Caught in Narrative Patterns? Analysis of the Swiss News Coverage of Christians, Muslims, and Jews

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Religion and Religious Dimensions

- Perception and experience (experience and recognition of the “divine”, confidence and trust, transcendence);

- Dealing with materiality and media (e.g., books, sacred objects, ritual objects, dissemination media);

- Cognition (religious truth, religious knowledge, understanding of the “divine”);

- Public practice of rituals;

- Private practice of rituals;

- Religious events (e.g., World Youth Day);

- Religious ethics and lifestyle (e.g., abstaining from alcohol or pork);

- Formal religious organizations.

1.2. Framing and Narration

“The ways in which news stories are ‘used’ or ‘processed’ are characterized very much in the same ways that all other kinds of stories are used, decoded, or experienced. A complex of cognitive, affective, and instrumental factors is involved in the process. It involves at one and the same time learning from other people’s experiences, and a kind of vicarious evocation of emotions of empathy or of distanced renunciation.”.

1.3. Comparative Studies and Study Focus

- Their size (Christianity has a 63% and Muslims a 6% population share; however, Judaism has a very small community: 0.2% in Switzerland);

- Their long historical roots in Switzerland (Christianity and Judaism);

- Their position as subjects of tension in Swiss society (Islam and Judaism, see Introduction) (FSO 2023).

