The Mandorla Symbol in Byzantine and Post-Byzantine Iconography of the Dormition: Function and Meaning

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Iconography of the Dormition

3. The Symbol of Mandorla in Byzantine Iconography of the Dormition

3.1. Early Examples without Mandorla

“But the apostles carrying Mary came into the place of the valley of Iosaphat which the Lord have showed them, and laid her in a new tomb and shut the sepulchre. But they sat down at the door of the tomb as the Lord had charged them: and lo, suddenly the Lord Jesus Christ came with a great multitude of angels, and light flashing with great brightness, and said to the apostles: Peace be with you”.(Pseudo-Melito. De Transitu Virginis Mariæ Liber., XVI. In: (James 1924, p. 215).)

“’Then the apostles laid the body in the tomb with great honour, weeping and singing for pure love and sweetness. And suddenly a light from heaven shone round about them, and as they fell to the earth, the holy body was taken up by angels into heaven’ (the apostles not knowing it)”.(Pseudo-Joseph of Arimathea. De Transitu Virginis Mariæ Liber., 16. In: (James 1924, p. 217).)

“…The Holy Scripture inspired by God does not tell what happened in the death of the Holy Theotókos Mary, but we rely on an ancient tradition and very true that at the time of her glorious Dormition, all the holy apostles, which roamed the earth for the salvation of the nations, were assembled in an instant through the air in Jerusalem. When they were close to her, angels appeared to them in a vision, and a divine concert of the higher power was heard. And so, in a divine and heavenly glory, the Virgin gave her holy soul in the God’s hands in an ineffable way…”.(Saint Jean Damascène, Deuxième discours sur l’illustre Dormition de la Toute Sainte et toujours Vierge Marie, 18. In: (Saint Jean Damascène 1961, p. 173).)

