Visual Threats and Visual Efficacy: Ideas of Image Reception in the Arguments of Lucas Tudense about the Changes in the Crucifixion (c.1230)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Contra Illos Qui Dicunt …

3. Visual Threats

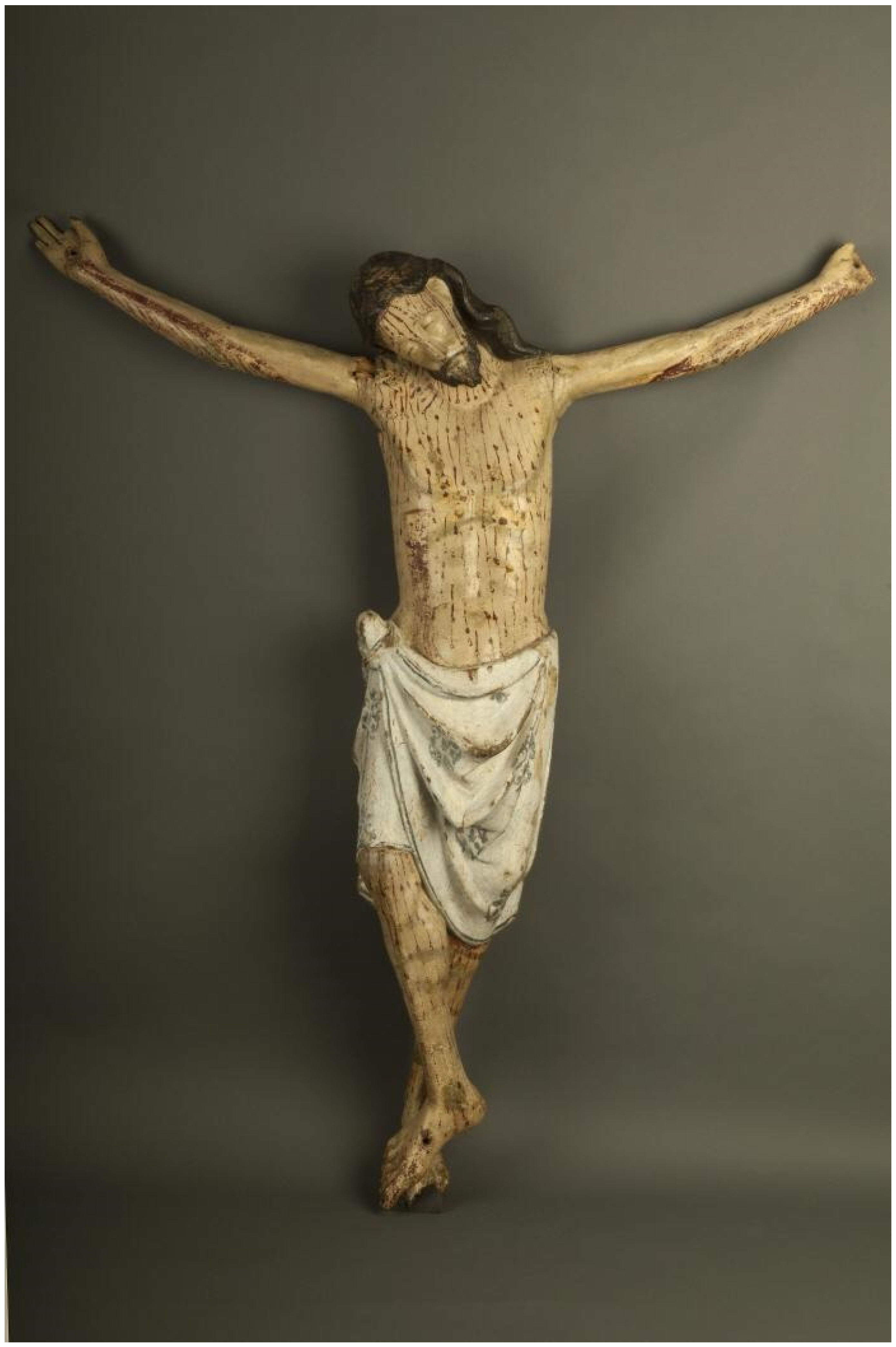

4. Visual Efficacy

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | During the thirteenth century, based on Aristotelian empiricism, a new debate arose about the body and the material world, which came to be considered a valid means of access to knowledge. Consequently, this debate impacted images because they came to be regarded as a path of access to the sacred, but also because the representation of the body and physical suffering underwent a series of variations in their treatment (Mowbray 2009, pp. 13–14). |

| 2 | Different dates have been proposed for its composition: 1227–1239 (Gilbert 1985); 1235–1236/7 (Henriet 2001; Falque Rey 2009b); 1233–1235 (Falque Rey 2011). The title and division into three books belong to the first edition of the book by Juan de Mariana (1609). No medieval manuscript of this text survives, and there is only a sixteenth-century manuscript preserved at the Biblioteca Nacional in Madrid: Lucas. Obispo de Tui: Adversus Albigenses sui temporis haereticos disputatio tribus distinta libris (BN 4172). The manuscript comes from the Dominican Library of Plasencia and has marginal comments by Mariana. See Falque Rey (2009a), pp. xliii–liii. Regarding the author, Lucas’s origins are unclear. It was believed that he was from León since he referred to it as “nostra ciuitate”, but other theories have been proposed placing him in Italy or France (Linehan 2001, pp. 201–7; Linehan 2002, p. 23). Regarding his presence in Tui, it is not documented until 1242 (Linehan 2002, p. 30). |

| 3 | Lucas’s text has been largely referred to within scholarly literature, especially regarding its anti-heretical overtone and its concern with the use of religious images. See (Coulton 1923; Schapiro 1939; Moralejo Álvarez 1994; Gilbert 1985; Falque Rey 2011; Boto Varela 2009; Carreño López 2019; Henriet 2020). Along with the chapters devoted to religious images, the treatise also deals with other significant issues, fundamentally focused on the afterlife and heresy. The first book deals with eschatological content, e.g., the relationship between the living and the dead, the punishments, and the rewards. The second book is composed of several independent treatises in which the author reflects on subjects such as the sacraments and sacramentals, the lifestyle of the clergy, and the Cathar movement. Finally, the third book focuses mainly on heresy and the tactics used by the spiritual dissidents (Falque Rey 2009a, p. xv). |

| 4 | The Tudense’s testimony offers an exceptional piece of evidence regarding image rejection. Some images, especially the Trinity, were often subjects of debate or censorship—as will be mentioned later in this work–, but for the case of the Crucifixion, we cannot find another source as the one under examination. In this regard, I would like to thank one of the reviewers of this article, who has highlighted the originality of Lucas’s approach by searching in the databases Corpus Corporum and the Library of Latin Texts for the expression quat* clav*, confirming that Lucas’s focus on the four nails is certainly novel. |

