Abstract

Among the contemporary thinkers who try to think of economics not just as having a non-empty intersection with religion but as being intrinsically religious, Giorgio Agamben occupies a singular place. Indeed, one of the main theses of his major work, Homo Sacer, is that the modern rupture between “sovereignty” and “government”—which lies at the heart of his political diagnosis of our contemporary situation—can be traced back to classical Trinitarian theology. Since this rupture is allegedly responsible for today’s Western understanding of economics, this implies that, according to the Italian philosopher, our current crisis has Christian theological roots. In this paper, I first discuss the argument put forward by Agamben to assert that, at least since the Trinitarian controversies of the second century, Christianity has become intrinsically oikonomia, that is, it understands history as the unfolding of a providential dynamic which, he claims, anticipates today’s celebrated “invisible hand” of decentralized markets. Next, I offer critical reflections upon this argument by questioning whether contemporary mainstream economics can be reduced to the “market fundamentalism” with which it is often confused. The article concludes by questioning, in turn, whether all Christian traditions boil down to the historical trend that Agamben characterizes as leading to today’s problematic mainstream economics.

1. Introduction

When discussing the relationship between economics and religion, one immediately encounters the strong assertion, made by a few contemporary scholars in economic theory, that economics is a positive science and is free of any prejudice, let alone moral or religious assumption (Shachar and Zame 2008)1. This standpoint might be viewed as the expression of some epistemological naïveté and has indeed been challenged (cf. e.g., Atkinson (2009) among many others). In Giraud (2021), in particular, I provided a formal argument suggesting that consumption choices can be viewed as the consequences of moral axioms regarding the distribution of status and resources in a given economy. This discussion, however, remains framed in a context where it is taken for granted that economics and religion have their own, autonomous spheres of intelligibility—and that these spheres may possibly have a non-empty intersection, whose extension and meaning remains to be assessed. This is also more or less the main presupposition of this special issue, as I understand it.

There is, however, at least one important contemporary writer whose take goes much further than the frame just alluded to: the Venetian philosopher, Giorgio Agamben. Indeed, his opus magnum, Homo Sacer (in particular, Agamben (1998, 2011)), claims to provide the Christian theological anticipation of the current understanding of mainstream economics as a domain where the pursuit of individual interest spontaneously leads to the common good. Conversely, Homo Sacer offers an interpretation of Christianity as being intrinsically οἰκονομία (oikonomia) (more on this later). The main argument is that the modern rupture between “sovereignty” and “government”—which lies at the heart of his political diagnosis of our contemporary situation—can be traced back to classical Trinitarian theology. Since this rupture is allegedly responsible for today’s Western understanding of economics, this implies that, according to the Italian philosopher, our current crisis has Christian theological roots. Following this line of thought, therefore, leads to the conclusion that there is no such thing as a frontier or a common boundary between economy and Christian theology; insofar as we accept Agamben’s take, economics is (similar to) Christian theology and vice versa.

Agamben’s contribution is viewed by many as decisive both in the philosophy of contemporaneous art and in political philosophy. To the point that some scholars consider him as a “major political philosopher of our time” (Segré 2017) and his work belongs to the recommended readings of a large number of academic curricula in anthropology, political philosophy and aesthetics—especially in the US. Curiously, on the other hand, with a few exceptions, Agamben has not receive much attention from theologians and is largely ignored in economics. This is all the more surprising since Homo Sacer exhibits quite an erudite and fine knowledge of the patristic tradition. Given the very small number of non-theologians who are familiar with the writings of the Greek and Latin Fathers of the Church, Agamben’s erudition alone should have aroused curiosity. One of the purposes of this article is to start filling this gap by discussing Agamben’s main claim that economics is Christian theology and vice versa.

His publications can be viewed as part of the literature initiated some twenty years ago in the English language, and whose main contributors include Nelson (2001), Goodchild (2003) and Taylor (2007). All of them argue that the idea—usually attributed to Mandeville and Smith2—according to which the encounter of aggregate supply and demand on a “free market” should lead to an allocation of resources that satisfies some criterion comparable to the Common Good, owes some debt to Christian traditions. However, they all offer perspectives on the issue that sharply contrast with Agamben’s standpoint. Nelson pictures current professional economists as “priests” of the “modern religion”, namely “economic progress”:

“The most vital religion of the modern age has been economic progress. If economists have had a modest impact in actually generating this progress, or even understanding the actual mechanisms by which it has occurred, they have had a large role in giving it social legitimacy. They have been the modern priesthood of the religion of progress, interpreting its forms, refining its messages, and assuring the faithful that progress would continue. Without the blessings of an authoritative priesthood, all kinds of opportunistic and predatory forces are always lurking in wait in society, holding the potential to undermine the workings of the market as well as other core institutions. By promoting a culture of civic commitment to the market system, economists have put the power of religion to work in fending off these newer temptations of a modern kind of ‘devil’.”(Nelson 2001, p. 329)

To the best of my knowledge, however, nowhere does Nelson claim that Jewish and Christian traditions were intrinsically inclined to anticipate mainstream economics3. By contrast, according to Goodchild’s (2003) critique of capitalism in view of the looming ecological disaster, modern European citizens never ceased to be religious (pious) despite their rejection of the Ancien-Régime’s religious heteronomy:

“Modern reason was founded on a critique of piety: for it was through complicity in shared beliefs that people were subjected to hierarchical domination by powers and authorities. Denouncing the pieties of tradition, daring to speak of what is different or new, modern reason does not turn attention to its own determinate practices of directing attention. It disavows its own piety, and this very disavowal constitutes its piety.”(Goodchild 2003, p. 242)

There is an alleged implicit religious structure underpinning both pre-modern Christianity and contemporary capitalism but, again, Goodchild does not dig into Christian traditions with the aim of showing that they might have morphed into today’s cult of the marketplace. Finally, with Taylor (2007), a central piece of Christian history—Reform—is attributed a major role in the secularization (Entzauberung) process that would lead to modernity and to today’s economics:

The main difference between what Taylor calls his “Reform Master Narrative” (RMN) and Agamben’s narrative is that, as we shall see, the latter goes back much further in the Christian traditions to identify the origin of what he sees as today’s predicament, namely the theological quarrels of the second century. Consequently, it is not just Reform that is viewed as a breeding ground to modern economics but Christianity as such.“Briefly summed up, Reform demanded that everyone be a real, 100 percent Christian. Reform not only disenchants, but disciplines and re-orders life and society. Along with civility, this makes for a notion of moral order which gives a new sense to Christianity, and the demands of the faith. This collapses the distance of faith from Christendom. It induces an anthropocentric shift, and hence a break-out from the monopoly of Christian faith.”(Taylor 2007, p. 774)

