1. Introduction

From 1998 to 2005, the once left-wing Protestant Dutch broadcasting company VPRO aired 26 episodes of

The White Cowboy. This cartoon series follows the adventures of the titular hero, which primarily consist of saving the imaginary Wild West town of Bullet Hole City, whose citizens do not seem to be able to live their lives without the constant interference of an outside hero. In one of the episodes, called ‘De Kerkgangers’ (Dutch for ‘The Churchgoers’), the White Cowboy arrives in Bullet Hole City (again), only to find the citizens greatly distressed (again), this time because of a newly arrived Protestant congregation. Its members dress in black, wear very serious faces, listen to their minister’s thunderous sermons (causing thunder and rainstorms to be unleashed onto the town) and sing very sad songs of hunger, death and sorrow. It is only when the White Cowboy switches the congregation’s black hymnals for a white version—clearly containing happier tunes to sing—that the problem is solved permanently. The White Cowboy closes, and even locks, the church’s doors saying: ‘The people have seen the light. The door can be locked’. The voice-over stresses the protagonist’s victory by insisting that ‘from that day on, Bullet Hole City was never troubled by churchgoers again.’

1The critical way that The White Cowboy addresses the phenomenon of religion in general and of a strict form of Dutch Protestantism in particular is unique in the cartoon series, since it is only this episode that explicitly deals with religious matters. Its depiction of strict Dutch Protestantism is a stereotypical one, stemming from the specific religious history and contemporary context of the Netherlands, which is—in turn—influenced heavily by the 16th century reformation. While this history could be summarized with the sociological term of ‘pillarization’ (see below), Dutch contemporary society is characterized by the opposite term of secularisation. The White Cowboy’s episode ‘The Churchgoers’ is a unique case study of both processes. If one wants to understand the particularities of Dutch society and the role religion played in it up until recent times, this episode is an interesting starting point.

Of course, ‘The Churchgoers’ is not the only Dutch example of a critical reception of the historical reformation in the Netherlands. Other examples include the critically acclaimed novel Knielen op een bed violen (‘Kneeling on a bed of violets’) by Jan Siebelink (2005), including its film adaption in 2016, Dorsvloer vol confetti (‘A Threshing-floor full of serpentines’) by Franca Treur (2009) or De Jacobsladder (‘Jacob’s Ladder’) by Maarten t’Hart (1986). While these and other literary criticisms are not devoid of humour or sarcasm, ‘The Churchgoers’ as a part of The White Cowboy series, is a comedy from start to finish. It is far less subtle than the novels mentioned above, much shorter, in a different medium (film instead of written literature) and was aired as a part of a children/young adult television show (I discuss this aspect later on in full detail). All these are reasons for choosing ‘The Churchgoers’ as a case study in the Dutch reception of the historical reformation.

In this article, I want to argue that ‘The Churchgoers’ is an excellent example of the contemporary reception of the 16th century Protestant reformation within the Netherlands at the turn of the millennium. Within the secular context of contemporary Dutch society, the stereotypical world-avoidance and lack of any joie de vivre associated with the strict observants of the Dutch reformation is used to mock Protestantism specifically and Christianity (or even religion altogether) in general. Nevertheless, a more positive interpretation also remains possible if one is able to understand secularism itself as a product of the Christian tradition to begin with.

By way of a theoretical framework, I start with providing background information on the reception of the 16th century reformation in the Netherlands, concentrating on the phenomenon of pillarization in the 19th and 20th centuries, as well as on the rise of secularism in contemporary Dutch society after World War II (

Section 2). Next, I introduce the case study, ‘The Churchgoers’, in detail, including its productional context within

The White Cowboy series (

Section 3). In the following four sections, I provide several analyses of ‘The Churchgoers’: a social–historical analysis (

Section 4), a communicative analysis (

Section 5) and a theological–religious analysis (

Section 6). I end with my conclusions.

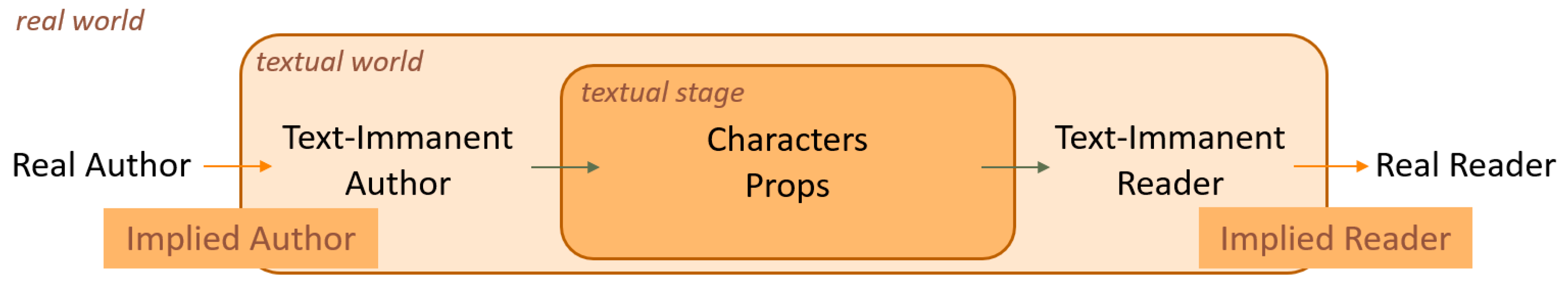

As a methodology, I used the communication-oriented analysis of texts (

Bosman and van Wieringen 2022; see

Scheme 1). This methodology makes a strict distinction between text-immanent communication (the communication within the textual world) on the one hand, and the text-external communication (the communication in the real world) on the other. This results in a strict distinction between the characters (and the accompanying props) on the textual stage and a text-immanent author directing these characters and communicating the narrative to a text-immanent reader. Outside the text, the real author and the real reader exist: the first communicates to the second by means of the text between them.