1.4. Hypothesis

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Focus Groups

2.2. Content Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Results of Focus Groups

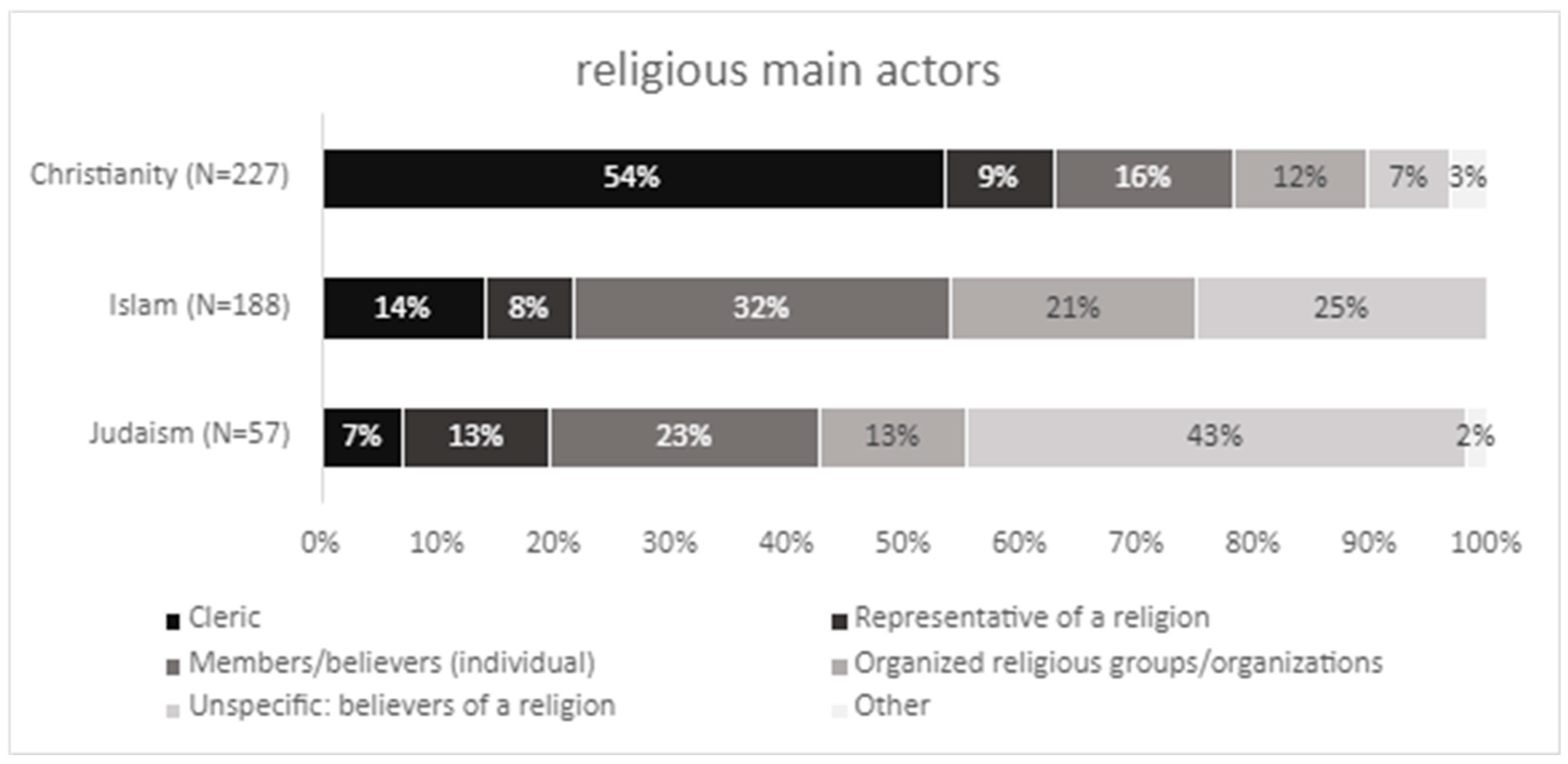

3.2. Results of Content Analysis

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmed, Saifuddin, and Jörg Matthes. 2017. Media representation of Muslims and Islam from 2000 to 2015: A meta-analysis. International Communication Gazette 79: 219–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Azami, Salman. 2021. Language of Islamophobia in Right-Wing British Newspapers. Journal of Media and Religion 20: 159–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appel, Markus. 2008. Medienvermittelte Stereotype und Vorurteile. In Medienpsychologie. Edited by Bernad Batinic and Markus Appel. Heidelberg: Springer Medizin Verlag, pp. 313–36. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, Sean. 2015. Do Two Wrongs Make a Right?: News Analysis of a Violent Response to Clergy Sex Abuse. Journal of Media and Religion 14: 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baugut, Philip. 2020a. Perceptions of Minority Discrimination: Perspectives of Jews Living in Germany on News Media Coverage. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 99: 414–39. [Google Scholar]

- Baugut, Philip. 2020b. Wie der Online-Boulevardjournalismus die Gefährlichkeit der islamistischen Szene konstruiert–und Muslime unter Generalverdacht stellt. Eine Analyse der Berichterstattung von krone.at. SCM 9: 445–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baugut, Philip. 2021. Advocating for Minority Inclusion: How German Journalists Conceive and Enact Their Roles When Reporting on Antisemitism. Journalism Studies 22: 535–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, Elisabeth S., and Robert W. Dardenne. 1990. Myth, Chronicle, and Story. Exploring the Narrative Qualities of News. In Media, Myths and Narratives. Television and the Press. Edited by James W. Carey. Newbury Park, Beverly Hills, London and New Delhi: Sage, pp. 67–86. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Y. 2023. Reporting Religion News. In The Handbook on Religion and Communication. Edited by Yoel Cohen and Paul A. Soukup. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 287–300. [Google Scholar]

- Dahinden, Urs. 2006. Framing. Eine integrative Theorie der Massenkommunikation. Konstanz: UVK. [Google Scholar]

- Dahinden, Urs, and Vinzenz Wyss. 2009. Spezialisierung im Journalismus: Allgemeiner Trend? Herausforderungen durch das Thema Religion. In Spezialisierung im Journalismus. Edited by Beatrice Dernbach and Thomas Quandt. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, pp. 123–35. [Google Scholar]

