Abstract

The European Enlightenment witnessed a Jewish reclamation of Jesus. It led modernist Yiddish intellectuals to experiment with Christian motifs as they tried to contend with what it meant to be Jewish in the modern world. This article proposes to examine, with special focus on poetry, how the crucified Jesus not only became a space of hybridity for Yiddish literary artists to formulate modern Jewish identity and culture but also the medium through which to articulate Jewish suffering in a language that resonated with the oppressors. By doing so, the article seeks to understand the relevance that such literary depictions of Jesus by Jewish authors and poets can have for the Christian understanding of its own identity and its relationship with Judaism.

Keywords:

Jesus; Yiddish literature; cross; Jewish–Christian dialogue; Judaism; Christianity; modernism; Yiddish 1. Introduction

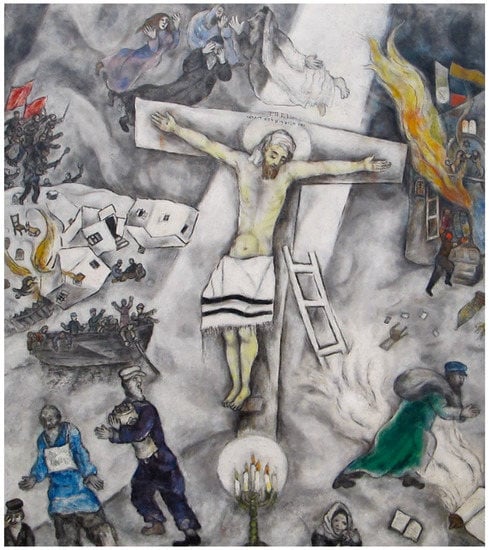

In 2015, the White Crucifixion (Figure 1), perhaps the most iconic of Jewish artist Marc Chagall’s paintings, travelled from the Art Institute of Chicago, where it is housed, to Florence for an encounter with Pope Francis. This, the Pope’s favourite work of art, depicts a crucified Jesus wearing a headcloth in place of the crown of thorns and a fringed piece of garment resembling the Jewish prayer shawl for a loincloth. Underneath the traditional INRI (Latin. Iesus Nazarenus, Rex Iudaeorum translated as Jesus the Nazarene, King of the Jews or rather Judeans) above Jesus’ head, Chagall, in keeping with John 19:20, gives its Aramaic translation in Hebrew letters: Yeshu HaNotzri, Malcha D’Yehudai. By using the term Ha-Notzri, used more often to mean “the Christian” rather “the Nazarene” or “the man from Nazareth” (Amishai-Maisels 1991), Chagall emphasised the importance of this obviously Jewish figure to both Jews and Christians. Moreover, through the halo around Jesus’ head as well as around the menorah at his feet, Chagall points to the holiness and validity of both the Jewish and Christian faith traditions. At the top of the painting float three biblical patriarchs and a matriarch lamenting Jesus’ death, an affirmation of Jesus’ place of honour within Jewish history. Around the crucified Jesus, Chagall, who painted the White Crucifixion in response to the Kristallnacht (the Night of the Broken Glass) in 1938 when Jewish establishments and synagogues across Nazi Germany were systematically targeted, depicted violent scenes of contemporary Jewish persecution—pogroms, pillaged villages, fleeing villagers, and a synagogue with its Torah ark aflame—thus joining Jewish suffering with that of Jesus.

Figure 1.

Marc Chagall, White Crucifixion, 1938. The Art Institute of Chicago. © 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris, also made available under Creative Commons Zero (CC0). Image courtesy Ed Bierman, licensed under CC BY 2.0. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/?ref=openverse (accessed on 5 August 2022).

It is a striking piece of art, especially in the light of the fact that it was painted by a Jewish artist at a time when centuries of anti-Judaism had taken an extreme turn under the Third Reich. Chagall painted his Jewish Jesus in a world where the systematic de-Judaization of Christianity was afoot under the leadership of Walter Grundmann (1906–1976), the director of the Institute for the Study and Eradication of Jewish Influence on German Religious Life, and Gerhard Kittel (1888–1948), who edited the Theological Dictionary of the New Testament. Chagall’s Jewish Jesus was an outright criticism of the Aryan Jesus1 propagated by pro-Nazi theologians and religious leaders. The cross, and the visibly Jewish, crucified Jesus, continued to be a recurring motif in many of Chagall’s paintings throughout his career. Of course, not many are as well-known as the White Crucifixion.

What is perhaps even more grossly under-represented is the Jewish intellectual context in which Chagall started painting his crucifixions. He made the sketch for his first crucifixion, Golgotha (1912), in 1909 when a debate called Di Tseylem Frage, or the Crucifix Question, was raging in the Yiddish press. The debate was triggered by the publication of two short stories in Yiddish, discussed later in this paper, that used the symbol of the cross in absolutely contrasting ways. The debate involved a reassessment of the attitude of secular, enlightened East-European Jews towards Jesus and the Christian world at large. The use of Christian themes in Yiddish literature did not end with this debate. On the contrary, Yiddish poets and authors increasingly began engaging with the figure of Jesus and the symbol of the cross through their work. Much of this literature was untranslated at the time of their publication and hence remained unknown to the non-Yiddish-speaking world. As a visual artist, Chagall was not limited by language. Through symbols intimate to both the Jewish and the Christian traditions, he could convey to a larger section the idea that the Jesus whom Christians worship was ultimately Jewish and continues to be on the side of his suffering people.

