Researchers, scientists, and artists recognize the impossibility of absolute access to reality as they progress through areas of scientific or artistic interest because human ways of access are always nondeterministic, limited by conditions and the time–space continuum (

Paar and Golub 2003). Partially present in medieval art and highlighted by the unattainable nature of the Cubist representational effort around the polyperspectivity of the all-seeing eye and cited and analyzed in numerous works of art of the twentieth century, this inability to comprehend reality in its fullness, manifests human weakness and limitation evident in every aspect of human existence. Man is constrained by his body, personality, space, time, and the defaults of life. By experiencing daily effort, misery, and uncertainty, man begins to comprehend the reality in the amount that he is given. In his book

Introduction to Christianity, Joseph Ratzinger ponders the possibilities of human knowledge through the dialogue between science and faith, concluding with: “Only by circling around, by looking and describing from different, apparently contrary angles can we succeed in alluding to the truth, which is never visible to us in its totality” (

Ratzinger 2017, p. 168). There is no such thing as total objectivity in human perception. As there is no such thing as an innocent eye, there is no such thing as pure science or art. Regardless of the scientific or artistic discipline with which he deals, a researcher, philosopher, scientist, or artist always carries himself and creates and observes reality through himself, drawing conclusions based on the questions he has asked. As a result, artistic research via artistic practice offers a form of observation and immersion that is no more subjective or less objective than any other discipline. Different approaches, different questions, different insights, different experiments, departures from different starting points—these enable the enrichment of the cognitive world, but they require an appreciation of different ways of knowing as a prerequisite.

The presence of this kind of interaction can be identified within the artistic oeuvre of Barnett Newman, an American painter and theorist. With his paintings, Newman (1905–1977) communicates the tone of the spirit and various spiritual states. He conveys a type of religious experience, a specific type of spiritualized feeling, through the medium of painting. Stepping into his large-scale paintings involves experiencing them with the entire body, with the senses—staying with the body in the space of the painting. The images are not about the author’s emotions or a narrative that he wishes to portray but rather about universal human values and goals. The observer enters the space of Newman’s paintings physically and intellectually, bringing his mind and soul into a reality that transcends everyday life. Harold Rosenberg denies the religious connotation of Newman’s series of fourteen black-and-white paintings titled

The Stations of the Cross: Lema Sabachtani. In accordance with Berger’s interpretation of the conditioning of our view, Rosenberg discusses the necessity of interpreting Newman’s The Way of the Cross in light of his secular worldview (

Rosenberg 1978, p. 81). Newman initiates the creation of this cycle without knowing how it will ultimately develop. A few years later, he realized that he was constructing the Via Crucis. Such incremental realizations are not exceptional but rather a common byproduct of creative activity. Numerous artists’ works demonstrate the gradual revelation of their own creative process and its significance. Humility prior to the realization of the work by recognizing the participatory role of the artist who builds the work as a collaborator, gradually and persistently progressing in the game of discovering the layers and contents that are offered to him and sometimes imposed, is a necessary condition for genuine artistic creativity. Newman’s work exemplifies an exploration into the potential of revealing the transcendent through the author’s artistic inquiry, particularly by means of matter. This discourse explores the role of art in the process of transforming tangible, psychological, and corporeal realities into forms that allude to realms beyond the limitations of human perception.

In order to further elaborate on the objective of this study, which is research into attempts in contemporary art to convey transcendent realities through the lens of the artist, an investigation will be done employing the concepts of intuition, asceticism, and silence. The investigation will primarily concentrate on the process of artistic creation, specifically within the act itself.

2.1. Artist and Intuition

The intertwining of physical and spiritual aspects and the materialization of intuitive ideas are the primary distinguishing features of art in comparison to philosophical or scientific activity. Artistic creativity is a type of spiritual activity (

Kupareo 1993, p. 7). The artist is invited to cultivate a special gift of creativity by experimenting with the transformation of matter. As opposed to destruction as a human-exclusive action. In opposition to “nothing”. In the middle of the 20th century, Jacques Maritain discussed creative intuition, or more precisely, creative emotion (

Trapani 2011, p. 111). By art, he means the creative, productive, and inventive activity of the human spirit, but he makes a further distinction when referring to poetry, which he defines as “the intercommunication of the inner being of things and the inner human Self, which is a kind of divination (

Maritain 1977, p. 3).” This exact remark by Maritain was confirmed by research conducted during the drawing activities that informed the development of this work. In his essays on aesthetics,

