Abstract

The arrival of Islam to the Iberian Peninsula at the beginning of the 8th c. brought important changes to the urbanism of cities which contributed to turn the previous late-antique realities into medieval Islamic settlements. Among all the transformations that took place, the introduction of mosques and the reconfiguration of cities’ religioscapes is one of the most relevant. The processes through which the earliest mosques were first inserted in urban landscapes in al-Andalus are unclear, since so far there are no remains that can be undoubtedly dated before the Umayyad period. From that moment on, and alongside the Umayyad organization of the Andalusi state, the founding of mosques becomes clearer and traceable, and their urban, religious and political roles more evident. This contribution seeks to identify how and why mosques appeared in the Iberian Peninsula, how they (re)configured religious spaces in cities, and how they contributed to consolidate their significance through specific written and architectural narratives. This topic will be explored also seeking for parallels and connections in the Bilād al-Shām region.

1. Introduction: Mosques in Cities of al-Andalus

The pre-eminent role developed by religion in Muslim culture has always explained the nature of mosques as vital centres of cities, able to activate and encourage social and economic dynamics together with being the heart of religious activities. Mosques are, undoubtedly, an essential urban element in Islamic social dynamics and are always taken for granted in urban scenarios—where there is a city inhabited by Muslims, there is a mosque. Actually, and despite the absence of Quranic guidelines specifying how they should look or be built, the architectural and structural concreteness of these buildings began to take place, from the earliest times of Islamic expansion, within the cities.

However, it is not only the religious factor that gives mosques their importance and significance. Although these buildings were places of worship and Islamic teaching par excellence, they were conceived to fulfil many other functions as well. During the medieval centuries, different rulers and political systems found in the construction of mosques a very effective propagandistic means to launch certain messages through carefully designed architectural and decorative programs. In the case of al-Andalus, the programming and execution of great architectural and urban works involving mosques, also served to establish signs of political legitimization1.

Simultaneously, this official or political intentionality coexisted with the normal, everyday use that the inhabitants of the cities gave to these mosques, which also contributed to a greater extent to their raison d’être. The inhabitants of the different neighbourhoods would attend to mosques not only for daily prayer, but also to solve other matters related to justice, to find legal advise, for teaching and learning activities or just to find other people. Thus, their significance is not only explained by their relationship with political needs and agendas, but also by their transcendence in everyday life. Despite this, which mosques where first built in al-Andalus and how, in which places specifically and by which agents are questions that do not have clear answers yet, since the information available to approach this topic is uneven and, in certain cases, even contradictory.

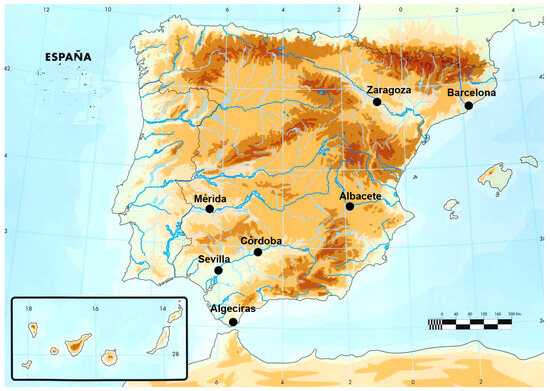

Regarding the aforementioned, and in light of the specific study cases study cases that have been selected (see Figure 1), this paper aims to explore how and why mosques appeared in the Iberian Peninsula, how they (re)configured religious spaces in cities, and how they contributed to consolidate their significance through specific written and architectural narratives by combining the written, archaeological and epigraphical information available and by identifying connections, when possible, with the Bilād al-Shām region.

Figure 1.

Location of the main cities mentioned in the text (made by author, basis map from Creative Commons).

2. Written Accounts about the Earliest Andalusi Mosques and Their Material Confrontation

The material horizon of the earliest Islamic occupation of the Iberian Peninsula is hard to detect from an archaeological viewpoint. Even though significant advances are being made (Gutiérrez 2011, 2012), the earliest archaeological contexts of the Conquest and its aftermath very often look too similar to the following emiral ones. Speaking specifically about mosques, archaeological evidence associated to their foundation and building in al-Andalus before the arrival of the Umayyads in the mid. eighth century has not clearly been recovered yet2. Therefore, approaching pre-Umayyad mosques requires turning to written chronicles that transmit accounts about the conquest of the Iberian Peninsula, all written afterwards and mainly in the Umayyad period. This work has been extensively done by Calvo (2007, 2020). She states that these sources often construct foundational myths to explain the appearance of the earliest mosques with a heavy symbolic load that covers or distorts the historical reality. This would be the case of the texts that describe the foundation of the Friday mosque of Zaragoza, attributed to the Tābi‘ Hannāš ibn ‘Abd Allāh al-Şan’ānī. According to the Muslim historiography, this mosque was founded in the early eighth century by this renowned character, who would have also established the orientation of its mihrab. If this were to be true, this mosque would have been one of the first ever founded in al-Andalus. However, the credibility of this information, that also states that al-Şan’ānī died and was buried in Zaragoza, has been long questioned (Vallvé 1967, p. 276; Souto 1989, pp. 392–97; Calvo 2007, pp. 154–55), since he probably never visited al-Andalus (see Marín 1981, pp. 30, 32). At this respect, the accounts about this character and his relationship with Zaragoza and its Friday mosque can be considered as part of a cycle of legends and myths that aimed to legitimate the existence of this building and its early chronology (Marín 1981, p. 31; Souto 1989, pp. 397–98).

A similar situation is recorded for the first mosque of Algeciras, attributed by several authors to the Arab conquerors (Calvo 2007, p. 148-ff.). Even though the information contained in the different chronicles is uneven and sometimes unclear—perhaps due to transmission mistakes, Calvo identifies in the writers the clear intention to locate the earliest Andalusi mosque in this city and its foundation by Arab conquerors, particularly by Mūsā b. Mūsā (Calvo 2014, p. 32). In this regard, several authors state that Mūsā b. Mūsā was particularly interested and worried about establishing himself the correct orientation for this qibla wall (Calvo 2007, p. 152).

Chronologies suggested by these tales are difficult to contrast from a material viewpoint, since the majority of the mosques that they refer to has not been identified so far. Nevertheless, one exception is the mosque of Zaragoza. It has been located by archaeology in the current Seo, the Christian cathedral built in the twelfth century reusing the previous Islamic building. Here, some very residual structures documented could have belonged to a very early phase of the mosque, but they are too reduced to confirm the chronology stated in written sources or even to perceive the general structure of a first Muslim building (Hernández Vera 2004, p. 75). The following phases documented correspond to building works and refurbishments that cannot be dated before the second half of the ninth century (Hernández Vera 2004; Bienes et al. 1996–1997). According to the archaeological analyses, this phase could correspond to the first big enlargement developed in the original mosque described in written sources, perhaps commanded by Mūsā b. Mūsā (see Hernández Vera 2004, pp. 75–78), but that first mosque, or at least a mosque founded before the ninth century, coinciding with the early chronology defended by written sources, is still to appear.

Calvo has noted that in the case of al-Andalus, Arab authors repeat or reinterpret certain topics and tales already in the futūḥāt from the Levant and North Africa (Calvo 2020, p. 32-ff.), insisting on associating prestigious characters with the emergence of certain mosques to ensure, from a historiographical viewpoint, the religious purity of the founders and the buildings they established, as well as the orthodoxy in the initial process of islamization. According to this author, the conscious late creation of this narratives established topoi that became key to consolidate the Umayyad power in al-Andalus (Calvo 2020, p. 31).

