Abstract

This paper investigates the intersection of Sufism and philosophy in the Shii context during the post-Mulla Ṣadrā era. Specifically, it traces the scholars who emphasized Ṣadrian philosophical and mystical approaches on both theoretical and practical levels and identifies the roots of the Ṣūfī order in the Shia seminary after 1850, namely the Ṣūfī school of Najaf. I argue that these scholars were connected to Ṣūfī orders such as the Dhahabīyya and the Niʻmatullāhī order, contrary to the claim that they were not affiliated with any formal Ṣūfī order. Furthermore, I highlight the reluctance of the masters and followers of the contemporary “Ṣūfī School of Najaf” to reveal their Ṣūfī connections in the anti-Ṣūfī dominant environment of the seminary. Ultimately, this paper provides a comprehensive understanding of the connections between philosophy and Ṣūfīsm in the post-Mulla Ṣadrā era and speculates on the roots, origin, and development of such a school in the contemporary Shīʿī seminary.

1. Introduction

The Shīʿī seminary is generally known as a religious institution emphasizing instruction in the Islamic sciences, particularly Islamic law (fiqh). Within these parameters, the seminary aims to prepare jurists (mujtahids). The official mission of the al-Hawzat al-ʿilmiya (communities of learning/seminaries) is to educate and cultivate students in the religious sciences, preparing them for the role of “Mujtahids,” thereby fortifying them with the capacity for Ijtihād or independent reasoning.

In some respects, the official curriculum of those seminaries is comparable to a modern study of law to become an expert in civil or criminal law. Yet, this is the exact point that Mullā Ṣadrā (1572–1641) and his followers stressed when they criticized and opposed what they deemed the reduction of the definition of fiqh merely to law. In their understanding, fiqh should not be limited and restricted to exercising independent reasoning in extracting Islamic law or legal reasoning. It should rather be extended far beyond these narrow parameters. Rather than restricting law to its outward dimensions, real or exalted forms of fiqh should display an in-depth involvement with the reality of things or present an in-depth understanding of the revelation and transforming souls to purity and proximity to God, thereby encompassing both the internal as well as the external layers of revelation is the real meaning of fiqh. According to this understanding, the outer fiqh consists of a mere introduction to the law that should not be mistaken for its ultimate telos. The ultimate aim of religion consists in the gnosis of the Real. One cannot reach the inner realities of revelation without recognizing that this “lesser” fiqh (fiqh aṣghar) constitutes an introduction and not an ultimate purpose.

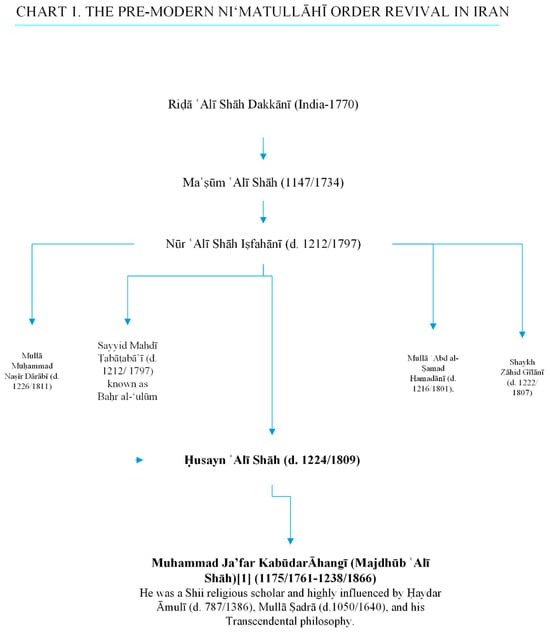

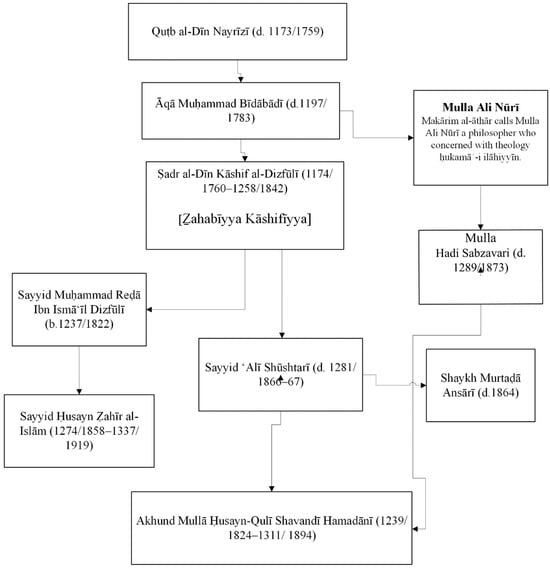

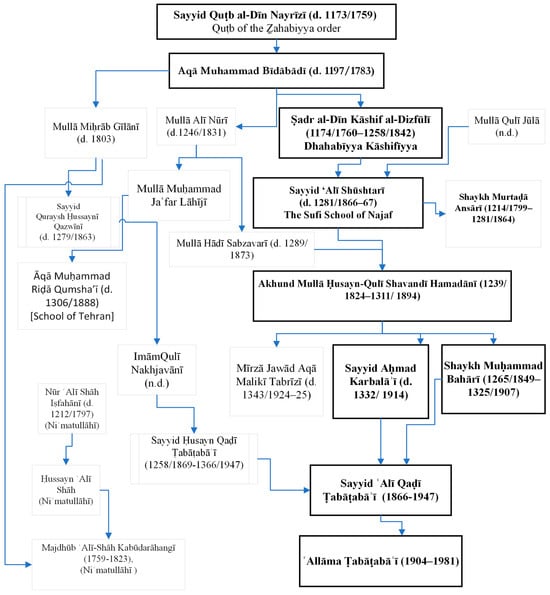

In the contemporary Shia seminary, a trace of a Sufi and philosophical approach to the study and practice of religion is visible. This paper undertakes a historical investigation to contextualize the emergence of Sufism within the contemporary Shīʿī seminary. It seeks to trace the evolution of Sufism in the context of Shia Islam, drawing insights from an analysis of primary sources to elucidate and offer informed speculation regarding the origins of this transformative movement (See Figure 1 and Figure 2). The tendency that this research is pointing to is often referred to by various designations and is perhaps most renowned as the “Maktab-i Najaf” (the School of Najaf) or Maktab-i akhlāqiyūn-i Najaf (School of Ethicists of Najaf) (See Figure 3 for a chronological view of the masters of this school). Masters of the school of Najaf, in the Shia seminary, were promoting practical Sufism along with the study of religious sciences. They believed that practical Sufism is necessary for cultivating the self in the path to return to God. Probably the most known figure among them in Western scholarship is Muḥammad Ḥusayn Ṭabāṭabāʼī (1321/1904–1402/1981). This research is not studying the School of Najaf. It instead speculates on the roots, origin, and development of such a school in the contemporary Shia seminary. Hence, our examination will delve into the resurgence and progression of the two main Sufi orders within the Shia tradition: the Niʻmatullāhī Order and the Dhahabīyya Ṣūfī Order, encompassing both the pre-modern and modern eras. By immersing ourselves in this historical context, we aim to gain an understanding that will facilitate the potential origins, emergence, and evolutions of the Sufi movement within the Shia seminary.

