Abstract

Apropos of Spanish or Languedocien elements manifest in the late 13th-century Durandus Pontifical, this study explores the relationship between high medieval ritual and identity formation. It introduces the notion of liturgical use, an inclusive term for the body of customs that determined the way ceremonies were performed by lasting communities with a sense of belonging together. The primary challenge of comparing uses lies in selecting and systematizing the relevant information and interpreting the results. The authors argue that this challenge can be met by reducing the evidence to textual items and positions that lend themselves to large-scale comparative analysis in both time and space. As the main methodological contribution, they introduce the principle of mapping and drawing historical and cultural conclusions from their patterns. By summarizing a decade of careful research into thousands of sources accomplished by the team of the Usuarium database, they present four historical layers of medieval liturgical history, termed formative periods, and outline convergent geographical areas that they call liturgical landscapes. Since data on a lower level rarely correspond to smaller contiguous areas, they interpret the phenomenon called artificial diversity through medieval concepts of regionality and cultural transfer, formulating some thought experiments to understand the ways in which a Europe of uses once functioned.

Keywords:

liturgy; western church; Roman rite; Middle Ages; Early Modern Period; uses; variety; differentiation; William Durand; paradigms 1. The Durandus Case: Regional Features in the Roman Pontifical

The Aquinas of liturgics, William Durand (1230–1296), was one of the greatest summarizers of medieval culture, doing in the field of canon law and the sacred rites what his contemporary, Saint Thomas, did for dogmatics (). At the end of the 13th century, he compiled a service book for bishops () that became the first liturgical book type to achieve international acceptance () and, from the end of the 16th century, became the exclusive Roman Pontifical.1 Until then, and to some extent even afterwards, an untold number of local variants made up the religious, aesthetic, and socio-cultural phenomenon that we have come to call the Roman rite.

It was not only its indisputable virtues that contributed to the spread of Durand’s work. Pope John XXII (1249–1334) first made it the official book of the curia2 and, after best-selling print editions beginning in 1485, Pope Clement VIII made it obligatory for the whole Catholic Church within the Latin tradition in 1595 (). It would be reasonable to suppose that Durand codified the Roman liturgy in its narrowest sense as practiced within the city of Rome, the natural environment of the papal curia, and this already familiar material was then taken up and propagated by the papacy.3 A detailed analysis, however, does not confirm such an assumption. Undoubtedly, one can conclude a knowledge of the Roman practice from the compilation, but there are two further groups of sources and editorial principles that prevail. First, the version of Durand encompassed practically everything of the then-established Gallo-Germanic consensus of continental Europe, compared to Rome, which often followed a different path. Second, the version of Durand was remarkably ‘Spanish’. It contained several texts and gestures that counted as rather exotic in most of Europe; their use had been once confined to the Iberian peninsula and its immediate neighborhood (; ).

Neither Durand nor the above-listed popes were Spanish. The liturgical characteristics that appear to be Spanish at first sight, however, can equally be found on the other side of the Pyrenees and on the French coast of the Mediterranean. This is why we prefer to label such features as Ibero-Provençal. Durand indeed came from Béziers in Languedoc and was appointed bishop of Mende, another municipality in the south of France, even if, being a successful diplomat, he probably spent little time in his see. The landscape was not alien to John XXII either. He was born in Cahors, studied in Montpellier, became bishop of Fréjus (), and resided as pope in Avignon (). Thus, it is reasonable to suspect that both were driven by personal ties and a kind of local patriotism: Durand to combine Ibero-Provençal features with the mainstream, and Pope John to endow this amalgam with universal significance.

Still, it seems hardly credible that two Provençal agents would determine the course of the most respected ceremonies for the next 700 years by ‘Hispanizing’ them, regardless of whether they would eventually be performed in Scandinavia or the Balkans. Nor do we really understand their motivations. The ecclesiastical elite of the age, and especially the diplomats, formed a highly mobile, in our modern sense, cosmopolitan class (; ). They communicated with each other in Latin, were used to being at home anywhere since their university days, and tended to identify themselves with the centralizing, international ambitions of the medieval papacy (). A bishopric was often only a source of their income. Moreover, the links between identity and region, ethnicity, or language that seem natural today were not yet self-evident in the Middle Ages. Instead, loyalties to individual patrons, families, and institutions predominated ().

The ‘Hispanization’ of pontifical liturgies, therefore, is a fact but one that needs to be explained. In order to understand the phenomenon, it is necessary to define what liturgy and its local variants meant in medieval society, what tools we have or can develop to describe and interpret them, and, finally, what conclusions they offer about the geographical and historical patterns of early European identity formation.

2. Culture and Ritual

The religious life of a traditional society4 is based on the duet of orthodoxy and orthopraxy.5 By traditional, we mean societies characterized by a strong and lasting consensus on beliefs, values, attitudes, norms, customs, and institutions (; ). In such societies, the common codes of thought and behavior are not enforced from above by institutional ideology and power but produced and confirmed spontaneously from below by the populace itself in cooperation with its elite. Breaking the consensus is an anomaly that society tries to deter or punish, but the tendency to nonconformism itself is usually weak (). Beyond the fear of negative consequences, conformity has obvious moral and practical benefits (), and the strict framework still leaves a large margin for self-organization in smaller communities. It is these self-organizing sub-groups that primarily distinguish traditional societies from totalitarian regimes, which, partly out of nostalgia, try to create an enforced, artificial consensus. It has the opposite effect: Social solidarity fails, and self-organization withers.

The notion of orthodoxy requires less explanation since most religions define themselves doctrinally in the Euro-Atlantic orbit, and the outside world sees them primarily as worldviews too. This means that belonging to a particular religion implies the acceptance of a system of ideas with ethical consequences for personal conduct. In this context, rites are only externalities that reinforce or embellish the ideological core. Even today, however, and with admittedly doctrinal religions, this is an illusion. On the one hand, several denominations and religious communities either relativize their doctrine or turn a blind eye to the fact that many of their adherents only partially profess their teachings or accept their consequences (; ). Nevertheless, identity and retentive power remain; adherents continue to identify with their religion for some reason (; ). On the other hand, the apparent primacy of doctrine is illusory since the outside world associates religious adherence with specific ritual markers, such as church attendance, dietary rules, or distinctive dress, and even morally based behavior, such as regular prayer, having children above the average, almsgiving, or the prohibition to bear arms, acquire an added meaning of symbolic nature.

By orthopraxy, we mean such overall features of cult and lifestyle, acknowledged both internally and externally. The importance of orthopraxy in contemporary Europe is not negligible either, but it is even greater in traditional societies where orthodoxy is virtually beyond dispute. For them, ritual is the embodiment, the experiential side of religiosity; the very mode of manifestation in which members of the community meet and recognize each other. The rest of religious phenomena either find their ritual expression or remain the reserve of privileged classes: mystics or theologians.

The central role of ritual triggers two typical processes. One is that worship becomes a large-scale, summarizing fabric that integrates the intellectual and aesthetic achievements of a society. This is a sort of absorption effect, whereby cultural goods (e.g., technical craft, organizational skills, or artistic production) move towards the cult, creating a monument in the form of a compound set of symbols to the culture in question, in addition to ritual’s direct religious functions. It is only natural that such a process leads to the accumulation of cultural goods around prestigious ritual centers. As for European liturgy, the result is obvious if we walk through historic city centers, visit cathedrals, museums, and libraries, delve into the world of pre-classical music, or study the customs of peasant folklore.

The other process is reciprocal. To maintain consensus, it is essential to offer some freedom within the frames. It is like play itself as compared to the rules of a game or creativity in relation to generic constraints; the strict formal framework stimulates rather than hinders imagination and the exploitation of inherent possibilities. Thus, the richer and more elaborate the cult, the more it provides the opportunity to distinguish; not only for the cult community as a whole but also for smaller groups within it. This inverse process brings with it the centrifugal dispersion of cultural goods around the cult. While Europe and the Roman rite are one and the same in terms of the absorbing process (), the dispersing process highlights groups and sub-groups within Europe in the premodern context of identity formation. In what follows, we will examine these and offer some ways to understand them.