3. The Interaction with Previous Religious Architecture: Myths and Material Data

The aforementioned written sources indicate that the erection of the first Andalusi mosques often involved the systematic destruction of previous religious buildings, such as churches and basilicas. This idea is also transmitted in the Bilād al-Shām region. However, once again such urban dynamics have not been confirmed from a material viewpoint so far. Rather the opposite, material evidence suggests that a violent occupation and destruction of late-antique cultic spaces did not happen, or at least not on a regular basis. One very illustrative example is the basilica and baptistery located in Tolmo de Minateda in Hellin, Albacete (Gutiérrez 2004, and others from the same author). It was erected probably by the end of the sixth century or, best, already seventh century (Gutiérrez 2004, p. 151). The place for baptism lost its original function at a certain point in the eighth century and was ruined in the following century (Gutiérrez 2004, p. 155). Similarly, the basilica was desacralized in the second half of the eighth century (Gutiérrez 2002, p. 308). The area was then progressively occupied with structures dated in the ninth century that ended up conforming a neighbourhood once the previous building was completely buried, except for certain walls that were reused in the new Islamic constructions. This neighbourhood included dwellings and a central industrial sector with workshops, but not a mosque (Gutiérrez 2002, pp. 308–10)3. Even though these dynamics contribute to disassemble the belief that churches were regularly dismantled during the early Islamic times, they cannot be generalized due to the general scarcity and/or partiality of the remains documented.

In this regard, in Barcelona, where the Andalusi phase lasted less than a century, only minor changes instead of big new building programs involving massive destructions have been recorded. J. Beltrán believes that this period was not very active in terms of big constructions (Beltrán 2019, p. 203), which can be seen in the continuity of use of the spaces for prayer that belonged to the previous center of power, only affected by minor and very specific refurbishments and architectural adaptations. According to Beltrán, the reception hall of the bishop and the baptistery from the episcopal complex could have been reoccupied in the eighth century as Muslim places for reunion and prayer. Both spaces were very suitable to meet the needs of the new Islamic population, as they were conveniently oriented and provided with water (Beltrán 2019, p. 208). The inside of the baptistery, allegedly used for ablutions, was not transformed. On its side, the bishop’s reception hall, which could have operated as oratory or mosque because of its orientation, was slightly adapted with new walls that could have divided it into two main areas, a probable prayer room and a courtyard (Beltrán 2019, p. 209), even though definitory elements such as a mihrab have not been identified yet. The walls of the former episcopal hall were covered with a new white and ochre plaster. From these evidences, the configuration of a new mosque here in the eighth century cannot be affirmed, but the data available so far are suggestive enough to consider the hypothesis of an early configuration of Muslim place for prayer in this spot. Beltrán suggests that, since the Muslim occupation in Barcelona lasted short, and since no large building initiatives have been detected in any point of the city so far, the lack of strong or monumental modifications in this particular space should not be very surprising (Beltrán 2019, pp. 210–11).

In line with these ideas, S. Calvo collects other examples of churches or late-antique religious facilities that were desacralized or abandoned when the Muslims arrived to the Iberian Peninsula or immediately after, but their conversion into mosques cannot be assured from an archaeological viewpoint. These are the basilica of Casa Herrera (Badajoz), the church of El Gatillo (Cáceres), or the mausoleum of Las Vegas de Pueblanueva (Toledo). In all these cases, different refurbishments or small modifications dated in Islamic times have been recorded, but their interpretations and exact dating are so far too imprecise to suggest that they responded to religious conversions (Calvo 2007, pp. 164–66). Nevertheless, the difficulties for indubitably identifying these changes as religious ones could also be understood as the absence of an aggressive and immediate substitution of churches by mosques, at least in rural contexts. A different example is that of Bovalar, a Christian settlement that counted on a basilica (Palol 1989) that was remodeled around the 5th century4. According to the archaeological record, the whole site was violently destroyed by a fire in the 8th century, probably in the years immediately after the Conquest (Gutiérrez 2011, p. 192). Thus, it was never reoccupied, and its religious area never turned into a mosque.

In addition, there are also several cases of Christian religious spaces originated in the 5th century that remained in use after the Islamic conquest, such as the case of Santa Coloma in Àger (Lleida) (Bertran and Fite 1986). Here, the excavation of the remains of a cemetery linked to a church from the 5th century evidenced that a numerous group of Christians persisted during and after the Islamic conquest into the High Middle Ages (see Brufal 2018, pp. 26, 34–35). So far, none of the archaeological interventions developed in the area of Àger have documented a clear horizon of Islamic occupation, but the continuation of the Christian life (Brufal 2018, p. 35).

Probably the most discussed and controversial5 Andalusi example regarding this topic is the Great Mosque of Córdoba, which has been widely analyzed by different scholars in many other publications, as noted by M. J. Viguera (see Viguera 2022). It is out of the scope of this paper to do the same in detail, given the main topic of this paper, it is mandatory to consider some data provided by texts regarding the foundation of this renowned mosque. As Viguera reminds us—and trying to get away from the intensified debates that have been taking place in the last decades-, there are eight different sources mentioning the precedents and first steps of the history of this mosque, and none of them were written spontaneously nor coetaneously to the facts they narrate. Rather the opposite, they were very consciously elaborated in order to serve different political, literary, geographical and juridical purposes (Viguera 2022, p. 372)6. Thus, the existence of a previous church and a mosque before ‘Abd al-Raḥmān I’s project are mentioned in several of them, but no details are provided about how the erection of this previous mosque and, finally, the great Umayyad mosque, exactly took place. The aim of these sources is, once again, to create a calculated account that draws narrow comparisons with the situation in Damascus, shows the Umayyad’s respect for the pacts established with the Christian community after the Conquest (Viguera 2022. p. 383-ff.) and, after all, to emphasize that, by the end of the eighth century, the founder of the Umayyad dynasty in the West, ‘Abd al-Raḥmān I, also founded the Friday mosque of its capital as the great and main dynastic reference (Viguera 2022, p. 391).

Very recently, and in the frame of a new research project7, the Patio de los Naranjos of the former mosque is being re-excavated. Within these new archaeological interventions, the process through which this space, that belonged to the episcopal complex of the city, was progressively transformed and finally occupied by a Muslim construction are being gradually unveiled. Pending further information on this issue, the written sources available should be read and analyzed prudently, as they equally intend the creation of a legendary narrative to praise and legitimize the origins of this mosque (Khoury 1996, pp. 83–86), which eventually became the best incarnation of the Islamic hegemony in the Iberian Peninsula (Dodds 1992, p. 11).

A glance at the Bilād al-Shām region reveals interesting similitudes between both areas. In the greater Syria, urban mosques were placed in relation to previous Christian churches or basilicas without involving their annulment or destruction. As M. Guidetti explains, changes and reconfigurations of religioscapes in the Levant would have been highly conditioned by the treaties and pacts of Conquest, thanks to which the property of plenty of churches and basilicas by the conquered communities would have been ratified and the buildings respected (Guidetti 2013, pp. 231, 253). Guidetti identifies two moments in the foundation of the first mosques. The first moment refers to the erection of mosques in the immediate aftermath of the Conquest, often poorly planned and rarely monumentalized (Guidetti 2013, p. 232), from which the archaeological evidence is still to appear. The second one corresponds mainly to the Umayyad period, where plenty of these mosques were monumentalized alongside the building of new ones (Guidetti 2013, p. 233-ff.). In this last period, the introduction of mosques in urban landscapes responded to official major building programs developed by the Umayyad caliphs and, therefore, conceived within pre-arranged plans of Islamization and urbanization.

