Christians in Jewish Houses: The Testimony of the Inquisition in the Duchy of Modena in the Seventeenth Century

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Inside Jewish Domestic Premises

I have been at many Jewish festivities and do not remember any in particular, but there was one in the house of the Jew Scocco, another in that of Abraham Boaf, and various others which were held at night, and I went to their banquets and ate with them, … and danced unmasked at their balls upon several occasions, and I danced with the Jewish women…I danced with the Jewish women both the wives and the maids, and they took me for partner and I them.25

I could not tell you how many times I ate in the ghetto, but it might have been thirty, forty or a hundred – I do not remember.

3. Escape and Conversion

I know that this girl Laura who lives in Soliera, wanted to become a Christian…One time, I talked with her in the kitchen of her house. She asked me not to say anything to Cesare, her brother, because she did not want him to know. She told me that she had decided to leave his house because her sister-in-law was such bad company.35

If the said Rachel had been willing to come with me as she promised, I would have had her baptized and taken her to wife, and I would have done so willingly… And because her relatives became aware of this they stopped up the doors and balconies and hatched a thousand plots and wanted to injure me.

4. Christian Servants in Jewish Households

5. Inside Christian Domestic Spaces

not wanting to entrust his affairs to just anyone, he [Giovanni Battista] said that he would send his letters in the hand of a young Jew called Leone de Florentini…He [the Jew] came around three times to my house on different occasions, and the Jew brought me letters.62

The Jew was never in my house unless I was there, and not for any other reason except because of my son-in law, as I have already said.63

6. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | On interactions between Jews and Christians, see Ephraim Shoham-Steiner (2016). |

| 2 | Ibid., Stow (2010, p. 32). |

| 3 | Ibid., 4. |

| 4 | Hebrew Bible, Deuteronomy 6: 4–9 and 11: 13–21. |

| 5 | See Pier Cesare Ioly Zorattini (1988, pp. 138–39). See the inventory of the apartment of Simon Luzzatto in the Venetian ghetto in 1592: two bedrooms and a lobby. |

| 6 | See Brian S. Pullan (1971, p. 542). The Modenese situation was similar to that of the Terraferma of Venice, where between 1573 and 1588, the Jews were also granted contracts to serve as moneylenders. In some small towns such as Finale Emilia, Christians were not solely dependent on Jews for pledge-banking but could also turn to the local Monte di Pietà. |

