Streamable Services: Affinities for Streaming in Pre-Pandemic Congregational Worship

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Cultural Affinities within Organizations

2.2. Online Worship during the Pandemic

2.3. Affinities for Streaming in Worship

3. Data

3.1. The National Congregations Study

3.2. Variables

3.2.1. Dependent Variables

3.2.2. Independent Variables

3.2.3. Controls

4. Methods

5. Results

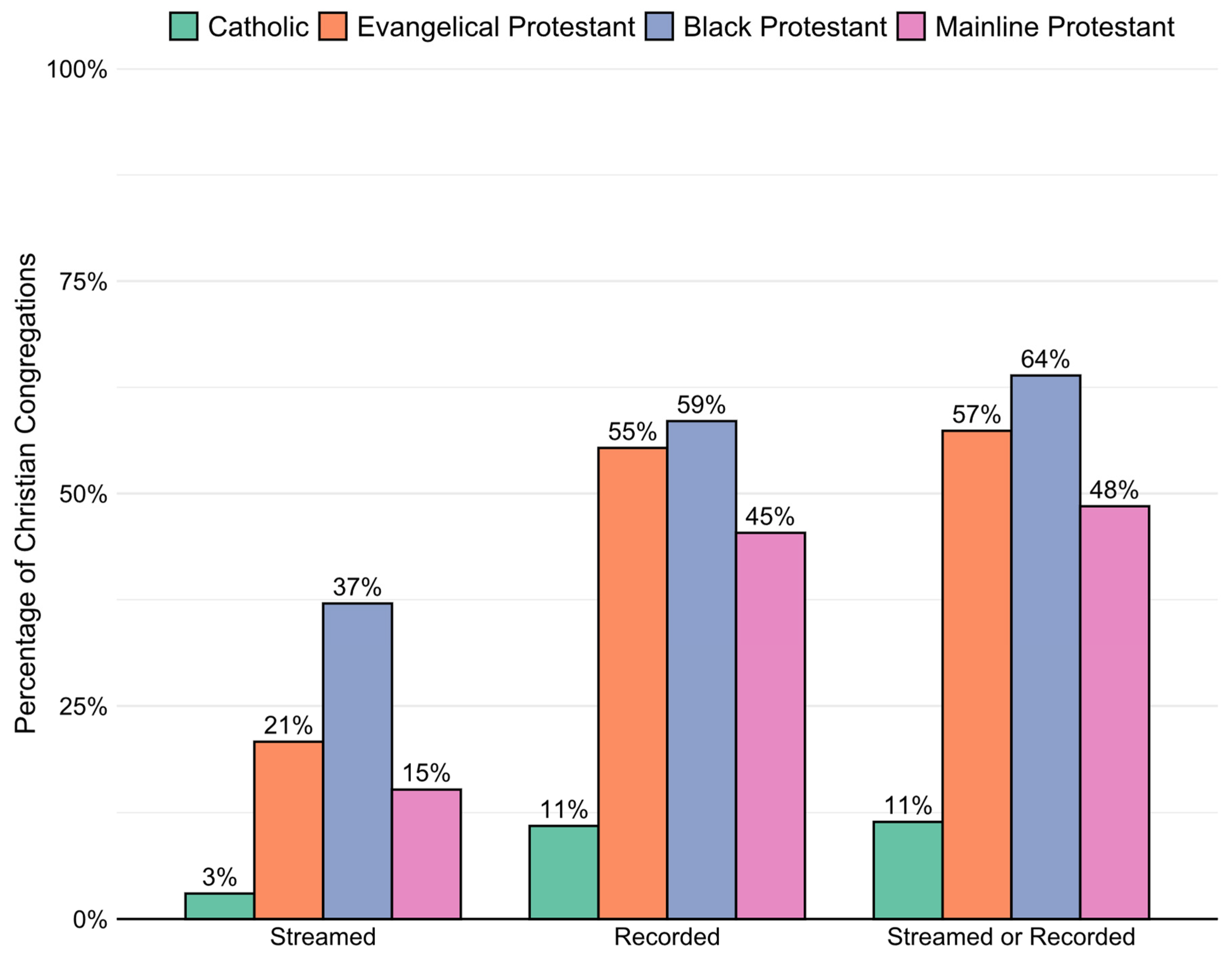

5.1. Congregational Streaming and Recording by Religious Tradition

5.2. Enthusiastic Worship and Streaming Practices

5.3. Multiple Regression Results

5.4. Interaction between Religious Tradition and Enthusiastic Worship

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The German term Weber uses is “Wahlverwandtschaft”, which Parsons renders as “correlation” in his 1930 translation (Weber [1905] 1930). Here, I employ the term “elective affinity”, derived from the more recent Peter Baehr and Gordon C. Wells translation (Weber [1905] 2002), which is more broadly in use in the English scholarship of Weber today and does not conflate the concept Weber was articulating with a cold, statistical relationship (McKinnon 2010). |

| 2 | |

| 3 | Nine congregations reported an annual income of USD 0. As the natural log of zero is undefined, I adjusted these congregations’ incomes to USD 1, or zero once naturally logged. |

| 4 | The results are substantively identical in models where cases with missing values on one or both of the financial variables were listwise deleted, as well as in models where the financial controls were not included. |

References

- Adler, Gary, Daniel DellaPosta, and Jane Lankes. 2022. Aesthetic Style: How Material Objects Structure an institutional Field. Sociological Theory 40: 51–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, Joseph. 2010. Social Sources of the Spirit: Connecting Rational Choice and Interactive Ritual Theories in the Study of Religion. Sociology of Religion 71: 432–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, William P., and Elizabeth G. Pontikes. 2008. The Red Queen, Success Bias, and Organizational Inertia. Management Science 54: 1237–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barro, Robert J., and Rache M. McCleary. 2003. Religion and Economic Growth Across Countries. American Sociological Review 68: 760–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Lulu, Elazar. 