Patriotism as a Political Religion: Its History, Its Ambiguities, and the Case of Hungary

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Political Religion: The Origins

“The emergence of the state (…) has to do with the detachment of the political order as such from its spiritual and religious origin and evolution; with its ‘becoming secular’ in the sense of exiting a world in which religion and politics formed a unity to find a purpose and identity of its own, conceived in secular (political) terms; and, finally, with the separation of the political order from the Christian religion and from any specific religion as its foundation and leaven”.

3. The French Revolution

“It has been said that the teaching of the constitution of each country should be part of national education. This is true, no doubt, if we speak of it as a fact; if we content ourselves with explaining it; if, in teaching it, we confine ourselves to saying: Such is the constitution established in the State to which all citizens must submit. But if we say that it must be taught as a doctrine in line with the principles of universal reason or arouse in its favor a blind enthusiasm which renders citizens incapable of judging it; if we say to them: This is what you must worship and believe; then it is a kind of political religion that we want to create. It is a chain that we prepare for the spirits, and we violate freedom in its most sacred rights, under the pretext of learning to cherish it”.

“Around the altar of the fatherland was a circle of soldiers, around it a circle of notables. Around it were the people: they attended as the oath was taken by the first two groups and sometimes were bold enough to demand that they themselves should take an oath. Nevertheless, they had to demand it”.

“All we can do is fight for the government, whatever it may be; for in this way France, despite her internal discord, will preserve her military strength and her influence abroad. Taking things at their best, it is not for the government that we are fighting, but for France (…) The revolutionary government hardened the soul of France by tempering it in blood; the spirit of the soldiers was exasperated, and their strength was doubled by ferocious despair and contempt for life induced by rage”.

4. Europe in the 19th Century

“Humanity cannot live without heaven. You can guide them to truth out of materialism. To do this, you must unite Italy and abhor being a king or politician. To unite Italy you have no need to do, only to bless. Let the pen go free. Throw the Austrians out of Italy (…) Bless the national flag—and leave the rest to us” (p. 72).

“When there was revolution over Europe, I sent troops to guard the frontiers. But when some demanded that these troops join with other states to war against Austria, I must say solemnly, that I abhor the idea. I am the Vicar of Christ, the author of peace and lover of charity, and my office is to bestow an equal affection on all nations. I repudiate all the newspaper articles that want the pope to be president of a new republic of all the Italians” (p. 77).

