Materialized Wishes: Long Banner Paintings from the Mogao Caves of Dunhuang

Abstract

1. Introduction

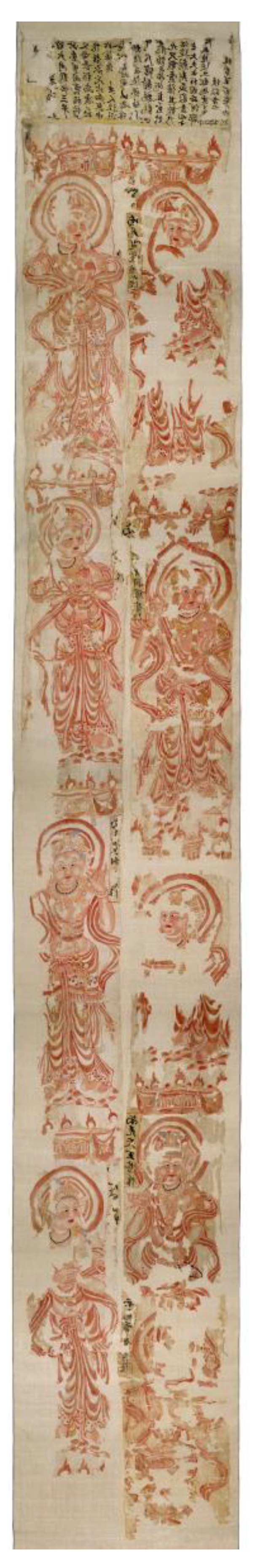

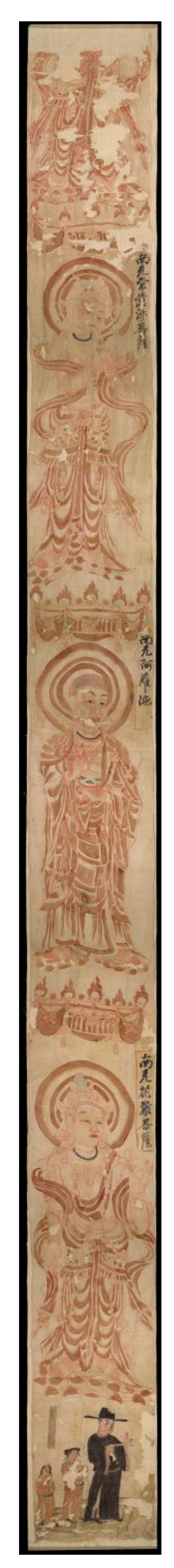

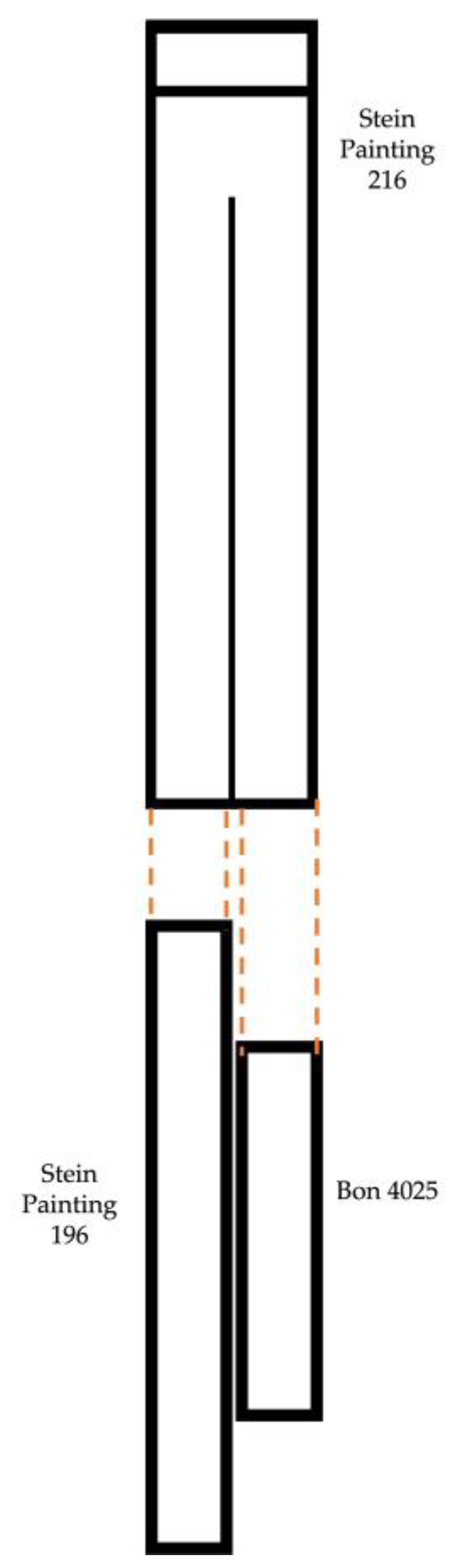

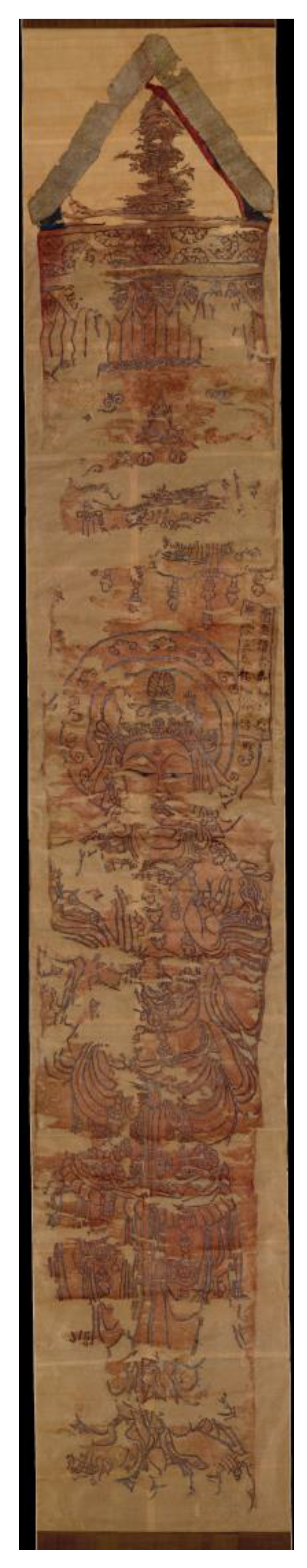

2. Long Banner of Bodhisattvas and Its Reconstruction

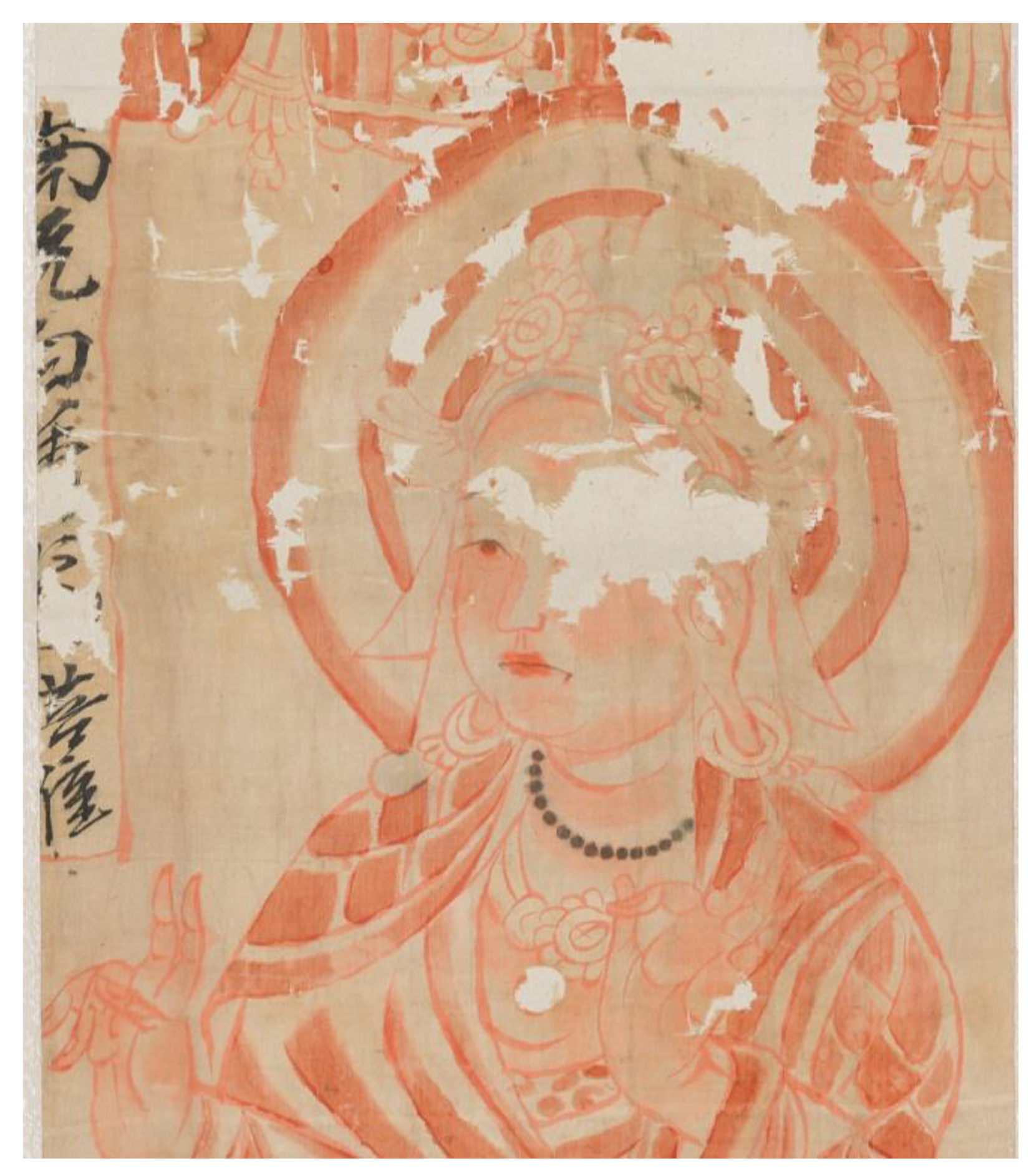

2.1. The Inscription

Controller of the Guiyi army…member of the Order of Silver-blue Luminous Salary, additional President of the Board of Works, Censor, Upper Pillar to the State…of Xihe jun, Ren Yanchao drawing blood respectfully (caused to be) painted this forty-nine-chi banner in one strip. This banner suspended on high from a dragon hook…reach straight to… twisting about and flapping in the wind like a bird in flight, like the coloured (hangings) in the Western Apartments of the Palace. May his Excellency’s life be as that of the hills, his salary vast as the sea. May his Lady Wife long be spared; may her flower-like countenance forever bloom. Next, it is the object of this offering that his father and mother in the plain may long continue to announce themselves in health and security, and for them are desired the same blessings as for their son and his bride. The time being Da Zhou, third year of Xiande…7

2.2. The “Forty-Nine-Chi Banner”

2.3. Reconstruction of the Long Banner of Bodhisattvas

3. Healing Ritual Revisited

The Bodhisattva Saving and Freeing said to the Buddha: “If there should be some man or woman, gently born, who is desperately ill and lies on his bed in pain and distress, without anyone to aid or to defend him; I now must urge and beg the priesthood to fast wholeheartedly for seven days and nights, keeping to the Eight Commandments, and carrying out ritual processions at the six hours of the day. Let this sutra be read in its entirety forty-nine times. I urge them to light a seven-tiered lamp, and to hang up parti-colored, life-lengthening spirit-banners… These should be forty-nine feet long. The seven-tiered lamps should have seven lights per tier, following a form like a cartwheel. Again, should [such a person] fall into danger or be imprisoned, with fetters loading down his body, he should have parti-colored spirit-banners made and forty-nine lamps lit, and should release various kinds of living creatures, to the number of forty-nine …”14