For the Umayyad period, this author provides plenty of examples to prove that the earliest Umayyad mosques in the Levant were built in direct and close relationship to great churches -some of them already extant-, adopting different insertion patterns that did not involve, at least in principle, obliterating the previous religious buildings (Guidetti 2013, p. 248). Thus, he identifies mosques built within the enclosure of already existing churches, such as Damascus; mosques close to churches but independent from them -for instance, Aleppo; and mosques physically connected to churches or basilicas, such as al-Bakhrā’ or Al-Rusạ̄fa (Guidetti 2013, 2016). All these diverse cases show contacts between Muslim and Christian communities, where “Muslims found an accommodation for their worships within Christian buildings” (Guidetti 2013, p. 251). His argumentation and results consider that “the conversion of Christian buildings into mosques was unlikely”, being also “evident that the conversion of churches into mosques was by no means the rule in the early periods of Islam” (Guidetti 2016, p. 25)” He also dismisses the “partition of a Christian church by Muslims and Christians” (Guidetti 2016, p. 25).

In view of the foregoing, the existing contradiction between written sources claiming for the systematic and conscious destruction of Christian places of worship and the material reality perhaps should be interpreted, again, as the Arab authors’ wishes to create a specific narrative of fervorous exaltation of Islam (Calvo 2007, p. 159-ff.; 2020, p. 31).

4. Umayyad Mosques in Urban Landscape

Given the lack of material remains of mosques that can be dated before the Umayyad period in the Iberian Peninsula, the study of how and where mosques were first built in urban contexts in al-Andalus must begin with the arrival of ‘Abd al-Raḥmān I to the Iberian Peninsula. This meant substantial changes for the history of al-Andalus and for its configuration as a centralized state ruled from Córdoba. In this configuration, cities -in general, and Córdoba in particular—were of paramount importance, for which the Umayyad dynasty carefully designed and executed very particular urban projects that involved, in many cases, the foundation of mosques, and that aimed to contribute to the Islamization of the landscape and the inhabitants of cities. Once again, the mosque of Córdoba is the most evident example of these ideas.

4.1. The Friday Mosque of Córdoba

Regarding its materiality, and as previously noted, barely anything is known about the Muslim occupation of this sector before the first Umayyad mosque was built under the command of ‘Abd al-Raḥmān I. This emir sought political independence from the Abbasid Caliphate of the East and aimed to turn al-Andalus into a State itself. Pursuing these objectives, he began a policy of pacification but also of subjugation to his authority that would be followed by his successors. It intended to centralise the control of the Andalusi territory from Madīnat Qurṭuba and to seek physical embodiment of the continuity with the Umayyad caliphs of Damascus (Kennedy 2014, pp. 31–33). All this found strong reflection on the image and configuration of Qurṭuba as capital, which was thoroughly transformed, becoming a tool for the development of the policies of Islamization, Arabization and legitimisation of the dynasty.

In this context, the Great Mosque of Córdoba appeared at the end of ‘Abd al-Raḥmān I’s rule, by the year 785, and not upon his arrival in al-Andalus thirty years earlier. The reasons for this “delay” directly relate with the final organization and consolidation of Umayyad power, its State and the need to create a physical manifestation for it (Souto 2009, p. 21; Calvo 2009, p. 89; Viguera 2022, pp. 373, 378). In this regard, the Umayyad emirs designed an urban project in which the erection of the Friday mosque in the southern sector of the madīnat, on the same area where the late-antique religious complex had stood before8. This became one fundamental axis of action together with the creation of the State’s management infrastructure and the organization of vast suburban areas (see Murillo et al. 2004). Thus, such magnificent building was only materialized once the emiral power had been sufficiently consolidated, the territory pacified, and the authority of ‘Abd al-Raḥmān widely recognized.

In general terms, the Friday Mosque congregated the community for Friday noon prayers and was a physical reflection of the religious component that imbues the Islamic culture. The mosque would allow Qurṭuba to achieve a better cohesion and unity of the community of believers. At the same time, it was the place were political and religious power could converge, and as such it also became a strategical display of dynastic propaganda. Even though these aspects could be applied to many other Friday mosques in the Dar al-Islam, the Great Mosque of Qurṭuba was erected with marked differences with respect to other major mosques.9 The first particularity relates to its meaning as a new architectural religious type. Even though this was not the first mosque ever to be built in al-Andalus (see Calvo 2007) and, as we will see, will not be the only one in Qurṭuba either, a building like this had never been erected before in the Iberian Peninsula. Its conception and materialization can only be understood, as Manzano (2006, pp. 125–26, 216–18) reminds us, from an Islamic perspective, which gives sense to its design and ultimate existence. This way, the mosque was not only destined to gather the community of believers -which would have been minimal by these moments—and to provide religious service to the population, but to make the presence of the authority palpable and visible in the city and its territory.

This intertwining with political displays, which is reinforced by the architectural and artistic solutions chosen for this mosque that combine local and Syrian typologies and traditions10, leads to a second aspect to consider: the role of this mosque in the dynastic architectural language developed by the Umayyad dynasty. This monumental construction only appeared at the end of the 8th century. As stated, there had been other mosques built before. Their architectural appearance is so far unknown to us, but the available information does not allow us to suggest that they were as monumental as this one. The Great Mosque shows a masterful and unique combination of different autochthonous, oriental and newly created forms and styles and became a cornerstone in the Umayyad building programmes, as well as the principal reflection of the dynasty’s power. A manifestation of this enormous excellence was somehow unexpected, as there was a clear lack of precedents in the West for such a construction, which held an enormous symbolic load (Manzano 2006, pp. 214–24). As argued by many colleagues, this architectural blooming was directly related to the Umayyads and their dynastic conception, which led to a carefully planned programme of refurbishments and enlargements that aimed to showcase the new government, its origin and, to a certain extent, its intentions.

The final aspect relates to the location of the mosque and its role in the scenery of the city. The mosque stands on a plinth that raises it more than three meters above the adjacent streets, dominating the entire urban landscape around it (see Figure 2). This elevated position was further reinforced by the building’s external appearance, similar to a fortification. It was located at the entrance of the city from the south, over the previous late-antique episcopal complex. Such confluence of factors was a manifestation of strength that had not been seen in Cordoba for many centuries (Manzano 2006, p. 217). The mosque was also located opposite the eastern facade of the Alcázar, main residence and seat of the new Muslim government. This created a physical, monumental urban binomial of power that reproduced in al-Andalus an Eastern scheme and that was based on the composition of the previous late-antique city too (see Figure 3).

Figure 2.

View of the Cathedral-Mosque of Córdoba today and the plinth where it stands (picture by Cabildo Catedral of Córdoba, used with permission).

Figure 3.

Topographical relationship between the Alcázar and the mosque, located in the south western corner of the madīnat (see the black star on the general map provided up-right). (A): location of the late-antique civil palace and episcopal complexes. (B): location of the emiral Alcázar and mosque (in León and Murillo 2009, 405 fig. 2 and 420 fig. 6, reproduced with permission).

4.2. Other Umayyad Mosques and the Display of the Authority

Apart from the exceptionality of Córdoba, there is not a high number of Friday mosques documented in al-Andalus, and more specially for the emiral period. Very often no more is known apart from just a few architectural details and their former location, frequently where the later Cathedral was configured11. This might be partially caused to the difficulties in currently identifying them from a material viewpoint, since plenty of them were transformed into cathedrals after the Christian conquest, and few traces of the former Islamic building survive or can be documented today without proper urban interventions. Despite this fact, the cases that can actually be examined are scarce but quite suggestive. Re-taking Zaragoza’s example, its Friday mosque was erected without any relationship with previous religious late-antique constructions, on an empty spot of the former Roman forum (Bienes et al. 1996–1997; Hernández Vera 2004). This confirms the non-destruction of any previous religious site, as well as points towards the intention to occupy and perhaps reactivate relevant urban spots of the former city.

Likewise, the Ibn ‘Adabbās Friday mosque of Seville (Torres Balbás 1946; Valor 1993; Cómez 1994) was turned into the San Salvador collegiate church after the Christian conquest, which complicates the archaeological and architectural approach to the former Islamic building. As stated on its foundational inscription, this mosque was also founded directly by an Umayyad emir:

“God have mercy on ‘Abd al-Raḥmān b. al-Ḥakam, the righteous emir, the rightly guided by God, the one who ordered the construction of this mosque, under the direction of ‘Umar b. ‘Adabbās, cadi of Seville, in the year 214 [ca. 829–830] and [this] is written by ‘Abd al-Barr b. Hārūn”12.

