Religiosity and Misanthropy across the Racial and Ethnic Divide

Abstract

Misanthropy develops when one puts complete trust in somebody, thinking the person to be absolutely true, sound, and reliable, only to later discover that the person is deceitful, untrustworthy and fake. And when this happens to someone often … they end up … hating everyone.––Attributed to Socrates in Plato’s Phaedo

1. Introduction

2. Background and Literature Review

2.1. Race, Ethnicity, and Misanthropy

2.2. Does Ethnic Diversity Erode Social Trust?

2.3. Are Blacks and Latinos Less Trusting (More Misanthropic) Than Whites?

2.4. Explanations for Why Blacks and Latinos Are Less Trusting (More Misanthropic) Than Whites

2.5. Religion and Misanthropy

2.5.1. Positive Association

2.5.2. Negative Association

2.6. Race, Ethnicity, Religiosity, and Misanthropy

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Dependent Variable

Misanthropy and Its Constituent Parts

3.2. Focal Predictors

3.2.1. Race/Ethnicity

3.2.2. Focal Predictors: Two Dimensions of Religiosity

3.2.3. Controls

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics: Mean Racial and Ethnic Differences in Key Variables

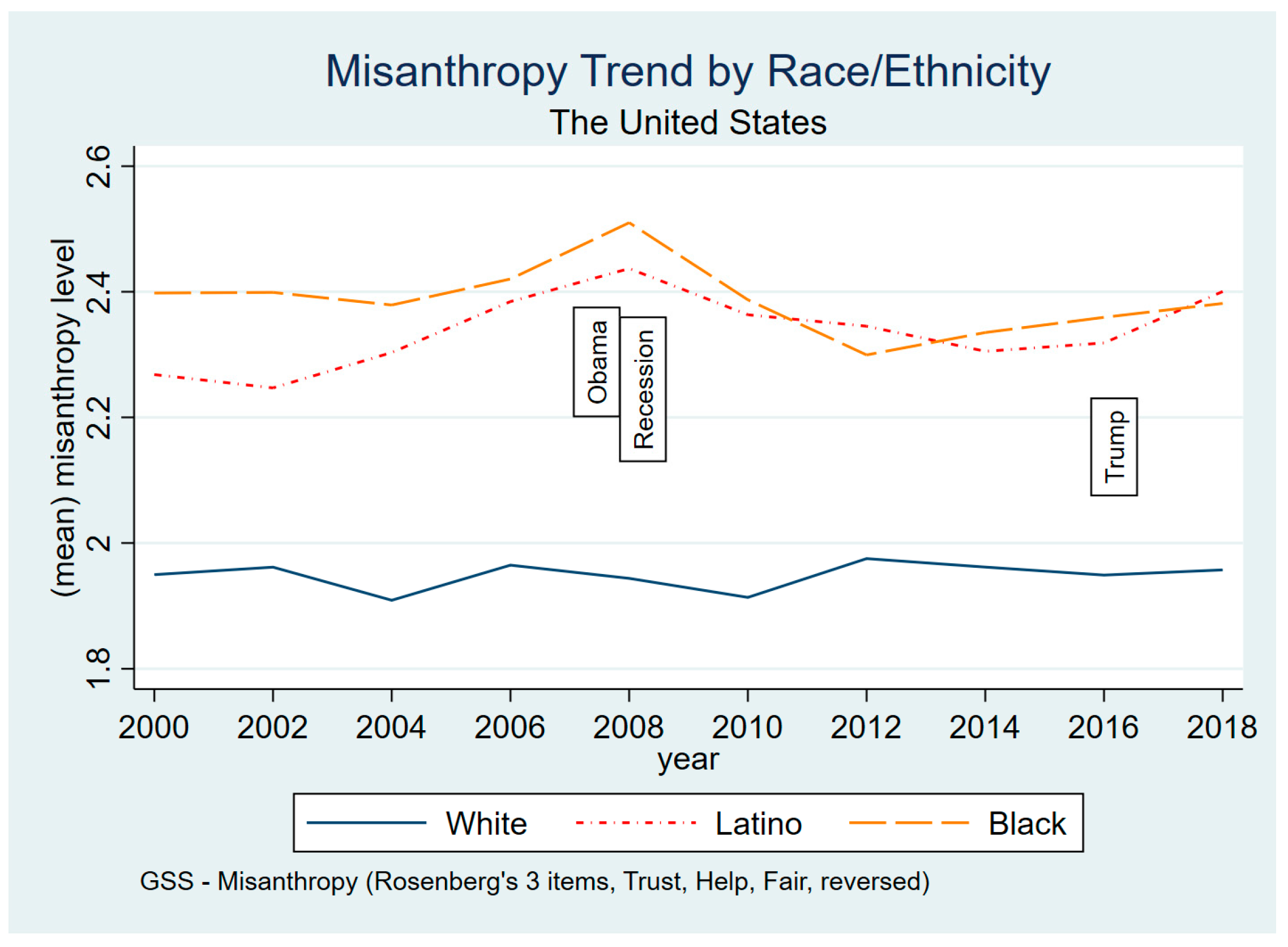

4.2. Ethnoracial Trends in Misanthropy

4.3. Multivariate Analysis: Net of Controls

4.3.1. Trust, Helpful, and Fair

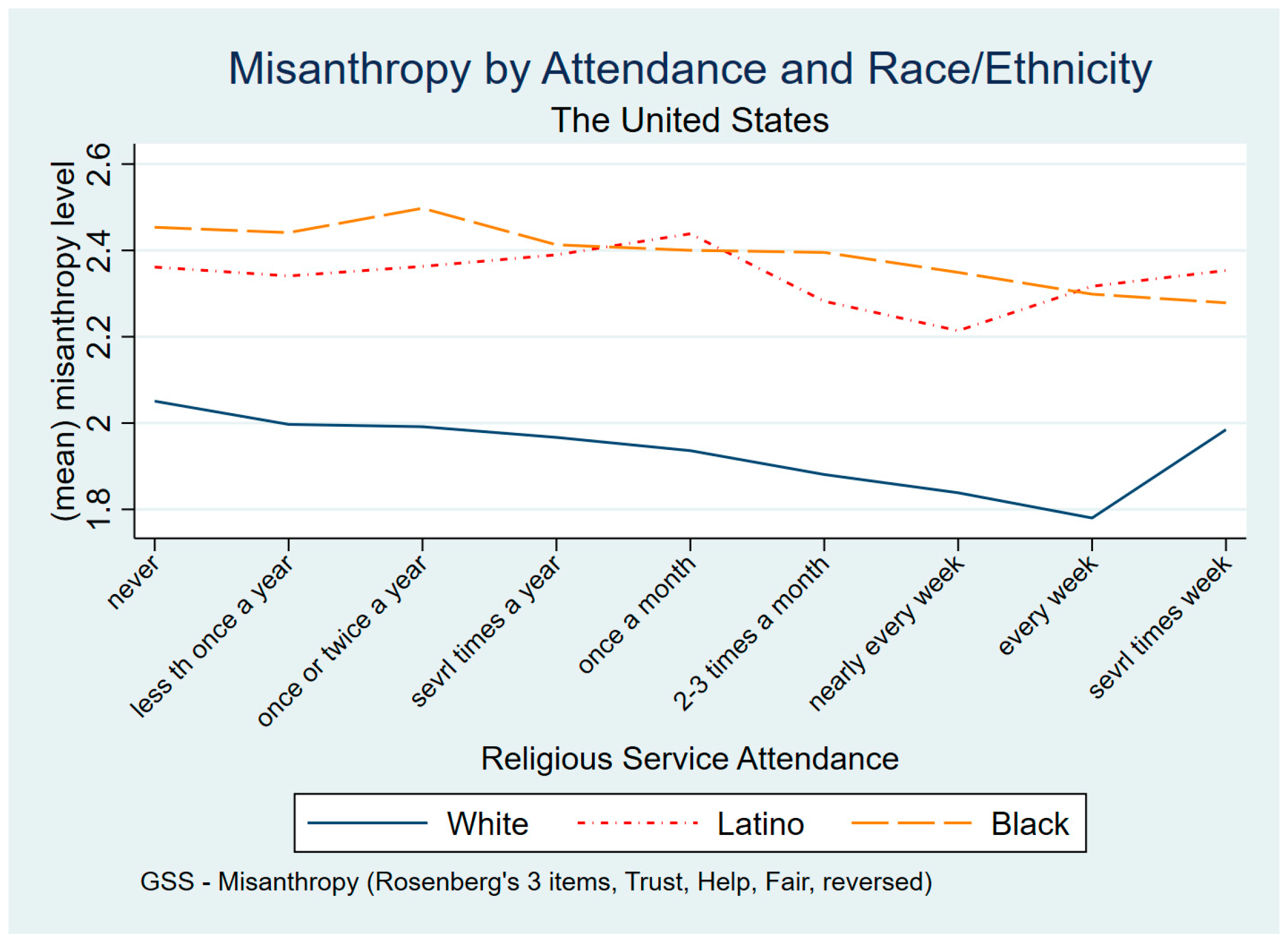

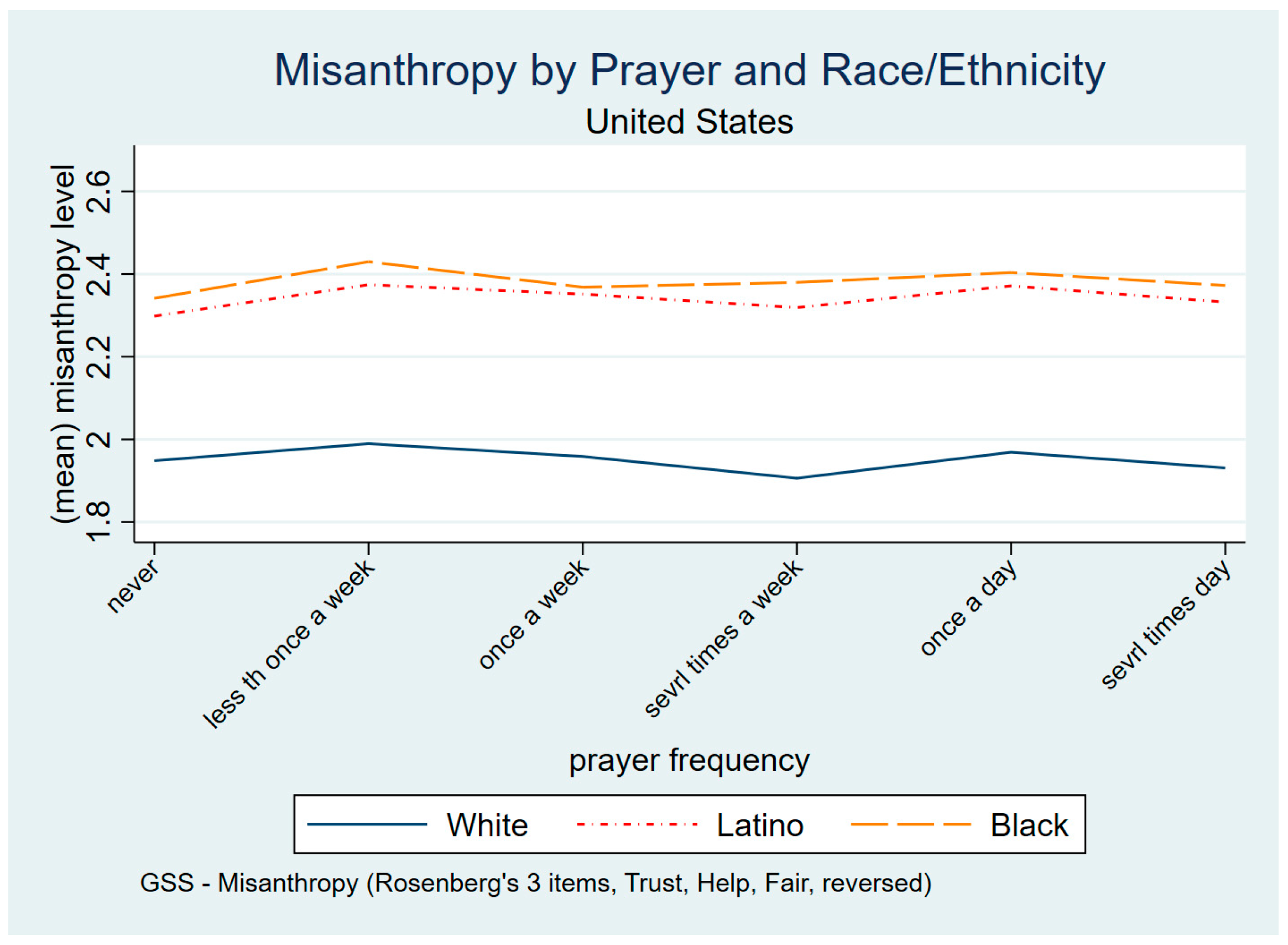

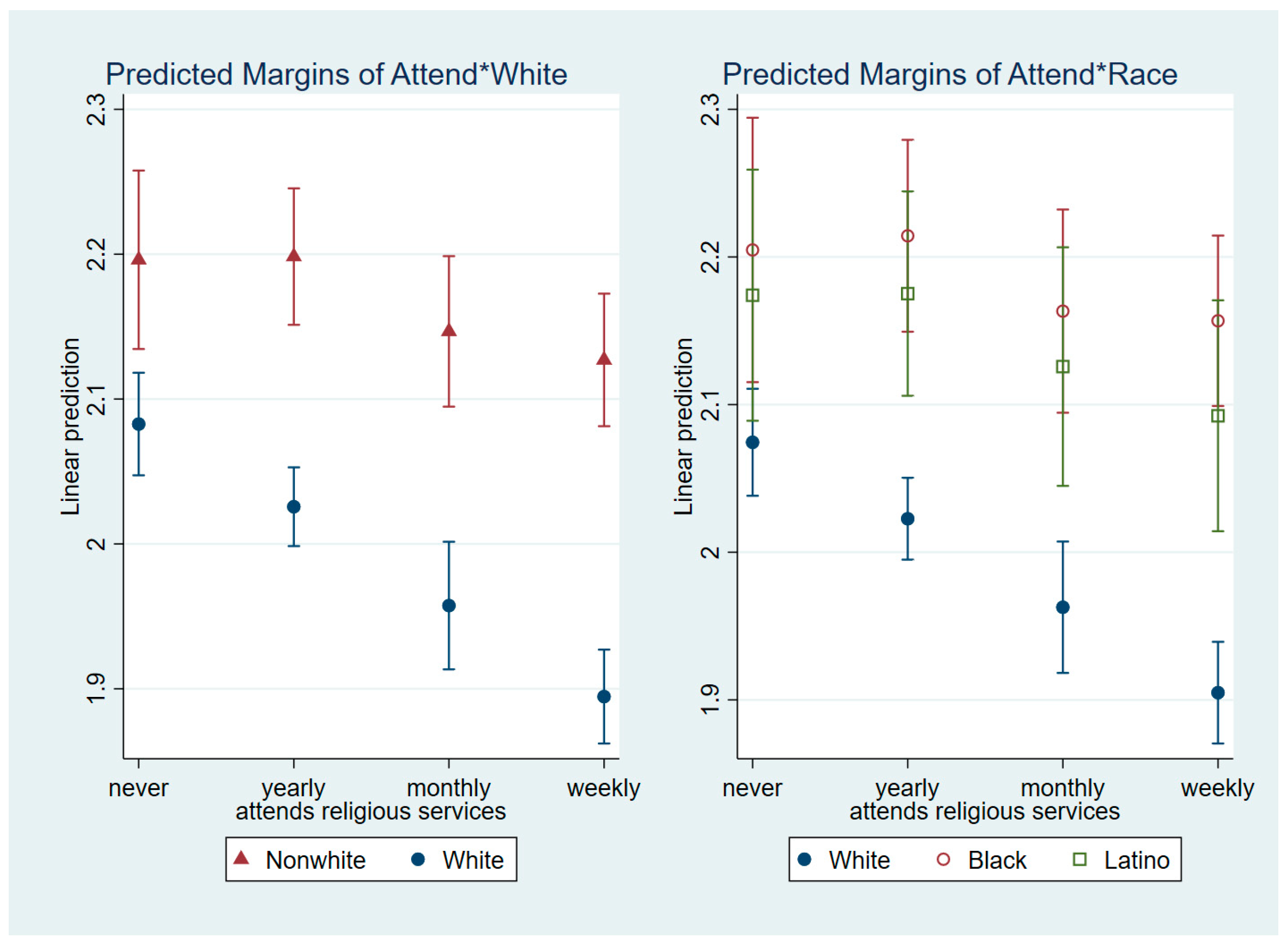

4.3.2. Race, Ethnicity, Religiosity, and Misanthropy

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Another important track addresses why trust levels vary across countries and states (Berggren and Bjørnskov 2011; Delhey and Newton 2005; Uslaner and Brown 2005). |

| 2 | Although some Latinos might not be Hispanics (e.g., Brazilians), we use these terms interchangeably throughout this paper. |

| 3 | |

| 4 | There is, however, some dissent on this issue. Simpson et al. (2007) argue that prior studies employ a “standard trust measure” that is ill-equipped to properly capture racial variation in trust. Using an experimental design with university students as participants (98 Whites, 49 Blacks), the authors found evidence in support of their hypothesis that “trusting behavior will be higher within race categories than between race categories” (p. 531). However, their results, based on students from a single university, is not representative of the U.S. population. |

| 5 | In this context, it is important to recall that the American Civil Rights Movement grew out of and was sustained by the Black church. Indeed, many of the Civil Rights Movement’s high-profile leaders were pastors and preachers, including Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Jesse Jackson, and later, Al Sharpton, to name a few. In addition, the foot soldiers of the movement were largely comprised of rank-and-file church congregants, but also students who came from religious households (see Dickerson 2005; Morris 2014; Harvey 2016). |

