Reconstructing the Archaeological Context of Free-Standing Buddhist Images: Considerations of the Wanfosi Hoard in Chengdu (Sichuan)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

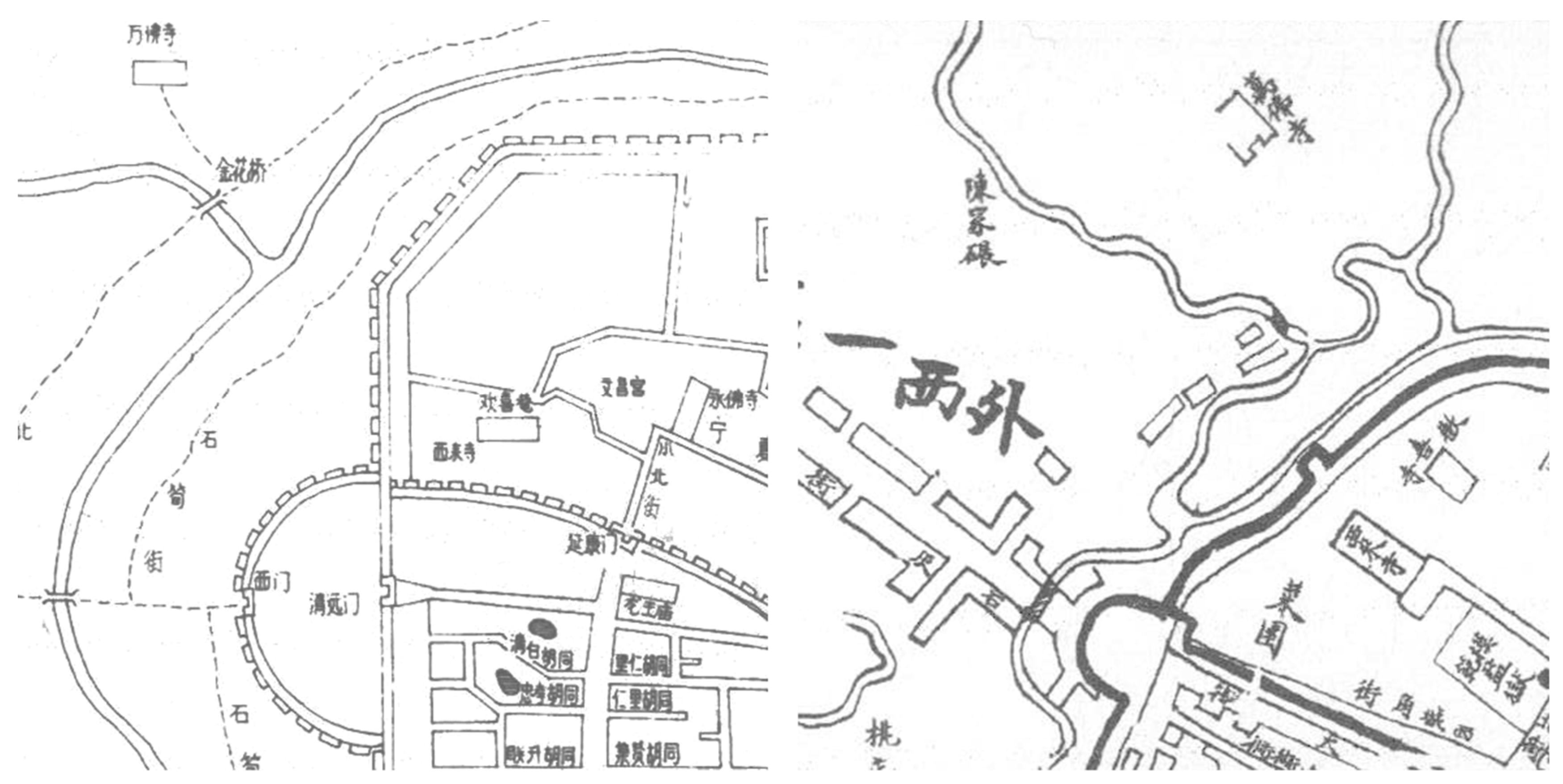

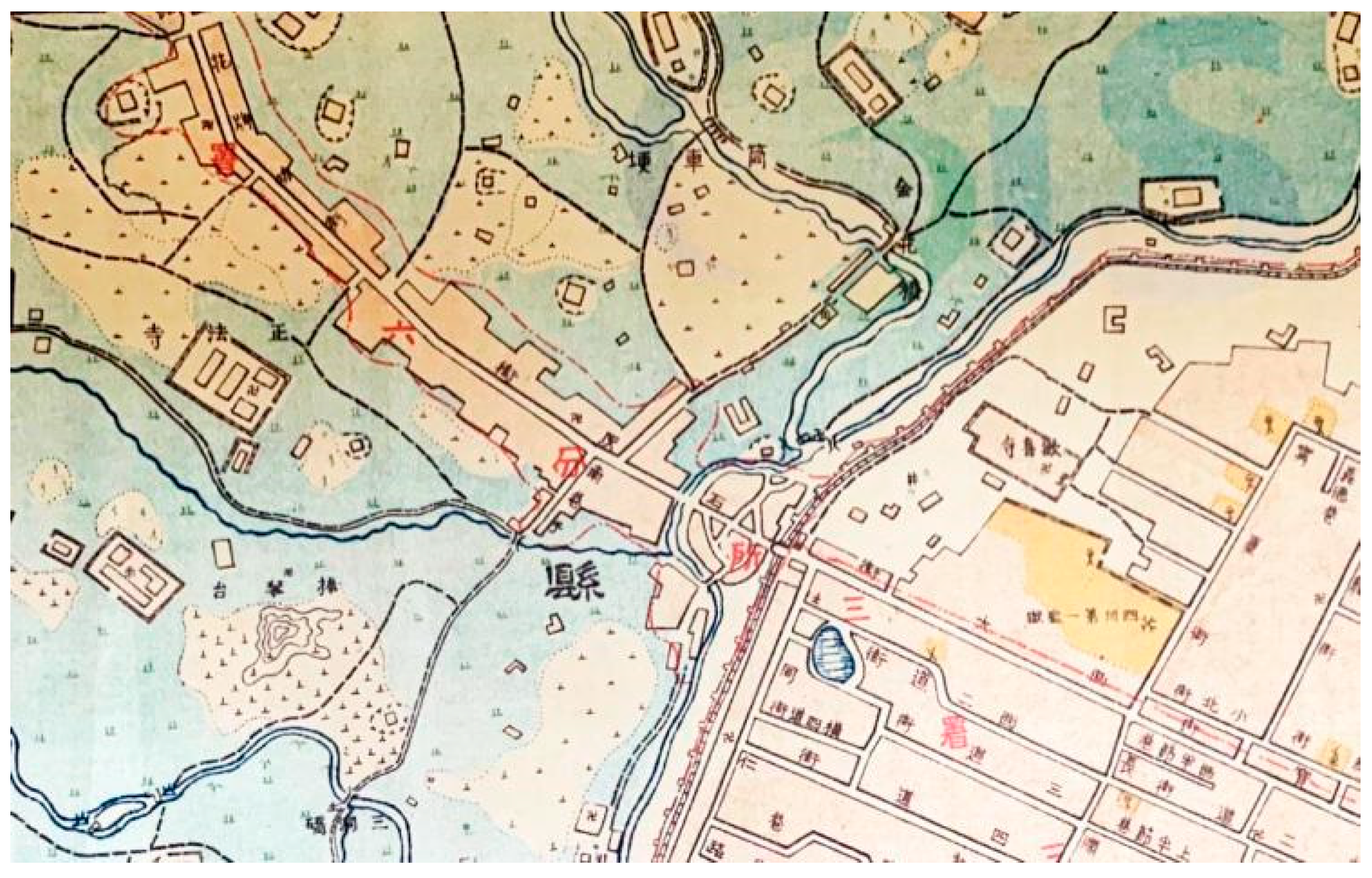

2. Precise Location of the Hoard

2.1. Records from Pre-Modern Sources

2.2. Clues from Modern Excavations

2.3. A Different Statement on the Wanfosi Location

All (stones) are headless, or, preserving the heads without bodies, and not a single (stone) was intact. This was what Shubi (Elegy of Shu) claims to be chiseled away by the Xian thieves. It was reported by two counties that the obtained (stones) reached a total of more than a hundred. The great man of the family [jiadaren, also known as “my father”, Wang Zuyuan 王祖源 (1822–1886)] commanded the localities to relocate (the stones) to present Xiao Wanfosi, he financed the restoration and had them fully repaired. (He) commanded us brothers to supervise the project, without spending one penny of official funds, or one penny of (collected) donations.

皆無首或有首無身, 無一完者, 蜀碧所稱獻賊鑿去者也. 兩縣來報, 出凡百餘. 家大人命地方移送今小萬佛寺, 出資重完且盡整之. 命余兄弟監其事, 不用官家一文, 一文不募.11

2.4. Discussion of the Location

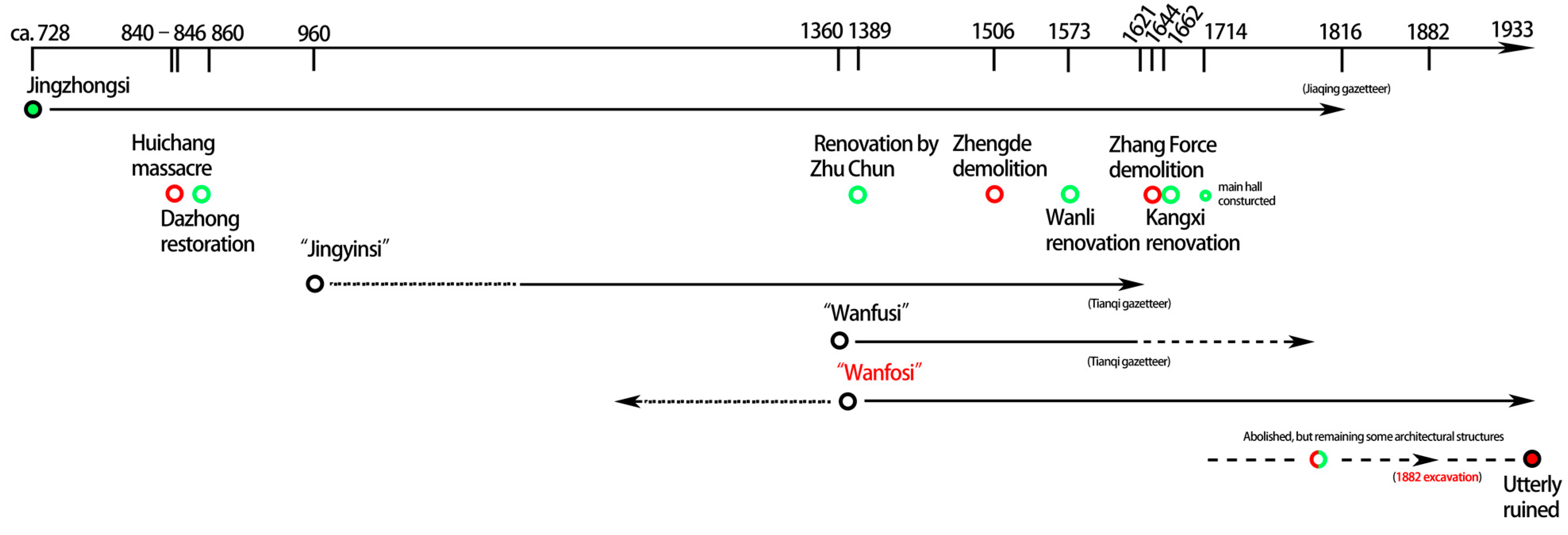

3. Historical Lineage of the Monastery Wanfosi

3.1. Ming and Qing Gazetteers

Jingyinsi (Monastery of Pure Cause), (located) to the northwest of the prefectural city, colloquially called Wanfusi.

淨因寺, 府城西北, 俗呼萬福寺.15

Jingyinsi, colloquially called Wanfosi, has recently changed its “fo” into “fu”. According to tradition, it was constructed during the Yanxi Era of Han (158–167). Some say that (Jingyinsi) is the ancient Jingzhongsi, which is located at the site of the ancient Zhulinsi. Chan Master Musang (Ch. Wuxiang, d. 762) of Tang built a stūpa and had ten thousand Buddhas sculpted, and the monastery was thus named. When later the stūpa fell into ruins, the Military Commissioner (Hucker 1985, p. 144, entry no. 777) Gao Pian (821–887) took (the bricks) from the stūpa and constructed the barbican… In the middle of the Hongwu Era (1368–1398), King Xian of Shu assumed (the post of) the kingdom, the (construction of the) palace had not been completed, (and he) frequently visited the