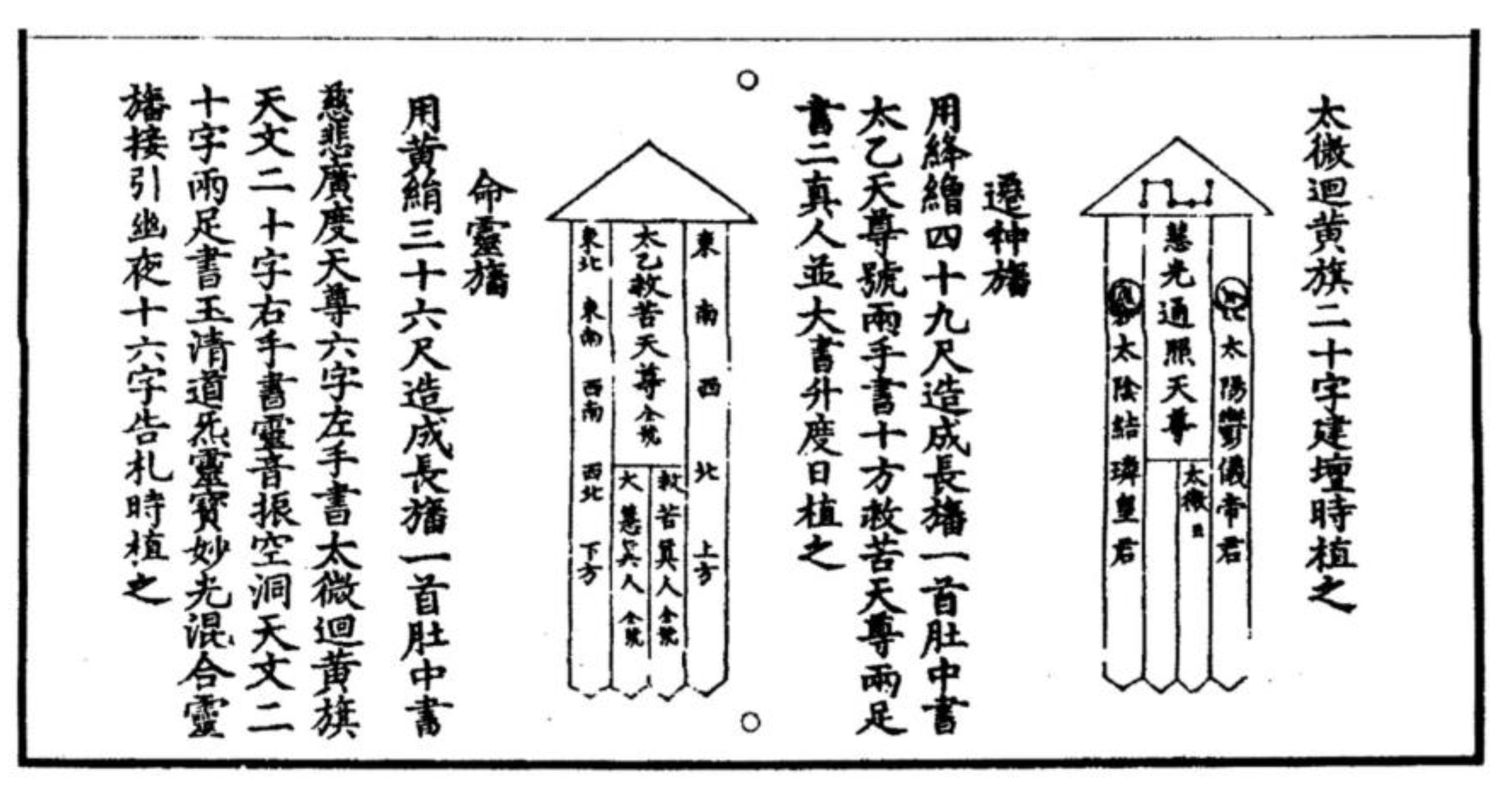

4. Sharing the Form: A Comparison with Daoist Examples

Using colorful silk, make the “Spirit-Moving Precious banner,” which measures forty-nine chi in height. Or one can make seven small-sized banners. Hang them on the long staff facing wind, so that all sins are blown way and extinguished.19

5. Buddhist Banners for Longevity and Soul Saving: Stein Painting 216

5.1. Textual Inspiration to the Long Banner

On the 13th day of the 10th month of the 6th xinchou year of the Tianfu [941], the female disciple of pure faith, the young woman of the Cao family, commissioned the copying of the Hṛdāyaprajñā- pāramitāsūtra in one roll, the Sutra on the Extension of the Span of Life (Xuming jing 續命經) in one roll, the Sutra on Longevity and the Span of Life (Yanshou ming jing 延壽命經) in one roll, and the Sutra of Mārīcī God in one roll, respectfully offered on behalf of herself, as she suffers from difficulties. Today she presents a number of scriptures, since the medicine dumplings that were bestowed again and again in the morning still have not made her well, and she now lies sick [in bed]. Beginning to realize her former misdeeds, she humbly begs the Great Holy Ones to relieve her hardships and lift her out of danger, and that the mirror will reflect the virtue of the copying of scriptures. She [therefore] hopes to be protected, that this troublesome danger will be eliminated, deceased family debtors will receive their capital [when] the merit is divided, and that they will [subsequently] go for rebirth in the Western [Pure Land]. With a mind full of prayer, she eternally supplies these [scriptures] as eternal offerings […].31

