„I Die, but I Thank You…!“ Leipzig Mission at Akeri 1896, Squeezed between Its African Addressees and German Colonial Military

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Historiography of Entanglements of German Colonialism, Christian Mission, and African Indigenous Leadership

2.1. Mapping the Field of the Case Study

2.2. Navigation through a Discursive Entangled Historiography

2.3. “Entangled Historiography” as an Instrument to Deconstruct the Hegemonial Discourse on the “Akeri 1896”

2.4. Research Objectives (“To-Dos”), Put in Order according to the Papers Structure

2.5. The “Colonial Situation” as the Context of Mission Activities

3. Factors and Actors in Certain Times at Certain Places Related to the Events at “Akeri 1896”

3.1. The Eight Historical Factors Being Intersected or Entangled with One Another at “Akeri 1896”

3.1.1. Traditional African Societies’ Leadership (Chagga, Meru, Arusha, Maasai) in Relations

3.1.2. Coastal Colonial Regime of the Sultanate of Zanzibar

3.1.3. German Imperial Protection Force (“Kaiserliche Schutztruppe”)

3.1.4. German Colonizers, Traders, and Settlers in East Africa

3.1.5. German Imperial Government at the Center in Berlin

“The government will least of all renounce the support of the Christian missionary societies, without whose sacrificial and beneficial activity the entire colonial work would be called into question. The Government, for its part, will encourage the mission in every way and give it full freedom in the exercise of its profession in all protectorates”.

3.1.6. German Imperial Government Represented at the “Margins” in East Africa

3.1.7. Entangled Missions: Leipzig Mission, Church Missionary Society (CMS), and Holy Ghost Fathers

“(…) to expand the Lutheran work westwards. The work among the Chagga of Kilimanjaro was well underway and the enlargement of the Lutheran work was timely. Moreover, with increased competition from the Catholic Holy Ghost Fathers, swift expansion was considered necessary. In October 1896, after receiving orders from the board in Leipzig, Ovir and Segebrock travelled to Mount Meru to make preparations for the foundation of a station amid the Meru (Waro) tribe inhabiting the southeastern slopes of the mountain. In an optimistic letter to Missionary Emil Müller, Ovir reported about a friendly reception by Mangi Matunda, the Meru Chief. Ovir also noted that the Holy Ghost Fathers had not preceded them”.

