Abstract

After the death of Masha Amini at the hands of the Iranian Morality Police for not wearing the hijab, in accordance with what they considered appropriate in September 2022, a social media campaign called “Hair for Freedom” was sparked on different platforms, with videos of women cutting their hair in protest over Iranian women’s rights and Amini’s death. This paper analyzes whether this digital feminist movement enacted an interreligious dialogue (IRD). Based on content analysis and topic modeling of the publications retrieved from three major platforms, Twitter, Instagram, and TikTok, the results indicate that this was mainly a Western movement focused on women’s bodies as a political symbol in authoritarian Islamic regimes and has not achieved an IRD since most social media posts reproduced the hashtag #HairForFredom without opening a religious discussion. As observed in other digital movements, conclusions indicate that social media activism does not offer an opportunity to engage in dialogues to enlighten the public sphere. On the contrary, the focus appears to provide users with the opportunity to enhance their reputation by engaging in popular social media campaigns that promote social change.

1. Introduction

On 16 September 2022, Masha Amini, a 22-year-old Iranian, was intercepted by the Morality Police in Tehran for not wearing the hijab properly. That same day, she died under custody due to an unknown situation at the police station. Activists and family members, among other independent voices, accused the police of a brutal approach that caused Amini’s death. Protests erupted during Masha Amini’s funeral in Saqqez (Kurdistan province) and spread across the country in the following days. Despite brutal police repression, after almost a week of uncontrolled riots in several cities, on 24 September, Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi publicly threatened protesters and ordered strong police intervention to contain the uprisings. The foreign press then released riots and protests across 31 Iranian provinces (BBC 2022a).