The rest of this paper discusses Agamben’s own “Master narrative”. Section 2 briefly recalls how Agamben (1998) understands “bare life” as being the main constituent of a sovereignty that is devoid of any transcendent foundation. Section 3 explains how, within such an understanding of sovereignty, Agamben credits the Trinitarian theology of the second century Church Fathers with inventing the paradoxical ontology upon which the mascarade of our modern democracies operates, leading to the absolutization of the “invisible hand” as a universal “providential machine”. The last two sections question Agamben’s main thesis from two different viewpoints. Section 4 recalls that contemporary mainstream economics has long since mourned the invisible hand insofar as it has recognized since the 1980s the profound inefficiency of “markets”. The last section challenges Agamben’s rendition of the role played by Christianity by arguing that his narrative may do justice only to one trend of Christian traditions—not the entirety of them.

Before plunging into the matter, a caveat is in order: there is no point in claiming to be able to capture the depth and finesse of the entire trilogy of Homo Sacer within a few pages. The following is therefore, by necessity, a cavalier introduction to some of the themes addressed in this monumental work. Being myself trained in mainstream economics and Catholic theology, I can hardly claim to be an expert on Agamben’s thought, never mind of his numerous sources. I hope, however, that the transversal approach taken in the following may feed the discussion around one key aspect of the relationship between economics and theology.

2. Agamben and Bare Life

Already the subtitle of his magnum opus, Homo Sacer—Sovereign Power and Bare Life, indicates that Agamben’s (1998) intention is to revisit the question of the relationship between life and power, albeit from a very different perspective than the Foucauldian one from which he takes inspiration.4 This revival leads him to take Christianity to court in a way that is foreign to Foucault’s work. His ambition is to retrace the genealogy of power as Westerners have experienced it for at least two millennia. The latter is essentially characterized by what Agamben dubs “spectacular power” (e.g., Agamben 1998, p. 256) and which, according to him, lies at the heart of “government by consent” or “consensus democracy” (ibid.). These concepts tie together the contemporary omnipotence of the economic instance, the omnipresent media spectacle5 and the necessity, in our contemporary democratic regimes, of appealing to the consensus of opinion—or to what takes the place of it (polls, plebiscites, referenda, etc.)—to ensure the legitimacy of a state power that, in Agamben’s eyes, less and less effectively conceals the fact that it is intrinsically arbitrary.

According to Agamben, the original structure of sovereign power implies a specific relation to life, known as the relation of “exception”. Sovereignty does not relate to subjects equipped with rights, but to a “bare life”, which it it produces at the frontier of law. The life of each and every one of us would thus be exposed to killing violence of sovereign power, insofar as I could at any moment be relegated to the sphere of a life absolutely deprived of all rights, the “bare life”. At first glance, it may seem as if we’re returning to a “classical” conception of sovereignty, the very one Foucault sought to free himself from, but this is only partly true. Agamben’s project consists in the restoration of a Schmittian understanding to sovereignty within a diagnosis that extends to the whole of the Western history of sovereignty. Each of our lives is subject to an arbitrary decision that determines its status: some are entitled to certain rights, others are not, and the distribution of these rights is arbitrary in the sense that it cannot be justified by natural law or the essence of sovereignty. In other words, the essence of sovereignty is precisely its arbitrariness. Taken within this logic of “exception”, “life” (vita) would feed the functioning of sovereign power, which would institute and maintain itself by producing the “biopolitical body” over which it is exercised. As Genel (2004) has clearly seen, whereas Foucault based his analyses on a philosophical theme that echoes, of course, the Heideggerian understanding of Dasein as “an animal in whose politics his life as a living being is in question”, Agamben intends to reverse the formula: “We are, he writes, citizens in whose natural bodies our very political being is at stake.”6 In other words, Homo Sacer is not content with thinking about specific, historically-determined techniques of power, as Foucault did, but the very essence of sovereignty from its very origins, proposing to decipher it as an intrinsic relationship to our “natural bodies”.

In Agamben’s eyes, entry into the political sphere takes place through an exclusion of mere “natural” life, or ζωή, which remains circumscribed to the domestic sphere of the home (οἶκος). The destination of mankind, and in particular of the community in Aristotle, is not the mere fact of living but the politically qualified life, the βίος.7 According to Agamben, the ζωή—which becomes the stake of the specific political techniques that Foucault called bio-power—is in fact at the foundation of the political sphere from its very origin under the species of vita nuda (“bare life”) and according to the particular modality of exception. It is therefore because life is originally at the foundation of the political sphere that bio-political techniques, in the Foucauldian sense, have been able to bear on it for two centuries. The ζωή is excluded from the political sphere, which is constituted by this very eviction or by its transformation into βίος, according to an arbitrary partition of people. Such an operation of “politicizing” life—which founds the political sphere—is viewed as being equivalent to the constitution of a bare life, i.e., a life maintained under the power of sovereign power by the very gesture that excludes it from the city. The practice of “banning” would express this power: vita nuda is that which is banished in the double sense of that which is excluded from the community, banished, but which is in this way placed under the sign of the sovereign, under his banner.

Agamben concludes that bare life is not a given, and certainly not “natural” in the traditional meaning of opposition between nature and culture. It is but the “original provision” of sovereign power:

What is at stake is a definition of the sacred borrowed from homo sacer, an astonishing figure of archaic Roman law who could be killed without committing homicide, but who could not be sacrificed in ritual form: a life devoted with impunity to an arbitrary death. Such figures of the “bare life” haunt our history: the Roman homo sacer, but also the Greek exile, the mis-au-ban (ban-dit) of the Middle Ages, of which the werewolf would be a legendary remnant (ibid., pp. 86, 140), as well as the political refugee of the 20th century, the Auschwitz deportee, the Guantánamo Bay detainee, etc. Agamben is then led to a hyperbolic denunciation of all sovereignty, on the grounds that it can only draw “force of law” from an exclusion from life, possibly skillfully concealed but betrayed by all those victims of the arbitrariness of a state of exception who populate our history.“Life in the sovereign ban is sacred from the outset, that is, exposed to murder and insacrifiable. The production of naked life becomes, in this sense, the original benefit of sovereignty. The sanctity of life, which we are trying to assert today as a fundamental human right against sovereign power, expresses, on the contrary, the original subjection of life to a power of death, its irremediable exposure in the relation of abandonment”(Agamben 1998, p. 93)