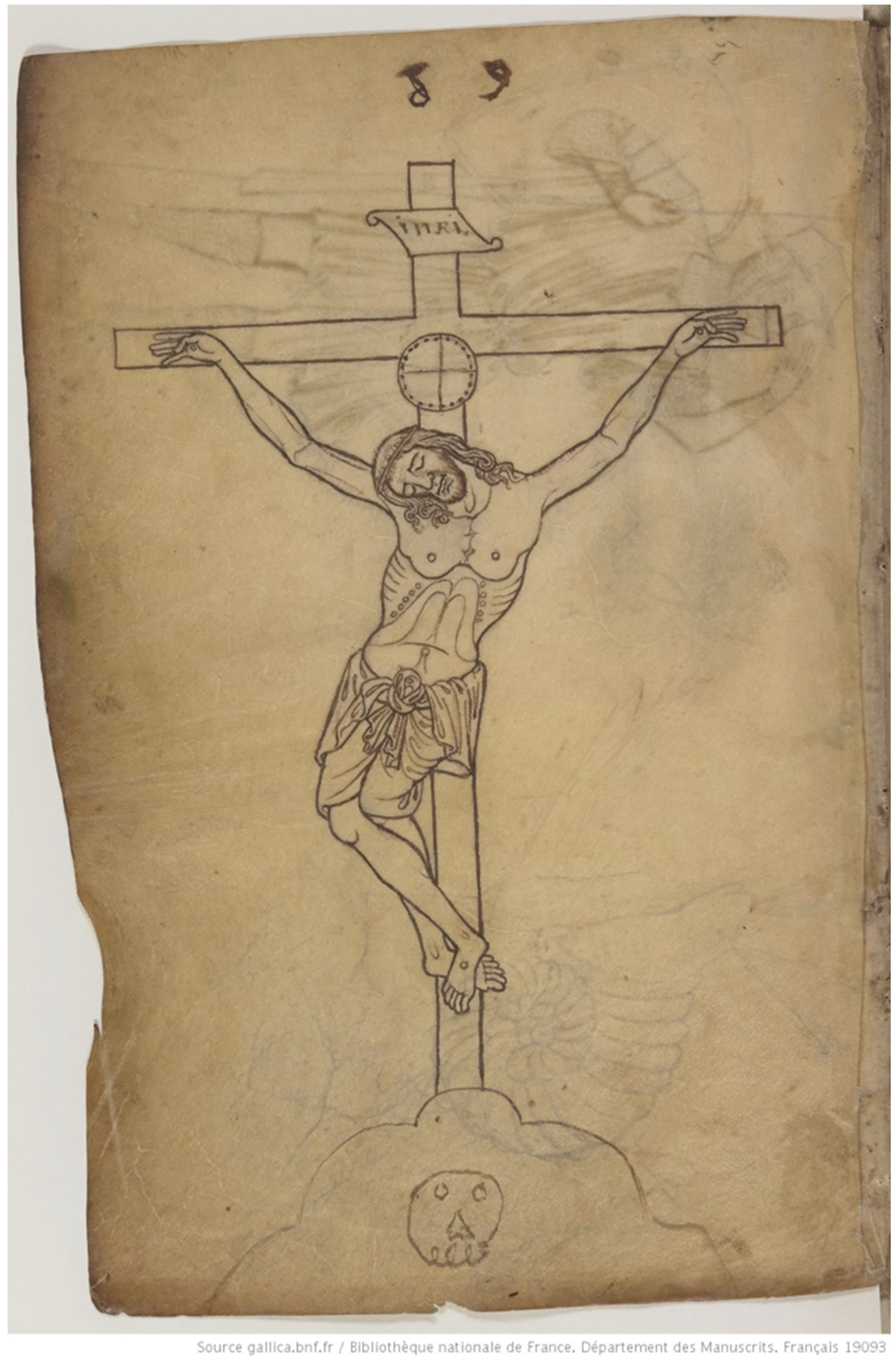

| 5 | It was initially considered that the beginning of this variation occurred around the year 1250; however, the three nails are already adopted in some artworks from the previous century. Thus, this scheme’s origins are dated—for the medieval West—to the middle of the twelfth century (Cames 1966, p. 186). |