3.1.8. German Mission Societies Headquarters at Leipzig

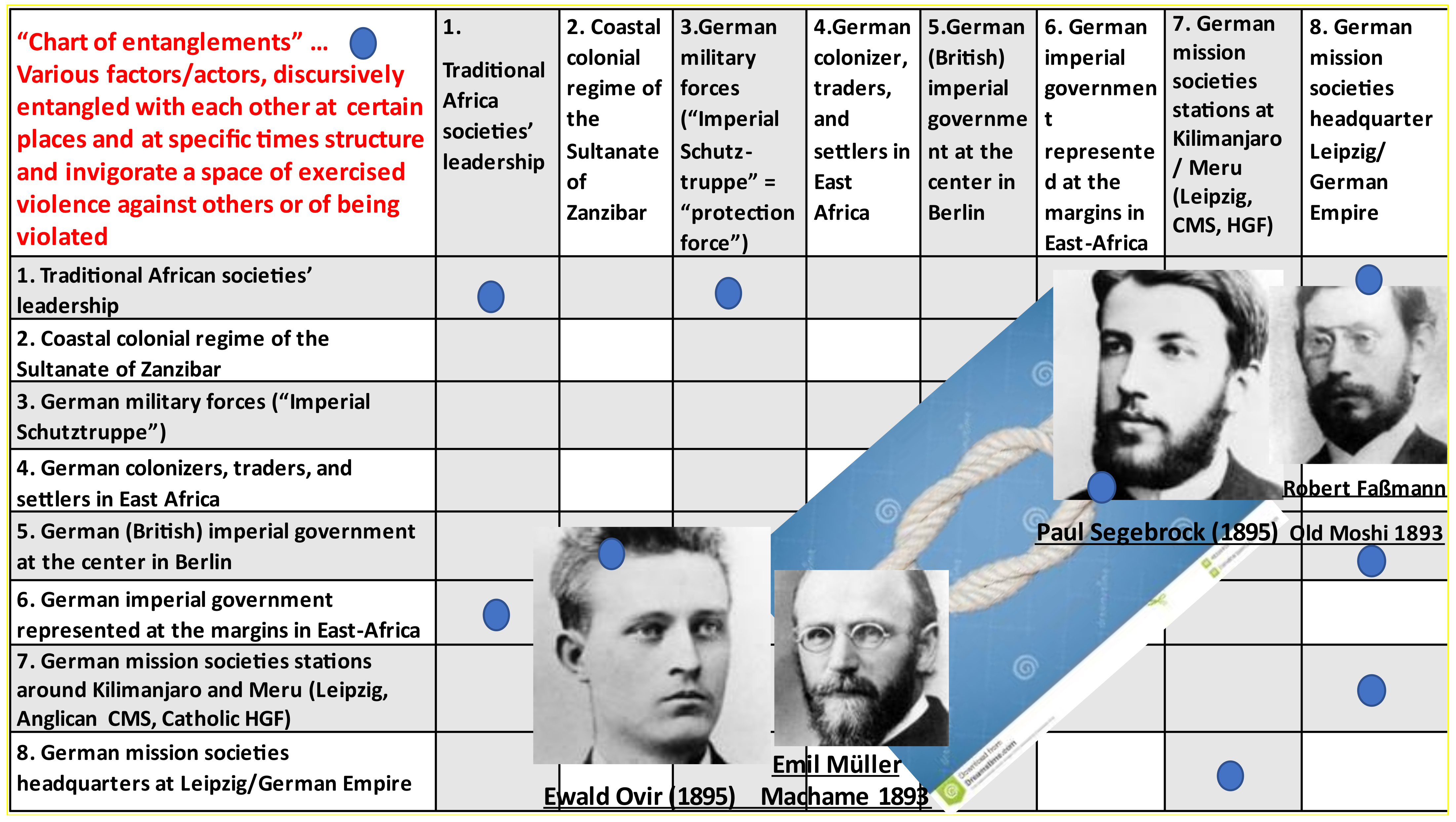

3.2. “Chart of Entanglements” between Various Factors and Actors at Certain Places

|

| Above: chart of entanglements (M. Fischer) |

3.3. Factors and Actors at Certain Places and Times, Structuring and Invigorating a Discursive Space

- Traditional African societies’ leadership, intersected by Point 1; regional internal conflicts between Chagga and Arusha misused for revenge of the protection force (1896ff)

- Coastal colonial regime of the Sultanate of Zanzibar; intersected Point 5; Sultan Hamoud fully dependent on British empire after the Helgoland–Zanzibar treaty (1890)

- German military forces (“Imperial Schutztruppe”); intersected by 1; missing experience of living in foreign environments, lack of knowledge, permanent fear of attacks (1896)

- German colonizers, traders, and settlers in East Africa; intersected by 6; confiscation of traditional land, access reserved to colonists, declared by German government (1895)

- German imperial government at the centre in Berlin; intersected by Point 8; government giving the mission freedom to exercise its profession in protectorates reveals the dependency of mission on the state and the supposed imperial character of such a hegemonic “mission” (1884)

- Imperial government represented in East Africa; intersected by Point 1; forced labour of Arusha warriors, constructing the Boma of Arusha as a collective punishment (1900)

- German mission societies stations around Kilimanjaro and Meru (Leipzig, Anglican CMS, Catholic HGF); Intersected by Point 8; dependency; decisions such as the foundation of a new station must be permitted by the LM headquarter (1896)

- German mission societies headquarters at Leipzig/German Empire; Intersecting Point 1 and Point 7; wrong, tendentious information about the traditional religions, demonizing it, and reported by Leipzig missionaries as “objective truth” to Leipzig society’s headquarters and the seminary may result in misunderstandings of the supposed superior missiologists.