3. Trinity and Ontological Dualism

In the eyes of the Venetian philosopher, the state of exception constitutes an empty space of law essential to the juridical order, through which the latter assures itself of a kind of performativity of law prior to the law itself. The proposed philosophical trajectory is thus oriented towards thinking of the political as the production of a void, qualified by the exception of bare life, destined to be the foundation of all sovereignty. The purpose of Agamben (2011), which interests us here, is then to locate this “void”, as it were, between a “macchina governamentale” (governmental machine) on the one hand, conceived on an economic-managerial model, and the “gloria” (glory) with which political power surrounds itself to perpetuate the religious trust placed in it by its subjects. This thesis constitutes, in my view, the central core of Agamben’s theological take on the relationship between theology and economy. It says that the δόξα with which the Western state surrounds itself is a vain attempt to find a transcendent foundation for its authority—to give “force of law” to the law it enacts—whose emergence owes debts to the lineaments of a Christian genealogy.8

It is not possible, within the limits of the present article, to discuss in detail Agamben’s long and erudite demonstration, which goes back to the Pauline writings and then navigates notably between the works of Clement of Alexandria, Irenaeus, Tertullian and the Cappadocians in order to suggest, finally, that the Christian patristic tradition bears the essential responsibility for a dichotomy between regnum (reign) and gubernatio (governance) that would be at the origin of our contemporary crises. Let us therefore try to focus on the essentials.

The rise of the “economic paradigm” that now, according to Agamben, pervades almost the entire social sphere of Western societies has its distant origins in a confusion between the city and the home, a misunderstanding propagated by early Christian literature. On the one hand, the πόλις, the properly political space, on the other, the οἶκός, the home, the den, and, ultimately, the terrain of the οἰκονομία. The distinction between these two registers, though established by Aristotle, would indeed have disappeared from Late Antiquity through several stages that the book patiently traces. Trinitarian dogma bears most of the responsibility for such an “oversight”, which seems to play a role analogous to the Heideggerian oblivion of being that is characteristic of Western ontotheology. Christian Trinitarian monotheism would in fact determine the development of a political model, the formula of which, over a millennium later, could be summed up as: “Deus regnat sed non gubernat” (God reigns but does not rule).9 Divine power can only be exercised by delegation, without being divided. To achieve this, Christianity is said to have split the Platonic being in two: on the one hand, being as presence which finds in the one God the transcendence of sovereign power and, on the other, being as action “which substitutes for this the idea of οἰκονομία understood as an immanent, domestic order of human life.

This split can be interpreted, from within the continental European philosophical tradition, as corresponding, for the first type, to the metaphysics of the determination of being as presence, as thematized and criticized by Martin Heidegger and Jacques Derrida as being the hallmark of Western ontotheology; the second type of ontology corresponds, for its part, to the identification of being and action (or will) found, e.g., in Friedrich Nietzsche10 or Arthur Schopenhauer. In Agamben’s view, this dichotomy corresponds to the duality that opposes classical political philosophy, centered around the transcendent concept of sovereignty, and political economy as the immanent, domestic government of society, of which Foucauldian biopolitics is the explicit analysis. The reduction, or rather the absorption, of the first by the second—hence, the disappearance of the Aristotelian distinction between city and home—would be one consequence of the precedence that would then soon be given to action, that is, to immanent and domestic government, over a transcendent being which does not rule and becomes “useless”.

According to the Venetian philosopher, the theological origin of this duality can be traced back to the Trinitarian debates of Tertullian and the tendency of the second-century Church Fathers to think of a God who is both one and triune.11 To resolve the paradox, unity would be placed on the side of being as presence, the Trinitarian character on the side of “economic” action in salvation history. But what would then have made it possible to safeguard the theological articulation between unity and triplicity would have been conquered at the cost of another split in the ontological order, the eminently problematic character of which would have escaped the vigilance of early Church Fathers, but which was to prove decisive for what followed: the distinction between being and action. Moingt’s translation of Tertullian’s unicus deus cum sua oikonomia: “God with his government”, in the sense that “government” designates the king’s ministers, whose power is an emanation of royal power and is not comparable to it, but necessary to its exercise, so that “Economy signifies the mode` of administration by many of divine power” (Moingt 1966, p. 923, the translation is my own).

Following Agamben, this dichotomy would enable Christian theology to construct its “dominant governmental paradigm” by attributing presence to the kingdom and action to government. This dual political ontology would have been made acceptable thanks to the concept of “hierarchy” introduced by Pseudo-Denys the Areopagite (1958). This would have enabled Areopagytus to sacralize ecclesiastical administration and, above all, to give a structure to the Christian governing machine capable of surviving the disarticulation of reign and government; even when it has become useless, reign would then be able to maintain itself by giving itself a new form: the glory (δόξα). Agamben can then formulate the thesis that guides the last three chapters of Agamben (2011): glory, which goes hand in hand with all hierocracy, is intended to conceal the fundamental arbitrariness of sovereignty, that is, the idleness of the reign, whilst all political activity is henceforth surrendered to governmental management alone. It is this reduction of politics to management by government that Christianity would have made possible by promoting the concept of οἰκονομία.

Agamben bases his proposal on the ceremonial history of power and law by Peterson (1935) and Schmitt (1970). As we know, Roman acclamations had a legal dimension of assent by the people. The right of triumph granted to the emperor was the legal core that informed the entire Roman law of imperial sovereignty. It is cult, ecclesiastical liturgy and profane protocol which lies at the core of contemporary democracies: “Contemporary democracy is a democracy integrally founded on glory, that is, the effectiveness of acclamation multiplied and disseminated by the media beyond all imagination” (Agamben 2011, pp. 279–80). Such a function still exists in contemporary democracies, where acclamatio would take the form of public opinion. While the government, embodied by the ecclesial hierarchy, manages the economy as an extension of the Son’s action, its power takes on the aspect of an inactive reign, attributed to the authority of the Father, who “produces” or delivers nothing but emptiness. The glory is but the splendor emanating from this emptiness, which both veils and reveals the central “vacuità della macchina governamentale” (emptiness of the governmental machine). A “providential machine” would then emerge from the disjunction of being and praxis. On the side of the Father, being does not act in the world; action, on the side of the Son and his Spirit, legitimized by the Father’s sovranità (sovereignty), governs the world like a machine carrying out the Father’s orders.

