1. Introduction

Secularization theory states that economic modernization may threaten the existence of religion. It is evident that modernization did bring a decline in religion in some regions. The improvement of China’s economy in recent years, however, has had the opposite effect: for example, a revival, rather than a dwindling, of the folk religion of the Tu.

Our fieldwork in Qinghai Province of Northwest China revealed that folk religion contributes to the internal order of ethnic communities and plays a role in the daily life of ethnic groups with distinct cultural traditions. Various researchers have argued that the folk religion of many ethnic groups focuses more on codes of social behavior than on cosmological or theological issues (

Draper and Baker 2011;

Wu 2019;

Zeng et al. 2020). Among the Tu and other ethnic groups, however, cosmology, in the form of clearly articulated spirit beliefs, continues to play a role.

The Tu ethnic group, also known as the Monguor, is an ethnic minority living in the northwest region of China. The Tu population is estimated to be around 250,000. Animism is a fundamental aspect of the Tu people’s ontology, shaping their understanding of the world around them and their relationships with other beings. In the indigenous Tu belief system, there is a tripartite cosmological classification that separates heaven, earth, and humans. In this light, the cosmological paradigm of the Tu posits that spirits, humans, and things co-construct and share the whole world. In their view of the world of daily life, the Tu perceive a symbiosis of different elements. The Tu religious pantheon consists of numerous anthropomorphic spirits and the ritual practices directed to these spirits play a role in the construction of social order. The folk religion of the Tu thus functions to maintain and stabilize the social order of this ethnic community.

In this article, we have selected the Tu ethnic group of Qinghai as the research population. We discuss how folk religion shapes the community’s overall world view and the role that folk religion plays in the construction of social order. Our analytic paradigm is informed by concepts of animist ontology. Animist ontology “conceptualizes a continuity between humans and nonhumans” (

Descola 1994), an apt representation of the landscape of the Tu ethnic group. Humans are believed to share a common culture with animals, plants, and other nonhuman entities. Differences among various living beings or natural objects are viewed as products of their individual characteristics.

This paper is divided as follows. First, we analyze the belief system and ritual practices of the folk religion of the Tu, with particular focus on communal dimensions. The next section delineates the role of folk religion in the construction of social order. In the conclusion, we discuss these findings as they apply to the Tu folk religion.

1.1. Literature on Chinese Folk Religion

Daoism, Buddhism, Islam, Catholicism, and Protestantism are the five religions officially recognized by the government of the People’s Republic of China (hereinafter PRC). The PRC, however, does not forbid the folk religious spirit beliefs and ritual practices found in villages. Should they not also be classified as “religions”? There has been scholarly disagreement on this issue. For some sinologists and historians, “Chinese folk religion” may be a valid taxonomic concept (

De Groot 1854;

Daniel 1976). In this sense, folk religion refers to as popular “unofficial” forms of Daoism and Buddhism with their own local textual traditions.

Yang (

1991) divides Chinese religion into two categories: institutional and diffused. Diffused religion, that is, folk religion, is embedded deeply into secular social institutions. In this regard, folk religion has been described as the religion of non-elite groups (

Teiser 1995).

Wang (

1996) argues that folk religion was only a minor part of Chinese culture, not representative of major elements in Chinese culture. Folk religion is not only different from the religious systems of the officials and scholar-officials, but also cannot be confused with institutionalized Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism.

Fenchtwang (

2001) analyzed how folk religion functioned to create bonds among individuals, having an influence on the organizational elements of Chinese society.

As previous studies have pointed out, believers in various Chinese folk religions outnumber the population of believers of Judaism, which is considered to be a major world religion. In this regard, folk religion can arguably be included in the comparative study of world religions (

Sharot 2002). One author argues that folk belief can be seen as “quasi-religion” (

Qiu 2016). Folk religion is embedded in the internal order of local communities and is diffused in daily life, forming part of a community’s way of life. Another author views folk religions as creative syntheses constructed by ordinary people to meet their psychological needs (

Ho 2005).

Broadly speaking, a great deal of scholarly attention has been paid to the rituals and social functions of Chinese folk religion. The landscape of Chinese folk religion has been described from different angles. Some scholars have carried out research on the intricate relationship between folk religion, national belief, and national ideology.

Sangren (

1987) illustrates how religion works as a major vehicle for maintaining social order.

Siu (

1989) offers a convincing explanation on how folk religion can be transformed into an element of folk culture that facilitates governmental reform efforts. In that light,

Li (

2015) examines how Nuo—one of popular religions in southeast China—has survived under the initiative of state-sponsored socioeconomic policies. Other researchers have focused almost exclusively on the personal, cultural, and socio-political aspects of religion.

Adam Yuet Chau (

2005) focuses on the way religious practices have been embedded into social life and the way popular religion plays a role in the social life of populations in contemporary China.

Goossaert and Palmer (

2011) utilize the concept of “social ecology” to analyze the changes that have occurred in Chinese religious life in the wake of modernization.

In recent years, religion in China has been accepted as a possible vehicle for promoting socialism with Chinese characteristics. Folk religion has a huge living space in contemporary society (

Lin 2007;

He 2010).

Gao (

2015) takes villages in Zhejiang, Fujian, Jiangxi Province as examples to analyze how folk religions continue to promote the integration of society during periods of secularization. Folk religious customs play an important role in stimulating the vitality of traditional villages and in promoting the modernization of farming (

Zhang 2019). Folk religion, in short, has practical implications in the process of modernization. However, most of the research on Chinese folk religion cited above has been carried out among the Han, particularly those in southern China. Relatively fewer studies deal with folk religion among ethnic minorities in the northwest, the region in which we conducted research. Furthermore, there has been little research on the role that folk religion plays in nation-building and in modernization.

Overmyer (

2005) posits that Chinese folk religion is distinguished by its absence of structured organization, its plethora of deities and spirits, and its diverse array of rituals such as offerings, divination, possession, and exorcism. Nevertheless, our research has uncovered that the folk belief system of the Tu ethnic group in Northwest China not only encompasses a multitude of deities and elaborate ritual practices, but also incorporates an associated religious organization. In our case, folk religions can, without a doubt, be classified as religions. In this article, we emphasize the practical functions of folk religion, viewing it as an embodiment of ritual beliefs and practices which reflect the local beliefs and practices of the people.

