Abstract

Sufism has played a critical role, particularly in the past millennium, as one of the most significant cultural components in the history of Iran. And approximately all cultural factors, including arts, politics, economics, and the educational and training system, have been directly and indirectly influenced by the Sufi culture. One such factor is music, which has been uninterruptedly intertwined with Sufism for years. The present paper strives to investigate the extent to which and the ways in which Sufism has influenced contemporary Iranian music. The answer to this research inquiry is crucial for understanding the impacts of Sufism in the contemporary era and dissecting Iranian music, most specifically the Persian modal system (dastgāh). Despite the significant factors that contribute to the Persian musical system, the literature on the topic remains scarce. This research uses historical and research analysis, as well as the results of a field study conducted over the past two decades in the educational atmosphere of the Iranian musical system, to answer the research questions. The findings suggest that contemporary Iranian music has derived considerable influence from Sufi subjects, concepts, and teachings, and evolved thereafter, with dramatic impacts in two epochs: (1) throughout the thirties and forties HS; and (2) in the wake of the Islamic revolution.

1. Introduction

The correlation between Sufism (ʿirfān) and music is enduring, wavering, and remarkable—as if they share a common foundation that also guides their respective audiences. Sufism and Iranian music are no exception; they are intertwined and share a reciprocal relation: music has reinforced Sufism intermittently and has provided an impetus for Sufis to traverse into the valley (wādī) of rapture (wajd) and intimacy, and sometimes music has found solace from the institutional power or lesser understandings by seeking refuge within Sufism (see Muḥammadīyān et al. 2018, p. 58; Gīlānī and Zamānī 2021, p. 174), where it remained and evolved over a period.

Sufism’s inclination towards music can be attributed to several reasons. On one level, the audition (samāʿ) and the intellectual cosmology are significant components for Sufis of the first and second mystical traditions (for related issues to ontology see Ernst and Lawrence 2002).1 In a broader sense, (naturally, certain types of) music influenced Sufis and they experienced ecstasy (khalṣah) and self-lessness (sukr).2 Moreover, some Sufi orders that integrated music as a social component strengthened their social institution such as lodges, known as khānqāhs.3 Additionally, due to several factors, music became closely associated with Sufism. In certain historical periods, the institutional power relied on religion or secured its legitimacy by means of religion. As a result, religious perspectives and teachings profoundly shaped social institutions and interactions. In those instances, surviving inaccurate conceptions and lesser understandings transmitted by exoticists intervened in musical activities. This consequently restricted musicians from performing, and it varied in intensity, particularly in the twelfth to fifteenth centuries (see Qureshi 2013, p. 584). During these eras, music turned to Sufism and consecutively persisted based on the legitimacy of Sufi lodges (khānqāh), liberating them from repression.

Secondly, in diverse historical periods, Sufis were incredibly acknowledged and famed. Succeeding the Mongol’s invasion, for instance, kings received their legitimacy from Sufis (Ḥusaynī Turbatī 1963).4 Inevitably, musicians were attracted to becoming spiritual wayfarers or befriending famous Sufis (Miller 1999, p. 15; Manz 1989, pp. 17–18).

Thirdly, as evidenced in historical accounts, a significant volume of Iranian music consists of vocal pieces which were accompanied by poetry (Nettl and Babiracki 1992, p. 191). In fact, Persian poetry was largely influenced by Sufism to the extent that some of the prominent Persian poets were Sufis, including Sanāī, ʿAṭṭār, Mawlawī, Ḥāfiẓ, and Jāmī, or benefited a lot from Sufi teachings in their poems, such as Niẓāmī, Khāqānī, and Saʿdī. It is thus inevitable that Sufi poetry served as an important resource for vocal music (āwāz). For this reason, Sufi themes, teachings, concepts, subjects, and forms were consequently incorporated into poetry.

The past millennium constitutes one of the most important periods in which Sufism and music have been intertwined. Considering the diverse political, cultural, economic, martial, and diplomatic turns over this time, as well as the noticeable cultural paradigm shifts, the connection between Sufism and music appeared to be in an unsteady flux. Understanding the current nexus between music and Sufism, as well as their unique place in Iranian culture, is important for explaining the country’s artistic and cultural state.

There is scarce literature on the topic, and existing scholarly investigations do not meet the needs of researchers. The purpose of this research is to shed light on the correlation that exists between Sufism and music in modern Iran and to reveal the context in which Sufism influenced music. In doing so, the study first explores the historical documents, and simultaneously explores evidence from field studies in the education of Persian modal system (mūsīqī-i dastgāhī),5 and finally offers a clear and precise picture of how Sufism has affected contemporary Iranian music. Due to the paucity of literature on this topic, the study uses subjective analysis.

2. Literature Review

Since the first decade of the twenty-first century CE, there has been a correlation between mysticism, or Sufism, and researchers showing interest in studying music. Some studies have been conducted on the integrity of mysticism and music globally, including in the Middle East, Canada, and Spain. Many of the studies on music and Sufism have focused on the connection between classical Persian Sufi poetry, ecstasy, whirling, and music. However, research on the correlation between Sufism and music in contemporary Iran is limited.

Much of the western study of Iranian music and modal systems and Sufism has been on the explication of the Persian modal system and structure,6 the subjective experience of Sufism (See Güner 2022), and the integrity of Sufism and music or poetic forms in medieval times;7 these studies primarily emphasize the importance of ghazal or odes (qaṣīdah) and hearing in Sufi traditions, which has also been explored in Mawlāwī’s Dīwān and Qadiriyya order. And the existing literature in Persian outlines two major trends streaming throughout the thirties and forties HS in the Iranian musical system (Nikūī and Parwīz Zādah 2020). A group argued for the Sufi orientation of the musical system, and another refuted and criticized this trend. They indicate that Gul-hā (a musical radio program) was abundant with Sufi motifs. It is possible to take a critical look at their discussions; however, it is beyond the scope of this research. Other scholarship on the topic is baseless, inefficient, unrestricted, and unsystematic, and—notwithstanding their use of grandiose language—they are ineffective.

Examining the impact of Persian Sufi poetry and contemporary music, this study seeks to bridge the gap between the medieval period and the present, focusing on Iran and examining the components that have shaped contemporary music.

