have been tested and have often failed in the scientific arena. Yet on the other hand, the pragmatic defense gets wrong the historical claim that methodological naturalism was eventually adopted as a rule of thumb [after the progressive failure of supernatural explanations]. The intrinsic defense also gets something right, insofar as science is a discipline with an explicit, a priori, anti-supernatural bias. But, the intrinsic defense doesn’t square with the observation that science apparently can test and has tested supernatural explanations.(Ibid., p. 327)

Intelligent design—often called “ID”—is a scientific theory which holds that some features of the universe and living things are best explained by an intelligent cause rather than an undirected process such as natural selection. ID theorists argue that intelligent design can be inferred by finding in nature the type of information and complexity which in our experience arises from an intelligent cause.

3. Greco-Roman Thinkers Cultivated Science with and without MN (Mostly without)

If the matter from which the cosmos is formed is sometimes said, as in Plato, to have been pre-existing, that does not entirely “naturalize” the account, at least insofar as divine agency is still responsible for the shape and characteristics of the world. A supernatural entity of one sort or another is clearly interacting with the system, and “the natural order” itself is seen to be non-self-starting. The chain of natural physical causation, that is, is seen as insufficient to explain its own beginning.(Ibid., p. 27)

Where the ancient philosophers who invoke divinities do so, nearly universally, to account for nature’s regularity, complexity, and beauty, the one school we have found to be pure naturalists, the Epicureans, are the one school who allow for just this kind of capriciousness—the random, uncaused swerve—in the cosmos. It may not be a personalized kind of capriciousness (just the opposite), but for all that it is exactly the kind of explanation that “pure naturalism”—if such a thing even exists—was designed to avoid.(Ibid., p. 36)

4. Medieval Christians Cultivated Science with and without MN: Progress, Diversity

Thus says the LORD, who gives the sun for light by day and the fixed order of the moon and the stars for light by night… If this fixed order departs from before me, declares the LORD, then shall the offspring of Israel cease from being a nation before me forever (Jeremiah 31:35–36, ESV).

The term translated here as “fixed order” (NRSV) is the Hebrew word, hoq, meaning a royal decree or law. It is translated as nómos, the Greek word for law, in the Septuagint, and as lex in Jerome’s Latin translation, the Vulgate. The biblical and theological use of these terms played a huge role in the development of the idea of cosmic natural law inherited by modern science.

4.1. Adelard of Bath (ca. 1080–ca. 1150)

I am not slighting God’s role. For whatever exists is from him and through him. Nevertheless, that dependence [on God] is not [to be taken] in blanket fashion, without distinction. One should attend to this distinction, as far as human knowledge can go; but in the case where human knowledge completely fails, the matter should be referred to God. Thus, since we do not yet grow pale with lack of knowledge, let us return to reason.9

4.2. Peter Abelard (1079–1142)

When we now seek or assign a force of nature or natural causes in any outcomes of things, in nowise do we do it according to that first work of God in the disposition of the world, where the will of God alone had the power of nature in those [things] then to be created or arranged; but only after the work of God completed in six days. We usually identify a force of nature in the aftermath, when those things are in fact already so prepared that their constitution or preparation would be enough to do anything without miracles. Hence we say that those things which occur though miracles are rather against or beyond nature than according to nature, since that former preparation of things could not suffice for doing it, unless God were to confer some new power on these things, just as he was also doing in those six days, where his will alone worked as the force of nature in each thing to be made. If indeed he were also to work now [miraculously] as he did then, we would say at once that this is against nature, as for instance if the earth were spontaneously to produce plants without any sowing [of seed].… Hence we call nature the force of things bestowed on them since that former preparation, sufficient thenceforth for something to be born, that is, to be made [non-miraculously].10

4.3. Boethius of Dacia (Late 13th Century): Did the Universe Have a Beginning?

IMN: Science, as a way of knowing nature, excludes supernatural explanations of nature.

PMN: Because scientists, qua scientists, have evaluated supernatural explanations of nature and found them inadequate, scientists no longer consider supernatural explanations as live options for scientific theory.

EMN: Only publicly accessible methods using natural human faculties can justify theories of nature.

Why not … provide an argument for his definition [of MN] or adopt a more supple pragmatic justification for methodological naturalism? After all, it appears as if Boethius has simply displaced, rather than solved, the problem: the heart of his view is that natural philosophy doesn’t conflict with revelation because it is constrained in scope, but this constraint—which allegedly solves his problem—stands as a brute, unjustified assertion. So Boethius has cloaked rather than dispelled the difficulty.

4.4. Jean Buridan (ca. 1295–1358)

There are several ways of understanding the word “natural.” The first [is] when we oppose it to “supernatural” (and the supernatural effect is what we call a miracle)…. And it is clear that meteorological effects are natural effects, as they are produced naturally, and not miraculously…. Consequently, philosophers explain them by the appropriate natural causes. But common folk, ignorant of these causes, believe that these phenomena are produced by a miracle of God, which is usually not true.

Every order that is good and right in the operations and dispositions of natural beings arises primarily, principally, and originally from that best end for the sake of which everything else exists and acts or is acted upon in its first intention, viz., from God himself.

4.5. Nicole Oresme (ca. 1320–1382)

To show the causes of some effects that seem to be marvels and to show that the effects occur naturally, as do the others at which we ordinarily do not marvel. There is no reason to have recourse to the heavens, the last refuge of the wretched, or to demons, or to our glorious God as if he would produce these effects directly, more so than those effects whose causes we believe are well known to us.

Recent philosophical discussions that stress the historical failure of “supernatural explanations” when compared with “naturalistic explanations” [of nature] fail to take cognisance of the way in which this distinction functioned in the past. No significant medieval natural philosopher ever argued that supernatural explanations might offer an account of how nature usually operates. Indeed one reason for making the distinction was to make possible the identification of miraculous events, which become visible only against the background of the regularities of nature which were themselves attributable to divine providence.

5. Geology: The First Science to Detect Nature’s History with and without MN

far from obstructing the discovery of the Earth’s deep history, positively facilitated it. To borrow a metaphor from biology, they pre-adapted their readers to find it easy and congenial to think in similarly historical terms about the natural world that formed the context of human action and, so believers claimed, of divine initiative.

grossly neglected by historians. The reason for this is no mystery. De Luc’s system has been ridiculed and dismissed because he admitted, indeed emphasized, that his geotheory was an integral part of a Christian cosmology that he set against the deism or atheism of other Enlightenment philosophes. But he was not an intellectual lightweight, nor was he a biblical literalist; he deserves to be treated as seriously by modern historians—even if they do not share his religious beliefs—as he was by his contemporaries.