1.2. The Literature on Animist Ontology

Animist ontology is a belief system that ascribes spiritual or supernatural qualities to objects or phenomena in the natural world (

Harvey 2006). According to

Harvey (

2006), animist ontology is based on the belief that “everything in the world is alive and has a soul”. This belief system is often associated with indigenous peoples and traditional cultures around the world.

Here, we define “ontology” as a complex of principles through which people conceptually organize the human and nonhuman elements in their environment (

Pedersen and Rane 2001). Categorical distinctions between persons and objects and between nature and society are the cornerstones of the ontology underlying Cartesian science. Modernity, in a sense, emerged from this objectifying stance, including the underpinning of the Western notions of “multiculturalism” and “uni-naturalism”.

Are humans truly the subject and animals the object? Animism presents the antithesis of Cartesian objectivism (

Hornborg 2006). Animism is “an ontology which postulates the social character of relations between humans and nonhumans: the space between nature and society is itself social” (

de Castro 1998). However, Cartesian dualism and animism are both based on multiculturalism, which emphasizes the cultural distinction between humans and nonhumans. Nonhumans can be seen as active entities with agency, intentionality and subjectivity (

Shumon and Harald 2015). According to

Qu (

2019), animist ontology is a holistic worldview that emphasizes the interconnectivity and interdependence of all things.

An increasing body of ethnographic data demonstrates social continuity between nature and culture (

Descola 1994;

Ingold 2000;

Fausto 2007;

Ogden et al. 2013). Philippe Descola and Viveiros de Castro’s discussion of Amerindian cosmologies illustrates this point about animist ontology. Ethnological studies carried out by

Descola (

1994) present a new ontology; they posit naturalism as the fourth mode of understanding the changing world, the other three modes being animism, totemism and analogism. Descola paints a picture of ontological pluralism (

Ingold 2016) and a framework for carrying out comparative analysis. Castro coined the term “perspectivism” as a reference to ontologies that explore the subjectivity of humans and nonhumans. Perspectivism is founded upon the concept of “spiritual unity and corporal diversity” and on the principle that “the point of view creates the subject” (

de Castro 1998). This constitutes a new way of rethinking the relationship between humans and nonhumans.

From the abovementioned, we can clearly see that the perspective of animism presents an alternative way of thinking about the relationship between humans and nonhumans. Within the theoretical context of animism, an ontological turn occurs in the way the world of being is presented. Among the Tu ethnic group, we found a tripartite cosmology consisting of heaven (the spirit world), earth (the natural world) and the human world. We found a linkage between folk religion and social practice. The social order consists of anthropomorphic spirits, other living entities, and human beings. In this light, we have selected animist ontology as the theoretical perspective within which we analyze the religious practices of the Tu.

1.3. The Literature on Tu Folk Religion

In the mid-twentieth century, the religious traditions of the Tu were mentioned by

Schram (

1957). Subsequent studies of the Tu religion fall into two distinct categories. Some studies focus on individual religious currents among the Tu, such as their involvement in Tibetan Buddhism (

Tang 1996;

Zhai 2001), shamanism (

Lv 1985;

E 2009;

Xing and Murray 2018), folk religion (

Wen 2008) and so on. Other studies document the interaction between the Tu religion and other religions, showing that religions interact and syncretize with each other (

E 2002;

A 2018;

Wang 2016). In this latter sense, religious systems can be analyzed as cultural systems that are dynamically linked to other systems. In these pages, we hope to point out that folk religion among the Tu contributes to the construction of social order.

However, scholars have seldom ventured beyond the structure and overall features of the Tu folk religion. Less attention has been paid to the interaction between the folk religion and the social environment in which it is practiced. Through questionnaires and several years of participant observation and interviewing, we found many ways in which the Tu folk religion is embedded in the communal life of the Tu. In addition, with respect to idea systems, Tu religious practices reflect a cosmology that guides the Tu in their conceptualization of human and nonhuman social life. In this light, this paper focuses on the relationship between folk religion, cosmology, and the social order of the Tu.

In order to provide a comprehensive analysis of the folk religion of the Tu, our research team undertook multiple fieldwork sessions in the Tu areas of Qinghai between 2016 and 2020. During these visits, we observed several significant festival ceremonies, including the Nadun (纳顿节), the Liuyuehui (六月会) and the Biangbianghui (梆梆会) Festivals, etc. Furthermore, we conducted extensive interviews with local religious professionals, elderly individuals, and government officials to gain a deeper understanding of the local religious beliefs and practices, and more than fifty cases were collected. Our research also involved the distribution of 120 questionnaires through a simple random sampling method, from which we retrieved 104 responses. In addition, we collected a vast amount of oral tradition material. The data collected from these fieldwork activities played an instrumental role in shaping our subsequent analysis. This study will in effect be a case study on the landscape of Tu folk religion that reflects animist ontology.

2. Folk Religion and Animist Ontology of the Tu

As one of the ethnic minorities in northwest China, the Tu live principally in a swath of contiguous regions that include Huzhu County, Datong County, and Minhe County, all of them in Qinghai Province. In addition, a small population of the Tu is distributed in Ledu County and Tongren County in Qinghai Province and Tianzhu County in Gansu Province. Qinghai has historically been a mixed ethnic area characterized by the interaction of distinct ethnic groups. This had led the population in this area to engage in mutual learning of different cultures. As a result, the religious system of the Tu is characterized by complexity in its spirit beliefs and rituals.

In general terms, the spirit world of the Tu is a tripartite combination of the spirits of Tibetan Buddhism, Daoism, and local village religion. The specifics vary by community. Forming an organic part of the Tu’s culture, folk religion is closely intertwined with the daily life of the Tu. At the same time, there are positive interactions with national authorities. As a result, folk religion has come to play an important role in maintaining the harmony and stability of the Tu community and in maintaining social order within the community.

During several years, we carried out standard anthropological procedures of participant observation and interviewing in the Tu community distributed in Qinghai Province. In addition to contact with local people, our observation and interviewing also included contact with religious specialists and government officials. In addition, we participated in various religious activities. Based on this fieldwork, here, we present a portrait of folk religion in typical Tu communities located in Minhe County and Huzhu County. We first focus on the “surface” features of the Tu religion, providing ethnographic descriptions of its major spirits and rituals. We then explore the cosmological issues and conceptual structure that underlie these surface practices and spirit beliefs.