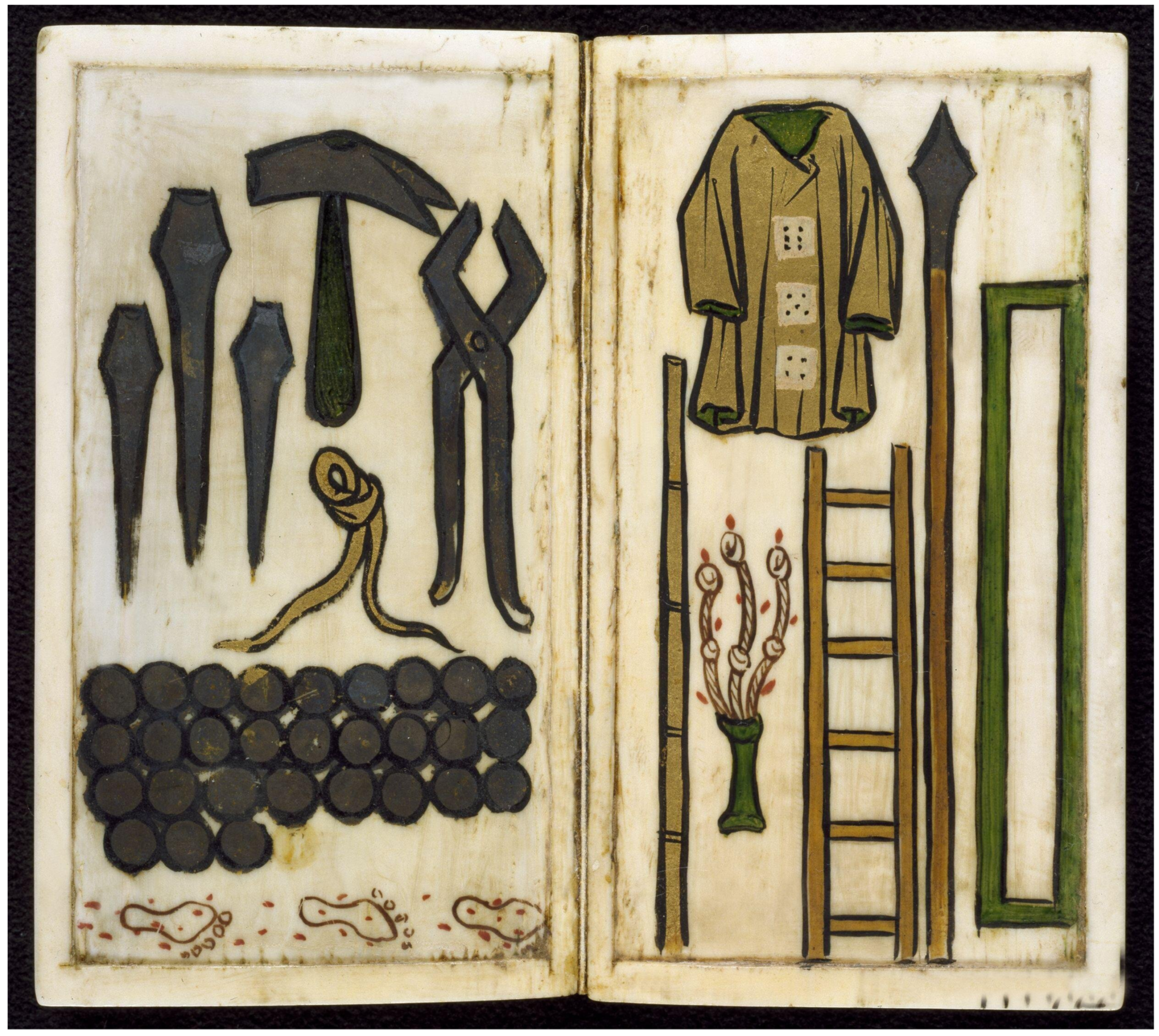

| 6 | See The Arma Christi in Medieval and Early Modern Material Culture (Cooper and Denny-Brown 2014). |

| 7 | The thirteenth century saw the development of theological debates centred on the suffering associated with Christ’s humanity, reflecting on the degree of affliction that Christ would have undergone during his Passion. These ideas surrounding pain helped contemporary theologians emphasise that Christ was indeed a human being. (Mowbray 2009, pp. 31–41), see also (Bynum 1995). |

| 8 | This coexistence of the two types has led to cases with the display of the two variants within the same work. The most common scenario is finding the four nails in the Crucifixion, while only three appear in the depiction of the Arma Christi, as can be seen in the Verdun Altar (1181, Klosterneuburg Abbey) or the Ingeborg Psalter (ca. 1195, Ms. 9 Olim 1695, Musée Condé de Chantilly). A similar case can be found in the Landgrave Psalter (1211–1213, HB II 24, Württembergische Landesbibliothek), where on the Crucifixion the author used three nails, while the Trinity as the Throne of Grace depicted four. |

| 9 | There is a total absence of references to the nails in the Crucifixion episode described in the Gospels. Their use is, however, deduced from other parts of the Bible, such as the foreshadowing in Psalm 21 (16–17) or the episode of the Incredulity of Thomas in the Gospel of John (20, 27). As for the causes that led to this change in the central image of Christianity, these remain uncertain. A synthesis of the different hypotheses is provided by Cames (1966), who suggests that perhaps the three-nailed crucifix was introduced into the West after the Second Crusade (1147). In this regard, the Crusades marked the arrival to Western Europe of both Passion relics and Byzantine artworks, and thus the spread of Passion devotions and the assimilation of Eastern visual codes. |

| 10 | See the Crucifixion of the Muiredach Cross of Monasterboice (tenth century, Co. Louth, Ireland) (Figure 6) or that of the Lorsch Sacramentary (tenth century, Musée Condé of Chantilly). |

| 11 | Good examples are the altar cross of abbess Mathilde in Essen (973–982, Münsterschatzmus, Germany), the crucifix of Hermann and Ida in Cologne (ca. 1050, Kolumba Museum), and the Monmouth Processional Cross (twelfth century, National Museum of Wales). |

| 12 | For the papal refutation see Innocent III, Sermon IV, (‘Common of One Martyr’, Patrologia Latina 217: 612). Lucas alludes to the words of Innocent III in his text: “There were four nails in the Passion of the Lord with which the hands and feet were pierced (…) Two feet and two hands, so four nails must be used by the Christian” (“Fuerunt (…) in passione Domini quatuor claui, quibus manus affixae sunt et pedes affixi (…) Duos pedes et duas manus, quatuor clauis debet configere Christianus”). DAV, CC CM 74A, II, 11, 14–17. Hereafter I will use this abbreviation to quote DAV from the Corpus Christianorum edition of Falque Rey (2009a). |

| 13 | “Quoniam de clauorum numero, qui fixi fuerunt in corpore Dominico, contentio uertitur inter plures” (DAV, CC CM 74A, II, 11, 4–5). DAV is the only text with references to this issue. Precisely because of its exceptional nature, it is difficult (or impossible) to draw a more widely or generally applicable conclusion. In any case—and being aware of the speculative nature of this hypothesis—, it is plausible that the variation in the image of the crucified Christ aroused some debate since for the medieval visual system, characterised by highly encoded images, this would be a significant change which entails a high level of renewal on this iconography. Besides, it was being applied to the representation of one of the central dogmas of the Christian faith: the sacrifice of Christ on the cross to save mankind and offer them the possibility of eternal salvation. |

| 14 | It is common to find references to image theory or arguments about representation in discourses against heretical movements. Several changes in the depiction of religious episodes have been understood as responses to tenets advocated by these spiritual dissenters. A well-known case is the Canon 82 of the Quinisext Council of Constantinople (691–692), in which was established that “in the future, the figure of the Lamb of God, the Saviour … should be replaced in pictures by the image of Christ in His humanity; for Grace and Truth are to be preferred to figures and shadows, typology and symbolism”. This canon was understood as a reaction against heretical movements of the time that rejected Christ’s humanity (Ladner 1953, p. 19). |