In the case of ‘The Churchgoers’, the real author is the series’ creator Martin-Jan van Santen (himself the son of a church minister) and his team, while individual consumers of the series’ episodes are the real reader(s). Only real readers are capable of a moral judgement, claiming the series and/or the episode to be—for example—offensive, beautiful or funny. The text-immanent reader is not; it is in perfect synchronicity with the text-immanent author, flawlessly understanding the intentions of the latter’s communication. In the case of ‘The Churchgoers’, the text-immanent author is identified—it is the voice-over telling the story—while the text-immanent reader is left unidentified. (When dealing with the narrative and communication analysis of the episode in

Section 3 and

Section 6, I argue that things are a bit more difficult than I have just suggested; for now, however, matters have been sufficiently explained.)

The fact that ‘The Churchgoers’ is, narratively speaking, a film-within-a-film, starring and watched by the same people, turns the episode into a collective moral narrative. The film shows what ought to be and how people should act and feel within that collective, that is, religion-critical and secularized. Taken into its Dutch context, the episode informs and enforces the film audiences’ self-identification (both of the embedded text’s viewers in the in-film ‘cinema’ and the basic text’s viewers in the real world) as secular. This self-identification is not only meant as being factual, but also as a moral imperative, as scholars such as

Jan Willem Duivendak (

2006) and

James Kennedy (

2009) have argued. And even more, other authors have voiced concerns about the problematic nature of this kind of framework, not per se in the Dutch context, but internationally (

Asad 2003), because of the inherent discriminatory characteristic of any dominant social mechanism.

Although the real author, who belongs to the real word, never coincides with the text-immanent author, who belongs to the textual world, and the real reader, who belongs to the real world, never coincides with the text-immanent reader, who belongs to the textual world, they are all, nevertheless, related. This relationship is mediated by a set of socio-historical data that makes the existence of both the text-immanent author and the real author on the one hand, and the text-immanent reader and the real reader on the other, plausible. Think of them, in short, as ‘paradigm builders’. In the case of ‘The Churchgoers’, these paradigm builders anchor things such as knowledge of the Dutch language, but also a certain literacy regarding various cultural receptions of, among others, the Wild West and the 16th century reformation. Without the stated cultural literacy, individual real readers would find themselves blocked from understanding the meaning of the episode.

2. Background: Reformation and Pillarization in the Netherlands

In 1566, the great iconoclasm of the 16th century swept the southern part of the Netherlands (coinciding with today’s southern provinces of the Netherlands, the northern parts of Belgium, known as the Flanders, and the northwest of France, known as the French Flanders): Calvinist-supported mobs destroyed Roman Catholic Church property in cities such as Steenvoorde, Antwerp and Brussels (

Duke 2003). It was by no means the actual start of the complex of movements that would eventually be known as ‘The Reformation’, but it was its most important catalyst; it carved the reformation into the collective historical memory of the Western world as a movement known for its piety and headstrongness (

Walsham et al. 2020), just as capable of being persecuted by others as persecuting others itself—an unfortunate characteristic early Protestantism shared with its primary adversary, the Roman Catholic Church (

Bonney and Trim 2006).

In 1648, the Peace of Münster was signed, ending the war of independence from Spain in favour of the northern Protestant rebels. One of the consequences of that treaty was that the Dutch Reformed Church (Nederlandse Hervormde Kerk; only named so since 1816) became the de facto (if not official) state church, more or less leaving other Protestant (predominantly Calvinist) denominations and Roman Catholicism to be the only one tolerated, or even to be persecuted (

Hagen 2013). From the late 16th century onwards, the Netherlands, in all its different political iterations, identified itself as a Protestant nation (

Ihalainen 2005;

van Sas 2005, p. 56;

de Kok 2007, p. 260), with the notable exception of the Catholic southern ‘Belgian’ parts (that revolted successfully in 1830 for independence), and the remaining southern Dutch provinces of North Brabant and Limburg. Increasingly, however, the Netherlands has not only become a secularised society, but the self-identification of the Dutch has become ever more one of having a secular identity.

This resulted in a dichotomy between the Protestant-dominated northern provinces of the Netherlands, collectively designated as ‘Holland’ (even though only two of the northern provinces carry that name), and the Roman Catholics of the two southern provinces, collectively known as ‘the South’ (

Janssen 2014). Even though Roman Catholics (and Protestants, other than those belonging to the Dutch Reformed Church) were given equal rights in the 1813 Dutch Constitution, the top positions in society were almost exclusively in the hands of those belonging to the main church.

Dutch Protestantism and its ecclesiastical history were dominated by Calvinism. This Protestant denomination was associated with a strict position regarding the Bible, an ascetic lifestyle and long and severe sermons during church service. These sermons, lasting for approximately an hour, formed the heart of the two services held every Sunday. And, although being a minority, the orthodox Calvinists are very well-known in the Netherlands for their particular way of life, their ethical views and their—manifoldly caricatured—church services. This group is also portrayed in The White Cowboy.