place. The remaining images all existed, at that time (the monastery) was still called Zhulinsi. Monk Zhongxuan (J. Naka Era?) from Japan practiced Chan (meditation) there. The King of Shu was moved by his sincerity, with extra-money from (his revenue as) a Ming imperial prince,17 he made offerings of golden images, and placed the dharma treasure... In the middle of the Zhengde Era (1506–1521), the monastery was burned down by the roving bandits, only the halls remained unaffected… At the beginning of the Wanli Era (1573–1620)… It was the eighth month of the jiachen year (1694)… the repair and restoration were completed… At first, the King of Shu expended the state property, and ordered laborers to repair… which costed as much as three or four thousand maces of gold.

Jingzhongsi, (located) in the northwest of the county (town)… was named Jingyinsi in Song, and was renamed Wanfosi in Ming. There was an enormous bell, weighing a thousand jun, which is currently abolished.

Wanfosi, is located near Jinhua Bridge about one li from the sixth district to the west of the county town. Gaoseng Zhuan (records that), Monk Musang, who is from the Kingdom of Silla, in the sixteenth year of the Kaiyuan Era (728), arrived Chengdu. (Musang) collected alms from patrons, and constructed Jingzhongsi (Monastery of Pure Assembly). The Hall of Images existed therein. Later, (the monastery) that was formerly named Jingyinsi was renamed Wanfusi (Monastery of Ten-thousand Blessing) at the end of Yuan or beginning of the Ming. It was ruined by Xian, the heister (Zhang Xianzhong), in late Chongzhen Era. In the (current) dynasty of the nation, it was repaired during the early years of the Kangxi Era (1662–1722), and was renamed Wanfosi. In the fifty-third year of the Kangxi Era (1714), the main hall was built. There was an ancient bell of the Tang period, which was moved and placed in the Drum Tower during the years of the Yongzheng Era. For details, see Jinshizhi… Mingshengzhi (records that), Jingzhongsi has one enormous bell weighing one thousand jun. In the Huichang Era of Tang (840–846), it was destroyed without exception. The bell was thus moved into Taicisi (Monastery of the Great Mercy). In Dazhong Era, (it was) again returned.

