1. Introduction

The study of religion encompasses a spectrum of disciplinary and thematic subfields engaging in a vast range of inquiry. Similarly, classrooms engaged in the study of religion employ diverse course texts or resources for student and scholarly use that are introductory (

McCutcheon 2019), thematic (

Orsi 2012), discipline-specific (

Insoll 2012;

White 2021;

Hinnells 2007), or expansive encyclopedia-type works (

Oxtoby et al. 2015;

Ellwood and Alles 2006;

Jones 2004). In the current age of “Big Data”, scholars can no longer expect to keep current with the exponential growth of new data and publications even within their own specific discipline. Much more so for students newly embarking in academic careers, the sheer scope of available information can be daunting. With such a rapid increase of information, new digital and queryable tools are necessary to efficiently and accurately navigate basic information, and the trajectory of scholarly interpretation both in “big history” and regionally (or chronologically) restricted contexts.

This article explores a newly available tool that responds to these challenges. Here, we analyze how introductory or advanced courses on religion—whether broader anthropological, sociological or historical approaches, or more geographically restricted within area-studies disciplines—can make use of the Database of Religious History (henceforth DRH;

https://religiondatabase.org, accessed on 15 March 2022) as a digital resource. Open-access and digital, the DRH, we argue, is a useful tool for an instant summary of thematic, regional, or chronologically restricted questions related to a variety of themes within the broader realm of religious studies. The DRH can weave together scholarly inquiry and pedagogical application in ways that facilitate a teacher-scholar model.

In the following, we first provide a brief demonstration of the structure of the DRH and how it may be used as a pedagogical and scholarly tool that presents an expansive and queryable dataset with which to explore various questions related to the study of religion. Next, a series of case studies demonstrates the capacity of the DRH to probe questions concerning the nature of “high gods” in discipline-specific contexts. We then provide a section on classroom applications that assesses the strengths, limitations, and prospects of the DRH in this setting. Overall, the main objective of this paper is to draw attention to a vast and continuously expanding digital resource that offers exciting opportunities for scholarly and pedagogical use.

2. The Database of Religious History: An Overview

The DRH was established in 2013 with the goal of creating an open-access database where qualitative and quantitative data representing the breadth of human religious experience could be integrated within an accessible, queryable digital repository (

Slingerland and Sullivan 2017;

Monroe, forthcoming;

Arbuckle MacLeod et al., forthcoming). Entries within the database are structured around “Religious Groups” (a loose term used to describe identifiable shared religious belief or practice),

1 “Religious Places” (e.g., temples, sanctuaries, etc.), or “Religious Texts” (e.g., scriptures, mythologies, votive inscriptions, etc.) labeled as “Polls”. Each entry is created by an established expert in that topic, thus giving authoritative and current interpretations or positions on a particular topic.

2 The DRH, however, does not function as a traditional published resource as its coverage is constantly evolving and expanding as new entries are published within it. As a result, queries on this dataset do not represent a final word on any particular question, but rather can be used to identify patterns in human behavior and belief, and trends in scholarly analysis.

Each entry consists of a qualitative summary of the particular topic, as well as geographic and chronological parameters. The remainder of each entry consists of answers to an extensive list of questions that may be answered “Yes”, “No”, “Field doesn’t know”, or “I don’t know”. Many specialists may be hesitant to commit to a definitive answer on a given topic, and as a solution the DRH presents a flexible model in offering multiple answers for a question, more ambiguous “Field doesn’t know” responses, as well as the (encouraged) opportunity for extensive comments, citations, and the ability to restrict particular answers to discrete periods of time, geographical units, or subsets of society. The ability to code such positionality on topics is ultimately one of the more powerful tools of the database, as these responses may be quantified and queried across time and space to compare or contrast responses in varying contexts. Entries in the DRH are archived by the University of British Columbia, and receive DOI’s for convenient citation.

The DRH can be incorporated into teaching in a variety of ways.

3 For example, the “Browse” feature (

https://religiondatabase.org/browse/, 15 March 2022), allows for straightforward lexical queries to search for entries on the basis of topic, region, or broadly shared characteristics (tags).

4 This feature provides access to the full detail of entries, including their bibliographies and links to external resources. Similarly, and the focus for the following discussion, is the ability to conduct preliminary analysis using the “Visualize” feature (

https://religiondatabase.org/visualize/, 15 March 2022). This feature allows for more specific queries to be made surrounding the various questions associated with entries in the database.

5 The scope of the query can likewise be confined by geography and chronology and visualized in graph or table views for more efficient analysis.

Sample Query: Pantheons and High Gods

The following discussion and subsequent case studies build upon the experiences of the authors in teaching aspects of ancient (and modern) religion in the classroom, in predominantly area-studies disciplines. They demonstrate how the DRH may be used as a pedagogical tool and dataset. For example, in a classroom examining the human understanding of and nature of supernatural entities in the pre-modern world, the characteristic features of certain pantheons may be discussed together with their (changing) hierarchies. In such a context, classroom questions might include: What are human conceptions of supernatural beings? Are they hierarchically organized? Do they monitor human behavior? Are they moral? What drives the promotion of a certain deity over others? Such questions invariably draw into discussion the concepts of “polytheism”, “monotheism”, and the oft-assumed linear trajectory linking the two, that is often led by a priori assumptions that prioritize western (Christian) perceptions of increased morality in the latter (

Purzycki and McKay 2022;

Zwi Werblowsky 2005;

Ludwig 2005;

Murray 2015, p. 110;

Seymour 2011, p. 786;

Ellwood and Alles 2006, pp. 299, 346–47;

Amore and Hussain 2015, p. 4).

It is not just the field of religion that grapples with such concepts. Many other disciplines have lately pursued similar questions, particularly concerning the origins of Big/High/Monotheistic gods, their relation to morality, and their overall impact on human societies (e.g.,

Purzycki et al. 2022). As a test for the following discussion then, we might focus on the concept of high gods, a topic that has seen much recent discussion. For example, from the field of Psychology, Ara Norenzayan has argued that it was the human ability to conceive of supernatural beings, and the perception of omniscient and interventionist “Big Gods” in particular, that led to increased forms of cooperative and pro-social behavior, ultimately leading to larger cooperative and urban societies (

Norenzayan 2013).

6 In anthropology, cultural evolution, and the sciences, recent studies have similarly focused on the relation between belief in moralizing “high gods” and human cooperation, focusing on certain ecological situations or contexts of resource stress (

Ember et al. 2021;

Skoggard et al. 2020;

Botero et al. 2014). Likewise, sociological and historical examinations have argued for unique outcomes of monotheism, namely its ability for rapid, exponential growth, and long-lasting durability amidst outbursts of violence (

Stark 2001; see also

Armstrong 1994,

2000). As a final example, various area-specific disciplines have examined ancient historical and historicizing data in an attempt to identify the “earliest” monotheisms, as seen in arguments surrounding Akenaten’s Atenist movement in ancient Egypt, and the Hebrew Bible narratives concerning the rise of the god Yahweh in the southern Levant (

Hoffmeier 2015;

Assmann 1995,

2008;

Smith 2001). Many of these studies, however, have relied on incomplete or biased data that has distorted understandings of moralizing deities and their origins (

Purzycki and McKay 2022;

Beheim et al. 2021), an issue that the DRH seeks to address by avoiding monotheistic bias and varied colonialist assumptions.

In engaging with broad questions across multiple disciplines then, a pedagogical tool such as the DRH is useful for its access to digital data that covers a wide range of contexts from which the above questions may be problematized. To access data in the DRH by which the concept of high gods, morality, and related themes may be tested, the

Beliefs → Supernatural Beings portions of the entry polls are of interest, particularly the portion of the polls that denote whether “

A supreme high god is present”. This question would relate to a variety of scenarios in which numerous deities and hierarchies among them could be explored. To create a query and use the visualization feature then, it is necessary to match the terminology of the database. Thus, “

A supreme high god is present”

7 can be entered into the search bar. Then, the “Filter” may be used to modify the geographical and chronological parameters, with the option to restrict the search to specific polls, entry sources, and data sources, if desired.