2021. Zooming In and Out of Virtual Jewish Prayer Services During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 60: 852–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertels, Stephanie, Jennifer Howard-Grenville, and Simon Pek. 2016. Cultural Molding, Shielding, and Shoring at Oilco: The Role of Culture in the Integration of Routines. Organization Science 27: 537–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Heidi A. 2012. Understanding the Relationship between Religion Online and Offline in a Networked Society. Journal of the American Academy of Religion 80: 64–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, Mark. 2004. Congregations in America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chaves, Mark, Shawna Anderson, Alison Eagle, Mary Hawkins, Anna Holleman, and Joseph Roso. 2020a. Introducing the Fourth Wave of the National Congregations Study. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 59: 646–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, Mark, Shawna Anderson, Alison Eagle, Mary Hawkins, Anna Holleman, and Joseph Roso. 2020b. National Congregations Study. Cumulative Data File and Codebook. Durham, NC: Duke University Department of Sociology. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Yoel. 2014. God, Jews and the Media: Religion and Israel’s Media. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Demerath, N. J., Peter Dobkin Hall, Terry Schmitt, and Rhys H. Williams. 1998. Sacred Companies: Organizational Aspects of Religion and Religious Aspects of Organizations. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- DiMaggio, Paul, and Walter W. Powell. 1983. The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields. American Sociological Review 48: 147–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draper, Scott. 2014. Effervescence and Solidarity in Religious Organizations. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 53: 229–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drescher, Elizabeth. 2011. Tweet If You [Heart] Jesus: Practicing Church in the Digital Reformation. New York: Morehouse Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim, Emile. 1995. The Elementary Forms of Religious Life. Translated by Karen E. Fields. New York: The Free Press. First published 1912. [Google Scholar]

- Ellingson, Stephen. 2007. The Megachurch and the Mainline: Remaking Religious Tradition in the Twenty-First Century. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, Leslie J., and Andrew Village. 2021. This Blessed Sacrament of Unity? Holy Communion, the Pandemic, and the Church of England. Journal of Empirical Theology 34: 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, Leslie J., Andrew Village, and S. Anne Lawson. 2020. Impact of COVID-19 on Fragile Churches: Is the Rural Situation Really Different? Rural Theology 18: 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedland, Roger, and Robert Alford. 1991. Bringing Society Back in: Symbols, Practices, and Institutional Contradictions. In The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis. Edited by Walter W. Powell and Paul J. DiMaggio. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, pp. 232–63. [Google Scholar]