6. Biological Origin Sciences with and without MN: The Big Difference This Makes

6.1. William Whewell (1794–1866)

The regular form of a crystal, whatever beautiful symmetry it may exhibit, whatever general laws it may exemplify, does not prove design in the same manner in which design is proved by the provisions for the preservation and growth of the seeds of plants, and of the young of animals.

It may be found, that such occurrences as these are quite inexplicable by the aid of any natural causes with which we are acquainted; and thus, the result of our investigations, conducted with strict regard to scientific principles, may be, that we must either contemplate supernatural influences as part of the past series of events, or declare ourselves altogether unable to form this series into a connected chain.

How are we led to elevate, in our conceptions, some of the objects which we perceive into persons? No doubt their actions, their words induce us to do this.… We feel that such actions, such events must be connected by consciousness and personality; that the actions are not the actions of things, but of persons; not necessary and without significance, like the falling of a stone, but voluntary and with purpose like what we do ourselves…

There may thus arise changes of appearance or structure, and some of these changes are transmissible to the offspring: but the mutations thus superinduced are governed by constant laws, and confined within certain limits. Indefinite divergence from the original type is not possible; and the extreme limit of possible variation may usually be reached in a brief period of time.

The inimitable contrivances for adjusting the focus to different distances, for admitting different amounts of light, for the correction of spherical and chromatic aberration, are all on the imaginary road from a bit of nerve to a complex eye; and therefore Nature has travelled on this road to the complex eye. This, it is confessed, seems absurd, but yet this is the doctrine insinuated. But the difficulties are not yet half stated. For, besides all this, and running parallel with these gradations of the optical adjustments, we have a no less complex system of muscles for directing the eye: some of them, as the pulley-muscle, dwelt on by Paley, such as resist the tendencies of their neighbours; and the numerical expression of these correspondencies of the gradations of the optical and the muscular adjustment of the eye is to be multiplied into itself for every organ of the animal, in order to give the number of chances of failure to success in this mode of animal-making.(Ibid)

6.2. Charles Darwin (1809–1882)

On the ordinary view of the independent creation of each being, we can only say that so it is—that it has pleased the Creator to construct all the animals and plants in each great class on a uniformly regulated plan; but this is not a scientific explanation.

6.3. Darwin’s Bulldogs: The X Club from 1864 to 1882, and the Rise of MN to Majority Status

The key to this naturalization strategy was for Huxley to tell a new story about the history of science. By naturalizing theistic science, he was able to argue that science had always been naturalistic. That is, by naturalizing the tradition of theistic science, he was able to remove it from history completely, making naturalism the obvious and solitary way to do science.

historical actors saw the debate as taking place between two sets of scientific authorities. In other words, Christian intellectuals were not willing to give up “science”—they refused to recognize Huxley and his allies as the sole scientific authorities who alone could speak on behalf of “science” and who alone defined its boundaries and determined its larger implications.

7. Christianity Generated Other Rational Beliefs That Contributed to Natural Science

Philosophy [natural science] is written in this all-encompassing book that is constantly open before our eyes, that is the universe; but it cannot be understood unless one first learns to understand the language and knows the characters in which it is written. It is written in mathematical language.

8. Methodological Naturalism: Then and Now

IMN: Science, as a way of knowing nature, excludes supernatural explanations of nature.

PMN: Because scientists, qua scientists, have evaluated supernatural explanations of nature and found them inadequate, scientists no longer consider supernatural explanations as live options for scientific theory.

The fact that turtles are easy to catch hardly provides warrant for thinking that cheetahs will be easy to catch, and the fact that natural explanations in nomological science have enjoyed great success, scarcely warrants the assumption that explanations in terms of natural causes in historical science will enjoy the same degree of success.

9. Conclusions

The issue is not whether it is legitimate to look for natural causes of phenomena, but rather whether science must or should in all circumstances confine itself to attempted explanations in terms of natural causes, no matter how inadequate such attempted explanations prove.

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Dedication

| 1 | For purposes of this essay, I identify science without reference to any theological premises that may have been used within explanations of nature. Such theological premises, depending on their characteristics, might conflict with Christianity, or certain branches of Christianity. For example, Cornelius Hunter has argued that a theological form of naturalism, which he calls theological naturalism, operates internally within some scientific arguments, particularly in origin science. He defines theological naturalism as a set of theological traditions mandating naturalistic explanations in science. For example, he identifies a utilitarian theological premise: God would create to ensure optimal utility in each kind of organism without tradeoffs due to other design criteria such as aesthetics (including whimsical beauty) or ecological integration for higher level order (the ecological tradeoff example is mine, not Hunter’s). This utilitarian theological premise is found in a leading evolutionary biology argument influentially expressed by Stephen Jay Gould: “Odd arrangements and funny solutions are the proof of evolution—paths that a sensible God would never tread but that a natural process, constrained by history, follows perforce,” (Gould 1980, p. 20), as cited in (Hunter 2022, p. 7). See also the following works: (Hunter 2002, 2007, 2021). |

| 2 | (Harrison and Roberts 2018). This anthology updates and expands Numbers’ seminal “Science without God” essay (2003), arguing that Christian intellectuals contributed to science and methodological naturalism (or its rough archaic science-without-God equivalent), but that this largely occurred within a Christian theological framework. So, the essayists generally aim to show that this admirable medieval and early modern achievement was not “without God” in a broad sense. |

| 3 | Such a lesson justified by a similar historiography is in (Bishop 2013). Bishop argues that in nature studies, methodological naturalism has been, for good reasons, the typical orientation of Christians since the Middle Ages. |

| 4 | For a longer lesson in allegedly good science in the same issue of the Christian journal that published Bishop, “God and Methodological Naturalism,” see (Applegate 2003). Applegate offers practical and theological reasons for methodological naturalism. |