| 15 | “Haec contra illos qui dicunt crucem Dominicam tria brachia solummodo habuisse” (DAV, CC CM 74A, II, 10, 109–110). The Castilian ecclesiastic Diego García de Campos also debated in his work Planeta (1218) on the shape of the cross, showing another example of the reactions generated by the changes in images (Palacios Martín 1982, p. 227). |

| 16 | An excellent example of a polemic regarding innovations on the shape of the cross is the Conyhope Cross case (Heslop 1987; Binski 2003). These events took place at a parish church in London, where, following the Annales Londinenses, in the year 1305, “a certain terrifying cross [Crux horribilis] was taken to the chapel of Conyhope, and on the following day called Good Friday was adored by many [adorabatur a multis]” (Heslop 1987, p. 26; Binski 2003, p. 343). The crucifix was referred to as “incorrectly made” since it did not represent the “true shape” of the cross as it did not have a patibulum, being interpreted as an arbitrary invention but not the proper shape of the cross. Berliner (1945, pp. 263–88) deduced that it would have been a crucifix following the German typology of the Gabelkreuz, already familiar in Germany and Italy but not in other territories. In fact, the Conyhope cross was made by a German sculptor called Thydemann (Camille 1989, p. 212). |

| 17 | The scholarly community has widely discussed the existence of Cathars in León, with some authors arguing that Lucas was calling Cathars what would have been lay “rioters and troublemakers” (Fernández Conde 2005, p. 411). Concerning the geo-cultural focus of DAV, Martínez Casado (1983) and Falque Rey have already pointed out how this treatise does not show a local perspective, including just a few references to León, for example, mentioning the arrival to this city of a French heretic named Arnaldo, who forged opuscules of the Holy Fathers (Falque Rey 2009a, p. xviii). However, these local-based stories are narrated along with other cases from beyond the Pyrenees. It is worth noting the broad knowledge that Lucas has of the reality of his time, resulting from his several travels through Europe, which allowed him to get in contact with some of the most important centres and thinkers of his time, for example, his visits to Rome and Paris—especially to Saint-Denis–, and his contact with the Franciscan Elias of Cortona, who from 1221 was Vicar General of the Order of Friars Minor. His sources for DAV also show his great acquaintance with Western European theology, finding references to authors such as Gregory the Great, Augustine of Hippo, Saint Jerome, Isidore of Seville, Pope Innocent III, and Thomas of Celano. This makes Lucas Tudense a figure whose thinking can be set against the broad framework of Western Christianity, as previously highlighted by Henriet (2020, p. 67). Nevertheless, even if Lucas’s ideas can be studied from a global perspective—that of Western Christianity—his thinking would have had a local-based impact on artistic production. In this regard, Moralejo Álvarez (1994, p. 341) already emphasised how in León, there are no anthropomorphic Trinities and how the funerary series of León Cathedral has avoided the use of the three-nails Crucifixion, even when this was already the generalised model. |

| 18 | For an overview of the previous studies that have dealt with the heretical link, (see Henriet 2020, pp. 68–71). The Albigensians were dualists, so they condemned the material world, considering it evil. In this sense, they rejected the sacraments, the resurrection of the flesh, and the humanity of Christ. A revealing reference in this regard appears in the Historia Albigensium (ca. 1215–1218), where there is a reflection on their rejection of the host and the Eucharist, asserting that the host does not differ from lay bread and that Christ’s body would not be big enough so that it would have been already consumed by those eating it (Rubin 1991, p. 321). For them, the human body of Christ was never crucified, he never suffered in the flesh, hence they also rejected the veneration of the cross and the crucifix. In Lucas’s defence of the ecclesiastical institution against this dissident movement, he refers to the “divine” authorities and the Roman Church, praising Pope Innocent III whom he refers to as the “persecutor of heretics”. This Pope fiercely opposed the Albigensians, not just in a dialectic way, but promoting the military campaign known as the Albigensian Crusade (1209–1229) to eradicate Catharism (Pegg 2008). For an approach to the Cathars, (see Sennis 2016; Shulevitz 2018). |

| 19 | In his Chronicon Mundi (c. 1238), when speaking of the Trinity Lucas claims: “(…) haereticus seu pictor desinet per imaginem blasphemiae fabricare” (“The heretic and the painter will cease to fabricate an image of blasphemy”). (Gilbert 1985, p. 151). |

| 20 | There are, in fact, accounts of how the Cathars invented miraculous images so that they could later expose them as frauds. Following the Chronicle of Laon (1154–1219), in Braine, in 1204, “Nicolas, the most famous painter in all France”, was burned by order of the Bishop of Rheims after being accused of being a Cathar heretic (Berliner 1945, p. 282; Heslop 1987, pp. 26–33; Camille 1989, p. 212). |

| 21 | Similar concerns can be found in other authors, especially regarding the Trinity, which would be the most controversial figuration. Saint Antonino, in fifteenth-century Florence, showed his concerns regarding this image: “Reprehensibiles etiam sunt, quum faciunt Trinitatis imaginem unam personam cum tribus capitibus, quod monstrum est in rerum natura”, along with other iconographies: “vel in Annuntiatione Virginis parvulum puerum formatum, scilicet Jesum, mitti in uterum Virginis, quasi non esset de substantia Virginis eius corpus assumtum; vel parvulum Jesum cum tabula litterarum, quum non didicerit ab homine”. (Gilbert 1959, pp. 80–83; Baradel 2018, p. 187). |

| 22 | There are also several studies examining how visual programmes were used to transmit messages against Catharism. (See: Cahn 1987; Goss 1990; Segal 2010). |

| 23 | The field of Neurosciences demonstrates how empathy directs visual attention to emotionally salient stimuli, since they elicit immediate neural responses on the brain (Wilkinson et al. 2021). In this sense, it could be understood that depictions of suffering—such as those developed during the thirteenth century—would more successfully call the attention of viewers. |

