In his 1584 dialogic treatise on art,

Il Riposo, the Florentine author Raffaello Borghini has his interlocutors imagine themselves walking from church to church in Florence, evaluating the merit of the artworks they encounter (

Borghini 2007). Borghini’s treatise is often discussed as a post-Tridentine work of art theory in that it registers concerns about religious reform and its consequences for art in the decades following the Council of Trent, convened to clarify Catholic policies after the Protestant Reformation and concluded in 1563 (

Hall 1979, pp. 55–64;

Lingo 2013). A tension between religious and aesthetic criteria structures the discourse in

Il Riposo. Borghini often treats the style of particular artwork in a wholly different chapter than the same work’s religious iconography. This approach mirrors other post-Tridentine art treatises, like that of Gregorio Comanini’s 1591

Il Figino, which has the responsible prelate Ascanio Martinengo contrast the moral imperative of religious art with the fantastical inventions of artists such as Giuseppe Arcimboldo (

Comanini 2001). Borghini’s imagined troupe of discussants engages with the complex interactions of art and reform from a theoretical perspective, firmly situated within the larger late-sixteenth-century outpouring of treatises on art (

Barocchi 1960–1962).

There was, however, a different set of visitors whom we can envision traveling from church to church in the name of evaluating art: the ecclesiastical visitor, charged with inspecting the churches in his diocese. Visitations vastly increased in frequency in the post-Tridentine period as they played a crucial role in Catholic reform. Part of the visitor’s task was to pass judgment on altarpieces and other sacred images, determining which met the new standards of decorum. He and his associates toured various churches, such as Borghini’s interlocutors imagined themselves doing, casting a discerning gaze upon the altarpieces contained within. The visitor, furthermore, had the authority to recommend changes, ordering the removal, transfer, cleaning, or amendment of any indecorous images. This article will examine the texts that emerged from those encounters, shifting from theories of art reform after Trent to its implementation. This analysis focuses on apostolic visitations in the Vatican archives from a broadly post-Tridentine period, ranging from 1564 to 1630. Apostolic visitations, conducted in and beyond Rome but always on the authority of the pope, provide a view of image concerns from the Catholic center. This corpus demonstrates that the visitor’s definition of artistic decorum—and of the very categories of what we might call ‘art’ today—was based more on function than form, giving priority to issues related to ritual use, such as conservation, consecration, and location. The visitors’ functional definition of terms such as altarpiece and icona, furthermore, helps to challenge the art historical vocabulary of our modern discipline.

1. Post-Tridentine Visitations

Scholarship on the Council of Trent has long been entrenched in the binary opposition of theory and implementation, cleaving the history of reform into a story of decrees and doctrine on the one hand and enforcements, negotiations, and messy realities on the other (

Alberigo 1958). Wietse

de Boer’s (

2001) classic text,

The Conquest of the Soul, bakes this dualism into its very structure. The book examines the impact of one important Catholic reformer, the cardinal-archbishop Carlo Borromeo (1538–1584), and his attempt to transform his diocese of Milan into a “laboratory of the Counter-Reformation” in the second half of the sixteenth century (

de Boer 2001, p. ix). de Boer achieves this by splitting his book into two halves, one that addresses the ideal prescriptions of Borromean reform and the other, the realities of its implementation. In the discipline of art history, scholars similarly have emphasized the gaps between the council’s standardized statement on images and the rich variety of actual artworks produced at the time (

Locker 2018). This rift between decree and application, ideal and reality, theory and practice was acknowledged after the close of the Council of Trent when, in 1564, Pope Pius IV instituted the Congregation of the Council, tasked with overseeing the implementation of the conciliar decrees (

La Sacra Congregazione 1964;

Black 2004, pp. 43–48;

Meloni 2018). Reform-minded bishops such as Borromeo and Bologna’s Gabriele Paleotti (1522–1597), both also cardinals in the congregation, held local councils and synods aimed at drafting church policies in the spirit of conciliar reform (

Prodi 1964).

Visitations and inspections performed by a bishop or his vicar to assess the spiritual and material health of a diocese acted as powerful tools in the project of reform. There were pushes to reinvigorate this traditional practice before the Council of Trent, as with Bishop Pietro Barozzi in Padua (

Gios 1977) or Gian Matteo Giberti in Verona (

Prosperi 1969), to name two prominent examples. The post-Tridentine period, however, saw an increase in visitations on a new scale (

Burke 1987, pp. 42–44;

Nubola 1993,

1996). The Tridentine decrees instructed bishops to inspect the churches in their diocese on at least a biannual basis, which was no minor undertaking (

Schroeder 1960, p. 193). The visitor’s inquiry could be highly detailed, involving questions about everything from clerical qualifications to confession rates to inventory lists and church furnishings (

Turchini 1990). This led to a massive increase in workload, especially in the diocese of Milan (

Palestra 1971;

Buzzi 1996), where Borromeo was said to have thrown the diocese of Milan into a state of “continual and perpetual” visitation (

Giussano 1610, p. 86).