Man and Art,

Raimond Kupareo (

1993, pp. 79–80) observes well how in Maritain’s works, he often struggles with attempts to verbalize thoughts about intuition and creativity: “I search by tapping for a suitable word”, “I speak with apprehension and fear”, which, in addition to philosophical reflection, Maritain discovers his own experience of struggle with the transmission and “materialization” of the intuited. According to Maritain, poetic intuition arises from the subconscious and unconscious depths. Kupareo asserts that creative intuition is the origin of all art. Rudolf Arnheim, on the other hand, defines intuition as the retrieval of cognitive data through the perceptual field (

Arnheim 2008, pp. 27–40). Excluded is Maritain’s interpretation of intuition as poetic insight. It rules out the possibility of divine inspiration and the supernatural. Intuition is viewed as a cognitive procedure that is continuously and systematically interwoven with intellectual analysis. Arnheim’s thesis is partially supported by an introspective examination of the drawing process in this research. It considers Arnheim’s prediction of the perception of the sensory field to be too limited, expanding it from the space of collaboration of intuition and cognition of the subjects themselves to broader horizons of the sensory field in which dialogic intervention of the subject with transcendent realities or of transcendent realities with the subject is possible. To accept or approach such a possibility, experiential knowledge is required. This interpretation is founded on the experience of consciously observing the creative process while in it. In this research, I am engaged as an artist who is going through a creative process and an observer of that same process. This particular position aligns with Ratzinger’s assertion that man cannot ask and exist as a mere observer because he who tries to be a mere observer experiences nothing (

Ratzinger 2017, p. 170). If the human being is viewed positivistically, exclusively through horizontal relations, then the influence of vertical relationships on the human system of understanding and reality itself cannot be accepted. However, if the human being is viewed as a being that is part of the created world and, as such, is in a relationship with the Creator, then the paradigm shifts and understanding expands from the horizontal dimension into the space of perspectives that are difficult to comprehend and unpredictable, which are a mystery to the limited human mind but present and perceptible to the artist, the mystic, and the intuitive scientist. The experience of numerous artists and scientists, whether Renaissance, Baroque, or contemporary, lends credence to what has been asserted.

2.2. Artistic Asceticism

In artistic creation, asceticism specifically refers to adherence to the creative process itself, which is understood as a yearning for a reduction of artistic expression to its essentials. It is frequently observable in artistic practice in the form of expressions that do not adhere to a narrative. This approach aims to capture the essence of artistic expression by eliminating non-essential elements, deviating from narrative structures, and simplifying intricate visual representation systems into a concise visual language. By employing this mode of artistic expression, artists can go beyond mere visual language and access the realm of transcendental reality. The process eludes complete rationalization and explication through reason, yet it manifests tangibly within the realm of artistic creation. The artist is able to perceive this transcendental reality only after engaging in this particular process. The French philosopher Michel Foucault elaborates on this particular type of experience. The author acknowledges that he regards writing as a process through which he can uncover previously unnoticed insights or perspectives that were beyond his initial perception. The author initiates the writing process with a lack of knowledge regarding its ultimate direction or the conclusions that will be reached. However, through the act of writing, the author uncovers both the trajectory of the work and the substantiating evidence (

Foucault 2015, p. 50). This article examines the gradual revelation within the artistic process, focusing on the concepts of intuition, asceticism, and silence. Under this perspective, similar experiences of poets, painters, draughtsmen, and artists can be observed and cataloged.

Ante Kuduz (Vrlika, 14 June 1935–Zagreb, 24 January 2011), a notable Croatian graphic designer, printmaker, and painter of the 20th century, distinguished himself throughout his whole creative output with his highly structured drawing gestures. His hand thinks, observes, and expresses what he has seen, whether it be the hills of Zagorje or the landscape of Dalmatian Zagora, the region where he spent his early youth. Kuduz’s eye’s sensitivity to perceived reality captures the most subtle sequences and contrasts them with huge, dark, strong forms. A return to mental synthesis follows the transition from analytic to expressiveness. His creativity has grown through a number of cycles: Beginnings (1961–1955), Frame (1965–1972), Space (1972–1975), City (1976–1981), Landscape (1981–1991), and Graf (1992–2011). From the initial works to the latest graphs, the artwork is based on drawing. The majority of his work consists of monochromatic rhythms, with the exception of a section of the Space cycle from the 1970s in which serigraphs provide color to the artist’s structures. Kuduz’s internal and external environments are characterized by a sophisticated visual language, refined perceptuality, and the combination of a lace-like raster and thunderous calligraphic strokes.

