Abstract

Within the cultural integration of Indian Buddhist art and Chinese Buddhist art, standing Buddha statues carved in-the-round with thin, tight-fitting robes require special attention. Unlike other types of Buddha statues found in China, they are depicted wearing robes of a foreign style, while displaying the facial and body features of East Asians. These statues, which were excavated on the Shandong Peninsula in the last century, are believed to have been carved during the Northern Qi Dynasty (550–577). After years of academic exploration, the transmission route, transit point and reasons for their introduction into Shandong remain unclear, which are topics that this paper aims to address. According to typology analysis, the Buddha statues in question can be divided into three types, and their foreign counterparts have been identified through the iconology comparisons of Chinese and foreign Buddha statues. From this, in chronological order, the transmission route of three Buddha statue types can be inferred, namely from India to the Shandong Peninsula via the Malay Peninsula, the Mekong Delta and the southeastern coast of China. The route of contemporaneous Indian monks travelling from the east to the Northern Dynasties, as recorded in Chinese historical documents and the Buddhist Canon, verifies this conclusion. Along this route, the north-central Malay Peninsula is one of the main transit points where the Buddha statues were locally adapted and then spread further east.

1. Introduction

From the 5th to the 6th century, there were frequent maritime exchanges between Southeast Asia and the Southern Dynasties, which included the cultural communication of Buddhism (Ren 2015, pp. 129–32). Based on Chinese literature and stone inscriptions, previous research initially uncovered the main trade routes from the ancient Southeast Asian kingdoms to China during the Southern and Northern Dynasties and developed a more comprehensive understanding of the Mekong Delta and the Malay Peninsula as the important transportation hubs (Pelliot 1903, pp. 248–303; Feng 2017, pp. 175–94; Chen 1992, pp. 95–108; Han 1991, pp. 219–68; Shi 2004, pp. 35–48). At the end of the 20th century, a large number of standing Buddha statues carved in-the-round with thin, tight-fitting robes were unearthed at the sites of the Mingdao Temple 明道寺 (Linqu, Shandong Province), Zhucheng (Shandong Province) and Longxing Temple 龍興寺 (Qingzhou, Shandong Province), among others (Shandong Linqu Shanwang Paleontological Fossil Museum 2010; Ren 1990; Du 1994; Xia 1998). They are also known as Qingzhou-style Buddha statues. It has gradually become clear that the direct source of the Qingzhou style are the locally adapted India-originating statues in Southeast Asia (Soper 1960; Jin 1999a, p. 25; Jin 1999b, p. 8; Jeong 1999, pp. 108–23; Yagi 2013, pp. 140–69; Kang 2013, pp. 39–60; Zhao 2018, pp. 92–98), and scholars have paid more attention to the transmission routes of Buddhism from Southeast Asia to the Northern Dynasties during this period through these finds (Jacq-Hergoualc’h 2002, pp. 143–60; Howard 2008, pp. 70, 76–77; Kang 2013, pp. 39–60; Zhao 2016, pp. 33–46). There is relatively in-depth research regarding the interactions and similarities between the Southern Liang (502–557) statues and statues of the Fu-nan Kingdom (1st to mid-7th century) located in the Mekong Delta (Yao 2016, pp. 269–97).1 However, previous studies that use the Qingzhou-style statues to explore transmission routes do not include a separate discussion regarding the individual styles of statues but tend to address them as a whole, yet the routes of different styles vary. Moreover, research on the important transmission role that the Malay Peninsula played in the routes of Buddhism and Buddhist art exchange in the 5th and 6th centuries is still relatively limited. Therefore, this article intends to explore these issues further, based on previous studies.

2. Three Mainstream Standing Buddha Styles in Southeast Asia and Their Transmission Routes

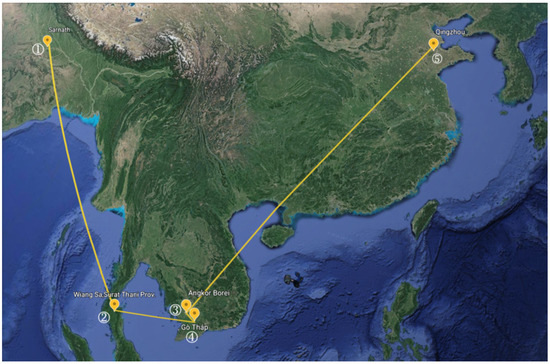

Carved-in-the-round standing Buddha statues of Qingzhou can be found in both a local style and a foreign style, and the distinguishing difference between the two is that the latter type wears a thin, tight-fitting robe. Based on the currently published materials, there are three main types of statue of the foreign style, which account for at least half of the total finds. These are as follows: type A—standing Buddha with a diaphanous robe draped over both shoulders; type B—standing Buddha with a densely pleated robe covering only the left shoulder; and type C—standing Buddha with a diaphanous robe covering only the left shoulder (Figure 1). Of these, the type A statue (Figure 1 (1)) is the most common and has the widest distribution. Up until now, none of the standing Buddha statues of the Qingzhou style have been found with inscriptions suitable for accurate dating. Nevertheless, typological studies reveal that type A statues belong to an earlier period than the other two and can be dated to as early as the middle of the 6th century (Meng 2021, pp. 106–9). According to previous research, the foreign style Qingzhou Buddha statues originated in India, but their appearance was likely to have come under the direct influence of the similar local statues in Southeast Asia (Meng 2021, pp. 181–219).

Figure 1.

The main types of Qingzhou-style carved-in-the-round standing Buddha statues. (1): Buddha with diaphanous robe draped over both shoulders (type A), mid-6th century, excavated from Zhucheng, Shandong Province, Zhucheng Museum (source: photograph by the author). (2): Buddha with densely pleated robe covering only the left shoulder (type B), mid-6th century, excavated from the Longxing Temple site, Qingzhou, Shandong Province (source: Fan 2016, p. 95). (3): Buddha with diaphanous robe covering only the left shoulder (type C), mid-6th century, excavated from the Longxing Temple site (source: The National Museum of Chinese History 1999, p. 110).

Regarding the research on the transmission route from mainland India to northern China, the transmission situation in Southeast Asia is an important but weak link. The reason for the weakness lies in the lack of overall knowledge of the various styles of Southeast Asian standing Buddha statues from the 5th to the 7th century. Therefore, this article first examines the mainstream standing Buddha styles and their distribution in Southeast Asia during this period in order to respond to the question of the transmission route in Southeast Asia as the middle ground for the spread of the Buddha statues to the east.

From the 5th to the 7th century, the three main types of standing Buddha statues in Southeast Asia are similar to the Qingzhou-style statues, namely standing Buddha statues with a diaphanous robe draped over both shoulders (type A), standing Buddha statues with a densely pleated robe covering only the left shoulder (type B) and standing Buddha statues with a diaphanous robe covering only the left shoulder (type C). These three are likely to be the direct sources of the counterparts of Qingzhou style, respectively.

On the type A statues of Qingzhou style, the robes are only pleated around the chest, the edges of the wrists and ankles and the arms are completely connected to the torso. This type was first seen in the Sarnath region in northern India, where it originated, and was introduced to the Shandong coastal region in north China via the northern Malay Peninsula, the lower Mekong River and the Mekong Delta region (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The schematic diagram of transmission route of standing Buddha statues with diaphanous robe draped over both shoulders (type A). ① Sarnath, Northeast India; ② Wiang Sa, Surat Thani, Thailand, North-Central Malay Peninsula; ③ Angkor Borei, Ta Keo, Cambodia, Lower Mekong; ④ Mekong Delta; ⑤ Longxing Temple Site, Qingzhou, Shandong Peninsula, China. Note: The lines in the picture are connected according to archaeological excavation or collected finds and indicate the approximate transmission route, not the exact one. The same goes for the maps below.