2.1. Ethnography of the Tu Religious System

The folk religion of the Tu is characterized by internal diversity, in that the spirits and rituals differ from region to region. As can be seen in

Table 1, the spirit world of the Tu is a tripartite combination of spirits from Tibetan Buddhism, Daoism, and local village religion. These three different religions co-exist harmoniously. The folk religious component is most closely related to the natural ecology and to the interactions among different groups of living beings. Animism is defined as “the belief that natural objects, animate and inanimate, have souls or spirit” (

Bird-David 1999), and this belief system is central to the Tu people’s understanding of the world. The spirit world of the folk religion includes zoomorphic spirits linked to trees, theriomorphic spirits linked to animals, and local anthropomorphic spirits, both male and female. The Tu spirit world reflects local geographical features and local lifestyle patterns.

Each local community, however, has its own unique features.

Table 2 shows clearly that the spirit worlds of the two communities have different characteristics. The spirits in Huzhu County are more closely related to animals, such as the mule king and the goat deity. On the one hand, these theriomorphic spirits were inherited from the earlier nomadic culture. However, they also reflect the influence of Tibetan Buddhism. In contrast, the spirits found in the pantheon of Minhe County, such as the

erlangye and

wenchangye, are associated with farming culture and with Daoism. The specific spirits of the two communities are different, but these spirits are all related to the local ecology and community and are tutelary spirits protecting each community. The major functions of spirits in both communities are to manage rainfall, nourish crops, protect the safety of the village, and cure diseases.

These tables capture the essential syncretism of the Tu folk religion. In the Tu community, the pantheon maintains the original spirits but also incorporates religious elements from Daoism and Tibetan Buddhism. Some scholars point out that the more spirits the ethnic groups invoke, the more likely that interreligious conflicts will be reduced and harmonious interreligious relationships will emerge (

Zhang 2014). This is precisely what the folk religion of the Tu reflects—a pluralistic, syncretic spirit world.

2.2. Folk Religious Practice in the Tu Community

In the Tu community, folk religion is expressed in daily life and internalized as behavioral rules. The Tu people perceive every aspect of the natural environment as possessing a spiritual force, which is deemed vital to the world’s operation. This spiritual force is characterized as potent and unpredictable, and it is believed to materialize in various forms. In the context of their folk religion, the Tu have formed a series of festivals, temple fairs and rituals that are separate from the Tibetan Buddhism which many also practice. These activities embody and reflect the folk wisdom and creativity that inform the daily lives and spiritual world of the Tu. In the following part, we explore the animist ontology of the Tu ethnic group and the ways in which it shapes their cultural practices, cosmology, and worldview.

2.2.1. Folk Festival: Entertaining Villagers and Thanking Spirits

Through our fieldwork, we found that the animist ontology of the Tu people is closely related to their shamanic practices. Especially the bo (博, folk religious specialist) and the fala (shaman) are seen as the mediators between the human and spirit worlds.

Taking the Minhe Tu community as an example, nadun (纳顿, a regional festival) is a series of annual harvest celebrations. Beginning on July 12th of the lunar calendar, songjiazhuang (宋家庄) hosts the first round of nadun. The other villages in the region then take turns holding the festival. The last round of nadun is held by zhujiazhuang on September 15th of the lunar calendar. With its duration of two months, nadun may qualify as the longest carnival in the world. Local people sing, dance, and perform dramas to celebrate an abundant harvest and to relax from the exhaustion and strain of farming.

Nadun consists of two separate events: xiaohui (小会, the preparation phase that precedes the festival) and zhenghui (正会, the actual performance of the festival). Xiaohui is a ritual for venerating the deities, while zhenghui consists of huishouwu (会手舞 Huishou dance), mianjuwu (面具舞, mask dance), and tiaofala (跳法拉, shaman’s dance). It is worth mentioning that the most important deity venerated in the mianjuwu is Guan Yu (关羽, a Daoist deity). The mask of Guan Yu can only be worn by the paitou (牌头, religious leader), the person who is in charge of nadun for that particular year (the role rotates from year to year).

The donning of the mask is an important ritual act. The mask represents the local deity and transforms the human body into a spiritual body which conveys energy to the human wearing the mask. Those who perform the ritual of tiaofala enact the ritual dance and any other ritual activities that may be selected by the spirits. Fala involves a bodily transformation similar to that of mianjuwu to permit communication with deities. Since the largest number represented by a singular character is “nine”, the Tu abide by a rule of “three times three make nine” in the veneration of spirits during nadun. For that reason, the repertoire of different rituals includes three kinds of motions, and each motion should be performed three times.

An important element in the festival is that of “rewarding the help of the spirits”, particularly with regard to the agricultural cycle. The growing crops are vulnerable to the danger of excessive rain or of destructive hail. In order to protect the fields from natural disasters, villagers invoke the spirits to plead for favorable weather and an abundant harvest. Thus, nadun is an annually reoccurring festival of thanksgiving to the spirits for crop protection. Because different villages enact nadun sequentially in any given year, the festival promotes the interaction between different villages. nadun thus unites the entire Tu community and in addition connects the human population with the spirits. As such, the animist ontology and shamanic practices of the Tu may be regarded as a means of navigating their connection with the natural world.

2.2.2. Folk Ritual: Resolving Problems and Conflicts

In addition to nadun, other folk rituals of the Tu function to resolve conflicts in the community. The most important ritual is enacted to bring rain when the community is confronted with the danger of drought. As each village enshrines its own individual deity, the details of the rain-making ritual differ from place to place. Take wenjiacun in Minhe County as an example. If there is a severe spring drought, or if little rain falls after sowing, the villagers ask the fala (the folk religious shamanic specialist) to summon the spirits. At that time, in preparation for the ritual, the villagers begin collecting funds and purchasing the items (such as black bowls and other ritual paraphernalia) needed in the ceremony. Out of collective respect for the spirits, the villagers actively cooperate in the financing of such rituals. The rituals thus function not only to resolve intra-community conflicts, but also to maintain those informal structures of local governance that are distinct from the system of formal governmental authority.

