Islamophobia and Twitter: The Political Discourse of the Extreme Right in Spain and Its Impact on the Public

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Islamophobia as a Type of Racism

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results: Vox’s Discourse on Islam and Muslims on Twitter

4.1. Activity

4.2. Themes, Topics, and Representations

“Spain is the second country in terms of the number of Jihadists who have been detained (more than 130) according to Europol. Islamist attacks such as those which have taken place in Barcelona, Cambrils, Brussels or Bataclan may reoccur soon if we continue to leave the South Border unprotected.”(18 May 2022. https://onx.la/a2644)

“Mass and uncontrolled immigration from Muslim countries implies a decrease in terms of the safety of women and homosexuals.”(17 February 2022. https://onx.la/e06db)

“In Melilla, 30 MENAS attacked two security guards, while a dangerous Islamist being pursued by Interpol was detained in Ceuta. In Usera, two south Americans and two Maghrebis were detained for an extremely violent attack on a couple who were out walking.”(1 January 2022. https://onx.la/466fe)

“The silence of other parties regarding the Islamization of Catalunya will have very serious consequences for our land. It is twice as dangerous: terrorist attacks and an end to rights and freedoms in our neighbourhoods. We do not want to become Saint-Dennis or Molenbeek.”(4 February 2022. https://onx.la/165fa)

“Tomorrow, before dawn, WE WILL CONQUER GRANADA, said the glorious Queen Isabel. And that’s what happened. Today we celebrate the triumph of our Christian identity and the end of Muslim occupation, with the fall of the Nasrid kingdom. Granada. Where everything began #ConquestOfGranada #ConquestUntouched.”(2 January 2022. https://onx.la/fa3dc)

“The EU has financed a guide to instruct journalists to avoid “gender-based Islamophobia”: “be inclusive”, “avoid mentioning religion”, “remember that women may prefer to wear the hijab” …; making it a guide which imposes one sole discourse.”(27 July 2022. https://onx.la/a903c)

“I’ll fix it for you: an Algerian MENA rapes, robs and beats an 80-year-old woman. Informative terrorism hides the fact that (again) the political caste has condemned Spaniards to live in fear.”(14 February 2022. https://onx.la/0931b)

“Spain is the second European country with the most detained Jihadists. What did VOX demand? For illegal immigration to be declared of National Security interest due to the infiltration of terrorists. The other parties voted against this and neglected the security of Spanish people.”(14 July 2022. https://onx.la/a18ae)