3. The Fabric of Liturgy

Do similarities and differences observed in service books and the rites contained by them behave in a systematic way? This is the basic question of comparative liturgics. Positions range between two extremes. Either they say that rites are all the same, as historians with only superficial liturgical expertise tend to think, or that there are as many variants as there are sources, which is a common view among philologists and musicians who study the field in depth6. There is truth in both perceptions. On the one hand, the substantial consistency that can be traced from the first detailed source of Western liturgy, the Rule of St Benedict (480–547), to the 21st century is impressive (). On the other hand, we have examples such as a medieval English visitation protocol in which a bishop reprimanded some monks for not using the same type of missal even at the side altars of the same abbey church ().

The problem is not unique. In almost every field, things can appear very similar or infinitely diverse, depending on how we define the perceptual range. The speech units that humans can pronounce are within a very narrow range of theoretically possible sounds (); in this respect, all human speech is similar. Nevertheless, no two people pronounce all sounds exactly alike, so when using exact physical measures, we would have to conclude that all human utterances are different. In reality, our perception identifies phonological domains around ideal core values and within them, it is able to identify the meaningful elements in the confusion of accidental differences (). Music, colors, and the perception of shapes, flavors, or tactile stimuli work in a similar way, and the taxonomies of living things or languages also prove reliable as factual classifications. What they all have in common is that a large percentage of the input information has to be filtered out as irrelevant and a narrower cluster decoded as meaningful. One part of the information to be filtered out is too general, similar to background noise while listening to a lecture, and another part of it is too specific like a slight speech impediment of the speaker (). Meaning is conveyed by an intermediate domain, which our mind reconstructs by filtering and classifying the sounds we hear.

With liturgical variants, this intermediate domain is called use. By use, we mean an exactly describable way of realizing all the ceremonies performed by a given ecclesiastical institution over a considerable historical period. Use can be safely deployed as a utility term since native informants explicitly refer to it (). According to a number of high medieval sources, cathedrals, monasteries, and centralized religious orders equally had their uses, i.e., the individual features of their celebrations were not random but formed a coherent script, expressing the identity of the community concerned.7 In principle, a use should behave as a comprehensive medium. A liturgical use would comprise, on the one hand, different types and periods of service books from the same institution and, on the other hand, the worship of further institutions subordinate to the main one, such as parishes within a diocese, priories dependent on an abbey, abbeys of a congregation, or houses of a religious order. Medieval cathedrals boasted about their prestigious past, and their representatives required their subjects to adapt to the customs of their superiors in authoritative documents. Religious orders also demanded that, wherever they were active, their members follow the uniform practice of the order.

This level of different book types, ages, and subordinate institutions lies figuratively below uses. But questions remain about the level above them as well. Institutions having control over uses are subsets of partly overlapping sets. Each diocese is part of both an archdiocesan province and a country, and these belong to further geographical, cultural, linguistic, ethnic, or political blocks. In addition, a dense network of water and land transport routes, mother institutions and their foundations, trade, dynastic, and ecclesiastical links weaved through medieval Europe even over long distances. All these raise the question of grouping and clustering uses.

The material seems to be slipping through the researcher’s fingers. Historically, sources from the same institution are not necessarily unchanging; sources of subordinate institutions do not always conform to their superiors; sources belonging to a political or ecclesiastical unit do not always resemble one another more than the rest; and when, at last, a link between liturgies can really be discerned, it does not always mirror any historical relationship between the carrying institutions (). The result, therefore, appears to be disappointing, but it is exactly its bewildering nature that offers the possibility of revealing patterns that would otherwise remain hidden.

The central role that liturgy played in medieval life vouchsafes that such patterns will not be insignificant. But before going any further, it is necessary to clarify through what sort of data we can grasp, describe, and compare liturgical divergence in the first place. The quest for hard liturgical facts is also essential because, until now, historians and librarians often favored pieces of information in service books that have little to do with worship itself. Such are certain saints of local significance, identifiable geographical and personal names, or other records, such as a historical entry in a calendar, an oath of allegiance, or an appended charter. The insight that liturgy as pure liturgy can also be described and linked to carrying institutions comes from musicological research (, ; ).8 Its extension beyond the realm of chants is only a recent enterprise, not yet sufficiently appreciated in academic circles.

4. Textual Approach

Liturgy consists of memorable elements belonging to different sensory areas that some theoreticians call mnemes or memes (; ). For the sake of transparency, we will group them into three categories: texts, melodies, and ceremonial.

Texts denote the items that build up the spoken material of the celebration in an orderly succession. An item is an indivisible unit of unchangeable text in a fixed genre. It is the genre that determines the manner of performance and the position of the item within the overall structure. As a mere text, a prayer, chant, or lection may be identical to a verse of the Bible, but linked to a genre, it has inherent properties of its own. It is common for the actual meaning of a text to be subordinate to the additional meaning derived from its generic affiliation. This modification or expansion in meaning is analogous to when a sentence is taken from its original context to be used as the motto of another work ().

Melodies are, in the broadest sense, the manner in which texts come to life. Acoustically, medieval liturgy always distinguishes the utterance of a text from everyday prosaic speech, thus even a quiet rendering counts as musical. A range of transitions can be defined, arching from the simplest recitatives to unique and intricate combinations of words and melodies that can be justly regarded as works of art in the modern sense of the term.

Ceremonial encompasses the full spectrum of non-verbal aspects. Everything connected to liturgical orchestration—roles, space, material environment, such as vestments and furniture, movements, and gestures—rank in this category.

Though in historical reality, these elements were inseparable, we know them mainly from written sources. This has the inevitable consequence that texts predominate in the evidence that can be studied. Only a subset of the sources containing texts contains musical notation, too, and only some of these can be reconstructed and actually sung today; neumatic notation without staves was only useful as a memory aid for those who already knew the repertoire. Even fewer are the sources that record ceremonial details, and their testimony is necessarily incomplete; at most, they can be supplemented by pictorial information (; , ). A further difficulty arises from the fact that the amount of information recorded by contemporaries is usually inversely proportional to its importance. In continuous practice, it is the regular and widely practiced that is superfluous to mention, and it is precisely the exceptional that needs explanation. All this indicates sufficiently that, compared with the reality under study, the historian is faced with a heterogeneous and disproportionately documented body of memories.

An analysis of divergence can only rest on existing information. However, even existing information needs to be filtered and classified in order to arrive at meaningful results. To use examples from already working taxonomies: in sorting animal species, obvious features may prove unimportant, such as whether an organism lives in water or if it flies; its color, the pattern of its fur, scales, and feathers; a carnivorous or herbivorous diet, while less conspicuous characteristics, for example, vertebrae, mammary glands, or rumination, are definitive. In comparative linguistics, those who attempt to prove genetic relationships based on similar-sounding words also fail notoriously.

Accordingly, comparative liturgical analysis must focus on data which are persistent and characteristic, available in sufficient quantity, and proportionate both spatially and temporally. Here, too, the methodological principle of the intermediary range is of great help. Among the carrying institutions, it is the cathedrals that are sufficiently, but not yet too densely, located and whose practices, at least on average, are well documented. Studying fewer locations would be superficial, while studying more would be over-detailed and yield disproportionate results due to the uneven geographical and historical coverage of the extant sources. European cathedrals, however, enable us to construct a typological grid which, while not covering all the details, may reliably contextualize newly emerging data (). To return to the example of zoology, no matter how many unknown species we discover, they will likely fit into the already known system.