According to M. Tabales and M. Alba, the historiographical tradition that believed that the Roman-Christian and even Visigothic religious buildings of the city were located underneath the later mosque could never be confirmed archaeologically, since the excavations carried out could only detect quite late fillings without further structural evidence. As they point out, even though perhaps more excavations on this area are needed to confirm or discard that a previous cathedral or Roman forum existed on this area before the mosque, “the structural disconnection between the Islamic building and its possible precedents is more than evident” (Tabales and Alba 2015, p. 308). The foundation of this mosque seemed to participate of a process of regression and progressive abandonment of the late-antique city that would have leaded to the occupation and vivification of empty areas (Tabales and Alba 2015, p. 303). Shortly after its foundation, written sources speak about the configuration of the Dār al-Imāra close to this mosque, and about the saturation of the surroundings by shops and commercial areas and activities (Tabales and Alba 2015, pp. 313–14).

According to these authors, the surroundings of the first Friday mosque in Sevilla hosted very important commercial and trading activities that are difficult to document from a material viewpoint, but that were surely stimulated by the presence of this religious equipment. Tabales and Alba indicate that the spaces for the main trading activities in the city, such as the sūq and the main market, were located nearby Ibn ‘Adabbās, to an extent that even some of the small shops and trading spaces attached to the mosque were fossilized there until today Tabales and Alba 2015, 319). The rearrangement and reoccupation of such important areas and the reorganization of paramount activities like these probably did not depend on particulars or on regular people but was a prerogative of the authorities. The fact that the Ibn ‘Adabbās mosque was a direct foundation of the emir ‘Abd al-Raḥmān II builds towards this idea.

At this respect, written sources mention the construction of some other Friday mosques during the emirate, but they do not describe this as a generalized phenomenon. Only by the ninth century and, specifically, under the rules of Muḥammad I and ‘Abd al-Raḥmān II, the number of Friday mosques increased. Under the rule of this last emir, chronicles emphasize the foundation of Friday mosques in Badajoz, Málaga or Jaén, among others. According to Calvo, these foundations in the core of cities served the emirs to reinforce their authority and to reorganize the administration of the State (Calvo 2009, p. 89). Furthermore, emiral Friday mosques acted as a tool for sedentarization, islamization and Arabization in cultural, social and religious terms (see Calvo 2014, pp. 62–74). The combination of this written information with the scarcity perceived through the materials available suggest that the emergence of Friday mosques in al-Andalus during the Umayyad emirate was not a systematic dynamic, but an activity linked to power, directly sponsored, surveyed or decided by the emirs, but not the first and immediate priority when (re)arranging a city.

A similar circumstance has been detected in other cities of the Bilād al-Shām. Many of the mosques archaeologically surveyed from the Umayyad period were first built in relation to former very relevant and active areas of cities, such as trade areas—Palmyre (Genequand 2008; 2012, p. 52-ff.), Jerash (Guidetti 2016, p. 64), Rusafa (Guidetti 2016, p. 65) or Amman (Arce 2002), among others—or administrative spaces -Tiberiades (Cytryn-Silverman 2009). The existence of these insertion patterns in different cities testifies, according to D. Genequand (2008, p. 14), ‘to the involvement of the Umayyad Marwanid caliphs in large-scale urban development or refurbishment’, since ‘only a strong political power was able to impose this kind of modification to the urban core of large cities or to create new ones, and was able to make the necessary investments. Mosques were linked to the affirmation of a new religion and a new political power. Markets were linked to economic growth. Nevertheless, one may wonder if these latter should be interpreted as proof of a still thriving and continuous economic life in Bilād al-Shām or as an attempt by the new rulers to revitalize a declining economy’.

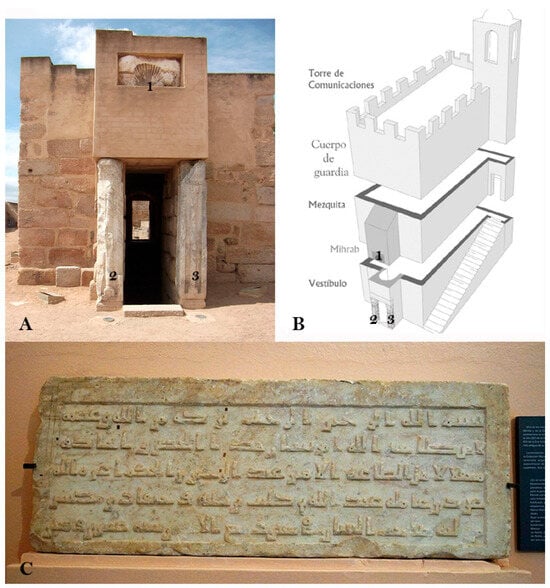

4.3. The Use of Spolia

Together with the previous examples, there are other cases that reinforce the hypothesis of mosques serving not only as a worship place for the Muslim community, but as scenario or public display for the Umayyad dynasty and its achievements on this side of the Mediterranean. One of them is located in Mérida. Here, by the bank of the Guadiana River, a fortress-alcazaba-was erected in emiral times (see Figure 4). According to its foundational inscription (see Figure 4C), this was a fortified enclosure commanded by the emir ‘Abd al-Raḥmān II, conceived as a key piece to implement the emiral power in the city (Feijoo and Alba 2005, p. 566):

Figure 4.

Possible mosque in the Alcazaba of Mérida. (A): front view of the mosque-cistern with indication of the spolia mentioned in the text (Creative Commons, indications of spolia by author). (B): diagram of the mosque-cistern-signal tower with indication of the spolia mentioned in the text (original image from Feijoo and Alba 2005, p. 576, fig. 18, reproduced with permission, indications of spolia by author). (C): foundational inscription of the building (Creative Commons).

“In the name of God, the Clement, the Merciful. Blessing of God and his protection for those who obey. The emir ‘Abd al-Raḥmān, son of al-Ḥakam—God glorify him—commanded to build this fortress and to make use of it as shelter for his obedients, through his ‘āmil ‘Abd Allāh, son of Kulayb b. Tha’laba, and Hayqār b. Mukabbis, his mawlà, and sāhib al-bunyān, in the moon of postrer rabi’ of the year two hundred and twenty [=April 835]”13

Specifically, this complex aimed to control the bridge and the access to the city, to serve as residence for the obedient and allies of the emir in times of instabilities, and to protect the governors named from Córdoba (Valdés 1995; Franco 2020, pp. 122, 132). One very particular and representative element in this Alcazaba is a monumental cistern that was covered with a building that has been interpreted as a mosque. Provided with a minaret, the complex would have served as signal tower as well (Feijoo and Alba 2005; see Figure 3B). This cistern and the possible mosque show a significant use of spolia. These reused pieces, of Roman and Visigothic origins, were carefully selected, arranged and displayed because they were meant to be shown: Visigothic pilasters at the main exterior entrance, as well as at the lintels and stairs of the underground cistern; Roman marble pieces in the corridors and vault; and a marble scallop indicating the place for the mihrab to the exterior (see Figure 4A) (Franco 2020, pp. 77–79; see Figure 4A,B). According to B. Franco, this display evidences a clear symbolism of power legitimization and subjugation of the defeated (Franco 2020, p. 76).