- Frost, Jonathon K., and Norma E. Youngblood. 2014. Online Religion and Religion Online: Reform Judaism and Web-Based Communication. Journal of Media and Religion 13: 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelman, Andrew. 2007. Struggles with Survey Weighting and Regression Modeling. Statistical Science 22: 153–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorrell, Angela Williams. 2019. Always On: Practicing Faith in a New Media Landscape. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Hamner, Lea, Polly Dubbel, Ian Capron, Andy Ross, Amber Jordan, Jaxon Lee, Joanne Lynn, Amelia Ball, Simranjit Narwal, Sam Russell, and et al. 2020. High SARS-CoV-2 Attack Rate Following Exposure at a Choir Practice—Skagit County, Washington, March 2020. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 69: 606–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, Spencer H., and Kevin G. Corley. 2011. Clean Climbing, Carabiners, and Cultural Cultivation: Developing an Open-Systems Perspective of Culture. Organization Science 22: 391–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haveman, Heather A. 1992. Between a Rock and a Hard Place: Organizational Change and Performance Under Conditions of Fundamental Environmental Transformation. Administrative Science Quarterly 37: 48–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayward, R. David, and Markus Kemmelmeier. 2011. Weber Revisited: A Cross-National Analysis of Religiosity, Religious Culture, and Economic Attitudes. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 42: 1406–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holleman, Anna, Joseph Roso, and Mark Chaves. 2022. Religious Congregations’ Technological and Financial Capacities on the Eve of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Review of Religious Research 64: 163–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Jessica. 2018. Biblical Porn: Affect, Labor, and Pastor Mark Driscoll’s Evangelical Empire. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, Erin F., David E. Eagle, Jennifer Headley, and Anna Holleman. 2021. Pastoral Ministry in Unsettled Times: A Qualitative Study of the Experience of Clergy During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Review of Religious Research 64: 375–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilde, Jeanne Halgren. 2002. When Church Became Theatre: The Transformation of Evangelical Architecture and Worship in Nineteenth-Century America. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, Swee Hong, and Lester Ruth. 2017. Lovin’ on Jesus: A Concise History of Contemporary Worship. Nashville: Abingdon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Loveland, Anne C., and Otis B. Wheeler. 2003. From Meetinghouse to Megachurch: A Material and Cultural History. Columbia: University of Missouri Press. [Google Scholar]

- McKinnon, Andrew M. 2010. Elective Affinities of the Protestant Ethic: Weber and the Chemistry of Capitalism. Sociological Theory 281: 108–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeish, Daniel. 2018. Thanks Coefficient Alpha, We’ll Take it From Here. Psychological Methods 23: 412–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, John W., and Brian Rowan. 1977. Institutionalized Organizations: Formal Structure as Myth and Ceremony. American Journal of Sociology 83: 340–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, Pippa, and Ronald Inglehart. 2004. Religion, the Protestant Ethic, and Moral Values. In Sacred and Secular: Religion and Politics Worldwide. Edited by Pippa Norris and Ronald Inglehart. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, pp. 159–79. [Google Scholar]

- Rindova, Viola, Elene Dalpiaz, and Davide Ravasi. 2011. A Cultural Quest: A Study of Organizational Use of New Cultural Resources in Strategy Formation. Organization Science 22: 413–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roso, Joseph. 2022. The Churches They Are a Changin’: Processes of Change in Worship Services. Sociology of Religion. [Google Scholar]

- Roso, Joseph, Anna Holleman, and Mark Chaves. 2020. Changing Worship Practices in American Congregations. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 59: 675–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruth, Lester, and Swee Hong Lim. 2021. A History of Contemporary Praise & Worship. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Seabright, Paul, and Eva Raiber. 2020. U.S. Churches’ Response to COVID-19: Results from Facebook. Center for Economic Policy Research Discussion Paper Series DP15566. Washington, DC: Center for Economic Policy Research. [Google Scholar]

- Steensland, Brian, Jerry Z. Park, Mark D. Regnerus, Lynn D. Robinson, W. Bradford Wilcox, and Robert D. Woodberry. 2000. The Measure of American Religion: Toward Improving the State of the Art. Social Forces 79: 291–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swidler, Ann. 1986. Culture in Action: Symbols and Strategies. American Sociological Review 51: 273–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, Patricia H., William Ocasio, and Michael Lounsbury. 2012. The Institutional Logics Perspective: A New Approach to Culture, Structure, and Process. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thumma, Scott. 2012. Virtually Religious: Technology and Internet Use in American Congregations. Report from Faith Communities Today. Available online: https://faithcommunitiestoday.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Virtually-Religious-2010.pdf (accessed on 21 February 2023).