3. Sufi Discourse in the Contemporary History of Iran

Sufism has significantly contributed to the formation of other cultural and social components throughout Iran’s history and geography.8 Sufism has unavoidably encountered advocates and opponents.9 There were two groups of people that advocated Sufis: 1—kings and other authorities who gravitated towards or appreciated Sufism, like the Safawid kings (Tamīmdārī 1993, pp. 58–63); 2—artists and writers who incorporated Sufism into their works. On the other hand, critique writers (raddīyah-niwīs) opposed Sufism and played a significant role in the formation of opposing movements of Sufism in Iranian history. These critiques spread from the fifth century AH in scientific texts; for example, Ibn-i Jawzī’s Talbis Iblis (The Devil’s Deception) criticized the beliefs and practices of Sufis. This tradition evolved during the Safawid era (ʿAbdī and Zarqānī 2017, pp. 119–23; Jaʿfarīyān 2019, pp. 515–686). In several historical periods, the institutional power or groups of the society opposed Sufism, whereas during the thirteen previous centuries, Sufis were moral, spiritual, and upright men, and they made a living through their profession to the end of the fifth century. This shows that they interacted with people from all walks of life and they were acclaimed and respected in the society.10 It is worth noting that up until the seventh century AH, the social system of Sufis was unstructured and Sufi abodes gained a lesser degree of legitimacy as social institutions from the power institution.11 This is demonstrated by the subjects that Sufis discussed in their texts prior to the Mongol’s invasion. Consequently, Sufism and Sufis were unable to exert a strong influence on the culture and people of the society. Therefore, each officially recognized Sufi or Sufi order played an important role in the society (Safi 2000, p. 264), while the skeptical attitude of a king or officials led to the seclusion of Sufi views and their tragic deaths.12

Accordingly, it can be asserted that Sufism—as one of the major social components in Iran during the first mystical tradition—had a less significant place in the community, and this is reverberated in poetical and prosaic works.13 The Mongol’s invasion and the emergence of the second mystical tradition changed the climate.

Mongol’s invasions profoundly affected Sufi-inspired topics, teachings, and fundamentals.14 Consequently, Sufism played a significant role in the formation of social institutions and the emergence of topics like the arts in Iran and beyond.15 During this period, Sufis played an active role in the political and martial power structures, and diverse Sufi orders engaged in correspondences or interactions with the governments in the hope that power may be shared with them,16 and over time, Sufism infiltrated all aspects of society, particularly the arts: literature, music, calligraphy, painting, typography, etc. This marked the beginning of a new artistic era in Iran (see Muḥammadīyān et al. 2018, p. 58; Gīlānī and Zamānī 2021, p. 174), and the impact persisted into the tenth and fourteenth centuries AH, whereas what we witness in the contemporary age is a constitution of impacts from the seventh to tenth centuries AH, when Sufism first emerged and penetrated the arts and social dimensions in Iran.

It is possible to compare the influence of Sufism on society and the arts to a fruit tree that was planted in the seventh century AH and has sprawled into the modern era. More broadly, prior to and after the Islamic Revolution (1979 CE), Sufi fraternities who were either dissidents or advocates of the institutions of power contributed greatly to the social realms, and this has been a consistent pattern throughout the history of Sufism.17 In addition, Sufis were socially recognized, and influenced artists in their sociopolitical climate.18 This is the reason Iranian art and handicrafts were influenced by Sufi perspectives. For example, colors and patterns adopted from Sufi texts are evident in paintings and marquetry products.19 Presently, Muslim artists across the world adopt Sufi practices, and we will specifically further discuss Iranian music in the article.20 Sufism received significant attention through the circulation of shīʿah religious discourse in the post-revolutionary era of Iran.21 As a result, Sufi teachings and perspectives have had a significant role in contemporary Iranian culture and have had a powerful impact on artists and arts in this period.

4. The Impact of Sufism on the Contemporary Iranian Music

As already explained, Sufism exerted a profound impact on multifarious arts, such as music, from the seventh century AH onwards. Following the Islamic Revolution, Sufism spread throughout the society. Despite the impact of Sufism on diverse forms of music, including the musical system, pop, rock, opera, and integrated music, this is most evident in the Persian musical system. The intersections that highlight the impact of Sufism on music should be divided into four groups:

- (1)

- Musicians who were Sufis or knew about Sufism;

- (2)

- The educational system of music;

- (3)

- The musical-Sufi assemblies;

- (4)

- The Sufi poetry set to music productions.

4.1. Musicians Who Were Mystics or Knew about Sufism

One of the best examples of the correlation between Sufism and music is the appearance of composers, instrumentalists, vocalists, and producers who associated with Sufis and gained an understanding of the Sufi orders. As historical documents show, several artists were Sufis or showed interest in them. These include: Dāwūd Pīrnīā, musician and producer (Lewisohn 2009, p. 114; Nikūī and Parwīz Zādah 2020, p. 216); Rūḥullāh Khāliqī, musician and instrumentalist; Ismaʿīl Adīb Khwānsārī, vocalist; ʿAbd al-Wahhāb Shahīdī, instrumentalist and vocalist; Mīzā Ḥusayn Qulī Farāhānī, musician and tār instrumentalist; Mīzā ʿAbdullāh Farāhānī, musician and tār instrumentalist (Nikūī and Parwīz Zādah 2020, p. 217); as well as Samāʿ Ḥuḍūr, santūr instrumentalist (Ṣafwat 1982, p. 341); and Muḥammad Riḍā Shajarīyān, who had religious orientations and recited the Qurān, should be included in the list (Muțlaq et al. 2006, p. 276).

Sufi thought and teachings, as well as Sufi aesthetics, have permeated the Persian musical system due to the importance of the aforementioned figures, and it took several decades for people to understand that this also happened in music in the same way.

To promote their Sufi teachings and beliefs, these figures engaged in music productions, and some others indirectly (consciously or unconsciously) integrated their theoretical bases and Sufi aesthetics into the musical cosmos. Adīb Khwānsārī, who was the first contemporary vocalist, used Mawlawī’s poetry22 extensively in his vocal music (āwāz), and he was the first to incorporate the poetry of Ḥāfiẓ23 into Iranian vocal music (Adīb 2006, p. 150).

4.2. The Educational System of Music

Sufism has widely exerted influence in diverse musical spheres. For example, one of these spheres is the educational system of music. Historical evidence, particularly Futuwwah-nāmahs, points to the relationships between teachers and students in arts education (Siyfī et al. 2016, pp. 39–40). The results of a two-decade field study (i.e., oral communication with traditional music tutors and students as well as in-time observation of classes) illustrate the extent to which the educational system of Sufism, especially the spiritual guide (murād)/disciple (murīd) relationship of the first mystical tradition, influenced the teaching of arts and music (see Qureshi 2013, p. 592; Zuhrahwand and Furūtan 2021, p. 9).24 It can be said that the process of teaching the musical system can be compared to the interaction between the spiritual guide and disciple, meaning that if there is no murād/murīd relationship between the tutor and the student, the instruction process will be inefficient and incomplete. There is ample evidence that the student sincerely deepened his relationship with the master to learn a single mystery of learning music at the discretion of the spiritual guide. Though this method is compatible with the modes of instruction in today’s world and it is effective and appropriate for teaching Iranian music, extreme forms of this relationship may also interrupt the learning process and it prevents both the tutor and the student from journeying the path to perfection (sayr-i istikmālī).25

4.3. The Musical-Sufi Assemblies

The assemblies were the most important crossroads of Sufism and music in the twenties HS. Some scholars (Blum 2013, p. 105; Nikūī and Parwīz Zādah 2020, pp. 213–14) believe that Sufism was an essential part of the events that musicians performed and attended, and the musical and non-musical regulations that govern these gatherings created a Sufi and spiritual atmosphere. Such assembles likely set the stage for contemporary Sufi music, while many factors influenced the formation of contemporary Sufi music. Considering the temporary existence of assemblies in the twenties HS, such gatherings had a peculiar function in shaping contemporary Sufi music. In fact, it can be deduced that Sufism affected contemporary Iranian music on two levels: (1) the formation of music in general and of diverse musical forms; (2) the peculiar musical form-creation, known as Sufi music, which also benefits from Sufi elements and practices.

