1. Introductory Scene

The doors of a small chapel are wide open. People cram together at the threshold. Only rarely does someone leave the interior while more and more people gather outside, popping into the chapel, pushing those around the door and trying to get inside. Above the crowd’s heads, at the far end across from the chapel door, I can see a coffin resting on a catafalque. The coffin is rather small, not covered, and a delicate female figure with a white shroud and a golden crown on her head is lying still, inside the coffin. Even from a distance I can recognize that it is a quite typical statue of Mary lying inside the coffin.

When I push through the crowd and move closer, I see her calm face, rosy painted cheeks and closed eyes. Golden ornaments that embellish the coffin, as well as a crown on Mary’s head, beam in the light of two candles. The murmured prayers of those packed inside the chapel hover in the hot air, creating a feeling of emotional intensity. Some people are visibly moved. A woman is wiping away tears falling down her face; another is holding a rosary with her eyes closed, and her lips move intensely in quiet prayer. Those who managed to shuffle their way toward the coffin approach it and touch Mary’s mantle; some stroke her face and kiss her clothes. Those standing farther away pass along their rosaries and the small devotional images they purchased before the celebration and ask a man standing next to the coffin to touch Mary’s statue with them (

Figure 1). After this “tactile blessing”, the rosaries and images are passed back to their owners, who will take them home as precious souvenirs and religiously meaningful objects.

This early Friday afternoon vigil and prayers signal the start of annual celebrations organized every year in Kalwaria Zebrzydowska during the weekend following the Feast of Assumption (August 15). The gathering takes place in a “Mary’s house”—one of several dozen chapels located in Kalwaria Zebrzydowska—a Roman Catholic shrine in southern Poland, created during the 17th century as a local replica of Jerusalem and the Holy Land (

Jackowski 1999, p. 119). A mourning vigil around Mary’s statue, exhibited in an open coffin inside a chapel that represents her Jerusalem home, will last for a few hours. Young females in white robes, who, the day before, washed the statue, anointed it with oil, dressed it up, and put it into the coffin, can be seen among the mourners inside and outside the chapel. At the end of the vigil, priests arrive to lead the Marian Vespers, which comprise an extensive, mostly sung, sequence of prayers dedicated to the contemplation of Mary and drawing on the Psalms. The coffin will be taken outside the chapel, where a spectacular “Mary’s funeral” will be performed by pilgrims arriving at Kalwaria, mostly from towns and villages in southern Poland (

Figure 2). The coffin will be carried in a grand procession to the Chapel of the Sepulchre of the Virgin Mary, where it will be laid in the Tomb of Mary before dawn. Two days later, on Sunday, early in the morning, pilgrims celebrate one more procession with the Marian statue. This time, a straight-standing crowned Marian statue, known as the “Triumphant Mary” and reminding people of Mary’s Assumption, will be carried under a baldachin from the Chapel of Sepulchre of the Virgin Mary to a big basilica—a central church of the Kalwaria shrine located on another side of the valley, a few kilometers from the Marian Sepulchre.

I decided to start my reflections on Marian pilgrimages in Poland with this brief description of annual Kalwaria Zebrzydowska celebrations as they reveal some significant features of “lived Catholic Mariology”: an intimate as well as communal relation people establish with Mary

through and

in various rituals (e.g., pilgrimages), sites (e.g., shrines) and objects (e.g., images). I understand lived Mariology as simultaneously produced by

and revealed in peoples’ practices and experiences. It is generated and experienced through actions and emotions that involve the figure of Mary as a present, actual, and real person who, ontologically, settles in people’s lives. Although the official teaching of the Catholic Church and its Mariology are an important background to the cultural and ethnographic cases discussed in this paper, I will focus on the lived dimension of Marian devotion and on lived religion in general, which refers to “religion as practiced rather than religion as prescribed” (

Hermkens et al. 2009, p. 3).

Within the last two decades or so, a growing number of scholars of religion, especially those who work within the domain of social and cultural anthropology, have opted for a lived religion approach as the most suitable theoretical and methodological perspective for understanding the unpredictable, entangled, counterintuitive, paradoxical, and creative ways people shape their religious lives (see, e.g.,

Hall 1997, pp. vii–xiii;

McGuire 2008). Lived religion avoids stigmatizing and reductionist dichotomies hidden in such opposing binaries as popular religiosity versus elite religiosity, folk religiosity versus official religiosity, countryside religiosity versus urban religiosity, etc. (see

Pasieka 2015, pp. 131–32). It also allows for a more cautious appropriation of the term “religion” itself, since we have learned to be conscious of the cultural and historical limitations and biases reflected in the ways in which we, as scholars, and those we work with define what “religious” is (

Lambek 2013;

Knibbe and Kupari 2020, p. 159). Consequently, the focus on practice has stimulated studies concerning the performative dimension of religion as well as the ways in which affect and the senses not only influence but also establish social and cultural realities in various religious contexts. It has also encouraged studies on the individualistic aspect of religion and a focus on bottom-up social forces, as well as on agency and empowerment accumulated through religious practices.

In approaching Marian pilgrimages in Poland in terms of lived Mariology, I draw on the practical, performative, material, and affective elements discussed and problematized in contemporary scholarly approaches toward lived religion (see

Baraniecka-Olszewska and Lubańska 2018; see also

Morgan 2005, p. 6). The affective and material dimension of Mary within lived Catholicism in Poland is strongly stimulated by pilgrimages. Marian holy images and statues are the most common goals of sacred journeys in the country. While sacred images can be interpreted in terms of “compressed performances” (

Pinney 2004, p. 8)

1 rather than as simple material representations of Mary, pilgrimages themselves function as performative acts (

Coleman and Eade 2004, p. 16). These acts establish the presence of Mary through pilgrims’ emotional and sensual involvement in rituals. Pilgrimages include intense bodily and sensual experiences, often connected with physical effort and even suffering (for instance, related to fasting, difficult weather conditions, walking long distances, or uncomfortable means of transportation or accommodation). Usually, these experiences are not only individual but also shared with others, and therefore, pilgrimages should be analyzed as community-building acts. Additionally, pilgrimages turn our attention toward the spatial dimension of “religious culture” of lived Catholicism, i.e., shrines and religious architecture. Shrines are affective, thick places and elements of religious cultural landscape that are not only celebrated but also discussed, questioned, and contested in today’s Poland (

Niedźwiedź 2014).

