Abstract

This study examines the teaching practices of a Korean Ganhwa Seon master to shed light on an effective approach to helping practitioners engage in Seon practice. Few prior studies have analyzed methods of teaching Ganhwa Seon, which is a traditional Buddhist practice for achieving sudden enlightenment. Using the CRISPA framework, which entails connection, risk-taking, imagination, sensory experience, perceptivity, and active engagement, we conducted a single intrinsic case study by observing and interviewing a Korean Ganhwa Seon master during a seven-day retreat program. The participating Ganhwa Seon master incorporated all six CRISPA elements, with an emphasis on active engagement, connection, and risk-taking. In addition, compassion was an essential component of Ganhwa Seon teaching. The findings distinguish the teaching of Korean Ganhwa Seon from the teaching of Chinese Chan, highlight the unique features of instruction in Korean Ganhwa Seon, and provide insight into effective ways to teach Seon practice.

1. Introduction

Contemplative practices such as meditation, mindfulness, and compassion are a significant element of contemporary American society, as demonstrated by MBSR (Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction; Kabat-Zinn 2004), MBCT (Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy; Teasdale et al. 1995), ACT (Acceptance and Commitment Therapy; Hayes et al. 2006), CBCT (Cognitive–Behavioral Compassion Training; Pace et al. 2009), CCT (Compassion Cultivation Training; Jazaieri et al. 2013), MSC (Mindful Self-Compassion; Neff and Germer 2013), and CFT (Compassion-Focused Therapy; Gilbert 2009). These practices have become increasingly popular in a variety of fields including health care services, schools, business, and political organizations. These institutions as well as many corporations have initiated contemplative programs to improve the quality of life in clinics, on campus, in the community, at the workplace, and even at home (Jeong and Park 2010; Min 2017; Ray et al. 2011). Such programs are invariably inspired by one of the many contemplative practices that are part of the major world religions. Meditation, in the popular use of the term, comes from the three Buddhist cultural traditions: Theravada, found throughout Southeast Asia and Sri Lanka; Mahayana, found throughout East Asia; and the Vajrayana, found in Tibet and Mongolia.

Notably, while all three of these traditions have significant psychological and physiological benefits for society, most of the research focuses on the practices of the Theravada and Tibetan masters, especially the metta and vipassanā meditation practices, which were introduced by masters such as His Holiness Dalai Lama, Mahasi Sayadaw, and Ajahn Chah. Moreover, Thich Nhat Hanh’s engaged Buddhism, which is inspired by the Zen teachings of Mahayana Buddhism, also plays a role in popular meditation practices. Because the research concentrates on these traditions, many meditation centers and books focus on them as well. Thus, while Tibetan and/or Theravada meditation practices are widely known, researchers and practitioners have largely overlooked Seon (Jp. Zen, Ch. Chan 禪) practice and masters from East Asian Buddhism. This article addresses this gap in the literature by opening a new line of inquiry into the teaching of Korean Ganhwa Seon practice.

Specifically, using the CRISPA framework, we examine the teaching practices of a Korean Seon Buddhist teacher to better understand how to promote Seon practice (Meng and Uhrmacher 2014). This innovative approach allows us to explore the methods used to teach Seon practice and to identify both the manifest and latent contents of these instructional processes. In particular, the goal is to identify the teaching approaches of Ganhwa Seon masters that spur participants to consistently engage in Seon practice. Before we begin this examination, we offer a summary of the Ganhwa Seon tradition.

2. Ganhwa Seon Buddhism

Since the 1960s and 1970s, meditation practices from various traditions have been introduced in the West; these include Transcendental Meditation from India, Shikantaza from Soto Zen (Just Sitting Meditation), Vajrayana from Tibetan Buddhism, and Samatha and Vipassana meditation from Theravada Buddhism (Sung and Park 2011).

As these different meditation practices became more widespread, researchers began to explore their effects and mechanisms. The studies of Japanese Zen practice published in the West during this time focused on comparing Zen practice and psychological theories and identifying the positive effects of Zen (Berger 1962; Maupin 1962; Smith 1975). This research demonstrated the physiological and/or psychological effects of Zen meditation (Goldman et al. 1979; Malec and Sipprelle 1977; Shapiro and Zifferblatt 1976). Since the 1980s, researchers have focused primarily on mindfulness meditation and have published few studies on Japanese Zen/Chinese Chan practice. Research on Korean Seon, especially the Ganhwa Seon practice, is even more limited (Buswell 1999, 2011).

The Korean term ‘Seon’ refers to the Pali term ‘jhāna,’ meaning a meditative state of concentration and absorption (Nyanatiloka 1988; Rhys Davids and Stede 1993). This state is called ‘Chan’ in China and ‘Zen’ in Japan. In China, ‘jhāna’ was introduced by Bodhidharma, who is believed to be the founder of the Chinese Chan school. After introducing the concept of jhāna, he combined it with Chinese philosophical and cultural elements to form Chan Buddhism. Chan Buddhism was further developed by successive generations of patriarchs including Dazu Huike, Sengcan, Dayi Daoxin, Daman, Hongren, and Huineng.

Chan Buddhism as developed by these patriarchs focuses on the practice of seeing the true nature of being and realizing the inherent nature of Buddha in the mind. Practitioners engage in Chan dialogue in hopes of pointing directly at the true nature of being. This question-and-answer dialogue reveals or breaks down the underlying assumptions and hidden intentions in the disciple’s questions. The format of this dialogue is called Gongan (Jp. Kōan 公案), which refers to a tool used by the ancient patriarchs to reveal the true nature of being (Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism 2006).

In the 12th century, Chan Buddhism split into two orders: the Jodong school (Jp, Soto, Ch, Caodong 曹洞宗) and the Imje school (Jp, Rinzai, Ch, Linji 臨濟宗). The Jodong school emphasizes a practice of ‘silent-penetration’ (黙照禪), while the Imje school emphasizes a practice of ‘hwadu’ (a great question, such as ‘Who am I?’) (Ch, hua tou, Jp, wato 話頭). Practitioners of the latter use the question ‘Who am I?’ as a tool for penetrating the essence of the mind. This practice is called Ganhwa (看話) Seon, which literally means ‘to see the hwadu’. Hwadu spurs practitioners to awaken their true nature as they break it down; it is important that practitioners do not focus on the literal meaning of the question (Buswell 1989). Ganhwa Seon was introduced in Korea in the 13th century and has been preserved as a traditional meditation practice in Korean Buddhist culture for over 800 years.

