1. Introduction

The Jingci Monastery 净慈寺 in Hangzhou located close to the West Lake has played a crucial role in the history of Chinese Buddhism since its founding. Established by Qian Chu 錢俶 (929–988) in the capital city of his Wuyue Kingdom, this site soon served as one of the Five Mountains in the Song Dynasty. Such prestige made it an exceptional Buddhist “academy” nationwide. For centuries, it trained monks not only from other regions in China but also from Korea and Japan. It was an institution that contributed to the training of priests and the spreading of scholastic teachings in East Asia. In a broad sense, the Jingci Monastery has its part in shaping the form of East Asian Buddhism. With such a role in history, Jingci Monastery become a location that preserves traces of transnational religious activities in history, including textual records as well as physical presentations such as statues, stupas, steles and so forth.

Nevertheless, a cautious examination of the validity of these materials is necessary before they all become viewed as history. Concerning that various interests could lead to biases in narratives, the issue of historical accuracy should be addressed when encountering a religious site and the story it narrates. With such intent, this paper inspects the history of a specific stupa located within the Jingci Monastery. It is dedicated to Tiantong Rujing 天童如浄 (1163–1228), a Song eminent monk who served as the monastery’s abbot two times in his life. His posthumous influence in pre-modern China was obscure. As a contrast, Rujing is now known for his role as the master who trained Dōgen 道元 (1200–1253), a key figure in Japanese Buddhism. Although the relationship between Rujing and Dōgen has made the Rujing Stupa a place for transnational pilgrimage, little investigation has been conducted to elucidate its formation.

This research set out to clarify the history of the Rujing Stupa and contrast it to the narratives in textual records, including the very inscription from the stele found on this site. While it is often assumed that stele inscriptions at a historical site explain its origins, this research suggests that such on-site information can also be historical reinventions grounded in narratives. In the case of the Rujing Stupa, the narratives that impacted the stele inscription came from Japanese pilgrims who attempted to stress the significance of this architecture. Considerable evidence suggests that while claiming to be 13th-century architecture, the current Rujing Stupa is in fact a modern construction initiated by Sōtō communities in the 1980s.

This study draws materials from a variety of records for evidence. To address the questions on the related history and narrative, Rujing’s biographical information is carefully examined through textual comparison between the modern stele inscription and the pre-modern Chinese records, especially the lamp records (denglu 燈錄) and biographies of eminent monks. Travel logs and memorial articles composed by Japanese pilgrimages in the 19 and 20th centuries, on the other hand, provide direct evidence that the current Rujing Stupa is a result of construction by Japanese pilgrims. Together, analyses of these primary materials demonstrate a historical image of the Rujing Stupa and provide insights into the study of sacred sites in a more contextualized manner.

Current scholarship on the issue of the Rujing Stupa is limited. Rujing as a Chinese Chan figure receives little attention in Chinese scholarship because no prominent dharma lineage has been found in Chinese records, and only a few of his works survive today. On the other hand, the study of Rujing by Japanese scholars has been a well-established field. In the 1980s, Kagamishima Genryū 鏡島元隆 published a series of articles and a monograph titled Tendō Nyojō Zenji no kenkyū 天童如浄禅師の研究, in which he encapsulated the life and thoughts of Rujing through the studies on the recorded sayings of the figure. Subsequently, Satō Hidetaka 佐藤秀孝 examined further details on Rujing’s biography, including his dharma transmission, interactions with contemporaries, and so forth. In recent years, Nagai Kenryu 永井賢隆 has engaged in the discussion on the doctrines and practices promoted by Rujing. A noteworthy commonality among the authors is that they all received academic training from Sōtō-affiliated institutions in Japan, namely the Komazawa University and the Center of Comprehensive Sōtō Studies, where the bulk of their research has been published. The persistent interest in Rujing in Japan, as noted earlier, stems from the fact that the Chinese master’s disciple, Dōgen, was the founder of the Sōtō tradition. Given Dōgen’s crucial role in this school, a thorough study of his dharma transmission is of great importance. In essence, Rujing holds value in Japanese academia because of his association to Dōgen.

However, these studies face issues as they elaborate on Rujing’s life, thoughts, and practices through the lens of the Sōtō lineage. While the recorded sayings of Rujing are included as source material, many of the studies rely heavily on Dōgen’s works as primary sources to investigate Rujing’s teachings. This implies that Dōgen’s records on the master are non-biased description, and that the master and his disciple shared identical thoughts and practices. English scholars of Dōgen, such as Steven Heine and Griffith Foulk have noted that such an implication cannot be not valid. Foulk clarified that Dōgen did not take Rujing’s words of “just sit” literally, but in some cases, used his words as a kōan (

Foulk 2015); Heine examined Dōgen’s works and pointed out that Rujing was not frequently mentioned until the early 1240s, long after he went back to Japan (

Heine 2006, p. 119). Both studies suggest that a careful differentiation between Rujing and Dōgen is beneficial in studying these two figures.