| 6 | We are aware that this procedure is a rudimentary approach to understanding the role of trust in the Bible, given that trust can be conveyed without actually using the word itself. However, the exercise does give us some insight into how Christians encounter the idea of trust in a biblical context. |

| 7 | It is important to highlight though that a central Christian tenet “to love others as we love ourselves,” is incongruent with misanthropy. |

| 8 | In Welch et al. (2007), religiosity was measured by activity in religious congregations, belief in absolute morality, frequency of prayer, and belief in the sinfulness of human nature. |

| 9 | This generalized measure has been widely used in social science research in the U.S. and cross-nationally, but it is not without its limitations (Delhey et al. 2011). Chief among them relates to how broad a circle survey respondents imagine when responding to the prompt “most people.” This is the so-called “radius of trust problem”(Delhey et al. 2011; Welch et al. 2007). Like others, we are assuming that our measure of misanthropy conjures a wide radius of people in the minds of respondents mainly because, according to (Delhey et al. 2011), “the radius of most people” in rich countries like the United States and non-Asian countries, tend to be wider than that found in poorer countries and countries with a Confucian background. |

| 10 | The “other” category was not included in the analysis given its small sample size and the fact that it is impossible to know what racial categories comprise the variable (e.g., Asian, Native American, Middle Eastern). The final sample only included respondents who were White, Black, or Latino. |

| 11 | For comparison purposes, we also conducted an analysis using the ethnic variable, and the results (not shown) were comparable. |

| 12 | Even though “Hispanic” is an ethnicity and not a race, given the small number of respondents who claimed to be Hispanic and Black (N = 153), we decided to look at all Hispanics irrespective of whether they self-classified as White, Black, or other. Out of 3549 Hispanic, 50.92% claimed to be White, 4.31% to be Black, and 44.35% to be “other” (the majority of which are likely to be “mixed” or “brown”). |

| 13 | Additional robustness tests examined belonging to a Christian denomination and found significant interactions for Blacks who are Lutherans, Hispanics who are Presbyterian, and other races who are Methodist and other denominations. However, the cell counts were too small to sustain meaningful analyses (e.g., fewer than 30 people who were Black and Lutheran). We also ran additional tests looking at religious organizations and belief in God, but the results failed to reach conventional levels of statistical significance. |

| 14 | Robustness tests were run treating attend as a continuous variable and the results were essentially the same. |

| 15 | Using Steensland et al. (2000) RELTRAD scheme, a set of dummy variables was created for Evangelical Protestant, Mainline Protestant, Black Protestant, and Catholic. Other robustness tests using just RELIG to create Protestant and Catholic dummy variables was also conducted and yield similar results. |

| 16 | Robustness tests were also run controlling for perceived religious affiliation strength (RELITEN) and the results were essentially the same. |

| 17 | As part of our supplemental analyses, we considered the individual elements that make up our composite measure of misanthropy, and tested the expectation that greater levels of religiosity among Blacks and Latinos will be associated with lower levels of trust in others, and a lower likelihood of viewing others as fair and helpful; and greater levels of religiosity among Whites will be associated with higher levels of trust in others and a greater likelihood of viewing others as fair and helpful. |

| 18 | Available upon request. |

| 19 | Belonging to a predominantly Black or predominantly Latino church could provide emotional and spiritual support for adherents amid daily struggles while simultaneously increasing misanthropy (aimed at the outside world) as a by-product. Unfortunately, the current dataset doesn’t allow us to explore this question directly, but we hope our research will inspire further inquiries into this important matter in the future. |

| 20 | As historian, sociologist, and commentator, Du Bois wrote extensively on the promise and perils of the black church. See The Souls of Black Folk, The Negro Church, Dusk of Dawn, and The Philadelphia Negro to name just a few sources. He is generally acknowledged to have been both supporter of the black church as a site for the social, political and economic elevation of blacks, but also a critic of the black church for not fully embracing its full potential as a force for social change (See Blum 2007; Savage 2000). |

References

- Addai, Isaac, Chris Opoku-Agyeman, and Helen T. Ghartey. 2013. An exploratory study of religion and trust in Ghana. Social Indicators Research 110: 993–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alesina, Alberto F., and Eliana La Ferrara. 2000. The Determinants of Trust. Working Paper 7621. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Alesina, Alberto, and Eliana La Ferrara. 2002. Who trusts others? Journal of Public Economics 85: 207–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arneil, Barbara. 2010. Social decline and diversity: The Us versus the Us’s. Canadian Journal of Political Science 43: 273–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bègue, Laurent. 2002. Beliefs in justice and faith in people: Just world, religiosity and interpersonal trust. Personality and Individual Differences 32: 375–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berggren, Niclas, and Christian Bjørnskov. 2009. Does Religiosity Promote or Discourage Social Trust? Evidence from Cross-Country and Cross-State Comparisons. SSRN. October 10. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1478445 (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- Berggren, Niclas, and Christian Bjørnskov. 2011. Is the importance of religion in daily life related to social trust? Cross-country and cross-state comparisons. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 80: 459–80. [Google Scholar]