This use of spolia is not anecdotic: it became a common practice in the design, configuration and final materialization of religious spaces in the early al-Andalus, in the Syrian region and North Africa first, and in al-Andalus later on. The most iconic Umayyad mosques located in these areas, both Friday ones and the ones belonging to quṣūr, counted on spolia dating from Classical and Late Antique times-Jerusalem, Damascus, Aleppo, al-Bakhra’, Qasr al Hayr al-Sharqi, Qayrawan or Córdoba, just to quote a few of them (see Guidetti 2016, pp. 97–132; Genequand 2012; Souto 2009; González Gutiérrez 2022). This reuse of materials has been often interpreted as proof of the need for building materials—and particularly marble pieces—to design these new monuments. However, surely these pragmatic and economic factors were combined with deliberate uses.

Numerous written sources transmit that several capitals possibly coming from the “Nea church” served for erecting the al-Aqsa mosque (Guidetti 2016, p. 100); that columns from a specific church in Antioch were translated for the construction of the Damascus mosque (Guidetti 2016, p. 114); that the mosque of Aleppo held materials brought from the church of Cyrrhus, sited 70 km from it (Guidetti 2016, p. 116); or that very specific columns from a Greek church served to ornament the mosque of Qayrawan (Guidetti 2016, p. 117). Although these accounts cannot be taken as a faithful reflection of the historical reality, the emphasis made in underlining the Christian affiliation of these elements, and the preference for the ones coming from churches, may be understood as the desire for the use of particular architectural materials, not just all materials in general, which were loaded with very specific meanings. Archaeological evidence points towards the same ideas. As explained for the case of Mérida, Roman and late-antique pieces were not only used as a mere building resource, but as elements to be exhibited. Perhaps the most eloquent example in this regard is the foundational phase of the Great Mosque of Córdoba, where all the bases, shafts, capitals and cymas are pre-Islamic and were used to support the aisles and the series of arches in the prayer room.

These materials, carefully and rigorously studied over the years14, were not arranged arbitrarily. In the foundational mosque, the most prominent materials are mainly concentrated around the main accesses, the central aisle and along the qibla wall (Cressier 1984, pp. 236–70)15. The disposition of shafts and capitals in pairs in the central aisle seems to try to configure a sort of via triumphalis to emphasize the path that the emirs would follow to reach the area in front of the miḥrab before the sābāt was built (Souto 2009; Cressier 1984). Recent works centered on the shafts point towards the same direction (Hidalgo and Ortiz-Cordero 2020). J. A. Souto suggests a sort of monumentalization for this central aisle as a metaphor that would stand for the centralized state that the Umayyads were then trying to configure in al-Andalus (Souto 2009, p. 34).

All in all, it is clear that the use of spolia in the erection of new mosques required locating, transporting, re-carving and rearranging all these pieces harmoniously. These complex tasks were surely expensive and required the existence of specialized workforce and, specially, of an authority in charge of monitoring and directing the whole process. Considering this, the large scale of the use of spolia phenomenon, which was not an isolated practice, is only well explained when inserted into the policies of legitimization and Islamization developed by the authorities (the Umayyad caliphs in the East first, and the Umayyad emirs in al-Andalus later, see González Gutiérrez 2022). By using and displaying these rich materials they aimed to connect themselves with previous imperial traditions, as well as to fulfil their desire and necessity to show and demonstrate their power and prestige in the new conquered places. In this context, the use of spolia emphasises the hypothesis that the conception of certain mosques responded not only to a religious need, but to the wish of the authorities to make themselves visible in the urban landscape and through architecture.

5. Other Mosques in Urban Landscapes: Secondary or Neighbourhood Mosques

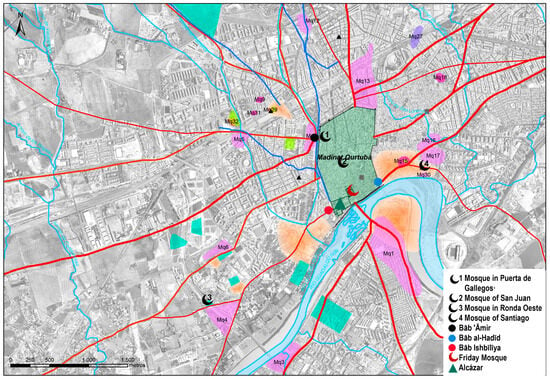

As explained above, the preceding examples could be read as tools for the Umayyad emirs to physically emphasize their settlement and stabilization in certain cities. During the emirate, if not earlier, Friday mosques played a paramount role in the monumental building programs established from the top to promote the Islamization of the territory and in the propaganda agenda of the Umayyad dynasty. Perhaps one more issue that arises at this point is: did other minor or secondary mosques behave in favour of the central power, similarly to the Friday ones, or aside from it? Given the scarce number of secondary mosques documented in al-Andalus within their urban contexts, providing a general answer to this question is not within reach yet. Fortunately, some light can be thrown from Córdoba, where the number of mosques documented other than the Great one is significantly high (López and Valdivieso 2001; González Gutiérrez 2016, 2018, 2020).

For the emiral period, written sources mention plenty of foundations sponsored by the emirs, their wives and concubines, other members of the Umayyad family and certain characters close to them (see González Gutiérrez 2020). The majority were mosques situated in the different suburban areas, as well as in the madīnat. These accounts disclose the desire of the emirs to provide the city with very specific facilities that clearly relate to Muslim habits and practices. These services would transform the city landscape at the same time as they would allow, facilitate or encourage determined lifestyles and uses. Hitherto, archaeology has only documented four possible emiral mosques (Figure 5) whose detailed topographical analysis reveals that their settings and urban insertions do not seem casual or accidental, but the result of a pre-planned project.

Figure 5.

Map of the emiral Qurtuba with indication of the main urban elements mentioned in Section 4 (basis map Convenio GMU-UCO, reproduced with permission and modified by author).

One of these mosques is near the contemporary Puerta de Gallegos, formerly inside the city walls. The mosque was built next to the Bāb ‘Āmir, one of the gates that gave access to the madīnat from the west, and to the wall surrounding it. The construction of its minaret involved the invasion, albeit minimal, of the coastal path of this wall. Also, within the madīnat there was the mosque whose minaret survives today in the San Juan church. This mosque presided an open area or square and was located on a very important street that crossed the walled city and connected the aforementioned Bāb ‘Āmir with another city gate, the Bāb al-Hadīd sited in the Eastern wall (González Gutiérrez 2018, p. 10).

Remains of another mosque, known today as Ronda Oeste mosque, were founded in the western suburbs. It was inserted in a very wealthy and varied urban environment (Camacho and Valera 2018, 2019) which proves that all this sector experienced quite a remarkable urban dynamism in these early moments, before the following caliphal blossoming. The mosque, of modest dimensions, was quite far from the walled city and its gates, but it was built on a relevant historical path that connected Córdoba and Seville and which also led directly to the Bāb Ishbīlīya -and, consequently, to the Alcázar enclosure.

The last example, and perhaps the most eloquent one when tracing the role of these mosques in the Islamization of the city, is a mosque that was centuries later transformed into the church of Santiago. Built to the east of the walled city, Ocaña (1975, p. 36) suggested that this could have been the referred in the Umayyad chronicles as mosque of ‘Āmir Hišām, promoted directly by that emir at the end of the eighth century. Regardless this possible filiation, its location can be related with similar processes of Islamization: this neighbourhood was configured over the basis of a previous one of indigenous roots, mentioned in written sources as Šabulār quarter. This was an old late Roman and Late Antique vicus already urbanized and functioning at the time of the conquest, provided with a basilica and a cemetery. It extended from the Bāb al-Hadīd (Figure 5, blue spot), along a path of Roman origins flanked by a necropolis (Murillo et al. 2004, p. 262). The mosque, that was situated on one side of this path, would have been very visible for all the passersby and would have been perhaps a state or official foundation in this particular context, destined to favor Islamization in an area of vernacular roots.