When emphasizing these aspects of Marian pilgrimages, I aim to reflect on the tensions and complex interrelations between the individual and communal dimensions of lived Mariology. The importance of political contexts and power relations should not be forgotten in studies of lived religion as politics and power are usually significant forces shaping people’s lives and influencing their choices and imaginations also within a domain of religion “as it is lived”. The lived Mariology approach, while drawing on the analysis of the individual, often intimate, relations people build with Mary, should not avoid interpretations of communal acts that are always performed in specific political and historical contexts. The emphasis on the practiced, material, sensual, and affective dimensions of religion allows us to see mechanisms that connect the intimate relations people create with Mary (and her images) with community forming processes. This paper will discuss these community-forming processes by focusing on Marian pilgrimages in historical and more contemporary contexts of Roman Catholicism lived in Poland.

2. Materializing Mary

Let us go back to the interior of Mary’s house in Kalwaria Zebrzydowska, where, on Friday afternoon, a few hours before the “Funeral of Our Lady”, pilgrims gather to perform a mourning vigil around a small coffin with a Marian statue laying in state. What can we learn from the emotional crowd filling the small chapel, where people pray the rosary, touch the statue, and sometimes cry and sing while awaiting the funeral procession? In fact, they all know very well that the several-days-long pilgrimage to Kalwaria Zebrzydowska is organized around the triumphant Feast of Assumption, and most of the public ceremonies—even the funeral procession—are performed in a solemn but also rather festive atmosphere. The crying and the sorrowful atmosphere inside “Mary’s house” seem to contrast with these generally cheerful festivities.

These intimate and intense prayers in the “Mary’s house” that precede the main ceremonies are of great ethnographic significance. The statue of Mary, her coffin visible in the light of candles, the small chapel, the rosary prayers, and the traditional mourning songs led by older and experienced pilgrims create an atmosphere of a personal, less official, and deeply emotional encounter with Mary. Significantly, those who gather here often recollect the funeral celebrations of their loved ones. Entering the packed chapel known as the “Mary’s house” and joining the emotional crowd around an open coffin not only reminds pilgrims about the apocryphal stories that described the simple life of Mary after Christ’s Ascension and her final days that concluded with

transitus to Heaven

2 but often also takes them back to their own emotional memories of the farewells and tributes they paid to the remains of their family members, friends, or neighbors. Mary—lying in an open coffin in her Kalwaria home—is able to enter the intimate worlds of her devotees not as a distant divine figure but rather as a real person, treated as “one of us”, i.e., someone who is deeply involved in family life and connected with people through familiar ties. Her “dormition”, “fainting”, or “death”—as pilgrims interchangeably use these terms—confirm her position as the patroness of a “good death” for those who pray around her.

When looking at Mary’s statue in the open coffin and observing the vivid interactions people have with this Marian image, it is also worth reflecting on the role that material religion plays in the construction of Mary within the lives and experiences of her devotees. For a long time, the material dimension of Catholicism was treated by both Polish scholars of religion and most theologians as something suspicious, connected with the “folk” and superstitious dimension of “religion”. In other words, religion was mostly understood in terms of beliefs and abstract ideas rather than practices and tangible objects. Indeed, within Polish academia, as in some other European countries, the first scholars who turned toward what we call now “material religion” (see

Morgan 2010) were ethnographers, folklorists, and sociologists interested in the “religious culture of peasants” (see

Czarnowski 1938), so those groups and classes of the society that perforce (due to low levels of literacy) had to formulate their religion not through theological treatises but through devotional practices. In my other publication, I have discussed in detail the Polish context and scholarly interests in peasant culture and religiosity. This interest brought reflection on Marian images as material objects around which specific “religious culture” can develop (see

Niedźwiedź 2015, p. 80).

Pioneering research on Catholic practices among Polish peasants was undertaken during the late 1930s by the cultural historian, religious studies scholar, and sociologist Stefan Czarnowski. After studying in Germany and France, he returned to Poland to become one of the leading figures in Polish academic life during the interwar period. Till his death in 1937, Czarnowski remained intellectually connected with the French

L’Année sociologique circle, which included Henri Hubert and Marcel Mauss (see

Czarnowski 2015). This intellectual cross-fertilization and Czarnowski’s interests in various cultural and national contexts (in Celtic culture and the Irish cult of St Patrick, for instance) allowed him to develop a fresh interpretation of Polish ethnographic material. Drawing on folkloristic sources collected in the nineteenth century, as well as on his own observations, Czarnowski described Catholic pilgrimages in Poland by reflecting on the centrality of Marian images and their material-symbolic entangled nature:

Images of holy figures, are, for our people, something more than mere pictures. They are symbols in the most literal meaning of the word, i.e., objects taking part in the nature of the imagined figure and summarising it.

This statement by Czarnowski, as well as the concept of “religious sensualism” introduced by him in the same 1938 paper, was rediscovered and reformulated during the early 2000s, when Polish anthropologists started scrutinizing religious practices using phenomenological and hermeneutical approaches, combined with ethnographic fieldwork sensitive to the practiced, material, and corporeal aspects of religions. These studies confirmed the centrality of images in lived Catholicism in Poland and their considerable role in shaping and creating the reality of religious experiences and relationships that people build with holy figures. Joanna Tokarska-Bakir, the author of a massive volume dedicated to the analysis of narratives, practices and sensory experiences related to miraculous images in Polish Catholicism, drew on Czarnowski’s “religious sensualism”, as well as on Hans-Georg Gadamer’s concept of “non-differentiation” (

Gadamer 2004, p. 134). She introduced the category of “sensual non-differentiation”, which refers to the specific way of experiencing holy images—through various senses—that is based on “the adhesion of image and referent”. According to her, this sensually created adhesion “is not a secondary phenomenon in relation to religious experience, rather it fundamentally establishes and enables it” (

Tokarska-Bakir 2000, p. 230). These terms, coined mostly in Polish academic literature, have received limited international recognition. However, it is worth pointing out that although the rediscovery and rereading of Czarnowski’s work on images and religious sensualism took place in Polish anthropology and ethnology of religion relatively recently, i.e., during the late 1990s and early 2000s, it has encouraged some younger scholars to appreciate the crucial role that sensual and bodily experiences play in “religion as it is lived” and has signalled the need for a material turn also in studies dedicated to pilgrimages.