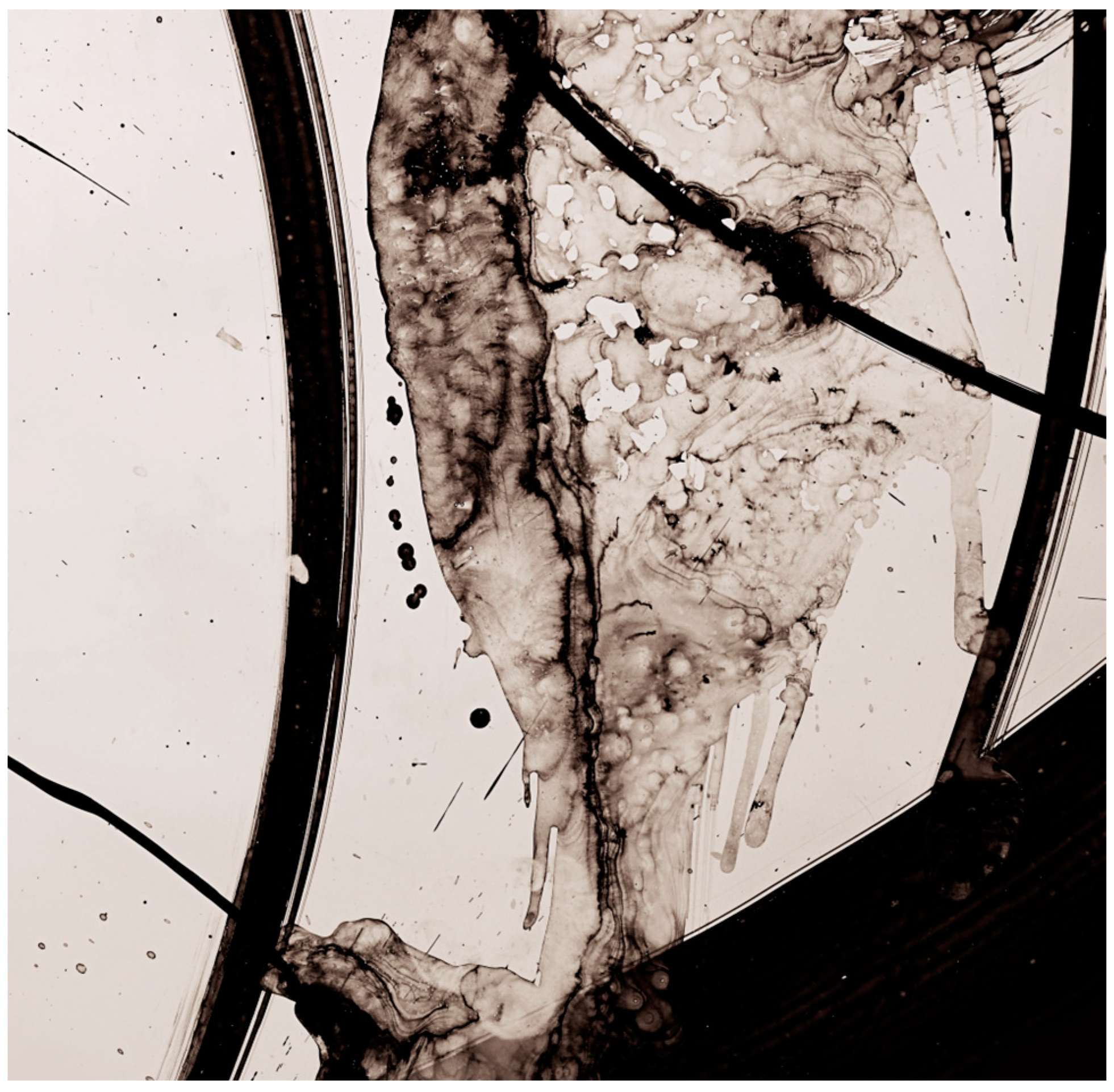

The economy of pure forms, through the author’s refined sensitivity, highlights the dialogical moment of the inner imperative of man’s relationship with nature. The initial works displayed a unique transcendental radiance. Circular curves, thickening, and overflowing frames attest to a spacious, personal interior. Through the years, the experience of a line that sought, constructed, and multiplied through frame, space, city, and landscape turned analytical. The final

Graf cycle (

Figure 1), as if he spoke “from the inside” once more. Organic forms, constructed with raster and placed ascetically on the whiteness of the paper, and broad black strokes with ink and brush resonate powerfully on the whiteness, allowing for the compression and concentration of energy on the surface. There is a force within them that creates a singular whole of black characters accented like tympanums against the white silence of the background from which they emerge. It was as if an extraordinary talent had accumulated and crystallized and had now broken through the medium of drawing.