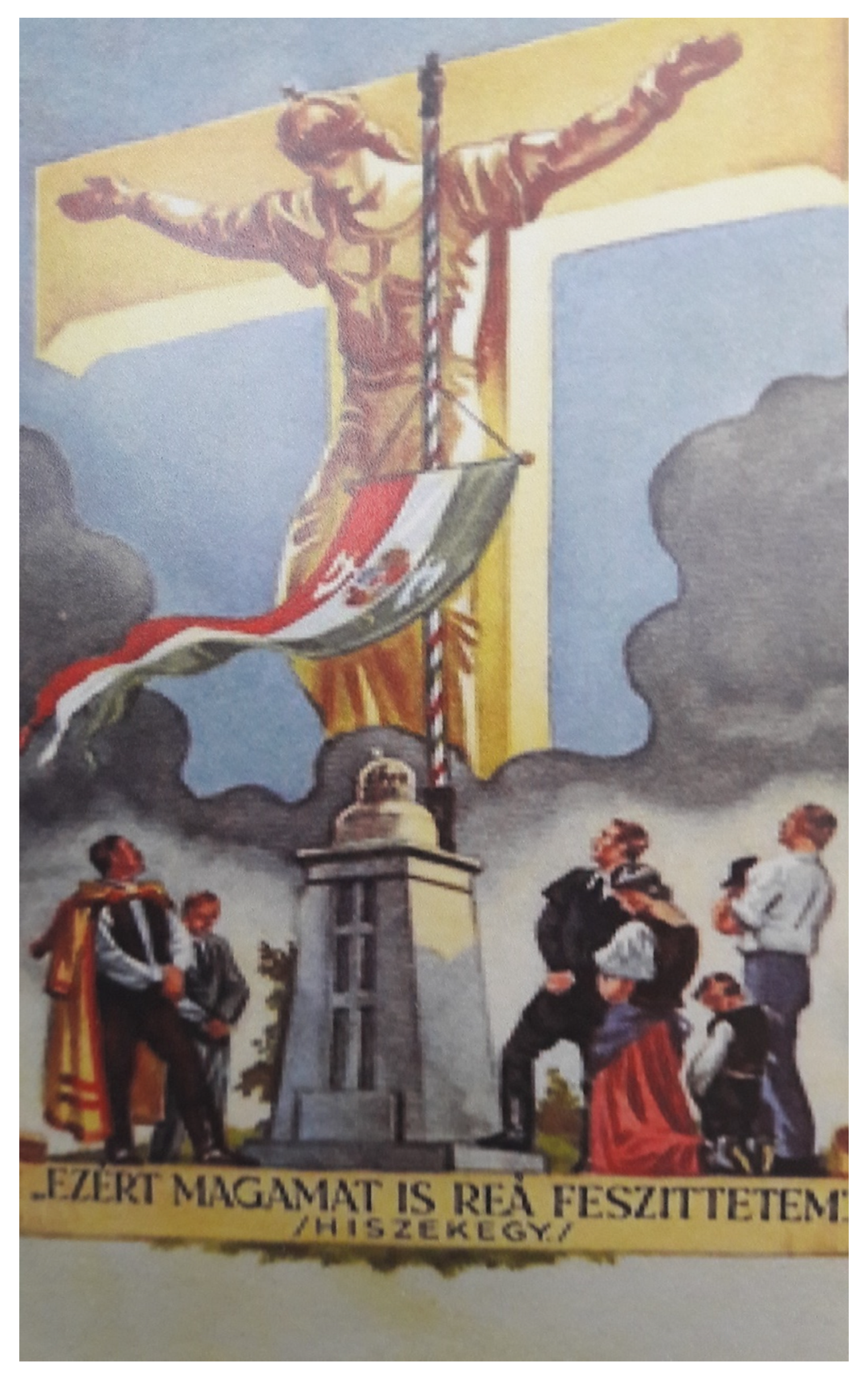

5. Patriotic Religion in Hungary

5.1. The Classics

5.2. The Short 20th Century

5.3. Contemporary Politics

“The new state that we are constructing in Hungary is an illiberal state, a non-liberal state. It does not reject the fundamental principles of liberalism such as freedom, and I could list a few more, but it does not make this ideology the central element of state organization, but instead includes a different, special, national approach”.

“Let us confidently declare that Christian democracy is not liberal. Liberal democracy is liberal, while Christian democracy is, by definition, not liberal: it is, if you like, illiberal. And we can specifically say this in connection with a few important issues—say, three great issues. Liberal democracy is in favor of multiculturalism, while Christian democracy gives priority to Christian culture; this is an illiberal concept. Liberal democracy is pro-immigration, while Christian democracy is anti-immigration; this is again a genuinely illiberal concept. And liberal democracy sides with adaptable family models, while Christian democracy rests on the foundations of the Christian family model; once more, this is an illiberal concept”.(Orbán 2018a).

“We fended off the attack of Western empires one after the other. We recovered from the devastating blows of the Eastern pagans. We did what the other peoples of the steppe could not. We fought, we organized, we adapted, and we kept our place in Europe. For four hundred years, the time equivalent of four Trianons, Hungary was a strong and independent state”.

“Then for three hundred years, for three Trianons, we fought against the Ottoman Empire. Deep down, on the Balkans, then at our southern ends, and finally in the heart of the Carpathian Basin. And although Buda was in Turkish hands for a time of one and a half Trianons, they could not march through us”.

“Then, after two hundred years, two Trianons of failed uprisings and freedom fights, we entered the gate of the twentieth century as a partner nation of a great European empire”.

“We can hope that our generation, the fourth generation after Trianon can fulfill our mission and take Hungary all the way to the gates of victory. But the decisive battle must be fought by the generation following us, the fifth generation after Trianon. They must take the final steps. As it is written: ‘Gather your strength/And first of all/Start with the simplest thing/Come together/To grow in a tremendous way/To somehow approach God, who is infinite’”.

6. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anderson, Benedict. 1991. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Aron, Raymond. 1944. L’avenir des religions séculieres. La France Libre 45–46: 210–17; 269–77. [Google Scholar]

- Asad, Talal. 1993. Genealogies of Religion: Discipline and Reasons of Power in Christianity and Islam. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Backhouse, Stephen. 2020. Patriotism as Religion. In Handbook of Patriotism. Edited by Mitja Sardoč. Cham: Springer, pp. 856–71. [Google Scholar]

- Barry, Gearóid. 2015. Political Religion: A User’s Guide. Contemporary European History 4: 623–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beik, Paul H. 1970. The French Revolution: Selected Documents. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, David A. 2003. The Cult of the Nation in France: Inventing Nationalism, 1680–1800. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bellah, Robert. 1967. Civil Religion in America. Dædalus, Journal of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 96: 1–21. Available online: http://www.robertbellah.com/articles_5.htm (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Béres, Merse Máté. 2021. Az ötödik trianoni nemzedék. Keszthely: Balaton Akadémia. [Google Scholar]

