Engaging with Religious History and Theological Concepts through Music Composition: Ave generosa and The Song of Margery Kempe

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Conceptual Background

3. Ave generosa

The event took place in a Swabian town called Rudesheim. A priest in a certain place, with the day ended and night coming on, entered the church in order to light the lamps in the sanctuary, when lo, he saw that there were two candles still alight and shining on the altar, for a young scholar, who was zealous and familiar with the care of the divine services, had already gone into the church. Now when the priest asked why he had omitted to extinguish the candles, the young man replied that he had indeed already extinguished them. Then the priest went up to perform the task himself, but discovered an unfolded altar cloth such as is unwrapped for the celebration of the divine mysteries. Whilst he stood there, stupefied, the young man fell on the ground and in ecstasy, cried out: “The sword of the Lord has struck us!” The priest thought he had been struck down, and hastened to raise him from the ground. But the young man, having no wound, gave forth the utterance: “If we see that there are letters on the altar cloth, we shall not die.” The priest then thought to himself that the youth was crying out through fear, but nonetheless went up to the altar again, and in the place where the sacred vessels are set out, he found on the cloth five letters in the form of a cross, written without human hand. They were, horizontally: A.P.H; and vertically: K.P.D. When he saw this and had carefully noted it, the young man recovered his strength and got up, whilst the priest, having folded the altar cloth and extinguished the candles, went home mystified. The letters remained for seven days, but on the eighth day and thereafter, they were no longer visible. Now the priest made known the object of his speculation to certain wise and devout persons, but none could understand what it might mean until—sixteen years having passed,—news spread through the land that the blessed Hildegard was filled with light by the Holy Spirit. So the priest went to her and merited to understand the meaning of the prophesy that she, by means of the Holy Spirit, taught him. Just as Daniel of old read what appeared on the wall, so Hildegard read what was written on the cloth, explaining the letters in this way:

K—kyrium, P—presbyter, D—derisit, A—ascendit, P—poenitans, H—homo.2

When he heard this the priest trembled with fear, and accused his sinful conscience. So, having been admonished he became a monk and strove by means of penance to amend the negligence of his past life. Thus just in the way the blessed maiden had explained the letters, he ascended to a higher and more austere life, and showed himself a perfect servant of God by his holy way of life.

- the freshness of dawn with reference to the pristine state of nature, through

- the transgression of humans, to

- an evocation of the blazing of the midday sun, and

- an abstraction into pure lyricism and melody, with a final homage to Hildegard on account of her redemptive role and praise of the redemptrix Mary.

4. The Song of Margery Kempe

For Kempe, religious media are not cheap substitutes for religious experience but, rather, a mode of having a religious experience. Medieval culture abounds with enlivened things, objects that transform themselves and do things to the people around them …. These lively things represent intersections of life and death, miracle and mimesis, the extraordinary and the mundane. Kempe’s experiences with crucifixes show how public icons and objects could be engaged in intensely subjective encounters.

BRIGHT SPOTLIGHT ON MARGERY UP SUDDENLY

Margery: [from behind chair, as if in the dock being questioned]

My name is Margery Kempe. [question] I am from Lynn in Norfolk, the daughter of a good man. I have a good man for my husband also. [question] You call me a false strumpet, a Lollard, and I say I am not afraid to go to prison for the love of my Lord, who suffered much more for my love than I may for his.

When the woman in the Gospel heard our Lord preach, she came before him and said in a loud voice: “Blessed be the womb that bore you, and the breasts that gave you suck”. Then our Lord replied to her: “In truth, so are they blessed who hear the word of God and keep it”. And therefore, sir, I think the Gospel gives me leave to speak of God.