During fieldwork, we came across many examples of spirits being embedded in the daily life of the Tu. One young man was surly, disrespectful to his parents, and addicted to gambling. His parents were helpless. When the villagers learned of this situation, they intervened and asked the image to invoke the authority of spirits to punish the young man for his misbehavior. The effect of this intervention was quite positive.

In addition, official governmental village cadres occasionally call on local folk religious specialists to intervene in matters of theft, quarrels over land, and other conflicts. In this way, village temples and folk religious associations are called upon to become involved in matters that are technically under governmental control. In this sense, folk religious specialists can be seen as intermediaries who function not only in local religious life, but also in local politics. Respected by the villagers because of their special powers over the spirit world, they can intervene to relieve tensions and conflicts between party cadres and the local population. Such cases illustrate a local adaption of homogeneous national laws to the local realities of ethnic minority villages.

In a similar vein,

Lv and Liu (

2017) point out that in some ethnic regions of northwest China, informal local folk religious patterns can influence the formal political structure of a village. In this ethnic minority world, governance relies on three pillars: religious power, clan authority, and official village committees. As illustrated above, certain villagers play the dual role of a religious specialist and a local power broker. Local religious leaders thus invoke their spiritual authority not only to act as mediators between ordinary people and the spirits in religious activities. They also function as local elites who can connect ordinary people with local government officials in public affairs.

In brief, a religious specialist can acquire insight into the spiritual forces that govern the world through ritual communication, which can be utilized to aid both individuals and the community.

2.2.3. Informal Village Association: Maintaining Religious Order and Space

In various Tu communities of northwest China, some village informal associations are closely related to the practice of religion. Qingmiaohui (青苗会 Qingmiao festival), nadunhui (纳顿会 Nadun festival) and manihui (嘛呢会 Mani Festival) are religious groups involved with spirits, village temples, and local family clans. Most ritual action occurs within and around village temples, which are considered to be sacred sites by the local population. Every village venerates its own cluster of spirits, which may differ from the spirits venerated in other villages. The spirits are housed in village temples. Every temple may thus have a unique configuration of statues and images.

Every village likewise has an association in charge of the local temple. Their mission is to organize and officiate religious activities and to maintain community order in accordance with the will of the local spirits. For example, at the time of the Tomb Sweeping Festival, the crops are maturing. The paitou go to the village temple to hold a pre-harvest ritual to call on the local spirits to ensure the fertility of the crops. In the following weeks, the village holds a regular series of rituals. In addition, the Tu of Minhe County have a special ritual, the manihui, during the summer harvest season. To request a bountiful harvest from the spirits, the head of the manihui organizes the elderly (especially elderly women) to recite Buddhist sutras in the village temple for 15 days (neither the temple nor the manihui ritual is Buddhist, but the Tu rituals incorporate elements from Tibetan Buddhism).

The heads of the village associations mentioned above are mostly respected elders in the village. Not only do they function in regular religious rituals, but they are also the elites of the village with high authority to enforce laws and maintain order. In the past, when political concerns moved the state to place limits on religious rituals, folk religious leaders adapted flexibly to the restrictions. Village religious leaders simply redefined village temples as centers of cultural heritage, labeling them as centers of “community service for the elderly”. Under this rubric of social welfare, folk religious sites began to receive—and continue to receive—financial support from the government.

Some arrangements that have emerged in ethnic areas achieve a compromise between national law and local realities. The heads of the village associations are elected by a rotation system. They can mobilize the community in the name of the village’s tutelary spirits (

Zhao and Zhong 2014). This informal organization in the Tu villages justifies its existence largely in terms of its role in securing protection from the spirits on matters of concern to the village, particularly those related to the agricultural cycle and to matters of internal harmony. However, though involved with rituals directed toward the spirit world, we can see that the folk religious system of the Tu villages also serves as a vehicle for maintaining the social unity of the village.

2.2.4. Agriculture and Ecology: Establishing Harmony with Nature

Scholars have suggested that animist ontology has implications for environmental ethics and conservation, and animist ontology “offers a unique and powerful philosophical basis for conservation” (

Dove and Kammen 2015). In Huzhu County, a 21-member village organization referred to as the

qingmiaohui enacts rituals during the fourth and fifth lunar months to protect the growing crops and to petition the spirits for a good harvest. Ritual activities led by the head of the

qingmiaohui are on the whole focused on and synchronized with the local agricultural cycle. The religious specialists are expected to determine auspicious days in advance and to so advise the villagers. On an appointed day, all the male villagers gather in the village temple at dawn and carry out an inspection of the fields. After that, the head of the

qingmiaohu informs the community of the rules and regulations to which local villagers must adhere to please the spirits and assure their cooperation. Mistreating livestock, cutting trees, and trampling on planted fields encumbers the growth of the crops. Those behaviors are therefore forbidden from the moment in which the

qingmiaohu ritual is terminated. These ritual rules and regulations are believed to ensure both ecological protection and village harmony. In addition to his ritual role associated with the agricultural cycle, the head of the

qingmiaohu also participates in the resolution of intra-community conflicts.

Animistic beliefs, which assume that all beings have spirits, are still prevalent among the Tu. There is a widespread belief that the spirits of human relate to the spirits of all other beings in the universe and that different beings can be transformed into each other. This concept creates among the Tu a connection of gratitude and reverence toward nature. They refrain from destroying the trees and grassland around temples. The qingmiaohui and other village associations also play a prominent role in protecting the natural environment for farming.

Furthermore, the Tu have rituals of fasting for round-hoofed animals such as donkeys and horses, etc. These practices play a positive ecological role in the dry and grassless regions common in northwest China. The practice of fasting donkeys and horses exerts a protective influence on these animals, as they are not amenable to large-scale farming in Tu area. This reduction in the herbivore population could lead to more effective preservation of scarce grassland and wild vegetation. From this perspective, we can see that the folk religion of the Tu has potentially positive environmental consequences.

In this light, we see that there is a harmonious linkage between the religious practices of the Tu and their local ecosystem. The ecological restraint promoted by the local belief system works to protect and conserve natural resources and promote the prosperous development of the local environment. This positive ecological function occurs when the local folk religion guides the environmental behavior of local people, alleviating the current deterioration of the natural environment, and promoting a harmonious relationship between humans and nature.