A scholarly lacuna exists regarding this Sufi tendency within the seminary. Our knowledge about it is, therefore, in a state of flux. Kāmil Muṣtafā al-Shaybī, in his al- Ṣila bayn al-taṣawwuf wa-al-tashayyuʿ, provides us with some historical and conceptual background information. Seyed Hossein Nasr, in his chapter entitled Shīʿīsm and Ṣūfīsm and their Relationship in Essense and in History within Sufi Essays, expands on the notion that Shīʿīsm and Ṣūfīsm comprise integral dimensions of Islamic revelation. Henry Corbin, on the other hand, represented Shīʿī figures such as Sayyid Ḥaydar Āmulī (719/1319 or 720/1320—after 787/1385) to Western scholarly audiences as an instantiation of historical Shīʿī-Ṣūfī conversations and interrelations. Reza Tabandeh and Leonard Lewisohn, in their edited volume, Ṣūfīs and their Opponents in the Persianate World, touch on some of the modern features of the Niʿmatullāhī order. ʿAtā Anzalī, in his Mysticism in Iran, depicts some of those opponents to Ṣūfīsm both during and after the Safavid era. Furthermore, Anzalī, in his The Emergence of the Ẕahabiyya in Safavid Iran, presents the development of this order in the Safavid and post-Safavid era based on studies of specific manuscripts. Philosophy in Qajar Iran, edited by Reza Pourjavadi, elaborates on some of the prominent philosophers/mystics, such as Mullā Hādī Sabzawārī, Mullā ʿAlī Nūrī, and others that are understudied in the Western scholarship. None of the mentioned works have paid attention to the emergence and the development of the Ṣūfī schools in the Shīʿa seminary. Tabandeh and Anzalī solely study either the Niʿmatullāhī or the Zahabiyya order. Only Sajjād Rizvī, in his article on Mullā ʻAlī Nūrī, who was a disciple of Bīdābādī, very briefly mentions Ṣadr al-Dīn Kāshif al-Dizfūlī (1174/1760–1258/1842) and states that he was “a renowned mystic associated with Dhahabī order who also did much to spread ʻirfiān in the shrine cities of Iraq.” Rizvī, however, does not provide more detail on how Sayyid Kāshif caused the spread of ʻirfiān (Sufism) in the shrine cities of Iraq, in which the leading Shīʿī seminaries were located.

Several figures in the post-Mulla Ṣadrā era emphasized expanding and promoting his teachings or following his footsteps in the mystical and philosophical approach both on the theoretical (naẓarī) and practical (ʿamalī) levels. Sadūqī Suhā in his Taḥrīr-i s̲ānī-i tārīkh-i ḥukamāʼ va ʻurafā-yi mutaʼakhkhir (The Second Compilation of the History of Philosophers and Mystics) mentions multiple chains of those who taught or followed Ṣadrā’s philosophical methodology and approach, or rather his philosophical mysticism up to the present day. To clearly understand the ground upon which the later Shii-Ṣūfī school in the seminary was founded, it is necessary to study those figures. Among these scholars, some are better-known members or masters of the Dhahabīyya Ṣūfī order, such as Shāh Muhammad Dārābī (d. ca. 1717), Quṭb al-Dīn Nayrīzī (1689–1760), Mullā ʿAlī Nūrī (d. 1246/1831), Bidābādī (d.1197/1783), Mullā Hādī Sabziwārī, Bahr al-ʻUlūm, and others. There are also some other scholars connected to the Niʻmatullāhī order, such as Mullā ʻAbd al-Ṣamad Hamadānī (d. 1216/1802). In addition to Saduqi Suha’s chronology, Purjavadi, in his introduction to Philosophy in Qajar Iran, describes that Gobineau, the French ambassador to Iran, under the influence of Āqā ʿAlī Ṭihrānī, points to Mullā Ṣadrā (d. 1045/1635–36) as the person who revived the philosophical tradition in Safavid Iran (). Additionally, following Mullā Ṣadrā, Gobineau named and gave short biographical accounts of forty-nine other philosophers (). These reports confirm the existence of a tradition in which philosophy and Ṣūfīsm continued to pass from one generation to another.

In an attempt to describe the group of Shīʿī-Ṣūfī scholars, Murtaḍā Muṭahharī (1919–1979) denies their connection to any Ṣūfī order, instead calling them “scholars who were not members of any formal Ṣūfī order” and who “began to show profound learning in the theoretical ʿirfān of Ibn ʿArabī, such that none from amongst the Ṣūfī orders could match them.”(). According to Muṭahharī, these “individuals” first had high expertise in philosophy and the theoretical Ṣūfīsm of Ibn Arabi, but they were also detached from Ṣūfī orders. It is understandable if some of these individuals had no Ṣūfī affiliations, but the question is whether this claim is all-inclusive regarding these figures.

It is important to note that almost all the masters and followers of the Ṣūfī School of Najaf have been careful not to reveal their Ṣūfī connection, background, and roots. For those familiar with the history of Ṣūfīsm, the reason for such performance within the anti-Ṣūfī dominant environment of the seminary is understandable. Subsequently, I delve into an investigation of the school’s origins, foundations, and interconnections.

2. Research Method

This study conducts a comprehensive analysis of Sufism within the Shia context, employing a historical methodology to discern the origins and foundational sources of subsequent Sufi developments within the Shia seminary. Our research encompasses a thorough examination of a wide array of source materials, including Sufi monographs, travelogues, manuscripts, diaries, and other relevant literature, predominantly in the Persian language. Through this multifaceted investigation, we aim to shed light on the emergence and evolution of Sufi traditions within the contemporary Shia seminary, offering valuable insights into this intricate aspect of Shia scholarship and spirituality.

3. Revival of the Niʻmatullāhī Order

It was during the time of Shāh Sultan Hussain 1694–1722 that the anti-Ṣūfī polemics were dominated by the presence of the three grand jurists in Isfahan, Mashhad, and Qom. Historians of the pre-modern and modern Shīʿī Ṣūfīsm have discussed the revival of the Niʻmatullāhī order after such late Safavid anti-Ṣūfī tendencies. A general description of this era is narrated by Mast ʿAlī Shāh (b. 1780), a Niʻmatullāhī Ṣūfī, in the following terms:

From the middle of Shāh Sulṭān Ḥusayn’s era to the end of Karīm Khān’s, the tradition of Ṣūfīsm was abolished in Iran…For approximately sixty years, Iran was devoid of Ṣūfī doctrines and the subtleties of certitude and no one’s ear heard the name of the spiritual path (ṭarīqat) and no one’s eye saw a person of the spiritual path (ahl-i ṭarīqat)().