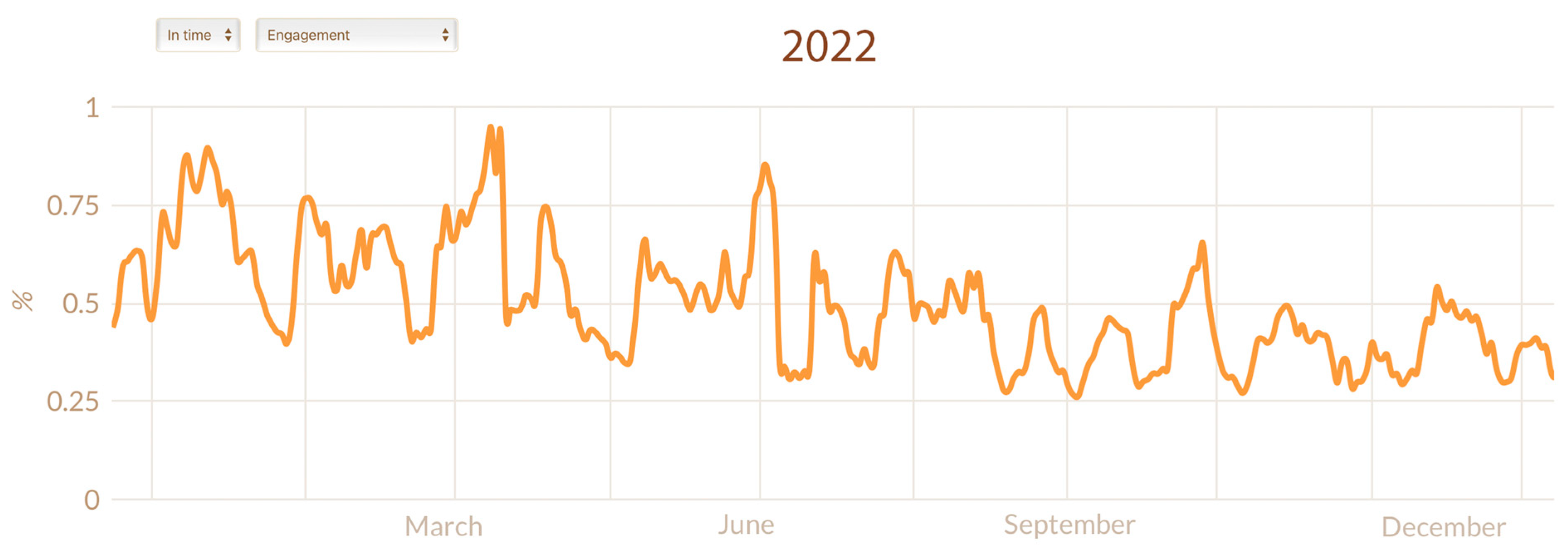

4.3. Incidence of Publications

“It’s not racism, it’s Islamophobia.”(11 April 2022. https://onx.la/059e9)

“Stop manipulating and inventing things. Muslims in Spain, whatever their nationality, don’t do the things the holyweekers of Spanish nationalism are accusing them of. Enough Xenophobia… I’m a Christian and the only people who offend Christ are the cultural Christians.”(11 April 2022. https://onx.la/059e9)

“When will these mobs and other parasites that do nothing but cost us money be deported? No. It’s not racism, it’s reality.”(11 April 2022. https://onx.la/059e9)

“Islam is not compatible with democracy. They are the racists!”(11 April 2022. https://onx.la/059e9)

“Fucking mobs who we’re giving the 5-star treatment, if being racist is not wanting these sons of bitches anywhere near us, wanting them deported so they cannot come back, nor them nor any others, then use all means necessary to exterminate illegal or legal entry of shitbags. I am racist.”(11 April 2022. https://onx.la/059e9)

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Islam: Islamist, Islamists, Islamophobia, Islamophobe, Islamophobes, Islamic, Islamics, Muslim, Muslims, mosque, imam, Quran, jihad, jihadist, jihadists, hiyab, hijab, veil, scarf, niqab, burka, MENA, MENAs and “unaccompanied foreign minors”. The terms used in Spanish were: Islam, islamista, islamistas, islamofobia, islamófobo, islamóbofa, islamófobos/as, islámico, islámica, islámicos, islámicas, musulmán, musulmana, musulmanes, musulmanas, mezquita, imán, Corán, yihad, yihadista, yihadistas, hiyab, hijab, velo, pañuelo, niqab, burka, MENA, MENAs and “menores extranjeros no acompañados”. |

| 2 | Islamisation, Islamism, leftist-Islam, Islamised, Islamising, jihadism, anti-jihadists. The terms used in Spanish were: Islamización, islamismo, islamo-izquierdistas, islamo-izquierdismo, islamizadas, islamizante, yihadismo, antiyihadistas. |

| 3 | There is a diversity of proposals with regard to how to best conceptualize engagement, and that note which variables (likes, comments, retweets) should be considered in order to define the level of engagement. Hollebeek et al. (2014) and Ballesteros Herencia (2019), among others, can be consulted for a review of different metrics and proposals used in social networks to measure it. |

| 4 | The “Conquest of Granada” is controversial and is celebrated in the city on 2nd January each year. The celebration, which has existed since 1495, commemorates the end of the “Christian recapture” and the expulsion of the last Muslim dynasty from the Iberian Peninsula (Rosón 2005). |

| 5 | What happened to Mohamed Said Badaoui is the most controversial and important case of institutional racism and Islamophobia by the State (Babiker 2022) that has occurred in Spain in the present days. His process of deportation began when Mohamed requested Spanish nationality, not prior, which thus reveals that the main reason for his detention and deportation was due to being a person of migrant and Muslim origin, and politically active in the defence of human rights (Garcés 2022). |

| 6 | All the publications analyzed in this article have been translated into English; they were originally in Spanish. The non-textual elements of all the analyzed publications have been removed. |

| 7 | In Spain, a huge majority of unaccompanied foreign minors are from the Maghreb (Fernández 2023). |

| 8 | As has been indicated in the methodology section, in order to calculate the level of engagement, we have taken into account the total sum of likes, comments, and retweets compared to the followers of each account/profile; this has been expressed in percentages. |

| 9 | https://maldita.es/malditobulo/20220412/boicotear-procesion-vendrell-tarragona-musulmanes/, accessed on 1 February 2023. |

| 10 | In this case, the publications were filtered based on the following terms: racist, racists, racism, xenophobe, xenophobes, xenophobia, Islamophobe, Islamophobes, and Islamophobia. |