5.2. Blood Painting?

5.3. Textile Offerings

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 1 | |

| 2 | They are now in museums worldwide: the Stein Collection at the British Museum in England; the Pelliot Collection at the Musée Guimet in France; the Otani Collection at the National Museum in Korea; the Lüshun Museum and the Palace Museum at Beijing in China; and the State Hermitage Museum in Russia. |

| 3 | These exceptions are Stein Painting 195 at the British Museum and MG 17675, MG 17791, and EO 1165 at the Musée Guimet. |

| 4 | The width of silk or hemp was determined by a loom’s width, which was 50–60 cm in most cases. See (Wang 2013, p. 279). |

| 5 | It provides a reference to an original configuration for similar paintings on which a single column of bodhisattvas is painted on a narrow width of silk, such as Stein Painting 205, MG 17675, and MG 17791. |

| 6 | The direction of reading the inscription opposes that of the traditional Chinese writing. Imre Galambos argued that the left-to-right reading direction was not a mistake but a common local phenomenon in the Dunhuang area in the ninth to tenth centuries. See (Galambos 2020, pp. 139–94). |

| 7 | The inscription was originally transcribed by Arthur Waley and adapted by Whitfield in 1983. The author has altered “forty-nine foot” to “forty-nine chi” for more accurate identification. Also, the order of the transcribed inscription, which should be read from left to right, is corrected by the author as the following: “………歸義軍節度內□…………使銀青光祿 大夫檢校工部尚書兼御 史大夫上柱國西河郡 任延朝刻血敬畫四十 九尺飜壹條其飜乃 龍鉤高曳直至於 □□宛轉飄飄似 飛鳩西□綵□願 令公壽同出嶽祿 比滄溟夫人延遐 花顔永茂次爲原中 父母長報安康在 比妻男同霑福祐于 時大週顯德三年.” See (Waley 1931, pp. 186–87; Whitfield 1983, p. 33). |