This, however, does not describe the whole story of the continuation of Ṣūfīsm and mystical philosophy in post-Safavid Iran or within the larger Shīʿī communities in the Middle East and Indian subcontinent. It also neglects what was happening in closely connected Shīʿī seminaries in Iran and Iraq.

Mathieu Terrier, in his The Defense of Ṣūfīsm among Twelver Shiʿi Scholars of Early Modern and Modern Times () attributes the reinstatement of Ṣūfīsm in 18th-century Iran as “actually established by an outside decision.” In this statement, he is referring to the decision of the then head of the Niʻmatullāhī order, i.e., Riḍā Alishah Dakkānī in 1770, to send Maʿṣūm ʿAlī Shāh (1147/1734) to Iran to revive the order. It is established that the leaders of this order departed from Iran due to the persecution they faced in the latter stages of the Safavid era.

4. Maʿṣūm ʿAlī Shāh Dakkanī and Aqā Muḥammad ʿAlī Kirmānshāhī

Maʿṣūm ʿAlī Shāh Dakkanī’s (b. c. 1147/1734–5, d. end twelfth/eighteenth century) mission was successful in attracting followers in different Iranian and Iraqi religious cities. Nevertheless, he faced strong opposition from Aqā Muḥammad ʿAlī Kirmānshāhī (d. 1216/1801) (), known as the Ṣūfī-killer (Ṣūfī-kush). () This opposition resulted in the issuance of a fatwa and the killing of the Maʿṣūm ʿAlī Shāh Dakanī. The short fatwa indicates that his teaching engendered discontent and corrupt people. Aqā Muḥammad ʿAlī Kirmānshāhī, the one who issued the fatwa, was the son of Muḥammad Bāqir Bihbihānī (known as Waḥīd Bihbihānī), who in turn was the leading Uṣūlī scholar in the Shīʿī seminary in the fight against Akhbāris.

5. Nūr ʿAlī Shāh Iṣfahānī

Nūr ʿAlī Shāh Iṣfahānī (d. 1212/1797), a close disciple and successor of Maʿṣūm ʿAlī Shāh, expanded the Niʻmatullāhī order, in particular among some Shīʿī clerics. As Tabandeh puts it, Sufism in Persia was primarily understood through the practices of wandering dervishes. The Niʿmatullāhī masters recognized this perception, which was unfavorable, and sought to reinvigorate their order by educating people about the unique intellectual and practical aspects of Niʿmatullāhī Sufism. Majdhūb ʿAlī Shāh aimed to promote Niʿmatullāhī philosophy within Shiʿite clerical circles, initiating notable figures like Mullā ʿAbd al-Ṣamad Hamadānī, Mullā Muḥammad Naṣīr Dārābī, and Shaykh Zāhid Gīlānī into the order. ()

Among the mentioned religious scholars, Mullā ʿAbd al-Ṣamad Hamadānī (d. 1216/1801) () was a disciple of the above-mentioned Muḥammad Bāqir Bihbihānī. This historical moment occurred when the Niʿmatullāhī order developed a more elite or scholarly side, even among the scholars in the seminary where some of the Fuqahā constituted opponents of Ṣūfīsm. Hamadānī authored several works on fiqh and uṣūl and other books, chief among them being the Baḥr al-ma’arif (Ocean of Knowledge), dealing with ethics and spiritual wayfaring. He was a Shi’i Mujtahid (jurist) based in Karbala and was eventually killed in the Wahhāis’ attack on the Shīʿī shrine city of Karbala in Iraq that attempted to destroy the shrine of al- Ḥussayn, the third Shīʿī Imam.

6. Baḥr al-‘Ulūm and his Risālah fī Sayr wa al-Sulūk (Treatise on Journey and Spiritual Path)

According to Niʿmatullāhī sources, Mullā ʿAbd al-Ṣamad Hamadānī facilitated several visits between Nūr ʿAlī Shāh Iṣfahānī (the Niʿmatullāhī Shaykh,) and Sayyid Mahdī Ṭabāṭabā’ī (d. 1212/1797), known as Baḥr al-‘Ulūm (Sea of Knowledge/Science). Maʻṣūm ʻAlī Shāh 1970) The latter was a well-known and respected Shīʿī authority. We know that Baḥr al-‘Ulūm did not support an anti-Ṣūfī fatwa that was promoted by a group of anti-Ṣūfī clerics in Karbala. As Litvak puts it,

The ‘ulama’ of Karbala’ appealed to Bahr al-’Ulum to lend his signature to the takfir, to give it greater authority. But, according to Ṣūfī sources, Bahr al-‘Ulum was sympathetic toward the Ṣūfī activists, and arranged for them to leave the shrine cities unharmed().

The significance of this gathering resides in the realization that the favorability towards Baḥr al-‘Ulūm subsequently serves as a rationale for subsequent Shīʿī clerics inclined towards Ṣūfīsm. On the other hand, as much as pro-Ṣūfī clerics tended to affiliate Baḥr al-‘Ulūm with Ṣūfīsm, opponents of Ṣūfīsm made every effort to deny this affiliation. The Risālah Fī Sayr wa al-Sulūk (Treatise on Spiritual Journeying and Wayfaring) attributed to Baḥr al-‘Ulūm is obviously in the Ṣūfī style and primarily discusses practical Ṣūfīsm. This book was commented on by two later prolific Shīʿī scholars, philosophers, and followers of the Ṣūfī school of Najaf, namely, Muḥammad Ḥusayn Ṭabāṭabā’ī (1904–1981) and his disciple Muḥammad Ḥusayn Ḥusaynī Ṭihrānī.1 As Ṭihrānī, in his introduction to Risālah Fī Sayr wa al-Sulūk, indicates, Muḥammad Ḥusayn Ṭabāṭabā’ī transcribed his copy from the author’s (Bahr al- ‘Ulum) own copy.2 As Ṭihrānī narrates, Ṭabāṭabā’ī explained to him, “I have a copy of the treatise based on a very correct version of the manuscript that I have transcribed with my own hands.” Ṭabāṭabā’ī then acknowledges that,

I came across a copy of the treatise when I was studying in Tabriz, from which I made my own transcription, although that version had many mistakes. When I had the grace to go to Najaf, I found that my master, the late Āyatullāh Sayyid ʿAli Qāḍī, had a copy of the treatise that was very similar to mine…Later on, I found a very correct version of the treatise, which was written in beautiful handwriting …it was the copy of my astronomy and mathematics teacher, the late Sayyid Abū al-Qāsim Khūnsārī. Thus, I borrowed his copy and transcribed it in 1354 AH (1936 CE). His copy was transcribed ninety years before that time().

In addition to Ṭihrānī’s discussion on the matter in his introduction, this quotation informs us that Baḥr al-‘Ulūm’s Risālah fī Sayr wa al-Sulūk was circulated and copied by scholars during and after his life. Ṭabāṭabā’ī transcribed his copy in 1936 from a copy that was transcribed ninety years before that in 1846. This is about forty-nine years after its author died in 1797.