In 2000–2001, during my first phase of ethnographic research dedicated to Marian devotion among Polish Catholics, I realized that the sensually and materially based relationship with the figure of Mary is usually established and maintained through interactions with her images. In lived Catholic Mariology, the “image” of Mary functions interchangeably with her “figure” (

Niedźwiedź 2010). Drawing on Hans-Georg Gadamer’s ontological understanding of images, we can see that in the context of lived Catholicism, Mary is

represented in her pictures. Here,

representation refers to “an autonomous reality”, a specific “emanation” of Mary, which does not reduce or limit her figure (“the original”) but makes her present through multiple and diverse forms of religious pictures. These pictures bring a specific ontological “overflow” or an “

increase of being” (

Gadamer 2004, p. 135). As autonomous realities, images can interact with human beings. Their materiality shapes these interactions in a form of “sensation” understood as “an integral process, interweaving the different senses and incorporating memory, and emotion” (

Morgan 2010, p. 8). The intimate relations that people build with holy images—seen in shrines but also kept at homes as cherished private souvenirs, usually small and inexpensive copies brought from holy sites—should be treated as a significant and meaningful part of lived Mariology that establishes Mary in people’s lives, forming their imaginative and practiced worlds within private and communal domains (

Figure 3).

When reflecting on their interactions with images, the pilgrims and devotees I talked to emphasized Mary’s “real presence”. They often pointed to the subjectivity of Mary experienced by them in concrete holy images not only in shrines but also in parish churches and even within homes. Through the words and descriptions they gave about holy images, Mary reveals her agency and communicates with her devotees through these material objects. According to people’s accounts, these images possess their own life. Thus, Mary’s face can be “sad, turned toward you as if wanting to say something”, she “looks at a man”, and her eyes can follow a person expressing feelings and changing emotions (like in this statement: “Our Lady of Częstochowa is sometimes sad and then she almost does not look people in the eye, while at other times her face is more cheerful”). When interacting with the images, people are able to talk to Mary, listen to her, sense her feelings and presence, observe grimaces and changing facial expressions, or even notice her subtle movements and gestures. These numerous accounts of sensual non-differentiation and the materializing of Mary through and in her images were aptly summarized by one of my interviewees. When a middle-aged woman from a village in southern Poland described her close relationship with Mary and the Marian image that accompanied her during critical moments of her son’s sickness, she summed up the story: “When I see this image, I see

something more than just an image—I see Mary herself” [my emphasis] (see

Niedźwiedź 2010, p. 149).

Images function as religious mediums, and their materiality is an integral part of religious mediation practices. Mary happens to be present and active in peoples’ lives through and in her images. We can link this anthropologically to the understanding of religion as a “practice of mediation” that bridges “a distance between human beings and a transcendental or spiritual force that cannot be known as such” (

Meyer 2009, p. 11). As proposed by Birgit Meyer, “adopting a view of religion as mediation” means that “the transcendental is not a self-revealing entity, but always effected by mediation processes, in that media and practices of mediation invoke (even “produce”) the transcendental in a particular manner” (

Meyer 2009, p. 11). In that sense, media (in our case, images) should be examined as an intrinsic part of religion. The concept of religious mediations allows us to understand images as religious media, where sensual, material, and affective aspects are of crucial importance. Materializing Mary, sensualizing her, and sensualizing the relationship with her—by touching, kissing, watching, listening to images or travelling to them in pilgrimages—cannot be reduced to “naïve” religiosity but should rather be interpreted as one of many forms in which religion works as mediation dedicated to the production of the transcendent. Belief is not experienced as an abstract thing. Therefore, Mary

happens in various material and sensual forms. Within Polish lived Catholicism, the abundant Marian images, and their popularity and significance organize and structure the material presence of Mary, and this is reflected in pilgrimage sites and pilgrimage practices.

3. Situating Marian Pilgrimages

The majority of Roman Catholic shrines in Poland are dedicated to Mary (

Datko 2000, p. 312), and most are built around holy images, which are usually panel paintings since sculptures are only rarely represented in the Polish Marian cult. This national feature is often linked by scholars to the geographic proximity of Poland to strong Orthodox centers such as Kiev, Novgorod or Moscow; historic links with the Byzantine, Ruthenian and Russian traditions of panel paintings and the influence of the Eastern Christian cult of icons; and the political, cultural and religious interactions between Latin- and Byzantine-oriented Polish monarchs, old noble elites and the various groups of people, which in the past centuries inhabited the Polish kingdom, as well as the ethnically and religiously diverse Polish Lithuanian Commonwealth (1569–1795) (

Czarnowski 1938, p. 171;

Trajdos 1984). Numerous pictures revered in contemporary Marian shrines in Poland have medieval roots, and they often mirror this complex cultural and religious history of the land and its people. Some of them are, indeed, of Orthodox or Byzantine origins, and their iconography directly relates to the Eastern Christian tradition of icon painting

3.

Apart from medieval and Byzantine-influenced Marian art, the second strongly represented iconographic period relates to the Catholic post-Tridentine revival and Counter Reformation era. This period saw the spread of Catholic baroque paintings and the creation of a “new chain” of Marian shrines across Poland–Lithuania that were constructed as fortresses of Catholicism; they were symbolic but also political and military bastions erected as a response to the Reformation movement, as well as martial shields against attacks from Turkish forces that were advancing quickly across Southeastern Europe. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Marian images and Catholic Marian shrines expressed the concept of

antemurale christianitiatis—the Bulwark of Christendom where Mary and her images functioned as a powerful protecting force, as well as a representation of victorious Catholicism (

Davies 2005, pp. 134–35).