Reflecting on Japanese scholars, Atago Kuniyasu 愛宕邦康 pointed out in his article that the past studies on Rujing reflected a biased perspective. He stated that out of sectarian concerns, scholars prioritized the Japanese sources in the studies, and entrusted Dōgen’s perspective even when it contradicted Chinese sources about Rujing (See

Atago 2021). Atago suggests that a methodology contextualizing Rujing studies in Chinese historical background is necessary. This will ensure that future studies avoid a sectarian narrative that solely addresses Sōtō interests.

While this paper does not constitute doctrinal research on Rujing and his teachings as they passed through Dōgen, it addresses Atago’s statement through the lens of historiography. The objective of this study is to promote awareness of the various narratives that have shaped and reinvented the identity of a Buddhist figure with transnational impact. In this sense, the contrast of scholarly attention to Rujing in Chinese and Japanese languages is itself a message, a message that resonates with the Japanese Buddhist’s construction activities in China.

This paper consists of three sections. The first section examines Rujing’s biographical information preserved in China. By synthesizing the historical records and comparing them to the on-site stele inscription, this section highlights the inaccuracy of Rujing’s biography as presented in the stele inscription. Further, the claim of the Stupa as the original receptacle of Rujing’s relics cannot be valid, as it contradicts a few pre-modern records. The second section of this paper focuses on the Japanese perspective concerning the first construction of the Rujing Stupa in the late 19th century. Additionally, it analyzes the religious and socio-political motives behind this event. The third section explores the reconstruction of the Rujing Stupa in the 1980s, a project that involved both Chinese and Japanese Buddhist communities, as well as the two states. Together, these discussions indicate the significant influence of narratives in shaping a sacred site and emphasize the importance of tackling this issue in future research.

2. Examinations on the Biographies of Rujing

Steles are important source materials for scholars in historical studies in East Asia because of their common existence at various sites for diverse purposes. In the context of Buddhism, stele are often used as claims of properties, testimonials of eminent figures, memorial of significant events, warnings for transgressional activities, and so forth. Besides the content it carries, the media itself delivers a message. Since the stone items installed at a location are available to all who visit the site and at the same time are difficult to remove, the presence of a stele serves as a proclamation itself, a public announcement made to a wide audience both geographically and temporarily.

The stele examined in this study is a biography (

zhuan 傳)—“The Biography of the Chan Master Rujing” (

Rujing chanshi zhuan 如浄禪師傳). Erected next to the Rujing Stupa, it can be categorized as a testimonial of a Buddhist figure. However, as will be explained in this section, the stele inscription is not a sheer introduction to the monk’s life, but a narrative that carries multiple intentions of Japanese Buddhists. The stele inscription is as follows:

“The Chan master Rujing’s courtesy name is Zhangweng 長翁, and his family name Yu 俞. He was born in Weijiang 苇江, Mingzhou 明州 in 1162 CE. He had never been interested in secular affairs and became a monk when he was young. At the age of nineteen, he went to Mt. Xuedou 雪竇, studied with Chan master Zu’an Jian 足庵鑒, received the dharma transmission from him, and became the thirteenth legitimate patriarch

1 of the Caodong lineage. He had been the abbot of Qingliang Monastery 清涼寺 in Jiankang 建康, Ruiyan Jingtu Monastery 瑞巌净土寺 in Taizhou 台州, as well as Jingci Monastery in Hangzhou. After spending twenty years in these monasteries listed above, he was assigned to the Jingde Monastery 景德寺 in Tiantong Mountain. He had been the abbot there for four years…Passed away at the age of sixty-six, his body was sent back to Jingci Monastery in Hangzhou, and was buried here. His tomb-stupa remains today… In regards to the people who obtained dharma transmission from him… one of them was Eihei Dōgen. He traveled abroad to visit Master Jing, and received the recognition as a dharma heir. (Rujing) granted him Master Furong Kai’s

2 芙蓉楷 sacerdotal robe as well as the dharma writings. Upon Dōgen’s return to Japan, he established the Sōtō school. Sophisticated in teachings and extraordinary in practicing, it flourished…how majestic a high peak Master Jing is, as the one who initiated the tradition!”

One thing that stands out in this passage is that, despite being a biography of Rujintg, it spends a considerable length introducing Dōgen, and ends the biography by exalting Rujing for his connection to the Japanese Sōtō tradition. The author highlights Rujing’s significance in such a connection, in fact, a great portion of the information in this passage comes from Japan and cannot be found in pre-modern Chinese records. This section therefore draws materials from a variety of pre-modern sources to examine where the biographical information in the modern inscription most likely makes reference. As evidence from pre-modern source will show, this inscription could not be regarded as a valid historical record as it is a purposely composed statement on Rujing’s significance for the Sōtō tradition.