Both Muḥammad Ḥusayn Ṭabāṭabā’ī (1904–1981) and Ḥusaynī Ṭihrānī attributed significance to this treatise, leading them to produce commentaries on it. Risālah fī Sayr wa al-Sulūk provides both guidance and an overview of the spiritual journey. Shahram Pazouki contends that Baḥr al-‘Ulūm composed this treatise after his encounter with Niʿmatullāhī Shaykh, Nūr ʿAlī Shāh Iṣfahānī. Historical records do not substantiate whether Baḥr al-‘Ulūm underwent initiation into the Niʿmatullāhī order. However, the treatise’s content exhibits a noticeable affinity with the teachings of the order. The author’s treatise highlights the essential role of a spiritual guide for a wayfarer, indicating that if the author himself was a “Sālik,” he likely had a guiding master on his spiritual journey. As he puts it,

A wayfarer is never without the need of the particular (Khāṣṣ) master, even if he achieves his desired destination. That is because even the destination that he has reached has certain rites and manners that should be observed, and these rites and manners are taught by none other than the particular master. No matter how high is the realm that the wayfarer achieves, it is still under the guardianship of the particular master. Thus, the companionship of the particular master is a universal requirement for every stage of the journey. Even at the last stage of the journey, where the manifestation of the Divine Names and Essence occurs, the particular master is present().

While Baḥr al-‘Ulūm’s Risālah Fī Sayr wa al-Sulūk serves as a guidebook for spiritual seekers, critics of Ṣūfīsm, along with certain pro-Ṣūfī clerics, cast doubt on the authenticity of the treatise’s final section. This section relates a description of Ṣūfī practice in the request for a blessing from the spirituality of Mercury. Its author mentions that he used to resort to the spirituality of Mercury, and he adds that,

indeed, those initiated into esoteric knowledge draw assistance from the ethereal essence of Mercury. It is prudent for neophytes to observe Mercury’s celestial presence, ideally after sunset and before sunrise when its luminance graces the horizon. Initiating this observation, the practitioner is advised to offer a greeting of “Salaam” to the celestial body, followed by a step back, wherein the recitation continues:Oh, Mercury! Long have I yearned and sighed,Through days and nights, for your presence to abide.Now, here I stand, seeking your guiding light,Grant me aid in my quest from dark to sight.Stepping back once more, a whispered appeal,By heavenly decree, unravel the key.Bestow upon me blessings, rich and clean,Lord of earth and heaven, let abundance assured().

Opponents state that this practice does not follow the taste of religion, and even if the treatise is attributed to Baḥr al-‘Ulūm, this section is not from him. In fact, the transcriber added his own experience right at the end of the treatise. This confused some readers. The transcriber did not identify himself except by saying that he was the father of Sayyid Muṣṭafā Khawansārī. Yet, another hint may help us to identify the transcriber. When Maʿṣūm ʿAlī Shāh, in his Ṭarāiq al- Ḥaqāīq, mentions the life and works of a Niamatullahī Ṣūfī, Raḥmat AliShāh, who composed a short treatise in response to a question about the unity of being (Waḥdat al-Wujūd) written in 1247/1831, he adds that “and I saw his transcription of Baḥr al-‘Ulūm’s Risālah Fī Sayr wa al-Sulūk in Ṣūfīsm (ʿIrfan) where he also added a description of his Arbaʿīnīyyat (Forty Days of Spiritual Retreat)”. (). This narration sheds light on the ambiguity of the Mercury prayer in Baḥr al-‘Ulūm’s Risālah Fī Sayr wa al-Sulūk and who might be the possible author of it.

7. Mullā ʿAbd Al-Ṣamad Hamadānī and the Question of the Origin of the Ṣūfī School in the Shīʿī Seminary

Shahram Pazouki, in his entry on Mullā ʿAbd al-Ṣamad Hamadānī, tried to identify ʿAbd al-Ṣamad Hamadānī and Baḥr al-‘Ulūm as the originators of this Ṣūfī movement in the seminary. He refers to the visits mentioned between Baḥr al-‘Ulūm and Nūr ʿAlī Shāh Iṣfahānī, using Baḥr al-‘Ulūm’s Risālah fī Sayr wa al-Sulūk to make this connection. Pazouki states that,

Through Hamadhānī, a particular type of Ṣūfism developed among certain Shīʿī ʿulamāʾ, although, due to the opposition which grew to Ṣūfism from the middle of Ṣafavid rule among most of Shīʿī ʿulamāʾ, they chose to speak of ʿirfān (gnosis) rather than of taṣawwuf (Ṣūfism). One of the main figures of this type of Ṣūfism was Mullā Ḥusayn Qulī Hāmādanī (d. 1311/1893). ʿAllāmah Ṭābāṭabāʾī (d. 1402/1982), [the] author of the famous al-Mīzān commentary of the Qurʾān, was a contemporary follower of this way().

Pazouki accurately acknowledges the presence of a Ṣūfī movement within the seminary. However, his assertion that Mullā ʿAbd al-Ṣamad Hamadānī initiated the formation of this “specific” movement, denoted as the “Ṣūfī school of Najaf,” is not in alignment with historical accuracy. It is imperative to acknowledge that the scholarly works of both Mullā ʿAbd al-Ṣamad Hamadānī and Baḥr al-‘Ulūm found mention within the writings of scholars associated with the Ṣūfī school of Najaf. Despite this, there is no direct link between Mullā ʿAbd al-Ṣamad Hamadānī and them. While Mullā ʿAbd al-Ṣamad died in 1216/1801, Sayyid Ali Shūshtarī, as the great master of the Najaf order, died in 1281/1864 (Figure 3). Apart from the absence of any historical evidence or record of relationships between these two, it is hard to imagine a meeting based on the dates mentioned. First, Shūshtarī was very young at the time. Secondly, he entered the Najaf Seminary while already known as a well-versed scholar in his city of origin, Shūshtar in Iran.

Based on what has been discussed, it is evident that the Niʿmatullāhī order had contacts and members amongst clerics in the Shīʿī seminary and that the Niʿmatullāhī works were valuable for those pro-Ṣūfī religious scholars. Yet there is no historical evidence that this order was the root of the Ṣūfī order in the Shia seminary, namely the Ṣūfī school of Najaf.

Figure 1.

The pre-modern Niʻmatullāhī order revival in Iran.

8. Post-Sadra Dhahabīyya Ṣūfī Order and Shīʿī-Ṣūfī Convergence

We already mentioned the existence of post-Sadrian Ṣūfī-philosophers who promoted Sadra’s interpretation of religion, presenting an interrelated version of Shīʿīsm and Ṣūfīsm. We also discussed the revival of the Niʿmatullāhī Ṣūfī order to investigate the aforementioned tradition and to uncover its possible relationship to the Ṣūfī School of Najaf in the Shīʿī seminary.