In the early contemporary period, assemblies were seen as antithetical to this-worldly and non-spiritual musical ambience. These newly established assemblies gradually fostered culture within the musical atmosphere (Nikūī and Parwīz Zādah 2020, p. 213), resulting in the predominance of Sufi discourse in a substantial part of Iranian music. Meanwhile, some musicians and non-musicians hurled stinging criticism at such gatherings and wrote about this cultural phenomenon. Since then, criticism from musicians and non-musicians alike has not been fierce enough to prevent the development of Sufi music or strengthen the Sufi-spiritual atmosphere in Iranian music.

4.4. Sufi Poetry Set to Music Productions

The music productions are a significant means of studying the impact of Sufism on music. As discussed earlier, vocal music comprises a significant portion of Iranian music. Furthermore, poetry plays a crucial role in vocal music (āwāz). According to the classical texts written on music since antiquity to present, Sufi poetry has been fundamentally important in musical works (such as ʿAbd al-Qādir Marāghahī). This persisted in the modern era. In light of the earlier mentioned factors—the predominance of Sufi discourse in the cultural atmosphere after the revolution, the appearance of musicians with “a highly spiritual character” (Miller 1999, p. 15) or interactions with Sufis, and the formation of assemblies for the purpose of presenting Sufi music—more and more Sufi poetry was used and circulated in musical productions.

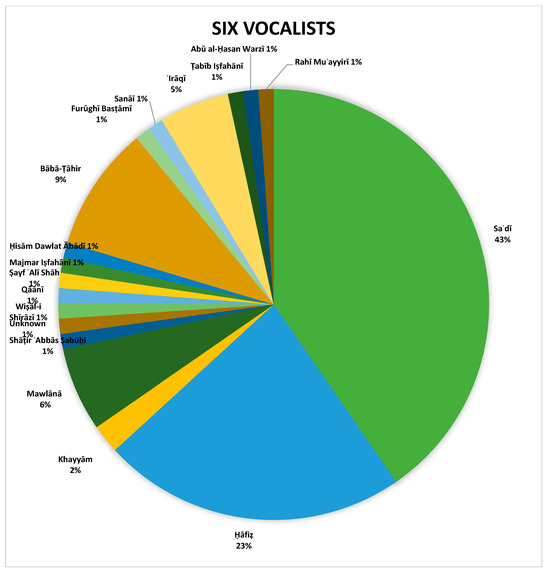

In one study, we examined sixty vocal music pieces by six prominent contemporary vocalists, comparing them in terms of the lyric or epic Sufi poems widely used in these works. Saʿdī, Ḥāfiẓ, and Mawlānā are among the poets whose works have been used in vocals (See Figure 1; Ṣafarī 2018, p. 128).

Figure 1.

Most cited poets.

These works, along with their content, illustrate that the modal systems (pl. for dastgāh) for vocalists used at present have been informed by mystic poets and Sufi poetry the most; however, as was already explained, some of these vocalists either were Sufis or belonged to Sufi orders and Sufi fraternities (țarīqah),26 or they had been trained within the context of religious shīʿah discourse, and thus adopted religious views.27 This study analyzes the works of the prominent and influential Sufi poets and Sufi poetry to illustrate the extent to which vocalists have engaged with them, focusing on the beginning of the contemporary age to the seventies. The list shown in Table 1 was created after conducting field research on students of these vocalists; it is organized in chronological order based on the time of publication (Ṣafarī 2018, p. 3).

Table 1.

Musical works.

Sufi poetry has not been adopted solely in the Iranian modal system. At present, Sufi poetry is widely appreciated by singers and composers, including Ḥusayn Sarshār (Opera singer)28, and several pop music artists including Wīgin, Farāmarz Așlānī, ʿAlī-Riḍā ʿAțțār, Muḥsin Yigānih, Riḍā Ṣādiqī, and Shādmihr ʿAqīlī, who adopted the poems of Mawlawī, and ʿAṭṭār. As already mentioned, however, according to the requisites of solely Iranian modal system of music, Sufi verse was the most prevalent poetry in this musical group.

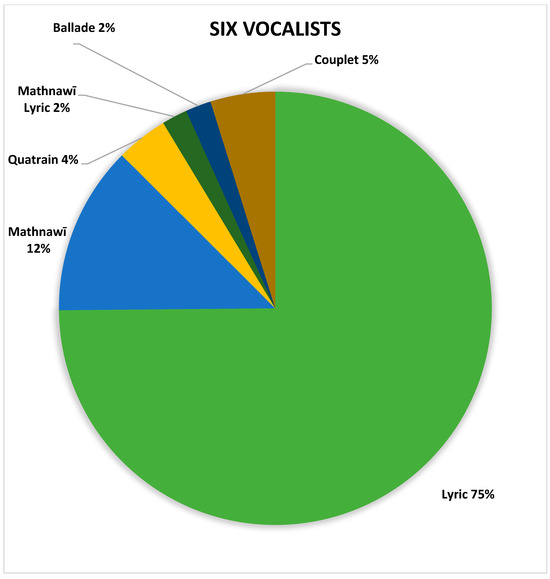

Sufi poetry and modal music twine together in the most common poetic form, i.e., lyric poetry, or ghazal.29 This poetic form is thus the most widely used poetic form in contemporary Iranian vocals, which is formed by music modals. Lyric poetry (ghazal) has been used extensively by the six vocalists. Figure 2 shows the most frequently used poetic forms (Ṣafarī 2018, p. 128).

Figure 2.

Poetic forms.

The similarities between Sufi poetry and modal vocals in using ghazal show that Sufi themes have been reflected in vocals and that the Sufi poetic forms have been considerably influential in Iranian music modals. In effect, Iranian musicians and vocalists have always given great importance to conveying Sufi themes and ideas. They also adapted their musical form to the Sufi poetic form. This hypothesis is strengthened considering that three types of music are discernable in Persian poetry, which has emerged in poetic language: external (meter), lateral (order or radīf and rhyme), and internal (phonological pattern of music). The adoption of Persian poetry in vocals inevitably entails its musicality. Therefore, the musicality of poetry unites with vocal musicality, which results in ‘the synthesis of poetry and music’.30 Therefore, the outcome ought to be enjoyable and favorable for the listener. For this reason, poetry and vocal music must be in harmony. It follows that the musicality of poetry (as one of the components of a poetic form) is effective in vocals, which is also rather imperceptible.31 It is thus possible to suggest that Sufi poetry played an extremely significant role in the formation of modal music, particularly in vocals.