Scholars such as David G. Roskies (1984), Matthew Hoffman (2007), and Neta Stahl (2013) have written about the depiction of Jesus in both Yiddish and Hebrew literature but in the context of modern Jewish identities. Discussions on the ‘fictional transfigurations of Jesus’ (Ziolkowski 1972) within religious studies, still dominated by Christianity, rarely take into account the Jesuses of Jewish literature, focusing instead on those by authors from Christian backgrounds such as Robert Graves’ King Jesus (1946), Nikos Kazantzakis’ The Last Temptation (1960), Mikhail Bulgakov’s Master and Margarita (1997), Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s The Idiot (1869), C.S. Lewis’ The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe (1950), J.M. Coetzee’s Childhood of Jesus (2013), Philip Pullman’s The Good Man Jesus and the Scoundrel Christ (2010), and so on. The exception is The Liar’s Gospel (2012) by British–Jewish author Naomi Alderman, whose reimagining of the life of Jesus in restive Judea is discussed by Andrew Tate (2016) in his essay on ‘The Challenges of Re-writing Sacred Texts’. While admittedly Tate focuses on twenty-first century retellings of gospel narratives, he does not mention Sholem Asch’s novels The Nazarene (1939), The Apostle (1943), and Mary (1949)—all dealing with the Jewish Jesus and the essentially Jewish character of early Christianity—and clear predecessors of Alderman’s novel. Especially, Alderman’s construction of narrative through four different accounts is strikingly reminiscent of Asch’s narrative style in The Nazarene. Even though, post-Shoah, the Jewish Jesus has found its place in theological, especially Christological discourse, representations of Jesus in Jewish literature remain evidently overlooked.

This paper looks at some of these literary works written in Yiddish, a language that has not only been marginalised by mainstream European society but also within the Jewish community itself.2 In that sense, this paper is an attempt to bring to the fore a marginalised people and their literature. Since literature has the ability to challenge absolutes, and since Christian understandings of Jesus have for so long ignored his Jewishness and hence his humanity, it is pertinent to study Jewish interpretations of Jesus and take into account this challenge to Christian absolutism for improved interfaith relations within pluralistic societies. While the paper’s focus is only on literature in Yiddish, it should be mentioned that many Hebrew poets and authors such as Joseph Klauser, Abraham Kabak, Avraham Shlonksy, Hayyim Hazaz, Pinhas Sadeh, and Avigdor Hameiri also made use of the figure of Jesus in their work. This paper aims to understand why Yiddish poets and authors chose to use an essentially Christian symbol in their writing. To do so, the paper begins with a brief exploration of early Jewish attitudes towards the cross and Jesus. It briefly examines the origins of counternarratives within Judaism that emerged in response to Christian supersessionism and anti-Judaism as well as the role of Jewish historiography in the revaluation of Jesus’ place within Judaism. This also provides the context for the discussion of the literary works this paper cites in order to explicate how portrayals of Jesus in Jewish literature can inform twenty-first century theologies and Christologies. This paper relies on Hoffman’s work for its discussion on many of the Yiddish poets, but while Hoffman analyses these depictions to understand their role in the emergence of modern Jewish culture and their influence on modern Jewish scholarship on Jesus, this paper’s intent is to illustrate the relevance literary Jesuses can have for Christianity and its relationship with Judaism.

2. The Cross and the Crucified One in Early Jewish Imagination

Crucifixion was a common method of executing death sentences in the ancient world. While the Romans used it to oppress the lower class and put down rebels that threatened to disturb status quo, the Persians and Carthaginians imposed the punishment on high officials and commanders (Hengel 1977). Its popularity was most likely owing to the fact that it could cause prolonged suffering and humiliation with only minimum effort from the executing party. Jews were well-acquainted with this method of execution, as is reflected in Deuteronomy 21.23 (JPS): ‘If any party is guilty of a capital offense and is put to death, and you impale the body on a stake, you must not let the corpse remain on the stake overnight but must bury it the same day. For an impaled body is an affront to God: you shall not defile the land that your God יהוה is giving you to possess’. The Hellenistic–Hasmoneans made use of crucifixion to punish high treason. Josephus (1737; XIII 14.2 [An. 88.]) reports in his Antiquities of the Jews that the Hasmonean ruler who combined the offices of Jewish monarch and high priest, Alexander Janneus, ordered eight hundred fellow Jews to be crucified. While Herod most likely broke away with the crucifixion tradition for the political reason of creating distance between himself and the Hasmoneans, the Romans made generous use of it to maintain their control over restive Judea. Hengel (1977) argues that since crucifixion was used as a punishment and because of the Deuteronomic injunction, the cross never became a symbol of Jewish suffering, and therefore the idea of a crucified messiah was unacceptable to most Jews. However, (Chapman 2008) cites The Assumption of Moses or The Testament of Moses, a first-century Jewish apocryphal work as an early document recording the crucifixion of two thousand Jews under Roman general Varus in 4 BCE, and asserts that the text sees, perhaps for the first time, crucified Jews as martyrs who suffered crucifixion for their fidelity to Judaism. It is necessary to remember that the Jews are not monolithic, and Jewish opinion on crucifixion cannot possibly have been homogeneous. Opinions differed based on one’s socio-political context, relation to the ruling party, and to the party being crucified. While some Jews continued in the Jesus movement even though their rabbi was crucified, others found it impossible to reconcile with the cross. By being crucified, Jesus became ‘cursed’ (Galatians 3.13).

As the Jesus movement gained momentum, consolidating its narratives and doctrines, it became increasingly difficult to separate the cross from the passion of Jesus and his followers. Initial silence of the Jewish establishment, now represented by the rabbis after the destruction of the Temple in 70 CE, gave way to derision possibly in the second or third century CE once Christianity began to exert considerable influence as the official religion of the Roman empire (Homolka 2016). This is when the rabbis associated negative images of Esau and Edom with Christianity. The Talmud depicts Jesus as ‘sorcerer and enticer’ (Sanhedrin 43a) and as a rabbinic student who strayed from the path of righteousness to establish ‘an idolatrous religion’ for which he suffers eternal damnation in a ‘seething pit of excrement’ (Sanhedrin 107b, Gittin 56b–57a). With the increase in anti-Jewish discrimination in Christian Europe during the Middle Ages, Jesus became, in the Jewish collective consciousness, the emblem of Christian anti-Judaism responsible for all their misfortunes. This is reflected in the publication of texts such as Toledot Yeshu (Life of Jesus) which parodied the Christian Gospels, referring to Jesus as a mamzer (illegitimate child) and a trickster, and sowed negative images of Jesus in the Jewish folk imagination. Polemical works such as Nizzahon Yashan (Old Polemic; thirteenth c.) used ‘vulgar terms’ to assault Jesus’ moral character (Hoffman 2007). Thought of as a repulsive and demonic figure, Jesus was often referred to by the Yiddish diminutive of his name Yoyzl (Little Joe) with Pandrek as the last name (Pan is an honorific title used for Polish feudal lords, used here sardonically, and drek, which literally means excrement in Yiddish).