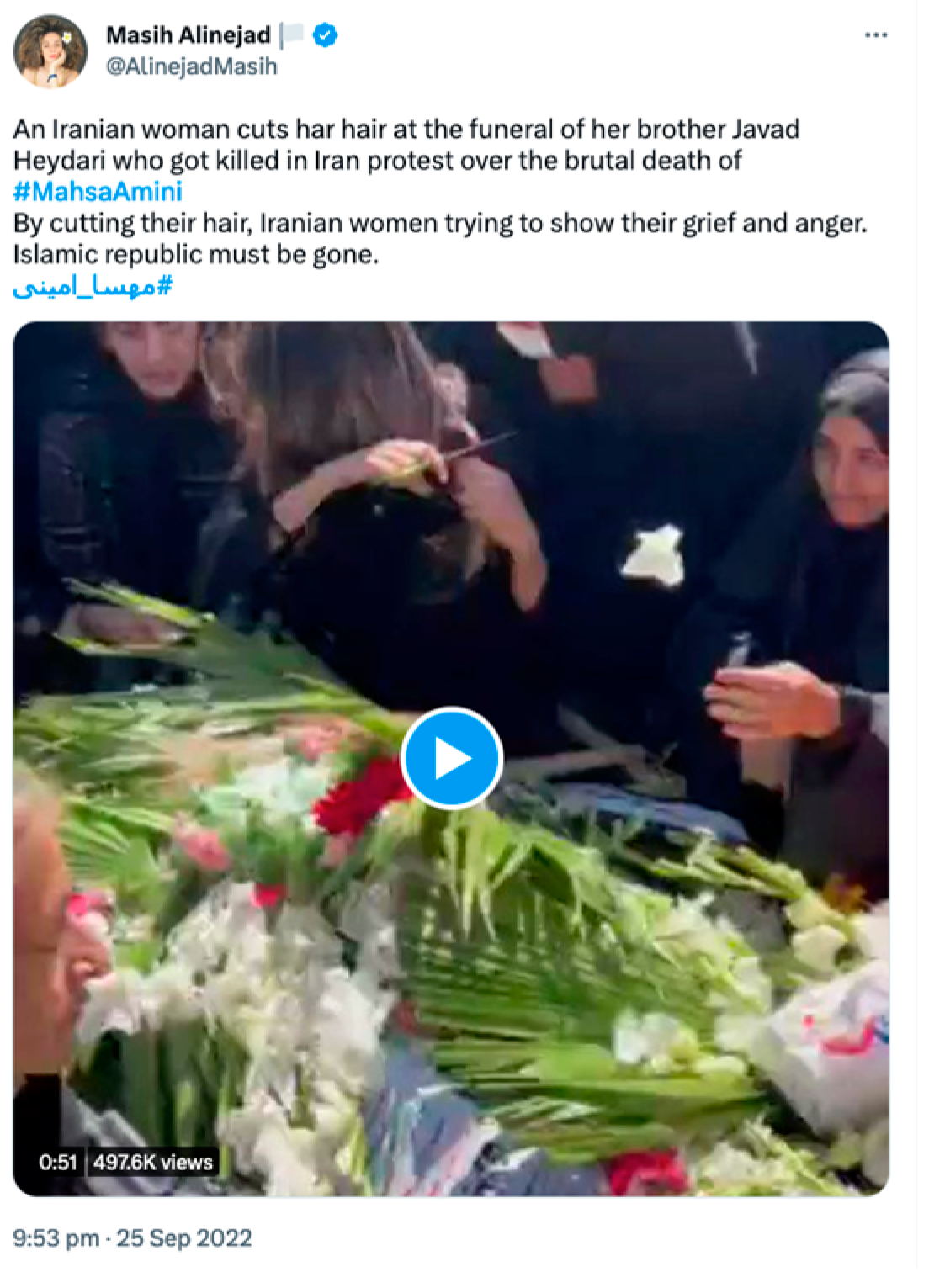

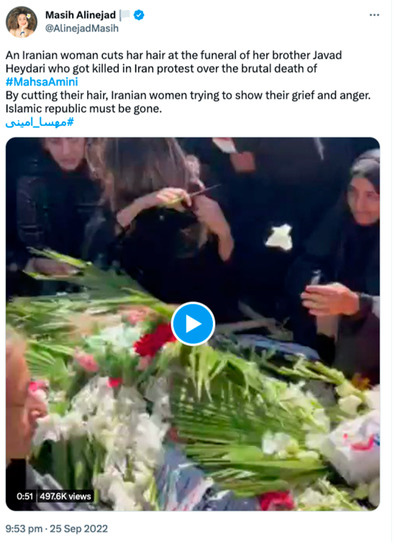

Nevertheless, despite initial police repression, protests increased. Western media outlets claimed that the Iranian regime was facing the most challenging situation in years (BBC 2022a; Tabrizy et al. 2022). As a response, Iranian authorities increased the repression to contain dissidence, and several protesters were incarcerated or died due to the repression. Hence, across social media platforms—most of them blocked in Iran—activist Masih Alinejad, on 25 September 2022, shared a video on her Twitter profile and explained that Iranian women were cutting their hair in a show of support (see Figure 1). The video showed the sister of the deceased Javad Heydari, who was shot by the police during the earliest protests following Masha Amini’s death. After this notice, at the end of September and in the early weeks of October, videos were recorded and shared throughout social media of women (first anonymous women and thereafter celebrities, such as famous French actresses) cutting a piece of their hair in support of women’s freedom in Iran in the wake of Amini’s case.

Figure 1.

Masih Alinejad’s tweet on Iranian women cutting their hair on 25 September 2022. Source: https://twitter.com/AlinejadMasih/status/1574124933470371840 (accessed on 7 January 2023).

This article discusses whether the 2022 social media viral campaign “Hair for Freedom”, in which people cut their hair in support of the Iranian protestors over Masha Amini’s case, has generated an interreligious dialogue (IRD). If so, we intend to map and discuss its type and its implications. If not, we aim to forecast possible explanations for it. To do so, we articulate theories from the IRD framework, digital feminism and religion, and social media activism. The methodology is based on content analysis and the use of automatized topic modeling of posts collected from Twitter, Instagram, and TikTok from 25 September until 15 October 2022, following the #HairForFreedom.

To do so, we considered the following research questions:

- RQ 1.

- What were the most prevalent themes that emerged from “Hair for Freedom’s” social media posts? Did “Hair for Freedom’s” posts focus principally on Islam, women’s rights, or some other topic?

- RQ 2.

- To what degree did religious values or beliefs prompt people to generate social media posts about “Hair for Freedom”?

- RQ 3.

- Did the social media exchange over “Hair for Freedom” prompt intrareligious, interreligious, or suprareligious dialogue?

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Interreligious Dialogue (IRD) on Social Media

IRD is one of those concepts with different layers and nuances depending on the epistemological approach. Körs et al. (2020) explain that very often, under the IRD umbrella, it includes intrareligious dialogue (within religions’ branches), interreligious (between religions), and the dialogue of the religious field or institutions with seculars (suprareligious dialogue). For that, scholars such as Bernhardt (2020) propose distinguishing between interreligious and socioreligious dialogue. The latter comprehend religious groups’ discussions with civil society or nonreligious citizens. In turn, the previous is limited to the dialogue between religious groups.

Although with different views on what IRD is and its extension, both Körs et al. (2020) and Bernhardt (2020) argue for the relevance of promoting religious dialogue across society. IRD is a crucial point in shaping core democratic and pluralistic values and, as Giordan and Lynch (2019) argue, influences and is influenced by sociological categories such as modernity, secularization, deprivatization, social movements, and pluralism. It has global effects on societies. In fact, scholars such as Schmidt-Leukel (2020) have analyzed and argued for its relevance to the public sphere in terms of “understanding, learning, transformation, and cooperation” (259). With the same spirit, the “White Paper on Intercultural Dialogue” released by the Council of Europe (2008) highlights and lists some threats to a non-IRD: stereotyping based on prejudices regarding otherness, the growth of suspicious tensions and anxieties, the uses of minority groups as scapegoats, or fostering intolerance and discriminatory behaviors.

The Council of Europe, among other institutions, frames IRD through the lens of intercultural dialogue. As de Perini and Campagna (2022) explain, IRD has been defined moreover by its application by wealth organizations over the past 20 years. Hence, they conducted a study on the role of intercultural dialogue (ICD) and IRD in an international environment. Based on a longitudinal approach to the position of the West on Islam’s definition of implementing an ICD or IRD agenda, they focused on the meaning of culture and religion as a concept and its appropriation. They criticize the “fuzziness” around IRD as a concept and identify a typology of its uses. According to these authors, there are four different types of IRD agendas that reflect its conceptualization and practice, blended, in which ICD and ICD are framed in equal terms—from discourse to all policymaking and its implementation—without distinctions, explaining religious diversity as part of a whole; disjunct—similar to the previous type—with a disjunctive approach between IRD discourse and its implementation; autonomous, in which IRD and ICD are dealt with as distinctive dimensions; and neglected, in which IRD ignores or does not recognize the religious dimension of ICD.