References

- Acha, Beatriz. 2021. Analizar el auge de la ultraderecha. Surgimiento, ideología y ascenso de los nuevos partidos de ultraderecha. Barcelona: Gedisa. [Google Scholar]

- Acha, Beatriz, Carmen Innerarity Grau, and María Lasanta Palacios. 2020. La influencia política de la derecha radical: Vox y los partidos navarros. Methaodos. Revista de Ciencias Sociales 8: 242–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkerman, Tjitske. 2018. Partidos de extrema derecha y políticas de inmigración en la UE. In Inmigración y asilo, en el centro de la arena política. Anuario CIDOB de la Inmigración 2018. Edited by J. Arango, R. Mahía, D. Moya and E. Sánchez-Montijano. Barcelona: CIDOB, pp. 48–62. [Google Scholar]

- Alcántara, Manuel, and Ana Ruíz. 2017. The framing of Muslims on the Spanish internet. Lodz Papers in Pragmatics 13: 261–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, Chris. 2010. Islamophobia. Farnham: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Arcila Calderón, Carlos, David Blanco-Herrero, and María Belén Valdez Apolo. 2020. Rechazo y discurso de odio en Twitter: Análisis de contenido de los tuits sobre migrantes y refugiados en español. Reis: Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas 172: 21–39. [Google Scholar]

- Awan, Imran. 2016. Islamophobia on social media: A qualitative qnalysis of the Facebook’s walls of hate. International Journal of Cyber Criminology 10: 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Babiker, Sarah. 2022. Racismo. El caso Badaoui agita el debate sobre la islamofobia de Estado. El Salto. October 25. Available online: https://www.elsaltodiario.com/racismo/caso-badaoui-debate-islamofobia-estado (accessed on 31 January 2022).

- Ballesteros Herencia, Carlos Antonio. 2019. El índice de engagement en redes sociales, una medición emergente en la Comunicación académica y organizacional. Razón y palabra 22: 96–124. [Google Scholar]

- Bazian, Hatem. 2018. Islamophobia, “Clash of Civilizations”, and Forging a Post-Cold War Order! Religions 9: 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- bell hooks. 1994. Enseñando a transgredir: La educación como práctica de la libertad. Madrid: Capitan Swing. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatti, Tabetha. 2021. Defining Islamophobia: A Contemporary Understanding of How Expressions of Muslimness Are Targeted. London: The Muslim Council of Britain. [Google Scholar]

- Bustos Martínez, Laura, Pedro Pablo De Santiago Ortega, Miguel Ángel Martínez Miró, and Miriam Sofía Rengifo Hidalgo. 2019. Discursos de odio: Una epidemia que se propaga en la red. Estado de la cuestión sobre el racismo y la xenofobia en las redes sociales. Mediaciones Sociales 18: 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo Fernández, Laura. 2021. El nuevo orden discursivo de la extrema derecha española: De la deshumanización a los bulos en un corpus de tuits de Vox sobre la inmigración. Cultura, Lenguaje y Representación 26: 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmichael, Stokely, and Charles V. Hamilton. 1967. El poder negro: La política de liberación en Estados Unidos. Mexico: S. XXI. [Google Scholar]

- Casals, Xavier. 2019. La normalización de la ultraderecha. Papeles de relaciones ecosociales y cambio global 45: 105–14. [Google Scholar]

- Casals, Xavier. 2020. De Fuerza Nueva a Vox: De la vieja a la nueva ultraderecha española (1975–2019). Ayer 118: 365–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervi, Laura. 2020. Exclusionary populism and Islamophobia: A comparative analysis of Italy and Spain. Religions 11: 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheddadi, Zakariae. 2020. Discurso político de Vox sobre los menores extranjeros no acompañados. Inguruak. Revista Vasca de Sociología y Ciencia Política 69: 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civila, Sabina, Luis M. Romero-Rodríguez, and Amparo Civila. 2020. The Demonization of Islam through social media: A case study of #Stopislam in Instagram. Publications 8: 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criss, Shaniece, Eli K. Michaels, Kamra Solomon, Amani M. Allen, and Thu T. Nguyen. 2021. Twitter Fingers and Echo Chambers: Exploring expressions and experiences of online racism using Twitter. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 8: 1322–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, Angela. 1983. Mujeres, raza y clase. Madrid: Akal. [Google Scholar]

- Ekman, Mattias. 2015. Online Islamophobia and the politics of fear: Manufacturing the green scare. Ethnic and Racial Studies 38: 1986–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Diario. 2022. Expulsado de España Mohamed Said Badaoui, líder de la comunidad musulmana acusado de “radicalismo”. El Diario. November 19. Available online: https://www.eldiario.es/catalunya/expulsado-espana-mohamed-said-lider-islamista-acusado-proyihadismo-captar-menores-tarragona_1_9726226.html (accessed on 31 January 2022).