[She has a faraway look, drawing into herself as she is led away]

LIGHTS DOWN

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Examples include Peter Maxwell Davies’ Ave Maris Stella (1975), whose technique, affect and sound-world were directly influential on Ave generosa; and John Tavener’s To a Child Dancing in the Wind (1983) and Icon of Light (1983). |

| 2 | [This] priest has mocked the Lord; in repentance let the man ascend. |

| 3 | Silvas subsequently published a slightly revised translation in book form (Silvas 1999). |

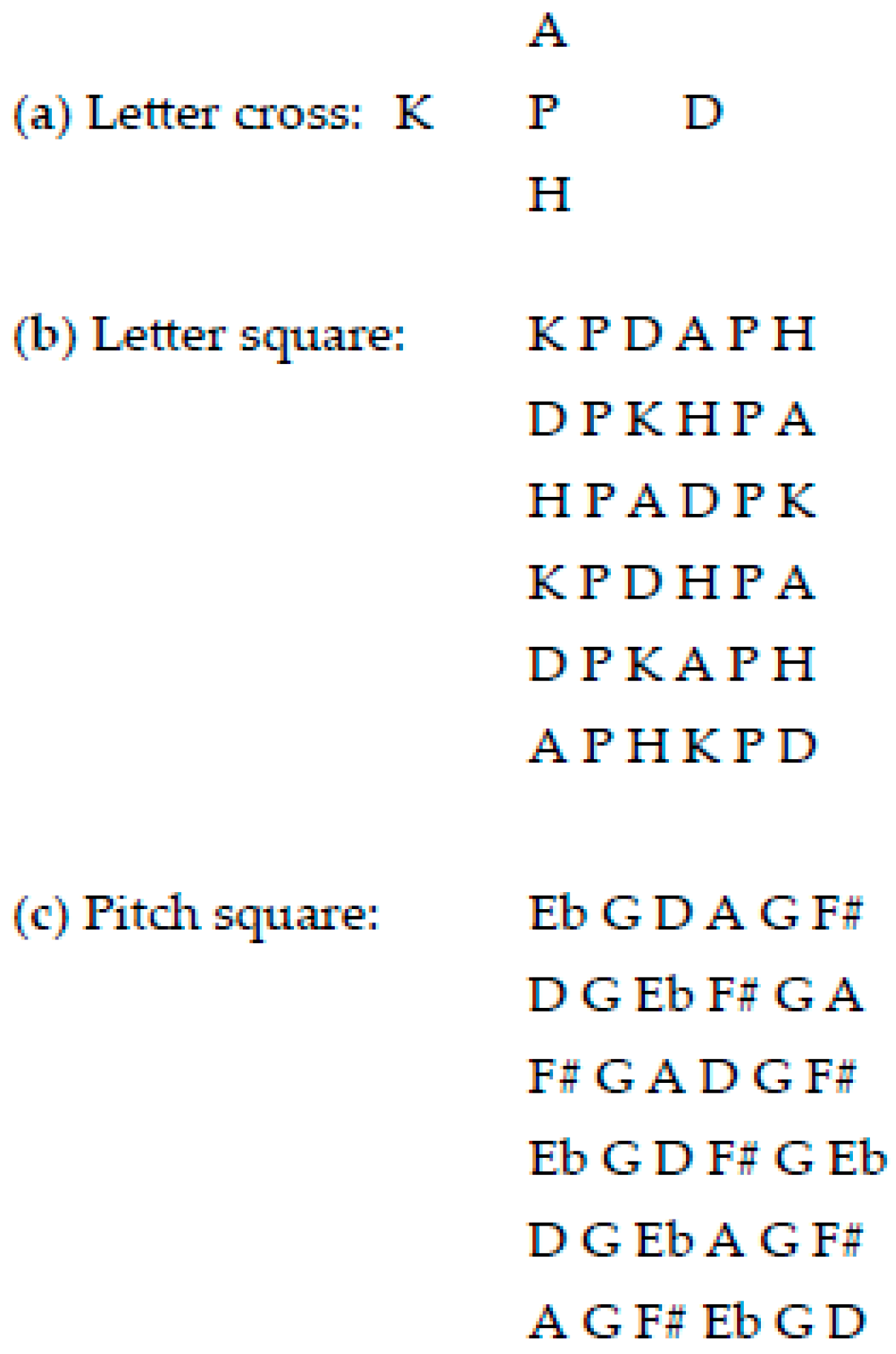

| 4 | Tavener’s method was first identified by Geoffrey Haydon: ‘John calls it his “Byzantine palindrome”… an arrangement of twenty-five letters… read either forwards or backwards, spells out the same message…[which] can be found on Byzantine gravestones’ (Haydon [1995] 1998, p. 164). For an example of how the method can work in practice, see my book chapter Inglis (2020). |

| 5 | A recording of an unadorned solo vocal performance is available online at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n9hBPuPeEkU (accessed on 28 February 2023). An interesting instrumental realisation directed by Jordi Savali can be heard at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mnSPI2S5xPY (accessed on 28 February 2023). |

| 6 | Modern English translations include Windeatt ([1985] 1994), Staley (2001) and Bale (2015). In recent years interest in Margery has grown beyond the academic community. She, and the ‘recordings’ of her experiences found in her Book, is one of three pioneering women profiled in experimental artist and musician Cosey Fanni Tutti’s Re-Sisters (the others are electronic musician Delia Derbyshire and Tutti herself) (Tutti 2022). She is also, in fictionalised form, the joint subject (with Julian of Norwich) of Victoria MacKenzie’s novel For Thy Great Pain Have Mercy on My Little Pain (MacKenzie 2023). |