In light of this, the Jewish reclamation of Jesus that started with the Enlightenment was revolutionary. The next section looks at the implications of such a change and how these polemics created during the Middle Ages by Jews almost in self-defence gave way to more positive views of Jesus.

3. Enlightenment and the Jewish Reclamation of Jesus

Prior to the eighteenth century, Jesus as interpreted by Christianity was considered the same as the Jesus of history. It was widely accepted that the Gospels provided a reliable account of the life of Jesus. It is only with the Enlightenment in Europe that consistent academic efforts were made, especially by liberal Protestant theologians who could not reconcile their Enlightenment rationalism with the idea of a supernatural redeemer, to apply historical–critical methods to the study of biblical narratives to understand the Jesus of history. However, this also meant that they had to contend with Jesus’ Jewishness, which centuries of religious rivalry and Christian anti-Judaism had obfuscated. Towards the end of the eighteenth century, with the beginning of the Haskalah movement, also known as the Jewish Enlightenment, both Jewish and Christian scholars started writing in the German vernacular, which led to an exchange of theological ideas and, in fact, many Jewish scholars felt compelled to contribute to the historical Jesus project (Sandmel 1965).

Moses Mendelssohn, the German–Jewish philosopher and leading figure in the Haskalah movement, believed Jesus to be an observant Jewish rabbi and an exceptional moral teacher who did not claim to have any divine powers, a position maintained by many amongst the European Jewry (Stahl 2013). Mendelssohn felt that Enlightenment Jews could embrace a Jesus shorn of all dogma that would emerge from historical research to show their Christian counterparts that they harboured no ill-feelings against Jesus or Christianity, which in turn would allow Jews to fully participate in European society. Enlightenment values of liberty, progress, fraternity, and the separation of church and state also made many Jewish intellectuals feel that such a possibility was at hand. Thus, in Mendelssohn’s Berlin Haskalah circle emerged a new movement in modern Jewish history called the Jewish reclamation of Jesus.

In the nineteenth century, the values of the Haskalah and the wider Enlightenment’s progress in scholarship and historicism came together in the Wissenschaft des Judentums movement led by Leopold Zunz, whereby Judaism was presented by Jewish intellectuals as any other academic subject. This was an effort to translate Jewish history and culture into categories understood by the West which would, in turn, make the integration of Jews easier (Hoffman 2007). The result was, however, quite the opposite. As Jewish scholars such as Isaac Markus Jost, Samuel Hirsch, Heinrich Graetz, and Abraham Geiger developed modern Jewish historiography, they considered Jesus an integral part of Jewish history. Of course, each of them understood him differently. While Geiger saw him as a progressive rabbi seeking reform much like himself, Graetz saw him as a Jewish preacher of high moral character who, despite not being learned himself, brought the uneducated and alienated masses closer to the Law. Jost’s Jesus upheld the humanistic values of the Enlightenment, while Hirsch’s Jesus was synonymous with biblical–prophetic Judaism. However, instead of aiding their assimilation in a predominantly Christian society, this reclamation of Jesus suggested that Christianity owed its existence and spiritual identity to Judaism. Highlighting the Jewish roots of Western Civilisation gave Jews a sense of pride in their own history.

Firstly, by subjecting the origins of Christianity, and by extension the Christian West, to scrutiny from a Jewish perspective, they challenged the standard narrative of the majority. Heschel (1998) extends Edward Said’s understanding of discourse and representation as the manifestation of colonialism to explain how Christian Studies on Judaism were means ‘to control, manipulate, even to incorporate, what is a manifestly different (or alternative and novel) world’ (Said 1978, p. 12). For Christian Theology, Judaism represented ‘the other whose negation confirms and even constitutes Christianity’ (Said 1978, p. 26). In treating the history of Christianity as a part of Jewish history, Jewish scholars heralded the demise of Christianity’s intellectual hegemony. The Jewish retelling of the Jesus story, in this context, is subversive and an act of self-empowerment by the colonised, and as Heschel (1998) views it, the first example of postcolonial literature.

Secondly, the figure of Jesus served as a bridge between the Jewish and the Western–Christian worlds. Making Jesus a part of Jewish discourse was a way of engaging with the world that worshipped him and yet hated his people. It was also a way to highlight how Jews were an integral part of that world. Moreover, Jesus became the prototype of the universal, humanistic Jew.

Thirdly, reclaiming Jesus for Judaism equipped modern Jews to critique the Christian world for misunderstanding Jesus’ Jewish teachings, appropriating Judaism, and then subjecting the Jews to centuries of anti-Jewish violence.

Lastly, the Jewish Jesus created an ‘in-between space’ (Hoffman 2007, p. 6) that helped Jews create a new identity and communal selfhood. Bhabha (1994, pp. 1–2) defines such spaces as ‘carrying the burden of the meaning of culture […] which cannot be exclusively claimed by either the majority or the minority culture’. It is in this space of cultural hybridity that modern Jewish selfhood was articulated, transcending the old definitions of ‘Western’ and ‘Jewish’. They radically reimagined the figure who had previously been emblematic of Jewish persecution and anti-Semitism in European Christian society to redefine their own identities for integration into that very society.