萬佛寺, 縣西六甲里許金花橋側. 高僧傳, 僧無相, 新羅國人, 唐開元十六年至成都, 募化檀越, 造淨眾寺, 影堂在焉… 後故名淨因寺, 元末明初更名為萬福寺, 崇禎末毀於獻賊. 國朝康熙初年重修, 改為萬佛寺. 康熙五十三年建大殿, 唐時古鐘一口, 雍正年間岳鐘琪移置鼓樓, 詳見金石志… 名勝志, 淨眾寺有一巨鐘, 重千鈞. 唐會昌例毀, 此鐘乃移入太慈寺, 大中復還.24

3.2. A Misleading Quotation from Shubi

At that time, the (Xian) heisters established the Bureau of Casting, took the ancient ding-pots and entertaining utensils stored by the frontier office (Hucker 1985, p. 207, entry no. 1868), as well as the bronze images from the monasteries inside and outside the town, and melted them (into) liquid for (casting) cash coins, the characters on the coins read “Dashun tongbao”… All heads of the sculpted divinities did not change, although they were forged a hundred times. In the end, the thieves discarded them. Later, the Prefect of Chengdu of the current dynasty Ji Yingxiong (juren 舉人 1642) collected and buried them outside the north gate, the title of his tablet reads “tomb of the Buddha”.

是時賊設鑄局, 取藩府所蓄古鼎玩器, 及城內外寺院銅像, 熔液為錢, 其文曰“大順通寶”… 諸神像首, 百煉不化, 賊盡棄之. 後本朝成都知府冀應熊拾而埋之北關外, 題其碣曰 “佛塚”.28

3.3. Summarizing the Historical Lineage of Wanfosi

3.4. Clues from the Historical Lineage

4. The Hoard’s Formation

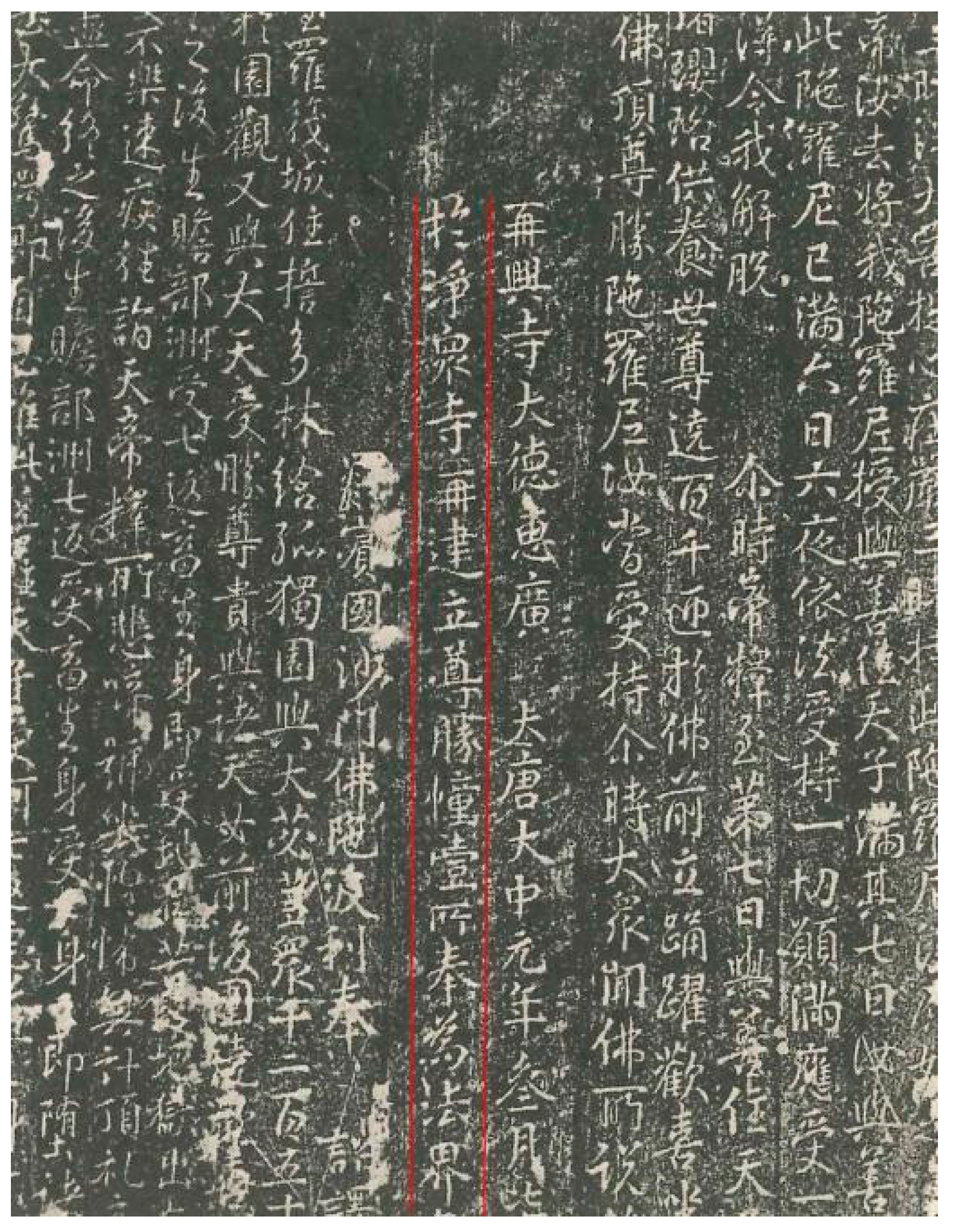

4.1. The Final Burial of the Hoard

Huiguang, the person of great virtue of Zaixingsi. On the guimao day, the seventh day of the third month in the inaugural year of the Dazhong Era of the great Tang, the person of great virtue, the Headquarters Adjutant (Hucker 1985, p. 575, entry no. 7860) of the He Office of the Zhenjing Army,32 Probationary Chief Musician of the Court of Imperial Sacrifices (Hucker 1985, pp. 239, 431, 476, entry nos. 2477, 5204, 6145), Lord Yang Geng, spouse Lady Zhao, son Hongdu. Hongdu, at Jingzhongsi, built and erected one banner of the honored victor, for... of the dharma realm...

At first, in the abolishment of the teaching (of Buddhism), Chengdu preserved only one monastery, the Dacisi (Monastery of the Great Mercy). Jingzhongsi was discarded and destroyed without exception. The enormous bell of the monastery was thus moved into Dacisi. It was until the revival of the doctrine by Emperor Xuanzong, the bell was then returned to Jingzhong(si).

先是武宗廢教, 成都止留大慈一寺, 淨眾例從除毀. 其寺巨鐘乃移入大慈矣. 洎乎宣宗中興釋氏, 其鐘却還淨眾.37

Fan Qiong... Along with Chen Hao and Peng Jian, who lived in the same era and (had) the same expertise, temporarily lodged in the city of Shu... During the Huichang years, after the destruction, only one monastery, the Da Shengcisi, preserved the Buddhist images. It was until the renovation of Buddhist monasteries by Emperor Xuanzong, the three individuals, at Shengshousi, Shengxingsi, Jingzhongsi, Zhongxingsi, from the Dazhong Era to the Qianfu Era, (having their) brush-pen never temporarily eased, pictured and painted more than two hundred jian of walls.