The main component of Ganhwa Seon practice is making practitioners doubt or be perplexed by holding hwadu. If practitioners do not have doubts about the true nature of being, hwadu cannot lead them to sudden enlightenment. An active hwadu, which creates great doubt in practitioners, is essential for success in Ganhwa Seon practice. By breaking down the hwadu, practitioners can see their true nature. Thus, helping practitioners hold an active hwadu and break it down is the key role of the Ganhwa Seon master.

Ganhwa Seon practice has three core elements: great faith, great determination, and great doubt. These elements refer to an unwavering faith in the practice and the Seon master’s guidance, a strong willingness to obtain enlightenment, and ultimate doubt about the hwadu as embodied in a feeling of constriction or blockage in the throat. The Seon master plays a crucial role in achieving these three elements, because the master can instill in practitioners a conviction that enlightenment can be achieved through hwadu practice. The master should also guide practitioners to hold the hwadu without becoming attached to the meaning of the question and help them continue to hold the hwadu until it is broken down so they can ultimately see the true nature of being.

Due to a lack of understanding of the hwadu practice and the lofty goal of sudden enlightenment, many Ganhwa Seon practitioners have found it difficult to maintain the practice. Furthermore, researchers have had few opportunities to study this practice. However, in recent years, wider dissemination of Ganhwa Seon and a clearer understanding of the practice among the South Korean public has increased interest in and demand for practical research on the practice. Thus, in this study we explore how a contemporary Ganhwa Seon master guides hwadu practice, and we elucidate Ganhwa Seon teaching methods.

3. The CRISPA Framework

We used the CRISPA framework to analyze the teaching features of instruction in Ganhwa Seon. Uhrmacher et al. (Moroye and Uhrmacher 2009; Uhrmacher 2009; Uhrmacher et al. 2013) developed the CRISPA framework by extracting key educational elements from John Dewey’s theory of aesthetics, emphasizing an engaged learning experience (Dewey 1934). The framework entails six elements that educators or instructors can use to lead students to engage in the learning experience. Uhrmacher et al. (2013) argued that instructors should utilize all six dimensions equally to best facilitate students’ learning. The six dimensions are connection, risk-taking, imagination, sensory experience, perceptivity, and active engagement. The dimensions are described in more detail as follows:

- (1)

- ‘Connection’ refers to individuals’ interactions with thoughts, ideas, tools, and/or other materials. Connections can be intellectual, emotional, communicative, or sensorial but are not limited to these four types. Examples include cultivating curiosity; linking to other people with empathy and/or reliability; facilitating communication with people, cultures, and/or time; touching materials; and listening to sounds.

- (2)

- ‘Risk-taking’ refers to learners experiencing something new and breaking away from the standardized approach. Teachers focus on guiding students to take a step forward and overcome their individual difficulties. This element includes helping students explore with curiosity when they face a problem and guiding them to enthusiastically solve the problem. Importantly, risk-taking should involve kind and inclusive instruction and a safe space and time.

- (3)

- ‘Imagination’ refers to individuals learning through mental imagery and creating internal transformations. This element includes combining unexpected elements or thoughts, creating new models, and mimicking or drawing a teacher’s actions in their minds. This process utilizes mental images or simulations.

- (4)

- ‘Sensory experience’ refers to learning and experiencing the world through the sensations of the body. Seeing and reading texts, watching scenery, observing an object, hearing sounds, smelling a fragrance, tasting foods, and feeling tactile sensations are examples of sensory experiences.

- (5)

- ‘Perceptivity’ refers to a deepened level of sensory experience and the emergence of new insights or discoveries as the result of deep contemplation and exploration of an object or issue. It is a more profound understanding than simple sensory experience.

- (6)

- ‘Active engagement’ refers to learners’ active participation in the learning process by physically moving, intellectually creating, actively working, and/or expressing their knowledge.

Meng and Uhrmacher (2014) used the CRISPA framework to examine the aesthetic approach of the teaching methods used by historical Chinese Chan masters. Their analysis of the records of Chan Buddhist masters revealed that teaching methods focused on the formation of holistic, emotional, and communicative connections between masters and disciples as well as active engagement as a core element of the practice. Chan teaching placed less emphasis on risk-taking, imagination, sensory experience, and perceptivity. Meng and Uhrmacher asserted that Chan masters did not use risk-taking very often because the hwadu can be too difficult to hold, and attempting to do this difficult work can lower practitioners’ enthusiasm especially if they are not in a safe environment. In addition, Chan masters claimed that Chan practice should be undertaken alone, and thus risk-taking, which is supposed to be based on social context, is not part of Chan teaching. Furthermore, Meng and Uhrmacher found that Chan masters did not prioritize imagination because they believed it causes mental delusions, and they placed relatively little emphasis on sensory experience because, unlike a non-enlightened person, the enlightened person sees without seeing and hears without hearing. Finally, Meng and Uhrmacher (2014) noted that Chan masters did not emphasize perceptivity because Chan teaching discourages logical understanding.

Overall, connection and active engagement were the most used elements, and risk-taking and perceptivity were the least used elements among the teaching features in Chan masters’ teaching practices. While this research effectively analyzed the records of Chinese Chan masters using the CRISPA framework, it is difficult to infer concrete details about the masters’ interactions and communications with Chan practitioners.

In the tradition of prior efforts to understand the characteristics of education in Asia through the lens of Western educational theories (Kim 2013; Sun 1999), the CRISPA framework can be applied to the teaching of Ganhwa Seon practice and can generate a better understanding of what happens as Seon masters lead practitioners. Examining the teaching features of current Seon masters using the CRISPA theory sheds light on both universal and distinctive aspects of Ganhwa Seon teaching.

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Research Design

The purpose of this study is to analyze the teaching approaches and practices of a Korean Ganhwa Seon master using an educational framework and to reveal the embedded meaning of Seon teachings. The research addresses two specific questions to achieve this purpose:

- (1)

- How do the aesthetic dimensions of CRISPA manifest in the teaching of a Korean Ganhwa Seon master?

- (2)

- How did the aspects of CRISPA change during the seven-day Ganhwa Seon retreat?

