1. Introduction

“Decolonizing the mind” (

Ngugi 1986) is an ongoing task, even after 50 years or more of political independence on the African continent. This is particularly the case with respect to theological education, where norms and structures still follow faithfully the pattern, established in Europe and North America since the Reformation, and laid down as normative in the colonial era by the mission-founded churches (Anglican/Presbyterian/Methodist/Roman Catholic/Baptist, etc.). There is an ongoing need for new initiatives in theological curriculum development that offer an authentic connection with African issues and concerns that were missing from the inherited theological formation and enable theological institutions to break from the shackles of these, in so far as these have hitherto been understood to be normative, with developments on the African continent making such initiatives ever more urgent. This article describes and analyzes the pioneering approach of the Akrofi-Christaller Institute (ACI), an indigenous Ghanaian institution, and the process of implementation over the course of the past 25 years that has produced a successful, full-orbed and wide-ranging theological curriculum connecting with religious, cultural, social and inter-faith issues; it explores its appeal for the majority of students at all levels, as well the facilitating factors and the challenges on the journey.

First, for those who may not be familiar with the Akrofi-Christaller Institute of Theology, Mission and Culture, situated in Akropong-Akuapem, Ghana, a little background may be found helpful. The Institute is named after two great scholars of the Twi language—Johannes Gottlieb Christaller, the 19th century missionary of the Basel Mission who translated the Bible into Twi, gathered a collection of Twi proverbs and compiled a Twi dictionary, and Clement Anderson Akrofi, the 20th century linguist and educationist at the Presbyterian Training College, Akropong, who revised Christaller’s Bible translation, wrote a Twi grammar in Twi and compiled his own collection of Twi proverbs. ACI has been in existence for 36 years (established in 1987) and has been offering graduate degree programs since 1998. It is a private tertiary institution, registered as a company limited by guarantee with the status of a charity under the Ghana Companies Code. This means that governance is through an independent Council, with the Presbyterian Church of Ghana as the sole legal subscriber at present, tasked with holding the Institute to its own legally established objectives. This secures ACI from church interference while enabling an ongoing relationship. It has its own presidential charter, granted in 2005, after 7 years of degree validation by the University of Natal/Kwa-Zulu Natal. Its degree offerings are MA (Theology and Mission), a 10-month modular program, designed as a foundational theology degree with a practical focus for those with degrees in other fields, MTh (in two tracks: African Christianity/Bible Translation and Interpretation), and a PhD in Theology (offered in these two tracks). ACI has graduated 93 at the MTh level since 2000, 33 at the PhD level since 2003, and 388 students at the MA level since 2006. They came from 19 African countries, the USA, Canada, the UK, South Korea and Australia, and are drawn from a wide variety of denominations: Anglicans, Methodists, Baptists, Pentecostals and Charismatics, as well as Presbyterians. Council members and faculty also reflect this denominational range. ACI has a reputation for excellence in Ghana and was, for a long time, the only Ghanaian private tertiary institution accredited to award PhDs in Theology (see

G. M. Bediako 2013a, pp. 939–46;

2014, pp. 361–70). As a chartered institute, ACI is authorized to mentor other theological institutions and validate their degrees. At present, ACI is working with two such institutions.

What has been noted as unique about ACI is its distinctive curriculum, distinctive because of its holistic nature, embracing the three areas of theology, mission and culture, in each of its degree offerings. An entire curriculum at each level has been developed, which owes its inspiration to the desire to provide theological training that truly equips for mission and ministry and to engage deeply with the African context. Kwame Bediako was the visionary, catalyst and chief architect of its development, and he drew in others, colleagues based in Ghana, Kenya and South Africa initially, who were all members of the African Theological Fellowship (ATF) (

G. M. Bediako 2013b, pp. 947–55).

The ACI story, therefore, illustrates that at the heart of curriculum development that makes a difference, is vision—insight into what needs to change, why change is necessary and how that might be accomplished in a fleshing out of programs and courses. Curriculum design for theological education in Africa, as elsewhere, has to do with vision that is shared with others to the extent of being embodied in new structures, courses and programs, towards practical outcomes in applied theology, which help to advance the Kingdom of God.

2. Vision—Back Story

It may be helpful to concretize this by indicating briefly how what has happened in the emergence and life of ACI was not the product of abstract theologizing, but emerged through lived experience, a learning period spanning 20 years or more, reaching back as far as the 1970s. I highlight aspects of Kwame Bediako’s story as the backdrop to ACI’s story, in the hope that it may resonate with different aspects of readers’ experience and meditation with respect to curriculum design, and possibly suggest new lines of thought and action. The article is thus intended to be evocative rather than prescriptive.

The first breakthrough for him came in 1974, during conventional theological training at London Bible College (LBC, now London School of Theology, LST), when he attended the Lausanne Congress on World Evangelization. It marked his exposure to the emerging voices of non-Western evangelicals making a convincing case in a global forum for the necessity of engaging the Christian gospel with indigenous cultures. He caught the vision for training centers in gospel and culture engagement that would raise awareness in non-Western churches of the universal nature of the faith, which means that it may be articulated everywhere in local expressions that are all potentially equally valid. For God speaks into all cultures and therefore different cultural perspectives on Christian faith and expression are valid and matter, not merely for the local context but for the world church as a whole (for a later scholarly exposition of these ideas, see

Sanneh 1989).