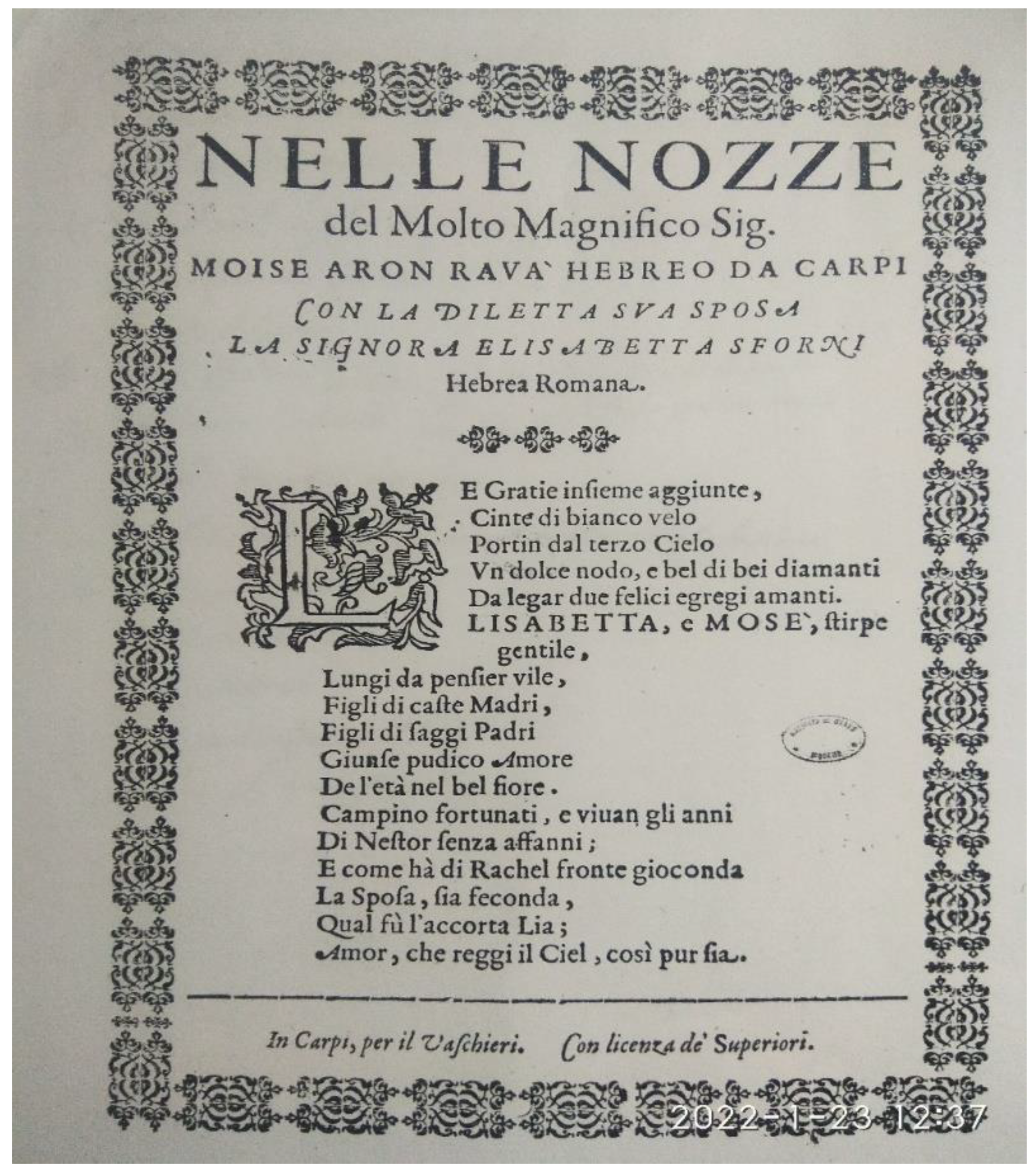

| 7 | On Jewish life at this time in Finale Emilia see Maria Pia Balboni (2005); and on Carpi, Fabbrici, “Alcune coniderazioni.” |

| 8 | See Ariel Toaff (1996, pp. 20–21), who notes that already two centuries earlier, wedding presents were also handed over the morning of the wedding to be exhibited on tables. |

| 9 | Aron-Beller (2011, p. 55). A Modenese inquisitorial edict of 21 June 1603, Contra gli abusi del conversare de Christiani con Hebrei which had forbidden Christians from attending these ceremonies clearly proved ineffective. Concern for this type of activity had already been voiced by Carlo Borromeo, Archbishop of Milan from 1564 to 1584 about Cremonese Jews in 1575 who “without giving it a second thought enter each other’s houses, eat and drink together; Christian children and infants go freely into Jewish homes and converse with their children.” See Corrado Vivanti (1982, p. 356). |

| 10 | Weinstein (2004, p. 442). See also Shlomo Simonsohn (1985), documents 3488, 3642, 3663, 4590 which show parties held in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. |

| 11 | Weinstein (2004, pp. 383–84). An ordinance of the Paduan community of 1580 tried to limit these parties, only permitting them to be held at Purim, on the eve of a circumcision and on the Saturday after the publishing of the marriage bands, kinyian (the celebration of the marriage tenaim—terms) and before and after the wedding. These parties could be held at the domestic space where the bride and groom would live, or another place chosen by them. No dance parties were allowed at other times unless expressly permitted by community leaders. |

| 12 | Ibid., 382. |

| 13 | On these Jewish musical fraternities, see Israel Adler (1966). |

| 14 | See Archivio di Stato di Modena (now abbreviated ASMo.) Fondo dell’Inquisizione (now abbreviated FI) Processi (now abbreviated as Pr) busta 75 folio (now abbreviated as f) 2, 20v. |

| 15 | ASMo. FI Pr busta 50 f 3, 9r. |

| 16 | Ibid., 19r. |

| 17 | ASMo. FI Pr busta 65 f 4. |

| 18 | Ibid. 34r. To deter them, eighteen were sentenced collectively to house arrests and a fine of 10 scuti if they left home, except for going to mass on Sundays in the church closest to their homes. If they attended a Jewish festival in the future, they would be fined another 10 scuti. |

| 19 | ASMo.FI, Pr. busta 65 f4. Giuseppe was only interrogated once at the end of the proceedings and punished with an order that he kneel outside the parochial church in Finale Emilia with a candle in hand and a board around his neck on which was written his crime. |