Firstly, the claim of Rujing’s being buried at Jingci Monastery is spurious. When searching for Rujing’s biographical records in Chinese records, there is very limited information about him. Although Rujing’s sayings are preserved in the Song works such as

Chanzong songgu lianzhu tongji 禪宗頌古聯珠通集, in the Song

denglu literature, records of the Caodong lineage stopped right at Rujing’s master, Zhijian 智鑒. The earliest biographies of Rujing are seen in Chinese collections that date back to the Ming Dynasty. In

Wudeng huiyuan xulue 五燈會元續略, an entry for Rujing offers limited biographical information. The same biography was recorded in the later

Ji Denglu 繼燈錄. Both of them were works from the Ming Dynasty. While it describes Rujing as a person “born intelligent and unlike other children”, no information was available for his place of birth. It also suggests that while Rujing had changed his place of residence six times among monasteries, he did not appoint anyone as his dharma heir. The last part of this entry states that after the master passed away, “his whole body was preserved in a stupa in the local mountain” (See

Jingzhu 1644, p. 453).

The local mountain refers to Mt. Tiantong in Ningbo because according to the biography, Tiantong is where Rujing spent his last years. This would raise questions about the modern narratives of Rujing Stupa as a receptacle for Rujing’s relics “sent back” to Jingci, Hangzhou. No evidence could be found about an event of “relocation” of this stupa from Ningbo to Hangzhou, nor is it possibly a favored activity in Chinese tradition. Another piece of evidence that questions the existence of a stupa at Jingci built soon after Rujing’s death is that in the two temple gazetteers of Jingci Monastery (one complied in the Ming Dynasty, and another in the Qing)—within which the stories of all sites were elaborated—there is no record about the stupa. Moreover, in the two temple gazetteers, there is no record of Rujing the person. It appears that, though Rujing had been the abbot of Jingci twice, for centuries the monastery did not appreciate this memory much.

Along the same lines, the obscurity of Rujing in Chinese records entails another question in the source of other biographical information in the modern inscription. In fact, the place of birth Weijiang, and the Rujing’s family name, Yu, both come from a text exclusively preserved in Japan, the

Rujing chanshi xuyulu 如淨禪師續語錄. While it is claimed to be a supplemental recorded sayings for the original one, modern scholars such as Kagamishima Genryu 鏡島元隆 and He Yansheng 何燕生 have pointed out that the

Xuyulu cannot be the authentic work of Rujing (See

Kagamishima 1983). He also notes that the reason for Japanese Buddhists in the Edo period to compose this work and attribute it to Rujing is that the Chinese master is known for transmitting dharma to Dōgen. Using Rujing’s name to “endorse” the actual author’s own thought reflects that Rujing was considered a symbol of doctrinal authenticity in the Japanese context (See

He 1996).

Since the matter of authenticity associated with Rujing is valued so much in Japan, it is not surprising that in the Jingci inscription, the description of Dōgen receiving Furong Daokai’s 芙蓉道楷 sacerdotal robe originated from Japanese records as well. Satō Hidetaka states that the earliest source that includes this story is the

Keizenki 建撕記 composed by a 15th-century Sōtō monk Keizen (1415–1474) (See

Satō 1997). As William Bodiford points out, this work is a hagiography of Dōgen full of myth and extended anecdotes that serve to promote the patriarch’s memory (

Bodiford 2006). The story of Rujing granting Daokai’s robe to Dōgen cannot be traced in any Chinese texts, in fact, nor can it be found in Dōgen’s own works. These facts suggest that this event was recorded and appreciated by later Sōtō Buddhists for their sectarian interests.

As examined so far, many texts in the modern inscription are drawn from Japanese sources, which either contradicts the Chinese records, or are not known in China. Rujing is barely an influential figure in Chinese pre-modern history, yet in Japan he received great attention because of Dōgen. Interestingly, with more frequent communication between the Japanese and Chinese Caodong/Sōtō schools, Rujing’s reputation started to raise interests in Chinese Buddhist communities in the early modern era. In the abovementioned Ming-Qing record

Ji Denglu, under the entry of Rujing, there is a biography of Dōgen, titled “Chan Master Eihei Dōgen of Japan” 日本永平道元禪師. It elaborates how Dōgen became a monk at a young age, traveled to China, studied under multiple Chan masters and became close with Rujing, and how he founded Eiheiji and was venerated in all the Sōtō monasteries in Japan. At the end of the biography, there is commentary from a Chinese monk, Daopei 道霈 (1615–1702), who was the disciple of the editor of

Ji Denglu. He explained how such a biography came into Chinese records:

“Dōgen received the dharma transmission from patriarch Tiantong Jing. He was the founder of the Sōtō sect in Japan, yet the

Xu Denglu failed to record this. Recently, there are Chan masters that come reversely

3, who turn out to be Dōgen’s successors. They copied the inscription of the biographical stele of Dōgen and sent it here through a trade boat…It was until then I realized that in history, there must be many successors of the dharma scattered all over the world who were forgotten, just like the story of Dōgen…Therefore, I utilized the inscription and made a biography of him, and listed Dōgen below the entry of his master. This could not only keep the reputation of the past master but also leave records for readers in the future.

