Constancy and Changes in the Distribution of Religious Groups in Contemporary China: Centering on Religion as a Whole, Buddhism, Protestantism and Folk Religion

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Religious Stratification and Mass Religious Conversion

2.2. Integrated Analytical Framework

3. Methods

3.1. Data

3.2. Measures

3.3. Method

4. Results

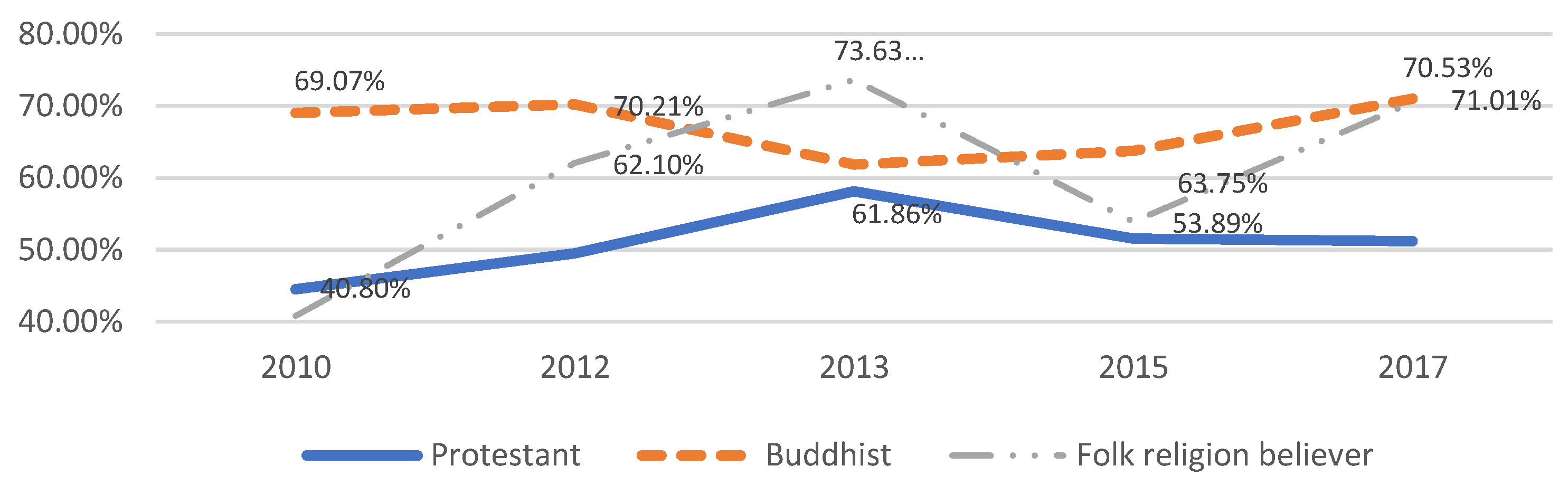

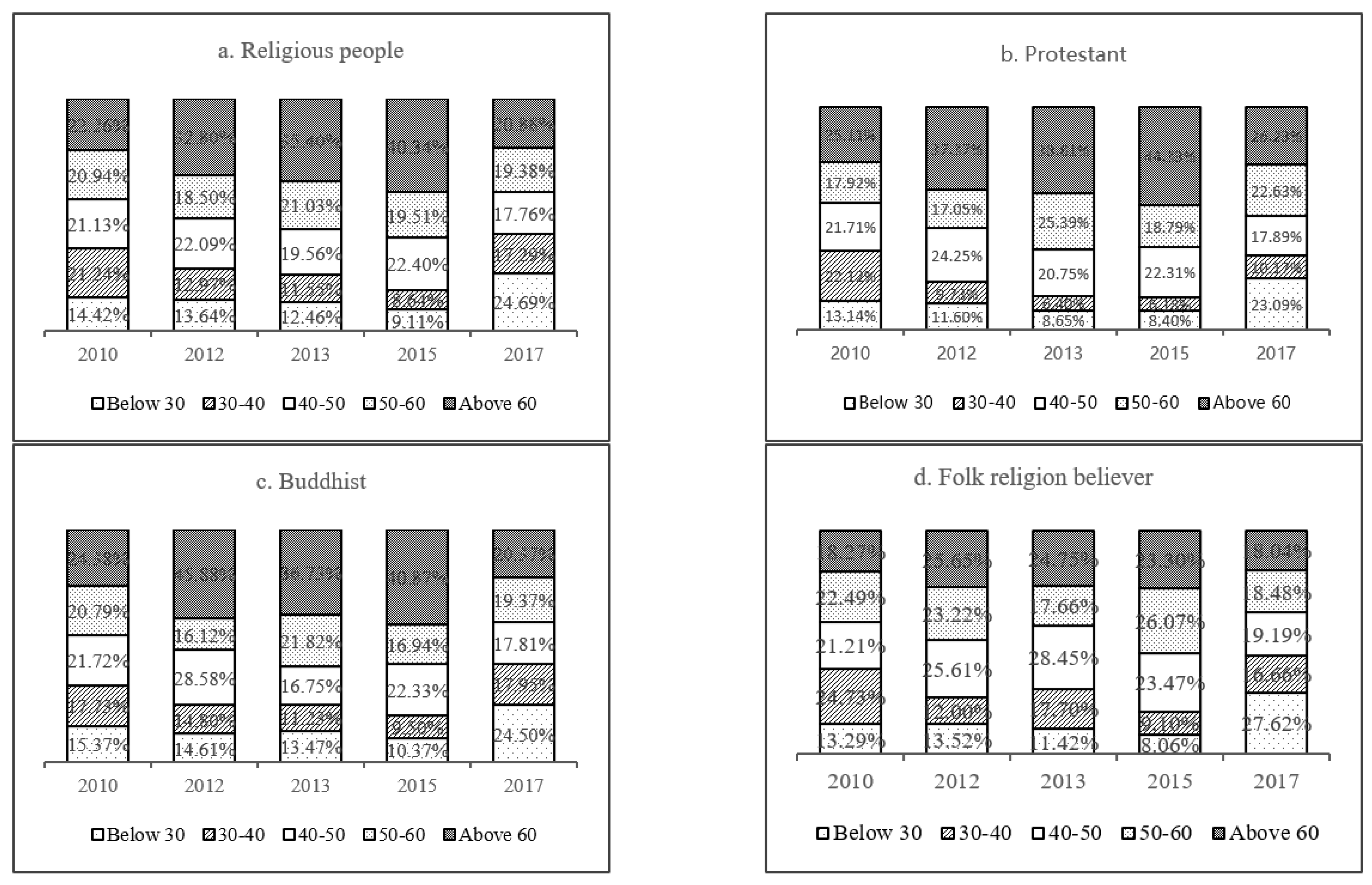

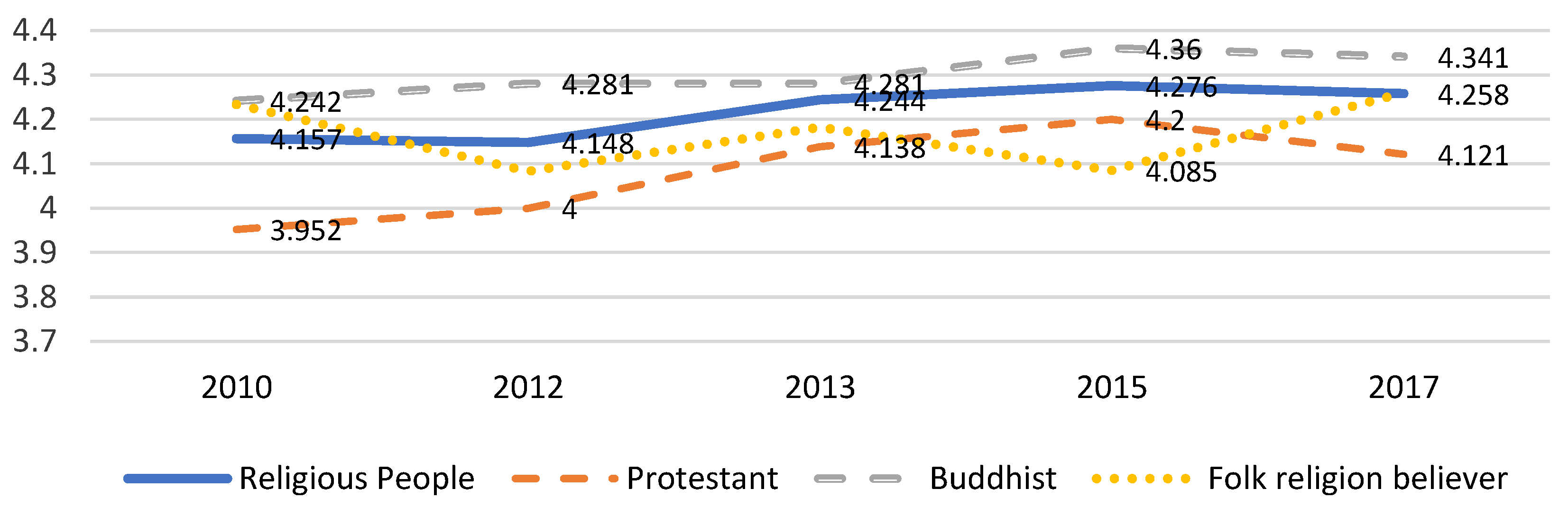

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Analyses

4.2. Binary Logistic Regression of the Full Sample

4.3. Binary Logistic Regression of the Sub-Sample of the Urban/Rural Data

5. Conclusions and Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adam Yuet, Chau. 2006. Miraculous Response: Doing Popular Religion in Contemporary China. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bainbridge, William Sims. 1992. The Sociology of Conversion. In Handbook of Religious Conversion. Edited by H. Newton Malony and Samuel Southard. Birmingham: Religious Education Press, pp. 178–91. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, Peter L., Grace Davie, and Effie Fokas. 2008. Religious America, Secular Europe?: A theme and Variation. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Bosworth, Hayden B., Kwang-Soo Park, Douglas R. McQuoid, Judith C. Hays, and David C. Steffens. 2003. The Impact of Religious Practice and Religious Coping on Geriatric Depression. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 18: 905–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, Robert. 1989. Crashing the Gates. New York: Sim. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, Harvey. 2013. The Secular City: Secularization and Urbanization in Theological Perspective. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, Kangsheng, and Yao Peng. 2000. Sociology of Religion. Beijing: Social Science Academic Press. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, James D. 2008. Religious Stratification: Its Origins, Persistence, and Consequences. Sociology of Religion 69: 371–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, James D., Ralph E. Pyle, and David V. Reyes. 1995. Persistence and Change in the Protestant Establishment, 1930–1992. Social Forces 74: 157–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerath, Nicholas Jay. 1965. Social Class in American Protestantism. Chicago: Rand MacNally and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Leiming, and Hua Yang. 2014. The Current Situation of Western Religion Spreading in Chinese Rural—Research Report of Longyuan Foundation. In Research on Marxist Atheism. Edited by Xi Wuyi. Beijing: China Social Sciences Press, vol. 4, pp. 222–37. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, Qi. 2013. The Change and Influence of Urbanization on Christianity in China. In Recent Review of Christian Thoughts. Edited by Xu Zhiwei. Shanghai: Shanghai Century Publishing Group, vol. 16, pp. 188–206. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Lizhu, and Na Chen. 2014. Conversion and Indigenous Religion in China. In The Oxford Handbook of Religious Conversions. Edited by Lewis Rambo and Charles Farhadian. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 556–77. [Google Scholar]