The Haskalah brought into focus the question of nonreligious knowledge in Jewish culture. As Jewish public discourse left the ‘Torah study halls, synagogues […] and moved into the multilingual periodical, literary clubs, the republic of letters’, it became easier—with maskilim3 demanding ‘tolerance and freedom of opinion in Jewish life’—to write about Jesus (Feiner 2011, pp. 2, 8). The movement for the Jewish reclamation of Jesus also made space for Jewish authors and poets, who were becoming increasingly aware of their mission and role in the formulation of a modern Jewish identity, to use Christian symbols in their works as they tried to negotiate their place in modern Europe. The following section explores some of these works.

4. The Cross and the Crucified One in Modernist Yiddish Literature

The last decades of the nineteenth century and early twentieth century witnessed an escalation in anti-Jewish violence in Eastern Europe. With every pogrom that raged through Odessa, Kiev, Kishinev, Warsaw, and numerous other towns and villages, Jewish thinkers grew disillusioned with the Haskalah vision of Jewish integration in European society where they, as equal citizens, would play meaningful roles. The altered reality spurred by class conflict and the surge in anti-Semitism called for a ‘radical reconstruction of society’ instead (Krutikov 2001, p. 74). This led to the rise of movements among Jews to make sense of the violence and offer solutions to the Jewish Question.

For Zionists, who had their first congress in 1897 dominated by Liberal Zionists, the only way the Jewish nation could prosper free from the anti-Semitism embedded in the Christian European psyche was to establish a Jewish state in the ancient land of the Jews with Hebrew as the national language. Yiddish was looked upon as the language of exile by many Hebraists and was deemed as the dialect of the ghetto. On the other hand, Simon Dubnow’s Diaspora Nationalism suggested autonomism based on Yiddish culture and education, whereby Jews would have rights and duties as full citizens wherever they reside but would also have the right to develop their community life as members of the Jewish nation. The Jewish Labour Bund founded in 1897, on the other hand, also emphasised Yiddish language and culture but believed class struggle to be inseparable from Jewish emancipation (Fishman 2010).

The Yiddishist movement and the notion of Yiddishism as formulated by its foremost proponent, Yitzhok Leybush Peretz, upheld humanism, the idea that all people are inherently of equal value, which put it at odds with the belief of Jewish chosen-ness. Due to this emphasis on seeking equality and social justice for religious and ethnic minorities, many Yiddishists found socialism compatible with their worldview. Many also became ethical vegetarians. They found kinship with the biblical prophets, many of whom had been social justice warriors and, of course, with Jesus.

It is Der Nister (The Hidden One; pseudonym of Pinhas Kahanovitsh; 1884–1950) who is credited with the lifting of the ancient embargo on depicting Jesus in Jewish literature. While expositing his idea that ‘the survival, glory, and greatness of the human species’ was dependent on the ‘paradoxical union of suffering and love’ (Roskies 1984, p. 263) in his collection of prose poems, Thoughts and Motifs, published in 1907, Der Nister portrayed Mary, the mother of Jesus, praying for the birth of her son despite being forewarned of his fate. Two years later, in 1909, the Yiddish newspaper Dos Naye Lebn (The New Life) edited by socialist revolutionary Chaim Zhitlovsky, published, in consecutive issues, two wildly disparate stories dealing with Christian themes: Lamed Shapiro’s (1879–1948) “Der tseylem” (“The Cross”) and Sholem Asch’s (1880–1957) “In a karnival nakht” (“In a Carnival Night”).

In Shapiro, the cross is a universal symbol of violence. When the protagonist, a Russian Jew, is forced to watch his mother being gang-raped and has the cross etched into the flesh of his forehead by pogromists ‘to save his kike4 soul from hell’ (Shapiro 2007, p. 11), it kills his idealism and lays his world of ideas to waste, turning him from a victim into a killer and a rapist. The cross, ‘a sign of forgiveness’, becomes ‘a scar of mutilation, an emblem of zealousness’ (Roskies 1984, p. 265). Asch’s (1944) “In a Carnival Night” is set in sixteenth-century Rome. Jesus descends from the cross at St Peter’s Basilica to beg the Messiah’s forgiveness for the sadism and depravity to which the Jews of the city are subjected. This involves the pope putting his foot on the head of the elder of the Jewish community who would come carrying the Holy Scroll, signifying the subservience of Judaism to Christianity, during a procession to celebrate the destruction of Jerusalem by the Roman commander Titus. This was followed by a race of eight venerable Jewish elders, who were coerced to run naked, prodded, and whipped, down the Roman Corso for the amusement of Roman citizens. Jesus joins the elders and shares in the suffering of his coreligionists. Thus, the sigil of the coloniser lends himself to the cause of the suffering colonised.

The publication of these two stories led to a passionate debate in the pages of Dos Naye Lebn between Zhitlovsky and the Jewish author and folklorist S. Ansky (1863–1920), which came to be known as Di Tesylem Frage, mentioned earlier in this paper after an essay by the same title that Ansky wrote discussing the implications of depicting Jesus and Christianity in Jewish Literature. The two short stories by Shapiro and Asch represented the two extreme positions on the matter; Shapiro’s cross is a symbol of violence while Asch’s is of reconciliation. Ansky and Zhitlovsky were both leading progressive Yiddish intellectuals. Both were active in the Jewish Left and had been childhood friends. However, for Ansky, Jesus would always be an emblem of Christian hate. The use of Christian symbols seemed to some as akin to becoming a part of the Western world on Christian terms. On the other hand, Zhitlovsky, like Asch, was ready to embrace Jesus as a Jewish revolutionary and martyr. Zhitlovsky’s was a revolutionary socialist outlook which upheld internationalism and universalism over parochial nationalism. For him, the universal humanism of Asch’s story and his eventual body of work held obvious appeal. The views of Ansky and Zhitlovsky on the place of Jesus in Yiddish literature correlated to their views on the kind of relationship Jews must share with the Christian world. In that sense, the Crucifix Question5 was a microcosm of the Jewish Question (Hoffman 2007). How modern enlightened Jews interacted with the figure of Jesus intellectually was representative of how they placed themselves in the larger non-Jewish world and the kind of role such a world had in forming Jewish identity. Asch went on to write several short stories on similar themes of Jewish–Christian reconciliation and three novels on New Testament themes mentioned earlier, for which he faced the ire of the Yiddish press and accusations of apostasy. These novels are replete with historically credible details of first-century Palestine’s socio-political context and have the potential to enrich religious studies and interfaith dialogue. Despite being a fictional representation, The Nazarene compares with more modern research on the Jewish Jesus by scholars such as David Flusser and E.P. Sanders and is a testament to the thirty years of research Asch put into the novel.

