A New Approach to the Spatialization of Religion: Changes in the Spatial Distribution of Religious Institutions in Debrecen (Hungary) between the Second Half of the Nineteenth Century and 2023

Abstract

1. Introduction

- It seeks to trace changes and explore the reasons behind them by looking at a period of more than 150 years;

- Building on the fact that Debrecen has/had played an important role in the life of several religions, it shows the interaction of the spatiality of different religions as well as religious institutions;

- In addition to churches, other institutions (educational and social) also constitute the subject for our research;

- The socialist period marked a major break in the organic development of religious institutions, followed by a new revival after 1990.

- What was the characteristic spatial structure of the different religious institutions and what changes can be observed between the mid-nineteenth century and the first two decades of the twenty-first century?

- What are the factors that influenced the spatial location of the religious institutions?

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

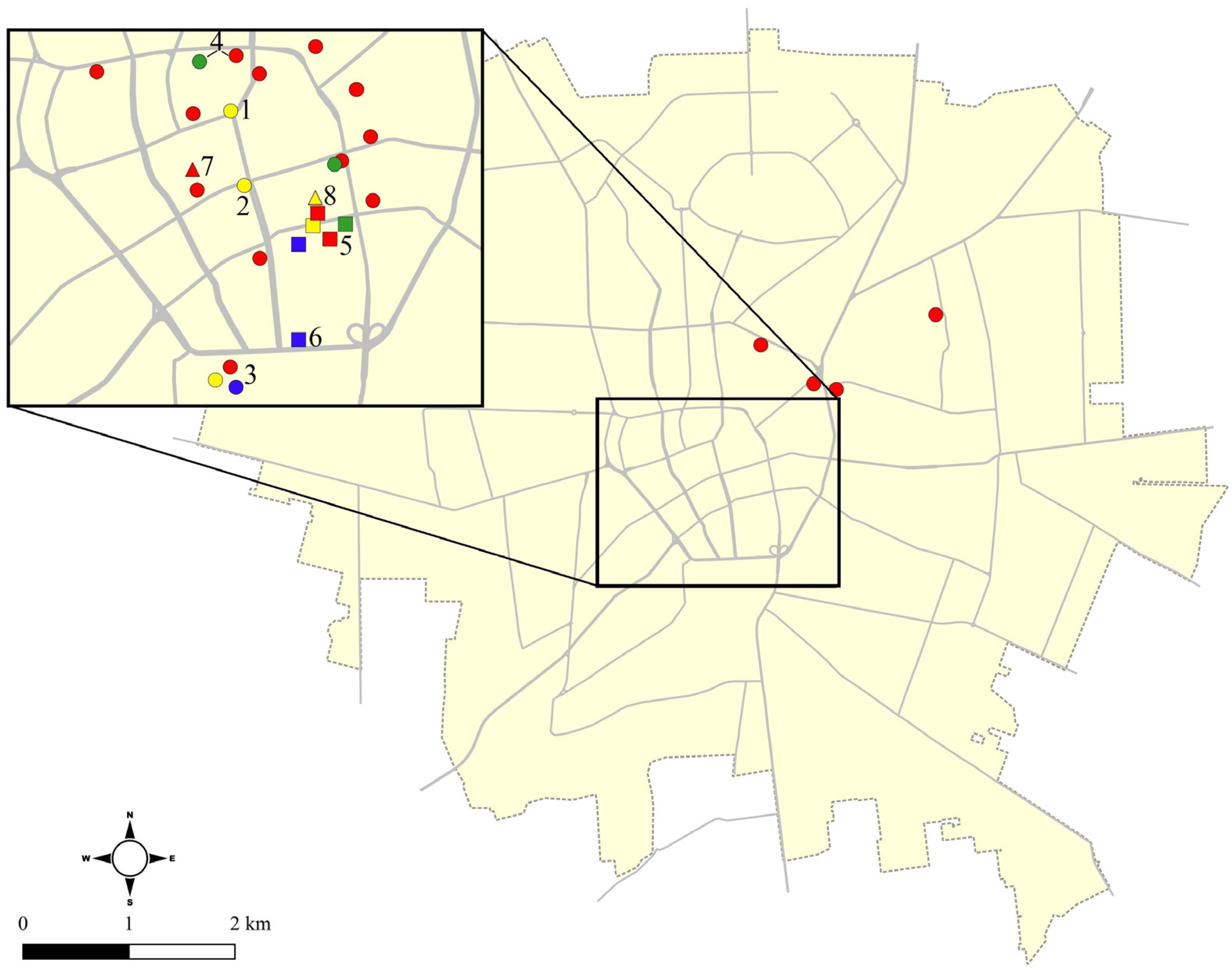

3.1. The Period before 1868/69

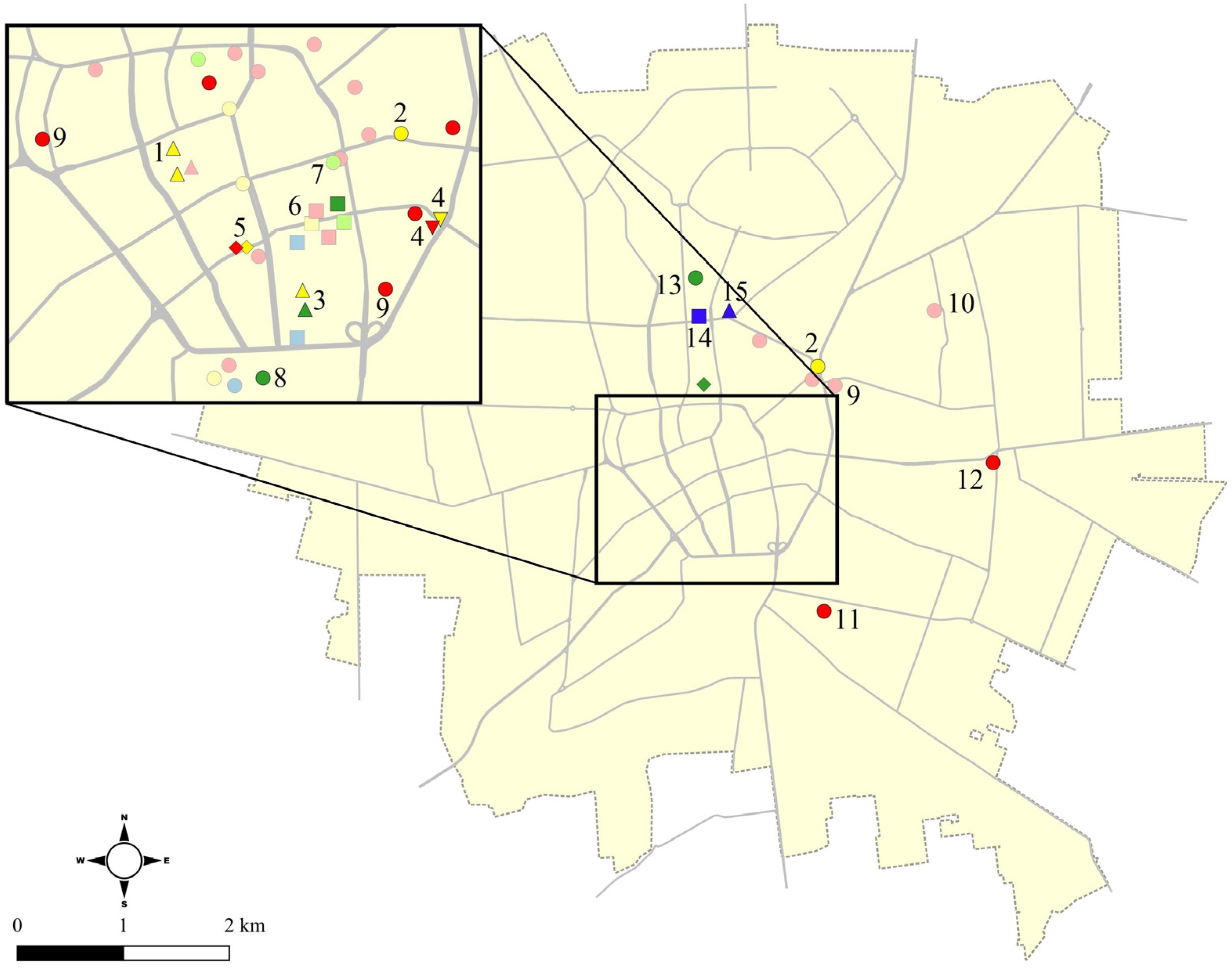

3.2. Between 1868/69 and the First World War

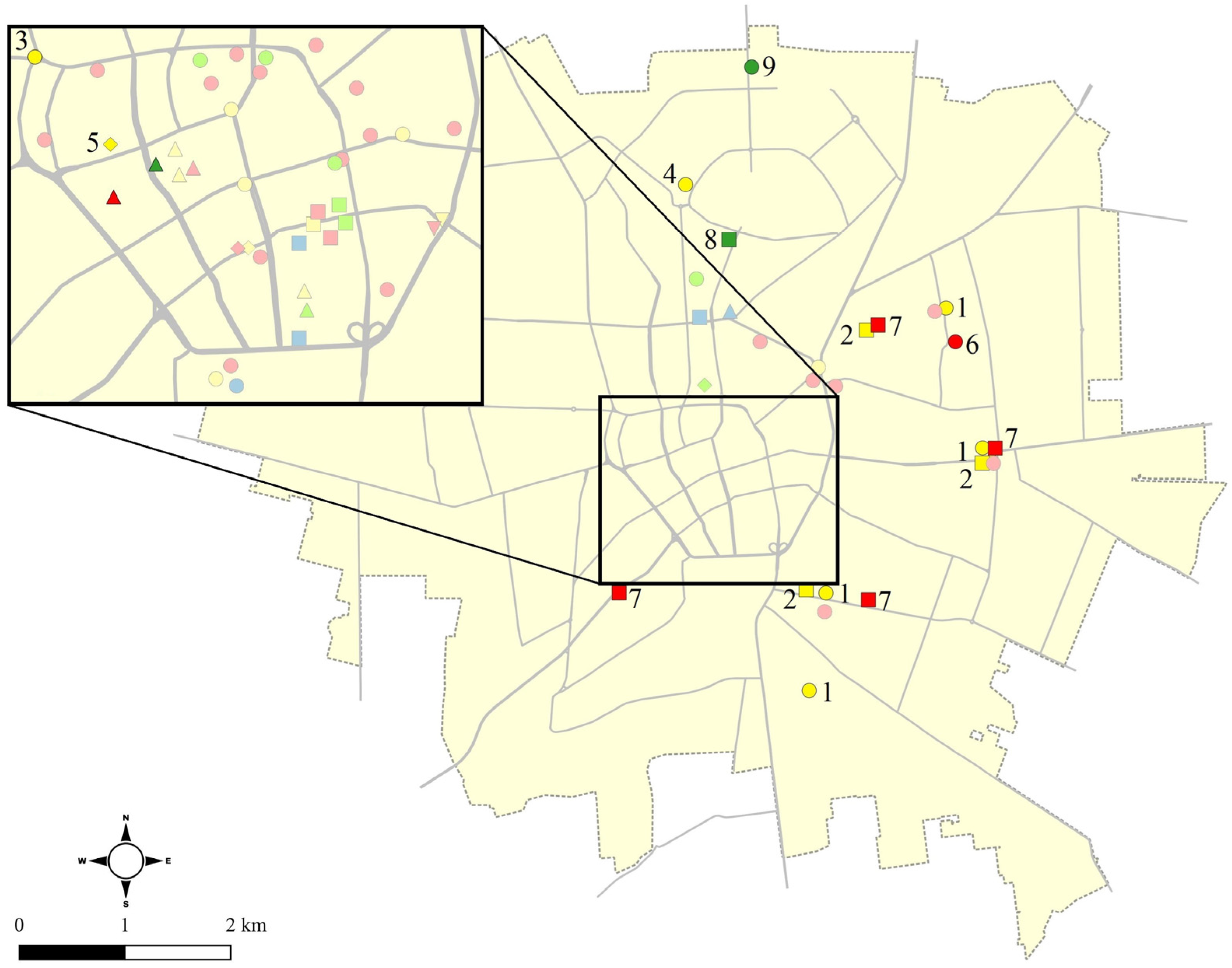

3.3. The Period between the Two World Wars

3.4. The Period between the Second World War and 1990

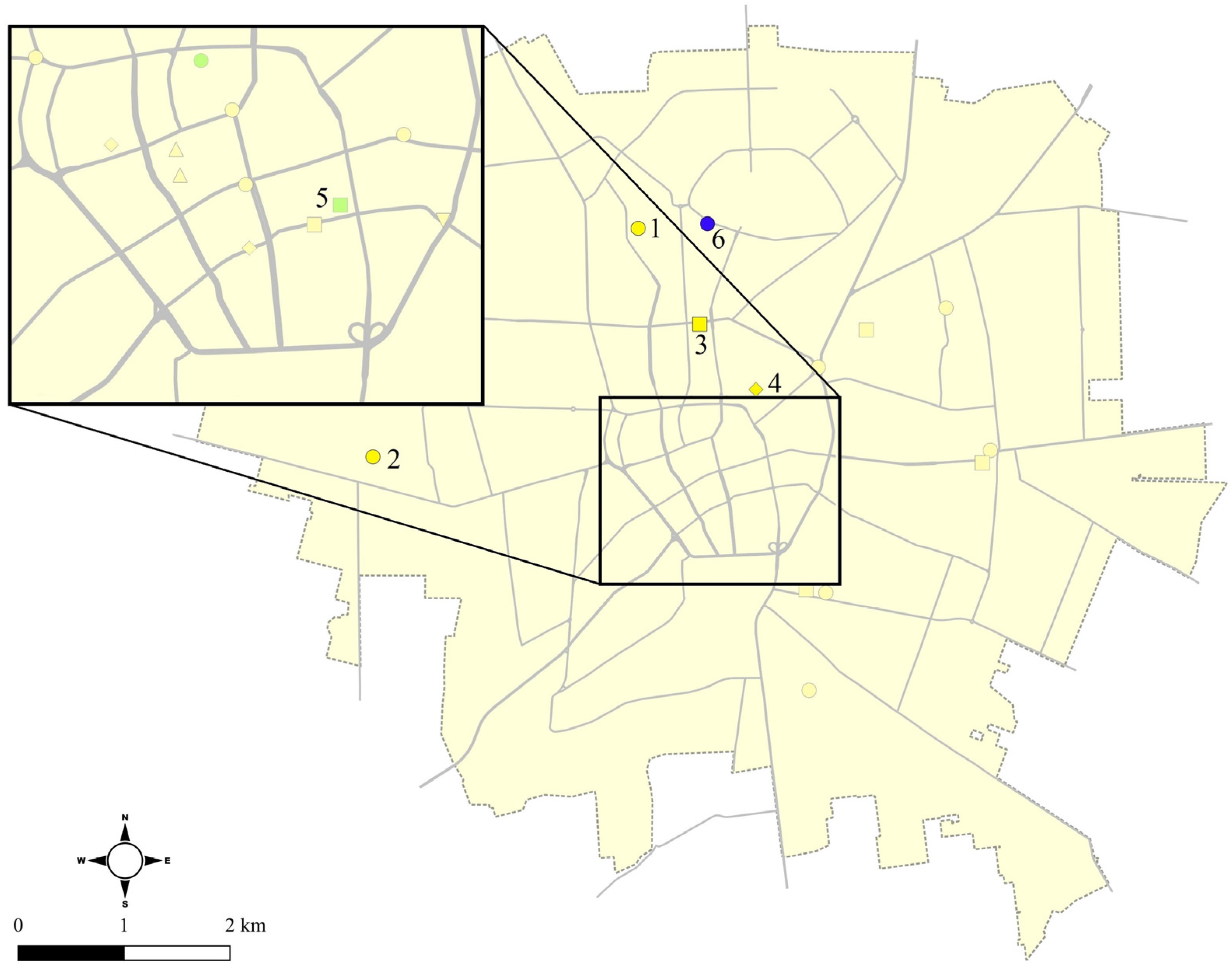

3.5. Post-Transition Period