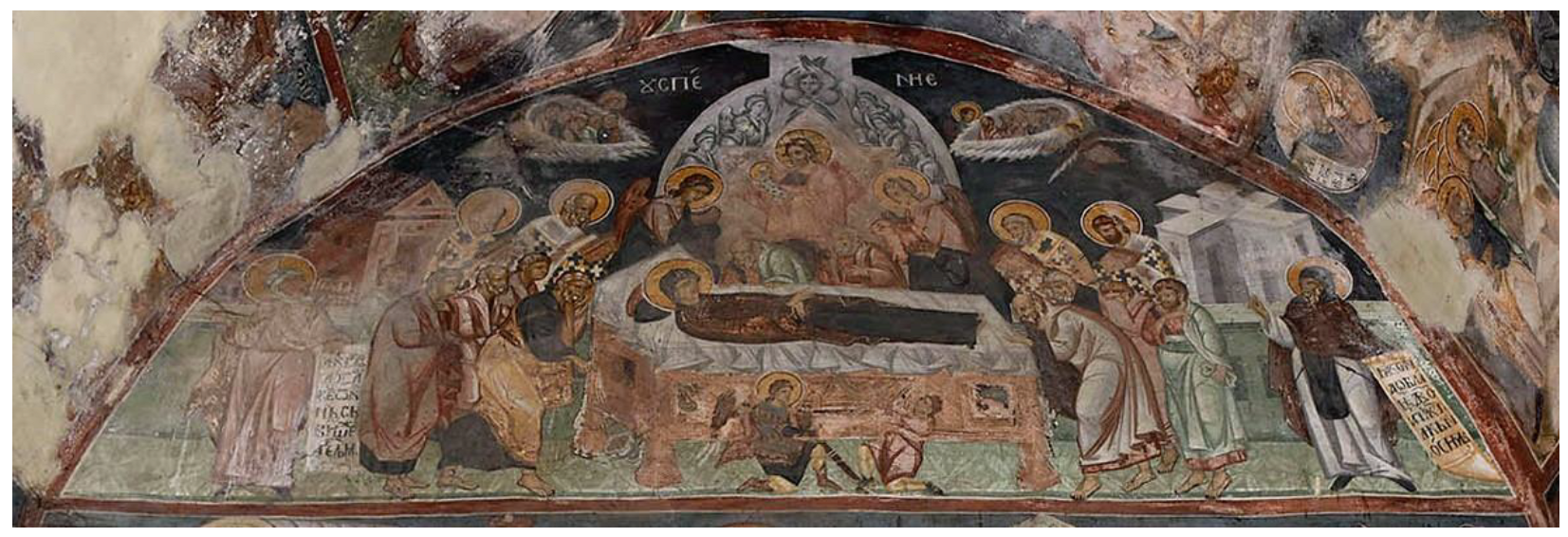

3.2. Appearance of Mandorla without Inscribed Angelic Powers

3.3. Addition of Star-Shaped Geometric Forms to the Mandorla

3.4. The Model from the Dormition Mosaic in the Chora Monastery

“Fixed, almost incapable of changing for the worst, they encircle God, the first cause, in their dance. … He makes them shine with purest brilliance or each with a different brilliance to match his nature’s rank. So strongly do they bear the shape and imprint of God’s beauty, that they become in their turn lights, able to give light to others by transmitting the stream which flows from the primal light of God. As ministers of the divine will, powerful with inborn and acquired strength, they range over the universe. They are quickly at hand to all in any place…”.(St. Gregory Nazianzus. Orationes theologicae. 28.31. On the doctrine of God. In: (Norris et al. 1991, p. 244).)