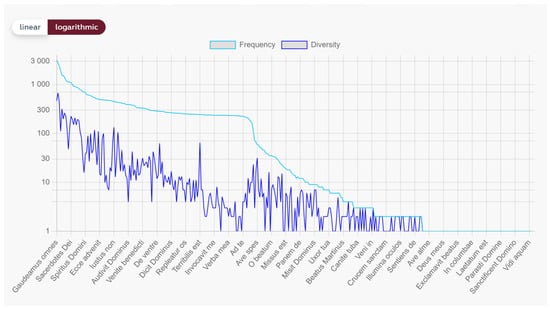

As for the actual data, the intermediary range consists of liturgical items, especially those known as propers: texts changing in recurring cycles within a specific rite. These can be examined from two perspectives: that of the stock and the structure. The stock of liturgical items acts as a kind of vocabulary for a particular use. Each use has a rich but not infinite repertoire: the total of the items with which it is familiar. It is important to note that the Middle Ages was still a primarily oral culture (; ); stocks of items were preserved in human memory and handed down from generation to generation through community consciousness. For Europe as a whole, liturgical stocks can be represented as interrelated clusters of various dimensions. A large number of items belong to the common heritage and are used everywhere; some are rather widespread yet not ubiquitous, others even more restricted; some appear in scattered patches, some in isolated regions, and some solitarily. Obviously, it is again the intermediate range that gains the utmost significance: items that are neither universal nor entirely unique (Figure 1).9

Figure 1.

Graphs displaying the frequency and diversity of introit chants on a logarithmic chart (usuarium.elte.hu/texts/intr/chart).

5. Historical Comparative Analysis

Items are embedded in structures. Such a structure can be a single ritual but also a liturgical day or the annual cycle as a whole. Meaningful structures made up of items can be identified not only horizontally, according to the temporal progress or timeline of the rite, but also vertically, on the basis of analogous places in parallel rites. Thus, for instance, the Gospel of the First Sunday of Advent fits into the mass of the day on the one hand and into the annual stock of readings on the other. It is both related to the neighboring chants and prayers of the same mass and to the Gospels of other masses. The structure, namely the selection and order of items, may be characteristic even if the items in themselves are not. If a use appropriates otherwise well-known items in a specific arrangement, its stock will not prove a marker and a basis of comparison, but the structure will.10

To understand structural features, we must clarify the nature of the large forms in which the items fit. Christian rituals can be divided into three main groups on the basis of their content and typical carrying books: (1) the mass (), (2) the divine office (; ; ), (3) and the rest.11 By mass, the eucharistic sacrifice is meant in the technical sense of the set of texts, melodies, and gestures closely associated with it. The divine office covers parallel sets linked to the regular prayer worship seven times every day. The loose category of the rest primarily contains processional or dramatic-mimetic rites, sacraments, sacramentals, and blessings administered by ordinary priests or bishops. Their format and significance may widely differ; the procession of flowers on Palm Sunday, the washing of feet on Maundy Thursday, baptism, burial, or the dedication of churches all belong to this category.

In a strictly structural sense, the three groups are only two. What the mass and the office have in common is that they both belong to the superstructure of the annual cycle, that their fixed structure is intact from local variation, and that their corpora of texts combine unchanging (ordinary) and changing items (propers). The other rites are not necessarily dependent on the liturgical year. Their structure is loose and varies from one locality to another, and their textual material is closed, i.e., they entirely consist of propers. Practically, the two latter statements follow from the first one since it is only possible to speak about a position in the annual cycle or to distinguish between changing and unchanging parts if the same type of ritual is periodically repeated within the framework of a superstructure.12

This implies that rites with a hard structure can be described systematically and are suitable for statistical analysis. As varying items fit in unvarying structures, we can construct research tools capable of handling big data sets that enable comparison both on the basis of an entry’s position in the structure or its significance in the corpus of the corresponding genre. Once the optimal method has been established, the challenge remains to select the relevant source material and record it in an accurate and consistent way. A more complex approach is required for rites with a soft structure. With them, the system is not predictable, but it emerges from the process of comparison. By superimposing manifold versions of the same type of ritual, the researcher gradually recognizes the organizing principles that provide an opportunity to process and compare the bewilderingly heterogeneous material according to retrievable attributes.

To scholars of religions, such a methodology may seem strange or even alienating. Indeed, our subject, religious ritual with its written sources, is a sublime field full of awe and inspiration (; , ; ; ). Our questions are directed towards an equally sublime field: past European identities. However, the bridge between the two seems to be a cold, technical activity: the recording and organizing of text incipits. This, however, is a false impression. Not only because there is life behind the data, just as a telephone directory, a museum inventory, or a library catalogue represents persons, artworks, and literature, but also because analytical experience shows that mechanical comparison by itself rarely yields significant results.

Liturgical rites are not the outcome of spontaneous evolution but the product of deliberate human creativity: artefacts in a certain sense, and that is why they often escape systematizing effort. Despite certain analogies, rituals can never be grasped with the consistency of natural phenomena; the human factor will always interfere. However, on a larger scale, this human factor is determined by its geographical and historical situation. The spread of a style, a motif, or a technique, too, allows for description within spatial and temporal limits, identifying cultures that apply it and those that do not. Liturgical memes behave in the same way. Although their understanding and systematization cannot work without the analysis of large amounts of data, the actual result is not a map or a chart but a capture of the creative process that produced and shaped specific uses and ceremonies. Ultimately, such insights can only be presented through narrative means.

Studying and understanding each rite on the basis of a large sample with the help of both historical comparative analysis and intuition is a lifelong research project, impossible to summarize in a methodological essay.13 Therefore, we shall turn to the conclusions we have been able to draw on the history and geography of uses after a number of case studies.

6. Formative Periods

It must be said in advance that although a liturgical use does have a character, this character comes from an ex-post attribution. The elements are international, and it would be presumptuous to infer any national, regional, or local character from a single text or gesture. It is still popular today to associate certain liturgical features with ethnic characters and speak about Roman austerity, Hispanic imagination, Celtic mysticism, or Germanic constraint (), but an in-depth analysis tends to refute such concepts. If an item or arrangement appears to be Polish or English, it is not because the respective people’s spirit has given rise to just such a liturgy but because—due to historical contingencies and individual initiative—Poles and Englishmen widely followed this very solution for a long period, and it took root over time. As in many other cases, the arbitrary sign was not predestined by intrinsic properties to carry a particular meaning, but it was imbued with that meaning by consistent use in specific contexts.

A use is created in history, but it is difficult to grasp its origin. Even the youngest institutions with distinct liturgical traditions are no later than the 13th century, while the source material is especially scarce and disproportionate before that time. The situation is not much better if we have confidence in the sporadic, early remains. For the Latin West, the first reliable service books have survived from the seventh and eighth centuries (). By then, liturgical life in much of Europe had already been going on since late antiquity. Their state at birth, accordingly, mostly remains obscure.14

In return, great relief is provided by the essentially conservative nature of rituals. Although a liturgy is bound to be born at some point and is then in a malleable state, it soon solidifies and, from then on, tends to stiffen. The liturgy is a hotbed of survival symptoms (); it can preserve dead languages as sacred languages, use out-of-fashion garments as ceremonial attire, and valorize outmoded techniques in ceremonial context (e.g., candlelight, manuscript reproduction). In sum, the conservative present of the liturgy suggests a past when all this was taken for granted.

Texts and their arrangements are not survivals in this sense, so they only imply an age as a terminus post quem. The liturgical use of a literary text in a definitive structure is usually much later than the composition of either the text or the structure. Nevertheless, by grouping the phenomena, we obtain geographical patterns that often correspond to the political-cultural map of an actual historical period.15 We call the situation in which a liturgical phenomenon took on its enduring shape its formative period. Even if we cannot date the phenomenon by other means, the dissemination of its variants may shed light on the age in which it was designed and spread (). There may be several such formative periods. Ceremonies and certain groups of ceremonies evolve in different periods, and hence, they establish historical layers. Once consolidated, a layer does not change significantly, but the maps drawn by its variation may differ from the maps of other layers according to their formative periods.