Uri Tsvi Grinberg (1896–1981), Jewish literature’s radical modernist, was one of the most notable poets to use the figure of Jesus to address anti-Semitism. Grinberg expressed in the figure of Jesus both his sense of self and his life experiences. His attitude to Jesus swings between traditional revulsion and an enchantment with a character who rebelled against social and religious conventions, much like Grinberg himself who broke away from his Hasidic roots, later becoming a Revisionist Zionist and writing exclusively in Hebrew. The profound ambivalence in Grinberg’s depiction of Jesus (Stahl 2008, p. 50) is a product of his first-hand encounter with human tragedy as a soldier in the Austro–Hungarian army during the First World War, a witness to the 1918 pogrom in his hometown of Lemberg, and indeed the Shoah, in which his entire family perished. In one of his earliest poems, “Ergets af felder” (“Somewhere in the Fields”) written in 1915, Grinberg portrayed a Jesus suffering as a mute spectator to humanity’s agony:

- At sunset, with a deep silent pain—

- I come to you by way of a vision, which draws me to the eastern land

- And I see you, still on the palm-trunk

- Facing the sunset; still

- Dripping, forever, the source of God’s heart …

- And when your sad eye is raised in pity

- To the blue eastern skies—and it floats

- Shimmering gold on the holy crown of thorns—

- I kneel before you

- Surrounded by your pain, the great pain!

(Stahl 2013, p. 52)

Grinberg joins his own suffering with that of Jesus, both witnesses to a tormented humanity. He establishes their shared longing for the ‘eastern land’, an obvious reference to the Holy Land, and through it their common heritage. Jesus, here, is a part of the very landscape of that heritage and inseparable from it. The vision that draws Grinberg to the Holy Land also leads him to Jesus. Interestingly, by the use of the phrase ‘the source of God’s heart’ and the verb ‘kneel’, Grinberg appears to concede divine qualities to Jesus. At other times, Grinberg could also be outright cynical and even mocking in his attitude towards Jesus:

- My head lacks only a crown of thorns,

- Then I’d be the great suffering God.

(Stahl 2013, p. 53)

Harsh as they may seem, these lines also reflect incredible intimacy with the figure of Jesus. The idea that the only thing that differentiates the poet and Jesus is a crown of thorns is an assertion that Jesus too is Jewish much like the poet, and if Jesus’ suffering matters, then so does that of the millions like him. In 1922, Grinberg published in his Berlin journal Albatros a poem titled “Uri Tsvi farn tseylem INRI” (“Uri Tsvi in Front of the Cross INRI”), which he arranged typographically in the form of a cross. Through New Testament references and imagery form the Holy Land, Grinberg paints a Jewish Jesus who has been appropriated by Christianity:

- Lift your voice and weep: forests cry out. The whole earth hangs itself before you.

- And how do you answer all its woe? You cry, you cry, a cursed-Jew-howl.—[…]

- Brother Yeshu. Two thousand years you’ve had your peace and quiet on the cross.

- Around you the world is ending […]

- Eyes too numb to see what lies at your feet. A heap of severed Jew-heads. Prayershawls ripped to shreds. Stabbed scrolls. Blood-spattered white linens. […] Numb Hebrew-pain. Primordial Jew-woe. Golgotha, brother: the one you cannot see. Golgotha is here. Everywhere. Pilate lives. While in Rome they chant psalms in cathedrals.

—(Redfield 2020)

Grinberg refers to Jesus as brother, as a fellow Jew, but one who no longer remembers his Jewishness and has become ‘the other’. Grinberg implores Jesus, in anguished exasperation, to notice the many crucifixions taking place in present-day Golgotha. He introduces the final pathos by pointing to the fact that those present-day Romans who continue to nail Jews to metaphorical crosses, thus condemning them to unending suffering, chant psalms praising a Jewish God and integral to the Jewish tradition. Despite the advancement in scholarship on early Christianity, Second-Temple Judaism, and the Jewish Jesus, Jesus’ Jewishness is still often ignored, especially in ecclesial settings, in a bid to create binaries that emphasise Jesus’ uniqueness as God made flesh. Grinberg’s fellow Jewish brother, Jesus, acts as a warning against such Christologies that divorce Jesus from his Jewishness and make the Jew ‘the other’.

Grinberg’s rage at Christian anti-Judaism, his disappointment in Christian Europe’s failure to uphold the values it prided itself for, and his desire to return to the Holy Land find expression in another poem called “In malkhes fun tseylem” (In the Kingdom of the Cross) published the next year. The Kingdom of the Cross is obviously a reference to Christian Europe for its reverence of the cross but also for its ceaseless torment of the Jewish people, their metaphorical crucifixion:

- In the land of grief upon a sun-day, a black feast day in your honour,

- I’ll open up that forest and I’ll show you all the trees where hang

- My decaying dead.

- Kingdom of the Cross, be pleased.

- Look and see my valleys:

- The shepherds in a circle round the emptied wells;

- Dead shepherds with their lambs’ heads on their knees.