2.3. Cosmological Conception of the Tu Ethnic Group

The spirit beliefs and rituals of local folk religion are closely linked to the historical development of the Tu ethnic group. Throughout the centuries, the Tu minority has been heavily influenced in its historical development by the local Han majority and by the locally prominent Tibetan ethnic group. The cultures of Han, Tibet, and Tu have co-existed peacefully over the centuries. The ordinary Tu comfortably and simultaneously oscillate between three different religious systems. These three systems generate tripartite cosmological understandings and thought patterns with three components.

For this reason, in the communal life of the Tu, the number three enjoys great symbolic power in many contexts. Firstly, it represents the harmonious coexistence of the three ethnic groups consisting of Han, Tibet, and Tu, and the three corresponding religious traditions of Tibetan Buddhism, Daoism, and the Tu folk religion. Secondly, the number three also symbolizes heaven, earth, and human beings. Thirdly, the number three stands for health, wealth, and longevity. The special respect shown to the number three thus reflects the cultural traditions, living habits and social thoughts of the Tu. It exerts an identifiable impact on the material, spiritual and institutional culture of the region. This three-part cosmology of heaven, earth and human society affects how the Tu perceive the world. In their concept, the world is shared by spirits, humans, and other natural beings, both living and inanimate.

As is true of Daoism and Buddhism, the spirit world of the Tu is largely anthropomorphic in character. The spirits are conceived of as being quasi-human both in physical form and in their emotions. The niangniang (queen mothers) housed in the village temple are jealous of beautiful girls; like many humans, the niangniang do not like competition. Girls cannot be prettier than niangniang, and a woman may not remarry even if her husband dies. More often than not, villagers pray to the longwang (dragon kings) to manage rain in times of drought or flooding. Sometimes, the longwang cannot fulfill his duty with respect to the rain. At this time, the villagers place the longwang on the Shen Jiao (神轿, a wooden litter for housing spirits) and transfer the longwang to the Buddhist Shakyamuni Temple. The sedan chair is placed on the ground and the image of the longwang is made to kneel penitentially in front of the statue of the Buddha. The power of the Buddha is in effect being used to punish the local spirits who have not fulfilled their duties. In this religious tradition, humans are viewed as having enough power over the spirits to punish them for failing to perform their traditional climatological duties.

Inanimate things are also seen as having spiritual power. The tangka (a Buddhist painting) is originally a kind of traditional folk handicraft. However, when the tangka is used to represent the entire monastery, it is equivalent to Buddha and possesses spiritual power.

The Tu recognize that their own activities can have an unintended negative impact over the earth on which they live. The population may thus react with surprising equanimity to an earthquake or some other natural disaster. It is believed that the natural disasters may be a result of humans harming the body of the earth. In this sense, folk religion can play a role in reassuring people and in maintaining social order during catastrophic natural events such as earthquakes and floods.

Furthermore, humans who inhabit the material world and spirits who inhabit the invisible sacred world are viewed as being in a relationship of mutual symbiosis. This can be seen in the mantang (曼唐), a kind of medical wall chart that reflects the implicit theory underlying much of traditional Tibetan medicine (the mantang typically has the form of a tangka painting). It depicts the ailments that afflict the human body as deriving from parallel spiritual forces, from the avidya of raga, dvesha, and moha. In addition, the drawing of a dead body is viewed as a symbol of the moral character of the dead person during life. For example, the soul of an evildoer will be sent to pretagati. Furthermore, the Tu people have a variety of customs related to the number three that hold symbolic significance in their daily lives. Examples include consuming three portions during meals, reciting three sacred scriptures during funerary rites, and so on. The number three is regarded as a mystical and propitious symbol. In the Tu language, Gurangewu refers to the act of proposing three toasts of wine to welcome guests. This is also related to the powerful magical symbolism surrounding the number three. This belief is rooted in the Tu people’s perception of the interdependent relationship between the three entities of heaven, earth, and human beings. The trinity is considered to comprise a cohesive community in their daily lives.

Overall, the animist ontology of the Tu people and their shamanic practices are integral to their folk identity and play an important role in their relationship with the natural world.

3. Folk Religion and Social Order of the Tu

As with all religions, the folk religion of the Tu can be analyzed as a system with three components generally found in all religions: (1) an inventory of invisible spirits, (2) rituals to interact with the spirits, and (3) religious “specialists” who are recognized as having expertise in interacting with the spirits. In addition, as

Radcliffe-Brown (

1968) proposes, the study of a religious system should also deal with the social functions of the system, in particular with the role of religion in the formation and maintenance of social order. The components of a religious system (spirits, rituals, specialists) are logically and analytically distinct from the functions that the system performs. In our treatment of the Tu folk religion, we deal with the beliefs and rituals of the system. However, our interest is also in the social and communal functions which the religious system fulfills, particularly with respect to the maintenance of social order.

3.1. Folk Religion and Social Integration

With respect to the basic components of a religious system,

Durkheim (

2008) argued for the existence of two basic categories: beliefs and rituals. Belief concerns concepts and cognitive representation, while rituals involve behavior.

Turner (

1967) defines ritual as “prescribed formal behavior for occasions not given over to technological routine, having reference to beliefs in mystical beings and powers”. In the Tu community, the belief in spirits defines and inhibits deviant behavior by local people. The beliefs surrounding spirits not only recognize the authority of spirits, but also form an “ideology” to maintain the unity of the villagers. Some villagers believe that taboos against swearing and cursing in the presence of supernatural force create an informal control mechanism. People believe that spiritual forces would punish villagers who promote disunity or break promises. In this sense, the supervision of behavior by the spirits subjects everyone’s behavior to the conventions of the village.

