3. Ibn ʻArabī’s Transimmanence

In this section, we shall study Ibn ʻArabī’s understanding of wujūd through the conceptual lens of transimmanence. This allows us to delineate the metaphysical components of the waḥdat al-wujūd framework. The concentration of this section is on selected chapters from the Fuṣūṣ al-Ḥikam. As is clear from the introduction, the purpose of this analysis is to demonstrate Akbarian ontological pluralism.

In the Qura’nic story about Noah—told and retold in sūra 11, 23, and 71—he is a messenger of

tawḥīd (or the oneness of God) sent to an idolatrous people. The message he brings, however, is rejected by the people. In sūra 71 (on Noah), the addressees of the message say amongst themselves, “Do not renounce your gods! Do not renounce Wadd, Suwa’, Yaghuth, Ya’uq, or Nasr!” (Q. 71: 24;

Abdel Haleem 2005, p. 391). In sūra 11 (on Hūd), they challenge Noah to bring down the punishment that he threatens (Q. 11: 22). This punishment is brought down in the form of a flood (Q. 11: 44) from which only the believers of Noah’s message are saved by boarding Noah’s ark, while the disbelievers (including Noah’s son) are drowned. This is the simplest outline of the story. Ibn ʻArabī, however, reads this story in a radically pluralistic way. Toshihiko Izutsu says of this reading that Ibn ʻArabī “gives it an extremely original interpretation, so original, indeed, that it will surely shock or even scandalize common sense” (

Izutsu 1983, p. 58). Shahab Ahmed calls it a “profoundly counter-intuitive and destabilizing reading” (

Ahmed 2016, p. 28). Our reading of this chapter aims to establish Ibn ʻArabī’s interpretation as

ontologically pluralistic.

Ibn ʻArabī reads the story of Noah as indicative of the shortcoming in the way the prophet addressed the idolaters. This re-reading has a directly metaphysical foundation. In explicating the methodological approach of the

Fuṣūṣ, Ronald Nettler states that it “combines an earthy narrative literature of scripture and prophetic story with an extremely abstruse ‘Sufi metaphysics’, the latter for him presumably reflecting the inner, essential, truth of the former” (

Nettler 2003, p. 14). He goes on to say, “This

genre may be called a form of ‘Sufi metaphysical story-telling’” (

Nettler 2003, p. 14). In Ibn ʻArabī’s pluralistic reading of the story of Noah, what metaphysical structural components allow him to refashion the story? My argument is that it is transimmanence as a metaphysical lens that allows him his interpretation. Let us first listen to his metaphysical story and then analyse the components of his Sufi metaphysics of transimmanence.

In Ibn ʻArabī’s retelling of the story, he finds Noah’s shortcoming in the fact that he produces a God of transcendence to a people given over to the worship of God in the mode of immanence. In another chapter of the

Fuṣūṣ, this is why Aaron did not stop the Israelites from worshipping the calf. In fact, he reads Aaron’s incapacity to deter “the people from worshipping the calf” as “God’s wisdom which manifests itself in existence so that He should be worshipped in every form” (

Abrahamov 2015, p. 153). Noah and Aaron (and Moses) face a situation where people are worshipping God as immanent in created things. Ibn ʻArabī’s metaphysical principle in understanding this situation is this: “The Real is manifest in every created and comprehended (

mafhūm) thing” (

Abrahamov 2015, p. 36). All the created and comprehended things of the world—all objects of external or internal experience—are manifestations or

tajalliyāt of the divine. The people Noah addresses worship God as He manifests in the created and comprehended things. To deny this aspect, Ibn ʻArabī maintains, is to focus exclusively on God’s transcendence and thus on His unlikeness to (or distance from) every created or comprehended thing. This theology of pure transcendence is a partial theology. As Ibn ʻArabī makes clear, “Whoever believes in God’s transcendence (

munazzih) is either foolish or ill-mannered. If he, as a believer in religion, holds (this doctrine) unreservedly and believes in it and does not take into consideration something else, he misbehaves, denies the truth and the messengers, without being aware of this (consequence)” (

Abrahamov 2015, p. 36). However, this does not mean that worshipping the idols—or worshipping the locus of God’s manifestation in a way that clouds that which manifests in the locus—is correct either. For Ibn ʻArabī says, “Likewise, whoever holds the Real’s immanence (

shabbaha) and does not hold His transcendence (

nazzaha) limits and restricts Him and does not know Him” (

Abrahamov 2015, p. 37). Ibn ʻArabī’s critique of exclusive adherence to pure immanence or pure transcendence is undertaken with a nuance that is important to carefully unpack.

The chapter on Noah, like several chapters in the

Fuṣūṣ, contains a short poem that captures, in essence, the philosophical thrust of the chapter. The poem emphasises the need for combining—and holding in tension—both transcendence and immanence (

Abrahamov 2015, pp. 37–38):

If you hold transcendence, you restrict Him/and if you hold immanence,

you limit Him

If you hold the two doctrines, you are right/and you will be a leader and a master in knowledge

Beware of likening Him if you hold duality/and of making Him transcendent

if you unify Him

You are not He, but you are He and you see Him/in the essence of things

both boundless and restricted.

The move Ibn ʻArabī is making here is much more complicated than simply holding two doctrines or positions in a delicate balance or synthesis. I would argue that he is holding the two in dialectical tension: a notion that has a lot of resonance in modern philosophy as well. Not only are the two terms (

tashbīh and

tanzīh) brought together here, Ibn ʻArabī asks us to ponder on the presence of transcendence

in immanence and immanence

in transcendence. For this, he uses two statements from the Qur’an that are emblematic of the positions of

tanzīh and

tashbīh, respectively: “There is nothing like His likeness” (Q. 42:11:

laysa ka-mithlihi shay’) and “He is the All Hearing, the All Seeing” (Q. 42: 11;

Abdel Haleem 2005, p. 312). Ibn ʻArabī’s use of this verse is not just limited to the chapter on Noah but also appears in other places; we shall briefly look at his chapter on Elias, which explains the logic of his dialectic better.