- Böckenförde, Ernst-Wolfgang. 2020. The Rise of the State as a Process of Secularization [1967]. In Religion, Law, and Society: Selected Writings. Edited by Mirjam Künkler and Tine Stein. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 152–67. First published 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Bonald, Louis-Ambroise de. 1843. Oeuvres. Paris: Adrien le clére et c., vol. 15. First published 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Bossy, John. 1987. Christianity in the West 1400–1700. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cavanaugh, William T. 2009. The Myth of Religious Violence. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cavanaugh, William T. 2011. Migrations of the Holy: God, State, and the Political Meaning of the Church. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [Google Scholar]

- Chadwick, Owen. 1998. A History of the Popes 1830–1914. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, Janet. 2000. A History of Political Thought: From the Middle Ages to the Renaissance. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Condorcet, Jean-Antoine-Nicolas de Caritat. 1989. Cinq mémoires sur l’instruction publique. In Écrits sur l’instruction publique. Paris: Edilig, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Dugonics, András. 1904. Etelka Karjelben. Pozsony: Stampfel. First published 1794. Available online: https://mek.oszk.hu/08000/08051/08051.htm (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Dugonics, András. 1791. Etelka. Pozsony: Landerer. First published 1788. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald, Timothy. 2000. The Ideology of Religious Studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, Guy Stanton. 1935. Dictatorship in the Modern World. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gentile, Emilio. 2005. Political Religion: A Concept and Its Critics—A Critical Survey. Totalitarian Movements and Political Religions 1: 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoriadis, Ioannis N. 2013. Instilling Religion in Greek and Turkish Nationalism: A Sacred “Synthesis”. New York: Palgrave Pivot. [Google Scholar]

- Hermann, Róbert. 2006. Kossuth Lajos, a “magyarok Mózese”. Budapest: Osiris. [Google Scholar]

- Kantorowicz, Ernst. 1957. The King’s Two Bodies: A Study in Medieval Political Theology. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kitromilides, Paschalis M. 2019. Religion and Politics in the Orthodox World: The Ecumenical Patriarchate and the Challenge of Modernity. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Knapp, Éva, and Gábor Tüskés. 2002. Magyarország—Mária Országa: Egy történelmi toposz a XVIII. Századi egyházi irodalomban. Vigilia 2: 17–25. [Google Scholar]

- Kölcsey, Ferenc. 1823. Hymnus: A Magyar nép zivataros századaiból. Available online: http://www.mek.iif.hu/porta/szint/human/szepirod/magyar/kolcsey/anthem/html/ (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Körösényi, András, Illés Gábor, and Gyulai Attila. 2020. The Orbán Regime: Plebiscitary Leader Democracy in the Making. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kriza, Kálmán. 2021. Ha dalolni támad kedved: Daloskönyv. Budapest: Kairosz. Available online: http://mek.oszk.hu/05700/05702/html/dalok/dal-174.jpg (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Lamennais, Félicity de. 1836–1837. Paroles d’un croyant. In Oeuvres complètes de F. De La Mannais. Paris: Paul Daubrée et Cailleux, vol. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Löwith, Karl. 1949. Meaning in History: The Theological Implications of the Philosophy of History. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Maier, Hans. 2004. Concepts for the Comparison of Dictatorships: “Totalitarianism” and “Political Religions”. In Totalitarianism and Political Religions. Edited by Hans Maier. New York: Routledge, vol. 1, pp. 188–203. [Google Scholar]

- Maistre, Joseph de. 1994. Consideration on France. Translated by Richard A. Lebrun. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. First published 1797. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, Laura, and Tracy Rizzo. 1999. The French Revolution: A Document Collection. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzini, Giuseppe. 2009. Toward a Holy Alliance of the Peoples (1849). In A Cosmopolitanism of Nations: Giuseppe Mazzini’s Writings on Democracy, Nation Building, and International Relations. Edited by Stefano Recchia and Nadia Urbinati. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 117–31. [Google Scholar]

- McCalla, Arthur. 1998. A Romantic Historiosophy: The Philosophy of History of Pierre-Simon Ballanche. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Mickiewicz, Adam. 2016. Forefathers’ Eve. Translated by Charles S. Kraszewski. London: Glagoslav Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Mulsow, Martin. 2003. Mehrfachkonversion, politische Religion und Opportunismus im 17. Jahrhundert: Ein Plädoyer für eine Indifferentismusforschung. In Interkonfessionalität—Transkonfessionalität—Binnenkonfessionale Pluratität: Neue Forschungen zut Konfessionalisierungsthese. Edited by Kaspar von Greyerz, Manfred Jakubowski-Tiessen, Thomas Kaufmann and Hartmut Lehmann. Gütersloh: Gütersloher, pp. 132–50. [Google Scholar]