5. Consequences of the Impact of Sufism on the Contemporary Iranian Music

As already discussed, Sufism has influenced contemporary music in four ways and through diverse forms. The result of this influentially is musical productions, which are either known as Sufi music or formalistically conform to Sufi form and content—promoting the Sufi culture and discourse. Among the most important productions are:

- -

- The Gul-hā program: The most important musical productions in Iran in the thirties to fifties broadcasted on National Iranian Radio and Television in 1956–1978 (see Barāzandahnīā 2015, pp. 8–9). Given the long-term production and broadcasting of this program, and the considerable number of contributing artists and works, Gul-hā remains a one of a kind in the history of Iranian music and culture. It has thus far attracted many audiences and has had a profound impact on contemporary Iranian music. Given that almost all of the great masters of that era collaborated with the Gul-hā programs that were produced at the time, this program is significant in terms of its music elements. Almost every musician who emerged after Gul-hā was influenced by the program, and its impact is still alive. Approximately every master and student of modal music thoroughly imitates this program or adopts certain elements of it in his or her musical horizon. Therefore, Gul-hā has had a special role in the modal music of contemporary Iran. Allegedly, this program promoted the Sufic culture in Iranian music for several reasons:

- (1)

- The executive producer of Gul-hā was interested in and identified with Sufism.Dāwūd Pīrnīā, founder of the Gul-hā (Gul-hā-yi Jāwīdān) program, subsequently produced Gul- hā-yi Rangārang, Barg-i Sabz, Yik Shākhah Gul, and Gul-hā-yi Ṣaḥrāī. Known as the gardener of flowers (bāghbān-i Gul-hā), Pīrnīā was the executive of the Gul-hā program for eleven years. According to the evidence, Pīrnīā was deeply interested in and identified with Sufism (Fayyāḍ 2015, p. 204). Moreover, he explicitly appreciated music and Sufi poetry and he attempted to promote and transmit it (Tarraqī 2010, pp. 181–92; also see Nikūī and Parwīz Zādah 2020, pp. 218–19). He strived to use Sufic poetry in vocals and declamations while he encouraged instrumentalists and vocalists with religious beliefs or Sufic wayfaring or those who related to Sufi orders, including Rūḥullāh Khāliqī, Ismāʿīl Adīb Khwānsārī, Ḥusayn Qawwāmī, ʿAbd al-Wahhāb Shahīdī, and more interestingly, Sayyid Jawād Dhabīḥī—who appeared in several beginning episodes of Barg-i Sabz—to contribute to the program. In the first episode from Barg-i Sabz, Dhabīḥī recites a tarjī’ band, or a strophe poem, from Hātif-i Iṣfahānī in which nīst or “there is none” recurs:Kih yikī hast-u hīch nīst juz-ū [That there is One and there is none except Him]Waḥdah-ū lā ilāha illā hū [He is only one and there is none except the only God].Thereafter, the Sufi and spiritual ambience governing the Gul-hā-yi Jāwīdān program explicitly appeared as pieces voiced by religious singers along with Sufi poems.

- (2)

- The process that led to the production of the Gul-hā radio program.Gul-hā was the outcome of Sufi assemblies in Tihrān, specifically those organized by Niẓām al-Sulṭān Khwājah Nūrī, which were its formative stage (Lewisohn 2009, p. 114). Niẓām al-Sulṭān was inclined to Sufism. Together with Pīrnīā and other musicians, he organized sessions in a monastery at his home (Nikūī and Parwīz Zādah 2020, pp. 217–18).

- (3)

- The criticism that the Gul-hā radio program received during its broadcasting.Following their broadcast, Gul-hā episodes gained growing interest among people and exerted cultural impacts in the society. Oppositions to this program then gradually began with modernists and episodes were largely criticized. Diverse groups of people in the thirties and forties expressed their disapproval of the episodes and the conventional Iranian music of the given period in general. Major criticisms have been leveled at the idea that Sufism and music inebriated people’s mind (see for instance, Wāmiqī 1956, p. 16; Anonymous 1957, p. 18), and the program, and modal music more generally, came under heavy criticism (see Khwushnām 1959, p. 21). Regardless of the validity of such criticisms (Nikūī and Parwīz Zādah 2020, p. 206), there were two discourses in the cultural and musical atmosphere of the country during the thirties and forties: Sufi and anti-Sufi discourses. As already mentioned, Gul-hā was incredibly effective in the emergence of the Sufi discourse in contemporary music.

- -

- Muḥammad Riḍā Shajarīyān’s works: The Sufi ambience of Iranian music during the thirties and forties was profoundly ingrained in the wake of the fifties; this coincided with and was infused with the country’s revolutionary atmosphere. Gul-hā was outlawed and stopped in 1978. Some musicians engaged in political and revolutionary issues, some emigrated from Iran, and some discontinued their musical activities. Shīʿīsm, which was closely linked with Sufism, became the dominate discourse in the country. It was expected that fundamental transformations in music would take place in light of the massive changes in Iran. These include, but are not limited to, the totalitarian existence of modal music and marginalization of other music genres such as pop, rock, opera, and even local music; the production of music based on different content, i.e., religious and spiritual songs; widespread adoption of poems by Ḥāfiẓ, Mawlānā, etc. in music; the growing significance of musicians of modal music in promoting a culture of listening and the musical culture of Iran. In the given turning point, one of the vocalists of modal music, who grew up in a devotedly religious family and knew the Qurān by heart, played a significant role in the advancement of a an important movement in the history of contemporary music. Through his participation in approximately 100 episodes from Gul-hā, and his experience with the mentioned programme and his religious background Muḥammad Riḍā Shajarīyān revolutionized the musical ambience in Iran over three decades. Additionally, he exerted a signif-icant influence on the promotion of Iranian music, religion and Sufism by means of his musical productions, the establishment of musical institutions, the cooperation with power institutions, and training students. Although Muḥammad Riḍā Shajarīyān opposed with the governmental politics in Iran in the later stages of his career, his musical experience succeeding the Islamic Revolution spanning to the eighties show that he conformed to the government and promoted Sufi poetry and religious musical forms in Iran. However, works of Muḥammad Riḍā Shajarīyān and his followers subsequent to the Islamic revolution marked a significant moment as Sufism began to exert influence on the contemporary Iranian music.

In addition to the works that indicate the influence of Sufism on music, it is important to consider the following points when examining the impact of Sufism on music in the contemporary era:

- -

- Prior to the contemporary era, there had been no ‘mystical music’ (mūsīqī-i ʿirfānī) or ‘Sufi music’ (mūsīqī-i șūfīyānah) in categorizations of diverse music, including the significant traditional musical works by Ibn Kindī, Abū al-Faraj Ișfahānī, Fārābī, Ibn Sīnā, Ibn Zaylah Ișfahānī, Ikhwān al-Ṣafā, Imām Muḥammad Ghazzālī, and Suhrawardī. For instance, treatises on musical theory from the fifth to seventh centuries AH, including those by Khayyām, Muḥammad Nayshābūrī, and Jāmiʿ al-ʿUlūm by Fakhr-i Rāzī, demonstrate the classification of music into martial music (mūsīqī-i razmī) and festival music (mūsīqī-i bazmī) (see Khaḍrāī 2012, p. 125). This was not true even during the Ghaznawīd and the Ṣafawīd (see Maythamī 2016, p. 135; Masīḥ-Far 2013). As previously mentioned, however, music played a special role in the Sufi lodges (khānqāh) and gatherings for Sufi audition (majlis-I samāʿ), and Sufis engaged in musical activities. Meanwhile, it is worth noting that the Sufi-inspired discourse for interpreting music developed in the contemporary era (Nikūī and Parwīz Zādah 2020, pp. 211–12); consequently, terms such as ‘mystical music’ and ‘Sufi music’ were devised. This proves that the correlation between music and Sufism has transformed in the contemporary era and the position that music occupies in society has changed, i.e., it has gained recognition. One of the fundamental and important changes is that such music found its way from Sufi lodges and zāwīyyah to music halls and homes, and thus received attention. One indication of this transition is the gradual integration of musical instruments like the daf and tambourine, which were traditionally played in Sufi gatherings during the early modern era, into the mainstream music scene. This is evident to the extent that after the revolution, musicians and audiences showed significant interest in instruments like the daf, ultimately leading to its inclusion in musical productions.