(Howe et al. 1987)

Much like in “Ergets af felder”, the cross here is a tree, and Grinberg has a forest of hanging dead that he would like Christian Europe to see and acknowledge. He wants to draw its attention to the Jewish multitudes who hang and suffer much like Jesus but whose suffering is ignored, if not elevated, by a so-called Christian Europe. It is interesting to note that Grinberg uses the Yiddish word בײמער (beymer; trees) for crosses in keeping with the Hebrew word עֵֽץ (tree, also used for gallows) used in Deuternomy 21.23.

Grinberg’s cynicism towards Jesus as the saviour and messiah is also reflected in H. Leivik (1888–1962). The brutal violence that Grinberg experienced during war, Leivik encountered in Soviet prisons in Siberia, where he was incarcerated at the age of 18 for being a Bundist and distributing revolutionary literature right after the Revolution of 1905. He was smuggled to America in 1913 by other Jewish revolutionaries where he became a part of Di Yunge (The Young Ones), a group of Jewish–American poets who emphasised subjectivism and individualism, and upheld the use of Yiddish for the purpose of aesthetics, not just the dissemination of political ideas to the masses. In his 1915 poem titled “Yezus” (Jesus), where he draws upon his experience in prison, Leivik writes:

- Covered to their necks in gray they lie sleeping

- Head to head and hand to hand, their feet pointing toward the window;

- Up above, somewhere in the corner, trapped in cobwebs

- Jesus hangs on the cross, his mouth coiled and his eyes closed.

(Stahl 2013, p. 171)

The suffering God is depicted as hanging alone, aloof, and impotent, and, ironically, disconnected from the very humanity he is supposed to have suffered for. A similar inanimate Jesus is depicted by Moyshe Leyb Halpern in his epic poem “A nakht” (A Night; 1916) written as a response to the war. However, Halpern attributes Jesus’ helplessness to his own status as victim. Halpern uses messianic–apocalyptic symbols as well as the figure of Jesus/crucifixion to create a surreal End of the Days vision where the personal, historical. and apocalyptic come together in an expression of anguish. Rejecting all forms of redemption and religious and modern ideologies as being useless in the face of tragedy, Halpern portrays a Jesus who is of no comfort to the suffering and yet is someone the poet can deeply sympathise with because Jesus is the ‘archetypal victim of the world’s cruelty’ (Hoffman 2007, p. 152). Halpern saw in Jesus’ crucifixion the suffering of the individual and that of the entire Jewish people:

- And they stretch me out

- On a large black cross.

- They strike me with nail

- And they call this my throne […]

- They drive me out like a demon

- With biblical verses and prayers.

- I run over trail and path,

- I hear chasing behind me.

- I see more and more crosses

- Running towards me.

- I see myself as if through smoke,

- On the crosses up high.

- I close my eyes and run,

- Church walls rise.

- I see myself hanging alone,

- Bleeding on every stone.

(Hoffman 2007, pp. 151–52)

In Halpern, the cross is not just the symbol of the persecutor but also the symbol of Jewish suffering on which he and every Jewish person like him, including Jesus, hangs and bleeds. However, while Jesus’ suffering is given salvific meaning in the Christian narrative, other Jews are nailed to the cross as criminals and demons.

Grinberg and Leivik’s contemporary Itzik Manger’s (1901–1969) poem “Di balade fun dem layzikn mit dem gekreytsikn” (“The Ballad of the Crucified and the Verminous Man”) reflects this same sense of irony, where the ‘verminous’6 man wakes Jesus up and demands to know what it is that makes Jesus’ suffering holier than his own.

- Tell me, O Jesus, where did you hear

- That your crown is holier than my tear?

- Jesus, tell me, who says that your crown

- Is holier than all my pain?

Manger does not directly claim Jesus’ Jewishness. Instead, through rhetorical questions put forward by the ‘verminous’ man, Manger voices the irony in venerating a suffering Jewish man while letting others of flesh and blood suffer. In reply,

- King Jesus stammers, “O wretch, I believe

- Your dust is more holy, more holy your grief.”

- From the crucified trickles a thin, silver cry;

- Smiling, the verminous man turns away

- With heavy step toward the evening town

- For a loaf of bread and a pitcher of wine.

(Wolf 2002)

Stahl (2013) argues that Jesus admitting the “verminous” man’s pain as greater than his own lampoons the idea of Jesus as the “consoling god” who purchased, through suffering, salvation for all humanity. However, it is also ironic that the “verminous” man ultimately takes comfort in such a god conceding defeat to him in this strange race for the most tragic fate. Ultimately, it is humanity that suffers, and such comfort is meaningless. By stripping the religious symbol of meaning and having the ‘verminous’ man look forward to the mundanity of bread and wine, Manger ends his poem on an existentialist note.

The first catechism after the Second Vatican Council, the Dutch Catechism of 1966, described the ‘sin of the world’ as oppression, as ‘the inevitability of wars which break out like ulcers […] the natural arrogance of capitalism and colonialism […] racial and class hatred’ (Haag 1969). To fight this ‘sin of the world’ is to risk persecution, humiliation, and even crucifixion as Jesus did, but it also means that Jesus is on the side of the oppressed and the poor. While Leivik, Halpern, and Manger’s Jesuses are inanimate and helpless, they are also on the side of suffering humanity. Even though the irony in their depictions of the Christian god is unmistakable, they also underscore the fact the Christian god suffered and died, not to strengthen the fists of the powerful, but on the side of the innocent multitudes. A crucified Jesus might not be a comfort to the suffering, but those who claim to be his followers can be. To follow Jesus’ footsteps then would be to resist oppression, but not just the oppression of Christians, but also that of Jews and other religious, ethnic, and gender minorities. There is perhaps no better illustration of this than the use of the metaphor of the cross by some Yiddish poets such as Berish Weinstein to write about violence against African-Americans as discussed by Amelia Glaser (2015). While the use of the potent symbol of the cross to talk about race violence and anti-Semitism was to call out Christian hypocrisy, it is also an invitation to Christians for introspection and action.