1The decades after Trent also witnessed a rise in apostolic visitations, in which a diocese would be visited by an external agent on the basis of papal authority (

Fiorani 1980;

Mazzone 2003). In addition to the pastoral visitations completed within Rome by the popes or their vicars, the pope had the authority to send agents to other regions, such as Turin, Milan, or Brescia. Apostolic visitors could circumvent some of the limits to episcopal jurisdiction, and their decrees were less easily contested. Papal official Gerolamo Ragazzoni was sent into Borromeo’s home diocese of Milan in 1575 as an apostolic visitor in part because of heated jurisdictional conflicts between the archbishop and civic authorities (

Ghezzi 1982–1983). Apostolic visitations became formalized in the Roman curia: Pope Clement VIII instituted a commission of cardinals to oversee the practice in 1592, which would become the Congregation for Apostolic Visitation in 1624 (

Beggiao 1978, p. 42;

Pagano 1980, p. 319).

The grandeur of the visitations grew alongside their importance to Tridentine reform, providing increasingly detailed records of the encounters between inspector and image in the churches of Rome. The earlier post-Tridentine visitation records differ greatly from those just a few decades later. A set of visitation records from Rome dating from 1564 to 1566, for example, are written in Italian in the first person (

Pagano 1980, p. 329).

2 They contain colorful complaints about scandalously ignorant priests, missing relics, and a visitor who, at times, cannot locate anyone to interview. The descriptions of the material contents of each church are fairly minimal, restricted to certain notable details or missing elements. When Clement VIII conducted the first papal visitations in Rome after Trent from 1592 to 1596, those findings were neatly recorded in Latin and later bound into a large, handsome volume.

3 This text, unlike its predecessor, contains careful, thorough descriptions of each altar’s furnishings.

The increasingly expansive format allowed more references to images, providing an opportunity to explore how the visitors implemented image reform. To focus on implementation is not to dispense with nuance. As

de Boer (

2001, pp. 172–74) has explored in the Milanese context, even when post-Tridentine ecclesiastical policy operated as a form of social discipline, it was not enacted in a straightforwardly top-down fashion, contending as it did with local realities and complex agencies. The visitor might be more accurately described as a mediator between the imagined poles of theory and implementation, as they brought their normative texts into the real spaces of churches and the Renaissance frescoes, new altarpieces, and faded miraculous images contained within.

2. Image Directives

Post-Tridentine visitors made recommendations regarding images, but they were not as draconian as one might expect, given how post-Tridentine clerics promised harsh penalties for errant artists or the bishops who failed to monitor them. The final session of the Council of Trent stipulated that all new images were subject to the approval of the bishop (

Schroeder 1960, p. 217), a requirement that was reiterated in the 1565 First Provincial Council of Milan (

Acta 1599, p. 4). This insistence on ecclesiastical oversight is echoed in a 1593 edict composed by Cardinal Girolamo Rusticucci, the Roman vicar who was then assisting Clement VIII in his pastoral visitations (transcribed in

Beggiao 1978, p. 106). Rusticucci’s sternly worded text threatens fines and imprisonment to any artist who decorated an ecclesiastical space without first obtaining the proper license. Laws such as these posit artist against censor, mirroring the tension between artistic freedom and religious decorum that one finds in post-Tridentine artistic treatises such as those of Borghini or Comanini. These ideas could have impacted artists’ stylistic and iconographical decisions on an individual level, as, for example, Marcia

Hall (

2011) has argued. The visitation records, however, show an overriding concern for the physical condition of images rather than imposing strictures on artistic freedom.

The Vatican visitation records do contain some examples of what we might more properly call censorship, including Clement’s Roman visitations in the 1590s (

Beggiao 1978;

Zuccari 1984, pp. 9–13). Opher Mansour, in his illuminating essay on Clement’s directives, counts 14 acts of censorship that dealt with “artistic expression” (

Mansour 2013, p. 138). Multiple complaints focused on the depiction of nudity, echoing not only the injunctions against lasciviousness in the decrees of the Council of Trent (

Schroeder 1960, p. 216) but also the famous criticisms surrounding Michelangelo’s Sistine

Last Judgment (

Schlitt 2005;

O’Malley 2012). Lasciviousness had become a central concept in art theory (

Lingo 2013), but for the visitor, it was typically resolved with minor amendments. Clement’s call to censor the nude allegorical figures on the funerary monument of Paul III in St. Peter’s (

Mansour 2013, pp. 142–43) was more significant, but most other complaints were marginal. Clement criticized the nudity of the carved putti adorning a ciborium in Santa Maria Maggiore, for example, as well as an indecent Mary Magdalene decorating a reliquary cabinet (

Mansour 2013, pp. 141–42).

4 Perino del Vaga’s fresco of Eve in S. Marcello al Corso was fixed simply by elongating her hair so that it covered her pubic area (

Mansour 2013, p. 42;

Beggiao 1978, p. 72).

5 Even when the alleged nudity was near an altar, as with one example of a nude woman brought up during Pope Urban VIII’s visitations of 1624, it was not remedied with urgency—the same complaint appears in an inspection from 1663.