4. Correlated Wounds and Vulnerabilities, Remembered in a “Christian Calendar of Names”

4.1. A “Wounded Mission”: Who Were the Real “Victims” at Mount Meru?

4.2. The Victims of the “Akeri Killings” in the Military Contexts

4.3. The “Evangelical Calendar of Names”, Questioning a Culture of Remembrance

5. Concluding Observations

- This term theologically should not in a Christian-Protestant view be used. In opposition to a Roman-Catholic dogmatic understanding there does not exist a supposed martyrial bloodshed as a mean of grace that could substitute men’s sin;

- Historically, the missionaries did not die because of their faith but because they were seen as colonial invaders in alliance with the Schutztruppe in an extremely naive and miserably organized action from both actors, missionary and colonial;

- Their blood was shed because their lives had been “caught in the crossfire” between the fronts of two armies (Arusha-Maasai in defense and Schutztruppe in aggression), which collided.

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

Sources/Quellen from the Magazines and Archive of ELCT-Northern Diocese (Moshi/Tanzania)

HISTORIA YA KANISA LA KIINJILI LA KILUTHERI TANZANIA KASKAZINI toka 1893–940 (KP Kiesel)KITABU CHA MATHAYO KAAYA (KP Kiesel)UHURU NA AMANI 60 May 1971/5, “Mashahidi wa Yesu Huko Meru”, pp. 9–11 (KP Kiesel)UMOJA XXI Novemba 1969/252, “Historia Fupi Ya dayosisi Yetu Ya Kaskazini,” pp. 3–4- Altena, Thorsten. 2003. „Ein Häuflein Christen mitten in der Heidenwelt des dunklen Erdteils“. Zum Selbst- und Fremdverständnis protestantischer Missionare im kolonialen Afrika 1884–1918. Münster: Waxmann, pp. 282–84. [Google Scholar]

- Althaus, Gerhard. 1992. Mamba. Anfang in Afrika (bearbeitet und hrsg. Von Hans-Ludwig Althaus). Erlangen: Missionsverlag. [Google Scholar]

- Arendt, Hannah. 1951. The Origins of Totalitarism. New York: Hartcourt Brace Jovanovich. [Google Scholar]

- Arndt, Agnes, Joachim Häberlein, and Christiane Reinecke, eds. 2011. Vergleichen, verflechten, verwirren? Europäische Geschichtsschreibung zwischen Theorie und Praxis. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [Google Scholar]

- Balandier, Georges. 1970. Die koloniale Situation: Ein theoretischer Ansatz. In Moderne Kolonialgeschichte. Edited by Rudolf Albertini. Köln and Berlin: Kiepenheuer & Witsch, pp. 105–24. [Google Scholar]

- Budde, Gunilla, Sebastian Conrad, and Oliver Janz, eds. 2010. Transnationale Geschichte: Themen, Tendenzen und Theorien, 2nd ed. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [Google Scholar]

- Conrad, Sebastian, and Shalini Randeria. 2002. Geteilte Geschichten—Europa in einer postkolonialen Welt. In Jenseits des Eurozentrismus: Postkoloniale Perspektiven in den Geschichts- und Kulturwissenschaften. Edited by Sebastian Conrad and Shalini Randeria. Frankfurt: Campus Verlag, pp. 9–49. [Google Scholar]

- Conrad, Sebastian, and Shalini Randeria. 2013. Einleitung: Geteilte Geschichten—Europa in einer postkolonialen Welt. In Jenseits des Eurozentrismus. Postkoloniale Perspektiven in den Geschichts- und Kulturwissenschaften, 2nd ed. Edited by Sebastian Conrad, Shalini Randeria and Regina Römhild. Frankfurt and New York: Campus, pp. 32–70. [Google Scholar]

- Cronin, Stephanie, ed. 2012. Subalterns and Social Protest. History from Below in the Middle East and North Africa. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Evangelisch-Lutherisches Missionsblatt. 1897. Für die Evangelisch-Lutherische Mission zu Leipzig. Leipzig: Evangelisch-Lutherisches Missionsblatt. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, Moritz, and Michael Thiel, eds. 2022. Investigations on the “Entangled History” of Colonialism and Mission in a New Perspective. Berlin: LIT-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Fosbrooke, Henry A. 1948. An Administrative Survey of the Masai Social System. Available online: https://ehrafworldcultures.yale.edu/cultures/fl12/documents/009 (accessed on 8 March 2023).