9. The Kubrawīyya Order, Kubrā, and Ismāʿīl Qaṣrī

In what follows, we shall study the continuation and developments of the Dhahabīyya order in Iran. In fact, the Dhahabīyyais represented a continuation of the Kubrawīyya order. Yet, before entering into our Dhahabīyya discussion, it is worth mentioning some recent scholarship on the Kubrawīyya order. Despite some scholars connecting Najm al-Dīn Kubrā (d. ca. 618/1221) to the Suhravardīyya order, thereby regarding Kubrawiyya as a branch of the Suhrawardian genealogy, Aydogan Kars, in his Ismāʿīl al-Qaṣrī, Kubrawiyya and Ṣūfī Genealogies, draws attention to a potentially overlooked correlation and critiques prior scholarly discourse as a “misidentification of Kubrawiyya as an offshoot of Suhrawardiyya”(). Furthermore, he articulates that “the authentic spiritual genealogy of the Kubrawiyya is yet to be identified”(). What is essential in our discussion is that in his identification of the spiritual chain of Najm al-Dīn Kubrā, he reminds us about the neglected mark of Khuzestan in the Western scholarship on the Kubrawīyya order. Khuzistan is a province located in the southwest of Iran. It is not only, as Kars states, critical in the identification of Kubrā’s Ṣūfī connection, but it is also significant in the study of the Ṣūfī School of Najaf, as we will see in the coming pages. Ismāʿīl Qaṣrī is the central figure that Kars focuses on as Kubrā’s master and the one who passed him “the foremost robe of discipleship” (Khirqayi Aṣl). Today, Qaṣrī’s graveyard has been restored and is now located in the old bazaar of Dezful, a historic city in Khuzistan province.3 As Kars relates,

In his Shajaranāma, Aẕkānī [690–778/1291–1376] states that Kubrā had three masters, all of whom were pupils of Abū al-Najīb. He notes that al-Qaṣrī had a different chain of transmission through Kumayl, and quickly moves to introduce the names in al-Bidlīsī’s Abū al-Najīb-based genealogy().

Kars argues that Ḥusayn Khwārazmī (d. ca. 839/1436) is the one who ignored Qaṣrī’s role in Kubrā’s Ṣūfī chain or silsila. Kubrā and his disciple had mentioned the Qaṣrī lineage in their silsila.4 An essential aspect of the Qaṣrī linage is the presence of Kumayl, b. Ziyād Nakhaʾī, killed in 81/701. Kumayl was a significant figure in Shīʿī Islam and a loyal companion to Ali. There is a conversation attributed to him and Ali, known as hadith al-ḥaqīqa (the Truth), and a long supplication, known as “Duʿāʾ al-Kumayl” that Ali taught to him. It is well established that the hadith al-ḥaqīqa (the tradition of reality) has garnered commentary from a multitude of scholars who share a common affinity for both philosophy and Ṣūfīsm. Moreover, Kumayl plays an essential role in connecting many Ṣūfī orders to Ali and thus to the Prophet, among them Kumaylīyya and Kubrawīyya or Dhabīyyah. I posit that the inclusion of Kumayl adds heightened significance to the lineage of this order, particularly when viewed from a Shīʿī perspective. Therefore, we can interpret the continuation of the Kubrawīyya order in Iran, known as Ẕahabiyya/Dhahabīyya, as occurring within a more general Shīʿī superstructure. Yet, we do not intend to discuss the emergence and early developments of the Kubrawīyya order here. Instead, we try to identify any connection between the Dhahabīyya order in its later period and the Ṣūfī School of Najaf.

10. Revival of The Dhahabīyya Order in Iran after the Safavid Era

We shall focus here on the development of the revival of the Dhahabīyya order in Iran after the Safavid era. We know that Barāzishābādī (d. 872/1467-68) and his disciple Sayyid Aḥmad Lālā are a starting point for turning the Kubrawīyya into the Dhahabīyya order and changing its geographic focus from Central Asia to Iran. Yet, DeWeese, in his Studies on Ṣūfīsm in Central Asia, states that a significant ambiguity exists regarding the time it became Shīite (). Lewisohn, in his An Introduction to the History of Modern Persian Ṣūfīsm, states that the Dhahabīyya order’s revival in Iran took place several decades earlier than the Niʿmatullāhī order. He indicates that this revival happened,

through the person of Quṭb al-Dīn Nayrīzī (d. 1173/1759), the thirty-second in line from the Prophet. Nayrīzī was well versed in all of the various Islamic sciences of his day, and among his followers are counted a number of notable Shīʿīte clerics, such as Shaykh Ja’far Najafi, Mulla Miḥrab Gīlānī, Shaykh Aḥmad Aḥsāʾī and Sayyid Mahdī Ṭabāṭabāʾī (Baḥr al-‘Ulūm)().

We already discussed Baḥr al-‘Ulūm (d. 1212/1797) and the Risālah Fī Sayr wa al-Sulūk attributed to him. Lewisohn, in his footnote, adds that Khāvarī, in his Dhahabīyya, casts doubt on whether the last two had met him (). On the other hand, Anzali, in his The Emergence of the Ẕahabiyya in Safavid Iran, based on his manuscript studies, informs us that,

the official spiritual lineage of the order (the mashīkha) is likewise a late eleventh/seventeenth-century construction, a product of the joint efforts of the Ẕahabi master Muʾaẕẕin Khurāsānī (d. 1078/1668) and his disciple, Najīb al-Dīn Zargar Iṣfahānī (d. ca. 1108/1696–7)().

Both of the previously mentioned masters from Anzali had established their presence prior to the era of Quṭb al-Dīn Muḥammad Nayrīzī (d. 1173/1795). At any rate, for the purpose of this research, it is significant that all historians of the Dhahabīyya order agree that Nayrīzī, with his powerful and charismatic personality, played an essential role in the revival of the order in Iran in the late Safavid period. There is a lineage in the tradition of Islamic philosophy that connects Nayrīz to Mulla Sadra ().

11. Nayrīzī and Bīdābādī

Quṭb al-Dīn Muḥammad Nayrīzī’s (d. 1173/1795) works represent without a doubt another instance of his fused Shīʿī-Ṣūfī understanding. He was not solely a Ṣūfī master; rather, he encompassed the roles of a scholar and educator (i.e., among his disciples was Āqā Muḥammad Bīdābādī (d. 1197/1783)). Both Shīrazī in his Ṭarāʾiq and Khāverī in Dhahabīyya confirm Bīdābādī’s connection to Nayrīzī. His contemporary, Mīrzā Muḥammad Akhbārī Nīsābūrī, refers to him as a philosopher, mystical sage (ʿārif), and trustworthy narrator of hadiths. Bīdābādī’s intriguing aspect lies in the prevalent motif across most of his writings, which portrays him as a spiritual mentor. He pursued his studies within the seminary and exhibited remarkable proficiency in religious sciences. Ḥabībābādī, in his Makārim al-āthār (Noble Traits), calls Mulla Ali Nūrī a philosopher concerned with theology (ḥukamāʾ-i ilāhiyyīn).5 The same source informs us that Nūrī studied in the city of Isfahan with Āqā Muḥammad Bīdābādī (d.1197/1783). It is important to mention that Nūrī, as one of the most prominent revivers of Sadrian philosophy, was the teacher of Mullā Hādī Sabzavārī (d.1289/1873), whose school of philosophy and Ṣūfīsm in Sabzavar remained a formative force in shaping an important era of intellectual activity in the history of philosophy and Ṣūfīsm. This relationship places Mullā Hādī among those who can be considered at least followers of the Dhahabīyya order.