- Fiedler, Katrin. 2010. China’s ‘Christianity Fever’ Revisited: Towards a Community-Oriented Reading of Christian Conversions in China. Journal of Current Chinese Affairs 39: 71–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freese, Jeremy. 2004. Risk Preferences and Gender Differences in Religiousness: Evidence from the World Values Survey. Review of Religious Research 46: 88–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, Thomas. 1985. After Comradeship: Personal Relations in China since the Cultural Revolution. China Quarterly 104: 657–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guangjin, Chen. 2013. Not Only ‘the Relative Deprivation’, and ‘the Existential Anxiety’—Empirical Analysis of Ten Years’ Changes of Chinese Subjective Identification Stratum Distribution. Heilongjiang Social Sciences 5: 76–88. [Google Scholar]

- He, Rong, and F. Carson Mencken. 2010. An Examination of Religious Faiths and Social Economic Status in Contemporary China. The Religious Cultures in the World 6: 14–20. [Google Scholar]

- Idler, Ellen L. 1987. Religious Involvement and the Health of the elder: Some Hypotheses and an Initial Test. Social Forces 66: 226–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jindra, Ines W. 2011. How Religious Content Matters in Conversion Narratives to Various Religious Groups. Sociology of Religion 72: 275–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, David K. 1993. The Glyphomancy Factor: Observation on Chinese Conversion. In Conversion to Christianity: Historical and Anthropological Perspectives on a Great Transformation. Edited by Robert W. Hefner. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 285–304. [Google Scholar]

- Kilbourne, Brock, and James T. Richardson. 1989. Paradigm Conflict, Types of Conversion, and Conversion Theories. Sociological Analysis 50: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koesel, Karrie J. 2013. The Rise of a Chinese House Church: The Organizational Weapon. China Quarterly 215: 572–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Peilin. 2005. Social Conflict and Class Consciousness—Study on the Social Contradictions in Contemporary China. Chinese Journal of Sociology 25: 7–27. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Li, Xiangping. 2010. Believing without Identifying: A Sociological Interpretation of Belief in Contemporary China. Beijing: Social Science Academic Press. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Jialin. 1999. Chinese Rural Churches Since the Reform and Opening Up. Hong Kong: Alliance Bible Seminary. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Yanwu, and Hua Yang. 2022. An Analysis on the Empirical Studies of Religions in Chinese Rural Areas: A Response to the Paper ‘Western Religion Fever in Rural China: Myth or Truth’? Science and Atheism 137: 28–37. [Google Scholar]

- Lofland, John, and Rodney Stark. 1965. Becoming a World-Saver: A Theory of Conversion to a Deviant Perspective. American Sociological Review 30: 862–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Yunfeng, and Chunni Zhang. 2016. Observation in Present Situation of Contemporary Chinese Christian: Based on the Survey Data from CGSS and CFPS. The Religious Cultures in the World 1: 34–46+158. [Google Scholar]

- Madsen, Richard. 2003. Catholic Revival During the Reform Era. China Quarterly 174: 468–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Alan S., and John P. Hoffmann. 1995. Risk and religion: An explanation of gender differences in religiosity. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 34: 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Alan S., and Rodney Stark. 2002. Gender and Religiousness: Can Socialization Explanations Be Saved? American Journal of Sociology 107: 1399–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niebuhr, H. Richard. 1929. The Social Sources of Denominationalism. New York: Henry Holt. [Google Scholar]

- Oostveen, Daan F. 2019. Religious Belonging in the East Asian Context: An Exploration of Rhizomatic Belonging. Religions 10: 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, Liston. 1953. Religion and the Class Structure. In Class, Status, Power. Edited by Rainhard Bendix and Seymour Martin Lipset. Glencoe: Free Press, pp. 316–23. [Google Scholar]

- Pyle, Ralph E. 2006. Trends in Religious Stratification: Have Religious Group Socioeconomic Distinctions Declined in Recent Decades? Sociology of Religion 67: 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Guangqiang. 2016. Research on Social Stratification: Objective and Subjective Dimensions. Journal of Socialist Theory Guide 9: 35–37+49. [Google Scholar]