The 20th century gave birth to quite a unique religiopolitical phenomenon, for which the Netherlands would become world-famous, known as

verzuiling (‘pillarization’): a social process in which all parts of public (and often also private) life are regulated along religious and/or ideological lines (

Zanden 2015, p. 10). Schools, workers’ unions, newspapers, radio and television stations, political parties and all other aspects of human life were organized separately within four ideological “pillars”: the Roman Catholic, Protestant, socialist and liberal (

Bosman 2020). There is some academic debate about the causes of pillarization—whether it was the emancipation of the Protestant lower middle classes and Roman Catholics in the southern part of the country and/or elites imposing control upon the people in various denominational segments—but the result was a comparatively stable political system (

Lijphart 1968).

From the beginning of the 1960s, the traditional ‘pillarized’ society gradually disintegrated (

Halman 2010, p. 155). The Netherlands went from being ‘a fairly monochromatic’ Christian society to ‘one of dazzling diversity, tolerance and religious indifference’ in less than half a century (

Platvoet 2002, p. 83). Currently, the Netherlands is—and strongly self-identifies as—a secular nation. Several sociological surveys have shown a still continuing decrease in religious, confessional and denominational self-identification and church-attendance of Dutch citizens. In 2017, the Dutch Central Agency for Statistics concluded that for the first time in recorded history, more than 50% of Dutch citizens did not identify as belonging to any religious or ideological group (

CBS 2020).

The pillarization of Dutch society was also visible in the media: every pillar had its own papers, publishing houses, radio stations and television broadcasting companies (

Brants 2004). In 1930, the Dutch government introduced special rules for five different broadcasting companies, tied to the social pillars: the AVRO for the liberals, the VARA for the socialists, the KRO for the Catholics, and two Protestant ones: the NCRV (originally orthodox Protestant) and the VPRO (liberal Protestant) (

Harinck and Winkeler 2006, pp. 748–50). The fact that there were two broadcasters for the Protestant pillar, vis à vis one for the other pillars, was indicative of how complex the denominational structure of Dutch Protestantism had become (I return to this complexity later on in the article).

The VPRO—the organisation that aired The White Cowboy episodes—is a (historical) acronym for the ‘Vrijzinnig Protestantse Radio Omroep’ (Liberal Protestant Radio Broadcasting, since 1926) and formed the counterweight to the orthodox NCRV, another (historical) acronym for the ‘Nederlandse Christelijke Radio Vereniging’ (Dutch Christian Radio Society, since 1924). At the end of the 1960s, a new generation of content creators—the children of the Flower Power era—succeeded in deconfessionalizing the VPRO (losing the former dots between the letters) and started to create new and often (self-acclaimed) recalcitrant programmes, usually aimed at breaking (religious) taboos.

In 2019, the NCRV merged with the KRO (‘Katholieke Radio Omroep’, Catholic Radio Broadcasting, since 1925) to form the de facto secularized KRO-NCRV. The ‘gap’ for Protestant-denominational programming has since been filled up by the EO (‘Evangelische Omroep’, Evangelical Broadcasting, since 1967), known for its traditional and conservative Christian identity and ditto programmes (

Harinck and Winkeler 2006, p. 857). The EO and VPRO are still independent organisations.

3. The Case Study: The White Cowboy versus the Churchgoers

In 1984, the (no longer denominational–confessional) VPRO started to create programmes especially for children. The programme block—consisting of multiple independent programmes—was eventually named Villa Achterwerk, ‘Villa Backside’ in English, demonstrating the VPRO’s self-proclaimed air of ‘naughtiness’ and taboo-breaking. It is within VPRO’s Villa Achterwerk block that the total of 26 The White Cowboy episodes were aired between 1998 and 2005. The series was created by cartoonist Martin-Jan van Santen, produced by Animation World Studios in cooperation with the VPRO and funded by the ‘Rotterdam Fonds voor de Film en Audivisuele Media’ (Rotterdam Fund for Film and Audiovisual Media).

The series revolved around a hyper-polite Wild West hero-cum-cowboy, who saved the equally agreeable citizens of the fictional Bullet Hole City from greater and smaller disasters, ranging from art thieves to hurricanes. The protagonist was dressed exclusively in white cowboy attire. His nameless horse was completely white too, apart from the saddle and the reigns. He seldomly resorted to violence, but usually tried to outsmart his adversaries or the problem he faced. The White Cowboy seemed to draw, at least some, inspiration from the much more famous Belgian–American cowboy Lucky Luke, created by Morris (1923–2001) in 1946. Both wore a white hat, both had an intimate relation with their (very intelligent) horse and both almost never resorted to violence as (the first) option to resolve problems.

The episode ‘The Churchgoers’ was—as argued above—unique in The White Cowboy series, since it was the only one explicitly addressing religion. As per usual, the citizens of Bullet Hole City were having a great time enjoying themselves, each other and life in general. Even some (minor and major) forms of vandalism—ranging from crushing freshly planted flowers to burning down the neighbour’s house—could not stop them from being happy and polite.