8 To illustrate, the following example searches: “

A supreme high god is present”, using the chronological scope of 5000–0 BCE in an attempt to focus on entries that are largely “pre-Abrahamic”. The results of this particular query, at the time of writing, captures results from 167 different entries (

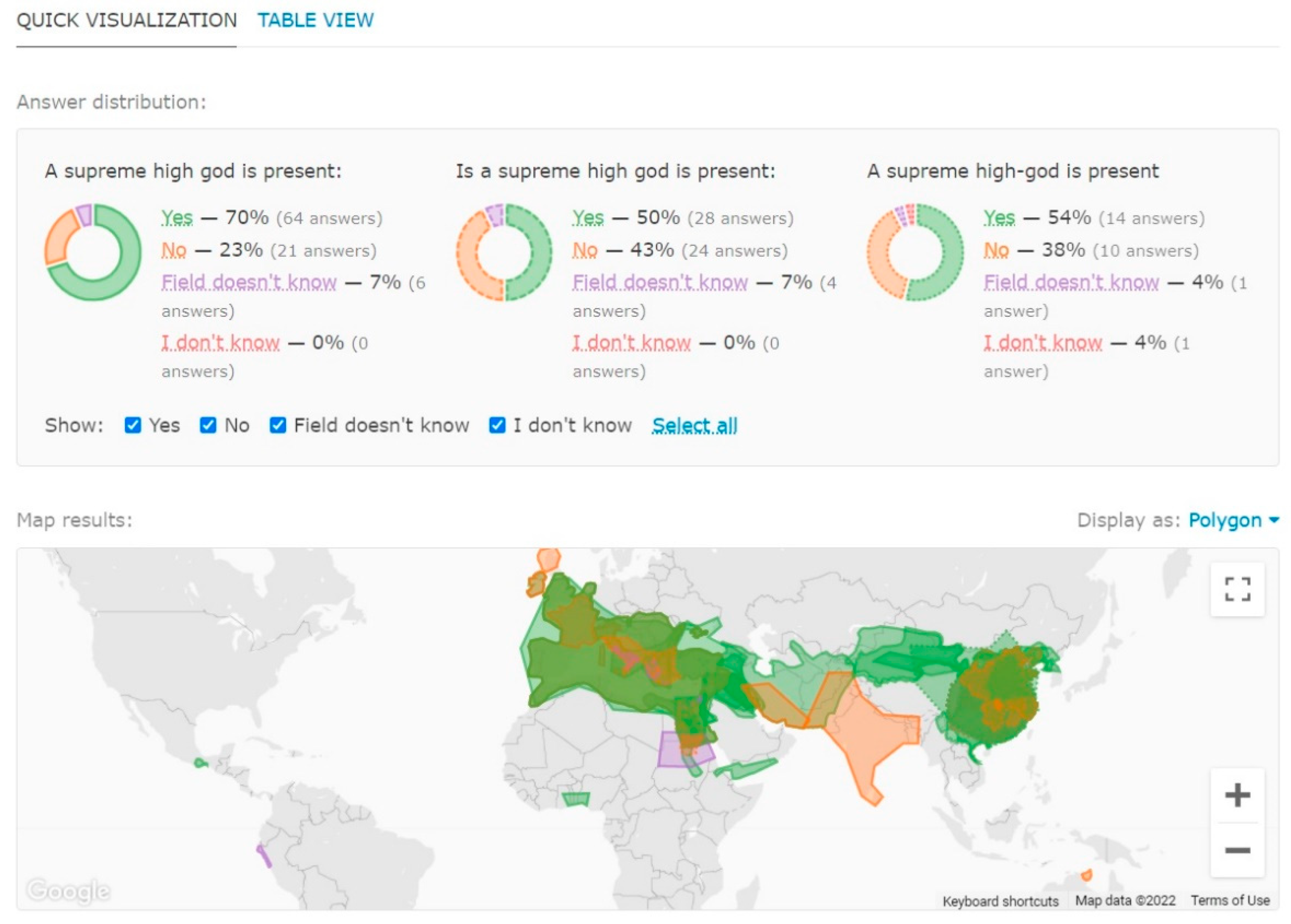

Figure 1):

9Readers will notice that geographic coverage is currently strongest for the Mediterranean Basin, and southwestern, southern, and southeastern Asia, particularly for the pre-modern world as is the focus of this query. While new initiatives at the DRH are moving to emphasize the pre-modern Americas and Africa, it bears emphasis that use of the data necessitates consideration of the strength of coverage for individual regions and periods of time. Nonetheless, the query yields a vast range of results.

Perhaps initially of note to students is the high number of positive responses to the question concerning “high gods”, particularly when the chronological scope pre-dates Christianity and Islam. Positive, “

Yes” responses are featured in a majority of the “Group”, “Place”, and “Text” polls (ordered left to right in

Figure 1). Such responses would immediately challenge the above outlined assumptions concerning “polytheism”, particularly when the wide geographic ranges of positive responses are noted. The visualization itself requires both additional follow-up and likely the need for terminology that extends beyond a simplistic “monotheistic/polytheistic” binary.

One of the most important caveats in using the DRH to create such inquiries is that the DRH does not provide a static dataset, but is rather continuously expanding. Thus, any graphical quantifications of particular questions must be understood as only representative of the database at that moment in time. The query results might indeed highlight particular trajectories in history, but it is necessary to analyze the size and nature of the dataset to ensure that any broader takeaways are contextualized within the scope of available data. As such, the primary output of inquiries such as the above ought to emphasize the qualitative nature of the data, using the DRH and particular entries as resources themselves, but also as launching pads from which to explore themes in greater detail. Similarly, the link to these queries may be included in publications, which when accessed will automatically update to include the latest dataset.

To explore entries in greater detail the “Visualization” may be shifted to a “Table” mode that allows for a more detailed overview of individual entries and scholarly opinion as captured within notes. The table likewise provides links to the entries themselves where greater detail and bibliographic resources may be explored (

Figure 2):

The table reveals diverse responses across regions and time periods that can be filtered, restructured, and sorted to prioritize different aspects of the data. Likewise, the table view can be used to access the comments on a particular topic, in essence providing a small encyclopedia-style collation of a range of scholarly interpretations and relevant references. Overall, the table view allows for further insight and nuance into the complexities and “messiness” of particular contexts. In the above example (

Figure 2), beyond a range of responses and explanatory notes, it is notable that certain regions offer both positive, negative, and ambiguous responses, representing variant chronological and sub-regional contexts, as well as competing scholarly interpretation. Ultimately then, the broad visualization (

Figure 1) and table (

Figure 2) demonstrate the need to consider more refined geographic and chronological inquiries. In the following sections, the questions of supreme gods and their function across time and space are explored using the DRH to apply and ultimately test this question within different regional and chronological contexts.

3. Case Study 1: Ancient Near East

To use the DRH as a test case for exploring religious patterns and the characteristics of high gods in the ancient Near East, the database was queried for the questions as presented in

Table 1, using the terminology employed within the database. The goal of these particular questions was to identify characteristic features of the perceptions of high gods for the ancient Near East from which more nuanced inquiry could be based. The parameters for this query consisted of a geographic delineation that included the Levant, Anatolia, Mesopotamia, Western Iran, and northern Arabia, and a chronological scope of 5000–0 BCE.

The results of the query (

Table 1) reveal interesting insights and provide a means by which to discuss conceptions of divine and supernatural agents in the ancient Near East more generally. First, with regard to the broad outline of the query responses, it is notable that the presence of a supreme high god was positively noted for a strong majority of expert responses. Of these positive affirmations, over half were noted as related to “sky” elements, which encompasses a variety of related aspects (e.g., weather, solar, etc.). A further strong majority identified anthropomorphic tendencies in human perceptions of these gods, and lastly, only a minority of entries identified that adherents were likely to view this deity as unquestionably good. Building from these general observations, we can next explore individual regions and contexts, taking into account geographic and chronological differences.

To explore these concepts further it is necessary to emphasize that our understanding of “religion” in the ancient Near East is structured by available data, namely material culture and architectural remains, but especially textual sources. Without diving into the methodological challenges of associating material culture with “religion”, it is worth emphasizing that the latter dataset—textual sources—is utilized for the majority of conceptions of divine entities, their nature(s), and organization. This means that for particularly early, prehistoric contexts such as the Neolithic, the conception of—and even the presence of—supernatural agents remains hotly debated (

Cartolano 2022). With inscriptional and textual sources in the later periods, however, a more complex portrait of the divine realm and agents emerges, though, at their foundation, these sources need to be analyzed in relation to the contexts that produced them. In other words, certain texts or religious centers often reflect as much about the social and political agents producing them as the divine agents they discuss.