| 7 | The opera received its concert premiere from Loré Lixenberg (mezzo-soprano) at the Riverside Studios, Hammersmith, London, UK on 8 August 2008, promoted by Tête-à-Tête: The Opera Festival and supported by funding from the Bliss Trust/PRS Foundation. The first stage production was at the same venue and festival on 1–2 August 2009, financially supported by the RVW Trust. Margery was played by, again, Loré Lixenberg; the designer was Paul Burgess; the technical director Marius Rønning, and the lighing designer Mark Doubleday. An abbreviated video performance was shown—with accompanying introductory talk—at the symposium Moving Performances, Oxford University, 23 June 2016. Excerpts were also displayed, as noted, in the online Gallery of the BIAPT conference, in July 2022. Aspects of the opera have been discussed previously in Inglis (2016) and Inglis (2019). |

References

- Bale, Anthony. 2015. The Book of Margery Kempe, translation ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bale, Anthony. 2021. Margery Kempe: A Mixed Life. London: Reaktion Books. [Google Scholar]

- Fassler, Margot. 1998. Composer and Dramatist. In Voice of the Living Light: Hildegard of Bingen and Her World. Edited by Barbara Newman. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, pp. 149–75. [Google Scholar]

- Glück, Robert. 2020. Margery Kempe. New York: New York Review of Books. First published 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Haydon, Geoffrey. 1998. John Tavener: Glimpses of Paradise. London: Indigo. First published 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Inglis, Brian. 2015. The Song of Margery Kempe. Music Score. Chipping Norton: Composers Edition. [Google Scholar]

- Inglis, Brian. 2016. The Liminal Zone of Opera: (Unaccompanied) Operatic Monodrama and The Song Of Margery Kempe. In Music on Stage Volume 2. Edited by Luis Campos and Fiona Jane Schopf. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Inglis, Brian. 2019. Musical composition and mystical spirituality. In Enlivening Faith: Music, Spirituality and Christian Theology. Edited by June Boyce-Tillman, Roberts Stephen B. and Jane Erricker. Music and Spirituality vol. 9. Oxford: Peter Lang, pp. 25–44. [Google Scholar]