American-Jewish poet, Emma Lazarus (1849–87) used Christological imagery in many of her poems such as ‘The Exodus (3 August 1492)’ and ‘The Crowing of the Red Cock’ to discuss Jewish suffering and exile. Emphasizing the debt owed by Christianity and Islam to Judaism in the verse fragment titled ‘The Sower’ from her 1887 poem ‘By the Waters of Babylon’, Lazarus writes, although not in Yiddish:

- Over a boundless plain went a man, carrying seed.

- His face was blackened by sun and rugged from tempest, scarred and distorted by pain. Naked to the loins, his back was ridged with furrows, his breast was plowed with stripes.

- From his hand dropped the fecund seed.

- And behold, instantly started from the prepared soil blade, a sheaf, a springing trunk, a myriad-branching, cloud-aspiring tree […]

- Under its branches a divinely beautiful man, crowned with thorns, was nailed to a cross.

- And the tree put forth treacherous boughs to strangle the Sower; his flesh was bruised and torn, but cunningly he disentangled the murderous knot and passed to the eastward.

- Again there dropped from his hand the fecund seed.

- And behold, instantly started from the prepared soil a blade, a sheaf, a springing trunk, a myriad-branching, cloud-aspiring tree. Crescent shaped like little emerald moons were the leaves; […]

- Under its branches a turbaned mighty-limbed Prophet brandished a drawn sword […]

- What germ hast thou saved for the future, O miraculous Husbandman? Tell me, thou Planter of Christhood and Islam; tell me, thou seed-bearing Israel!

(Lazarus 1887)

The image of the sower immediately brings to mind the Parable of the Sower from Mark 4:1–20, Matthew 13:1–23, and Luke 8:4–15. Christianity has interpreted the sower as Jesus himself who sows the seeds of God’s word in the world. Lazarus takes this familiar Christian image and turns it on its head, almost catching the reader by surprise. It is not Jesus but Israel itself who sowed the seeds of faith in the Ineffable One. Jesus was a product of his Jewishness and Christianity owes its roots to Judaism.

Yiddish modernist Leyb Kvitko (1890–1952*)7, himself a pogrom survivor, depicted a Jewish Jesus who had survived one such pogrom in his poem ‘Eyns, a zundele, an unzers’ (‘A Son, One of Our Own’). Israel Davidson (1870–1939), Peretz Markish (1895–1952*), and Zalman Shneour (1887–1959) all used Jesus and other Christian symbols subversively in their poetry to counter anti-Semitism, identifying the Jewish people ‘as a people of Christs’ (Hoffman 2007, p. 173).In 1929, journalist Rosa Lebensboym, popularly known by her pseudonym Anna Margolin, published a cycle of seven poems titled ‘Mary’, which may or may not have anything to do with the mother of Jesus. Through these poems she explored ideas of gender, sexuality, and identity. While the poems have not been discussed because they do not contain explicit depictions of Jesus’ passion, it is necessary to note that through her, albeit ambiguous, treatment of Mary, Margolin brings out the marginality of women and women Yiddish poets in an essentially patriarchal culture. Melissa Weininger (2017) has argued that her ‘Mary’ poems can be read as a rejection of male-dominated modernist Yiddish poetry’s ‘masculine identification with the figure of Jesus’.

5. Conclusions

This paper demonstrates how the cross, which traditionally symbolised being cursed by God, and historically came to be associated with persecution of Jews, was ultimately reclaimed, along with its most famous victim Jesus, to express Jewish suffering and reassert Jewish identity in the modern world. Many Yiddishists felt that for their work to have universal value, it needed to be a combination of Jewish (particularistic) and Christian (universal) elements, and for these Yiddish modernists, Christianity and the West were synonymous with the universal. By including European/Western/Christian elements, they were not seeking to gain a universal readership but to transform themselves and their Jewish reading audience into a more universalist one. Additionally, Jesus, at once a Jewish martyr, sigil of the persecutor, and Christian God, embodied this delicate balance between the particular and the universal that seemed necessary for the evolution of Yiddish secular humanism but also represented the tension and ambivalence modern Yiddishists felt about such a change. In the grips of discrimination, anti-Jewish violence, pogroms, and genocide, it is through the figure of Jesus and his crucifixion, potent symbols of the Christian world, that they expressed their national tragedy and asserted their worth in a tumultuous world. In his Christ and Culture, Graham Ward (2005) argues that any Christological study must begin with, not who or what, but where is Christ. Additionally, one of the places where interpretations of Jesus are found is popular literature. The Jesus of Jewish literature is especially pertinent to Christian theology for reminding Christians about the oft-ignored Jewish roots of their own faith. Moreover, depictions of Jesus in Jewish literature return Jesus, torn from his people by Christ’s universality, home.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | To reconcile Christianity, which worshipped a Jewish God, and Nazism, which wanted to destroy everything Jewish, Grundmann claimed that Jesus had never been Jewish. He was, in fact, an anti-Jewish Aryan raised in ethnically diverse Galilee. This history had been kept secret by Jews who became a part of the early Church and radically altered the Gospel narratives to obviously suit their own interests (Heschel 2008). |

| 2 | Due to its proximity to German, it has often been viewed as a corruption and a dialect of German by Jews themselves. Moreover, philologists have often failed to recognise that Jews and their languages are not just peripheral points around other European languages that provide useful information about their historical development but centres in their own right. Solomon Birnbaum (1979), the eminent linguist, in his seminal work on the language, Yiddish: A Survey and a Grammar, presents a defence of Yiddish and other linguistic systems particular to the Jews that have been labelled “creolized”, “corrupted”, “jargon”, “dialect”, “mixed”, and essentially “impure”. Its marginality was further heightened by the fact that Yiddish or vaybertaytsh (literally women’s German), as it was called, was traditionally written for women and ‘men who are like women in not being able to learn much’ ((Altshuler 1596) cited in (Seidman 1997) and (Weissler 1989)). |