| 24 | “Certain images are painted or carved in the church of Christ for the defence of the faithful, for doctrine, for imitation, and adornment. Some are doctrine, imitation and likewise for adornment, and some are for adornment only. Some are indeed for doctrine, so that in them men may learn to fear to behave sinfully”, translation by Gilbert (1985, p. 136). “Depinguntur uel sculpuntur imagines in ecclesia Christi quaedam ad fidelium defensionem, doctrinam, imitationem et decorem. Quaedam similiter ad doctrinam, imitationem et decorem, et quaedam ad decorem tantum, quaedam etiam ad doctrinam, ut in eis timere praue agere discat homo” (DAV, CC CM 74A, II, 20, 7–11). Regarding “decorem”, Moralejo Álvarez refutes Gilbert, for whom it would just imply mere decoration, while Moralejo Álvarez understands it as a synonym for “honour and decorous” (Moralejo Álvarez 1994, p. 345). |

| 25 | Falque Rey already stressed the importance of Gregory the Great for the work of Lucas, finding several references to this Pope throughout the book (Falque Rey 2009a, pp. xxii–xxvii). |

| 26 | Several scholars have studied these letters. (See Jones 1977; Peterson 1984; Kessler 1985; Schmitt 2002; Duggan 2005). Medieval image theory and the justifications given for the existence of religious images is a more complex subject widely studied by other scholars. For a broader analysis see e.g.,: (Ladner 1953; Kitzinger 1954; Camille 1989; Duggan 2005; Freedberg 1989; Belting [1990] 2009; Schmitt 2002). |

| 27 | This Pope asserted in these letters: “Pictures are used in churches so that those who are ignorant of letters may at least read by seeing on the walls what they cannot read in books” (“Idcirco enim pictura in ecclesiis adhibetur, ut hi qui litteras nesciunt saltem in parietibus uidendo legant, quae legere in codicibus non ualent”); and “What writing does for the literate, a picture does for the illiterate looking at it, because the ignorant see in it what they ought to do; those who do not know letters read in it. Thus, especially for the nations, a picture takes the place of reading… Therefore, you ought not to have broken that which was place in the church in order not to be adored but solely in order to instruct the minds of the ignorant” (“Nam quod legentibus scriptura, hoc idiotis praestat pictura cernentibus, quia in ipsa ignorantes uident quod debeant, in ipsa legunt qui litteraas nesciunt; unde praecipua gentibus pro lectione pictura est… Frangi ergo non debuit quod non ad adorandum in ecclesiis sed ad instruendas solummodo mentes fuit nescientium collacatum”). Translations by Duggan (2005, p. 63). |

| 28 | “In fact, the images were introduced for a threefold reason, namely, for the ignorance of humble people, so that those who cannot read the Scriptures may read the sacraments of our faith in sculptures and paintings, as one would do more manifestly in writings. They are introduced also by the lulling of the feelings, that is, so that those who are not stimulated to devotion by the things Christ did for us when they hear of them, may be excited when they notice the same things in statues and pictures, as if they were made present to the eyes of the body. Our feeling is more excited by the things we see than by the things we hear (…) because of the unreliability of memory, for things that are only heard fade away more easily than those that are seen (…) Therefore it has been established by the grace of God that images appear especially in churches, so that, on seeing them, we will be reminded of the benefits that have been granted to us and of the worthy works of the saints”, translation by Hamburger (2006, p. 15). “Dicendum, quod imaginum introductio in Ecclesia non fuit absque rationabili causa. Introductae enim fuerunt propter triplicem causam, videlicet propter simplicium ruditatem, propter affectuum tarditatem et propter memoriae labilitatem.—Propter simplicium ruditatem inventae sunt, ut simplices, qui non possunt scripturas legere, in huiusmodi sculpturis et picturis tanquam in scripturis apertius possint sacramenta nostrae fidei legere.—Propter affectus tarditatem similiter introductae sunt, videlicet ut homines, qui non excitantur ad devotionem in his quae pro nobis Christus gessit, dum illa aure percipiunt, saltem exitentur, dum eadem in figuris et picturis tanquam praesentia oculis corporeis cernunt. Plus enim excitatur affectus noster per ea quae videt, quam per ea quae audit. Unde Horatios: ‘Segnius irritant animos demissa per aurem, quam quae sunt oculis subiecta fidelibus, et quae Ipse sibi tradit spectator”.—Propter memoriae libilitatem, quia ea quae audiuntur solum, facilius traduntur oblivioni, quam ae quae videntur. Frequenter enim verificatur in multis illud quod consuevit dici: verbum intrat per unam aurem et exit per aliam. Praeterea, non semper est praesto qui beneficia nobis praestita ad memoriam reducat per verba. Ideo dispensatone Dei factum est, ut imagines fierent praecipue in ecclesiis, ut videntes eas recordemur de beneficiis nobis impensis et Sanctourm operibus virtuosis” (Bonaventura, III, IX, 1.2, p. 203). |

| 29 | “There were three reasons for the institution of images in the churches. First, for the instruction of the simple people, because they are instructed by them as by books. Secondly, the mystery of the Incarnation and the examples of the saints might be more active in our memory by being daily represented to our eyes. Thirdly, to excite the sentiments of devotion, which are more effectively aroused by things seen than by things heard” (“Fuit autem triplex ratio institutionis imaginum in Ecclesia. Primo ad instructionem rudium, qui eis quasi quibusdam libris docentur. Secundo ut incarnationis mysterium et sanctorum exempla magis in memoria essent, dum quotidie oculis reprœsentatur. Tertio ad excitandum devotionis affectum qui ex visis efficacius incitatur quam ex auditis”). (Thomas Aquinas, III Sententiarum, lib. III dist. 9, q. 1, art. 2, q. 2). |

| 30 | On medieval memory, (see Carruthers 1990). |

| 31 | “Adorare igitur debemus sicut diuinam Scripturam imagines sacras, quae aspicientibus sanctam deuotionem excitant et doctrinam edocent salutarem credentes” (DAV, CC CM 74A, II, 21, 189–191). |

| 32 | “Hae imagines subtili debent fieri congruitate, ut pulchritudinem honestatis aspicientibus repraesentent et deuotionem excitent pietatis” (DAV, CC CM 74A, II, 20, 27–29). |