In the chapter on Elias, he says, “Each is connected with the other, so that transcendence cannot be free of immanence, and vice versa” (

Abrahamov 2015, p. 142). He notes how even in the greatest Qura’nic statement of transcendence, “There is nothing like His likeness”, there is already hidden a gesture of immanence. He says, “This is the greatest verse of transcendence ever sent down, even though it is not free of immanence because of the letter kaf (like)” (

Abrahamov 2015, p. 143). Even to indicate transcendence—the

unlikeness of God to everything—the Qur’an uses the term “like”. This means not only that transcendence must be balanced with immanence but that transcendence

as transcendence contains immanence. The same goes with the discussion of immanence as well. We will slowly see that what emerges through this is not only Ibn ʻArabī’s staging of a binary to later dissolve but rather his staging of a quaternary to later dissolve.

It is at this level of gesturing and dissolving the quaternary of transcendence and immanence that Ibn ʻArabī truly presents us with a

transimmanence, the precise meaning of which will slowly emerge in our discussion. What exactly is Ibn ʻArabī’s logical rationale in insisting on this dynamic dialectical operation? In the chapter on Elias, he gives an explanation which keeps to this dialectical notion. He argues that excessive transcendence is also a kind of likening (

shabahah) (or immanence), for it likens the Real to the mental notion of transcendence. Likewise, excessive immanence turns the Real into a being among beings in the world.

3 He states it like this: “The religions made God transcendent, likening Him (

shabbaha) in His transcendence (tanzīh) through imagination and making Him transcendent (

nazzaha) in His immanence (tashbīh) through the intellect” (

Abrahamov 2015, p. 142). He goes on to say, “They describe God in terms of their rational perception. God placed Himself above their (perception) of His transcendence, because they limit Him by that transcendence, for their intellect is unable to perceive the (true) transcendence” (

Abrahamov 2015, p. 143).

True transcendence, then, is one that must transcend transcendence itself. Because this un-transcended transcendence is only an immanence in disguise—a transcendence that is immanent to the very notion/concept of transcendence—it leaves nothing of non-immanent

excess.

4 BC Hutchens’ useful notion of open-immanence as opposed to closed-immanence is useful here. However, I would like to reinterpret its meaning within Ibn ʻArabī’s system. Hutchens, in his work on Jean-Luc Nancy (

Hutchens 2005, p. 44), states that “the incessant strangeness of the presentation of the “world”, is constitutive of the open immanence of the world.” Ibn ʻArabī’s notion of the ever-freshening and renewability of the world of forms (

Chittick 1989, pp. 103–6) resonates closely with this sense of “the incessant strangeness” and “multiple reticulations” (

Hutchens 2005, p. 99) of sense. Along with this sense of open-immanence, I would like to add a term of my own: closed-transcendence (as opposed to open-transcendence). It is the combination of open immanence and closed transcendence that gives us the transimmanent structure of Ibn ʻArabī’s understanding of Reality. In this understanding, the immanence in question must not be reductively self-contained but should open itself to its own excess (this is the transcendence of the immanent), while transcendence must allow for self-expression, self-delimitation and manifestation in the immanent (this is the immanence of the transcendent). An intricate (and mutually implicating) relational ontology develops here instead of a rigid dichotomy of the immanent and transcendent domains. Catherine Keller would likely describe this relational way of looking at Reality as a “break out of the closed loop of immanence versus transcendence” (

Keller 2014, p. 80).

In the dialectic between immanence and transcendence, we have argued that Ibn ʻArabī’s position is one of transimmanence. Like Iain Thomson’s Heidegger, Ibn ʻArabī’s transimmanent position results from his understanding of the nature of wujūd and its plenitude and excess. It is important here to further clarify our definition of transimmanence before we move ahead.

In his text

Muses, Jean-Luc Nancy ascribes the function of transimmanence to art. He says, “art is the transcendence of immanence as such, the transcendence of an immanence that does not go outside itself in transcending, which is not ex-static but ek-sistant” (

Nancy 1996, pp. 34–35). Nancy’s transimmanence describes a transcendence that does not close the circle, that does not move outside the immanent constellation of meaning to some “metaphysical sky”. Rather, as Anné Verhoef puts it, “the experience that the world might have or be something more, that its meaning can be found from outside it, or this “outsideness of the world” should be understood as the inside of this world” (

Verhoef 2016). So, the sheer otherness—or, in Akbarian terms, the incomparability—of the world is not located somewhere outside; rather, all such incomparable outsides are constitutional aspects of the infinitely moving, flux-like, constantly freshening nature of the world itself. Ibn ʻArabī says in

al-Futūḥāt al-Makkiyya, commenting on the verse from the Qur’an about God constantly being upon a new task (Q. 55: 29), that “Some people do not know that at every instant God has a self-disclosure which does not take the form of the previous self-disclosure…They imagine that the situation is not changing, and so a curtain is let down over them…” (

Chittick 1989, pp. 105–6).

Ibn ʻArabī is keenly aware of an aspect of this dialectic that Nancy does not quite emphasise in the same way. To Ibn ʻArabī, the whole matter, when deconstructed, is a quaternary rather than a mere dialectic between two terms. How so? To posit a transcendence totally and incomparably outside (in a “metaphysical sky”) is in a concealed way to speak in the grammar of immanence because the whole matter is immanent to metaphysical logic. This is not the genuine transcendent inexhaustibility of being. There are two ways of avoiding this problem: transcendence can either be thought of as kenotic self-donation, or immanence can be thought of as opening up (through eik-stasis

5) from within itself into a transcendent beyond. A better way to explain this—one that captures Ibn ʻArabī’s innovative approach—is to think of open/closed transcendence and open/closed immanence. The term “closed-transcendence” was already hinted at above, and in what follows, we fully develop this quaternary.

