Significance of the Śrāvastī Miracles According to Buddhist Texts and Dvāravatī Artefacts

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Significance of the Śrāvastī Miracles According to Buddhist Texts and Dvāravatī Artefacts

2.1. Śrāvastī Miracles as One of the Buddha’s Necessary Deeds

Sv: [As Bodhisattvas (i.e., future Buddhas) in our final birth], we will display miracles (pāṭihāriya) that will, among other things, shake the earth, which is bounded by the circle of ten thousand mountains, when (1) the all-knowing Bodhisattva enters his mother’s womb, (2) is born, (3) attains awakening, (4) turns the wheel of dharma, (5) performs the “twin miracle” (yamakapāṭihāriya), (6) descends from the realm of the gods, (7) releases his life force, [and] (8) attains cessation

2.2. Śrāvastī Miracles as Principal Miracles Performed Only by the Buddha

2.3. Śrāvastī Miracles as a Means of Conversion into Buddhism

Paṭis: Renunciation (nekkhamma) succeeds: this is supernatural powers (iddhi). It removes (paṭiharati) desire (kāma-cchanda): this is miracle demonstration (pāṭihāriya). Non-malevolence (abyāpada) succeeds: this is supernatural powers (iddhi). It removes (paṭiharati) malevolence (byāpada): this is miracle demonstration (pāṭihāriya). Sight consciousness (ālokasaññā) succeeds: this is supernatural powers (iddhi). It removes (paṭiharati) stolidity and torpor (thīna-middha): this is miracle demonstration (pāṭihāriya). Calmness (avikkhepa) succeeds: this is supernatural powers (iddhi). It removes (paṭiharati) distraction (uddhacca): this is miracle demonstration (pāṭihāriya). The arahant path (arahattamaggo) succeeds: this is supernatural powers (iddhi). It removes (paṭiharati) all defilements (sabba-kilesa): this is miracle demonstration (pāṭihāriya). Therefore, [it is called] iddhipāṭihāriya.

Sv-pṭ: Here, as to the etymology of the term pāṭihāriya, they speak of pāṭihāriya because of taking away opponents (paṭipakkhaharaṇato), [that is] because of removing such defilements as lust. But the Blessed One has no opponents such as lust to be taken away. In the case of worldlings too, the spiritual powers occur when the opponents [of their minds] have been destroyed, that is, when their minds are devoid of defilements and possessed of eight excellent qualities. Therefore it is not possible to speak of pāṭihāriya in the case, using the expression in relation to them. But the defilements in those who are to be trained by the Blessed One, the Great Compassionate One, are opponents; so if the word pāṭihāriya is used because of the ‘taking away of those opponents,’ in such a case this is correct usage of the term. Or alternatively: The sectarians are the opponents of the Blessed One’s teaching. Pāṭihāriya signifies the taking away of them. For they are taken away (haritā), removed, by means of psychic powers, mind-reading, and instruction, by taking away their views and by rendering them incapable of expounding their views…9

2.3.1. The Miracle of Supernormal Accomplishment

2.3.2. The Miracle of Mind-Reading

2.3.3. The Miracle of Exposition

- a.

- Prose sermons

- b.

- Verse sermons

2.3.4. Effects

- a.

- The Effect of Seeing the Miracle Display of the Buddha

- b.

- The Effect of Hearing the Preaching of the Buddha

- (1)

- ye dhammā hetuppabhavā

- (2)

- tesaṃ hetuṃ tathāgato āha

- (3)

- tesañ ca yo nirodho

- (4)

- evaṃvādī mahāsamaṇo ti (Vin i 40).

(1) ye dhammā hetupprabhavā 21(2) tesaṃ hetuṃ tathāgato āha

- (1)

- ye dhammā hetupprabhavā

- (2)

- yesaṃ hetuṃ tathāgato

- (3)

- āha tesañ ca yo niro-–dho

- (4)

- evaṃvādī mahāsamano

- (1)

- ye dhammā hetupprabhavā

- (2)

- yesaṃ hetuṃ tathāgato āha

- (3)

- tesañ ca yo nirodho

- (4)

- evaṃvādī mahāsamano

- (1)

- ye dhammā hetupprabhavā

- (2)

- yesaṃ hetuṃ tathāgato

- (3)

- āha tesañ ca yo niro-

- (4)

- –dho evaṃvādī mahāsama-

- (5)

- –no.