In the Levant, one of the richest textual datasets originated from the Late Bronze Age (1550–1150 BCE) city-state of Ugarit. The mythological texts excavated there discuss a divine pantheon in part organized through kinship ties, with a patriarchal deity El at the head. Entries within the DRH from Ugarit indeed describe El as the “supreme high god”, existing in the distant heavens, and anthropomorphized in nature (

Thompson 2021).

From the texts at Ugarit, we also witness an interesting phenomenon, namely the rising importance of deities beyond El, including a younger storm god—Ba‘al (

Coogan and Smith 2012, pp. 97–154). Indeed, in the subsequent Iron Age period, the transregional rise to prominence of younger storm deities has been argued as associated with the concurrent massive socio-political shifts taking place, in effect, a kind of crisis of faith in an older system of belief and practice (

Coogan and Smith 2012, pp. 104–5). The newly prominent storm gods of the Levant are frequently referred to as Ba‘al, Hadad, Adad, or other variants thereof, with this type of storm-god rooted in distinct landscapes with regional temples, and often understood to have their homes atop lofty mountains (e.g., Ba‘al of Zaphon). One of their titles is “rider of the clouds” (

rkb ʿrpt/רכב בערבת) exemplifying their sky and storm attributes together with other weather descriptors (e.g., thunder, lightning) or divine warrior aspects (

Schwemer 2007;

Coogan and Smith 2012, pp. 97–109).

Across the Levant during the Iron Age (1150–550 BCE) we see this pattern emerging, where certain deities were elevated across the region, with major temple sanctuaries associated with the ruling elite of these small kingdoms. Representing a large shift from the now more distant deity El, these newer gods were often understood as of the next generation, nearer the human realm, and often closely related to weather/storm elements and bearing the entrapments of divine warriors. For example, such a situation may be described for the kingdom of Yādiya (Sam‘al) with Hadad most prominent (

Hogue 2022), the deity Yahweh in Judah and Israel (

Peters 2022;

Flynn 2019), Milkom in Ammon (

Tyson 2022), and Qos in Edom (

Danielson 2020,

2021). Most often, these deities were worshipped together with a divine female consort (often Asherah or Astarte), amidst a broader variety of deities. In these contexts, sacrifices and offerings were given to the gods largely as a means by which to placate them, as the gods were not necessarily good nor bad, but required placation for favorable human outcomes.

By the end of the first millennium BCE in the southern Levant, Judaism and later Christianity attest to complex shifts in religious thought and practice, namely with the primacy and exclusionary focus on a single deity. These shifts are well-identifiable in the DRH dataset, especially with entries centered on Second Temple period Jewish movements where perceptions of a non-anthropomorphic, unquestionably good supreme deity become near consensus among the communities and texts associated with the Essenes of Qumran (

Jokiranta 2019;

Bay 2019b;

Elliff 2022;

Shirav 2022), the Pharisees (

O’Connor 2020a), and Zealots (

O’Connor 2020b), with the Sadducees (

Matson 2020) presenting similar perspectives, albeit not necessarily viewing the supreme deity as unquestionably “good”.

The process of arriving at this point was complex. While the Iron Age kingdoms may have popularized or prioritized certain deities, they certainly accepted a broader variety of gods as legitimate, with their practice trending toward what we may call henotheism, namely an adherence to a particular deity, while recognizing the validity of others (

Yusa 2005, pp. 3913–14;

Danielson 2020, pp. 123–27). In the context of ancient Judah, however, monotheism eventually did appear. In an intriguing argument, the Hebrew Bible scholar Seth

Sanders (

2015) argues that the formation of what is often called monotheism in Israel was a contextually contingent phenomenon—indeed we do not see similar transformations elsewhere in the Near East.

Sanders (

2015) contends that prominent deities among different social groups were adopted by the ruling class, which resulted in the convergence of a regional deity, the most popular deity among the populace, and the promotion of the same god by the ruling dynasts. This process led to what we might call a “pantheon reduction”, whereby a single deity outlasted the popularity of others. With the push for a maintenance of identity amidst extreme crises (i.e., the Babylonian exile), Yahwism shifted toward the more monotheistic form with which students may be more familiar (though see

Hayman 1991).

Similar patterns (though not resulting in “monotheism”) can largely be identified in the surrounding regions, though each possessed their own unique nuances. From the Anatolian context, the deities are linked to regions and affected by various socio-political shifts. For example, during the Late Bronze Age, amidst the broader pantheon of the New Kingdom Hittites we see the elevation of, and importance placed on the role of the storm god Teššub (

Leonard 2021), also associated with the sun goddess Hebat (

Bilgin 2021;

Schwemer 2008).

In Mesopotamia, similar to the Levant, we see a sky god An(u) originally at the head of the pantheon become more distant, and regionally specific deities begin to be emphasized, in part, with political changes. In the decentralized Early Dynastic period, for example, Kathryn Kelley identifies the god An(u) at the head of a broad and complex pantheon (

Kelley 2022), whereas in the subsequent, centralized Sargonic Empire, Nicholas Kraus emphasizes the difference across regions in terms of which deity is understood as most important, highlighting the regionalized nature of religious centers in urban contexts (

Kraus 2020). In this way, human interaction with the Mesopotamian pantheon can be viewed as a constellation of religious centers based in different urban centers across the region. Furthermore, we see shifts in the pantheon occurring in relation to politics. For instance, Ashur, the patron deity of the city of Assur rises to the head of the pantheon when Assyria does (

Nation 2022), whereas Marduk of Babylon fulfills a similar role in periods when Babylon is preeminent (

Seymour 2011, p. 778).

On the basis of the ancient Near Eastern data then, for pedagogy, the DRH provides a rich array of responses to questions concerning the nature of high gods. While a clear linear trajectory toward monotheism with the rise of the Abrahamic faiths may initially be assumed, the data show this situation to be more complex and messy. Similarly, the ability of the DRH to code multiple and ambiguous responses to questions can highlight differences in positionality among scholars as well as lacunae in our ability to understand antiquity. In the classroom, access to a digital tool that affords these opportunities, with direct links to entries and resources on the social groups, places or texts under study, is a valuable tool.

4. Case Study 2: Ancient Egypt

In terms of ancient Egyptian religion, the question of whether there was a supreme high god at any one point is a matter of controversy—whether this should be characterized as a form of monotheism even more so (see

Dunand and Zivie-Coche 2004, pp. ix–xi). The debate surrounding this issue was discussed in detail by Erik Hornung in his

Conceptions of God in Ancient Egypt: The One and the Many (

Hornung 1982), in which the author highlights the difficulties with using modern terms, and how easily our own beliefs and biases can shift our perception of past cultures and practices. Most Egyptologists today would agree that such a discussion must be contextualized. Specific temples were dedicated to specific gods, in which cases these deities were often addressed as high gods of the space, though almost never excluding the existence of the rest of the pantheon. In other contexts, multiple gods are referenced concurrently, without suggesting an inherent hierarchy. In certain periods the available evidence also suggests that certain gods rose to prominence. In cases where there is ambiguity there is also considerable scholarly disagreement. In the following, we highlight each of these different contexts using examples from entries available in the DRH, thereby demonstrating the different approaches to answering the query, “

A supreme high god is present” in ancient Egypt.

For much of Pharaonic history, from prehistory through to around 1550 BCE, or the end of the Second Intermediate Period, most scholars seem to agree that there was no supreme deity at the head of the Egyptian pantheon; however, there were regional gods and cults dedicated to specific deities, in which contexts certain gods would have taken priority of worship. In the Old Kingdom (ca. 2670–2168 BCE), for instance, a number of solar gods, particularly Re and Horus, were significant and dominated certain solar-focused temples. The cult of the king was also the focus of much ritual activity, and by the end of this period, the chthonic god of the dead, Osiris, also had a prominent position in funerary monuments and tombs (as reflected in entries

Arbuckle 2021; and

Smith-Sangster 2021). In the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2010–1650 BCE), Osiris became even more significant, though other local gods such as Montu (also a god of war) were dominant in some contexts, including the temple of Montuhotep II (as noted in

Praet 2021).