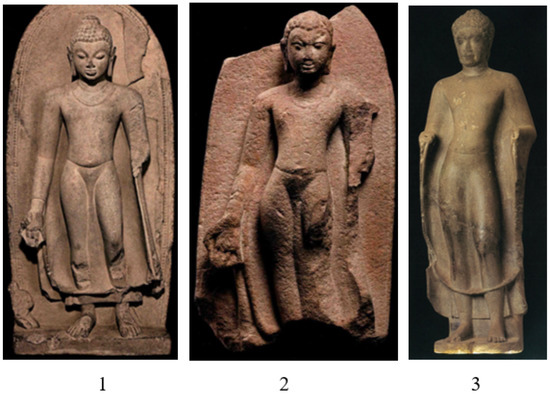

The Sarnath style was one of the most widely influential Buddha sculpture styles in the Gupta period and was very dominant in the 5th century (Figure 3 (1)). The style was introduced to Southeast Asia after it had spread to the northern part of the Malay Peninsula in southern Thailand (Figure 3 (2)) no later than the late 5th and early 6th centuries (Griswold 1966, pp. 62–65; Guy 2014, p. 38). The Wiang Sa standing Buddha may be the earliest standing Buddha statue with diaphanous robe draped over both shoulders (type A) in Southeast Asia. The transparent robe, twisted figure, spiral ushnisha and the quiet and elegant face all reveal a connection with the Sarnath style. Scholars have had various theories regarding its place of production. Whether it was imported (Wu 2010, p. 185; Guy 2014, pp. 38–39) or made locally (Griswold 1966, pp. 62–65; Jacq-Hergoualc’h 2002, p. 144), this statue indicates that the north-central Malay Peninsula was a source and transit point for the Qingzhou-style standing Buddha statues with diaphanous robe draped over both shoulders.

Figure 3.

Standing Buddha statues with diaphanous robe draped over both shoulders (type A) in India and Southeast Asia. (1): Buddha, ca. 475, Sarnath region, Uttar Pradesh, India (source: Guy 2014, p. 39, CAT. 10); (2): Buddha, late 5th century to the first half of the 6th century, Wiang Sa district, Surat Thani province, southern Thailand. (Source: Guy 2014, p. 38, CAT. 9); (3): Buddha, second half of the 6th century, Vat Romlok site, Angkor Borei, Ta Keo, Cambodia (source: Jessup and Zephir 1997, p. 147).

In the second half of the 6th century2, in the Mekong Delta, standing Buddha statues with diaphanous robes draped over both shoulders (type A) were fully developed. Standing Buddha statues were excavated from the site of the Romlok Temple in Angkor Borei (Figure 3 (3)), which are very similar to the statues found in Zhucheng, Shandong Province, but less rigid (Figure 1 (1)). Type A Buddha statues were also unearthed at Qingzhou (Qingzhou Museum 2014, p. 94), which appear to be directly influenced by their southeast Asian counterparts.

The second type of standing Buddha statue with a densely pleated robe covering only the left shoulder (type B) has the right arm separated from the body (Figure 4). Examples of this type were found in the Amaravati–Nagarjunakonda region of the Krishna Valley in India (Figure 4 (4)), as well as in Anuradhapura and Tissamaharama in Sri Lanka at a relatively early date. The features of the two are different: the urna is carved between the eyebrow of the Krishna Valley-style statue in India and the robe covering the left body is densely pleated with rather loose robe pleats on the right side of body, while there is no urna on the Sri Lanka-style statue of the 2nd to 3rd centuries and the pleats of robe are dense all over the body. The lack of or presence of the urna is the most distinguishing difference between the Krishna Valley style and the Sri Lanka style (Bopearachchi 2012, p. 57). Scholars believe that the indigenous characteristics of the Sri Lanka-style statues were formed based on the adoption of the features of similar statues in India, which led to a statue style that was different to the Amaravati–Nagarjunakonda statues (Bopearachchi 2012, pp. 49–68).

Figure 4.

Standing Buddha statues with densely pleated robes covering only the left shoulder (type B). (1): Bronze Buddha, the 6th century, Dong Duong, Quang Nam Province, Vietnam (source: Griswold 1966, figure 6a); (2): Bronze Buddha, the 6th to 7th century, Nakhon Ratchasima, Thailand (source: Guy 2014, p. 35, CAT. 5); (3): The image of disciples on the relic box, the 6th century, relic chamber of Khin Ba stupa, Sri Ksetra, Myanmar (source: Guy 2014, p. 81, CAT. 27); (4): Buddha, Amaravati, the 2nd to 3rd century (Source: China Cultural Relics Exchange Center 2007, p. 59, figure 8).

Thus, the Qingzhou style statues are derived from Krishna Valley-style statues in India, not Sri Lanka (Meng 2021, pp. 210–11). In contrast, the similar standing Buddha statues in Southeast Asia, which are seen as the transmission middle ground, have been found in both the Krishna Valley style and the Sri Lankan style. A 6th-century standing Buddha unearthed in Dong Duong, eastern Vietnam (Figure 4 (1)), has an urna between its eyebrows and a loosely pleated robe covering the right side of its body, which are the characteristics of the Amaravati–Nagarjunakonda statue style, whereas a 6th to 7th century standing Buddha found in Nakhon Ratchasima Thailand (Figure 4 (2)) displays distinctive features of the Sri Lanka-style statues: no urna and a relatively densely pleated robe over the whole body.

Therefore, it appears that in Southeast Asia, which is the middle ground for the eastward transmission of standing Buddha statues with densely pleated robes covering only the left shoulder (type B), two types of statues from different origins coexist, indicating that the diffusion route in Southeast Asia is more complicated than previously thought. As discussed above, there is at least one route from the Krishna River Valley in India to eastern Vietnam. However, there may also be a route from Sri Lanka to Nakhon Ratchasima through the southeastern hinterland of Thailand. Considering the geographical location of the two, the transmission could be by sea.

Another possible eastern route from the Krishna River Valley is through the Sri Ksetra region in Myanmar based on the following evidence: the robe of a statue of a disciple on the Sri Ksetra reliquary (Figure 4 (3)) is almost plain (similar to type A) except for the left lower hem, which is everted and carved with vertical pleats. Such a feature is distinct from the features of the more commonly seen statues with diaphanous robe but is often found on the type B Buddha statues. This suggests that the Buddhist statue style in Sri Ksetra was also influenced by the type B statues at some point and that the eastward transmission route (Figure 5) from India might have bypassed Myanmar and therefore could have been an overland route.

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of the transmission route of standing Buddha statues with densely pleated robe covering only the left shoulder (type B). ① Nagarjunakonda, Krishna River Valley, India; ② Amaravati, Krishna River Valley, India; ③ Anuradhapura, Sri Lanka; ④ Sandagiri Dagaba, Tissamaharama, Sri Lanka; ⑤ Sri Ksetre, Myanmar; ⑥ Nakhon Ratchasima, Thailand; ⑦ Dong Duong, Quang Nam Province, Vietnam; ⑧ Longxing Temple Site, Qingzhou, Shandong Peninsula, China.

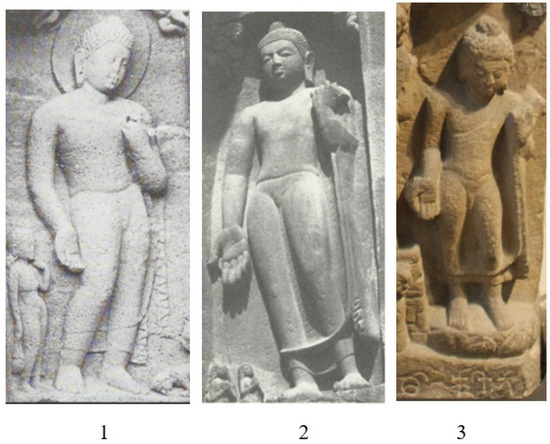

The third type is a standing Buddha with a diaphanous robe covering only the left shoulder (type C) (Figure 6). The right chest and shoulders are exposed, the right arm is separated from the body and the left arm is connected to the body. In the early statues, the left hand is raised and holding the corner of the robe, while the right hand is lowered in the gesture of varadamudrā. Except for the hem, there are almost no pleats on the robe. The ankle shows two layers of hem, and the upper layer is arc-shaped at the left ankle.

Figure 6.

Standing Buddhas with diaphanous robe covering only the left shoulder (type C) in India. (1): Buddha of the Façade to left of door, Cave 19. Ajanta, north-central Maharashtra state, India, late 5th century (source: Huntington 1985, figure 12.4); (2): Buddha of the Façade, Cave 19. Ajanta, north-central Maharashtra state, India, late 5th century (source: Yagi 2013, p. 147, figure 15); (3): Buddha of a Stele, Sarnath, Eastern Uttar Pradesh state, Calcutta Museum, India, 5th century (source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Scene_from_Buddha%27s_Life_-_Indian_Museum_-_ACCN_S.4/A25096 (last access: 22 November 2022)).