| 5 | (Boudry et al. 2010). On 18 February 2017, Boudry tweeted his atheism colorfully: “No self-respecting university should have a Faculty of Theology. Even a Faculty of Astrology would make more sense. At least stars exist.” Accessed on 13 March 2023 at https://twitter.com/mboudry/status/835817310141235200. Boudry underappreciates the university as a medieval invention within Christendom in which about a third of the undergraduate curriculum was devoted to the study of nature (and mathematics) as a means to cultivate reasoning more broadly. The Church funded this towering cultural achievement, as documented in (Grant 2001). |

| 6 | At least in the recent American context, creationism is largely understood to be an endeavor to correlate particular understandings of the first chapters of Genesis in the Bible to the findings of modern science. As Stephen Meyer explains, “Creationism or Creation Science, as defined by the U.S. Supreme Court, defends a particular reading of the book of Genesis in the Bible, typically one that asserts that the God of the Bible created the earth in six literal twenty-four hour periods a few thousand years ago.” By contrast, “The theory of intelligent design does not offer an interpretation of the book of Genesis, nor does it posit a theory about the length of the Biblical days of creation or even the age of the earth. Instead, it posits a causal explanation for the observed complexity of life.” (Meyer 2006). |

| 7 | One reviewer suggested that Neo-Darwinian random mutations are just as impersonally capriciousness as Epicurean randomly swerving atoms, and so it is inconsistent to argue that Epicureans (but not also Darwinians) do not fit the MN origin (and progress) of science narrative, which traditionally aimed at celebrating the elimination (or reduction) of unpredictability in nature. However, in evolutionary theory since Darwin, the capriciousness of random variation is counterbalanced by non-random mechanisms such as natural selection and other natural laws. So Lehoux’s argument still has merit even after qualifying it in response to this reviewer’s insightful comment. One might also note two opposing inclinations within evolutionary theory today: (1) emphasize frequent convergence on similar molecular-anatomical structures due to non-random natural law constraints, or (2) emphasize the overall contingency and unpredictability of evolution as famously expressed by Stephen Jay Gould in his book Wonderful Life (Gould 1989, p. 45) in which he said evolution is “a staggeringly improbable series of events, sensible enough in retrospect and subject to rigorous explanation, but utterly unpredictable and quite unrepeatable. Wind back the tape of life to the early days of the Burgess Shale; let it play again from an identical starting point, and the chance becomes vanishingly small that anything like human intelligence would grace the replay.” A similar tension between random and non-random accounts of nature is seen among ancient Greek thinkers. |

| 8 | (Adelard of Bath 1998, p. 93). This text of Questions on Natural Science (Quaestiones naturales) is based on more manuscripts than previous editions. The other dialogues addressed to his “nephew” are a treatise on the liberal arts that constitute philosophy (On the Same and the Different) and a manual on the upbringing and medication of hawks (On Birds). |

| 9 | (Ibid., pp. 97–98); the translator supplied the interpolations in brackets. |

| 10 | (Abelard and Zemler-Cizewski 2011, p. 55). Zemler-Cizewski supplied all the interpolations in brackets, except for my two interpolations: miraculously and non-miraculously. |

| 11 | (Boethius of Dacia 1987). Boethius interacts with Aristotle’s idea of an eternal uncreated cosmos. |

| 12 | (Dilley 2007, p. 41), concludes regarding Boethius: “The proscription of references to supernatural causes or principles from natural philosophy just is methodological naturalism.” Dilley largely identifies MN as IMN, though he appears to see the utility of engaging EMN. |

| 13 | For a similar argument see (Shank 2019). |

| 14 | (Turner 2010). Turner on p. 104 concludes that, by the late 19th century, many religious writers thought it necessary to promote “a new theology compatible with the new science” of biological origins driven by MN. This development “fostered conflict, as more traditionally minded religionists attempted to defend older opinions that stood in contradiction” to MN-guided biological origins science. (Moore 1979), gives a prominent example of a theological novelty that traditional theologians contested: The Catholic scholar Saint George Jackson Mivart (1827–1900), one of the most influential theological commentators on evolutionary theory, believed that the “human body was derived from” a natural God-guided evolutionary process, “but the soul, the source of mankind’s rational and ethical nature, appeared de novo by creative fiat.” Moore further notes that five years after Mivart published this conclusion, Pope Pius IX conferred on Mivart the degree of doctor of philosophy (1876). |

| 15 | Grant, The Nature of Natural Philosophy, pp. 49–90, argues that some of the Aristotelian philosophical principles condemned by the bishop of Paris in 1270 and 1277 stimulated non-Aristotelian conceptions of nature that produced scientific progress in the medieval and early modern periods. Boethius’ career at the University of Paris was in its final stages around the time of these condemnations. In this controversial milieu, he framed his MN-like rule to protect his professional space as a natural philosopher, while also affirming his theological orthodoxy. |

| 16 | Newton’s title in its original Latin was Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica. For the helpful role of Christian theology in this development, see (Kaiser 1997). |

| 17 | Natural philosophers were tasked with studying natural, not supernatural, events. In view of this university requirement, Buridan wrote: “In natural philosophy, we ought to accept actions and dependencies as if they always proceed in a natural way.” However, Buridan in practice did not strictly follow this advice. Buridan, Questions on the Heavens (de caelo), book 2, question 9, as cited in (Grant 2012, p. 42). |

| 18 | This point is extensively documented in (Heilbron 1999). |

| 19 | Prominent among such misguided literature is Boudry et al. (2010, 2012) discussed in Section 2. For a response to these essays, see (Harrison 2018). |

| 20 | For an assessment of the presence of MN during the scientific revolution, see (Harrison 2019). On p. 70 he writes: “One of the shortcomings of early modern natural philosophy was its limited capacity to shed light on the origins of the earth, the geological changes that it had undergone in the past, and those that would befall it in the future. Newton, for example, insisted that the scope of natural philosophy extended only to ‘the present frame of nature’ and not the creation of the world, nor its eventual destruction.” |

| 21 | (Davis 2023). Referring on p. 6 to natural philosophy not focused on origins, Davis writes that “Boyle rejected miracles in natural philosophy: there he accepted methodological naturalism.” However, Davis also notes on p. 14 that Boyle’s work has legitimately provided the basis for what is now called the theory of intelligent design (ID) with regard to biological origins. Such ID proponents, Davis observes, share Boyle’s “view that mechanistic science gives rise to powerful arguments for an intelligent designer” when “they use current scientific knowledge of what mechanistic processes can do to identify aspects of nature that (in their view) cannot be explained by unintelligent causes alone….” This entails the repudiation of MN in the study of biological origins, which was implicit in Boyle’s work and explicit in ID today. |