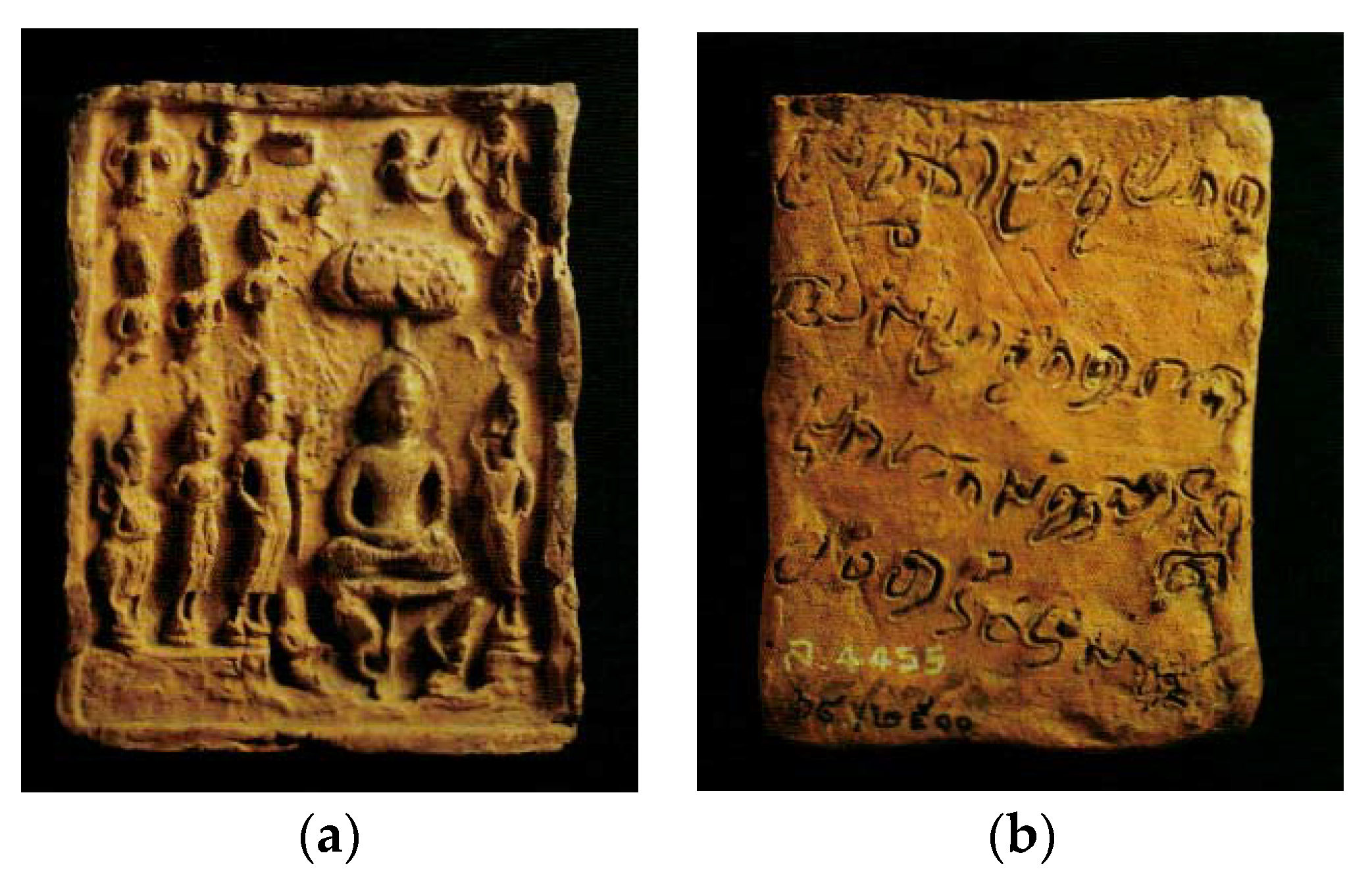

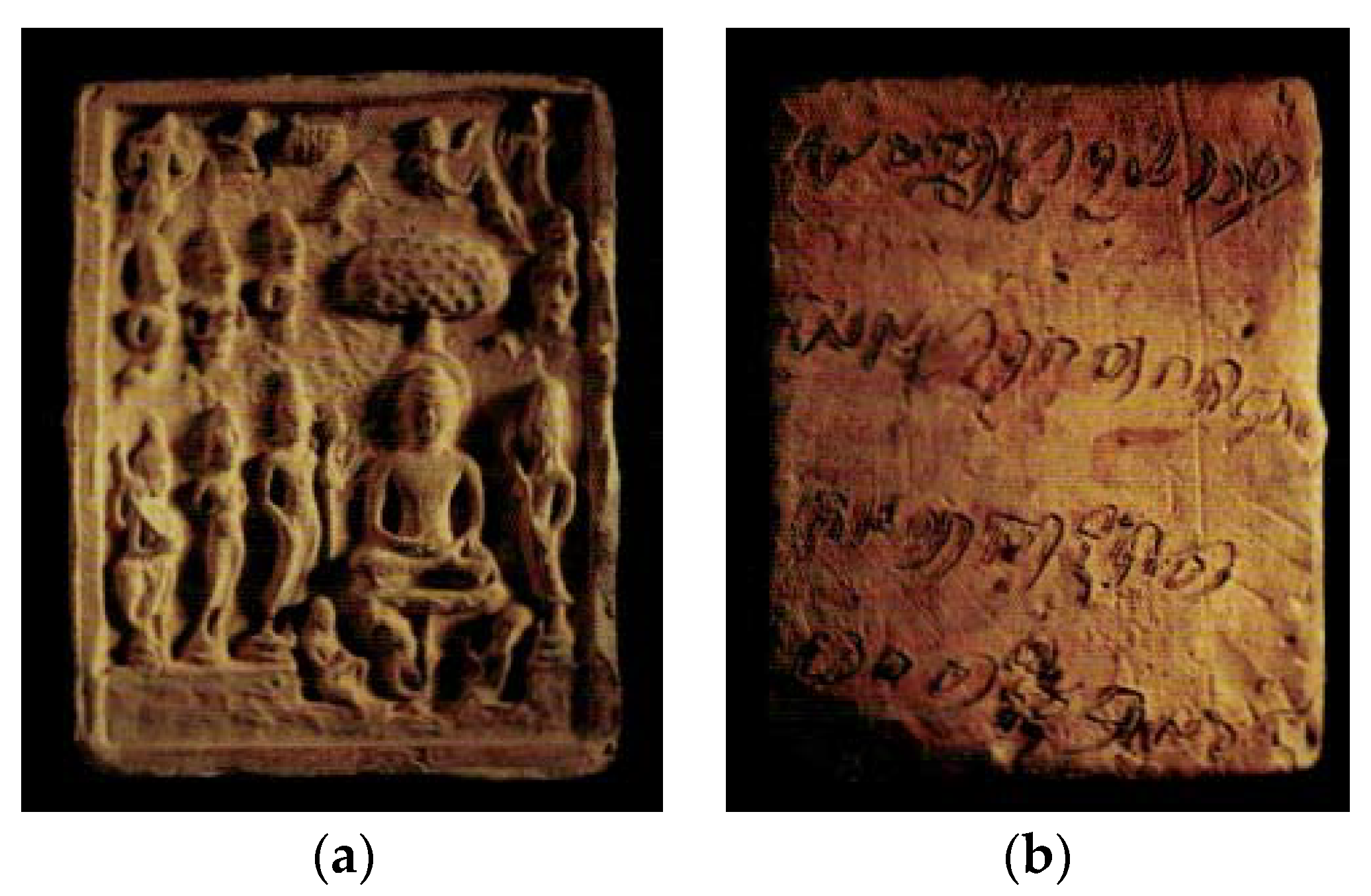

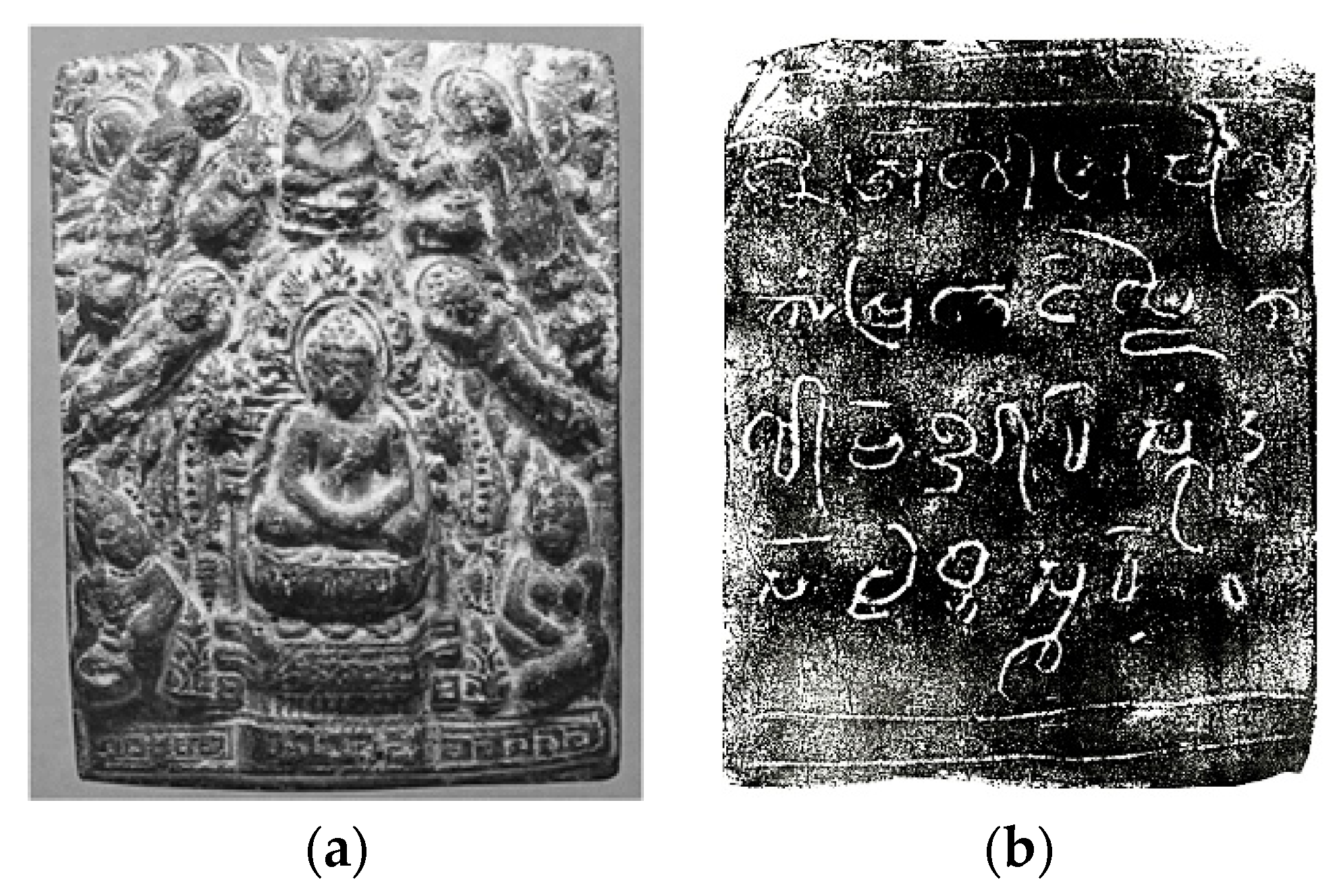

Again, when the people make images and caityas which consist of gold, silver, copper, iron, earth, lacquer, bricks, and stone, or when they heap up the snowy sand (lit. sand-snow), they put in the images or caityas two kinds of sarīras [i.e., relics]. 1. The relics of the Great Teacher. 2. The gāthā of the Chain of Causation [i.e., ye dhammā or paṭiccasamuppāda gāthās]. […] If we put these two in the images or caityas, the blessings derived from them are abundant.

2.4. Śrāvastī Miracles as Supporting the Idea of Making the Buddha Images as an Act of Merit

But phra phim must have ceased at an early date to be regarded merely as souvenirs. With the development of a profound veneration for images, the act of making a statue of the Buddha or other figure symbolic of the religion had long been established as a source of merit. But to cast a bronze image or carve a statue of wood or stone was not within the reach of most people, and poor persons desirous of acquiring merit to assure their rebirth under more prosperous conditions, found in the impression of an effigy upon a lump of potter’s clay, the means of accumulating such merit without the assistance of superior intelligence or wealth. Those having the desire and the leisure to do so, might make a very large number of such impressions

- (1)

- naiavoapuṇya (ไนอ์โวอ์ปุณย)

- (2)

- kamaraṯeṅ baiḍa ka (กมรเตง์ ไปฑ ก)

- (3)

- romārskuṅda (โรม์อาร์สกุํ ท)

- (4)

- sjāṯisamăr (ส์ชาติสมร)

The ānisaṃsa ideology has permeated the expression of Buddhism for centuries. It is entwined, interwoven, with the notions of merit (puñña, puṇya), giving (dāna), and aspiration (adhiṭṭhāna, the intentionality of action). Ānisaṃsa and adhiṭṭhāna overlap with dāna: they are components of the dynamics of the interior world of dāna, they are its instrumentality