Melnik (2020) supports the necessity of classifying IRD to understand its goals and impacts on society. However, limiting IRD as a dialogue between religious followers, he takes intentionality as a criterion to discriminate what calls people to engage in an IRD and discriminates four types of IRD, polemical, cognitive, peacemaking, and partnership. According to this author, his classification identifies IRD by forecasting its teleological ideal in “a complex, systematic and interrelated way” (p. 25).

Although with different assumptions, peace or violence prevention has been framed by some scholars as defining IRD. Focusing on peacemaking as the goal of IRD, Petrov and Pleșa (2021), for example, reinforce the argument to understand IRD and socioreligious dialogue as different approaches but with similarities to allow different traditions, cultures, and repertoires to establish a common ground on what can unite people and prevent violence or terrorist acts based on religious beliefs. Noh (2021), in turn, also sees IRD as a key element in forecasting worldwide peace.

Reflections on Islam and Christianity, using violence and peace to conceptualize IRD, emerged in the literature. Lafrarchi (2021), addressing the differences between intra and IRD, argues for their importance in preventing extremism and radicalization of youth. From a theological point of view, Khan et al. (2020) uphold the profound roots of Islam’s beliefs as completely harmonic with other religions and, therefore, as being a powerful religion to build an IRD. With a similar aim, but combining social science empirical evidence with a Christian theological thesis, Polak (2020) argues that IRD only happens in different social and political contexts, thus sustaining the belief that it is part of the evangelization mission. Between Christians and Muslims, González (2020) offers a common ground to seed an IRD, forecasting peace and harmony between believers in tune with nonbelievers. To Corpuz (2021), the COVID-19 pandemic has offered IRD an opportunity to underline how a world religion can promote spiritual support to people’s life, disseminating values on the dignity of the human person, the sense of belonging to a community, respect, and solidarity, among other benefits. Finally, regarding theological virtues from a Christian point of view, West (2021) argues that after the COVID-19 pandemic, there is now an opportunity to engage IRD in the digital context.

Both ideas—Corpuz’s argument of world religion and West’s optimism about the digital world being an opportunity—are frequent theses concerning the aim and scope of IRD in recent years. Khamidov (2021) points out that some scholars explain IRD as a forecast for a world religion, and others uphold its definition concerning the differences and singularity of each religion. Revising the role of the Internet, Lelono (2021) states that digital media can increase IRD by showing the diversity of religions or, on the contrary, by contributing to fundamentalism. The latter, in fact, was an object of Klinkhammer’s (2020) analysis concerning how the media presented Islam in Germany after the 9/11 attacks, contributing to an imagined conflict.

Although limited by platforms’ algorithms and their datafication, the Internet and social media represent an opportunity to stretch out IRD. Network society and the self-mass media (Castells 2009) allow a broader and disintermediated conversation with more autonomy from mass media’s frames and gatekeepers. Nevertheless, as Tsuria (2020) argues, based on the study of four cases, the technological affordances of online media, its social and cultural contexts, and the linguistic strategies employed to communicate can be barriers to IRD. She considers that for IRD to happen, it is necessary to deal with these structural elements and to create a space on the Internet for “contemplation and openness”, otherwise, IRD will not occur.

2.2. Digital Feminism and Religion

The blurring of our online and offline lives has increased the spaces in which religions have a presence. Different religious identities and traditions share their activities on various digital platforms, which must be analyzed to understand the potential for generating interreligious encounters and dialogues. The role of the media in conveying religious identities and meanings through digital platforms is not new and is not exclusive to social media (Novak et al. 2022). However, these platforms have the potential to generate and support transnational dialogues and communities.

The digital activism surrounding women’s rights and feminism has become a good example to study the transnational exchanges between different online identities since this movement has significantly increased its presence in the international public sphere over the last decade. These movements have started in various parts of the world, with mostly local implications in some cases, such as #Niunamenos in Iberoamerica (Giraldo-Luque et al. 2018), #Iamafeminist in South Korea (Kim 2017), or #EverydaySexism in the United Kingdom (Eagle 2015), and transnational reach in others, as is the well-known and highly studied case of #MeToo (Leung and Williams 2019; Zarkov and Davis 2018), which has been associated with high-class white women from Hollywood. All these examples of digital or hashtag feminism focus on the stories of individual women to highlight the structural problems of placing feminism in the international public sphere. However, this popularization of digital feminism has produced a commodification of the movement (Banet-Weiser and Portwood-Stacer 2017) and has generated the rise of the “accidental feminism” of women who join these digital campaigns to promote their individual profiles without a clear cause or agenda for gender equality (Maloney 2017).

These new ways of fighting for women’s rights and their transnational scope have produced a new understanding of the movement and put forward new topics and approaches to feminism. For some authors, it has been considered the fourth wave of feminism (Baumgardner 2011; Zimmerman 2017), putting topics such as sexuality, trans rights, or conversations around women’s bodies at the center. The characteristics of digital platforms and the possibility of anonymity facilitate higher freedom of expression for women (Munroe 2013), particularly in regions with low equality or on topics still considered highly problematic or taboo in most societies. Within this wave, intersectionality has been one of the key concepts praised, defining the possibility and importance of displaying and embracing voices far from the dominant traditional profile of more privileged women and including other realities related to race, social class, or sexual orientation (Zimmerman 2017).