In other words, Christian Trinity would thus have anticipated the “macchina provvidenziale” (providential machine) that separates and articulates powers: those of

- –

- the Father (Deus otiosus), who reigns but whose being is summed up in a useless presence concealed by the fires of glory,

- –

- of the Son, to whom “economic” action falls,

- –

- and of the Holy Spirit, whose task it is to bring about the glory of the Father, so that the whole dogmatic artifice becomes credible.

The Son (Deus actuosus), insofar as he is distinct from the Father, would be his earthly “sword arm”, fulfilling through his incarnation the teleological, governmental, immanent, managerial and, ultimately, administrative program of the world. Finally, the Holy Spirit would unite the first two persons of the Trinity through doxology. In short, contemporary market democracies are artificial lies where the democratic will only serves as an acclamatio of the void glory of the State, whereas the bureaucratic administration does to job of secretly managing our society. In Agamben’s eyes, we owe this predicament to second-century Christian Trinitarian monotheism. It is, in fact, the multiple semantic shifts internal to the patristics around the concept of οἰκονομία that have enabled the contemporary economy to acquire the almost integral domination that is its own. Faced with a Father who was present but transcendent and idle, it was necessary to give a divine meaning to the immanent exercise of government, of action; this was the role played by the οἰκονομία of the Fathers.

According to Agamben, the science of publicity is but the contemporary avatar of “Glory”, i.e., the democratic assent obtained through an opinion-forming mass. Finally, the Father “who reigns, but does not govern” already prefigures Adam Smith’s “invisible hand”, according to a providential disposition that owes its essence to the patristics (Agamben 2011, pp. 122, 227, 283–85).

Christianity would thus have been compelled by its Trinitarian logic to think of history in terms of a “mysterious economy”. Indeed, in proclaiming the reign of God at work in the history that separates us from the Parousia, Christians had to constitute a historical paradigm different from pagan fatum, as well as from Stoic necessity. The οἰκονομία thus left an a priori less narrow margin for free human practice. But the articulation of this relative freedom with the regnum of the Father now constituted in itself a theological–political mystery, inducing an insurmountable division between the transcendence of power—being as mere presence—and an immanent economic teleology—being as action. The combination of faith in the “invisible hand” of the marketplace managed by bureaucratic administrations (be they private or public) and “media glory” would be the contemporary problematic answer given to this aporia.

Of course, there is something exorbitant about this fresco, which brings together historical realities spanning more than a millennium. Agamben himself is cautious: in his methodological essay, The Signature of All Things, he insists that his genealogy of our modern situation does not claim to identify a causal origin in the Church Fathers’ Trinitarian theology. Trinitarian economy is rather a “paradigm”, “whose aim was to make intelligible series of phenomena whose kinship had eluded or could elude the historian’s gaze.” (Agamben 2008, p. 31) What is, then, the status of this “kinship”? “When you press on this claim”, comments Charles M. Stang (2020); however, the book does not offer a very precise or satisfying account of either intelligibility or kinship, leaving the impression that the “paradigm” of Trinitarian oikonomia operates on the level of a grand analogy. The modern political structure of kingdom divorced from government, with only glory serving as the glue, is somehow like Trinitarian oikonomia. But the “somehow” remains frustratingly opaque. It is this “grand analogy”, however imprecise it might be, that I will discuss in what follows.

4. Mainstream Economics and the Invisible Hand

In the next two sections, I would like to question certain aspects of this impressive grand narrative which encompasses not only Reform and Weber (as with Taylor (2007)) but also Christian patristic tradition and Scottish Enlightenment. For the sake of brevity, I will focus only on two features. The first one deals with the implicit assumption that the whole economy today boils down to market fundamentalism based on the invisible hand. If this is not true, as I will show (even if we restrict ourselves to mainstream economics), this means that the predicament induced by the Christian genealogy identified by Agamben concerns only one sector of the economy: the one which remains faithful to the myth of the invisible hand, despite its refutation by mainstream economics. That a portion of commentators still adheres to the legend of market efficiency is an interesting paradox that I shall not try to explain here, nor does Agamben. It implies that Agamben’s critique is not entirely wrong: segments of our societies do live on the premises of this urban legend. But my point is to stress that it addresses only one aspect of today’s economy, namely a certain market fundamentalism which lacks any scientific background. The next section will aim at performing the same kind of critique but, this time, within the theological domain of Christian traditions.

As Jonathan Shefler puts it: “One of the best-kept secrets in economics is that there is no case for the invisible hand. After more than a century trying to prove the opposite, economic theorists investigating the matter finally concluded in the 1970s that there is no reason to believe markets are led, as if by an invisible hand, to an optimal equilibrium—or any equilibrium at all. But the message never got through to their supposedly practical colleagues who so eagerly push advice about almost anything. Most never even heard what the theorists said, or else resolutely ignored it.” (Shefler 2012)

As surprising as this statement might seem, it is correct. General Equilibrium Theory (GET) can be considered as the core of standard economic theory. It underpins virtually all areas of mainstream economics and finance as we have understood and taught them since the Second World War. Beyond the possible aridity of its mathematical results, at the heart of this theory lies the highly controversial debate surrounding the invisible hand of the market. As I will now show in what follows, GET teaches us that decentralized markets are deeply inefficient and may not even lead to any balance between supply and demand. Before going into this, let us briefly remember what exactly can be credited to Smith. Again, following Shefler (2012):

“Adam Smith suggested the invisible hand in an otherwise obscure passage in his Inquiry Into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776). He mentioned it only once in the book, while he repeatedly noted situations where “natural liberty” does not work. Let banks charge much more than 5% interest, and they will lend to “prodigals and projectors,” precipitating bubbles and crashes. Let “people of the same trade” meet, and their conversation turns to “some contrivance to raise prices.” Let market competition continue to drive the division of labor, and it produces workers as “stupid and ignorant as it is possible for a human creature to become.”

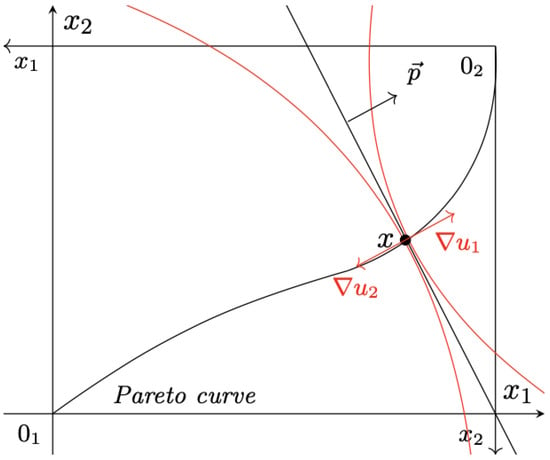

It may, therefore, not really come as a surprise if GET actually amply confirms this statement. In 1954, Arrow and Debreu (1954) provided what has been since then considered as the canonical model of mainstream economics. The contention of the authors is that, under certain assumptions, this model predicts that every decentralized market economy should exhibit equilibrium prices that will simultaneously clear all markets and lead to an “optimal” allocation of resources. This is exemplified in Figure 1, which is well-known to all students who have participated in at least one semester of micro-economic theory:

Figure 1.