- -

- The formation of the musical modal system during the Qajar dynasty and its establishment in the contemporary age, as well as its predominance over different kinds of music in the twenties and fifties and the post-revolutionary period, prepared the ground for the influence of Sufism on music, given that the musical modal system has a firm connection with Sufism (see Ṣafwat 1982, pp. 341–42).

- -

- Although in the post-revolutionary period, jurisprudence (fiqh) and political discussions caused incongruencies and problems in the development of music policies (see Malikān and Muʾadhin 2015, pp. 51–58; Partaw 2020, p. 41), there has been a slight improvement in the field of instruction and production of musical modal system at this time, especially since the seventies (Fatḥī 2008). That is, musical modal system gained popularity shortly after the revolution. It is possible that the dominant discourse in this kind of music aligned with the political-religious discourse in Iran at that time. The Sufi aspects of the musical modal system may have played a role in preventing this kind of music from restrictions and preventing its decline, and contributed to its popularity, as well.

6. Conclusions

The correlation between Sufism and music is an irrefutable fact. Throughout history, Sufism has benefited from potentials of music, and music has, at times, sought refuge within Sufism. In such situations, the Sufi aspects of music gained prominence, were enhanced, and were often referred to as ‘Sufi music’. In contemporary Iran, for several reasons, Sufism has been one of the major formative elements of Iranian music—particularly modal music. Sufism exerted its initial impacts on music more precisely in the twenties HS, and this has continued to the present day, such that a large volume of contemporary modal music draws influence from the Sufi and religious culture. The thirties and forties and several decades after the Islamic Revolution are the most important periods in contemporary history that highlight the impact of Sufism on music. Between 1958 and 1978, Sufi culture infiltrated the official musical atmosphere of Iran, and has been the governing discourse in Iranian music following the revolution.

Based on the discussions in the paper, the following are the most important contexts and factors that contributed to the advancement of Sufism in modern Iranian music: Sufi poetry; audition (samāʿ); Sufi lodges (khānqāhs); Sufi poets and poets that gravitated towards Sufism; vocalists and musicians who gravitated towards Sufism; music assemblies in the twenties and thirties HS; the sociopolitical events throughout the history of Sufism that led to music being closely associated with Sufism, such as the Islamic Revolution and the prominence of the musical modal system succeeding the revolution, and the marginalization of other musical forms; the predominance of Shīʿah-inspired discourse in modern Iran following the revolution.

Moreover, the following are the most significant indications and outcomes of the impact of Sufism on music: the adoption of Sufi poetry in musical productions; the prominence of Sufi poetic form in the musical modal system; the adoption of poetry by renowned mystics or poets who gravitated towards Sufism in musical productions; and the prominence of the spiritual guide (murād)/disciple (murīd) relationship in the education of the musical modal system (as the dominant educational system in the first mystical tradition); and the dominance of the spiritual atmosphere filled with grief and solace over the modal system in contemporary Iran.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation, S.A.A.M.F. and E.R.; writing—review and editing, S.A.A.M.F. and E.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by the University of Isfahan and the Chair for Mawlawi Studies, which operates under the Iran National Science Foundation.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Sufi audition (samāʿ), as an indispensible part of Sufi gatherings, was a state during which Sufis were prompted by poetry and music, leading them to engage in claping and dancing (Zarrīkūb 2002, pp. 96, 175; Gīlānī and Zamānī 2021, p. 170). Note that the term mystical tradition denote two timeframes: the first mystical tradition spans from the midst of the second century AH to the seventh century, and the second mytsical mystical tradition began from the seventh century AH; see (Mirbagheri Fard 2012). |

| 2 | It has been evidenced that there is a proportionality between Sufi audition and disassociation (Avery 2004, p. 78). |

| 3 | In sveral Sufi orders, such as Mawlawīyah and Chishtīyyah playing drumbeats were conventional such as daf or tambourine (see Naṣr 1987, pp. 168, 152; Ḥaydarkhānī 1995, p. 27) and this turned to be a social constitute which was consistent with Sufi manners and teachings. Besides Sufic purposes, this instrumental playings are socially significant as they reinforced those orders—especifically that this was not limited to Persians (see, for instance, Klotz 2013, p. 295). |

| 4 | For example, to gain his legitimacy among the public, the Timurid king attended to the spiritual teacher (pīr) of the Sufi lodges (Manz 1989, pp. 17–18). |

| 5 | Iranian [musical] modal system (mūsīqī-i dastgāhī) is a type of music that is originated in the Qajar period and it is characterized by radīf i.e., a certain collection of systems (dastgāh), vocals (āwāz), and gūshah and to this day it is known as traditional (sunnatī) music, original (așīl) music, and Iranian music. |

| 6 | For instance, Farhat (1990); Nettl and Babiracki (1992); and Miller (1999). |

| 7 | For an overview on music and sufism, see Naṣr (1987); During (2021). Furthur notes on the importance of lyric poetry in Sufi music are available in Macit (2010) and Bağçeci and Özdemir (2021). |

| 8 | Few scholars provided insights from the Safawid and the Qajar eras (Țāwūsī et al. 2022). |

| 9 | Whilst drawing on oppositions, scholars highlight Sufis’ success (Sharify-Funk et al. 2018, pp. 35–61). |

| 10 | Sufis’ occupation, varing from haberdashery and blacksmithing, was a significant part of their social action and they were publicaly acknowledged (Riḍāī et al. 2014, pp. 93–97; Țabāțabāī and Ḥājī-Shaʿbānīyān 2019, pp. 151, 154). |

| 11 | Since early second century AH, sufi abodes evolved from duwayrahs, ribats, and ultimately khānqāhs. From the sixth century onwards, The rise of khānqāhs superseded which was prompted by the socio-political environment, especifically since the seventh centuary AH (Omer 2014, pp. 5–6, 11–14; Tājbakhsh and Murādī 2023, pp. 101–2). |

| 12 | Ḥusayn Ibn Manṣūr Ḥallāj and ʿAyn al-Quḍāt-i Hamidānī were among great Sufis who were assassinated (see Safi 2000, pp. 264, 269). |