One of the elements often under-discussed and under-researched within the framework of intersectionality is religion (Giorgi 2021) and, even less so, religious diversity within the feminist movement. Hegemonic feminism of the Global North has been characterized as being secular and even opposing religion, as it is seen as tampering with gender equality (Giorgi 2021; Mincheva 2021) and being blind to the inequalities within different religions. However, religious women have historically been part of feminism in all parts of the world, including Western countries, refuting the dichotomy of liberated nonreligious women and submissive religious women (Nyhagen 2017; Van den Brandt and Longman 2017).

Muslim women and Islam have been one of the most contested religious groups within feminism, being highly questioned by both the hegemonic transnational feminist movement and the religious groups. From the Western secular, mostly white feminism, Muslim women have been seen as submissive and have often been treated with a maternalistic approach (Mincheva 2021). From the Islamic perspective, feminist Muslim women have often been treated as problematic for making Muslim men the target of criticism and damaging their image outside religious spaces, resulting in Islamophobia (Hirji 2021). In opposition to these two detrimental and disempowering points of view for feminist Muslim women, in recent years, there have been visible movements in Muslim feminism with active and fighting actions for gender equality, such as the conversation around the #MosqueMeToo introduced in February 2018 by the Egyptian-American journalist and gender activist Mona Elthaway.

This social media campaign was a Muslim response to the widespread #MeToo movement, characterized for being mostly Westernized, white, and upper-class. In this specific hashtag, women had the space to explain their personal experiences of harassment in places of worship. Through the analysis of these actions of Muslim women, and particularly the role of Mona Elthaway, Dyliana Mincheva (2021) introduces a new paradigm of Islamic feminism portrayed as “adversarial”. This type of feminism “capitalizes on the anger and, in so doing, becomes epistemologically related to a tradition of angry feminisms in the West associated with, for example, Black feminist thought and more recently, the affective landscape of #MeToo” (Mincheva 2021, pp. 2–3). This vision highlights the invisibility and oppression by both their religious community and the hegemonic transnational feminist movement. However, in the relationship between feminism and Islam, there are still intense debates around the Muslim veil and its meanings for women and gender equality. As mentioned, a woman’s body is one of the main topics of the current fourth wave of feminism, and the veil, as a symbol of religiosity, has been discussed in different ways from being an obligation to emancipatory, but has mostly been portrayed as a symbol of the oppression of Muslim women (Bilge 2010; Bracke and Fadil 2012; Llorent-Bedmar et al. 2023; Rosenberger and Sauer 2012).

Therefore, this paper focuses on a case study that can be framed within these complex discussions of the control of women’s bodies for religious justifications, Muslim feminism, and the dialogue with other non-Muslim women and feminism. The #HairforFreedom movement on social media grouped women of different geographies and religions—considering secularity—to fight for the freedom of Iranian women after the Morality Police killed Masha Amini in September 2022. As mentioned earlier, the main objective of this paper is to know if and how social media facilitates or hinders IRD concerning the protests over Iranian women and the restrictive laws regarding hair as a symbol of religious morality.

3. Methods

3.1. Sample

Social media posts using the #HairforFreedom on different platforms were collected between 25 September and 15 October 2022. This hashtag is an example of the digital conversation generated around the protests of Iranian women and their fight for freedom and equality. In addition, while this hashtag was not the most used, it is related directly to the veil and hair of Muslim women, which are associated with religious control and were symbols that were the focus of the transnational awareness of this movement. Therefore, the data collected offers a corpus of messages and interactions connected, at their origin, to religious symbols.

The posts were collected from Twitter, Instagram, and TikTok, three of the most used social media platforms worldwide. Since online movements go beyond the borders of one specific platform, collecting data from different networks will offer a broad image of online messages and interactions. In addition, the three platforms chosen are the ones where most users tend to have open profiles, a requisite to study the public conversations generated around social issues. Although the entire sample was built on public posts collected according to each platform’s privacy and data policies, the data were anonymized using the collecting tools’ settings to safeguard users’ data protection and guarantee ethical standards.

The data were collected using different software and data mining processes to connect with each platform’s API (application programming interface). In the case of Twitter, the DMI-TCAT toolset was used; for Instagram, the Instaloader package for Python was used to gather the public posts using the hashtag, not including stories due to their volatile nature; lastly, for TikTok, the Firefox extension Zeeschuimer was used. In total, 4438 posts were collected (Table 1). This data collection contained the posts’ textual, visual, and metadata information, including the text, images, the language of the post, number of likes, views, comments, or retweets, according to each platform’s affordances.

Table 1.

Sample description.

3.2. Data Analysis

A manual content analysis and topic modeling were implemented to search for answers to the main objective and the different research questions set. In implementing both techniques, due to the existence of posts in many different languages, all messages were translated into English, the language initially with the most posts, to be able to codify the sample manually and automatically. Posts were translated using the Google Translate formula within the spreadsheet offered in Google Drive. English was used as the translation language given that it is more developed and reliable. Although the automated translation may include some errors, it does not alter the results significantly due to the volume of the sample. Hence, topic modeling was first used to group the posts of the three social networks into different clusters according to the topic of their textual messages to determine the main discourses related to the hashtag (RQ1). This computational text analysis technique uses algorithms to inductively identify sets of words that often appear together in a textual corpus. In this case, the Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) algorithm was implemented, being the most used unsupervised topic modeling in social sciences (Arcila-Calderón et al. 2021). The use of topic modeling allowed for a more efficient and scalable analysis of the large textual dataset, enabling the researchers to identify patterns and trends that would have been difficult to uncover using traditional manual methods. However, once this technique had been applied, the results were manually reviewed to describe the different topics encountered and to verify the applicability of these topics based on the textual information in the posts based on videos, particularly on TikTok. In this case, posts were manually codified into another prominent topic if needed. Secondly, content analysis of the visual and textual information of posts was used to identify if users disclosed their religious beliefs in their messages posted with the #HairforFreedom (RQ2), taking into consideration references to their religious practices and general beliefs (such as allusions to praying, mentioning of past experiences related to their religion, or visual religious references). In addition, the metadata information downloaded regarding the user’s interaction (e.g., the number of likes or comments) was processed using descriptive statistics with R (RQ3).