In the seventeenth century, Kalwaria Zebrzydowska shrine—the place I described at the beginning of this text—was founded. It was the first shrine in Poland to “copy” Jerusalem and the Holy Land. The name Kalwaria—Polish for Calvary—recalls the centrality of the cult of Christ and his Passion. Soon after the construction of the first chapels dedicated to the crucifixion of Christ, annual Passion plays started to be performed for pilgrims visiting Kalwaria Zebrzydowska on Good Friday. However, this shrine also developed as a Marian sanctuary. The main church became famous for a Marian painting that was crying with bloody tears, and celebrations dedicated to Mary’s funeral and Assumption were organized, attracting numerous pilgrims every August. These three-day Marian celebrations—still performed in Kalwaria today—are built around “Mary’s Passion” and triumph—her dormition, funeral and transition to Heaven—situating her figure in a striking resemblance to the story of Christ’s Passion and Resurrection (

Kuźma 2008, pp. 225–27; see also

Zowczak 2019, pp. 331–48).

The Counter Reformation in Poland brought a strong revival of Marian devotion related to the spread of new images, the creation of new shrines, new pilgrimage routes and new devotional practices. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in all those new pilgrimage places, as well as in older Marian shrines, Mary was venerated as a Queen and protectress of her people—a figure especially desirable during this time of wars, plagues, and instability. The successful defense of the Jasna Góra monastery against an invading Swedish army (1655) was proclaimed to be a miraculous intervention by Mary and a turning point in the war that was devastating the country

4. The 1717 papal coronation of the image of Our Lady of Częstochowa and the announcement that she was a Queen of the Polish Crown was an act as deeply political as devotional (

de Busser and Niedźwiedź 2009, pp. 88–89). Up till today, Częstochowa—where Jasna Góra monastery is located—is a central and focal point of Marian geography and pilgrimage movement in Poland. Interestingly, while in some other Catholic-dominated European countries, the most important “national shrines” developed around a “new wave” of Marian apparitions during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, in the Polish case, this period brought only a few shrines related to visionary appearances of Mary. Even though some of these new places were saturated with nationally oriented meanings, they developed mostly at the regional level. Polish Marian veneration organized around the image of Our Lady of Częstochowa as a “national master symbol” functioned as the strongest referral point and was not undermined by new apparitional sites (

de Busser and Niedźwiedź 2009, p. 89)

5. For instance, during the period of the Partitions (1795–1918), when Poland was divided between Prussia, Russia, and Austria, in the year 1877, in the small village of Gietrzwałd, two young Polish girls reported apparitions of Mary, who spoke to them in Polish. Given the attempt by the Prussian authorities to suppress the Polish language, the popularity of the place among Poles living in the region developed very fast. They, as well as Poles arriving from the Russian partition, started calling this regional shrine “Warmian Częstochowa” and treated local pilgrimages as a substitute for pilgrimages to Częstochowa that were for some period banned by the Prussian authorities (

Porter 2005, p. 158;

Olszewski 1996, p. 185;

Jackowski 1999, p. 73).

Yet despite the restrictions by the partitioning powers during the nineteenth century, Częstochowa grew significantly as a nationally oriented religious centre. The image of Our Lady of Częstochowa spread through numerous copies that started to be affordable for a wider audience, which reached not only the higher strata of society but also the homes of peasants, even in remote areas of partitioned Poland. Walking to Częstochowa, as well as to many other Marian shrines, was often combined with both the religious and patriotic education of peasants who, when visiting sacred sites, were taught about the history of these places and could hear about historic figures, such as kings or national heroes, who had made pilgrimages to exactly the same spots centuries earlier. Our Lady of Częstochowa was also perceived as the “real Queen” of the Poles, who could unite people from the three different partitioned regions. The scars visible on Mary’s cheek in the original image exhibited at the Jasna Góra monastery and scrupulously repeated on the widely circulating copies started to be seen not only as the sign of the image’s miraculous powers and confirmation of the “real presence” of Mary in the picture (the scars were said to appear miraculously as a response to the attempted sacrilege of the image), but also as a symbol of pain and sorrow (

Niedźwiedź 2010, pp. 49–87). Mary, Queen of Poland, depicted not only in a crown but also with scars on her cheek, was seen as both a “heavenly ruler” and a tangible person, who suffers and sympathises with “her nation” conquered by the three partitioning powers.

The process of nationalizing a dominant religion (Roman Catholicism) and involving Marian pilgrimages in a community-building process continued during the twentieth century. During the Communist period (1945–1989), as I will show below, Marian pilgrimages and Marian images functioned as a means of empowerment as well as political and civic resistance against the regime authorities.

4. Community Binding

The potentiality of Marian images as mediums producing access to transcendence and, at the same time, as influential material forms around which communities organize themselves sharing religious, emotional, and aesthetic experiences, was very clearly revealed in the development of pilgrimage movement throughout the Communist period in Poland (1945–1989). Marian pilgrimages during that time evolved on the one hand as devotional, religious practices and on the other as politically inclined resistance, an expression of national community shaped in Christian terms which was itself understood as counter-Communist.

This community was aesthetically shaped around the image of Our Lady of Częstochowa, who—as in the nineteenth century—was described and lived as the “real ruler” of the Polish people, the nation’s Queen who was capable of opposing the political regime. Mary—materialized in her images—was seen by Catholic devotees as a powerful divine figure and a compassionate mother intervening during critical political moments. Those who were able to sensually and emotionally experience her presence were seen and felt as belonging to the same community of shared religious, ideological and aesthetic formation. The concept of “aesthetic formation”—introduced by Birgit Meyer—is very useful here, because it emphasizes that community is not given but rather imagined and mediated (

Meyer 2009, pp. 4–9). While drawing on Benedict Anderson’s concept of “the imagined community” (

Anderson 1983) and referring to the long-established sociological and anthropological tradition in studies of religion that emphasizes the powerful dimension of collective imageries, shared experiences, and practices (discourse anchored in classic works by Émile Durkheim), the concept of aesthetic formation accentuates a dynamic, fluent, and processual character of what is defined as “community”. Additionally, the forming, making, or molding of community happens through “embodied aesthetic forms”, where “aesthetic” is understood in the pre-Kantian way (as

aisthesis) and refers to the corporeal and sensory dimension of knowledge production (

Meyer 2009, p. 6; see also

Kapferer and Hobart 2005, p. 5). Shared imaginations “materialized and experienced as real”, “articulated and formed through media and thus ‘produced’”, “incorporated and embodied” are “invoking and perpetuating shared experiences, emotions and affects” (

Meyer 2009, p. 7). They are powerful tools that are actively participating in community-making processes. Marian images and pilgrimages can be thus understood as performative embodied acts and material mediums forming communal bonds between people who share the same religious aesthetics and corporeal experiences of the holy

6. Aesthetic formations organized

around and

through Marian images and pilgrimages in Communist Poland functioned as religious communities and at the same time as a strongly political empowering resistance movement.