6Clement took issue with images for other reasons as well. He censured an image showing the contested miracle of Pope Leo I, who became aroused when a woman kissed his hand and therefore cut the hand off, only to have it restored by divine grace (

Mansour 2013, pp. 149–50).

7 Clement objected to profane elements, including grotesque ornamental designs and, at least in one case, an allegorical depiction of Prudence with attributes of the pagan goddess Minerva (

Mansour 2013, pp. 151–52;

Beggiao 1978, p. 72).

8 As Mansour describes such commands were not always carried out consistently or immediately. While Clement disapproved of some grotesque ornamentation, following clerical authors such as Gabriele

Paleotti (

1582, ff. 222r–41v), other examples were passed over without comment (

Mansour 2013, p. 152).

9 It is unclear if the figure of Minerva was ever changed into a saint, as Clement had requested. Profane elements were often limited to marginal imagery, as when an apostolic visitor to Milan in 1576 critiqued a liturgical dish with some sort of gilded decoration of a profane nature.

10 Rarely was the crime so egregious as that described in a 1580 letter of Borromeo, who angrily reported a painting of “two profane women” posted beneath an altar of a rural church in Castrezzato.

11The vast majority of image directives are related to their physical condition. Dirt and decomposition were far more common culprits of indecency than lustful figures or secular intrusions. Angelo Peruzzi, Bishop of Sarsina and apostolic visitor, inspected S. Maurizio in Turin in 1584 and found the side altars in a “most indecent” state, while one of the altarpieces was “completely disintegrated”.

12 Ragazzoni, charged with inspecting Milan’s churches in 1576, called for several artworks to be renewed, including the altarpieces over the high altar in the church of S. Salvatore in Xenodochio and in S. Michele in Cantù.

13 Clement VIII’s visitations in the 1590s, too, found many Roman images in a state of disrepair. Murals in Santa Maria in Aracoeli, he determined, were corroded and needed to be restored.

14 The colors of an image of the Virgin Mary over one of the former altars in Santa Maria Maggiore needed to be “newly brightened up”.

15 The Roman inspections under Urban VIII found many similar issues. During the 1625 visitation to the church of S. Maria ad Martyres at the Pantheon, the visitor drew up a list of decrees amounting to a conservation report, noting images that were variably destroyed by humidity, torn, and generally needing renovation.

16 Mosaics in the church of St. Peter’s also needed renovation, to name another example of many.

17Comments regarding the propriety of an artwork’s placement were also common. The visitations contain multiple references to images that had been moved inside from an exterior location, an act that also stemmed in part from a desire for material decorum. A visitor to S. Benedetto della Regola in Rome in the 1560s, for example, mentions that the church’s popular devotional image of the Virgin Mary had been rescued from the “sordid” conditions of its former location.

18 The same visit mentions two other images transferred into church interiors “for greater honor”.

19 Ragazzoni in Milan noted the presence of another Marian image in S. Simpliciano, whose altar was too close to the door and needed to be moved to a different altar or at least more honorably protected.

20This same concern for decorously conserved images led visitors to recommend that certain works be concealed by a curtain or covering, typically a sign of the work’s special devotional status. Ragazzoni ordered that the miraculous fresco in S. Maria dei Miracoli in Milan be covered, while a visitor in Rome in the 1620s praised a sculpted wooden crucifix that was properly conserved beneath a silk veil.

21 Mansour discusses a related case during the 1593 inspection of S. Maria della Consolazione, in which a crucifix needed to be covered or transferred into the sacristy (

Mansour 2013, p. 142).

22The dignity of the physical object was vital to the post-Tridentine visitor’s notion of artistic decorum, though it factored little in treatises on art theory such as those of Borghini or Comanini. We should not dismiss the visitor’s concerns, which communicate much about their conception of sacred images. In his essay on Clement VIII’s visitations, Mansour argues that the visitation is “significant not only for its concrete effects but for its discursive ones” (

Mansour 2013, p. 139). Peter Burke makes a related point in his historical examination of visitations in early modern Italy, arguing that these documents can reveal much about cultural expectations (

Burke 1987, p. 41). We can heed these calls, examining the definition of sacred imagery that emerges from these documents, one defined by its role in the functional ritual space of the church interior.

3. Functions and Definitions

This attention to an artwork’s material decorum echoes a more general treatment of ecclesiastical furnishings in the period. Post-Tridentine reformers emphasized the need for the church interior to be kept in suitable condition. The requirement was not novel by any means, but it was urgently articulated by church reformers such as Borromeo, who published an influential guide on church furnishings. This 1577 text, known as the

Instructiones fabricae et supellectilis ecclesiasticae, delivered rules and recommendations for the proper form and care of everything in church space, from the building’s ground plan to the type of peg used to hold the biretta.

23 The norms in the

Instructiones were of great use to the visitor. Despite its specificity to the diocese of Milan, the

Instructiones was influential well beyond its original purview, providing a model for visitors from Rome to Poland to Spain (

Cattaneo 1983;

Borromeo 2000, pp. vii–ix). The text was also reprinted in the

Acta Ecclesiae Mediolanensis, a compilation of conciliar and synodal decrees, various edicts, and other instructions in the diocese of Milan that were first published in 1582 (

Acta 1599, pp. 561–638). The

Acta brought Borromeo’s rules on church furnishings to an even wider audience—Clement VIII’s delegation had a copy in tow during his Roman visitations (

Mansour 2013, p. 141).