| 13 | Akram Mușaffā (2008) provides an analysis of writings in either of the mystical traditions, with a particular focus on the transformations brought by the Moghols. |

| 14 | The mystical texts, in particular, had striking distinctions before and after the seventh century AH (Mirbagheri Fard 2012, pp. 73–74). |

| 15 | Arts inspired by Sufism include, but not limited to music, architecture, painting, and marquetry. See, for example, (Kuehn 2023; Shād-Ārām and Nāmwar 2021; Dawāzdah-Imāmī et al. 2015; Miʿmārzādah 2007, pp. 281–90, 303–6). |

| 16 | Sufis were actively involved in the social and political realms–they opposed Mongols, reproched kings, and supported groups of people; see (Shikarābī 2010, pp. 57–76; Khusrawī 2018, pp. 90–93). |

| 17 | See, for instance, the negilgence of Nādir Shāh towards Sufis (Gulistānah 1956, pp. 27–28) or the rapport between Tiymūr and shaykhs and sufis (Manz 1989, pp. 17–18). |

| 18 | There is evidence to suggest that arts served as a means for Sufis’ wayfaring (Qayyūmī Bīdhindī 2010, p. 187). The analysis of art products and architecture indicates the influence of Sufism on arts during the Timurid. It was fostered by the Tiymūr’s interest in the arts, the presence of Sufis at schools of pious endowers (waqfīyahs), and the integration of Sufism into people’s lives (ʿAbbās-Nizhād Khurāsāni 2015; Zuhrahwand and Furūtan 2021, pp. 5, 9–15; Subtelny 1991, p. 56). |

| 19 | Few case studies are available at present (Shād-Ārām and Nāmwar 2021; Dawāzdah-Imāmī et al. 2015). |

| 20 | For the growing adoption of Sufi gatherings and their associated common activities, see (El Asri and Vuillemenot 2020, pp. 495–98). |

| 21 | Since particualry the second mystical tradition there has been an essential and strong corelation between sufism and shīʿism. Sayyid Ḥaydar Āmulī, the prominent theorian of the given field, believes a true Sufi is shīʿah and a true shīʿah is a Sufi (see Naṣr 1988, pp. 100–9). |

| 22 | Mawlānā Jalāl al-Dīn Muḥammad Ballkhī, known as Mawlawī or Rumī, was a Persian mystic and poet of the seventh century AH who has authored the remarkable poetical Mathnawī-i Maʿnawī. |

| 23 | Ḥāfiẓ was a Persian mystic and poet of the eighth century AH and his Dīwān is one of the greatest Iranian literary works. |

| 24 | Regarding teaching systems of Sufism in both traditions see Nādirī et al. (2021). |

| 25 | For a pathology of master/student relations, see Siyfī et al. (2016), pp. 42–43, and a review on the role of master on the journey towards perfection Hāshimī Sijzahī (2013). |

| 26 | Ismaʿīl Adīb Khwānsārī, one of the students of Jalāl al-Dīn Tāj Iṣfāhānī and Sayyid Raḥīm, is a geniune figure in this regard. |

| 27 | Sayyid Ḥusayn Ṭāhirzādah, Jalāl al-Dīn Tāj Iṣfāhānī, and Muḥammad Riḍā Shajarīyān, to name few. |

| 28 | A piece in minor-scale, using ʿAṭṭār’s poem beginning with Gum shudam dar khwud chunān kaz khwīsh nā-paydā shudam/Qatrahī būdam zih daryā gharqah dar daryā shudam [I was lost in myself as much as I turned invisible from myself/I was a drop from the sea which was drowned in the sea.] |

| 29 | For different poetic forms in Persian—especifically for lyric poetry—see, Yarshater (2019). |

| 30 | The synthesis of poetry and music is one of the most subtle vocal musics which is usually taught in superior vocal training courses, and it is the discerminating factor of distinguished vocalists. |

| 31 | For an explanation on the relation between meter and vocals, see Dihlawī (1997, pp. 127–45). |

References

- ʿAbbās-Nizhād Khurāsāni, Hādī. 2015. Barrasī-i ʿilal-i rawābiț-i șūfīyān bā zimāmdārān wa ḥukkām-i sīyāsī dar dawrah-yi īlkhānī wa taymūrī. Fașl-nāmah-yi Pazhūhishī-i Zabān wa Adab-i Fārsī 8: 271–96. [Google Scholar]

- ʿAbdī, Ḥusayn, and Sayyid Mahdī Zarqānī. 2017. Taḥlīl-i guftimānī-i rasālah-hā-yi raddīyyah bar tașawwuf dar ʿașr-i șafawī. Adabīyyāt-i ʿIrfānī 9: 119–44. [Google Scholar]

- Adīb, Shīrīn. 2006. Adīb Khwānsārī: Āwā-yi jāwīdān dar mūsīqī-i īrān. Iṣfahān: Muʾassisah-yi Āwā-yi Hunar wa Andīshah. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. 1957. Urkistir-i Gul-hā. Mūzīk-i Īrān 6: 18–27. [Google Scholar]

- Avery, Kenneth S. 2004. A Psychology of Early Sufi Samâ‘: Listening and Altered States. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bağçeci, Fulya Soylu, and Mücahit Özdemir. 2021. Divân-ı Kebîr’de yer alan rebap çalgısına yönelik metaforların hermeneutik açıdan incelenmesi. Rast Müzikoloji Dergisi 10: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barāzandahnīā, Riḍā. 2015. Jāmiʿah-shināsī-i mūsīqī-i īrān. Tihrān: Ārnā. [Google Scholar]

- Blum, Stephen. 2013. Foundations of musical knowledge in the Muslim world. In The Cambridge History of World Music. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 103–24. [Google Scholar]

- Dawāzdah-Imāmī, Mahdī, Qubād Kīyān-Mihr, and Saʿīd Bīnā-yi Muțlaq. 2015. Muțāliʿah-yi tathīr-i ʿamalī-i ʿirfān-i shīʿī bar hunar-i sunnatī, Muțāliʿah-yi muridī-i shikl-gīrī-i hunar-i khātam-i murrabbaʿ az qarn-i hashtum. Jāmiʿah-shināsī-i Hunar wa Adabyyāt 7: 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Dihlawī, Ghālib. 1997. Mūsīqī: Paywand-i shiʿr wa mūsīqī-i āwāzī. Hunar 34: 127–45. [Google Scholar]

- During, Jean. 2021. Música y éxtasis: La audición mística en la tradición sufí. Argentina: Editorial Yerrahi. [Google Scholar]