- Fernández, Rosa. 2023. MENA: Distribución por nacionalidad en España en 2021. Statista. January 13. Available online: https://es.statista.com/estadisticas/1095252/numero-de-mena-por-nacionalidad-en-espana/ (accessed on 31 January 2022).

- Ferreira, Carles. 2019. Vox como representante de la derecha radical en España: Un estudio sobre su ideología. Revista Española De Ciencia Política 51: 73–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forti, Steven. 2021. Extrema derecha 2.0. Qué es y cómo combatirla. Madrid: Siglo XXI. [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes, Cristina, and Carlos Arcila. 2023. Islamophobic hate speech on social networks. An analysis of attitudes to Islamophobia on Twitter. Mediterranean Journal of Communication 14: 225–40. [Google Scholar]

- Garcés, Helios. 2022. Racismo institucional. Lo que nos jugamos con el caso de Mohamed Said Badaoui. CTXT Contexto y Acción. October 24. Available online: https://ctxt.es/es/20221001/Firmas/41102/Helios-F-Garces-racismo-institucional-Mohamed-Said-Badaoui-CIE-ultraderecha-xenofobia.htm (accessed on 31 January 2022).

- Gómez Garcia, Luz. 2019. Diccionario de islam e islamismo. Madrid: Editorial Trotta. [Google Scholar]

- Grosfoguel, Ramón. 2014. Las múltiples caras de la islamofobia. De Raíz Diversa 1: 83–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafez, Farid. 2014. Shifting borders: Islamophobia as common ground for building pan-European right-wing unity. Patterns of Prejudice 48: 479–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollebeek, Linda D., Mark S. Glynn, and Roderick J. Brodie. 2014. Consumer brand engagement in social media: Conceptualization, scale development and validation. Journal of Interactive Marketing 28: 149–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huntington, Samuel P. 1993. The Clash of Civilizations? Foreign Affairs 72: 22–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignazi, Piero. 2003. Extreme Right Parties in Western Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kallis, Aristotle. 2018. The radical right and Islamophobia. In The Oxford Handbook of the Radical Right. Edited by J. Rydgren. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 42–60. [Google Scholar]

- Matamoros, Ariadna. 2017. Platformed racism: The mediation and circulation of an Australian race-based controversy on Twitter, Facebook and YouTube. Information, Communication & Society 20: 930–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modood, Tariq. 2018. Islamophobia: A Form of Cultural Racism. In More Than Words: Approaching a Definition of Islamophobia. Edited by I. Ingham-Barrow. London: MEND, pp. 38–45. [Google Scholar]

- Mudde, Cas. 2019. The Far Right Today. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Olmos-Alcaraz, Antonia. 2018. Otherness, migrations and racism inside virtual social networks: A case of study on Facebook. REMHU- Revista Interdisciplinar da Mobilidade Humana 26: 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmos-Alcaraz, Antonia. 2022. Populism and racism on social networks. An analysis of the Vox discourse on Twitter during the Ceuta ‘migrant crisis’. Catalan Journal of Communication & Cultural Studies 14: 207–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmos-Alcaraz, Antonia. 2023. El discurso político sobre las migraciones en Twitter durante la «crisis migratoria» de Ceuta (2021): De la corrección política al discurso del odio. Cultura, Lenguaje y Representación, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Oso, Laura, Ana María López Sala, and Jacobo Muñoz Comet. 2021. Migration policies, participation and the political construction of migration in Spain. Migraciones 51: 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersson, Katarina. 2020. The discursive denial of racism by Finnish populist radical right politicians accused of anti-Muslim hate-speech. In Nostalgia and Hope: Intersections between Politics of Culture, Welfare, and Migration in Europe. Edited by O. C. Norocel, A. Hellström and M. B. Jørgensen. Cham: Springer, pp. 35–50. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, Miquel. 2021. La irrupción de Vox. In De los neocón a los neonazis. La derecha radical en el estado español. Edited by M. Ramos. Madrid: Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung, pp. 33–124. [Google Scholar]

- Rosón, Javier. 2005. Diferencias culturales y patrimonios compartidos: La “Toma de Granada” y la mezquita mayor del Albayzín. In Patrimonio inmaterial y gestión de la diversidad. Edited by Junta de Andalucía. Sevilla: Instituto Andaluz de Patrimonio Histórico, pp. 98–107. [Google Scholar]