As an artist, designer, draftsman, and professor at the Academy of Fine Arts in Zagreb, Kuduz emanated the wisdom that is the result of asceticism as a way of life. Inherited from the strong code of his homeland, the Dalmatian Zagora, he cultivated with his life and work a distinctively nuanced character and expression. It is reflected in Kuduz’s artistic expression, which is as strict as it is compassionate, as cautious as it is soft, all the way up to the joyful playfulness revealed in the video work presented at the retrospective exhibition held in Zagreb’s Glyptoteka, in which he played with the movement of his black-and-white forms with flashes of color that snuck out of the serigraphy cycle and entered the form of video.

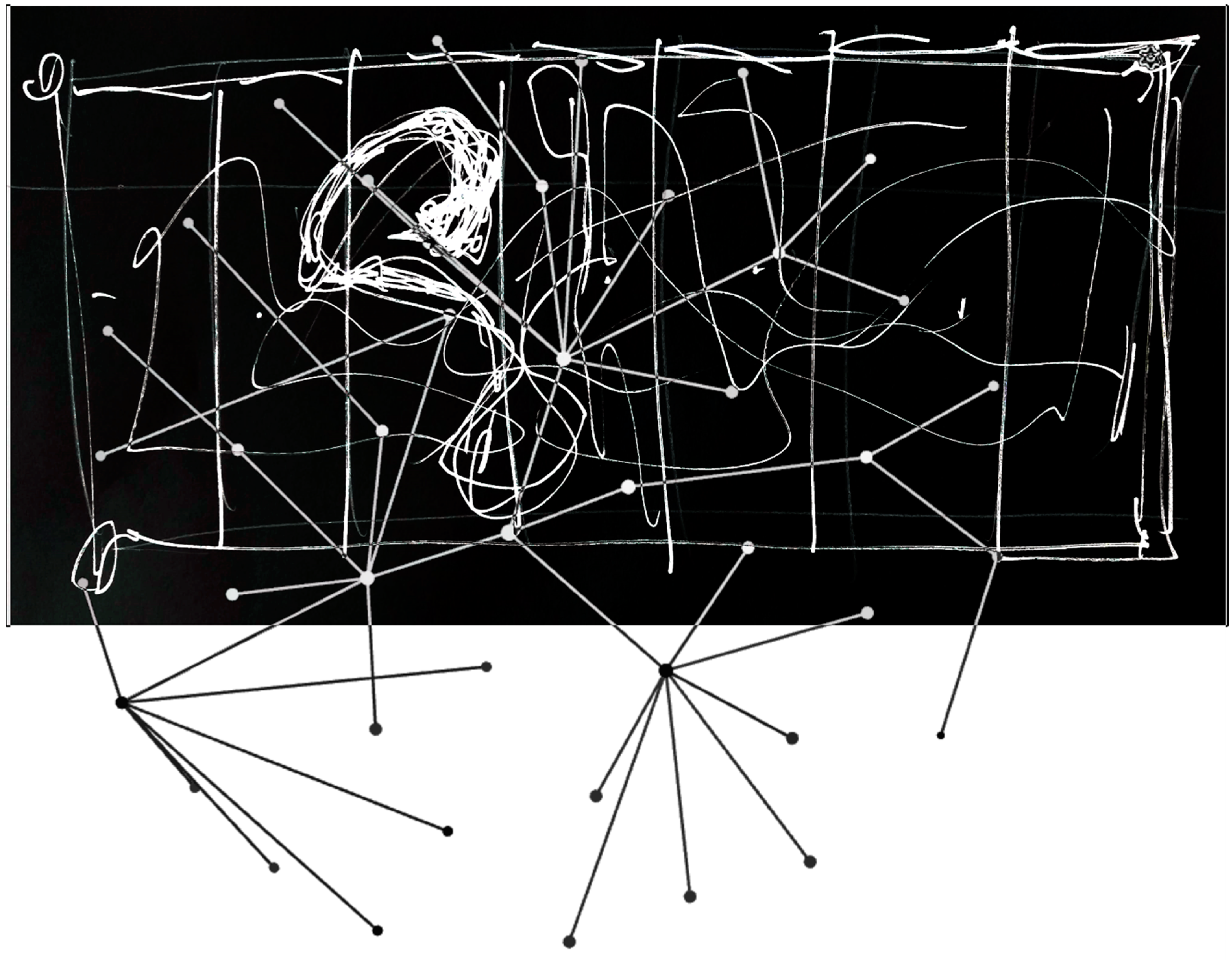

Julije Knifer (Osijek, 23 April 1924–Paris, 7 December 2004), a Croatian painter with a propensity for conciseness and minimalism, developed a black-and-white image and form in the 1960s of the 20th century that he would not abandon until the end of his creative life. His reflections on the philosophy of existence and absurdity, along with the serial music, found in meanders a repetitive, monotonous rhythm as “the simplest way to express his greatest complexity” (

Horvat-Pintarić 1970). The recurring motif of the meander (

Figure 2) tends to be not only a transfer of the author’s visual repertoire but also an imprint of the author’s spiritual state, his reflections, and his artistic behavior. The picture shows a part of the exhibition

Julije Knifer: Without Compromise, held in 2014 at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb. Visible is the rhythm of the works, which “undress” the black and reveal the white through their internal logic.

Knifer establishes a rhythm of extreme contrasts by combining vertical and horizontal stringing: darkness and light, black and white. Persistence in various motifs and Spartan persistence in expressing the reality that is intrinsically imposed on him disclose the author’s ascetic disposition. Knifer’s highly refined and spiritualized artwork is the result of his exceptional consistency in the creative process. Knifer was an artist who did not follow trends but was completely committed to his own internal logic, uncompromisingly like a monk. Each action represented the spiritual process of pursuing silence, peace, and isolation, i.e., the process of entering his own world and devoting himself to ascetic work. The work of Knifer is immersed in silence as a space of potential. Peace and solitude encourage the creative process and immersion in one’s own universe. Knifer’s devotion to the meander allowed him access to a complex territory of freedom, to which he remained devoted until his demise.