By the beginning of the New Kingdom (ca. 1550 BCE), however, the god Amun, or more specifically his solar form, Amun-Re, began to be worshipped as the “king of the gods”, giving the impression that state religion at this point could be characterized as henotheistic. This is particularly visible at Karnak Temple, which was dedicated primarily to Amun-Re, though a number of other gods had chapels within the larger temple area (

Sullivan 2022). Amun-Re would remain dominant throughout the New Kingdom (ca. 1550–1086 BCE) and Third Intermediate Period (ca. 1086–664 BCE; as reflected in

Rummel 2021;

Souto 2021;

Taylor 2021), with the exception of the Amarna Period. The Amarna Period (ca. 1350–1320 BCE), refers to a time frame of approximately 30 years, when the king Akhenaten promoted the god Aten as the one true god, denying the existence of other gods, and actively erasing the image of Amun-Re. While a strict reading of the textual evidence would therefore suggest that Amarna culture was truly monotheistic, in practice, archaeological evidence found even within private houses at Amarna suggests that individuals continued to worship other deities (as reflected in

Arbuckle and Schneider 2022;

Arp-Neumann 2021).

In the Greco-Roman Period (ca. 332 BCE–395 CE), there continues to be disagreement about whether the religious system should be seen as polytheism or henotheism. The god Serapis, who shared qualities with the Egyptian god Osiris and the Greek god Zeus, among others, is sometimes viewed as the dominant god in the pantheon at this time (as noted in

Ismail 2021); however, other scholars believe that he was viewed as one among many (

Climaco 2021).

Answering whether “

A supreme high god is present” in ancient Egyptian religion is therefore a very complicated and context-specific query. It can be particularly difficult for students to understand that there can be so much controversy about a seemingly simple question. While teaching an Ancient Egyptian Religion course, the visualize feature can be used to help discuss this topic with the class. This tool helps to quickly demonstrate that this question is contentious, and shows how scholarly responses change based on the time period in question, and often at the specific place as well (

https://religiondatabase.org/visualize/3007/, accessed on 30 March 2022). By switching to the Table View, individual comments help to elucidate how the scholars have interpreted the question and understood Egyptian beliefs in the specific context, as demonstrated in

Figure 3. Beginning with this visual also clearly demonstrates that Egyptian religion is not static—a view that is often transmitted in overview works such as introductory textbooks and readings. It is also very useful to be able to start with the visualization at the beginning of the term during an introductory lecture, and then return to individual entries as these topics arise throughout the term.

5. Case Study 3: Ancient Greece

From the end of the Early Iron Age (ca. 750 BCE) until the advent of Christianity, there is little doubt as to whether a supreme deity at the head of the Greek pantheon existed. Despite the numerous local and regional manifestations of the religions of the ancient Greeks, the supremacy of Zeus was unquestionable. This, however, was not the case for the earlier periods. The mainland Greek forebears of the Greeks, the Bronze Age Mycenaean civilization, for example, had a polytheistic pantheon with some onomastic continuity to later Greek deities as is attested in tablets written in the Mycenaean script called Linear B (

Nilsson 1971). For example, names of deities familiar in later Greek such as

di-wo (“Zeus”),

e-ra (“Hera”),

po-se-da-wo-ne (“Poseidon”), among many others, appear in various Mycenaean tablets. The configuration of the pantheon, however, seems to have been significantly different from later Greek religion (

Rutherford 2013, pp. 270–71); Poseidon’s name appears more often than Zeus’ and the familial relationships between the various deities seem to differ from later periods. Zeus (

di-wo), for example, had a female counterpart (

di-u-ja). The only role that these deities have in the Linear B tablets, however, was as the recipients of offerings, and so the complex mythologies from later periods do not yet feature this early.

Although the Psychro Cave, a site that served as a Minoan cave sanctuary, was regarded as the birthplace of Zeus from the Classical period onwards, the existence of a supreme high god in Minoan Crete is even more enigmatic, as the Minoan scripts have not been deciphered and links of continuity between Minoan religion and later Greek religion are difficult to prove. Sir Arthur J. Evans, the excavator of the major Minoan center of Knossos, proposed a deceptively coherent narrative of what he assumed to have been the characteristics of Minoan religion (e.g., aniconism in early Minoan cult, its animistic nature, and the supremacy of a Minoan Mother Goddess), none of which have been demonstrated with certainty (

Marinatos 2013). Evans originally claimed that a powerful nature goddess was the supreme deity of the Minoans, going so far as to suggest that Minoan religion may have been monotheistic as he could not originally discern whether figural female representations pertained to one or multiple goddesses.

Marinatos (

1993, pp. 165–66) argues against this reductionist approach, choosing instead to place the emphasis on the essence of the deity (as a powerful nature goddess) rather than whether there was one or multiple goddesses. She compares the case of the Minoan goddess with that of ancient Egyptian deities, in which deities sometimes took priority in worship (closer to henotheism), fluctuating by region and time period (

supra). She further corrects earlier assertions that male deities were rare or unimportant, citing numerous instances in which they are presented as showing mastery over nature. Perhaps the decipherment of the Minoan scripts might one day elucidate the existence of one or more deities playing a supreme high role in Minoan religion, but that remains a

desideratum. We should, finally, also stress that neither the Minoans nor the Mycenaeans formed a unified system and we should expect the same lack of uniformity in their religious beliefs and practices. Questions concerning a supreme high god in the DRH entries on Minoan religion, therefore, largely consist of “

Field doesn’t know” (e.g.,

Dewan 2022).

Although literacy would disappear in Greece after the Late Bronze Age collapse, the adoption/adaptation of the Phoenician alphabet during the Early Iron Age saw widespread continuity of the majority of deities previously attested in Linear B, most of whom would become revered by all Greek communities. However, a number of the divine names attested in Linear B did not survive into historical Greek periods, perhaps because their cult in the Bronze Age was too localized (

Coldstream 1977, p. 329), but many did. This onomastic continuity, however, did not necessarily imply cultic continuity, and most of the material configurations of cult evident in the Greek world at the end of the Early Iron Age did indeed seem to have been innovations of the period. These innovations include a shift of investment from funerary and domestic religion to public sanctuaries, an increasing common knowledge in the appropriate material articulations of a sanctuary, the types of votive offerings acceptable at these spaces, and the proper rituals and behaviors in relation to the divine (

Mazarakis Ainian 2016, pp. 24–25). Despite the fact that the Greek world was expanding beyond mainland Greece and Asia Minor, and the fact that many Greek communities were hostile towards each other, the larger sanctuaries (e.g., Delphi, Olympia, etc.) began to serve as a unifying factor, and although there was great regional and local diversity in the religious beliefs and practices of the Greeks, a number of commonalities arose in the ways in which they conceived of their gods (

Mitchell 2007, pp. 30–32;

Morgan 2003, pp. 14–33;

Whitley 2001, pp. 134–64;

Coldstream 1977, pp. 367–69). It is within this context that the dominance of Zeus in the Greek pantheon developed.

Although no Greek deity was wholly omnipotent, omniscient, and omnipresent, Zeus comes the closest to being all-powerful (

Larson 2007, p. 15). By the beginning of the Archaic period (750–480 BCE), virtually all Greek communities acknowledged Zeus not only as the sovereign king of the gods but also the progenitor of all humans, constantly referred to by Homer as “πατὴρ ἀνδρῶν τε θεῶν τε” (“father of men and gods”). He was conceived of as a lightning-bearing sky-god to whom people prayed for rain, as well as presiding over civic, social, and familial hierarchies. In an apparent contradiction, however, he is also often worshipped as a chthonic god in the form of a snake in his role as the protector of private property, bestower of blessings, and the maintainer of social norms. As the Greek world was never a unified ethnic or political entity, many regions placed a greater local importance on specific deities (e.g., Athena in Athens), though the position of Zeus as supreme was never in question. Whether Zeus was unquestionably good is another matter, as his portrayal in myth as a philandering husband is not necessarily always reflected in his cult. Some philosophers, such as Plato, rejected the notion that the gods could have been subject to human flaws and passions but were instead perfect sources of divine order. In such cases, students and educators will notice that entries in the DRH display disagreement in whether “

the supreme high god is unquestionably good” (e.g.,

Ieremias 2022;

Wiznura 2021), prompting opportunity for further discussion and analysis.