By and large, we can distinguish four such historical layers. (1) The first is the Roman layer, the common basis for most of the Latin West. Its formative period was the 7th and 8th centuries, when the mature urban liturgy of Rome spread beyond the Alps, first on private initiative and then by the decision of the Carolingian rulers (; ). (2) The second is the Frankish layer. It can be recognized by the fact that its characteristics are relatively uncommon in Italy but are simultaneously characteristic of the territories of modern Belgium, north-east France, and south-west Germany, i.e., the Romanized provinces of Europe and—beyond the Rhine—the homeland of the Franks, Austrasia. Here, the formative period was the age of Charlemagne and Louis the Pious when their ecclesiastical intelligentsia codified and enhanced the liturgical order based on Roman foundations, sometimes under the influence of divergence or recent initiatives experienced in contemporary Rome or genuine Roman documents (). (3) The third layer could be aptly called Romano-Germanic. Its formative period was the Ottonian culture of the 10th century, marked by German innovation, especially in pontifical and processional rites (, ). Its characteristic feature is an east-west frontier along the Rhine and the Alps, dividing Europe into a western (French-like) and an eastern (German-like) half (Figure 2). (4) Finally, newly founded or reorganized churches define the fourth layer between the 11th and 13th centuries. Here, there was no single formative period; new local uses were born in parallel with the church organization of the newly converted peoples in Eastern Europe, Scandinavia, and the Baltics, either immediately and centrally, or with some delay and with inner divisions, depending on the political and cultural situation. In Hungary, for instance, the establishment of the national use seems to date back to the time of King St Stephen I, the founder of the state (), while in Prague the mainstream tradition is only evident from the end of the 13th century (). The traits that distinguish the reorganized churches of England, Spain, or Saxony can also be traced to the 11th century.

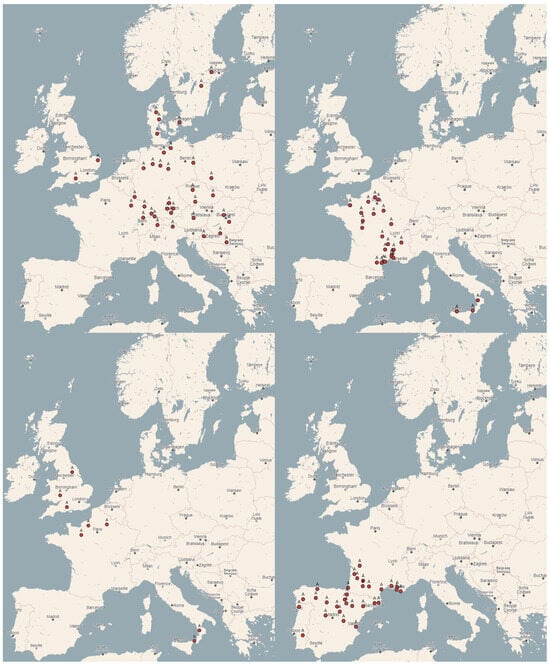

Figure 2.

The typical East-West divide, marked by the spring Ember Saturday canticles Benedictus es Domine Deus (CI h01912) with A and Benedictus es in firmamento caeli (CI g02022) with B (usuarium.elte.hu/l/79aa).

7. Liturgical Landscapes

A first orientation is best facilitated by the situation that emerged during the Romano-Germanic formative period from the mid-10th century and solidified by the end of the 11th century. This was the time when the great liturgical landscapes of Europe were outlined, themselves providing a sort of intermediary range in terms of geography. Their characteristics are no longer as general as those of the Roman and Frankish layers, but they are not yet as specific as the peculiarities of the new churches. In this sense, we can speak of four liturgical landscapes with a broad and complex transitional zone between them. The landscapes were given names that are reminiscent of the historical area but do not correspond to actual ecclesiastical or political formations.

(1) The largest landscape lies east of the Rhine and north of the Alps. It includes the Holy Roman Empire and its marches, as well as the new churches that were established in its eastern and northern neighborhoods. Since the latter were originally part of the imperial church organization or at least areas of its missionary activity (), we will call the landscape collectively Germanic. (2) The western part, in keeping with its longer and varied history, is less uniform. Its core consists of the central and northeastern regions of France, which we term the Gallic landscape. (3) Normandy, however, together with the British Isles, belongs to the Anglo-Norman landscape. It partly extended to Norway and Sweden as well, influenced by the missions and the ecclesiastical hierarchy of the English (), and Sicily with Calabria and Apulia, ruled in their formative liturgical period by Norman princes (; ). (4) The South of France, as has been said in the problem statement, shares its features with the Iberian Peninsula. This is the territory that we call the Ibero-Provençal landscape (Figure 3). (5) The transitional zone stretches along a line drawn by the river Rhine and the mountain ranges of the Alps and the Apennines. In the North, it is the Netherlands and Lorraine that are located here. Gallic and Germanic traits characterize the region, with a predominance of the former. In the South, historical Burgundy, present-day Switzerland, Italy, and the Latin churches of the Adriatic coast belong to the transitional zone (). Here, too, Gallic and Germanic elements are mixed, but the latter prevail, and the Alpine and Italianic uses often have some common Mediterranean flavor, which partly links them to the Ibero-Provençal landscape.

Figure 3.

From left to right, top to bottom: A Germanic pattern: the occurrences of the hymn Rex sanctorum angelorum (CI a00176) on Holy Saturday (usuarium.elte.hu/l/f72f). A Gallic pattern: Trinity masses on the last Sunday before Advent, signalled by the collect Omnipotens … qui dedisti famulis tuis (CO 3920) (usuarium.elte.hu/l/0783). An Anglo-Norman pattern: the occurrences of the responsory Dominus Iesus (CI 600630) in the procession of Palm Sunday (usuarium.elte.hu/l/29a2). An Ibero-Provençal pattern: the occurrences of the introit Domine dilexi (CI g02160) on the 2nd Sunday of Lent (usuarium.elte.hu/l/a5bd).

Within the landscapes, attempts at delimiting smaller but contiguous groups of uses are usually futile. Relationships can truly be detected, but they do not conform to regions. Indeed, the main reason to call landscapes landscapes is their resemblance to the natural environment untouched by human intervention. There are no exceptions to the landscape character. Within landscapes, however, a lower level of liturgical characteristics emerges that we prefer to label artificial diversity. This implies that the amount of divergence is greater than we would expect from the spontaneous variation of available ritual elements. Variation does not come about by itself as a result of natural, dialect-like evolution. Instead, it was someone at some point in history who deliberately worked on differentiation.16 Not only do neighboring uses not coalesce into regions or sub-regions within a landscape, but they are often even more distinct from one another than from their spatially distant relatives. Individual communities are always loyal to the landscape, but, on a lower level, they typically stand isolated from their immediate environment.

This fact points to a fundamental difference between the medieval perception of space and our own. Today’s man conceives of space in territorial terms, in accordance with administrative systems; space is continuous, and territories are related to each other in a set-subset relationship. This is how a continent, a federation, a state, a county, a district, and a municipality are related. The basis of this topography is that the whole world is subject to human domination. It is conquered, domesticated, familiar, and owned by particular masters.

In contrast, medieval minds were less informed by the experience of homogeneous and contiguous dominions. For them, the natural world befitted a dichotomy of chaos and cosmos (; ; ; ; ). It was, in essence, an unknown and dangerous wilderness of impenetrable swamps and forests from which the spaces of human civilization had to be carved (; ). Out of the agricultural sites more or less taken from nature, settlements with churches, and especially walled cities with cathedrals at their center, rise up in an insular manner. This concept of space is resolutely urban. It is useful to remember here that the bucolic mood opposing urbanity to the countryside and longing for a peasant lifestyle is only a counter-effect of congested metropolitan areas, even if it recurs over history (; ). In traditional societies, the religious prestige of the city and the urban way of life typically outrank those of the countryside. The city is also a cultic center, while the countryside is, at best, a sphere of its radiation (; ). One city is, therefore, more closely linked to another city than to the surrounding countryside, and space appears as a network of points and their connecting lines stretched over the distances in between.

Some cities in this network are more closely related than others, but this does not necessarily depend on geographical proximity. In premodern Europe, it was more difficult to move goods than people, and physical presence was a prerequisite for controlling affairs—exercising power and exerting intellectual or spiritual influence. As a result, the members of medieval elites partly led an itinerant life: the secular between their castles and palaces, the ecclesiastical between cathedrals, monasteries, and universities (). They simply passed through the lands and settlements that were indifferent to them, such as inter-city rail services do today, but settled permanently where they felt at home. Similarly discontiguous were the estates in relation to the landowner () or the monastic foundations in relation to the motherhouse. Such spatial models sufficiently explain why liturgical coincidences, when they exist at all, may not connect bordering areas but relatively distant and isolated points. Most connections within a landscape are like those between a mother city and its colonies.