| 22 | Earlier natural philosophers addressed some origins questions (e.g., the cause of the cosmos, earth, and life), but with only rudimentary investigative techniques. |

| 23 | (Rudwick 2005, p. 171), “No naturalist could now [about 1825] claim, with any credibility, that life had maintained an ahistorical stability or steady state, still less a recurring cyclicity, of the kind that Hutton, long before, had conjectured for its physical environment.” Rudwick’s book is a comprehensive study of the origin of geology, not just a treatise on geology and religion. |

| 24 | A possible objection to this conclusion would be to identify the Christian contribution to geohistory as science-engaged philosophy rather than an argument within science and to argue that only the latter is legitimately restricted by any form of MN. However, this objection misses the mark. In this case, the scientists structured their arguments within science by means of emulating a Christian view of directional history. |

| 25 | Whewell used the term consilience to roughly refer to what is now more commonly called unification. (McMullin 2014). For an elaboration of unification in contrast with other theoretical virtues, see Keas, “Systematizing the Theoretical Virtues.” |

| 26 | (Ducheyne 2010). Ducheyne notes that Whewell was a respected practicing scientist (especially in tide theory) in addition to his main expertise in the history and philosophy of science. |

| 27 | (Crowe 2016). Here on pp. 437–45, and in a forthcoming essay, Crowe shows how Whewell pioneered astrobiology’s circumstellar habitable zone (Whewell called it the “Temperate Zone of the Solar System”). Whewell established this life-friendly zone on the physics of the rapid diminution of heat at further distances from a host star—the inverse square law for stellar radiation discovered by Whewell’s close friend, the leading astronomer John Herschel. In our solar system, the inner planets are too hot for complex life, and the outer planets are too cold. Whewell recognized this is based on natural laws governing all solar systems, making potentially habitable planets (based on temperature for liquid water) rare compared to what had been imagined previously. |

| 28 | (Davis 2013). Davis notes that Boyle contributed to “‘Boyle’s Law,’ the inverse relation between the pressure and volume of gases that is a standard part of a basic chemistry course.” |

| 29 | For an assessment of Harvey that is similar to Whewell’s, see (McMullen 1998). |

| 30 | (Whewell 1858, p. 246). Whewell quotes Bichat’s Anatomie Générale. |

| 31 | (Whewell 1857, p. 488, this is identical in the 1st ed. of 1837, p. 588). |

| 32 | Ibid. Here is the context for the quotation. Whewell writes of “the impossibility of accounting by any natural means for the production of all the successive tribes of plants and animals which have peopled the world in the various stages of its progress, as geology teaches us. That they were, like our own animal and vegetable contemporaries, profoundly adapted to the condition in which they were placed, we have ample reason to believe; but when we inquire whence they came into this our world, geology is silent. The mystery of creation is not within the range of her [geology’s] legitimate territory; she [geology] says nothing, but she points upwards.” (emphasis is mine). |

| 33 | (Ruse 2010). See https://todayinsci.com/W/Whewell_William/WhewellWilliam-Quotations.htm (accessed on 11 March 2023) or an example of the error of nature, rather than geology, in brackets. |

| 34 | Similar to the historian of geology Rudwick, Whewell declares that “the geologist is an antiquary [historian] of a new order,” due to “a real and philosophical connexion of the principles of investigation” of human history and geology. “The organic fossils which occur in the rock, and the medals which we find in the ruins of ancient cities, are to be studied in a similar spirit and for a similar purpose…. The history of the earth, and the history of the earth’s inhabitants, as collected from phenomena, are governed by the same principles…. In both we endeavor to learn accurately what the present is, and hence what the past has been. Both are historical sciences in the same sense.” (Whewell 1857, pp. 398–402). |