4. Findings

After applying the unsupervised topic modeling and taking into consideration the level of coherence to value the similarity among the words for each topic (Stevens et al. 2012) to use a more accurate and adequate model, the posts using the #HairforFreedom can be divided into three main topics showcasing the discourses on Twitter, Instagram, and TikTok. While most posts were classified into two or all topics, the dominant topic in each post that gave a higher score was considered (Table 2). However, in general terms, our analysis reveals that the hegemonic discourse on all social media supports the protests against the Iranian government and its repression of its citizens.

Table 2.

Topics encountered by automated topic modeling and manual coding.

In the first place, the most common topic around #HairforFreedom is women’s rights and its connection with the veil as a religiously imposed element. This topic was dominant in almost half of the corpus analyzed, showcasing the relevance of discourses of feminism in digital spaces. These texts relate mostly to religion from a political approach, protesting against the interpretation of the Islamic Republic’s regulation of women’s bodies, with “body” being the second most used word within this topic. The presence of the words “veil” and “hijab” also complement this discourse.

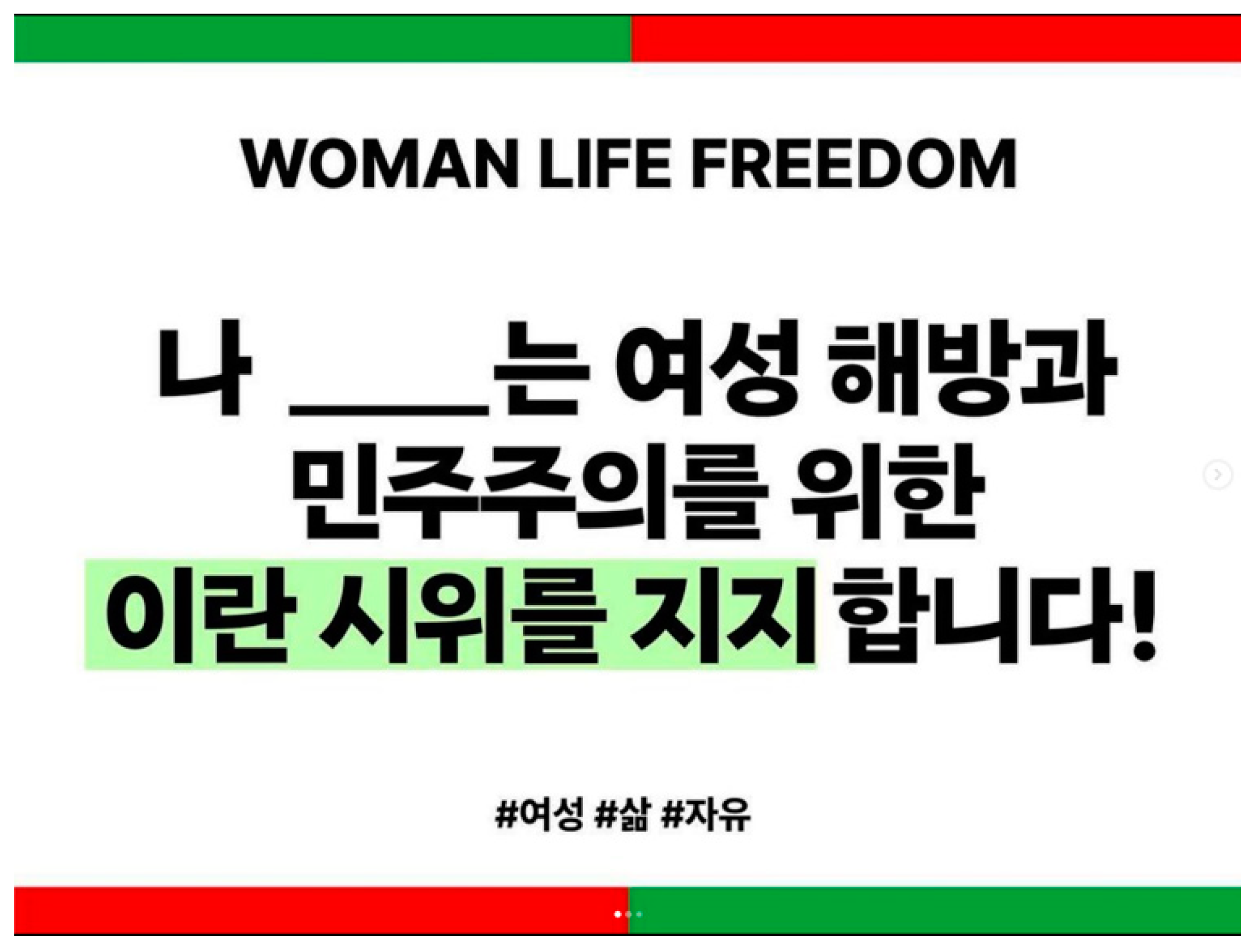

In the second place, there is also a significant number of posts commenting on actions of solidarity with Iranian women, undertaken outside Iran, with the most common being the cutting off of a lock of hair by famous and anonymous users, mainly Western women as the manual content analysis of the visual information shows. In this case, the most shared or mentioned video was made by French actresses cutting off their hair, being commented on in several languages. In addition, regarding this second topic, also relevant are the organized actions undertaken by Korean users employing the same template for their posters (Figure 2), showcasing the transnational reach of this movement. However, the high repetition of the word “solidarity” in the posts makes it clear that these messages are produced from a place of otherness.