This also explains why rural uses are not always up to par with urban ones. In theory, they should be obliged to conform to the diocese, but the use in its purest form is only available in the cathedral. Unreliable, mixed, flawed, and undemanding versions of service books are overrepresented in countryside parishes, and because books are expensive and difficult to produce, they are not easily discarded (). It is like a family banishing inferior but still functional household items from its flat in the city to the holiday home.

8. Artificial Diversity

Still, there are a few areas with evidence for regional coherence of uses within a landscape (). In Norway and Poland, some service books from the 16th century refer to a national custom.17 In England and Italy, the uses of Sarum (Salisbury) () and Rome gradually became national—at least that is what the number of their surviving sources and the relative lack of rival options suggest (). These, however, are late medieval or early modern developments which cannot be applied to previous centuries. The Hungarian Kingdom seems to be exceptional in that its uses have rested on a common national foundation from the outset; nowhere else has such a degree of similarity been achieved over such a large area and over such a long period.

The trend towards liturgical nationalization is noteworthy, at least towards the end of the Middle Ages. If we compare the boundaries of liturgical landscapes with those of the archbishoprics, we find that they do not correspond or only where archepiscopal provinces coincide with secular states. Where they do not, the states prove more decisive than the churches so that the use, however strange it may sound, is not a specifically ecclesiastical phenomenon.18 Since its primary role is to display the identities of sub-groups within the Western Christian commonwealth, it is not the inherent administrative system of that commonwealth which repeats itself through liturgical markers, but political-cultural entities express their loyalties and belonging together. Landscapes sometimes anticipate modern nation-states. Great Britain, Spain, France, and Germany had already formed valid liturgical categories in times when independent or only loosely connected states were operating in their territories. Within them, there are several features that could legitimately be called Catalan, Swiss, Silesian, or even Belgian.

Such national tendencies may seem familiar, but we must stress that they form a minority. With the exception of France, liturgical landscapes are typically larger than the later nation-states. The Ibero-Provençal landscape includes not only Aragón, Castille, or the Basque Country but also Portugal, Gascogne, and Provence; the Anglo-Norman landscape includes not only Scotland and Wales but Ireland and Normandy, too; and the Germanic landscape covers the whole of eastern and northern Europe, including Slavic, Baltic, and Magyar lands. These are multilingual, multicultural, and often administratively fragmented areas. Although national sentiments and aspirations for political independence were not unheard of in the Middle Ages (), nobody sought to replace the liturgy of the landscape for being associated with an oppressive power. It was something given, like the air that neighbors equally breathe.

By contrast, linguistically, culturally, and politically cohesive areas can only rarely be described as uses or convergent groups of uses. A ‘Europe of the regions’ approach has no precedent in liturgical history. Instead, artificial diversity prevails, evoking the vision of a ‘Europe of twin towns’. One key to this phenomenon lies in the medieval perception of space, as already explained above. It definitely answers the question of why the surrounding countryside is not necessarily linked to the city, but it does not justify that neighboring cities do not form a contiguous block.

In the absence of a clear explanation, let us recall two parallel anthropological observations for the sake of a thought experiment. The first is very simple; the essential gesture of identity formation is to delimit the self, that is, to establish who we are and who we are not. Each group makes this gesture in relation to its actual environment, so it is evident that it primarily seeks to distinguish itself from those closest to it (; ). While perfectly understandable, this separatist way of identity formation may justly remind us of the disastrous side effects of national, ethnic, or religious tensions. The second parallel, however, is rather positive. Exogamy, i.e., marrying from the outside, is a basic concept of traditional kinship systems. It is not about keeping the gene pool fresh (something mankind had no idea about for a long time)—in fact, dynastic marriage policies have always done the opposite. Exogamy and related phenomena ensure solidarity within and between societies precisely by obligingly moving the individual out of the in-group into the out-group (; ; ). The network of links connecting distant liturgical uses provides a similar cohesion.

9. Conclusions

With all this in mind, let us finally return to our starting point, the problem of the ‘Spanish’ traits in Durand’s pontifical.

Historically, Durand was active at the end of the fourth formative period, the beginning of which had been marked by the emergence of the new churches. The late 13th century appears to be relatively late for the accepted time frame of the Middle Ages, yet it was not late in the sense that it was still characterized by the skill and the occupation of making uses; liturgy was conceived as malleable to some extent. Accordingly, Durand not merely summarized and regrouped the legacy at his disposal but intervened creatively. His creative contribution, however, was not arbitrary brainstorming. It was a novel arrangement of the set of items and an inventive deployment of the editing principles available in the earlier tradition, similar to a game with fixed instruments and strict rules.

His aim was probably not to create a Roman Pontifical, and especially not a universal one. He was bishop of Mende, symbolically wedded to his diocese for life.19 This might have meant more to him, a Languedocien nobleman, than to many of his careerist colleagues, for, although living largely in Italy, he refused his appointment to the archbishopric of Ravenna. He compiled his pontifical primarily for his own cathedral, perhaps in part to compensate for the fact that he was not often seen in it. In his eyes, the primacy of the pope was not yet connected with the primacy of the use of Rome; there the pope was a diocesan ordinary with his particular rites and service books like every other bishop. Even if he envisioned that his pontifical was to be an international success, Durand had to strive for something comprehensive rather than purely Roman, and this aim could be best achieved by creatively combining Ibero-Provençal, Gallo-Germanic, and, of course, Roman elements.

During the pontificate of John XXII, such a combination began to carry a topical message. The Gascon pope and his headquarters in Avignon both belonged to the Ibero-Provençal landscape. Gallic, that is French, was the secular power whose support he chiefly enjoyed—exclusively Germanic features are underrepresented in Durand’s pontifical. And, at length, it was the prestige of Rome that ensured papal authority, even if away from Rome.

By the end of the fifteenth century, when the first printed edition appeared, and even more so by the end of the sixteenth century, when it was imposed with minor changes on the universal church, this situation had long been forgotten. But by then, the popes and their masters of ceremonies had long favored Durand’s pontifical; it had simply grown on them. This is how it could evolve into a monument of Romanity, regardless of its compilative and regional character.

The edifice of medieval liturgy rests on hundreds, if not thousands, of similar stories. It preserves the frozen memories of past decisions, influenced by historical contingencies, creative accomplishments, and what they meant to those who determined their long-term fate. In the High Middle Ages, both local churchgoers and the international ecclesiastical elite were deeply concerned with displaying their identities through the delicate diversity in worship, and thus, they left a lasting imprint on the liturgical map of Europe. When interpreting the various patterns of this map, we can conclude the historical strata to which they individually bear witness and, indirectly, determine the formative periods of distinct phenomena. Such maps, however, primarily record the occurrences of textual items in precisely defined positions of structures that contain them. The interaction of syntax-like structures and vocabulary-like items builds up languages, or more precisely, dialects, of ritual once spoken by local communities. These dialects are the uses, and the understanding of their kinship system through the mapping principle is what we meant to be the chief methodological result of this study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.I.F.; methodology, M.I.F.; investigation, Á.S.; resources, Á.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.I.F.; writing—review and editing, M.I.F.; visualization, M.I.F.; project administration, Á.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Eötvös Loránd Research Network (LP 2018-14/2018).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available here: usuarium.elte.hu/texts/intr/chart; usuarium.elte.hu/l/f72f; usuarium.elte.hu/l/0783; usuarium.elte.hu/l/29a2; usuarium.elte.hu/l/a5bd; usuarium.elte.hu/l/79aa (all accessed on 18 November 2023).