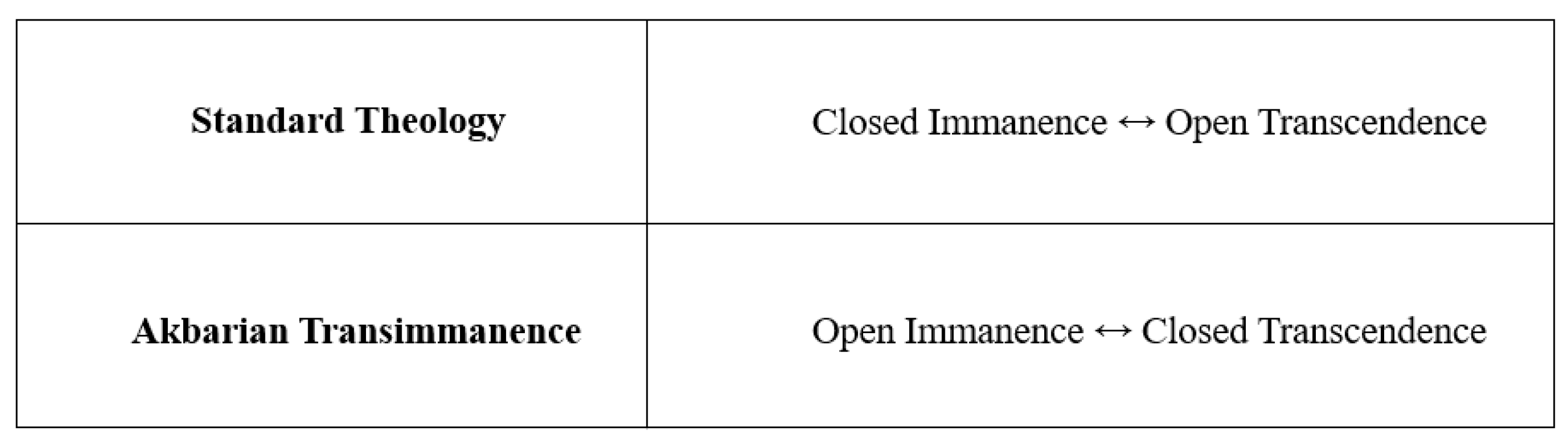

In the theological approach to this matter, we have a closed immanence and an open transcendence. In other words, the immanent world is self-enclosed—created and finalised—and separate from this is the transcendent source or ground, which is cut off from immanence and resides in a metaphysical sky. This is a case of closed immanence and open transcendence. Imagine open transcendence as an object going off ever rapidly into the metaphysical skies, incapable of being captured or sighted by any discursive apparatus that is immanent to this world. Open transcendence is on the outside of a sealed and totalised immanence. However, this open transcendence—opened out beyond in a metaphysical sky—is, in a hidden way, nothing but the closure of immanence and is intrinsic to closed immanence, as Ibn ʻArabī reminds us. Nothing of the paradoxical mystery of being remains in this simple scenario, so nicely calibrated according to metaphysical logic, nor can the immanent structures of meaning enjoy any interference from the mysterious beyond, which is always outside and different from them. On the other hand, a closed transcendence—a transcendence, in other words, that exhausts itself, that manifests itself in the world while also not being fully captured by it—makes possible an open, paradoxical immanence where transcendence is embedded in the world of meaning.

Here is our quaternary. Standard theology: Closed Immanence ↔ Open Transcendence. Akbarian Transimmanence: Open Immanence ↔ Closed Transcendence. The diagram below (

Figure 1) pictures this interrelationship.

Reality (

al-ḥaqq) here is understood by Ibn ʻArabī in terms of transimmanence. What are the political-hermeneutical implications that follow from this? The chapter on Noah in the

Fuṣūṣ gives us a clear picture of this pluralism in (hermeneutical) action. The chapter begins with a paradoxical assertion: “The Real is manifest in every created and comprehended thing,

and He is hidden from all comprehension…” (

Abrahamov 2015, p. 36; emphasis mine). Ibn ʻArabī then explores this elusiveness of the Real, which escapes all definitions precisely by taking up plural forms and meanings. He says, “the definition of the Real is not known, for His definition cannot be attained except through the knowledge of every form, which is impossible. Therefore, the definition of the Real is inconceivable” (

Abrahamov 2015, p. 37). This inconceivability and excess of the Real, though, should not be understood in a quantitative sense. As though it were possible somehow—through some miracle or technological advancement—to contain the Real if we could contain every cosmic form. The Real is impossible to pin down—is incomparable and transcendent—not because He is in a distant sky but because He is so close. The excess of the Real, then, is its utter closeness to everything; this distant-closeness is precisely what animates and makes the cosmic forms themselves possible.

It is this understanding of the excess of the Real that allows for the ontological pluralism of the chapter on Noah. The paradox of the inconceivability of the Real as the basis of all conceivability is a common trope in Sufi poetry and is usually stated in the relationship between veiling and unveiling. The veiling of the Real—its inconceivability—is precisely

through the unveiling of different entities in the world. In his study of Jāmi’s poetry, Chittick states, “The veil conceals the secrets, but no secrets can be grasped without the veil. As Jami and many others put it, to see the veil is itself to see God’s face, displaying itself through the veil” (

Chittick 1999, p. 60). The veil is the only window through which the Real can be glimpsed because the Real “only moves from veil to veil” (

Almond 2004, p. 19). Like Nancy’s position that transcendence does not show itself in a space outside the structure of the immanent world, so too does the Akbarian position hold that the Face of God does not present itself except from behind a veil.

6 As Robert Dobie puts it wonderfully in his reading of Ibn ʻArabī and Meister Eckhart’s “mystical hermeneutics”: “God is the dark, nonmanifest ground that makes possible all self-manifestation and all self-disclosure. God resists all attempts to make him or his Essence an object of reason, as the mirror resists all attempts to be seen” (

Dobie 2010, p. 169).