- El Asri, Farid, and Anne-Marie Vuillemenot. 2020. Le “World Sufism”: Quand le soufisme entre en scene. Social Compass 57: 493–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, Carl W., and Bruce B. Lawrence. 2002. Sufi Martyrs of Love: The Chishti Order in South Asia and Beyond. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Farhat, Hurmuz. 1990. The Dastgāh Concept in Persian Music. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fatḥī, Bihrūz. 2008. Waḍʿīyyat-i hunar dar īrān [3] taḥlīlī guzarā bar waḍʿīyyat-i mūsīqī. Mīyān-rishtahī, nashrīyyah-yi guzārish-hā-yi kārshināsī, 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Fayyāḍ, Muḥammad Riḍā. 2015. Tā bardamīdan-i gul-hā: Muṭāliʿah-yi jāmiʿah-shinākhtī-i mūsīqī dar īrān az sipīdah-dam-i tajaddud tā 1334 HS. Tihrān: Sūrah-yi Mihr. [Google Scholar]

- Gīlānī, Ādharnūsh, and Sayyid Ṣādiq Zamānī. 2021. Jāygāh-i mūsīqī wa samāʿ-i ʿārifānah nazd-i Suhrawardī. Metaphysik 13: 165–80. [Google Scholar]

- Gulistānah, Abu al-Ḥasan Ibn Muḥammad Amīn. 1956. Mujmal al-tawārīkh. Tihrān: Intishārāt-i Dānishgāh-i Tihrān. [Google Scholar]

- Güner, Burçin Bahadir. 2022. Processual Form in Sufi Dhikr Ritual. Musicologist 6: 110–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hāshimī Sijzahī, Abulfaḍl. 2013. Ustād wa naqsh-i ān dar sayr wa sulūk. Maʿrifat 22: 31–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ḥaydarkhānī, Ḥusayn. 1995. Samāʿ-i ʿārifān. Tihrān: Sanāī. [Google Scholar]

- Ḥusaynī Turbatī, Abū Ṭālib. 1963. Tazūkāt-i Tiymūrī. Tihrān: Kitābfurūshī-i Asadī. [Google Scholar]

- Jaʿfarīyān, Rasūl. 2019. Ṣafawīyyah dar ʿarșah-yi dīn, farhang, wa sīyāsat [2]. Tihrān: Pazhūhish-kadah-yi Ḥawzah wa Dānishgāh. [Google Scholar]

- Khaḍrāī, Bābak. 2012. Mabānī-i naẓarī-i mūsīqī dar dawrah-yi saljūqī dar mutūn-i qarn-i panjum tā haftum-i hijrī. Tārīkh wa Tamaddun-i Islāmī 8: 125–40. [Google Scholar]

- Khusrawī, Nasībah. 2018. Naqsh-i dīdgāh-hā-yi ʿirfānī dar shikl-gīrī-i ʿanāșur-i pāydārī dar zindigī-i ʿārfān-i saddih-hā-yi shishum wa haftum. Master’s thesis, University of Isfahan, Isfahan, Iran. Supervised by Ehsan Reisi. [Google Scholar]

- Khwushnām, Maḥmūd. 1959. ʿAwāmil-i ijtimāʿī-i inḥiṭāṭ-i mūsīqī dar īrān. Mūzīk-i Īrān 8: 21. [Google Scholar]

- Klotz, Sebastian. 2013. Perspectives on world music in the Enlightenment. In The Cambridge History of World Music. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 277–97. [Google Scholar]

- Kuehn, Sara. 2023. Contemporary Art and Sufi Aesthetics in European Contexts. Religions 14: 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewisohn, Jane. 2009. Gul-hā-yi āwāz wa mūsīqī-i īrānī: Dāwūd Pīrnīā wa āghāz-i barnāmah-yi Gul-hā. trans. Muḥammad Riḍā Pūr Jaʿfarī. Faṣlnāmah-yi Mūsīqī-i Māhūr 44: 109–25. [Google Scholar]

- Macit, Muḥsin. 2010. The Function of ghazels at urfa special night gatherings and musical assemblies. Milli Folklor 87: 84–93. [Google Scholar]

- Malikān, Majīd, and Kāẓim Muʾadhin. 2015. Sīyāsatgudhārī-i mūsīqī dar jumhūrī-i islāmī-i īrān. Nashrīyyah-yi Rasānah 26: 45–68. [Google Scholar]

- Manz, Beatrice Forbes. 1989. The Rise and Rule of Tamerlane. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Masīḥ-Far, Fātimah. 2013. Mūsīqī dar dawrah-yi șafawīyyah. Fașl-nāmah-yi Tārīkhpazhūhī, 199–218. [Google Scholar]

- Maythamī, Sayyid Ḥusayn. 2016. Mūsīqī dar dawrah-yi qājār. Nashrīyyah-yi Hunar-hā-yi Zībā 21: 63–68. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Lloyd Clifton. 1999. Music and Song in Persia. Surrey: Curzon. [Google Scholar]

- Miʿmārzādah, Muḥammad. 2007. Tașwīr wa tajassum-i ʿirfān dar hunar-hā-yi islāmī. Tihrān: Dānishgāh-i Al-Zahrā. [Google Scholar]

- Mirbagheri Fard, Sayyed Ali Asghar. 2012. ʿIrfān-i ʿamalī yā naẓarī yā sunnat-i awwal wa duwwum-i ʿirfānī. Pazhūhish-hā-yi Adab-i ʿIrfānī 6: 93–120. [Google Scholar]

- Muḥammadīyān, Fakhr al-Dīn, Sayyid Rasūl Mūsawī Ḥājī, and ʿĀbid Taqawī. 2018. Sayrī dar taḥawwulāt-i ijtimāʿī-i āīīn-i samāʿ wa mūsīqī-i ʿirfān-i īrān bā tawajjuh bih nigārah-hā-yi islāmī. Faṣlnāmah-yi ʿIrfān-i Islāmī 16: 51–69. [Google Scholar]

- Mușaffā, Akram. 2008. Barrasī-i nathr-i șūfīyānah az sadah-yi panjum tā qarn-i hashtum. Adyān waʿIrfān 5: 131–54. [Google Scholar]

- Muțlaq, Kāẓim, Ḥamīd Jawāhirīyān, and Mahdī ʿĀbidīnī. 2006. Hizār gul-khānah-yi āwāz: Muḥammad Riḍā Shajarīyān ustād-i āwāz-i īrān. Tihrān: Farāguft, Tawsiʿah-yi ʿIlm, Āfarīnah. [Google Scholar]

- Nādirī, ʿĀtifih, Muḥammad Ḥusayn Ḥaydarī, and Sayyed Ali Asghar Mirbagheri Fard. 2021. Bāzshināsī-i muallifah-hā-yi shāgird-parwarī dar ʿirfān-i islāmī bā takīd bar manish-i muʿalimī-i Junayd-i Baghdādī, Basțāmī, and Najm al-Dīn Kubrā. Tarbīat-i Islāmī 16: 7–33. [Google Scholar]

- Naṣr, Sayyid Ḥusayn. 1987. Islamic Art and Spirituality. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Naṣr, Sayyid Ḥusayn. 1988. Shiʿism and Sufism. In Shiʿism: Doctrines, Thought, and Spirituality. Albany: State University of New York Press, pp. 100–9. [Google Scholar]

- Nettl, Bruno, and Carol M. Babiracki. 1992. The Radif of Persian Music: Studies of Structure and Cultural Context in the Classical Music of Iran. Illinois: Elephant & Cat. [Google Scholar]