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements should go to Norbert Masir OPraem for professional English proofreading and Attila Egyed for bibliographical help in ritual studies.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | For the standard studies on the topic of medieval pontificals see (); (). These are summarised in (). The latest treatment of liturgical book types is (). |

| 2 | See e.g., the full title of the Filipecz-Pontifical from the 15th century: ‘Incipit Pontificale secundum novum ordinem sanctae Romanae ecclesiae, compositum per sanctissimum patrem dominum Ioannem papam XXII.’ Esztergom, Library of the Archcathedral Mss. 26 (John Filipecz/Pruisz, Várad, 1477–1490). |

| 3 | By ‘Roman’ we primarily mean the 13th-century Pontifical of the Papal Curia, edited by () and more recently by (). |

| 4 | On the question of whether there is an archaic society at all, and its interpretations, see (); (); (); (). |

| 5 | On the question of orthopraxy in general, see (); from a catholic perspective see (). |

| 6 | For a good example of the first position, see the studies in the following book (), for the second position see for example (). |

| 7 | On the liturgy of the religious orders, see (); (), the classic monograph on the liturgies of the primatial sees is (). |

| 8 | See also the list of Chant Databases on the site of Cantus Index (CI): cantusindex.org. |

| 9 | This key concept helps us to filter the relevant information and distinguish it either from the commonplace or from the ephemeral. Common features of the rite are meaningless from a comparative perspective. It is impressive that the introit Ad te levavi opens the first Advent mass all over Europe since the first graduals, but it will not tell us anything about diversity. Again, an isolated rhymed office of a local saint in a private breviary may be a precious document of poetry and devotion, but it cannot be interpreted in terms of continuity or cultural transfer. A piece of information should occur at least more than once to be meaningful, regardless of whether it multiplies within the same tradition or connects more. |

| 10 | In music, a typical tool is the post-Pentecostal Alleluja series, applied in the monumental catalogue of French service books, compiled by Victor Leroquais (, ); cf. (). For orations, attempts at grouping sacramentaries have been made by (); (); (), for lectionaries see (); (). |

| 11 | The classic monograph on the topic is (), see also with further bibliography (). |

| 12 | Both Mary Douglas () and Victor Turner emphasize () the code-like nature of ritual that can serve as an anthropological base for a liturgical syntax and vocabulary. On the syntactic approach to rituals see () and with further bibliography (). |

| 13 | The aim of the comprehensive database—which as a store of uses has been nicknamed Usuarium—is to describe this state of affairs in its entirety. It intends to collect every possible kind of service book from all of the documented institutions of the Latin Middle Ages and to include and organize their contents in a database that can handle every textual detail: the various types of liturgical books, the different genres of texts, and even the rubrical contents: Usuarium: A Digital Library and Database for the Study of Latin Liturgical History in the Middle Ages and Early Modern Period (a project of the Research Group of Liturgical History, hosted since 2015 by the Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, and from 2018 to 2023 by the Lendület [Momentum] Programme of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences): usuarium.elte.hu. See also the analysis of the mass in (). |

| 14 | For the foundation of dioceses, see (). |

| 15 | A useful tool is the Putzger Historischer Weltatlas with its constantly updated editions. |

| 16 | We allude to the term ‘différance’ as applied by Jacques Derrida (). |

| 17 | See e.g., the incipit of the (): Missale pro usu totius regni Norvegiae secundum ritum sanctae metropolitanae Nidrosiensis ecclesiae. |

| 18 | This is especially striking in the archepiscopal provinces of Cologne and Trier, divided by France and Germany, and on the Polish-German borderland. |

| 19 | See also the case of Pope Formosus (). |

References

- Amiet, Robert. 1990. Missels et Bréviaires Imprimés (Supplement Aux Catalogues de Weale et Bohatta). Propres Des Saintes (Édition Princeps). Paris: Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique. [Google Scholar]

- Ammerman, Nancy T., ed. 2007. Everyday Religion: Observing Modern Religious Lives. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Andrieu, Michel. 1940a. Le Pontifical Romain Au Moyen-Âge II. Le Pontifical de La Curie Romain Au XIIIe Siècle. Città del Vaticano: Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana. [Google Scholar]

- Andrieu, Michel, ed. 1940b. Le Pontifical Romain Au Moyen-Âge III. Le Pontifical de Guillaume Durand. Città del Vaticano: Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana. [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett, Robert. 1994. The Making of Europe: Conquest, Colonization, and Cultural Change, 950–1350. Princeton Paperback Print. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Batiffol, Pierre. 1893. L’Histoire Du Bréviaire Romain. Paris: Alphonse Picard et fils, éditeurs. [Google Scholar]

- Bäumer, Suitbert. 1895. Geschichte Des Breviers: Versuch Einer Quellenmässigen Darstellung Der Entwicklung Des Altkirchlichen Und Des Römischen Officiums Bis Auf Unsere Tage. Freiburg im Breisgau: Herder. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, Catherine. 1997. Ritual: Perspectives and Dimensions. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, Catherine. 2009. Ritual Theory, Ritual Practice. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berling, Judith A. 2005. Orthopraxy. In Encyclopedia of Religion, 2nd ed. Edited by Lindsay Jones. Farmington: Macmillan Reference USA, vol. 10, pp. 6913–16. [Google Scholar]

- Bintley, Michael, and Kate Franklin. 2014. Landscapes and Environments of the Middle Ages. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bourque, Emmanuel. 1958. Étude Sur Les Sacramentaires Romains. Studi Di Antichità Cristiana. Città del Vaticano: Pontificio Istituto di Archeologia Cristiana, vol. 25. [Google Scholar]

- Buchinger, Harald, and Andrew Irwing, eds. 2023. On the Typology of Liturgical Books from the Western Middle Ages. Zur Typologie Liturgischer Bücher Des Westlichen Mittelalters. Liturgiewissenschaftliche Quellen Und Forschungen. Münster: Aschendorff Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Cabié, Robert. 1982. Le Pontifical de Guillaume Durand l’Ancien et les livres liturgiques languedociens. Liturgie et Musique (IXe-XIVe s.). Cahiers de Fanjeux 17: 225–37. [Google Scholar]

- Chavasse, Antoine. 1958. Le Sacramentaire Gélasien (Vaticanus Reginensis 316). Sacramentaire Presbytéral En Usage Dans Les Titres Romains Au VIIe Siècle. Tournai: Desclée. [Google Scholar]

- Chavasse, Antoine. 1993. Les Lectionnaires Romains de La Messe Au VIIe et Au VIIIe Siècle. Sources et Dérivés I. Procédés de Confection. II. Synoptique Général. Tableaux Complémentaires. Spicilegii Friburgensis Subsidia. Fribourg Suisse: Éditions Universitaires, vol. 22. [Google Scholar]

- Chidester, David. 2016. Space. In The Oxford Handbook of the Study of Religion. Edited by Michael Stausberg and Steven Engler. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 328–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawkins, Richard. 1976. The Selfish Gene. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- De Libera, Alain. 1991. Penser Au Moyen Âge. Paris: Le Seuil. [Google Scholar]

- de Saussure, Ferdinand. 1996. Premier Cours de Linguistique Generale (1907): D’après Les Cahiers d’Albert Riedlinger = Saussure’s First Course of Lectures on General Linguistics (1907): From the Notebooks of Albert Ried. Edited by Eisuke Komatsu. Translated by George Wolf. Language and Communication Library. Oxford, New York, Seoul and Tokyo: Pergamon, vol. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey, John A. 2015. The Papacy and the Pan-European Culture. In Handbook of Medieval Culture. Fundamental Aspects and Conditions of the European Middle Ages. Edited by Albrecht Classen. Berlin, München and Boston: DE GRUYTER, pp. 1324–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derrida, Jacques. 1982. Margins of Philosophy. Translated by Alan Bass. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Descola, Philippe. 2013. Beyond Nature and Culture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- DiCenso, Daniel J., and Rebecca Maloy, eds. 2017. Chant, Liturgy, and the Inheritance of Rome: Essays in Honour of Joseph Dyer. Henry Bradshaw Society Subsidia. Woodbridge: Boydell Press, vol. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Dobszay, László. 1988. A Középkori Magyar Liturgia István-Kori Elemei? In Szent István és Kora. Edited by Ferenc Glatz and József Kardos. Budapest: MTA Történettudományi Intézet, pp. 151–55. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, Mary. 1996. Natural Symbols: Explorations in Cosmology. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Duntley, Madeline. 2005. Ritual Studies. In Encyclopedia of Religion. Edited by Jones Lindsay. New York: Macmillan Reference USA, vol. 11, pp. 7856–60. [Google Scholar]