Before heading to the next section, we must mention here the important work of Gregory Lipton. His

Rethinking Ibn ʻArabi (

Lipton 2018) offers the most pertinent challenge to our construction of pluralism based on the Akbarian transimmanence framework. Is our construction of pluralism from the Akbarian understanding of

wujūd divorced from Ibn ʻArabī’s cosmological vision and his politico-historical context? Lipton shows instances of religious absolutism and supersessionism in Ibn ʻArabī’s work. I have no reason to deny such instances, nor does my argument function “within the Schuonian interpretative field” (

Lipton 2018, p. 8). We have not made any universalist claim about the validity (or otherwise) of all religious paths, nor a denial of particular and

different forms at the altar of an underlying

sameness (which implicitly is absolutist and exclusive regarding religious paths that adhere precisely to form and difference (

Lipton 2018, pp. 17–22)). Our ambition is rather humble. In an almost literal and textually focused—and yet ontologically serious—consideration of Akbarian transimmanence, we have hinted at its pluralistic possibilities from within. Ontological pluralism merely (and humbly) asserts: given that no system can fully contain the transcendent, one’s attachment and identification with that system must proceed hand in hand with a sensitivity that there could be other systems and worlds of meaning to which this uncontainable transcendence could flood over. This ontological pluralism is borne out of the Akbarian ontological scheme. What this means is that one’s identification and commitment to one’s own path or tradition is tensioned and is rich with a burden of sensitivity and responsibility to the Other. This tension precedes all questions of truth or untruth of other paths and traditions. This tension—reflected at a higher register in the very structure of transimmanence—is the precondition for all genuine dialogue and deep appreciation of the Other. In a later section, we see how Dārā Shikōh embodies such an approach. No such dialogue is possible without this tension that

always already troubles total self-coincidence.

If Lipton’s critique of the Schuonian interpretative field—with all its 19th-century racialist and Aryanist underpinnings (

Lipton 2018, pp. 122–49)—does not apply to our approach, would not at least his critique of metaphysical decontextualisation be relevant? I accept Lipton’s critique of the relativism entailed by the universalist discourse—a relativism in sheep’s clothing, hiding the wolf of absolutism—and his emphasis on contextualising the thinker and his ideas in his historical and political milieu. However, I think that the

waḥdat al-wujūd framework has both a

history and a hermeneutical

future. Let me explain this with a representative moment in Lipton’s text. In his text (

Lipton 2018, p. 9), Lipton mentions Sayafaatun Almirzanah’s statement (

Almirzanah 2011, p. 213) that Ibn ʻArabī’s metaphysical approach “is very essential in enhancing interfaith dialogue and acceptance of different religious perspectives.” Lipton’s critique of such attempts at using the Akbarian metaphysical approach for interfaith dialogue and acceptance is that they fail to see certain moments in Ibn ʻArabī that can be characterised as exclusivist supersessionism. Lipton argues this happens because Ibn ʻArabī’s metaphysics is often divorced from his historical and political context by these kinds of analyses. Though there is merit in what Lipton is cautioning us against, it is noteworthy that Sayafaatun Almirzanah, who carries forward Ibn ʻArabī’s metaphysical approach, has a context too! He is thrown into a global context, where one cannot pretend that Kant and Schleiermacher have not already been sedimented in the very discursive vocabulary that we collectively use. Our task cannot be to deny these sedimentations, but rather to critique and rethink them from within that discursive field.

Thus, Almirzanah’s context is no less important in considering the efficacy of Ibn ʻArabī’s metaphysical approach than the 13th-century context of Ibn ʻArabī. In failing to attend to Almirzanah’s own context as he employs Ibn ʻArabī’s approach in a globalised world of religious conflict and misunderstanding, and in the current existential need for harmonious human engagement, we implicitly forget that Ibn ʻArabī’s approach is not simply an ossified object to be studied by us moderns but is itself a powerful theoretical lens with which to approach and understand our current situation. This does not decontextualise Ibn ʻArabī but rather takes context more seriously! It does this by constantly rethinking what context means and enlarging its historical ambit. Just as Ibn ʻArabī’s metaphysics cannot be divorced from his historical and political context, the 13th-century historical context of this metaphysics cannot be divorced from its historical mediation through the centuries down to Almirzanah’s own 21st-century context. The sections on the South Asian Sufis in this paper are an effort to think through this mediation down the centuries.

4. The Excess of Being: Sufi Hermeneutics as Work of Art

Milad Milani’s novel approach to the study of the ontology of Sufism makes use of Heidegger’s notions of in/authenticity from Being and Time, the strife characterising the work of art from his 1935 essay, and the notion of inception or Anfang that dominates his thinking throughout the 30s. I argue that the guiding thread in Milani’s argument, however, still remains the Akbarian transimmanence framework. We first set up Heidegger’s overall approach in the artwork essay and then explore Milani’s argument to establish this point.

Heidegger’s lifetime of thinking is dedicated to putting the question of being (

Seinsfrage) at the centre of philosophical inquiry. What, however, and finally, is being for Heidegger? We can answer this question using the 1935 essay “The Origin of the Work of Art”: the text that is the focus of this section. However, preliminarily, Lawrence Hatab’s definition of Heidegger’s being is useful in setting up our theoretical orientation. He writes (

Hatab 2016, p. 14):

being understood as the temporal structure of the emergence of meaning, which is finite in being infused with absence, concealment, and limits, which is gathered in language, and which exceeds beings, ourselves included, as the processual environment in which human beings find themselves and dwell in disclosive understanding.

Being is here understood as that which exceeds beings while also being the environs in which beings dwell in “disclosive understanding”. Being as excess allows the opening for disclosure of a world of understanding and intelligibility. So, this excess is not some escape into the sky where metaphysics can go hunting for it; rather, paradoxically, this excess is the very space—the very earth—where meaning and interpretation occurs. It is important to register the pregnant paradox here: how can that which exceeds—and how can this very excess—be that in which we dwell in our meaning-making? Later in this section, we unpack this paradox in Milani’s innovative use of it in understanding Sufism. The interpretive lens for us continues to be the notion of transimmanence. How transimmanence in the Akbarian framework is useful in understanding the paradox of being’s excess shall become clear.

For Heidegger, the work of art is the site for the strife—or dynamic interplay—between the earth and the world. The world can be understood as the constellation of meaning or intelligibility, the opening and disclosure of significance in which the human being goes about in its meaning-making. This is the immanence of meaning in the structure of the world. Taking Heidegger’s example, Van Gogh’s “peasant shoes” is the site where the peasant’s world of meaning shines out. The earth, on the other hand, represents the dark concealing—the excess—that provides the ground out of which the world (and so meaning and intelligibility) juts out. In our discussion of transimmanence in the previous section, one could think of the earth as the principle of transcendence and the world as the principle of immanence where meaning is immanentized. How exactly should we understand the transcendence of the earth?