- Groop, Kim. 2006. With the Gospel to Maasailand. Lutheran Mission Work among the Arusha and Maasai in Northern Tanzania 1904–1973. Abo: Abo University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, Rebekka. 2008. Mission im 19. Jahrhundert. Globale Netze des Religiösen Mission in the 19th century. Global Networks of Religion. Historische Zeitschrift 3/287 629–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habermas, Rebekka, and Richard Hölzl, eds. 2014. Mission Global: Eine Verflechtungsgeschichte seit dem 19. Jahrhundert. Köln, Weimar and Wien: Böhlau. [Google Scholar]

- Hellberg, Carl-J. 1997. Mission, Colonialism, and Liberation: The Lutheran Church in Namibia, 1840–1966. Windhoek: New Namibia Books. [Google Scholar]

- Hof, Eleonora Dorothea. 2016. Reimagining Mission in the Postcolonial Condition. A Theology of Vulnerability and Vocation at the Margins. Zoetermeer: Boekencentrum Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, Anna. 2003. Missionary Writing and Empire, 1800–1860. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kamphausen, Erhard. 2015. Spurensuche: Religiöse afrikanische Protestbewegungen in Namibia. In Umstrittene Beziehungen. Protestantismus zwischen dem südlichen Afrika und Deutschland von den 1930er Jahren bis in die Apartheidszeit. Edited by Hans Lessing, Tilman Dedering, Jürgen Kampmann and Dirkie Smit. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, pp. 243–59. [Google Scholar]

- Lema, Anza A. 1999. Chaga Religion and Missionary Christianity on Kilimanjaro: The Initial Phase, 1893–1916. In East African Expressions of Christianity. Edited by Thomas Spear and Isariah N. Kimambo. Oxford: James Currey, pp. 39–62. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Paul Allen. 1999. Toward a Post-Foucauldian History of Discursive Practices. Configurations 7: 227–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, Emil. 1936. Aus der Tiefe in die Höh‘. 20. Oktober 1896–1936. Segebrock und Ovir, unsere Blutzeugen am Meru. Leipzig: Verlag der Evangelisch-Lutherischen Mission. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, Emil, and Robert Faßmann. 1897. Die Bluttaufe unserer Mission am Meru. Nach Briefen von Müller und Faßmann. In Evangelisch-Lutherisches Missionsblatt (=ELMB). pp. 12–19. Available online: https://archivfuehrer-kolonialzeit.de/index.php/die-bluttaufe-unserer-mission-am-meru (accessed on 8 March 2023).

- Parsalaw, Joseph W. 1999. A History of the Church, Diocese in the Arusha Region from 1904 to 1958. Erlangen: Erlanger Verlag für Mission und Ökumene. [Google Scholar]

- Parsalaw, Joseph W. 2000. The Founding of Arusha Town. In Mission und Gewalt. Der Umgang christlicher Missionen mit Gewalt und die Ausbreitung des Chrisstentums in Afrika und Asien in der Zeit von 1792–1918/19. Edited by Ulrich van der Heyden. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, pp. 489–93. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, Carl. 1898. Die Mission in unsern Kolonien. Leipzig: Fr. Richter. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen, Joel D. S., Judith Wolfe, and Johannes Zachhuber, eds. 2017. The Oxford Handbook of Nineteenth-Century Christian Thought. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ratschiller, Linda, and Karolin Wetjen. 2018. Verflochtene Mission. Ansätze, Methoden und Fragestellungen einer neuen Missionsgeschichte. In Verflochtene Missionen. Perspektiven auf eine neue Missionsgeschichte. Edited by Linda Ratschiller and Karolin Wetjen. Köln: Böhlau, pp. 9–25. [Google Scholar]