The

Instructiones exhibit a pervasive concern for the physical integrity of the altar’s accoutrements, from liturgical textiles to balustrades to relic niches. Sacred images were part of this same framework—the rules of material decorum applied to altar cloths and altarpieces alike. The

Instructiones recommended that sacred images should be kept away from dampness; likewise, the interior of the Eucharistic tabernacle should be made of wood to control humidity (

Acta 1599, pp. 568, 576). Images in the

Instructiones were part of the altar’s functional equipment and, as such, were subject to the same scrutiny regarding physical upkeep.

The visitor was charged with ensuring each church had its requisite furnishings, including images as well as liturgical objects and texts. The

Instructiones mandates images in several places. It requires that each church display a crucifix in its main chapel (

Acta 1599, p. 567) and that all baptisteries contain an image of John the Baptist (

Acta 1599, p. 577). Confessional booths should display a printed image of the Crucifixion for the penitent to look upon (

Acta 1599, p. 584). The sacristy, too, needed to have a “sacred altarpiece” (

sacra icona) (

Acta 1599, p. 589).

24 Visitors reflect this functional imperative in their recommendations, which more frequently complain about a

lack of imagery than the presence of artistic errors. The apostolic visitations in the diocese of Milan contain many comments about missing altarpieces and bare walls. On a visit to the church of S. Michele in the Lombard village of Mairano, the main altar needed a crucifix and “some decent pictures”.

25 In Ragazzoni’s Milanese inspections, the main altar of S. Giorgio needed a “decent altarpiece,” as did the churches of S. Maria del Cerchio and S. Barnaba in Gratosoglio.

26 All of the other visitations echo this call for additional imagery. The apostolic visitor to Turin in 1584, for example, records dozens of chapels that needed an altarpiece or other ornamentation, as with one chapel in S. Maria della Rotonda that was “missing an altarpiece” and needed its paintings restored.

27 Even the brief Roman inspections from 1564 to 1566 include many requests for images, often when a picture of the chapel’s titular saint was absent.

28 There are instances of similar requests in the Roman visitations conducted under Clement VIII and Urban VIII as well.

29Post-Tridentine visitors checked to ensure that each altar contained an altarpiece. This requirement appears explicitly in a list of general instructions for pastoral visitors published in Milan. The decrees were published in relation to the fifth diocesan synod of Milan in 1578 and were also incorporated into the 1599 edition of the

Acta Ecclesiae Mediolanensis. The document includes a list of items for the visitor to check for when inspecting each altar. The first item on that list is “an altarpiece, or at least some pictures on the walls” (

Acta 1599, p. 461).

30 This requirement is repeated in other documents from the diocese. Ragazzoni copied precisely the same phrase into his own apostolic records for Milan, confirming that an altarpiece or wall paintings were required at each altar.

31 A similar checklist can be found in a small handwritten booklet of visitation instructions conserved in the Diocesan Archive in Milan, ordering the visitor to observe “whether the altar has an altarpiece or some decent imagery painted on the walls”.

32Although the post-Tridentine visitor insisted on the presence of an altarpiece at each altar, it was not strictly necessary for the celebration of Mass (

Gardner 1994, pp. 6–11;

Ekserdjian 2021, p. 22). This ambiguous functional role has contributed to debates surrounding the origin and definition of the altarpiece in Europe, a history that is surprisingly opaque. Such questions have inspired a large body of research on the altarpiece, running from the turn of the twentieth century (

Burckhardt [1898] 1988;

Braun 1924;

Hager 1962) and, especially from the 1990s onward, continuing with renewed vigor into the present (

Humfrey and Kemp 1990;

Van Os 1988–1990;

Humfrey 1993;

Borsook and Superbi 1994;

Ekserdjian 2021). Much of the literature on the altarpiece stresses its iconographical, ritual, or morphological connection to the celebration of Mass. Scholars have long linked the development of the painted altarpiece in thirteenth-century Italy to changes to Eucharistic ritual following the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215, though others have more recently complicated this association (

Williamson 2004, p. 347;

Ekserdjian 2021, p. 24). The question of the origin of the altarpiece hinges on its definition, a problem with its own difficulties (

Kemp 1990;

Hills 1990). The duty of an altarpiece—if by this we simply intend an image above or behind the altar—was performed by a wide variety of objects called by many different names. Scholars have explored the development of specific altarpiece formats, such as the Netherlandish carved altarpiece (

Woods 1990) or the adoption of the Italian Renaissance

pala in Venice (

Humfrey 1994). Julian Gardner counted nine words for images behind altars that were in use at the turn of the fourteenth century in Italy alone, revealing that terms as well as types can be difficult to pin down (

Gardner 1994, p. 14).