All was peaceful and quiet, until—as the voice-over dramatically announced—on a random Sunday, the Churchgoers arrived, all dressed in black, marching in silence over the city’s main street, a stern-looking minister leading the way. When they entered the church, accompanied by the thunderous sounds of hitherto unknown bells, they started singing very sad songs about the horrors of being alive: ‘Hunger and sickness and death and sorrow’ was one of them. Also, the minister presented his congregation with a—quite literally—thunderous sermon about the sinfulness of human existence, which was immediately accompanied by a real-life thunderstorm.

The effect of these churchgoers (and the bad weather they seemed to attract) was that the formerly happy citizens of Bullet Hole City become grumpy and irritable, losing all joy in life and in their usual activities, including feeding horses, celebrating birthday parties and teaching at the primary school. Life itself became unbearable for everyone, except—apparently—for the churchgoers themselves, who were not identified as citizens of Bullet Hole City, but seemed to come from some unspecified ‘outside’.

‘The situation was without hope,’ as the voice-over described. It was at that moment that the White Cowboy arrived, and on seeing Bullet Hole City’s small church—the churchgoers having not arrived yet—the White Cowboy wanted to pay it a little visit, seemingly due to a tourist’s curiosity: ‘What a cute little church. Let us take a closer look.’ He is halted by a concerned citizen who warned the unknown and unknowing stranger about the impending ‘danger’. The citizen and some of his friends tried to prevent themselves from falling into a depression, because of the churchgoers, by telling (rather silly) jokes to one another.

The churchgoers arrived, the songs were sung (‘we are doomed’) and the sermon began (‘we will burn’), resulting in pouring rains outside. The cowboy thanked the citizens—who had fallen into apathy—and entered the church to investigate the situation. Comprehending the depressing nature of the service, the cowboy managed to swap all the black hymnals used by the congregation for white ones (‘my favorite ones,’ he called them) during a very short black-out.

When the congregation sang (the cowboy’s version of) Hymn 38, they did not mutter about the world’s doom, but expressed feelings of joy, ending in a gleeful parade of churchgoers leaving the church, including a whistling and dancing minister. The White Cowboy closed the doors of the church saying: ‘The people have seen the light. The door can be locked.’ The voice-over commented that the city returned to normal, happy life ‘never to be troubled by churchgoers again’. The protagonist mounts his horse and rides away toward the horizon on his way to new adventures.

From a narrative point of view, the episode could be easily divided into two parts, each consisting of—again—two parts. The first part of the episode was the ‘set-up’ of the story told, including (1.1) the introduction of the town and its happy atmosphere and (1.2) the introduction of the impending conflict-to-be-resolved, in casu the churchgoers and their bad effects on the town’s overall happiness. The second part was the resolution of the problem, including (2.1) the arrival of the outside hero, mirroring the outside origin of the problem, and (2.2) the solution itself by removing the outside threat to restore the former status quo.

4. Social–Historical Analysis: The ‘Black Stockings Churches’

The churchgoers of Bullet Hole City were a clear-cut parody of what in the Dutch context is known as the ‘Black Stockings Churches’ (

Zwarte Kousenkerken), a stereotypical and often derogative container notion for conservative, Calvinist churchgoers in the so-called Dutch ‘Bible Belt’. This swathe of land runs from the southwestern province of Zeeland to the north-east of the province of Overijssel, forming a ‘belt’ from west to east, cutting the country into a northern and a southern part. These Protestants bear this name because of the specific black clothing they are supposed to wear to Sunday church (

Taussig 2009, pp. 135–58). Especially the women, clothed in black or traditional attire, including the black stockings and head coverings, are a well-known manifestation of the orthodox Calvinists.

In popular speech, the members of these ‘Black Stockings Churches’ are referred to as Refos, short for Gereformeerden. The English translation of the latter is quite difficult and closely connected to the highly complex structure of Dutch Protestantism. What is referred to in popular speech as ‘Black Stockings’ or Refos can denote devotees from several Protestant denominations. The majority of these denominations use the words hervormd or gereformeerd in their name, both translated in English to ‘reformed’.

The Dutch Calvinist church history is very, very complex. To attain a general insight into the situation of Calvinist churches in the Netherlands, three major ‘blood groups’ should be distinguished: the main church (‘Dutch Reformed Church’,

Nederlandse Hervormde Kerk, also referred to as the ‘Reformed Church’) and two kinds of so-called ‘separated churches’, namely, the ‘neo-Calvinists’ and the ‘pious reformed’, both of which separated from the main church in the 19th century. The Dutch Reformed Church arose out of the reformation in the 16th century. Constituted in the German city of Emden in 1571 (

Selderhuis and Nissen 2006, pp. 312–13), it became the established Church of the Netherlands during and after the Independence War, the eighty-year war against the Catholic Spanish Empire. The Synod of Dordrecht (1618–1619) was decisive for the doctrine, ecclesiastical practice and unity of the Reformed Church. It was stated to be a Calvinist Church with officially confirmed Calvinist points of doctrine (

van Asselt and Abels 2006, pp. 428–31).

Albeit officially a Calvinist Church, there have always been many theological disputes and struggles within the Dutch Reformed Church about various dogmatic issues concerning the Bible, Jesus and the Church. The many differences existed side by side within the Church, although, over time, particular congregations associated with one of the various factions. Due to these struggles, many people left the Dutch Reformed Church in the 19th century, in the separation of 1834 and the ‘Doleantie’ (‘Grievance’) of 1885 (

Harinck and Winkeler 2006, pp. 633–35, 680–84). Nevertheless, orthodox congregations also continued to exist within the Dutch Reformed Church (

Rasker 1974, pp. 262–66).