Currently, the earliest finds in this style are the standing Buddhas in the Ajanta Caves in India in the 5th century (Figure 6 (1) and (2)) and from the steles of Buddha’s life found in Sarnath (Figure 6 (3)). These statues have a high ushnisha (uṣṇīṣa), graceful facial features with slightly closed eyes looking down, wide shoulders and a broad chest. The left leg is bent, the right hip is lifted and the body is twisted and full of motion. The hem of the robe on the right upper side is at the level of the chest. These standing Buddha statues with diaphanous robes covering only the left shoulder (type C) are usually placed on both sides of the main statue as the retinue (脅侍), and the main statue wears a robe draped over both shoulders. It seems that type C standing Buddhas were the mainstream style of statues in India (at least in Sarnath and Ajanta), which is very different from the situation in Southeast Asia.

Around the 6th century AD, standing Buddhas with diaphanous robes covering only the left shoulder were one of the most common types of statue in Southeast Asia. A statue unearthed in Kedah, Malay Peninsula, dating to the early 6th century, displays the Indian three-bend posture with the left hand holding the corner of the robe, the right hand lowered in the gesture of varadamudrā and the short outer layer of robe-tails on the left leg is arc-shaped. Nevertheless, its ushnisha (uṣṇīṣa) is low with large and flat spiral curls, and the torso is relatively slim (Figure 7 (1)). Such features are not seen on similar Indian statues but have been found on Qingzhou-style statues, especially the low, flat, spiral curls which appear to have been directly influenced by the type C statues of Southeast Asia.

Figure 7.

Standing Buddhas with diaphanous robes covering only the left shoulder (type C) in the Malay Peninsula. (1): Buddha, copper alloy, excavated from site 16A, Bujang valley, Kedah, Malay Peninsula, early 6th century (source: Guy 2014, p. 75, CAT. 20); (2): Buddha, copper alloy, Malay Peninsula, Asian Civilization Museum, Singapore, 6th to 7th century (source: Guy 2014, p. 75, CAT. 22); (3): Buddha, sandstone, reportedly found in peninsular Thailand, National Museum, Bangkok, 6th to 7th century (source: Guy 2014, p. 8, figure 7).

No later than the first half of the 6th century, similar standing Buddha statues made of stone appeared in the lower Mekong and Mekong Delta regions. A type C statue was unearthed from the ruins of Vat Romlok, (Figure 8 (1)) which some scholars believe to date from the 6th or 7th century (Boisselier 1989, p. 31; Giteau 1965, p. 43; Wu 2010, p. 68). Its ushnisha is low and indistinguishable from its ground hair (地發), the spiral curls are flat and big and the left-side hem of the tail of the robe is arc-shaped. The lifted hip and bent knee posture is obvious, which is similar to the early 6th century statue unearthed in Kedah, Malay Peninsula. The later bronze Buddha statue from the Malay Peninsula also partially displays an ushnisha, which is low and indistinguishable from the ground hair, although the hem position of upper left robe is slightly lower (Figure 7 (2)). Moreover, in the latter statue, the torso is slimmer, the movement range of the bent knees and lifted hip is reduced and the posture is more rigid. There is also a change in the hand posture, namely the appearance of Abhayamudrā. These features are consistent with the Qingzhou-style Buddha with a diaphanous robe covering only the left shoulder (type C) (see Figure 1 (3)), which may be the common evolutionary trend of this type of statue after the middle of the 6th century. Such statues made of stone are also found at the Óc Eo site in the Mekong Delta (Figure 8 (2)). Standing Buddhas of this style in the 7th and 8th centuries are also seen in the northwestern region of present-day Cambodia (Jessup and Zephir 1997, p. 150), which may have spread from the lower reaches of the Mekong or the Mekong Delta region.

Figure 8.

Standing Buddhas with diaphanous robe covering only the left shoulder (Type C) in the Mekong Delta. (1): Buddha, stone, excavated at the site of Vat Romlok, Angkor Borei, Cambodia, 6th century (source: Giteau 1965, p. 43, Pl. 8); (2): Buddha, stone, excavated at Nen Chua, Kien Giang Province, Vietnam, 7th century (source: Döng 2022, p. 338, figure 214); (3): Buddha, wood, excavated at Tháp Mười, Southern Vietnam, late 5th century (source: Malleret 1963, Pl. XXI).

The transmission routes of the three South Asian Buddha statue styles to the east is quite complicated. Its complexity is reflected in the following points: First, transmission may have occurred many times over a long period of time. Second, in addition to the main passages through the north-central Malay Peninsula and the Mekong Delta, there are branch lines; moreover, there is a mutual influence between styles. Finally, the transmission areas of the two types of standing Buddhas with diaphanous robes overlap, which will be discussed below.

A standing Buddha statue with a diaphanous robe covering only the left shoulder was unearthed in Tháp Mười in the Mekong Delta and dated to the end of the 5th century (Figure 8 (3)) (Malleret 1963, pp. 156–57, PL. XXI). Despite the fact that Mekong Delta is located farther east, this find is dated earlier than the statues of the same style excavated in the Malay Peninsula. Its high ushnisha also shows the Southeast Asian ushnisha style seen on the standing statues with a robe covering only the left shoulder, prior to the influence of Amaravati and other styles. The bodies of 5th-century Indian standing Buddha statues with diaphanous robes covering only the left shoulder are bulky and not so slender (Figure 6). Some Southeast Asian statues of the 6th and 7th centuries show similar robust features (see Figure 4 (1) and Figure 7 (1)), while others are slim and slender (see Figure 3 (3) and Figure 7 (2)). The wooden Tháp Mười Buddha, as an early example of the latter, could shed light on the origin of this type of statue. Other examples are the 6th century standing Buddhas with diaphanous robes covering only the left shoulder, unearthed in the Malay Peninsula and the Mekong Delta. Regarding the two layers of robe-tails on the left calf, the shorter outer one is generally arc-shaped. This is very different from the Sarnath statues, on which this part is a right angle (Guy 2014, p. 75), but bears significantly more resemblance to the Ajanta cave statues, despite their more distant location (See Figure 6). As discussed above, the transmission of Buddhist art was not a linear process from west to east, but occurred in multiple different instances. During the repeated transmission from the 5th to the 7th century, the three types of standing Buddha statues were gradually locally adapted in Southeast Asia and at the same time continued to spread farther east, eventually reaching China.

A standing statue which is reported to have come from the Malay Peninsula region in southern Thailand wears a diaphanous Buddhist robe covering the left shoulder and lifts a corner of the robe with the left hand (Figure 7 (3)). It is generally considered to have its stylistic roots in the above-mentioned Ajanta and Sarnath standing Buddhas with diaphanous robes covering the left shoulder, but some scholars believe that it is likely to be based on the statues of Andhra Pradesh in southeastern India (Guy 2014, p. 7), namely the Amaravati–Nagarjunakonda region of the Krishna Valley, where, as discussed above, type B statues are common. The author believes that, as this statue from southern Thailand lifts its robe with its left hand, causing a vertical pleat, it indeed draws reference from the Nagarjunakonda-style statues. The fusion of these stylistic elements is reminiscent of the robe of monks on the Sri Ksetra reliquary (See Figure 4 (3)). It appears that in the transmission route from India to Southeast Asia of the standing Buddha statues with robes covering only the left shoulder (Figure 9), there is a branch line through Myanmar, and in the process of eastward transmission, the two styles of densely-pleated and diaphanous robes interacted and blended with each other.

Figure 9.

The schematic diagram of the transmission route of standing Buddha statues with diaphanous robe covering only the left shoulder (type C). ① Ajanta Caves, India; ② Sarnath, India; ③ Sri Ksetre, Myanmar; ④ Bujang Valley, Kedah, Malay Peninsula; ⑤ Vat Romlok Site, Angkor Borei, Cambodia; ⑥ Nen Chua, Kien Giang Province, Vietnam; ⑦ Longxing Temple Site, Qingzhou, Shandong Peninsula, China.

The interaction between these two styles is also reflected on the ushnisha. The Indian Buddha statues of the 5th century with diaphanous robes covering only the left shoulder have a high ushnisha which is distinguishable from the ground hair (Figure 6 (2)). On the other hand, the similar gilt bronze and stone statues in Southeast Asia from around the 6th century generally have a low ushnisha, and there is no clear boundary between the ground hair and the ushnisha. In fact, this type of low ushnisha appeared on early Indian Amaravati-style statues (See Figure 4 (4)) and Sri Lankan Anuradhapura-style statues (Jessup and Zephir 1997, p. 146). As time passed, the low ushnisha was further developed and the boundary between the ground hair and the ushnisha almost disappeared, which became a significant feature of Southeast Asian statues in the 6th century. The diaphanous robes which cling to the outlines of the body are derived from the standing Buddha statues in Sarnath, which wear diaphanous robes draped over both shoulders. Therefore, it seems that the development of the Southeast Asian type C statues is related to the transmission of the type A and B statues in the same region.