- Inglis, Brian. 2020. ‘Dumped modernism’? The Interplay of Musical Construction and Spiritual Affect in John Tavener and his To a Child Dancing in the Wind. In Heart’s Ease: Spirituality in the Music of John Tavener. Edited by June Boyce-Tillman and Anne-Marie Forbes. Music and Spirituality vol. 11. Oxford: Peter Lang, pp. 113–34. [Google Scholar]

- Inglis, Brian. 2021. Ave Generosa. Music Score. Chipping Norton: Composers Edition. [Google Scholar]

- Inglis, Brian. 2023. The Song of Margery Kempe. Opera Libretto. Chipping Norton: Composers Edition. [Google Scholar]

- King-Lenzmeier, Anne H. 2001. Hildegard of Bingen: An Integrated Vision. Minnesota: The Order of St Benedict, Inc. Minnesota: The Liturgical Press. [Google Scholar]

- Leclercq, Jean. 1982. The Love of Learning and the Desire for God: A Study of Monastic Culture. Translated by Catharine Misrahi. New York: Fordham University Press. [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie, Victoria. 2023. For Thy Great Pain Have Mercy on My Little Pain. Novel. London: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Moody, Ivan. 2021. Music as theology. The Musical Times 162/1954: 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, Barbara. 1987. Sister of Wisdom: St Hildegard’s Theology of the Feminine. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, Barbara. 1988. Saint Hildegard of Bingen, Symphonia: A Critical Edition of the Symphonia Armonie Celestium Revelationum. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Page, Christopher. 1983. Abbess Hildegard of Bingen: Sequences and Hymns. Newton Abbott: Antico Edition. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, Stephen B. 2020. John Tavener’s Musical Theology of Religions. In Heart’s Ease: Spirituality in the Music of John Tavener. Edited by June Boyce-Tillman and Anne-Marie Forbes. Music and Spirituality vol. 11. Oxford: Peter Lang, pp. 33–51. [Google Scholar]

- Scholl, Robert, and Sander van Maas. 2017. Contemporary Music and Spirituality. Abingdon and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Silvas, Anna. 1987. Saint Hildegard of Bingen and the Vita Sanctae Hildegardis, translation ed. Tjurunga 32: 46–59. [Google Scholar]

- Silvas, Anna. 1999. Jutta & Hildegard: The Biographical Sources. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Staley, Lynn. 2001. The Book of Margery Kempe, translation ed. New York and London: W. W. Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Tagg, Philip. 2013. Music’s Meanings. Larchmont and Huddersfield: Mass Media Music Scholars’ Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tutti, Cosey Fanni. 2022. Re-Sisters: The Lives and Recordings of Delia Derbyshire, Margery Kempe and Cosey Fanni Tutti. London: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Windeatt, Barry A. 1994. The Book of Margery Kempe, translation ed. Harmondsworth: Penguin. First published 1985. [Google Scholar]

| Latin Original | English Translation |

|---|---|

| Ave generosa, gloriosa et intacta puella; tu, pupilla castitatis, tu, materia sanctitatis, que Deo placuit! | Hail, girl of a noble house, shimmering and unpolluted, you, pupil in the eye of the chastity, you, essence sanctity, who were pleasing to God! |

| nam hec superna infusion in te fuit, quod supernum verbum in te carmen induit, | For the Heavenly potion was poured into you, in that the Heavenly word received a raiment of flesh in you. |

| Tu, candidum lilium, quod Deus ante omnem creaturam inspexit. | You, the lily that dazzles, whom God knew before all his other creatures. |

| O pulcherrima et dulcissima; quam valde Deus in te delecatabatur: cum amplexione caloris sui in te posuit ita quod filius eius de te lactatus est. | O most beautiful and delectable one; how greatly God delighted in you! In the clasp of His fire He implanted in you so that His Son might be suckled by you. |

| Venter enim tuus gaudium habuit, cum omnis celestis symphonia de te sonuit, quia, virgo filium Dei portasti, ubi castitas tua in Deo claruit. | Thus your womb held joy, when all the Heavenly harmony chimed out for you, because, o virgin, you bore the Son of God whence your chastity blazed in God. |