范瓊者... 與陳皓, 彭堅同時同藝, 寓居蜀城... 會昌年除毀後餘大聖慈一寺佛像得存. 洎宣宗皇帝再興佛寺, 三人於聖壽寺, 聖興寺, 淨眾寺, 中興寺, 自大中至乾符, 筆無暫釋, 圖畫二百餘間墻壁...38

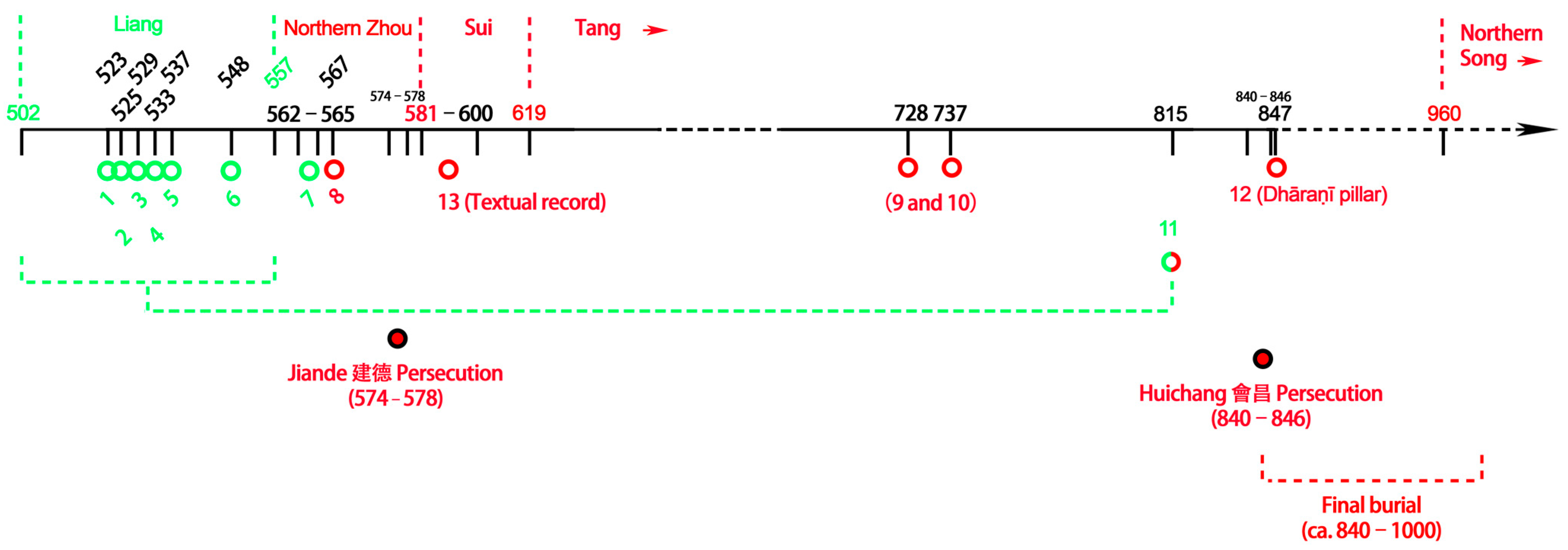

4.2. Brief Chronology of the Hoard

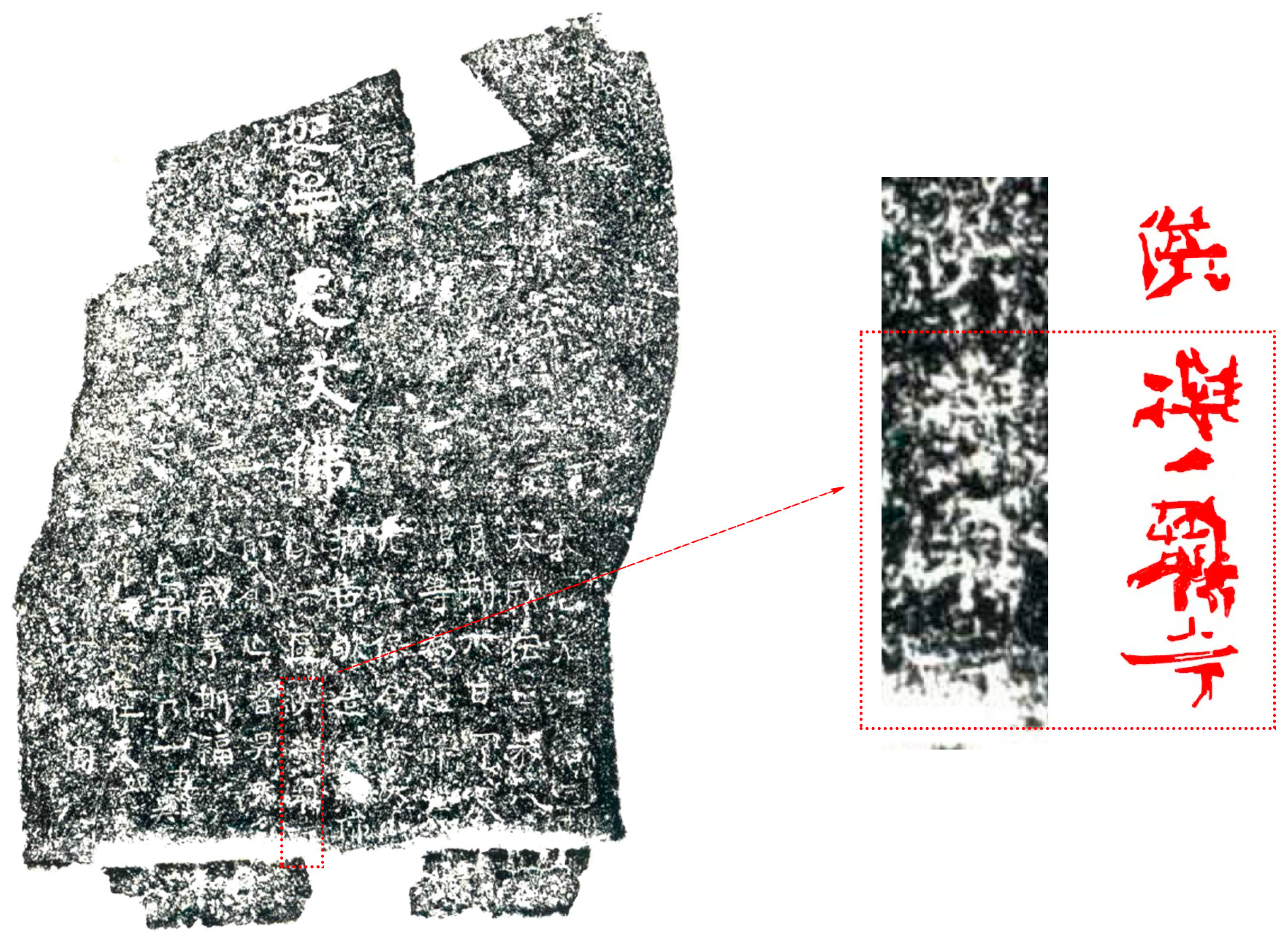

4.3. A Re-Used Image Living through Liang and Tang

On the sixth day of the eighth month, in a yiwei year, the tenth year of the Yuanhe Era of the Great Tang (815)... Assembly of... on purpose that... deceased... deceased... save... The entire family, the old and young, Qingji respectfully made one body of image of Buddha Śākyamuni, making offerings in front of [Jingzhongsi]. May the deceased ascend to the heavenly realm(s), and the entire family enjoy such a blessing... (Buddhist) Society Member... is one... in the heavenly realm... wife... Zhou.