The leavers founded new congregations and denominations. Over the 19th century, the separated churches split in two ‘directions’: the neo-Calvinists and the pious reformed. The neo-Calvinists tried to bring the old Calvinist truths and the new modernism together. They were strong organizers and started to form a new church federation (

Gereformeerde Kerken in Nederland, ‘Reformed Churches in the Netherlands’). From the beginning, the neo-Calvinists were orthodox in doctrine and way of life. They were known as being strict cognitive-orientated (

Harinck and Winkeler 2006, pp. 687–90). After the 1970s, these churches radically changed. They rapidly and massively embraced liberal values, so detested by their ancestors (or to use a typically reformed term, ‘the fathers’). Nevertheless, the predicate

gereformeerd retained an association with the strict Calvinist religion and lifestyle.

The ‘pious reformed’, on the other hand, were the other blood group of the Separated Churches. They could best be seen as a family of churches. They also wanted to return to the ‘old Truth’ of Calvinism. They differed from the neo-Calvinists in their focus on an experience-orientated faith, and their view on personal conversion. They were strict confessors of the concept of pre-destination, meaning that God had decided from eternity who would

and who would not be redeemed, so before we were even born. Till this day, the pious reformed form a prominent subculture in Dutch society. Traditionally less organized than the neo-Calvinists, they are, nowadays, more organized, forming the ‘last pillar’ of Dutch society. These reformed are still known for the strict adherence to their faith. When secularization broke through into Dutch society, this sub-group became more and more prominent, and the gap between them and ‘modern society’ started to grow (

Harinck and Winkeler 2006, pp. 886–87). This was caricatured in

The White Cowboy.

Again, from an insider’s perspective, these different denominations could differ substantially from one another in terms of dogmatics, ethics and opinions concerning the outside world and the place of ‘the Church’ within it, but for an outsider, many Protestants—especially those of a more conservative opinion—are more or less the same. These are the above-mentioned Refos: people who adhere to a puritan-like Calvinism, with a main focus on a strict and literal interpretation of the Bible, as well as a focus on inner piety; a small group of Dutch Protestants, far less unified than the other denominations, who focus on a personal and experienced relationship with God. These bevindelijken act as a pars pro toto for the whole of (orthodox) Dutch Protestantism.

It is clear that The White Cowboy targeted these broad, stereotypical Refos. The clothes the churchgoers wore were exclusively black and of a humble style. The headgear was especially telling. The look on their faces and their overall mannerisms were that of sombre, somewhat boring and heavy-hearted Christians, who were very well aware of their sinful constitution, its unavoidability and the knowledge that God had already passed judgement upon every one of them (pre-destination). They sang sad-sounding, melancholic songs using whole notes (avoiding the frivolousness of half-notes, let alone quarter notes) about how bad humanity’s condition is in the eyes of the Almighty, accompanied by a heavy-handed organ.

When the minister—himself a statue of sternness, bordering on anger—started his sermon, a thunderstorm appeared as the physical representation of a ‘thunderous sermon’ (donderpreek), in which sins, eternal damnation and the ineffectiveness of human endeavours were stressed. The outside perspective on the Refos also had its own place in the episode: the churchgoers came from outside Bullet Hole City, they were foreigners, alien to the social fabric of the town. And when the church doors were closed by the White Cowboy, they vanished from the city as if they had never been there. What came from the outside had returned to the outside: a perfect, if hostile, depiction of the Refos as not being a ‘real’ part of Dutch society.

On the other hand, some details were not correct. The men kept their cowboy hats on during the service, which is strictly forbidden in the pious reformed congregations. Most women in the church of Bullet Hole City did not wear a hat during service, while wearing a head covering is exactly what the authentic pious reformed women are supposed to adhere to (based on a specific interpretation of 1 Corinthians 11). The outside of the cartoon church was 19th century Wild West style, while its interior resembled that of a 15th or 16th century Dutch Calvinist church. Prominent is the pulpit, placed at the centre of the church. After the introduction of the white hymnal, the hands of the churchgoers went up in the air waving, resembling a practice found not in pious reformed tradition, but rather in Evangelical ones. These Evangelical congregations are a major competitor of the Calvinist ones, especially among the youth.

It looked almost as if the writer of these scenes was inspired by the stereotypical Refos, but was more knowledgeable about, and probably raised in, a ‘regular’ Dutch Reformed Church tradition. The writer knew a lot of details, but failed in a number of minor details, which, ultimately, betrayed an outsider’s perspective regarding the context of the pious reformed.

5. Communication Analysis: What about These ‘Men’?

From a communications perspective, the episode had some very interesting characteristics. To start with the first, ‘the Churchgoers’ episode was a frame story, as were all instalments of the series. Every episode started with the citizens of Bullet Hole City hurrying themselves to the city’s square, where a large projector then started showing the actual episode on a giant screen for everybody to enjoy. At the end of every episode, the film in the square would end with a classic ‘The End’, leaving the citizens to clap and shout in enjoyment and—apparent—agreement with what they had just witnessed. This embedding of one story in another is known as a Matryoshka (see

Scheme 2), named after the famous Russian doll (

Bosman and van Wieringen 2022).