The picture becomes more complicated as the conquests of Alexander the Great expand the Greek world even further. The resulting globalized Greek world in the Hellenistic period (323–31 BC) and subsequent Roman domination of the same territories, was a formative matrix for the exchange of ideas between the Greeks and the populations of the territories they now occupied (

Mikalson 2007). In terms of religion, there was constant tension between local traditions and international trends, as different communities and political powers demonstrated agency in which cults they resisted and which they adopted/adapted (

Kearns 2015).

Many communities and polities accepted foreign cults whose deities could also be seen as supreme high gods. Maintaining or rejecting their status as supreme high gods, however, was the prerogative of the communities that adopted them. This includes Kybele who was imported from Phrygia in the Late Archaic period but whose cult became especially popular in the Hellenistic period. Her Anatolian origins are difficult to trace but it is possible that she came from a tradition of Anatolian mother goddesses who acted as a sovereign over nature (

Roller 1999). Within a Greek context, she was fully adopted into the family of Zeus and usually syncretized with his mother, Rhea; however, she seems to occupy a special place in cult that would qualify her as a supreme high god in her own right. The

Homeric Hymn to the Mother of the Gods (7th/6th century BCE), for example, refers to her as “μητέρα…πάντων τε θεῶν πάντων τ᾽ ἀνθρώπων” (mother of all gods and all humans), similar to Homer’s descriptor of Zeus. In the case of Isis, although a minor Egyptian deity prior to the New Kingdom, she became increasingly important in the second millennium BCE, and seems to have attained the status of supreme high god in the Hellenistic world, as Isidorus’ four surviving hymns (1st century BCE) refer to her as “queen of the gods”, “ruler of the highest gods”, etc. (

Vanderlip 1972). He also ascribed roles to her, previously unattested in Egyptian religion, that give her dominion over every aspect of life and syncretizes her with several Greek goddesses. The Greeks also often reinterpreted the supreme high gods of other populations and syncretized them with Zeus (e.g., Zeus-Amun), as they also did for other deities.

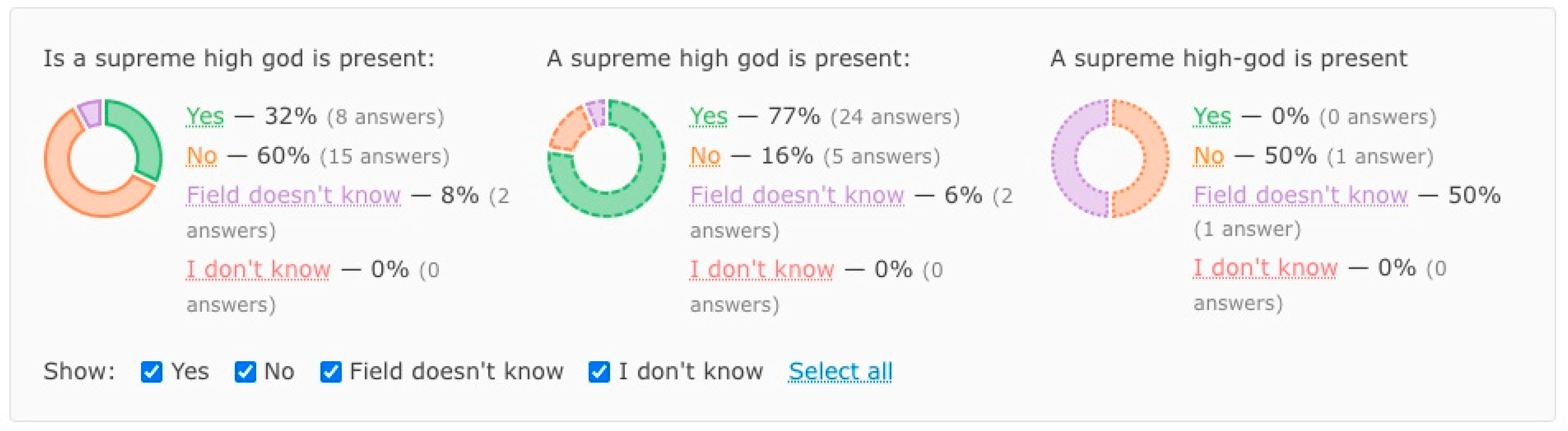

Such are the problems faced by experts answering whether a supreme high god is present in an ancient Greek context. Entering a start date of 3000 BCE for the query and an end date of 99 CE with Mainland Greece, Southern Italy and Sicily, and Western Anatolia as the geographical bounds, one sees the following picture (

Figure 4).

11 From the Archaic to Classical periods in a mainland Greek context, a “

Yes” answer can be fairly secure in Religious Group polls for mainstream Greek cults, and sometimes “

No” in Religious Place and Text polls if the expert interpreted the question as referring only to the place/text as opposed to the religious systems to which those places/texts belong. A “

Yes” response can be controversial in Bronze Age prehistory, in colonial contexts, and in the wider Hellenistic world where we enter into the gray areas of simultaneous “

Yes” AND “

No” answers, as well as “

Field doesn’t know”.

6. Case Study 4: Chinese Religion

When turning to the long history of “Chinese religion” (meaning the traditions of the Yellow and Yangzi Rivers) from the 2nd millennium BCE to the present, a search query regarding supreme high gods immediately reveals a wide variety of different deities that can be labeled as such.

Many of these figures are associated with different, often retrospectively created, traditions. Heaven (

tian 天), for example, is associated with Confucianism, The Lord on High (

shangdi 上帝) with Shang and Western Zhou court religions, the Buddha with Buddhism, Laozi 老子 with Daoism, Allah with Islam, and the Trinitarian God with Christianity (

Knapp 2021;

Lu 2022;

Sun 2021;

Assandri and Hamm 2022;

Zhang 2021;

Chen 2022a). This list does not even include deities associated with lesser known traditions that began in the 19th century, such as the cult of Dingxiang Wang 定湘王 or the Eternal Venerable Mother (

wusheng laomu 無生老母) in the religion of Yiguan Dao 一貫道 (

Schluessel 2022;

Chen 2022b).

A closer look, moreover, reveals that this diversity persists even within ostensibly unified traditions. Laozi, for instance, was worshipped in only certain branches of Daoism, particularly north of the Huai river, while the Heavenly Worthy of Primordial Commencement (

yuanshi tianzun 元始天尊) was prominent in the Daoist traditions of the Yangzi River (

Assandri and Hamm 2022). Conversely, the identities of Heaven and Shang Di often blur together and cut across the divisions of ostensibly separate traditions (

Knapp 2021;

Poli 2022;

Fodde-Reguer 2022).

The impression, therefore, is of a wide array of interacting and, at times, competing high gods within a highly diverse region whose variety and richness has only increased over time. This picture becomes even more complex when we take into account divergent scholarly efforts to interpret and apply analytical terms such as “supreme high god”. For example, when writing about the Buddhist text,

Cheng Weishi Lun 成唯識論, Ernest Brewster remarks:

There is no supreme high-god according to the Buddhist cosmological model inherited by the Cheng weishi lun. The gods of the Hindu pantheon are relegated to the status of mortal beings within saṃsāra, the cycle of transmigration.

Brewster’s point here is ontological. Within Buddhist theories of the cosmos, gods do exist (a legacy of its South Asian origins), but they have relatively little status and the Buddha himself is not a god but an enlightened being who was once mortal.

When writing on Xuanzang’s Yogācāra Tradition, however, which is the Buddhist tradition organized around the

Cheng Weishi Lun, Guanxiong Qi states that there is a supreme high god and comments that “Xuanzang’s Yogacara tradition is highly engaged with the Maitreya worship” (

Qi 2020). Qi’s claim here appears to be based more on commonalities of practice. Although the Maitreya Buddha is not a god in the ontological sense indicated by Brewster, the worship of Maitreya justifies use of the appellation “supreme high god”.