The Edgworth box, the Pareto curve and a Walrasian equilibrium.

Here, one considers a hypothetical economy populated by two consumers who trade two commodities. Each point in the rectangle (the so-called Edgeworth box) epitomizes a distribution of each good to households whose preferences are captured by the (red) indifference curves. The “Pareto curve” refers to the set of allocations which are “optimal” in the sense of Vilfredo Pareto, i.e., such that it is not possible to reallocate the two goods in such a way that both agents are weakly better off and none of them is worse off. In the setting of consumer preferences that can be represented by differentiable utility functions, this amounts to requiring that the gradient of each player’s utility be collinear to the price vector, p. The x point represents one allocation of goods which is such that every consumer would agree with it given the prevailing price vector, p, and their initial allocation—it is usually called a “Walrasian equilibrium” in tribute to Léon Walras, who is perhaps the first engineer who tried to prove that such an equilibrium exists. The “miracle” of the “invisible hand” is that this x point lies precisely on the Pareto curve. In other words, it is Pareto-optimal. The quest of individual interest leads therefore to a mutually beneficial agreement (often identified with the Common Good).

That every Walrasian equilibrium is Pareto-optimal is the modern transcription of the legendary interpretation of Smith’s “invisible hand”. Since the 1980’s, however, it is has been clearly demonstrated, within GET, that, in reality, Walrasian equilibria are almost never Pareto-optimal; when they are, it is only by accident. A first demonstration of this has been given by Geanakoplos and Polemarchakis (1986): as soon as markets are incomplete, Walrasian equilibria almost always fail to be optimal.12 What does the “incompleteness” of markets mean? It implies that there is at least one type of risk and one market participant who has no way to insure herself against that risk. By contrast, complete markets would be such that, for every type of conceivable risk (climate warming, populist victory in the next US elections, etc.) there are financial hedging instruments available to all that enable each of us to protect ourselves against the consequences of that risk. Obviously, markets are always incomplete. Consequently, GET had already proven in the 1980’s that the “invisible hand” is invisible because it does not exist.

Needless to say, this was not the end of the discussion. One might indeed acknowledge that markets are incomplete but argue that financial innovation helps reduce that incompleteness. Banks create new financial hedging instruments every day: weather derivatives are a simple illustration of this as these assets, which were introduced in the 1990s’, enable their owner to protect themselves from losses possibly induced by weather catastrophes. Credit derivatives are another famous example of such financial innovation. Does this mean that, though it is currently out of reach, Pareto-optimality of Walrasian equilibria should be considered as, say, the teleological horizon of our market economies? The answer provided by GET is quite clear, and it is negative, as has been proven by Elul (1995); unless it is the ultimate financial asset which suffices in completing markets, the additional asset may worsen the Pareto-efficiency of markets! There is no guarantee of “historical progress” in terms of market Pareto-efficiency, and the example of subprime credit derivatives, which were at the heart of the Global Financial Crisis of 2008, amply illustrates the fact that certain financial innovations can have even more catastrophic consequences than the risks against which they were intended to hedge. Some years later, an even worse result was found by Momi (2001): once the constraints induced by incomplete markets on production are taken into account, Walrasian equilibria may even fail to exist.13

There are many other negative results surrounding the alleged invisible hand. For instance, equilibria (if they exist) may not be stable for any type of out-of-equilibrium dynamics; they may also fail to be Pareto-optimal as soon as production exhibits increasing returns to scale or if some kind of externality (such as climate change) is not internalized by markets, etc. So much so that the general conclusion from GET is rather as follows: the inability of markets to lead to efficient equilibria (if any) is the rule rather than the exception.

5. A Pluralistic View of the Jewish-Christian Traditions

Having suggested that not all of our current understanding of how markets work can be epitomized by Smith’s invisible hand, this section argues that not all of the Jewish-Christian traditions can be summed up in the trajectory described by Agamben from Tertullian’s Trinitarian theology to Smith’s invisible hand.

5.1. Cain as the Anti-Homo Sacer

The figure of homo sacer drawn by Agamben (1998) is not of Christian or Jewish origin but refers to archaic Roman law. As such, the universal figure of the arbitrariness of sovereignty that the Venetian thinker claims to identify in homo sacer is not part of the grand anti-Christian narrative that Agamben wants to promote. On the contrary, the Jewish-Christian Scriptures may even provide us with elements to suggest that the figure of homo sacer as Agamben conceptualizes it is foreign to the biblical perspective.

The fate of homo sacer is indeed exactly what Cain fears and he tells God that it is too heavy a burden to bear: “I will have to hide myself far from your face and I will be a wanderer wandering the earth: but the first comer will kill me!” (Gn 4:14). However, the answer of יהוה means that the God of the Bible, that of the Yahwist tradition in any case, could not resolve to let a man suffer the fate of a living person doomed to wander while awaiting death: “Yhwh answered him: ‘As well, if someone kills Cain, he will be avenged seven times’ and Yhwh put a sign on Cain, so that the first comer would not strike him.” As Alain Gignac (2010) points out, the Massoretic text does not allow us to attribute to the Lord the curse that struck Cain. If we punctuate v. 10–11 in four members, “we realize that the curse can be attached just as much to what precedes (the voice of Abel’s blood) as to what follows (the mouth of the humus which swallows the blood)”. It is the divine program for Adam and his descendants stated in Gn 3:17, and the program of Eve for Cain affirmed in Gn 4:1, which are at the same time definitively blocked: “When you serve the humus, he will no longer add his strength for you”. According to Gignac, concerning those who would dare to hurt Cain, the use of the Hebrew passive “to be avenged” or “it will be avenged” allows the narrator not to mention who will be the avenger. If we make it a divine liability, God becomes implicitly in solidarity with Cain. But we can also choose to keep the ambiguity of the text: we simply do not know who will avenge the vagabond if he were to be killed in the manner of the Roman homo sacer. At the moment when the relationship between God and Cain, already torn by the rejection of the offering, then the murder of the younger brother, seems to be broken by the curse of the ground, the Lord seems to propose another, dialogical bond with the murderer. Does not God himself take the initiative four times in a discussion with Cain, to which the latter ends up consenting despite (or because of) his crime? Cain finally speaks to the Lord and the latter states that he will not be delivered up to vengeance.