- Rambo, Lewis Ray. 1993. Understanding Religious Conversion. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, James T. 1985. The Active vs. Passive Convert: Paradigm Conflict in Conversion/Recruitment Research. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 24: 163–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roof, Wade Clark, and William McKinney. 1987. American Mainline Religion: Its Changing Shape and Future. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, Rongping, Zheng Fengtian, and Liu Li. 2015. Religious Believes and Farmer’s Participation in Rural Endowment. China Rural Survey 1: 71–83+95–96. [Google Scholar]

- Snow, David A., and Richard Machalek. 1984. The Sociology of Conversion. Annual Review of Sociology 10: 167–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, Rodney, and Roger Finke. 2000. Acts of Faith: Explaining the Human Side of Religion. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Suchman, Mark C. 1992. Analyzing the Determinants of Everyday Conversion. Sociological Analysis 53: S15–S33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Liping, Wang Hansheng, Wang Sibin, Lin Bin, and Yang Shanhua. 1994. Social Structural Change Since the Reform. Chinese Social Sciences Quarterly (Hongkong) 1: 47–62. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Yanfei. 2014. Unprecedented Variation: Changes in Chinese Religious Ecological Pattern. Academia Bimestrie 2: 11–25. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Yanfei. 2017. The Rise of Protestantism in Post-Mao China: State and Religion in Historical Perspective. American Journal of Sociology 122: 1664–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The State Council Information Office of the P. R. C. 2008. China’s Policies and Practices on Protecting Freedom of Religious Belief. Available online: http://www.scio.gov.cn/ztk/dtzt/37868/38146/index.htm (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Wu, Yue, Zhang Chunni, and Lu Yunfeng. 2020. Western Religion Fever in Rural China: Myth or Truth? An Analysis Based on China Family Panel Studies (CFPS). Open Times 3: 157–67. [Google Scholar]

- Wuthnow, Robert. 1988. The Restructuring of American Religion. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Fenggang, and Andrew Abel. 2014. Sociology of Religious Conversion. In The Oxford Handbook of Religious Conversions. Edited by Lewis Rambo and Charles Farhadian. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 140–63. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Fenggang, and Brian L. McPhail. 2023. Measuring Religiosity of East Asians: Multiple Religious Belonging, Believing, and Practicing. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Fenggang, and Joseph B. Tamney. 2006. Exploring Mass Conversion to Christianity among the Chinese: An Introduction. Sociology of Religion 67: 125–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Fenggang. 1998. Chinese Conversion to Evangelical Christianity: The Importance of Social and Cultural Contexts. Sociology of Religion 59: 237–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Fenggang. 2005. Lost in the Market, Saved at McDonald’s: Conversion to Christianity in Urban China. Journal for the Social Scientific Study of Religion 44: 423–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Fenggang. 2014. What about China? Religious Vitality in the Most Secular and Rapidly Modernizing Society. Sociology of Religion 75: 564–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Chunni, and Yunfeng Lu. 2020. The measure of Chinese religions: Denomination-based or deity-based? Chinese Journal of Sociology 6: 410–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Feng, and Hong Yin. 1988. A Preliminary Study on the Current Situation and Reasons of Chinese Religious Women. Religious Studies 1: 66–70. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Fengtian, Ruan Rongping, and Liu Li. 2010. Social Security and Religions Beliefs. China Economic Quarterly 9: 829–50. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Lang, and Qiuyun Sun. 2017. The Psychology of Peasant Religious Conversion for the Purpose of Disease Control:The Role of ‘Belief’ in Understanding Chinese Rural Religious Practices. Chinese Journal of Sociology 37: 1–31. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Xiaohong. 2005. Survey of the Chinese Middle Classes. Beijing: Social Science Academic Press. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

| Buddhist | Taoist | Catholic | Protestant | Folk Religion Believer | Religious Believer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CGSS2010 | 5.48% | 0.25% | 0.23% | 1.93% | 2.89% | 13.74% |