- Nathanson, Stephen. 1993. Patriotism, Morality, and Peace. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Nongbri, Brent. 2013. Before Religion: A History of a Modern Concept. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nyirkos, Tamás. 2021. The Proliferation of Secular Religions: Theoretical and Practical Aspects. Pro Publico Bono 2: 68–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orbán, Viktor. 2014. Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s Speech at the 25th Bálványos Summer Free University and Student Camp. Available online: https://2015-2019.kormany.hu/en/the-prime-minister/the-prime-minister-s-speeches/prime-minister-viktor-orban-s-speech-at-the-25th-balvanyos-summer-free-university-and-student-camp (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Orbán, Viktor. 2018a. Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s Speech at the 29th Bálványos Summer Open University and Student Camp. Available online: http://www.miniszterelnok.hu/prime-minister-viktor-orbans-speech-at-the-29th-balvanyos-summer-open-university-and-student-camp/ (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Orbán, Viktor. 2018b. Prime Minister Viktor Orbán on the Kossuth Radio programme “180 Minutes”. Available online: https://2015-2019.kormany.hu/en/the-prime-minister/the-prime-minister-s-speeches/prime-minister-viktor-orban-on-the-kossuth-radio-programme-180-minutes-20180507 (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Orbán, Viktor. 2020. Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s Commemoration Speech. Available online: http://www.miniszterelnok.hu/prime-minister-viktor-orbans-commemoration-speech/ (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Ozouf, Mona. 1988. Festival and the French Revolution. Translated by Alan Sheridan. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pohlsander, Hans A. 2008. National Monuments and Nationalism in 19th Century Germany. Bern: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Quaritsch, Helmut. 1986. Souveränität: Entstehung und Entwicklung des Begriffs in Frankreich und Deutschland vom 13. Jahrhundert bis 1806. Berlin: Duncker & Humblot. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, David D. 2009. “Political Religion” and the Totalitarian Departures of Inter-war Europe: On the Uses and Disadvantages of an Analytical Category. Contemporary European History 4: 381–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohe, Alice. 1922. Mussolini, Hope of Youth, Italy’s “Man of Tomorrow”. New York Times, November 5. [Google Scholar]

- Roudometof, Victor. 2019. Church, State, and Political Culture in Orthodox Christianity. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. Available online: https://oxfordre.com/politics/politics/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228637-e-743 (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Sand, George. 1839. Essai sur le drame fantastique: Goethe, Byron, Mickiewicz. Revue des Deux Mondes 4: 593–645. [Google Scholar]

- Schifirneţ, Constantin. 2013. Orthodoxy, Church, State, and National Identity in the Context of Tendential Modernity. Journal for the Study of Religions and Ideologies 34: 173–208. [Google Scholar]

- Seitschek, Hans Otto. 2007. Early Uses of the Concept ‘Political Religion’: Campanella, Clasen and Wieland. In Totalitarianism and Political Religions. Edited by Hans Maier. London: Routledge, vol. 3, pp. 103–13. [Google Scholar]

- Severino, Valerio. 2017. Reconfiguring Nationalism: The Roll Call of the Fallen Soldiers (1800–2001). Journal of Religion in Europe 10: 16–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severino, Valerio. 2021. Civil and Purely Civil in Early Unified Italy: The National Festival from a Juridical Standpoint. Pro Publico Bono 2: 26–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Jonathan Z. 1998. Religion, Religions, Religious. Critical Terms for Religious Studies. Edited by Mark C. Taylor. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, pp. 269–84. [Google Scholar]

- Voegelin, Eric. 1952. The New Science of Politics: An Introduction. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Voigt, Friedemann. 2009. Politische Religion. In Enzyklopädie der Neuzeit. Edited by Friedrich Jaeger. Stuttgart: J. B. Metzler, vol. 10, pp. 152–54. [Google Scholar]

- Vonyó, József. 2002. A Magyar Hiszekegy születése. História 1: 18–19. [Google Scholar]

- Webb, Mark Owen. 2009. An Eliminativist Theory of Religion. Sophia 48: 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nyirkos, T. Patriotism as a Political Religion: Its History, Its Ambiguities, and the Case of Hungary. Religions 2023, 14, 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14010116

Nyirkos T. Patriotism as a Political Religion: Its History, Its Ambiguities, and the Case of Hungary. Religions. 2023; 14(1):116. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14010116

Chicago/Turabian StyleNyirkos, Tamás. 2023. "Patriotism as a Political Religion: Its History, Its Ambiguities, and the Case of Hungary" Religions 14, no. 1: 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14010116

APA StyleNyirkos, T. (2023). Patriotism as a Political Religion: Its History, Its Ambiguities, and the Case of Hungary. Religions, 14(1), 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14010116