We conducted an intrinsic single-case study to examine these research questions. A case study is a research method that collects data through interviews, observations, documents, audio- or video-recordings, and journals, focusing on a single participant or multiple participants to explore an issue within a certain situation or context (Creswell 2007). According to Stake (2000), an intrinsic case study refers to an examination of a specific case, situation, or context driven by a researcher’s genuine interest or curiosity. This analysis is an intrinsic case study because it objectively explores the lived teaching experiences of a Korean Ganhwa Seon master based on the researchers’ genuine interest, which was sparked by Meng and Uhrmacher’s (2014) study of the aesthetic features of Chinese Chan masters. We conducted a single-case study because there are very few Ganhwa Seon masters who can guide members of the public to sudden enlightenment via a regular program, and it is difficult to find a Seon master who can participate in research. A single-case study entails an in-depth exploration of and rich explanations for one case (Lobo et al. 2017). Thus, we conducted an intrinsic single-case study to explore the teaching features of a Korean Ganhwa Seon master using the dimensions of the CRISPA framework.

4.2. The Study Participant

We used a purposive sampling procedure to select a Korean Ganhwa Seon master. There are a few Seon masters in Korea who guide members of the public to sudden enlightenment through Ganhwa Seon. Among them, we identified one Ganhwa Seon master who has been ordained in the Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism since 1973; who has taught many people, both monastics and lay people; and who has led Ganhwa Seon programs for over 30 years since founding a Seon center in 1989. After he agreed to participate in the study, we assigned him the pseudonym Ven. Beomsuk Sunim. He runs a seven-day Ganhwa Seon retreat program that accommodates both monastics and members of the public three to four times a year. The Seon center’s reports state that over 100 people participated in each program and Ven. Beomsuk Sunim has provided guidance to more than 30,000 people in the last 30 years.

On the first day of the retreat, Ven. Beomsuk Sunim presents the participants with the hwadu, ‘What moves this finger?’ Although he does not enforce a specific duration of practice, the program usually lasts from 8 a.m. to 10 p.m. and includes overnight practice for those who want to practice more. Ven. Beomsuk Sunim offers Dharma talks twice a day, at 10 a.m. and 2 p.m., as well as interview sessions after each talk, during which practitioners can ask questions and receive feedback on their practice.

4.3. Data Collection and Analysis

We observed the daily teachings of the Ganhwa Seon master during a seven-day retreat program and conducted eight semi-structured interviews, each lasting 1–3 h, before, during, and after the retreat (Seidman 2006). The observed teaching sessions and the interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed, and important details and the researchers’ thoughts were recorded in memos during the observation time and interviews. In addition, we collected and analyzed other documents the Seon master wrote about Ganhwa Seon to increase the validity of the study via data triangulation. The three members of the research team work in the fields of education, psychology, and Buddhist studies and have practiced various types of meditation. Based on our previous experiences of meditation practice and a thorough review of the theory underlying CRISPA, we first conducted a thematic analysis to adapt the CRISPA framework to the Ganhwa Seon teaching context. Next, each of us individually conducted an initial coding of the transcripts and memos based on our own perspectives. After this initial coding was complete, we jointly completed a second round of coding to examine core ideas within each dimension. Next, we used axial coding to identify the core themes that ran throughout the full Ganhwa Seon teaching retreat (Glaser and Strauss 1999). Following Yin’s (2002) suggestion that qualitative data can be examined quantitatively to gain new insights, we assessed the distribution of CRISPA dimensions in relation to the timeline of the seven-day retreat. Specifically, we coded the data collected in Korean for each element of CRISPA and then determined the word count for each element on each day (Yazan 2015). To gain a new perspective on the data and themes, we stopped meeting for a period and then resumed, conducting regular meetings 1–2 times per month. In total, we spent two years re-examining the identified themes. At three points in the analytical process, we communicated with the participating Seon master to validate the results. We then reviewed the final themes again and examined the core ideas more clearly. Through this process, we discovered the teaching methods of a Ganhwa Seon master.

5. Results

The analysis showed that the Ganhwa Seon master used all six CRISPA elements during the retreat. The frequency of each element varied over the course of the seven-day retreat. Each element of the CRISPA framework was conceptualized as follows: ‘being connected with the master’, ‘building great faith, great determination, and great doubt’, ‘drawing the mind and body in Ganhwa Seon practice’, ‘experiencing the sensations of penetration’, ‘awakening with a deeper understanding’, and ’just do it’. Compassion was an essential conceptual element that influenced the overall teaching of Ganhwa Seon.

5.1. How Did the Aesthetic Dimensions of CRISPA Manifest in the Teaching of a Korean Ganhwa Seon Master?

5.1.1. Connection: Being Connected with the Master

The Ganhwa Seon master employed three types of connection: emotional, intellectual, and communicative. Emotional connection was the most frequently used type and was achieved by the development of a sense of trust and empathy between the master and the practitioners. The master established trust by referencing his experience of personal practice, describing his moments of insight and the sensations that accompanied these moments, and cultivating practitioners’ internal motivations. Examples of these statements include the following: ‘There are people who have achieved this’, ‘At the end, there is something tremendous’, ‘How refreshing it would be to get rid of the heavy burden that weighed you down. It feels exhilarating’, ‘Prepare yourself with the determination that you can do it, and push through it’, ‘Believe that you won’t die with this practice and just do it’, and ‘There is absolutely nothing that can go wrong’.

The Ganhwa Seon master generated empathy by being open and by his ability to understand the practitioners’ feelings. For example, he told participants, ‘I didn’t think that I would achieve this in the Ganhwa Seon practice, but it became easy once I met an enlightened teacher’ and ‘I achieved it; please believe in yourself that you also can do it’. He also said, ‘Don’t lose your courage and do it with the determination to see it through to the end’. These statements forged a strong emotional connection based on trust and empathy between the master and the practitioners.

Ven. Beomsuk Sunim used intellectual connection by introducing cognitive tasks that helped practitioners understand the hwadu or the procedures of Seon practice. For example, he described ‘holding hwadu’ as ‘staring at the wall’ and used the metaphor of sunlight passing through a convex lens and converging into a single point of light to describe ‘focusing on hwadu’. In this way, the master made connections between hwadu practice and physical materials to explain the use of hwadu in the Seon practice.

Finally, the Seon master used communicative connection. He emphasized cooperation between the master and practitioners, noting that, ‘If something that doesn’t seem like a distraction comes in, it can be difficult to determine whether it is a distraction or not. That’s why you need a teacher’.

Taken together, these aesthetic features of connection in Ganhwa Seon teaching reveal a concept of compassion for the suffering of practitioners and show a desire to help them by pushing them to practice and break the hwadu. Furthermore, the element of connection highlights the relationships between master and practitioners in a compassionate way.