This formal and lexical ambiguity is collapsed in the post-Tridentine visitation records. The era’s expansion of visitations helped to codify a functional definition of the altarpiece and, with it, a certain vocabulary. The 1578 general visitation instructions first published in Milan instruct the visitor to check for an

icona at every altar, a word translated as an altarpiece.

Icona derives from the Greek

eikon, a generic term for an image that is not media-specific (

Wharton 2003, p. 4). It is the root for the Italian

ancona, used to describe an altarpiece (though not exclusively) at least from the fourteenth century into the present (

Gardner 1994, p. 14;

Schmidt 2005, p. 59, 70n123;

Ekserdjian 2021, p. 10). In the Latin visitation records,

icona operates as the Latin translation of the Italian

ancona or as an alternative Italian spelling of the latter. This equivalency is apparent in the 1599 edition of the

Acta Ecclesiae Mediolanensis, which includes some general instructions from Borromeo in vernacular Italian. Here, Borromeo echoes the Latin decrees for visitors in Milan, declaring that every altar should have “some sacred images in sculpture or in painting for the altarpiece (

Ancona), if possible, or at least on the walls” (

Acta 1599, p. 803).

33The word icona is used in many of the apostolic visits in Northern Italy in the 1570s and 1580s, such as those in Turin, Milan, and Brescia, while many of the contemporary Roman documents rely on the more general imago. However, by Urban VIII’s visitations in Rome in the 1620s, as well as subsequent Roman visitations at least through the 1660s, icona is used consistently to identify an image functioning as an altar’s requisite altarpiece. This shift in the terminology of the Roman visitations could perhaps reflect the growing influence of Borromeo’s Milanese legislation, as icona was used often in Northern Italy before it became commonplace in Roman visitations.

The decorum of the altarpiece, the visitor’s

icona, is contingent upon its function. Altarpieces needed to be properly blessed, and furthermore, they were responsible for identifying the dedication of the altar (

Williamson 2004, pp. 355–62;

Ekserdjian 2021, pp. 27–31). These requirements appear already in late medieval canon law, such as in the synodal texts of Bishop William Durand (

c.1230–1296), an important source for Borromeo’s legislative rules (

Gardner 1994). Just as Durand gives instructions for blessing the altar images (

Schmidt 2021, p. 11), so too does the fifth diocesan synod of Milan in 1578 (

Acta 1599, p. 384). In Durand’s liturgical treatise, the

Rationale Divinorum Officiorum, he states that the dedication of an altar must be identified by “an image or a painting or a sculpture or a text” (after translation in

Schmidt 2021, p. 12).

34 The identifying function of an altarpiece was paramount for the post-Tridentine visitor, too, though there is no indication that Durand’s textual marker any longer sufficed.

Visitors recorded many instances in which the altarpiece failed in its functional role. Under Urban VIII, the visitor insisted that the image of the Madonna del Soccorso be moved to the altar of the same name.

35 In the church of S. Lorenzo fuori le mura in Rome, he specified that the canons had two months to remove an image of Carlo Borromeo, who had himself been canonized in 1610 and to replace it with an image of the chapel’s actual titular saints, the Santi Romani.

36 Pope Clement VIII made similar requests in his inspections, as when he required that an image of Mary be removed from the Chapel of St. Nicholas and replaced with an altarpiece depicting Nicholas.

37 The issue of dedications could become incredibly complex, as Louise Rice has shown in her study on the basilica of New St. Peter’s in Rome (

Rice 1997, chp. 5). Lapses in decorum often occurred because of the condition of the location rather than a formal quality inherent to the image.

Altarpieces, long recognized as a functional category (

Burckhardt [1898] 1988), varied immensely in form. The word altarpiece might conjure up an image of a rectangular canvas painting in the mind of the Italian Baroque art historian or a wooden panel for the fifteenth-century specialist—Garzanti Linguistica indeed defines

ancona as a large painted panel (

Garzanti Linguistica 2022, s.v. “ancona”).