- Dahinden, Urs, Carmen Koch, Vinzenz Wyss, and Guido Keel. 2011. Representation of Islam and Christianity in the Swiss Media. Journal of Empirical Theology 24: 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlgren, Peter. 1991. Introduction. In Communication and Citizenship. Journalism and the Public Sphere in the New Media Age. Edited by Peter Dahlgren and Colin Sparks. London: Routledge, pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- de Vreese, Claes. 2005. News framing: Theory and typology. Information Design Journal + Document Design 13: 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Døving, Cora Alexa. 2016. Jews in the News–Representations of Judaism and the Jewish Minority in the Norwegian Contemporary Press. Journal of Media and Religion 15: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Saeed, Nadja. 2015. Die Darstellung von Muslimen in den Deutschschweizer Medien vor und nach dem Arabischen Frühling. Eine Inhaltsanalyse der Zeitungen NZZ und Blick. Winterthur: Zürcher Hochschule für Angewandte Wissenschaften. [Google Scholar]

- Entman, Robert M. 1993. Framing: Toward Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm. Journal of Communication 43: 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettinger, Patrik. 2019. Qualität der Medienberichterstattung über Muslime in der Schweiz. In Wandel der Öffentlichkeit und der Gesellschaft. Gedenkschrift für Kurt Imhof. Edited by Marc Eisenegger, Linard Udris and Patrik Ettinger. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, pp. 211–43. [Google Scholar]

- FSO Federal Statistical Office. 2019. Erhebung zum Zusammenleben in der Schweiz: Ergebnisse 2018. Bern: Federal Statistical Office. Available online: https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/de/home/statistiken/bevoelkerung/migration-integration/zusammenleben-schweiz.assetdetail.7466706.html (accessed on 14 December 2019).

- FSO Federal Statistical Office. 2023. Religionen. Bern: Federal Statistical Office. Available online: https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/de/home/statistiken/bevoelkerung/sprachen-religionen/religionen.html (accessed on 10 September 2023).

- Geissler, Rainer, and Heinz Pöttker. 2015. Bilanz. In Massenmedien und die Integration ethnischer Minderheiten in Deutschland. Edited by Rainer Geissler and Heinz Pöttker. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag, pp. 391–96. [Google Scholar]

- Glock, Charles Y. 1969. Über die Dimensionen der Religiosität. In Kirche und Gesellschaft. Einführung in die Religionssoziologie II. Edited by Joachim Matthes and Charles Y. Glock. Reinbek bei Hamburg: Rohwolt, pp. 150–68. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn, Judith, Thomas Schüller, and Christian Wode. 2013. Kirchenrecht in den Medien. München: UVK. [Google Scholar]

- Helland, Chris, and David Michels. 2021. Religion in the News on an Ordinary Day: Diversity and Change in English Canada. Journal of Religion, Media and Digital Culture 10: 250–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepp, Andreas, and Veronica Krönert. 2010. Religious Media Events. The Catholic “world Youth Day” as an example of the mediatization and individualization of religion. In Media Events in a Global Age. Edited by Nick Couldry, Andreas Hepp and Friedrich Krotz. London and New York: Routledge Taylor and Francis Group, pp. 265–82. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, Mary Catherine. 2015. The Death of a Pop-Star Pope: Saint John Paul II’s Funeral as Media Event. Journal of Communication & Religion 38: 95–112. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, Carmen. 2012. Religion in den Medien. München: UVK. [Google Scholar]

- Krech, Volkhard. 2018. Dimensionen des Religiösen. In Handbuch Religionssoziologie. Edited by Detlef Pollack, Volkhard Krech, Olaf Müller and Markus Hero. Wiesbaden: Springer VS, pp. 51–96. [Google Scholar]

- Lecheler, Sophie, and Claes H. de Vreese. 2019. News Framing Effects. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lule, Jack. 2001. Daily News, Eternal Stories. The Mythological Role of Journalism. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mayring, Peter. 2014. Qualitative Content Analysis: Theoretical Foundation, Basic Procedures and Software Solution. Available online: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-395173 (accessed on 1 April 2019).