- Berggren, Niclas, and Henrik Jordahl. 2006. Free to trust: Economic freedom and social capital. Kyklos 59: 141–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørnskov, Christian. 2007. Determinants of generalized trust: A cross-country comparison. Public Choice 130: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blalock, Hubert M., Jr. 1967. Status inconsistency, social mobility, status integration and structural effects. American Sociological Review 32: 790–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, Edward J. 2007. WEB Du Bois, American Prophet. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Blumer, Herbert. 1958. Race prejudice as a sense of group position. Pacific Sociological Review 1: 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brañas-Garza, Pablo, Maximo Rossi, and Dayna Zaclicever. 2009. Individual’s religiosity enhances trust: Latin American evidence for the puzzle. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 41: 555–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brehm, John, and Wendy Rahn. 1997. Individual-level evidence for the causes and consequences of social capital. American Journal of Political Science 41: 999–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunson, Rod K., and Ronald Weitzer. 2011. Negotiating unwelcome police encounters: The intergenerational transmission of conduct norms. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 40: 425–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, Donn Erwin. 1971. The Attraction Paradigm. New York: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Charles, Camille Z. 2003. The dynamics of racial residential segregation. Annual Review of Sociology 29: 167–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conde-Frazier, Elizabeth, and Andrew Y. Lee. 2015. Intergenerational and Intercultural Issues. Common Ground Journal 12: 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- Coverdill, James E., Carlos A. López, and Michelle A. Petrie. 2011. Race, ethnicity and the quality of life in America, 1972–2008. Social Forces 89: 783–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, Joseph P., and Marc Von Der Ruhr. 2010. Trust in others: Does religion matter? Review of Social Economy 68: 163–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, James A., Tom William Smith, and Peter V. Marsden. 2007. General Social Surveys, 1972–2006 [Cumulative File]. Ann Arbor: Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research, University of Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- Delhey, Jan, and Kenneth Newton. 2005. Predicting Cross-National Levels of Social Trust: Global Pattern or Nordic Exceptionalism? European Sociological Review 21: 311–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delhey, Jan, Kenneth Newton, and Christian Welzel. 2011. How General is Trust in “Most People”? Solving the Radius of Trust Problem. American Sociological Review 76: 786–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickerson, Dennis C. 2005. African American religious intellectuals and the theological foundations of the civil rights movement, 1930–1955. Church History 74: 217–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilmaghani, Maryam. 2017. Religiosity and social trust: Evidence from Canada. Review of Social Economy 75: 49–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinesen, Peter T., Merlin Schaeffer, and Kim Mannemar Sønderskov. 2020. Ethnic diversity and social trust: A narrative and meta-analytical review. Annual Review of Political Science 23: 441–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djupe, Paul A., and Christopher P. Gilbert. 2009. The Political Influence of Churches. Edited by D. C. Leege and K. D. Wald. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Djupe, Paul A., and Jacob R. Neiheisel. 2012. How religious communities affect political participation among Latinos. Social Science Quarterly 93: 333–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douds, Kiara, and Jie Wu. 2018. Trust in the bayou city: Do racial segregation and discrimination matter for generalized trust? Sociology of Race and Ethnicity 4: 567–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelist, Michael. 2022. Narrowing racial differences in trust: How discrimination shapes trust in a racialized society. Social Problems 69: 1109–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greeley, Andrew M. 1994. The demography of American Catholics: 1965–1990. In The Sociology of Andrew Greeley. Atlanta: Scholars Press, pp. 545–64. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, Paul. 2016. Christianity and Race in the American South: A History. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heimer, Carol A. 2001. Solving the Problem of Trust. In Trust in Society. Edited by Karen S. Cook. New York: Russel Sage Foundation, pp. 40–118. [Google Scholar]

- Helliwell, John F., and Robert D. Putnam. 2004. The social context of well-being. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences 359: 1435–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hempel, Lynn M., John Bartkowski, and Todd Matthews. 2012. Trust in a “Fallen World”: The Case of Protestant Theological Conservatism. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 51: 522–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, Robert. 2013. The experimental economics of religion. Journal of Economic Surveys 27: 813–45. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, Diane. 2003. Correlates of African American and Latino parents’ messages to children about ethnicity and race: A comparative study of racial socialization. American Journal of Community Psychology 31: 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, Michael, and Melvin E. Thomas. 1998. The continuing significance of race revisited: A study of race, class, and quality of life in America, 1972 to 1996. American Sociological Review 63: 785–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, Larry L. 1999. Hispanic Protestantism in the United States: Trends by decade and generation. Social Forces 77: 1601–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inwood, Joshua. 2019. White supremacy, white counter-revolutionary politics, and the rise of Donald Trump. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space 37: 579–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones-Correa, Michael A., and David L. Leal. 2001. “Political Participation: Does Religion Matter?”. Political Research Quarterly 54: 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiecolt, K. Jill, Eboni Morris, and Jeffrey Toussaint. 2006. Race and social trust. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Sociological Association, Montreal, ON, Canada, August 11. [Google Scholar]

- Kilson, Martin. 2009. Thinking about Robert Putnam’s analysis of diversity. Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race 6: 293–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirschenman, Joleen, and Katherine Neckerman. 1991. “We’d Love to Hire Them But…”. In The Urban Underclass. Edited by Christopher Jencks and Paul Peterson. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution. [Google Scholar]

- La Porta, Rafael, Florencio Lopez-de-Silanes, Andrei Shleifer, and Robert W. Vishny. 1996. Trust in Large Organizations. NBER Working Paper Series 5864; Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Jongho, Harry P. Pachon, and Matt Barreto. 2002. Guiding the Flock: Church as Vehicle of Latino Political Participation. Paper presented at the American Political Science Association Annual Meeting, Boston, MA, USA, August 29–September 1. [Google Scholar]

- Leighley, Jan E. 1996. Group Membership and the Mobilization of Political Participation. Journal of Politics 58: 447–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdam, Doug. 1999. Political Process and the Development of Black Insurgency, 1930–1970. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie, Brian D. 2004. Religious Social Networks, Indirect Mobilization, and African-American Political Participation. Political Research Quarterly 57: 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherson, Miller, Lynn Smith-Lovin, and James M. Cook. 2001. Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks. Annual Review of Sociology 27: 415–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melgar, Natalia, Maximo Rossi, and Tom W. Smith. 2013. Individual attitudes toward others: Misanthropy analysis in a cross-country perspective. American Journal of Economics and Sociology 72: 222–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, Aldon. 1984. The Origins of the Civil Rights Movement: Black Communities Organizing for Change. New York: The Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, Aldon. 2014. The Black Church in the civil rights movement: The SCLC as the decentralized, radical arm of the Black church. In Disruptive Religion: The Force of Faith in Social Movement Activism. New York: Routledge, pp. 29–46. [Google Scholar]