5.1.2. Risk-Taking: Building Great Faith, Great Determination, and Great Doubt

Ven. Beomsuk Sunim placed significant emphasis on risk-taking. When discussing risk-taking, he offered practitioners warm, kind instructions for addressing the difficulties they would encounter in their practice and made an intentional effort to push them to move forward. Describing the challenges of Ganhwa Seon practice can create fear among the practitioners. While explaining how to hold and then break the hwadu, the master compared it to several scary situations, noting ‘It is like pushing someone into the darkness without telling them how to find their way, and watching them fall’, ‘It feels suffocating, like wearing a sword on your back and being trapped in a prison that tightens from all directions’, ‘It is a matter of life and death. If you want to overcome this hurdle, you must push through it’, and ‘Even if you fall after reaching 99%, you must get up and climb back up again until you pass 100%’. By offering these descriptions of the challenges of Ganhwa Seon practice based on his conviction and compassion, the Seon master created great faith among the practitioners, aroused great determination to overcome difficulties, and induced a great doubt about the hwadu.

The Korean Ganhwa Seon master’s teaching methods included identifying multiple factors that help practitioners face and overcome the challenges of practice. In particular, the master guided practitioners systematically. He first emphasized the importance of having the intention to know the true nature, then guided practitioners to take the initiative with their own strength to achieve enlightenment and made them relax to practice, and finally encouraged them to have the courage to overcome difficulties or challenges in their practices, even if they felt they were failing. It is important for teachers to create a safe environment when promoting risk-taking (Meng and Uhrmacher 2014), and the Seon master created a safe context for practitioners to move forward. He helped practitioners awaken their true nature by having empathy for their suffering and by showing compassion as he pushed them to practice and move forward toward their goals.

5.1.3. Imagination: Drawing the Mind and Body in Ganhwa Seon Practice

During the seven-day retreat, the Seon master compassionately and consistently used imagination, including vivid metaphors and symbols, to help practitioners understand the hwadu and the process of Seon practice. The metaphors he used included dry firewood, boiling water, a water buffalo’s horn, a pill, childbirth, a knife under the chin, a butterfly’s first wing flap, a fish swimming upstream, a lion hunting a rabbit, a spinning top, a cicada shedding its skin, setting down a 110 kg load, a soloist and an orchestra, a two-eyed monkey in a world of three-eyed monkeys, a cat waiting for a mouse, a chicken brooding an egg, and the sound of a drum in a battlefield. Another imaginative example he offered is as follows:

For example, it is like going alone down the path of blood where thousands of enemies await you. If you go in without courage, you won’t make it. If you hesitate, you are going to die anyway. But if you go in determined to risk your life, then you won’t be bothered by the wounds you receive. If you start to worry about your wounds, you will die. You must fight without looking back at your injuries, even if you lose an arm or a leg.

By using these symbols and metaphors to create a vivid depiction of the path to sudden enlightenment, Ven. Beomsuk Sunim helped practitioners break through the hwadu with a determined mind.

5.1.4. Sensory Experience: Experiencing the Sensations of Penetration

The Korean Ganhwa Seon master focused on the bodily experiences of the practitioners, guiding them to recognize and embrace the sensations of insights arising within the body. He helped practitioners overcome the frustration and discomfort that can result from holding hwadu by encouraging them to be mindful of their bodily sensations and to accept new experiences without fear. Sharing experiences of bodily transformation is also considered an important aspect of Ganhwa Seon practice, and the master often affirmed and celebrated practitioners’ bodily sensations and experiences as they progressed on the path to sudden enlightenment. For example, he asked, ‘Do you feel it in your body? That’s good! That’s it!’ and commented, ‘How refreshing! You don’t have the heavy weight that used to press down on you’.

When the master first offered hwadu, he moved his finger and asked the practitioners, ‘What moves this finger?’ This is the hwadu that practitioners received, and they used the sensations coming in through their eyes to take in the master’s question and began to feel stuck, as if they were facing a wall. The master helped them experience this suffocating sensation in their bodies and then overcome the feeling of being stuck. The master also stressed that they should engage in this practice with their bodies, not their heads—he instructed, ‘From now on, practice as if you have no head above your neck. Your body is more important than your head’. Likewise, he emphasized the importance of experiencing Ganhwa Seon practice with the body rather than just intellectualizing the great question, hwadu.

5.1.5. Perceptivity: Awakening with a Deeper Understanding

Perceptivity refers to the experience of gaining a more detailed and profound understanding via sensory experiences. Ven. Beomsuk Sunim used perceptivity more frequently as the teaching moved from its initial stage to its middle stage. He began to offer more delicate and profound guidance that went beyond simple straightforward instructions. Specifically, the master described things that people who have not practiced cannot see, and compassionately and sequentially instructed practitioners in how to hold hwadu or what feelings are involved in holding hwadu and breaking it down. For example, he offered the following guidance:

‘If there is a mirror in front of you, what is reflected in the mirror is not you, and what is looking at the reflection in the mirror is also not you’.

‘Now you must hold the hwadu while listening to my words. My words are disturbing your attempts to hold hwadu’.

‘This is not a practice to get rid of delusions, but rather to accept them and work with them’.

‘You should do it even if you don’t feel anything. The point is not to worry about whether you feel or not, just do it’.

The master guided practitioners to move beyond bodily sensations and seek the feeling of emptiness, allowing them to enter a deeper stage of the practice and immerse themselves in it.

5.1.6. Active Engagement: Just Do It

The Korean Ganhwa Seon master used active engagement as a primary teaching method, urging practitioners to ‘Just do it’ throughout the seven-day retreat. The urge to practice was most intense on the third and fourth days, as many people began to feel tired or wanted to give up, according to our interview with Ven. Beomsuk Sunim. He emphasized the importance of having compassion toward those who have not yet experienced insight. To build trust and encourage the continued pursuit of breaking hwadu, he reassured practitioners that some of them had already experienced transformation on the third day.

The master used active engagement to promote the three elements of Ganhwa Seon, which are great faith, great determination, and great doubt. For example, he encouraged the practitioners by saying, ‘Don’t be afraid and just push through it. You need the courage to do so’, ‘Trust me, you won’t die. There is nothing to worry about’, and ‘You can do it. You can complete it in just one week’. These statements created a supportive and trusting relationship between the master and practitioners, allowing practitioners to actively engage in the practice in a safe and encouraging environment.