The next year, he met Andrew Walls at a missions conference at LBC, which proved to be the start of a lifelong collegial relationship, and he learned to see Christian history in the light of the cultural shifts in its center of gravity, placing the contemporary church in the non-Western world in a

kairos moment for the gospel. It may not be widely realized the extent to which the Enlightenment world-view was mediated to churches of the southern continents through mission Christianity, with the result that the young churches came to exist in a cultural vacuum, as whole areas of African religion and culture became effectively off-limits for converts, with existential questions concerning spirituality dismissively consigned to the realm of “superstition”. (For a succinct exposition of salient Enlightenment tenets and their impact on the missionary movement and in Africa and African converts, see

Walls 2001, pp. 48–50). It forms the substance of Lamin Sanneh’s later work of critique in

Encountering the West, Christianity and the Global Cultural Process—the African Dimension (

Sanneh 1993). So what Walls was sharing at the conference in terms of the shifts in the center of gravity of Christianity and their implications were cutting-edge ideas at the time (mid-1970s), that is, affirmations of an authentic Christianity no longer beholden to forms now prevailing in the Western world (see also

Walls 1996). They provided the foundation for Bediako’s own meditation over the next ten years until the time came to establish such a center in Ghana in the mid-1980s, and they were translated first into mission and culture training programs for church and para-church workers in Ghana.

A further key element of the back story, related specifically to curriculum development, which would be acted on in the mid-1990s, was exposure to curriculum innovation in the Department of Religious Studies and the Centre for the Study of Christianity in the Non-Western World (CSCNWW), in the University of Aberdeen (1978–1984), which were recently added structures within the University of Aberdeen (1970 and 1982, respectively). In the present era of a plethora of departments of religious studies and the increasing fashion for research projects and courses in World Christianity, we may not realize just how recent such structures are. Andrew Walls was invited by the university to establish the Department of Religious Studies, in view of the need for the increasing number of students of secular orientation, training to be teachers, who needed to understand the phenomenon of religion, as well as an increasingly pluralist environment. This marked a distinct departure from the venerable Faculty of Divinity, and offered radically new courses in primal religions, African Christianity, New Religious Movements, Phenomenology of Religion, etc., foregrounding non-Western concerns and subjects. In other words, the Aberdeen Centre was a good example of innovation within a well-established institution, as a center for research specifically aimed at directing the attention of non-Western students within the Western environment to the possibility of researching new areas and comprising a group of like-minded faculties working together (

Burrows et al. 2011, chap. 1, 4, 5).

After Kwame Bediako had returned to Ghana in the mid-1980s, there followed the establishment of the Akrofi-Christaller Memorial Centre for Mission Research and Applied Theology, ACI’s first name, which initially offered mission-focused, gospel and culture training programs for the Presbyterian Church of Ghana, broadening gradually to serve more ecumenically. The focus was on training church personnel and church members to be more contextually rooted and mission-minded. Yet the research preparation for, and learning from, grassroots interactions became foundational for shaping the later curriculum. A discovery here was that operating more intentionally in indigenous languages, people’s mother tongues, their heart language, was crucial for Christian nurture in depth, and that the mother-tongue Scriptures afforded fresh theological insights, especially through lines of connection with indigenous culture, that were key to personal and cultural transformation.

3. Opportunity

After 10 years, in the mid-1990s, the Board of Trustees felt it would be a natural development and consolidation to begin to offer accredited studies. This raised the question as to how a research and training center could be converted into a degree-awarding institution. Providentially, there had also been within the African Theological Fellowship network a desire to feed the learning from network interactions into theological training and curriculum development. This was part of the ferment going on in the wider network of Two-Thirds World theologians, International Fellowship of Evangelical Mission Theologians (INFEMIT) now known as the International Fellowship of Mission Theologians (see

https://infemit.org for details, accessed on 17 August 2023). The ATF held a series of curriculum development workshops in Ghana on behalf of the West African sub-region in 1996, in which East and Southern African members participated and the vision and rationale for curriculum redesign were shared. The idea was both to sensitize theological educators as to the need for it and also to invite participation in the redesigning project.

At the same time, South African university institutions were under pressure to Africanize their curricula in the immediate post-apartheid era. The School of Theology, University of Natal, Pietermaritzburg, was one such and had come to acknowledge that they did not have the expertise to do it. Hence, when a South African member of the ATF, who was the principal of ETHOS (Evangelical Theological House of Studies), loosely affiliated to the SoT, arranged a meeting between SoT and ATF, it proved to be a providential coming together that resulted in the ATF Master of Theology degree in African Christianity, with ACMC as the facilitating partner institution, one semester of the first-year coursework being held in each institution. With scholarship support from one of ACMC’s partner churches, for six years from 1998, the UN, later the University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN), validated the degree, while in Ghana the National Accreditation Board provided the necessary local accreditation. The PhD program started the following year in 1999. In 2005, ACMC was sufficiently well established to be granted its own charter. Its name changed to reflect this, and ACI continued offering the degrees independently of UKZN. The MA (Theology and Mission), which sought to offer similar courses and insights at a foundational degree level, targeting graduate professionals active in church work, was then added. This independence providentially secured ACI from the changes brought about by the merger of the University of Natal with the University of Durban-Westville, which had the side effect of demoting theology and theological methods in favor of religious studies and social science methodology. This shift was symbolically captured in the change in name from “School of Theology” to “School of Religion and Theology”, with Religion placed first, and even later to “School of Religion, Philosophy and Classics”. To Kwame Bediako, the initial name change was reflective of a trend he observed more generally:

… the study of ‘religion’, what religious persons are perceived to do and the theories that are developed from such observations, has been fundamentally split from the study of ‘theology’, the intellectual discipline that helps the understanding of how religious persons actually live’.