As already pointed out, genuine transcendence cannot be situated somewhere up in a metaphysical sky. Transcendence must exhaust itself and allow itself to be taken up by a world of meaning (outside of which, Nancy holds, nothing exists). However, transcendence cannot merely be equal to the world of immanence; it cannot fully exhaust and express itself in the immanent world and thus be totalised without remainder. That would make immanence into a closed immanence. So, it can neither stand out of the world nor be totally absorbed in and identified with it. Thus, the non-totalizable excess of transcendence is preserved precisely in the internally riven nature of immanence itself, allowing for other possibilities of meaning-formations. This is how the principle of transcendence—the earth in the artwork essay—allows and refuses itself to be fully captured by a constellation of meaning. The term otherwisability captures in full this “never entirely conceptualizable excessiveness”. Transimmanence allows for other(wise) possibilities beyond and yet through the world’s own immanent structure of meanings.

As Heidegger puts it in his essay, “The self-seclusion of earth is not a uniform, inflexible staying under cover; rather, it unfolds itself in an inexhaustible abundance of simple modes and shapes” (

Heidegger 1971, p. 47). Iain Thomson comments on the meaning of the earth in these terms: ““Earth,” in other words, is an inherently dynamic dimension of intelligibility that simultaneously offers itself to and resists being brought fully into the light of our “worlds” of meaning and permanently stabilized therein, despite our best efforts” (

Thomson 2011a, p. 89). Heidegger describes the strife of the earth and the world in terms very similar to the transimmanence we discussed: “The world grounds itself on the earth and the earth juts through the world… The world, in resting upon the earth, strives to raise the earth completely [into the light]. As self-opening, the world cannot endure anything closed. The earth, however, as sheltering and concealing, tends always to draw the world into itself and keep it there” (

Heidegger 1971, p. 49). Iain Thomson calls this strife an “

a-lêtheiac struggle between concealing and revealing” (

Thomson 2011a, p. 93). He further explores Heidegger’s notion in these words, “As “earth,” in other words, intelligibility tantalizingly offers previously un-glimpsed aspects of itself to our understanding and yet also withdraws from our attempts to order those aspects into a fixed meaning. As “world” we struggle nevertheless to force a stable ordering onto this inexhaustible phenomenological abundance, however temporarily” (

Thomson 2011a, p. 93). However, it is not as if earth and world are two distinct entities; rather, they represent the dynamic nature in which the structure of intelligibility presents itself. We can think of this “

a-lêtheiac struggle” in terms of transimmanence. The earth is the transcendence element, the phenomenological excess, that is intrinsic to the unstable and internally riven immanence of all structures of meaning represented by the world. The earth is not in an outside world—in a metaphysical sky—but rather is the very instability and excess immanent in a world of meaning.

Milad Milani presents Sufism as problematic, and it is this problematic nature of Sufism that leads to the polarisation of the Sufi experience into the sober and intoxicated schools (

Milani 2021, pp. 55–56). In the history of Sufism after al-Junayd (d. 910), Milani argues, there was an institutional appropriation of the explosion of the event of Sufism, which he sees as coextensive with “the Hallaj-event” (

Milani 2021, p. 21). Through this appropriation, the transgressive (or excessive) possibilities of Sufism were curtailed and delimited (into a stable world of meaning). However, in the tradition of love—what he calls “the religion of love”—this excessive dimension always remained. The term “transgressive” used above, though, should be understood in a philosophically deeper sense, and it is here that Milani makes use of Heidegger. The event of Sufism is like Heidegger’s work of art, he claims, where the event opens up multiple interpretative possibilities and potentialities immanent to the Sufi’s Muslim way of being. In this, the excess and its always non-total stabilisation engage in perpetual strife. Milani puts the matter clearly in his definition of the Sufi: “The Sufis, no matter how antinomian or innovative, never cease to remain Muslim; and where in such rare cases we might discover unorthodox behaviour, being Muslim is never about Muslim identity, but a Muslim

becoming. Being Muslim, in this sense, is about a continual realisation—without end—of what it means to succumb to the will of God as ontology” (

Milani 2021, p. 61).

The transgression here is to be understood in the sense of the potentiality for

other interpretative and existential avenues. This is what Milani calls “the ontology of faith as a

possibility of being over and above the Islamic

actuality of being” (

Milani 2021, p. 87; emphasis mine). Milani has in mind, of course, the Heideggerian dictum “higher than actuality stands possibility” (

Heidegger [1927] 1962, p. 63). That which is concealed in the unconcealed—the potentially rich

lêthê in

a-lêtheia—is what is emphasised here. This is how Milani uses this Heideggerian strife in studying Sufism: “So, it always appears that Sufism is Islamic, but it does not cease to be affected by what Heidegger described as ‘strife’, because the ‘denial’ aspect of the double concealment that has been underlined is always and necessarily the condition of its being” (

Milani 2021, p. 143). What is emphasised here is the unsaid aspect in what is said (the veiled

in excess of what is unveiled). The unsaid (earth/transcendence), as the non-totalisable manifestation of what is said (world/immanence), is always at the point of tearing at the seams of the immanent. This, in a different register and vocabulary, is precisely the transcendent dimension embedded in the immanent, it is the ever-renewability of open-immanence. This does not mean—in a facile way—that what we are after is the transgressive un-Islamic dimension of Sufism, but our interest rather is the

otherwise potentiality that is immanent to the Islamic: potentialities that explode as

beyond but from

within and

throughout the Islamic. Milani’s description of the a-lêtheiac struggle of the Ḥallāj-event as a work of art proceeds like this: “The work of art…is in itself capable of opening up new possibilities of perpetuating the mood of what it is to retain authenticity. Similarly, the strife implicit in the experience of al-Hallaj is the very clearing that allows for things to occur anew” (

Milani 2021, p. 88). Note how this comes close to how Iain Thomson defines Heidegger’s being in terms of “a never entirely conceptualizable excessiveness”.

5. Dārā Shikōh and the Majma‘ al-Baḥrayn

As we saw, Milad Milani, in his new text on the ontology of Sufism, says that the Sufi herself can be seen as a work of art. I argue that the Sufi’s understanding of being is a work of art. The transimmanent structure of this understanding, within an Akbarian framework, leads to a pluralistic position regarding other worldviews. As we have seen in the last section, this involves a dynamic rift and interplay between the world (the constellation of intelligibility) and the earth (the transcendent excess), which shows itself as the world while not being exhausted by it.