This founding text of the Torah therefore immediately opens a breach in Agamben’s archeology: at the end of the monarchical period, perhaps under the reign of Hezekiah (date on which historico-critical exegesis presumes most of the Yahwist document of the Gn was compiled), the biblical tradition contains within itself the resources of a critical relationship to the concept of sovereignty as understood by the Italian philosopher. Indeed, the book of Genesis tells the story of a Lord whose sovereignty seems to require, on the contrary, the establishment of a dialogue with that which the humus had dedicated to becoming: a wanderer offered to the mortal blows of the first comer. Far from decreeing its exclusion, the God of Gn 4:1–15 is a God who speaks with, and protects, bare life. Better still, it makes possible the reintegration of ζωή into βίος since Cain, the narrator tells us in Gn 4.17, “will sojourn in the land of Nod” and will become a “city builder”.

5.2. Oἰκονομία as the Care for the Singular

Finally, I would like to show that Agamben’s (2011) analysis relies on a somewhat one-sided interpretation of the patristic notion of οἰκονομία, namely as an immanent, domestic and providential management process of history. Indeed, this section will suggest that οἰκονομία is actually a polysemic concept, whose meaning can hardly be reduced to the one emphasized by Agamben for the purpose of his grand narrative. Namely, one can find, e.g., in the work by Gregory of Nazianzus, a quite different hermeneutic of οἰκονομία—also based on a Trinitarian theology but with a distinctive understanding of pneumatology. This at least suggests that Agamben’s genealogy, however impressive it is, may not capture all the Christian traditions inherited from the Church fathers.

Several scholars have criticized Agamben’s interpretation of the Church fathers’ Trinitarian legacy. Leshem (2014) disagrees with Agamben’s reading of the highly speculative debates on the Trinity. In Leshem (2014), he offers his own rendition of what a correct genealogy of “neoliberalism” might look like14. According to him, during the classical Greek period, needs were unlimited by nature. Saving, or reducing one’s involvement in productive activities, would free up time to participate in the life of the city. As a consequence, the economic sphere was distinct from, and subject to, the political one. In the Christian era, by contrast, the freedom conquered by leisure would no longer be exercised outside of the economic realm to which the political sphere would, now, be subordinated. Oἰκονομία would no longer refer to the proper management of the household but rather would characterize the relationship to God. In particular, Gregory of Nyssa’s famous distinction between two types of οἰκονομία—that of material desires, which is upper-bounded by satiety, and that of God’s desire, whose growth is by definition unbounded—would have offered the transition between Ancient Greece and contemporary “neoliberalism”. Our modern conception of economics as a quest for infinite growth would therefore come from the Cappadocian’s theology. Obviously, Leshem’s perspective is both close to Agamben’s and radically different. His alternative grand narrative, however, also suffers from important potential shortcomings (Oslington 2018) was transposed into an idle sovereign surrounded by his bureaucracy, the burden of proof is now on the mechanisms by which the infinite desire for God would have been transposed to the material sphere despite Gregory of Nyssa’s emphasis on the distinction between the two types of οἰκονομία. Let us therefore suggest another reading of the Cappadocians.

Gregory of Nazianzus’ letter 58 to Basil of Caesarea is a perfect illustration of the ambiguity and richness of οἰκονομία. Involved in a violent conflict with heretics who contested the Trinitarian formulation of the divine mystery, Basil is said to have partially killed the rigor of the dogmatic formulation of the Trinity in order to preserve the unity of the Church. He was then accused of cowardice by the “rigorists”, those who claimed to show ἀκριβεία in their literal reading of the conciliar formulations. Basil then received the support of his friend, Gregory, written in terms of an “economy of truth” that are worth recalling:

“It is better to economize the truth [οἴκονομητεναι τὴν ἀληθείαν] by yielding a little to circumstances as to a cloud than to compromise it by a public declaration that reveals all [..]. The assistants did not accept this economy. They cried out that this was the doing of the managers [ὀικονομούντων] of cowardice and not of speech. As for you, divine and holy friend, teach us how far we must go in the theology of the Spirit, what terms we must use, how far we must be thrifty [μέκρι τίνος οἰκονομήτεον] to maintain these truths in the face of our contradicts”.15

Faced with the acribia of those who practice a literal interpretation of dogma, the two Cappadocians promote an astute testimony of whose aim is to preserve the unity of the ecclesial body. Significantly for us, Gregory goes so far as to prefer this hermeneutical intelligence to a “public declaration that reveals all”. Of course, this in no way means that any interpretation of dogma is licit; instead, it is a question of yielding “a little” to circumstances in the testimony we produce. What does “a little” mean? How far should we go? This is precisely the question Gregory poses to Basil, asking him, who is accused of having “sold out” the truth, to shed some light on it. The issue of the limit cannot be decided without deliberative discernment, which is what the two theologians are doing. What resources will enable such delicate discernment? It is the “economy” of the Son who, in the Spirit, dispenses the gifts of his Father as a good “steward”:

“We’ll say it right away: every nature in creation, whether it belongs to the visible or the intelligible world, needs divine solicitude in order to endure. That’s why the Demiurgean Word, God Monogenes, grants his help in proportion to the necessities of each [κατὰ τὸ μέτρον τῆς ἑκάστου χρείας] providing in addition varied resources of all kinds according to the diversity of his obliged, perfectly proportioning them to each according to the urgency of his needs [τὴν βοήθειαν ἐπινέμων, ποικίλας μὲν καὶ παντοδαπὰς διὰ τὸ τῶν εὐεργετουμένων πολυειδές συμμέτρους γε μὴν ἐκάστῳ, κατὰ τὸ τῆς χρείας ἀναγκαῖον, τὰς χορηγιάς ἐπιμετρεῖ]”.16

If the two theologians can allow themselves not to share the whole truth publicly, but to dispense it (dispensatio) with οἰκονομία, to the extent that their interlocutors can grasp it, it is because, in their view, God the Father does not act otherwise with his own.17 For it is his solicitude, ἐπιμηλεία, that sustains the world by bestowing his gracious benefits. Far from the Deus otiosus put forward by Agamben, without the Father’s action, creation could not “endure” in history. How could we not find here, of course, the promise of the gift of the δύναμις of the Spirit made by the Risen One (Acts 1:8) to the Eleven? What we learn, however, is that this gift is granted according to each person’s needs, ἑκάστου χρείας, according to an οἰκονομία commensurate with each person’s singularity. We find here explicitly the “community” practice described in Acts 4:34–35 about the early Church:18