The objectives of the MTh in African Christianity were articulated as follows:

To provide opportunity for understanding the significance of African Christianity.

To enable graduates from African countries to undertake an advanced study of Christianity directly related to their own setting.

To provide opportunity for graduate Christian workers, lay or ordained, committed to ministry in cross-cultural situations, to examine the historical, religious and cultural context in which they operate and to reflect theologically on their experience.

To help prospective candidates of theological research involving cross-cultural or inter-religious study who do not have specialized training in these fields, to bridge the gap between previous academic study and the new material.

In other words, the MTh/PhD initial curriculum presupposed a first theological or religious studies degree in the traditional mode and was intended to “bridge the gap between the previous study and the new material”, making theological formation thereby more relevant to the context, and so to give candidates the tools to address the existential questions they would face in ministry. The one-year coursework embodied these objectives. For example, “cultural relevance in exegesis and interpretation” included the study of the Bible in indigenous languages. The initial curriculum was thus the work of the ATF and ACI faculty, under the leadership of Kwame Bediako, with Kenyan and South African colleagues assisting with respect to East and Southern African concerns, and with the financial support of key outside funders, who had caught the vision and desired to assist the degree’s progress.

The MA program, which came seven years later, was a distillation of the essential features of the MTh curriculum in a foundational theological degree that approached the recognized historic disciplines of biblical studies, Christian history, historical theology, Christian doctrine and ethics, and inter-religious engagement from African perspectives and with a mission focus. The objectives outlined in the Handbook reflect this focus:

To provide a basic introduction to the range of theological disciplines for graduates from other fields of study who desire theological training to equip them for lay Christian ministry.

To provide a recognised bridging program into the MTh in African Christianity.

To give an exposure to the intellectual rigour required for the study of the theology as an academic discipline.

ACI has since expanded the options within these three programs, in response to new needs and challenges.

4. Vision—Fundamental Pillars

The vision that inspired Kwame Bediako emerged from a conviction that African Christians were privileged to be in a

kairos moment in Christian history. He illustrated this in five theses (

K. Bediako 1995b, pp. 51–67). If Africa is now a heartland of Christian faith, then a “positive affirmation of the significance of African Christianity and not merely an African reaction against the West” (

K. Bediako 1996, p. 3) should be the motive for curriculum development. Setting the development of new curricula in theological education in Africa in the context of the present “shift in the centre of gravity of Christianity” (

Walls 1998, p. 2), Bediako saw what was happening was merely in line with the latest shift, and therefore as “not a triumphalist concept…but a matter of historical understanding” (

K. Bediako 2001, p. 29). The present shift to “new centres of Christian vitality [has] a cultural significance” in that “new cultural perspectives are part of the evidence of Christian vitality” (

K. Bediako 2006a, p. 4) It is a shift “to a cultural world that is more noticeably religious” (

K. Bediako 2006a, p. 5), with whose religious world and indigenous knowledge systems the world of the Bible is perceived to have an affinity (

K. Bediako 2006a, p. 5). For this reason, “theological scholarship ‘needs to engage with cultural issues on indigenous terms” (

K. Bediako 2006a, p. 5).

What then might be the implications for our scholarship? African indigenous knowledge systems operate within a world-view in which to live is to be connected to the Transcendent and to people—the living, the living dead and those yet to come. Might this be part of the explanation why so much of our African Christianity seems to live beyond the Enlightenment frame and seems not to wait for verification by Enlightenment procedures? … A theology that is boxed in by Enlightenment doubts, and which is suspicious of the transcendent world, is therefore not likely to thrive in Africa …’.

Hence, there was a need for a new kind of theological formation. He believed, along with others in the ATF, that theological education in Africa was in crisis. The curricula on offer did not equip Christian leaders for their present task, in that “they appear not to connect with the redeeming, transforming activity of the Living God in the African setting, and so are ineffectual in equipping God’s people for mission and for the transformation of African society” (

K. Bediako 2001, p. 29;

2006b, pp. 43–48).

By equipping for mission and transformation, he meant:

theological education in Africa ought to be about producing persons able to make an impact for the gospel both in the African context and in the wider world, … able to be at home anywhere in God’s world, who are liberated by being in Christ and so are not driven by purely reactive impulses, … who understand that African traditional religion is Africa’s old religion and that Christianity is Africa’s new religion, capable of reinterpreting the past, clarifying the present and shaping the future of our continent.

He also meant that theological education should “[make] us holy people”. This is one reason why the ancient African vision and model of theological education was so important to him,

where the whole focus was the training of the person to make one Christ-like, to bring one into union with Christ, the Master. Whether it was Anthony or Pachomius in the Egyptian desert, or Pantaenus, Clement or Origen in the catechetical school of Alexandria, the model of theological formation was the quest for holiness and moral transformation within the student who would then also become a model for others seeking their own liberation.