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abulafia, Anna Sapir. 2004. Christians and Jews in the High Middle Ages: Christian Views of Jews. In The Jews of Europe in the Middle Ages (Tenth to Fifteenth Centuries): Proceedings of the International Symposium Held at Speyer, Germany, 20–25 October 2002. Edited by Christoph Cluse. Turnhout: Brepols Publisher, pp. 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ady, Lajos. 1931. Debrecen középiskolai oktatásügye [Secondary school education in Debrecen]. In Debrecen, szabad királyi város [Debrecen, Free Royal City]. Edited by Endre Csobán and Ferenc Csűrös. Budapest: Vármegyei Kiadó, pp. 412–19. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, Mohammed Ibraheem. 2022. Muslim-Jewish Harmony: A Politically-Contingent Reality. Religions 13: 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atikah, Rusli Siti, Ai Ling Tan, Alexander Trupp, Daniel Ka Leong Chong, Abdul Gani Arni, and Vijaya Malar. 2022. The emergence of a new religious travel segment: Umrah do it yourself travellers (DIY). GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites 40: 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballard, Paul. 2005. The Church at the Centre of the City. The Expository Times 116: 253–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendák, Gyula. 1940. Debrecen népoktatása [Public education in Debrecen]. In Debrecen szabad királyi város és Hajdú vármegye [Debrecen, Free Royal City and Hajdú County]. Edited by Endre Csobán. Budapest: Vármegyei Szociográfiák Kiadóhivatala, pp. 232–37. [Google Scholar]