| 20 | Ibid. See also Balboni (2005, p. 51). |

| 21 | ASMo.FI, Pr. busta 65 f4, 57r. The Jewish suspects justified the presence of Christians by the fact that the gentlemen said they had a license from the rector and governor to dance. Ibid., 14r, 34r and 36v. |

| 22 | Ibid., 37r. |

| 23 | On the trial of Moisè Diena of Sassuolo, see ASMo.FI, Causae Hebreorum busta 245, f 40. |

| 24 | ASMo.FI, Lettere della Sacra Congregazione di Roma 1609–21, busta 253. |

| 25 | Brian Pullan (2003, p. 172). Note that Giorgio Moreto was careful to point out in this part of his evidence that he did not eat meat or fish at Jewish banquets, though evidence came to light that he had eaten roast chicken in the ghetto. |

| 26 | ASMo.FI, Pr. busta 244 f 22. |

| 27 | ASMo. FI, Pr busta 103 f8. See also Katherine Aron-Beller (2013a), co-edited with Christopher F. Black (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 322–351, 330. |

| 28 | ASMo.FI, Pr.busta 168 f1, 25 August 1680. See also Balboni (2005, p. 66). |

| 29 | ASMo.FI, Pr.busta 168 f 1. The vicar was deprived of his office, but the proceedings against him were dropped due to lack of evidence, and he was reinstated a few months later. ASMo.FI, Carteggio con la Congregazione del S. Uffizio di Roma busta 256. Fra Girolamo Moretti was deposed on 12 October 1680 but re-elected on 1 February 1681. |

| 30 | Francesconi (2021, p. 114). Rabbis were concerned at this time that Jewish women would be in contact with Christians from their window balconies. See Weinstein (2004, pp. 158–59, 250–53). |

| 31 | It was common practice for a Christian layman to teach Jewish girls music. See Ibid., 178. |

| 32 | ASMo FI Causae Hebreorum busta 245 f 52 24. Sarza’ father, Benedetto Levi, was given a 50 scudi fine. |

| 33 | ASMo. FI Cause Hebreorum busta 244 f 17. |

| 34 | Ibid., 6r. Ursolina was called to the Inquisition on 2nd April, 1617. She testified that she had asked her one day at the entrance of her house, whether she [i.e., Laura] wanted to become a Christian. Ursolina testified that Laura had said that she wanted to escape her sister-in-law Smiralda, who beat her, and “that she was still afraid that her brother would beat her on different occasions, and for this particular reason Laura said to me that voluntarily she wanted to become a Christian. There was no one else present.” Ibid., 7v, another interchange described by Ursolina in the same interrogation: “Laura said to me in the same house, since no one was present, that her sister-in-law Smiralda, had started shouting at her.”Ibid., 6r. Ursolina was called to the Inquisition on 2nd April 1617. She testified that Laura had asked her: “one day at the entrance of her house, whether she [i.e., Laura] herself wanted to become a Christian. She wanted to escape her sister-in-law Smiralda, who beat her, …. besides she was still afraid that her brother would beat her on different occasions, and for this particular reason Laura said to me that voluntarily she wanted to become a Christian. There was no one else present.” Ibid., 7v, another interchange described by Ursolina in the same interrogation: “Laura said to me in the same house, since no one was present, that her sister-in-law Smiralda, had started shouting at her.” |

| 35 | Ibid. |

| 36 | Ibid., 17r. Cesare was kept in prison and brought in for interrogation on 17 April. He blamed Ursolina for getting involved. |

| 37 | Ibid., Cesare de Norsa was absolved with a warning that if more information was uncovered against him, he would be re-tried. |

| 38 | There is no mention of a written contract between servants and masters in the processi. See Angiolina Arru (1990). |

| 39 | ASMo. FI Causae Hebreorum busta 244 f 26 and ASMo. FI Causae Hebreorum busta 244 f.27. |

| 40 | ASMo. FI Pr. busta 62 f.23. |

| 41 | ASMo FI Pr. busta 83 fol. 16r. A Jewish witness, Abraham Sanguinetti, son of Calman gave more details. “The Christian woman brought the boy inside the synagogue and when she brought him, she stopped for a little, to make sure that the boy had gone to his father. She never said anything, nor relaxed, nor shouted …” |

| 42 | ASMo. FI Causae Hebreorum busta 245 f.43. |

| 43 | In 1619, David, a Jew of Maranello, admitted that his Christian servant often stayed overnight. See ASMo.FI, Causae Hebreorum busta 244 f 22. See also Sarti (2002, p. 133). |