4”

This record from a Chinese perspective suggests that it was not until in the late Ming Dynasty that Dōgen and the Sōtō lineage became known by Chinese Buddhists. Before being aware of Dōgen’s influence in Japan, Chinese monks did not take Rujing as an important figure in the history of Chan. Accordingly, the information about Rujing’s disciples was even more obscure than the master himself. In many other denglu literature, there were only names of Rujing disciples, and no other biographical information was recorded. It is safe to say that Rujing’s lineage started to attract greater attention from Chinese Buddhists centuries after he passed away. Dōgen’s biography in Ji Denglu is without question a unique case in Chinese records. Yet in some sense, it explains why records about this master were obscure in the Song Dynasty, yet curiously increasing in the Ming and Qing Dynasties.

In this section, I traced the textual records about Rujing from the Southern Song Dynasty to the contemporary period and compared the influence of this figure in China and Japan respectively. Comparing the Jingci stele inscription to a broad variety of sources, several findings were found and are listed as follows:

The location of the original Rujing Stupa is most likely in Ningbo instead of Hangzhou. This is because Rujing spent his last years at the Tiantong Monastery in Nongbo, and according to the denglu records, was buried at a local mountain. The absence of Rujing Stupa’s record in the temple gazetteers of Jingci Monastery added more doubt to the authenticity of the stupa in Hangzhou—if it ever existed.

Because of the lack of influential disciples who kept on spreading his words and teachings, Rujing was almost forgotten in the Chinese context for a long period. However, texts were composed in Japan which provide detailed biographical information about the master, even though the credibility is subject to further examination as these works were composed to promote his disciple Dōgen’s prestige.

It was until the record about Dōgen as well as the significance of Sōtō tradition were introduced to China through international trade in the late Ming, that people in China started to appreciate the role Rujing played in the history of Chan Buddhism.

The goal of such textual analyses does not end in questioning the validity of the inscription. Several questions to ask based on these findings are as follows, why was the stele inscription composed thoroughly under the influence of Japanese narratives, and how was it established at the Jingci Monastery together with the Stupa that was not supposed to be at the location? In the next section, I will elaborate the history of constructing the stupa with an exploration of modern Japanese records.

3. Constructing the Sacred Site in 1879–1880

In 1912, Kuruma Takudō 来馬琢道 (1877–1964), a Sōtō priest embarked on a pilgrimage to multiple Chinese locations with significance in Buddhist history. He traveled in the Zhejiang and Jiangsu Provinces of China and visited important religious sites in Shanghai, Hangzhou, Suzhou, Nanjing, Zhenjiang, Ningbo, Mount Putuo, and so forth. In So Setsu Kengakuroku 蘇淅見学録, a book recording his travels in the two Chinese Provinces—Jiangsu and Zhejiang, Kuruma especially noted that he followed the instruction of another Japanese Sōtō priest, Mizuno Baigyō 水野梅曉 (1877–1949), and found the “reconstructed Tiantong Rujing Stupa” at Jingci Monastery in Hangzhou.

Kuruma further explained the origin of this stupa as follows: when the Sōtō priest, Takita Yūchi 滝田融智 (1837–1912), went to China decades ago, he visited the Tiantong monastery and was disappointed that there was no stupa for Rujing there. Thus, Takita decided to reconstruct the stupa for the patriarch. He managed to purchase a piece of land at the Jingci Monastery of Hangzhou, reconstructed a stupa, and established a stele beside it (

Kuruma 1913, pp. 30–31). Takita shared the news about the construction upon going back. However, when Mizuno Baigyō later visited Jingci Monastery, he failed to find the site because it was located at the back of the temple. For a time, Takita was doubted for lying. It was Kuruma’s trip in 1912 that confirmed the genuineness of Takita’s words. In

Tōjō kōsō gettan 洞上高僧月旦, a collection of biographies of eminent Sōtō monks published in 1893, the author provided details in Takita’s constructing of the Rujing Stupa in Hangzhou.