Therefore, a wise man, perceiving his own happiness, should always erect a Buddha image whether small or large. That image, well-made, either in wood, stone or in pure clay, or with sandalwood, with gold or silver, or with pearls or bronze. According to one’s ability, an image of Buddha should be made. The donors, who constantly give, obtain happiness and wealth as long as they transmigrate in this world among gods or men…29

3. Conclusions and Discussion

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviation

| Abhidh-k-bh | Pradhan, P. (Ed.). (1967). Abhidharmakośabhāṣyam of Vasubandhu. (Tibetan Sanskrit Works Series 8). Patna. |

| AN | Morris, R., and Hardy, E. (Eds.). (1885–1900). The Aṅguttara Nikāya (Vols. 1–5). London: Pali Text Society. |

| Av-klp | Das, S. C., and Vidyābhūṣaṇa, Hari Mohan (Eds.). (1887). Avadāna Kalpalatā with its Tibetan version (Bibliotheca Indica; Collection of Oriental Works). Culcutta: Baptist Mission Press. |

| Avś | Speyer, J. S. (Ed.). (1958 [1902–1909]). Avadānaçataka: A Century of Edifying Tales Belonging to the Hīnayāna. The Hague: Mouton & Co. |

| BHSD | Edgerton, Franklin. (1953). Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit Grammar and Dictionary, vol. 2: Dictionary. New Haven: Yale University Press. |

| cf. | Confer |

| Dhp | von Hinüber, Oskar, and Norman, K. R. (Eds.). (1995). Dhammapada with a complete Word Index compiled by Shoko Tabata and Tetsuya Tabata. Oxford: Pali Text Society. |

| Dhp-a | Norman, H. C. (Ed.). (1906–1914). Dhammapadaṭṭhakathā (Vols. 1–5). London: Pali Text Society. |

| Divy | Cowell, E. B., and Neil, Robert A. (Eds). (1987). The Divyāvadāna: A Collection of Early Buddhist Legends now first edited from the Nepalese Sanskrit Mss. in Cambridge and Paris. Delhi: Indological Book House. |

| DN | Rhys Davids, T. W., and Carpenter, Joseph E. (Eds). (1890–1911). The Dīgha Nikāya (Vols. 1–3). London: Pali Text Society. |