- Poole, Elisabeth. 2021. Religion on an Ordinary Day in UK News: Christianity, Secularism and Diversity. Journal of Religion, Media and Digital Culture 10: 179–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reese, Stephen. 2001. Prologue—Framing public life. In Framing Public Life: Perspectives on Media and Our Understanding of the Social World. Edited by Stephen Reese, Oscar Gandy and August Grant. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum, pp. 7–31. [Google Scholar]

- Roeh, Itzhak. 1989. Journalism as Storytelling, Coverage as Narrative. American Behavioral Scientist 33: 162–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, Susan, and Philemon Bantimaroudis. 2006. Frame Shifts and Catastrophic Events: The Attacks of 11 September 2001, and New York Times’s Portrayals of Arafat and Sharon. Mass Communication and Society 9: 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taira, Teemu, and Jere Kyyrö. 2021. Religion in Finnish Newspapers on an Ordinary Day: Criticism and Support. Journal of Religion, Media and Digital Culture 10: 203–24. [Google Scholar]

- Thiele, Martina. 2015. Medien und Stereotype. Konturen eines Forschungsfeldes. Bielefeld: Transcript. [Google Scholar]

- Troschke, Hagen. 2015. Kritik, Kritik und De-Realisierung, Antisemitismus. Israel in der Nahost-Berichterstattung deutscher Printmedien zum Gaza-Konflikt 2012. In Gebildeter Antisemitismus. Edited by Monika Schwarz-Friesel. Baden-Baden: Nomos, pp. 253–74. [Google Scholar]

- Vanasse-Pelletier, Mathilde, Solange Lefebvre, and Imane Khlifate. 2021. Religion on an Ordinary Day in Quebec: Cultural Christianity, “Threatening” Islam and the Supernatural Marketplace. Journal of Religion, Media and Digital Culture 10: 272–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber-Menges, Sonja. 2015. Die Wirkungen der Präsentation Ethnischer Minderheiten in deutschen Medien. In Massenmedien und die Integration ethnischer Minderheiten in Deutschland. Edited by Rainer Geißler and Horst Pöttker. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag, pp. 127–84. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, Enqi, and Anna Halafoff. 2021. Religion on an Ordinary News Day in Australia: Hidden Christianity and the Pervasiveness of Lived Religion, Spirituality and the Secular Sacred. Journal of Religion, Media and Digital Culture 10: 225–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyatt, Wendy N. 2012. Blame narratives and the news: An ethical analysis. Journalism & Communication Monographs 14: 153–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Subject | Variables |

|---|---|

| Differentiation | Is a denomination mentioned? (R = 1.0) Which religious actors appear? (R = 0.83) Does the religious actor get to comment at all? (R = 1.0) |

| Thematic Context | Place of the event (R = 1.0) Valence of the event? (R = 0.83) Topics? (Open recording and recoding) Religious dimensions (R = 0.85) Is the religious community addressed as part of a conflict? (R = 0.75) Is the religious community’s good coexistence with others addressed? (R = 0.83) |

| Implicit Moral Evaluation | Is the religious community (main actor) portrayed as responsible for a conflict? (R = 1.0) Is the religious community (main actor) portrayed as responsible for good coexistence? (R = 1.0) Is there a moral evaluation of the religious community’s actions? (R = 0.93) Narrative patterns (see archetypes and narrative patterns, chapter 2.2) (R = 0.8) |

| Attribution | What attributes are used for religious actors? (R = 0.75) Gender of the actor (R = 1.0) Nationality of the actor (R = 1.0) Is the person’s appearance described in the text? (R = 1.0) Is the religious actor portrayed as an exception? (R = 0.83) Is the actor acting or passive? (R = 0.83) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Koch, C.; Hüsser, A. Caught in Narrative Patterns? Analysis of the Swiss News Coverage of Christians, Muslims, and Jews. Religions 2023, 14, 1275. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14101275

Koch C, Hüsser A. Caught in Narrative Patterns? Analysis of the Swiss News Coverage of Christians, Muslims, and Jews. Religions. 2023; 14(10):1275. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14101275

Chicago/Turabian StyleKoch, Carmen, and Angelica Hüsser. 2023. "Caught in Narrative Patterns? Analysis of the Swiss News Coverage of Christians, Muslims, and Jews" Religions 14, no. 10: 1275. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14101275

APA StyleKoch, C., & Hüsser, A. (2023). Caught in Narrative Patterns? Analysis of the Swiss News Coverage of Christians, Muslims, and Jews. Religions, 14(10), 1275. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14101275