Figure 2.

Example of the template diffused by Korean users. In English, it reads: “I work on population integration, is women’s liberation, for the sake of benevolence I support the Iran protests! #women #life #freedom”. Source: https://www.peoplepower21.org/international/1916969 (accessed on 24 February 2023).

Lastly, the third topic encountered, being the least present in the sample, groups the messages commenting on and encouraging the protests undergoing in Iran, but does not relate them to women’s rights. In these cases, the messages mostly focus on street mobilizations, riots in Iran, and worldwide demonstrations to support the Iranian people.

While women’s rights and feminism are explicitly present in the first and second topics encountered, religion was not a main theme in the hegemonic discourses, which took a more political approach. While the aspects commented on were religiously related, the simplification of the conversation on social media about the norms of wearing the veil in a certain way, imposed by the Iranian government, erased most mentions of religion. This coincides with the no disclosure of religious beliefs by most users when posting about #HairforFreedom.

In the few cases mentioning “God” or “prayers” (1.56%), these are made in a generic way and do not specify the religion of the believer (e.g., “God, never allows me to become indolent in the face of the suffering of others”, Instagram post) or complaining about the actions that the Iranian government was undertaking in the name of God. At the same time, in most cases, when “Muslim women” or “Islam” were mentioned in the text (4.13%), these posts were mostly published by non-Muslim users and introduced Islam with the same meaning as the Islamic Republic and the Iranian government. In these cases, posts are written in the third person, reinforcing the idea of otherness. In the only cases where Muslim women commented openly in the first person (0.09%), the plural was used to highlight the unity of Muslim women (e.g., “Muslim sisters from all over the world stand together in protest against Hijab”, tweet written in Hindi). In the case of images portraying women wearing the hijab, again these were posted by mostly non-Muslim users and used highly popular images also portrayed by the traditional media, as in the example in Figure 3 showcasing female Iranian students taking off their veils and confronting an image of the political and religious leader of their country.

Figure 3.

Picture of schoolgirls in Iran during the protests in September 2022. Source: https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2022/oct/09/iran-protests-schoolgirls-videos-khamenei (accessed on 24 February 2023).

The users commenting on the “Hair for Freedom” movement on social media used 32 different languages to express their opinions and beliefs (Table 3). This diversity shows the transnational reach of the campaign analyzed and also the interreligious encounter among these users in the digital public sphere. Within this space, English is the language most used due in part to the hashtag selected for the analysis already being in this language. In this sense, the main transnational campaigns of hashtag feminism have been initiated through an English hashtag since it is the established language for most international exchanges. However, the difficulties in accessing and posting by Iranian people on these social media platforms must be acknowledged. Recently, Iranian authorities have blocked platforms such as Facebook and Twitter. In addition, during the protests of 2022, access to Instagram and TikTok was also periodically blocked (BBC 2022b). Therefore, people living in Iran and publishing in Persian, being only the sixth most used language, had difficulty making their messages public on social media. However, we can see that on TikTok, which is owned by the Chinese company ByteDance, these posts represented a higher percentage than on the platforms owned by Meta from the USA. Although the data can allow us to make these inferences, it represents a limitation of this paper. Moreover, although circumvention through a VPN is an extensive practice in many authoritarian countries (Price 2015), this discussion of participatory infrastructures and free expression rights extends beyond the scope of this article.

Table 3.

Posts by language.

Regarding the interaction among users and the possibility of generating a meaningful dialogue around women’s rights, the veil, and religion, the results show a low level of interaction, considering likes and comments, two affordances present in the three social media platforms analyzed (Table 4). Furthermore, the study found that most interactions were superficial, with users simply liking content without engaging in any conversation. It can also be observed that visual platforms, Instagram and TikTok, foster a slightly higher conversation level than Twitter, particularly for the posts grouped under the women’s rights and veil topic and, in second place, posts about solidarity, including references to actresses and influencers. In the case of comments, our analysis shows that most are messages in the same language, offering support for the main idea but without initiating any exchanges of ideas. Instead, users seem to be isolated within their own social media bubbles, leading to a lack of diversity of perspectives and not allowing an IRD, despite participating in the same conversation around a specific hashtag. Though it is not a component of this paper’s RQ, the superficiality of these interactions can be seen as being similar to the findings from other digital hashtags activism, such as #MeToo (Leung and Williams 2019) or #Niunamenos (Giraldo-Luque et al. 2018), in which political engagement for reputation, visibility, and social media likes prevail over discursive interaction.

Table 4.

Average of interactions by topic and social media platform.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Social media platforms offer a wide range of spaces for conversation. In a certain way, the topic of “Hair for Freedom” emulates previous hashtag feminist actions, such as #MeToo, commodifying protests and spreading the engagement of celebrities, most of them white and Occidental women, as discussed in another context by Banet-Weiser and Portwood-Stacer (2017). It also has provided the “accidental feminist” (Maloney 2017), namely those who engaged in the digital campaign and promoted their own profile without a clear agenda for gender equality. This Global North feminist approach is secular (Nyhagen 2017) and did not result in an IRD.