| DPPN | Malalasekera, G. P. (1937–1938). Dictionary of Pāli Proper Names (Vols. 1–2). London: J. Murray. |

| Fig. | Figure (pl. Figs.) |

| GM | Dutt, Nalinaksha (Ed.). (1939–1959). Gilgit Manuscripts (Vols. 1–4). Srinagar: Calcutta Oriental Press. |

| It | Windisch, Ernst (Ed.). (1889). Itivuttaka. London: Pali Text Society. |

| Ja | Fausbøll, M. V. (Ed). (1877–1896). Jātaka, together with its Commentary being tales of the anterior births of Gotama Buddha (Vols. 1–7). London: Trübner and Co. |

| Kv | Taylor, A.C. (Ed.). (1894–1897). Kathāvatthu. London: Pali Text Society. |

| LV | Vaidya, Paraśurama L. (Ed.). (1958). Lalitavistara. Darbhanga: Mithila Institute. |

| Mil | Trenckner, V. (Ed.). (1997 [1880]). The Milindapañho: Being Dialogues Between King Milinda and the Buddhist Sage Nāgasena. Oxford: Pali Text Society. |

| MPrS | the Gilgit manuscript of the Mahāprātihāryasūtra; Ed. and transl. in Sirisawad 2019 |

| Mp-ṭ | Sāriputta. (1961). Sāratthamañjūsā [Manorathapūraṇī-ṭīkā] (Vols. 1–3). Rankun. |

| MSV | the Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya |

| MSV-C | The parallel versions of the Mahāpratihāryasūtra from the Chinese Translation of the Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya (Gēnbĕn shuōyíqièyŏubù Pínàiyē Záshì 根本說一切有部毘奈耶雜事 (translated by Yijing 義淨, 710 CE), T. 1451 vol. 24, 207a–414b. |

| MSV-T | The parallel versions of the Mahāpratihāryasūtra from the Tibetan Translation of the Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya (’Dul ba phran tshegs kyi gzhi) (translated by Vidyākaraprabha, Dharmaśrīprabha and dPal ’byor, 9th century CE); Ed. and transl. in Sirisawad 2019 |

| Mvu | Senart, Émile. (Ed.). (1882–1897). Le Mahâvastu: Texte Sanscrit publié pour la premiere fois et accompagné d’introductions et d’un commentaire (Vols. 1–3). Paris: Imprimerie nationale. |

| Mvy | Ishihama, Y, and Fukuda, Y. (1989). A New Critical Edition of the Mahāvyutpatti. Studia Tibetica 16. |

| MW | Monier-Williams, M. (2002 [1872]). A Sanskrit-English Dictionary. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. |

| p. | page (pl. pp.) |

| Paṭis | Taylor, A. C. (Ed.). (1905–1907). Paṭisambhidāmagga (Vols. 1–2). London: Pali Text Society. |

| PrS(Divy) | the Prātihāryasūtra of the Divyāvadāna, ed. E. B.Cowell and R. A. Neil → Divy. |

| Ps-pṭ | Dhammapāla. Līnatthapakāsinī II. Papañcasūdanī-purāṇaṭīkā. |

| PTSD | Rhys Davids, T. W., and Stede, W. (Ed.). (1921–1925). The Pali Text Society’s Pali-English Dictionary. London |

| Q | Peking xylograph Kanjur-Tanjur, Qianlong edition |

| Skt. | Sanskrit |

| SN | Feer, L. (Ed.). (1884–1898). The Saṃyutta-Nikāya. London: Pali Text Society. |

| Spk-pṭ | Dhammapāla. Sāratthapakāsinī-purāṇatīkā. Līnatthapakāsinī III. |

| Sv | Rhys Davids, T. W., Carpenter J. Estlin and Stede, W. (Eds.). (1886–1932). Sumaṅgalavilāsinī, Buddhaghosa’s Commentary on the Dīghanikāya (Vols. 1–3).London: Pali Text Society. |

| Sv-pṭ | Dhammapāla. (1970). Sumaṅgalavilāsinīpurāṇaṭīkā. Līnatthapakāsinī I, edited by Lily de Silva. (Vols. 1-3). London: Pali Text Society. |

| SWTF | Bechert, Heinz. (Ed.). (1973). Sanskrit-Wörterbuch der buddhistischen Texte aus den Turfan-Funden, Begonnen von Ernst Waldschmidt. Göttingen. |

| T. | Junjirō Takakusu 高楠順次郎, Kaigyoku Watanabe 渡邊海旭, and Genmyō Ono 小野玄妙. (Eds.). (1924–1932). Taishō shinshū Daizōkyō 大正新修大藏經 [Taishō Edition Tripiṭaka]. 100 vols. Tokyo: Taishō Issaikyō Kankōkai. Online version available in: CBETA (Chinese Buddhist Electronic Text Association), http://www.cbeta.org/. |

| Th | Oldenberg, Hermann, and Pischel, Richard. (Eds.). (1883). Theragāthā. London: Pali Text Society. |

| Tib. | Tibetan language |

| Transl. | Translation |

| Upāyikā-ṭīkā | Śamathadeva’s the Abhidharmakośopāyikā-ṭīkā (Chos mngon pa’i mdzod kyi ’grel bshad nye bar mkho ba zhes bya ba); Ed. and transl. in Sirisawad 2019 |

| Uv | Bernhard, Franz. (Ed.). (1965–1968). Udānavarga. Abhandlungen der Akademie der Wissenschaften in Gottingen, philologisch-historische Klasse, dritte Folge, Nr. 54 / Sanskrittexte aus den Turfanfunden, X. Gottingen: Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht. |

| UvViv | Balk, Michael. (1984). Prajñāvarman’s Udānavargavivaraṇa (Vols. 1–2). Bonn. |

| Vin | Oldenberg, Hermann. (Ed.). (1879–1883). Vinayapiṭaka. (Vols. 1–5). London: Pali Text Society. |

| 1 | For the edition of the text, see (Sirisawad 2019, pp. 17–51, 192–198). |

| 2 | For the edition of the text, see (Falk and Steinbrückner 2020, pp. 3–42). |

| 3 | The Chinese retains a version slightly different from the Tibetan in this fifth duty: “The fifth is to deliver all living beings who have received teachings only from the Buddha toward emancipation” (五者但是因佛受化衆生悉皆度脱) (Rhi 1991, p. 273). |

| 4 | There are two lists of five essential deeds found in T. 125 [a] 622c12–15 (Bareau 1995, p. 200) and T. 125 [b] 703b17–20 (Rhi 1991, p. 21, note 36) and see the discussion in (Rhi 1991, p. 21, note 36). |