In this case, neither author can be said to be incorrect as they are both identifying empirically accurate aspects of the same tradition. Their disagreement is a product of how they interpret and apply the same analytical concept. In doing so, they are reflective of ongoing debates in Asian Studies, and religious studies more generally, over how to apply analytical categories cross-culturally, as well as the validity of doing so.

While these debates are of crucial importance, if they are confined only to contemporary scholarly circles, they can slip into Durkheimian power dynamics that exclusively position adherents or “believers” of a religion as the objects of study whose beliefs are unmasked by the disengaged analyst. In such a formulation, theory is only applied in one direction: by scholars who stand outside of the interpretive frameworks that they wield (

Seligman et al. 2008). What makes the DRH a powerful tool in addressing these types of issues is the rich empirical data that it provides. Closely attending to that data can help break down the power dynamics described by revealing that similar debates were never absent from the traditions being studied.

In the case of Heaven, certain early Chinese texts (like the

Mozi 墨子) present it as an anthropomorphic deity that rewarded and punished individuals based on their behavior (

Poli 2022). Contemporaneous texts, however, like the

Zhuangzi 莊子, present Heaven as a synonym for an impersonal, natural order (

Fodde-Reguer 2022). In presenting these contrary portrayals, early texts were not simply offering different beliefs, they were engaging in rigorous debates over how to understand the world.

Similarly, when new traditions encountered one another, such debates resulted in theoretical innovations. To give but one example, Chongxuan Daoism accepted certain Buddhist claims about the underworld but reinterpreted those claims according to pre-existing Daoist notions of bureaucracy. At the same time, Chongxuan theorists made use of the South Asian logical technique of

tetra lemma (the four-fold negation) to unify distinct Daoist high gods and integrate Buddhist claims regarding the essential nature of compassion (

Assandri and Hamm 2022).

When used as a pedagogical tool, therefore, the DRH can not only provide students with information about different traditions, but its detailed data can also be used to undermine the privileging of theoretically-minded analysts over the believers who those analysts study. In place of this empirically inaccurate dualism, it can help students to recognize that, in studying Chinese traditions, they are engaging in similar interpretive work as the adherents of those traditions. This, in turn, can help students to critically reflect on the frameworks that govern their own interpretations and so pave the way for them to consider the sophisticated texts of China as not simply the objects of theory, but also sources of theory.

7. Case Study 5: Mesoamerica

In the case of ancient Mesoamerica, the DRH is currently working on expanding entries on religions from the many cultural groups that lived and thrived in a diverse range of environments in what are now the modern-day countries of Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua, and northern Costa Rica. Looking at the current DRH entries, it is possible to make use of the DRH for pedagogical purposes by comparing two separate entries on the same religious group. In this section, we illustrate the case of the Zapotec or

Ben ‘Zaa (The Cloud People), who lived in the Oaxaca Valley of Mexico since 250 CE and who continue to live in the present-day State of Oaxaca, Mexico. “Entry A” (named as such for the purpose of this discussion) covers the religious traditions of the Zapotec people during the Classic period (250–850 CE;

Feinman 2019), while “Entry B” incorporates Zapotec religious traditions from the pre-Columbian, Colonial, post-Colonial, and contemporary periods (2000 BCE–2022 CE;

Stoll 2022).

Even though both entries cover the same religious group, there are marked differences between them. In “Status of Participants”, for instance, Entry A includes the elite while Entry B includes the non-elite (common people), suggesting that group membership in this religion has changed over time. A second example of a shift through time within the Zapotec religion is the use of ball courts as part of the religious architecture present at Zapotec archaeological sites (e.g., San Lorenzo, La Venta). The ball game was used for ritual purposes across ancient Mesoamerica (

Aguilar-Moreno 2015;

Blomster 2012), and it was indeed the case for the Zapotec during the Classic period; however, the ritual ball game (and hence ball courts) is not included as part of the Zapotec religious traditions in contemporary times. A third example of a clear difference in religious practices between the Classic and the contemporary Zapotec people are their burial practices. The Classic Zapotec, as other ancient Mesoamerican societies, used to inter their relatives in residential tombs underneath house floors and patios (e.g.,

Tiesler 2022;

Overholtzer and Bolnick 2017) in extended or flexed positions. Cremation was also a common practice, which has been associated with the elites in other Mesoamerican religious traditions such as the Mexica, but this is not necessarily the case for the Zapotec. In Entry B, we see a shift from the above burial practices since individuals are buried in an extended position in cemeteries, and cremation is not a common practice anymore. These examples illustrate the changes that can take place over time in a single religious group, which can be very easily compared/contrasted in the DRH. Students can refine their understanding about specific religious groups and evidence the ways in which religion (like other cultural practices) is not static and ever changing.

By comparing these two Zapotec entries, we can also visualize that Entry B provides more in-depth information about several Zapotec religious traditions thanks to the corpus of ethnographic research that has enhanced our knowledge about this religious group. The contemporary research on the Zapotec helps fill gaps in our knowledge about their belief system and moral realism that we are unable to discern from the archaeological record alone. For instance, while there is no sign of Zapotec religious scriptures in the archaeological record (Entry A), there are written and oral scriptures that we now know are part of the Zapotec religion (Entry B). Moreover, while we cannot definitively know of a “spirit-body distinction” present in Zapotec religion archaeologically, in Entry B there is a “spirit-body distinction present” and the example provided to illustrate this is the “Day of the Dead” (Día de Muertos) celebration in which the spirits of the dead return to the living world to communicate with their living relatives. This is indeed a pre-Columbian concept, albeit only discernible by doing ethnographic research and interacting with present-day Indigenous communities that continue to engage in their ancestral religious and cultural practices. Additionally, it is difficult to deduce norms and moral realism from the archaeological record since some human behaviors are not necessarily captured by the material remains left behind by the group under study. From Entry B, we learn that in contemporary times there are clear moral distinctions associated with the Roman Catholic Church and that conventional distinctions are associated with Indigenous cultural beliefs of the Zapotec people.

By comparing the two entries we can visualize the changes in the Zapotec religion that occurred after the Spanish invasion of Mesoamerica and the early colonial influence of the Roman Catholic Church. In pre-Columbian times, there was no “supreme high god present” in the Zapotec religion, but in contemporary times there is a “supreme high god present”, which highlights the influence of Catholicism. We also appreciate the resilience of the Zapotec people in the face of this colonial influence, as “non-human supernatural beings” have been present in pre-Columbian and contemporary times and have deliberate causal efficacy in their religious worldview. As such, these DRH entries provide an avenue for students to discuss and critically reflect on the interactions between Indigenous belief systems and colonial/Roman Catholic traditions, the ways in which these two religious belief systems have become intertwined over time, as well as the ways in which the Zapotec group has resisted the colonial influence and preserved many of their religious and cultural traditions to the present day. All in all, these DRH entries on the Zapotec people illustrate: (1) that religion is fluid and constantly changing, (2) that major changes took place between the Classic and Early Colonial periods, and (3) that certain Indigenous beliefs can effectively resist colonialism, as seen in the examples of Zapotec religious traditions that survived the influence of the Roman Catholic religion.

8. Case Study 6: Late Antique and Early Medieval Mediterranean

When examining the Late Antique and Early Medieval Mediterranean in light of a “supreme high god”, one is, of course, presented with the seemingly monolithic traditions of Christianity, Judaism, and Islam. Within these systems of belief, one would expect to find the answer to the question of whether “

A supreme high god is present” to be answered in the affirmative, in all cases. Entering a starting date of 330 CE for the query and an ending date of 1204 CE,

12 with the Mediterranean and Arabian Peninsula as geographic boundaries, the results (

Figure 5) paint a far more varied picture.