38 The visitor’s use of

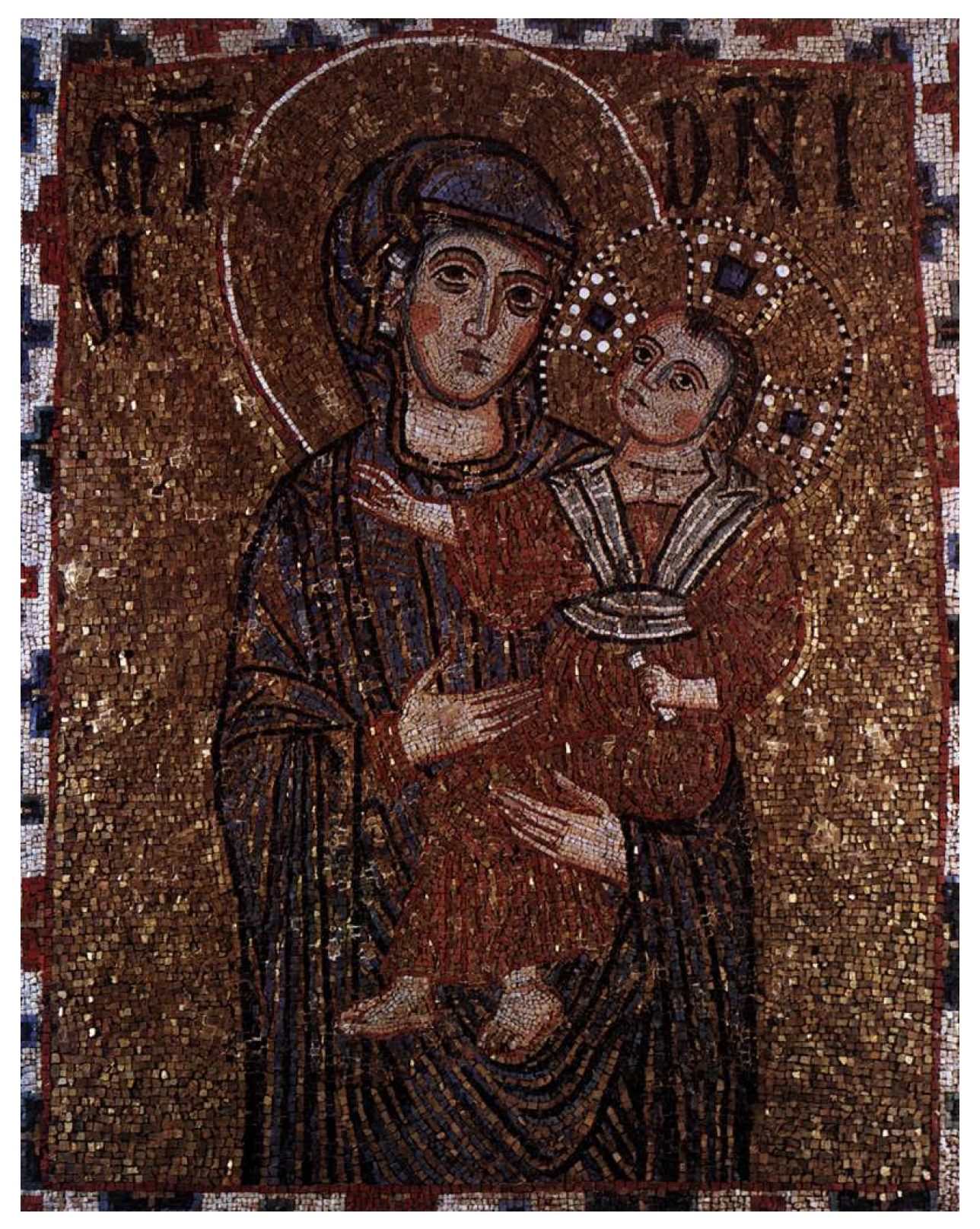

icona recognized no such distinctions. In Urban VIII’s visitations,

icona is applied to Caravaggio’s 1602

Inspiration of St. Matthew in S. Luigi dei Francesci (

Figure 1), Vincenzo de’ Rossi’s 1547 marble sculpture of St. Joseph and the Christ Child in the Pantheon (

Figure 2), and a thirteenth-century Marian mosaic (

Figure 3) in S. Paolo fuori le mura, before which the first followers of Ignatius of Loyola were said to have pledged to join the Society of Jesus in 1541 (

Camerlenghi 2018, p. 191).

39Authorship, age, or miraculous pedigree did not affect an image’s ability to fulfill the role of the altarpiece. The visitor to S. Maria in Aracoeli in 1629 praised the church’s venerated portrait of the Madonna (

Figure 4), noting that it was believed to be by the hand of St. Luke, but he also confirmed that it operated as the requisite altarpiece, or “

pro icona”.

40Similarly, the visitor to Caravaggio’s painting of St. Matthew in the Contarelli Chapel in 1626 recorded that the chapel had the necessary

icona of its dedicatory saint, but he also wrote that it was notably “depicted by the distinguished hand” of Caravaggio.

41 Artistic praise and conservational concerns come together in a visitor’s 1625 records to the church of SS. Martina e Luca, associated with the Roman art academy, the Accademia di San Luca. The visitor duly noted that the altar of St. Luke had an altarpiece (

iconam) of the same saint by the “celebrated hand of the painter Raphael of Urbino,” a work (

Figure 5) whose attribution has since been questioned (

Cellini 1958;

Waźbiński 1985;

Nagel 2011, pp. 77–79;

Libina 2019).

42He then professed concern for the painting’s material decorum, threatened as it was by artists’ constant attempts to copy the much-admired work. While the visitor observed the devotional significance of the Aracoeli Madonna and the artistic fame of Raphael’s painting, he subjected both works to the same rubric of material decorum and ecclesiastical policy. They, like Caravaggio’s canvas, Vincenzo de’ Rossi’s marble sculpture, and the late medieval mosaic in S. Paolo fuori le mura, all met the visitor’s requirements, which collapsed a diversity of images into the functional category of the icona, or altarpiece.