| 5 | Bhaiṣajyavastu: Gilgit version (199v1: GM iii 1, 162.17; Clarke 2014, p. 90); the Tibetan version (Q1030, vol. 41, 260b4). For the Tibetan text and French translation see (Hofinger 1982, vol. 1, pp. 7–8) (Introduction), p. 33 (Text), pp. 175–77 (Transl.) |

| 6 | The characteristic of the iddhipāṭihāriya is explained in the Paṭisambhidāmagga (i 111). |

| 7 | For an analysis of these various terms, see (Fiordalis 2008, p. 47ff). |

| 8 | The verb, paṭi+√hṛ, is found in Pāli texts in the sense of striking in return or against, while the form, paṭi+ā+√hṛ, is used more in the sense of taking away. See PTSD entries under paṭiharati, paccāharati and harati. |

| 9 | The same explanation is at Ps-pṭ i 24, Spk-pṭ i 21, and Mp-ṭ i 24. |

| 10 | The same explanation is found in DN iii 3; SN iv 290; AN i 170, v 327; Paṭis ii 227. The Sanskrit reads: trīṇi prātihāryāṇi ṛddhiprātihāryam ādeśanāprātihāryam anuśāsanīprātihāryam, see BHSD 392; SWTF III 229–230; Mvy 232–234; Mvu i 238, iii 137 (dharmadeśanā-instead of ādesanā-pāṭihāriyaṃ). |

| 11 | Cf. the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya (T. 1428: 797a) and the Dirghāgama (T. 1: 9c–10a, 101c–102a). |

| 12 | These miracles are commonly retained in the literature of several sects, such as the Theravāda, (Mūla)Sarvāstivāda, and Mahāsāṅghika, only with slight differences in phrasing, see (Rhi 1991, p. 30, note 62). For the Theravādins, it corresponds to the three kinds of “wonders” in the Blessed One’s teaching, which are mentioned in various texts of the Pāli canon, such as the stories of the conversion of the Kāśyapa brothers at Urubilvā, as it appears in the Mahāvagga of the Pāli Vinaya, and in the Vinayas of other early Buddhist schools, see (Fiordalis 2008, pp. 73–86). |

| 13 | Apart from the above occurrences in the versions of the Mūlasarvāstivādins, they also appear in the Sahasodgatāvadāna (Divyāvadāna no. 21), the Rudrāyaṇāvadāna (Divyāvadāna no. 37), Saṅghabhedavastu of the Vinayavastu, the Prātimokṣasūtra, the Mūlasarvāstivāda monastic code (see Skilling 1999a, pp. 441, 444, notes 8–10), and the Kapphināvadāna of the Avadānaśataka no. 88 (Avś ii 105). Dealing with heedfulness, these verses are included in a great collection of verses, the Udānavarga, which is roughly comparable to the Theravādin Dhammapada and Udāna combined, in the “Chapter on Heedfulness” (Apramādavarga) (Uv iv 37–38). The two verses occur three times in the Pāli canon (see Skilling 1999a, pp. 442, 444, notes 11–12), in the Aruṇavatisutta (Sagāthavagga, Saṃyuttanikāya) (SN i 155–157), Abhibhūtatheragāthā (Tikanipāta, Theragāthā verses 255–257) (Th 31), and Kathāvatthu (Kv 203). Sometimes either the first or second occurs alone. The second part of the verse occurs in the Mahāparinibbānasutta (DN ii 121), and the first part occurs in the Milindapañha (Mil 244–245). Moreover, the verses exist in the Nibbānasutta (see Hallisey 1993, pp. 97–130), an allegedly non-canonical sutta of the Theravadin corpus whose Pāli witness probably derives from Southeast Asia. The verses occur in the literature of other schools also. They are included in the “Chapter on Heedfulness” (Apramāda) in the “Gāndhāri Dharmapada”, which belongs to the Dharmaguptaka school (see Skilling 1999a, p. 441), in Chapter 22 of the Book of Zambasta, an early work in Khotanese, and in the Mahāsamājasūtra (Chinese Dīrghāgama, Sūtra 19), which belongs to the Dharmaguptaka school (See Waldschmidt [1932] 1979, p. 194; Ichimura 2016, p. 139). They are cited by Bhavya, who was a leading exponent of the Madhyamaka (ca. 500–570 CE), in Chapter 3 of his Madhyamakaratnapradīpa, (see Skilling 1999a, pp. 442–43, 444, notes 13–17), in the Bhadrapālaśreṣṭiparipṛcchā (Tshong dpon bzang skyong gis shus pa, no. 39) of the Mahāratnakūṭa collection (Q 760, vol. 24, ’i 73b3–4). The ārabhadhvaṃ niṣkrāmata verses are engraved on a votive inscription at Nālandā dated to the reign of Mahendrapāladeva, a famous Pāla king of the late 9th century CE., wherein they are themselves described as a “caitya of the Blessed One, the Sugata (see Sastri 1999, pp. 106–107). In the Tibetan tradition the verses are inscribed in monastery vestibules or on cloth-paintings (thangka) depicting the “wheel of life” (Bhavacakra) or the Buddha (Ajanta cave 17 has a depiction of the Saṃsāracakra, see (Schlingloff 2013, vol. 3: XVII, 20)). The verses are instructive examples, and they are put to difference purposes in different written and visual media. |

| 14 | These verses are included in the Yugavarga of the Udānavarga (Uv xxix 1–2) and the Jaccandhavagga in the Pāli Udāna (Ud vi 10). |

| 15 | See also (Skilling 1997, vol. 1, pp. 306–8, vol. 2, pp. 464–67). Furthermore, neither the Sanskrit Dhvajāgra-sūtra from Central Asia nor the Chinese versions include the verses (Skilling 1991, p. 240). |

| 16 | |

| 17 | |

| 18 | The four stages of penetrating insight (nirvedhabhāgīya) are the four stages on the path of application (prayogamārga): heat (uṣmagata), tolerance (kṣānti), summit (mūrdha), and the highest worldly dharma (laukikāgradharma). The first three are themselves sub-divided into three degrees—weak, medium, and strong—hence there are ten stages in all. (Rotman 2008, p. 452). |

| 19 | A following episode concerns Upatissa (Sāriputta) and Kolita (Mogallāna), two young Brahmins and pupils of the recently deceased Sañjaya, who became the guardians of the group [of followers of Sañjaya], the managers of the group. One day Upatissa encountered the Buddha’s disciple Assaji, who was out for alms. Upatissa, impressed by the Assaji’s deportment, asked him, ‘Who, O monk, is your teacher, or: under whose guidance did you enter the religious life, or: whose dharma do you declare?” Assaji answered that ‘the ascetic Gautama, a son of the Śakyas, … is my teacher. Under his guidance I entered the religious life. I declare his dharma.’ This leads to the conversion of not only both Upatissa and his companion Kolita but also of their followers (Vin i 39ff). |