- Dykmans, Marc. 1985. Le Pontifical Romain: Révisé au XVe Siècle. Studi e Testi. Città del Vaticano: Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, vol. 311. [Google Scholar]

- Eben, David. 1992. Die Bedeutung Des Arnestus von Pardubitz in Der Entwicklung Des Prager Offiziums. In CANTUS PLANUS 1990. Edited by László Dobszay, Ágnes Papp and Ferenc Sebő. Budapest: Institute for Musicology, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, pp. 571–77. [Google Scholar]

- Ersland, Geir Atle. 2015. Urban Land Ownership and Rural Estates: The Case of Three Scandinavian Medieval Towns. In Town and Country in Medieval North Western Europe. Edited by Alexis Wilkin, John Naylor, Derek Keene and Arnoud-Jan Bijsterveld. The Medieval Countryside. Turnhout: Brepols Publishers, vol. 11, pp. 265–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eubel, Konrad. 1898. Hierarchia Catholica Medii et Recentioris Aevi Sive Summorum Pontificum—S.R.E. Cardinalium, Ecclesiarum Antistitum Series: E Documentis Tabularii Praesertim Vaticani Collecta, Digesta, Edita. Edited by Ludwig Schmitz-Kallenberg. Münster: Brepols Publishers, vols. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Pritchard, Edward. 1965. Theories of Primitive Religion. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Figurski, Paweł, Johanna Dale, and Pieter Byttebier, eds. 2021. Political Liturgies in the High Middle Ages: Beyond the Legacy of Ernst H. Kantorowicz. Medieval and Early Modern Political Theology. Turnhout: Brepols, vol. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming, Fiona. 2020. The Downfall of ‘World-Cities’ in Oswald Spengler and D.H. Lawrence. Études Anglaises 72: 341–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Földváry, Miklós István. 2023a. Continuity and Discontinuity in Local Liturgical Uses. Ephemerides Liturgicae 137: 3–34. [Google Scholar]

- Földváry, Miklós István. 2023b. Usuarium. A Guide to the Study of Latin Liturgical Uses in the Middle Ages and the Early Modern Period. Budapest: ELTE BTK Vallástudományi Központ, Liturgiatörténeti Kutatócsoport. Available online: http://real.mtak.hu/172372/1/Usuarium-FR5.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2023).

- Foley, John Miles. 1991. Immanent Art: From Structure to Meaning in Traditional Oral Epic. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Foley, John Miles, and Peter Ramey. 2015. Oral Theory and Medieval Literature. In Medieval Oral Literature. Edited by Karl Reichl. Berlin and Boston: DE GRUYTER, pp. 71–102. [Google Scholar]

- Franz, Adolph. 1909. Die Kirchlichen Benediktionen Im Mittelalter I–II. Freiburg im Breisgau: Herder. [Google Scholar]

- Gamber, Klaus. 1968. Codices Liturgici Latini Antiquiores. Spicilegii Friburgenis Subsidida. Freiburg: Universitätsverlag Freiburg Schweiz, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Geary, Patrick J. 2002. The Myth of Nations: The Medieval Origins of Europe. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Geertz, Clifford. 1973. The Interpretation of Cultures. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Gittos, Helen, and Sarah Hamilton, eds. 2015. Understanding Medieval Liturgy: Essays in Interpretation. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Goody, Jack. 1977. The Domestication of the Savage Mind. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goullet, Monique, Guy Lobrichon, and Éric Palazzo, eds. 2004. Le Pontifical de la Curie Romaine au XIIIe Siècle. Sources Liturgiques. Paris: Éd. du Cerf, vol. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Grimes, Ronald. 1982. Beginnings in Ritual Studies. Washington: University Press of America. [Google Scholar]

- Grzybowski, Lukas G. 2021. The Christianization of Scandinavia in the Viking Era: Religious Change in Adam of Bremen’s Historical Work. Leeds: Arc Humanities Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gy, Pierre-Marie, ed. 1992. Guillaume Durand: Évêque de Mende: V. 1230–1296: Canoniste, Liturgiste et Homme Politique: Actes de La Table Ronde Du CNRS, Mende, 24–27 Mai 1990. Paris: Éd. du CNRS. [Google Scholar]

- Gyug, Richard F. 2016. Liturgy and Law in a Dalmatian City: The Bishop’s Book of Kotor: (Sankt-Peterburg, BRAN, F. No. 200). Monumenta Liturgica Beneventana. Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, vol. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Happel, Stephen. 1980. The ‘Bent World’: Sacrament as Orthopraxis. The Heythrop Journal 21: 288–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hen, Yitzhak. 1995. Culture and Religion in Merovingian Gaul: A.D. 481–751. Leiden, New York and Köln: E. J. Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Herwegen, Ildefons. 1932. Antike, Germanentum Und Christentum: Drei Vorlesungen. Salzburg: Anton Pustet Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Hesbert, René Jean, ed. 1963. Corpus Antiphonalium Officii. Rerum Ecclesiasticarum Documenta 7–12. Roma: Herder, vols. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hesbert, René Jean. 1935. Antiphonale Missarum Sextuplex d’après Le Graduel de Monza et Les Antiphonaires de Rheinau, Du Mont-Blandin, de Compiègne, de Corbie et de Senlis, 1st ed. Bruxelles: Vromant & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Hiley, David. 1980. The Norman Chant Traditions—Normandy, Britain, Sicily. Proceedings of the Royal Musical Association 107: 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohenschue, Oliver, Ulrich Riegel, and Mirjam Zimmermann. 2022. Heterogeneity in Religious Commitment and Its Predictors. Religions 13: 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huglo, Michel. 1999. Division de La Tradition Monodique En Deux Groupes ‘Est’ et ‘Ouest’. Revue de Musicologie 85: 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulsether, Mark. 2004. New Approaches to the Study of Religion and Culture. In New Approaches to the Study of Religion. Edited by Peter Antes, Armin W. Geertz and Randi R. Warne. Religion and Reason 42. Berlin and New York: Walter de Gruyter, vol. 1, pp. 345–81. [Google Scholar]

- Iltis, Ana S. 2012. Ritual as the Creation of Social Reality. In Ritual and the Moral Life. Edited by David Solomon, Ruiping Fan and Ping-cheung Lo. Dordrecht: Springer, vol. 21, pp. 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobson, Roman, and Linda R. Waugh. 2002. The Sound Shape of Language. Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jungmann, Josef Andreas. 1951. The Mass of the Roman Rite. Its Origins and Development (MIssarum Sollemnia) I–II. Translated by Francis A. Brunner. New York: Benziger. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, John Norman Davidson. 1989. The Oxford Dictionary of Popes. London and New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- King, Archdale A. 1955. Liturgies of the Religious Orders. London and New York: Longmans, Green & Co. [Google Scholar]

- King, Archdale A. 1957. Liturgies of the Primatial Sees. London, New York and Toronto: Longmans, Green & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Klauser, Theodor. 1935. Das Römische Capitulare Evangeliorum. Liturgiewissenschaftliche Quellen Und Forschungen. Münster: Aschendorffsche Verlagsbuchhandlung, vol. 28. [Google Scholar]

- Klauser, Theodor. 1965. Kleine Abendländische Liturgiegeschichte. Bonn: Peter Hanstein Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Krause, Hans-Joachim. 1987. ‘Imago Ascensionis’ Und ‘Himmelloch’. Zum ‘Bild’-Gebrauch in Der Spätmittelalterlichen Liturgie. In Skulptur des Mittelalters: Funktion und Gestalt. Edited by Friedrich Möbius and Ernst Schubert. Weimar: Hermann Böhlaus Nachfolger, pp. 281–353. [Google Scholar]

- Kreinath, Jens, Joannes Augustinus Maria Snoek, and Michael Stausberg, eds. 2006. Theorizing Rituals: Issues, Topics, Approaches, Concepts. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Laurent, John. 1999. A Note on the Origin of Memes/Mnemes. Journal of Memetics—Evolutionary Models of Information Transmission 3: 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- Le Goff, Jacques. 1957. Les Intellectuels Au Moyen ÂGe. Paris: Le Seuil. [Google Scholar]