Probably the first event that framed Marian pilgrimages in terms of national anti-Communist resistance and influenced further politicization of lived Mariology was related to the year 1949 and a copy of the image of Our Lady of Częstochowa exhibited in the Lublin cathedral—a city in eastern Poland. During July 1949, people praying in the cathedral reported a dark, bloody tear flowing down the Marian cheek on the image. Very soon, thousands of people from the city, its vicinity, and even further afield started gathering inside the cathedral to witness the miracle. Within one week, this spontaneous pilgrimage movement grew to such an extent that not only local Communist Party leaders but also the central government in Warsaw decided to intervene. National Communist newspapers published articles accusing the Catholic Church and its hierarchy for spreading turmoil and sabotaging the post-war reconstruction of the country by involving people in suspicious and superstitious practices around a “fake miracle” (

Żaryn 1997, p. 228). In response, pilgrims started to interpret the weeping as a manifestation of Mary’s suffering and solidarity with Polish people, encouraging them to resist Communist restrictions and the anti-religious policy of the government.

Things took a dramatic turn when, in a stampede among the cathedral crowd (probably provoked by the secret service), a young woman was killed. The national militia stopped pilgrims who were approaching Lublin in buses and trains and a massive Party demonstration was organized on the streets of the city. The demonstration ended up in front of the cathedral, where those pilgrims, who managed to reach the church, started singing Marian songs interlarded with anti-Communist slogans. This confrontation turned violent and ended in street riots that led to the arrest of few hundred pilgrims, as well as a show trial and prison sentences for some of them. Still, the “Lublin miracle”—as the events related to the image started to be called—brought about a popularization of a new pilgrimage site related to a “weeping Mary” and established a cult of Our Lady of Częstochowa in new political circumstances. Indeed, very soon, the image of Our Lady of Częstochowa was used by the Roman Catholic church in Poland as the most powerful tool in its confrontation with the official anti-religious policy of the Communist Party, also finding a vivid response in grassroots resistance civic movements that adopted religious imagery in their political and social struggles. The bonding and binding power of Mary developed into an aesthetic formation organized around this “national master symbol” (see

de Busser and Niedźwiedź 2009; see also

Wolf 1958).

Between 1956 and 1966, the Church prepared a cycle of massive pilgrimages dedicated to a millennial year. The millennium was intended to memorialize 966 C.E., when Duke Mieszko I accepted Christianity from Rome. Significantly, celebrations commemorating the “baptizing of Poland” were organized at Częstochowa even though the probable location of Mieszko’s conversion to Christianity was quite far from this city. Also, the origins of the monastery and the cult of the image of Our Lady of Częstochowa began much later than 966 C.E. Its first record comes from the late fourteenth century. Still, Częstochowa was depicted as the “spiritual capital of the nation,” and the image of Mary became the central point of the millennial celebrations. Already in 1956, one million pilgrims gathered around the monastery to perform “national vows” in front of the original image that was taken from the chapel and showed to the crowd. Later, the image received millennial crowns and millennial robes decorated with jewellery. In 1966, religious events attracted numerous pilgrims to Częstochowa and overshadowed the Communist state celebrations designed as a lay counterpoint to the “baptizing of Poland” and organized under the slogan of “one thousand years of Polish statehood”.

5. Inverted Pilgrimage

One of the most intriguing and probably the most creative adaptation of the concept of Marian pilgrimage during the communist period in Poland was the so-called peregrination of the image of Our Lady of Częstochowa. “Inverted pilgrimage”—a journey of the holy object that “visits” its devotees in their local churches or homes—is a devotional practice well known in the Orthodox tradition, where travelling icons and relics “function as both advertisement for the pilgrimage place and as a substitute for pilgrimage” (

Rock 2015, p. 56). In the Roman Catholic context, however, the idea of an inverted pilgrimage—“making an image into a pilgrim”—was reinvented and popularized on a global scale during the mid-1940s with the creation of a copy of the Fatima statue known as “the International Pilgrim” (

Morgan 2009, p. 53). This traveling Marian statue brought the “Fatima message” to various states and people. The ritual was politically loaded with the apocalyptical dimension of “Fatima secrets” interpreted in relation to the Cold War and international politics of anti-Communism (

Morgan 2009, p. 57).

While the Fatima statue was traveling across the Western world promoting new religious rituals based on the deep emotional and corporeal relationship with Mary, which mobilized and united Catholic devotees against the “threat of Communism”, on the other side of the Iron Curtain, in Poland, the Catholic Church initiated an inverted pilgrimage of the most venerated national Marian image: Our Lady of Częstochowa. Like the Fatima statue, the traveling image of Our Lady of Częstochowa was intended to embody Mary and enable people to have a very personal and emotional encounter with their “mother”, also deepening communal bonds and strengthening religiously defined national “aesthetic formation” organized around Mary as a “national master symbol”. In 1957, an “exact copy” of the original picture was painted at the Jasna Góra monastery, taken to the Vatican to be blessed by Pope Pius XII, and then returned to Poland. Here, after the ceremonial “touching” of the copy and the original, the peregrinating picture was sent to visit all the Catholic parishes in the country. Not accidentally, this inverted pilgrimage started in the northern and western areas of Poland—regions that had been incorporated within the country after the Second World War and inhabited mostly by those repatriated from pre-war eastern regions as well as by various migrants. The peregrination acted to consolidate these new communities and enroot them in Catholic tradition against the government’s atheist policies (

Kubik 1994, p. 112).