“For there was not a needy person among them: all who owned fields or houses sold them, and brought the price of what they had sold, and laid it at the apostles’ feet; and distributions were made to each according to his need.”(Acts 4:34–35, emphasis added)

According to Gregory and Basil, the gift of the Spirit in history by the Father therefore follows the same “economic” logic as that which governed the sharing of goods: intended for all, it is adapted to the needs of each while respecting what makes each of us incomparable. It is this proportionality of the gift of the Spirit to its recipient that signs the “economic” character of the “management” of history by God. It is this which, in return, authorizes our two theologians to choose in what “proportion” it is appropriate to share dogmatic truth with their interlocutors. Of course, what is aimed at is an agreement of homology (ὁμολογία) with the latter, but it is not a question of achieving a uniformity of opinion by means of the travesty of the truth, as Agamben sees glory functioning; instead, it is appropriate to share in a way that is adjusted to the uniqueness in becoming and in relationship of each, to the way in which the gifts of the Spirit are “dispensed” by the Christian God. Not only would this narrative provide an alternative to Agamben’s anti-Christian criticism, it would also, to a certain extent, be complementary to the one introduced by Leshem (2016). Indeed, provided the adjective ‘economic’ is understood in the Cappadocian way, it suggests that, being based on the impossibility of satiety of needs and, above all, on the massification of standardized desires, “neoliberalism” follows an “anti-economic” logic.

6. Conclusions

Agamben’s (1998) major thesis is undoubtedly a powerful and impressive one. Sovereignty as such would be a concept devoid of any transcendent foundation but would consist in the ability of the sovereign to draw the frontier between ζωή and βίος. At a time where autocratic and populist regimes seem to threaten the very idea of democracy, there is little doubt that both the worldwide crisis induced by the multiplication of refugees and by global warming (the second reinforcing the first) can be viewed as a blinding illustration of this radicalization of Schmitt’s celebrated take on sovereignty as the capacity to decide the exception. According to Agamben (2008), moreover, the Christian Trinitarian theology inaugurated in the second century would have the Platonic ontology into being as presence (the Father) and being as action (the Son and his Spirit). This ontological dualism would be responsible for the political theology that still underlies our modern democracies where the media glory plays the role of the antique acclamatio, sealing and unveiling at the same time the void of the Father’s sovereignty, whilst bureaucratic administration takes over the silent and immanent action of the Son—his oἰκονομία. This understanding of history as a “providential machine” would have eventually led to Smith’s idea of the “invisible hand” and ultimately to today’s market fundamentalism.

This paper argues, however, that this thesis can hardly be received as an account of the entire Ancient and Christian trajectory of the West. Two reasons for this have been given. First, even mainstream economics (namely general equilibrium theory) acknowledges that the invisible hand is a myth: whenever they exist, Walrasian equilibria in decentralized markets are almost never Pareto-efficient. Therefore, an exhaustive rendition of the contemporary Western understanding of the economy must also consider the capacity of modern economic theory to contradict the contemporary mythology. Second, within the Jewish-Christian traditions, there are literary currents which operate in reverse relation to those identified by Agamben in his grand narrative. In Gn 4, for instance, Cain can be viewed as a biblical figure who epitomizes an anti-homo sacer. Next, Gregory of Nazianzus and Basil’s pneumatologies sketch a very different conception of oἰκονομία from the “providential machine” analyzed by Agamben (2011). This does not mean that Agamben’s analysis is erroneous but simply indicates the following: to give more force to his argument, the Venetian philosopher had to leave in the shade certain aspects of the very rich history of the West which do not tally with his own account. While Homo Sacer aims at proving that economy as such is religion and Christianity as such is economy, one finally must concede that only one aspect of our current understanding of economy is intrinsically religious—namely the faith in the invisible hand—and only one aspect of Christianity can be identified with the theological roots of this modern “market religion”—namely a certain version of the Trinitarian theology of the second century that would deliberately ignore the pneumatological refinements brought by the Cappadocians of the fourth century. This means, at least, that another grand narrative needs to be written, one where the coexistence of these different contradictory aspects of Western traditions can be made intelligible.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | As accurately observed by one referee, research articles in economics that do not adhere to this postulate (or do not seem to believe that its is even possible to conform to it) receive rejection from the main top academic journals (Heckman and Moktan 2020). |

| 2 | As observed by one referee, this very familiar paternity claim that lumps Mandeville and Smith together is somewhat contradictory since Adam Smith wrote notably against Mandeville’s claim that private vices lead to public virtues (Sternick 2023). |

| 3 | On the distinction between mainstream, orthodox and heterodox economics, see Dequech (2014). |

| 4 | For an in-depth comparison between Agamben and Foucault, see, e.g., Genel (2004). |

| 5 | This is blinding in the Italian media inherited from the Silvio Berlusconi era, but Agamben’s diagnosis claims to be relevant for Western democracies as a whole. |

| 6 | «Siamo cittadini nel corpo naturale di cui è in gioco il loro essere politico», Il Potere sovrano e la nuda vita, op. cit. p. 202. |

| 7 | This in itself is not an uncontroversial statement. For a radically different perspective, see Fassin (2006), who argues that Foucauldian biopolitics is not a politics of life, but rather of the governmentality of populations and ethical self-care. |

| 8 | From a political viewpoint, Agamben logically concludes that we need to free ourselves from the State and all forms of sovereignty in order to engage, at last, in the ethics of emancipated “forms of life” (forma vitae). To do this, we need first and foremost to free ourselves from the theological–political legacy of Christianity, the main mediator between what was inaugurated with the Roman figure of homo sacer and the spells of “media glory” by which the contemporary state conceals the biopolitical basis of its sovereignty. What this would imply in economics remains obscure. |

| 9 | The famous locution, rex regnat sed non gubernat, comes from Erik Peterson’s (1935) treatise. It is attributed by Carl Schmitt (1970), p. 42, to a polemic against Sigismund III Vasa, King of Poland (1587–1632). Both Peterson and Schmitt are key authors commented at length by Agamben (as well as their own internal controversy, of course). |

| 10 | At least in the way Nietzsche has been interpreted by Heidegger (1996). |

| 11 | Agamben’s interpretation of Tertullian relies extensively on the French theologian Moingt (1966). |

| 12 | They even fail to be “second-best” optimal, but I will not enter into the details here. |