| CGSS2012 | 6.02% | 0.26% | 0.20% | 2.31% | 3.43% | 14.44% |

| CGSS2013 | 5.66% | 0.32% | 0.32% | 1.88% | 2.05% | 11.44% |

| CGSS2015 | 4.74% | 0.27% | 0.18% | 2.11% | 1.68% | 10.63% |

| CGSS2017 | 4.66% | 0.23% | 0.20% | 1.41% | 2.11% | 10.61% |

| Total | 5.31% | 0.26% | 0.23% | 1.92% | 2.44% | 12.18% |

| Religious Believer | Protestant | Buddhist | Folk Religion Believer | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Man | 39.32% | 28.92% | 37.86% | 48.98% |

| Woman | 60.68% | 71.08% | 62.14% | 51.02% | |

| χ2 | 339.94 *** | 216.83 *** | 215.679 *** | 1.688 | |

| Urban/rural | Urban | 61.76% | 50.64% | 67.31% | 59.42% |

| Rural | 38.24% | 49.36% | 32.69% | 40.58% | |

| χ2 | 0.414 | 44.435 *** | 50.425 *** | 2.078 |

| Age | Health | Education | Income | Subjective Class | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Religion as a whole | Believers | 50.608 | 3.420 | 7.667 | 10.218 | 4.210 |

| None | 47.293 | 3.622 | 9.185 | 10.278 | 4.171 | |

| T-test | −14.175 *** | 13.388 *** | 22.546 *** | 0.751 | −1.613 | |

| Protestantism | Believers | 52.656 | 3.320 | 7.396 | 9.828 | 4.076 |

| None | 47.482 | 3.607 | 9.030 | 10.277 | 4.185 | |

| T-test | −10.128 *** | 8.662 *** | 11.084 *** | 8.667 *** | 1.963 ** | |

| Buddhism | Believers | 50.880 | 3.451 | 8.095 | 10.365 | 4.297 |

| None | 47.397 | 3.610 | 9.049 | 10.263 | 4.177 | |

| T-test | −11.155 *** | 7.826 *** | 10.130 *** | −3.151 ** | −3.852 *** | |

| Folk religion | Believers | 48.611 | 3.420 | 6.931 | 10.217 | 4.169 |

| None | 47.556 | 3.606 | 9.050 | 10.269 | 4.183 | |

| T-test | −2.322 * | 6.327 *** | 16.195 *** | 1.292 | 0.320 | |

| Religious Believer | Buddhist | Protestant | Folk Religion Believer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.408 *** (0.039) | 0.477 *** (0.052) | 1.004 *** (0.089) | −0.297 *** (0.079) |

| Age | 0.003 + (0.001) | 0.007 *** (0.002) | 0.013 *** (0.003) | −0.0147 *** (0.003) |

| Health | −0.096 *** (0.019) | −0.079 ** (0.024) | −0.074 + (0.039) | −0.128 *** (0.036) |

| Education | −0.058 *** (0.005) | −0.038 *** (0.007) | −0.009 (0.010) | −0.125 *** (0.010) |

| Income | 0.068 *** (0.017) | 0.108 *** (0.026) | −0.040 (0.023) | 0.114 ** (0.035) |

| Subjective class | 0.035 ** (0.011) | 0.036 * (0.015) | −0.002 (0.025) | 0.0407 + (0.022) |

| Area | −0.203 *** (0.045) | −0.378 *** (0.062) | 0.378 *** (0.091) | −0.187 * (0.088) |

| Ethnicity | 0.410 *** (0.066) | −0.069 (0.093) | −1.137 *** (0.205) | 0.662 *** (0.101) |

| Marriage | −0.103 * (0.047) | −0.191 ** (0.061) | −0.094 (0.099) | 0.113 (0.103) |

| Wave | −0.047 *** (0.008) | −0.029 ** (0.011) | −0.027 + (0.015) | −0.090 *** (0.017) |

| Constants | 0.003 + (0.001) | 0.007 *** (0.002) | 0.013 *** (0.003) | −0.015 *** (0.003) |

| Observations | 50,322 | 51,660 | 51,660 | 51,660 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.026 | 0.02 | 0.046 | 0.039 |