- Moss, Philip, and Chris Tilly. 2001. Stories Employers Tell: Race, Skill, and Hiring in America. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Mulder, Mark T., Aida Ramos, and Gerardo Marti. 2017. Chapter 6: Latino Protestants and Their Political and Social Engagement. In Latino Protestants in America: Growing and Diverse. Newberg: Faculty Publications—Department of World Language, Sociology and Cultural Studies, George Fox University, pp. 101–32. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, Shayla C. 2012. Trust in Black America: Race, Discrimination, and Politics. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Orbell, John, Marion Goldman, Matthew Mulford, and Robyn Dawes. 1992. Religion, context, and constraint toward strangers. Rationality and Society 43: 291–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pager, Devah, and Hana Shepherd. 2008. The sociology of discrimination: Racial discrimination in employment, housing, credit, and consumer markets. Annual Review of Sociology 34: 181–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pager, Devah, Bart Bonikowski, and Bruce Western. 2009. Discrimination in a low-wage labor market: A field experiment. American Sociological Review 74: 777–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, Orlando. 1999. Liberty against the democratic state: On the historical and contemporary sources of American trust. In Democracy and Trust. Edited by Warren Mark. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 151–207. [Google Scholar]

- Paxton, Pamela. 1999. Is social capital declining in the United States? A multiple indicator assessment. American Journal of Sociology 105: 88–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, Robert D. 2000. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, Robert D. 2007. E pluribus unum: Diversity and community in the twenty-first century the 2006 Johan Skytte Prize Lecture. Scandinavian Political Studies 30: 137–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenstone, Steven J., and John M. Hansen. 1993. Mobilization, Participation, and Democracy in America. New York: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, Catherine E., John Mirowsky, and Shana Pribesh. 2001. Powerlessness and the amplification of threat: Neighborhood disadvantage, disorder, and mistrust. American Sociological Review 66: 568–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, Barbara Dianne. 2000. W.E.B. Du Bois and “The Negro Church”. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 568: 235–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenfeld, Eugen. 1978. Image of man: The effect of religion on trust. Review of Religious Research 20: 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwadel, Philip. 2005. Individual, Congregational, and Denominational Effects on Church Members’ Civic Participation. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 44: 159–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwadel, Philip. 2010. Age, period, and cohort effects on US religious service attendance: The declining impact of sex, southern residence, and Catholic affiliation. Sociology of Religion 71: 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwadel, Philip. 2011. Age, period, and cohort effects on religious activities and beliefs. Social Science Research 40: 181–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, Brent, Tucker McGrimmon, and Kyle Irwin. 2007. Are Blacks really less trusting than Whites? Revisiting the race and trust question. Social Forces 86: 525–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smidt, Corwin. 1999. Religion and civic engagement: A comparative analysis. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 565: 176–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Sandra Susan. 2010. Race and trust. Annual Review of Sociology 36: 453–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Tom W. 1997. Factors relating to misanthropy in contemporary American society. Social Science Research 26: 170–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosis, Richard. 2005. Does religion promote trust? The role of signaling, reputation, and punishment. Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion 1: 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Steensland, Brian, Jerry Z. Park, Mark D. Regnerus, Lynn D. Robinson, W. Bradford Wilcox, and Robert D. Woodberry. 2000. The Measure of American Religion: Toward Improving the State of the Art. Social Forces 79: 291–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stets, Jan E., and Phoenicia Fares. 2019. The effects of race/ethnicity and racial/ethnic identification on general trust. Social Science Research 80: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, Henri, and John C. Turner. 1982. Social psychology of intergroup relations. Annual Review of Psychology 33: 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, Henri, Michael G. Billig, Robert P. Bundy, and Claude Flament. 1971. Social categorization and intergroup behaviour. European Journal of Social Psychology 1: 149–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Paul, Cary Funk, and April Clark. 2007. Americans and Social Trust: Who, Where and Why. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Traunmüller, Richard. 2009. Individual religiosity, religious context, and the creation of social trust in Germany. Journal of Contextual Economics 129: 357–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uslaner, Eric M. 2002. The Moral Foundations of Trust. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Uslaner, Eric M., and Mitchell Brown. 2005. Inequality, trust, and civic engagement. American Politics Research 33: 868–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, Rubia R., and Adam Okulicz-Kozaryn. 2021. Religiosity and trust: Evidence from the United States. Review of Religious Research 63: 343–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela, Ali A. 2014. Tending the Flock: Latino Religious Commitments and Political Preferences. Political Research Quarterly 67: 930–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veenstra, Gerry. 2002. Explicating social capital: Trust and participation in the civil space. Canadian Journal of Sociology/Cahiers Canadiens de Sociologie 27: 547–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarreal, Daniel. 2020. Hate Crimes under Trump Surged nearly 20 Percent Says FBI Report. Newsweek. November 16. Available online: https://www.newsweek.com/hate-crimes-under-trump-surged-nearly-20-percent-says-fbi-report-1547870 (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- Warnock, Raphael G. 2020. The Divided Mind of the Black Church: Theology, Piety and Public Witness. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Warren, Mark. 2001. Dry Bones Rattling: Community Building to Revitalize American Democracy. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Welch, Michael, David Sikkink, and Matthew Loveland. 2007. The radius of trust: Religion, social embeddedness and trust in strangers. Social Forces 86: 23–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, Michael, David Sikkink, Eric Sartain, and Carolyn Bond. 2004. Trust in God and trust in man: The ambivalent role of religion in shaping dimensions of social trust. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 43: 317–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Western, Bruce. 2006. Punishment and Inequality in America. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkes, Rima. 2011. Re-thinking the decline in trust: A comparison of Black and White Americans. Social Science Research 40: 1596–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkes, Rima, and Cary Wu. 2019. Immigration, discrimination, and trust: A simply complex relationship. Frontiers in Sociology 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zak, Paul J., and Stephen Knack. 2001. Trust and growth. Economic Journal 111: 295–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Obs | Total Mean | Black | White | Latino | Min. | Max. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variables | |||||||

| Misanthropy index | 14,142 | 2.065 (0.749) | 2.385 (0.646) | 1.950 (0.752) | 2.345 (0.657) | 1 | 3.041 |

| Trust | 14,765 | 1.712 (0.929) | 1.363 (0.741) | 1.839 (0.958) | 1.395 (0.766) | 1 | 3 |

| Helpful | 14,266 | 1.623 (0.639) | 1.746 (0.623) | 1.572 (0.642) | 1.768 (0.600) | 1 | 3 |