Secondly, the series contained a very special moment for the introduction of the White Cowboy. In the middle of every episode—after the aforementioned phase of the ‘set-up’ and ‘the conflict’—the protagonist was introduced by the unseen voice-over, the episode’s text-immanent author, as follows: ‘The situation was without hope, until the White Cowboy appeared. There he was, sitting on his loyal horse, ever ready to help humanity.’ Then, the voices of the narrator (the text-immanent author) and the protagonist (the character ‘the White Cowboy’) would intertwine, as in the case of ‘The Churchgoers’:

| Voice-over: | It was Sunday and the White Cowboy had taken a day off. |

| White Cowboy: | Sunday… |

| Voice-over: | He said… |

| White Cowboy: | …a day to take off. What a cute little church. Let’s take a closer look. |

The communicative suggestion was the establishment of a natural bond between the text-immanent author and the main character, the White Cowboy. The story’s protagonist seemed to function as an extension of the text-immanent author’s ideas and opinions, possibly up to the point where the White Cowboy indirectly voiced the text-immanent author themselves.

Thirdly, when the White Cowboy switched the black hymnals for the white ones, the minister violently told his congregation (twice actually) to sing Hymn 38. Unfortunately, we did not know what the ‘black’ version of the Hymn was; the ‘white’ version was heard loud and clear:

‘Come and play outside, because outside the sun is shining. And we will do a circle dance on my balcony. Sing a jolly tune and dress in something bright. And everyone inside should go outside.’

Hymn 38 could very well be a reference to Psalm 38 in the

Songbook of the Churches (

Liedboek van de kerken) published in 1973 and used by the Dutch Reformed Church (‘Nederlandse Hervormde Kerk’), the Reformed Churches in the Netherlands (‘Gereformeerde Kerken in Nederland’) and the united Protestant Church in the Netherlands (‘Protestantse Kerk in Nederland’). In 2013, this last one issued a new version, called

Songbook. Singing and praying at home and in church (in Dutch:

Liedboek. Zingen en bidden in huis en kerk). I quoted the first two strophes of this Dutch Hymn 38 in my own English translation:

2Do not let your wrath consume me, oh LORD, do not punish me, oh, do not punish me.

Because your hand lies upon my life. See me trembling before the arrows you shoot.

LORD, I cannot get any rest because of your threatening, only dissatisfaction is my share.

My existence became one wound. By my sins, no part of my body was left unbroken.