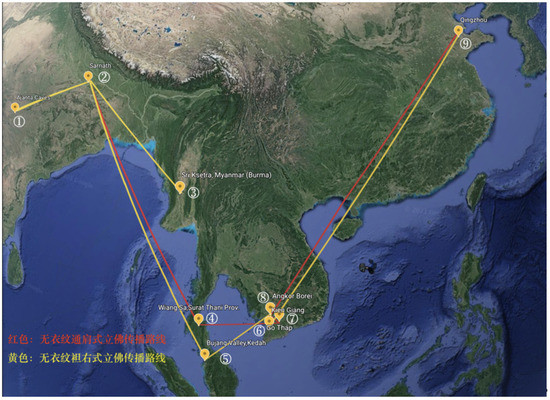

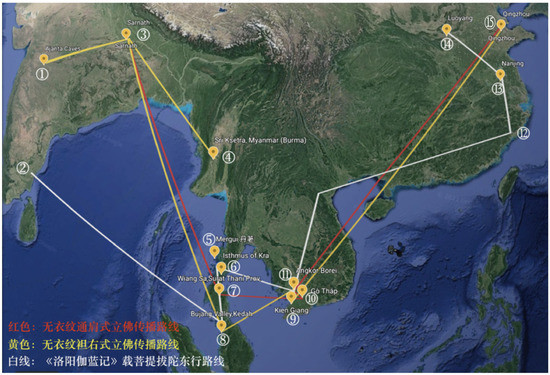

In particular, the eastward transmission route of type C statues (Figure 9) has a considerable degree of overlap with the type A statues in Southeast Asia (Figure 10): starting from the Indian subcontinent, the route passes through the northern and central-northern regions of the Malay Peninsula in Southeast Asia to the lower reaches of the Mekong River and the Mekong Delta region and then to northern China. The areas where the routes overlap are mainly the northern Malay Peninsula and the Mekong Delta, which may have been common transit areas during the eastward transmission of these two types of statues.

Figure 10.

The schematic diagram of transmission routes of standing Buddha statues with diaphanous robes (type A and type C). ① Ajanta Caves, India; ② Sarnath, India; ③ Sri Ksetre, Myanmar; ④ Wiang Sa, Surat Thani Prov., Malay Peninsula; ⑤ Bujang valley, Kedah, Malay Peninsula; ⑥ Nen Chua, Kien Giang Prov., Southern Vietnam; ⑦ Mekong Delta; ⑧ Vat Romlok Site, Angkor Borei, Cambodia; ⑨ Longxing Temple Site, Qingzhou, Shandong Peninsula, China; Red lines: transmission route of type A statues; yellow lines: transmission routes of type C statues.

To sum up, based on the understanding of the three mainstream styles of standing Buddha statues in Southeast Asia and by examining their distribution, their eastward transmission routes can be mapped out, resulting in the main transit areas as the central-north Malay Peninsula and Mekong Delta. So, can this route and its transit points be verified in the historical records? Next, we will explore the records of the cultural exchange of Buddhism from India to the Northern Dynasties via Southeast Asia in ancient Chinese texts.

3. The Buddhist Monks Travelling Routes from India, through Southeast Asia, to North China in Historical Records

As discussed above, the main transit areas of the eastward transmission routes of the two types of standing Buddha statues with diaphanous robes in Southeast Asia around the 5th to 7th century were the north-central Malay Peninsula and the Mekong Delta. No later than the mid-6th century, these types of statues had reached China and had a direct impact on the carved-in-the-round standing Buddha statues of Qingzhou. However, there are few records of direct Buddhist exchange between India, Southeast Asia and North China during the period of the late Northern Dynasties (the first half of the 6th century). Fortunately, a record of monks from Ko-ying (歌營) who came to Luoyang through Southeast Asia can provide us with some clues. In volume four of Lo-yang ch’ieh-lan chi (A Record of Buddhist Monasteries in Lo-yang, 洛陽伽藍記) (547), it is stated that:

Yongming (永明) Temple, built by the Emperor Xuanwu (宣武) of Northern Wei, is in the east of Dajue (大覺) Temple. At that time, Buddhism flourished in Capital Luoyang (洛陽), which attracted monks from other countries, so the Emperor Xuanwu built this temple as the resting place for the monks. To the south of China, there is Ko-ying (歌營), which is far away from Luoyang and never had interaction with China before; during the Han Dynasty and the Wei Dynasty, there were no visitors from Ko-ying. Until now, a monk named Putibotuo (菩提拔陀, Bodhibhadra) from Ko-ying has come to China, himself says that after journeying northwards from Ko-ying for one month I reached Kou-chih (勾稚). After travelling northwards for eleven days I reached the Dian-sun (典孫). From Dian-sun I voyaged northwards for thirty days, when I reached Fu-nan (扶南). Fu-nan has a vast territory of five thousand miles and is the most powerful among kingdoms in the south of China…… After travelling northwards from Fu-nan for a month, I reached Lin-yi (林邑). From Lin-yi, I arrived at the Southern Liang. Bodhibhadra reached Yangzhou (揚州) and stayed thhere for more than a year, and then he travelled together with Farong (法融, a monk from Yangzhou) to Luoyang.(Yang 2018, pp. 248–49)

Bodhibhadra was a native of Ko-ying (歌營), passing through Kou-chih (勾稚), Dian-sun (典孫), Fu-nan (扶南) and Lin-yi (林邑) to southern Liang and then went north from Yangzhou (揚州) to Luoyang (洛陽). There are four theories regarding the location of Ko-ying (also known as Jiaying 加營): South India (Fujita 2015b, pp. 557–59; Su 1951, pp. 18–24), the southern part of the Malay Peninsula (Pelliot 1995, pp. 155–56; Shi 2004, p. 41), the Nicobar islands (Cen 2004, pp. 124–25) and Sumatra and Java islands (Wolters 1967, pp. 55–58; 1979, pp. 1–32). This author believes South India to be the most plausible of these locations, based on the following arguments. The time when Buddhism was introduced to the present-day Indonesian Sumatra and Java islands was the late 5th century (Wang 2022, p. 62) and it was introduced to Peninsular Malaysia no earlier than the 5th–6th century (Yao 2014, p. 470; Wang 2022, p. 64). It was not until the middle of the 5th century that Buddhism flourished in Southeast Asia (Yao 2014, p. 471), thus it is not very logical to suggest that Bodhibhadra, a respected and famous monk, came from either the Indonesian Sumatra and Java islands or Malaysia. In addition, Bodhibhadra was familiar with the Huohuan (火浣) fabric, which is a local product of the Sitiao (斯調) kingdom, as well as its raw materials; thus, Sitiao was most likely located in the vicinity of Ko-ying. Sidiao can therefore be located in present-day Sri Lanka (Fujita 2015b, pp. 541–78), near South India. Moreover, there was no interaction between China and Ko-ying until the 5th century, and southern India was more difficult to reach than the three islands of Sumatra, Java and Malaysia. Therefore, South India is the most plausible theory regarding the location of Ko-ying. Dian-sun (典孫), also known as Tun-sun (頓遜), according to G. Schlegel, is Tenasserim, whose capital (now called Mergui) is ten miles from the sea, which is consistent with historical records and widely accepted (Schlegel 1899, p. 38; Pelliot 1903, p. 263; Cen 2004, pp. 126–28; Rao 1970, pp. 38–40). Its central region ranges from Mergui in Myanmar to the Isthmus of Kra (Chen 1992, pp. 58, 102–3), but it is still in the northern part and does not reach the southern end of the Isthmus (Jacq-Hergoualc’h 2002, p. 103). Kou-chih, also known as Juli (拘利), is located on the west coast of the Malay Peninsula (Fujita 2015a, pp. 88–90; Hsu 1961, pp. 82–84)—more precisely, the Isthmus or Kedah (Cen 2004, pp. 121–25; Han 1991, p. 236). The central area of ancient Fu-nan is relatively clear and is generally considered to be the lower reaches of the Mekong River and the Mekong Delta (Pelliot 1903, pp. 285–86; Coedes 2018, p. 69; Chen 1992, p. 532). Lin-yi is roughly in the northeastern part of Vietnam (Chen 1992, pp. 355–57; Fan 2016, pp. 254–55, Note 7). During the Southern Liang, the Yangzhou refers to quite a large area, mainly the coastal region of Fujian and Zhejiang Province (Yang 2018, pp. 254–55, Note.9).