- Runnymede Trust. 1997. Islamophobia: A Challenge for Us All. London: Runnymede Trust. [Google Scholar]

- Runnymede Trust. 2017. Islamophobia: Still a Challenge for Us All. London: Runnymede Trust. [Google Scholar]

- Rydgren, Jens. 2017. Radical right-wing parties in Europe. What’s populism got to do with it? Journal of Language and Politics 16: 485–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauer, Birgit. 2022. Radical right populist debates on female Muslim body-coverings in Austria. Between biopolitics and necropolitics. Identities 29: 447–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosinski, Marcin, and Francisco José Sánchez García. 2022. “Efecto invasión”. Populismo e ideología en el discurso político español sobre los refugiados. El caso de Vox. Discurso y Sociedad 16: 149–72. [Google Scholar]

- Urban, Miguel. 2019. La Emergencia de Vox: Apuntes Para Combatir a la Extrema Derecha Española. Barcelona: Sylone. [Google Scholar]

- Wodak, Ruth. 2021. The Politics of Fear: The Shameless Normalization of Far-Right Discourse. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Wodak, Ruth, and Michał Krzyżanowski. 2017. Right-wing populism in Europe & USA: Contesting politics & discourse beyond “Orbanism” and “Trumpism”. Journal of Language and Politics 16: 471–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wodak, Ruth, and Teun A. Van Dijk. 2000. Racism at the Top: The Investigation, Explanation and Countering of Xenophobia and Racism. Klagenfurt: Drava. [Google Scholar]

| Category: Themes/Topics | Nº Codifications | % |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Aspects regarding security, terrorism and crime | 88 | 40.7 |

| 1.1. Reports, accusations, or suspicions of terrorism | 44 | 50 |

| 1.2. Loss of freedom, security, and rights due to Islam and/or Muslims | 35 | 39.8 |

| 1.3. Crimes committed by Muslims | 9 | 10.2 |

| 2. Cultural aspects | 70 | 32.4 |

| 2.1. Islamization, Islamist threat | 37 | 52.9 |

| 2.2. Islam and/or Muslims are enemies of civilization, the West, and/or Christianity | 13 | 18.6 |

| 2.3. Celebrations of the expulsion of Islam and Muslims from Spain | 9 | 12.9 |

| 2.4. The Muslim woman and the veil | 5 | 7.1 |

| 2.5. Muslims do not adapt to our customs | 4 | 5.7 |

| 2.6. The presence of Islam and/or Muslims in schools | 2 | 2.6 |

| 3. Aspects related to migration | 58 | 26.9 |

| 3.1. Migrant children and MENAS (unaccompanied foreign minors) | 34 | 58.6 |

| 3.2. Illegal immigration | 24 | 41.4 |

| Publication Text/Date | Engagement Variables | Level of Engagement8 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A group of Muslim immigrants tries to bomb a Holy Week procession in El Vendrell. They don’t want to adapt; they don’t want to be a part of anything. May God forgive them, but at home. Not here. Not us. (11 April 2022) | Likes | 10,815 | 52.1% |

| Replies | 882 | ||

| Retweets | 4612 | ||

| Followers | 31,274 | ||

| A group of MENAS brought in via the system brutally attack a 15-year-old lad for trying to protect his sister in Torrelodones. Spaniards are alone. Completely alone. (01 August 2022) | Likes | 7314 | 17.9% |

| Replies | 547 | ||

| Retweets | 4308 | ||

| Followers | 68,002 | ||

| Unbelievable silence from the press, focused on world environment day, in the face of a new case of Christian slaughter, this time in Nigeria, at the hands of Islamists. (06 June 2022) | Likes | 8566 | 1.9% |

| Replies | 526 | ||

| Retweets | 4100 | ||

| Followers | 700,962 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Olmos-Alcaraz, A. Islamophobia and Twitter: The Political Discourse of the Extreme Right in Spain and Its Impact on the Public. Religions 2023, 14, 506. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14040506

Olmos-Alcaraz A. Islamophobia and Twitter: The Political Discourse of the Extreme Right in Spain and Its Impact on the Public. Religions. 2023; 14(4):506. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14040506

Chicago/Turabian StyleOlmos-Alcaraz, Antonia. 2023. "Islamophobia and Twitter: The Political Discourse of the Extreme Right in Spain and Its Impact on the Public" Religions 14, no. 4: 506. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14040506

APA StyleOlmos-Alcaraz, A. (2023). Islamophobia and Twitter: The Political Discourse of the Extreme Right in Spain and Its Impact on the Public. Religions, 14(4), 506. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14040506