“One of Master Takita’s greatest achievements is that, in the late Meji twelve (1879) and early thirteen (1880), the master entered inland China and established Chan Master Rujing’s precious stupa at the Jingci Monastery. Anyone who knows about the situation in China understands how dangerous it was, and still is to go to inland China as a foreigner…Yet the master, out of his admiration of Rujing… traveled from Shanghai to Ningbo, and arrived at the Tiantong Monastery. He observed the situation of Chinese Buddhism, and witnessed the chaos and corruption of Buddhism there…He left Tiantong for Jingci Monastery in order to pay homage to Rujing’s stupa, yet nobody knew the actual location, nor did he did find any traces of the architecture. The master was frustrated…therefore, he took a great vow. He went back to Japan and raised funds from priests and laymen, and sailed to China to establish a seamless stupa at the Jingci Monastery, where Rujing was buried…Chan master Rujing is the instructor from whom Kōso Jōyō Daishi (高祖承陽大師, a title of Dōgen) received the dharma legitimacy, hence the springhead for the Sōtō teachings, and Takita revered him so much that he traveled to foreign land by himself to reconstruct the master’s stupa which was once obscured. His filial piety is unprecedented…”

This biography suggests that no substantial evidence of the existence of a previously existing Rujing Stupa at the Jingci Monastery has been confirmed. Takita’s biography also proves that it was the efforts of Japanese pilgrims that leads to the establishment of the master’s stupa in Hangzhou. The motives behind such events, as the biography implies, is that by “reconstructing” this stupa, the pilgrim reifies his reverence to the Rujing, the “springhead” of the Sōtō tradition and the patriarch who granted Dōgen legitimacy. Based on these records, we can safely define the Rujing Stupa at Jingci Monastery. It is not a stupa inside which the relics of the master’s body were preserved, nor is it an item established soon after the master passed away. Instead, it is a modern construction initiated by Japanese Buddhists, more specifically, the Sōtō communities. However, to clarify the facts about the Rujing Stupa at Jingci is not to prove its “fakeness”. The contrast of the attention raised in the two countries, together with the continuing pilgrimages in Japan suggests that the Rujing Stupa is a case of rich significance, from which we could extract various motives of Buddhists in such constructions.

Firstly, it appears that to the pilgrims noted in this section, the existence of the stupa is more important than its authenticity. While the modern Sōtō pilgrims were fully aware that Jingci is not the monastery at which Rujing trained Dōgen, and not the place where Rujing was buried, they still take such a construction of the stupa in another city as an item with great significance. The stupa constructed by Takita became another important destination for Sōtō pilgrimages, the importance of which was no less than the Sōtō “ancestral temple”, the Tiantong Monastery. Such a phenomenon reflects how the stupa was regarded as one of the most important material representations in Buddhist tradition. The tradition of the “stupa cult” in East Asian Buddhism is unignorable. The concept “stupa-temple” (

tasi/tamiao 塔寺/塔廟, the early Chinese translation of the Sanskrit word “

stūpa”) implies that a stupa was considered the most basic element in a Buddhist temple. Archeological studies also suggest that in the early layout of Chinese Buddhist temples, the stupa was usually the center of the whole monastery (See

Li 2014). In the context of Japanese Zen tradition, since a master is viewed as the authority in terms of doctrinal correctness, genealogical legitimacy, and the one who sets the tone of practicing within the tradition, such a patriarch’s stupa is also treated with great reverence. In a sense, the construction of Rujing Stupa at Jingci Monastery could be regarded as one more example of the tradition of the stupa cult in modern times.

Another motive for building the stupa for a patriarch is that it could strengthen the connection between the monk and his successors, which ensures the successors’ place in the lineage. In Japan, the monastery with the stupa of an important patriarch was usually considered the head temple of other monasteries in the sect, and such locations were always carefully maintained. In this sense, a stupa could serve as evidence of a rightful genealogy. When tracing Dōgen’s transmission back to Chinese Chan, a physical sacred site in China that proves the bond seems self-explanatory and therefore a great kind of evidence. In short, the need for a solid stupa is also inspired by the idea of genealogy.

The construction can also be regarded as a political move when situated in a larger context in Japanese Buddhism after the Meiji Restoration. In this period, many Buddhists in Japan sought to “unite all Buddhists” in other nations to strengthen the voice of the religious community against the anti-Buddhist sentiment in Japanese society. The biography of Takita described China as a dangerous place for travel, and Chinese Buddhism as corrupted and in chaos. This is an image shared by the Japanese Buddhists of that time, transmitted by monks who traveled to China to “seek for possible unions among Chinese Buddhists”, but turned out disappointed when visiting local monasteries. Therefore, some Japanese monks initiated a movement of spreading Japanese Buddhism as a resort to revive the Chinese counterpart from its corruption. Mizuno Baigyō mentioned earlier is a monk who expressed this goal in his writings, and another figure in this movement is Ogurisu Kōchō 小栗栖香頂 (1831–1905) (See

Chen 2016). While from different affiliations of Japanese Buddhism, these figures share the same idea that Japanese Buddhism preserves the genuine form of Buddhism that came earlier, instead of present China.