In addition, the master structured the retreat in a way that encouraged the practitioners who gained insight to inspire others to do the same. Everyone could witness the participants who had experienced an insight, which instilled a sense of determination and encouraged practitioners who may have been feeling frustrated or lost. The master clearly stated, ‘When you see others leaving, you wonder what you are doing here; it can make you feel frustrated. What is going on? Everyone is going out, but why am I staying here? This makes you feel motivated to practice. Oh! I need this kind of urge’. The master prompted the remaining practitioners to intensify their motivations and determination to practice deeply, creating deeper focus and commitment. The practitioners were encouraged to persevere and maintain their efforts. This kind of support boosted their courage and self-confidence, empowering them to confront the challenges of the practice.

Finally, the master urged practitioners to embrace doubt and uncertainty while holding hwadu. He repeatedly explained the feeling of being caught in doubt and encouraged them to break the hwadu by actively engaging in the practice. He explained, ‘I created an eerie atmosphere that made it feel impossible for you to sit still. It was frustrating because our minds kept wandering and we wanted to escape it’.

By building participants’ trust in the Seon practice and the Seon master, Ven. Beomsuk Sunim fostered a strong determination among practitioners to reach their goals. He also encouraged them to embrace great doubt and uncertainty through hwadu practice, which led them to immerse themselves and actively engage in the practice.

5.2. How Did the Aspects of CRISPA Change during the Seven-Day Ganhwa Seon Retreat?

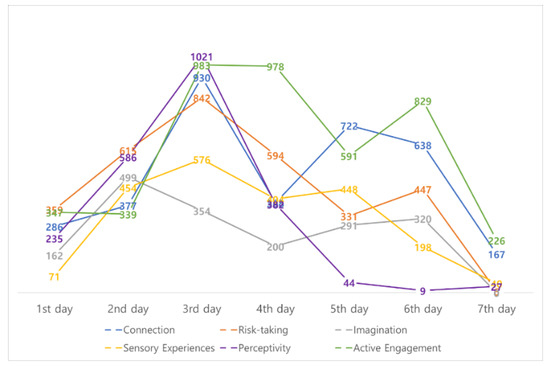

To analyze the manifestation of CRISPA in the teaching of Korean Ganhwa Seon, we classified the master’s explanations and statements from each day using the CRISPA elements and then conducted a word count for each element. First, however, we counted the total number of words spoken by the master per day. The master used 1358 words on the first day, 1500 words on the second day, 5361 words on the third day, 8848 words on the fourth day, 4151 words on the fifth day, 2559 words on the sixth day, and 2384 words on the seventh day. Thus, on the third and fifth days, he conveyed over twice as much teaching as on the first and second days. Strikingly, on the fourth day he conveyed over four times more than he did on each of the first two days.

Regarding the word count broken down by the elements in the CRISPA framework, the master conveyed 3508 words related to connection over the course of the retreat, 3194 words related to risk-taking, 1826 words related to imagination, 2191 words related to sensory experience, 2304 words related to perceptivity, and 4293 words related to active engagement. In sum, active engagement was the most frequently used element, followed by connection and risk-taking, which were used at similar levels. Sensory experience, perceptivity, and imagination were mentioned at somewhat lower frequencies.

Figure 1 shows the word count for each CRISPA element on each day. The number of words related to connection increased on the third day, decreased on the fourth day, and rose again on the fifth and sixth days before decreasing significantly on the seventh day. Risk-taking increased gradually, doubling by the third day. It then decreased again, rose slightly on day six, and fell significantly on the last day. The use of the imagination element increased on day two and was relatively consistent through the middle of the retreat but was not mentioned at all on the last day. Mentions of sensory experience increased on the second day and were frequent through day five but fell on the last two days. Perceptivity was used most often on day three and declined sharply after that point. Finally, active engagement was the most frequently used element over the course of the seven-day retreat. Discussion of this element peaked on day three but remained at a high level through day six. Even on the seventh day, Ven. Beomsuk Sunim used over 200 words to explain active engagement in Ganhwa Seon practice.

Figure 1.

Variation in the Use of CRISPA Elements during the 7-Day Ganhwa Seon Retreat.

6. Discussion

This study analyzed the teaching methods of a Korean Ganhwa Seon master during a seven-day retreat and revealed the embedded meanings of his teachings. We employed the CRISPA aesthetic dimensions to examine the process by which a Korean Ganhwa Seon master led the practitioners toward enlightenment, illustrating the patterns in the use of each CRISPA element in the instruction of Ganhwa Seon practice. The results highlighted three primary patterns. First, compassion plays a crucial role in Ganhwa Seon teaching. Second, each CRISPA element interacts with and influences the others. Third, the master’s teaching methods varied significantly over the seven-day retreat.

6.1. The Key Role of Compassion in Ganhwa Seon Teaching

First, Ven. Beomsuk Sunim employed a systematic and technical teaching method focused on compassion to guide practitioners toward obtaining a profound insight within seven days. Thus, we identified compassion as a key conceptual element of Ganhwa Seon teaching. According to the Merriam-Webster (n.d.) dictionary, compassion generally means ‘sympathetic consciousness of others’ distress together with a desire to alleviate it.’ Working from a psychological perspective, Strauss et al. (2016) offered a similar but more detailed explanation, defining compassion as the ability to identify, comprehend, and experience the suffering of another and the motivation to take action to relieve this suffering. Finally, using a Buddhist tradition perspective, Feldman and Kuyken (2011) defined compassion as a fundamental human attribute characterized by the tremble of the heart in response to pain, anger, suffering, sadness, and other distressing emotions, requiring the coexistence of courage, tolerance, and equanimity.

The Ganhwa Seon master who participated in this study guided practitioners with a compassionate heart, striving to help them become free from suffering. Rather than telling struggling practitioners to stop, the master demonstrated a great compassion that entailed both tolerance and courage by persistently pushing them to achieve freedom, even in the face of hardship while holding hwadu. In interviews, the master expressed compassion for practitioners who were struggling to realize their true nature. The Ganhwa Seon master’s teaching methods and his reflections on his interactions with practitioners illustrate the Buddhist teaching that compassion includes tolerance and courage in sharing the suffering of others.

The master’s intention to lead practitioners to experience liberation from suffering was infused with love and understanding for all humanity. Although the recounted stories of risk-taking could have been perceived as frightening or daunting, in the context of the compassionate guidance of the Ganhwa Seon master, they imbued the practitioners with a resolute and fearless mindset of ‘I have to try it’. The master’s words, actions, expressions, and gestures alleviated the suffering of practitioners, and thus helped prepare them for the shock of the failure of the practice. That is, the master’s compassion served as a buffer for participants. In Buddhism, there is a belief that ‘universal love and compassion’ embrace and encompass the sufferings of every being. The great compassion of the master was evident when he guided the practitioners toward their freedom from suffering.