| 44 | See ASMo.FI Pr. busta 75 f 2. Trial against David Diena, Banker of Soliera 1625. Here, Caterina, the wife of Camillo di Gallis, testified that she worked every day in David Diena’s home in Soliera. |

| 45 | ASMo. FI Causae Hebreorum busta 245 f 52. See the testimony of Claudia, daughter of Julia Massali. 3–4. |

| 46 | ASMo.FI Pr. busta 70, f 13. |

| 47 | ASMo. FI Causae Hebreorum busta 245 f 52, 70r. |

| 48 | ASMo. FI Causae Hebreorum busta 247 f.24 (6v). |

| 49 | See ASMo. FI pr. busta 15 f.6. |

| 50 | Ibid. This processo is in the same folio as the one above. |

| 51 | Ibid. (5r). |

| 52 | ASMo. FI Causae Hebreorum busta 245 f 52. See also Katherine Aron-Beller (2013b, pp. 264–65). |

| 53 | ASMo.FI, Pr.busta 53, f 4, 10v-r. |

| 54 | Ibid., 7r. |

| 55 | Ibid. |

| 56 | Ibid., 4r. |

| 57 | See ASMo. FI Causae Hebreorum busta 244 f 25. |

| 58 | ASMo. FI. Causae Hebreorum busta 245 f 44. |

| 59 | Ibid. 41r. Leone’s father Abraam was interrogated and confirmed that he did not know the whereabouts of his son. |

| 60 | Ibid. 6r and 13r Margherita testified: “I know this Jew Leone very well because he has come at times to my house to carry letters to my mother and I have only seen him two times...This Leone was never in my house when I was alone but he always came when my mother was present.” |

| 61 | Ibid. Both women were unable to sign their names at the end of the record of their interrogations—a clear sign of their illiteracy. |

| 62 | Ibid., 34r. |

| 63 | Ibid., 38r. Margharita confirmed that there had been no sexual liason between her and the young Jew: “The truth is as I have told you the first time that I was examined. And if it was true that this Leone, the Jew had some evil practice with me, I would say it openly. It is not good to lie voluntarily in prison and to suffer to defend a Jew.” |

| 64 | Ibid. 46r. |

| 65 | Katherine Aron-Beller (2021). The Cimicelli palazzo’s location was confirmed by Cesare Cimicelli when he gave testimony. See ASMo. FI Causae Hebreorum busta 250 f 33, 315r. In other cities such as Turin and Venice, the Christian tailors’ guilds objected strongly to Jews making new clothes. There is no suggestion that the tailors’ guild in Modena had such strong views. It seems instead that Jews had the opportunity to join almost all the guilds of the city. See Francesconi (2021, pp. 129–30). |

| 66 |

References

- Adler, Israel. 1966. La pratique musicale savante des quelques communautes Juives en Europe aux XVII’ et XVIII’ siecles. Paris: Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Aron-Beller, Katherine. 2011. Jews on Trial: The Papal Inquisition in Modena 1598–1638. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Aron-Beller, Katherine. 2013a. The Jewish Inquisitorial Experience in Seventeenth-Century Modena: A Reflection on Inquisitorial Processi. In The Roman Inquisition: Centre versus Peripheries. Edited by Katherine Aron-Beller and Christopher F. Black. Leiden: Brill, pp. 322–51. [Google Scholar]

- Aron-Beller, Katherine. 2013b. Outside the Ghetto: Jews and Christians in the Duchy of Modena. Journal of Early Modern History 17: 245–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aron-Beller, Katherine. 2021. Sopra l’imputatione del delitto di sodomia con christiano: The proceedings against Lazarro de Norsa (Modena, 1670). In Genesis, XX/1 Mascolinità mediterranee (secoli XII–XVII). Edited by Denise Bezzina and Michaël Gasperoni. Roma: Viella, pp. 65–93. [Google Scholar]

- Arru, Angiolina. 1990. The Distinguishing Features of Domestic Service in Italy. Journal of Family History 15: 547–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balboni, Maria Pia. 2005. Gli Ebrei del Finale Emilia nel Cinquecento e nel Seicento. Florence: Giuntina. [Google Scholar]

- Bonfil, Roberto. 1994. Jewish Life in Renaissance Italy. Oakland: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bryson, Bill. 2010. At Home: A Short History of Private Life. New York: Anchor Books. [Google Scholar]