- Village, Andrew, and Leslie J. Francis. 2022a. Giving Up on the Church of England in the Time of Pandemic: Individual Differences in Responses of Non-ministering Members to Online Worship and Offline Services. Journal of Anglican Studies, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Village, Andrew, and Leslie J. Francis. 2022b. Lockdown Worship in the Church of England: Predicting Affect Responses to Leading or Accessing Online and In-Church Services. Journal of Beliefs & Values 44: 280–96. [Google Scholar]

- Voas, David, and Mark Chaves. 2016. Is the United States a Counterexample to the Secularization Thesis? American Journal of Sociology 121: 1517–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, Max. 1930. The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. Translated by Talcott Parsons. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. First published 1905. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, Max. 2002. The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. Translated by Peter Baehr, and Gordon C. Wells. New York: Penguin Books. First published 1905. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, Klaus, and M. Tina Dacin. 2011. The Cultural Construction of Organizational Life: Introduction to the Special Issue. Organization Science 22: 287–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Fei, Ting Yu, Ronghui Du, Guohui Fan, Ying Liu, Zhibo Liu, Jie Xiang, Yeming Wang, Bin Song, Xiaoying Gu, and et al. 2020. Clinical Course and Risk Factors for Mortality of Adult Inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: A Retrospective Cohort Study. The Lancet 395: 1054–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Mean/ Proportion | SD | Range | Non-Missing Values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enthusiasm scale | 3.04 | 2.03 | 1–6 | 1136 |

| Amen | 0.714 | -- | 0–1 | 1188 |

| Applause | 0.622 | -- | 0–1 | 1190 |

| Drums | 0.423 | -- | 0–1 | 1171 |

| Jump | 0.304 | -- | 0–1 | 1188 |

| Raising hands | 0.680 | -- | 0–1 | 1178 |

| Tongues | 0.294 | -- | 0–1 | 1173 |

| Religious Tradition | ||||

| Catholic | 0.067 | -- | 0–1 | 1195 |

| White Evangelical | 0.469 | -- | 0–1 | 1195 |

| Black Protestant | 0.234 | -- | 0–1 | 1195 |

| Mainline Protestant | 0.230 | -- | 0–1 | 1195 |

| Facebook page | 0.718 | -- | 0–1 | 1183 |

| Website | 0.702 | -- | 0–1 | 1184 |

| Projection in worship | 0.491 | -- | 0–1 | 1190 |

| Owns building | 0.834 | -- | 0–1 | 1192 |

| Adults in congregation | 122 | 326 | 7–30,000 | 1195 |

| Percent of adults >60 years old | 41.12 | 26.48 | 0–100 | |

| Percent of adults in households with <$35,000 annual income | 25.66 | 26.82 | 0–100 | 979 |

| Congregation’s income | $387,722 | $1,604,495 | 0–$79,000,000 | 903 |

| Multisite | 0.065 | -- | 0–1 | 1195 |

| Year founded | 1947 | 57.7 | 1588–2018 | 1157 |

| Liberal theology | 2.87 | 1.56 | 1–7 | 1136 |

| Region | ||||

| Northeast/Mid- Atlantic | 0.121 | -- | 0–1 | 1195 |

| East North Central/ West North Central | 0.250 | -- | 0–1 | 1195 |

| South Atlantic/ East South Central/ West South Central | 0.472 | -- | 0–1 | 1195 |

| Mountain/Pacific | 0.156 | -- | 0–1 | 1195 |

| Rural census tract | 0.269 | -- | 0–1 | 1195 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (constant) | −1.242 *** (0.155) | −10.584 ** (3.707) | −1.987 *** (0.193) | −9.949 ** (3.725) |

| Religious Tradition | ||||

| Catholic (ref.) | (ref.) | (ref.) | (ref.) | (ref.) |

| Evangelical Protestant | 2.653 *** (0.199) | 3.734 *** (0.362) | 2.270 *** (0.207) | 3.622 *** (0.366) |