Compassion also served as the basis for teaching when the Ganhwa Seon master utilized other CRISPA elements. For example, he used empathetic concern and disclosures about his own practice to foster trust among the practitioners. This approach is linked to building great faith, which is one of the core elements of Ganhwa Seon practice that enhances connections. To overcome the obstacles that arise during the practice of holding hwadu, practitioners should rely on the compassionate power of the master. In other words, compassion is the central element in the relationship between the master and the practitioners—it enables the formation of trust, gives the practitioners determination, and provides a safe context in which they can have great doubt. Furthermore, the master explained the content of enlightenment in an easy-to-understand manner and taught the practitioners detailed methods for overcoming obstacles to enlightenment by experiencing it in their own bodies. He used the elements of imagination, sensory experience, and perceptivity to help practitioners engage in the practice of hwadu so that they could be free from suffering―this explanation was another illustration of the master’s compassion.

Previous studies of Ganhwa Seon practice have focused on the results of the practice (Choo 2018; Li 2018; Yi 2006), and researchers and practitioners have highlighted the need for more thorough explanations of the role of compassion in Ganhwa Seon (Fischer 2013). In response to this call for more research, this practical study of a Korean Ganhwa Seon master revealed that compassion is the foundation of instruction in Ganhwa Seon practice.

6.2. Interaction between CRISPA Elements

A second main finding of the study was that each CRISPA element plays a significant role in promoting the Ganhwa Seon practice and these elements interact with one another to break the hwadu. Each element of the CRISPA framework was conceptualized in the teaching of Ganhwa Seon as ‘being connected with the master’, ‘building great faith, great determination, and great doubt’, ‘drawing the mind and body in Ganhwa Seon practice’, ‘experiencing the sensations of penetration’, ‘awakening with a deeper understanding’, and ’just do it’. That is, the processes of teaching and learning described in the research on traditional education settings are also present in the interactions between the Ganhwa Seon master and practitioners. Thus, the educational framework is a fruitful approach to describing the process of Ganhwa Seon teaching.

To date, most research on Ganhwa Seon has investigated the theories and literatures of ancient Seon masters (Lee 2015), rather than examining the teaching methods of Seon masters. This study conducted a close and detailed observation of a Ganhwa Seon master and revealed the teaching features embedded in his guidance of Seon. First, we found that connection played a vital role in establishing a reliable relationship between the master and practitioners during the seven-day retreat. This, in turn, encouraged practitioners to take risks. Smith et al. (2021) stated that a teacher’s affirmation can boost students’ engagement and positively influence their perception of the teacher. Similarly, the confident guidance of Ven. Beomsuk Sunim motivated the practitioners to take risks with faith and courage and to persist in their practice. The master’s sense of responsibility and conviction was evident as he explained in advance the challenges practitioners would face in their practice and helped them overcome these challenges with great faith, great determination, and great doubt. Using vivid symbols and metaphors, the master led practitioners through the physical and mental phenomena they encountered and provided guidance via sensory experiences, thus facilitating the transformation of being.

Furthermore, the master pushed practitioners to immerse themselves in the practice by saying ‘Just do it.’ In this way, connection, risk-taking, and active engagement interacted to generate great faith, great determination, and great doubt, while imagination, sensory experience, and perceptivity interacted to provide an explanation of the process and the results of the practice. In sum, the findings suggest that the CRISPA elements interacted with one another in the teaching of the Ganhwa Seon practice.

Instruction in Ganhwa Seon, as assessed in this study, aligns with the concept of inquiry-based education (Herman and Pinard 2015). Critical thinking, which involves questioning, exploring, and asking ‘why,’ encourages students to ask sincere questions and learn from the process of finding answers (Dewey 1910). In Ganhwa Seon, the master’s role is to guide practitioners with conviction, making them doubt the hwadu, which is a received question from the master, and turning them in to active practitioners (Buswell 1989). This hwadu is a great question that encourages practice through exploration and resolving doubts. Thus, the Ganhwa Seon master plays an important role in helping practitioners explore and resolve their doubts.

In addition, the participating Seon master constantly encouraged practitioners to ask questions, which gave them the freedom to ask any questions they had and, in turn, helped them understand the practice more clearly and immerse themselves in the practice more deeply. This approach aligns with inquiry-based education, which encourages students to be inquisitive and promotes active and self-directed learning. The participating Seon master stated that the role of a master is to create a whirlwind of doubt, like spinning a top until it appears to have stopped spinning. This statement also reflects the concept of inquisitiveness and making practitioners the center of learning. This study is significant because it used an educational framework to shed new light on the role of traditional Buddhist Seon masters and the process of teaching Seon. To our knowledge, it is the first study to observe aspects of Dewey’s progressive and practical education theory in traditional Korean Ganhwa Seon practice. The results offer practical insights into the actual teaching practices of a Ganhwa Seon master and have important implications for the development of meditation instruction.

6.3. Variation in Teaching Methods over Time

Finally, the findings revealed that a structured process of breaking through hwadu was manifested in the changing dynamics of the use of CRISPA elements over the seven-day retreat. The third and fourth days were the most content-rich, potentially signifying a climax. On the third day, there was an increase in the number of practitioners who experienced a type of mental transformation, and there was also an increase in the number of one-on-one interviews between the master and practitioners. Accordingly, the master was observed urging the remaining practitioners forward with compassion and motivation.

In this study, risk-taking was frequently encouraged in the aftermath of active engagement and connection. This result contrasts with the findings of Meng and Uhrmacher (2014), who had difficulty identifying risk-taking in Chan masters’ teachings in their analysis of written conversations between Chan masters and disciples. They posited that practitioners might be discouraged by what Chan masters said and thus not engage in risk-taking. However, we revealed that risk-taking played a significant role in guiding practitioners to engage in the practice sincerely, and that the seemingly discouraging remarks made by the Ganhwa Seon master were indeed offered with compassionate guidance, encouraging practitioners to step forward and have great faith, great determination, and great doubt. This type of risk-taking may be facilitated by the dynamic social process that occurs when more than 100 people practice together in the Seon center, relying on and envying one another.