Even though the DRH, at the moment, does not enjoy the same richness of entries related to early Christian, Jewish, and Islamic traditions as it does for Ancient China, Greece, or the Near East, this query captures not only those Abrahamic traditions, but also an important number of mystery cults and other sects that were active in the Mediterranean and Near East during Late Antiquity. This synchronic, and diachronic, diversity is of considerable pedagogical value in introducing students to the dynamic, indeed sometimes explosive, religious atmosphere of Late Antiquity, as well as the variety of opinions on such pivotal questions as the presence of a supreme high god. For example, this query captures henotheistic mystery cults like Orphism (

Dopico 2020), which existed alongside more mainstream polytheistic religious groups like the Demeter cult in Roman Greece (

Bay 2019a), and places them in conversation with evolving Christian sects like the Valentinians and Donatists (

Bonar 2020;

Barkman 2019). For any study looking to compare Early Christianity with other cult activity within the Roman Empire,

13 such information serves as a vital starting point for students and scholars alike. Moreover, in the second pie chart (

Figure 5), corresponding to the Religious Place poll, variety can also be seen in the way the question of “presence” is interpreted, with some scholars

14 clearly taking this to mean the presence *within a given sanctuary* of a single, preeminent deity. This can act as an entry point into discussions with students on the topic of “presence” within Late Antique sacred space.

To focus more specifically on Abrahamic traditions, one can shift the chronological focus of the query to begin in 395 CE, the date of the Theodosian edict which largely ended public and official pagan practice throughout the Eastern Roman Empire.

15The results of this more targeted query (

Figure 6) produce uniform results in only the Religious Text poll, with the Religious Group and Religious Place polls showing the continued existence of henotheistic and polytheistic activity past the official “end” of paganism within the Eastern Roman Empire, including, arguably, groups like the Manichaeans (

Matsangou 2021;

Scibona 2001). This provides a fascinating insight into the dichotomy between official policy and the lived situation on the ground throughout the empire, as well as the different perspectives that may be afforded by textual and archaeological evidence. Notably, any possible discrepancy in future Religious Place and Religious Text entries for this period would be helpful in allowing both students and scholars to target outliers, that is, sects at significant odds with a core tenet of the Abrahamic faiths.

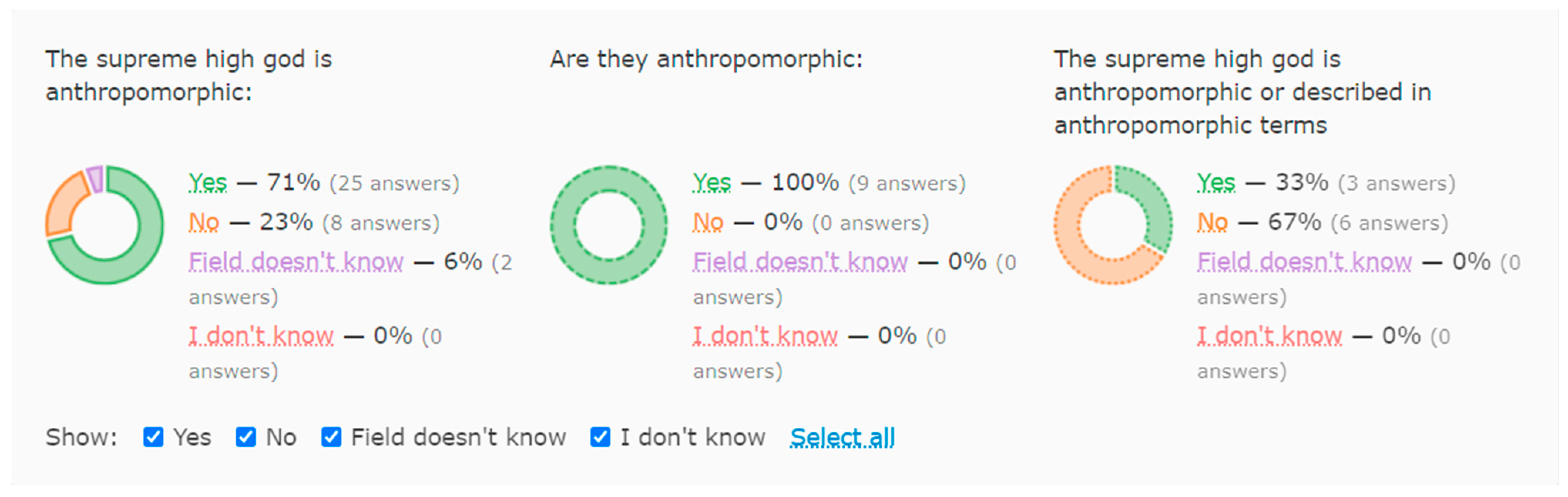

Within Early Christian traditions the source of greatest tension, and open theological conflict, were debates concerning the nature and essence of Christ. Did Christ possess one nature, both fully divine and fully human, a doctrine espoused by Miaphysite groups, or were these two aspects divided in two different natures, the position of the Chalcedonians? Or was Christ even of the same essence as God, a question raised by Arianism? To get at these issues within the DRH, and thus provide a crucial pedagogical tool for any class oriented around culture and belief in the Late Antique and Early Medieval Mediterranean world, we can switch the poll question at the heart of our query to “

is the supreme high god anthropomorphic?” This provides a far more exciting range of answers, complete with detailed notes that start to delve into the principle conundrum facing early Christian theology, and politics, within the Byzantine Empire and beyond (

Figure 7).

16 The discussion could then be broadened to include surprising entries that answer the query in the affirmative, such as that on the Islamic Hanbali school of legal and theological thought (

Prejean 2022).

For a different perspective on the role of religion in the politics of kingdom and empire, we can query “

was the creation of the place sponsored by an external financial/material donation?” and its dependent question “

is this sponsor of the same religious group/tradition as the main usage of the place?” This restricts our entries to the Religious Place poll, of course, but allows for a quick perusal of sites that may have been officially sanctioned by political authorities, and those which were not.

17 These entries provide concrete, material locations with which students or scholars might begin to discuss the role of state actors in Late Antique and Early Medieval religious practice, and the turbulent situation for those sects that found themselves outside of official sanction.

Unfortunately, additional entries on the Late Antique and Early Medieval Mediterranean are required to provide a more comprehensive picture of the attendant religious landscape, but even with the existing entries the DRH is a powerful pedagogical tool for considering different facets of religion, politics, and culture during this period. By examining questions of divine “presence”, anthropomorphism, and state sanction, one can get at core theological and political issues for the Abrahamic faiths in Late Antiquity, their various splinter sects, and pagan cults that existed alongside them. These queries provide students with both top-down and bottom-up information that can act as a starting point for targeted studies at the very heart of a period of crucial transition from Antiquity to a more recognizable world of belief and practice.

9. Classroom Application

As demonstrated in the above case studies, the DRH can be used in the classroom to bring out these nuanced, complicated, and context-specific details about the worship of deities in the ancient and modern world. Publications that are designed as textbooks are often unable to delve into these different discussions, and going through the details of each perspective would result in a truly unwieldy monograph. Moreover, the increasing use of digital technology and resources in online and in-person classrooms (

Ratzan 2020;

Telles-Langdon 2020;

Sinclair 2013) is demonstrating the need for increased digital literacies (

Coker 2020;

Cook et al. 2018, pp. 145–147;

Carlson et al. 2011). There is a real need for digital resources that present the extensive information gathered by previous scholars in an accessible, searchable way, while allowing for critical evaluation and providing opportunity for additional and tangential avenues of inquiry (

Coker 2020, p. 137;

Geertz 2014b, pp. 255–80;

Sinclair 2013).

For the classroom, the DRH provides access to such a repository of information, and through its visualization tool helps to quickly and effectively demonstrate the varied and often conflicting views of scholars. This can communicate to students that not only is it possible to arrive at different conclusions on the nature of worship based on evidence from different contexts, such as worship in different temples, but also that there may be scholarly disagreement in regard to interpreting individual contexts. That so much disagreement exists is often surprising to students. While instructors may be concerned about overcomplicating concepts by bringing up these divergent views, it can be even more confusing for students who come across information during their research that clearly conflicts with what they have been taught. The DRH visuals help to quickly make this point, while the connected entries allow instructors to either go through individual perspectives in more detail as a class, or allow students to browse these details on their own.

When used in the classroom, students seem to find the DRH to be a useful and accessible tool. During the writing of this paper, one of the authors was teaching a course on Religion in Ancient Egypt. Her experience teaching this course and incorporating the DRH as a teaching tool is discussed here briefly as an example. As noted above, during an introductory lecture on the nature of the Egyptian gods, the visualization tool was used to show that there is no clear answer to the question, “

Is a supreme high god present” for all of ancient Egyptian history (

https://religiondatabase.org/visualize/3007/, accessed on 30 March 2022). Specific answers were then explored after looking at the table view, to provide examples of the different scholarly opinions. The students were also shown how to generate their own visualizations and browse through entries so that the DRH could be used for their term (and future) research projects.