The above records describe Bodhibhadra’s eastbound route in detail: starting in the Indian subcontinent and then passing through three important transit areas in Southeast Asia. The first is Guozhi, which is on the west coast of the north-central part of the Malay Peninsula (Kedah or slightly north of the Isthmus of Kra); the second is Tun-sun, the northern part of the Malay Peninsula (from Mergui to the north of the Isthmus of Kra); and the third is Fu-nan, which mainly refers to the lower reaches of the Mekong River and the Mekong Delta region. After this, the route passed north to northern Vietnam, then through the coast of Fujian and Zhejiang and finally entered the region of the Northern Dynasties. This route was roughly the same as the transmission paths of the type A and C standing Buddha statues from Southeast Asia to the Northern Dynasties (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

The schematic diagram of transmission routes of standing Buddha statues with diaphanous robes (type A and type C) and the route of Bodhibhadra. ① Ajanta Caves, India; ② Ko-ying, South India; ③ Sarnath, India; ④ Sri Ksetre, Myanmar; ⑤ The northernmost region of Tun-sun, Mergui, Myanmar; ⑥ The southernmost region of Tun-sun, Isthmus of Kra, Malay Peninsula; ⑦ Wiang Sa, Surat Thani Prov, Malay Peninsula; ⑧ Bujang Valley, Kedah, Malay Peninsula; ⑨ Nen Chua, Kien Giang Province, Vietnam; ⑩ Mekong Delta; ⑪ Vat Romlok Site, Angkor Borei, Cambodia; ⑫ Coastal region in Southeast China; ⑬ Nanjing, China (capital of Southern Liang); ⑭ Luoyang, China (capital of Northern Wei); ⑮ Longxing Temple Site, Qingzhou, Shandong Peninsula, China; Red lines: the transmission route of Type A; yellow lines: the transmission route of Type C; white lines: the route of Pu-Ti-Ba-Tuo.

The time when Bodhibhadra arrived in Luoyang was no earlier than the reign of Emperor Xuanwu (宣武帝) (500–515), when Yongming Temple was built in Luoyang, and was no later than the third year of Yongxi (永熙) (534), when the capital moved to Ye city in the winter, so Bodhibhadra’s journey would have taken place between 500 and 534, which is not too distant from the mid-6th century, the period between the Eastern Wei and Northern Qi Dynasties. Therefore, the styles of Southeast Asian standing Buddha statues may still have been partly introduced to the Northern Dynasties along this route, which may have directly led to the popularity of several foreign styles in Qingzhou statues. The above-mentioned transmission route of Buddhist art can be verified using historical records.

4. Occasionality and Inevitability—Transit and Destination of the Transmission Routes

As discussed above, the north-central part of the Malay Peninsula, the lower reaches of the Mekong River and the Mekong Delta region are important transit points for the transmission of foreign statue styles to Qingzhou. In previous studies, scholars have focused on the latter, that is, the transfer role of Fu-nan, while the exchanges of Buddhism and Buddhist art between the north-central Malay Peninsula and the Northern Dynasties has been less or unsubstantially studied. The excavation sites of the two types of standing Buddhas with diaphanous robes in the Malay Peninsula (Figure 10) are concentrated in the area between Kedah and the Isthmus of Kra, which roughly coincides with the location of Kou-chih and Tun-sun, the ancient kingdoms Bodhibhadra passed through on his journey to China (Figure 11). Therefore, in the 6th century, the north-central Malay Peninsula was an important transit point on the eastward sea-borne route that spread Buddhist art to China. Judging from the finds so far discovered, the style of wearing diaphanous robes draped over both shoulders that originated from India was first introduced to Southeast Asia though the north-central Malay Peninsula (Figure 3).

The transit role that the north-central Malay Peninsula played in the exchange of Buddhism and Buddhist art is related to the fact that this region was the hub of east–west trade at that time. Professor Chen Xujing discussed in detail the important geographical locations and operation patterns of the northern part of the Malay Peninsula in early Southeast Asian trade. He pointed out that the ships from the west first sailed to the west coast, and then travelers or traders would have taken the land route to the east coast, after which they sailed again from the east bank to the Indochina Peninsula and China. The land route, according to Professor Chen, extends from the Isthmus of Kra to Mergui and the direction is southeast to northwest (Chen 1992, p. 103). However, the Buddha statues are mainly found in the southern part of this area, and it can be inferred from the Bodhibhadra’s journey that the land route crossing the Indochina Peninsula would have run from the southwest to the northeast, and therefore may not be the same route discussed by Professor Chen. French scholar Michel Jacq-Hergoualc’h suggested four detailed trade routes across the Malay Peninsula (Jacq-Hergoualc’h 2002, pp. 44–50), two of which are located in the north-central Malay Peninsula and clearly run from the southwest to the northeast: the Ranong-Kraburi to Chumphon route and Kedah to Pattani route. In the area between these two routes, standing Buddha statues with diaphanous robes draped over both shoulders (Figure 3 (2)) and statues with diaphanous robes covering only the left shoulder (Figure 7 (1)) from the early 6th century have been excavated. Therefore, the transmission route of Indian Buddhist art to the Malay Peninsula may have passed through one, or specific sections, of the above two routes.

The transmission route of Buddhist art reveals that in the north-central Malay Peninsula, the sea-to-land transportation mode may have lasted later than previously realized. It was previously believed that, from the 4th to the 5th century onwards, on the route from India to China, the statues of the Isthmus of Kra in the northern part of the Malay Peninsula were diminished and the trading route was changed to bypass the Strait of Malacca to reach the western edge of the Java Sea and sail along the port of Sumatra to China (Hall 1985, p. 78; Chen 1992, pp. 104–6). However, the transmission of Southeast Asian Buddhist art to the Northern Dynasties indicates that by the middle of the 6th century at the latest, the land routes on the Malay Peninsula may have still played an important part in the sea-borne exchange from India to China.

It is necessary to explain that before the middle of the 6th century, sea-to-land transportation and the status of the Malay peninsula as a traffic artery were caused by the limitations of shipbuilding and marine technology. Such transportation modes and the resulting key positions of this region are generally believed to have been roughly formed in the Han Dynasty when the ships were small and simple in structure and seamanship was not advanced enough to sail across the ocean, only allowing voyages along or close to the shore (Chen 1992, pp. 98–99, 102–4). The journey from Fu-nan to Tianzhu (天竺) during the Three Kingdoms (Wu State) period still passed this way (Yao 2020, p. 883). The north-central Malay Peninsula is relatively narrow, which leads to a relatively short transportation distance. Therefore, it was the safest and most efficient route for ships from South Asia to go ashore on the west coast of the Malay Peninsula, travel by land to the east coast and then enter the sea at the Gulf of Siam, and vice versa. The north-central Malay Peninsula thus became a key point for east–west traffic, and thus, the eastward coastal transmission route of Buddhist art in the 6th century may have passed through this region.

Standing Buddha statues of the Qingzhou style with thin and tight-fitting robes that cling to the outlines of the body appeared around the time of the Eastern Wei Dynasty (534–550) and the Northern Qi Dynasty (550–577), which are directly influenced by Southeast Asian statues and display a style not found in statues of the Southern Dynasties (Yao 2005, pp. 320–37). It would appear that when reaching China, Southeast Asian statues bypassed the Southern Dynasties. However, whether from the historical records or the Buddha statues found so far, Southeast Asian Buddhism and Buddhist art, represented by Fu-nan, can be seen to have had frequent exchange with the Southern Liang Dynasty. In the early and middle periods of the Southern Liang Dynasty, the Buddhism and Buddhist art exchanges between Fu-nan and the Southern Dynasties were the most prosperous, during which Buddhist art of the Southern Dynasties even transmitted back to the lower reaches of the Mekong River and the Mekong Delta area (Yao 2016, pp. 269–97). During Bodhibhadra’s journey to the capital of the Northern Wei Dynasty, he also crossed regions governed by the Southern Liang Dynasty. Moreover, after the rule of the Southern Liang Dynasty ended, the tribute from Southeast Asian kingdoms and exchange of monks between Southeast Asia and the Southern Dynasties continued until the Southern Chen Dynasty (557–589), as recorded in historical documents (Daoxuan 2014, p. 22; Fei 1934, p. 88b; Jian 2001, pp. 67–68). Therefore, it was quite unusual that in the middle of the 6th century, the style in which these types of Southeast Asian Buddha statues were carved were transmitted directly to Qingzhou, if the ships from Southeast Asia arrived in China through the ports in Shandong rather than the ones in the South. The reasons for such a change will be discussed below.