Dārā Shikōh’s pluralism is based on this

waḥdat al-wujūd framework of understanding the nature of reality. His sense of the excessive nature of being is one that transcends (while also inhering in) every delimitation and description that one can give it. One of his most pointed expressions of this uncapturable—and thus plural—understanding of the Real is the statement that he quotes from Lāl Dās to the effect that “Truth is not the monopoly of any one religion” (

Dārā 1998, p. 27). He is particularly fond of this Hindu sage for whom he has these estimable words in his text

Hasanāt al-ʻĀrifīn, “Bābā Lāl Mandiya is one of the perfect ʻĀrifs, and I have seen none in the Hindu community who is equal to him in majesty and firmness. He told me, ‘There are ʻĀrifs and perfect (divines) in every community through whose grace God grants salvation to that community’” (

Dārā 1998, p. 24). Dārā Shikōh extended this open-mindedness towards all religions. Like his forefather Akbar, Dārā’s “fascination with other religions” was due to his “quest for the unifying truth behind all religions” (

Cohen 2018, p. 276). In fact, so far as the Indian religions are concerned, Dārā Shikōh’s period saw the flourishing of what Carl Ernst has dubbed “the translation movement” where the “Mughal Muslim nobles patronized and facilitated the translation of numerous Hindu Sanskrit treatises—including, among others, the Atharva-Veda, various Upanisads, the Ramayana, the Mahabharata and Bhagavad-Gita, and a number of the Puranas—into Persian, the official administrative language of the empire” (

Nair 2014, p. 391).

Though the specific cultural and historical context of the Mughal court and its political requirements influenced this approach to the other religions (

Kinra 2013,

2020;

Elverskog 2022;

Moin 2022), one should not forget the Akbarian philosophical framework of transimmanence which facilitated this approach for Dārā. In his

Majma‘ al-Baḥrayn, for instance, he discusses the Akbarian dialectic of

tanzīh and

tashbīh (

Dārā 1998, pp. 54–57), which we have studied in detail above. In fact, he distinguishes between the apostleship or prophecy which is one-sidedly focused on

tanzīh or

tashbīh, and the perfect prophethood (the prophethood of Muhammad) that combines together

tanzīh and

tashbīh. For him, the perfect Qur’anic exemplar of this dialectic (or quaternary) of

tanzīh and

tashbīh is the statement, “There is nothing like His likeness: He is the All Hearing, the All Seeing” (Q. 42.11;

Abdel Haleem 2005, p. 312 (modified)). From this, it is clear that Dārā has Ibn ʻArabī’s

Fuṣūṣ al-Ḥikam in mind. Thus, it is not just the expedience of Mughal culture or the personal preferences of a Mughal prince which is in question here, but rather a whole politics of interpretation that is born out of a particular understanding of

wujūd—one that allows for plural and inexhaustible possibilities when thinking of Reality. Thus, a pluralism of interpretation results from a metaphysical understanding based on the dialectic of transcendence and immanence. Indeed, it is this framework that allows the school of Ibn ʻArabī to think of an authentic (but not necessarily post-modern) ontological pluralism.

Without the notion of transimmanence, there is always the risk of confusing this pluralism for an empty relativism, where every proposition about reality can be seen as equally true. However, the point in ontological pluralism is the possibility of other fundamental truths, not the truth of every possible position. This is an important distinction, and even this distinction directly depends on the notion of transimmanence. In what follows, we outline how this is so.

Dārā begins the

Majma‘ al-Baḥrayn by praising God and describing Him as having adorned His Face with the two locks of faith and infidelity while allowing neither of these to cover the beauty of His Face (

Dārā 1998, p. 37). If we recall our discussion of the earth and world from Heidegger’s discussion of the work of art, we can see how the dynamism of faith-infidelity covering

and failing to cover the Face works here. It is like the earth that offers and allows the formation of the world while simultaneously resisting it. This simultaneity is the important clue to the structure of transimmanence—faith-infidelity, at once, adorn but fail to fully cover the Face. It is the Real’s refusal to be exhausted by the world of forms (while also manifesting itself through them) that allows the world of forms to have any life at all. Reality’s excess that refuses to be fully covered by these forms is precisely what allows forms to have their reality. “He is manifest in all”, Dārā says (

Dārā 1998, p. 37), but in Dārā’s Akbarian framework, the corollary must also hold that nothing can quite manifest Him at all. This refusal to be fully manifested—this refusal to flood the world with His blinding light of being—is what allows the world of forms to have their borrowed being. Now, we return to our question—how does this transimmanent structure in Dārā Shikōh (and Ibn ʻArabī) help us to avoid the trap of bland relativism?

Shankar Nair in his study of the Mughal translation movement correctly argues that in the distinction between form and reality (“

ṣūrat” and “

ḥaqīqat”) in these Sufi mystical treatises the importance of form should not be overlooked. He quotes, for instance, Findiriskī’s couplet on the

Yoga Vāsiṣṭha as follows (

Nair 2014, p. 394):

This discourse [i.e., the Laghu-Yoga-Vāsiṣṭha] is like water to the world; pure and increasing knowledge, like the Qur’ān. Once you have passed through the Qur’ān and the Prophetic sayings, no one has sayings of this kind. An ignorant one who has heard these discourses, or has seen this subtle cypress-grove Attaches only to its outward form (ṣūrat); thus, he makes a fool of himself.