The vision fed into a “basic framework for shaping a curriculum”, which had originated in an INFEMIT curriculum development workshop held at the Oxford Centre for Mission Studies in the early 1990s (on OCMS, see

Samuel and Sugden 1999;

Sugden 1997, chap. 10–12; also

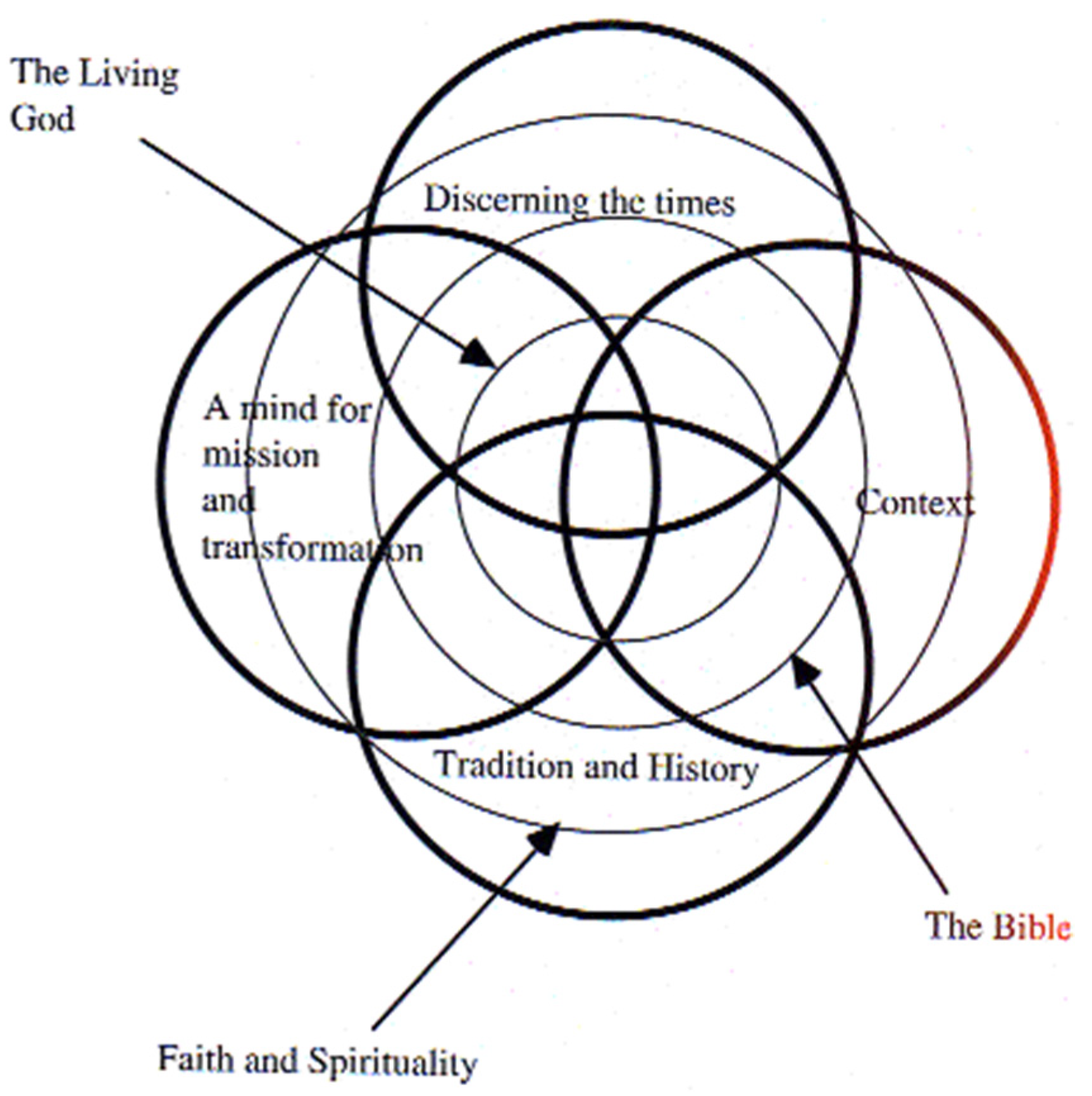

https://www.ocms.ac.uk, accessed on 17 August 2023). Bediako subsequently developed and used his framework at several ATF workshops in the 1990s. The framework captured by this Venn diagram underlies the ACI curriculum and indeed constitutes the overarching interpretative framework for research. It should be seen as, in effect, a theological indigenous methodology, comparable to work being completed by indigenous researchers in the social sciences (

Smith 2012). The introductory lectures in the course of research methods for MTh and PhD students examine it. For it was intended “to provide helpful categories for understanding, interpreting and critiquing what is there on the ground, as a basis for building a theological curriculum that takes seriously these African realities and equips for mission and ministry in our contemporary context” (

K. Bediako 2001, p. 30).

5. Basic Framework for Shaping a Curriculum (K. Bediako 2001, p. 30)

Figure 1 below is a diagrammatic representation of the basic framework for shaping a curriculum as expounded by Kwame Bediako.

5.1. Discerning the Times

Kwame Bediako selected this conceptual circle in

Figure 1 as a “point of departure”, namely, a discernment of “what God is doing in the world”, in which Africa has a significant role as a new heartland of the Christian faith. This is crucial, he observed, for avoiding “[falling] victim to the secular and reductionist, largely western, view of the world” (

K. Bediako 2001, p. 30) that excludes from its thinking Africa and its realities:

The real harm that the Enlightenment has done, has been to separate knowledge from character, intellectual development from spiritual growth, and, therefore, to produce scholars and intellectuals, theologically trained people, who are left morally weak because they have not been taken through the disciplines of being changed. The theory of knowledge on which they have been brought up is not holistic and does not produce integral development.