Indeed, peregrination progressing year by year in various regions was designed to embrace the whole country and appeared to be a huge success for the Catholic Church. Ritual was lived on both individual and communal levels, combining affective experiences of a “real encounter” with Mary—materialized and mediated in her image—with community bonding. Catholic inhabitants of villages or city districts gathered on their parishes’ borders to welcome a “car chapel”. After the car arrived, the image was kissed, unloaded and carried in a procession to a local church for a night vigil and celebrations on the following day (

Figure 4). Soon, smaller copies of the image were prepared and sent for circulation in private homes. This “small peregrination”, in parallel with events organized at the parish level, resonated with people’s private emotional experiences and deeply inscribed the image of Our Lady of Częstochowa in lived Mariology. During my ethnographic research, the small peregrination was often recalled by people and described in very emotional terms

7. The image was usually placed in the main rooms, decorated with flowers and ex-votos, and treated as a “real guest” and a “visiting mother”, someone who could “listen to your sorrows while you could tell her your problems” during intimate night vigils. Mary, as a “real figure”, was constructed in the sensual, corporeal and emotional responses people had when interacting with the peregrinating image (

Figure 5).

The peregrination exemplifies the mediation of the transcendent based on the production of the holy in religious objects. This takes place through the complex aesthetic interactions people have with these objects. The community bonding—organized around the image of Our Lady of Częstochowa—operated as both “experience near” (the closeness and intimacy visible especially during peregrination to private homes) and “experience far” (historical anniversaries depicted as “national events” and celebrated at Częstochowa in front of the original image)

8. This combination of “national” and “private” and “far” and “near” turned into a potent community bonding tool. The peregrinating image of Our Lady of Częstochowa united people, binding and empowering the Catholic community in Communist Poland. The interrelationship between the power ascribed to Mary and Mary’s power experienced by her devotees can be understood here in terms of “cogent connections” when

by repetitive performative acts, by selecting or duplicating her image, carrying it around, gazing at it, or narrating about it, presence is communicated and invested in Mary, enabling her to operate, to move and mobilize people.

Presence “invested in Mary” and produced through ritual practices performed during the peregrination of the image of Our Lady of Częstochowa revealed itself in the most meaningful way between 1966 and 1972 when the image was “arrested” by the Communist authorities. After the main celebrations of the millennium at Częstochowa, the image was not allowed to continue its scheduled pilgrimage to various dioceses and parishes. The car chapel with the image was stopped by militia and forced back to the monastery where special guards kept an eye on it.

In spite of these restrictions, the peregrination ritual did not stop even though the image was not present. In churches and locations scheduled for the peregrination, an empty frame was carried in processions and exhibited at local parish churches. People prayed before this empty frame in exactly the same way as they would to the image of Our Lady of Częstochowa, kneeling in front of the frame, kissing it, celebrating vigils and services, and carrying the empty frame during the public processions. In ethnographic interviews I conducted in the early 2000s, older people remembered this time. They recalled the peregrination of empty frames and described Mary as “imprisoned” and “arrested”. But at the same time, she was seen as traveling “with the frame itself”. Indeed, “the empty frame caused greater agitation” (as one of the interviewees said) and generated strong affective and emotional responses (see

Niedźwiedź 2010, p. 175). These responses bonded the aesthetic formation of pilgrims gathering for peregrination of the empty frame.

In people’s lived experiences and performative acts, therefore, Mary was produced and materialized even when her image was absent. As one interviewee emphasised, “I remember the procession with the empty frame. Everyone acted as if the image had not in fact been removed. Everyone saw it…”. The peregrination of the image, as an innovative pilgrimage ritual operating at individual, local and national levels, formed and strengthened aesthetic formations organized around and through the Marian image (religious medium). At a critical moment, when the material presence of the medium was banned, the community was able to re-produce, re-enact, re-present and re-create this medium, performatively materializing Mary through ritual actions and emotions.

6. Polarization and Diversification

The fall of the Communist regime (1989); economic, social and political transformation; the integration of Poland within the European Union (2004); growing transnational mobility (including many Poles who emigrated from the country after the EU opened its labor market to Polish citizens); and the development of new media are all factors that influenced lived Mariology during the first decade of the twenty first century. To understand the dynamics of Marian pilgrimages in today’s Poland, it is important to point to the strong political position that the Catholic Church acquired within state structures after 1989. This position was expressed through the signing of a concordat with the Vatican in 1993 and the introduction of religious education in schools, which, in practice, usually means Catholic religious education. During the last three decades, there has been a growing involvement of Church institutions and the Roman Catholic hierarchy in political debates, such as those connected with the law limiting access to abortion and related to the rights of LGBTQ+ people. An emblematic example is the development of far right-wing and nationalist Catholic media, Radio Maryja and Television Trwam. Mary, seen and lived as empowering and organizing independent resistance during the Communist period, started to be used as a symbol of power and a means to support the political strength and authority of Catholic institutions and right-wing politicians within the country. This shift of power relates to Marian images and contemporary pilgrimages within Poland and reflects both growing polarization and the diversification of attitudes towards Mary.

Probably the most visible aesthetic formation organized around the figure of Mary is the “Family of Radio Maryja”—a community of Catholics who listen to the radio founded during 1991 by a Redemptorist, Father Tadeusz Rydzyk. The success of Radio Maryja is based on a combination of mass media and traditional Catholic ritual forms, often rooted in deeply affective Marian religiosity, with a right-wing, nationalistic political stance depicted as continuing the rhetoric of resistance developed during the nineteenth century and continued under Communism (

Lubańska 2018, p. 119). This rhetoric organizes the “nation” around Mary, recalling her figure as a Queen of the Poles. The nation is defined in confessional terms as a community united by religious ties. Resistance is directed against “modern secularization”, the “de-Christianization” of “the West and EU”, and the general “decline of traditional/Christian values”. “Family” also builds upon strong emotional and familial ties, where Mary is lived as a tender mother celebrated in various religious forms and promoted via radio broadcasts, such as the life rosary prayer recited every day by listeners calling the radio station. This combination of well-known Marian-oriented sensational forms (rosary prayer, interactions with Marian images, pilgrimages) with newer ones (developed through modern mass media—TV, radio and internet) provides many listeners of the Radio Maryja with a feeling of continuity. This aesthetic familiarity seems particularly important when we realize that the “Family of Radio Maryja” developed during the period of immense social and economic change bound up with political transformation in Poland. Sensational forms connected to Mary appeared to be powerful tools forming—creating and recreating—the “Family” in the context of new political circumstances.