4. Icona and Icons

To bring Raphael into the same interpretive framework as a medieval Marian image is to recall art history’s fraught debate between art and icon, which has been thoughtfully reframed in more recent publications (

Casper 2014;

Nygren 2020). The Madonna of Aracoeli, in fact, interacted with a different Raphael altarpiece in an episode often recounted in post-Tridentine art history. The older image was moved to the high altar of S. Maria in Aracoeli in 1565, replacing Raphael’s 1512

Madonna del Foligno, an act sometimes interpreted as a post-Tridentine preference for cultic images over the cult of the artist (

Ferino-Pagden 1990;

Noreen 2008;

Hall 2011, p. 2). In his oft-cited concluding chapter of

Likeness and Presence, Hans

Belting (

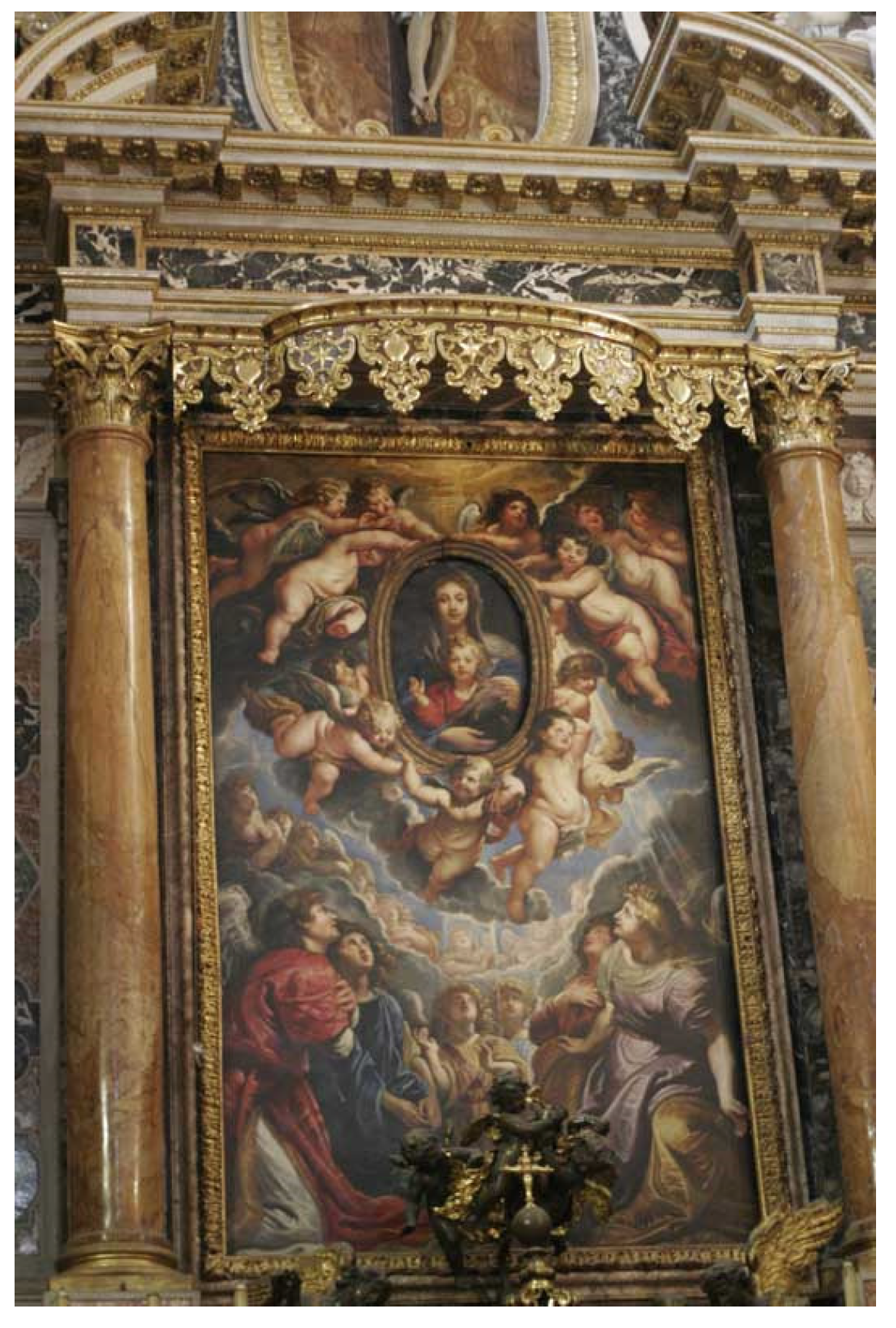

1994) argues for a cleavage of art and cult in the late sixteenth century, culminating in Peter Paul Rubens’s 1608 altarpiece for the Oratorian church of Santa Maria in Vallicella (

Figure 6).

Rubens’s oil painting frames the aging devotional image within, itself hidden by a movable painted copper cover. For Belting, the ensemble visualizes the difference between the “old cult image” and Rubens’s surrounding artistry, between icon and art (

Belting 1994, p. 488).

Rubens completed two versions of the altarpiece (

Noyes 2017). In speaking of his first attempt, Belting distinguishes between the Marian “image relic (

icona)” and the “altarpiece (

quadro)” (

Belting 1994, p. 486).