As mentioned earlier, an important dimension of Bīdābādī’s oeuvre was his mystical philosophy and theology. A number of his treatises correspond with other scholars who asked him for Dastūr al-ʿamal (Letters to Followers Indicating the Path to Spiritual Perfection). He was connected to the Dhahabīyya order through Nayrīzī. His Ādāb al-sayr wa al-sulūk and Du risāla dar sayr wa sulūk (two treatises on journey and spiritual path) are of the nature of Dastūr al-ʿamals. ʻAlī Ṣadrāʼī, in his Taz̲kirat al-sālikīn: nāmahʹhā-yi ʻirfānī-i Āqā Muḥammad Bīdʹābādī (Remembrance of the Seekers: Mystical Letters of Āqā Muḥammad Bīdʹābādī), collected Bīdābādī’s letters with eighteen of his contemporaries. In some of those letters, he teaches them a number of Arbaʻīnāt.6 One of those letters was written in response to a request of Sayyid Ṣadr al-Dīn Kāshif al-Dizfūlī (1760–1842) for a mystical invocation (Dhikr) (, ). There also existed a collection of his manuscripts written to Ṣadr al-Dīn Kāshif al-Dizfūlī. Unfortunately, we do not have any information about their whereabouts now.

12. Ṣadr al-Dīn Kāshif al-Dizfūlī

Ṣadr al-Dīn Kāshif al-Dizfūlī (1174/1760–1258/1842) (Sayyid Kāshif) played an essential role in the development of the Ṣūfī School in the Najaf Seminary. He explicitly asserts that he attained the level of Ijtihād in Islamic studies and completed his education at age 21. () This indicates his extraordinary intellectual ability, which prompted his father to invite him from the seminary in Najaf to Kermanshah in the west of Iran. His temporary residency in Kermanshah was troublesome for him. We already mentioned that Aqā Muḥammad ʿAlī Kirmānshāhī (d. 1216/1801), known as the Ṣūfī-killer (Ṣūfī-kush), established a solid anti-Ṣūfī movement that cost the life of the Niʿmatullāhi master Maʿsūm ʿAli Shāh. It appears that Sayyid Kāshif’s treatise, namely, Miṣbāḥ al-ʻārifīn (), presented his allegiances in a Ṣūfī light. This was enough for Kirmānshāhī and his followers to accuse Sayyid Kāshif of an affinity to Ṣūfīsm, which constituted, in their eyes, a deviation from the teaching of Islam. We do not have details of this incident. Yet, we know that Sayyid Kāshif wrote his Risālah Qāṣim al-Jabbārīn in response to those accusations.

As previously indicated, the sanctuary of Ismāʻīl Qaṣrī is situated in Dezful. Sayyid Kāshif also resided in the same city, guiding disciples and adherents along the spiritual journey. A descendent of his, namely Sayyid Ali Kamāli Dizfūlī (1329/1911-1426/2005), in his ʻirfān va sulūki Islāmī, provides a history of Sayyid Kāshif’s family. In his account, we learn that the family was replete with religious scholars and Sayyids descending from the seventh Shīʿī Imam, Musā al-Kāẓim and possessed a proclivity towards Ṣūfīsm. () Furthermore, it is noteworthy that Sayyid Kāshif’s family is recognized in Iran by the title “Sādāti Gūshih.”7 Notes about him acknowledge his simple and contented life, avoiding all luxury.

Sayyid Kāshif was held in high regard among the people, and the Iranian king of the time, Fatḥʿalī Shāh Qājar (1772–1834), visited him. Some court members respected Sayyid Kāshif, but simultaneously, he had opponents among scholars and local governing officials.

Most of the over sixty treatises attributed to () Sayyid Kāshif remain unpublished and are preserved in multiple libraries and collections in Iran. His Miṣbāḥ al-ʻārifīn is an exploration of the Ṣūfī path and practices. The subject of his other work, namely Ḥaqq al-ḥaqīqah li-arbāb al-ṭarīqah (The Truth of the Truth for the Masters of the Path), once again centers on the importance of the spiritual wayfaring with emphasis on Shīʿī doctrines and explanations of Ṣūfī terminology.

Rizvi, in his chapter on Mullā ʻAlī Nūrī, a disciple of Bīdābādī, very briefly mentions Sayyid Kāshif and states that he was “a renowned mystic associated with Dhahabī order who also did much to spread ʻIrfiān in the shrine cities of Iraq” (). Rizvi, however, does not provide more details on how Sayyid Kāshif caused the spread of ʻIrfiān in the shrine cities of Iraq, in which the main Shīʿī seminaries were located. To explain some key points, we must emphasize Sayyid Kāshif’s numerous visits to those cities and, consequently, the seminaries and scholars there. Secondly and more importantly, we should emphasize his particular relationships with two significant individuals who later reached the highest rank in their fields and are widely revered until today in the Shīʿī communities and beyond.

These two figures are Sayyid ʻAlī Shūshtarī (d. 1281/1866–67) and Shaykh Murtaḍā Ansārī (1214/1799–1281/1864). Both individuals were born in Dizfūl, the same city where Sayyid Kashif was living and where he attended seminary for the introductory levels. At that time, Sayyid Kāshif was a known Ṣūfī master and religious scholar. Their relationship with Sayyid Kāshif is one of the main impetuses for the founding of the Ṣūfī/ʻIrfiānī school in the Najaf Seminary. The emergence and expansion of the Ṣūfī School of Najaf as reflected by its diverse array of masters and their explication of complex Ṣūfī and philosophical ideas.

13. Conclusions

It can be broadly inferred that throughout their historical trajectory, Ṣūfī orders typically established their distinct institutional frameworks. On the other hand, scholars of religion (or those deemed to be ‘Ulemā’/experts of religious sciences) also had their own communities of learning termed the al-Hawzat al-ʿIlmīyyah (seminaries). However, both groups dealt with the same Qurʾānic revelation and its attendant religious sciences; their distinct approaches to interpreting those resources rendered them unequivocally distinct. While the ‘Ulema’ accused Ṣūfīs of merely tolerating the religious Law or having deviated from the righteous path, Ṣūfīs in return, accused ‘Ulemā of holding onto the outer dimensions of Islam. Yet, there have also been attempts to reconcile the two currents in history, such as in the thought of Sayyid Ḥaydar Āmulī (b. 720/1320). Āmulī stressed the notion of convergence between Shīʾīsm and Ṣūfīsm. His application of common concepts such as wilāyah and reference to the inner meanings of revelation in both schools, at least for some scholars, demonstrates the proximity of the two currents of thought and the need to rethink their unity.