Each July, a massive national pilgrimage of the “Family of Radio Maryja” is organized at Częstochowa, where an open-air Mass is celebrated for around 100 thousand pilgrims who arrive by bus from various regions of Poland (

Figure 6). Another annual pilgrimage takes place in December to celebrate the “birthday of Radio Maryja” in the city of Toruń, where the radio is located. Here, the radio initiated the construction of a new immense shrine (2012–2016) dedicated to “Our Lady the Star of New Evangelization and Saint John Paul II”. At this shrine, a copy of the image of Our Lady of Częstochowa—originally owned by Pope John Paul II—is venerated and exhibited in the center of the church, which is designed as a replica of the Vatican papal chapel.

The politicization of the “Family of Radio Maryja” and its pilgrimages is seen as problematic by those Polish Catholics who do not share the political views promoted by the radio or prefer the less political vision of Catholic institutions functioning in a democratic modern state. Right-wing politicians not only participate in Radio Maryja pilgrimages but also give political speeches during religious celebrations—a phenomenon accelerated since the 2015 presidential and parliamentary elections, which were won by the right-wing Law and Justice party and which marked a turning point in recent Polish history (

Kinowska-Mazaraki 2021, p. 1). While right-wing politicians emphasize their connection with Mary in her national shrine, the significant recent drop in Catholic practices and the decreasing number of Poles who identify as Catholics are mirrored in the declining number of pilgrims visiting Częstochowa.

Interestingly, many Polish Catholics seem to be disappointed with the appropriation of this main Marian shrine by right-wing politicians

9. This disaffection has resulted in the diversification of Marian pilgrimages and the appearance or reinvention of pilgrimages at local and regional levels. Recent cults dedicated, for instance, to Father Pio, Divine Mercy, Saint Rita, or Saint Charbel attract Polish Catholics, who are seeking new forms of spirituality. The Charismatic Catholicism that focuses on personal spirituality and healing (understood in physical and spiritual terms) has inspired new pilgrimage rituals, such as the Extreme Way of the Cross, an overnight 40 km run dedicated to prayer and meditation on the Passion of Christ (

Siekierski 2018) or the

Camino routes invented in various parts of Poland. Many of these new pilgrimages are not Marian-oriented, even though they might include “traditional” Marian shrines and images into their routes and itineraries.

Mary, embraced by the nationalistic and fundamentalist stream of Catholicism in Poland, is seen by those who do not belong to the current religious–national aesthetic formation as a problematic symbol of power and authority, especially in the post-2015 political landscape, which is officially dominated by the national Catholic-oriented public discourses and practices. The 2017 Marian national pilgrimage, organized as a “Rosary to the borders”, stirred a public discussion in Polish society and media. The chain of people who, on the 7th of October, stood along the Polish state’s borders enclosing the country in a public prayer of the rosary “to save Poland and world”, was seen by many as controversial. In its official announcement, the “Rosary to the borders” referred to the Feast of Our Lady of Rosary and the anniversary of the battle of Lepanto (1571) when the “Christian fleet defeated a much larger Muslim fleet and saved Europe from islamisation”

10. Critics of this pilgrimage pointed to its Islamophobic dimension and the Polish government’s refusal to “open borders” to refugees and immigrants. In further discussions, opponents of the “Rosary to the borders” recalled the figure of Mary as a refugee herself—a poor Palestinian woman fleeing with the baby Jesus to Egypt. Mary, “as a refugee”, who crossed borders, was poor and needed help, was presented as a counter-image to “Mary, Queen of Poland”. These symbolic images of Mary have returned again and again in public discourses, which have accelerated since the 2021 humanitarian crisis connected with the pushbacks of refugees on the Polish–Belarusian border

11.

Recently, in politically and ideologically polarized Poland, the most popular and well-known Marian image—Our Lady of Częstochowa—also appeared in a public discourse, which sought to give a voice to the members of the LGBTQ+ communities. These communities were repeatedly attacked not only by right-wing politicians but also by a number of Catholic clergy in Poland, including some bishops (

Kinowska-Mazaraki 2021, p. 10;