| 20 | |

| 21 | A double pa and a subscript ra seem to appear, even though the reading on the tablets is rather obscure, making the compound -ppra in hetupprabhavā clear. |

| 22 | |

| 23 | See the list of Buddha images, miniature tablets or shrines, or the sponsorship of Buddhist buildings in (Revire 2014, pp. 250–52, table 2). |

| 24 | Giving (dāna) is one of the essential preliminary steps of Buddhist practice. The act of giving is also emphasised in ancient Buddhist stories and tales such as Jātakas and Avādanas. It is the supreme virtue perfected by all Bodhisattvas in their long path toward perfection (pāramitā) and the perfect self-enlightenment (sammāsambodhi) (Revire 2014, p. 243). Naturally, the average layperson is not expected to make so great a sacrifice as Bodhisattvas did. For most people, the practice of dāna is limited to material support in order to make merit. |

| 25 | Bauer (1991, p. 42) gives another transliteration as “nai vo’ puṇya kamrateṅ pdai karom’ or skuṁ das jāti smar”. He also argues that the term nai for “this” may be a variant of a similar Khmer word which would suggest contact with Khmer populations in this region. |

| 26 | There are variant spellings of this word such as puñ, piñ, pinna, puṇya, or puṇa. A few significant examples are given in (Revire 2014, pp. 244–47). |

| 27 | Several Mon inscriptions mention communal merit making by the assembled elite, the middle-class people and the general populace, see the (The Fine Arts Department 1986 [2529 BE], vol. 2, pp. 60–66, 71, 81, 103; Dhamrungrueng 2015 [2558 BE], pp. 84–89). |

| 28 | Ānisaṃsa can mean both a promise of benefit and reward and the benefits and reward themselves. For further discussion on the range of the term, see (Skilling 2017, pp. 5–6). |

| 29 | Viriyapaṇḍitajātaka, in Paññāsa-Jātaka Jaini (1983, vol. 1, No. 25, pp. 297–308); (Jaini 1986, vol. 1, pp. 306–16). The verses use the terms Buddha-bimba, Buddha-paṭimā, and Buddha-rūpa. For other examples of benefits from making Buddha images, see (Skilling 2017, pp. 26–28). |

References

- Bareau, André. 1995. Recherches sur la biographie du Buddha dans les Sūṭrapitaka et les Vinayapiṭaka anciens, Vol. 3. Paris: École française d’Extrême-Orient. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, Christian. 1991. Notes on Mon Epigraphy. Journal of the Siam Society 79: 31–83. [Google Scholar]

- Bhumadhon, Phuthorn, and Bancha Phongpanit. 2015 [2558 BE]. อู่ทองที่รอการฟื้นคืน: ผ่านรอยลูกปัดและพระพุทธศาสนาแรกเริ่มในลุ่มแม่น้ำแม่กลอง-ท่าจีน [U-Thong Waiting to be Revived: Through Beads and Early Buddhism in the Mae Klong-Tha Chin River Basin]. Bangkok: Designated Areas for Sustainable Tourism, Buddhadasa Indapanno Archives Foundation. (In Thai) [Google Scholar]

- Black, Deborah, trans. 1997. Leaves of the Heaven Tree: The Great Compassion of the Buddha. Berkeley: Dharma Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Bodhi, Bhikkhu, trans. 2017. The Suttanipata: An Ancient Collection of the Buddha’s Discourses Together with Its Commentaries (The Teachings of the Buddha). Boston: Wisdom. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Robert L. 1984. The Śrāvastī Miracles in the Art of India and Dvāravatī. Archives of Asian Art 37: 79–95. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Robert L. 1996. The Dvāravatī Wheels of the Law and the Indianization of South East Asia. Leiden, New York and Köln: E.J. Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Robert L. 2011. A Sky-Lecture by the Buddha. Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association 31: 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Buddha Monthon Construction Administration Committee. 1988. Buddha Monthon: In Honour of His Majesty King Bhumibol Adulyadej the Great. Bangkok: Victory Power Point. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, Shayne. 2014. Gilgit Manuscripts in the National Archives of India ckner Facsimile Edition Volume I Vinaya Texts. New Dehli: The National Archives of India. Tokyo: The International Research Institute for Advanced Buddhology at Soka University. [Google Scholar]

- Cœdès, George. 1926. Siamese Votive tablets. Journal of the Siam Society 20: 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Cowell, Edward Byles, ed. 1990. The Jātaka, or Stories of the Buddha’s Former Births, Vol. 4. London: Pali Text Society. [Google Scholar]

- De Notariis, Bryan. 2019. The Vedic Background of the Buddhist Notions of Iddhi and Abhiññā. Three Case Studies with Particular Reference to the Pāli Literature. Annali di Ca’ Foscari. Serie orientale 55: 227–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degener, Almut. 1990. Das Kaṭhināvadāna (Indica et Tibetica 16). Bonn: Indica et Tibetica Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Dhamrungrueng, Rungrote. 2015 [2558 BE]. ทวารวดีในอีสาน [Dvāravatī in Isan]. Bangkok: Matichon. (In Thai) [Google Scholar]

- Falk, Harry, and Elisabeth Steinbrückner. 2020. A metrical version from Gandhāra of the “Miracle at Śrāvastī”. (Texts from the Split Collection 4). In Annual Report of the International Research Institute for Advanced Buddhology (ARIRIAB) at Soka University for the Academic Year 2029. Edited by Noriyuki Kudo. Tokyo: The International Research Institute for Advanced Buddhology, vol. 23, pp. 3–42. [Google Scholar]

- Feer, Léon, trans. 1883. Fragments Extraits du Kandjour. Annales du Musée Guimet V. Paris: Ernest Leroux. [Google Scholar]

- Fiordalis, David V. 2008. Miracles and Superhuman Powers in South Asian Buddhist Literature. Doctoral dissertation, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Fiordalis, David V. 2014. The Buddha’s Great Miracle at Śrāvastī: A Translation from the Tibetan Mūlasarvāstivāda-vinaya. Asian Literature and Translation 2: 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gethin, Rupert. 2011. Tales of Miraculous Teachings: Miracles in early Buddhism. In The Cambridge Companion to Miracles. Edited by Graham H. Twelftree. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 216–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, Suchandra. 2014. Viewing our Shared Past through Buddhist Votive Tablets across Eastern India, Bangladesh and Peninsular Thailand. In Asian Encounters, Exploring Connected Histories. Edited by Upinder Singh and Parul Pandya Dhar. Delhi: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, Suchandra. 2017. Buddhist Moulded Clay Tablets from Dvaravatī: Understanding Their Regional Variations and Indian Linkages. In India–Thailand Cultural Interactions. Edited by Lipi Ghosh. Singapore: Springer Nature, pp. 35–51. [Google Scholar]