| 35 | |

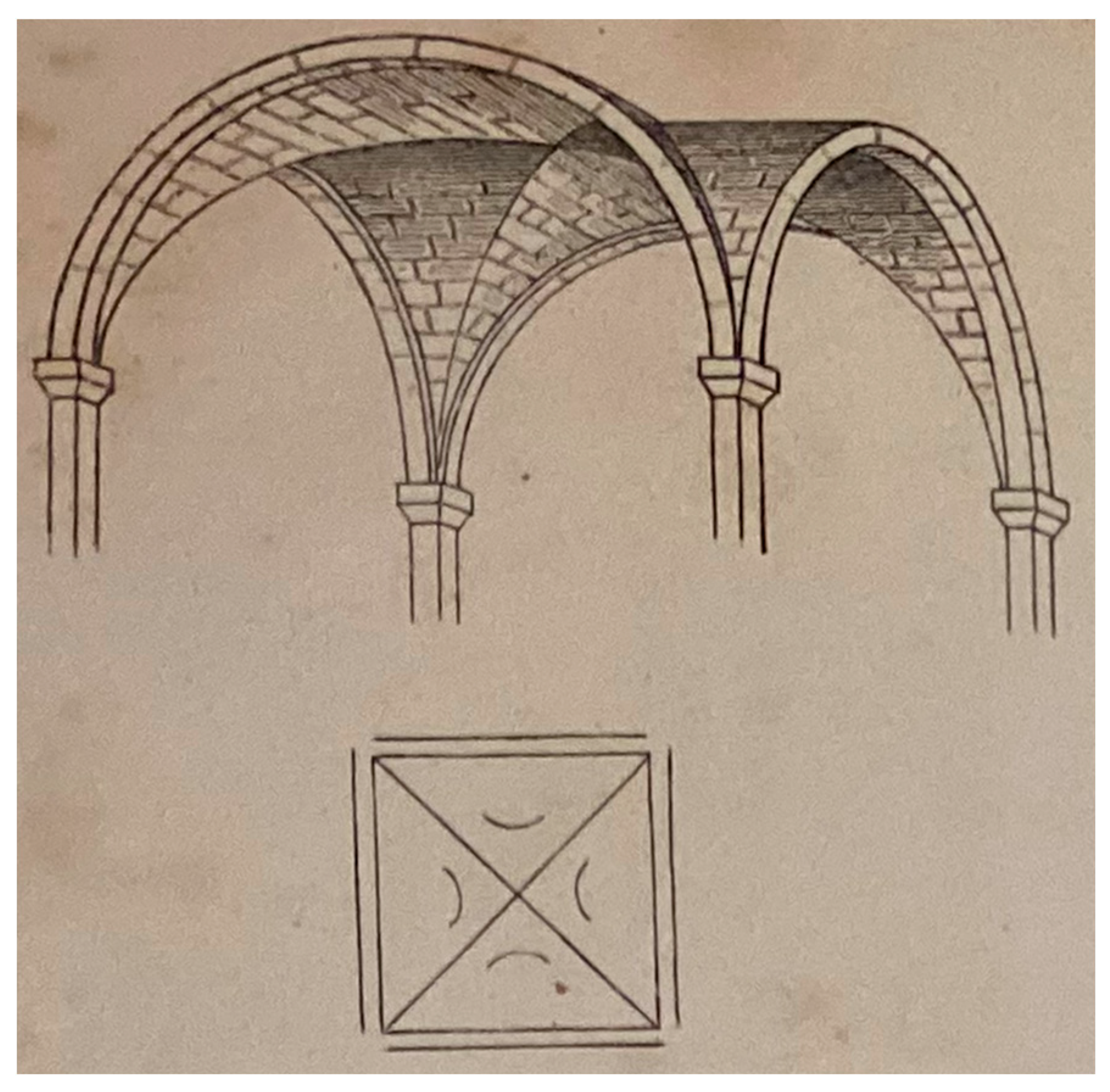

| 36 | Ibid., plate I, Figure 3. |

| 37 | Whewell considered the aesthetic criterion of highly coordinated vertical lines (as opposed to Romanesque horizontal orientation with a lower degree of coordination) to be the main “formative principle” of Gothic architecture, “which gave unity and consistency to the new style, and disclosed a common tendency in the changes which had been going on in the different members [i.e., physical components] of the architecture. And the very fact of this character being, when once applied, so manifest and simple a mode of combining the parts of the structure into a harmonious whole, shows how much of genius there was in the discovery” (Ibid., pp. 10–11). He hinted at an underlying aesthetic theory to this aesthetic judgment: “Now in order to consider a work of art as beautiful, we must see, or seem to see, the relations of its parts with clearness and definiteness. Conceptions which are loose, incomplete, scanty, partial, can never leave us pleased and gratified, if we are capable of full and steady comprehensions” (Ibid., p. 9). Given that Whewell deployed much of his architectural history logic to the history of life on earth, he would have surely appreciated the subsequent discovery of both the aesthetic and physical survival value of compact seed arrangements in certain flowers which exhibit Fibonacci (or similar mathematical regularities) in their spiral arrangements of seeds. (A Fibonacci sequence is one in which each number is the sum of the two preceding ones: e.g., 1, 2, 3, 5, 8…). There are multiple beautiful Fibonacci or Fibonacci-like arrangements that embody mathematically elegant solutions to seed arrangements that cannot be fully reduced to mere Darwinian physical survival value. The scientific theories that recognize this in flowers exhibit beauty as a trait of a good theory (theoretical virtue), which has recently been defined: A theory that “evokes aesthetic pleasure in properly functioning and sufficiently informed persons.” Keas, “Systematizing the Theoretical Virtues,” 2762. Beautiful mathematical relations in our theories of natural laws (e.g., gravity) and biological structures (e.g., Fibonacci seed arrangements) have often been taken to have epistemic value in scientific reasoning itself (Ibid., pp. 2772–75). |

| 38 | (Whewell 1845, p. 62). Whewell considers here detecting events “out of the common course of nature; acts which, therefore, we may properly call miraculous.” |

| 39 | (Whewell 1866, pp. 357–58). He roughly quotes Darwin’s Origin, 1st ed., pp. 186–87, omitting the words in brackets, and paraphrasing a few tiny portions—all without altering Darwin’s essential meaning: “Several facts make me suspect that any sensitive nerve may be rendered sensitive to light”; “[Reason tells me, that if] numerous gradations from a perfect and complex eye to one very imperfect and simple, each grade [being] useful to its possessor, can be shown to exist; [if] further, the eye does vary, if only slightly, and its variations are unlimited; and if any variation or modification in the organ be ever useful to an animal under changing conditions of life, then the difficulty of believing that a perfect and complex eye could be formed by natural selection [, though insuperable by our imagination,] can hardly be considered real.” |

| 40 | Darwin, “Books to be Read” list, as cited in (Ruse 1975); Quinn, “Whewell’s Philosophy of Architecture,” 17, notes the “absence of any discussion” of Whewell’s Philosophy “from Darwin’s correspondence and notebooks.” He concludes that this “is strong evidence that Darwin did not read the book.” |

| 41 | Darwin thoroughly annotated his copy of Whewell, History of the Inductive Sciences (1837), so he likely read it carefully. This is documented in footnote 29 of Ruse, “Darwin’s Debt to Philosophy.” Whewell’s (1837) History had much less coverage of MN-defying biological design inferences than Whewell’s (1840) Philosophy. |

| 42 | I thank Kerry Magruder for noting some affinities between my account of methodological pluralism and Charles Taylor’s treatment of secularism as pluralism rather than naturalism or materialism (Taylor 2007). Magruder highlighted for me how Taylor successfully argues against the historiography of secularism as a relentless increase in materialism, which amounts to a subtraction account, in which religion is progressively marginalized and subtracted from public visibility. |

| 43 | In an 1856 letter to the prominent theistic evolutionist Asa Gray, Darwin dismissed special creation as unscientific: “For to my mind to say that species were created so and so is no scientific explanation, only a reverent way of saying it is so and so.” (Darwin 1897, p. 437). |

| 44 | (Quinn 2016, p. 17) mentions that “Darwin and Whewell were on good terms and discussed scientific matters. Many of these conversations occurred as the two walked home from J. S. Henslow’s weekly scientific gatherings. Additionally, Whewell and Darwin would have met regularly through the Geological Society from 1837 to 1838.” |

| 45 | (Darwin 1859, p. 435, 1860, p. 434, 1861, pp. 466–67). These first three editions render the passage: “On the ordinary view of the independent creation of each being, we can only say that so it is;—that it has so pleased the Creator to construct each animal and plant.” |

| 46 | (Dilley 2013, p. 24). See Dilley’s footnotes for examples of such scholarly judgments. |