- Nikūī, Pūyā, and Riḍā Parwīz Zādah. 2020. Naqd wa tafsīr-hā-yi ʿirfān-girāyānah az mūsīqī-i īrānā wa barkhī az janbah-hā-yi bistar-i farhangī ijtimāʿī-i mūsīqī dar dahah-hā-yi sī wa chihil-i shamsī. Nashrīyah-yi Pazhūhish-hā-yi Īrānshināsī 10: 206–25. [Google Scholar]

- Omer, Spahić. 2014. From Mosques to Khanqahs: The Origins and Rise of Sufi Institutions. Kemanusiaan 21: 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Partaw, Amīn. 2020. Taḥlīl; hunar-i mūsīqī dar jumhūrī-i islāmī-i īrān: Nikāt wa taʾmullāt. Nashrīyyah-yi Dīdahbān-i Amnīyyat-i Millī, 37–42. [Google Scholar]

- Qayyūmī Bīdhindī, Mihrdād. 2010. Bāznigarī dar rābițah-yi mīyān-i hunar wa ʿirfān-i islāmī bar mabnā-yi shawāhid-i tārīkhī. Tārīkh wa Tammaddun-i Islāmī 6: 175–89. [Google Scholar]

- Qureshi, Regula Burckhardt. 2013. Sufism and the globalization of sacred music. In The Cambridge History of World Music. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 584–605. [Google Scholar]

- Riḍāī, Mahdī, Ḥaydar-ʿAlī Maymanah, and Rayḥānah-Sādāt Dārbūī. 2014. ʿIlal wa angīzah-hā-yi mushārikat-i ijtimāʿī-I șūfīyān bar asās-i mutūn-i nathr-i ʿirfānī-i sadah-yi panjum wa shishum. Pazhūhish-hā-yi Adab-i ʿIrfānī 8: 79–110. [Google Scholar]

- Ṣafarī, Saʿīd. 2018. Barrasī-i wa taḥlīl-i paywand-i shiʿr wa mūsīqī dar āwāz-i sunnatī bā takyah bar shașt āwāz az Iqbāl Ādhar, Tāhirzādah, Adīb Khawnsārī, Tāj Isfahanī, Banān, wa Muḥammad Riḍā Shajarīyān. Master’s thesis, University of Isfahan, Isfahan, Iran. Supervised by Ehsan Reisi. [Google Scholar]

- Safi, Omid. 2000. Bargaining with Baraka: Persian Sufism, “Mysticism,” and Pre-modern Politics. The Muslim World 90: 259–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ṣafwat, Dārūsh. 1982. ʿIrfān wa mūsīqī-i īrānī. Nashrīyah-yi Hud-Hud 4: 339–59. [Google Scholar]

- Shād-Ārām, ʿAli Riḍā, and Zahrā Nāmwar. 2021. Chīstī wa chirāī-i tathīr-i adabyyāt-i ʿirfānī bar nigārgarī-i īrānī (bā rūykard-i nishānah-shināsī). Pazhūhish-hā-yi Adab-i ʿIrfānī 15: 185–210. [Google Scholar]

- Sharify-Funk, Meena, William Roy Dickson, and Merin Shohbana Xavier. 2018. Heart or Heresy? The Historical Debate Over Sufism’s Place in Islam. In Contemporary Sufism: Piety, Politics, and Popular Culture. London: Routledge, pp. 35–61. [Google Scholar]

- Shikarābī, Ḥusayn. 2010. ʿIrfān wa tazāḥum-i andīshah wa ʿamal-i ijtimāʿī. Pazhūhish-hā-yi ʿIlm wa Dīn 1: 57–76. [Google Scholar]

- Siyfī, Nidā, Ḥasan Bulkhārī Quhī, and Mahdī Muḥammadzādah. 2016. Taʾmulī dar rābiṭah-yi ustād wa shāgirdī dar āmūzish-i hunar-hā bā taʾkīk bar niẓām-i sunnatī. Faṣl-nāmah-yi ʿilmī-pazhūhishī-i Nigarah, 33–46. [Google Scholar]

- Subtelny, Maria Eva. 1991. A Timurid Educational and Charitable Foundation: The Ikhlāṣiyya Complex of ʿAlī Shīr Navāʾī in 15th-Century Herat and Its Endowment. Journal of the American Oriental Society 111: 38–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Țabāțabāī, Sayyid Mahdī, and Milīkā Ḥājī-Shaʿbānīyān. 2019. Barrasī-i jāygāh-i pīshah-hā wa ḥiraf dar andīshah-yi ʿārifān wa sālikān-i musalmān tā pāyān-i qarn-i shishum. Muțāliʿāt-i ʿIrfānī 29: 145–72. [Google Scholar]

- Tājbakhsh, Ismāʿīl, and Saʿīd Murādī. 2023. Khirqah-pūshān-i darbarī: ʿīlal-i darbār-girāī-i șūfīyah az qarn-i shishum tā nuhum-i hijrī. Pazhūhish-nāmah-yi ʿIrfānī 15: 97–114. [Google Scholar]

- Tamīmdārī, Aḥmad. 1993. ʿIrfān wa adab dar ʿașr-i șafawī. Tihrān: Ḥikmat. [Google Scholar]

- Tarraqī, Bīzhan. 2010. Az pusht-i dīwār-hā-yi Khāṭirah: Panjāh sāl khāṭirah dar zamīnah-yi shiʿr wa mūsīqī az bīzhan tarraqī. Tihrān: Badraqah-yi Jāwīdān. [Google Scholar]

- Țāwūsī, Muḥammad ʿAlī, Maḥmūd Riḍā Isfandīyār, and Shahrām Pāzūkī. 2022. Nisbat-i tașawwuf bā farhang wa tammaddun-i jadīd dar īrān: Barrasī-i ārā-yi Ḥāj Mullā ʿAlī Nūr ʿAlī Shāh. Pazhūhish-hā-yi Tārīkhī 13: 61–76. [Google Scholar]

- Wāmiqī, Īraj. 1956. Taḥlīlī bar chigūnahgī-i mūsīqī-i īrān: Āyā mūsīqī-i īrān ghamangīz ast. Naqsh-i Jahān 2: 27. [Google Scholar]

- Yarshater, Ehsan. 2019. A History of Persian Literature Vol. II: Persian Lyric Poetry in the Classical Era, 800–1500: Ghazals, Panegyrics and Quatrains. Lindon: Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Zarrīkūb, ʿAbd al-Ḥusayn. 2002. Pilah pilah tā mulāqāt-i khudā. Tihrān: Nashr-i ʿIlmī. [Google Scholar]

- Zuhrahwand, Ḥāmid, and Manūchihr Furūtan. 2021. ʿIrfān-i islāmī wa ārāyih-hā-yi miʿmārī: Barrasī-i jāmiʿah-shinākhtī-i paywand-i ʿirfān-i islāmī wa hunar-hā-yi tazīnī-i miʿmārī-i īrān dar dawrah-yi taymūrī. Muțāliʿāt-i Muḥītī-I Haft-ḤIșār 3: 5–18. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).