大唐元和[拾]年/太歲在乙未八/月朔六日[ ]眾/[ ]等為[亡][ ][ ]/[ ][亡]保合[家]大小/[清]吉敬造[釋][ ]佛/像一[區]供[淨][眾][寺]/前願[亡]者昇天合/家咸[享]斯福/[ ]邑子[ ]乃[一]....../......[在]天[媳][ ]/......周.(ibid., p. 98)

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Wang Yirong, Tianrangge zaji, Congshu jicheng chubian 叢書集成初編 vol. 1561 (Shanghai: Shangwu Yinshuguan 商務印書館, 1937), 6. |

| 2 | The book was prefaced in the yiyou 乙酉 year of the Guangxu Era (1885). Wang Yirong, TRGZJ, preface, 1. |

| 3 | Two articles, albeit their contents overlap with each other, have also supplemented some missing information for each other (Dong and He 2014; He and Dong 2014). |

| 4 | In the earliest catalogue CWSY, it is stated that “after 1954, there are also sporadic finds (shiyou chutu 時有出土)”. Additionally, a dhāraṇī pillar of Tang is recorded to have been excavated in 1951 (Liu and Liu 1958, pp. 1, 3). Therefore, there may be more undocumented excavations other than the four recorded. |

| 5 | Wang Yirong, TRGZJ, 6. |

| 6 | “Wanfosi, located in the west of the town, the sixth Jia district, slightly more than one li, nearby Jinhuaqiao” (Wanfosi, xianxi liujia lixu Jinhuaqiao ce 萬佛寺, 縣西六甲里許金花橋側). Li Yuxuan 李玉宣 and Zhong Xingjian 衷興鑒 (both fl. ca. 1870s), Chongxiu Chengdu xianzhi (Chengdu: Bashu Shushe 巴蜀書社, 1992), 62. |

| 7 | Qingyuanmen was also called “the old West Gate” (lao ximen 老西門) by local residents. This is different with the “West Gate” (ximen), whose official name is Tonghuimen 通惠門, constructed in 1913 (Sichuansheng Wenshi Yanjiuguan 2006, p. 79). |

| 8 | Author unknown, “Sili Chuankang Nonggong Xueyuan gaiwei Guoli Chengdu Lixueyuan” 私立川康農工學院改為國立成都理學院, Jiaoyu tongxun yuekan 教育通訊月刊 (Author unknown 1946) 8: 22. |

| 9 | Yang Zhengbao 楊正苞 (Yang 2018), “Shuxue dajia Wei Shizhen yu Chengdu Lixueyuan” 數學大家魏時珍與成都理學院, Huaxi dushi bao 華西都市報 (1 April 2018), page A8. |

| 10 | As also cited above, the earliest catalogue indicates vaguely more excavations at the location (Liu and Liu 1958, pp. 1, 3). |

| 11 | See Note 5. |

| 12 | Zanning 贊寧 (920–1001), Song gaoseng zhuan, T50, no. 2061, 832b10–833a6. |

| 13 | Author unknown, Lidai fabao ji, T51, no. 2075, 184c17–18. |

| 14 | One of the three rubbings of an uninscribed image from the site reportedly dated 425 made by Wang Yiqi bears inscriptions that record the first excavation in 1882 (Guangcang Xuejiong 2015, p. 585). |

| 15 | Liu Damo 劉大謨 (jinshi 1508), Sichuan zongzhi vol. 3 (wood-block edition), 35a, digitalized by the National Library of China. http://read.nlc.cn/allSearch/searchDetail?searchType=10024&showType=1&indexName=data_892&fid=412000001011, accessed 9 April 2023. |

| 16 | Feng Ren 馮任 (1580–1642) composed and Zhang Shiyong 張世雍 (jinshi 1631) compiled Xinxiu Chengdu fuzhi, Zhongguo difangzhi jicheng, Sichuan fuxianzhi ji 中國地方志集成, 四川府縣志輯 ser. 1 (Chengdu: Bashu Shushe 巴蜀書社, 1992), 73. |

| 17 | Chengyun Hall (Hall of Receiving the Destiny) was the main hall of the residence of a Ming imperial prince. “Fucai” 副材, literally translated as “the duplicated materials”, is incomprehensible. I therefore suggest its phonetically related characters “fucai” 富財 (extra-money) in this context. This circumstance should be connected to certain revenue for the imperial prince’s personal use. |

| 18 | The original character is “ruo” 若. Zhang Zikai contends that “ruo” should be the misprint of “gu” 古 (Zhang 1999, p. 301). Since the following description mentions “at that time (the monastery) was still called Zhulinsi”. I have adopted Zhang’s correction. |

| 19 | Feng Ren and Zhang Shiyong, Xinxiu Chengdu fuzhi, 804–5. |

| 20 | Huang Tinggui 黃廷桂 (1691–1759), Sichuan tongzhi, Yingyin Wenyuangge siku quanshu 景印文淵閣四庫全書 (Taipei: Shangwu, 1982–1986) vol. 560, 553–54. |

| 21 | The character in this digitalized edition seems like “five” (wu 五), but I remain doubtful. Taking the Jiaqing edition of the Provincial gazetteer as reference, this character should be “enormous” (ju 巨). |

| 22 | Compiler unspecified, prefaced by Wang Taiyun 王泰雲 (fl. ca. 1810s) et al., Chengdu xianzhi (wood-block edition by Furong Shuyuan 芙蓉書院, collected and digitalized by Harvard Yenching Library) vol. 2, 2b. https://ctext.org/library.pl?if=en&res=89718, accessed 9 April 2023. |

| 23 | Chang Ming 常明 (fl. ca. 1810s), Sichuan tongzhi vol. 38 (Chengdu: Bashu, 1984), 1531. |

| 24 | Li Yuxuan and Zhong Xingjian, Chongxiu Chengdu xianzhi, 62. |

| 25 | For the Qing records of the Zhang’s massacres in Sichuan, Hu Zhaoxi’s 胡昭曦 article has summarized the resources (Hu 2018, pp. 77–84, esp. 78). However, Zhang’s massacres have been challenged by Chinese Marxist historians, especially for seeking endorsement for peasant revolts, that the later Qing records were just defamation and exaggeration (Sun 1979). |

| 26 | Peng Zunsi, Shubi (Shanghai: Shanghai Shudian 上海書店, 1982), preface, 1. |

| 27 | See Note 5. |

| 28 | Peng Zunsi, Shubi, 33. |

| 29 | Zhang Zikai does not agree with the gazetteer record, and contends that it was not until the period of the King Xian of Shu that the name “Jingyinsi” was used. Zhang’s view is based on several other types of literature that apply the name “Jingzhongsi” (instead of “Jingyinsi”) in the Song and Yuan periods. This issue is not crucially associated with my current topic, so I follow the gazetteers’ trend (Zhang 1999, p. 305). |

| 30 | Liu Xu 劉昫 (887–946), Jiu Tangshu 舊唐書 (Old Book of Tang) (Beijing: Zhonghua, 1975), 4707. |

| 31 | Falin, Bianzheng lun, T52, no. 2110, 509b4–10. |

| 32 | “Zhenjing Army” can be found in both Jiu Tangshu 舊唐書 and Xin Tangshu 新唐書, but the character is difficult to understand. It could be interpreted with the modern meaning of “with” or “and”, but it does not make sense in the sentence. Therefore, I read it along with the following character ya. |

| 33 | Although the catalogue CWSY transcribes the numeral characters in “lower cases”, here I keep the “capitalized” form as consistent with the original inscription. |