The traditional African world-view is a spiritual one, in which God, spirits both benign and malevolent, and ancestors impinge directly on human life and this outlook continues in the 21st century, not merely among traditionalists, but among educated people, who hold a spiritual world-view alongside modernity (

K. Bediako 1995a, chap. 6 and 12). “New knowledge in science and technology has been embraced, but it has not displaced the basic view that the whole universe in which human existence takes place is fundamentally spiritual” (

K. Bediako 1995a, p. 176). There is no dichotomy between sacred and secular, as in the Enlightenment thought mediated to Africa.

Alongside this affirmation of Africa’s place and the new responsibilities for the gospel it entails, was his recognition of its correlate: the recession of Christian faith among the peoples of the Western world, previously presumed to be Christian. For if the “fundamental basis of theological creativity” is a “sense of confidence in the gospel of Jesus Christ, as what interprets [Africans] and gives them their own identity” (

K. Bediako 2001, p. 30), as well as a judicious awareness of their calling in Christ’s mission in the world, it falls to African and other non-Western Christian scholars to rescue the theological academy from the grip of secularization for the sake of the health of the world church.

5.2. History and Tradition

A necessary follow-on element in discerning the times is given in the conceptual circle of

Figure 1 immediately below it and overlapping: “[connecting] with wider Christian history and tradition” in the “quest for possible analogues and variants” (

K. Bediako 2001, p. 30) in the unfolding of Christian history as a whole (e.g., the patristic connection with 20th century African theological pioneers), as well as an examination of ancient African Christianity, as “deeply African in ethos and spirituality” and as therefore “precursors of the best in modern African Christianity” (

K. Bediako 2001, p. 31). This perspective would safeguard against seeing African realities as “exotic”, or as an aberration, for, since Christian history is one story, he believed one could always find useful points of comparison with earlier periods. Equally, one could be freed from the dominance of later, post-Enlightenment Western models.

5.3. Context

By context, the third circle to the right of

Figure 1 and overlapping, he meant the total context, “not locked in the tyranny of the immediate” (

K. Bediako 2001, p. 31), but comprising 2000 years of an African story, and “[providing] us with some tools for assessing” modern endeavors—he is here thinking of the ascetic monastic tradition of the desert fathers, which stands in total contrast to the contemporary prosperity gospel lifestyle. He would also include the indigenous wisdom locked in pre-Christian traditions and cultures. The primal religions (

Turner 1977, pp. 27–37;

K. Bediako 1995a, chap. 6) are not to be feared or demonized, “primal” being a positive phenomenological term that embraces the indigenous religions of the world through the ages. It does justice to the affinities they share since they have constituted the spiritual preparation for the gospel that helps to explain the massive African accession to the Christian faith in the 20th century. This development merely reinforces the pattern throughout Christian history, where indigenous religions around the world prepared the ground for the reception of the faith. Such a focus provides a way to “be self-critical without being self-deprecating and self-destructive” (

K. Bediako 2001, p. 31), for he advocated looking for home-grown solutions to Africa’s current problems within the ancient indigenous wisdom. A further element of context, and an increasingly important one for the ACI curriculum, is the phenomenon of grassroots theology, the exuberant expressions of faith of ordinary Christians in love with Jesus (

Kuma 1980).

5.4. Mind for Mission and Transformation

The fourth circle of

Figure 1, also overlapping the other three, “mind for mission and transformation”, represents “not an abstract notion” but “describes authentic experience” (

K. Bediako 2001, p. 31) of engaging in mission and growing in spiritual maturity as the essential elements enabling insight into the other components. “Theological knowledge, as intellectual activity, is not independent of spiritual discipleship.” (

K. Bediako 2001, p. 31). Indeed, one could also use this circle as the starting point for further creative curriculum design, as the motive for exploring the fresh developments identified as needing engagement.

With respect to curriculum design, the overlapping circles thus show how connectivity may be achieved between courses towards a full curriculum, as well as how components within courses may be conceived, and they are suggestive of areas for development and innovation in an ongoing dynamic of curriculum development, the point being “to equip us for meeting our own needs and problems” (

K. Bediako 2001, p. 32).

5.5. The Three Concentric Circles

The concentric circles of

Figure 1, namely, the Living God, the Bible, and faith and spirituality, are the parameters that will hold a curriculum together, with a view to safeguarding a Christian and theological focus: “the African experience of the Living God, the Trinity of Father, Son and Holy Spirit, in various manifestations and forms” (

K. Bediako 2001, p. 31), given that “there are few places in Africa where there is any doubt about the existence, reality and immediacy of God”; the Bible, “not just as an ancient book but as a context which people inhabit and in which they participate, especially through the Scriptures in the vernacular” (

K. Bediako 2001, p. 31) and as “the means by which many Africans have made their own responses to the Christian message in terms of their own needs and according to their own categories of thought and meaning”; faith and spirituality, including “the enduring primal worldview with its stubborn refusal to make sharp dichotomies between sacred and secular, spiritual and material” (

K. Bediako 2001, pp. 31–32), as well as the convergence of this world-view with large areas of African Christian confession and experience.