- Riccardi, Andrea. 2002. Salz der Erde, Licht der Welt. Glaubenszeugnis und Christenverfolgung im 20. Jahrhundert. Freiburg, Basel and Wien: Herder. [Google Scholar]

- Sarasin, Philipp. 2011. Diskurstheorie und Geschichtswissenschaft. In Handbuch Sozialwissenschaftliche Diskursanalyse. Band 1: Theorien und Methoden. Edited by Reiner Keller, Andreas Hirseland, Werner Schneider and Willy Viehöver. Wiesbaden: Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, pp. 61–89. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz, Frieder. 1975. Das Gedächtnis der Zeugen—Vorgeschichte, Gestaltung und Bedeutung des Evangelischen Namenkalenders. Jahrbuch für Liturgik und Hymnologie 19: 69–104. [Google Scholar]

- Schulze, Thies. 2013. Einleitung. In Grenzüberschreitende Religion. Vergleichs- und Kulturtransferstudien zur neuzeitlichen Geschichte. Edited by Thies Schulze and Christian Müller. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, pp. 9–25. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, Carl von. 1912. Mission und Kolonisation in ihrem gegenseitigen Verhältnis. Missionsstudie, 2nd ed. Leipzig: Verlag der Evang.-Luth. Mission. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, Carl von, Karl Segebrock, and Ewald Ovir. 1897. Zwei früh vollendete Missionare der Evangelisch-lutherischen Mission zu Leipzig. Leipzig: Fr. Richter. [Google Scholar]

- Spear, Thomas. 1996. Struggles for the Land. The Politics & Moral Economies of Land on Mount Meru. In Custodians of the Land. Ecology & Culture in the History of Tanzania. Edited by Gregory Maddox, James L. Giblin and Isaria N. Kimambo. London: James Currey, pp. 213–40. [Google Scholar]

- Spear, Thomas. 1997. Mountain Farmers. Moral Economies of Land & Agricultural Development in Arusha & Meru. Oxford: James Currey. Dar es Salaam: Mkuki wa Nyota. [Google Scholar]

- Struck, Bernhard, Kate Ferris, and Jacques Revel. 2011. Introduction: Space and Scale in Transnational History. The International History Review 4: 573–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tweed, Thomas. 2006. Crossing and Dwelling. A Theory of Religion. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tweed, Thomas. 2011. Theory and Method in the Study of Buddhism. Toward ‘Translocative’ Analysis. Journal of Global Buddhism 12: 17–32. [Google Scholar]

- Weishaupt, Martin. 1912. Evangelisch-Lutherisches Missionsblatt (=ELMB). Available online: https://archivfuehrer-kolonialzeit.de/index.php/bestand-der-evangelisch-lutherischen-mission-in-ostafrika-wakamba-land-von-1886-bis-ende-1892 (accessed on 8 March 2023).

- Werner, Michael, and Bénédicte Zimmermann. 2006. Beyond Comparison: Histoire Croisée and the Challenge of Reflexivity. History and Theory 45: 30–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemon Davis, Natalie. 2010. What is Universal about History? In Transnationale Geschichte: Themen, Tendenzen und Theorien, 2nd ed. Edited by Gunilla Budde, Sebastian Conrad and Oliver Janz. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, pp. 15–20. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fischer, M. „I Die, but I Thank You…!“ Leipzig Mission at Akeri 1896, Squeezed between Its African Addressees and German Colonial Military. Religions 2023, 14, 371. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14030371

Fischer M. „I Die, but I Thank You…!“ Leipzig Mission at Akeri 1896, Squeezed between Its African Addressees and German Colonial Military. Religions. 2023; 14(3):371. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14030371

Chicago/Turabian StyleFischer, Moritz. 2023. "„I Die, but I Thank You…!“ Leipzig Mission at Akeri 1896, Squeezed between Its African Addressees and German Colonial Military" Religions 14, no. 3: 371. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14030371

APA StyleFischer, M. (2023). „I Die, but I Thank You…!“ Leipzig Mission at Akeri 1896, Squeezed between Its African Addressees and German Colonial Military. Religions, 14(3), 371. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14030371