| 34 | The punctuation here adopts CWSY’s transcription. Zhang Zikai, however, argues a comma right after the character si. This theory turns “Zaixingsi”, the name of a monastery, into “zaixing si”, an action of renovating a monastery (Zhang 1999, p. 294). From my point of view, the original transcription by CWSY is more natural for a votive inscription. Additionally, Zhang overlooked the previous “Zaixingsi dade” as a noun, thus the two honorific titles should be consistent. |

| 35 | The transcribed character in CWSY is slightly different from the current geng, but both characters are not collected by the Kangxi zidian 康熙字典 (Liu and Liu 1958, p. 1). |

| 36 | The text in the rubbing provided by CWSY is incomplete. The transcribed text given in the same catalogue also lacks the beginning few characters and the final few ones of the votive inscription. Thus, the current transcription references both sources (Liu and Liu 1958, pp. 1–2). |

| 37 | Zanning, Song gaoseng zhuan, T50, no. 2061, 832c24–26, translated by the author. |

| 38 | Huang Xiufu 黃休復 (fl. ca. 1000), Yizhou minghua lu, Yingyin Wenyuange siku quanshu vol. 812, 482. |

| 39 | “The town of Chengdu lacked food; the abandoned children filled the roads… Each tong (of rice) was (charged) more than a hundred qian; the deaths of starvation were dispersedly seen”. (Chengdu chengzhong fashi, qier manlu… (mi) meitong baiyu qian, e fu langji 成都城中乏食, 棄兒滿路… (米)每筒百餘錢, 餓殍狼籍), Sima Guang 司馬光 (1019–1086), Zizhi tongjian 資治通鑒, Yingyin Wenyuange siku quanshu vol. 310, 59. |

| 40 | “There was a barbarian named Zhang Lezhong (fl. ca. 960s), frequently gather for attacking and robbing… (Cao) Guangshi (931–985)… thoroughly defeated the remaining robbers of Lizhou” (you yiren Zhang Lezhong zhe, chang qunxing gongjie… (Cao) Guangshi… jinping lizhou cankou 有夷人張樂忠者, 常群行攻刧… (曹)光實… 盡平黎州殘寇). Li Tao 李燾 (1115–1184), Xu Zizhi tongjian changbian 續資治通鑑長編, Yingyin Wenyuange Siku quanshu vol. 314, 140–41. It is estimated that the Song force had killed nearly one hundred thousand population of militaries and residents of Shu during the suppression (Su et al. 2011, p. 22). |

| 41 | Ibid., pp. 42–43. Note that this image, albeit inscribed with a Northern Zhou yearmark, should be a Liang product based on stylistic analysis. Since this is irrelevant to the critical discussion of this paper, I shall not unfold this issue. |

| 42 | “Thus, obtained three fragmental images with inscriptions… (among which) one is ‘Kaihuang…’” (nai jiande youzi canxiang san… yi Kaihuang… 乃揀得有字殘象三… 一開皇…). Wang Yirong, TRGZJ, 6. |

| 43 | The investigation of the Tang specimens can be seem in earlier scholarship, but the earliest report CWSZ and the earliest catalogue CWSY reported only three dated specimens, and Yuan Shuguang’s 袁曙光 survey did not cover as many Tang specimens as He and Dong’s paper in 2014 (Feng 1954, pp. 110–11; Liu and Liu 1958, p. 4; Yuan 2001, p. 38). |

| 44 | This dated specimen is recorded by Feng Hanji and Liu Zhiyuan, but the later scholarship by Yuan, He, and Dong, and the catalogue SCNSZ, did not disclose these two dated Tang pieces’ further information. |

| 45 | Same situation with the previous dated specimen (Feng 1954, pp. 110–11; Liu and Liu 1958, p. 4). |

| 46 | To my knowledge, no photograph has been published to date; only a rubbing of the partial inscription was disclosed (Liu and Liu 1958, p. 2). |

References

Traditional Works

Author unknown. Lidai fabao ji 歷代法寶記 (Record of the Dharma-Jewel through the Ages). T51, no. 2075.Chang, Ming 常明 (fl. ca. 1810s). Sichuan tongzhi 四川通志 (The Provincial Gazetteer of Sichuan). Chengdu: Bashu Shushe 巴蜀書社, 1984.Falin 法琳 (572–604). Bianzheng lun 辯正論 (Discerning the Correct). T51, no. 2110.Feng, Ren 馮任 (1580–1642) composed, Zhang, Shiyong 張世雍 (jinshi 進士 1631) compiled. Xinxiu Chengdu fuzhi 新修成都府志 (Revised Prefectural gazetteer of Chengdu), Zhongguo difangzhi jicheng, Sichuan fuxianzhi ji 中國地方志集成, 四川府縣志輯 ser. 1. Chengdu: Bashu Shushe, 1992.Huang, Tinggui 黃廷桂 (1691–1759). Sichuan tongzhi 四川通志 (The Provincial Gazetteer of Sichuan), Yingyin Wenyuangge siku quanshu 景印文淵閣四庫全書 vol. 560. Taipei: Shangwu, 1983–1986.Huang, Xiufu 黃休復 (fl. ca. 1000). Yizhou minghua lu 益州名畫錄 (A Critique on Famous Paintings of Yizhou), Yingyin Wenyuange siku quanshu vol. 812.Li, Tao 李燾 (1115–1184), Xu Zizhi tongjian changbian 續資治通鑑長編 [Extended Continuation to Zizhi tongjian (Comprehensive Mirror for Aid in Government)], Yingyin Wenyuangge siku quanshu vol. 314.Liu, Damo 劉大謨 (jinshi 1508). Sichuan zongzhi 四川總志 (Assembled Gazetteer of Sichuan, wood-block edition), digitalized by the National Library of China. http://read.nlc.cn/allSearch/searchDetail?searchType=10024&showType=1&indexName=data_892&fid=412000001011, accessed 3 July 2022.Liu, Xu 劉昫 (887–946), Jiu Tangshu 舊唐書 (Old Book of Tang). Beijing: Zhonghua, 1975.Li, Yuxuan 李玉宣 and Zhong, Xingjian 衷興鑒 (both fl. ca. 1870s). Chongxiu Chengdu xianzhi 重修成都縣志 (Revised Prefectural Gazetteer of Chengdu). Chengdu: Bashu Shushe 巴蜀書社, 1992.Peng, Zunsi 彭遵泗 (jinshi 1737). Shubi 蜀碧 (Elegy of Shu). Shanghai: Shanghai Shudian, 1982.Sima, Guang 司馬光 (1019–1086). Zizhi tongjian 資治通鑒 (Comprehensive Mirror for Aid in Government), Yingyin Wenyuange siku quanshu vol. 310.Wang, Taiyun 王泰雲 (fl. ca. 1810s) et al. prefaced. Chengdu xianzhi 成都縣志 (Prefectural Gazetteer of Chengdu. Wood-block edition by Furong Shuyuan 芙蓉書院, collected and digitalized by Harvard Yenching Library). https://ctext.org/library.pl?if=en&res=89718, accessed 3 July 2022.Wang, Yirong 王懿榮 (1845–1900). Tianrangge zaji 天壤閣雜記 (Miscellaneous Reports on the Heaven and Earth Pavilion), Congshu jicheng chubian 叢書集成初編 vol. 1561. Shanghai: Shangwu Yinshuguan 商務印書館, 1937.Ye, Changchi 葉昌熾 (1849–1917). Yushi 語石 (On stones). Shanghai: Shanghai Shudian 上海書店, 1986.Zanning 贊寧 (920–1001). Song gaoseng zhuan 宋高僧傳 (Song Biographies of Eminent Monks). T50, no. 2061.Modern Works