Another example is Robert Motherwell’s method of painting, which involves a high level of abstraction of reality as if he were peeling away layers to get to the artist’s desired essence. “I often paint in a series, a dozen or more versions of the same motif at once-of the same theme. One brings the weakest up to the strongest, which in turn becomes the weakest and so on ad infinitum, so that one goes beyond oneself (or sometimes below!). There is no knowing, only faith. The alternative… is a black void” (

Terenzio 1980, p. 9). Eliminating the superfluous results in the emergence of content that is a remnant of what is essential, is frequently unnameable and undefinable, but is simultaneously extremely human and poetic. “The subject does not pre-exist. It emerges out of the interaction between the artist and the medium. That is why, and only how a picture can be created, and why its conclusions cannot be predetermined. When you have a predetermined conclusion, you have ‘academic art’ by definition” (

Terenzio 1980, p. 9). Thus, the function of abstraction is to emphasize the meaning of the work. Arriving at meaning. Directly to the point. Motherwell’s 1978 large-scale acrylic on canvas painting

Reconciliation Elegy exemplifies this approach. It is on display at the National Gallery of Art in Washington. Existence and demise. Duality. These are concepts that the artist identifies as instrumental to his artistic creativity. Aesthetics is understood not only as beauty but also as a perspective on reality. In his attempts to achieve the impression of lightness and spontaneity that he sought in his works, Motherwell realized that preparation—of tools and formats, as well as the mental preparation of the artist for work—was necessary to achieve this impression. “The content of a painting is our response to the painting’s qualitative character, as made apprehendable by its form. This content is the feeling «body-and-mind». The «body-and-mind», in turn, is an event in reality, the interplay of a sentient being and the external world. [...] It is for this reason that the «mind», in realizing itself in one of its mediums, expresses the nature of reality as felt” (

Harrison and Wood 2003, p. 645). This study’s observation of the conditions required to achieve this type of expression validates Motherwell’s assertion.

Kuduz, Knifer, Motherwell, and Newman all demonstrate a fervent commitment to the artistic process, a meticulous approach to artistic investigation, and a willingness to explore perspectives and insights that may have been overlooked or not immediately apparent. In their creative processes, they all go beyond mere visual language and toward transcendental realities.