For that, RQ1, RQ2, and RQ3 should be considered altogether. West (2021) argued that the digital context represents an opportunity for IRD. However, users in the sample analyzed did not disclose religious beliefs, values, or other related concepts but expressed a political and secular view that dominated the messages and interactions. Hence, there is no need to specify if a socioreligious dialogue has taken place, an IRD, or its conceptual variations between religious followers or believers and nonbelievers. Nevertheless, considering that the main focus was women’s rights, politically framed by Occidental and secular perspectives on the hijab, bringing an interculturality dialogue to determine an IRD, as presented by de Perini and Campagna (2022), seems important.

Like other hashtag activism campaigns, “Hair for Freedom” went viral across the globe. Masha Amini’s case was one among various protests. The support of celebrities and the powerful image of women cutting their hair in videos opened a space to establish a dialogue on women’s rights in Iran. In this context, however, Islam and the religious edges of the case were put aside and, again, an opportunity for an open and deep IRD was lost.

On analyzing the sample, we cannot make inferences about people’s or celebrities’ authenticity when engaging with the hashtag and the aim or reasons for their support. Nevertheless, the subject and its powerful virality could have been an open topic to start or engage in an IRD. For that reason, we considered it an opportunity missed. People did not comment on or interact with their own religious beliefs or others’ faith. The conversation pivoted in line with the fourth wave of feminism, centering on women’s bodies (hijab and hair) as a political issue. Not only do social media affordances and cultural or political contexts represent a barrier to IRD (Tsuria 2020), but the constituency of a hegemonic flow of opinion oversimplifying and assembling mimetic Islam and the Iranian authoritarian regime has generated a spiral of silence, making an IRD incapable.

As a limitation of the study, the use of a single hashtag, while common in similar studies, makes the analysis of the presence of IRD less accurate and prevents the generalization of the results. Furthermore, the ban on some social media platforms in Iran and other geographically, culturally, and religiously similar regions predisposes the sample to include fewer voices from these regions. Therefore, further studies should continue to analyze how Islam and women’s rights are discussed and negotiated within social media, taking into consideration a variety of hashtags and emphasizing the perspective of Muslim women.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.N. and L.P.-N.; methodology, C.N. and L.P.-N.; software, C.N.; validation, C.N.; formal analysis, C.N.; data curation, C.N.; writing—original draft preparation, C.N. and L.P.-N.; writing—review and editing, C.N. and L.P.-N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data set created by the authors is available under request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Arcila-Calderón, Carlos, David Blanco-Herrero, Maximiliano Frías-Vázquez, and Francisco Seoane-Pérez. 2021. Refugees welcome? Online hate speech and sentiments in Twitter in Spain during the reception of the boat Aquarius. Sustainability 13: 2728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banet-Weiser, Sarah, and Laura Portwood-Stacer. 2017. The traffic in feminism: An introduction to the commentary and criticism on popular feminism. Feminist Media Studies 17: 884–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgardner, Jennifer. 2011. F ’em!: Goo Goo, Gaga, and Some Thoughts on Balls. Berkeley: Seal Press. [Google Scholar]

- BBC. 2022a. Iran Protests: Raisi to ‘Deal Decisively’ with Widespread Unrest. September 24. Available online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-middle-east-63021113 (accessed on 28 February 2023).

- BBC. 2022b. Iran Unrest: What’s Going on with Iran and the Internet? September 24. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-62996100 (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Bernhardt, Reinhold. 2020. Concepts and Practice of Interreligious and Socio-Religious Dialogue. In Religious Diversity and Interreligious Dialogue. Edited by Anna Körs, Wolfram Weisse and Jean-Paul Willaime. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 239–49. [Google Scholar]

- Bilge, Sirma. 2010. Beyond subordination vs. resistance: An intersectional approach to the agency of veiled Muslim women. Journal of Intercultural Studies 31: 9–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracke, Sarah, and Nadil Fadil. 2012. Is the headscarf oppressive or emancipatory? Field notes from the multicultural debate. Religion and Gender 2: 36–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castells, Manuel. 2009. Communication Power. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Corpuz, Jeff Clyde G. 2021. Religions in action: The role of interreligious dialogue in the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Public Health 43: e236–e237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Council of Europe. 2008. White Paper on Intercultural Dialogue: ‘Living Together as Equals in Dignity’. Available online: www.coe.int/dialogue (accessed on 7 January 2023).