6. The ACI Curriculum

What Kwame Bediako and the ATF team were aiming at, it would seem to me, was a “decolonizing of the theological and scholarly mind”, to borrow Ngugi Wa’Thiongo’s term, embracing research methodology and spiritual formation. Bediako’s own labors in curriculum development over a good number of years should be understood as an extension of his fundamental vocation, his calling to serve the gospel in Africa. This sense of call could perhaps be crystallized into three concerns: the need for new and liberating definitions of theology, the need for a new focus and the need for new perspectives.

6.1. Need for Liberating Definitions of Theology

With respect to the first, the definition of the theology underlying the curriculum that was developed could be articulated (in his words) as “the search for Christian answers to culturally rooted questions” (

K. Bediako 1992, pp. 1–12, xv–xvii; also

https://infemit.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Mentor-Bediako-2.pdf for an accessible reference, accessed on 17 August 2023), which assist Christian mission, spiritual growth and an assured African Christian identity, pastoral nurture and social transformation (hence the original name of ACI included “applied theology”). If historically this has been the task of theology through the ages, then it follows that modern Western theology need no longer be understood as normative, or even as the starting point, as has been the assumption behind the curricula at present operating in the Western world and inherited from Western institutions, but as equally culturally rooted and provisional. It may then find its appropriate (non-normative) place in non-Western curricula. The aim of the curriculum, therefore, was to provide a formation that would equip Africans in particular to seek Christian answers to those culturally rooted questions and to discern why they should respond in particular ways to specific situations.

6.2. Need for New Focus

A new focus means looking with fresh eyes (African eyes) at received curricula and theological disciplines, for example, looking at patristic studies as an exercise in engagement with culture (

K. Bediako 1992), or undertaking Scripture exegesis not only in Hebrew/Greek/English/French, etc., but also in African indigenous languages. In courses in Christian doctrine, he suggested that:

The area of Christian doctrine needs to shift focus from being a study of what Christians believe in the abstract, to including an understanding of how Christians came to believe what they believe and how their engagement with the context of their time led to fuller understanding of biblical truths…the study of doctrine can provide a window into our contemporary struggle with gospel and culture engagement as we see how our understanding of Jesus Christ may grow to meet the challenges of our context.

6.3. Need for New Perspectives

The concern for new perspectives means paying attention to African languages, religions and cultures, with their underlying world-views, for what they may yield in insights into Christian truth, spirituality and practice, and as “praeparatio evangelica” in gospel and culture engagement. As Kwame Bediako observed in an exposition of Hebrews:

… if, for some reason, we are negative about our own traditions, ashamed of our own cultures, if we do not really have any confidence, say, in our own language as the language that God also speaks and uses, then the likelihood is that we shall not see what indicators God himself has sown in our traditions and cultures. It may also mean that the Good News of the Lord Jesus Christ that we profess may not have become our own at all. We may, in fact, be trying to survive on a borrowed Gospel, which, therefore, is not our own deep experience.

6.4. MTh in African Christianity as Embodiment

The MTh in African Christianity coursework may be understood as an outworking of these concerns, in the light of the framework model illustrated above: discerning the times in which Africa is a heartland of the faith necessitates looking intentionally at the forms of Christian life and worship across the continent with a view to strengthening Christian scholarship, Christian understanding, witness and engagement in Africa, but also beyond Africa. Connecting with tradition and history requires courses in Christian history in Africa, including its earliest North African phase, and world mission history as a whole. Engaging with context means not neglecting research into indigenous religious and cultural realities, both traditional and Christian, and the history of their engagement, issues of gospel and culture, and all with a mind towards mission and transformation. This includes affirming the mission significance of the primal religious and cultural setting, towards enabling a Christian presence that does not merely skim the surface of African cultural expressions but seeks to work towards practicalities of transformation through applied theology. The Living God, whose various names have found their way into the mother-tongue Scriptures, the mother-tongue Bible itself, and the undoubted faith and spirituality of African peoples constitute the concentric circles that ground the whole curriculum.

7. Developments in the Curriculum

From the initial MTh program in African Christianity and its extension in the PhD (which includes the same year-long graduate coursework of four core courses and two electives), with their requirement that students produce an abstract of their thesis in their mother tongue as well as in English, after five years, a second track was developed in Bible Translation and Interpretation that took mother-tongue engagement further, in order to maximize skills in biblical exegesis and hermeneutics in the mother tongue, by working from the Hebrew and Greek directly into indigenous languages.

When ACI became an independent chartered institute, the MA (Theology and Mission) was launched, as I noted earlier, a foundational theology program with a mission focus, channeling the same concerns and perspectives at a lower level in a modular form of nine week-long courses and a project essay, spread over 10 months. It has proved very successful with the targeted group of professionals active in church life, and some have caught the scholarly “bug” and gone on to MTh and even PhD.

From there, the range of electives has been expanded at the MTh/PhD level to include a special course in early African Christianity and one in holistic mission and development, given the environmental crisis Africa is now facing and the lack of awareness in churches of the need for stewardship. In these new electives, contextual research findings were factored into substantial sections, helping to shape their content, but students’ research findings have been incorporated within the curriculum as a whole, through additions or modifications of segments in the existing courses, where it was fitting. Articles from high-quality student and faculty research are regularly solicited for the Journal of African Christian Thought, as one way of producing published material that could serve as texts and strengthen the bibliography, especially where whole issues of the journal have been devoted to a relevant theme.