Takita’s determination to reaffirm the Sōtō’s connection with Song Chinese Buddhism, together with his critical attitude toward current Chinese Buddhism reflect a complex view on China in his time. On one hand, the past connection between two traditions is valued; on the other, the superiority of one side over another is promoted. The national discourse prevails in the biography. By promoting Japanese Buddhism, and spreading it to other “Buddhist” countries, the Japanese Buddhist communities sought to prove their significance to the state. In fact, many pilgrims noted in this section are actively engaged in politics—Kuruma Takudō was an activist campaigning for priests’ rights, and later served at the Japanese House of Councilors; Mizuno Baigyō befriended Chinese monks as well as politicians and established Sōtō-teaching institutions in China to avoid monasteries being occupied for other purposes (See

Takagai 1970). All these activities, including their pilgrimages, can be viewed as both a resort to promote the role of Buddhism domestically, and a resort to prove the influence of Buddhism internationally. In both ways, Japanese Buddhists argued against the anti-Buddhist wave of their time.

In this section, by tracing the records written by Japanese pilgrims, I explained the history of the Rujing Stupa in the late 19th to early 20th century. We know that the Rujing stupa constructed at the Jingci Monastery between 1879 and 1880 was a monumental site built by Japanese Buddhists. It was not built on any substantial remains of earlier architecture, but constructed as a memorial for a figure that is significant specifically for the Sōtō community. Such a construction is an action that involves multiple motives and forces. While contrary to what the stele inscription states, it is not a site where the master was buried, the history of the stupa makes it an even better example in the understanding the formation of sacred sites and pilgrimages.