| 8 | Jacques Giès and Haewon Kim argue that it is not the actual length but a symbolic expression. See (Giès et al. 1994, p. 295; Kim 2013, p. 154). |

| 9 | This specific painting style is also found in Long Banner with Five Apsaras (EO 1166) at the Musée Guimet in Paris, France. In contrast to the preceding examples, it features flying five apsaras (female spirit of the clouds and waters in Hindu and Buddhist culture) on a piece of silk that is 19.6 cm wide. Even though the subject matter is different, there are some stylistic similarities: red outlines, red ink washes, and a spontaneous drawing style. However, its width is shorter than those of the three long banners such as Stein Paintings 196 and 217 and Bon 4025. In addition, there is no hint of the application of yellow and blue hues. Thus, it is safe to conclude that this painting must have been part of other painting. With the exception of the second apsara from the top, the four other apsaras face the right side of the viewer, which suggests that this banner might have been paired with another with flying apsaras facing the opposite direction. In my opinion, however, we cannot assume that EO 1166 was a piece from the left based on the apsaras’ orientation. It could have been the far-right piece because of the location of its selvedge. Looking closely, one can find the selvedge on the right side, whereas the opposite side should have been cut and sewn. In instances where the silk was split for making streamers at the bottom, there are some cases in which the far right or left streamer keeps its original selvedge. See (Giès et al. 1994, p. 85 and Figure 50). |

| 10 | The Ōtani Collection refers to a group of objects from Central Asia that Ōtani Kozui (1876–1948), the twenty-second Abbot of the Nishi Honganji Temple, and his colleagues excavated and obtained during three expeditions to the region in 1902–1914. The collection is mostly comprised of mural paintings, banner paintings, and sculptures. Part of the original Ōtani Collection is now displayed in the National Museum of Korea. In the collection, there are more than fifteen paintings on paper or textile. See (Kim 2013, pp. 32–43). |

| 11 | His argument is based on the reconstruction of Stein Painting 214 (1, 2) with EO 3647 and EO 3648. See (Whitfield 1983, p. 35). |

| 12 | In the inscription of Stein Painting 216, “飜,” which has the same phonetic pronunciation (fan) as that of幡, was used. |

| 13 | Some examples are Bhaisajyaguru Sutra (藥師琉璃光如來本願功德經), T. 450, 404:20c; Consecration Sutra (佛說灌頂經), T. 1331, 535:13b; and The Liturgy for Cultivating Dharani for the Buddha Above the Leading General Atavaka (阿吒薄俱元帥大將上佛陀羅尼經修行儀軌), T. 1239, 196:11–12a. |

| 14 | Fascicle 12 of the Consecration Sutra is Consecration Sutra Spoken by the Buddha that Rescues from Sin and Enables Salvation from Birth and Death (Fushuo guanding bachu guozui shengsi dedu jing 佛說灌頂拔除過罪生死得度經, T. 1331). See (Birnbaum 1979, pp. 56–57). The passage’s translation is from (Soper 1959, p. 171). |

| 15 | Ning Qiang argues that the multitiered lamp wheel probably originated from the western region and was eventually incorporated to the Chinese Lantern Festival. For more information on the origin of the festival and its local adaptation, see (Ning 2004, pp. 122–33). |

| 16 | The close relationship between the lighting of lamps and the Bhasajiaguru cult is discussed intensively in Shi Zhiru’s recent publication. See Zhiru Shi, “Lighting Lamps to Prolong Life: Ritual Healing and the Bhaiṣajyaguru Cult in Fifth- and Sixth-Century China,” in Buddhist Healing in Medieval China and Japan University of Hawaii Press, 2020), pp. 91–117. |

| 17 | High resolution photograph can be assessed at https://www.e-dunhuang.com/cave/10.0001/0001.0001.0220 (Accessed on 1 March 2021). |

| 18 | Sometimes it is translated as a “spirit-removing banner.” |

| 19 | DZ 371:7 the original text is: “又以繒綵 造遷神寳旛 長四十九尺 或作小旛七首 懸於長竿任風 飛颺禹罪皆滅” (DZ 371: 7). |

| 20 | Stein Painting 217 (1919,0101,0.217) is painted on a full width silk support, which shows selvedges at both ends. |

| 21 | For the rest of the types of painted banners from Cave 17 (i.e., not long banners), Xie Shengbao and Xie Jing propose that a large group of Buddhist paintings from the Library Cave could have been used for the Water Land Ritual even though during this time period the paintings were not called “Water Land Paintings.” I believe it is a worth reviewing their argument but further discussions are also needed on how the paintings can be grouped and where the paintings were actually used. See (Xie and Xie 2006a, 2006b). |

| 22 | Waley reads this inscription as “Many Precious Signs 多寶相.” However, when I examined the inscription in person, I was not able to find the character 多. I believe he misread 無(无)as 多. See (Waley 1931, p. 186). |

| 23 | The character of the Flower Adorned Bodhisattva written on Stein Painting 196 is read not as huá 華 but as huā 花. |