After quoting several passages from Findiriskī that suggest that the different religious dispensations all point to a single underlying reality, Nair notes an interesting point. He points to the line “once you have passed through the Qur’an and the Prophetic sayings” in the above laudatory passage. Nair argues that this is similar to “Dara Shikuh’s self-description of having turned to the study of Sanskritic materials only after having already, personally, attained the highest realisations and realities of the Sufi path” (

Nair 2014, p. 397). In discussing this, Nair asks the question, “Would Findiriskī say that the Laghu is an equally profound manifestation as the Qur’an?” If the answer to this question is in the affirmative, then we have a case of relativism. It would mean that there is no essential difference between the Qur’an and the Laghu, except in a formal sense. This would mean that one’s adherence to one or the other is the accidental result of being born in a certain tradition. However, at the same time, is it not true that the underlying Reality to which the relative forms point is the same One, whether we hold on to the Qur’an or the Laghu? Nair is correct in answering this question by stating, “Forms cannot be haphazardly equated in the here-below” (

Nair 2014, p. 398). In other words, as we can recall from the previous section, form does not just open up into the formless; the formless simultaneously unveils itself in the forms. The two then have a dialectical interrelationship. From the quote from Nancy, as we saw above, we can note that there is a transcendent dimension inhering in the immanent; therefore, there is something of the transcendent in the immanent. Forms that are immanent to our world “here-below” are not simply disposable, nor can they be, in Nair’s words, “haphazardly equated in the here-below”. In fact, the modern hermeneutical tradition precisely emphasises the importance of form, which it believes that traditional metaphysics has always ignored. However, this importance of form has always been central to Sufi metaphysics as well (

Zargar 2013).

Thus, the fact that the Real refuses to be exhausted by one form—making that form the only truth and thus leading to closed immanence—does not thereby mean that all forms are equally and haphazardly valid. Pluralism would rather insist on the

possibility of other manifestations of reality rather than on the

actuality of the truth of every manifestation of reality.

7 Thus, when Dārā Shikōh quotes in his

Majma‘ al-Baḥrayn the verse, “Faith and Infidelity, both are galloping on the way towards Him” (

Dārā 1998, p. 37), he does not deny that infidelity is infidelity, a denial that would be tantamount to his renunciation of Islam.

Majma‘ al-Baḥrayn, with all its endeavours to find resonances between Sufism and Vedanta, bears full testimony to the fact of Dārā Shikōh’s being a pious Muslim. However, his Muslim identity allows him a pluriform conception of truth; his Muslim

identity, through his transimmanent understanding of being, is, in fact, a Muslim

becoming, to use Milani’s term. This interpretive pluralism—which looks at Sufism and Vedanta as “two truth knowing groups” (

Dārā 1998, p. 38)—is made possible by the transimmanent Akbarian framework. This ontologically inspired pluralism—which is based on dialogue and tolerance and yet the maintenance of self-identity—and its distinction from bland relativism is brought out more starkly in an anecdote about Dārā Shikōh’s execution. He is believed to have been asked by the court to draw firm doctrinal boundaries between the religions. To this, he is believed to have responded, “How can you draw a line in water?” (

Kent and Kassam 2013, p. 3). We should remember that even lines drawn on water are lines and are affirmations of form and identity, and yet at the same time, they are indicative of an identity that is ever subject to imminent erasure and renewal, ever moving and becoming.

This brings us to a more difficult case, that of Sarmad Kāshānī, the friend and teacher of Dārā Shikōh, in whose case the limits of pluralism are stretched to the uttermost limits.

6. Sarmad Kāshānī and Rootless Pluralism

We began our study by defining ontological pluralism from Iain Thomson’s reading of Heidegger. We argued that it would be incorrect to locate the post-Nietzschean history of Western philosophy as a unique moment where an ontologically pluralist perspective took root. Such plural interpretative politics, based on a vision of being which exceeds all our possible discursive structures, can be found in the Akbarian tradition as well. We saw how in this tradition a transimmanent understanding of being played a role in dealing with other religious traditions and principles. In the previous section, we saw how this translates in the medieval Indian landscape with Dārā Shikōh. In this section, we move on to a more difficult figure: Sarmad Kāshānī.

Sarmad’s grave is located at the foot of the Jāma Masjid in Delhi, where he shares his resting place along with his teacher Khwāja Syed Abul Qāsim (also called Hare Bhare Shāh). It is an unassuming grave, but one that is open for everyone and visited by members of all faiths. Like so many of the

mazārs or tombs of the Sufis—representing the traces of their lives and deaths—Sarmad’s grave is a space of

lived pluralism. Anna Bigelow frames this phenomenon well, discussing the shrine of another saint, when she says that the tomb functions as the site “for the performance” of a “collective identity based on interreligious harmony” (

Bigelow 2022). In another text, she speaks of the

dargāh of Haidar Shaykh, where “the simultaneous presence of Sikhs, Hindus, and Muslims challenges notions of definite and definable boundaries between religions, countering the expectation of interreligious communal conflict in South Asia” (

Bigelow 2010, p. 20). The challenging of definite and definable boundaries harks back to Dārā’s notion of drawing a boundary on water or Milani’s notion of identity as becoming. Bigelow also makes use of the notion of attunement, which has vague Heideggerian resonances, in describing these plural spaces. She states that “much of what happens practically in a shared sacred space is a kind of

spatial attunement in which pilgrims consciously and unconsciously adjust to and accommodate one another” (

Bigelow 2010, p. 21). Such a spatial attunement takes place at a larger cultural level as well. Jonathan Gill Harris describes the boundary-dissolving spiritual praxis of Sarmad Kāshānī as part of the Silk Route spirituality, where historically an accommodating and interreligious harmony was part of the attunement. Harris characterises this spiritual praxis as one of “committed rootlessness” (

Harris 2015, p. 221), of embodiment in “border zones” (

Harris 2015, p. 220), and of “constant movement between identities” (

Harris 2015, p. 228). Sarmad represents, in other words, the exemplary case of Milani’s identity as becoming.

Therefore, our discussion of the Akbarian understanding of being is relevant to our discussion of Sarmad. He was born into a Jewish Armenian family (

Harris 2015, p. 212) and became a Sufi and Yogi in his life when his business travels brought him to India. En route, he spent time as a student of both Mīr Findiriskī and Mullā Ṣadrā in Iran (

Prigarina 2012, pp. 316–17), and in India became a teacher and confidant to Dārā Shikōh (

Prigarina 2012, p. 317). Yusuf Husain Khan, in a 1964 article on Muḥibb Allāh Ilāhābādī, claims that Sarmad Kāshānī (along with Mian Mīr, Mullā Shāh, and Dārā Shikōh) belonged to the

waḥdat al-wujūd school (

Khan 1964, p. 315). Shankar Nair, however, sees this pitting of the

waḥdat al-wujūd school in one monolithic camp as a form of reductionism (

Nair 2020, pp. 92–93). Another way of categorising Sarmad, however, could be in terms of his religious or mystical praxis. Annemarie Schimmel, for instance, says of Sarmad: “He followed the tradition of Hallaj, longing for execution as the final goal of his life…This idea goes back at least to Aynu’l-Qudat Hamadhani” (

Schimmel 1975, pp. 362–63). From his antinomian praxis of nudity, Nair sees him as belonging rather to the Nātha yogis than to proper Islamic Sufism (

Nair 2020, p. 114), though he does entertain the fact of his discipleship with Mīr Findiriskī (

Nair 2020, p. 215).