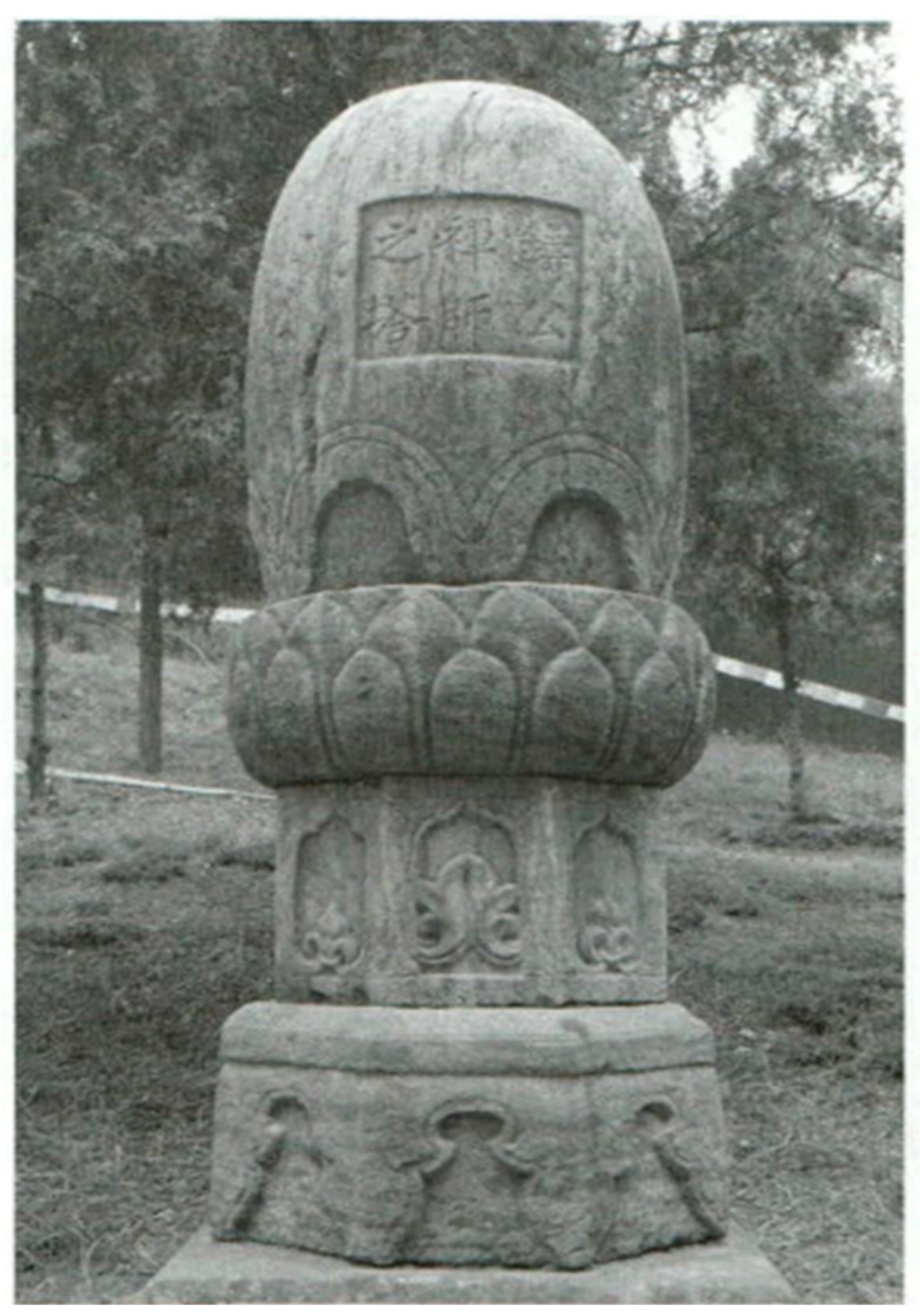

4. The Reconstruction of the Rujing Stupa in 1983

Despite the clarification of the origin of the Rujing Stupa in Hangzhou, the events about this site are yet to end. As noted in Takita’s biography, what had been established at the Jingci Monastery was a “seamless stupa”, a special architectural style of stupa presentation that the main part of the stupa is egg-shaped (

Figure 1), a form with no edges and no seams, implying the ideal of a Chan monk’s perfection in practice (See

Zhang 2016). However, the extant stupa at the Jingci Monastery is by no means in a “seamless” style. As shown in the following photos, the Rujing Stupa present today was built in hexahedron style (

Figure 2).

The contradictions between the records in Takita’s biography and the actual stupa suggest further changes on this site. This section therefore elaborates on another “layer” of the construction of the Rujing Stupa in the past decades and summarizes the history of this site as a whole.

The Jingci Monastery underwent an unpeaceful century after Takita’s first construction of the stupa. It suffered damages through city fires, a problem that long troubled many architectures in Hangzhou.

5 During World War II, when the city fell, this site was occupied by Japanese soldiers and its properties were looted and priests executed.

6 In the later Cultural Revolution, this place was once repurposed for non-religious activities. While no records suggest a direct cause for the missing of the stupa Takita constructed, it is safe to state that all the conditions mentioned above makes the object unlikely to persevere.

When recovered as a Buddhist location after the Cultural Revolution, the existence of the Rujing Stupa together with Takita’s adventures is lost in not only Chinese but also Japanese memory. In 1980, Hata Egyo 秦慧玉 (1896–1985), the 76th abbot of Eiheiji came to the Tiantong Monastery to attend the founding ceremony of the Stele of Chan Master Dōgen Obtaining the Dharma Transmission (道元禅师得法灵迹碑). The ceremony was held by the Buddhist Association of China, and the inscription was written by Zhao Puchu 趙樸初 (1907–2000), the chair of the association. In 1990, the 77th abbot of Eiheiji, Niwa Rempō 丹羽廉芳 (1905–1993) donated another two steles to Tiantong in order to memorize the monks “who made a contribution to the friendly communication between Chinese and Japanese Buddhism” (

Guangxiu 1997, p. 279). While these two events reflect the recovered pilgrimages of the Sōtō Buddhists as a continuum of Takita’s a century ago, the two abbots did not manage to locate the master’s relics in the first place. In the 1990 Stele inscription titled “the Grace of the Past Sage Rujing 先覺如净禪師崇恩碑” at the Tiantong Monastery, Niwa Rempō noted the effort in finding this sacred site in his generation:

“People said that in the Southern valley of the Tiantong Mountain there was the stupa of Patriarch Jing, and the Japanese dharma offsprings went there several times. Surprisingly, they found the Rujing stupa at Jingci Monastery in Hangzhou, and reconstructed it in 1983”.

It appears that the Sōtō pilgrims in the late 20th century who initially searched for the stupa in Ningbo took the remains of the Rujing Stupa in Hangzhou as an unexpected discovery, unaware of the fact that the stupa there was constructed by their predecessor Takita Yūchi. The need for reconstruction is most likely because of the damage to this site during the unrest times. Moreover, without the notion that the first construction was in egg-shaped “seamless” style, they established a pagoda-like presentation, as shown in

Figure 1. In short, the Rujing Stupa at Jingci Monastery was initially a constructed memory, yet the memory went obscure during an eventful time period for the pilgrims. Despite this, the commitment to locating the sacred site and readdressing its significance persists. When the later pilgrims found the relics left by their predecessor, they took the newly constructed site as an original one and recovered the pilgrimage there. From this moment, the identity of this hexahedron, pagoda-style architectures has been described as a recovered ancient site with direct connection with Rujing’s relics.

In this period, the connection between Rujing and the Sōtō tradition was no longer only a religious issue. For the two states involved, Rujing became a historical figure with diplomatic values. Hata and Niwa’s visits and donations to the Tiantong Monastery were reported in Chinese journals as signals of the normalization of China-Japan diplomatic relationship after 1972. Chinese monks who either once instructed Japanese disciples or went to Japan and Japanese monks who were instructed by a Chinese master were all categorized as figures who “contributed to the friendly communication” between the two countries in history, as seen in the

Nitchū Bukkyō yūkō nisennenshi 日中仏教友好二千年史, a book that collects of all these figures, composed in 1987 and circulated in both Japanese and Chinese languages.