The instructor was particularly interested in introducing this resource to the students as the course was online, and students had variable access to libraries. The DRH, therefore, provided all students with a resource that could be accessed and then cited in their term research papers. The demonstration, followed by time to browse through the resource, also served as an engaging activity to help break up the rhythm of more traditional-style lectures and readings. In this case, the demonstration was synchronous, while the browsing and discussion of the resource was asynchronous—though this could be easily adapted for any course format. The instructor’s impression from follow up questions and discussions was that students needed a few minutes of experimentation to understand how to search for and through entries, but even those with limited experience with databases were soon able to locate useful information. Students were pleased to find data on religious history in simplified formats from reliable sources. Their success in finding resources was demonstrated by the fact that a number of entries showed up in citations in student term papers; there were, however, also a few challenges.

It was clear that a few students were frustrated at the variability of entries, which is a challenge for all users. While all answers are useful for visualizing quantitative information, DRH experts frequently do not add comments to explain rather complicated ideas, or only add simple comments. Often this is because they have contributed full comments in previous or parent questions, but not in response to the specific query being examined. The instructor had to explain to students that it may be necessary to read through whole sections of the entry to find explanations. Moreover, as the DRH is a database, experts are only provided the opportunity to record explanations related to specific topics and details; while entries cover hundreds of questions, students and scholars alike are sometimes disappointed that their specific topic is not covered. Such instances present the opportunity to increase student digital literacy in understanding the scope and nature of databases, the opportunities and limitations of particular research questions, and how conclusions are drawn (

Cook et al. 2018;

Carlson et al. 2011). Similarly, large gaps in the database remain, so information is missing for important texts and temples—an issue that will hopefully become less significant over time, as more entries are added. The drawbacks of this resource seem to be related to the need to stress, both in and outside of the classroom, that the database should be seen as a supplementary resource or a place to begin research, but not a complete replacement for more traditional sources. Overall, however, the instructor was very pleased by the student reactions to the DRH.

Future applications of the visualization feature in the classroom plan to divide students into groups to explore selected analytical or methodological questions, with subsequent low-stakes individual activities centered on more self-directed inquiry. Moreover, student digital literacy may be more broadly improved upon through the analysis of curated datasets drawn from the DRH, provided with a series of pre-made lesson plans that allow for explorations of the data and methodology behind digital humanities projects (

https://religiondatabase.org/landing/about/pedagogy, accessed on 30 June 2022;

Arbuckle MacLeod et al., forthcoming).

10. Discussion

Beyond immediate classroom concerns, the above case studies also serve to highlight broader themes and considerations concerning high gods that bear noting. For example, the cases exemplify how perceptions of deities and their own positioning within pantheons and in relation to human societies were never static. They were subject to changes and even radical reformulations as a result of ambitious rulers, geopolitical events or crises, and colonial or intercultural encounters. In particular, times of intense stress or crisis appear to be significant catalysts that precipitate some of the more radical changes in perception(s) of the divine and in practice. Similarly, these changes do not appear to follow any inherent linear trajectory, and in the case of the rise of Abrahamic faiths, can seem to represent more of an accident of history than any culminating moment. Indeed, the deities themselves are complex, and evolve over time and across space, reflecting changes in the sociopolitical agents involved in their promotion and acknowledgement, and intercultural encounters. Such an example is poignantly clear in the rise and evolution of the Egyptian deity Amun, the conflict with the Aten movement, and subsequent evolution into Amun-Re, and later Zeus-Amun.

Similarly, the case studies highlighted regionalization and contextual contingency. Here, it is necessary to emphasize scale, as the contextually refined mode of inquiry employed by the DRH in some instances results in minor deities portrayed as overly important on the basis of the more restricted scale of analysis, whereas from a broader-scale perspective the same deity might be viewed as minor or even inconsequential. Even within regions that have been grouped together by the academy on the basis of broadly shared cultural similarity, there can be a distinct lack of uniformity (in practices or belief) within a fairly restricted geographic region, in addition to tensions between local traditions and international trends. Diversity is well-attested even within supposedly unified traditions.

Yet, somewhat ironically, amidst the diversity and the variant regional traditions, certain shared understandings of the divine may facilitate syncretization and create a vector for meaning and interaction across social or political boundaries (

Tappenden 2016). Such examples include shared shrines to particular transregional deities, or syncretizations between different deities that allow adherents to find meaning in new contexts, seen for example with Zeus-Amun or Qos and Apollo (

Danielson 2020, pp. 162–70). This pattern highlights the role of human interactions, particularly cross-culturally, in shaping and creating change among pantheons and in perceptions of divine agents.

In instances of expansive and deep change such as in the Levant following the Late Bronze Age collapse or in the colonial influence of the Roman Catholic Church in Mesoamerica following the Spanish invasion, new deities (or new understandings of deities) can rise with newly formed social and political entities, with certain characteristics (e.g., control over weather) of newly emphasized deities perhaps reflecting the immediate concerns of communities or external influences. In other instances, ambitious rulers, perhaps also seeking to limit existing religious power structures can seek to effect radical change in religious organization, as seen with Akhenaten in the promotion of the Aten in Egypt at the expense of the powerful Amun priesthood (

David 2007, pp. 69–70, 88–91). Overall, the case studies reveal the complexities inherent in exploring ideas of high gods across time and space.

In all, however, our understanding of the past, and particularly scholarly efforts at cross-cultural comparison, are often limited by our own ontologies and the terminology used in deriving meaning from the past. These challenges must be acknowledged, and our ontologies tested. Modern biases, and indeed the limitations of definitions we create, can risk reifying within the past the concerns of the present, reflecting the strictures of present-day knowledge and especially imagination. Similarly, as seen in the case of the Buddhist text, Cheng Weishi Lun 成唯識論, or the Zapotec of Mesoamerica, one’s interpretation or positioning in relation to certain analytical categories can result in different—yet accurate—interpretations; interpretations that similarly reflect the diversity and debate inherent within past and present contexts of study.

Given these issues, as well as the sheer variety of practices and beliefs that can be characterized as “religious”, a recurrent concern for both the experts and staff of the DRH is that its standardized questions and their categories may constrain understanding or even distort the very data that it seeks to capture. However, as seen above, utilizing a single analytical category like “supreme high god” as a provisional comparative space can bring together related yet different discussions on a variety of topics—including divine hierarchy and the relationships of power and exchange between humans and the non-human entities that they venerate—that might otherwise be kept separate by disciplinary boundaries.

In doing so, the DRH not only catalyzes further research, but fosters exchanges that undermine and disrupt its own ontological foundations. As the project grows, this disruption will be self-reflexively integrated as existing Polls are modified and new Polls created, thereby generating new comparative categories that will themselves be disrupted and revised.

The DRH thus allows for unique cross-cultural comparison that is firmly rooted in empirical data. The refined-in-scope nature of its entries, their rich commentary, and their links to more expansive works, mean that instant queries can present a wealth of interpretations organized according to a wide variety of provisional categories, questions, and themes that is not only rooted in nuanced engagement with empirical data, but also provides the basis for continual theoretical refinement.

11. Conclusions

In summary, the Database of Religious History presents an innovative resource for scholarly use and pedagogical application. In an age of information overload, the open-access, digital, and queryable nature of the DRH allows for instant access to an expansive set of expert analyses on particular topics related to the study of religion. Beyond the context-specific descriptions and rich bibliographies, the ability to query specific questions (following the parameters of the database) allows for instant comparison of a topic across user-designed geographic regions and chronological parameters. To demonstrate this potential, case studies from the ancient Near East, ancient Egypt, ancient Greece, China, Mesoamerica, and the Late Antique Mediterranean grappled with the concept of “high gods” in their respective contexts. These case studies highlighted the dynamism and diversity of understandings of “high gods” both within the contexts of study and from the different positions of scholars whose responses at times reflect current debate in the field. As such, the DRH affords an opportunity to catalyze further research, to introduce students to many of the complexities at the root of the study of religion, and indeed to test and disrupt ontologies.