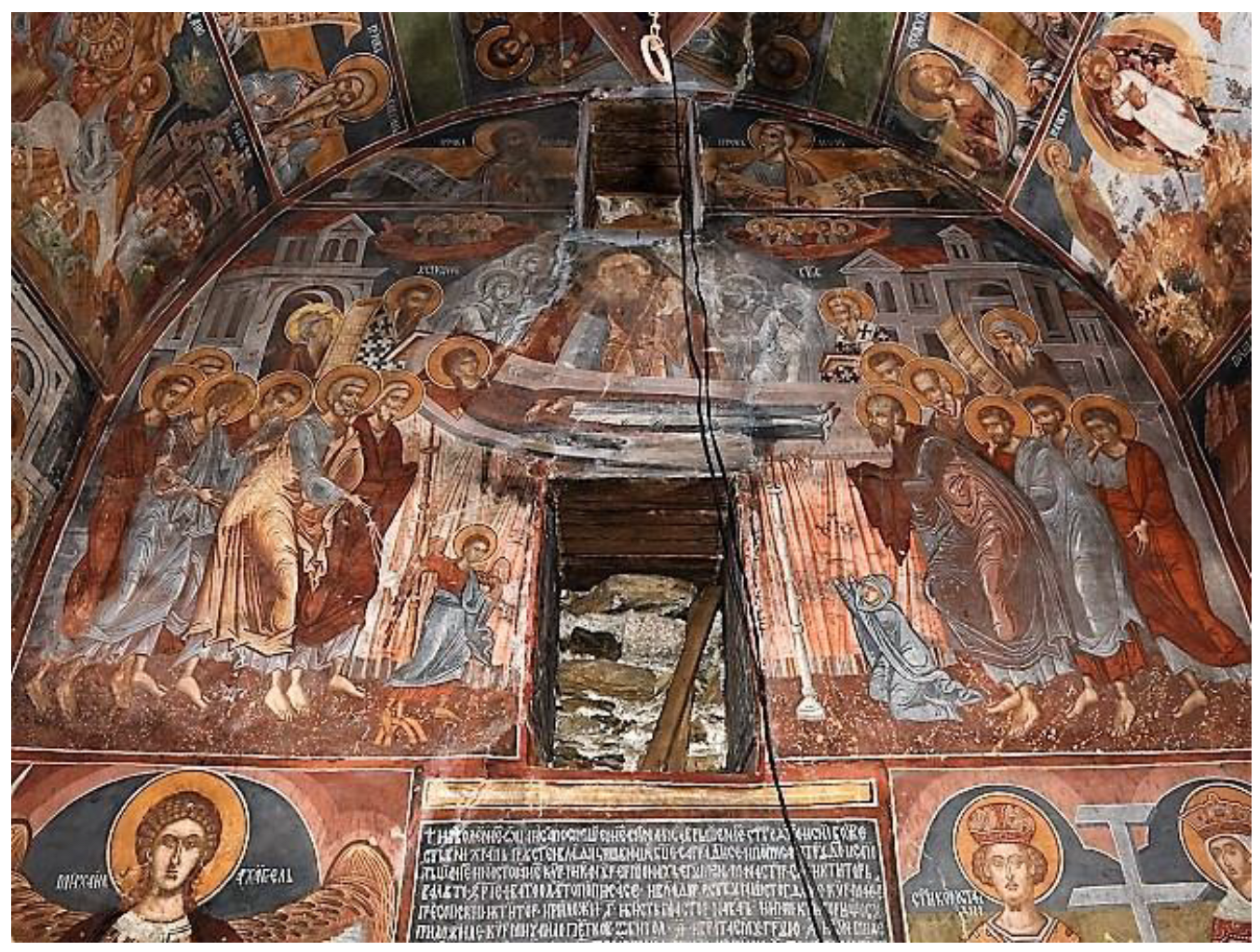

3.5. Spread of the Model from the Chora Monastery

4. The Symbol of Mandorla in Post-Byzantine Iconography of the Dormition on the Balkans

4.1. Following the Palaiologan Model from the Chora Monastery with the Inscription of Monochrome Angelic Powers into the Mandorla