The cited urban patterns that relate mosques with the city gates and important routes of communication and connection between the suburbs and the walled enclosure, were respected and implemented during caliphal times. Eventually, the introduction of mosques in the suburban landscape stimulated the appearance of new inhabited areas and contributed to the development of the city beyond the walls, which was one of the main axes of the Umayyad urban project (see Section 4.1). From the year 929 until the fall of the Umayyad caliphate in the first half of the eleventh century, Córdoba will experience an astonishing urban growth which responded, to a greater extent, to official building projects in which mosques continued to play a very prominent role. Their importance for the Islamization was combined with clear intents of affirmation of the Umayyad presence and predominance in the city through the monumentalization and visibility of these elements (see González Gutiérrez 2016, 2018). The existence of this policy of Umayyad proselytism—which is fully evident in the erection of the Friday mosque and, of course, in its subsequent enlargements-, relates to the need to ensure the militancy of the jāṣşa to the Umayyad regime as well. Mosques often constituted landmarks of the neighbourhoods they stood in, even borrowing their names to them, and became very abiding. Actually, at least two of the four examples described above -mosques of San Juan and Santiago—continued in use after the fitna that made the Caliphate collapse, eventually becoming churches with the Christian conquest, and their minarets still stand today converted as bell towers, as part of the city landscape.

6. Final Remarks

The information provided by written sources about how and when the first mosques of al-Andalus appeared in urban landscapes testifies that these buildings were a very powerful resource to create specific narratives of conquest and to consolidate an historiography about the origins of al-Andalus. According to these accounts, the earliest mosques were linked to very relevant characters and were paramount for the reconfiguration of cities’ religioscapes, where they substituted previous churches and managed to endure along the centuries. Even though Archaeology cannot ratify of all these data, plenty of which aimed to recreate particular topoi also shared with the Bilād al-Shām, the importance given to these mosques by the historiographical tradition indicates that mosques played a very important part on the official agenda. This importance is far more evident during the Umayyad emirate, where the first archaeological traces of mosques can be found, mainly framed in bigger and more conscious urban projects.

The cases attributed to this period show the intervention of the State behind the construction of many mosques. Their architectural features, locations, the use of spolia, the written narratives created to describe their origins, or the replication of certain foundational patterns existing in the Syrian region, among other details, point towards the fact that these mosques emerged to fulfil more than religious needs only. Through them, the Umayyad power manifested its triumph and hegemony in cities and could also encourage the social islamization on a wider sense, the sedentarization and, ultimately, urban life.

Córdoba is perhaps the most eloquent example of these dynamics. Here, the occupation and urbanization processes that progressively transformed the city and its suburban area into a big capital involved both the erection of the Friday mosque as part of the center of power and the organization of polynuclear sectors beyond the city walls that were arranged around specific facilities, often mosques. These secondary mosques encouraged the inhabitability of new areas, especially in zones further away from the Madinat, and the development of islamization policies as well. All these data support the existence of a pre-planned, or at least top-down, urban project. In light of the results emanated from Córdoba, the development of similar global landscape analyses in other Andalusi cities would certainly be of upmost interest to verify if the dynamics detected in the capital were also encouraged beyond it, simultaneously or later. This would involve, however, the uncovering of new material evidence -and perhaps the reassessment of the already existing—that can allow us to obtain a general vision of the appearance and relevance of mosques during the earliest moments of the Islamic presence in al-Andalus and during the Umayyad Emirate.

Nevertheless, very interesting issues remain still open. They mostly refer to the structure and function of mosques before Umayyad times: where are they, how were they, and why archaeology has not been able to identify them yet? At this respect, Calvo suggests that the earliest religious spaces configured in al-Andalus could have had a provisional nature and did not follow a regulated pattern until the establishment of the Great Mosque of Córdoba. According to her, we should assess if clear and regulated Islamization and urbanization processes existed or had already begun during or right after the Muslim conquest. If so, we ought to consider whether it necessarily entailed the erection of big or considerable hypostyle mosques in places under siege or very recently conquered (Calvo 2020, pp. 50–52). In any case, the recovery of further archaeological data in the future will contribute to clarify this view and to expand our global vision about the earliest mosques in al-Andalus.

Funding

This research was made within the research funding program “Línea de Ayudas para Captación, Incorporación y Movilidad de Capital Humano de I+D+i. Programa de Ayudas a la I+D+i, en Régimen de Concurrencia Competitiva en el Ámbito del Plan Andaluz de Investigación, Desarrollo e Innovación (PAIDI 2020)”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | See, for instance, (Bianquis 1988; Bloom 1989; Juez 1999; Behrens-Abouseif 2000; Souto 2004; Longhurst 2012), among others. |

| 2 | Interestingly, this casuistry is shared with the Bilād al-Shām, where pre-Umayyad mosques are still to be located and excavated. |

| 3 | Given this, Gutiérrez highlights very stimulating questions that are still to be answered: where did the people who inhabited this neighbourhood pray? Did they have a mosque or a specific venue for worship and, if so where was it situated? |

| 4 | See also https://fonspalol.icac.cat/el-bovalar/ (accessed on 20 October 2023). |

| 5 | Some aspects of this controversy are reflected and explained by Arce (2015), who offered a detailed overview of the contemporary state of the arts of the archaeological research in the former Great Mosque of Córdoba. He remarked the absence of evidence that could be related to the existence of Christian buildings previous to the Umayyad mosque, and therefore the impossibility for the Muslims to have occupied a previous basilica. Arce finishes his paper writing that “cualquier esclarecimiento sobre la historia de la aljama cordobesa deberá pasar por la puesta en marcha de nuevos acercamientos arqueológicos en un edificio con una enorme potencialidad apenas explotada más allá de las parciales exploraciones del siglo pasado. Tenemos amplias zonas nunca excavadas y contamos, además, con el propio edificio en pie que puede ser analizado en sus alzados según los mismos criterios metodológicos” (Arce 2015, p. 41). Fortunately, years after this paper was published, archaeological interventions are being developed in the Patio de los Naranjos that confirm the existence of an episcopal complex here (León and Ortiz 2023) and that invite us to review all this issue from new and very promising perspectives. |

| 6 | Nevertheless, the non-coetaneity of sources regarding the facts they narrate constitutes no reason to discard them, as they provide precious information about how discourses about the past are constructed to answer to different social and political circumstances (more about this in Elices and Manzano 2019). |

| 7 | R+D+i Project “De Iulius Caesar a los Reyes Católicos: análisis arqueológico de 1500 años de historia en la Mezquita-Catedral de Córdoba y su entorno urbano”, leaded by Prof. Alberto León and Prof. José Antonio Garriguet (DE IURE, Ref.: PID2020-117643GB-I00), granted by the Ministry of Science and Innovation, of the State Programs for Knowledge Generation and Scientific and Technological Strengthening of the R+D+i system, call 2020. |

| 8 | The terms and processes through which this space was occupied are not clear yet and are being heavily discussed. The ongoing archaeological interventions mentioned above, in the frame of the research project “DeIure” (see note 4) are to fresh information to the discussion. The relationship between churches or basilicas and new mosques in the earliest moments of Islam is detected in Bilād al-Shām too (see Guidetti 2016). |

| 9 | This building is considered the most emblematic architectural creation of the Umayyads of al-Andalus. Founded at the end of the eight century and the object of numerous subsequent enlargements and refurbishments by the hand of the following emirs and caliphs, it has received deep and tireless attention of research from many points of view and disciplines that have explored countless aspects of it. This paper is not the place to summarize all this information, which nevertheless deserves being mentioned. |

| 10 | See, among many others, (Flood 2001; Dodds 1992; Ewert 1987, 1995; Khoury 1996; Giese-Vogeli 2008; Souto 2009) and etcetera. |

| 11 | At this respect, the case of Granada might be illustrative, since the location and more general structure of its Friday mosque have been long discussed (see Torres Balbás 1945; Fernández Puertas 2004). |

| 12 | Translated from Arabic to Spanish by Ocaña (1947). The translation to English is mine. |

| 13 | Translated from Arabic to Spanish by Barceló (2004, p. 63). The translation to English is mine. |

| 14 | Ewert and Wisshak (1981); (Cressier 1991, 1985, 1984); Peña (2010) among others. For a general overview and compilation of these authors and their main hypotheses, see (González Gutiérrez 2022). |

| 15 | However, the importance and intensity on this arrangement differ from author to author (cf. Peña 2010, p. 163). |