At the MA level, ACI began a second cohort each year, offering a range of options, with two focused courses in applied theology in each option, alongside seven of the original courses. The program began in 2010 with the Pentecostal studies option, following consultations with the Church of Pentecost (the largest Pentecostal denomination in Ghana), but the range was expanded in 2013 to include a biblical studies option, a holistic mission and development option and a mother-tongue theology option. More recently still, in 2016 a leadership option was started, followed by a Bible and science option, and finally a world Christianity option, which privileges the African Diaspora Christian story as well as other non-Western stories.

In addition to new courses and programs, ACI is endeavoring to update the curriculum regularly, taking account particularly of new publications in the field, or new discoveries and developments that serve to fill out the curriculum. Each course has its own dynamic and it is expected that lecturers will be keeping abreast of such developments and finding ways to incorporate them as appropriate. These new innovations are captured periodically in institutional documentation. The momentum for development is in fact fueled by younger lecturers building upon what has gone before as they factor their own learning and research focus into particular courses.

8. Curriculum Development—Possible Lessons to Be Learnt

The first and most obvious lesson is that one needs a vision of what is needed and why. It is not enough simply to believe one ought to Africanize. There needs to be clarity as to what one wishes to achieve, e.g., what it means to be a Christian in Africa, and what ingredients are needed for transformation in culture, church and society. Vision is essential for persevering in the face of challenges and resistance to change. This is particularly so in church-founded institutions such as ACI, which went through a series of crises with the church hierarchy in the 1990s before a wider acceptance was achieved. Centers or programs within universities may meet similar challenges to what ACI programs would have faced within the University of KwaZulu-Natal if the opening had not come for independent academic status.

Courage is also needed for engaging with traditional African culture and spirituality, which have not gone away, even if one might be tempted to think so in light of the inroads of global culture evident across the continent. It was Kwame Bediako’s view that Africa had entered modernity bypassing the Enlightenment, in that as noted earlier, it is possible to be thoroughly modern and at the same time deeply spiritual about modern living. Further, if we understand Christianity historically as a universal faith with particular local expressions, there is no need to be paralyzed by the specter of “syncretism”, where Western expressions of the faith are taken as the norm. Rather, there would be freedom to seek answers to the question, “If Jesus were to appear as the answer to the questions Africans are asking, what would he look like?” (

Taylor 1969, p. 16).

I would suggest, drawing from ACI’s learning, that what is needed in the long term is not so much isolated new courses stuck on to existing programs, though this may be a way to begin. From what we have observed in other institutions locally, the changes that have been made in recent years have been along these lines and have had minimal effect on curricula as a whole. They are not nearly so effective as something that is wholly homegrown and tailored to existential needs, while at the same time connecting with the wider Christian story. Thus, a more fruitful approach would be the establishment of new degree programs along specific lines, such as ACI has developed.

Such a vision, however, needs to be advocated and shared with others, so that they catch the vision and become willing to direct their energies into it. One should not expect to “jump in”, as it were, and then expect others to automatically see the point. In the ACI story, this promotion and advocacy of curriculum innovation took place over several years in a variety of continental settings before the MTh program gelled and was ready to be offered.

Then there is the need to identify facilitating institutions, as well as financial support, for the implementation of new curricula. This may prove to be quite a challenge. From ACI’s own experience in the early days and from the experience of alumni, who leave ACI fired up to do something new, it may be difficult to introduce the changes one sees as needed within institutions. It may require diplomatic skills, as well as considerable ingenuity and networking with like-minded colleagues, possibly in different institutions, to get something off the ground. As a chartered institute, qualified to mentor other institutions and validate their degrees, ACI is discovering how difficult it is to get them to Africanize their curricula, and even to introduce more African material into their bibliographies. Resistance occurs not necessarily because of a dislike of change, though that may be the situation in some instances, but simply because the faculty, having often been trained in Western academia, simply do not have the expertise to do it and may be reluctant at this point in their careers to do the fresh research that would equip them for it.

But that does not mean to say it is impossible. As Kwame Bediako often pointed out, the early 20th century pioneers in African theology, such as John Mbiti of Kenya and Bolaji Idowu of Nigeria, upon their return to Africa from training in Europe, continued to do original research, wrote books and developed courses in areas that no one had taught them. Bediako himself spent a number of years reconnecting with his Akan culture and also discovered his mother tongue as a literary language upon his return from studies in Europe. In the process, he discovered the wealth of theological insight in his mother-tongue (Twi) Bible, which he then fed into his preaching and Bible expositions, and which underlay his persistent advocacy of the mother tongue at the highest level of scholarship. For those for whom it may indeed be too late to chart a new course, there is always the option of encouraging the vision and initiatives of younger faculty (see

Gaisie 2020).

So, one needs to identify institutions and persons in leadership who are open to innovation and are willing to depart from the beaten track of theological education that one has inherited. It may be, as was the case with ACI, a matter of new wine needing new wineskins, but even in this case, the School of Theology, University of Natal, saw its own need at the time (the early 1990s) and was willing to welcome the ACI program and validate its degrees. And as I mentioned earlier, Kwame Bediako and I had been exposed to instances of innovation in the University of Aberdeen in two forms—the young Dept of Religious Studies, and even more radically, the two centers for research, the Centre for the Study of Christianity in the Non-Western World, and the Centre for the Study of New Religious Movements in Primal Societies within the Dept of Religious Studies. These latter were able to drive the curriculum development in the Dept of Religious Studies when the Faculty of Divinity was slow to see the value of such innovation. The point is, to look for, and find, an appropriate institutional frame, wherever it may be, or failing that, if one can raise the necessary support to do so, establish a new one, as Kwame Bediako was able to do.