4.2. Following the Earlier Iconographic Scheme without Angelic Powers into the Mandorla

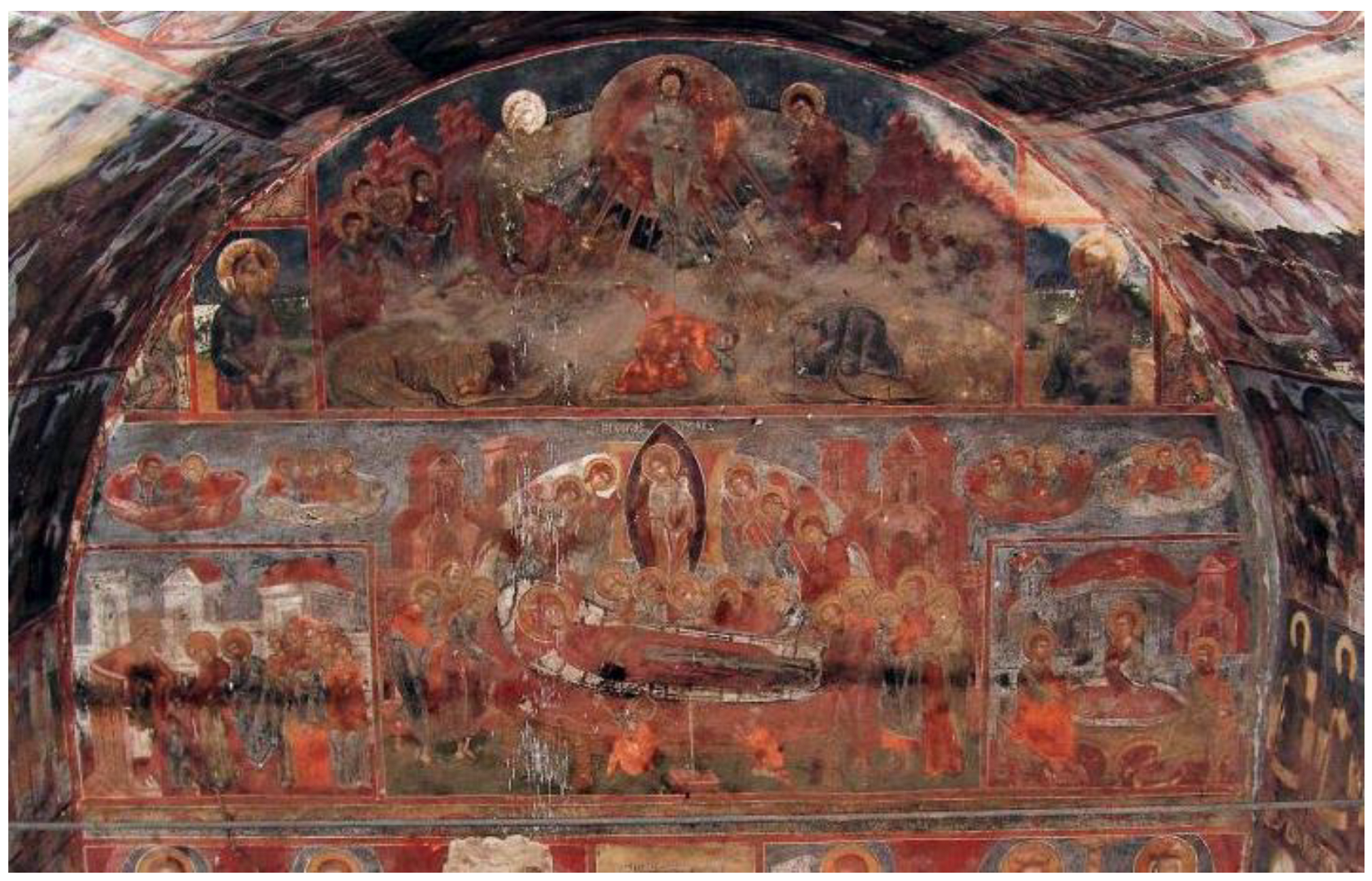

4.3. Using a Complicated Scheme That Combines Scenes of the Dormition and the Assumption of the Virgin into Heaven

4.4. Examples with Unique Shapes and Color Schemes of the Mandorla

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Dormition of the Virgin (Koimesis), XI (XII?) century. Princeton Work Number 87. Available at: https://bit.ly/3HkFsgo (accessed on 2 February 2023). |

| 2 | See the image in the digital collection of the The J. Paul Getty Museum: https://bit.ly/2VdYcHs (accessed on 2 February 2023). More info here: (Marinis 2004). |

| 3 | Some researchers believe that there were three painters whose names were Astrapas, Michael, and Euthychius. See: (Talbot Rice 1966, pp. 205–6). |

| 4 | See more about the St. Petka Church in Selnik here: http://zografi.info/?page_id=298 (accessed on 2 February 2023). |

| 5 | See the image here: http://zografi.info/?page_id=243 (accessed on 2 February 2023). |

| 6 | The use of numbering (II) was adopted by Tsámpouras in his dissertation to distinguish between painters by the same name. The same goes for the painters Nikolaos (III) and (IV) mentioned further down. |

| 7 | See the image here and some more information about the iconographic program of the church here: http://zografi.info/?page_id=183 (accessed on 2 February 2023). |

References

Primary Sources

Pseudo-Joseph of Arimathea. De Transitu Virginis Mariæ Liber., 16. In (James 1924). James, Montague Rhodes (transl). 1924. The Apocryphal New Testament. Oxford: Clarendon Press.Pseudo-Melito. De Transitu Virginis Mariæ Liber., XVI. In (James 1924). James, Montague Rhodes (transl). 1924. The Apocryphal New Testament. Oxford: Clarendon Press.St. Gregory Nazianzos. Orationes theologicae. 28.31. On the doctrine of God. In (Norris et al. 1991) Norris, Frederick W., and Lionel Wickkham. 1991. Faith Gives Fullness to Reasoning. The Five Theological Orations of Gregory Nazianzen. Edited by Frederick W. Norris and Lionel Wickkham. Leiden: BRILL.Saint Jean Damascène, Deuxième discours sur l’illustre Dormition de la Toute Sainte et toujours Vierge Marie, 18. In: Saint Jean Damascène. 1961. Homélies sur la Nativité et la Dormition (Texte grec, introduction, traduction et notes par Pierre Voulet). Paris: Les Éditions du Cerf, Coll. Sources Chrétiennes. As cited in: (Salvador-González 2017, p. 190).Secondary Sources