The author believes that this is related to the three events that occurred during the Southern Liang Dynasty: the siege of Jiankang (建康, the capital of the Southern Liang, now Nanjing) by Houjing (侯景) in the middle of the 6th century (548–549); the Great Famine in the south Yangtze River region (江南) (550) and the attack and subsequent looting of the Jingzhou Army (荊州軍) (552) (Wang 2003, pp. 413–26; Li 2008a, pp. 1538, 2006, 2009, 2014; Sima 2011, pp. 5018, 5032, 5045; Yao 2020, p. 628). These three successive disasters almost caused the overthrow of the Liang Dynasty, dealt a huge blow to the capital city Jiankang and its economy, destroyed the environment needed for Buddhism and Buddhist art exchange and greatly weakened Jiankang’s role as an important port city in the maritime trade with Southeast Asia. During the twenty years from 542 to 562, there is only one record of Southeast Asian kingdoms sending envoys to the Southern Dynasties. This is in great contrast to the situation during the early reign of Emperor Wudi (502–549), in which there was frequent tribute and envoys sent from Southeast Asia, as well as the exchange of Buddhism and its art. When the Southern Liang Dynasty was at its weakest, the powerful period of Eastern Wei Dynasty began (534–550) (Sima 2011, p. 5033). Moreover, the Gao family, who were actually in power during the Eastern Wei and the Northern Qi Dynasties (550–577), attached great importance to Buddhism, and the establishment of the Northern Qi Dynasty was also closely related to Buddhism (Sun 2019, pp. 33–38; Li 2014, p. 359, Note 1; Daoxuan 2014, p. 261). Thus, around the middle of the 6th century, ships from Southeast Asia probably bypassed Jiankang and sailed northward to Shandong, bringing with them three types of locally adapted statues that originated from India, which directly led to the emergence of new statue styles in Zhucheng, Linqu and Qingzhou.

However, the carved-in-the-round standing Buddha statues of the Qingzhou style, which were deeply influenced by foreign styles, were short lived in the history of Buddhist art. As for the reasons, on the one hand, Fu-nan, the Southeast Asian country that had the closest interaction with Chinese Buddhist art, gradually declined in the second half of the 6th century (Chen 1992, pp. 106, 694). During the Chen Dynasty (557–589), the import of Buddhism and Buddhist art from Fu-nan were not interrupted but was far less frequent than before (Yao 2016, p. 281), and by the time of the Chen Dynasty, there had been a significant decrease in the number of envoys from Southeast Asian kingdoms (Yao 1972, p. 115; Jian 2001, pp. 67–68), which naturally reduced the influence of Southeast Asian Buddhist art in China. On the other hand, and more importantly, in the middle and late period of the Northern Qi Dynasty (about 560–577), Southeast Asian ships no longer went north, which interrupted the import of the foreign standing Buddha statues. During this time, the Southeast Asian ships only sailed to the Southern Dynasties and no longer went north, which can be corroborated by a record in the Beiqi shu (The Book of Northern Qi 北齊書) (636). It states that Wei Shou (魏收), a minister who served in the Qi government, was convicted for privately seeking the “Kunlun” rare treasure. In the second year of Heqing 河清 (563), Wei Shou asked one of his retainers to travel together with Feng Xiaoyan (封孝琰), the Northern Qi ambassador, to the territories of the Southern Chen Dynasty, where the “Kunlun” ships (昆侖舶) carrying exotic cargo arrived, and the retainer purchased dozens of priceless objects on behalf of Wei Shou, resulting in Wei being sentenced to exile: however, he paid his way out of punishment (Li 1972, p. 492; 2008b, p. 2035). Kunlun (昆侖) is generally considered to refer to the south of Lin-yi, the former Fu-nan area (Zhang 1975, pp. 5270–71; Cai 2018, pp. 74–75). If the Kunlun ships still went north to the Qi Dynasty, Wei Shou would not need to risk exile in order to obtain these rare goods. Therefore, a more reasonable explanation is that after the second half of the 6th century, Southeast Asian ships seldom visited the region of the Qi Dynasty. As a result, Southeast Asian Buddhist art no longer had a direct impact on the creation of Buddha statues of Qingzhou and its surrounding areas. The interruption of its source led to the short life of the carved-in-the-round standing Buddha statues of the Qingzhou style.

5. Conclusions

This article mainly discusses the transmission route of the foreign styles seen in Buddha statues of Qingzhou carved in-the-round in the 6th century. Although the origin of the three foreign styles can be traced to the Indian subcontinent, the Qingzhou Buddha images seem to incorporate local modifications found in the Southeast Asian counterparts. By examining the three most common types of standing Buddhas in Southeast Asia and their dates and distribution, as well as the transit area of the eastward transmission route, it is revealed that from the 5th to the 7th century, there was a relatively high degree of overlap of the transmission routes of the two types of statues with diaphanous robes, which is also quite consistent with the Southeast Asian section of Bodhibhadra’s route to Luoyang from the east in the early 6th century. Combined with the study of trade routes in Southeast Asia, it can be inferred that during this period, the north-central Malay Peninsula held a key position in the eastward transmission route of Buddhist art via the sea. The reasons why Southeast Asia ships abandoned Jiankang and went north to Qingzhou appear to be the three catastrophes at the end of the Southern Liang Dynasty. The short life of the foreign-style standing Buddha statues of Qingzhou may be due to the fact that the ships from Southeast Asia were no longer visiting the north in the later period, consequently resulting in the interruption of the import and the direct influence of foreign Buddhist art.

It should be noted that the transmission route based on excavated materials and historical documents may only be one of the main paths of maritime Buddhist exchange between India and China at that time, since the actual transmission of Buddhist art is more complicated. The variety of types of Qingzhou-style standing Buddha statues indicates that during one or more of the several direct imports of Southeast Asian statues, multiple styles were introduced simultaneously. As discussed above, several types of standing Buddha statues originating from India underwent local adaptation and fusion in Southeast Asia, and their transmission might have occurred along various routes, in segmented paths and over multiple instances.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M.; methodology, S.M.; software, P.L.; validation, S.M. and P.L.; formal analysis, S.M.; investigation, S.M. and P.L.; resources, S.M.; data curation, S.M. and P.L.; writing—original draft preparation, S.M.; writing—review and editing, P.L.; visualization, S.M. and P.L.; supervision, S.M.; project administration, S.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable for this study not involving humans or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable for studies not involving humans.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable. No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Fu-Nan kingdom existed from the 1st to mid-7th century. In the second half of the sixth century, Fu-Nan was defeated by Chenla (6th century to early-15th century) (Chen 1992, pp. 690–715) and lost control of part of its territory. Nevertheless, the rule of Fu-Nan did not end, as Chinese historical records reveal that during the period of Wude 武德 (618–626) and Zhenguan 貞觀 (627–649), Fu-Nan still sent envoys and tributes to the Tang Dynasty (Du 1988, p. 5094; Ouyang 1975, p. 6301). Therefore, Fu-Nan lasted until the mid-7th century (Yao 2016, p. 278, note. 32). However, this defeat forced Fu-Nan to move its capital from Vyadhapura to Naravaranagara, which, according to Coedes, is the present-day site of Angkor Borei (Coedes 2018, p. 118). |

| 2 | Some scholars believe the date of the standing Buddha statue found at the Vat Romlok site (Angkor Borei, Cambodia) to be 7th century (Jessup and Zephir 1997, pp. 146–47), while others argue that it is 6th century (Kang 2013, p. 24). The characteristics of the Vat Romlok statue are the graceful hip-swayed stance (a gentle version of the Indian Tribhaṅga); the left knee slightly bent; the posture of the arms varied, as suggested by the different forward angles of the two forearms; and the not-very-thick lips. The body of the Vat Romlok Buddha is unlike the Wiang Sa Buddha, which is dated to between the late 5th century to the first half of 6th century and is full of motion, and its facial features and posture also display significant differences to a 7th century standing Buddha that was also found in Cambodia. The Buddha of Tuol Preah Theat has seventh-century inscription on its back (Jessup and Zephir 1997, pp. 149–50). It has locked knees and the rigid stance is quite obvious, and it has thicker lips. Such features originate from the Dvaravati Kingdom in nearby Thailand. The earliest Dvaravati Buddhas date to about the 6th century, but production began primarily in the 7th century (Brown 2014, p. 190). The 7th or perhaps the 8th century is a time when Dvaravati art had already undergone massive stylistic influence (Griswold 1966, p. 64). Based on the above argument, it can be inferred that the Vat Romlok standing Buddha dates from the second half of the 6th century. |