It is evident also that it requires courage to suggest and advocate changes in focus within disciplines. The pioneer African theologians, such as John Mbiti, who did this in the mid-20th century, were often misunderstood and maligned in the early days, including by established theological institutions in Africa. Times have moved on in some respects, yet as ACI alumni have experienced, one may expect similar challenges and resistance from those whose whole training has been Western-oriented and who therefore may be handicapped when it comes to change. With respect to looking at existing disciplines with new eyes, I have already mentioned two examples—a mother-tongue focus in biblical studies to enable what Kwame Bediako called “a new creative stage for Christian understanding and therefore a new creative stage in theology” (

K. Bediako 2010, p. 47), and a gospel and culture engagement focus to patristics. Kwame Bediako came to realize during his undergraduate studies in London that historical theology and the development of doctrine was a more helpful approach in Africa than systematic theology. Hence, the introductory course for the MA is called “History of Christian Thought and the Theology of Mission”. He also privileged history over anthropology (which began as a colonial science). One of our faculty has attempted a Christology in his mother tongue, seeing how Jesus connects with traditional spirituality, such as manifested in traditional festivals like H

om

ow

o (

Laryea 2004). One may equally mention a study of African Islam, such as Lamin Sanneh produced (

Sanneh 2020), for homegrown pacific models of Islam do exist that show a different face, opening up a vista on possibilities for fruitful dialogue and offering a counter-narrative to hostile stereotypes. One such is an African Muslim scholar at the University of KwaZulu Natal, Pietermaritzburg, who has explored issues of Muslim identity with reference to Christianity (

Sitoto 2004, pp. 8–15).

Changes in focus within disciplines require courage also in being prepared to take a stand and argue for them if and when, say, panel members on visitation from accreditation boards, most likely trained according to models established in Western academia, query them. As well as being able to articulate clearly why one has developed a particular curriculum or employed a particular methodology, a crucial safeguard here is a dedication to high standards in scholarly excellence. Thorough, meticulous, well-researched and documented scholarship is a common currency that all should be able to recognize, and none can gainsay.

A further lesson is that successful curriculum innovation and renewal of theological education require communities of scholars working collegially together, a network, possibly, of like-minded scholars who share the same vision and can bring their different areas of expertise to bear in the development of a fresh curriculum or a fresh degree. Lone individuals will be limited in their impact. Such collegiality was at work in Aberdeen in the 1970s and 1980s, as I noted earlier, and the ATF network provided ACI with just such a community, without which, indeed, the program could not have taken off. Such a group of persons also helps to motivate others to see the point and think afresh and build momentum towards curriculum renewal. It has been ACI’s experience too that the challenge of identifying the next generation of faculty is ongoing, given the radically different nature of the curriculum from what is available elsewhere. ACI began with a nucleus of persons, both full-time and adjunct, and was able to raise funds for faculty development to train a new generation, many of whom are now in leadership positions. ACI has continued with this policy, as the pool of suitable academics from elsewhere who share the vision and would be willing to relocate remains small.

ACI has not been immune to the perennial challenge of building an institution in the midst of a precarious economic environment, which has indeed been aggravated in recent times by the COVID pandemic and a recent history of government economic mismanagement. These factors have had an impact on both student numbers and the level of salaries that can be afforded and therefore the challenge of retaining gifted faculty. The availability of some scholarship and bursary help has been decisive in keeping ACI afloat. This means that any African institution such as ACI needs a creative and energetic ongoing fundraising effort, and to build a pool of endowment funds. The climate for such fundraising was much more conducive in the mid to late 1990s, but possibilities still exist and institution- and program-builders and leaders need to be prepared to look for them.

Last but by no means least, there is the need to build the necessary resources to support the new curriculum, in other words, to Africanize the bibliography: hunt for existing materials out there in print, or write the appropriate textbooks, put readers together for specific courses (even if they are “in-house” publications initially) and expand the holdings of libraries. One should also look for archival sources, and indeed, if possible, develop a local archive as ACI has undertaken, as repositories of local resources, both traditional and Christian. Primary sources do exist in African communities, but they often need to be ferreted out. Possibly families may hold materials, not realizing their importance and may not be caring for them very well. They can often be encouraged to lodge them in a safe environment. At ACI students are now encouraged, upon graduation, to lodge their field research materials, or copies of them, in the ACI archives, building up a body of indigenous materials for the use of researchers in the future. Cultural and religious memory, as well as African Christian memory, needs to be rescued and preserved for the future.

9. Conclusions

From its inception, the African Christianity curriculum met with a positive reception from students. I cannot think of one who did not experience a sense of liberation and affirmation or fail to see how the learning could be translated into discipleship and ministry on the African continent. Interestingly, in the early South African setting, we found that South African students at the University of Natal of Caucasian and Asian ancestry who took some of our courses also found our courses answered some of their existential questions and met felt needs in their own spiritual journeys in the South African context (see for example,

Bollaert 2008, pp. 30–49). This uniformly positive response continues today and at all levels, whether MA, MTh or PhD. ACI faculty are continually encouraged by the testimonies received from alumni in their varied spheres of ministry of how their ministries have been transformed. It makes all the hard grind of pioneering in theological education seem worthwhile. Curriculum renewal and the strengthening of the theological academy are essential for Christian depth and continued vitality in African churches and communities, and it is to be hoped that the vision for such will take root more widely with ever-increasing momentum.