- Akhimástou-Potamiánou, Mirtáli. 1997. Ikónes tis Zakínthou. Athína: Ierá Mitrópolis Zakínthou kai Strophádon. [Google Scholar]

- Arteni, Ștefan. 2014. Painting in Romania. Sollnvictus Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bakalova, Elka. 1976. Stenopisite na tsarkvata pri selo Berende. Sofiya: Balgarski Hudozhnik. [Google Scholar]

- Bakalova, Elka, Vera Vasileva Kolarova, Petar Popov, Valentin Todorov, Vassos Karageorghis, and Louisa Leventis. 2003. The Ossuary of the Bachkovo Monastery. Plovdiv: Pigmalion. [Google Scholar]

- Barbu, Daniel. 1986. Pictura murală in Ţara Românească în secolul al XIV-lea. Bucureşti: Meridiane. [Google Scholar]

- Baryames, Rozalie. 1977. The Iconography of the Koimesis: Its Sources and Early Development. Master’s Thesis, Department of Art, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, Annemarie Weyl. 1997. Popular Imagery. In The Glory of Byzantium: Art and Culture of the Middle Byzantine Era, A.D. 843–1261. Edited by Helen C. Evans and William D. Wixom. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, pp. 113–17. [Google Scholar]

- Djuric, Voislav. 2000. Vizantiyskiye freski. Srednevekovaya Serbiya, Dalmatsiya, slavyanskaya Makedoniya. Moskva: Indrik. [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrova, Elizabeta. 2016. The Church of Saint George at Kurbinovo. Skopje: Cultural Heritage Protection Office. [Google Scholar]

- Drandáki, Anastasía. 2002. Ikónes, 14os-18os aiónas. Silloyí R. Andreádi. Milano: Skira. [Google Scholar]

- Eastmond, Antony. 2011. Messages, Meanings and Metamorphoses: The Icon of the Transfiguration of Zarzma. In Images of the Byzantine World: Visions, Messages and Meanings. Studies Presented to Leslie Brubaker. Edited by Angeliki Limberopoulou. Farnham: Ashgate, pp. 57–82. [Google Scholar]

- Floreva, Elena. 1983. Alinskite stenopisi. Sofiya: Balgarski Hudozhnik. [Google Scholar]

- Floreva, Elena. 1987. Srednovekovni stenopisi Vukovo 1598. Tsarkvata „Sv. Petka“. Sofiya: Balgarski Hudozhnik. [Google Scholar]

- Floreva, Elena. 1968. Starata tsarkva na Dragalevskiya manastir. Sofiya: Balgarski Hudozhnik. [Google Scholar]

- Gergova, Ivanka. 2012. Seslavski manastir “Sv. Nikola“. In Korpus na stenopisite ot XVII v. v Balgariya. Red. ot Penkova, Biserka i Tsveta Kuneva. Sofiya: BAN, pp. 47–57. [Google Scholar]

- Gergova, Ivanka, and Biserka Penkova. 2012a. “Sv. Atanasiy“, Arbanasi. In Korpus na stenopisite ot XVII v. v Balgariya. Red. ot Penkova, Biserka i Tsveta Kuneva. Sofiya: BAN, pp. 153–64. [Google Scholar]

- Gergova, Ivanka, and Biserka Penkova. 2012b. “Sv. Georgi“, Veliko Tarnovo. In Korpus na stenopisite ot XVII v. v Balgariya. Red. ot Penkova, Biserka i Tsveta Kuneva. Sofiya: BAN, pp. 58–66. [Google Scholar]

- Gergova, Ivanka, and Biserka Penkova. 2012c. “Sv. Dimitar“, Arbanasi. In Korpus na stenopisite ot XVII v. v Balgariya. Red. ot Penkova, Biserka i Tsveta Kuneva. Sofiya: BAN, pp. 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- Gerov, Georgi, Elka Bakalova, and Tsveta Kuneva. 2012. “Rozhdestvo Hristovo”, Arbanasi. In Korpus na stenopisite ot XVII v. v Balgariya. Red. ot Penkova, Biserka i Tsveta Kuneva. Sofiya: BAN, pp. 91–125. [Google Scholar]