- Author unknown. 1946. “Sili Chuankang Nonggong Xueyuan gaiwei Guoli Chengdu Lixueyuan” 私立川康農工學院改為國立成都理學院 (“Private Chuan Kang Agricultural and Industrial College renamed as National Chengdu University of Science and Technology”). Jiaoyu tongxun yuekan 教育通訊月刊 8: 22. [Google Scholar]

- Canmou Benbu Sichuan Ludi Celiangju 參謀本部四川陸地測量局. 2012. Minguo ershier nian (1933) Chengdu jieshi tu 民國二十二年 (1933) 成都街市圖 (Map of the Streets and City Plan of Chengdu in the 22nd year of the Republic of China). Canmou Benbu Sichuan Ludi Celiangju 參謀本部四川陸地測量局 made, Zhu Meng 朱萌 composed. Beijing: Zhongguo Ditu Chubanshe 中國地圖出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Chengdu Wenwu Kaogu Yanjiuyuan 成都文物考古研究院. 2018. Chengdu Tongjin Lu Tang Jingzhongsi yuanlin yizhi 成都通錦路唐淨眾寺園林遺址 (The Tang Jingzhong Monastery Garden Site on Tongjin Road in Chengdu). Beijing: Kexue Chubanshe 科學出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Chengdushi Wenwu Kaogu Gongzuodui 成都市文物考古工作隊, and Chengdushi Wenwu Kaogu Yanjiusuo 成都市文物考古研究所. 1998. “Chengdushi Xi’anlu Nanchao shike zaoxiang qingli jianbao” 成都市西安路南朝石刻造像清理簡報 (“Preliminary Report on the Southern Dynasty Stone Images excavated from the Xi’an Road of Chengdu”). Wenwu 11: 4–20, 97–100. [Google Scholar]

- Chengdushi Wenwu Kaogu Yanjiuyuan. 2017. Chengdu Xia Tongren Lu: Fojiao zaoxiang keng ji chengshi shenghuo yizhi fajue baogao 成都下同仁路: 佛教造像坑及城市生活遺址發掘報告 (Xiatongren Road Site in Chengdu: The Excavation Report of Buddhist Statue Pits and Urban Life Remains). Beijing: Wenwu. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Huafeng 董華鋒, and Xianhong He 何先紅. 2014. “Chengdu Wanfosi Nanchao fojiao zaoxiang chutu ji liuchuan zhuangkuang shulun” 成都萬佛寺南朝佛教造像出土及流傳狀況述論 (“A Discussion on the Excavation and Transmission of Southern Dynasty Buddhist Statues in Wanfosi, Chengdu”). Sichuan wenwu 四川文物 2: 76–80. [Google Scholar]

- Fei, Yong 費泳. 2018. “Nanjing Deji Guangchang chutu Nanchao jintong fo zaoxiang de xin faxian” 南京德基廣場出土南朝金銅佛造像的新發現 (“New Discoveries of Southern Dynasty Golden Bronze Buddha Statues Excavated from the Deji Plaza in Nanjing”). Yishu tansuo 藝術探索 1: 52–71. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Hanji 馮漢驥. 1954. “Chengdu Wanfosi shike zaoxiang” 成都萬佛寺石刻造像 (Stone Carvings and Images of Wanfosi, Chengdu). Wenwu cankao ziliao 文物參考資料 9: 110–20. [Google Scholar]

- Guangcang Xuejiong 廣倉學宭. 2015. Yishu Congbian 藝術叢編 (Collected Works on Fine Arts). Shanghai: Shanghai Shudian, vol. 5. [Google Scholar]

- He, Xianhong, and Huafeng Dong. 2014. “Chengdu Wanfosi shike zaoxiang de yuanliu”, 成都萬佛寺石刻造像的源流 (“The Origin and Development of Stone Carving Statues in Wanfosi, Chengdu”). Shoucangjia 收藏家 12: 63–66. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Zhaoyi 胡昭曦. 2018. “Zhang Xianzhong yu Sichuan shiji jianxi” 張獻忠與四川史籍鑒析 (“An Analysis of Zhang Xianzhong in Sichuan’s Historical Records”). Diyu wenhua yanjiu 地域文化研究 1: 77–84. [Google Scholar]

- Hucker, Charles O. 1985. A Dictionary of Official Titles in Imperial China. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, Yuhua 雷玉華. 2009. “Chengdu diqu Nanchao fojiao zaoxiang yanjiu” 成都地區南朝佛教造像研究 (“Research on Southern Dynasty Buddhist Statues in the Chengdu Region”). In Chengdu kaogu yanjiu (xiabian) 成都考古研究(下編). Edited by Chengdu Wenwu Kaogu Yanjiusuo 成都文物考古研究所. Beijing: Science Press, pp. 621–48. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, Yuhua. 2018. “Chengdu Nanbeichao fojiao zaoxiang zai guancha” 成都南北朝佛教造像再觀察 (“Re-observation of Buddhist Statues in Chengdu during the Southern and Northern Dynasties”). Nanfang minzu kaogu 南方民族考古 16: 121–54. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Jingjie 李靜傑. 2010. “Sichuan Nanchao fudiao fozhuan tuxiang kaocha” 四川南朝浮雕佛傳圖像考察 (“A Study on the Images of Buddhist Stories in Southern Dynasties Relief Sculptures in Sichuan”). In Shikusi yanjiu 石窟寺研究. Edited by Zhongguo Guyizhi Baohu Xiehui Shiku Zhuanye Weiyuanhui 中國古遺址保護協會石窟專業委員會 and Longmen Shiku Yanjiuyuan 龍門石窟研究院. Beijing: Wenwu, vol. 1, pp. 100–18. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Yuqun 李裕群. 2000. “Shilun Chengdu diqu chutu de Nanchao fojiao shizaoxiang” 試論成都地區出土的南朝佛教石造像 (“A Study on the Southern Dynasty Stone Buddhist Statues Excavated in Chengdu Region”). Wenwu 2: 64–76. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Zhiyuan 劉志遠, and Tingbi Liu 劉廷壁. 1958. Chengdu Wanfosi shike yishu 成都萬佛寺石刻藝術 (Art of the Stone Carvings of Wanfosi, Chengdu). Beijing: Zhongguo Gudian Yishu Chubanshe 中國古典藝術出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Fuyi 羅福頤. 1955. “Hebei Quyang Xian chutu shixiang qingli gongzuo jianbao” 河北曲陽縣出土石像清理工作簡報 [“Preliminary Report on Stone Images Excavated in Quyang County (Hebei)”]. Kaogu tongxun 考古通訊 3: 37–38. [Google Scholar]

- Nagahiro, Toshio 長広敏雄. 1969. Rikuchō jidai bijutsu no kenkyū 六朝時代美術の研究 (Representational Art of the Six Dynasties Period). Tōkyō: Bijutsu Shuppansha 美術出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Shandongsheng Qingzhoushi Bowuguan 山東省青州市博物館. 1998. “Qingzhou Longxingsi fojiao zaoxiang jiaocang qingli jianbao” 青州龍興寺佛教造像窖藏清理簡報 (“Preliminary Report on Buddhist Statues Excavated from the Underground Chamber of Longxing Monastery in Qingzhou”). Wenwu 2: 4–15. [Google Scholar]