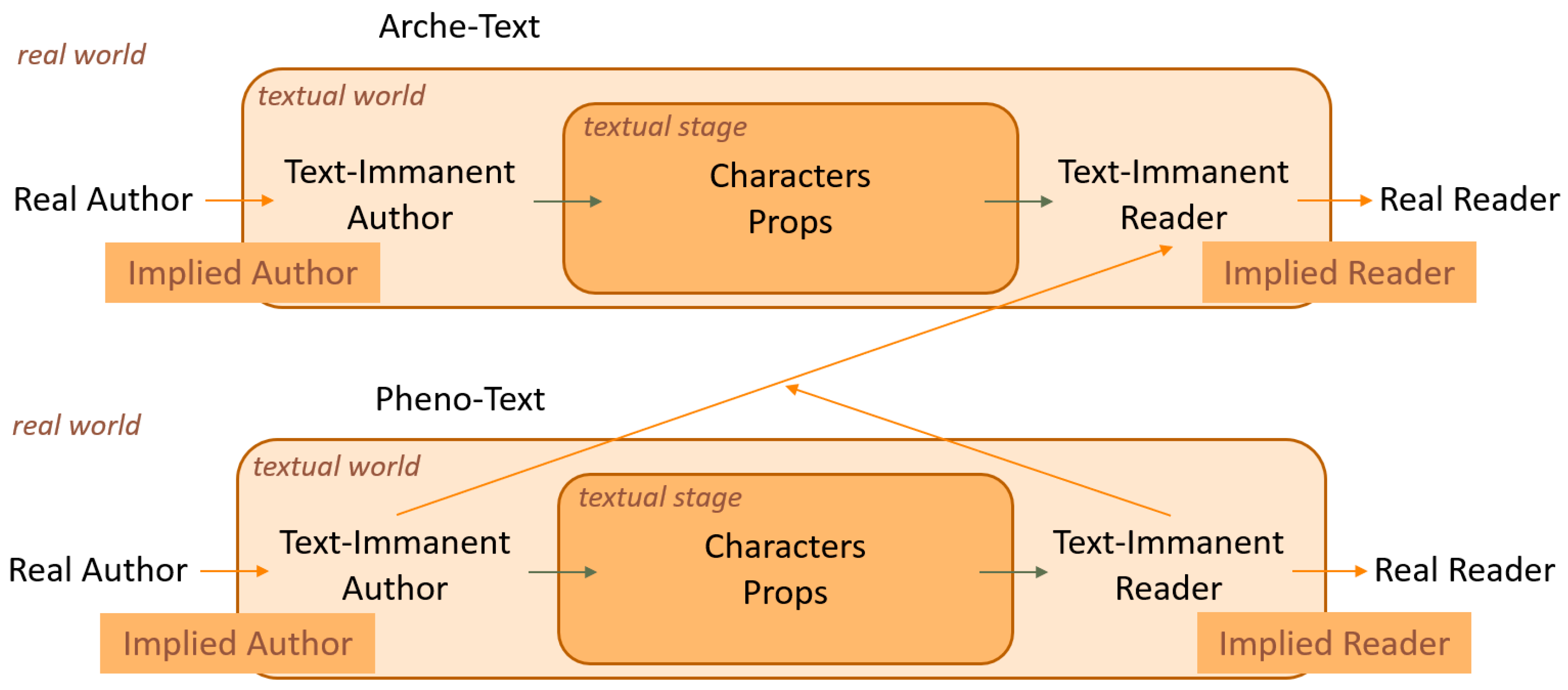

In communication terms, this is a form of inter-textuality (

Bosman and van Wieringen 2022; see

Scheme 3). In the case of inter-textuality, an older text (called an ‘archè-text’) is quoted by a newer one (called a ‘pheno-text’). The text-immanent reader of the archè-text, in this case the Dutch Psalm/Hymn 38, is equal to the text-immanent author of the pheno-text, in this case ‘The Churchgoers’. The text-immanent reader of the latter text (the episode of

The White Cowboy) has to (and does) understand the relationship between the two texts.

In our case, the relationship between Psalm 38 in its Songbook version and ‘The Churchgoers’ was relatively easy to establish. The ‘I’ (including the ‘me’ and ‘my’) in the Psalm/Hymn plays the role of the text-immanent author, who pleads for his life before his God. In ‘The Churchgoers’, the ‘I’ (through the inter-textuality) was transferred to the collective of characters of the congregation members singing Hymn 38. The text-immanent reader of the episode would understand this perfectly: this strengthened the stereotypical image of the Refos as heavy-hearted, pessimistic and sombre Christians, wailing during Sunday services about the fact that God had felled them with his arrows.

As I argued earlier, the author of ‘The Churchgoers’ did not have all the details of the pious reformed tradition clearly in their mind. The word ‘song’ was not appropriate for the pious reformed, who exclusively use the Psalter from 1773 that does include songs—beside the 150 Psalms of the Old Testament—although not a number 38.

The fourth, and possibly the most important, communication point is an anomaly, which to understand one must be familiar with the Dutch language, specifically the way the Dutch use the indefinite pronoun

one. When the voice-over (the text-immanent author) (in Section 1.1) described how the citizens of Bullet Hole City enjoyed themselves, the Dutch indefinite pronoun

men (‘one’) was used in a context that is impractical for the English language:

| Dutch: Men maakt elkaar liever aan het lachen (…) men schildert een vrolijke prent (…) of men fluit een vrolijk deuntje. |

| English: Men rather make each other laugh (…) men paint a cheerful painting (…) or men whistle a jolly tune. |

Translating the Dutch

men as ‘one’ is rather strange; ‘the people’ or ‘they’ would be better. Nevertheless, the use of

men was significant, since it suggested the collectivization of the text-immanent author

and the text-immanent reader of the episode. This would become even more apparent in the solution to the conflict (in Section 2.2), when the White Cowboy closed the church’s doors:

| Dutch: Men heeft het licht gezien. De deur kan op slot. |

| English: Men have seen the light. The door can be locked. |

We do not know yet exactly what ‘the light’ that was apparently seen denoted, but we do know—because of the men—that it concerned something that both the text-immanent author and the text-immanent reader of ‘The Churchgoers’ actually share. The men communicated something on the level of the text-immanent author and the text-immanent reader, not on the level of the characters alone.

6. Theological–Religious Analysis: Jesus as the White Cowboy

The interpretation of what this ‘light’ might be and how it is relevant to the text-immanent reader are the next questions that beg answers. Light is associated with knowledge, and since the Enlightenment (what is in the name!), increasingly exclusively with

empirical knowledge (

Sitelman and Sitelman 2000). As theologians such as

Chan (

2003) and

Goris (

2009) have demonstrated, the notion of reductionism shifted from a purely methodological instrument (we can only scientifically study what we can verify empirically) via an epistemological standpoint (we can only know what we can verify empirically) to a full-fledged metaphysical statement in itself (only what we can verify empirically is knowledge). The problematic part is, of course, that this metaphysical position is unable to prove its own philosophical axioms.

Within the context of The White Cowboy—including the secularizing history of the broadcaster VPRO—specifically and within the broader secularized context of Dutch contemporary society, in combination with the stereotypical depiction of the Refos, the episode’s message appeared to be an ultimately religion-critical one. The White Cowboy arrives in Bullet Hole City on a Sunday and wants to visit a local church, not for religious or pious reasons—in contrast to the ‘real’ churchgoers—but as a form of leisure and tourism. For the White Cowboy religion is something belonging to the past, a relic of a now already defeated part of history when ‘people’ used ‘to do’ religion. For our protagonist, the church was foremost, and perhaps even exclusively, a building in the sense of a museum: nice to visit, but without any metaphysical relevance.

The light (and implied darkness) metaphor is also applied regarding the clothing of the protagonist and the antagonists: the White Cowboy is—as his name suggests—dressed completely in white clothes, while the

Refos dress equally exclusively in black. And even though in recent times the ethnic and ethnical dimensions of colours and their appropriation in the cultural and political domain have been under scrutiny (

Stubblefield 2005;

Zack 2015), white was (and perhaps still is) associated with righteousness and heroism, while black is the indicative colour for evil and wickedness. The colours communicated that the text-immanent reader should be very well aware, from the start, that the churchgoers are wrong and that Bullet Hole City is in desperate need of a hero.