- Grabar, André. 1928. La peinture religieuse en Bulgarie. Docteur ès lettres charge de conférences a la Faculté des letttres de Strasbourg. Préface de Gabriel Millet. Paris: Librairie Orientaliste. [Google Scholar]

- Grabar, Andrey. 1978. Boyanskata tsarkva. Sofiya: Nauka i izkustvo. [Google Scholar]

- Grecu, Dorin. 2011. Raportul lumină—culoare în pictura bizantină. Tipuri de lumină, Museum. Studii şi comunicări, X. Goleşti-Argeş: Tiparg. [Google Scholar]

- Jolivet-Lévy, Catherine. 1991. Les églises byzantines de Cappadoce. Le programme iconographique de l’abside et de ses abords. Paris: Editions du CNRS. [Google Scholar]

- Karahan, Anne. 2010. Byzantine Holy Images—Transcendence and Immanence: The Theological Background of the Iconography and Aesthetics of the Chora Church. Leuven: Peeters. [Google Scholar]

- Kartsonis, Anna. 1986. Anastasis: The Making of an Image. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Khatzidákis, Manólis. 2004. Ikónes tis Kritikís Tékhnis. Iráklion: Vikelaía Dimotikí Vivliothíki. [Google Scholar]

- Khatzidákis, Manólis. 1985. Vizantiní kai Metavizantiní Tékhni. Athína. Palió Panepistímio 26 ‘Ioulíou 1985–6 ‘Ianouaríou 1986. Athína Politistikí Protévousa tis Evrópis. [Google Scholar]

- Khatzidáki, Nanó. 1997. Ikónes tis Silloyís Velimézi. Thessaloníki: Politistikí Protévousas tis Evrópis. [Google Scholar]

- Kolusheva, Mariya. 2018. Tsarkvata “Uspenie Bogorodichno” v Zervat, Albaniya. Problemi na izkustvoto 1: 59–74. [Google Scholar]

- Kolusheva, Mariya. 2020. Dobarsko, tsarkva “Sv. Teodor Tiron i Teodor Stratilat”. In Patishta na balkanskite zografi. Red. ot Penkova, Biserka. Sofiya: BAN, pp. 124–29. [Google Scholar]

- Kuneva, Tsveta. 2018. Kam vaprosa za hronologichnite i teritorialni ramki na kosturskiya hudozhestven krag ot XV—XVI vek. Problemi na izkustvoto 1: 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Kuneva, Tsveta. 2012. “Sv. Teodor Tiron i Teodor Stratilat, Dobarsko”. In Korpus na stenopisite ot XVII v. v Balgariya. Red. ot Penkova, Biserka i Tsveta Kuneva. Sofiya: BAN, pp. 33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Kuyumdzhieva, Margarita. 2012. Alinski manastir “Sv. Spas”. In Korpus na stenopisite ot XVII v. v Balgariya. Red. ot Penkova, Biserka i Tsveta Kuneva. Sofiya: BAN, pp. 75–80. [Google Scholar]

- Kuyumdzhieva, Margarita. 2020a. Alinski manastir “Vaznesenie Hristovo”. In Patishta na balkanskite zografi. Red. Ot Penkova, Biserka. Sofiya: BAN, pp. 112–15. [Google Scholar]

- Kuyumdzhieva, Margarita. 2020b. Seslavski manastir “Sv. Nikola”. In Patishta na balkanskite zografi. Red. ot Penkova, Biserka. Sofiya: BAN, pp. 166–73. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarev, Viktor N. 1986. Istoriya vizantiyskoy zhivopisi. Moskva: Iskusstvo. [Google Scholar]

- Lowden, John. 1997. Early Christian and Byzantine Art. London: Phaidon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Maguire, Henry. 2019. Art and Eloquence in Byzantium. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Makseliene, Simona. 1998. The Glory of God and Its Byzantine Iconography. Unpublished Master’s Thesis in Medieval Studies. Central European University, Budapest, Hungary. [Google Scholar]