- Benža, Mojmir, and Dagmar Kusendová, eds. 2011. Historický atlas Evanjelickej cirkvi augsburského vyznania na Slovensku—Historical Atlas of the Lutheran Church in Slovakia. Liptovský Mikuláš: Tranoscius. [Google Scholar]

- Bitušíková, Alexandra. 2022. Transformations of place, memory and identity through urban place names in Banská Bystrica, Slovakia. Hungarian Geographical Bulletin 71: 401–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boms, Nir Tuvia, and Hussein Aboubakr. 2022. Pan Arabism 2.0? The Struggle for a New Paradigm in the Middle East. Religions 13: 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burtenshaw, David, Michael Bateman, and Gregory John Ashworth. 2021. The European City: A Western Perspective. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, Thomas W. 2005. Stability and Change on the American Religious Landscape: A Centrographic Analysis of Major U.S. Religious Groups. Journal of Cultural Geography 22: 51–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donáth, Péter. 2009. A református tanító(nő)képzők államosításáról 1918–1919-ben és 1946–48-ban [On the nationalization of Reformed teacher training schools in 1918–1919 and 1946–1948]. In Állami oktatás–közoktatás–egyházi oktatás [State Education–Public Education–Church Education]. Edited by Zoltán Fürj. Debrecen: Kölcsey Ferenc Református Tanítóképző Főiskola, pp. 18–61. [Google Scholar]

- Drotár, Nikolett, and Gábor Kozma. 2021. A new element of tourism in North-eastern part of Hungary—Steps to attract Jewish pilgrims to Tokaj-Hegyalja region. Folia Geographica 63: 19–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers, Eckart, and Willem Floor. 1993. Urban change in Iran, 1920–1941. Iranian Studies 26: 251–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippinyi, Gábor, and József Papp. 1997. A városépítés története [The history of city building]. In Debrecen története 5. Tanulmányok Debrecen 1944. utáni történetéből [History of Debrecen 5. Studies from the History of Debrecen after 1944]. Edited by Géza Veres. Debrecen: Csokonai Kiadó, pp. 85–120. [Google Scholar]

- Form, William, and Joshua Dubrow. 2005. Downtown metropolitan churches: Ecological situation and response. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 44: 271–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, Graham. 1995. A Sense of Siege: The Geopolitics of Islam and The West. New York: Routledge, p. 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gergely, Jenő. 1985. A katolikus egyház Magyarországon, 1944–1971 [The Catholic Church in Hungary, 1944–1971]. Budapest: Kossuth Kiadó. [Google Scholar]

- Gergely, Jenő, József Kardos, and Rottler Ferenc. 1997. Az egyházak Magyarországon. Szent Istvántól napjainkig [Churches in Hungary. From Saint Stephen to the Present]. Budapest: Korona Kiadó. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez, González Carmen. 2015. Secondary Mosques in Madinat Qurtuba: Islamization and Suburban Development through Minor Religious Spaces. Papers from the Institute of Archaeology 25: 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadaway, C. Kirk. 1982. Church Growth (And Decline) in a Southern City. Review of Religious Research 23: 372–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halmos, Sándor. 2014. A debreceni zsidóság története 1840–2007 [The History of the Jews in Debrecen, 1840–2007]. Debrecen: Private Publisher. 397p. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, Thowayeb H., Ahmed Hassan Abdou, Mostafa A. Abdelmoaty, Mohamed Nor-El-Deen, and Amany E. Salem. 2022. The impact of religious tourists’ satisfaction with HAJJ services on their experience at the sacred place in Saudi Arabia. GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites 43: 1013–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havlíček, Tomás, Kamila Klingorová, and Lysák Jakub. 2017. Atlas náboženství Česka: The Atlas of Religions in Czechia. Praha: Karolinum. [Google Scholar]

- Hronček, Pavel, Bohuslava Gregorová, and Karol Weis. 2022. Medieval religious landscape and its use in religious tourism. GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites 41: 571–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutay, Ferenc. 1940. A római katolikus egyház [The Roman Catholic Church]. In Debrecen szabad királyi város és Hajdú vármegye [Debrecen, Free Royal City and Hajdú County]. Edited by Endre Csobán. Budapest: Vármegyei Szociográfiák Kiadóhivatala, pp. 201–5. [Google Scholar]