| Viscera tua guadium habuerunt, sicut gramen super quod ros cadit cum ei viriditatem infudit; ut et in te factum est, o mater omnis gaudii. | Your womb knew delight like the grassland touched by dew and drenched in its freshness; so it was done in you, o mother of all joy. |

| Nunc omnis Ecclesia in gaudio rutilet ac in symphonia sonnet propter dulcissimam virginem et laudibilem Mariam Dei genitricem. Amen. | Now let all Ecclesia glimmer with the dawn of joy and let it resound in music for the sweetest virgin, Mary compelling all praise, mother of God. Amen. |

| Section | Start Time | Rehearsal Letter(s) | Description | Instruments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0′00″ | A/B | ‘Pastoral’ introduction (birdsong-like figures) | Flute, clarinet |

| 2 | 1′20″ | C/D | Birdsong-like figures/music based on pitch square | Glockenspiel & clarinet, flute, piano, harp |

| 3 | 2′19″ | E | Transition | All |

| 4 | 3′11″ | F | Cadenza (virtuosic solo) | Harp |

| 5 | 3′25″ | G | Bridge passage, including reference to ‘in Deo claruit’ chant phrase | Flute, clarinet, harp, piano, vibraphone |

| 6 | 4′01″ | H | Central high point: ‘in Deo claruit’ chant combined with Messiaen quote | Flute, clarinet, harp, piano, vibraphone |

| 7 | 4′34″ | I | Bridge passage. Quotation of ‘Mariam’ chant phrase | Flute |

| 8 | 4′48″ | J-L | Music originating in Messiaen quote | Flute, clarinet, various percussion including vibraphone, harp, piano, piccolo |

| 9 | 6′50″ | M | Coda: melody based on ‘Venter enim’ and ‘cum amplexione’ chant phrases | Flute + clarinet, harp, percussion |

| Scene/Section | Title | Episode/Description | Source | How Dramatised |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Margery’s temptation and madness | the spiritual crisis associated with Margery’s postpartum psychosis following the birth of her first child | Book I chapter 1; concluding prayer of Book II | scenario shows Margery attempting to pray (the Veni creator spiritus) but being assailed by visions of tormenting demons |

| 2 | Margery’s conversion | the celestial vision of Jesus which roused her from despair, and inspired her to embark on a life of piety | Book I chapter 1 | depicts her conversion experience and includes representations of the ‘heavenly melody’ she hears and the first iterations of her gift of tears |

| 3 | Margery’s trial | her trial for suspected heresy (Lollardism) at Leicester | Book I chapter 46–49 | scenario shows Margery behind a chair, as if in dock, subjected to questions from an invisible and inaudible interlocutor |

| Transition | Transition | sounds of birdsong and bells from offstage | stage in darkness | |

| 4 (Epilogue) | Margery’s epiphany | Margery’s review of her life and spiritual progress | Various, including concluding prayer of Book II | structured as an extended prayer (with reflective interjections) based on conclusion of Veni creator spiritus |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Inglis, B.A. Engaging with Religious History and Theological Concepts through Music Composition: Ave generosa and The Song of Margery Kempe. Religions 2023, 14, 640. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14050640

Inglis BA. Engaging with Religious History and Theological Concepts through Music Composition: Ave generosa and The Song of Margery Kempe. Religions. 2023; 14(5):640. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14050640

Chicago/Turabian StyleInglis, Brian Andrew. 2023. "Engaging with Religious History and Theological Concepts through Music Composition: Ave generosa and The Song of Margery Kempe" Religions 14, no. 5: 640. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14050640

APA StyleInglis, B. A. (2023). Engaging with Religious History and Theological Concepts through Music Composition: Ave generosa and The Song of Margery Kempe. Religions, 14(5), 640. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14050640