- Malmquist, Tatiana. 1979. Byzantine 12th Century Frescoes in Kastoria: Agioi Anargyroi and Agios Nikolaos Tou Kasnitzi. Uppsala: University of Uppsala. [Google Scholar]

- Marinis, Vasileos N. 2004. 169. Tetraevangelion (Four Gospoels). In Byzantium: Faith and Power (1261–1557). Edited by Helen C. Evans. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, pp. 284–85. [Google Scholar]

- Mašnik, Mirяna. 1994. Crkvata sv. Petka vo Selnik i nejzinite paraleli vo slikarstvoto na Alinskiot manastir sv. Spas. In Kulturno nasledstvo. T. 17/18, 1990–1991. Skopje: pp. 101–24. [Google Scholar]

- Mihail, Ion. 1917–1923. Pictura Bisericii Domneşti din Curtea de Argeş. BCMI anul X-XVI: 172–89. [Google Scholar]

- Millet, Gabriel. 1927. Monuments de l’Athos relevés avec le concours de l’armée française d’Orient et de l’Ecole française d’Athènes. I. Les Peintures. Paris: E. Leroux. [Google Scholar]

- Mincheva, Kalina, and Svetozar Angelov. 2007. Tsarkvi i manastiri v Yugozapadna Balgariya ot XV-XVII v. Sofiya. [Google Scholar]

- Najork, Daniel. 2018. The Middle English Translation of the Transitus Mariae Attributed to Joseph of Arimathea: An Edition of Oxford, All Souls College, MS 26. JEGP 117: 478–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolaïdès, Andreas. 1996. L’église de la Panagia Arakiotissa à Lagoudéra, Chypre: Etude iconographique des fresques de 1192. DOP 50: 1–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ousterhout, Robert. 2002. The Art of the Karije Camii. London and Istanbul: Scala Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Panagopoulos, Spyros. 2013. The Byzantine Traditions of the Virgin Mary’s Dormition and Assumption. Studia Patristica 63: 343–51. [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos, Stelios, and Chrysoula Kapioldassi-Soteropoulou. 1998. Icons of the Holy Monastery of Pantoktaror. Mount Athos: Mount Athos. [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoúlou, Varvára, and Aglaïa Tsiára. 2008. Ikónes tis Ártas. I ekklisiastikí zographikí stin periokhí tis Ártas katá tous vizantinoús kai metavizantinoús khrónous. Árta: Ierá Mitrópolis Ártis. [Google Scholar]

- Penkova, Biserka. 1992. Freske na fasadi glavne crkve Roženskog manastira kod Melnika. Zograf 22: 61–67. [Google Scholar]

- Pentcheva, Bissera. 2006. Icons and Power: The Mother of God in Byzantium. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Popovska-Korobar, Viktoriя. 2015. Dzidnoto slikarstvo vo crkvata na Slimničkiot manastir. Patrimonium, 209–48. [Google Scholar]

- Rahmani, Levi Yizhaq. 1993. Eulogia Tokens from Byzantine Bet She’an. Atiqot 22: 109–19. [Google Scholar]

- Salvador-González, José María Salvador. 2011. The Death of the Virgin Mary (1295) in the Macedonian church of the Panagia Peribleptos in Ohrid. Iconographic interpretation from the perspective of three apocryphal writings. Mirabilia 13: 237–68. [Google Scholar]

- Salvador-González, José María Salvador. 2017. Iconography of The Dormition of the Virgin in the 10th to 12th centuries. An analysis from its legendary sources. Eikon Imago 11: 185–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoemaker, Stephen. 2002. Ancient Traditions of the Virgin Mary’s Dormition and Assumption. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stilianou, Andreas, and Judith A. Stylianou. 1997. The Painted Churches of Cyprus: Treasures of Byzantine Art, 2nd ed. Nicosia: A. G. Leventis Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Subotić, Gojko. 1980. Ohridska slikarska škola u XV veku. Beograd: Institut za Istoriju Umetnosti, Filozofski Fakultet. [Google Scholar]