- de Perini, Pietro, and Desirée Campagna. 2022. The fuzzy place of interreligious dialogue in the international community’s intercultural dialogue efforts. International Journal of Cultural Policy 28: 400–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagle, Ryan Bowles. 2015. Loitering, lingering, hashtagging: Women reclaiming public space via #BoardtheBus, #StopStreetHarassment, and the #EverydaySexism Project. Feminist Media Studies 15: 350–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordan, Giuseppe, and Andrew P. Lynch. 2019. Interreligious dialogue: From religion to geopolitics. Annual Review of the Sociology of Religion 10: 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi, Alberta. 2021. Religious feminists and the intersectional feminist movements: Insights from a case study. European Journal of Women’s Studies 28: 244–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraldo-Luque, Santiago, Núria Fernández-García, and José-Cristian Pérez-Arce. 2018. La centralidad temática de la movilización #NiUnaMenos en Twitter. El Profesional de la Información 27: 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, Alexander. 2020. In Search of a Common Base for Interreligious Dialogue: Beyond “a Common Word” between Muslims and Christians. Bogotá: Universidad Libre. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirji, Faiza. 2021. Claiming our space: Muslim women, activism, and social media. Islamophobia Studies Journal 6: 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamidov, Evgeny. 2021. At the Grassroots of Interreligious Dialogue Activities. In Talking Dialogue. Edited by Karsten Lehman. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 151–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Issa, Mohammad Elius, Mohd Roslan Mohd Nor, Mohd Yakub Zulkifli Bin Mohd Yusoff, Kamaruzaman Noordin, and Fadillah Mansor. 2020. A critical appraisal of interreligious dialogue in Islam. SAGE Open 10: 215824402097056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Jinsook. 2017. #iamafeminist as the “Mother Tag”: Feminist identification and activism against misogyny on Twitter in South Korea. Feminist Media Studies 17: 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinkhammer, Gritt. 2020. Interreligious dialogue groups and the mass media. Religion 50: 336–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Körs, Anna, Wolfram Weisse, and Jean-Paul Willaime, eds. 2020. Introduction: Religious Diversity and Interreligious Dialogue. In Religious Diversity and Interreligious Dialogue. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafrarchi, Naïma. 2021. Intra- and interreligious dialogue in Flemish (Belgian) secondary education as a tool to prevent radicalisation. Religion 12: 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelono, Martinus Joko. 2021. Internet-mediated interreligious dialogue a study case on @KatolikG’s model of dialogue. Journal of Asian Orientation in Theology 3: 149–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, Rebecca, and Robert Williams. 2019. #MeToo and intersectionality: An examination of the #MeToo movement through the R. Kelly scandal. Journal of Communication Inquiry 43: 349–71. [Google Scholar]

- Llorent-Bedmar, Vicente, Lucía Torres-Zaragoza, and Encarnación Sánchez-Lissen. 2023. The use of religious signs in schools in Germany, France, England and Spain: The Islamic Veil. Religions 14: 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maloney, Abbey Rose. 2017. Influence of the Kardashian–Jenners on fourth wave feminism. Elon Journal of Undergraduate Research in Communications 8: 48–59. [Google Scholar]

- Melnik, Sergey Vladislavovich. 2020. Classification of types of interreligious dialogue. Communicology 8: 25–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mincheva, Dilyana. 2021. #DearSister and #MosqueMeToo: Adversarial Islamic feminism within the Western–Islamic public sphere. Feminist Media Studies, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munroe, Ealasaid. 2013. Feminism: A fourth wave? Political Insight 4: 22–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, Minjung. 2021. Implementing Interreligious Dialogue. In Talking Dialogue. Edited by Karsten Lehman. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 327–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, Cristoph, Miriam Haselbacher, Astrid Mattes, and Katharina Limacher. 2022. Religious “bubbles” in a superdiverse digital landscape? Research with religious youth on Instagram. Religions 13: 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyhagen, Line. 2017. The lived religion approach in the sociology of religion and its implications for secular feminist analyses of religion. Social Compass 64: 495–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrov, George Daniel, and Victor Marius Pleșa. 2021. Interreligious dialogue and socio-religious dialogue in today’s society. Technium Social Sciences Journal 25: 754–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polak, Regina. 2020. Between theological ideals and empirical realities: Complex diversity in interreligious dialogue. Interdisciplinary Journal for Religion and Transformation in Contemporary Society 6: 274–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, Monroe. 2015. Free Expression, Globalism, and the New Strategic Communication. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberger, Sieglinde, and Birgit Sauer, eds. 2012. Politics, Religion and Gender: Framing and Regulating the Veil. Oxford: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt-Leukel, Perry. 2020. The Relevance of Interreligious Dialogue in the Public Sphere. Some Misgivings. In Religious Diversity and Interreligious Dialogue. Edited by Anna Körs, Wolfram Weisse and Jean-Paul Willaime. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 259–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, Keith, Philip Kegelmeyer, David Andrzejewski, and David Buttler. 2012. Exploring topic coherence over many models and many topics. Paper presented at the 2012 Joint Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and Computational Natural Language Learning, Jeju, Korea, July 12–14; Stroudsburg: ACL, pp. 952–61. [Google Scholar]

- Tabrizy, Nilo, Nailah Morgan, and Axel Boada. 2022. Protests Surge in Iran as Crackdown Escalates. New York Times. September 24. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/video/world/middleeast/100000008550828/mahsa-amini-iran-protests.html?playlistId=video/news-clips (accessed on 28 February 2023).

- Tsuria, Ruth. 2020. The space between us: Considering online media for interreligious dialogue. Religion 50: 437–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Brandt, Nella, and Chia Longman. 2017. Working against many grains: Rethinking difference, emancipation and agency in the counter-discourse of an ethnic minority women’s organisation in Belgium. Social Compass 64: 512–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, Christopher. 2021. The future of interreligious dialogue. The Ecumenical Review 73: 714–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarkov, Dubravka, and Kathy Davis. 2018. Ambiguities and dilemmas around #MeToo: #ForHow Long and #WhereTo? European Journal of Women’s Studies 25: 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, Tegan. 2017. #Intersectionality: The fourth wave feminist Twitter community. Atlantis 38: 54–70. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).