An example can be provided. After its introduction into Minhe County, the Daoist deity

erlangshen has become a local folk deity worshiped by multi-ethnic villages. Subsequently, the

erlangshen spirit became a collective symbol with supernatural power that functioned to strengthen the local identity of the community members. The most important ritual entails the participation of

erlangshen in the earlier-discussed

nadun. At the beginning of the

nadun ritual,

erlangshen is brought out of the temple and carried by a group of men to the place where the ritual is to be performed. The ritual is performed by villagers to coincide with the local crop harvest. The fact that this harvest ritual is locally widespread is the result of long-term interaction among the villages. The coordination of the time and the place of the ritual in different villages serves to integrate the whole community. This integration is achieved by common beliefs and gives birth to a sense of inter-community integration. As a collective representation of the village, the local spirits create cohesion within the village. That is, the belief in

erlangshen creates unity among different ethnic groups and regions (

Wen 2007). In this respect, folk religion has shaped the integration of the Tu communities in Sanchuan for nearly a century.

Another example can be provided. The liuyuehui (六月会, June festival) in Tongren, a Tu community, promotes integration in the name of the spirits. The completion of a liuyuehui ceremony requires the joint efforts of the whole ethnic group. There is usually a leader, fala (法拉, a folk religious shaman), who coordinates and controls the ritual process. The fala achieves local respect; he is symbolically viewed as representing the will of the spirits. During the ceremony, people tacitly obey the requests of fala, fearing to disobey. We learned the following in an interview: “At least one family member must participate in liuyuehui. The village now stipulates that all men over the age of 16 must perform shenwu (神舞, a sorcery dance). If someone refuses to do so, they will be punished by fines of other measures” (field notes in 2017).

Moreover, the fala usually punishes local village troublemakers (such as local toughs and wrongdoers who gamble or promote sexual promiscuity). This occurs on the last day of liuyuehui, which corrects community values and strengthens social restraints. “During liuyuehui, the fala will single out people with bad behaviors in the village, then point out mistakes and give admonitions. In general, those criticized will accept the fala’s demands, because the fala is believed without doubt to represent the power and will of the spirits” (field notes in 2016).

In this regard, folk religion serves the function of community building. The folk religion does not invent or impose new ethical rules, but reinforces the existing ones (

Ho 2005). Traditional virtues are passed on by believers, enter into their minds, and express themselves in the form of behavior norms.

Moreover, folk beliefs provide spiritual legitimization to ethical norms, thus rendering them more durable and powerful. For example, when one interviewee was asked about the effect of religious belief on individuals, the answer was as follows: “There is a sense of constraint. Faith creates fear in my heart, which constrains my behavior. In the age when our country did not have external guides, we were born with inner guides. The good spirit on the right side of our body and the evil spirit on the left side of our body will record the things we have done. For example, although no one is around to see us when we commit an act of villainy, there are spirits, that is, guardians, who create reverence in the heart” (field notes in 2019).

The folk religion of the Tu is rich in rituals and manifests itself in the daily life of local people. The practice of rituals is a core component of the religious system, and the social integration which beliefs achieve is mainly expressed through rituals. The internal beliefs of the people are externalized into highly visible behaviors, which in turn legitimize social norms. The functions of social control and social integration are principally achieved in the following two ways. Firstly, the behavior of those who violate social norms is regulated and controlled, thus maintaining social order and stability. Secondly, rituals function to bring together social groups who subsequently maintain social order or even create new forms of social order. Ceremonies themselves are shaped by cultural norms, which in turn shape and produce social order. Therefore, annual collective religious activities such as the nadun and liuyuehui in the Tu community promote social integration and ensure orderly life among the villagers.