This paper has studied the roots, history and emergence of Sufi trends within the contemporary Shia seminaries by examining post-Ṣadrā figures and movements. It does appear, however, that these seminarians and mystics were inclined to conceal their Ṣūfī affiliation. The reasoning behind this is relatively straightforward, namely the existence of powerful opposition to the Ṣūfīs along with philosophical methods in the interpretation of revelation and hadith amongst the ʿUlemā. The Shah and his court had occasionally backed that opposition. Therefore, the Ṣūfīs had no choice but to conceal their identities within the Shīʿī seminary to protect both the continuity of their Ṭarīqa (order) and their mystical approaches to revelation and law. Therefore, when contemporary historians refer to the Ṣūfī School of Najaf, they provide the following linage, with no extra affiliations and information:

Mullā Qulī Jūlā (an unknown mysterious individual) > Sayyid ʿAlī Shūshtarī (d. 1281/1866–67) > Akhund Mullā Ḥusayn-Qulī Shavandī Hamadānī (1239/1824–1311/1894) > Shaykh Muḥammad Bahārī (1265/1849–1325/1907); Mīrzā Jawād Aqā Malikī Tabrīzī (d. 1343/1924–25) and Sayyid Aḥmad Karbalāʾī (d. 1332/1914)> Sayyid Ali Qāḍī (1866–1947)> Tabātabāʾī (1904–1981).()

By examining the revival of the Niʻmatullāhī and Dhahabīyya Ṣūfī orders, we traced back the connections between Sufis and jurists. We learned that Sayyid Kāshif, disciple of Āqā Muḥammad Bīdābādī, was a significant figure in promoting the Sufi thought and practice in the seminary. He inspired both Sayyid ʻAlī Shūshtarī (d. 1281/1866–67) and Shaykh Murtaḍā Ansārī (1214–1281/1800–1865). We can speculate that Sayyid ʻAlī Shūshtarī must have been one of the khalifas of Sayyid Kāshif. There are indications of this claim in the stories narrated by some of the followers of Sayyid Kāshif. Shaykh Murtaḍā Ansārī was the most eminent figure in the Shī‘ī seminary and Shī‘īte Islam as a whole in the 13/19th century. Hairi’s description of Ansārī’s position in the Shī‘ī seminary can help us to better understand and place the following account of the relationship between Ansārī’ and Sayyid Kāshif. “Despite being rather unknown in the West, he is considered to have been a S̲h̲īʿī mud̲j̲tahid whose widely-recognized religious leadership in the S̲h̲īʿī world has not yet been surpassed.”(). The account of the meeting between Anṣārī and Sayyid Kāshif is narrated in different sources. Sayyid Ḥusayn Ẓahīr al-Islām (1274/1858–1337/1919) in his Rashaḥāt nūrīyya and Sayyid ʻAlī Sayyid in his introduction to Sayyid Kāshif’s Ḥaqq al-ḥaqīqah li-arbāb al-ṭarīqah narrate this visit. This indicates a connection between Sayyid Kāshif as a Dhahabīyya Shaykh (who also was a religious scholar) with the eminent figure of the seminary.

“When Shaykh Murtaḍa Anṣārī decided to move to Najaf from Dezful to pursue his advanced studies in the seminary, he thought that it would be better to get mystical advice and dhikr from Ṣadr al-Dīn Kāshif al-Dizfūlī and ask for his blessing and commands for dhikr and fikr [meditation]…. Kāshif prays for him and adds that, “because your intention from travel is the gaining knowledge, an endowment in knowledge is a worship per se. Nevertheless, be sure that you will advance this [dhikr and fikr] through Sayyid ʻAlī Shūshtarī in Najaf, who is from us.”8

This story reveals Sayyid Kāshif as a known and respected spiritual man and, more importantly, names Sayyid ʻAlī Shūshtarī as a mediator and spiritual master for Ansari. There are many narrations of how Shūshtarī and Ansārī, who later moved to Najaf, were connected. This was indeed the beginning of the creation of the Ṣūfī School of Najaf.

The historical background and developments discussed in this paper expand our knowledge regarding those individuals and schools by insisting on the coeval nature of Shiism and Ṣūfīsm.

Finally, moving from the historical roots of this fissure and little-known thinkers prefiguring more recent debates, we examined the origins and history of the Ṣūfī and philosophical school of Najaf in addition to the late and post-Safavid eras in Iran. This investigation led our research into the following three areas pertaining to (A) the dominance of the fiqhī-centered and anti-Ṣūfī environment in the Shī‘ī seminary on the one hand and (B) the re-emergence of the Niʻmatullāhī and (C) Dhahabīyya Ṣūfī orders in Iran on the other. Furthermore, our exploration has underscored the substantial role played by the three aforementioned regions in the formation of both Ṣūfī and anti-Ṣūfī schools within the context of the Shī‘ī seminary. The Ṣūfī facet within this school tends to remain predominantly inconspicuous, primarily in response to the accusations and hostilities of opposing factions. On certain occasions, mentors and followers were compelled to disavow their affiliations publicly.

Figure 2.

Post-Sadra Dhahabīyya Order.

Figure 3.

The Sufi School of Najaf.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | It is also being thought by the contemporary Sufi minded clerics. |

| 2 | Ṭihrānī explains how he arrived at different copies of the original manuscript. For more, see (). See also (). |

| 3 | In his written works, Muḥammad Ḥusayn Ḥikmatfar elucidates his dedicated efforts spanning three decades towards the restoration and revitalization of Qaṣrī’s khaniqāh and cemetery in Dezful. For references pertinent to our discourse, see (). See also (). |

| 4 | Our present intention does not encompass delving into the origins of the Kubrawīyya order. Nevertheless, certain Shīʿī scholars endeavor to suggest the existence of an obscured Shīʿī facet within the Kubrawīyya order. |

| 5 | For more on Nūrī, see (). Additionally, Sajjad Rizvi, in his chapter on Mullā ʿAlī Nūrī narrates that the Niʿmatullāhī Ṣūfī Muḥammad Jaʿfar Kabūdarāhangī, known as Majdhūb ʿAlī-Shāh (d. 1238/1823), indicates that “the Bīdābādī circle was renowned for their mystical and spiritual practices (riyāḍat u mujāhada-yi nafsānī) alongside their ʿirfān (mystical) orientation in their study of metaphysics.” See (). |

| 6 | Forty days of prayer and seclusion are a particular demand on those committed to Sufism. The Qurʾānīc root of this exhortation is indicated in the story of Moses and his forty nights of seclusion. It is sometimes called “Arbaʿīn Kalīmī” to refer to its prophetic tradition. |

| 7 | Refering to Gūshah village in north Dizfūl in Iran where their first great grandfather Sayyid Kamāl al-Dīn Walī (b. 975/1568), who migrated from Medina, is buried. Several of his descendants who were religious scholars were affiliated to the Dhahabīyya order. For more on this family, see ( ()). |

| 8 | (). Ḥaqq al-ḥaqīqah li-arbāb al-ṭarīqah.. The account of this meeting also narrated by Ẓahīr al-Islām Dizfūlī, in his Rashaḥāt-i nūrīyya. It should be noted that Ẓahīr al-Islām (1274/1858–1337/1919) himself was a Dhahabī Shaykh in Dizfūl as well as a mujtahid in Shī‘ī religious studies. |