| 33 | “But someone may say: ‘In this respect, we affirm that the Lord was crucified with a single nail with one foot on the other, and we want the customs of the church to be changed so that the devotion of the people be aroused before the greater bitterness of the Passion of Christ, and, after the renewal of the customs, boredom may be avoided. For these things do not concern the substance of the sacraments or the articles of faith, and they may vary from day to day according to the taste of each one. It is sufficient for salvation to believe that Christ was crucified, and it is indifferent to consider that he was hung on a four-armed or three-armed cross, that he was nailed with four or three nails and that his right or left side was pierced with a lance’” (“Sed dicit aliquis: ‘Ad hoc uno pede super alio uno clauo Dominum dicimus crucifixum et consuetudines Ecclesiae uolumus immutari, ut maiori acerbitate passionis Christi populi deuotio excitetur et, nouitate in consuetudinibus succedente, fastidium releuetur. Non enim sunt ista de sacramentorum substantia uel articulorum fidei et possunt quotidie ad libitum uariari. Sufficit ad salutem Christum credere crucifixum et pro indifferenti habere in cruce illum quatuor uel trium brachiorum fuisse positum, quatuor uel tribus clauis confixum et dextrum uel sinistrum latus eius lancea uulneratum. Etiam aliqua fingenda sunt pro loco et tempore, quamuis uera non sint, ut Christi nominis gloria diletatur’”) (DAV, CC CM 74A, II, 11, 147–157). For the translation of this passage, I relied both on the Latin edition and the Spanish translation of Falque Rey (2011). |

| 34 | These theories postulated by medieval authors can be studied nowadays with new tools developed in other disciplines that approach the functioning of the human brain, such as Neuroscience or Psychology. Regarding corporal sensations triggered through visual perception, it has been established that both emotional and cognitive responses can lead to feeling visceral responses, since they are represented in the somatosensory cortex (Zaidel 2005, p. 172). In this sense, empathetic responses can be understood as both haptic and optic since visual stimuli are experienced with the eyes, but also with other body parts, especially common in the case of skin reactions and muscle sensations. |

| 35 | “Affective piety” is a form of spirituality that from the twelfth century onwards gave a greater emphasis to the inner emotions and the devotion to the humanity of Christ. (Bartlett and Bestul 1999; Megna 2020). |

| 36 | “Debet namque domus Dei cultu uario resplendere, ut ipsa eius exterior pulcritudo homines ad se ducat et taedium non inferat assistentibus, mentem subleuet ad coelestia expetanda pulcritudine sua decorem coelestis patriae repraesentans”. (DAV, CC CM 74A, II, 20, 29–32). |

| 37 | “Domus Dei exterior pulcritudo dum oculos de foris mulcet, nonnunquam interiorem ad Dominum trahit” (DAV, CC CM 74A, II, 20, 33–34). |

| 38 | On medieval theories of cognition, and of how cognitive processes were thought to operate, (see Karnes 2011). |

References

Primary Sources

Bonaventure. Doctoris seraphici S. Bonaventurae opera omnia, III: Commentaria in quatuor libros sententiarum Magistri Petri Lombardi. Rome: Quarrachi. 1887 edition. Available online: https://archive.org/details/doctorisseraphic03bona/page/204/mode/2up?view=theater (accessed on 21 March 2022).Falque Rey, Emma, ed. 2009a. Lucae Tudensis. De altera uita. Corpus Christianorum. Continuatio Medievalis, 74A. Turnhout: Brepols.Thomas Aquinas, III Sententiarum. Centre Traditio Litterarum Occidentalium, CETEDOC, and Brepols (Firm). 2000. Library of Latin Text, Series A. Series A. Turnhout: Brepols. Available online: http://clt.brepolis.net/LLTA/ (accessed on 5 May 2022).Secondary Sources

- Bagnoli, Martina. 2016. Making Sense. In A Feast for the Senses: Art and Experience in Medieval Europe. Edited by Martina Bagnoli. Baltimore: The Walters Art Museum, pp. 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Baradel, Valentina. 2018. Immagini per "mouver divozione" a Venezia all’inizio del Quattrocento. In Pregare in casa. Oggetti e documenti della pratica religiosa tra Medioevo e Rinascimento. Edited by Giovanna Baldissin Molli, Cristina Guarnieri and Zuleika Murat. Roma: Viella. [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett, Anne Clark, and Thomas H. Bestul. 1999. Introduction. In Cultures of Piety: Medieval English Literature in Translation. Edited by Anne Clark Bartlett and Thomas H. Bestul. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Beaven, Lisa. 2020. Seeing and Feeling. In The Routledge History of Emotions in Europe, 1100–1700. Edited by Susan Broomhall and Andrew Lynch. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 151–68. [Google Scholar]

- Belting, Hans. 2009. Imagen y Culto. Una Historia de la Imagen Anterior a la era del Arte. Madrid: Akal. First published 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Berliner, Rudolf. 1945. The Freedom of Medieval Art. Gazette des Beaux-Arts 6: 263–88. [Google Scholar]

- Bestul, Thomas H. 1996. Texts of the Passion. Latin Devotional Literature and Medieval Society. The Middle Ages Series; Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Biernoff, Suzannah. 2002. Sight and Embodiment in the Middle Ages. Series The New Middle Ages; Hampshire and New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Binski, Paul. 2003. The Crucifixion and the Censorship of Art around 1300. In The Medieval World. Edited by Peter Linehan and Janet L. Nelson. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 342–60. [Google Scholar]

- Binski, Paul. 2004. Becket’s Crown. Art and Imagination in Gothic England, 1170–1300. Serie Studies in British Art; New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boto Varela, Gerardo. 2009. Sobre las persuasivas imágenes de culto. Encomios y escrutinios desde la Edad Media hispana. In Imágenes Medievales de culto. Tallas de la Colección ‘El Conventet’. Edited by Gerardo Boto Varela. Murcia: Consejería de Cultura y Turismo de Murcia, pp. 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Bynum, Caroline Walker. 1995. The Resurrection of the Body in Western Christianity: 200–1336. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bynum, Caroline Walker. 2011. Christian Materiality. An Essay on Religion in Late Medieval Europe. New York: Zone Books. [Google Scholar]

- Cahn, Walter. 1987. Heresy and Interpretation of Romanesque Art. In Romanesque and Gothic: Essays for George Zarnecki, II. Edited by Neil Stratford. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer, pp. 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Cames, Gérard. 1966. Recherches sur les origines du crucifix à trois clous. Cahiers archéologiques: Fin de l’Antiquité et Moyen Age 16: 185–202. [Google Scholar]