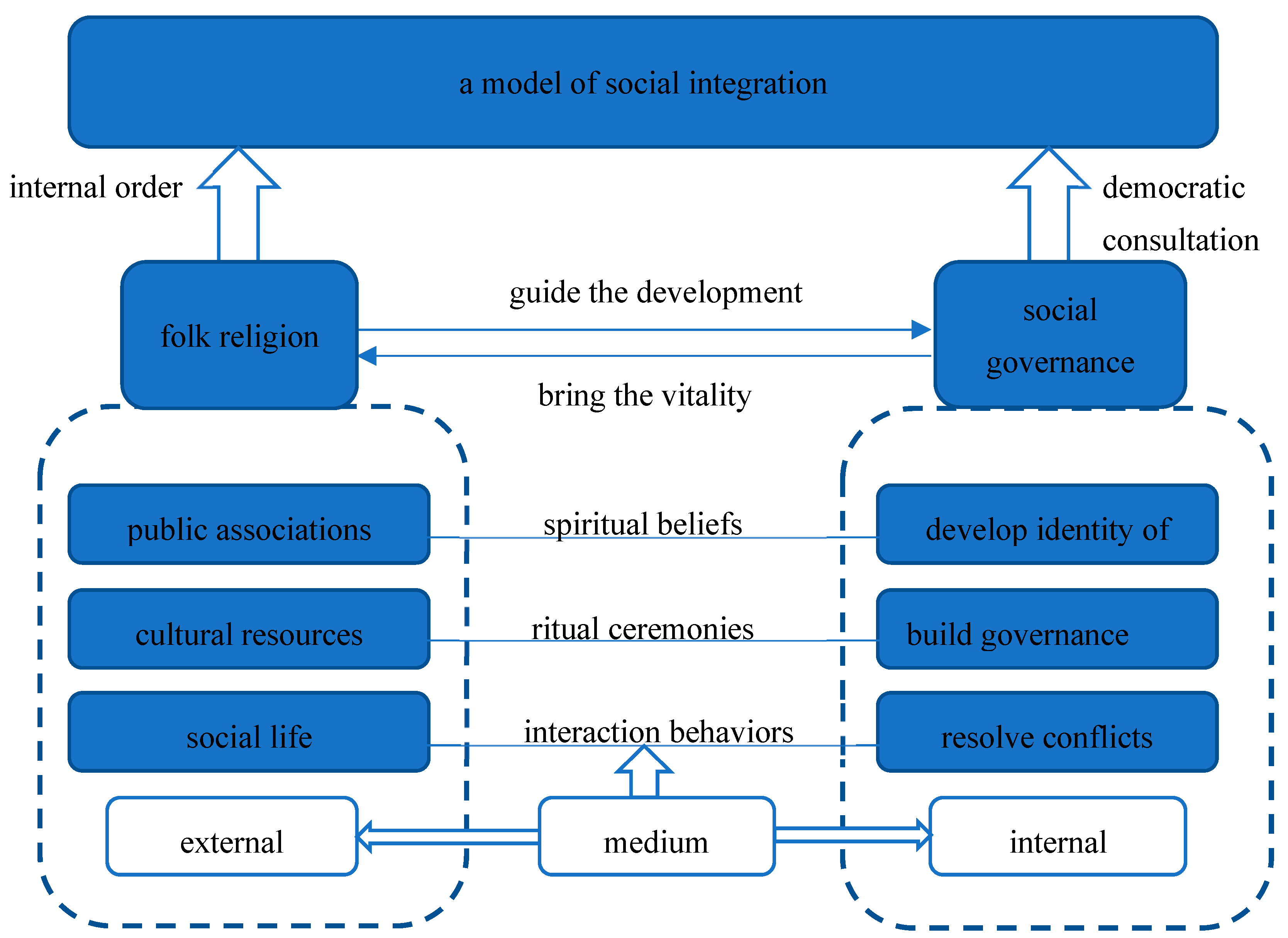

Based on the discussion above, we have documented that folk religion encourages conformity to established social codes, thereby contributing to good social governance and benefitting the population at large. Folk religion contributes to the fulfillment of social needs, the creation of public associations, and the mobilization of cultural resources. Those elements create a religious system whose spirit beliefs and spirit-directed rituals have an impact on the behaviors of the social system. This system pursues multiple functions: the integration of society, the resolution of social conflict, the construction of governance networks, and the development of ethnic identity (see

Figure 1 below).

3.2. Folk Religion and Ethnic Identity

The issue of the relationship between folk religion and ethnic identity warrants discussion. Ethnic identity is related to intangible factors such as religion, language, customs and others. Throughout human history, language, religion, and social rules have been the building blocks underlying social organization. Religious and linguistic bonds not only function as factors that connect members within an ethnic group here and now, but have also reflected a common cultural origin that transcends time and space.

According to Claire Mitchell, religious identity often plays a significant role in shaping an individual’s ethnic identity, and religious beliefs, symbols, and practices can help to establish a shared sense of history, culture, and community among members of a particular ethnic group. (

Mitchell 2006). For the Tu people, the traditional embroidery

Taiyanghua (太阳花, sunflower) is regarded as the totem and symbol of their ethnic group, symbolizing the symbiosis of their folk beliefs. The Tu people adorn their houses and clothing with

Taiyanghua, which serve as a distinctive marker of their ethnic identity. Individuals who wear clothes embroidered with sunflowers are immediately recognizable as the Tu.

In addition, we interviewed a master in carved wooden mandala. When we asked him whether we could learn to carve mandala, the master told us that “much of the culture in Tongren comes from Tibetan Buddhism. If you do not understand Buddhism, it is difficult to become an accomplished artist in woodcarving. You may become a skilled carpenter. But in order to deeply understand the meaning of artwork, a woodcarver must first be a faithful believer in Buddhism. The skills involved in painting, clay sculpture and woodcarving actually create a linkage between the individual and the Buddha. Carving wooden mandala is a process of spiritual practice that purifies the soul. Making a mandala is not done with the brain, but more with the heart” (field notes in 2018).

It is clear that this artist has a deep identification with his own religious beliefs. The distinction between “us” and “others” has strengthened his identity within his ethnic group. Furthermore, the making of religious artefacts in this spirit endows the objects with spiritual meaning and forges a connection with other members of his group. It can be clearly seen that these symbols and practices often serve as markers of ethnic identity, helping to distinguish one ethnic group from another (

Mitchell 2006).

When we asked why the Tu are reluctant to marry people from other ethnic groups, we learned that one important reason, at least with respect to Islam, is related to religious belief. One of our local interviewees claimed that “under normal circumstances, I will not interfere in the choice of marriage partners of my children, and I do not generally require my children to find a marriage partner in our own ethnic group. Tibetans also marry the Tu and Bao’an (保安族, an ethnic group). This is still very common in our region. However, I generally do not let my children marry Muslim Hui because they insist that everyone must believe in Islam after marriage. We can’t accept this” (field notes in 2018).

From what has been discussed above, we find that that religious and ethnic identity are deeply intertwined, with religion often serving as a key element of ethnic identity. On the one hand, religious identity plays a positive role in strengthening ethnic cohesion. On the other hand, fundamentalist religious identity and militant ethnic identity may also lead to ethnic conflicts. A proper balance is required. Through shared religious beliefs and practices, individuals can establish a sense of community and belonging within their ethnic group and reinforce the boundaries that distinguish their group from others (

Mitchell 2006).

3.3. Folk Religion and Economic Development

Since the 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China, the government has publicly committed itself to the goal of promoting overall economic prosperity throughout the Chinese society. Since then, China has persistently explored ways to overcome poverty in economically disadvantaged areas. In addition to the industrialization of agricultural productivity, the government has targeted the development of tourism. In this regard, the promotion and display of intangible cultural resources for tourists has become an important vehicle for pursuing local prosperity.

The region of the Tu is poor in natural resources and their economy has consequently lagged behind. However, they enjoy access to heretofore untapped resources in the domain of culture and folk religion. Folk religion, as a local cultural system, is rich in ethnic characteristics and symbolic meanings. These cultural resources have become the seeds that have led to the development of cultural industries to promote economic development. Since 2006, the intangible cultural heritage movement has had a profound impact on local folk religion. That is, ethnic culture, heretofore somewhat hidden, has gradually been transformed into public culture displayed particularly to tourists (

Li and Liang 2014). The practice and public display of folk religious traditions among the Tu has therefore now taken on an important economic function. Ethnic culture it is now publicly displayed in the context of tourism by the Chinese from other parts of China.

From the outset of this movement, the Tu embroidery, based largely on the Tu religious symbols, has played an important economic role. In the past, embroidery among the Tu was mainly used within the family (especially as a dowry for women) or displayed in temples to bring down blessings. Gradually, having been defined officially as part of intangible cultural heritage that warrants governmental support, panxiu (盘绣, the embroidery of the Tu) has turned into a marketable commodity and has acquired a new economic function.