- Glover, Ian C. 2017. The Pre-Dvāravatī Gap. In Defining Dvāravatī—Essays from the U Thong International Workshop 2017. Edited by Anna Bennett and Hunter Watson. Bangkok: Silkworm Books, pp. 15–23. [Google Scholar]

- Hallisey, Charles. 1993. Nibbānasutta: An allegedly non-canonical sutta on Nibbāna as a Great City. Journal of the Pali Text Society 18: 97–130. [Google Scholar]

- Hirakawa, Akira. 1973–1978. Index to the Abhidharmakósabhāṣya. Tokyo: Daizo Shuppan Kabushikikaisha, vol. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Hofinger, Marcel. 1982. Le Congrès du Lac Anavatapta (Vies de Saints Bouddhiques), Extrait du Vinaya des Mūlasarvātivādin Bhaiṣajyavastu, vol. 1: Légendes des Anciens (Sthavirāvadāna). Louvain-la-Neuve: Institut Orientaliste de Louvain. [Google Scholar]

- Horner, Isaline Blew, trans. 1951. The Book of the Discipline (Vinaya-Piṭaka), Vol. 4 (Mahāvagga). London: Pali Text Society and Luzac & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Ichimura, Shohei, trans. 2016. The Canonical Book of the Buddha’s Lengthy Discourses, Vol. 2 (Taisho Vol. 1 No. 1). Moraga: BDK America, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Jaini, Padmanabh S., ed. 1977. Abhidharmadīpa with Vibhāṣāprabhāvṛtti (Tibetan Sanskrit Works IV). Patna: Kashi Prasad Jayaswal Research Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Jaini, Padmanabh S., ed. 1983. Paññāsa-jātaka or Zimme Paṇṇāsa (in the Burmese Recension). London: The Pali Text Society, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Jaini, Padmanabh S., trans. 1986. Apocryphal Birth Stories. London: The Pali Text Society, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- La Vallée Poussin, Louis de, and Gelong Lodro Sangpo. 2012. Abhidharmakośa-Bhāṣya of Vasubandhu: The Treasury of the Abhidharma and Its (Auto) Commentar (Vols. 1–4). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. [Google Scholar]

- Lamotte, Étienne. 1958. Histoire du Bouddhisme Indien: Des Origines à l’Ère Śaka. Bibliothèque du Muséon 43. Louvain: Publications Universitaires, Institut Orientaliste. [Google Scholar]

- Lamotte, Étienne. 1988. History of Indian Buddhism: From the Origins to the Śaka Era. Translated by Sara Webb-Boin. Publications de l’Institut Orientaliste de Louvain 36. Louvain-la-Neuve: Institut Orientaliste de l’Université Catholique de Louvain. [Google Scholar]

- Ñāṇamoli, Bhikkhu, trans. 1982. The Path of Discrimination. (Paṭisambhidāmagga). (Translation Series, No. 43.). London: Pali Text Society. [Google Scholar]

- Revire, Nicolas. 2014. Glimpses of Buddhist Practices and Rituals in Dvāravatī and Its Neighbouring Cultures. In Before Siam Essay in Art and Archaeology. Edited by Nicolas Revire and Stephen A. Murphy. Bangkok: River Book and the Siam Society, pp. 240–71. [Google Scholar]

- Rhi, Ju-hyung. 1991. Gandharan Images of the “Śravasti Miracle”: An Iconographic Reassessment. Doctoral dissertation, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Rotman, Andy, trans. 2008. Divine Stories: Part 1. Boston: Wisdom. [Google Scholar]

- Saraya, Dhida. 1999. (Sri) Dvaravati: The Initial Phase of Siam’s History. Bangkok: Muang Boran Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Sastri, Hirananda. 1999. Memoirs of the Archaeological Survey of India No.66 Nalanda and its Epigraphic Material. New Delhi: The Director General Archaeological Survey of India. [Google Scholar]

- Schlingloff, Dieter. 1964. Ein buddhistisches Yogalehrbuch: Unveränderter Nachdruck der Ausgabe von 1964 unter Beigabe aller seither bekannt gewordenen Fragmente. Düsseldorf: Haus der Japanischen Kultur (EKO). [Google Scholar]

- Schlingloff, Dieter. 2013. Ajanta Handbook of the Paintings (Vols. 1–3). Translated by Miriam Higgin, and Peter Haesner. New Delhi: Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts and Aryan Books International. [Google Scholar]

- Schopen, Gregory. 2004. Buddhist Monks and Business Matters: Still More Papers on Monastic Buddhism in India. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, Sanghasen, ed. 1983. A Study of the Sphuṭārthā Śrīghanācārasaṅgrahaṭīkā (Tibetan Sanskrit Works Series XXIV), 2nd ed. Patna: Kāśī Prasād Jaysvāl Research Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Sirisawad, Natchapol. 2019. The Mahāprātihāryasūtra in the Gilgit Manuscripts: A Critical Edition, Translation and Textual Analysis. Doctoral dissertation, Ludwig Maximilians-Universität, München, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Sirisawad, Natchapol. 2022. The Śrāvastī Miracles: Some Relationships between their Literary Sources and Visual Representations in Dvāravatī. Entnagled Religions. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Skilling, Peter. 1991. A Buddhist Verse Inscription from Andhra Pradesh. Indo-Iranian Journal 34: 239–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skilling, Peter. 1997. Mahāsūtras: Great Discourses of the Buddha (Vols. 1–2). Oxford: Pali Text Society. [Google Scholar]

- Skilling, Peter. 1999a. Arise, go forth, devote yourselves…: A verse summary of the teaching of the Buddhas. In Socially Engaged Buddhism for the New Millennium Essays in Honor of The Ven. Phra Dhammapitaka (Bhikkhu P.A. Payutto) on His 60th Birthday Anniversary. Bangkok: Sathirakoses-Nagapradipa Foundation and Foundation for Children, pp. 440–44. [Google Scholar]

- Skilling, Peter. 1999b [2542 BE]. A Buddhist inscription from Go Xoai, Southern Vietnam and notes towards a classification of ye dharmā inscriptions. In 80 pi śāstrācāry dr. praḥsert ṇa nagara: Ruam pada khwam vijākāra dan charük lae ekasāraporāṇa [80 Years: A Collection of Articles on Epigraphy and Ancient Documents Published on the Occasion of the Celebration of the 80th Birthday of Prof. Dr. Prasert Na Nagara]. Bangkok: Phikhanet Printing Center, pp. 171–87. [Google Scholar]