- Camille, Michael. 1989. The Gothic Idol. Ideology and Image-Making in Medieval Art. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cannon, Joanna. 2013. Religious Poverty, Visual Riches. Art in the Dominican Churches of Central Italy in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carreño López, Sara. 2019. La imagen escultórica del Crucificado en la Galicia del siglo XIV. Tipos, usos y significados. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Santiago de Compostela, Santiago, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Carruthers, Mary J. 1990. The Book of Memory: A Study of Memory in Medieval Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, Lisa H., and Andrea Denny-Brown, eds. 2014. The Arma Christi in Medieval and Early Modern Material Culture. Farnham: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Coulton, George G. 1923. Art and the Reformation. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- de Francovich, Géza. 1938. L’origine e la diffusione del Crocifisso gotico doloroso. Römisches Jahrbuch für Kunstgeschichte 2: 143–261. [Google Scholar]

- Derbes, Anne. 1996. Picturing the Passion in Late Medieval Italy. Narrative Painting, Franciscan Ideologies, and the Levant. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Duggan, Lawrence G. 2005. Was Art Really the "Book of the Illiterate"? In Reading Images and Texts. Medieval Images and Texts as Forms of Communication. Papers from the Third Utrech Symposium on Medieval Literacy, Utrecht, 7–9 December 2005. Edited by Mariëlle Hageman and Marco Mostret. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 63–107. [Google Scholar]

- Falque Rey, Emma. 2009b. De altera uita: Una obra olvidada de Lucas de Tuy. In La filología latina. Mil años más, II. Edited by Pedro Conde Parrado and Isabel Velázquez Soriano. Burgos and Madrid: Fundación Instituto Castellano y Leonés de la Lengua-Sociedad de Estudios Latinos, pp. 959–68. [Google Scholar]

- Falque Rey, Emma. 2011. La iconografía de la crucifixión en un tratado escrito en latín en el s. XIII por Lucas de Tuy. Laboratorio de arte. Revista del Departamento de Historia del Arte 23: 19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Conde, Francisco Javier. 2005. La Religiosidad Medieval en España. Plena Edad Media (Siglos XI–XIII). Gijón: Ediciones Trea. [Google Scholar]

- Flora, Holly. 2009. The Devout Belief of the Imagination. The Paris ‘Meditationes Vitae Christi’ and Female Franciscan Spirituality in Trecento Italy. Series Disciplina Monastica, 6; Turnhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Franco Mata, Ángela. 2002. Crucifixus dolorosus. Cristo crucificado, el héroe trágico del cristianismo bajomedieval, en el marco de la iconografía pasional, de la liturgia, mística y devociones. Quintana. Revista do Departamento de Historia da Arte 1: 13–39. [Google Scholar]

- Freedberg, David. 1989. The Power of Images: Studies in the History and Theory of Response. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, Creighton. 1959. The Archbishop on the Painters of Florence, 1450. The Art Bulletin 41: 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, Creighton. 1985. A Statement of the Aesthetic Attitude around 1230. Hebrew University Studies in Literature and the Arts 13: 125–52. [Google Scholar]

- Goss, Vladimir P. 1990. Art and Politics in the High Middle Ages: Heresy, Investiture Contest, Crusade. In Artistes, Artisans, et Production Artistique au Moyen Âge, III: Fabrication et Consummation de L’oeuvre. Edited by Xavier Barral I. Altet. Paris: Picard, pp. 525–45. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn, Cynthia. 2006. Vision. In A Companion to Medieval Art. Romanesque and Gothic in Northern Europe. Edited by Conrad Rudolph. Blackwell Companions in Art History. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 44–64. [Google Scholar]

- Hamburger, Jeffrey F. 2006. The Place of Theology in Medieval Art History: Problems, Positions, Possibilities. In The Mind’s Eye. Art and Theological Argument in the Middle Ages. Edited by Jeffrey F. Hamburger and Anne-Marei Bouché. Series Publications of the Department of Art and Archaeology, 25; Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 11–31. [Google Scholar]

- Henriet, Patrick. 2001. Sanctissima patria: Points et themes communs aux trois aeuvres de Lucas de Tuy. Cahiers d’Études Hispaniques Médiévales 24: 249–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriet, Patrick. 2020. Lucas et les images. Tradition et modernité, monde hispanique et monde extérieur. Codex Aquilarensis 36: 65–90. [Google Scholar]

- Heslop, Thomas Alexander. 1987. Attitudes to the Visual Arts: The Evidence from Written Sources. In Age of Chivalry. Art in Plantagenet England 1200–1400. Edited by Jonathan Alexander and Paul Binski. London: Royal Academy of Arts, pp. 26–32. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, William R. 1977. Art and Christian Piety: Iconoclasm in Medieval Europe. In The Image and the Word. Confrontations in Judaism, Christianity and Islam. Edited by Joseph Gutmann. Missoula: Scholars Press for the American Academy of Religion, pp. 75–106. [Google Scholar]

- Kalina, Pavel. 2003. Giovanni Pisano, the Dominicans, and the Origins of the ‘crucifixi dolorosi’. Atribus et Historiae 24: 81–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnes, Michelle. 2007. Nicholas Love and Medieval Meditations on Christ. Speculum. A Journal of Medieval Studies 82: 380–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnes, Michelle. 2011. Imagination, Meditation, and Cognition in the Middle Ages. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, Herbert. 1985. Pictorial Narrative and Church Mission in the Sixth-Century Gaul. Studies in the History of Art 16: 75–91. [Google Scholar]