The White Cowboy closing the church doors meant the old status quo was restored, that is, a situation in which religion did not play any significant part in public or private life and in which the pacified (because defunct) church building was the only remainder and reminder of what once was. Religion is alien to ‘our’ world; its only function to darken everybody’s mood by continuously talking about a vengeful God. It was people who brought this religion into our world, and the best thing we can do is to be rid of it again. The world would be all the better for it, as famous atheist Richard Dawkins argued in his seminal The God Delusion (2006). Or: ‘Imagine there is no religion,’ as John Lennon famously wrote in 1971.

It is as the voice-over (text-immanent author) concluded: ‘From that day on, Bullet Hole City was never troubled by churchgoers again.’ And that is a good thing, according to the text-immanent author of ‘The Churchgoers’. This also shed new light on the men who finally saw the light: we have. Because of the use of the Dutch indefinite pronoun men, the message of the episode was that its readers should close the door on religion too, liberated by the secularism of the White Cowboy. Of course, individual real readers of ‘The Churchgoers’ may or may not hear this message and may or may not change from religious die-hards into full-blown atheists; the text-immanent reader, however, does not have that luxury, because of its perfect understanding of the text-immanent author’s communication.

There is one other possible theologically more positive interpretation of the episode. It stretches the imagination somewhat, but the white-clad Cowboy who closes the doors of the church could be interpreted as a metaphor for—quite paradoxically—Jesus Christ himself. Just like his supposed New Testament counterpart, the Christ (from the Greek for the Hebrew ‘Messiah’, meaning ‘the anointed one’), the episode’s protagonist is not known by his given name, but by his title, indicative of his innermost identity: the White Cowboy.

The post-Paschal Jesus and his messengers appear to the disciples dressed in white or light clothes (Mathew 28: 3; Mark 16: 5; Luke 24: 4), just like the White Cowboy. Both arrive ‘from outside’ to save humanity from an immanent disaster. And both disappear as soon as they have served their ultimate purpose. The White Cowboy’s closing of the church doors was then a reference to the idea of Christ’s return at the end of times to end life as we know it, including religious life. Just like at the resurrection, one is not married or given into marriage, as Mathew 22:30 describes, one no longer needs weekly church services to praise God.

However, such a theological interpretation might be thought of as over-stretching the narrative. Even though this might be understandable, I would like to argue in favour of maintaining this interpretational possibility by pointing out that secularisation itself has been seen as a product of Western Christianity itself. As scholars such as

Charles Taylor (

2004) and

Prosman (

2011) have argued, the profane–sacred distinction has always been a part of Christianity, also in its pre-modern iterations: the necessity to distinguish between the state and the church. If the White Cowboy was to be understood as a stand-in for Christianity, the closing of the church’s doors would be nothing but an expression of the idea that Christianity has produced secularism, and, therefore, dug its own grave, so to speak. The White Cowboy, as an image of a secularised but still (in that sense) Christian culture and society, makes obsolete what had created it in the first place.

7. Conclusions

The episode ‘The Churchgoers’ is an interesting example of a specific kind of contemporary reception of the 16th century reformation in the Netherlands. The reception incorporated the following ingredients, of which three were historical and four contemporary. To start with the first category:

The White Cowboy in general and the episode ‘The Churchgoers’ specifically took place in a pseudo-Wild-West setting, but the language used in the episode and the interaction with the religious congregation were clearly based on a Dutch setting, including its ‘Black Stockings Churches’. The historical and geographical foreign setting barely hid this fact. Also, the episode’s inspiration could not have come from anywhere else in the Protestant world, since the Netherlands—especially in its phase when contemporary Belgium was still a part of the kingdom—was at the geographical and political heart of the historical reformation, including its collective Protestant (self)identification. And last but not least, the episode also showed the—historically anchored but contemporarily still relevant—plethora of Protestant churches and denominations that complicated historical ties to one another, and, in one way or another, all sprung forth from the original reformation. Of course, this plethora is also apparent in other parts of the world, but nowhere more densely and intricately than in the Netherlands: the land of the thousand-and-one churches.

If we turn our attention to the contemporary ingredients, we would see that, in contemporary Dutch society, especially in its new collective (self)identification as a secular nation, the right-wing, conservative Refos, have become the cultural go-to stereotype of Protestantism specifically, Christianity in general and even the religious phenomenon per se. Next, the Refos have become the pars pro toto or stand-ins for religion and its unpopular (attributed) features, such as humble and plain (black) clothing, overall sombreness, the inability to appreciate beauty and humour, ditto singing, thunderous sermons, being out of touch with ‘real life’ and a strong dichotomy between the sinful world outside and the safety of the own religious group. Moreover, the secular paradigm of the series and the episode was also apparent from the nature of the solution given to the city’s problems with the churchgoers: the (although peaceful) elimination of all forms of religion from society. This solution was not only suggested within the episode to the poor citizens of Bullet Hole City, but was also offered to the viewers of the episode. It is not only in the cartoon world that the removal of religion be beneficial or even necessary for the happiness of the population, but the same applies to the real world outside the textual world of the cartoon.

The reception of the 16th century reformation in contemporary Dutch society was, in the case of The White Cowboy, a dismissive one: religion is an important part of the collective history and former (self)identification, but without any present-day relevance. Christianity specifically, and religion generally, can for the better be discarded altogether, having outlived its usefulness, if it ever had any in the first place.