Meng and Uhrmacher (2014) also stated that the Chan masters in their study did not use imagination very often and concluded that imagination can generate lingering thoughts that interfere with enlightenment. However, the participating Seon master utilized imagination on six of the seven retreat days, leveraging it to help practitioners concentrate during hwadu practice, understand how to hold hwadu, visualize the process of breaking hwadu, and explain the results of the practice and ways to overcome challenges. The Seon master’s approach suggests that imagination may be a useful tool in Ganhwa Seon practices. Furthermore, Meng and Uhrmacher (2014) stated that Chan teaching did not emphasize sensory experience. In contrast, Ven. Beomsuk Sunim repeatedly asked practitioners how they felt in their bodies and emphasized the importance of using the body rather than the mind. In his final interview with practitioners about the insights they had experienced, the master asked about bodily experiences. These findings highlighted a discrepancy between the teaching of Chinese Chan masters (as described by Meng and Uhrmacher 2014) and the teaching of a Korean Ganhwa Seon master. Thus, this analysis extends the literature on Ganhwa Seon by offering novel concrete insights into how a Korean Ganhwa Seon master uses the teaching features of CRISPA.

7. Conclusions

By using the Western educational framework of CRISPA to closely examine the work of a Korean Ganhwa Seon master, this study explored the meaning of Ganhwa Seon teaching methods. In conclusion, the study revealed the significance of both universality and uniqueness in the teaching of Ganhwa Seon.

First, this study overcame the limitations of prior research that analyzed Chan teaching records by observing and interviewing a living Seon master and thus revealing that Buddhist practices ultimately occur in interactions between a teacher and their disciples. Thus, the study offers a novel perspective on Ganhwa Seon. We also discovered that compassion plays a central role in Seon practice, thus highlighting how important it is for all educators to cultivate compassion, love, and caring (O’toole and Dobutowitsch 2022). The Ganhwa Seon master was reliable and confident in his guidance, which facilitated participants’ engagement and their execution of the practice. The crucial role of compassion applies to not only Ganhwa Seon practice but also other religious and spiritual guidance that entails teaching and learning processes.

Additionally, we identified unique aspects of Ganhwa Seon teaching. Ganhwa Seon masters should push practitioners to immerse themselves deeply in the practice and persist in their pursuit of sudden enlightenment. This is not possible without compassion, perseverance, supportive care, and the courage to acknowledge the sufferings of practitioners. Furthermore, the systematic approach of the seven-day retreat embodied a unique variation of aesthetic features in its guidance in the Ganhwa Seon practice. Therefore, when engaging in religious, spiritual, or general teaching, it is important to approach the instruction systematically, based on its purpose.

This study demonstrated that practitioners can experience a moment of insight in just seven days of Ganhwa Seon practice. This finding is consistent with prior research that suggested short-term meditation practice can produce positive changes in participants (Weng et al. 2013). Importantly, in a relatively short meditation program, the approach and attitude of the teacher have a significant impact on the outcomes of the practice. This is not surprising, given that researchers have asserted that teacher quality and other teacher characteristics are crucial for teaching and learning processes (Nye et al. 2004). Thus, research on the approach and attitude of successful meditation teachers is necessary.

The current study used the educational framework of CRISPA to analyze the aesthetic features of a Ganhwa Seon master’s instructional approach and demonstrated that this approach provides practitioners with a variety of experiences and profound insights in a short period of time. Furthermore, the study revealed that the characteristics of Ganhwa Seon instruction can inspire other educators and religious leaders. The use of educational tools enabled a more specific and experiential analysis. Teaching and learning processes in the areas of meditation, religion, and similar content should emphasize compassion and include taking responsibility and having confidence in the teacher. Future research should incorporate both qualitative and quantitative approaches and should investigate the effects of Ganhwa Seon teaching. Overall, this study offers valuable insights into the teaching of Ganhwa Seon and the role of a Seon master.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.J.M.; methodology, H.J.M.; software, H.J.M. and J.Y.J.; validation, H.J.M., J.Y.J. and S.Y.S.; formal analysis, H.J.M.; investigation, H.J.M., J.Y.J. and S.Y.S.; resources, H.J.M.; data curation, H.J.M.; writing—original draft preparation, H.J.M.; writing—review and editing, H.J.M. and S.Y.S.; visualization, J.Y.J.; supervision, H.J.M.; project administration, H.J.M.; funding acquisition, H.J.M., J.Y.J. and S.Y.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is funded by [Anguk Zen Center-Busan].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical Review and approval were waived for this study.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Berger, Emanuel M. 1962. Zen Buddhism, General Psychology, and Counseling Psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology 9: 122–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buswell, Robert E. 1999. Buddhism under confucian domination: The synthetic vision of Sŏsan Hyujŏng. In Culture and the State in Late Chosŏn Korea. Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center, pp. 134–59. [Google Scholar]

- Buswell, Robert E., Jr. 1989. Chinul’s Ambivalent Critique of Radical Subitism in Korean Sŏn. Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies 12: 20–44. [Google Scholar]

- Buswell, Robert E., Jr. 2011. Pojo Chinul and Kanhwa Son: Reconciling the language of moderate and radical subitism. Zen Buddhist Rhetoric in China, Korea, and Japan 3: 345. [Google Scholar]

- Choo, B. Hyun. 2018. Tracing the Satipaṭṭhāna in the Korean Ganhwa Seon Tradition: Its Periscope Visibility in the Mindful hwadu Sisimma, ‘Sati-Sisimma’. Religions 9: 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, John W. 2007. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, John. 1910. How we Think. Boston: D.C. Heath. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, John. 1934. Art as Experience. New York: Perigee Books. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, Christina, and Willem Kuyken. 2011. Compassion in the landscape of suffering. Contemporary Buddhism 12: 143–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, Norman. 2013. Training in Compassion: Zen Teachings on the Practice of Lojong. Boston and London: Shambhala. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, Paul. 2009. Introducing Compassion-Focused Therapy. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment 15: 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, Barney, and Anselm Strauss. 1999. Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman, Barbara L., Paul J. Domotor, and Edward Murray J. 1979. Effects of Zen Meditation on Anxiety Reduction and Perceptual Functioning. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 47: 551–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, Stephen C., Jason B. Luoma, Frank W. Bond, Akihiko Masuda, and Jason Lillis. 2006. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: Model, processes and outcomes. Psychology Faculty Publications 44: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herman, William E., and Michaele R. Pinard. 2015. Critically Examining Inquiry-Based Learning: John Dewey in Theory, History, and Practice. In Inquiry-Based Learning for Multidisciplinary Programs: A Conceptual and Practical Resource for Educators. Edited by Patrick Blessinger and John M. Carfora. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited, vol. 3, pp. 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jazaieri, Hooria, Geshe Thupten Jinpa, Kelly McGonigal, Erika L. Rosenberg, Joel Finkelstein, Emiliana Simon-Thomas, Margaret Cullen, James R. Doty, James J. Gross, and Philippe R. Goldin. 2013. Enhancing compassion: A randomized controlled trial of a compassion cultivation training program. Journal of Happiness Studies 14: 1113–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Jun Young, and Sung Hyun Park. 2010. Sati in early Buddhism and Mindfulness in Current Psychology: A Proposal for Establishing the Construct of Mindfulness. Korean Journal of Counseling and Psychotherapy 22: 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism. 2006. 간화선입문. [Introduction to Ganhwa Seon]. Seoul: Jogye Jong Publishing (조계종출판사). [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn, Jon. 2004. Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR). Constructivism in the Human Sciences 8: 73–107. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Sang Hyun. 2013. The Problem of Authority: What Can Korean Education Learn from Dewey? Education and Culture 29: 64–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Pilwon. 2015. Ganhwaseon and psychotherapy: Focusing on current research trend. The Journal of Indian Philosophy 44: 191–221. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Haedo. 2018. Hwalgu: Characteristics of Master Zonggao’s Ganhwa Seon. Journal of Korean Seon Studies 49: 29–56. [Google Scholar]