| 3 | Haskalah intellectuals were known as maskilim (sing. maskil). |

| 4 | In keeping with the translation, the word kike, despite it being an anti-Semitic slur, has been retained. (Hoffman 2007, p. 16) uses ‘Yid’ instead. |

| 5 | In 1910, a similar debate broke out in Zionist circles causing schisms between many intellectuals when two articles, one published by Ahad Ha’am and the other by the Hebrew author Yosef Chaim Brenner, appeared in the Hebrew press. The Brenner Affair, as it came to be called, discussed issues of Jewish apostasy, the role of Judaism in the formation of secular Jewish nationalism, and the place of Jesus and Christianity in secular Jewish thought, and through these tried to define the emerging Zionist Hebrew culture. |

| 6 | The Yiddish word Manger uses is layzikn, which Wolf translates as ‘verminous’. Layzikn is the adjective of the word layz or lice. Layzikn literally means ridden with lice. Anti-Semites associated the Jewish people with both lice and vermin. Hence, Wolf takes the liberty to use them interchangeably for ease of translation. |

| 7 | * Kvitko and Markish were members of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee and associated with the journal Eygns with Yiddish author Dovid Bergelson. All three were executed along with ten other members of the JAC in Moscow in what is called the Night of the Murdered Poets on 12 August 1952. David Hofstein and Itzik Feffer were the other two Yiddish poets who were amongst the executed thirteen. Der Nister, who was arrested after the liquidation of Yiddish culture in the Soviet Union, died in a prison hospital in 1950. |

References

- Altshuler, Moses ben Henoch Yerushalmi. 1596. Brantshpigl [Burning Mirror]. Cracow. [Google Scholar]

- Amishai-Maisels, Ziva. 1991. Chagall’s White Crucifixion. Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies 17: 139–53, 180–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asch, Sholem. 1944. The Carnival Legend. In Children of Abraham. Translated by Maurice Samuel. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bhabha, Homi. 1994. The Location of Culture. New York and London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaum, Solomon. 1979. Yiddish: A Survey and a Grammar. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, David W. 2008. Ancient Jewish and Christian Perceptions of Crucifixion. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. [Google Scholar]

- Feiner, Shmuel. 2011. The Jewish Enlightenment. Translated by Chaya Naor. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fishman, David E. 2010. The Rise of Modern Yiddish Culture. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, Amelia. 2015. From Jewish Jesus to Black Christ: Race Violence in Leftist Yiddish Poetry. Studies in American Jewish Literature 34: 44–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haag, Herbert. 1969. Is Original Sin in Scripture? New York: Sheed & Ward Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Hengel, Martin. 1977. Crucifixion: In the Ancient World and the Folly of the Message of the Cross. Philadelphia: Fortress Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heschel, Susannah. 1998. Abraham Geiger and the Jewish Jesus. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heschel, Susannah. 2008. The Aryan Jesus: Christian Theologians and the Bible in Nazi Germany. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, Matthew. 2007. From Rebel to Rabbi: Reclaiming Jesus and the Making of Modern Jewish Culture. Standford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Homolka, Walter. 2016. Jewish Jesus Research and Its Challenge to Christology Today. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Howe, Irving, Ruth Wisse, and Khone Shmeruk, eds. 1987. The Penguin Book of Modern Yiddish Verse. New York: Viking Penguin Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Josephus, Flavius. 1737. Antiquities of the Jews. In The Genuine Works of Flavius Josephus the Jewish Historian. Translated by William Whiston. London: W. Bowyer. [Google Scholar]

- Krutikov, Mikhail. 2001. Yiddish Fiction and the Crisis of Modernity 1905–1914. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, Emma. 1887. The Sower. In By the Waters of Babylon. Available online: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/46791/by-the-waters-of-babylon (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- Redfield, James Adam, trans. 2020. Uri Zvi before the Cross. In Geveb. Available online: https://ingeveb.org/texts-and-translations/uri-tsvi-before-the-cross (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Roskies, David G. 1984. Against the Apocalypse: Responses to Catastrophe in Modern Jewish Culture. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Said, Edward W. 1978. Orientalism. New York: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Sandmel, Samuel. 1965. We Jews and Jesus. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Seidman, Naomi. 1997. A Marriage Made in Heaven: The Sexual Politics of Hebrew and Yiddish. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, Lamed. 2007. The Cross. In The Cross and Other Jewish Stories. Edited by Leah Garrett. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stahl, Neta. 2008. “Uri Zvi Before the Cross”: The Figure of Jesus in the Poetry of Uri Zvi Greenberg. Religion & Literature 40: 49–80. [Google Scholar]

- Stahl, Neta. 2013. Other and Brother: Jesus in the 20th-Century Jewish Literary Landscape. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tate, Andrew. 2016. The Challenges of Re-writing Sacred Texts: The Case of Twenty-First Century Gospel Narratives. In The Routledge Companion to Literature and Religion. Edited by Mark Knight. Abingdon and New York: Routledge, pp. 332–42. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, Graham. 2005. Christ and Culture: Challenges in Contemporary Theology. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Weininger, Melissa. 2017. A Poetic Paradox: Gender and Self in Anna Margolin’s Mary Cycle. In Geveb. Available online: https://ingeveb.org/articles/a-poetic-paradox-gender-and-self-in-anna-margolins-mary-cycle (accessed on 28 July 2022).

- Weissler, Chava. 1989. “For Women and for Men Who Are like Women”: The Construction of Gender in Yiddish Devotional Literature. Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion 5: 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, Leonard, ed. 2002. The World According to Itzik: Selected Poetry and Prose. Leonard Wolf, trans. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ziolkowski, Theodore. 1972. Fictional Transfigurations of Jesus. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).