| 24 | The other one can be read partially as follows: 南無白香(?)象(?)菩薩. |

| 25 | This sutra, previously lost, was reconstructed with the manuscripts found in Cave 17 of the Mogao Caves of Dunhuang. See (Chou 2009). |

| 26 | The five ānantaryakarma includes “patricide, matricide, killing an arhat, spilling the blood of a buddha, and causing schism in the monastic order.” The icchantika means “incorrigible” in Sanskrit, referring to people “who have lost all potential to achieve enlightenment.” See (Buswell and Lopez 2014, pp. 40–41, 370). |

| 27 | According to Dorothy C. Wong, another example of this sutra being the textual foundation of a Buddhist sculpture is a stele called Chen Hailong zaoxiang bei 陳海龍造像碑 from Shanxi, dated 562. This stele, in contrast to Stein Painting 216 and its bodhisattvas, displays twenty-four small buddhas with legible inscriptions of their names. Their visual representations are not distinguishable, a situation similar to the bodhisattvas from the group of the long banners. For this stele and its textual resource, see (Wong 2007, pp. 266–70). |

| 28 | The name of the sutra in the Tibetan canon is hphags-pa thar-pa chen-po phyogs-suryas-pa hgyod-tshans-kyis sdig-sbyans te sans-rgyas-su grub-par rnam-par-bkod-pa shes-bya-ba theg-pa chen-pohimdo (vol. 37, no. 930), which can be translated as “Sheng da jietuo fangguang chanhui miezui chengfo zhuangyan dacheng jing 聖大解脫方廣懺悔滅罪成佛莊嚴大乘經.” See (Chou 2009, pp. 8–9). |

| 29 | The names of the Daoist deities are resonant with the aforementioned “jiuku pusa” or Savior Bodhisattva from Suffering, who was one of the popular bodhisattvas featured in painted banners. This is only one example of many cases of Buddho–Daoist borrowings in visual materials. |

| 30 | Among the manuscripts from Cave 17, several apocryphal sutras related to lengthening one’s life span were discovered. One example is Sutra on Prolonging Lifespan (fo shuo yan shouming jing 佛說延壽命經, T2888). P. 2171 is the case in point. The practice of copying this type of text was popular in the tenth century. A colophon to P. 2805 (the Sutra of Goddess Marīcī) tells that a daughter from the Cao 曹 family clan copied four sutras, including Sutra on the Heart of Prajñā-pāramitā (Bore [boluomiduo] xin jing 般若[波羅蜜多]心經), Sutra on Extending Lifespan (Xuming jing 續命經), Sutra on Prolonging Lifespan (Yanshouming jing 延壽命經), and Sutra of Goddess Marīcī (Molizhitian jing 摩利支天經), in order to aid her sickness. For the full translation of the colophon, see (Hao 2020, pp. 87–88; Sørensen 2020, pp. 21–22). |

| 31 | The translation is slightly modified from (Sørensen 2020, pp. 21–22, no. 34). The original inscription is “天福六年 [(941)] 辛丑 歲 十月十三日清信女弟子小娘子曹氏敬寫般若心經一卷, 續命經一卷, 延壽命經一卷, 摩利支天經一卷, 奉為己躬患難, 今經數晨, 藥餌頻施不蒙抽; 今遭卧疾, 始悟前非, 伏乞大聖濟難拔危, 鑒照寫經功德, 望仗危難消除, 死家債主領資福分, 往生西方, 滿其心願, […].” |

| 32 | P. 2171 is entitled Sutra on Prolonging Lifespan, but its content is different from S. 2428 (T2888), which has the same title. |

| 33 | Stein Painting 217 bears a similar inscription: “May the land be peaceful and its people prosperous; May the rural shrines continually flourish. May the whole house be clean and happy; May the lives (of the inhabitants) be long extended.” See (Waley 1931, p. 188). |

| 34 | Before this result, Whitfield speculated that “the red pigment used was probably a local red earth, tuhong 土紅 for the washes and cinnabar, zhu 朱 for the brighter outlines.” (Whitfield 1983, p. 32; Kim 2013, p. 237). |

| 35 | This sutra was copied numerous times, especially for the Tibetan emperor during the 830s–840s. See (van Schaik et al. 2015, pp. 117–18). |

| 36 | No indication of mineral pigment was based on the result of VIS spectroscopy (van Schaik et al. 2015, p. 118). |

| 37 | In early Buddhism in India, this idea is deeply rooted in jātaka tales, which are tales of previous lives of the Buddha. They describe how the Buddha was compassionate enough to cut his own body parts to save other sentient beings. For the history of self-immolation, see (Benn 2007, pp. 7–18). |

| 38 | For the practice’s scriptural basis, see (Kieschnick 2000, pp. 178–81). According to Jimmy Yu’s publication on blood writing, the most popular sutras that preached the benefits of self-sacrifice were written in blood. Such texts include the Lotus Sūtra, Brahma Net Sūtra, Flower Garland Sūtra, and Diamond Sūtra. See (Yu 2012, p. 41). |

| 39 | For the materiality of the colorant cinnabar in early Chinese visual history, see (Lai 2015). |

| 40 | This painting method is reminiscent of an illuminated manuscript in which the first page is the painting of a sermon scene. Sutras were often copied on paper that was dyed dark blue and then written and painted on using gold foil and gold or silver pigments with hints of colors, much like the techniques used with the painted long banners. Moreover, by using gold to accentuate the outlines of the figures and architecture, the illuminated painting is in sharp contrast with its dark background and the bright line drawings. |