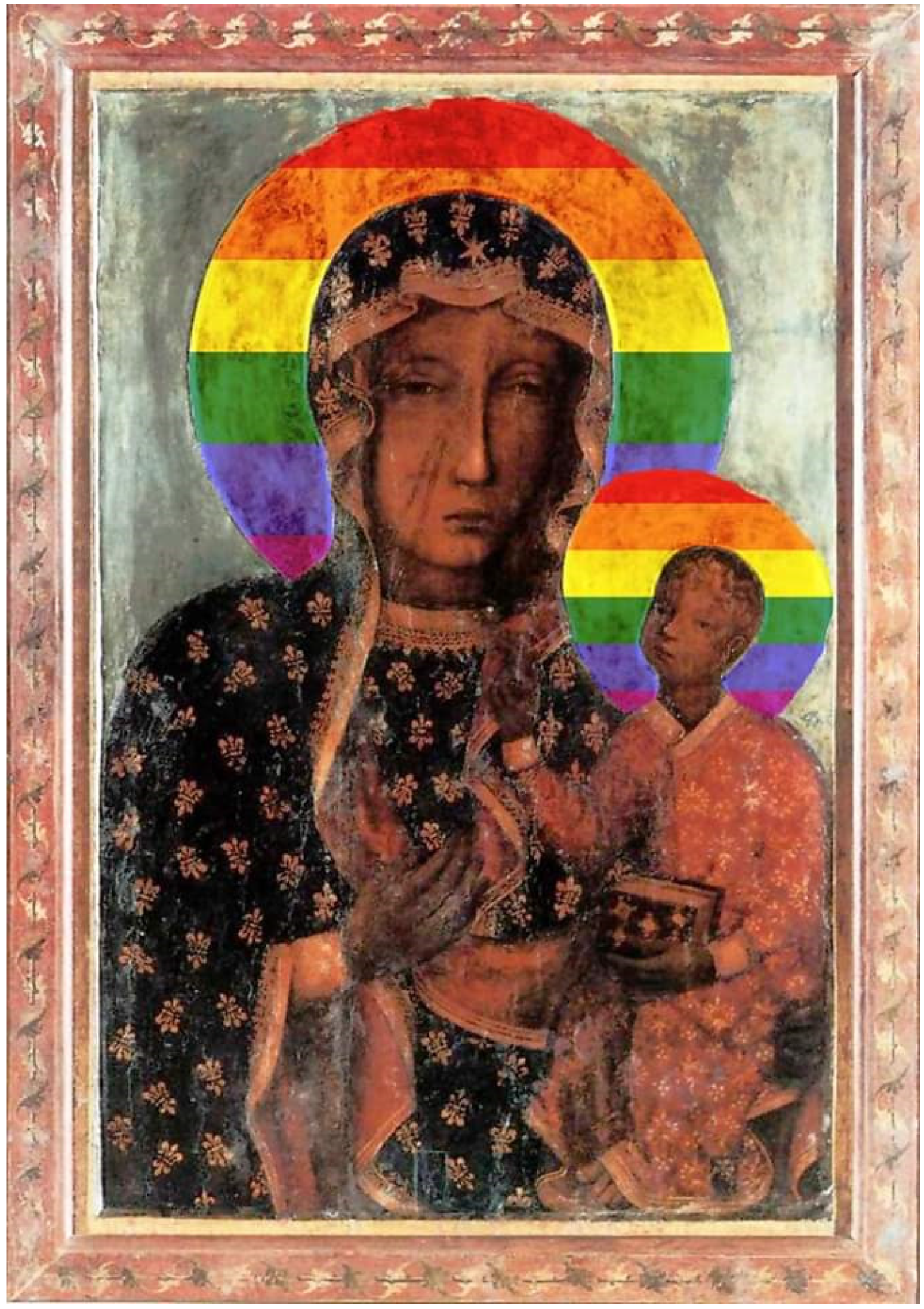

Maćkowiak and Zawiejska 2022, p. 112). In 2019, three activist women (Elżbieta Podleśna, Joanna Gzyra-Iskandar, Anna Prus) designed and publicly circulated a poster depicting the image of Our Lady of Częstochowa with Mary’s and Jesus’ halos in LGBTQ+ rainbow colors (

Figure 7). They did it as a response to an anti-LGBTQ+ Easter installation in one of the cities of Płock’s churches (

Urbanski 2022, p. 9). Right-wing traditionalist Catholic circles in Poland, as well as bishops, loudly protested against the “Rainbow Madonna”, and a legal action against the “insult of religious feelings” was even begun against the three women activists (in 2021, the court dropped the charges). However, at the same time, some Catholic circles in Poland and abroad emphasized that the “rainbow is not an insult” and argued that Mary was a symbol of inclusive love and openness, reflecting the general ideals of the Catholic faith.

12 7. Conclusions

The emotions and disputes triggered by the “Rainbow Madonna” reflect the growing polarization of Polish society over the role of the Roman Catholic Church in the country, as well as the diversification of lived Mariology, which has been encouraged by the development of alternative discourses about Mary. While practices and experiences related to Mary are still recognized within a Catholic religious context and are often interpreted through a political history of the Christian faith in Poland, Mary is also present as a powerful female figure and a spiritual symbol outside this domain. Her figure attracts spiritual seekers of universal female power and energy who do not identify with Christianity or any organized religious tradition. These alternative discourses and practices dedicated to Mary reveal that symbols and images establish their meanings in the lived experiences and affective attitudes of people

13.

Summing up, I have focused in this article on those aspects of Roman Catholic Marian pilgrimages in Poland which, in my opinion, bring a better understanding of their role in constructing Mary as a meaningful figure in the lived experiences of many Catholics, in the past as well as in more recent times. The historical development of pilgrimages, in the context of various symbolic meanings associated with Marian images, is crucial to explaining the popularity of Mary and her images in contemporary public social and political debates within Poland. This historical development is also vital to understanding contemporary Marian religiosity in Poland—a religiosity that extends beyond what is defined as “officially Catholic”. Due to specific historical circumstances (Byzantine influences during the Medieval period, the Marian-centric Counter Reformation during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and the development of religious–national symbolism during the nineteenth century), Roman Catholic pilgrimages developed mostly around Marian shrines, which were usually connected with Marian images. Some of these images, especially the image of Our Lady of Częstochowa, came to be recognized and experienced as community-binding symbols used in various political circumstances. In the Communist Polish People’s Republic, this binding potential was revived through some innovative pilgrimage movements, e.g., the Church-organized “peregrination” of the image.

Through these examples, I have sought to emphasize that an analysis of political developments undertaken through the lens of material and lived religion allows us to see the complexity of individual and communal relationships. Mary establishes herself as a real figure in peoples’ individual lives but also has a powerful bonding potential when used by groups and communities in various social and political contexts, especially when these communities share certain historical and religiously based imaginaries.

The concept of aesthetic formation, which I have drawn on, helps not only to emphasize the temporality and contextuality of what is seen and defined as a “community” but also to recognize the importance of the sensual, emotional, affective, and material aspects of religion. The changing faces of Marian pilgrimages in Poland—historically and more recently—reflect complex social and cultural processes that involve individual bodies and affects, bonded and shared communal experiences, as well as those processes that establish boundaries and divisions between various aesthetic formations. The physical presence of Marian images in both contemporary ideological debates and different and diversifying private and public practices reminds us that people use significant material objects, live in their company, and interact with them to variously negotiate and build their personal and communal identities.