- Käsehage, Nina. 2022. No Country for Muslims? The Invention of an Islam Républicain in France and Its Impact on French Muslims. Religions 13: 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kheirabadi, Masoud. 2000. Iranian Cities: Formation and Development. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press. 132p. [Google Scholar]

- Knott, Kim. 2005. The Location of Religion: A Spatial Analysis. London and Oakville: Equinox. [Google Scholar]

- Kovács, Alajos. 1927. Debrecen lakosságának összetétele [The composition of the population of Debrecen]. Magyar Statisztikai Szemle 5: 373–93. [Google Scholar]

- Kozma, Gábor. 1996. A népesség számának, összetételének és területi megoszlásának változása Debrecenben 1939 és 1990 között [Changes in the number, composition and territorial distribution of the population in Debrecen between 1939 and 1990]. Tér és Társadalom 10: 123–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalopoulos, Stelios, Alireza Naghavi, and Giovanni Prarolo. 2018. Trade and Geography in the Spread of Islam. The Economic Journal 128: 3210–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J. Brian. 2017. Growing suburbs, relocating churches: The suburbanization of Protestant churches in the Chicago region, 1925–1990. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 56: 342–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, Sándor. 1940. The Hungarian Reformed Church. In Debrecen szabad királyi város és Hajdú vármegye [Debrecen, Free Royal City and Hajdú County]. Edited by Endre Csobán. Budapest: Vármegyei Szociográfiák Kiadóhivatala, pp. 195–201. [Google Scholar]

- Neumannová, Michaela. 2022. Smart districts: New phenomenon in sustainable urban development: Case study of Špitálka in Brno, Czech Republic. Folia Geographica 64: 27–48. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas, David. 2003. Urban Europe 1100–1700. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Papp, Gyula. 1940. A görög katolikus egyház [The Greek Catholic Church]. In Debrecen szabad királyi város és Hajdú vármegye [Debrecen, Free Royal City and Hajdú County]. Edited by Endre Csobán. Budapest: Vármegyei Szociográfiák Kiadóhivatala, pp. 205–6. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Chris. 2003. Sacred Worlds: An Introduction to Geography and Religion. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Pass, László. 1940. Az evangélikus egyházközség [The Evangelical Parish]. In Debrecen szabad királyi város és Hajdú vármegye [Debrecen, Free Royal City and Hajdú County]. Edited by Endre Csobán. Budapest: Vármegyei Szociográfiák Kiadóhivatala, pp. 206–8. [Google Scholar]

- Petőné Ecsedy, Ágnes. 2001. A Debreceni Diakonissza Intézet alapítása, felépítése és működése [The foundation, structure and operation of the Deaconess Institute in Debrecen}. In A Debreceni Diakonissza Intézet [The Deaconess Institute of Debrecen]. Edited by Lajosné Pető. Debrecen: A Diakonisszákért Alap Kiadó, pp. 33–106. [Google Scholar]

- Pianovszky, Károly. 1931. Debrecen sz. kir. város népoktatásának fejlődése [The development of public education in the free royal city of Debrecen]. In Debrecen, szabad királyi város [Debrecen, Free Royal City]. Edited by Endre Csobán and Ferenc Csűrös. Budapest: Vármegyei Kiadó, pp. 399–412. [Google Scholar]

- Poláčik, Štefan, and Viliam Judák, eds. 2005. Atlas Katolíckej cirkvi na Slovensku—Atlas of the Catholic Church in Slovakia. Bratislava: Rímskokatolícka cyrilometodská bohoslovecká fakulta UK. [Google Scholar]

- Ram, Moriel, and Meirav Aharon-Gutman. 2017. Strongholding the Synagogue to Stronghold the City: Urban-Religious Configurations in an Israeli Mixed-City. Tijdschrift voor economische en sociale geografie 108: 641–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rombai, Tibor. 2021. Ungvár nemzetiségi és vallási változásai 1914 és 1944 között, az Ungvári Kir. Görög Katolikus Líceum és Kántor-tanítóképző Intézet példáján [Ethnicity and religious changes in Uzhgorod between 1914 and 1944, on the example of the Royal Greek Catholic Lyceum and Cantor Teacher Training Institute in Uzhgorod]. Területi Statisztika 61: 661–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sági, Mirjam. 2022. The geographical scales of fear: Spatiality of emotions, emotional spatialities. Hungarian Geographical Bulletin 71: 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sápi, Lajos. 1972. Debrecen építés-és településtörténete [Construction and Settlement History of Debrecen]. Debrecen: Déri Múzeum Baráti Köre. [Google Scholar]