| Fair | 14,221 | 2.109 (0.951) | 1.737 (0.919) | 2.23 (0.932) | 1.876 (0.942) | 1 | 3 |

| Focal predictors | |||||||

| Frequency of service attendance | 25,442 | 3.517 (2.78) | 4.37 (2.67) | 3.324 (2.79) | 3.61 (2.68) | 0 | 8 |

| Frequency of prayer | 19,845 | 3.236 (1.729) | 4.0 (1.313) | 3.061 (1.782) | 3.313 (1.609) | 0 | 5 |

| Control variables | |||||||

| Real income in $1986, millions | 22,743 | 0.034 (0.034) | 0.022 (0.023) | 0.038 (0.036) | 0.025 (0.027) | 0.0002 | 0.1551 |

| Marital status | 25,615 | 0.461 (0.498) | 0.273 (0.446) | 0.502 (0.500) | 0.446 (0.497) | 0 | 1 |

| Age | 25,546 | 47.77 (17.44) | 44.49 (16.23) | 49.73 (17.65) | 40.19 (14.79) | 18 | 89 |

| Age2 | 25,546 | 2586.47 (1794.8) | 2242.96 (1596.56) | 2785.04 (1850.37) | 1833.66 (1381.42) | 324 | 7921 |

| Education | 25,577 | 13.464 (3.025) | 12.95 (2.75) | 13.85 (2.827) | 11.80 (3.74) | 0 | 20 |

| Gender (male) | 25,633 | 0.445 (0.497) | 0.385 (0.487) | 0.457 (0.498) | 0.450 (0.498) | 0 | 1 |

| U.S. nativity | 24,136 | 0.899 (0.302) | 0.919 (0.273) | 0.955 (0.207) | 0.535 (0.499) | 0 | 1 |

| Urbanicity | 25,633 | 0.890 (0.312) | 0.922 (0.268) | 0.870 (0.336) | 0.969 (0.173) | 0 | 1 |

| Conservative | 21,948 | 0.342 (0.474) | 0.242 (0.429) | 0.371 (0.483) | 0.289 (0.453) | 0 | 1 |

| Liberal | 21,948 | 0.273 (0.445) | 0.316 (0.465) | 0.261 (0.439) | 0.292 (0.455) | 0 | 1 |

| Unemployed | 25,617 | 0.040 (0.195) | 0.064 (0.244) | 0.032 (0.177) | 0.053 (0.224) | 0 | 1 |

| Occupation prestige | 24,470 | 43.63 (13.16) | 40.46 (12.39) | 44.94 (13.20) | 39.45 (12.22) | 16 | 80 |

| Region (South) | 25,633 | 0.381 (0.486) | 0.589 (0.492) | 0.341 (0.474) | 0.360 (0.480) | 0 | 1 |

| Year of survey | 25,633 | 2008.502 (5.76) | 2008.78 (5.87) | 2008.23 (5.73) | 2009.74 (5.57) | 2000 | 2018 |

| Religious Tradition | |||||||

| Mainline Protestant | 25,633 | 0.146 (0.353) | 0.078 (0.268) | 0.182 (0.385) | 0.021 (0.143) | 0 | 1 |

| Black Protestant | 25,633 | 0.197 (0.398) | 0.506 (0.500) | 0.159 (0.366) | 0.041 (0.199) | 0 | 1 |

| Evangelical Protestant | 25,633 | 0.251 (0.433) | 0.469 (0.499) | 0.229 (0.420) | 0.109 (0.311) | 0 | 1 |

| Catholic | 25,493 | 0.237 (0.425) | 0.061 (0.240) | 0.216 (0.411) | 0.584 (0.493) | 0 | 1 |

| Theological Conservatism | |||||||

| Fundamentalist | 24,641 | 2.031 (0.774) | 1.639 (0.7972) | 2.11 (0.779) | 2.04 (0.553) | 1 | 3 |

| Bible | 20,553 | 2.125 (0.722) | 2.440 (0.683) | 2.044 (0.710) | 2.21 (0.725) | 1 | 3 |

| VARIABLES | b1 | b2 | b3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ref: White | |||

| Black | 0.219 *** | 0.214 *** | 0.094 *** |

| Latino | 0.178 *** | 0.180 *** | 0.067 *** |

| Attend | −0.095 *** | −0.116 *** | −0.082 *** |

| Pray | 0.051 *** | 0.011 | |

| Real income | −0.082 *** | ||

| Catholic | −0.008 | ||

| Mainline Protestant | −0.044 *** | ||

| Black Protestant | 0.054 *** | ||

| Evangelical Protestant | −0.025 | ||

| Fundamentalist | −0.033 | ||

| Bible | 0.052 *** | ||

| Conservative | −0.005 | ||

| Liberal | −0.044 *** | ||

| Married | −0.043 *** | ||

| Unemployed | 0.010 | ||

| Occ Prestige | −0.057 *** | ||

| Age | −0.185 *** | ||

| Age2 | −0.007 | ||

| Education | −0.169 *** | ||

| Male | 0.013 | ||

| Born US | −0.006 | ||

| Urban | −0.010 | ||

| South | 0.064 *** | ||

| Constant | *** | *** | *** |

| R-Squared | 0.0712 | 0.0733 | 0.1948 |

| N | 14,004 | 13,049 | 10,443 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | Trust | Fair | Helpful |