References

- Arce, Fernando. 2015. La supuesta basílica de San Vicente en Córdoba: De mito histórico a obstinación historiográfica. Al-Qanṭara 36: 11–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arce, Ignacio. 2002. The Umayyad Congregational Mosque and the Souq Square Complex on the Amman Citadel: Architectural Features and Urban Significance. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Congress of the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East. Bolonia: University of Bolonia, vol. 2, pp. 121–42. [Google Scholar]

- Barceló, Carmen. 2004. Las inscripciones omeyas de la alcazaba de Mérida. Arqueología y Territorio Medieval 11: 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrens-Abouseif, Doris. 2000. La conception de la ville dans la pensée arabe du Moyen Âge. In Mégapoles méditerranéennes, géographie urbaine rétrospective, actes du colloque organisé par l’École française de Rome et la Maison méditerranéenne des sciences de l’homme (Rome, 8–11 mai 1996). Directed by Claude Nicolet, Robert Ilbert, and Jean-Charles Depaule. Paris: Maisonneuve et Larose, pp. 32–40. [Google Scholar]

- Beltrán, Julia. 2019. La Barcelona Visigoda: Un puente entre dos mundos. La Basílica dels Sants Just i Pastor: De la ciudad romana a la ciudad altomedieval, Studia Archeologiae Christianae 3. Barcelona: Ateneu Universitari Sant Pacia. [Google Scholar]

- Bertran, Prim, and Francesc Fité. 1986. El jaciment arqueològic de Santa Coloma d’Àger (província de Lleida). In I Congreso de Arqueología Medieval Española, vol. 2 tomo 2. Zaragoza: Diputación de Aragón, pp. 203–20. [Google Scholar]

- Bianquis, Thierry. 1988. Derrière qui prieras-tu, vendredi? Réflexion sur les espaces publics et privés dans la ville arabemédiévale. Bulletin d’Études Orientales 37–38: 7–21. [Google Scholar]

- Bienes, Juan José, Bernabé Cabañero Subiza, and José Antonio Hernández Vera. 1996–1997. La catedral románica de El Salvador de Zaragoza a la luz de los nuevos datos aportados por su excavación arqueológica. Artigrama: Revista del Departamento de Historia del Arte de la Universidad de Zaragoza 12: 315–34. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, Jonathan. 1989. Minaret: Symbol of Islam. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brufal, Jesús. 2018. Iglesias y necrópolis entre la Tardo-Antigüedad y la Alta Edad Media en el valle de Àger. Expresiones del ciclo de la vida. In El ciclo de la vida comarcal y su transgresión. Directed by Francisco A. Cardells-Martí. Coordinated by Noelia Gil Sabio. Valencia: Universidad Católica de Valencia, pp. 19–35. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo, Susana. 2007. Las primeras mezquitas de al-Andalus a través de las fuentes árabes (92/711-170/785). Al-Qantara 28: 143–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, Susana. 2009. Los símbolos de la autoridad emiral, (138/756-300/912): Las mezquitas aljamas como instrumento de islamización y espacio de representación. In De Hispalis a Isbiliya. Edited by Alfonso Jiménez and Eduardo Manzano. Sevilla: Aula Hernán Ruiz, pp. 87–110. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo, Susana. 2014. Las mezquitas de al-Andalus. Almería: Fundación Tufayl de Estudios Árabes. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo, Susana. 2020. Los inicios de la arquitectura religiosa en al-Andalus y su contexto islámico. Studia Historica. Historia Medieval 38: 29–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, Cristina, and Rafael Valera. 2018. Espacios domésticos en los arrabales occidentales de “Qurtuba”: Materiales y técnicas de edificación. Antiquitas 30: 115–65. [Google Scholar]

- Camacho, Cristina, and Rafael Valera. 2018. Espacios domésticos en los arrabales occidentales de “Qurtuba”: Tipos de viviendas, análisis y reconstrucción. Antiquitas 31: 59–92. [Google Scholar]

- Cómez, Rafael. 1994. Fragmentos de una mezquita sevillana: La aljama de Ibn Adabbas. Laboratorio de Arte: Revista del Departamento de Historia del Arte 7: 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cressier, Patrice. 1984. Les chapiteaux de la grande Mosquée de Cordoue (oratoires d’Abd ar-Rahman I et d’Abd ar-Rahman II) et la sculpture de chapiteaux à l’époque émirale. Premiére partie. Madrider Mitteilungen 25: 216–81. [Google Scholar]

- Cressier, Patrice. 1985. Les chapiteaux de la grande Mosquée de Cordoue (oratoires d’Abd ar-Rahman I et d’Abd ar-Rahman II) et la sculpture de chapiteaux à l’époque émirale. Seconde partie. Madrider Mitteilungen 26: 216–81. [Google Scholar]

- Cressier, Patrice. 1991. El renacimiento de la escultura de capiteles en la época emiral: Entre Occidente y Oriente. Cuadernos de Madīnat al-Zahrâ 3: 165–87. [Google Scholar]

- Cytryn-Silverman, Katia. 2009. The Umayyad Mosque of Tiberias. Muqarnas 26: 37–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, Jerrilyn. 1992. The Great Mosque of Córdoba. In al-Andalus: The Art of Islamic Spain. Edited by Jerrilyn Doods. Nueva York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, pp. 10–25. [Google Scholar]

- Elices, Jorge, and Eduardo Manzano. 2019. Uses of the Past in Early Medieval Iberia (Eighth-Tenth Centuries). Medieval Worlds 10: 87–106. [Google Scholar]

- Ewert, Christian. 1987. Tipología de la mezquita en Occidente: De los omeyas a los almohades. In Arqueología Medieval Española, Congreso Madrid 19–24 de enero de 1987, Tomo I: Ponencias. Comunidad de Madrid: Consejería de Cultura y Deportes, pp. 180–204. [Google Scholar]

- Ewert, Christian. 1995. La mezquita de Córdoba: Santuario modelo del occidente islámico. In La arquitectura del Islam occidental. Coordinated by Rafael Jesús López-Guzmán. Madrid: Lunwerg Editores, pp. 53–68. [Google Scholar]

- Ewert, Christian, and Jens-Peter Wisshak. 1981. Hirarchische Gliederungen westislamicher Betsäle des 8. bis 11. Jahrhunderts: Die Hauptmoscheen von Qairawan und Córdoba und ihre Bannkreis. In Forschungen zur almohadischen Moschee I. Edited by Christian Ewert. Mainz: Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Feijoo, Santiago, and Miguel Alba. 2005. El sentido de la Alcazaba emiral de Mérida: Su aljibe, mezquita y torre de señales. Mérida, Excavaciones Arqueológicas 8: 565–86. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Puertas, Antonio. 2004. La mezquita aljama de Granada. Miscelánea de Estudios Árabes y Hebraicos. Sección Árabe-Islam 53: 39–76. [Google Scholar]

- Flood, Finbarr Barry. 2001. The Great Mosque of Damascus: Studies on the Makings of an Umayyad Visual Culture. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, Bruno. 2020. La Kūra de Mārida: Poblamiento y territorio de una provincia de época Omeya en la frontera de al-Andalus. Serie: Ataecina colección de estudios históricos e la Lusitania, 11; Mérida: Instituto de Arqueología de Mérida. [Google Scholar]