References

- Anzali, Ata. 2013. The Emergence of the Ẕahabiyya in Safavid Iran. Journal of Sufi Studies 2: 149–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghari, Seyed Amir Hossein. 2021. Replacing Sharīʿa, Ṭarīqa and Ḥaqīqa with Fiqh, Akhlāq and Tawḥīd: Notes on Shaykh Muḥammad Bahārī (d. 1325/1907) and His Sufi Affiliation. Journal of Sufi Studies 9: 202–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baḥr al-ʻUlūm, Sayyid Muhammad Mahdi. 1388. Risālay-i Sayr va Sulūk Mansūb bi Baḥr al-ʻUlūm. Edited by Sayyid Muḥammad Ḥusaynī Ḥusaynī Ṭihranī. Mashhad: ʿAllāma Ṭabāṭabāʾī. [Google Scholar]

- Baḥr al-ʻUlūm, M. a. M. i. M. a. 2013. Treatise on Spiritual Journeying and Wayfaring. Edited by Sayyid Muḥammad Ḥusaynī Ḥusaynī Ṭihranī. Translated by Tawus Raja. Chicago: Kazi. [Google Scholar]

- Bayat, Mangol. 1982. Mysticism and Dissent: Socioreligious Thought in Qajar Iran. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bayat, Mangol. 2020. ʿABD-AL-ṢAMAD ḤAMADĀNĪ. In Encyclopaedia Iranica Online. Leiden: Brill, pp. 161–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bīdābādī, Muhammad Ali. 2011. Taz̲kirat al-sālikīn: Nāmahʹ hā-yi ʻirfānī-i Āqā Muḥammad Bīdʹ ābādī. Qum: Intishārāt-i Khūyī. [Google Scholar]

- De Gobineau, Arthur. 1923. Les Religions et les Philosophies dans l’Asie Centrale. Paris: Didier et cie. [Google Scholar]

- DeWeese, Devin. 2012. Studies on Sufism in Central Asia. Farnham: Ashgate Variorum. [Google Scholar]

- Hairi, Abdul-Hadi. 2012. ANSARI. In Encyclopaedia of Islam, 2nd ed. Edited by Bosworth Bearman and Heinrichs E. van Donzel. Leiden: Brill, p. XII:75a. Available online: http://referenceworks.brillonline.com/entries/encyclopaedia-of-islam-2/ansari-SIM_8341 (accessed on 15 April 2021).

- Ḥikmatfar, Muhammad. Ḥossein. 2015. ʻĀrifī bar kharābahʹhā-yi Jundī Shāpūr: Taz̲kirah-i Shaykh Abū al-Qāsim ibn Ramaz̤ān Balkhī Jawzī maʻrūf bih Shāh Abū al-Qāsim, 1st ed. Dezful: Intishārāt-i Dār al-Muʼminīn. [Google Scholar]

- Imāmahwāzī, Muhammad Ali. 1413. Khāndāni Sādāti Gūshah. Dezful: Hiyati Nāshirāni Mushajjariyi Khāndāni Sādāti Gūshah. [Google Scholar]

- Kamālī Dizfūlī, Seyed Ali. 1368. ʻIrfān va Sulūki Islāmī. Tehran: Rūdakī. [Google Scholar]

- Kars, Aydogan. 2021. Ismāʿīl al-Qaṣrī, Kubrawiyya, and Sufi Genealogies: “Deep-Dark Transmissions” in Medieval Iran. Iranian Studies, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kāshif al-Dizfūlī, Seyed Ali. 1385. Mirʾāt al-ghayb: Bih hamrāh-i Ḥaqq al-ḥaqīqah li-arbāb al-ṭarīqah, 1st ed. Tehran: Bāztāb. [Google Scholar]

- Kāshif al-Dizfūlī, Ṣadr al-Dīn. 1335. Ḥaqq al-ḥaqīqah li-arbāb al-ṭarīqah. Ahvāz: Ṣāfī. [Google Scholar]

- Lewisohn, Leonard. 1999. An Introduction to the History of Modern Persian Sufism, Part II: A Socio-Cultural Profile of Sufism, from the Dhahabī Revival to the Present Day. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 62: 36–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvak, Meir. 1998. Shiʻi scholars of nineteenth-century Iraq: The ʻulama’ of Najaf and Karbala’. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Maʻṣūm ʻAlī Shāh, Muḥammad Maʻṣūm Shīrāzī. 1970. Ṭarāʾiq al-ḥaqāʾiq. Edited by Muḥammad Jaʻfar Maḥjūb. Tehran: Kitābkhānahʼi Sanā‘ī, Vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Matthijs, van den Bos. 2019. Dakanī, Maʿṣūm ʿAlī Shāh. In EI.3. Leiden: Brill. Available online: https://referenceworks.brillonline.com:443/entries/encyclopaedia-of-islam-3/dakani-masum-ali-shah-COM_25827 (accessed on 20 May 2022).

- Muʻallim Ḥabībʹābādī, Muhammad Ali. 1958. Makārim al-athār dar ahvāl-i rijāl-i dawra-i Qājār. Isfahan: Matbaʻa-i Muhammadi. [Google Scholar]

- Muṭahharī, Murtaḍā. 1999. Majmūʿa-yi āthār-i Shahīd Mutahharī. Tehran: Intishārāt-i Ṣadrā, Vol. 23. [Google Scholar]

- Pazouki, Shahram. 2012. ʿAbd al-Ṣamad Hamadhānī. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Pourjavady, Reza. 2018. Philosophy in Qajar Iran. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadra’i Khūʼī, ʻ. Ali. 1391. Āshnā-yi ḥaqq: Andīshah va raftārhā-yi sulūkī-i Āqā Muḥammad Bīdābādī, 1st ed. Edited by M. s. a.-S. Zanjānī. Intishārāt-i Khūyī. [Google Scholar]

- Rizvi, Sajjad. 2018. Mullā ʿAlī Nūrī. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabandeh, Reza. 2022. Rise of the Nimatullahi Order: Shi’ite Sufi Masters Against Islamic Fundamentalism in 19th-Century Persia. Leiden: Leiden University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Terrier, M. 2020. The Defense of Sufism among Twelver Shiʿi Schilars of Early Modern and Modern Times. In Shi’i Islam and Sufism: Classical Views and Modern Perspectives. Edited by Denis Hermann and Mathieu Terrier. London: I. B. Tauris. [Google Scholar]

- Ẓahīr al-Islām Dizfūlī, Muhammad Reza. 2016. Rashaḥāt-i nūrīyah. Edited by Muḥammad Ḥusayn Ḥikmatʹfar. Dezful: Dār al-Muʼminīn, Armaghān-i Tārīkh. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).