- Fabbrici, Gabriele. 1999. Alcune considerazioni sulle fonti documentarie e sulla storia della comunità ebraiche di Modena e Carpi (secoli XIV-XVIII). In Le Comunità ebraiche a Modena e a Carpi, dal medioevo all’età contemporanea. Edited by Franco Bonilauri and Vincenza Maugeri. Florence: Giuntina, pp. 51–65. [Google Scholar]

- Francesconi, Federica. 2021. Invisible Enlighteners: The Jewish Merchants of Modena, from the Renaissance to the Emancipation. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ioly Zorattini, Pier Cesare, ed. 1988. Processi del S. Uffizio di Venezia contro ebrei e giudaizzanti. Florence: L.S. Olschiki, vol. VIII, pp. 1587–98. [Google Scholar]

- Jütte, Daniel. 2015. The Strait Gate: Thresholds and Power in Western History. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jütte, Daniel. 2021. Interfaith Encounters between Jews and Christians in the Early Modern period and Beyond. In Friendship in Jewish History, Friendship and Culture. Edited by Lawrence Fine. University Park: Penn State University Press, pp. 185–211. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, Debra. 2019. Living Spaces, Communal Places: Early Modern Jewish Homes and Religious Devotions. In Domestic Devotions in the Early Modern World. Edited by Marco Faini and Alessia Meneghin. Leiden: Brill, pp. 315–33. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews Grieco, Sarah F. 1991. Breastfeeding, Wet Nursing and Infant Mortality in Europe (1400–1800). In Historical Perspectives on Breastfeeding. Edited by Sarah F. Matthews Grieco and Carlo A. Corsini. Florence: UNICEF International Child Development Centre, pp. 39–49. [Google Scholar]

- Pullan, Brian. 1971. Rich and Poor in Renaissance Venice: The Social Institutions of a Catholic State, to 1620. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Pullan, Brian. 2003. The Trial of Giorgio Moreto before the Inquisition in Venice, 1589. In Judicial Tribunals in England and Europe, 1200–1700, The Trials in History. Edited by Maureen Mulholland and Brian Pullan. Manchester: Manchester University Press, vol. 1, pp. 159–81. [Google Scholar]

- Romano, Dennis. 1996. Housecraft and Statecraft: Domestic Service in Renaissance Venice 1400–1600. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sarti, Raffaella. 2002. Europe at Home: Family and Material Culture 1500–1800. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shoham-Steiner, Ephraim, ed. 2016. Intricate Interfaith Networks in the Middle Ages: Quotidian Jewish-Christian Contact. Turnhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Simonsohn, Shlomo. 1985. The Jews in the Duchy of Milan. Jerusalem: The Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Stow, Kenneth R. 2001. Theatre of Acculturation: The Roman Ghetto in the Sixteenth Century. Seattle: University of Washington Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stow, Kenneth R. 2010. Jews and Christians: Two Different Cultures. In Interstizi: Culture ebraico cristiane a Venezia e nei suoi domini dal medioevo all’età moderna. Edited by Uwe Israel, Robert Jütte and Reinhold C. Mueller. Ricerche/Centro tedesco di studi veneziani. Rome: Edizioni di storia e letteratura, vol. 5, pp. 31–46. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton, Peter. 1991. The Italian Renaissance Interior 1400–1600. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. [Google Scholar]

- Toaff, Ariel. 1996. Love, Work and Death: Jewish Life in Medieval Umbria. Translated by Judith Landry. London: The Littman Library of Jewish Civilization. [Google Scholar]

- Vivanti, Corrado. 1982. Storia d’Italia. Annali 4. Intellettuali e potere. Turin: Giulio Einaudi Editore. [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein, Roni. 2004. Marriage Rituals Italian Style: A Historical Anthropological Perspective on Early Modern Italian Jews. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aron-Beller, K. Christians in Jewish Houses: The Testimony of the Inquisition in the Duchy of Modena in the Seventeenth Century. Religions 2023, 14, 614. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14050614

Aron-Beller K. Christians in Jewish Houses: The Testimony of the Inquisition in the Duchy of Modena in the Seventeenth Century. Religions. 2023; 14(5):614. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14050614

Chicago/Turabian StyleAron-Beller, Katherine. 2023. "Christians in Jewish Houses: The Testimony of the Inquisition in the Duchy of Modena in the Seventeenth Century" Religions 14, no. 5: 614. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14050614

APA StyleAron-Beller, K. (2023). Christians in Jewish Houses: The Testimony of the Inquisition in the Duchy of Modena in the Seventeenth Century. Religions, 14(5), 614. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14050614