7 In comparison to the pilgrims one century ago, the Japanese Buddhist communities suggest a continuing connection between the two countries rather than criticizing a corrupted tradition as contrary to them as the “genuine preserver”.

Along with this narrative, memorial constructions such as steles, halls, stupas, and so forth flourished among Chinese monasteries where significant Japanese Buddhist figures once been to. The Rujing Stupa is not a unique case in this sense. “The Stele of Master Saichō Obtaining the Dharma at Mt. Tiantai (最澄大師天台得法灵迹碑)” was erected at the Guoqinng Monastery 國清寺 in 1982. In 1984, a hall was constructed at the Qinglong Monastery 青龍寺 in Xi’an, named “Memorial Hall for Huiguo and Kūkai (惠果空海紀念堂)”. All these constructions were supported by Japanese Buddhist communities, with the assistance of the Buddhist Association of China leading by Zhao Puchu, who at the same time, was one of the vice chairpersons of the National Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) from 1983–1998. The active role of Zhao reflects that connection between Japanese Buddhist patriarchs and their Chinese masters, in this time, are greatly valued by the two countries as evidence of “a long-lasting friendly, peaceful communication”.

As a result, a political layer had been added to the studies of Buddhist figures with transnational influences. The narratives of “friendly Sino-Japan communications” had influenced the Chinese modern narrative of this place. This explains why the 2011 inscription near the Rujing Stupa spends words introducing Dōgen. Also, under the influence of the Sōtō pilgrims descriptions of this site, it is suggested that the Rujing Stupa had been an original part of the monastery since the 13th century.

To summarize, records from pre-modern, early modern, and recent materials reflect multiple layers of the history of the Rujing Stupa at Jingci Monastery; the image of Rujing for Chinese Buddhists was obscured soon after his death. On the other hand, the Sōtō Buddhist communities constructed a sacred site overseas for him as a resort to strengthen their connection with a patriarch and to further legitimize their own tradition. The narrative of the sacred site was rewritten within decades. The first construction by Takita was described as a heroic move, a religious activity dedicated to tracing Japanese Sōtō tradition to an origin in 13th-century China. The recent construction and related records, however, replaced the tone of the exulting courage of a pilgrim for the risk he took in traveling to a dangerous region, with the appreciation of figures that symbolize benign interactions between two states. The changes in narratives show us that the rise, fall, and revival of a site should be interpreted under a scope that includes but is never limited to religious motives and that in different time periods, the factors in effect could shift from one to another. From the relic of a 13th-century Chan master to a “symbol that reflects national friendship”, the narrative of the Rujing Stupa witnessed and reflected the evolving interactions within and beyond the religious dimension of East Asia.

5. Concluding Remarks

In this paper, I have compared sources in Chinese and Japanese and clarified that as opposite to the description on the stele near the site, the Rujing Stupa is a modern construction by and for Japanese pilgrims, a symbolic object that aims at reifying the origin of the Sōtō tradition. It does not mean that the present site is meaningless if proven to be an architecture established in the 1980s instead of a relic from the 13th century. By tracing the associated records of the modern constructions, such case studies reflect the dynamics in the establishment of a transnational sacred site, the changes in related narratives, and the motives behind the changes. Along with this, more analyses could be conducted if further records on the participants in the constructions are excavated.

A close inspection of a sacred site from broad source materials is not only a fruitful approach to understanding the formation of pilgrimages, but also a necessary action in order to examine if the narratives of certain communities are historically accurate. Though the physical existence of these sites would not be denied through the critical review of the textual records, the examination of their narratives leads to understanding of richer dimensions of their significance. The importance of a sacred site is reflected in the ongoing pilgrimages, meanwhile, for religious studies, what is no less important is a clarification of the events and motives that led to its existence and shaped the story being told.

This case study also offers insights in regard to the method of investigating a sacred site. While stele inscription in the Chinese context is a valued source, this study suggests that what had been carved on stones is also subject to biased narratives. Since intentions from various sources would affect the output of such on-site textual records, a wider range of sources needs to be taken into examination for a more comprehensive point of view. Tracing and reexamining the reference that impacts the on-site information is therefore a necessity for future studies on this subject matter. Lastly, as intentions and motives in the formation of sacred sites are crucial, the question of “to whom this site is relevant” must be carefully answered before explaining the significance of these relics. In this sense, the case of the Rujing Stupa reflects the complexity of the formation of a location for transnational pilgrimages and promotes an approach of a comprehensive analysis of primary sources in explaining such religious phenomena.