43 Belting’s translation introduces the visitor’s word for altarpiece, the

icona, into the wrong equation. Documents contemporary to the commission refer to Rubens’s painting as a

quadro, or painting, and its old Marian embedded image as a

sacra immagine, or holy image (

Casper 2021, p. 138;

Stoichita 1997, pp. 69–70). Because

icona best translates as altarpiece, it could apply to the entire palimpsestic work but should certainly not be contrasted with the term altarpiece. Belting’s use of

icona seems inadvertently imbued with the modern idea of the icon as a miraculous cult image, a valence at odds with its early modern usage.

Belting’s terminological slippage points to the complex history of the word icon. It derives from the Greek

eikon, meaning image, likeness, or simile, which figured prominently in the textual traditions of the Byzantine Iconoclastic Controversy (

Barasch 1992, pt. 3;

Wharton 2003, p. 4). As Robert

Maniura (

2003, p. 87) has shown, the icon in modern art historical scholarship typically refers to a “panel painting of a sacred subject from the Orthodox East”. Scholars such as Hans

Belting (

1994) have explored the history of the icon as an influx of Byzantine religious imagery into Western Europe, amounting in fifteenth-century Italy to what Alexander

Nagel (

2011, p. 21) called an “icon craze”. In other moments, however, the modern usage of the icon sheds the Greek connotations of its root to include a broader range of miraculous images, particularly if they are older, Marian, or non-narrative (

Ringbom 1984;

Maniura 2003;

Pon 2015). This latter deployment of “icon” implicitly denotes a less familiar object to the secularized Western reader, ringing true with Annabel Wharton’s accusation that icon, idol, totem, and fetish are words in modern parlance that identify “images of the Other’s divinity” (

Wharton 2003, p. 3). Today, works such as the Madonna of Aracoeli (see

Figure 4) are commonly called icons, a notion that does not directly map onto any term in use in early modern Italy (

Casper 2010, p. 103). Treatises, whether Vasari’s

Lives of the Artists or Comanini’s

Il Figino (2001), or Archbishop Gabriele Paleotti’s

Discorso (1582), tend to rely instead on

immagine, or image (

Casper 2010, p. 103). The Madonna of Aracoeli, an emblematic icon in modern scholarship, would have been regularly referred to as an

immagine.

The visitor’s frequent use of

icona may, as it seems to have done for Belting, implicitly call this modern definition of icon to mind as something with miraculous capabilities or distant origins that can be contrasted with Raphael’s artistry. However, there is no sense that the visitor’s use of

icona would have intimated anything other than a functionally defined altarpiece. Interestingly, however, Paleotti—a post-Tridentine archbishop who conducted visitations of his own—does use the term

icona once in his treatise on images. Paleotti recounts the legendary story of Nicodemus’s portrait of Christ told in an account then attributed to the fourth-century saint Athanasius. Paleotti writes that Nicodemus “formed the icon (

icona), called thus by the Greeks, of our Savior,” suggesting that Paleotti, at least, had the vocabulary to read

icona both as altarpiece and as a Greek holy image (

Paleotti 1582, f. 87v).

44Comanini’s 1591 artistic treatise,

The Figino, provides a more explicit case of lexical multiplicity in its discussion of the Italian

idolo, or idol. Comanini’s educated interlocutors are informed about the word’s etymology: Comanini’s poet Stefano Guazzo explains that his definition of

idolo follows that of its Greek root

eidōlon, used by Plato in the more general sense of an image (

Comanini 2001, p. 17). Later, in a long speech defending Christian image veneration, the priest Ascanio Martinengo expounds upon the text of the Council of Nicaea and concludes by telling Guazzo that his expansive definition of

idolo as an image of any kind “cannot be allowed you in matters of the worship of Christian images,” emphasizing its negative connotation as a depiction of a false god (

Comanini 2001, p. 57).

Idolo operates on (at least) two different registers for Comanini’s sixteenth-century discussants, creating problems for the modern English translators of the treatise (

Comanini 2001, p. xix).

Although the visitor’s use of

icona contains no latent reference to Belting’s icons, the language of the visitation nevertheless provides us with a usefully oblique perspective on the categories of art history. The individuals tasked with implementing Tridentine reform did not deploy a vocabulary of art versus icon or artistic versus miraculous but depended instead on the traditional functional category of the altarpiece. This is not to exile Borghini’s erudite interlocutors from the church interior but rather to conceive of the relationship between Tridentine reform and art as complicated by variable registers of decorum at once. Small moments of overlap suggest future directions in research. We can take the visitor’s concern for the conservational status of Raphael’s altarpiece as seriously as his praise of the artist’s fame. We could contemplate what it might mean that Raphael’s

Madonna del Foligno, after its removal from the high altar of S. Maria in Aracoeli, was installed over the high altar of S. Anna in Foligno, a mismatch in the dedication that surely would have displeased an astute ecclesiastical visitor (

Ekserdjian 2021, p. 29). The visitor’s functional sense of image decorum can help complicate the categories of Borghini or Comanini and the modern art historian alike.