| Black Protestant | 2.140 *** (0.236) | 3.988 *** (0.405) | 0.972 *** (0.282) | 3.366 *** (0.441) |

| Mainline Protestant | 2.056 *** (0.208) | 3.231 *** (0.348) | 2.153 *** (0.216) | 3.218 *** (0.348) |

| Enthusiastic worship | 0.380 *** (0.0512) | 0.208 *** (0.630) | ||

| Facebook page | 1.281 *** (0.237) | 1.191 *** (0.240) | ||

| Website | 0.741 ** (0.269) | 0.749 ** (0.272) | ||

| Projection in worship | 0.877 *** (0.190) | 0.691 *** (0.198) | ||

| Owns building | 0.158 (0.330) | 0.191 (0.568) | ||

| Adults in congregation (natural logged) | 0.575 *** (0.107) | 0.574 *** (0.108) | ||

| Percent of adults >60 years old | −0.003 (0.004) | −0.000 (0.004) | ||

| Percent of adults in households with <$35,000 annual income | −0.002 (0.004) | −0.005 (0.004) | ||

| Congregation’s income (natural logged) | 0.114 ^ (0.058) | 0.105 ^ (0.059) | ||

| Is multisite | −0.598 ^ (0.341) | −0.687 * (0.048) | ||

| Year founded | 0.001 (0.002) | 0.000 (0.002) | ||

| Liberal theology | 0.004 (0.949) | −0.006 (0.065) | ||

| Region | ||||

| Northeast/Mid-Atlantic (ref.) | (ref.) | (ref.) | ||

| South Atlantic/East South Central/West South Central | 0.297 (0.288) | 0.357 (0.291) | ||

| East North Central/West North Central | −0.041 (0.293) | 0.074 (0.298) | ||

| Mountain/Pacific | −0.355 (0.321) | −0.276 (0.325) | ||

| Rural census tract | 0.003 (0.255) | 0.001 (0.256) | ||

| N | 1037 | 1037 | 1037 | 1037 |

| Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (constant) | 0.309 * (0.141) | 0.190 (0.148) | −7.423 (3.603) |

| Enthusiastic worship | 0.269 *** (0.041) | 0.313 *** (0.313) | 0.267 *** (0.060) |

| Catholic | −2.065 *** (0.180) | −1.440 *** (0.292) | −2.756 *** (0.403) |

| Catholic x enthusiastic worship | −0.309* (0.121) | −0.335 * (0.136) | |

| Facebook page | 1.190 *** (0.238) | ||

| Website | 0.756 ** (0.238) | ||

| Projection in worship | 0.741 *** (0.191) | ||

| Owns building | 0.183 (0.337) | ||

| Adults in congregation (natural logged) | 0.591 *** (0.110) | ||

| Percent of adults >60 years old | 0.001 (0.004) | ||

| Percent of adults in households with <$35,000 annual income | −0.005 (0.004) | ||

| Congregation’s income (natural logged) | 0.099 (0.060) | ||

| Is multisite | −0.678 ^ (0.348) | ||

| Year founded | 0.001 (0.002) | ||

| Liberal theology | −0.030 (0.059) | ||

| Region | |||

| Northeast/Mid-Atlantic (ref.) | (ref.) | ||

| South Atlantic/East South Central/West South Central | 0.393 (0.289) | ||

| East North Central/West North Central | 0.114 (0.297) | ||

| Mountain/Pacific | −0.119 (0.328) | ||

| Rural census tract | 0.047 (0.255) | ||

| N | 1037 | 1037 | 1037 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Roso, J. Streamable Services: Affinities for Streaming in Pre-Pandemic Congregational Worship. Religions 2023, 14, 641. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14050641

Roso J. Streamable Services: Affinities for Streaming in Pre-Pandemic Congregational Worship. Religions. 2023; 14(5):641. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14050641

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoso, Joseph. 2023. "Streamable Services: Affinities for Streaming in Pre-Pandemic Congregational Worship" Religions 14, no. 5: 641. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14050641

APA StyleRoso, J. (2023). Streamable Services: Affinities for Streaming in Pre-Pandemic Congregational Worship. Religions, 14(5), 641. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14050641