| Religious Believer | Buddhist | Protestant | Folk Religion Believer | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| City | Rural | City | Rural | City | Rural | City | Rural | |

| Gender | 0.375 *** (0.050) | 0.522 *** (0.065) | 0.466 *** (0.063) | 0.556 *** (0.095) | 0.863 *** (0.123) | 1.178 *** (0.131) | −0.289 ** (0.104) | −0.176 (0.121) |

| Age | −0.001 (0.002) | 0.010 *** (0.003) | 0.005 * (0.002) | 0.014 *** (0.004) | 0.010 ** (0.004) | 0.017 *** (0.005) | −0.027 *** (0.004) | 0.002 (0.005) |

| Health | −0.113 *** (0.025) | −0.087 ** (0.0275) | −0.105 *** (0.031) | −0.053 (0.040) | −0.123 * (0.058) | −0.046 (0.053) | −0.135 ** (0.051) | −0.136 ** (0.052) |

| Education | −0.084 *** (0.006) | −0.002 (0.009) | −0.055 *** (0.008) | 0.012 (0.013) | −0.037 ** (0.012) | 0.034 * (0.016) | −0.182 *** (0.012) | −0.036 * (0.018) |

| Income | 0.073 ** (0.026) | 0.074 ** (0.023) | 0.096 ** (0.037) | 0.146 *** (0.039) | −0.041 (0.035) | −0.036 (0.031) | 0.168 ** (0.062) | 0.084 * (0.041) |

| Subjective class | 0.061 *** (0.015) | −0.003 (0.0174) | 0.059 ** (0.019) | −0.008 (0.025) | 0.012 (0.036) | −0.016 (0.033) | 0.080 ** (0.029) | −0.006 (0.033) |

| Ethnicity | 0.205 + (0.113) | 0.539 *** (0.083) | −0.028 (0.130) | −0.114 (0.131) | −0.855 ** (0.281) | −1.308 *** (0.291) | −1.053 ** (0.321) | 1.327 *** (0.123) |

| Marriage | −0.177 ** (0.058) | 0.028 (0.082) | −0.241 *** (0.072) | −0.066 (0.120) | −0.298 * (0.130) | 0.172 (0.155) | 0.159 (0.136) | 0.054 (0.157) |

| Wave | −0.048 *** (0.011) | −0.049 *** (0.013) | −0.045 ** (0.014) | 0.001 (0.018) | −0.025 (0.0210) | −0.030 (0.022) | −0.068 ** (0.022) | −0.142 *** (0.028) |

| Constants | 95.045 *** (21.102) | 95.106 *** (25.261) | 86.590 ** (27.462) | −6.971 * (35.249) | 47.347 * (42.303) | 55.937 * (43.907) | 134.711 ** (44.60) | 280.597 *** (56.30) |

| Observations | 30,448 | 19,874 | 31,227 | 20,433 | 31,227 | 20,433 | 31,227 | 20,433 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.035 | 0.021 | 0.026 | 0.015 | 0.043 | 0.046 | 0.060 | 0.050 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, F.; Wang, Q. Constancy and Changes in the Distribution of Religious Groups in Contemporary China: Centering on Religion as a Whole, Buddhism, Protestantism and Folk Religion. Religions 2023, 14, 323. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14030323

Li F, Wang Q. Constancy and Changes in the Distribution of Religious Groups in Contemporary China: Centering on Religion as a Whole, Buddhism, Protestantism and Folk Religion. Religions. 2023; 14(3):323. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14030323

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Feng, and Qian Wang. 2023. "Constancy and Changes in the Distribution of Religious Groups in Contemporary China: Centering on Religion as a Whole, Buddhism, Protestantism and Folk Religion" Religions 14, no. 3: 323. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14030323

APA StyleLi, F., & Wang, Q. (2023). Constancy and Changes in the Distribution of Religious Groups in Contemporary China: Centering on Religion as a Whole, Buddhism, Protestantism and Folk Religion. Religions, 14(3), 323. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14030323