| 47 | (Lightman and Dawson 2014, p. 1). Dawson and Lightman establish that “in the prologue to his Essays upon Some Controverted Questions (1892), Thomas Henry Huxley offered a retrospective defense of what he called the ‘principle of the scientific Naturalism of the latter half of the nineteenth century.’” They note that Huxley’s term, which he refashioned from earlier usage, was “certainly preferable to the considerably more contentious term scientific materialism coined by his close friend [and prominent X Club member] John Tyndall twenty years earlier.” |

| 48 | Dawson and Lightman, Victorian Scientific Naturalism; (Harrison and Roberts 2018; Lightman and Reidy 2016; Brooke 2018). |

| 49 | (Barton 2018, p. 282). Barton notes that the honorific Abbey burial of Darwin was pulled off principally by X Club connections to the Royal Society and the official science representative to parliament. |

| 50 | This was announced by the Dean of Westminster at https://www.westminster-abbey.org/abbey-news/professor-stephen-hawking-to-be-honoured-at-the-abbey, accessed on 30 January 2023. |

| 51 | Another related factor was the rise of liberal Christianity, which minimized the supernatural within Christianity. See (Ungureanu 2019). |

| 52 | St. Augustine, Contra Faustum Manichaeum 32.20, as cited in (Harrison 2006). |

| 53 | (Smith 2014), inside jacket synopsis. |

| 54 | Johannes Kepler Gesammelte Werke, 13:309, letter no. 117, lines 174–9, as cited in (Kaiser 2007a, p. 175). See also (Keas 2019, chp. 10). |

| 55 | Kepler’s textbook dedication, as translated in (Kepler and Baumgardt 1951). |

| 56 | Kepler’s conception of receiving divine revelation while doing science is articulated in passages such as these: “For He Himself has let man take part in the knowledge of these things and thus not in a small measure has set up His image in man. Since He recognized as very good this image which He made, He will so much more readily recognize our efforts with the light of this image also to push into the light of knowledge the utilization of the numbers, weights and sizes which He marked out at creation. For these secrets are not of the kind whose research should be forbidden; rather they are set before our eyes like a mirror so that by examining them we observe to some extent the goodness and wisdom of the Creator.” Johannes Kepler, Epitome of Copernican Astronomy, as cited in (Caspar 1993, p. 381). Kepler recognized “a divine ravishment [being cognitively carried away by God] in investigating the works of God.” (Kepler 1952, pp. 849–50). |

| 57 | For some of the other factors (especially liberal Christianity that diminished the role of supernatural causation), see (Ungureanu 2019). |

References

- Abelard, Peter, and Wanda Zemler-Cizewski. 2011. Corpus Christianorum Continuatio Mediaevalis. In An Exposition on the Six-Day Work. Turnhout: Brepols, vol. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Adelard of Bath. 1998. Conversations with His Nephew: On the Same and the Different, Questions on Natural Science, and on Birds. Edited by Charles Burnett. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Applegate, Kathryn. 2003. A Defense of Methodological Naturalism. Perspectives on Science & Christian Faith 65: 37–45. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, Ruth. 2018. The X Club: Power and Authority in Victorian Science. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Biard, Joel. 2001. The Natural Order in John Buridan. In The Metaphysics and Natural Philosophy of John Buridan. Edited by J. M. M. H. Thijssen and Jack Zupko. Leiden: Brill, pp. 77–95. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, Robert. 2013. God and Methodological Naturalism in the Scientific Revolution and Beyond. Perspectives on Science and Christian Faith 65: 10–23. [Google Scholar]

- Boethius of Dacia. 1987. On the Supreme Good, on the Eternity of the World, on Dreams. Translated by John F. Wippel. Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Boucher, Sandy. 2020. Methodological Naturalism in the Sciences. International Journal for Philosophy of Religion 88: 57–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudry, Maarten, Stefaan Blancke, and Johan Braeckman. 2010. How Not to Attack Intelligent Design Creationism: Philosophical Misconceptions About Methodological Naturalism. Foundations of Science 15: 227–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudry, Maarten, Stefaan Blancke, and Johan Braeckman. 2012. Grist to the Mill of Anti-Evolutionism: The Failed Strategy of Ruling the Supernatural Out of Science by Philosophical Fiat. Science & Education 21: 1151–65. [Google Scholar]

- Brooke, John Hedley. 2010a. ‘Laws Impressed on Matter by the Creator’? The Origin and the Question of Religion. In The Cambridge Companion to the “Origin of Species. Edited by Michael Ruse and Robert Richards. New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 256–74. [Google Scholar]

- Brooke, John Hedley. 2010b. Darwin and Religion: Correcting the Caricatures. Science & Education 19: 391–405. [Google Scholar]

- Brooke, John Hedley. 2018. The Ambivalence of Scientific Naturalism: A Response to Mark Harris. Zygon 53: 1051–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buridan, John. 1509. Quaestiones Super Octo Physicorum Libros Aristotelis. Paris: Impensis D. Roce, ll. 13, fol. 39rb. [Google Scholar]

- Caspar, Max. 1993. Kepler. Translated by C. Doris Hellman. New York: Dover. [Google Scholar]

- Crowe, Michael J. 2016. William Whewell, the Plurality of Worlds, and the Modern Solar System. Zygon 51: 431–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dales, Richard C. 1992. The Intellectual Life of Western Europe in the Middle Ages, 2nd ed. Leiden: E.J. Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Darwin, Charles. 1859. On the Origin of Species, 1st ed. London: John Murray. [Google Scholar]

- Darwin, Charles. 1860. On the Origin of Species, 2nd ed. London: John Murray. [Google Scholar]

- Darwin, Charles. 1861. On the Origin of Species, 3rd ed. London: John Murray. [Google Scholar]

- Darwin, Charles. 1866. On the Origin of Species, 4th ed. London: John Murray. [Google Scholar]

- Darwin, Charles. 1897. The Life and Letters of Charles Darwin. Edited by Francis Darwin. New York: Appleton. [Google Scholar]

- Darwin, Charles. 1959. The Autobiography of Charles Darwin 1809–1882. Edited by Nora Barlow. London: Collins. Available online: http://darwin-online.org.uk/content/frameset?itemID=F1497&pageseq=1&viewtype=text (accessed on 11 March 2023).