The income of the Tu women has greatly increased. After panxiu was publicly declared to be a major local manifestation of Chinese intangible cultural heritage, Huzhu County began recruiting local women who were engaged in panxiu. An embroidery industry was established to respond to the call for poverty alleviation and market involvement. This move not only provided new legitimacy and dignity to traditional female panxiu skills, but also dynamized the economic power of the region. The Tu women achieved increased economic and social participation through panxiu, with a concomitant increase in their social status.

Support for the Tu cultural heritage was provided not only for embroidery, but also for other elements of ethnic culture. Up till then, the Tu’s unique folk festival cycle had been largely ignored by the outside world. However, the growth of the tourism economy changed that. The central government declared that Qinghai should undertake ecological protection and sustainable development. In response, the local government implemented a series of tourism incentive policies. This led to the notion of “Greater Qinghai” and to the development of tourism. One aspect of this was the conversion of displays of local cultural heritage into sources of local income. For example, traditional religious festivals such as biangbianghui (梆梆会, folk religious festival) in Huzhu County and liuyuehui in Tongren County are now performed for tourists. Local people now view their local beliefs and folklore as potential sources of local economic development.

For instance, nadun is supposed to begin on the 12th day of the lunar month of July. Nevertheless, our research team observed that nadun was being performed before that day for media coverage. The village association even organized a special performance group to travel to Hong Kong to generate publicity. Similarly, in the case of nadun performed in Qijia village, huishouwu was performed not once, but four times to welcome the provincial and county leaders who arrived at different times. In principle, the purpose of the nadun festival is to thank and entertain the spirits rather than entertain people in the secular world. Nevertheless, motivated by the development agenda, local people flexibly use traditional cultural resources to promote the development of a modern economy. One justification for converting sacred rituals into folklore performance alludes to the principle that “spirits follow the needs of people”. Defenders of this process argue that communication between people and the spirits should be equal, reciprocal, mutually respectful and filled with understanding. People should worship the spirits, but the spirits in turn should address people’s actual needs. A symbiotic compromise emerges between sacredness and secularity.

3.4. Folk Religion and Harmony among Spirits, Nature, and Human Beings

Religious beliefs can also serve the function of psychological adjustment, providing people with psychic comfort and a sense of security. In other words, folk religion as practiced by ordinary people helps to fulfill their psychological needs (

Ho 2005). As can be seen in the table below (

Table 3), our questionnaire research documented the impact of local religion on the psychological adjustment of the Tu.

We found that many people attribute events that they cannot control to external supernatural powers. Religious belief allows people to deal with anxiety in their daily lives and to gradually develop self-confidence and optimism. Religion helps people to deal with suffering and with adversities in life (

Ma 2010). Religious beliefs within the Tu community serve different psychological needs for different people. Beliefs from different religious systems occupy different functional niches for the Tu. For example, at burial, the hope is for the dead to enter Paradise as quickly as possible. For that purpose, local people call on a Buddhist

Lama (喇嘛, Tibetan Buddhist monk) to recite the sutras. However, in order to prevent the souls of the dead from misbehaving and from harming the living, Daoist priests are invited to chant sutras and choose the places and the days for burial. To maximize the likelihood of good fortune, the Tu even invite Buddhist and Daoist specialists to participate together in a mixed ritual. In addition, the folk religious specialists such as

bo and

fala serve as mediators between the human and spiritual world and are believed to have the power to communicate with spirits. They perform rituals and ceremonies to heal the sick, protect against evil spirits, and ensure good harvest.

In short, people use religion as a vehicle for the pursuit of psychological comfort. Folk religion among the Tu motivates people to make efforts to improve their lives. Only 8% of the Tu surveyed believe that “fate is preordained, people can’t change their lives through hard work. Only spirits can solve difficulties”. Moreover, the interviewees stated that we cannot believe in illusions; our beliefs have to be based in the real world: “Above all, we have to be realistic. If I don’t work today, money will not fall from the sky. We are born with hands, eyes, and feet. Everyone should work hard, right? Self-reliance is essential. We can’t count on God for everything. People can’t just sit around and expect to eat. There is nothing for free in this world” (field notes in 2019). The general assumption derived from the Tu folk religion is that “wealth comes from being industrious” and that “a happy life has to be created with our own hands”. In that sense, the religious beliefs of most of the Tu are still rooted in the real world rather than in fatalistic dependence on the spirit world.

4. Conclusions

This paper discussed the folk religion of the Tu as practiced in Minhe and Huzhu County. We examined several Tu spirit beliefs as well as several Tu rituals. We have seen that in terms of actual daily practice, the Tu folk religion is embedded in the community life of the Tu in several domains: folk festivals, folk rituals, village associations, and the local farming system. The Tu folk religion, as practiced in the daily life of the community, does not create a rift between nature and society. Popular beliefs in coexistence and symbiosis lead the Tu to consider different species as participants in the same life and general culture. People and other life forms share the same world. Furthermore, The Tu folk religion provides the community with a general interpretive framework for seeing the world. The religious system functions to create a community that is socially integrated and has its own ethnic identity, pursues common economic development, and values external–internal harmony. In the conceptual world of the Tu, humans and nonhumans are in constant communication with each other and in essence belong to the same social order.

In addition, we are concerned that the Tu folk religion has been negatively affected by certain social challenges created by waves of secularization and rationalization. Folk religion is struggling to survive, to find its own living space and protect its own identity. It must also accommodate itself to the evolving policies of the Chinese government. We have seen that the worldview prevailing among the Tu has to some degree motivated the revival of folk religion. Folk religion reflects the internal cultural fabric of the Tu community. The Tu folk religious practice offers us a portrait of the daily lives of the Tu. By maintaining interaction and communication with spirits and nature, the Tu have successfully revived their folk religion within the context of state power—even securing for themselves governmental support for their cultural heritage in the context the tourist industry. However, they also carry out cultural production on their own, independently of government officials or tourists. The Tu cultural belief that spirits, nature and humans can be seen as a trinitarian unit is a central element that has permitted the Tu folk religion not only to survive but also to energetically revive.

We consider that the Tu constitute an interesting research population and that their folk religion is a valid focus of research. We used the analytic paradigm of animist ontology and the distinction between synchronic and diachronic patterns to understand the beliefs and practices of the Tu folk religion. In doing this, we have attempted as well to explore effective explanatory strategies for understanding the survival and revival of folk religion.