- Skilling, Peter. 2003. Traces of the Dharma: Preliminary reports on some ye dhammā and ye dharmā inscriptions from Mainland South-East Asia. Bulletin de l’École française d’Extrême-Orient 90/91: 273–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skilling, Peter. 2008a. Buddhist Sealings in Thailand and Southeast Asia: Iconography, Function, and Ritual Context. In Interpreting Southeast Asia’s Past Monument, Image and Text. Edited by Elisabeth A. Bacus, Ian C. Glover, Peter D. Sharrock, John Guy and Vincent C. Pigott. Singapore: NUS Press, pp. 248–62. [Google Scholar]

- Skilling, Peter. 2008b. Buddhist Sealings and the Ye Dharmā stanza. In Archaeology of Early Historic South Asia. Edited by Gautam Sengupta and Sharmi Chakraborty. New Delhi: Pragati Publications, pp. 503–25. [Google Scholar]

- Skilling, Peter. 2009. Seeing the Preacher as the Teacher: A note on sāstrsamjñā. In Annual Report of the International Research Institute for Advanced Buddhology (ARIRIAB) at Soka University for the Academic Year 2008. Tokyo: The International Research Institute for Advanced Buddhology, vol. 12, pp. 73–100. [Google Scholar]

- Skilling, Peter. 2017. Ānisaṃsa: Merit, Motivation and Material Culture. Journal of Buddhist Studies 14: 1–56. [Google Scholar]

- Strong, John. 2013. “When Are Miracles Okay? The Story of Piṇḍola and the Kevaddha Sutta Revisited”. In Fojiao shenhua yanjiu: Wenben, tuxiang, chuanshuo yu lishi = Studies on Buddhist Myths: Texts, Pictures, Traditions and History. Edited by Bangwei Wang, Jinhua Chen and Ming Chen. Shanghai: Zhongxi Book Company, pp. 13–44. [Google Scholar]

- Takakusu, J. 1998. A Record of the Buddhist Religion as Practised in India and the Malay Archipelago (A.D. 671-695). Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal. [Google Scholar]

- The Fine Arts Department. 1986 [2529 BE]. จารึกในประเทศไทย [Inscriptions of Thailand] (Vols. 1–5). Bangkok: National Library of Thailand. (In Thai) [Google Scholar]

- Waldschmidt, Ernst. 1979. Bruchstücke buddhistischer Sūtras aus dem zentralasiatischen Sanskritkanon (Kleinere Sanskrit-Texte Heft IV). Wiesbaden: Franz Steiner Verlag. First published 1932. [Google Scholar]

| Avaśyakaraṇīya | MSV-T | MSV-C | Ekottarikāgama | Mvu | Vinaya vibhaṅga | Bhaiṣajyavastu | PrS (Divy) | Kaṭhināvadāna | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T. 125 [a] | T. 125 [b] | Gilgit | Tib | |||||||

| (i) To help sentient beings to engage in the search of ultimate awakening | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||

| (ii) To turn the wheel of dharma | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| (iii) To consecrate as heir apparent a disciple who has accumulated the roots of virtue | 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| (iv) To establish his mother and father in the truth | 3 | 3 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | |||

| (v) To preach the dharma to his parents | 2 | |||||||||

| (vi) To preach the dharma to his father | 2 | 3 | ||||||||

| (vii) To preach the dharma to his mother | 3 | 2 | ||||||||

| (viii) To display the Great Miracle at Śrāvastī | 4 | 4 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 10 | 7 | |||

| (ix) To convert all those who should be converted | 5 | 5 a | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | ||

| (x) To lead those people who do not have faith to the ground of faith | 3 | |||||||||

| (xi) To generate the aspiration for Bodhisattvahood | 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| (xii) To give a prediction to the Bodhisattva/ to prophesize a future Buddha. | 5 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| (xiii) To exceed the fifth part of his lifetime | 4 | 6 | 6 | |||||||

| (xiv) To exceed three-quarters of the duration of his existence. | 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| (xv) To draw a strict line of (moral) demarcation (between good and evil) b | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |||||

| (xvi) To appoint a pair of his disciples as the foremost of all | 6 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 4 | |||||

| (xvii) To display his descent from the heaven of the devas to the city of Sāṃkāśya | 7 | 8 | 8 | 7 c | 8 | |||||

| (xviii) To explain the sequence of his previous actions at the great lake Anavatapta. d | 9 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 10 | |||||

| PrS(Divy) 166.24–27 | Upāyikā-ṭīkā | Abhidharma-kośabhāṣya | Saṃskṛtāsaṃskṛta- viniścaya | Gāthāsaṃgraha |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) dhanyās te puruṣā loke ye buddhaṃ śaraṇaṃ gatāḥ | nirvṛtiṃ te gamiṣyanti buddhakārakṛtau16 janāḥ || | gang zhig ’jig rten sangs rgyas la || skyabs song skyes bu de mchog ste || sangs rgyas bya ba byas skye bo || mya ngan ’das par ’gro bar ’gyur || | |||

| (2) ye ’lpān api jine kārān kariṣyanti vināyake | vicitraṃ svargam āgamya te lapsyante ’mṛtaṃ padam || | gang zhig rgyal ba rnams ’dren la || bya ba cung zad byed gyur ba || de dag mtho ris sna tshogs dag || bgrod nas bdud rtsi go ’phang thob || | ye ’nyān17 api jine kārān kariṣyanti vināyake | vicitraṃ svargam āgamya te lapsyante ’mṛtaṃ padam || | gang zhig rgyal ba rnam ’dren la || mchod ba chung ba ’ang byed ’gyur ba || bde ’gro sna tshogs bgrod nas ni || bdud rtsi go ’phang thob par ’gyur || | gang ngag rgyal ba rnams ’dren la || byed pa chung ngu ’ang byed ’gyur ba || de dag mtho ris sna tshogs pa || bgrod na ’chi med gnas thob pa || |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sirisawad, N. Significance of the Śrāvastī Miracles According to Buddhist Texts and Dvāravatī Artefacts. Religions 2022, 13, 1201. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13121201

Sirisawad N. Significance of the Śrāvastī Miracles According to Buddhist Texts and Dvāravatī Artefacts. Religions. 2022; 13(12):1201. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13121201

Chicago/Turabian StyleSirisawad, Natchapol. 2022. "Significance of the Śrāvastī Miracles According to Buddhist Texts and Dvāravatī Artefacts" Religions 13, no. 12: 1201. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13121201

APA StyleSirisawad, N. (2022). Significance of the Śrāvastī Miracles According to Buddhist Texts and Dvāravatī Artefacts. Religions, 13(12), 1201. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13121201