- Daston, Lorraine, and Katharine Park. 1998. Wonders and the Order of Nature, 1150–1750. New York: Zone Books. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Edward B. 1999. Christianity and Early Modern Science: The Foster Thesis Reconsidered. In Evangelicals and Science in Historical Perspective. Edited by David N. Livingstone, D. G. Hart and Mark A. Noll. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Edward B. 2013. The Faith of a Great Scientist: Robert Boyle’s Religious Life, Attitudes, and Vocation. Available online: https://biologos.org/articles/the-faith-of-a-great-scientist-robert-boyles-religious-life-attitudes-and-vocation (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- Davis, Edward B. 2023. Robert Boyle, The Bible, and Natural Philosophy. Religions 14: 795. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2077-1444/14/6/795 (accessed on 13 March 2023).

- Dembski, William A., Wayne J. Downs, and Fr Justin B. A. Frederick. 2008. The Patristic Understanding of Creation: An Anthology of Writings from the Church Fathers on Creation and Design. Riesel: Erasmus Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dilley, Stephen Craig. 2007. Methodological Naturalism, History, and Science. Ph.D. dissertation, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Dilley, Stephen. 2013. The Evolution of Methodological Naturalism in the Origin of Species. The Journal of the International Society for the History of Philosophy of Science 3: 20–58. [Google Scholar]

- Dockrill, David William. 1971. T. H. Huxley and the Meaning of ‘Agnosticism’. Theology 74: 461–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducheyne, Steffen. 2010. Fundamental Questions and Some New Answers on Philosophical, Contextual and Scientific Whewell: Some Reflections on Recent Whewell Scholarship and the Progress Made Therein. Perspectives on Science 18: 242–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastwood, Bruce S. 2013. Early-Medieval Cosmology, Astronomy, and Mathematics. In Cambridge History of Science: Volume 2, Medieval Science. Edited by David C. Lindberg and Michael H. Shank. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ebbesen, Sten. 2020. “Boethius of Dacia,” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Available online: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/boethius-dacia/ (accessed on 14 March 2023).

- Elsdon-Baker, Fern, and Bernard V. Lightman, eds. 2020. Identity in a Secular Age: Science, Religion, and Public Perceptions. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. [Google Scholar]

- Expelled: No Intelligence Allowed. 2008. Documentary film directed by Nathan Frankowski. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V5EPymcWp-g (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- Finocchiaro, Maurice A. 2008. The Essential Galileo. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Gould, Stephen Jay. 1980. The Panda’s Thumb. In The Panda’s Thumb. New York: W. W. Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Gould, Stephen Jay. 1989. Wonderful Life: The Burgess Shale and Nature of History. New York: W. W. Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, Edward. 1993. Jean Buridan and Nicole Oresme on Natural Knowledge. Vivarium 31: 84–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, Edward. 2001. God and Reason in the Middle Ages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, Edward. 2012. The Nature of Natural Philosophy in the Late Middle Ages (Studies in Philosophy and the History of Philosophy). Washington DC: Catholic University of America Press, vol. 52. [Google Scholar]

- Hannam, James. 2009. God’s Philosophers: How the Medieval World Laid the Foundations of Modern Science. London: Icon Books. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, Bert. 1985. Nicole Oresme and the Marvels of Nature: De Causis Mirabilium. Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Medieval Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, Peter, and Jon H. Roberts. 2018. Science without God?: Rethinking the History of Scientific Naturalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, Peter. 2006. The Bible and the Emergence of Modern Science. Science and Christian Belief 18: 118. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, Peter. 2007. The Fall of Man and the Foundations of Science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, Peter. 2018. Naturalism and the Success of Science. Religious Studies 56: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, Peter. 2019. Laws of God or Laws of Nature? Natural Order in the Early Modern Period. In Science without God?: Rethinking the History of Scientific Naturalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 58–76. [Google Scholar]

- Hawking, Stephen. 1998. A Brief History of Time, 10th anniversary ed. New York: Bantam Books. [Google Scholar]

- Heilbron, John L. 1999. The Sun in the Church: Cathedrals as Solar Observatories. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, Cornelius. 2007. Science’s Blind Spot: The Unseen Religion of Scientific Naturalism. Grand Rapids: Brazos Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, Cornelius G. 2002. Darwin’s God: Evolution and the Problem of Evil. Grand Rapids: Brazos Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, Cornelius G. 2021. Evolution as a Theological Research Program. Religions 12: 694. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2077-1444/12/9/694 (accessed on 6 June 2023).

- Hunter, Cornelius G. 2022. The Theological Structure of Evolutionary Theory. Religions 13: 774. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2077-1444/13/9/774 (accessed on 7 June 2023).

- Kaiser, Christopher B. 1997. Creational Theology and the History of Physical Science: The Creationist Tradition from Basil to Bohr. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, Christopher B. 2007a. Science-Fostering Belief—Then and Now. Perspectives on Science and Christian Faith 59: 171–81. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, Christopher B. 2007b. Toward a Theology of Scientific Endeavour: The Descent of Science. Ashgate Science and Religion Series. Aldershot: Ashgate, vol. 48. [Google Scholar]

- Keas, Michael N. 2018. Systematizing the Theoretical Virtues. Synthese 195: 2761–93. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11229-017-1355-6 (accessed on 5 June 2022).

- Keas, Michael N. 2021. Evaluating Warfare Myths About Science and Christianity and How These Myths Promote Scientism. Religions 12: 1–13. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2077-1444/12/2/132 (accessed on 11 June 2023).