| Attend (ref: never) | |||

| Less than once a year | 0.023 * | 0.012 | −0.008 |

| About once or twice a year | 0.018 | 0.029 * | 0.014 |

| Several times a year | 0.021 | 0.030 * | 0.027 * |

| About once a month | 0.024 | 0.046 *** | 0.009 |

| 2–3 times a month | 0.038 ** | 0.048 *** | 0.037 ** |

| Nearly every week | 0.020 | 0.047 *** | 0.029 * |

| Every week | 0.101 *** | 0.105 *** | 0.061 *** |

| Several times a week | 0.035 ** | 0.027 | 0.023 |

| Race (ref: White) | |||

| Black | −0.067 ** | −0.058 * | −0.023 |

| Latino | −0.011 | −0.036 | −0.047 * |

| Less than once a year*Black | 0.001 | −0.001 | 0.013 |

| Less than once a year*Latino | −0.029 ** | 0.001 | 0.023 * |

| About once or twice a year*Black | −0.012 | −0.012 | −0.008 |

| About once or twice a year*Latino | −0.020 | −0.001 | 0.005 |

| Several times a year*Black | 0.002 | −0.020 | −0.002 |

| Several times a year*Latino | −0.022 * | −0.007 | −0.017 |

| About once a month*Black | −0.002 | −0.018 | 0.007 |

| About once a month*Latino | −0.025 * | −0.016 | 0.004 |

| 2–3 times a month*Black | −0.018 | −0.006 | −0.015 |

| 2–3 times a month*Latino | −0.024 * | 0.002 | 0.005 |

| Nearly every week*Black | −0.003 | −0.010 | −0.012 |

| Nearly every week*Latino | −0.005 | 0.006 | 0.012 |

| Every week*Black | −0.037 ** | −0.031 | −0.028 |

| Every week*Latino | −0.042 *** | −0.022 | −0.014 |

| Several times a week*Black | −0.004 | 0.004 | 0.006 |

| Several times a week*Latino | −0.018 | 0.016 | 0.006 |

| Observations | 10,876 | 10,478 | 10,489 |

| R-squared | 0.164 | 0.134 | 0.085 |

| Constant | *** | *** | *** |

| Year dummies and controls | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| VARIABLES | White | Black | Latino |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attend (ref: never) | |||

| Less than once a year | −0.015 | −0.011 | −0.013 |

| About once or twice a year | 0.005 | −0.024 * | −0.021 |

| Several times a year | 0.006 | −0.025 * | −0.027 * |

| About once a month | −0.007 | −0.026 * | −0.029 ** |

| 2–3 times a month | −0.025 | −0.049 *** | −0.038 *** |

| Nearly every week | −0.032 | −0.043 *** | −0.033 ** |

| Every week | −0.016 | −0.100 *** | −0.093 *** |

| Several times a week | −0.039 * | −0.035 ** | −0.035 ** |

| White = 1 | −0.067 ** | ||

| Less than once a year*White | 0.003 | ||

| About once or twice a year*White | −0.028 | ||

| Several times a year*White | −0.033 | ||

| About once a month*White | −0.023 | ||

| 2–3 times a month*White | −0.023 | ||

| Nearly every week*White | −0.008 | ||

| Every week*White | −0.086 *** | ||

| Several times a week*White | 0.002 | ||

| Black = 1 | 0.057 ** | ||

| Less than once a year*Black | −0.005 | ||

| About once or twice a year*Black | 0.014 | ||

| Several times a year*Black | 0.007 | ||

| About once a month*Black | 0.002 | ||

| 2–3 times a month*Black | 0.014 | ||

| Nearly every week*Black | 0.011 | ||

| Every week*Black | 0.035 * | ||

| Several times a week*Black | −0.003 | ||

| Latino = 1 | 0.032 | ||

| Less than once a year*Latino | 0.002 | ||

| About once or twice a year*Latino | 0.005 | ||

| Several times a year*Latino | 0.016 | ||

| About once a month*Latino | 0.013 | ||

| 2–3 times a month*Latino | 0.000 | ||

| Nearly every week*Latino | −0.010 | ||

| Every week*Latino | 0.026 * | ||

| Several times a week*Latino | −0.005 | ||

| Observations | 10,455 | 10,455 | 10,443 |

| R-squared | 0.197 | 0.193 | 0.190 |

| Constant | *** | *** | *** |

| Year dummies and controls | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Variables | OLS Coefficients (Misanthropy) | Beta (Misanthropy) |

|---|---|---|

| Attend (ref: never) | ||

| Less than once a year | −0.033 | −0.011 |

| About once or twice a year | −0.057 * | −0.026 * |

| Several times a year | −0.076 * | −0.032 * |

| About once a month | −0.106 ** | −0.035 ** |

| 2–3 times a month | −0.143 *** | −0.054 *** |

| Nearly every week | −0.146 *** | −0.041 *** |

| Every week | −0.227 *** | −0.115 *** |

| Several times a week | −0.107 ** | −0.036 ** |

| Race (ref: white) | ||

| Black | 0.139 ** | 0.064 ** |

| Latino | 0.097 * | 0.042 * |

| Less than once a year*Black | −0.046 | −0.005 |

| Less than once a year*Latino | 0.009 | 0.001 |

| About once or twice a year*Black | 0.085 | 0.014 |

| About once or twice a year*Latino | 0.039 | 0.007 |

| Several times a year*Black | 0.058 | 0.009 |

| Several times a year*Latino | 0.108 | 0.017 |

| About once a month*Black | 0.040 | 0.005 |

| About once a month*Latino | 0.110 | 0.015 |

| 2–3 times a month*Black | 0.082 | 0.016 |

| 2–3 times a month*Latino | 0.042 | 0.007 |

| Nearly every week*Black | 0.078 | 0.010 |

| Nearly every week*Latino | −0.066 | −0.007 |

| Every week*Black | 0.179 ** | 0.040 ** |

| Every week*Latino | 0.186 ** | 0.034 ** |

| Several times a week*Black | −0.019 | −0.003 |

| Several times a week*Latino | −0.023 | −0.003 |

| Observations | 10,443 | 10,443 |

| R-squared | 0.197 | 0.197 |

| Constant | 3.201 *** | *** |

| Year dummies and controls | Yes | Yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Valente, R.R.; Smith, R.A. Religiosity and Misanthropy across the Racial and Ethnic Divide. Religions 2023, 14, 393. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14030393

Valente RR, Smith RA. Religiosity and Misanthropy across the Racial and Ethnic Divide. Religions. 2023; 14(3):393. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14030393

Chicago/Turabian StyleValente, Rubia R., and Ryan A. Smith. 2023. "Religiosity and Misanthropy across the Racial and Ethnic Divide" Religions 14, no. 3: 393. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14030393

APA StyleValente, R. R., & Smith, R. A. (2023). Religiosity and Misanthropy across the Racial and Ethnic Divide. Religions, 14(3), 393. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14030393