References

Primary Sources

Dunhuang Manuscripts in the Pelliot Collection.P. 2171.P. 2613.P. 2805.P. 3638.Primary Buddhist/Daoist Sources.T. 450 Yaoshi liuliguang rulai benyuan gongde jing藥師琉璃光如來本願功德經.T. 1239 Azhabaoju yuanshuai dajiang shang fo tuoluoni jing xiuxing yigui阿吒薄俱元帥大將上佛陀羅尼經修行儀軌.T. 1331 Guanding jing 灌頂經.T. 2871 Datong fangguang chanhui miezui zhuangyan chengfo jing 大通方廣懺悔滅罪莊嚴成佛經.T. 2888 Fo shuo yan shouming jing 佛說延壽命經.DZ 371 Taishang dongxuan lingbao santu wuku badu shengsi miaojing 太上洞玄靈寶三塗五苦拔度生死妙經.DZ 373 Taishang dongguan lingbao wangsheng jiuku miaojing 太上洞玄靈寳徃生救苦妙經.DZ 466 Lingbao lingjiao jidu jinshu 靈寶領教濟度金書.Secondary Sources

- Benn, James A. 2007. Burning for the Buddha: Self-Immolation in Chinese Buddhism. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaum, Raoul. 1979. The Healing Buddha. Boulder: Shambhala. [Google Scholar]

- Buswell, Robert E., and Donald S. Lopez. 2014. The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chou, Po-Kan 周伯戡. 2009. “Zhongshi ji zhongguo zaijia pusa zhi chanfa: Dui 《Datong fangguang chanhui miezui zhuangyan chengfo jing》 de kaocha” 中世紀中國在家菩薩之懺法: 對《大通方廣懺悔滅罪莊嚴成佛經》的考察 [An investigation of a confessional ceremony in medieval Chinese Buddhism]. Taida Foxue Yanjiu 18: 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Feugère, Laure. 2011. Introduction. In Textiles from Dunhuang in French Collections. Edited by Zhao Feng. Shanghai: Donghua University, pp. 14–23. [Google Scholar]

- Galambos, Imre. 2020. Dunhuang Manuscript Culture. Boston: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Giès, Jacques, Hero Friessen, and Roderick Whitfield. 1994. Les arts de l’Asie centrale: La collection Paul Pelliot du Musée National des Arts Asiatique-Guimet. 3 vols. London: Serindia. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, Chunwen. 2020. Dunhuang Manuscripts: An Introduction to Texts from the Silk Road. Translated by Stephen F. Teiser. Diamond Bar: Portico Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Shih-shan Susan. 2012. Picturing the True Form: Daoist Visual Culture in Traditional China. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Shih-shan Susan. 2015. Daoist Uses of Color in Visualization and Ritual Practices. In Color in Ancient and Medieval East Asia. Edited by Mary M. Dusenbury and Monica Bethe. Lawrence: Spencer Museum of Art, the University of Kansas, pp. 223–33. [Google Scholar]

- Kieschnick, John. 2000. Blood Writing in Chinese Buddhism. Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies 23: 177–94. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Haewon, ed. 2013. Kungnip Chungang Pangmulgwan sojang chungangashia chonggyo hoihwa 국립중앙박물관 소장 중앙아시아 종교 회화 [Central Asian religious paintings in the National Museum of Korea]. Seoul: Kungnip Chungang Bangmulgwan. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Haewon. 2020. An Icon in Motion: Rethinking the Iconography of Itinerant Monk Paintings from Dunhuang. Religions 11: 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, Li-Ying. 1994. Confession et contrition dans le bouddhisme chinois du Ve au Xe siècle. Paris: Publications de l’École française d’Extrême-Orient. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, Guolong. 2015. Colors and Color Symbolism in Early Chinese Ritual Art. In Color in Ancient and Medieval East Asia. Edited by Mary M. Dusenbury. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, pp. 25–43. [Google Scholar]