- Keas, Michael Newton. 2019. Unbelievable: 7 Myths About the History and Future of Science and Religion. Wilmington: ISI Books. [Google Scholar]

- Kepler, Johannes, and Carola Baumgardt. 1951. Johannes Kepler: Life and Letters. New York: Philosophical Library, pp. 122–23. [Google Scholar]

- Kepler, Johannes. 1952. Epitome of Copernican Astronomy. In Great Books of the Western World. Translated by Charles Glenn Wallis. Chicago: Encyclopedia Britannica, vol. 16. [Google Scholar]

- Larmer, Robert. 2019. The Many Inadequate Justifications of Methodological Naturalism. Organon F 26: 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehoux, Daryn. 2019. ‘All Things Are Full of Gods’: Naturalism in the Classical World. In Science without God?: Rethinking the History of Scientific Naturalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lightman, Bernard. 2002. Huxley and Scientific Agnosticism: The Strange History of a Failed Rhetorical Strategy. The British Journal for the History of Science 35: 271–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lightman, Bernard. 2016. Science at the Metaphysical Society: Defining Knowledge in the 1870s. In The Age of Scientific Naturalism. Edited by Bernard Lightman and Michael S. Reidy. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, vol. 10, pp. 187–206. [Google Scholar]

- Lightman, Bernard, and Gowan Dawson, eds. 2014. Victorian Scientific Naturalism: Community, Identity, Continuity. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lightman, Bernard, and Michael S. Reidy, eds. 2016. The Age of Scientific Naturalism: Tyndall and His Contemporaries. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg, David C., and Katherine H. Tachau. 2013. The Science of Light and Color, Seeing and Knowing. In Cambridge History of Science: Volume 2, Medieval Science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Luskin, Casey. 2021. What Is Intelligent Design? Available online: https://intelligentdesign.org/articles/what-is-intelligent-design/ (accessed on 30 March 2023).

- McMullen, Emerson Thomas. 1998. William Harvey and the Use of Purpose in the Scientific Revolution: Cosmos by Chance or Universe by Design? Lanham: University Press of America. [Google Scholar]

- McMullin, Ernan. 2014. The Virtues of a Good Theory. In The Routledge Companion to Philosophy of Science. Edited by Martin Curd and Stathis Psillos. New York: Routledge, pp. 561–71. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, Stephen C. 2006. A Scientific History and Philosophical Defense of the Theory of Intelligent Design. Religion-Staat-Gesellschaft 7: 203–47. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, James R. 1979. The Post-Darwinian Controversies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Numbers, Ronald L. 2003. Science without God: Natural Laws and Christian Beliefs. In When Science and Christianity Meet. Edited by David C. Lindberg and Ronald L. Numbers. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 265–86. [Google Scholar]

- Plantinga, Alvin. 2011. Where the Conflict Really Lies: Science, Religion, and Naturalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn, Aleta. 2016. William Whewell’s Philosophy of Architecture and the Historicization of Biology. Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences 59: 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudwick, Martin J. S. 2005. Bursting the Limits of Time: The Reconstruction of Geohistory in the Age of Revolution. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rudwick, Martin J. S. 2021. Earth’s Deep History: How It Was Discovered and Why It Matters. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ruse, Michael. 1975. Darwin’s Debt to Philosophy: An Examination of the Influence of the Philosophical Ideas of John F. W. Herschel and William Whewell on the Development of Charles Darwin’s Theory of Evolution. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part A 6: 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruse, Michael. 2010. Intelligent Design Is an Oxymoron. The Guardian, May 5. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/belief/2010/may/05/intelligent-design-fuller-creationism (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- Shank, Michael H. 2019. Naturalist Tendencies in Medieval Science. In Science without God?: Rethinking the History of Scientific Naturalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A. Mark. 2014. From Sight to Light: The Passage from Ancient to Modern Optics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Tiddy. 2017. Methodological Naturalism and Its Misconceptions. International Journal for Philosophy of Religion 82: 321–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, Laura J. 2010. Reforming Philosophy: A Victorian Debate on Science and Society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, Laura J. 2011. The Philosophical Breakfast Club: Four Remarkable Friends Who Transformed Science and Changed the World. New York: Broadway Books. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley, Matthew. 2014a. Huxley’s Church and Maxwell’s Demon: From Theistic Science to Naturalistic Science. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley, Matthew. 2014b. Where Naturalism and Theism Met: The Uniformity of Nature. In Victorian Scientific Naturalism: Community, Identity, Continuity. Edited by Gowan Dawson and Bernard Lightman. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Charles. 2007. A Secular Age. 1999 Gifford Lectures. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, Frank M. 2010. The Late Victorian Conflict of Science and Religion as an Event in Nineteenth-Century Intellectual and Cultural History. In Science and Religion New Historical Perspectives. Edited by Thomas Dixon, Geoffrey Cantor and Stephen Pumfrey. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ungureanu, James C. 2019. Science, Religion and the Protestant Tradition: Retracing the Origins of Conflict. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. [Google Scholar]

- Whewell, William. 1833. Astronomy and General Physics Considered with Reference to Natural Theology, 2nd ed. Christian Apologetics Book in the Bridgewater Treatise Series. London: William Pickering. [Google Scholar]

- Whewell, William. 1840. The Philosophy of the Inductive Sciences. London: J. W. Parker. [Google Scholar]

- Whewell, William. 1842. Architectural Notes on German Churches, 3rd ed. Cambridge: J. and J.J. Deighton. First published 1830. [Google Scholar]

- Whewell, William. 1845. Indications of the Creator: Extracts Bearing upon Theology, from the History and the Philosophy of the Inductive Sciences. London: J. W. Parker. [Google Scholar]

- Whewell, William. 1847. The Philosophy of the Inductive Sciences, Founded Upon Their History, 2nd ed. London: J. W. Parker, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Whewell, William. 1857. History of the Inductive Sciences from the Earliest to the Present Time, 3rd ed. London: John W. Parker, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Whewell, William. 1858. History of Scientific Ideas: Being the First Part of the Philosophy of the Inductive Sciences, 3rd ed. London: John W. Parker, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Whewell, William. 1866. Comte and Positivism. Macmillan’s Magazine 13: 353–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, Richard R. 1986. The Principle of Plenitude and Natural Theology in Nineteenth-Century Britain. The British Journal for the History of Science 19: 263–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, Richard R. 1993. Defining Science: William Whewell, Natural Knowledge, and Public Debate in Early Victorian Britain. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zupko, Jack. 2008. Buridan and Skepticism. Journal of the History of Philosophy 31: 191–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Keas, M.N. Christianity Cultivated Science with and without Methodological Naturalism. Religions 2023, 14, 927. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14070927

Keas MN. Christianity Cultivated Science with and without Methodological Naturalism. Religions. 2023; 14(7):927. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14070927

Chicago/Turabian StyleKeas, Michael N. 2023. "Christianity Cultivated Science with and without Methodological Naturalism" Religions 14, no. 7: 927. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14070927

APA StyleKeas, M. N. (2023). Christianity Cultivated Science with and without Methodological Naturalism. Religions, 14(7), 927. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14070927