- Leroquais, Victor. 1924. Les Sacramentaires et Les Missels Manuscrits Des Bibliothèques Publiques de France. Paris: Chez l’Auteur, vols. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Leroquais, Victor. 1934. Les Bréviaires Manuscrits Des Bibliothèques Publiques de France. Paris: Chez l’Auteur, vols. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Lévi-Strauss, Claude. 1963. Structural Anthropology. Translated by Claire Jacobson, and Brooke Grundfest Schoepf. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Lévi-Strauss, Claude. 1964. Totemism. Translated by Rodney Needham. London: Merlin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lévi-Strauss, Claude. 1966. The Savage Mind. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lévi-Strauss, Claude. 1969. The Elementary Structures Of Kinship. Edited by Rodney Needham. Translated by James Harle Bell, and John Richard von Sturmer. Boston: Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Loud, Graham A. 2007. The Latin Church in Norman Italy. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- MacKay, Angus, and David Ditchburn, eds. 2002. Atlas of Medieval Europe. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield, Mary C. 2005. The Humiliation of Sinners: Public Penance in Thirteenth-Century France. Printing, Cornell Paperbacks. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Menget, Patrick. 2008. Kinship Theory after Lévi-Strauss’ Elementary Structures. Journal de La Société Des Américanistes 94: 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mews, Constant J. 2011. Gregory the Great, the Rule of Benedict and Roman Liturgy: The Evolution of a Legend. Journal of Medieval History 37: 125–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaels, Axel. 2010. The Grammar of Rituals. In Grammars and Morphologies of Ritual Practices in Asia. Edited by Axel Michaels and Anand Mishra. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, pp. 7–28. [Google Scholar]

- Michałowski, Roman. 2016. The Gniezno Summit: The Religious Premises of the Founding of the Archbishopric of Gniezno. East Central and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 450–1450. Leiden: Brill, vol. 38. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Jon. 1993. Missions, Social Change, and Resistance to Authority: Notes toward an Understanding of the Relative Autonomy of Religion. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 32: 29–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowakowska, Natalia. 2011. From Strassburg to Trent: Bishops, Printing and Liturgical Reform in the Fifteenth Century. Past & Present 213: 3–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ong, Walter J. 1984. Orality, Literacy, and Medieval Textualization. New Literary History 16: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palazzo, Éric. 1993. Histoire des Livres Liturgiques: Le Moyen Âge: Des Origines au XIIIe Siècle. Paris: Beauchesne. [Google Scholar]

- Palazzo, Éric. 2006. Art and Liturgy in the Middle Ages: Survey of Research (1980–2003) and Some Reflections on Method. The Journal of English and Germanic Philology 105: 170–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palazzo, Éric. 2010. Art, Liturgy, and the Five Senses in the Early Middle Ages. Viator 41: 25–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pansters, Krijn, ed. 2020. A Companion to Medieval Rules and Customaries. Brill’s Companions to the Christian Tradition. Leiden and Boston: Brill, vol. 93. [Google Scholar]

- Parkes, Henry. 2015. The Making of Liturgy in the Ottonian Church: Books, Music and Ritual in Mainz, 950–1050, 1st ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkes, Henry. 2020. Henry II, Liturgical Patronage and the Birth of the ‘Romano-German Pontifical’. Early Medieval Europe 28: 104–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfaff, Richard W. 2009. The Liturgy in Medieval England: A History, 1st ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinker, Steven. 1998. How the Mind Works. London: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen, Niels Krogh, and Marcel Haverals. 1998. Les Pontificaux Du Haut Moyen Âge. Genèse Du Livre de l’évêque. Spicilegium Sacrum Lovaniense. Leuven: Peeters Publishers, vol. 49. [Google Scholar]

- Rollo-Koster, Joëlle. 2015. Avignon and Its Papacy, 1309–1417: Popes, Institutions, and Society. Lanham, Boulder, New York and London: Rowman & Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Romano, John F. 2014. Liturgy and Society in Early Medieval Rome, 1st ed. Farnham and Surrey: Ashgate. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, Els, and Arthur Westwell. 2023. Correcting the Liturgy and Sacred Language. In Rethinking the Carolingian Reforms. Edited by Arthur Westwell, Ingrid Rembold and Carine van Rhijn. Manchester: Manchester University Press, pp. 141–75. [Google Scholar]

- Rüpke, Jörg, and Emiliano Rubens Urciuoli. 2023. Urban Religion beyond the City: Theory and Practice of a Specific Constellation of Religious Geography-Making. Religion 53: 289–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, Luigi. 2021. The Norman Empire between the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries with Special Reference to the Normans in Southern Italy. In Rethinking Norman Italy. Edited by Joanna H. Drell and Paul Oldfield. Manchester: Manchester University Press, pp. 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahlins, Marshall. 2017. Stone Age Economics. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Salisbury, Matthew Cheung. 2018. Worship in Medieval England. Leeds: Arc Humanities Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severi, Carlo. 2015. The Chimera Principle: An Anthropology of Memory and Imagination. Translated by Janet Lloyd. Malinowski Monographs. Chicago: HAU Books. [Google Scholar]

- Skitka, Linda J., Brittany E. Hanson, Anthony N. Washburn, and Allison B. Mueller. 2018. Moral and Religious Convictions: Are They the Same or Different Things? PLoS ONE 13: e0199311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Jonathan Z. 1978. Map Is Not Territory: Studies in the History of Religions. Studies in Judaism in Late Antiquity. Leiden: E. J. Brill, vol. 23. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Jonathan Z. 1987. To Take Place: Toward Theory in Ritual. Chicago Studies in the History of Judaism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sodi, Manlio, and Achille M. Triacca, eds. 1997. Pontificale Romanum: Editio Princeps (1595–1596). Edizione Anastatica. Monumenta Liturgica Concilii Tridentini. Città del Vaticano: Libreria Editrice Vaticana, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Sonntag, Jörg, and Coralie Zermatten, eds. 2015. Loyalty in the Middle Ages: Ideal and Practice of a Cross-Social Value. Brepols Collected Essays in European Culture. Turnhout: Brepols, vol. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Spengler, Oswald. 1922. Decline of the West: Perspectives of World-History. Translated by Charles Francis Atkinson. London: G. Allen & Unwin, vol. II. [Google Scholar]

- Staal, Frits. 1979. The Meaninglessness of Ritual. Numen 26: 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, Christian, and Robert Klugseder. 2019. Textmodellierung Und Analyse von Quasi-Hierarchischen Und Varianten Liturgika Des Mittelalters. Das Mittelalter 24: 205–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storm, Ingrid. 2009. Halfway to Heaven: Four Types of Fuzzy Fidelity in Europe. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 48: 702–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taft, Robert F. 1986. The Liturgy of the Hours in East and West. Collegeville: Liturgical Press. [Google Scholar]

- Trondheim Missal. 1519. Missale pro usu totius regni Norvegiae secundum ritum sanctae metropolitanae Nidrosiensis ecclesiae. København: Paulus Raeff. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, Victor. 1976. Ritual, Tribal and Catholic. Worship 50: 504–26. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel, Cyrille. 1986. Medieval Liturgy: An Introduction to the Sources. Translated by William George Storey, Niels Krogh Rasmussen, and John Brooks-Leonard. NPM Studies in Church Music and Liturgy. Washington: Pastoral Press. [Google Scholar]

- Weakland, John E. 1972. John XXII Before His Pontificate 1244–1316: Jacques Duèse and His Family. Archivum Historiae Pontificiae 10: 161–85. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, Max. 2001. Wirtschaft Und Gesellschaft: Die Wirtschaft Und Die Gesellschaftlichen Ordnungen Und Mächte. Nachlaß 2: Religiöse Gemeinschaften, 5th ed. Edited by Hans G. Kippenberg, Petra Schilm and Petra Niemeier. Max Weber Gesamtausgabe. Tübingen: J. C. B. Mohr (Paul Siebeck), vol. I/22,2. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).