- Taft, Robert Francis, and Annemarie Weyl Carr. 1991. Dormition. In Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Edited by Alexander Kazhdan. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 651–53. [Google Scholar]

- Talbot Rice, David. 1966. Art of the Byzantine Era. London: Thames and Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Todorova, Rostislava. 2013. Visualizing the Divine: Mandorla as a Vision of God in Byzantine Iconography. IKON Journal of Iconographic Studies 6: 287–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorova, Rostislava. 2016. The Aureole and the Mandorla: Aspects of the Symbol of the Sacral from Ancient Cultures to Christianity. Studia Academica Sumenensia 3: 199–223. [Google Scholar]

- Todorova, Rostislava. 2020a. Simvol i znachenie: Kontseptat za Bozhiyata slava v kasnovizantiyskata ikonografiya. Shumen: UI Episkop Konstantin Preslavski. [Google Scholar]

- Todorova, Rostislava. 2020b. Sacred space on display: The place where God dwells and its visual representation. Acta Musei Tiberiopolitani 3: 121–33. [Google Scholar]

- Todorova, Rostislava. 2022a. From Word to Image: The “Hesychastic type” of Mandorla. De Medio Aevo 11: 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorova, Rostislava. 2022b. “Blachernitissa” or “Axion Estin”: On the name of the fresco of the Mother of God from Tomb E of the Chora monastery. De Medio Aevo 11: 253–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsámpouras, Theokháris. 2013. Ta kallitekhniká ergastíria apó tin periokhí tou Grámmou katá to 16o kai 17o aióna: Zográphi apó to Linotópi, ti Grámmosta, ti Zérma kai to Bourmpoutsikó. Didaktorikí diatriví. Aristotélio Panepistímio Thessaloníkis (APTh). Skholí Philosophikí, Tmíma Istorías kai Arkhaioloyías. Thessaloniki: Aristotélio Panepistímio Thessaloníkis (APTh). [Google Scholar]

- Tsigarídas, Efthímios, and Kátia Lovérdou-Tsigarída. 2006. Ierá Meyísti Moní Vatopaidíou. Vizantinés Ikónes kai Ependísis. Áyion Óros: Ierá Meyísti Moní Vatopaidíou. [Google Scholar]

- Underwood, Paul. 1966. The Kariye Djami. Vol. I. New York: Bollingen Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Velmans, Tania. 1999. Byzanz: Fresken und Mosaike. Zürich: Benziger Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, Elizabeth. 2007. Images of Hope: Representations of the Death of the Virgin, East and West. Religion and the Arts 11: 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitzmann, Kurt. 1976. The Monastery of St. Catherine at Mt. Sinai: The Icons. Vol. I. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wratislaw-Mitrovic, Ludmila, and Nikita Okounev. 1931. La dormition de la Sainte Vierge dans la peinture médievale orthodoxe. Byzantinoslavica III: 134–80. [Google Scholar]

- Yota, Elisabeth. 2021. Le tétraévangile Harley 1810 de la British Library. Contribution à l’étude de l’illustration des tétraévangiles du Xe au XIIIe siècle. Thèse de Doctorat, Université de Fribourg, Fribourg, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Todorova, R.G. The Mandorla Symbol in Byzantine and Post-Byzantine Iconography of the Dormition: Function and Meaning. Religions 2023, 14, 473. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14040473

Todorova RG. The Mandorla Symbol in Byzantine and Post-Byzantine Iconography of the Dormition: Function and Meaning. Religions. 2023; 14(4):473. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14040473

Chicago/Turabian StyleTodorova, Rostislava Georgieva. 2023. "The Mandorla Symbol in Byzantine and Post-Byzantine Iconography of the Dormition: Function and Meaning" Religions 14, no. 4: 473. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14040473

APA StyleTodorova, R. G. (2023). The Mandorla Symbol in Byzantine and Post-Byzantine Iconography of the Dormition: Function and Meaning. Religions, 14(4), 473. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14040473