| 13 | More precisely, they fail to exist for a non-negligible, open subset of parameters of the economy. |

| 14 | Since Agamben does not use the vocabulary of “neoliberalism”, I will refrain from entering the debate on its definition and historical delimitation, see Audier (2012). |

| 15 | G. of Nazianzus, Lettres, trad. fr. P. Gallay, Belles Lettres, t. 1, 1964, p. 76. The translation is my own. |

| 16 | Basil of Caesarea, Treatise on the Holy Spirit, trans. fr. B. Pruche, Cerf, 1947, p. 312. |

| 17 | The whole of the Basilian Treatise is, moreover, “economic” in the sense that its author shows that the Holy Spirit is not a creature, even superior to the angels; that he is in no way inferior to the Father and the Son; and that he is entitled to the same praise as them. Nevertheless, nowhere in the thirty chapters of the book does he attribute the name of God to the Spirit. This is no doubt due to the climate of theological battle that reigned in Cappadocia around 374—following the Council of Nicaea, which had said nothing about the divinity of the Spirit—and to his concern not to offend his Arian opponents, while at the same time sparing readers of wavering faith. |

| 18 | The lexicon of κοινός is discreetly present, in this place, under the pen of Basil, through the echo of Acts 4:35. |

References

- Agamben, Giorgio. 1998. Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life. Redwood City: Stanford University Press, originally published as Homo sacer. Il potere sovrano e la nuda vita, 1995 Giulio Einaudi editore s.p.a. [Google Scholar]

- Agamben, Giorgio. 2008. The Signature of All Things. Translated by Luca D’Isanto, and Kevin Attell. Brooklyn: Zone Books, [Signatura rerum. Sur la méthode, Paris, Vrin.]. [Google Scholar]

- Agamben, Giorgio. 2011. Homo sacer II,2—The Kingdom and the Glory- For a theological Genealogy of Economy and Government. Redwood City: Stanford University Press. first published as Il Regno e la Gloria. Per una genealogia teologica dell’economia e del governo, Vicenza, Neri Pozza. [Google Scholar]

- Arrow, Kenneth J., and Gerard Debreu. 1954. Existence of an equilibrium for a competitive economy. Econometrica 22: 265–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, Tony. 2009. Economics as a Moral Science. Economica 76: 791–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audier, Serge. 2012. Néo-libéralisme(s): Une archéologie intellectuelle. In Collection Mondes vécus. Paris: Grasset. [Google Scholar]

- Dequech, David. 2014. Neoclassical, mainstream, orthodox and heterodox economics. Journal of Post Keynesian Economics 30: 279–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elul, Ronel. 1995. Welfare Effects of Financial Innovation in Incomplete Markets Economies with Several Consumption Goods. Journal of Economic Theory 65: 43–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassin, Didier. 2006. La biopolitique n’est pas une politique de la vie. Sociologie et Sociétés 38: 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geanakoplos, John, and Heracles M. Polemarchakis. 1986. Existence, regularity and constrained sub- optimality of competitive allocations when the asset structure is incomplete. In Uncertainty, Information and Communication: Essays in Honor of K.J. Arrow. Edited by Walter P. Heller, Ross M. Starr and David A. Starrett. New York: Cambridge University Press, vol. 3, pp. 65–95. [Google Scholar]

- Genel, Katia. 2004. Le biopouvoir chez Foucault et Agamben. Methodos 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gignac, Alain. 2010. Caïn, protégé du Seigneur? Les voix de Gn 4,1-16 dans une perspective narratologique. Théologiques 17: 111–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Giraud, Gaël. 2021. Why Economics is a Moral Science: Lifting the Veil of Ignorance in the Right Direction. In Law, Economics, and Conflict. Edited by Kaushik Basu and Robert C. Hockett. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goodchild, Philip. 2003. Capitalism and Religion—The Price of Piety. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Heckman, James, and Sidharth Moktan. 2020. Publishing and Promotion in Economics: The Tyranny of the Top Five. Journal of Economic Literature 58: 419–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidegger, Martin. 1996. Nietzsche I (1936–1939). XII. Edited by Brigitte Schillbach. Frankfurt: Verlag Vittorio Klosterman. [Google Scholar]

- Leshem, Dotan. 2014. Embedding Agamben’s Critique of Foucault: The Theological and Pastoral Origins of Governmentality. Theory, Culture & Society 32: 93–113. [Google Scholar]

- Leshem, Dotan. 2016. The Origin of Neoliberalism: Modelling the Economy from Jesus to Foucault. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moingt, Joseph. 1966. La Théologie trinitaire de Tertullien. Paris: Aubier. [Google Scholar]

- Momi, Takeshi. 2001. Non-existence of equilibrium in an incomplete stock market economy. Journal of Mathematical Economics 35: 41–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, Robert. 2001. Economics as Religion: From Samuelson to Chicago and Beyond. University Park: Penn State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Oslington, Paul. 2018. Dotan Leshem, The Origins of Neoliberalism: Modeling the Economy from Jesus to Foucault. Journal of the History of Economic Thought 40: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, Erik. 1935. Der Monotheismus als politisches Problem: Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der politischen Theologie im Imperium romanium. Leipzig: Hegner. [Google Scholar]

- Pseudo-Denys the Areopagite. 1958. La Hiérarchie celeste. Translated by Maurice de Candillac. Sources chrétiennes, 501n◦ 58bis, Editions du Cerf. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/20859197 (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- Schmitt, Carl. 1970. Politische Theologie II—Die Legende von der Erledigung jeder politischen Theologie. Berlin: Duncker & Humblot. [Google Scholar]

- Segré, Ivan. 2017. Giorgio Agamben, philosophe messianique—Penser un ordre politique (véritablement) révolutionnaire. Revue du Crieur 3: 116–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shachar, Kariv, and William R. Zame. 2008. Piercing the Veil of Ignorance. Working Paper Series qt994512r7. Berkeley: Department of Economics, Institute for Business and Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Shefler, Jonathan. 2012. Harvard Business Review, April 10. Available online: https://hbr.org/2012/04/there-is-no-invisible-hand (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Stang, Charles. 2020. Giorgio Agamben, the Church, and Me. Harvard Divinity Bulletin. Available online: https://bulletin.hds.harvard.edu/giorgio-agamben-the-church-and-me/ (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Sternick, Ivan. 2023. Society as a moral order: Adam Smith’s theory of sociability as a response to Mandeville and Rousseau. Nova Economia 33: 211–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Charles. 2007. A Secular Age. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).