- Kitzinger, Ernst. 1954. The Cult of Images in the Age before Iconoclasm. Dumbarton Oaks Papers 8: 83–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladner, Gerhart B. 1953. The Concept of the Image in the Greek Fathers and the Byzantine Iconoclastic Controversy. Dumbarton Oaks Papers 7: 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linehan, Peter. 2001. Dates and Doubts about D. Lucas. Cahiers d’Études Hispaniques Médiévales 24: 201–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linehan, Peter. 2002. Fechas y sospechas sobre Lucas de Tuy. Anuario de Estudios Medievales 32: 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipton, Sarah. 2005. ‘The Sweet Lean of His Head’: Writing about Looking at the Crucifix in the High Middle Ages. Speculum. A Journal of Medieval Studies 80: 1172–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunghi, Elvio. 2000. La Passione degli Umbri. Crocifissi di legno in Valle Umbra tra Medioevo e Rinascimento. Foligno: Orfini Numeister. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Casado, Ángel. 1983. Cátaros en León. Testimonio de Lucas de Tuy. Archivos Leoneses 74: 263–312. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzon, Gabriella. 2018. Pathos in Late-Medieval Religious Drama and Art. A Communicative Strategy. Ludus. Medieval and Early Renaissance Theatre and Drama, 15. Leiden and Boston: Brill-Rodopi. [Google Scholar]

- McGinn, Bernard. 2006. Theologians as Trinitarian Iconographers. In The Mind’s Eye. Art and Theological Argument in the Middle Ages. Edited by Jeffrey F. Hamburger and Anne-Marei Bouché. Series Publications of the Department of Art and Archaeology, 25; Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 186–207. [Google Scholar]

- McNamer, Sarah. 2009. The Origin of the Meditations Vitae Christi. Speculum. A Journal of Medeival Studies 84: 905–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megna, Paul. 2020. Dreadful Devotion. In The Routledge History of Emotions in Europe, 1100–1700. Edited by Susan Broomhall and Andrew Lynch. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 72–85. [Google Scholar]

- Moralejo Álvarez, Serafín. 1994. D. Lucas de Tuy y la “actitud estética” en el arte medieval. Euphrosyne. Revista de Filología Clássica 22: 341–46. [Google Scholar]

- Mowbray, Donald. 2009. Pain and Suffering in Medieval Theology. Academic Debates at the University of Paris in the Thirteenth Century. Woodbridge and Rochester: The Boydell Press. [Google Scholar]

- Munns, John. 2016. Cross and Culture in Anglo-Norman England: Theology, Imagery, Devotion. Serie Bristol Studies in Medieval Cultures. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer. [Google Scholar]

- Murat, Zuleika. 2022. Seeing with the Eyes of the Soul. Pacino di Bonaguida’s Scenes from the Life of Christ and the Life of Blessed Gerard of Villamagna (New York, The Morgan Library & Museum, M.643). Rivista di Storia della Miniatura 26. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, Barbara. 2005. What Did I Mean to Say ‘I Saw’? The Clash Between Theory and Practice in Medieval Visionary Culture. Speculum. A Journal of Medieval Studies 80: 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios Martín, Bonifacio. 1982. La circulación de los cátaros por el Camino de Santiago y sus implicaciones socioculturales. Una fuente para su conocimiento. En la España Medieval 3: 219–30. [Google Scholar]

- Pegg, Mark G. 2008. A Most Holy War: The Albigensian Crusade and the Battle for Christendom. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, Joan M. 1984. The Dialogues of Gregory the Great in their Late Antique Cultural Background. Series Studies and Texts of the Pontifical Institute, 69; Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, pp. 189–91. [Google Scholar]

- Pickering, Frederick. 1980. The Gothic Image of Christ. The Sources of Medieval Representations of the Crucifixion. In Essays on Medieval German Literature and Iconography. Anglica Germanica Series 2; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Prehn, Eric T. 1968. Visual Perception in XIII-Century Italian Painting. Rome: Tip Risorgimento. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, Miri. 1991. Corpus Christi. The Eucharist in Late Medieval Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schapiro, Meyer. 1939. From Mozarabic to Romanesque in Silos. The Art Bulletin 21: 313–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiller, Gertrud. 1972. Iconography of Christian Art. 2 vols. London: Hund Humphries. First published 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, Jean-Claude. 2002. Le corps des Images. Essais sur la Culture Visuelle au Moyen Âge. Serie Le temps des images; Paris: Gallimard. [Google Scholar]

- Segal, Einat. 2010. Sculpted Images from the Eastern Gallery of the Saint-Trophime Cloister in Arles and the Cathar Heresy. In Difference and Identity in Francia and Medieval France. Edited by Meredith Cohen and Justine Firnhaber-Baker. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 43–76. [Google Scholar]

- Sennis, Antonio, ed. 2016. Cathars in Question. Series Heresy and Inquisition in the Middle Ages; Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer. [Google Scholar]

- Shulevitz, Deborah. 2018. Historiography of Heresy: The Debate over Catharism in medieval Languedoc. History Compass 17: e12513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoby, Paul. 1959. Le Crucifix des Origines au Concile de Trente: Étude Iconographique. 2 vols. Nantes: Bellanger. [Google Scholar]

- Viladesau, Richard. 2006. The Beauty of the Cross. The Passion of Christ in Theology and the Arts from the Catacombs to the Eve of the Renaissance. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Warr, Cordelia. 2007. Re-reading the Relationship between Devotional Images, Visions, and the Body: Clare of Montefalco and Margaret of Città di Castello. Viator 38: 217–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, Zane, Róisín Cunningham, and Mark. A. Elliott. 2021. The Influence of Empathy on the Perceptual Response to Visual Art. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts; American Psychological Association. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2021-78152-001 (accessed on 5 May 2022).

- Williamson, Beth. 2013. Sensory Experience in Medieval Devotion: Sound and Vision, Invisibility and Silence. Speculum. A Journal of Medieval Studies 88: 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidel, Dahlia W. 2005. Neuropsychology of Art: Neurological, Cognitive and Evolutionary Perspectives. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carreño, S. Visual Threats and Visual Efficacy: Ideas of Image Reception in the Arguments of Lucas Tudense about the Changes in the Crucifixion (c.1230). Religions 2022, 13, 779. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13090779

Carreño S. Visual Threats and Visual Efficacy: Ideas of Image Reception in the Arguments of Lucas Tudense about the Changes in the Crucifixion (c.1230). Religions. 2022; 13(9):779. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13090779

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarreño, Sara. 2022. "Visual Threats and Visual Efficacy: Ideas of Image Reception in the Arguments of Lucas Tudense about the Changes in the Crucifixion (c.1230)" Religions 13, no. 9: 779. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13090779

APA StyleCarreño, S. (2022). Visual Threats and Visual Efficacy: Ideas of Image Reception in the Arguments of Lucas Tudense about the Changes in the Crucifixion (c.1230). Religions, 13(9), 779. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13090779