Reading the quatrains of Sarmad does give us the impression of a devoted Muslim, albeit with antinomian tendencies. His homoerotic engagements with the Hindu Abhai Chand—though externally against the

sharī‘a—is metaphorically read by Harris as exemplifying a profane portal to the sacred (

Harris 2015, p. 225), much like the use of the metaphor of wine in ʻUmar Khayyām and Ḥāfiẓ.

8 Yet, a distinctly queer spirituality cannot be (and need not be) metaphorically explained away in Sarmad’s “double defiance” (

Sikand 2003, p. 180) in loving a Hindu boy. However, as we noted, despite his antinomian tendencies, his quatrains suggest a strong sense of

Muslim piety.

9 For instance (

Sarmad 1991, p. 67):

You desired happiness

But only in this world.

You did not entreat God

For happiness in the other world.

At once you lost

Both worlds

And all you were left with was

Lifelong repentance.

Thus, there is a contradictory tendency in his poetry that cannot simply be understood by a biographical study of his life. For one thing, it appears from what little we know about his life that he was a religious scholar of the Torah and the Qur’an and knowledgeable in Hebrew and Farsi. In fact, the entry on Judaism in the

Dabistān-i madhāhib involved substantial contributions from Sarmad (

Harris 2015, p. 223), making him an important participant in one of the earliest concerted efforts at a text on comparative religion in South Asia. For another, we simply know too little about his life, and a lot of this knowledge comes from the accusations of his detractors. Therefore, it is difficult to make a definitive conclusion, one way or the other. However, it is true that his poetry—though not an explicit rejection of

Muslim spirituality—does have a strong antinomian and self-contradictory tendency. For instance (

Sarmad 1991, p. 73):

I love madness, dynamism, but I am not distraught,

An infidel, an idolater,

I am not one of the pious.

I am going towards the mosque,

But I am not a Muslim.

How to explain this contradiction while also noting the importance of Nair’s dismissal of Sarmad?

10 It is here that Milad Milani’s explicitly Heideggerian engagement with the ontological dimension of Sufism is useful. Though Milani’s focus is on the supposed antinomianism of al-Ḥallāj (the representative of the religion of love par excellence), his analysis applies for Sarmad as well, who in Schimmel’s assessment might have had al-Ḥallāj as his model. Making use of Milani’s approach to the study of Sufism also means the utilisation of the transimmanent Akbarian framework. The latter, then, is not only an object of historical research but also a robust interpretative lens for charting new approaches for discovery and analysis today.

We saw that, in Milani’s study of the history of Sufism, a certain mystical dimension exploded within the tradition of Islam with the Baghdadi mystic Manṣūr al-Ḥallāj (which Milani refers to as the Ḥallāj-event). This explosive mysticism of al-Ḥallāj stands as the opening or clearing for potentialities that—through the very intensity of Muslim piety—point beyond the institutionally Islamic. This explosive dimension, however, is normalised and silenced through the institutionalisation of the mystical in the Sufi tradition starting with al-Junayd (one paradigmatic attempt in this is the division of Sufism into the sober and the intoxicated schools). Yet, the “problem of Sufism” in this explosive but concealed dimension always plagues the institutional history of Islam. Sarmad could be seen as a late example of this (representing a late Ḥallāj-event). This is so because Milani holds that there is something ontologically problematic about Sufism which always returns, resisting total institutional appropriation. So, after this quick summary, let us return to the question in Milani’s study: what is Sufism? He defines it thus, “The process of the unfolding of Sufism is one that is

through Islam, by which sameness and difference are experienced simultaneously” (

Milani 2021, p. 62). In other words, it represents the transcendent dimension in its very immanence in the Islamic. To put it differently, Sufism is immanent in the Islamic; however, this immanence is an open immanence: opening out into a dimension in excess of (and yet

through) the Islamic. It is, he continues, “phenomenologically the journey

through Islam and

beyond” (

Milani 2021, p. 63). It is both, to rework Milani’s wonderful apposition, analogous to Islam and in this very analogy an anomaly: its very likeness (immanence) opens to a concealed beyond. To quote Milani further, “Sufism, as we must conceive of it, needs to be thought of as a perpetual movement that is tradition-inspired and, at the same time, innovative. It is defined by the tension that describes it phenomenologically as both simultaneously continuity and discontinuity in relation to Islam” (

Milani 2021, p. 63). It is this perpetual movement—in Milani’s Heideggerian language—that helps us understand Harris’ description of Sarmad’s mystical praxis as “committed rootlessness”. Milani’s description of Sufism as dis/continuity with/in the Islamic is also what helps us understand the contradictions in Sarmad, especially in verses where he says, “I am going to the Mosque, but I am not a Muslim”.

I enlisted the help of Milani’s ontology of Sufism to see the life, death, and poetry of Sarmad within the transimmanent Akbarian framework and how this framework has enabled his pluralistic practice and the pluralism of his shrine today. It is a pluralism where the very combination of tashbīh and tanzīh—the co-incidence of dis/continuity or un/concealment—offers a view of reality that allows for the possibility of other possibilities and, thus, instils a plural politics of interpretation. Sarmad and his dis/continuity with the Islamic, with the contradiction that is intrinsic to his mode of spirituality, or his inhabiting a Barzakhi border zone can best be understood only from the framework of transimmanence. Though his own theoretical commitments cannot be ascertained from his work or biography, the pluralism that results both from his life and his death (and martyrdom) points to the need to understand being in terms of transimmanence.