- Genequand, Denis. 2008. An Early Islamic Mosque in Palmyra. Levant, The Journal of the Council for British Research in the Levant 40: 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genequand, Denis. 2012. Les établissements des élites omeyyades en Palmyrène et au Proche-Orient. Beyrouth: Institut Français du Proche-Orient. [Google Scholar]

- Giese-Vogeli, Francine. 2008. La mezquita mayor de Córdoba y Samarra. Anales de Arqueología Cordobesa 19: 277–92. [Google Scholar]

- González Gutiérrez, Carmen. 2016. Las mezquitas de la Córdoba islámica: Concepto, tipología y función urbana. Ph.D. thesis, University of Córdoba, Córdoba, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- González Gutiérrez, Carmen. 2018. The role and meaning of religious architecture in the Umayyad state: Secondary mosques. Arts Journal 7: 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Gutiérrez, Carmen. 2020. Mothers, male children and social prospects in al-Andalus: Approach proposal for the 10th century. In Mothering(s) and Religions: Normative Perspectives and Individual Appropriations. A Cross-Cultural and Interdisciplinary Approach from Antiquity to the Present. Edited by Giulia Pedrucci. Rome: Scienze e Lettere, pp. 65–85. [Google Scholar]

- González Gutiérrez, Carmen. 2022. Spolia and Umayyad mosques: Examples and meanings from Córdoba and Madinat al-Zahra. Journal of Islamic Archaeology 9: 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidetti, Mattia. 2013. The contiguity between churches and mosques inearly Islamic Bilād al-Shām. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 76: 229–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidetti, Mattia. 2016. In the Shadow of the Church: The Building of Mosques in Early Medieval Syria. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez, Sonia. 2002. De espacio religioso a espacio profano: Transformación del área urbana de la basílica del Tolmo de Minateda (Hellín, Albacete) en barrio islámico. In II Congreso de Historia de Albacete: Del 22 al 25 de Noviembre de 2000 vol. I Arqueología y Prehistoria. Edited by Rubí Sanz. Albacete: Instituto de Estudios Albacetenses “Don Juan Manuel”, pp. 307–16. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez, Sonia. 2004. La iglesia visigoda de El Tolmo de Minateda (Hellín, Albacete). Antigüedad y Cristianismo 21: 137–69. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez, Sonia. 2011. El reconocimiento arqueológico de la islamización: Una mirada desde al-Andalus. Zona Arqueológica 15: 189–210. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez, Sonia. 2012. La arqueología en la historia del temprano al-Andalus: Espacios sociales, cerámica e islamización. In Histoire et archéologie de l’Occident musulmán (VIIe-XVe siècles): Al-Andalus, Maghreb, Sicile. Coordinated by Philippe Sénac. Mirail: CNRS-Université de Toulouse-Le Mirail, pp. 33–66. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández Vera, José Antonio. 2004. La mezquita aljama de Zaragoza a la luz de la información arqueológica. Ilu. Revista de Ciencias de las Religiones Anejos 10: 65–91. [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo, Rafael Enriquez, and Rafael Ortiz-Cordero. 2020. The mosque-cathedral of Córdoba: Evidence of column organization during their first construction, 8th century A.D. Journal of Cultural Heritage 45: 215–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juez, Francisco. 1999. Símbolos del poder en la arquitectura de al-Andalus. Ph.D. thesis, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, Hugh. 2014. Muslim Spain and Portugal. A Political History of al-Andalus. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Khoury, Nuha N. 1996. The meaning of the Great Mosque of Córdoba in the tenth century. Muqarnas 13: 80–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León, Alberto, and Juan Francisco Murillo. 2009. El complejo civil tardoantiguo de Córdoba y su continuidad en el Alcázar omeya. Madrider Mitteilungen 50: 399–432. [Google Scholar]

- León, Alberto, and Raimundo Ortiz. 2023. El complejo episcopal de Córdoba: Nuevos datos arqueológicos. In Cambio de Era: Córdoba y el Mediterráneo cristiano, catálogo de la exposición. Córdoba: Ayuntamiento de Córdoba, pp. 169–73. [Google Scholar]

- Longhurst, Christopher. 2012. Theology of a mosque. The sacred inspiring form, function and design in Islamic Architecture. Lonaard Magazine 2: 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- López, Rosa, and Ana Valdivieso. 2001. Las mezquitas de barrio en Córdoba: Estado de la cuestión y nuevas líneas de investigación. Anales de Arqueología Cordobesa 12: 215–39. [Google Scholar]

- Manzano, Eduardo. 2006. Conquistadores, emires y califas: Los Omeyas y la formación de al-Andalus. Barcelona: Crítica. [Google Scholar]

- Marín, Manuela. 1981. Ṣaḥāba et Tābi’ūn dans al-Andalus: Histoire et légende. Studia Islamica 54: 5–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo, Juan Francisco, María Teresa Casal, and Elena Castro. 2004. Madinat Qurtuba. Aproximación al proceso de formación de la ciudad emiral y califal a partir de la información arqueológica. Cuadernos de Madinat al-Zahra 5: 257–90. [Google Scholar]

- Ocaña, Manuel. 1947. La inscripción fundacional de la mezquita de Ibn Adabbas en Sevilla. Al-Andalus 12: 145–51. [Google Scholar]

- Ocaña, Manuel. 1975. Córdoba Musulmana. In Córdoba. Colonia Romana, Corte de los califas, luz de Occidente. León: editorial Everest, pp. 24–47. [Google Scholar]

- Palol, Pere de. 1989. El Bovalar (Seròs el Segrià). Conjunt d’època cristiana i visigòtica. Lleida: Diputación de Lleida. [Google Scholar]

- Peña, Antonio. 2010. Estudio de la decoración arquitectónica romana y análisis del reaprovechamiento de material en la Mezquita Aljama de Córdoba. Córdoba: Universidad de Córdoba, Servicio de Publicaciones. [Google Scholar]

- Souto, Juan Antonio. 1989. Textos árabes relativos a la mezquita aljama de Zaragoza. Madrider Mitteilungen 30: 391–426. [Google Scholar]

- Souto, Juan Antonio. 2004. La mezquita: Definición de un espacio. Ilu. Revista de Ciencias de las Religiones. Anejos 10: 103–09. [Google Scholar]

- Souto, Juan Antonio. 2009. La mezquita aljama de Córdoba: De cómo Alandalús se hizo edificio. Zaragoza: Instituto de Estudios Islámicos y del Oriente Próximo. [Google Scholar]

- Tabales, Miguel Angel, and Margarita Alba. 2015. La ciudad sumergida. Arqueología y Paisaje Histórico urbano de la ciudad de Sevilla. Sevilla: Junta de Andalucía. [Google Scholar]

- Torres Balbás, Leopoldo. 1945. La mezquita mayor de Granada. Al-Andalus 10: 409–32. [Google Scholar]

- Torres Balbás, Leopoldo. 1946. La primitiva mezquita mayor de Sevilla. Al-Andalus 11: 425–39. [Google Scholar]

- Valdés, Fernando. 1995. El aljibe de la alcazaba de Mérida y la política omeya en el Occidente de al-Andalus. In Extremadura arqueológica V, homenaje a la Dra. Dª Milagro Gil Mascarell. Edited by Juan Javier Enríquez and Alonso Rodríguez. Cáceres: Universidad de Extremadura, Servicio de Publicaciones, pp. 279–300. [Google Scholar]

- Vallvé, Joaquín. 1967. Fuentes latinas de los geógrafos árabes. Al-Andalus 32: 241–60. [Google Scholar]

- Valor, Magdalena. 1993. La mezquita de Ibn Adabbas de Sevilla: Estado de la cuestión. Estudios de historia y de arqueología medievales 9: 299–314. [Google Scholar]

- Viguera, María Jesús. 2022. La mezquita de Córdoba en textos árabes: Antecedentes e inicios. Boletín de la Real Academia de la Historia de Córdoba 219: 365–91. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).