- Selod, Harris, and Yves Zenou. 2001. Location and education in South African cities under and after Apartheid. Journal of Urban Economics 49: 168–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sjoberg, Gideon. 1955. The pre-industrial city. American Journal of Sociology 60: 438–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slatter, Ruth. 2023. Geographical approaches to religion in the past. Geography Compass 17: e12682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stump, W. Roger. 2008. The Geography of Religion. Plymouth: Rowman and Littlefield Publisher. [Google Scholar]

- Szoboszlay, Sándor, ed. 1928. Hajdú vármegye és Debrecen sz. kir. város népoktatásügye [Public Education in Hajdú County and the Free Royal City of Debrecen]. Budapest: Királyi Magyar Egyetemi Nyomda. [Google Scholar]

- Sümeghy, Dávid, and Ádám Németh. 2022. A kulturális sokszínűség hatása a bizalomra Västra Götaland svédországi megyében, 2014 és 2018 között [Impact of cultural diversity on trust in Västra Götaland County, Sweden, 2014 and 2018]. Területi Statisztika 62: 81–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, Miklós. 1943. A debreceni utcai református elemi iskolák története 1692–1942 [History of Elementary Schools in Debrecen, 1692–1942]. Debrecen. [Google Scholar]

- Warf, Barney, and Morton Winsberg. 2010. Geographies of megachurches in the United States. Journal of Cultural Geography 27: 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, Pál, and Salamin Strasser. 1940. Az izraelita hitközségek [The Israelite Religious Communities]. In Debrecen szabad királyi város és Hajdú vármegye [Debrecen, Free Royal City and Hajdú County]. Edited by Endre Csobán. Budapest: Vármegyei Szociográfiák Kiadóhivatala, pp. 208–9. [Google Scholar]