- Lobo, Michele A., Mariola Moeyaert, Andrea Baraldi Cunha, and Iryna Babik. 2017. Single-Case Design, Analysis, and Quality Assessment for Intervention Research. Journal of Neurologic Physical Therapy 41: 187–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malec, James, and Carl N. Sipprelle. 1977. Physiological and Subjective Effects of Zen Meditation and Demand Characteristics. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 45: 339–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maupin, Edward W. 1962. Zen Buddhism: A psychological review. Journal of Consulting Psychology 26: 362–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Lingqi, and P. Bruce Uhrmacher. 2014. Chan teaching and learning: An aesthetic analysis of its educational import. Asia Pacific Education Review 15: 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merriam-Webster. n.d. Compassion. In Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Available online: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/compassion (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- Min, Hee Jung. 2017. Contemplative education as a content area of education: Through the review of educational research in the US. The Journal of the Korea Contents Association 17: 606–18. [Google Scholar]

- Moroye, Christiy McConnell, and P. Bruce Uhrmacher. 2009. Aesthetic themes of education. Curriculum and Teaching Dialogue 11: 85–101. [Google Scholar]

- Neff, Kristin D., and Christopher K. Germer. 2013. A pilot study and randomized controlled trial of the mindful self-compassion program. Journal of Clinical Psychology 69: 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyanatiloka, Thera. 1988. Buddhist Dictionary. Colombo: Buddhist Publication Society Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Nye, Barbara, Spyros Konstantopoulos, and Larry V. Hedges. 2004. How large are teacher effects. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 26: 237–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’toole, Catriona, and Mira Dobutowitsch. 2022. The courage to care: Teacher compassion predicts more positive attitudes toward trauma-informed practice. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma 16: 123–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pace, Thaddeus W. W., Lobsang Tenzin Negi, Daniel D. Adame, Steven P. Cole, Teresa I. Sivilli, Timothy D. Brown, Michael J. Issa, and Charles L. Raison. 2009. Effect of compassion meditation on neuroendocrine, innate immune and behavioral responses to psychosocial stress. Psycho Neuro Endocrinology 34: 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, Jpshua L., LaKami T. Baker, and Donde Ashmos Plowman. 2011. Organizational Mindfulness in Business Schools. Academy of Management Learning and Education 10: 188–203. [Google Scholar]

- Rhys Davids, Thomas William, and William Stede. 1993. Pali-English Dictionary. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publication. [Google Scholar]

- Seidman, Irving. 2006. Interviewing as Qualitative Research: A Guide for Researchers in Education and the Social Sciences. New York: Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, Deane H., and Steven M. Zifferblatt. 1976. Zen Meditation and Behavioral Self-Control Similarities, Differences, and Clinical Application. American Psychologist 31: 519–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Eric N., Christopher S. Rozek, Kody J. Manke, Carol S. Dweck, and Gregory M. Walton. 2021. Teacher- versus researcher-provided affirmation effects on students’ task engagement and positive perceptions of teachers. Journal of Social Issues 77: 751–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Jonathan C. 1975. Meditation as Psychotherapy: A Review of the Literature. Psychological Bulletin 82: 558–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stake, Robert E. 2000. Case Studies. In Handbook of Qualitative Research. Edited by Norman K. Denzin and Yvonne Sessions Lincoln. Thousand Oaks: SAGE, pp. 435–53. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, Clara, Billie Lever Taylor, Jenny Gu, Willem Kuyken, Ruth Baer, Fergal Jones, and Kate Cavanagh. 2016. What is compassion and how can we measure it? a review of definitions and measures. Clinical Psychology Review 47: 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Youzhong. 1999. John Dewey in China: Yesterday and today. Transactions of the Charles S. Peirce Society 35: 69–88. [Google Scholar]

- Sung, Seong Yun, and Sung Hyun Park. 2011. A qualitative research about experience of Ganhwa Seon. The Korean Journal of Counseling and Psychotherapy 23: 323–57. [Google Scholar]

- Teasdale, John D., Zendel Segal, and J. Mark G. Williams. 1995. How does cognitive therapy prevent depressive relapse and why should attentional control (mindfulness) training help. Behaviour Research and Therapy 33: 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhrmacher, P. Bruce. 2009. Toward a theory of aesthetic learning experiences. Curriculum Inquiry 39: 613–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhrmacher, P. Bruce, Bradley M. Conrad, and Christy M. Moroye. 2013. Finding the balance between process and product in perceptual lesson planning. Teachers College Record 115: 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Helen Y., Andrew S. Fox, Alexander J. Shackman, Diane E. Stodola, Jessica Z. K. Caldwell, Matthew C. Olson, Gregory M. Rogers, and Richard J. Davidson. 2013. Compassion Training Alters Altruism and Neural Responses to Suffering. Psychological Science 24: 1171–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yazan, Bedrettin. 2015. Three approaches to case study methods in education: Yin, Merriam, and Stake. The Qualitative Report 20: 134–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Deok Jin. 2006. An observation of Mahayana sutra quoted in Seojang by the Master Daehye. The Journal of the Korean Association for Buddhist Studies 46: 249–95. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Robert K. 2002. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).