- Sichuan Bowuyuan 四川博物院, Chengdu Wenwu Kaogu Yanjiusuo 成都文物考古研究所, and Sichuan Daxue Bowuguan 四川大學博物館. 2013. Sichuan chutu Nanchao fojiao zaoxiang 四川出土南朝佛教造像 (Buddhist Statues of the Southern Dynasties Excavated in Sichuan). Beijing: Zhonghua. [Google Scholar]

- Sichuansheng Wenshi Yanjiuguan 四川省文史研究館. 2006. Chengdu chengfang guji kao 成都城坊古跡考 (A Study on Neighbourhoods and Historical Monuments of Chengdu). Chengdu: Chengdu Shidai Chubanshe 成都時代出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Soper, Alexander C. 1960. South Chinese Influence on the Buddhist Art of the Six Dynasties Period. Bulletin of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities, Stockholm 32: 47–107. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Pinxiao 粟品孝, Yu Duan 段渝, Kaiyu Luo 羅開玉, Yuanlu Xie 謝元魯, Shisong Chen 陳世松, Yingfa Li 李映發, Lihong Zhang 張莉紅, Xuejun Zhang 張學君, and Yimin He 何一民. 2011. Chengdu tongshi 成都通史 (The Comprehensive History of Chengdu). Chengdu: Sichuan Renmin Chubanshe 四川人民出版社, vol. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Zuomin 孫祚民. 1979. “Zhang Xianzhong ‘tushu’ kaobian” 張獻忠“屠蜀”考辨 (“A Study on Zhang Xianzhong’s ‘Massacre of Sichuan’”). Shehui kexue yanjiu 社會科學研究 4: 108–13. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, Dorothy C. 1998. Four Sichuan Buddhist Steles and the Beginnings of Pure Land Imagery in China. Archives of Asian Art 51: 56–79. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Hong 楊泓. 1964. “Nanchao de fo benxing gushi diaoke” 南朝的佛本行故事雕刻 (“The Carving of Buddhist Jataka Tales in the Southern Dynasty”). Xiandai foxue 現代佛學 6: 31–33. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Zhengbao 楊正苞. 2018. “Shuxue dajia Wei Shizhen yu Chengdu Lixueyuan” 數學大家魏時珍與成都理學院 (“Mathematician Wei Shizhen and Chengdu University of Science and Technolog”). Huaxi dushi bao 華西都市報, April 1, A8. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Changchi, and Changsi Ke 柯昌泗. 1994. Yushi, Yushi yitong ping 語石, 語石異同評 (On Stones, and Comments on the Differences and Similarities on “On stones”). Beijing: Zhonghua. [Google Scholar]

- Yecheng Kaogu Dui 鄴城考古隊. 2013. “Hebei Yecheng yizhi Zhaopengcheng Beichao fosi yu Beiwuzhuang fojiao zaoxiang maicang keng” 河北鄴城遺址趙彭城北朝佛寺與北吳莊佛教造像埋藏坑 [“The Burial Pit of Buddhist Statues in the Northern Wei Dynasty Monastery in Zhao Pengcheng, Yecheng Site and the Buddhist Statues in Beiwuzhuang (Hebei)”]. kaogu 7: 49–68. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura, Rei 吉村怜. 1985. “Nanchō no Hokekyō Fumonhin henshō: Ron Ryū Sō Genka ni nen mei sekkoku ga zō no naiyō” 南朝の法華経普門品変相: 論劉宋元嘉二年銘石刻画象の内容 (“Paintings of the Fumon Chapter of Sūtra Hokekyō in the Sothern Dynasty—On the Details of a Stone Engravings of Buddhist Story Dated the Second Year of Yuanchia”). Bukkyō geijutsu 仏教芸術 162: 11–27. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Shuguan 袁曙光. 2001. “Sichuansheng Bowuguan cang Wanfosi shike zaoxiang zhengli jianbao” 四川省博物館藏萬佛寺石刻造像整理簡報 (“A Brief Report on the Sorting of Stone Carving Statues from Wanfosi in Sichuan Provincial Museum”). Wenwu 10: 19–38. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Tingdong 袁庭棟. 2017. Chengdu jiexiang zhi 成都街巷志 (Streets and Alleys in Chengdu). Chengdu: Sichuan Wenyi Chubanshe 四川文藝出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Xiaoma 張肖馬, and Yuhua Lei. 2001. “Chengdushi Shangyejie Nanchao shike zaoxiang” 成都市商業街南朝石刻造像 (“Stone Images of the Southern Dynasties from Shangte Street in Chengdu”). Wenwu 10: 4–18. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Zikai 張子開. 1999. “Tangdai Chengdufu Jingzhongsi lishi yange kao” 唐代成都府淨眾寺歷史沿革考 (“A Study on the Historical Development of Jingzhongsi in Chengdu Prefecture during the Tang Dynasty”). Xinguoxue 新國學 1: 289–312. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Zong 張總. 2004. “Emei ji Shudi zaoxiang fohua zhongzhong” 峨眉及蜀地造像佛畫種種 (“Various Buddhist Statues and Paintings in Emei and Sichuan”). In Emeishan yu Bashu fojiao: Emeishan yu Bashu fojiao wenhua xueshu taolunhui lunwenji 峨嵋山與巴蜀佛教•峨眉山與巴蜀佛教文化學術討論會論文集. Edited by Yong Shou 永壽. Beijing: Zongjiao Wenhua Chubanshe宗教文化出版社, pp. 244–54. [Google Scholar]

| No. | Dating | Dynasty | Brief Description | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 523 | Liang | Śākyamuni image made by Kang Sheng 康勝 | Group-configured |

| 2 | 525 | Liang | Śākyamuni image (devotee’s name unrecognizable) | Group-configured |

| 3 | 529 | Liang | Śākyamuni image made by old lady Jimo 籍莫 | Standing Buddha |

| 4 | 533 | Liang | Śākyamuni image made by Shangguan Faguang 上官法光 | Group-configured |

| 5 | 537 | Liang | Image made by Hou Lang 侯朗 | Standing Buddha |

| 6 | 548 | Liang | Avalokiteśvara image made by Monk Fa’ai 法愛 | Group-configured |

| 7 | 562–565 | Northern Zhou | Aśokan image made by Yuwen Zhao 宇文招 | Standing Buddha |

| 8 | 567 | Northern Zhou | (No other extant inscription except for the yearmark) | Seated bodhisattva |

| 9 | 728 | Tang | “Stone image” | Unknown |

| 10 | 737 | Tang | Bodhisattva image | Unknown |

| 11 | 815 | Tang | Śākyamuni image re-inscribed with a Tang inscription | Group-configured |

| 12 | 847 | Tang | dhāraṇī pillar made by Huiguang and others | Dhāraṇī pillar |

| 13 | 581–600 | Sui | Textual record in TRGZJ | Unknown |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Z. Reconstructing the Archaeological Context of Free-Standing Buddhist Images: Considerations of the Wanfosi Hoard in Chengdu (Sichuan). Religions 2023, 14, 759. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14060759

Liu Z. Reconstructing the Archaeological Context of Free-Standing Buddhist Images: Considerations of the Wanfosi Hoard in Chengdu (Sichuan). Religions. 2023; 14(6):759. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14060759

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Zelan. 2023. "Reconstructing the Archaeological Context of Free-Standing Buddhist Images: Considerations of the Wanfosi Hoard in Chengdu (Sichuan)" Religions 14, no. 6: 759. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14060759

APA StyleLiu, Z. (2023). Reconstructing the Archaeological Context of Free-Standing Buddhist Images: Considerations of the Wanfosi Hoard in Chengdu (Sichuan). Religions, 14(6), 759. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14060759