- Mollier, Christine. 2008. Buddhism and Taoism Face to Face: Scripture, Ritual, and Iconographic Exchange in Medieval China. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ning, Qiang. 2004. Art, Religion, and Politics in Medieval China: The Dunhuang Cave of the Zhai Family. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Robson, James. 2008. Signs of Power: Talismanic Writing in Chinese Buddhism. History of Religions 48: 130–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Angela. 2013. Determining the Value of Textiles in the Tang Dynasty In Memory of Professor Denis Twitchett (1925–2006). Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 23: 175–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Zhiru. 2020. Lighting Lamps to Prolong Life: Ritual Healing and the Bhaiṣajyaguru Cult in Fifth- and Sixth-Century China. In Buddhist Healing in Medieval China and Japan. Edited by C. Pierce Salguero and Andrew Macomber. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, pp. 91–117. [Google Scholar]

- Soper, Alexander C. 1959. Literary Evidence for Early Buddhist Art in China. Artibus Asiae. Supplementum 19: 1–296. [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen, Henrik H. 2020. Giving and the Creation of Merit: Buddhist Donors and Donor Dedications from 10th Century Dunhuang. BuddhistRoad Paper 4: 3–40. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, Aurel. 1921. Serindia: Detailed Report of Explorations in Central Asia and Westernmost China. Oxford: The Clarendon Press, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- van Schaik, Sam. 2014. Towards a Tibetan Paleography: Developing a Typology of Writing Styles in Early Tibet. In Manuscript Cultures: Mapping the Field. Edited by Jörg Quenzer, Dmitry Bondarev and Jan-Ulrich Sobisch. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 299–340. [Google Scholar]

- van Schaik, Sam, Agnieszka Helman-Ważny, and Renate Nöller. 2015. Writing, Painting and Sketching at Dunhuang: Assessing the Materiality and Function of Early Tibetan Manuscripts and Ritual Items. Journal of Archaeological Science 53: 110–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitali, Roberto. 1990. Early Temples of Central Tibet. London: Serindia. [Google Scholar]

- Waley, Arthur. 1931. A Catalogue of Paintings Recovered from Tun-huang by Sir Aurel Stein, K.C.I.E. London: British Museum and the Government of India. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Binghua. 2013. A Study of the Tang Dynasty Tax Textiles (Yongdiao Bu) from Turfan. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 23: 263–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Le. 2007. Banners. In Textiles from Dunhuang in UK Collection. Edited by Zhao Feng. Shanghai: Donghua University Press, pp. 58–59. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Michelle. 2016. The Thousand-armed Mañjuśrī at Dunhuang and Paired Images in Buddhist Visual Culture. Archives of Asian Art 66: 81–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitfield, Roderick. 1983. The Art of Central Asia: The Stein Collection in the British Museum. Tokyo: Kodansha International, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, Dorothy C. 2007. Guanyin Images in Medieval China, Fifth to Eighth Centuries. In Bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara (Guanyin) and Modern Society. Taipei: Chung-Hwa Institute of Buddhist Studies, pp. 254–302. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Hung. 1996. Rethinking Liu Sahe: The Creation of a Buddhist Saint and the Invention of a ‘Miraculous Image’. Orientations 27: 32–43. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Shengbao 謝生保, and Jing Xie 謝静. 2006a. “Dunhuang wenxian yu Shuilu fahui: Dunhuang Tang Wudai shiqi Shuilu fahui yanjiu” 敦煌文獻與水陸法會: 敦煌唐五代时期水陸法會研究 [Dunhuang manuscripts and the study of the ceremony of saving lives of the Water and the Land during the Tang Dynasty to the Five Dynasties]. Dunhuang Yanjiu 敦煌研究 2: 40–48. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Shengbao 謝生保, and Jing Xie 謝静. 2006b. “Dunhuang yihua yu Shuilu hua: Dunhuang Tang Wudai shiqi Shuilu fahui yanjiu zhi er” 敦煌遗畫與水陸畫: 敦煌唐五代时期水陸法會研究之二 [Dunhuang manuscripts and the study of the ceremony of saving lives of the Water and the Land during the Tang Dynasty to the Five Dynasties, second part]. Dunhuang Yanjiu 敦煌研究 4: 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Yim, Yŏng-ae. 1991. “Chungguk kodae pulgyobŏnŭi yangshik pyŏnch’ŏn’go” 古代 中國 佛敎幡의 樣式變選考 [Stylistic changes in Buddhist banners from the ancient China]. Misul sahak yŏn’gu 189: 69–109. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Jimmy. 2012. Sanctity and Self-Inflicted Violence in Chinese Religions, 1500–1700. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hwang, Y. Materialized Wishes: Long Banner Paintings from the Mogao Caves of Dunhuang. Religions 2023, 14, 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14010058

Hwang Y. Materialized Wishes: Long Banner Paintings from the Mogao Caves of Dunhuang. Religions. 2023; 14(1):58. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14010058

Chicago/Turabian StyleHwang, Yoonah. 2023. "Materialized Wishes: Long Banner Paintings from the Mogao Caves of Dunhuang" Religions 14, no. 1: 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14010058

APA StyleHwang, Y. (2023). Materialized Wishes: Long Banner Paintings from the Mogao Caves of Dunhuang. Religions, 14(1), 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14010058