References

- Boisselier, Jean. 1989. Trends in Khmer Art. New York: Cornell Southeast Asia Program Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Bopearachchi, Osmund. 2012. Andhra-Tamilnadu and Sri Lanka: Early Buddhist Sculptures of Sri Lanka. New Dimensions of Tamil Epigraphy, Cre-A 2012: 49–68. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Robert L. 2014. Dvāravati Sculpture. In Lost kingdoms: Hindu-Buddhist sculpture of early Southeast Asia. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, pp. 189–91. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Hongsheng 蔡鴻生. 2018. Guangzhou Haishi Lu 廣州海事錄. Beijing: Shangwu Yinshuguan. [Google Scholar]

- Cen, Zhongmian 岑仲勉. 2004. Nanhai Kunlunyu Kunlunshan Zhi Zuichu Yiming ji Fujin Zhuguo 南海昆侖域昆侖山之最初譯名及附近諸國. In Zhongwai Shidi Kaozheng· Shang Ce 中外史地考證·上冊. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju, pp. 115–50. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Xujing 陳序經. 1992. Chen Xujing Dongnanya Gushi Yanjiu Heji · Shang Volume 陳序經東南亞古史研究合集·上卷. Taibei: The Shangwu Yinshuguan. [Google Scholar]

- China Cultural Relics Exchange Center 中國文物交流中心. 2007. Gudai Yindu Kuibao (Treasures of Ancient India) 古代印度瑰寶. Beijing: Beijing Meishu Sheying Chubansh. [Google Scholar]

- Coedes, George 喬治·賽代斯. 2018. Dongnanya de Yinduhua Guojia 東南亞的印度化國家. Beijing: The Shangwu Yinshuguan. [Google Scholar]

- Daoxuan 道宣 (596–667). 2014. Xu Gaozeng Zhuan (volume one) 續高僧傳(卷一). Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju. [Google Scholar]

- Döng, Chú biên. 2022. Văn Hóa Óc Eo—Những phát hiện mới khảo cổ học tại di tích Óc Eo—Ba Thê và Nền Chùa 2017–2020. Hà Nôi: Nhà Xuất bản Khoa học xã hội. [Google Scholar]

- Du, You 杜佑 (735–812). 1988. Tong Dian通典. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Zaizhong 杜在忠. 1994. Shandong Zhucheng Fojiao Shizaoxiang 山東諸城佛教石造像. Kaogu Xuebao 考古學報 2: 231–62. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Di’an 範迪安, ed. 2016. Posui yu Juhe: Qingzhou Longxingsi Fojiao Zaoxiang 破碎與聚合: 青州龍興寺佛教造像. Shijiazhuang: Hebei Meishu Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Fei, Zhangfang 費長房 (The Sui Dynasty (581–619)). Lidai Sanbao Ji (volume nine) 歷代三寶記 (卷九). In Taishō shinshū daizōkyō 大正新脩大藏經. Chinese Buddhist Electronic Text Association (CBETA) Edition, Vol. 49. No.2034. Available online: https://cbetaonline.dila.edu.tw/zh/T49n2034_p0088b28?q=善吉&l=0088b28&near_word=&kwic_around=30 (accessed on 3 January 2023).

- Feng, Chengjun 馮承鈞. 2017. Zhongguo Nanyang Jiaotong Shi 中國南洋交通史. Beijing: The Shangwu Yinshuguan. [Google Scholar]

- Fujita, Toyohachi 藤田豐八. 2015a. Qianhan Shidai Xinan Haishang Jiaotong zhi Jilu 前漢時代西南海上交通之記錄. In Zhongguo Nanhai Gudai Jiaotong Congkao· Shangce 中國南海古代交通叢考·上冊. Taiyuan: Shanxi Renming Chubanshe, pp. 83–117. [Google Scholar]

- Fujita, Toyohachi 藤田豐八. 2015b. Yetiao Sitiao ji Sihe Kao 葉調斯調及私訶條考. In Zhongguo Nanhai Gudai Jiaotong Congkao· Xiace 中國南海古代交通叢考·下冊. Taiyuan: Shanxi Renming Chubanshe, pp. 541–78. [Google Scholar]

- Giteau, Madeleine. 1965. Khmer Sculpture and the Angkor Civilization. London: Thames and Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Griswold, Alexander B. 1966. Imported Images and the Nature of Copying in the Art of Siam. Artibus Asiae. Supplementum 23: 37–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guy, John. 2014. Lost Kingdoms: Hindu-Buddhist Sculpture of Early Southeast Asia. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, Kenneth. 1985. Maritime Trade and State Development in Early Southeast Asia. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Zhenhua 韓振華. 1991. Weijing Nanbeichao Shiqi Haishang Sizhou Zhi Lu de Hangxian Yanjiu—Jianlun Hengyue Tainan Malai Bandao de Luxian 魏晉南北朝時期海上絲綢之路的航線研究—兼論橫越泰南、馬來半島的路線. In China and the Maritime Silk Route: UNESCO Quanzhou International Seminar on China and the Maritime Routes of the Silk Roads 中國與海上絲綢之路聯合國教科文組織海上絲綢之路綜合考察泉州國際學術討論會論文集. Edited by Quanzhou International Seminar on China and the Maritime Routes of the Silk Roads Organization Committee 聯合國教科文組織海上絲綢之路綜合考察泉州 國際學術討論會組織委員會. Fuzhou: Fujian Renmin Chubanshe, pp. 219–68. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, Angela F. 2008. Pluralism of Styles in Sixth Century China: A Reaffirmation of Indian Models. Ars Orientalis 35: 67–94. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, Yun Tsiao 許雲樵. 1961. Malaiya Shi· Shang Ce 馬來亞史·上冊. Singapore: Youth Book Co. [Google Scholar]

- Huntington, Susan L. 1985. The art of Ancient India—Buddhist, Hindu, Jain. New York: Weatherhill. [Google Scholar]

- Jacq-Hergoualc’h, Michel. 2002. The Malay Peninsula: Crossroads of the Maritime Silk Road (100 BC–1300 AD). Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, Rye-Gyeong 鄭禮京. 1999. Imitation Styles and Deformation Styles of Chinese Buddhist Statues in the Transitional Period: Focusing on Standing Nyorai Statues 過渡期の中國仏像にみられる模倣様式と変形様式—如來立像を中心に. Buddhist Art 仏教芸術 247: 108–23. [Google Scholar]

- Jessup, Helen Ibbitson, and Thierry Zephir, eds. 1997. Sculpture of Angkor and Ancient Cambodia: Millennium of Glory. Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art. [Google Scholar]

- Jian, Ligui 簡鸝媯. 2001. Beiji Qingzhou Diqu Fojiao Shizaoxiang Fengge Wenti Yanjiu 北齊青州地區佛教石造像風格問題研究. Master’s Thesis, Tainan National University of the Arts, Tainan, Taiwan. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Weinuo 金維諾. 1999a. Jianlun Qingzhou Chutu Zaoxiang de Yishu Fengfan 簡論青州出土造像的藝術風範. In Shengshi Chongguan—Shandong Qingzhou Longxingsi Chutu Fojiao Shike Zaoxiang Jinping 盛世重光—山東青州龍興寺出土佛教石刻造像精品. Edited by The National Museum of Chinese History 中國歷史博物館. Beijing: Wenwu Chubanshe, pp. 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Weinuo 金維諾. 1999b. Nanliang yu Beiji Zaoxiang de Chengjiu yu Yingxiang 南梁與北齊造像的成就與影響. Yishushi Yanjiu 藝術史研究 1: 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, Heejung. 2013. The Spread of Sarnath-Style Buddha Images in Southeast Asia and Shandong, China, by the Sea Route. KEMANUSIAAN: The Asian Journal of Humanities 2: 39–60. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Baiyao 李百藥 (563–648). 1972. Beiqi Shu 北齊書. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Chongfeng 李崇峰. 2014. Guanyu Gushan Shiku Zhong de Gaohuan Jiuxue 關於鼓山石窟中的高歡柩穴. In Fojiao Kaogu—Cong Yindu dao Zhongguo (Shang Ce) 佛教考古—從印度到中國(上冊). Shanghai: Shanghai Guji Chubanshe, pp. 357–65. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Yanshou 李延壽 (Tang dynasty). 2008a. Nan Shi 南史. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Yanshou 李延壽 (Tang dynasty). 2008b. Bei Shi 北史. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju. [Google Scholar]