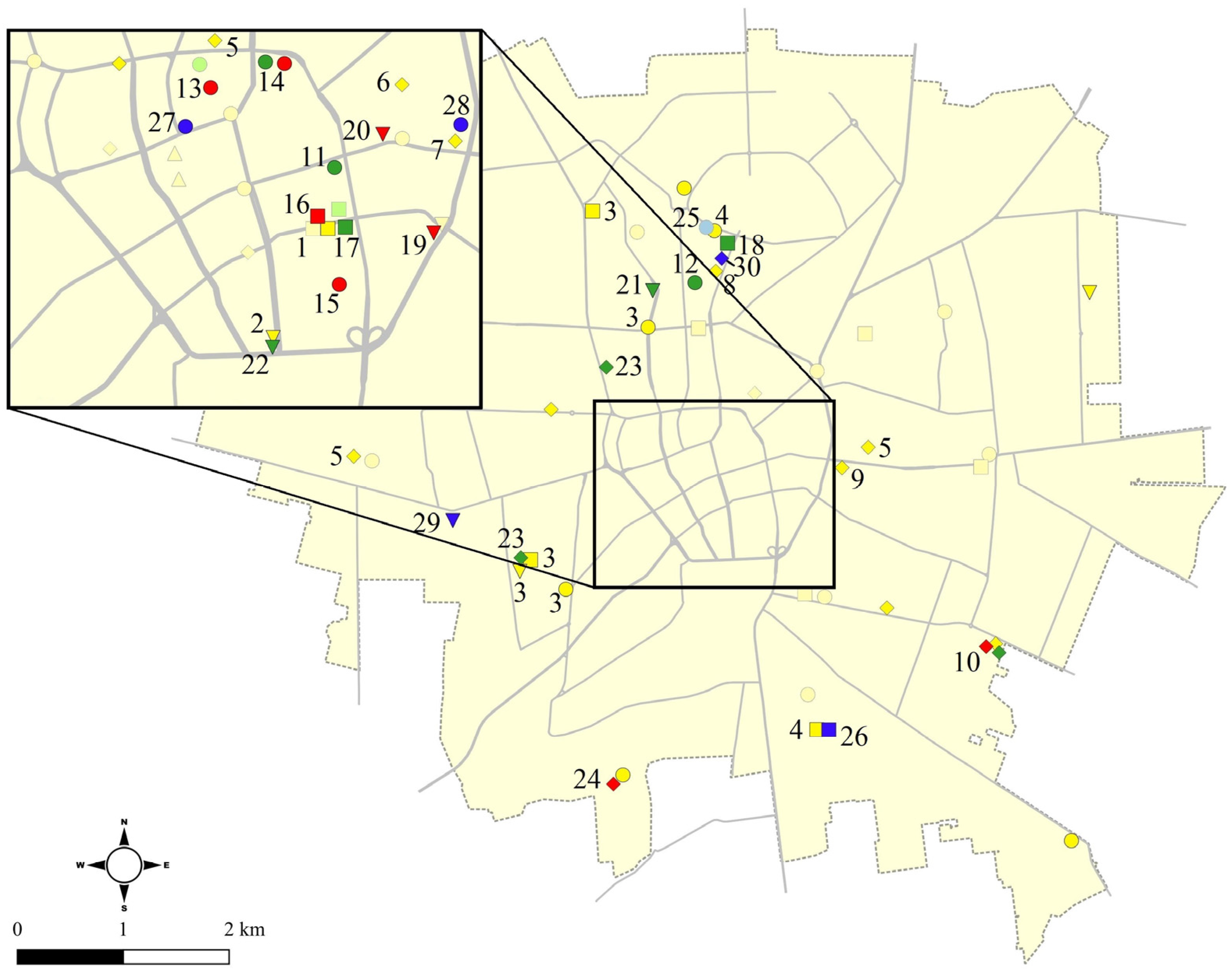

| Reformed Church | Roman Catholic Church | Israelite Religion | Greek Catholic Church | Other Churches | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| church, religious centre |  |  |  |  |  |

| kindergarten, primary education institution |  |  |  |  |  |

| secondary and tertiary education institution |  |  |  |  |  |

| social institution |  |  |  |  |  |

| 1869 | 1910 | 1941 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reformed | 37,239 | 63,318 | 82,580 |

| Roman Catholic | 5887 | 16,584 | 25,491 |

| Israelite | 1919 | 8406 | 9142 |

| Evangelical | 564 | 1274 | 1798 |

| Greek Catholic | 416 | 2655 | 6404 |

| Greek Orthodox | 84 | 386 | 194 |

| Unitarian | 2 | 54 | n.a. |

| Other | 0 | 52 | 324 |

| Church, Religious Centre | Kindergarten, Primary Education Institution | Secondary and Tertiary Education Institution | Social Institution | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1869 | 5 | 19 | 3 | 3 |

| First World War | 10 | 24 | 7 | 4 |

| Second World War | 21 | 29 | 10 | 5 |

| 1990 | 22 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| 2022 | 45 | 8 | 11 | 6 |

| 2001 | 2011 | |

|---|---|---|

| Reformed | 81,583 | 52,459 |

| Roman Catholic | 32,539 | 23,413 |

| Israelite | 231 | 165 |

| Evangelical | 1104 | 812 |

| Greek Catholic | 17,226 | 10,762 |

| Greek Orthodox | 186 | 154 |

| Baptist | 804 | 899 |

| Members of the Faith Church | n.a. | 238 |

| Other religions | 2165 | 3677 |

| not belonging to a religious congregation, did not answer | 75,196 | 118,741 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kozma, G.; Czimre, K.; Balcsók, I.; Pénzes, J.; Makhanov, K. A New Approach to the Spatialization of Religion: Changes in the Spatial Distribution of Religious Institutions in Debrecen (Hungary) between the Second Half of the Nineteenth Century and 2023. Religions 2023, 14, 1459. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14121459

Kozma G, Czimre K, Balcsók I, Pénzes J, Makhanov K. A New Approach to the Spatialization of Religion: Changes in the Spatial Distribution of Religious Institutions in Debrecen (Hungary) between the Second Half of the Nineteenth Century and 2023. Religions. 2023; 14(12):1459. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14121459

Chicago/Turabian StyleKozma, Gábor, Klára Czimre, István Balcsók, János Pénzes, and Kanat Makhanov. 2023. "A New Approach to the Spatialization of Religion: Changes in the Spatial Distribution of Religious Institutions in Debrecen (Hungary) between the Second Half of the Nineteenth Century and 2023" Religions 14, no. 12: 1459. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14121459

APA StyleKozma, G., Czimre, K., Balcsók, I., Pénzes, J., & Makhanov, K. (2023). A New Approach to the Spatialization of Religion: Changes in the Spatial Distribution of Religious Institutions in Debrecen (Hungary) between the Second Half of the Nineteenth Century and 2023. Religions, 14(12), 1459. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14121459