- Malleret, Louis. 1963. L’archéologie du delta du Mékong: Tome Quatrième, Le Cisbassac. Paris: PEFEO. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, Shuangqiao 孟霜橋. 2021. Beiqi Fojiao Fengge Yangshi Laiyuan Yanjiu—Yi Hebei, ShangdongJiaocang Cailiao wei Zhongxin (The study on Origin of Buddha statues styles of the Northern Qi—Centering around Findings Excavated from the Hoard Pits in Hebei and Shandong Province) 北齊佛像風格樣式來源研究—以河北, 山東窖藏材料為中心. Doctor’s thesis, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, China. [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang, Xiu 歐陽修 (1007–1072). 1975. Xin Tang Shu 新唐書. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju. [Google Scholar]

- Pelliot, Paul. 1903. Le Fou-nan. Bulletin de l’École française d’Extrême-Orient 3: 248–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelliot, Paul 伯希和. 1995. Guanyu Yuenan Bandao de Jitiao Zhongguo Shiwen 關於越南半島的幾條中國史文. In Xiyu Nanhai Shidi Kaozheng Yicong (Volume 1) 西域南海史地考證譯叢 (第一卷). Translated by Chengjun Feng 馮承鈞. Beijing: Shangwu Yinshuju, pp. 149–64. [Google Scholar]

- Qingzhou Museum 青州市博物館, ed. 2014. Qingzhou Longxingsi Fujiao Zaoxiao Yishu 青州龍興寺佛教造像藝術. Jinan: Shangdong Art Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, Zongyi 饒宗頤. 1970. <Taiqing Jinye Shendan Jing > Juan Xia yu Nanhai Dili 〈太清金液神丹經〉卷下與南海地理. Zhongguo Wenhua Yanjiusuo Xuebao 中國文化研究所學報 1: 31–76. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Jiyu 任繼愈, ed. 2015. Zhongguo Fojiao Shi· Volume three 中國佛教史·第三卷. Beijing: Zhongguo Shehui Kexue Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Rixin 任日新. 1990. Shandong Zhucheng Faxian Beichao Zaoxiang 山東諸城發現北朝造像. Kaogu 考古 8: 717–26. [Google Scholar]

- Schlegel, G. 1899. Geographical Notes. VII. Tun-Sun 頓遜 or Tian-Sun 典遜 Těnasserim or Tānah-Sāri. T’oung Pao 1: 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shandong Linqu Shanwang Paleontological Fossil Museum 山東臨朐山旺古生物化石博物館, ed. 2010. Linqu Fojiao Zaoxiang Yishu 臨朐佛教造像藝術. Beijing: Kexue Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Yuntao 石雲濤. 2004. 3–6 Shiji Zhong Xi Haishang Hangxian de Bianhua 3–6 世紀中西海上航線的變化. Haijiaoshi Yanjiu 海交史研究 2: 35–48. [Google Scholar]

- Sima, Guang 司馬光 (1019–1086). 2011. Zizhi Tongjian 資治通鑒. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju. [Google Scholar]

- Soper, Alexander C. 1960. South Chinese influence on the Buddhist art of the Six Dynasties period. Bulletin of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities 32: 47–112. [Google Scholar]

- Su, jiqing 蘇繼庼. 1951. Jiayingguo Kao 加營國考. Nanyang Xuebao 南洋學報 1: 18–24. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Yinggang 孫英剛. 2019. Bufa Yanni de Beiji Huangdi: Zhonggu Randeng Fo Shouji de Zhengzhi Yihan 布發掩泥的北齊皇帝: 中古燃燈佛授記的政治意涵. Lishi Yanjiu 歷史研究 6: 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- The National Museum of Chinese History 中國歷史博物館. 1999. Shengshi Chongguan—Shandong Qingzhou Longxingsi Chutu Fojiao Shike Zaoxiang Jinping 盛世重光—山東青州龍興寺出土佛教石刻造像精品. Beijing: Wenwu Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Bangwei 王邦維. 2022. Fojiao Shi Liu Jiang 佛教史六講. Beijing: The Shangwu Yinshuguan. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Zhongluo 王仲犖. 2003. Weijing Nanbei Chao Shi 魏晉南北朝史. Shanghai: The Shangwu Yinshuguan. [Google Scholar]

- Wolters, Oliver William. 1967. Early Indonesian Commerce: A Study of the Origins of Srivijaya. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wolters, Oliver William. 1979. Studying Śrīvijaya. Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 2: 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Xuling 吳虛領. 2010. Dongnanya Meishu 東南亞美術. Beijing: China Remin University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, Mingcai 夏名采. 1998. Qingzhou Longxingsi Fojiao Zaoxiang Jiaocang Qingli Jianbao 青州龍興寺佛教造像窖藏清理簡報. Wenwu 文物 2: 4–15. [Google Scholar]

- Yagi, Haruo 八木春生. 2013. The Transformation of Chinese Buddhism: Late Southern and Northern Dynasties and the Sui Dynasty 中國仏教造像の変容—南北朝後期および隋時代. Kyoto: Hozokan. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Xuanzhi 楊衒之 (the Northern Wei dynasty). 2018. Luoyang Qielan Ji Jiaozhu 洛陽伽藍記校注. Annotated by Xiangyong Fan 範祥雍. Shanghai: Shanghai Classics Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Chongxin 姚崇新. 2005. Qingzhou Beiji Shizaoxiang Kaocha 青州北齊石造像考察. Yishushi Yanjiu 藝術史研究 7: 309–42. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Chongxin 姚崇新. 2014. Fojiao Haidao Chuanru Shuo, Dian Mian Dao Chuanru Shuo Bianzheng 佛教海道傳入說, 滇緬道傳入說辯證. In Xiyu Kaogo, Shidi, Yuyan Yanjiu Xinshiye: Huang Wenbi Zhong Rui Xibei Kaochatuan Guoji Xueshu Yantaohui Lunwenji 西域考古·史地·語言研究新視野: 黃文弼中瑞西北考查團國際學術研討會論文集. Edited by Xinjiang Rong 榮新江 and Yuqi Zhu 朱玉麒. Beijing: Kexue Chubanshe, pp. 459–96. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Chongxi 姚崇新. 2016. Shilun Fu-nan yu Nanchao de Fojiao Yishu Jiaoliu—Cong Dongnanya Chutu de Nanchao Fojiao Zaoxiang Tanqi 試論扶南與南朝的佛教藝術交流—從東南亞出土的南朝佛教造像談起. Yishushi Yanjiu 藝術史研究 18: 269–97. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Silian 姚思廉 (564–637). 1972. Chen Shu 陳書. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Silian 姚思廉 (564–637). 2020. Liang Shu 梁書. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Zhaoyuan 張昭遠 (894–972). 1975. Jiu Tang Shu 舊唐書. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Ling 趙玲. 2016. Lun Gu Yindu Foxiang de Haishang Chuanbo Zhi Lu 論古印度佛像的海上傳播之路. In Shanhe Zhi Sheng: ‘Zhongguo Fojiao yu Haishang Sichou Zhi Lu’ Yantaohui Lunwenji Shangce 禪和之聲: “中國佛教與海上絲綢之路”研討會論文集上冊. Edited by Sheng Ming 明生. Beijing: Zongjiao Wenhua Chubanshe, pp. 33–46. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Ling 趙玲. 2018. Qingzhou Beiji Foxiang Yuanyuan de Xin Sikao 青州北齊佛像淵源的新思考. Nanjing Yishu Xueyuan Xuebao (Meishu yu Sheji) 南京藝術學院學報 (美術與設計) 4: 92–98. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).